Abstract

Neurocysticercosis (NC), caused by the presence of Taenia solium metacestodes in tissues, is a severe parasitic infection of the central nervous system with universal distribution. To determine the efficiency of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoblot with antigens of T. crassiceps vesicular fluid (Tcra) compared to standard techniques (indirect immunofluorescence test [IFT] and complement fixation test [CFT]) using T. solium cysticerci (Tso) for the serodiagnosis of NC, we studied serum samples from 24 patients with NC, 30 supposedly healthy individuals, 76 blood bank donors, 45 individuals with other non-NC parasitoses, and 97 samples from individuals screened for cysticercosis serology (SC). The sensitivity observed was 100% for ELISA-Tso and ELISA-Tcra, 91.7% for the IFT, and 87.5% for the CFT. The specificity was 90% for ELISA-Tso, 96.7% for ELISA-Tcra, 50% for IFT, and 63.3% for CFT. The efficiency was highest for ELISA-Tcra, followed by ELISA-Tso, IFT, and CFT. Of the 23 samples from SC group, which were reactive to ELISA-Tso and/or ELISA-Tcra, only 3 were positive to immunblot-Tcra (specific peptides of 14- and 18-kDa) and to glycoprotein peptides purified from Tcra antigen (gp-Tcra), showing the low predictive value of ELISA for screening. None of the samples from the remaining groups showed specific reactivity in immunoblot-Tcra. These results demonstrate that ELISA-Tcra can be used as a screening method for the serodiagnosis of NC and support the need for specific tests for confirmation of the results. The immunoblot can be used as a confirmatory test both with Tcra and gp-Tcra, with the latter having an advantage in terms of visualization of the results.

Neurocysticercosis (NC), the presence of Taenia solium metacestodes in tissues, is a severe parasitic infection of the central nervous system. Its distribution is universal, being frequent in developing countries in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and India (1, 7, 19, 21). Cases have also been reported in the United States due to the immigration of individuals coming from areas where this parasite is endemic (20).

The diagnosis of NC is based on clinical and epidemiological criteria and on laboratory methods (neuroimaging and immunological methods). Clinical diagnosis is impaired by the polymorphic and nonspecific symptoms of NC, and the detection of anti-cysticercus antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) represents an important diagnostic element. However, a spinal puncture for CSF collection requires specialized professionals, being indicated only for symptomatic patients. The detection of antibodies in serum is impaired by cross-reactions with other parasitoses and requires the use of purified antigens (24).

The preparation of adequate antigen extracts in sufficient amounts for NC diagnosis is still linked to the detection of swine naturally infected with T. solium larvae, which are usually reared in clandestine conditions and are difficult to locate (2, 7, 15, 26). The use of synthetic peptides from T. solium cysticerci has been described, and this strategy would provide enough antigens for diagnostic assays (8, 9).

Another approach is the possibility of choosing an alternative manner of detecting the parasites arises from the observation that the Taenia species share common antigens (15, 18). The ORF strain of T. crassiceps (6) represents an important experimental model which, according to comparative studies, can be used for the immunodiagnosis of NC (2, 15, 25, 26).

The objective of the present study was to determine the efficiency of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoblot with antigens of T. crassiceps vesicular fluid compared to standard techniques with T. solium cysticerci, in order to propose a criterion for the laboratory screening of cysticercosis in serum samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

The serum samples used in this study were obtained from 24 patients with NC (NC), 30 supposedly healthy individuals (C), 76 blood bank donors (BB), and 45 individuals with other non-NC parasitoses (OP). In addition, 97 serum samples from individuals medically screened for cysticercosis serology (screening serologic [SC]) were used. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee for the analysis of Research Projects of the Clinical Director's Office of the Hospital 072/97, according to Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council, Ministry of Health, Brazil.

Antigens.

Antigen extracts were obtained from the vesicular fluid of T. crassiceps cysticerci (Tcra) and from the membrane and scolex of T. solium cysticerci (Tso) as described before (2). The Tcra antigen was purified in order to obtain glycoprotein peptides (gp-Tcra) of low molecular mass (18 and 14 kDa) by elution in preparative sodium dodecyl sultate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (PrepCell 491; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The fractions were collected and analyzed by silver stain. The fractions of interest were pooled and concentrated.

