Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a human pathogen and a leading cause of food-poisoning in the United States and Europe. Surrounding the outside of the bacterium is a carbohydrate coat known as the capsular polysaccharide. Various strains of C. jejuni have different sequences of unusual sugars and an assortment of decorations. Many of the serotypes have heptoses with differing stereochemical arrangements at C2 through C6. One of the many common modifications is a 6-deoxy-heptose that is formed by dehydration of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose to GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-d-lyxo-heptose via the action of the enzyme GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase. Herein we report the biochemical and structural characterization of this enzyme from C. jejuni 81-176 (serotype HS:23/36). The enzyme was purified to homogeneity and its three-dimensional structure determined to a resolution of 2.1 Å. Kinetic analyses suggest that the reaction mechanism proceeds through the formation of a 4-keto intermediate followed by the loss of water from C5/C6. Based on the three-dimensional structure it is proposed that oxidation of C4 is assisted by proton transfer from the hydroxyl group to the phenolate of Tyr-159 and hydride transfer to the tightly bound NAD+ in the active site. Elimination of water at C5/C6 is most likely assisted by abstraction of the proton at C5 by Glu-136 and subsequent proton transfer to the hydroxyl at C6 via Ser-134 and Tyr-159. A bioinformatic analysis identified 19 additional 4,6-dehydratases from serotyped strains of C. jejuni that are 89-98% identical in amino acid sequence, indicating that each of these strains should contain a 6-deoxy-heptose within their capsular polysaccharides.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter jejuni is one of the most prevalent bacterial food-borne pathogens in the industrial world (1–2). Human infections are largely acquired through consumption and handling of contaminated poultry or raw milk (3–5). The symptoms of campylobacteriosis include severe diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever, headache, and nausea (6). About one in every 1,000 reported cases of C. jejuni infections leads to the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome, an acquired autoimmune disorder resulting in muscle weakness, paralysis, and hospitalization (7). It is estimated that the various strains of Campylobacter cause over 25,000 deaths annually in children under five years of age, primarily affecting Asian and African populations (8). An important virulence factor for C. jejuni infections is the capsular polysaccharide (CPS), which coats the exterior cell surface and mediates the interactions of the bacterium with its host (9). The capsular polysaccharides vary in sugar composition and linkage within the various strains of the bacterium. The repeating structures of the capsular polysaccharides in C. jejuni NCTC11168 (serotype HS:2) and C. jejuni 81-176 (serotype HS:23/36) are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of the repeating sugar units in the CPS from C. jejuni strains NCTC 11168 (1) and 81-176 (2). R1 corresponds to the methyl phosphoramidate modification, while R2 represents a methyl ether modification.

At least 12 CPS structures from various strains of C. jejuni have been reported, and nine of them contain heptose moieties with at least 13 different structural variations (7–10). Bioinformatic analyses and other experimental data suggest that all of the known heptose variations in C. jejuni likely originate from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) (11). In C. jejuni NCTC 11168 the final heptose moiety is d-glycero-l-gluco-heptose, whereas in C. jejuni 81-176 it can either be 6-deoxy-α-d-altro-heptose (as shown in Figure 1) or d-glycero-α-d-altro-heptose (12–13). In the biosynthesis of the modified 6-deoxy-heptose sugars, GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) is first dehydrated to GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) (14–15). The oxidation of C4 renders the adjacent stereocenters at C3 and C5 susceptible to isomerization by an epimerase (16–19). In the final step, a C4 reductase establishes the ultimate stereochemistry at C4. This combination of enzymes can thus generate up to eight different compounds that are stereochemically different at C3, C4, or C5. These transformations are summarized in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1:

General biosynthetic pathway for the formation of 6-deoxy-heptoses from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) in C. jejuni.

Efforts have been made previously to understand the heptose modification pathways more completely in the CPS of C. jejuni by isolating and characterizing the enzymes that are responsible for the conversion of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) to the various modified heptoses (14–19). The Creuzenet laboratory cloned, purified, and biochemically characterized two key enzymes within the 6-deoxy-d-altro-heptose biosynthesis pathway in C. jejuni 81-176, namely DdahA and DdahB (14, 20–21). DdahA (also known as WcbK) was shown to be a GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase that catalyzes the committed step in the formation of 6-deoxy-heptoses in C. jejuni. DdahB was shown to catalyze the C3-epimerization of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) to GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-arabino-heptose (20). This product is reduced by DdahC to form GDP-6-deoxy-α-d-altro-heptose (21).

Here, we report the three-dimensional structure of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase determined to 2.1 Å resolution and hereafter referred to as GMH dehydratase. On the basis of this structure, seven site-directed variants were constructed to test their role in the catalytic reaction mechanism of this 4,6-dehydratase. The reaction is proposed to proceed through the oxidation of C4 by the tightly bound NAD+, followed by the loss of water from C5/C6 to form the unsaturated ketone intermediate (16). The ultimate product is made via the reduction of the C5/C6 double bond by the tightly bound NADH produced during the oxidation of C4.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Materials, Equipment, and Chemicals.

All materials used in this study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Carbosynth, or GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, unless otherwise stated. Escherichia coli strain BL21-Gold (DE3) was obtained from New England Biolabs. Ultraviolet (UV) spectra were recorded on a SpectraMax340 UV-visible (UV-vis) plate reader using Greiner UV-Star® 96-well plates. α-Ketoglutarate was purchased from AK Scientific (Union City, CA). GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) was synthesized and purified as described previously (11).

