Abstract

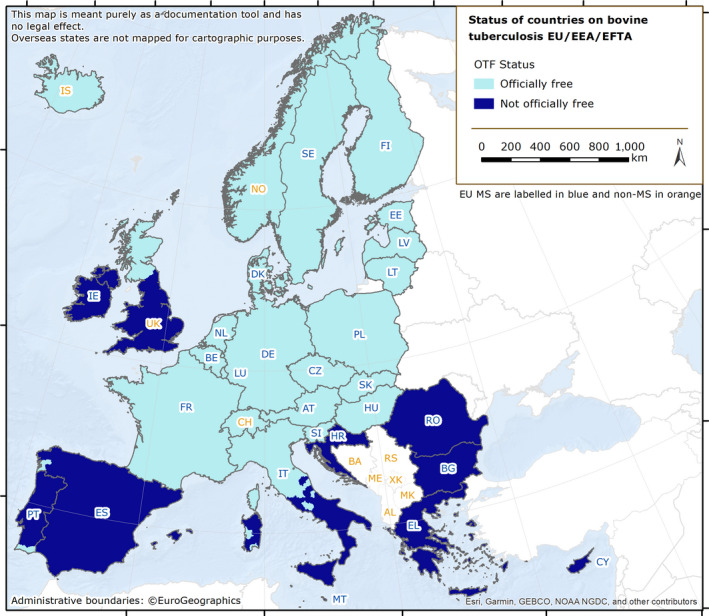

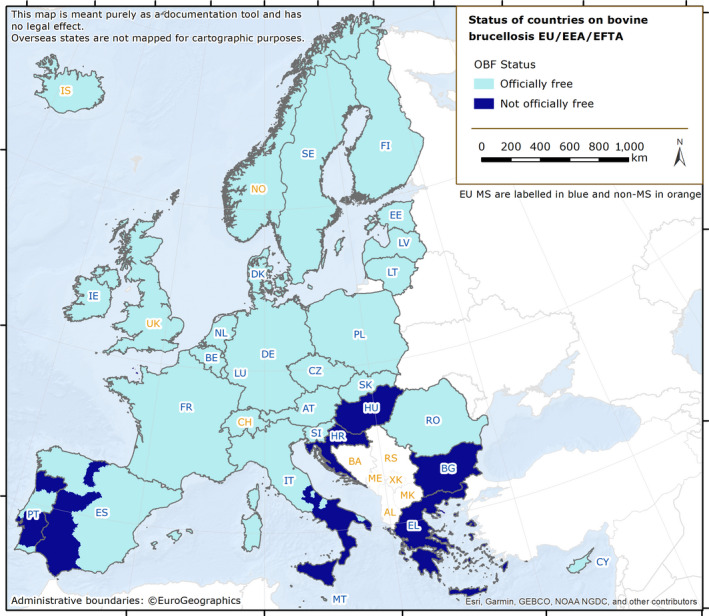

This report of the EFSA and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control presents the results of zoonoses monitoring activities carried out in 2020 in 27 EU Member States (MS) and nine non‐MS. Key statistics on zoonoses and zoonotic agents in humans, food, animals and feed are provided and interpreted historically. Two events impacted 2020 MS data collection and related statistics: the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic and the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU. In 2020, the first and second most reported zoonoses in humans were campylobacteriosis and salmonellosis, respectively. The EU trend for confirmed human cases of these two diseases was stable (flat) from 2016 to 2020. Fourteen of the 26 MS reporting data on Salmonella control programmes in poultry met the reduction targets for all poultry categories. Salmonella results for carcases of various species performed by competent authorities were more frequently positive than own‐checks conducted by food business operators. This was also the case for Campylobacter quantification results from broiler carcases for the MS group that submitted data from both samplers, whereas overall at EU level, those percentages were comparable. Yersiniosis was the third most reported zoonosis in humans, with 10‐fold less cases reported than salmonellosis, followed by Shiga toxin‐producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and Listeria monocytogenes infections. Illnesses caused by L. monocytogenes and West Nile virus infections were the most severe zoonotic diseases with the highest case fatality. In 2020, 27 MS reported 3,086 foodborne outbreaks (a 47.0% decrease from 2019) and 20,017 human cases (a 61.3% decrease). Salmonella remained the most frequently reported causative agent for foodborne outbreaks. Salmonella in ‘eggs and egg products’, norovirus in ‘crustaceans, shellfish, molluscs and products containing them’ and L. monocytogenes in ‘fish and fish products’ were the agent/food pairs of most concern. This report also provides updates on tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis or Mycobacterium caprae, Brucella, Trichinella, Echinococcus, Toxoplasma, rabies, Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) and tularaemia.

Keywords: Campylobacter , foodborne outbreaks, Listeria, monitoring, parasites, Salmonella, zoonoses

Introduction

Legal basis of European Union‐coordinated zoonoses monitoring

The European Union (EU) system for the monitoring and collection of information on zoonoses is based on Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC 1 , which obliges EU Member States (MS) to collect relevant and, when applicable, comparable data on zoonoses, zoonotic agents, antimicrobial resistance and foodborne outbreaks. In addition, MS shall assess trends and sources of these agents, as well as outbreaks in their territory, submitting an annual report each year by the end of May to the European Commission covering the data collected. The European Commission should subsequently forward these reports to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). EFSA is assigned the tasks of examining these data and publishing the EU Annual Summary Reports. In 2004, the European Commission entrusted EFSA with the task of setting up an electronic reporting system and database for monitoring zoonoses (EFSA Mandate No 2004‐0178, continued by M‐2015‐0231 2 ).