IFT and CFT.

Antibody detection by the indirect immunofluorescence test (IFT) and complement fixation test (CFT) was adapted for use in serum samples according to the protocols of the Neurology Investigation Center of the Faculty of Medicine of São Paulo University (22).

ELISA-Tcra, ELISA-Tso, and immunoblot-Tcra.

T. solium anti-cysticercus immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in serum samples diluted at 1:100 were determined by ELISA using Tcra and Tso antigens and by immunoblot using Tcra antigens, as described previously (2). The reactivity index (RI) was calculated by using the obtained absorbance divided by the cutoff (mean absorbance for the control group plus two standard deviations).

Immunoblot gp-Tcra.

Some ELISA and/or immunoblot-Tcra-reactive samples were processed for the identification of specific peptides in the gp-Tcra antigen (immunoblot gp-Tcra). Positive, negative, and background controls were included in each test. gp-Tcra antigen at 1:50 dilution was fractionated by SDS-PAGE on a 15% gel (13) and transferred electrophoretically to 0.22-μm (pore-size) nitrocellulose membranes (Immobilon-PSQ Transfer Membrane; Millipore) (23) that were cut into 3- to 4-mm-wide strips. Phosphate-buffered saline at 0.01 M (pH 7.2; 0.0075 M Na2HPO4, 0.025 M NaH2PO4, and 0.14 M NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20 was used for the washes and for the preparation of skim milk. The strips were blocked for 2 h with 5% milk, and the serum samples were diluted 1:100 with 1% milk and incubated for 18 h at 4°C. The conjugate used was alkaline phosphatase-goat anti-human IgG (Sigma Chemical Co.) incubated for 2 h. Reactive fractions were developed with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (NBT-BCIP; Sigma Chemical Co.). Molecular weight markers were used for calculating the molecular mass of the reactive fractions (14).

RESULTS

The results obtained for all sample groups by all tests are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

ELISA, IFT, and CFT resultsc

| Group | RI range (mean ± SD)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA-Tcraa | ELISA-Tsoa | IFTb | CFTb | |

| NC | 0.348–2.941 (1.586 ± 0.790) | 0.549–2.678 (1.576 ± 0.664) | 0–320 (65 ± 28) | 0–256 (42 ± 3) |

| SC | 0.074–2.387 (0.276 ± 0.351) | 0.062–2.595 (0.335 ± 0.375) | 0–320 (25 ± 25) | 0–128 (6 ± 4) |

| C | 0.093–0.681 (0.272 ± 0.138) | 0.091–0.994 (0.214 ± 0.169) | 0–80 (17 ± 19) | 0–64 (12 ± 3) |

| BB | 0.079–2.111 (0.311 ± 0.335) | 0.121–1.025 (0.330 ± 0.168) | 0–40 (12 ± 15) | 0–64 (9 ± 3) |

| OP | 0.079–2.066 (0.376 ± 0.453) | 0.114–1.456 (0.328 ± 0.225) | 0–320 (20 ± 23) | 0–256 (13 ± 4) |

Optical density; arithmetic mean.

Geometric mean (IFT = 2n × 10; CFT = 2n); title = 1/dilution.

Results shown are for serum samples from patients with NC, subjects medically screened for SC, supposedly healthy individuals (C), blood bank donors (BB), and individuals with other non-NC parasitoses (OP) by ELISA with Tso or with Tcra, by IFT, and by CFT.

Considering a cutoff of 1:20, IFT showed reactivity in 22 (91.7%) samples from patients with NC, 15 (50%) samples from supposedly healthy individuals, 17 (22.4%) samples from blood bank donors, 23 (51.1%) samples from individuals with other parasitoses, and 57 (58.8%) samples from screening serologic group. The reactivity detected with CFT, considering a reactivity threshold of 1:32, was 87.5% (21 of 24) for patients with NC, 36.7% (11 of 30) for supposedly healthy individuals, 21.0% (16 of 76) for blood bank donors, 35.5% (16 of 45) for individuals with other parasitoses, and 22.7% (22 of 97) for the screening serologic group.

