Abstract

Background

Unintended pregnancy remains a major public health and socio-economic problem in sub-Saharan African countries, including Cameroon. Modern contraceptive use can avert unintended pregnancy and its related problems. In Cameroon, the prevalence of modern contraceptive use is low. Therefore, this study investigated the individual/household and community-level predictors for modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon.

Methods

Data for this study were derived from the nationally representative 2018–2019 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey. Analysis was done on 6080 married women in the reproductive age group (15–49 y) using Stata version 14 software. Pearson χ2 test and multilevel logistic regression analysis were conducted to examine the individual/household and community-level predictors of modern contraceptive use. Descriptive results were presented using frequencies and bar charts. Inferential results were presented using adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

The results show only 18.3% (95% CI 16.8 to 19.8) of married women in Cameroon use modern contraceptives. Women's age (45–49 y; aOR 0.22 [95% CI 0.12 to 0.39]), education level (secondary education; aOR 2.93 [95% CI 1.90 to 4.50]), occupation (skilled manual; aOR 1.46 [95% CI 1.01 to 2.11]), religion (Muslim; aOR 0.63 [95% CI 0.47 to 0.84]), wealth quintile (richest; aOR 2.22 [95% CI 1.35 to 3.64]) and parity (≥5; aOR 3.59 [95% CI 2.61 to 4.94]) were significant individual/household-level predictors. Region (East; aOR 3.63 [95% CI 1.97 to 6.68]) was identified as a community-level predictor.

Conclusions

Modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon is low. Women's education and employment opportunities should be prioritized, as well as interventions for married women, ensuring equity in the utilization of modern contraceptives across regions.

Keywords: Cameroon, DHS, global health, modern contraceptive, multilevel, predictors, women's health

Introduction

In the 21st century, family planning is considered an essential intervention for significant improvement of maternal and child health.1–3 As a result, ensuring universal coverage and utilization of modern contraceptives can help meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.3 Furthermore, unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion-related social, mental and obstetric complications and maternal mortality can be averted through effective utilization of modern contraceptives.4–7 Also, modern contraceptives have individual benefits such as preventing unwanted pregnancy and its related emotional, financial and social problems such as discrimination by friends, family and the community.8 They also empower women by allowing continued education and the opportunity to work,8 positively contributing to societal and national development through increased women's participation in the labour market and optimization of limited resources due to reduced population growth.9,10

Globally, of the 1.1 billion women who needed family planning in 2019, 842 million used contraceptive methods, while the remaining 270 million had unmet needs.8 Worldwide, 75% of women are satisfied with their family planning needs, however, coverage is <50% in Central and West Africa.8 Although Cameroon has ratified the Family Planning 2020 (FP2020) initiative and committed to meeting the SDG target to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality through improved utilization of modern contraceptives,3 national family planning coverage remains extremely low.11 For example, according to the 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey (CDHS), the use of modern contraceptive methods among married women was <15%, although it was higher among sexually active non-married women, at 43%.11 In Cameroon, an increase in the utilization of modern contraceptive methods has not been satisfactory, from 4% to 15% from 1991 to 2018.11 Recently a community-based study in the northwest region estimated a modern contraceptive utilization rate of 13%.4

Several scholars in Cameroon4,12,13 and other African countries14–20 have shown that modern contraceptive use is linked to socio-economic conditions, women’s empowerment, partner support and geographic-related factors. The fact that few studies are available in Cameroon4,12,13 on modern contraceptive methods and continued poor uptake, especially among married women, motivated us to investigate wide-ranging predictors for modern contraceptive use in the country, using nationally representative data and a robust methodological approach. Therefore, this study examined individual/household and community-level predictors of modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon.

Methods

Data source

We extracted nationally representative data from the 2018–2019 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey (CDHS) for analysis.11 The 2018–2019 CDHS collected data to monitor demographic and numerous health indicators, including modern contraceptive use. The National Institute of Statistics (NIS), in collaboration with several national and international organizations, completed the initiative with financial and technical support from United States Aid for International Development (USAID) and the Inner-City Fund (ICF) International, respectively.11 The survey applied a two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique. The probability proportional to size (PPS) technique was used to select large geographic locations, known as enumeration areas (EAs), from the sampling frame prepared in the recent population census (2005). In the second stage, a sample of households was selected using a systematic sampling technique of the EAs selected in the first stage.11 A total of 13 527 women ages 15–49 y and 6978 men ages 15–64 y were interviewed.11 The sample size for the study excluded pregnant and infecund married women and was limited to 6080 married women in the reproductive age group (15–49 y).21,22

Study variables

Outcome variable

The main outcome variable of this study was modern contraceptive use. Married women who said they use one of the following methods were considered as modern contraceptive users: female sterilization (tubal ligation, laparotomy, voluntary surgical contraception for women), male sterilization (vasectomy, voluntary surgical contraception for men), contraceptive pills (oral contraceptives), intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD), injectables (Depo-Provera), implants (Norplant), female condom, male condom (prophylactic, rubber), diaphragm, contraceptive foam or jelly, lactational amenorrhea method (LAM), standard days method (SDM), country-specific modern methods and respondent-mentioned other modern contraceptive methods (including cervical cap, contraceptive sponge and others), but does not include abortions and menstrual regulation.23–27 Married women who used any method other than those mentioned above were not considered as modern contraceptive users. Other methods include periodic abstinence (rhythm, calendar method), withdrawal (coitus interruptus) and country-specific traditional methods and folk methods (locally described methods and spiritual methods of unproven effectiveness, such as herbs, amulets, gris-gris, etc.).23–27 The dichotomous outcome variable was coded as ‘yes’ if the married women used at least one of the above aforementioned modern contraceptive methods and ‘no’ if the women used none of the modern contraceptive methods.