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase.

The gene encoding GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase (Cjj1426) from C. jejuni 81-176 (WP_002869408) and serotype HS:23/36 was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli and ordered from Twist Biosciences in a pET28a expression vector with an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag. The sequence of the expressed protein is presented in Figure S1a. Cells harboring the plasmid used for expression of the target enzyme were cultured in lysogeny broth supplemented with 50 mg/L kanamycin. The cells were grown at 37 °C with shaking and induced with 1.0 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when the optical density reached ~0.6 at 600 nm. The cells were allowed to express protein at 21 °C for 18 h after induction, and then harvested by centrifugation at 8000g at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in the loading buffer (50 mM HEPES/K+, 500 mM KCl and 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and lysed with sonication. The sonicated cells were centrifuged at 12000g at 4 °C before the lysate was passed through a 0.45 μm filter (Whatman). The sample was loaded onto a prepacked 5-mL HisTrap nickel affinity column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted from the column using elution buffer (50 mM HEPES/K+, 250 mM KCl, and 500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) over a gradient of 30 column volumes. The protein was pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM HEPES/K+ containing 250 mM KCl, pH 8.0. The protein was concentrated to 10 mg/mL and flash-frozen using liquid nitrogen before being stored at −80 °C. Approximately 30 mg of protein was obtained per liter of cell culture.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Cje1612 and Cj1427.

The gene encoding GDP-6-deoxy-α-d-manno-heptose synthase (Cje1612) from C. jejuni RM1221 (WP_002867270.1) and serotype HS:53 was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli and synthesized by Twist Biosciences in a pET28a expression vector with an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag. The gene for the expression of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4-dehydrogenase (Cj1427) from C. jejuni strain NCTC 11168 (WP_002858299.1) and serotype HS:2 was cloned into a pET30a+ vector with an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag (17). The two proteins were expressed, purified, and stored using the same procedures as described for GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase (GMH dehydratase). The amino acid sequences of these two proteins are presented in Figures S1b and S1c.

Cofactor Identification and Occupancy.

The binding of cofactors to the as-purified GMH dehydratase was determined by UV-visible spectroscopy. GMH dehydratase at a concentration of 5.0 mg/mL was heated to 100 °C for 60 s to liberate any noncovalently bound factors. The precipitated protein was removed using PALL Nonosep 10K filters. The UV spectrum (220-400 nm) of the resulting flow-through was obtained and was consistent with either NAD+ or NADP+. The sample was subsequently injected onto a BioRad HPLC system equipped with a 1.0 mL Resource Q Column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with water, and the sample eluted with a linear gradient of 500 mM ammonium bicarbonate (19). The elution profile was calibrated using a mixture of NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH.

Bioinformatic Analysis of GMH Dehydratase.

The amino acid sequence of GMH dehydratase was obtained from the UniProt database (UniProt Entry: Q5M6Q7) and used as the search query for the BLAST section of the EFI-EST webtool (efi.igb.illinois.edu/efi-est) to generate a sequence similarity network (SSN) (22). The parameters were set such that the BLAST search retrieved the 1000 closest sequences to the query and the sequence identity was set at 68%. The SSN was created using the yFiles organic layout, and the image was created using Cytoscape version 3.8.2.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

The gene encoding GMH dehydratase was mutated at different residue positions using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method from Agilent Technologies. The mutated genes were fully sequenced to ensure that there were no unwanted mutations, deletions, or insertions occurring during the process of mutagenesis. The variants were expressed and purified to homogeneity using the same procedure as described for the purification of the wild-type enzyme.

Determination of Kinetic Constants.

The kinetic parameters of the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase, and the associated variants were determined by reducing the reaction product with NADPH in the presence of the C4 reductase Cje1612 as shown in Scheme 2. The reaction mixture contained 0.3 mM NADPH, 10 μM Cje1612, 0.1 μM GMH dehydratase (higher concentrations for variants), and varying concentrations of the substrate GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3), in 50 mM HEPES/K+, pH 7.5. The absorbance decrease at 340 nm, due to the conversion of NADPH to NADP+, was monitored spectrophotometrically at 30 °C with a SpectraMax340 UV-visible spectrophotometer. The kinetic parameters were determined by fitting the initial rates to eq. 1, where ν is the initial velocity of the reaction, Et is the enzyme concentration, kcat is the turnover number, A is the substrate concentration, and Km is the Michaelis constant.

Scheme 2:

Coupled enzyme reaction for measuring the kinetic constants for the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase.

| (1) |

Determination of Reaction Products for GMH Dehydratase.

The reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase was followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy with a Bruker Ascend™ 400 MHz Spectrometer after incubation of 4.0 mM GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) and 5 μM GMH dehydratase in 50 mM NH4HCO3 in D2O, pD 7.5. The 1H NMR spectra were recorded at different time intervals. The reaction was also conducted in 50 mM NH4HCO3 in H2O, pH 7.5. After the reaction was complete, the protein was removed using PALL Nanaosep 10K filters, and the product was dried thoroughly under vacuum, and then dissolved in 50 mM NH4HCO3 in D2O, pD 7.5, for 1H NMR spectroscopy. The products were also examined by mass spectrometry where 2.0 mM GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) and 2.5 μM GMH dehydratase were reacted in 50 mM NH4HCO3, in either D2O or H2O. After the reaction was complete, the enzyme was removed using PALL Nanaosep 10K filters and the resulting flowthrough was analyzed by mass spectrometry using a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Focus mass spectrometer.