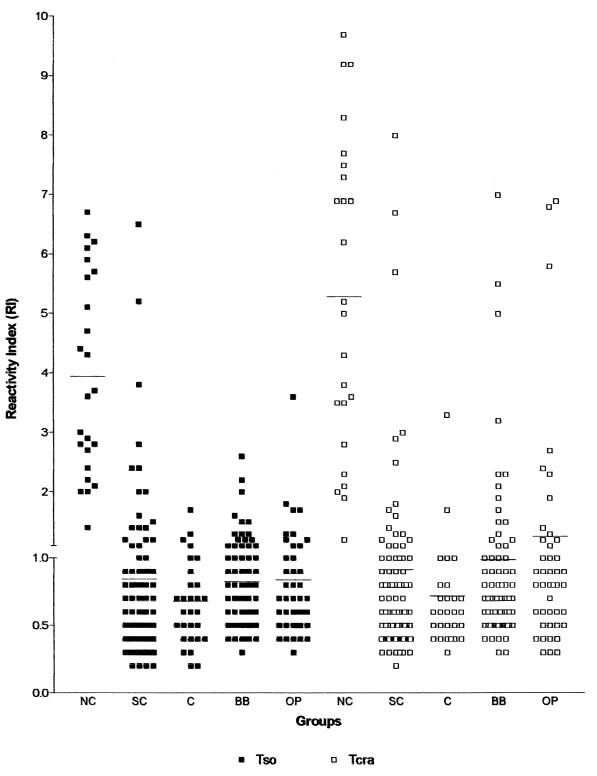

The results obtained by ELISA-Tso and -Tcra with serum samples from patients with NC, from subjects medically screened for SC, supposedly healthy individuals (C), blood bank donors (BB), and individuals with other non-NC parasitoses (OP) are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

RI obtained in ELISA with Tso and Tcra in serum samples from 24 patients with NC, 97 subjects submitted to medical screening for SC, 30 supposedly healthy individuals (C), 76 blood bank donors (BB), and 45 individuals with other non-NC parasitoses (OP).

ELISA-Tso showed RIs of 1.4 to 6.7 (3.9 ± 1.7) for the samples from patients with NC (24 of 24, RI ≥ 1.0), 0.2 to 1.7 (0.7 ± 0.3) for supposedly healthy individuals (6 of 30, RI ≥ 1.0, 3 of 30, RI ≥ 1.2), 0.3 to 2.6 (0.8 ± 0.4) for blood bank donors (22 of 76, RI ≥ 1.0, 12 of 76, RI ≥ 1.2), 0.3 to 3.6 (0.8 ± 0.5) for individuals with other parasitoses (12 of 45, RI ≥ 1.0, 8 of 45, RI ≥ 1.2), and 0.2 to 6.5 (0.8 ± 0.9) for the screening serologic group (20 of 97, RI ≥ 1.0; 16 of 97, RI ≥ 1.2).

The RIs detected with ELISA-Tcra were 1.2 to 9.7 (5.3 ± 2.6) for patients with NC (24 of 24, RI ≥ 1.0), 0.3 to 3.3 (0.7 ± 0.5) for supposedly healthy individuals (5 of 30, RI ≥ 1.0; 1 of 30, RI ≥ 1.2), 0.3 to 7.0 (1.0 ± 1.1) for blood bank donors (20 of 76, RI ≥ 1.0; 14 of 76, RI ≥ 1.2), 0.3 to 6.9 (1.2 ± 1.5) for individuals with other parasitoses (15 of 45, RI ≥ 1.0; 11 of 45, RI ≥ 1.2), and 0.2 to 8.0 (0.9 ± 1.2) for screening serologic group (23 of 97, RI ≥ 1.0; 13 of 97, RI ≥ 1.2).

Table 2 shows the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA, IFT, and CFT in the analysis of the results from the NC and C groups.

TABLE 2.

Assay sensitivities and specificitiesa

| Test | NC group (n = 24)

|

C group (n = 30)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Sensitivity | RI | % Specificity | RI | |

| ELISA-Tso | 100 | ≥1.0 | 80 | ≥1.0 |

| 100 | ≥1.2 | 90 | ≥1.2 | |

| ELISA-Tcra | 100 | ≥1.0 | 83.3 | ≥1.0 |

| 100 | ≥1.2 | 96.7 | ≥1.2 | |

| IFT | 91.7 | 50.0 | ||

| CFT | 87.5 | 63.3 | ||

Sensitivity and specificity of ELISA with Tso and Tcra, of IFT, and of CFT with samples from patients with NC and from supposedly healthy individuals (C), with RI cutoffs of 1.0 and 1.2 for the ELISA.