Explanatory variables

Individual/household and community-level predictors were selected based on their proven significant association in prior literature.14–20,23–27

Individual/household-level predictors

Several individual/household-level predictors were included.15–49 We used the women's age, religion (Catholic, Protestant, other Christian, Muslim, other), ideal number of children (0–3, 4–5, ≥6), parity (0–2, 3–4, ≥5), media exposure and decision making. Media exposure was coded as ‘yes’ if the married woman had exposure for either of the three media sources (newspaper, radio, television) for at least once a week and ‘no’ otherwise. Women who made decisions alone or together with husbands on all three decision-making parameters (their own health, to purchase large household expenses, to visit family or relatives) were coded as ‘1’, otherwise they were coded as ‘0’.28,29 We also included the education level of the women and their husbands (no formal education, primary school, secondary school, higher), the women's occupation (not working, sales, agricultural self-employed, others) and the husband's occupation (not working, professional or technical or manager or clerical, sales, agricultural self-employed, services, skilled manual, unskilled manual). The wealth index was used as a proxy for economic status. Categorized as poorest, poor, middle, rich and richest, the DHS classifies the wealth index using household assets and ownership using principal component analysis (PCA), as explained elsewhere.30

Community-level predictors

Community-level predictors included place of residence (urban, rural), region (Adamawa, Centre [without Yaounde], Douala, East, Far North, Littoral [without Douala], North, Northwest, West, South, Southwest, Yaoundé), distance to a health facility (big problem, not a big problem), community socio-economic status (SES; low, medium, high) and community-level modern contraceptive knowledge (low, medium, high). The occupation, education and wealth of survey participants in each community were used to compute community-level SES. PCA was used to calculate women who were unemployed, uneducated and poor. A standardized score was derived, with a mean score (0) and standard deviation (1). These were then categorized into tertile 1 (lowest score, least disadvantaged and greater SES), tertile 2 and tertile 3 (highest score, most disadvantaged and lowest SES). To determine the community literacy level, respondents who attended higher than secondary school were assumed to be literate, while all other respondents were given a sentence to read and were considered literate if they could read all or part of the sentence. Therefore, high literacy included respondents who had higher than a secondary education or had no school/primary/secondary education but could read a whole sentence. Medium literacy was respondents without school/primary/secondary education who could read part of the sentence. Low literacy was respondents who had no school/primary/secondary education and could not read at all. These were categorized into appropriate tertiles, where tertile 1 (lowest score, least disadvantaged) was high community literacy, tertile two (medium score) was medium community literacy and tertile 3 (highest score, most disadvantaged) was low community literacy.

Statistical analysis

Using Stata version 14 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), analyses were conducted using the following steps. First, frequencies and percentages, including the prevalence of modern contraceptive use, were used to present the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Next, bivariate analysis (Pearson χ2 test) determined whether there was an association between each individual/household and community-level variables and modern contraceptive use and p-values <0.05 were used as a cut-off point. For all variables that had significant associations in the χ2 test, a multicollinearity test was performed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) to test the presence or absence of collinearity, and the result showed no evidence of multicollinearity (mean VIF 1.76, minimum VIF 1.03, maximum VIF 3.59). Two-level and multilevel logistic regression analyses were then carried out for all independent variables that had significant associations in the χ2 test. Using four steps, we constructed four models. First, we constructed the empty/null model, which represents the model that focuses on the variance in the outcome variable (modern contraceptive use), accredited to the clustering at the primary sampling units (PSUs) (model 0). Second, the individual/household-level factors were included in a model to assess their association with modern contraceptive use (model 1). Third, we developed a model that included only the community-level variables, to assess their association with modern contraceptive use (model 2). We used the term community to describe clustering within the same geographical living environment. Communities were based on sharing a common PSU within the DHS data. Finally, all the variables were included for a complete model (model 3). The multilevel logistic regression model yielded fixed and random effects.26,27,31–33 Reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), the fixed effects (measures of association) revealed the association between the independent variables and the dependent/outcome variable. Intracluster correlation assesses the random effects (measures of variations).34 The likelihood ratio (LR) checks for model adequacy, while Akaike's information criterion (AIC) was used to measure how well the different models best fit the data. We also reported the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), ρ, for each model. The ICC is the proportion of variance in the outcome variable (modern contraceptive use) that is explained by the grouping structure of the hierarchical model. It is calculated as a ratio of group-level error variance over the total error variance:

|

where  is the variance of the level 2 residuals and

is the variance of the level 2 residuals and  is the variance of the level 1 residuals. In other words, the ICC reports the amount of variation unexplained by any predictors in the model that can be attributed to the grouping variable as compared with the overall unexplained variance (within and between variance). The complex structure and design of the CDHS data were considered using the svyset command module in Stata; all three design elements (weight, cluster and strata) were considered. For the preparation of this article, we followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.35

is the variance of the level 1 residuals. In other words, the ICC reports the amount of variation unexplained by any predictors in the model that can be attributed to the grouping variable as compared with the overall unexplained variance (within and between variance). The complex structure and design of the CDHS data were considered using the svyset command module in Stata; all three design elements (weight, cluster and strata) were considered. For the preparation of this article, we followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.35

Ethical consideration

Data for this study were obtained from a secondary dataset with de-identified information. To have access to the data, the authors obtained and were granted approval to use the dataset by MEASURE DHS. The data are secondary and available in the public domain, therefore no further approvals were required for this study. Details regarding data and ethical standards are available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