Data collection on human diseases from MS is conducted in accordance with Decision 1082/2013/EU 3 on serious cross‐border threats to health. In October 2013, this Decision replaced Decision 2119/98/EC on setting up a network for the epidemiological surveillance and control of communicable diseases in the EU. The case definitions to be followed when reporting data on infectious diseases to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) are described in Decision 2018/945/EU 4 . ECDC has provided data on zoonotic infections in humans, as well as their analyses, for the EU Summary Reports since 2005. Since 2008, data on human cases have been received via The European Surveillance System (TESSy), maintained by ECDC.

Reporting requirements

According to List A of Annex I of Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC, data on animals, food and feed must be reported on a mandatory basis for the following eight zoonotic agents: Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria monocytogenes, Shiga toxin‐producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Mycobacterium bovis, Brucella, Trichinella and Echinococcus. In addition, and based on the epidemiological situations in the MS, data must be reported on the following agents and zoonoses (List B of Annex I of the Zoonoses Directive): (i) viral zoonoses: calicivirus, hepatitis A virus, influenza virus, rabies, viruses transmitted by arthropods; (ii) bacterial zoonoses: borreliosis and agents thereof, botulism and agents thereof, leptospirosis and agents thereof, psittacosis and agents thereof, tuberculosis due to agents other than M. bovis, vibriosis and agents thereof, yersiniosis and agents thereof; (iii) parasitic zoonoses: anisakiasis and agents thereof, cryptosporidiosis and agents thereof, cysticercosis and agents thereof, toxoplasmosis and agents thereof; and (iv) other zoonoses and zoonotic agents such as Francisella and Sarcocystis. Furthermore, MS provided data on certain other microbiological contaminants in foods: histamine, staphylococcal enterotoxins and Cronobacter sakazakii, for which food safety criteria are set down in the EU legislation.

The general rules on the monitoring of zoonoses and zoonotic agents in animals, food and feed are laid down in Article 4 of Chapter II ‘Monitoring of zoonoses and zoonotic agents’ of the Directive. Specific rules for coordinated monitoring programmes and for food business operators are laid down in Articles 5 and 6 of Chapter II. Specific rules for the monitoring of antimicrobial resistance are laid down in Article 7 of Chapter III ‘Antimicrobial resistance’, whereas rules for epidemiological investigation of foodborne outbreaks can be found in Article 8 of Chapter IV ‘foodborne outbreaks’.

According to Article 9 of Chapter V ‘Exchange of information’ of the Directive, MS shall assess trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and antimicrobial resistance in their territory and each MS shall send to the European Commission every year by the end of May a report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and antimicrobial resistance, covering the data collected under Articles 4, 7 and 8 over the previous year. Reports and any summaries of these shall be made publicly available. The requirements for these MS‐specific reports are described in Parts A–D of Annex IV as regards the monitoring of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and antimicrobial resistance carried out in accordance with Article 4 or 7, and in Part E of Annex IV as regards the monitoring of foodborne outbreaks carried out in accordance with Article 8.

Terms of Reference

In accordance with Article 9 of Directive 2003/99/EC, EFSA shall examine the submitted national reports and data of the EU MS 2020 zoonoses monitoring activities as described above and publish an EU Summary Report on the trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and antimicrobial resistance in the EU.

The 2020 data on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic agents submitted and validated by the MS are published in a separate EU Summary Report.

Data sources and report production

Since 2019, the annual EU Summary Reports on zoonoses, zoonotic agents and foodborne outbreaks have been renamed the ‘EU One Health Zoonoses Summary Report’ (EUOHZ), which is co‐authored by EFSA and ECDC.

The production of the EUOHZ 2020 report was supported by the Consortium ZOE (Zoonoses under a One health perspective in the EU) Work‐package 1 composed by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Rome, Italy), the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie (Padova, Italy), the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (Maisons‐Alfort, France), the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise (Teramo, Italy), the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Lombardia e dell’Emilia Romagna (Brescia, Italy) under the coordination of the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise (Teramo, Italy) (Consortium and Work‐package 3!Grignolleader).

The efforts made by the MS, the reporting non‐MS and the European Commission in the reporting of zoonoses data and in the preparation of this report are gratefully acknowledged.

The MS, other reporting countries, the European Commission, members of EFSA’s Scientific Panels on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ) and Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW), and the relevant European Union Reference Laboratories (EURLs) were consulted while preparing the EUOHZ 2020.

The EUOHZ 2020 focuses on the most relevant information on zoonoses and foodborne outbreaks within the EU in 2020. If substantial changes compared with the previous years were observed, they have been reported.