The agreement indices obtained for ELISA-Tso and ELISA-Tcra, considering RI ≥ 1.0 and RI ≥ 1.2 were 90 and 93.3% for the groups of supposedly healthy individuals, 78.9 and 85.5% for the blood donor group, 76.1 and 78.3% for the groups of individuals with other parasitoses, and 78.3 and 83.5% for the routine samples, respectively. The agreement indices for the results of samples from patients with NC were 100%.

The agreement indices of the results obtained by the various tests (ELISA-Tso, ELISA-Tcra, IFT, and CFT) were 46.7% (RI ≥ 1.0) and 53.3% (RI ≥ 1.2) for supposedly normal individuals, 44.7% (RI ≥ 1.0) and 56.6% (RI ≥ 1.2) for blood bank donors, 26.7% (RI ≥ 1.0) and 33.3% (RI ≥ 1.2) for individuals with other parasitoses, 33.7% (RI ≥ 1.0) and 36.7% (RI ≥ 1.2) for the screening serologic group, and 83.37% (RI ≥ 1.0 and 1.2) for patients with NC.

The immunoblot-Tcra was negative for all samples from supposedly healthy individuals, blood donors, and patients with other parasitoses, including those with positivity by one or more tests. Reactivity for <20-kDa peptides was observed in the NC group, as previously reported (2). Of the screening serologic samples, three were reactive to immunoblot-Tcra; all of them were confirmed by immunoblot gp-Tcra and positive to ELISA-Tcra (RIs = 6.7, 3.0, and 1.7), two of them were reactive to ELISA-Tso (RIs = 5.2, 1.6, and 0.7), two were reactive to IFT (1:160, 1:20, and negative), and only one was reactive to CFT (1:32).

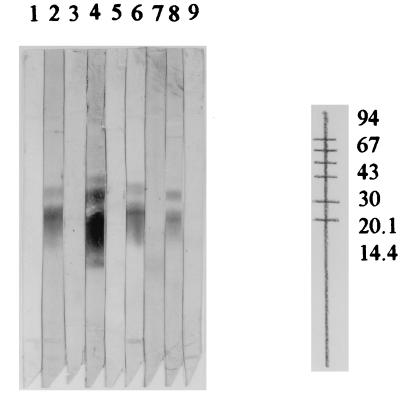

Figure 2 shows the immunoblot-gp of some samples from the groups of patients with NC, from supposedly healthy individuals, and from routine samples.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot with purified T. crassiceps antigen (gp-Tcra) from samples from patients with NC (lanes 2 and 4), from supposedly healthy individuals (lanes 3 and 5), and from positive (lanes 6 and 8) and negative (lanes 7 and 9) routine samples. Lane 1, background (with no sample) control.

DISCUSSION

In NC, most of the antibodies found in CSF are intrathecally synthesized, with a smaller proportion coming from peripheral blood due to blood-brain barrier rupture (4). Several authors have detected IgG antibodies in CSF and/or serum from patients with NC, especially when the parasite is in the phase of degeneration and there is an increased immune inflammatory host response (3, 4, 5).

The ELISA and immunoblot test has been used in the study of NC, and different indices of sensitivity and specificity have been observed depending on the antigen preparation, the type and severity of the lesions, and the inflammatory reaction surrounding the parasite (2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 24, 26, 27).

The results obtained here with ELISA-Tcra showed slightly higher readings than those obtained with ELISA-Tso regardless of the group studied (Fig. 1), as previously described (2). All of the tests performed always showed higher conegativity than copositivity indices for the samples from individuals with other parasitoses and from blood donors and for the screening serologic group. Better agreement indices were observed when a cutoff of 1.2 was considered for the ELISA.