As shown in Table 1, 7.4% were adolescents (15–19 y of age) and 51.4% of the respondents were rural residents. A total of 28.5% and 25.9% of participants had not attended formal education and were not working, respectively. A total of 42.7% of the participants were not exposed to media (newspaper, radio or television) at least once a week. Regarding decision making, only 46.6% of married women had decided, either alone or with their husband, on all three of the decision-making parameters—their own health, to purchase large household expenses and to visit family or relatives.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of respondents and modern contraceptive use distribution across explanatory variables among married women: evidence from the 2018–2019 CDHS

| Modern contraceptive (weighted %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Number (weighted %) | No | Yes | χ2, p-value |

| Overall prevalence | 6080 (18.3) | |||

| Age (years) | 65.35, <0.001 | |||

| 15–19 | 465 (7.39) | 87.85 | 12.15 | |

| 20–24 | 977 (15.77) | 78.32 | 21.68 | |

| 25–29 | 1325 (22.29) | 79.36 | 20.64 | |

| 30–34 | 1221 (20.78) | 78.73 | 21.27 | |

| 35–39 | 976 (16.08) | 82.14 | 17.86 | |

| 40–44 | 691 (10.86) | 87.42 | 12.58 | |

| 45–49 | 425 (6.83) | 90.08 | 9.92 | |

| Women's education level | 384.84, <0.001 | |||

| No formal education | 1506 (28.51) | 96.23 | 3.77 | |

| Primary school | 1971 (30.19) | 80.38 | 19.62 | |

| Secondary school | 2274 (35.66) | 73.23 | 26.77 | |

| Higher | 329 (5.64) | 69.71 | 30.29 | |

| Husband's education level | 318.80, <0.001 | |||

| No formal education | 1211 (23.76) | 96.32 | 3.68 | |

| Primary school | 1865 (30.89) | 81.44 | 18.56 | |

| Secondary school | 2268 (36.03) | 76.12 | 23.88 | |

| Higher | 546 (9.32) | 67.55 | 32.45 | |

| Women's occupation | 138.66, <0.001 | |||

| Not working | 1664 (25.85) | 85.06 | 14.94 | |

| Sales | 1219 (19.87) | 78.22 | 21.78 | |

| Agricultural | 2051 (34.93) | 86.86 | 13.14 | |

| Services | 635 (10.43) | 71.16 | 28.84 | |

| Skilled manual | 325 (5.51) | 71.79 | 28.21 | |

| Other | 186 (3.42) | 73.29 | 26.71 | |

| Husband's occupation | 181.20, <0.001 | |||

| Not working | 173 (2.53) | 88.52 | 11.48 | |

| Professional or technical or manager or clerical or clerical | 374 (5.83) | 74.38 | 25.62 | |