Enzymatic Synthesis of Putative Reaction Intermediates.

A mixture of 2.0 mM GDP-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3), 20 μM Cj1427, and 10 mM α-ketoglutarate in 50 mM NH4HCO3, pH 7.5 was reacted at room temperature for 2 h, and then the enzyme was removed by filtration to provide a mixture of compounds 3 and 7 (17). To this mixture was added 5 μM GMH dehydratase to catalyze the dehydration of compound 3 and to probe for the dehydration of compound 7. The products were analyzed by negative ion ESI mass spectrometry.

X-ray Analysis of the GMH Dehydratase.

For crystallization trials, the GMH dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 (HS:23/36) was first dialyzed against 200 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and concentrated to ~20 mg/mL. X-ray quality crystals were grown in the presence of 5.0 mM GDP at room temperature via hanging drop and using a precipitant containing 6-10% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 200 mM tetramethylammonium chloride, and 100 mM HEPPS (pH 8.0). For X-ray data collection, the crystals were transferred to a cryo-protectant composed of 24% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM tetramethylammonium chloride, 5.0 mM GDP, 22% ethylene glycol, and 100 mM HEPPS (pH 8.0). The crystals were serially transferred over a period of ten minutes and flash frozen in the cryo stream. Each step was approximately two minutes in duration. X-ray data were collected at 100 K utilizing a BRUKER D8-VENTURE sealed tube system equipped with Helios optics and a PHOTON II detector. These diffraction data were processed with SAINT and scaled with SADABS (Bruker AXS). A partial model was initially obtained with MrBUMP using PDB entry 2PK3 as a starting model (23, 24). The model was completed and refined via iterative cycles of model building with COOT and refinement with REFMAC (25, 26). X-ray data collection and model refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

X-ray Data Collection Statistics and Model Refinement Statistics

| PDB code | 7US5 |

|---|---|

| Space Group | P21212 |

| Unit Cell (a, b, c, (Å)) | 112.7,182.9,75.4 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 50.0-2.1 (2.2 – 2.1)b |

| Number of independent reflections | 91209 (11616) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (98.6) |

| Redundancy | 6.9 (4.4) |

| avg I/avg σ(I) | 11.2 (3.0) |

| Rsym (%)a | 9.1 (37.0) |

| cR-factor (overall)%/no. reflections | 17.2/91209 |

| R-factor (working)%/no. reflections | 16.9/86637 |

| R-factor (free)%/no. reflections | 22.1/4572 |

| number of protein atoms | 11090 |

| number of heteroatoms | 1251 |

| average B values | |

| protein atoms (Å2) | 20.1 |

| ligand (Å2) | 14.4 |

| solvent (Å2) | 22.2 |

| weighted RMS deviations from ideality | |

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| bond angles (°) | 1.57 |

| planar groups (Å) | 0.007 |

| Ramachandran regions (%)d | |

| most favored | 97.9 |

| additionally allowed | 2.1 |

| generously allowed | 0.0 |

.

Statistics for the highest resolution bin.

x 100 where Fo is the observed structure-factor amplitude and Fc. is the calculated structure-factor amplitude.

Distribution of Ramachandran angles according to PROCHECK (27).

RESULTS

Bioinformatic Analysis.