The choice of the cutoff for ELISA can determine a better efficiency of the test. An RI of ≥1.2 resulted in a higher specificity without altering the sensitivity. Considering the immunoblot as confirmatory for the specificity of the antibodies, the use of an RI of ≥1.2 for ELISA-Tcra detected the three samples in the SC group. Thus, for clinical laboratory use, a high cutoff is preferable in order to reduce the number of confirmatory tests. On the other hand, studies using the test for epidemiologic survey purposes are still necessary.

The sensitivity and specificity indices showed a better efficiency of ELISA-Tcra, followed by ELISA-Tso, IFT, and CFT in decreasing order of efficiency (Table 2). In addition to a better performance, ELISA has other advantages, such as rapid execution, the possibility of testing several samples at the same time, and automated reading that eliminates the subjectivity present in IFT.

Although ELISA-Tcra and ELISA-Tso showed similar sensitivity and specificity, the easy preparation and reproducibility of the lots of Tcra antigen favors the latter method for the diagnosis of NC (2, 5, 15, 25, 26).

The sensitivity (100%) of ELISA applied to serum samples showed that the test can be used as a screening method for the serodiagnosis of NC as long as positive cases are confirmed by immunoblot. Of the 23 samples in the SC group that were reactive to ELISA-Tso and/or -Tcra (RI ≥ 1.2), only 3 were positive by immunblot-Tcra and immunoblot gp-Tcra, showing the low predictive value of ELISA for screening. The very low frequency of positivity in the SC group (3 of 97 [3%]) was expected if we assume that the medical request for a test is frequently used to exclude the hypothesis of NC, since the most probable cases are referred to a neurology clinic which will use neuroimaging and CSF exams. These results emphasize the need for specific tests for confirmation of the results, as also reported by others (24). In a previous study we demonstrated the viability of the use of ELISA-Tcra in serum samples, as well as the need to confirm positive cases by immunoblot (2). Other authors have used only the immunoblot for NC diagnosis (24), but it is expensive for use in developing countries.

Although the results of immunoblot demonstrated that both the Tcra antigen and the purified gp-Tcra antigen can be used to confirm the positivity of ELISA, the use of the gp-Tcra antigen has advantages in terms of interpretation of the results due to its constitution (only two peptides of 14 and 18 kDa, both of them specific).