| Sales | 1035 (16.46) | 79.01 | 20.99 | |

| Agricultural self-employed | 2343 (39.92) | 89.02 | 10.98 | |

| Services | 709 (11.26) | 70.49 | 29.51 | |

| Skilled manual | 1219 (20.38) | 77.60 | 22.40 | |

| Unskilled manual | 202 (3.63) | 79.35 | 20.65 | |

| Religion | 173.08, <0.001 | |||

| Catholic | 2094 (34.83) | 75.23 | 24.77 | |

| Protestant | 1613 (24.11) | 80.17 | 19.83 | |

| Muslim | 1706 (30.21) | 91.16 | 8.84 | |

| Others | 667 (10.84) | 79.96 | 20.04 | |

| Wealth status | 254.65, <0.001 | |||

| Poorest | 1067 (21.26) | 94.91 | 5.09 | |

| Poorer | 1249 (19.69) | 84.26 | 15.74 | |

| Middle | 1407 (19.50) | 79.69 | 20.31 | |

| Richer | 1236 (19.60) | 76.94 | 23.06 | |

| Richest | 1121 (19.96) | 71.97 | 28.03 | |

| Media exposure | 237.22, <0.001 | |||

| No | 2456 (42.74) | 90.58 | 9.42 | |

| Yes | 3624 (57.26) | 75.15 | 24.85 | |

| Decision making | 63.52, <0.001 | |||

| No | 3069 (53.37) | 85.44 | 14.56 | |

| Yes | 3011 (46.63) | 77.52 | 22.48 | |

| Ideal number of children | 183.94, <0.001 | |||

| 0–3 | 697 (11.19) | 72.6 | 27.4 | |

| 4–5 | 2181 (33.81) | 74.94 | 25.06 | |

| ≥6 | 3202 (55.00) | 87.79 | 12.21 | |

| Parity | 29.95, <0.001 | |||

| 0–2 | 1221 (19.56) | 86.17 | 13.83 | |

| 3–4 | 2785 (45.75) | 79.11 | 20.89 | |

| ≥5 | 2074 (34.69) | 82.73 | 17.27 | |

| Place of residence | 135.67, <0.001 | |||

| Urban | 2929 (48.65) | 75.82 | 24.18 | |

| Rural | 3151 (51.35) | 87.36 | 12.64 | |

| Distance to health facility | 28.45, <0.001 | |||

| Not a big problem | 2580 (42.10) | 84.84 | 15.16 | |

| Big problem | 3500 (57.90) | 79.49 | 20.51 | |

| Region | 353.84, <0.001 | |||

| Adamawa | 541 (5.51) | 92.88 | 7.12 | |

| Centre (without Yaounde) | 587 (8.89) | 72.83 | 27.17 | |

| Douala | 458 (11.03) | 79.58 | 20.42 | |

| East | 510 (5.85) | 64.48 | 35.52 | |

| Far North | 790 (18.21) | 91.90 | 8.10 | |

| Littoral (without Douala) | 384 (3.53) | 81.25 | 18.75 | |

| North | 775 (15.67) | 91.64 | 8.36 | |

| Northwest | 305 (5.96) | 75.36 | 24.64 | |

| West | 578 (10.18) | 79.02 | 20.98 | |

| South | 559 (4.50) | 82.50 | 17.50 | |

| Southwest | 127 (1.56) | 76.81 | 23.19 | |

| Yaounde | 466 (9.12) | 67.97 | 32.03 | |

| Community literacy level | 236.85, <0.001 | |||

| Low | 2492 (44.66) | 90.10 | 9.90 | |

| Medium | 1879 (26.66) | 76.91 | 23.09 | |

| High | 1709 (28.68) | 73.24 | 26.76 | |

| Community SES | 193.01, <0.001 | |||

| Low | 2935 (49.18) | 88.71 | 11.29 | |

| Medium | 1319 (18.54) | 76.14 | 23.86 | |

| High | 1826 (32.28) | 74.35 | 25.65 | |

| Community-level modern contraceptive knowledge | 75.51, <0.001 | |||

| Low | 2128 (31.65) | 87.46 | 12.54 | |

| Medium | 1978 (33.38) | 81.38 | 18.62 | |

| High | 1974 (34.97) | 76.92 | 23.08 | |

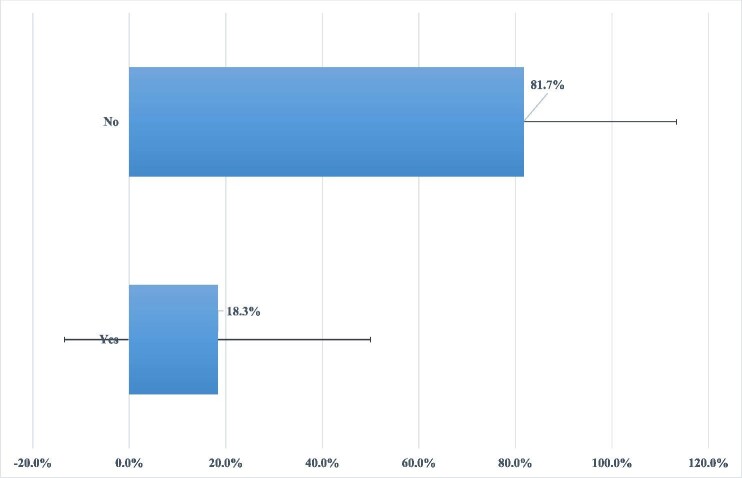

Overall prevalence of modern contraceptive use

The prevalence of modern contraceptive use among married women was 18.3% (95% CI 16.8 to 19.8) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon: evidence from 2018–2019 CDHS.

Distribution of modern contraceptive use across explanatory variables

Table 1 shows the distribution of modern contraceptive use across explanatory variables and subgroups. For instance, only 9.9% of married women ages 45–49 y and 12.2% of married adolescents (15–19 y) used modern contraceptives, while the prevalence rose to 21.7% among married women ages 20–24 y. Modern contraceptive use among married women with no formal education was 3.8% and among those who attended higher education was 30.3%. A total of 3.7% of married women whose husbands had not attended formal education used modern contraceptives, compared with 32.5% of married women whose husbands had higher education. Modern contraceptive use ranged from 5.1% to 28.0% for married women in the poorest and richest households, respectively. The study showed that the prevalence of modern contraceptive use ranged from 14.6% to 22.5% among married women with decision-making power and those with no decision-making power, respectively (Table 1).

Predictors of modern contraceptive use

Fixed effects (measures of associations) results

Individual/household-level predictors.

As shown in Table 2, several individual/household-level predictors were significantly associated with modern contraceptive use. We found lower odds of modern contraceptive use among married women ages 40–44 y (aOR 0.32 [95% CI 0.20 to 0.52]) and 45–49 y (aOR 0.22 [95% CI 0.12 to 0.39]) as compared with married adolescents (15–19 y). The study showed higher odds of modern contraceptive use among married women who had attended primary school (aOR 2.52 [95% CI 1.71–3.71]), secondary school (aOR 2.93 [95% CI 1.90 to 4.50]) and higher education (aOR 2.48 [95% CI 1.29 to 4.75]) as compared with married women who had not attended any formal education. Similarly, we found higher odds of modern contraceptive use among married women whose husbands attended primary school (aOR 1.96 [95% CI 1.24 to 3.09]), secondary school (aOR 1.80 [95% CI 1.15 to 2.83]) and higher (aOR 2.23 [95% CI 1.32 to 3.77]) as compared with married women whose husbands had not attended formal education. Women's occupation (skilled manual; aOR 1.46 [95% CI 1.01 to 2.11]) was a significant predictor for modern contraceptive use.

Table 2.

Individual/household and community-level predictors for modern contraceptive use among married women: evidence from the 2018–2019 CDHS

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 15–19 | Ref | Ref | |

| 20–24 | 1.01 (0.68 to 1.51) | 1.05 (0.70 to 1.57) | |

| 25–29 | 0.82 (0.55 to 1.23) | 0.87 (0.58 to 1.31) | |

| 30–34 | 0.69 (0.45 to 1.05) | 0.74 (0.48 to 1.14) | |

| 35–39 | 0.49 (0.31 to 0.77)** | 0.53 (0.33 to 0.84)** | |

| 40–44 | 0.29 (0.18 to 0.47)*** | 0.32 (0.20 to 0.52)*** | |

| 45–49 | 0.20 (0.11 to 0.35)*** | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.39)*** | |

| Women's education level | |||

| No formal education | Ref | Ref | |

| Primary school | 2.60 (1.77 to 3.81)*** | 2.52 (1.71 to 3.71)*** | |

| Secondary school | 2.94 (1.92 to 4.50)*** | 2.93 (1.90 to 4.50)*** | |

| Higher | 2.52 (1.32 to 4.81)** | 2.48 (1.29 to 4.75)** | |

| Husband's education level | |||

| No formal education | Ref | Ref | |

| Primary school | 2.06 (1.30 to 3.25)** | 1.96 (1.24 to 3.09)** | |

| Secondary school | 1.90 (1.21 to 3.00)** | 1.80 (1.15 to 2.83)* | |

| Higher | 2.36 (1.39 to 4.01)** | 2.23 (1.32 to 3.77)** | |

| Women's occupation | |||

| Not working | Ref | Ref | |

| Sales | 1.19 (0.93 to 1.51) | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.46) | |