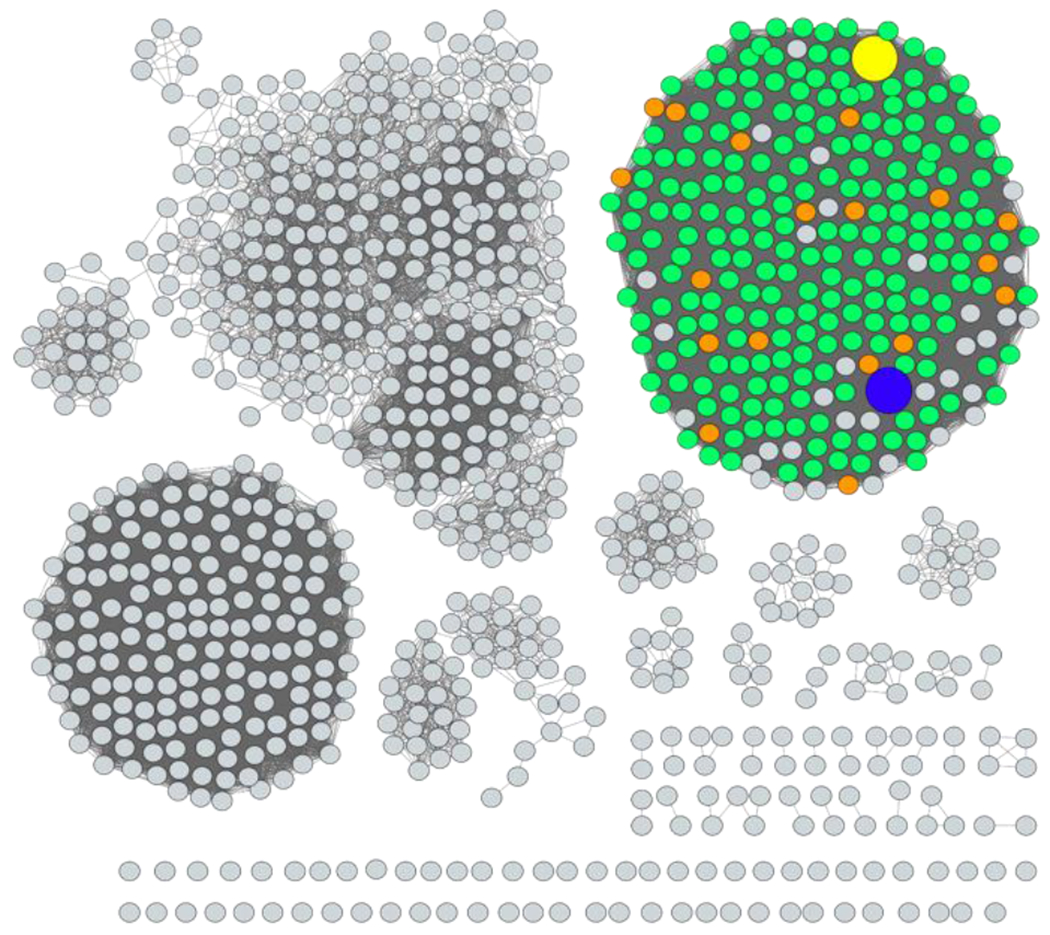

The sequence similarity network (SSN) of the 1000 closest homologues to the GMH dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 is presented in Figure 2 at a sequence identity of 68%. All of the sequences from any species of Campylobacter are depicted in green, while those specifically identified from C. jejuni are colored in orange. Two GMH dehydratases have been identified and isolated to date. The first is the dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 and the second is from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis O:2a (14, 28). A total of 19 sequences from the serotyped strains of C. jejuni was identified as being annotated as either GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase or GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase from the SSN. These serotypes include the following: HS:3, HS:4, HS:5, HS:8/17, HS:10, HS:11, HS:12, HS:15, HS:18, HS:23/36, HS:29, HS32/58, HS:41, HS:42, HS:45, HS:52, HS:53, HS:60, and HS:63. It is apparent that all of these strains of C. jejuni should incorporate a 6-deoxy-heptose moiety into their CPS. A multiple sequence alignment of these 19 enzymes indicates that they share a high sequence identity (89-98%), including four fully conserved residues (S-x-E and Y-x-x-x-K) within the family of GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratases that are currently thought to be essential for catalytic activity (Figure S2) (29).

Figure 2.

Sequence similarity network of the 1000 closest homologues to the GMH dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176. The alignment value cutoff was set to a 68% sequence identity. The sequences from C. jejuni and other Campylobacter species are colored orange and green, respectively. The sequence for the GMH dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 is shown as the yellow circle, while that from Y. pseudotuberculosis is shown in blue.

Purification of GMH Dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176.

The gene for the GMH dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 (HS:23/36) was expressed in E. coli and the enzyme purified to homogeneity. The as-purified enzyme was heat-denatured in an attempt to release any tightly bound cofactors. After filtration of the precipitated enzyme, the UV-vis spectrum of the isolated cofactor was obtained and is consistent with that of either NAD+ or NADP+ (Figure 3). The retention time for chromatographic separation on an anion exchange column was consistent with that of NAD+, as was the m/z of 662.10 for the [M-2H]- anion determined by ESI mass spectrometry.

Figure 3:

UV spectrum of the NAD+ isolated from the purified GMH dehydratase after heat denaturation. Additional details are available in the text.

Catalytic Properties and Product Identification.

The GMH dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 was previously reported to catalyze the formation of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) (14). We conducted the reaction in 50 mM NH4HCO3 buffer, in either H2O or D2O at pH 7.5 or pD 7.5, respectively, and the reaction products were confirmed using 1H NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. The 1H NMR spectrum of the substrate GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) is provided in Figure 4A, whereas the product produced in either D2O or H2O is presented in Figures 4B and 4C, respectively. The resonance assignments were made based upon the 2D 1H-COSY NMR spectra shown in Figure S3. The hydrogens attached to C6 of the product are clearly apparent at 1.96 and 2.35 ppm (Figures 4B and 4C) and the loss of the resonance for the hydrogen attached to C5 of the heptose moiety of the dehydratase product is clearly observed at 4.38 ppm ( compare Figures 4B and 4C) when the dehydratase reaction was conducted in D2O.

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectra of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) and the reaction product after the addition of GMH dehydratase. (A) GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3). (B) The reaction product, GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) when the reaction was conducted in D2O. In this product the hydrogen at C5 is deuterated. (C) The reaction product, GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) when the reaction was conducted in H2O. The hydrogens from the ribose moiety are labelled with an “R”, while those from the manno-heptose moiety are labelled with an “M”. Those resonances labelled with an “*” are from unidentified impurities.