The preparation of purified antigens (Fig. 2) could be useful for ELISA, with a probable persistence of sensitivity and increased specificity. So far we have not obtained good results with gp-Tcra to sensitize the polystyrene plates (data not shown), probably because of the impairment of adsorption of glycoprotein structures, which is overcome when nitrocellulose is used in the immunoblot. A further perspective is the obtaining of recombinant antigens and/or synthetic peptides from T. crassiceps. This approach would provide a more consistent and reproducible supply of protein antigens for use in NC immunodiagnosis, as recently described with T. solium cysticerci (8, 9).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Part of this work was supported by FAPESP (97-02245-6) and PIQDT/CAPES fellowship (Ednéia Casagranda Bueno). We are indebted to Regina H. S. Peralta for technical assistance with the preparation of gp-Tcra antigen; to Luis dos Ramos Machado and José Antônio Livramento for providing samples from patients with NC; to Fleury Laboratory for permitting the use of their laboratory facilities, for the execution of some tests and for providing the other samples; and to Silene Migliorini for technical assistance with preparation of preparation of membranes with Tcra antigen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agapejev S. Epidemiology of neurocysticercosis in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1996;38:207–216. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651996000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bueno E C, Vaz A J, Machado L R, Livramento J A, Mielle S R. Specific Taenia crassiceps and Taenia solium antigenic peptides for neurocysticercosis immunodiagnosis using serum samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:146–151. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.146-151.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espinoza B, Ruiz-Palacios G, Tovar A, Sandoval M A, Plancarte A, Flisser A. Characterization by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of the humoral immune response in patients with neurocysticercosis and its application in immunodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:536–541. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.4.536-541.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estanol B, Juarez H, Irigoye M D C, Gonzales-Barranco D, Corona T. Humoral immune response in patients with cerebral parenchymal cysticercosis treated with praziquantel. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1989;52:254–257. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira A P, Vaz A J, Nakamura P M, Sasaki A T, Ferreira A W, Livramento J A. Hemagglutination test for the diagnosis of human neurocysticercosis: development of a stable reagent using homologous and heterologous antigens. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1997;39:29–33. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651997000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman R S. Studies on the biology of Taenia crassiceps (ZEDER, 1800) Rudolphi, 1810 (cestoda) Can J Zool. 1962;40:969–990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia E, Ordonez G, Sotelo J. Antigens from Taenia crassiceps used in complement fixation, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and Western blot (immunoblot) for diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3324–3325. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3324-3325.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottstein B, Zini D, Schantz P M. Species-specific immunodiagnosis of Taenia solium cysticercosis by ELISA and immunoblotting. Trop Med Parasitol. 1987;38:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene R M, Wilkins P P, Tsang V C W. Diagnostic glycoproteins of Taenia solium cysts share homologous 14- and 18-kDa subunits. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene R M, Hancock K, Wilkins P P, Tsang V V W. Taenias solium: molecular cloning and serologic evaluation of 14- and 18-kDa related, diagnostic antigens. J Parasitol. 2000;86:1001–1007. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[1001:TSMCAS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grogl M, Estrada J J, Macdonald G, Kuhn R E. Antigen-antibody analyses in neurocysticercosis. J Parasitol. 1985;71:433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunz J, Kalinna B, Watschke V, Geyer E. Taenia crassiceps metacestode vesicular fluid antigens shared with the Taenia solium larval stage and reactive with serum antibodies from patients with neurocysticercosis. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1989;271:510–520. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(89)80113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambin P, Rochu D, Fine J M A. A new method for determination of molecular weights by electrophoresis across a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gradient gel. Anal Biochem. 1976;74:567–575. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larralde C, Sotelo J, Montoya R M, Palencia G, Padilla A, Govezensky T, Diaz M L, Sciutto E. Immunodiagnosis of human cysticercosis in cerebrospinal fluid. Antigens from murine Taenia crassiceps cysticerci effectively substitute those from porcine Taenia solium. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:926–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michault A, Rivière B, Fressy P, Laporte J P, Bertil G, Mignard C. Apport de l'enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay au diagnostic de la neurocysticercose humaine. Pathol Biol. 1990;38:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michel P, Michault A, Gruel J C, Coulanges P. Le serodiagnostic de la cysticercose par ELISA et Western blot. Son intérêt et ses limites à Madagascar. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1990;57:115–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivo A, Plancarte A, Flisser A. Presence of antigen B from Taenia solium cysticercus in other platyhelminthes. Int J Parasitol. 1988;18:543–545. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarti E, Flisser A, Schantz P M, Gleizer M, Loya M, Plancarte A, Avila G, Allan J, Craig P, Bronfaman M, Wijeyaratne P. Development and evaluation of a health education intervention against Taenia solium in a rural community in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:127–132. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schantz P M, Moore A C, Munoz J L, Hartman B J, Schaefer J A, Aron A M, Persaud D, Sarti E, Wilson M, Flisser A. Neurocysticercosis in an Orthodox Jewish community in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:692–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh G. Neurocysticercosis in South-Central America and the Indian Subcontinent. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1997;55:349–356. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1997000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spina-França A, Livramento J A, Machado L R. Cysticercosis of the central nervous system and cerebrospinal fluid. Immunodiagnosis of 1573 patients in 63 years (1929–1962) Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1993;1:16–20. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1993000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsang V C W, Brand J A, Boyer A E. An enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay and glycoprotein antigens for diagnosing human cysticercosis (Taenia solium) J Infect Dis. 1989;159:50–59. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaz A J, Nakamura P M, Barreto C C, Ferreira A W, Livramento J A, Machado A B B. Immunodiagnosis of human neurocysticercosis: use of heterologous antigenic particles (Cysticercus longicollis) in indirect immunofluorescence test. Serodiagn Immunother Infect Dis. 1997;8:157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaz A J, Nunes C M, Piazza R M F, Livramento J A, Silva M V, Nakamura P M, Ferreira A E. Immunoblot with cerebrospinal fluid from patients with neurocysticercosis using antigen from cysticerci of Taenia solium and Taenia crassiceps. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:354–357. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson M, Bryan R T, Fried J A, Ware D A, Schantz P M, Pilcher J B, Tsang V C W. Clinical evaluation of the cysticercosis enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot in patients with neurocysticercosis. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:1007–1009. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]