| Agricultural | 1.28 (0.96 to 1.69) | 1.22 (0.90 to 1.64) | |

| Services | 1.28 (0.93 to 1.75) | 1.22 (0.90 to 1.67) | |

| Skilled manual | 1.54 (1.07 to 2.22)* | 1.46 (1.01 to 2.11)* | |

| Other | 1.51 (0.90 to 2.56) | 1.48 (0.87 to 2.51) | |

| Husband's occupation | |||

| Not working | Ref | Ref | |

| Professional or technical or manager or clerical or clerical | 1.55 (0.73 to 3.27) | 1.41 (0.67 to 2.97) | |

| Sales | 1.55 (0.75 to 3.19) | 1.39 (0.68 to 2.85) | |

| Agricultural self-employed | 1.24 (0.62 to 2.50) | 1.16 (0.58 to 2.33) | |

| Services | 1.90 (0.95 to 3.82) | 1.67 (0.83 to 3.35) | |

| Skilled manual | 1.42 (0.69 to 2.90) | 1.31 (0.64 to 2.66) | |

| Unskilled manual | 1.34 (0.67 to 2.68) | 1.24 (0.62 to 2.48) | |

| Religion | |||

| Catholic | Ref | Ref | |

| Protestant | 0.86 (0.70 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.14) | |

| Muslim | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.81)** | 0.63 (0.47 to 0.84)** | |

| Other | 0.96 (0.74 to 1.25) | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.21) | |

| Wealth status | |||

| Poorest | Ref | Ref | |

| Poorer | 2.08 (1.47 to 2.93)*** | 2.09 (1.47 to 2.97)*** | |

| Middle | 2.18 (1.48 to 3.20)*** | 2.08 (1.39 to 3.10)*** | |

| Richer | 1.98 (1.32 to 2.96)** | 1.82 (1.17 to 2.81)** | |

| Richest | 2.32 (1.49 to 3.60)*** | 2.22 (1.35 to 3.64)** | |

| Media exposure | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.25 (0.95 to 1.65) | 1.25 (0.95 to 1.65) | |

| Decision making | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.05 (0.87 to 1.27) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.25) | |

| Ideal number of children | |||

| 0–3 | Ref | Ref | |

| 4–5 | 0.76 (0.58 to 0.99)* | 0.74 (0.57 to 0.97)* | |

| ≥6 | 0.55 (0.40 to 0.74)*** | 0.54 (0.40 to 0.73)*** | |

| Parity | |||

| 0–2 | Ref | Ref | |

| 3–4 | 2.11 (1.66 to 2.67)*** | 2.08 (1.64 to 2.63)*** | |

| ≥5 | 3.69 (2.67 to 5.10)*** | 3.59 (2.61 to 4.94)*** | |

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | Ref | Ref | |

| Rural | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.91)* | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.01) | |

| Distance to health facility | |||

| Not a big problem | Ref | Ref | |

| Big problem | 1.09 (0.88 to 1.34) | 1.03 (0.82 to 1.29) | |

| Region | |||

| Adamawa | Ref | Ref | |

| Centre (without Yaounde) | 3.23 (1.76 to 5.92)*** | 1.63 (0.92 to 2.89) | |

| Douala | 1.60 (0.84 to 3.03) | 0.94 (0.52 to 1.71) | |

| East | 6.89 (3.61 to 13.12)*** | 3.63 (1.97 to 6.68)*** | |

| Far north | 1.25 (0.65 to 2.37) | 1.46 (0.83 to 2.55) | |

| Littoral (without Douala) | 2.11 (1.11 to 4.03)* | 1.19 (0.63 to 2.24) | |

| North | 1.33 (0.77 to 2.30) | 1.56 (0.95 to 2.58) | |

| Northwest | 3.70 (1.96 to 6.96)*** | 1.65 (0.96 to 2.85) | |

| West | 2.34 (1.26 to 4.33)** | 1.38 (0.78 to 2.46) | |

| South | 1.85 (0.93 to 3.67) | 1.05 (0.55 to 1.99) | |

| Southwest | 1.86 (0.88 to 3.91) | 1.17 (0.55 to 2.47) | |

| Yaounde | 2.88 (1.52 to 5.46)** | 1.71 (0.94 to 3.11) | |

| Community literacy level | |||

| Low | Ref | Ref | |

| Medium | 1.67 (1.18 to 2.37)** | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.35) | |

| High | 1.59 (1.06 to 2.39)* | 0.92 (0.63 to 1.34) | |

| Community SES | |||

| Low | |||

| Medium | 1.35 (0.98 to 1.87) | 1.19 (0.88 to 1.61) | |

| High | 1.19 (0.83 to 1.71) | 1.07 (0.75 to 1.52) | |

| Community-level modern contraceptive knowledge | |||

| Low | |||

| Medium | 1.32 (1.01 to 1.73)* | 1.27 (0.98 to 1.64) | |

| High | 1.33 (1.01 to 1.75)* | 1.15 (0.88 to 1.51) |

Values presented as aOR (95% CI).

Model 1: included only individual/household-level predictors; model 2: included only community-level predictors; model 3: included both individual/household and community-level predictors. Significant at ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05. Ref: reference. Other occupation included clerical, services, skilled and unskilled.