In order to gather information about the possible impact of the COVID‐19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) pandemic on zoonoses data collection in accordance with Directive 2003/99/EC, a questionnaire was submitted by EFSA and ECDC to the reporting countries. They were asked to evaluate whether in their country, the COVID‐19 pandemic might have had an impact on the monitoring or surveillance and reporting of zoonoses and foodborne outbreaks in 2020. Moreover, countries were asked whether, according to their experience, the collected 2020 data were comparable or not with the previous years’ data. The answers received were used to support the interpretation of the 2020 monitoring and surveillance results (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the survey on the impact of COVID‐19 on the surveillance/reporting of human cases of FWDs (brucellosis, campylobacteriosis, echinococcosis, listeriosis, salmonellosis, STEC infection, trichinellosis, congenital toxoplasmosis and yersiniosis) and comparability of collected data (2019, 2020)

| Country | Impact on surveillance and reporting | Comparability of 2020 and 2019 data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unknown | Variable* | Low | Medium | High | Variable*/Unknown | |

| Austria | x | x | ||||||

| Belgium | x | x | ||||||

| Czechia | X | x | ||||||

| Denmark | x | x | ||||||

| Estonia | x | x | ||||||

| Finland | X | x | ||||||

| France | x | x | ||||||

| Germany | x | x | ||||||

| Greece | x | x | ||||||

| Hungary | x | x | ||||||

| Ireland | x | x | ||||||

| Italy | x | x | ||||||

| Latvia | x | x | ||||||

| Lithuania | X | x | ||||||

| Luxembourg | x | x | ||||||

| Malta | x | x | ||||||

| Netherlands | X | x | ||||||

| Romania | x | x | ||||||

| Slovakia | x | x | ||||||

| Slovenia | x | x | ||||||

| Spain | x | x | ||||||

| Sweden | x | x | ||||||

| Iceland | x | x | ||||||

| Norway | x | x | ||||||

Varies according to the zoonosis.

The 2020 data collection was also affected by the reduction in the number of EU MS from 28 to 27, due to the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) from the EU 5 . On 1 February 2020, the United Kingdom became a third country. The following approaches were used to take account of this reduction in data volume at the EU level, for food, animals, feed and foodborne outbreaks (see below). In descriptive tables, data from the United Kingdom were included in the EU statistics for 2019 and previous years, whereas the 2020 statistical data from the United Kingdom, when available, were assigned to the non‐MS group. With regard to trend analyses of human data, only countries having contributed data for all the years of the considered period were taken into account in the analyses, whereas for trend analyses of the estimated prevalence of Salmonella in poultry populations covered by National Control Programs, any data provided by the reporting EU countries were taken into account in the model. United Kingdom data were only included when available for 2019 and previous years.

Human data collection for 2020

In the EUOHZ for 2020, the analyses of data from infections in humans were prepared by the Food‐ and Waterborne Diseases and Zoonoses (FWD) domain (brucellosis, campylobacteriosis, congenital toxoplasmosis, echinococcosis, listeriosis, salmonellosis, Shiga toxin‐producing E. coli infection, trichinellosis and yersiniosis), the Emerging and Vectorborne Diseases (EVD) domain (Q fever, rabies, tularaemia and West Nile virus (WNV) infection) and the tuberculosis (TB) domain (TB due to Mycobacterium bovis and M. caprae) at ECDC. Please note, as explained above, that the numbers presented in the report may differ from those in national reports due to differences in the case definitions used at EU and at national level, or due to differing dates of data submission and extraction. The latter may also result in some divergence in the case numbers presented in the different ECDC reports.

TESSy is a software platform that has been operational since April 2008 and in which data on 56 diseases and special health issues are collected. Both aggregated and case‐based data were reported to TESSy by Member States and other European countries. Although aggregated data did not include individual case‐based information, both reporting formats were included when possible to calculate the number of cases and country‐specific case notification rates. Human data used in the report were extracted from TESSy as of 15 July 2021 for EVD, as of 28 July 2021 for FWD and as of 30 September 2021 for TB due to M. bovis and M. caprae. The denominators used for calculating notification rates were the human population data from Eurostat’s 1 January 2021 update.

Data on human zoonoses cases were received from 27 MS and from two non‐MS (Iceland and Norway). Switzerland reported its data on human cases directly to EFSA. These aggregated data also include data from Liechtenstein. Since the United Kingdom became a third country on 1 February 2020, human data from the United Kingdom were not collected by ECDC for 2020.

The interpretation of data should consider data quality issues and the differences between MS surveillance systems; comparisons between countries should therefore be undertaken with caution.

Data collection on food, animals, feed and foodborne outbreaks

For the year 2020, 27 MS submitted data and national zoonoses reports on monitoring results in food, animals, feed and foodborne outbreaks. In addition, data and reports were submitted by four non‐MS and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries: Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein. 6 For some food, animal and feed matrices, and for foodborne outbreaks, EFSA received data and reports from the following pre‐accession countries: Albania (no foodborne outbreak data), Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia, as well as from the United Kingdom, which became a third country on 1 February 2020. Food, animal, feed and foodborne outbreak data for 2020 received by EFSA from the United Kingdom in the framework of Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC were excluded from EU 2020 statistics.

Data were submitted electronically to the EFSA zoonoses database, through EFSA’s Data Collection Framework (DCF). MS could also update data from previous years (before 2020).

The deadline for data submission was 31 May 2021. Two data validation procedures were implemented through 11 June 2021 and 15 July 2021, respectively. Validated data on food, animals and feed used in the report were extracted from the EFSA zoonoses database on 2 August 2021.

The draft EUOHZ report was sent to the MS for consultation on 13 October 2021 and comments were collected by 26 October 2021. The utmost effort was made to incorporate comments and data amendments within the available time frame. The report was finalised by 15 November 2021 and published online by EFSA and ECDC on 9 December 2021.

A detailed description of the terms used in the report is available in EFSA’s manuals for reporting on zoonoses (EFSA, 2021a,b,c).

The national zoonoses’ reports submitted in accordance with Directive 2003/99/EC are published on the EFSA website together with the EU One Health Zoonoses Report. They are available online at http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/biological‐hazards‐data/reports.