The reaction product was also confirmed using mass spectrometry. The ESI-MS (negative ion mode) of the substrate GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) was obtained from a solution of 50 mM NH4HCO3 in either H2O (Figure 5A) or D2O (Figure 5B), respectively, at an m/z of 634.08 for the M-H anion. When the dehydratase reaction was conducted in H2O, the ESI-MS of the product gives an m/z of 616.08 for the M-H anion (Figure 5C), consistent with the loss of water and formation of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4). When the dehydratase reaction was conducted in D2O the reaction product has an m/z of 617.08 for the M-H ion consistent with the incorporation of a single deuterium at C5 (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Mass spectrometry data for the reactions catalyzed by GMH dehydratase. (A) GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) in H2O before the addition of enzyme. (B) GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) in D2O before the addition of enzyme. (C) Product of the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase when the reaction was conducted in H2O. (D) Product of the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase when the reaction was conducted in D2O. (E) Product of the reaction catalyzed by Cj1427 (17) when 3 was used as the substrate. The unreacted 3 appears at m/z of 634.07 and the product 7 appears at an m/z of 632.07. (F) Product of the reaction after incubation of GMH dehydratase with the reaction mixture formed from the addition of Cj1427 to 3 in the presence of α-ketoglutarate. Reaction products 8 (from 7) and 4 (from 3) appear at an m/z of 614.07, and 616.07, respectively.

Three-Dimensional Structure of GMH Dehydratase.

The structure of GMH dehydratase in complex with GDP was determined at 2.1 Å resolution and refined to an overall R-factor of 17.2%. The asymmetric unit contained a complete tetramer as shown in Figure 6A. The α-carbons for the four subunits of the tetramer superimpose with an average root-mean-square deviation of 0.4 Å. The total buried surface area of the tetramer, which displays D2 symmetry, is extensive at 14,000 Å2 with the A/B and C/D interfaces contributing 3,800 Å2 each and the A/D and B/C providing 2,500 Å2 each. The architecture of the GMH dehydratase subunit places it into the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase or SDR superfamily of proteins (30). Members of this family are typically dimers with several exceptions including the GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (31). Each subunit, which adopts a bilobal-type architecture, contains 11 α-helices and 11 β-strands. The N-terminal domain, responsible for NAD(H) binding, is dominated by a seven-stranded parallel β-sheet. The C-terminal motif contains four β-strands that form two β-sheets, one of which is parallel and the other antiparallel. The active site of the enzyme is wedged between the two domains.

Figure 6:

Structure of GMH dehydratase. Shown in (A) is a ribbon drawing of the tetramer as observed in the asymmetric unit. The bound ligands, GDP and NAD(H) are displayed in sphere representations. The observed electron density corresponding to the two ligands is shown in stereo in (B). The electron density map was calculated with (Fo-Fc) coefficients and contoured at 3σ. The ligands were not included in the X-ray coordinate file used to calculate the omit map, and thus there is no model bias. A closeup view of the active site, in stereo, is provided in (C) based on the simple superposition of the substrate onto the structure of GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (PDB accession code: 1N7G). The side chains are colored in teal, and the dashed lines indicate possible interactions within 3.2 Å in the modeled GDP-sugar substrate.

Shown in Figure 6B is a stereo view of the electron densities corresponding to the NAD(H) and GDP ligands. The ribose of the GDP ligand adopts the C-2’ endo pucker and the guanine ring is in the syn orientation. The two ribosyl moieties of NAD(H) also adopt the C-2’endo pucker. As expected for members of the SDR superfamily, the nicotinamide ring of the NAD(H) is in the syn conformation thereby allowing transfer of a hydride from the GDP-linked sugar substrate to its si face.

The α-carbons for the GMH dehydratase superimpose upon those for the Arabidopsis thaliana GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase/NADPH/GDP-rhamnose complex (PDB accession code: 1N7G) with a root-mean-square deviation of 1.5 Å (PDB accession code: 1N7G) (32). On the basis of the manner in which GDP-rhamnose binds to the GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase, it was possible to build a simple superposition model of the GDP-linked substrate into the GMH dehydratase active site as shown in stereo in Figure 6C. The positions of those residues selected for further investigation are presented in Figure 6C.

Kinetic Analysis of GMH Dehydratase.

The kinetic constants for the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase using GDP-d-glycero -α-d-manno-heptose (3) as the substrate are provided in Table 2. The catalytic efficiency for the wild-type GMH dehydratase is 2.7 × 104 M−1 s−1 with a kcat of 1.6 s-1. No activity (<0.001 s−1) could be detected for the S134A and E136Q variations. Significant reductions in the catalytic efficiencies (~1000-fold) were also noted for the Y159F and K163M variants. Relatively small reductions in catalytic activity were noted for the S134T, S135A, T188A, and Y301F variants.

Table 2.

Kinetic constants for reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratasea

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type | 1.64 ± 0.04 | 61 ± 6 | (2.7 ± 0.3) x 104 |

| S134A | ndb | nd | nd |

| S134T | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 50 ± 5 | (7.4 ± 0.7) x 103 |

| S135A | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 26 ± 3 | (8.8 ± 0.3) x 103 |

| E136Q | nd | nd | nd |

| Y159F | 0.0080 ± 0.0004 | 210 ± 11 | (3.8 ± 0.3) x 101 |

| K163M | 0.0020 ± 0.0001 | 55 ± 1 | (3.6 ± 0.1) x 101 |

| T188A | 0.330 ± 0.004 | 165 ± 9 | (2.0 ± 0.1) x 103 |

| Y301F | 0.082 ± 0.002 | 15 ± 2 | (5.6 ± 0.6) x 103 |

pH 7.5 and 30 °C

nd, not detectable.