In this study we found lower odds of modern contraceptive use among Muslim married women (aOR 0.63 [95% CI 0.47 to 0.84]) compared with Catholic married women. Moreover, there were higher odds of modern contraceptive use among married women from poor (aOR 2.09 [95% CI 1.47 to 2.97]), middle (aOR 2.08 [95% CI 1.39 to 3.10]), rich (aOR 1.82 [95% CI 1.17 to 2.81]) and richest (aOR 2.22 [95% CI 1.35 to 3.64]) households as compared with married women in the poorest quintile. Married women with an ideal number of children of 4–5 (aOR 0.74 [95% CI 0.57 to 0.97]) and ≥6 (aOR 0.54 [95% CI 0.40 to 0.73]) had lower odds of modern contraceptive use than married women with an ideal number of 0–3 children. Furthermore, the study showed higher odds of modern contraceptive use among married women with a parity history of 3–4 (aOR 2.08 [95% CI 1.64 to 2.63]) and ≥5 (aOR 3.59 95% CI 2.61 to 4.94]) as compared with married women with a parity history of 0–2.

Community-level predictors.

As shown in Table 2, we found that region and community-level modern contraceptive knowledge were significant community-level predictors for modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon. More specifically, the study showed higher odds of modern contraceptive use among married women who were living in the East region (aOR 3.63 [95% CI 1.97 to 6.68]) as compared with married women who lived in the Adamawa region.

Random effects (measures of variations) results

As shown in Table 3, the empty model (model 0) shows significant variations in the prevalence of modern contraceptive use across the clusters (σ2=0.93 [95% CI 0.72 to 1.20]). The empty model further shows that 18% of the total variance in the prevalence of modern contraceptive use was attributed to between-cluster variations (ICC 0.20). The between-cluster variations decreased from 20% in model 0 to 8% in model 1 (individual/household only model), then remained constant as 8% in model 2 (community-level model only) and finally the ICC decreased to 5% in model 3 (complete model). This indicates that differences in the clusters of PSUs account for variations in modern contraceptive use. The best-fit model (model 3) was determined using the highest log-likelihood (−2442.02) and lowest AIC (4998.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Random effect results for individual/household and community-level predictors for modern contraceptive use among married women: evidence from the 2018–2019 CDHS

| Random effects result | Model 0 (empty model) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSU variance (95% CI) | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20) | 0.34 (0.22 to 0.52) | 0.36 (0.24 to 0.52) | 0.22 (0.13 to 0.37) |

| ICC | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| LR test | 269.33 | 53.97 | 57.74 | 21.61 |

| Wald χ2, p-value | Ref | 387.37, <0.001 | 254.48, <0.001 | 522.39, <0.001 |

| Model fitness | ||||

| Log-likelihood | −2821.65 | −2471.93 | −2719.09 | −2442.02 |

| AIC | 5647.32 | 5019.864 | 5480.193 | 4998.05 |

| PSU | 428 | 428 | 428 | 428 |

Ref: reference.

Discussion

Achieving the third SDG of reducing maternal morbidity and mortality and achieving universal health coverage to include access to essential healthcare services by 2030 have been issues of great concern in developing countries.36,37 Two-thirds of the global maternal deaths (196 000) take place in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).38 Maternal, neonatal and infant morbidity and mortality can be averted using modern contraceptives.9,39,40 Only 18.3% of married women use modern contraception in Cameroon, which has a high maternal mortality ratio.41,42 Using recent nationally representative data, we examined a broader range of individual/household and community-level predictors for modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon. We found that women's age was associated with modern contraceptive use with lower odds among older women compared with younger married women, like prior studies in Senegal,26 Ethiopia43 and Uganda.44 Possible explanations include higher education levels among the younger women45 and an increased likelihood of positive communication between younger women and their partner/husband about modern contraceptives.26,46

Consistent with previous studies in Ghana47 and Uganda,48 we found that women's education level affects modern contraceptive utilization. Education can promote decision-making capacity and autonomy, increase choices for economic freedom and affect women's current and future fertility plans.49 Furthermore, increased contraceptive uptake and fertility control were seen in communities where women achieved higher levels of education.50

We also found that the husband's education level had an influence on modern contraceptive utilization, as documented in previous studies in Senegal19 and SSA.15 It is possible that educated husbands are more likely to use modern contraceptives, which can contribute to fertility control, especially in families where men are the sole decision maker about fertility.16 Additionally, this might be due to better communication between spouses and approval of the husband.50,51 Better communication and discussion about family planning augment understanding and facilitate agreement on contraceptive issues between couples, which potentially leads to better uptake of modern contraceptive use.53,54

Like previous studies in Bangladesh55 and India,56 we identified that women who were employed had better utilization of modern contraceptives than non-employed women. Moreover, the study showed higher odds of modern contraceptive use among wealthier women than poor, as reported in previous studies in Senegal,26 Mali,27 Burkina Faso,57 Malawi58 and Bangladesh.59 This may be due to women from wealthier households having a higher SES that enables them to have better access to media and healthcare services.26,27,60,61

Moreover, religion had a significant association with modern contraceptive use, consistent with a previous study in Bangladesh.56 Religion plays a vital role in the lives of many people, with 88.3% of the global population relating with faith.62 As a result, faith leaders are a significant and often powerful factor in the lives of their followers.62 Also, many faith leaders have the skills and the platform to speak out and deliver key messages to their congregations.62 So working with faith leaders offers an opportunity to reach many people with messages distributed by those who are already significantly valued within their societies.62

Comparable with previous studies in Mali,27 Bangladesh63 and Indonesia,64 women who planned to have more children or those who perceived and desired to have more children were less likely to use modern contraceptives.65 The plausible reason for not using contraception among married women with a higher ideal number of children might be due to children being considered a prized resource for future household-level economic growth. This may be beneficial in resource-limited countries such as Cameroon; having more children potentially leads to additional household income due to the increased likelihood of more household members participating in the labour force.59,66 On the other hand, better utilization of modern contraceptives is reported among women who do not want to have more children, usually non-married women.27,67