Data analyses and presentation

Comparability and quality of data

Humans

For data on human infections, please note that the numbers presented in this report may differ from national zoonoses reports due to differences in case definitions used at EU and national level or because of differing dates of data submission and extraction. Results are not directly comparable among the MS.

Food–animals–feed and foodborne outbreaks

For data on food, animals and feed, please note that the numbers presented in this report may differ from national zoonoses reports due to differing dates of data submission and extraction.

The data obtained by the EFSA DCF can vary according to the level of data quality and harmonisation. Therefore, the type of data analyses suggested by EFSA for each zoonosis and matrix (food, animals, feed or foodborne outbreaks) strongly depended on this level of harmonisation and can either be a descriptive summary of submitted data, the following‐up of trends (trend watching) or the (quantitative) analysis of trends. Data analyses were carried out according to (Table 1), as adapted from Boelaert et al. (2016). Food, animals, feed and foodborne outbreak data can be classified into three categories according to the zoonotic agent monitored and the design of the monitoring or surveillance carried out. It follows that the type of data analyses that can be implemented is conditioned by these three distinct categories.

Table 1.

Categorisation of the data used in the EU One Health Zoonoses 2020 Summary Report (adapted from Boelaert et al., 2016)

| Category | Type of analysis | Type/comparability between MS | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I |

Descriptive summaries at the national level and EU level EU trend watching (trend monitoring) Spatial and temporal trend analyses at the EU level |

|

Programmed harmonised monitoring or surveillance Comparable between MS Results at the EU level are interpretable |

Salmonella national control programmes in poultry, bovine tuberculosis, bovine and small ruminant brucellosis, Trichinella in pigs at slaughterhouse |

| II |

Descriptive summaries at national level and EU level EU trend watching (trend monitoring) No EU trend analysis |

|

Monitoring or surveillance not fully harmonised Not fully comparable between MS Caution needed when interpreting results at the EU level |

foodborne outbreak data; Official samplings related to process hygiene criteria for carcases at the slaughterhouse for Salmonella and Campylobacter and to food safety criteria for Campylobacter, L. monocytogenes, Salmonella and STEC in the context of Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005; Rabies monitoring |

| III |

Descriptive summaries at national level and EU level No EU trend watching (trend monitoring) No EU trend analysis |

|

Non‐harmonised monitoring or surveillance data with no (harmonised) reporting requirements Not comparable between MS; extreme caution needed when interpreting results at the EU level |

Campylobacter, Yersinia, Q fever, Francisella tularensis, West Nile virus, Taenia spp., Toxoplasma and other zoonoses |

Rationale of the table of contents

In keeping with the rationale of zoonoses listing in Annex I of Directive 2003/99/EC, for the mandatory reporting of foodborne outbreaks and of the above‐mentioned categorisation of food, animal and feed data (Table 1), the following table of contents has been adopted for the 2020 EUOHZ report.

Zoonoses and zoonotic agents included in compulsory annual monitoring (Directive 2003/99/EC List A)

-

1

Campylobacter

-

2

Salmonella

-

3

Listeria

-

4

Shiga toxin‐producing Escherichia coli

-

5

Tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium caprae

-

6

Brucella

-

7

Trichinella

-

8

Echinococcus

foodborne and waterborne outbreaks (according to Directive 2003/99/EC).

Zoonoses and zoonotic agents monitored according to the epidemiological situation (Directive 2003/99/EC List B)

-

1

Yersinia

-

2

Toxoplasma gondii

-

3

Rabies

-

4

Q fever

-

5

West Nile virus

-

6

Tularaemia

-

7

Other zoonoses and zoonotic agents

Microbiological contaminants subject to food safety criteria (Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005).

Chapter sections

The EU One Health Zoonoses 2020 Summary Report presents a harmonised structure for each chapter, starting with key facts. In addition, there is a section on ‘Monitoring and surveillance’ in the EU for the specific disease or for foodborne outbreaks. A ‘Results’ section summarises the major findings of 2020 as regards trends and sources. A summary table displaying the data for the last 5 years (2016–2020) for human cases and for major animal and food matrices is also presented. Each chapter also contains a ‘Discussion’ section and ends with a list of ‘Related projects and links’ with useful information for the specific disease. For foodborne and waterborne outbreaks, the main findings are presented and discussed in a joint ‘Results and discussion’ section and key messages are summarised in the ‘Conclusions’ section.

For each chapter, overview tables present the data reported by each reporting country. However, for the tables summarising MS‐specific results and providing EU‐level results, unless stated otherwise, data from industry own‐check programmes, hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) sampling, as well as data from suspect sampling, selective sampling and outbreak or clinical investigations are excluded. Moreover, regional data reported by countries without statistics at the national level were also excluded from these summary tables.

Data analyses

Statistical trend analyses in humans were carried out to evaluate the significance of temporal variations in the EU and the specifications of these analyses are explained in each separate chapter. The number of confirmed cases for the EU by month is presented as a trend figure. All countries that consistently reported cases – or reported zero cases over the whole reporting period – were included. The trend figure also shows a centred 12‐month moving average over the last 5 years, illustrating the overall trend by smoothing seasonal and random variations. Moreover, the same trend analysis was carried out separately for each country (MS and non‐MS countries). Analyses of data from humans were carried out for confirmed EU cases only, except for WNV infection, for which total cases (i.e., probable and confirmed cases) were considered.

The notification rates were calculated taking into account the coverage of the human population under surveillance (percentage of national coverage). For countries where surveillance did not apply to the whole population, estimated coverage – if provided – was used to calculate the country‐specific rate. Cases and populations of those countries not providing information on national coverage or reporting incomplete data were excluded from the EU notification rate.

Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) ArcMap 10.5.1 was used to map the data. Choropleth maps with graduated colours over five class scales of values, according to the natural breaks function proposed by the ArcGIS software, were used to map the proportion of positive sample units across the EU and other reporting countries. In the maps included in the present report, EU MS were represented with a blue label, whereas all the non‐EU MS (including EFTA countries: Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein; pre‐accession countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia; and the United Kingdom, which on 1 February 2020 became a third country) were represented with an orange label.

Statistical trend analysis of foodborne outbreaks was performed to evaluate the significance of temporal variations at the single MS level over the 2010–2020 period, as described in the foodborne outbreaks chapter.

All undisplayed summary tables and figures used to produce this report are published as supporting information and are available as downloadable files from the EFSA knowledge junction at the Zenodo general‐purpose open‐access repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5682809. All validated country‐specific data on food, animals, feed and foodborne outbreaks are also available at the above‐mentioned URL.

Summary of human zoonoses data for 2020

The numbers of confirmed human cases of the zoonoses presented in this report are summarised in Figure 1. In 2020, campylobacteriosis was the most commonly reported zoonosis, as it has been since 2005. It represented more than 60% of all the reported cases in 2020. It was followed by other bacterial diseases, with salmonellosis, yersiniosis and STEC infections being the most frequently reported. The severity of the diseases was descriptively analysed based on hospitalisations and the outcomes of reported cases (Table 2). Based on severity data, listeriosis and West Nile virus infection were the two most severe diseases with the highest case fatality and hospitalisation rates. Almost all confirmed cases with available hospitalisation data for these two diseases were hospitalised. About one out of every seven, and one out of every eight, confirmed listeriosis and WNV cases with known data were fatal.

Figure 1.

- Note: The total number of confirmed cases is indicated in parentheses at the end of each bar. (a): Regarding West Nile virus infection, the total number of cases was used (includes probable and confirmed cases).

Table 2.

Reported hospitalisations and case fatalities due to zoonoses in confirmed human cases in the EU, 2020

| Disease | Number of confirmed human cases | Hospitalisation | Deaths | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status available (N) | Status available (%) | Number of reporting MS b | Reported hospitalised cases | Proportion hospitalised (%) | Outcome available (N) | Outcome available (%) | Number of reporting MS b | Reported deaths | Case fatality (%) | ||

| Campylobacteriosis | 120,946 | 41,037 | 33.9 | 14 | 8,605 | 21.0 | 83,744 | 69.2 | 15 | 45 | 0.05 |

| Salmonellosis | 52,702 | 20,562 | 39.0 | 13 | 6,149 | 29.9 | 30,355 | 57.6 | 15 | 57 | 0.19 |

| Yersiniosis | 5,668 | 1,214 | 21.4 | 12 | 353 | 29.1 | 3,072 | 54.2 | 13 | 2 | 0.07 |

| STEC infections | 4,446 | 1,593 | 35.8 | 16 | 652 | 40.9 | 3,094 | 69.6 | 19 | 13 | 0.42 |

| Listeriosis | 1,876 | 803 | 42.8 | 18 | 780 | 97.1 | 1,283 | 68.4 | 18 | 167 | 13.0 |

| Tularaemia | 641 | 123 | 19.2 | 9 | 64 | 52.0 | 200 | 31.2 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Echinococcosis | 488 | 73 | 15.0 | 12 | 44 | 60.3 | 204 | 41.8 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Q fever | 523 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 235 | 44.9 | 14 | 5 | 2.1 |

| West Nile virus infection a | 322 | 239 | 74.2 | 8 | 219 | 91.6 | 322 | 100 | 8 | 39 | 12.1 |

| Brucellosis | 128 | 56 | 43.8 | 8 | 36 | 64.3 | 55 | 43.0 | 9 | 2 | 3.6 |

| Trichinellosis | 117 | 22 | 18.8 | 5 | 16 | 72.7 | 24 | 20.5 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Rabies | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

MS: Member State(s); NA: Not applicable, as information is not collected for this disease.

Locally acquired infections – for West Nile virus infection, the total number of cases was used (includes probable and confirmed cases).

Not all countries observed cases for all diseases.

Comparison of human zoonoses data for 2019–2020

According to an MS survey conducted to interpret the possible impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on surveillance activities and the reporting of FWD data (Table 3), in humans, for 10 out of 22 MS that provided answers to the survey, the pandemic impacted their surveillance/monitoring systems, whereas for seven MS, there were no reported effects due to the pandemic. The comparability of FWD data for 2020 and 2019 was considered low–medium for 15 MS, whereas for only three MS were the human data reported over the last 2 years considered comparable.

The comparison of data from 2020 and 2019 was influenced by the pandemic and by the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU. In order to estimate the impact of both of these events on reported data, the absolute and relative difference between the number of cases and the notification rate reported in the EU for 2020 compared with 2019 for each disease was estimated (Table 4). For all zoonoses except trichinellosis and yersiniosis, there was a reduction in the notification rates (*100,000 population) in 2020 as compared with 2019. The relative fall in notification rates in the EU varied from −52.6% for brucellosis to −7.1% for listeriosis. For trichinellosis and yersiniosis, there was an increase of 39.1% and 6.0%, respectively, in the 2020 EU notification rate as compared with 2019. For each disease, the 2020/2019 relative difference in EU notification rates was also calculated based on EU 27 data only (i.e. excluding data reported by the United Kingdom for 2019) (Table 4) in order to provide evidence of the effect of the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU.