Identification of Reaction Intermediates.

The proposed reaction mechanism for the conversion of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) to GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) is presented in Scheme 3 (16, 32–34). In the first step the tightly bound NAD+ is used to oxidize C4 of the substrate to generate GDP-d-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (7) and NADH. In the second step, water is eliminated from C5/C6 due to the increased acidity of the hydrogen at C5 to form intermediate 8. In the final step, the double bond between C5 and C6 is reduced by the tightly bound NADH that was formed in the first step to generate the ultimate product 4. To help confirm the putative reaction intermediates, the α-ketoglutarate dependent C4-dehydrogenase, Cj1427, from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2) was used to catalyze the transformation of GDP-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) to GDP-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (7) as illustrated in Scheme 4 (17). After introduction of Cj1427 and α-ketoglutarate to GDP-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (3) the ESI mass spectrum of the reaction mixture clearly indicates the formation of GDP-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (7) by the appearance of a new peak at an m/z of 632.07 for the M-H anion (Figure 5E). Unreacted 3 is also present as indicated by the peak with an m/z of 634.07. Unfortunately, we were unable to separate compounds 3 and 7 by anion exchange chromatography. After introduction of GMH dehydratase, two new peaks are apparent in the mass spectrum (Figure 5F). The peak at 614.07 is consistent with the formation of intermediate 8 since it is 18 mass units smaller than the presumptive substrate 7. By starting the reaction with the 4-keto oxidized substrate the enzyme is unable to reduce the double bond between C5 and C6 since the tightly bound NAD+ remains oxidized. The peak at 616.07 is consistent with the conversion of the substrate 3 to product 4.

Scheme 3:

Proposed reaction mechanism for the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase.

Scheme 4:

Formation of GDP-d-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (7) from GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose (3) catalyzed by Cj1427 in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and the subsequent dehydration of 7 to intermediate 8 catalyzed by GMH dehydratase.

DISCUSSION

Isolation and Characterization of GMH Dehydratase.

The GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 was purified to homogeneity after expression of the gene in E. coli. The as-purified enzyme contains a tightly bound NAD+ in the active site. DNA sequences for the expression of GMH dehydratase are found in 18 additional serotyped strains of C. jejuni. The multiple sequence alignment for these 19 proteins indicates an overall sequence identify of greater than 89%, and thus it is highly likely that each of these proteins will catalyze the same dehydratase reaction with the same substrate and provide the same product. Therefore, each of these strains of C. jejuni will utilize a 6-deoxy-heptose moiety within their capsular polysaccharide.

From the multiple protein sequence alignment and the corresponding structure determination reported here, four fully conserved residues were initially selected for substitution. These four residues included Ser-134, Glu-136, Tyr-159, and Lys-163. In addition to these residues, Ser-136 and Tyr-301 were also substituted since they appeared to be close to the putative binding site for the heptose sugar in the active site. However, the substitution of Ser-136 with alanine and the change of Tyr-301 to phenylalanine had relatively little effect on the catalytic activity of GMH dehydratase and thus these residues are relatively unimportant for catalytic function. For the Ser-134 and Glu-136 substitutions no catalytic activity could be measured, and with Tyr-159 and Lys-163 the loss of side chain functionality reduced the value of kcat/Km by approximately 3 orders of magnitude.

Reaction Mechanism.

It is generally accepted that the reaction mechanism for the 4,6-dehydratases involves two chemical intermediates as illustrated in Scheme 3 (16, 32–34). For GMH dehydratase, the tightly bound NAD+ first oxidizes C4 of the bound substrate to generate the 4-keto intermediate (7) and NADH. This product is the same as catalyzed by Cj1427 with the same substrate (17). In the second step, water is eliminated in either a concerted or stepwise fashion to make the unsaturated ketone with a double bond between C5 and C6 (8). In the final step the double bond is reduced to form GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (4) using the NADH that was made in the first step of the reaction. Support for the intermediacy of 7 and 8 in the reaction catalyzed by GMH dehydratase have been provided here by using 7 directly as a substrate. Intermediate 7 was synthesized enzymatically by the catalytic activity of Cj1427 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168. When a mixture of compounds 3 and 7 was added to GMH dehydatase, the mass spectrum of the product mixture clearly indicated that compound 3 (the normal substrate) was converted to product 4. In contrast, the enzymatic reaction of 7 with GMH dehydratase stopped after the dehydration step since the dehydratase in this transformation was never able to generate the NADH that is required to reduce the double bond to the ultimate 6-deoxy product. This is clearly shown in the Figure 5F. Previously, the Frey group has provided experimental support for an α,β-unsaturated keto intermediate in the reaction catalyzed by dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase using rapid-quench methods and mass spectrometry to obtain time courses for the appeance and decay of the proposed α,β-unsaturated intermediate (35).

Three-dimensional Structure of GMH dehydratase.