Furthermore, we found that parity was a significant individual-level predictor for modern contraceptive use, with better use among married women of higher parity, as reported in prior studies in Uganda.44,45 This might be to limit future pregnancies.44,45 Comparable with prior studies in Bangladesh27,29 and Senegal,17 we found that modern contraceptive utilization significantly varied across regions. The plausible reason might be related to the difference in family planning services and the number of health facilities across regions.17,68 Furthermore, uneven distribution of health structures and health personnel across regions might make a difference in contraceptive use across regions.69 Variations in contraceptive supplies is another reason70 that needs further supply-related evaluation studies.4

Strength and limitations

Investigating wide-ranging predictors of modern contraceptive use using a multilevel modelling approach and nationally representative data are the main strengths of this study. The main limitation of this study is the use of cross-sectional data, which makes it impossible to infer causality from the associations observed in this study. Moreover, since the data were self-reported, the probabilities of recall and reporting biases should be considered. Predictors of modern contraceptive use were wide-ranging and multidimensional, but the choice of the independent variables was restricted to existing data from the CDHS. This study could not account for several residual confounders (i.e., cultural barriers). Another limitation is social desirability bias, since the DHS questionnaires are interviewer administered.

Conclusions

The findings show modern contraceptive use among married women in Cameroon is low. Women's age, education level, occupation, religion, wealth quintile, ideal number of children and parity, as well as the husband's education level, were significant individual/household-level predictors, whereas region was a community-level predictor. Improving women's employment opportunities through education and skilled occupations will ensure equity in modern contraceptive use across regions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MEASURE DHS project for their support and for free access to the original data.

Contributor Information

Betregiorgis Zegeye, HaSET Maternal and Child Health Research Program, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Dina Idriss-Wheeler, Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada.

Bright Opoku Ahinkorah, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney, Harris St, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia.

Edward Kwabena Ameyaw, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney, Harris St, Ultimo, NSW 2007, Australia.

Abdul-Aziz Seidu, Department of Population and Health, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana.

Mpho Keetile, Population Studies and Demography, University of Botswana, Private Bag UB 0022 Gaborone, Botswana.

Sanni Yaya, School of International Development and Global Studies, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada.

Authors’ contributions

SY and BZ contributed to the study design, conceptualization, literature review and data analysis and drafted the first version of this article. BOA, EKA, AS, MK and DIW provided technical support and critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. SY had final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors read and amended drafts of the paper and approved the final version.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data availability

The datasets for this study were sourced and analysed from the DHS and are available from: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