Table 4.

2020/2019 absolute difference in the number of confirmed human cases by zoonosis and absolute and relative (%) difference in notification rates per 100,000 population for zoonoses reported in the EU, 2020

| Zoonosis | EU level a | Cases (N) | Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2020–2019 difference | 2020 | 2020–2019 difference | |||

| Absolute difference (%) | Relative difference (%) | |||||

| Campylobacteriosis | EU | 120,946 | –99,693 | 40.3 | –20.3 | –33.4 |

| EU‐27 | –40,975 | –13.7 | –25.4 | |||

| Salmonellosis | EU | 52,702 | –35,206 | 13.7 | –5.8 | –29.7 |

| EU‐27 | –25,488 | –6.7 | –32.8 | |||

| Yersiniosis | EU | 5,668 | –1,299 | 1.8 | 0.10 | 6.0 |

| EU‐27 | –1,136 | –0.27 | –13.4 | |||

| STEC infections | EU | 4,446 | –3,355 | 1.5 | –0.43 | –22.4 |

| EU‐27 | –1,768 | –0.33 | –18.2 | |||

| Listeriosis | EU | 1,876 | –745 | 0.42 | –0.03 | –7.1 |

| EU‐27 | –591 | –0.07 | –14.2 | |||

| Tularaemia | EU | 641 | –639 | 0.15 | –0.11 | –42.5 |

| EU‐27 | –639 | –0.15 | –50.0 | |||

| Q fever | EU | 523 | –428 | 0.12 | –0.07 | –36.7 |

| EU‐27 | –419 | –0.10 | –44.6 | |||

| Echinococcosis | EU | 488 | –278 | 0.14 | –0.03 | –16.2 |

| EU‐27 | –275 | –0.06 | –28.4 | |||

| West Nile virus b | EU | 322 | –68 | 0.07 | –0.01 | –12.9 |

| EU‐27 | –68 | –0.02 | –24.4 | |||

| Brucellosis | EU | 128 | –182 | 0.03 | –0.03 | –52.6 |

| EU‐27 | –158 | –0.04 | –55.3 | |||

| Trichinellosis | EU | 117 | 20 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 39.1 |

| EU‐27 | 20 | < 0.01 | 20.4 | |||

| Tuberculosis | EU | 88 | 64 | 0.02 | –0.01 | –32.0 |

| EU‐27 | 29 | –0.01 | –24.9 | |||

In 2019, data from the United Kingdom were collected because the UK was an EU MS, but since 1 February 2020, it has become a third country. To calculate the 2020/2019 difference, data from the United Kingdom for 2019 were included in this ‘EU’ calculation, whereas human data from the United Kingdom were not collected by ECDC for 2020 (‘EU‐27’).

For West Nile virus infection, the total number of cases was used (includes probable and confirmed cases).

The relative difference in human notification rates at the EU‐27 level allows for a more precise assessment of the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on zoonoses in the EU (Table 4). A fall in notification rates (≥ 30% relative decrease) was reported for brucellosis, tularaemia, Q fever and salmonellosis. For echinococcosis, campylobacteriosis, WNV infections, tuberculosis, STEC infections, listeriosis and yersiniosis, the drop was less relevant. For trichinellosis, an increase in the relative difference between the 2020 and 2019 EU (27) notification rates was observed.

According to the feedback provided by MS along with the survey and the evidence deriving from the scientific literature (Haldane et al., 2021; Müller et al., 2021; Ullrich et al., 2021), the COVID‐19 pandemic might have caused a drop in reported human cases and notification rates for almost all zoonotic diseases. Various factors, in fact, might have had an effect: national health care resilience (health workforce, laboratory and diagnostic capability, access to hospitals and medical assistance), the shutdown of domestic and international travel, restrictions on sporting and recreational/social events, the closing of restaurants and catering facilities (i.e. schools, workplaces), quarantine, lockdown and other non‐pharmaceutical mitigation measures (face masking, hand washing/sanitisation, physical distancing, restricted movement and social gatherings).

Instead, looking at the relative difference in notification rates in the EU (2019) and EU‐27 (2020), the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU seems to have had little impact on salmonellosis and tuberculosis. For campylobacteriosis and STEC infection, the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU seems to have had a positive impact in terms of reduction of the EU notification rate, probably related to a recurring high number of cases reported by the United Kingdom relative to population size. In contrast, for the remaining diseases, the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU seems to have had a negative impact because an increase in the EU notification rate was noted, likely due to the low number of cases reported by the United Kingdom relative to population size.

Zoonoses included in compulsory annual monitoring (Directive 2003/99 List A)

1. Campylobacter

Tables and figures that are not presented in this chapter are published as supporting information to this report and are available as downloadable files from the EFSA Knowledge Junction on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5682809. Summary statistics of human surveillance data with downloadable files are retrievable using ECDC’s Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases at http://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx

1.1. Key facts

-

•

Campylobacteriosis is the most commonly reported foodborne gastrointestinal infection in humans in the EU and has been so since 2005.

-

•

In 2020, Campylobacter reporting recorded the lowest number of human cases since campylobacteriosis surveillance began in 2007, owing to the impacts of the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU and the COVID‐19 pandemic.

-

•

In 2020, the number of confirmed cases of human campylobacteriosis totalled 120,946, corresponding to an EU notification rate of 40.3 per 100,000 population. This is a decrease of 33.4% and 25.4% compared with the rate in 2019 (60.6 and 54.0 per 100,000 population) with and without the 2019 data from the United Kingdom, respectively.