The structure of GMH dehydratase was determined in the presence of GDP and NAD(H) bound in the active site. The enzyme adopts a short chain dehydrogenase structural fold that resembles that of GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase from Arabidopsis thaliana (32). For the general reaction mechanism depicted in Scheme 3 the enzyme must provide at least two general acid/base groups within the active site to facilitate this reaction. In the first step a general base must abstract the proton from the C4-hydroxyl group as the hydrogen from C4 is transferred to the NAD+ in the active site to generate the 4-keto intermediate (7) and NADH. In the second step a general base must abstract a proton from C5 to initiate the dehydration reaction and a general acid must protonate the hydroxyl group at C6 to facilitate C-O bond cleavage to generate the α,β-unsaturated ketone intermediate (8). In the final step the tightly bound NADH transfers a hydride to C6 of the intermediate and a general acid donates a proton back to C5.

The three-dimensional structure of the GMH dehydratase with the substrate modeled into the active site (Figure 6C) has enabled a proposal for the role of individual amino acids in the chemical reaction mechanism as shown in Scheme 5. Here the general base for the abstraction of the proton from the C4-hydroxyl group is initiated by Tyr-159. The dehydration step is facilitated by the abstraction of the proton at C5 by Glu-136 and the negative charge is delocalized as an enolate. The functional importance for both Glu-136 and Tyr-159 is supported by the absolute sequence conservation and the significant reduction in catalytic activity upon mutation of these residues to non-acidic couterparts. The precise assignment of the residue that facilitates the protonation of the hydroxyl group at C6 is more problematic. However, the relative closeness of the side chain hydroxyl of Ser-134 suggests that this residue, in conjunction with the phenolic hydroxyl of Tyr-159, could facilitate proton transfer to the leaving group. In the final step, the now-protonated Glu-136 donates the hydrogen back to C5 in conjunction with hydride transfer to C6 from NADH.

Scheme 5:

Proposed reaction mechanism for GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase.

A similar reaction mechanism has been proposed by Pfeifer et al. for the human GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (34). Their mechanism, however, uses the protonated glutamate to facilitate proton transfer to the leaving group hydroxyl and then uses a bound water molecule to ultimately protonate C5 as the hydride is added to C6. The mechanism proposed here is more economical in the sense that the tyrosine and glutamate residues are in the same state of protonation at the beginning and at the end of the reaction cycle. In addition, the same glutamate is used to abstract and donate a proton back to C5, whereas in the mechanism proposed by Pfeiffer et al., the proton abstraction is initiated by the side chain carboxylate of glutamate but the reprotonation step at the same carbon is via a bound water molecule. The mechanism proposed here also suggests a significantly more active role for the side chain hydroxyl for the critically important Ser-134 residue.

CONCLUSIONS.

The GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase was purified to homogeneity and its three-dimensional structure determined to a resolution of 2.1 Å. The utilization of alternate substrates provided mechanistic support for the initial NAD+-dependent formation of a 4-keto intermediate followed by the loss of water between C5 and C6 to generate an α/β-unsaturated 4-keto intermediate that is subsequently reduced by the tightly bound NADH that was formed during the oxidation of C4. A bioinformatic analysis identified 19 4,6-dehydratases from serotyped strains of C. jejuni that are 89-98% identical in amino acid sequence, indicating that each of these strains will contain a 6-deoxy-heptose within their capsular polysaccharide.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was funded the National Institutes of Health (GM 139428 and GM122825 to FMR and GM 134643 to HMH).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Amino acid sequences of the proteins purified for this investigation and multi-protein sequence alignment for 19 GMH dehydratases identified in the serotyped strains of Campylobacter jejuni. NMR spectra for substrate and product from the catalytic activity of GMH dehydratase.

Accession Codes

Cjj1426 from C. jejuni 81-176 (WP_002869408)

Cje1612 from C. jejuni RM1221 (WP_002867270.1)

Cj1427 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (WP_002858299.1)