References

- 1. Bongaarts J, Cleland J, Townsend JWet al. Family planning programs for the 21st century. New York: Population Council; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations Population Division . World family planning 2017 highlights. New York: United Nations; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dockalova B, Lau K, Barclay Het al. Sustainable Development Goals and Family Planning 2020. London: International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2016. Available from: https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2016-11/SDG%20and%20FP2020.pdf [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edietah EE, Njotang PN, Ajong ABet al. Contraceptive use and determinants of unmet need for family planning; a cross sectional survey in the Northwest Region, Cameroon. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmed SQ, Liu LL, Tsui AO.. Maternal deaths averted by contraceptive use: an analysis of 172 countries. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):111–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warriner IK, Shah HI.. Preventing unsafe abortion and its consequences; priorities for research and action. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gelaye AA, Taye KN, Mekonen T.. Magnitude and risk factors of abortion among regular female students in Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Family planning/contraception methods. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/family-planningcontraception [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graff M, Bremner J.. A practical guide to population and development. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canning D, Schultz TP.. The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institute of Statistics (Cameroon) and ICF . 2018 Cameroon DHS summary report. Rockville, MD: ICF; 2020. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR266/SR266.pdf [accessed 2 January 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teboh CT. Determinants of modern contraceptive use in Cameroon from 1991 to 2004. PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Arlington; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ajong AB, Njotang PN, Yakum MNet al. Determinants of unmet need for family planning among women in urban Cameroon: a cross sectional survey in the Biyem-Assi Health District, Yaoundé.BMC Womens Health. 2016;16:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Endriyas M, Eshete A, Mekonnen Eet al. Contraceptive utilization and associated factors among women of reproductive age group in Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ Region, Ethiopia: cross-sectional survey, mixed methods. Contracept Reprod Med. 2017;2:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yaya S, Uthman OA, Ekholuenetale Met al. Women empowerment as an enabling factor of contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis of cross-sectional surveys of 32 countries. Reprod Health. 2018;15:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duze M, Mohammed I.. Male knowledge, attitudes, and family planning practices in northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006;10(3):53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bogale B, Wondafrash M, Tilahun Tet al. Married women's decision-making power on modern contraceptive use in urban and rural southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cavallaro FL, Benova L, Macleod Det al. Examining trends in family planning among harder-to-reach women in Senegal 1992–2014. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cronin CJ, Guilkey DK, Speizer IS. The effects of health facility access and quality on family planning decisions in urban Senegal. Health Econ. 2017;27(3):576–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha Jet al. Persistent high fertility in Uganda: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Batana YM, Ali PG.. An analysis of married women's empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa. Nairobi: African Economy Research Consortium; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kishor S, Subaiya L.. Understanding women's empowerment: a comparative analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data. DHS Comparative Reports 20. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 2008. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-CR20-Comparative-Reports.cfm [accessed 2 January 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley SEK, Croft TN, Fishel JDet al. Revising unmet need for family planning. DHS Analytical Studies 25. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS25/AS25%5B12June2012%5D.pdf [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 24. United Nations , Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2015. Trends in contraceptive use worldwide 2015. ST/ESA/SER.A/349. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_report_2015_trends_contraceptive_use.pdf [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang W, Staveteig S, Winter Ret al. Women's marital status, contraceptive use, and unmet need in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. DHS Comparative Report 44. Rockville, MD: ICF; 2017. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-CR44-ComparativeReports.cfm [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zegeye B, Ahinkorah BO, Idriss-Wheeler Det al. Modern contraceptive utilization and its associated factors among married women in Senegal: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Appiah Fet al. Individual and community-level factors associated with modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women in Mali: a mixed effects multilevel analysis of the 2018 Mali demographic and health survey. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hanmer L, Klugman J.. Exploring women's agency and empowerment in developing countries: where do we stand? Feminist Econ. 2016;22(1):237–63. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Croft TN., Marshall AMJ, Allen CKet al. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville, MD: ICF; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rutstein SO, Johnson K.. The DHS Wealth Index. DHS Comparative Reports 6. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gelman A, Hill J.. Data analysis using regression and multilevel hierarchical models. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Austin PC, Merlo J.. Intermediate and advanced topics in multilevel logistic regression analysis. Stat Med. 2017;36(20):3257–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahinkorah BO. Predictors of unmet need for contraception among adolescent girls and young women in selected high fertility countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel mixed effects analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0236352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gulliford MC, Adams G, Ukoumunne OCet al. Intraclass correlation coefficient and outcome prevalence are associated in clustered binary data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(3):246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger Met al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Shah V.. Wealth, education and urban–rural inequality and maternal healthcare service usage in Malawi. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1:e000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yaya S, Uthman OA, Amouzou Aet al. Inequalities in maternal health care utilization in Benin: a population based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization . Maternal mortality. 2019. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality%3e [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cleland J, Bernstein S, Alex Eet al. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gribbl JNJ, Bremner J.. Achieving a demographic dividend. Popul Bull. 2012;67(2):2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Meh C, Thind A, Terry AL.. Ratios and determinants of maternal mortality: a comparison of geographic differences in the northern and southern regions of Cameroon. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Institut National de la Statistique . Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples EDS-MICS. Cameroun 2011. Yaoundé, Cameroun; 2012. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR13/PR13.pdf [accessed 3 January 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abate MG, Tareke AA.. Individual and community level associates of contraceptive use in Ethiopia: a multilevel mixed effects analysis. Arch Public Health. 2019;77:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Namasivayam A, Lovell S, Namutamba Set al. Predictors of modern contraceptive use among women and men in Uganda: a population-level analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e034675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Asiimwe JB, Ndugga P, Mushomi J.. Socio-demographic factors associated with contraceptive use among young women in comparison with older women in Uganda. Calverton, MD: ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prata N, Bell S, Weidert Ket al. Varying family planning strategies across age categories: differences in factors associated with current modern contraceptive use among youth and adult women in Luanda, Angola. Open Access J Contracept. 2016;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wuni C, Turpin CA, Dassah ET. Determinants of contraceptive use and future contraceptive intentions of women attending child welfare clinics in urban Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sileo KM, Wanyenze RK, Lule Het al. Determinants of family planning service uptake and use of contraceptives among postpartum women in rural Uganda. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(8):987–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements Set al. Contextual influences on modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Benefo K. The community-level effects of women's education on reproductive behavior in rural Ghana. Demogr Res. 2006;14(20):485–508. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gubhaju B. The influence of wives’ and husbands’ education levels on contraceptive method choice in Nepal, 1996–2006. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(4):176–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hossain M, Ahmed S, Rogers L. Does a wife's education influence spousal agreement on approval of family planning? Random effects modeling using data from two West African countries. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(2):562–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bawah AA. Spousal communication and family planning behavior in Navrongo: a longitudinal assessment. Stud Fam Plann. 2002;33(2):185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shattuck D, Kerner B, Gilles Ket al. Encouraging contraceptive uptake by motivating men to communicate about family planning: the Malawi male motivator project. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1089–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hossain MB, Khan MHR, Ababneh Fet al. Identifying factors influencing contraceptive use in Bangladesh: evidence from BDHS 2014 data. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pushpa SP, Venkatesh R, Shivaswamy MS.. Study of fertility pattern and contraceptive practices in rural area. Indian J Sci Technol. 2011;4(4):429–31. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wulifan JK, Jahn A, Hien Het al. Determinants of unmet need for family planning in rural Burkina Faso: a multilevel logistic regression analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Adebowale SA, Adedini SA, Ibisomi LDet al. Differential effect of wealth quintile on modern contraceptive use and fertility: evidence from Malawian women. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sarker AR, Sheikh N, Mahumud RAet al. Determinants of adolescent maternal healthcare utilization in Bangladesh. Public Health. 2018;157:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Laski L. Realising the health and wellbeing of adolescents. BMJ. 2015;351:h4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Currie J. Healthy, wealthy, and wise: socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. J Econ Lit. 2009;47(1):87–122. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Walker C. Faith leaders and family planning: a research report. London: Christian Aid. Available from: https://www.christianaid.org.uk/sites/default/files/2017-11/Faith-leaders-family-planning-health-april2017.pdf [accessed 30 April 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Akram R, Sarker AR, Sheikh Net al. Factors associated with unmet fertility desire and perceptions of ideal family size among women in Bangladesh: insights from a nationwide Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Withers M, Kano M, Pinatih GNI.. Desire for more children, contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in a remote area of Bali, Indonesia. J Biosoc Sc. 2010;42(4):549–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Achana FS, Bawah AA, Jackson EFet al. Spatial and socio-demographic determinants of contraceptive use in the upper east region of Ghana. Reprod Health. 2015;12:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. United Nations Children's Fund . Children are the most important resource for future economic growth. Press release, 7 March2018. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJet al. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reprod Health. 2014;11:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Almalik M, Mosleh S, Almasarweh I.. Are users of modern and traditional contraceptive methods in Jordan different? East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(4):377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sourou KDB. Iniquity of women's access to maternal health care services in Senegal. Presented at the Population Association of America annual meeting Chicago, Illinois, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Guttmacher Institute . Costs and benefits of investing in contraceptive services in Cameroon. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/costs-and-benefits-investing-contraceptive-services-cameroon [accessed 6 June 2021]. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this study were sourced and analysed from the DHS and are available from: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.