-

•

A decrease in cases was observed in 2020, probably due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. However, the overall campylobacteriosis trend in 2016–2020 showed no statistically significant increase or decrease.

-

•

In most of the cases (98.5%), where the origin was known, the infection was acquired in the EU.

-

•

In 2020, Campylobacter was the fourth most frequent cause of foodborne outbreaks reported by 17 MS at EU level. In total, 317 outbreaks caused by Campylobacter were reported to EFSA, including 1,319 cases of illness, 112 hospitalisations and no deaths. Eleven outbreaks were reported with strong evidence and 306 with weak evidence. The most common food vehicles for the strong‐evidence campylobacteriosis foodborne outbreaks were ‘broiler meat’ and ‘raw milk’, as in previous years.

-

•

Twenty‐one MS reported data in the context of the Campylobacter process hygiene criterion, set out in Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005. In particular, 12 MS reported official controls from 6,384 neck skin samples. Of the results reported, 38.7% were Campylobacter‐positive, and 17.8% exceeded the limit of 1,000 colony forming unit (CFU)/g. Seventeen MS reported monitoring data based on sampling results collected from food business operators. A total of 46,259 test results from neck skin samples were reported. Of the results reported, 31.3% were Campylobacter‐positive, whereas 17.6% exceeded the limit of 1,000 CFU/g and this percentage was comparable with the results from official controls. Eight MS reported results from both samplers and showed 42.1% and 40.1% Campylobacter‐positive samples from official and food business operators, respectively. Overall for these eight MS, the number of samples exceeding the limit was significantly higher in official samples (16.6%) than those based on own‐checks (8.9%).

-

•

In 2020, 3,202 ‘ready‐to‐eat’ and 13,240 ‘non ready‐to‐eat’ results from food sampling unit were reported by seven and 16 MS, respectively. In the ‘ready‐to‐eat’ category, four Campylobacter‐positive sampling units were detected: two from ‘raw milk’, one from ‘meat products’ and one from ‘fruit, vegetables and juices’. In the ‘non ready‐to‐eat’ food category, 2,684 (20.3%) Campylobacter‐positive sampling unit was reported. The food category with the highest level of contamination was ‘meat and meat products’ with 25.2% positive units. Overall, Campylobacter was isolated from all fresh meat categories, with meat from broilers and turkeys showing the highest percentage of Campylobacter‐positive samples, 30.5% and 21.5%, respectively.

-

•

In 2020, Campylobacter spp. was detected by 17 MS and four non‐MS in more than 50 different animal categories. However, the vast majority of units tested (N = 13,625) were collected from broilers, where the observed proportion of positives was 24.5%. Although fewer samples were reported by a small number of countries for turkeys and pigs alone, these categories had the highest proportion of positives, 62.1% and 58.5%, respectively.

1.2. Surveillance and monitoring of Campylobacter in the EU

1.2.1. Humans

Notification of campylobacteriosis is mandatory in 22 EU MS, as well as in Iceland, Norway and Switzerland. In five MS, notification is based on a voluntary system (Belgium, France, Greece, Italy and the Netherlands). Greece started to report campylobacteriosis data in 2018. The surveillance systems for campylobacteriosis cover the whole population in all MS except for the four countries of France, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. The estimated coverage of the surveillance system is 20% in France and 58% in the Netherlands. These estimated proportions of population coverage were used in the calculation of notification rates for these two MS. No estimates of population coverage in Italy and Spain were provided, so notification rates were not calculated for these two MS. The data for Switzerland include data from Liechtenstein and were reported to EFSA.

All countries reported case‐based data except Belgium, Bulgaria and Greece, which reported aggregated data. Both reporting formats were included in order to calculate the annual numbers of cases and the notification rates.

On 1 February 2020, the United Kingdom became a third country, whereas before it was an EU MS. Human data from the United Kingdom were not collected by the ECDC for 2020.

The diagnosis of human infection is generally based on cultures from human stool samples, using both culture and non‐culture methods (polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) for confirmation. Biochemical tests or molecular methods are used to determine the species of isolate reported to the National Public Health Reference Laboratories (NPHRL).

Almost all countries have noted a drop in the number of reported campylobacteriosis cases compared with previous years. The COVID‐19 pandemic had an impact on both surveillance (including diagnosis) and reporting. Conversely, France and Luxembourg observed an increase in the number of reported cases compared with 2019. France reported a higher number of cases in the summer when control measures against COVID‐19 were probably less severe since there was no lockdown during that period. In March 2020, Luxembourg introduced an electronic laboratory notification system and, despite the pandemic, campylobacteriosis notification has increased as expected.

1.2.2. Food and animals

Campylobacter is monitored along the food chain during the primary production stage (farm animals), during harvest/slaughter and processing and at the retail stage.