The authors declare no competing conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heimesaat MM, Backert S, Alter T, Bereswill S (2021) Human Campylobacteriosis-a serious infectious threat in a one health perspective. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 431, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasti JI, Tareen AM, Lugert R, Zautner AZ, Gross U (2010) Campylobacter jejuni: a brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. Int J Med Microbiol. 300, 205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermans D, Pasmans F, Messens W, Martel A, Immerseel FV, Rasschaert G, Heyndrickx M, Deun KV, Haesebrouck F (2012) Poultry as a host for the zoonotic pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 12, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphrey S, Chaloner G, Kemmett K, Davidson N, Williams N, Kipar A, Humphrey T, and Wigley P (2014) Campylobacter jejuni is not merely a commensal in commercial broiler chickens and affects bird welfare. mBio 5, e01364–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Facciola A, Riso R, Avventuroso E, Visalli G, Delia SA, and Lagana P (2017) Campylobacter: from microbiology to prevention. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 58, E79−E92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Igwaran A, Okoh AF (2019) Human campylobactriosis: a public health concern of global importance. Heliyon 5, e02814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyati KK, and Nyati R (2013) Role of Campylobacter jejuni infection in the pathogenesis of Guillain-Barré syndrome: an update, Biomed Res Int 2013, 852195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riegert AS, Narindoshvili T, Coricello A, Richards NGJ, and Raushel FM (2021) Functional characterization of two PLP-dependent enzymes involved in capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis from Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 60, 2836−2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monteiro MA, Chen YH, Ma Z, Ewing CP, Nor NM, Omari E, Song E, Gabryelski P, Guerry P, Poly F (2021) Relationships of capsular polysaccharides belonging to Campylobacter jejuni HS1 serotype complex. PLOS ONE 16(2), e0247305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monteiro MA, Baqar S, Hall ER, Chen YH, Porter CK, Bentzel DE, Applebee L, and Guerry P (2009) Capsule polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against diarrheal disease caused by Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immun. 77, 1128–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huddleston JP, and Raushel FM (2019) Biosynthesis of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose for the capsular polysaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni, Biochemistry, 58, 3893–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerry P, Poly F, Riddle M, Maue AC, Chen Y-H, and Monteiro MA (2012) Campylobacter polysaccharide capsules: virulence and vaccines. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2, article 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thota VN, Ferguson MJ, Sweeney RP, and Lowary TL (2018) Synthesis of the Campylobacter jejuni 81-176 strain capsular polysaccharide repeating unit reveals the absolute configuration of its O-methyl phosphoramidate motif. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 57, 15592–15596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCallum M, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2011) Characterization of the dehydratase WcbK and the reductase WcaG involved in GDP-6-deoxy-d-manno-heptose biosynthesis in Campylobacter jejuni. Biochem. J. 439, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCallum M, Shaw SD, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2012) Complete 6-deoxy-d-altro-heptose biosynthesis pathway from Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29776–29788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogel U, Beerens K, Desmet T (2022) Nucleotide sugar dehydratases: structure, mechanism, substrate specificity, and application potential. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 101809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huddleston JP, Raushel FM (2020) Functional characterization of Cj1427, a unique ping-pong dehydrogenase responsible for the oxidation of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose in Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 59, 1328–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCallum M, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2013) Comparison of predicted epimerases and reductases of the Campylobacter jejuni d-altro- and l-gluco-heptose synthesis pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19569−19580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huddleston JP, Anderson TK, Spencer KD, Thoden JB, Raushel FM, and Holden HM (2020) Structural analysis of Cj1427, an essential NAD-dependent dehydrogenase for the biosynthesis of the heptose residues in the capsular polysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry, 59, 1314–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnawi H, Woodward L, Eava N, Roubakha M, Shaw SD, Kubinec C, Naismith JH, Creuzenet C (2021) Structure-function studies of the C3/C5 epimerases and C4 reductases of the Campylobacter jejuni capsular heptose modification pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCallum M, Shaw SD, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2012) Complete 6-deoxy-d-altro-heptose biosynthesis pathway from Campylobacter jejuni: more complex than anticipated. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29776–29788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerlt JA, Bouvier JT, Davidson DB, Imker HJ, Sadkhin B, Slater DR, and Whalen KL (2015) Enzyme function initiative enzyme similarity tool (EFI-EST): a web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1854, 1019−1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keegan RM, and Winn MD (2008) MrBUMP: an automated pipeline for molecular replacement, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64, 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King JD, Poon KKH, Webb NA, Anderson EM, McNally DJ, Brisson JR, Messner P, Garavito RM, and Lam JS (2009) The structural basis for catalytic function of GMD and RMD, two closely related enzymes from the GDP-d-rhamnose biosynthesis pathway, FEBS J 276, 2686–2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delano W (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski RA, Moss DS, and Thornton JM (1993) Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures, J Mol Biol 231, 1049–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butty FD, Aucoin M, Morrison L, Ho N, Shaw G, Creuzenet C (2009) Elucidating the formation of 6-deoxyheptose: biochemical characterization of the GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose C6 dehydratase, DmhA, and its associated C4 reductase, DmhB. Biochemistry 48, 7764–7775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa MD, Gevaert O, Overtveldt SV, Lange J, Joosten H-J, Desmet T, Beerens K, (2021) Structure-function relationships in NDP-sugar active SDR enzymes: fingerprints for functional annotation and enzyme engineering. Biotechnology Advances 48, 107705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persson B, Kallberg Y, Bray JE, Bruford E, Dellaporta SL, Favia AD, Duarte RG, Jornvall H, Kavanagh KL, Kedishvili N, Kisiela M, Maser E, Mindnich R, Orchard S, Penning TM, Thornton JM, Adamski J, and Oppermann U (2009) The SDR (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase and related enzymes) nomenclature initiative, Chem Biol Interact 178, 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb NA, Mulichak AM, Lam JS, Rocchetta HL, and Garavito RM (2004) Crystal structure of a tetrameric GDP-d-mannose 4,6-dehydratase from a bacterial GDP-d-rhamnose biosynthetic pathway, Protein Sci 13, 529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulichak AM, Bonin CP, Reiter WD, and Garavito RM (2002) Structure of the MUR1 GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase from Arabidopsis thaliana: implications for ligand binding and specificity, Biochemistry 41, 15578–15589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somoza JR, Menon S, Schmidt H, Joseph-McCarthy D, Dessen A, Stahl ML, Somers WS, Sullivan FX (2000) Structural and kinetic analysis of Escherichia coli GDP-mannose 4,6 dehydratase provides insights into the enzyme’s catalytic mechanism and regulation by GDP-fucose. Structure 8, 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeiffer M, Johansson C, Krojer T, Kavanagh KL, Oppermann U, Nidetzky B (2019) A parsimonious mechanism of sugar dehydration by human GDP-mannose-4,6-dehydratase. ACS Catal. 9, 2962−2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross JW, Hegeman AD, Vestling MM, Frey PA (2000) Characterization of enzymatic processes by rapid mix-quench mass spectrometry: the case of dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase. Biochemistry 39, 13633–13640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.