Campylobacter data in the context of Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005

A regulatory limit (microbiological process hygiene criterion (PHC)) of 1,000 CFU/g of Campylobacter on the neck skins of chilled broiler carcases was set by Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 7 (point 2.1.9 of Chapter 2 of Annex I). This limit applies to a set of 50 pooled samples from 10 consecutive sampling sessions. As of 2020, a maximum number of 15 samples with values exceeding this limit are considered as acceptable. This criterion aims to stimulate action to lower Campylobacter counts on broiler carcases and to reduce the number of human campylobacteriosis cases caused by the consumption or handling of contaminated chicken/broiler meat. The PHC has been in force since 1 January 2018. Food business operators (FBOp) are required to use the criterion to validate and verify their food safety management procedures based on HACCP principles and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). FBOp must carry out corrective action if the criterion target is exceeded. Official samplings taken by the Competent Authorities (CA) serve to audit FBOp activities and to ensure that FBOp comply with regulatory requirements. On 14 December 2019, the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627 8 was introduced to harmonise sampling procedures for official controls. The results obtained from official controls, whose reporting is mandatory, allow for improved trend watching and trend analyses (Table 1). This legislation requires the CA to verify whether the FBOp is correctly implementing and checking the PHC on broiler carcases by choosing one of two approaches: implementing ad hoc official sampling 9 or collecting all the information from the samples taken by the FBOp relating to the total number of samples tested in order to establish the number of Campylobacter‐positive samples with a bacterial load of over 1,000 CFU/g in accordance with Article 5 of Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005.

Other monitoring data for food and animals

Campylobacter monitoring data at slaughter obtained from poultry caeca as part of annual antimicrobial resistance monitoring are collected using a randomised sampling scheme in order to provide data that are more harmonised.

Other Campylobacter monitoring data from food and animals submitted to EFSA in compliance with Chapter II ‘Monitoring of zoonoses and zoonotic agents’ of the Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC 10 are collected without a harmonised procedure. These data allow descriptive summaries at EU level, but they do not support EU‐level trend analyses and trend watching (Table 1).

In 2020, general data on food and animals reported to EFSA by MS and non‐MS were mainly from official sampling, industry sampling HACCP and own‐checks, as part of national monitoring and surveillance and/or organised surveys. In addition, for animal data, other reported samples were obtained from clinical investigations by private veterinarians and industry (e.g. artificial insemination centres).

The occurrence of Campylobacter reported in the main food categories for the year 2020 and for the 4‐year period of 2016–2019 was descriptively summarised, making a distinction between RTE and non‐RTE food. Data sets were extracted using the strategy of ‘objective sampling’, meaning that the reporting MS collected the samples as part of a planned strategy based on the selection of random samples that are statistically representative of the population to be analysed.

On 1 February 2020, the United Kingdom became a third country, whereas before it was an EU MS. Food, animal and feed data from the United Kingdom were collected by EFSA for 2020 as part of Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC.

The detection of Campylobacter in food and animals is generally based on culture and confirmation. Species identification is carried out using biochemical and molecular methods (PCR based), as well as matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionisation time‐of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI‐TOF MS).

1.2.3. foodborne outbreaks of campylobacteriosis

The reporting of foodborne campylobacteriosis disease outbreaks in humans is mandatory, according to Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC.

1.3. Data analyses

Comparison between Competent Authority and Food Business Operator sampling results

A comparison was made of Campylobacter results exceeding 1,000 CFU/g from the neck skins of broiler carcases after chilling obtained by the CA and FBOp as part of the Campylobacter PHC in compliance with Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005. The significance of any differences was verified by the one‐tailed Fisher’s exact probability test, in cases where the expected values of any of the cells in a contingency table were below 5; otherwise, the one‐tailed z test was used. The official control sampling results by the CA and the own‐check results by the FBOp were expressed as prevalence ratios with an exact binomial confidence interval of 95%. A p‐value of < 0.10 (Clayton and Hills, 2013) was considered as significant in order to highlight every possible indication of differences between the data collected by the FBOp and the CA. R software (www.r‐project.org, version 4.0.5) was used to conduct the above analyses.

1.4. Results

1.4.1. Overview of key statistics, EU, 2016–2020

Table 5 summarises EU statistics on human campylobacteriosis, and on the occurrence and prevalence of Campylobacter in food and animals, respectively, during 2016–2020. In 2020, a substantial decrease was observed in notified human cases, caused in part by the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU. The food data of interest in this report were classified into two major categories: ‘meat and meat products’ and ‘milk and milk products’ and aggregated by year to obtain an annual overview of the volume of data submitted. The number of sampling units reported for the years 2019 and 2020 for ‘meat and meat products’ increased sharply compared with the previous years, which is likely the result of the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627 establishing compulsory reporting of Campylobacter PHC monitoring data (see above).

Table 5.

Summary of Campylobacter statistics related to humans and major food categories, EU, 2016–2020

| 2020 | 2019 a | 2018 a | 2017 a | 2016 a | Data source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | ||||||

| Total number of confirmed cases | 120,946 | 220,639 | 246,570 | 246,194 | 246,980 | ECDC |

| Total number of confirmed cases/100,000 population (notification rates) | 40.3 | 60.6 | 66.0 | 68.2 | 69.6 | ECDC |

| Number of reporting MS | 27 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 27 | ECDC |

| Infection acquired in the EU | 70,769 | 109,937 | 116,246 | 122,280 | 122,819 | ECDC |

| Infection acquired outside the EU | 1,586 | 6,514 | 7,685 | 6,583 | 5,966 | ECDC |

| Unknown travel status or unknown country of infection | 48,591 | 104,188 | 122,639 | 117,331 | 118,195 | ECDC |

| Number of foodborne outbreak‐related cases | 1,319 | 1,254 | 2,365 | 3,608 | 4,645 | EFSA |

| Total number of foodborne outbreaks | 317 | 319 | 537 | 395 | 474 | EFSA |

| Food b | ||||||

| Meat and meat products c | ||||||

| Number of sampling units | 65,895 | 57,027 | 26,514 | 21,521 | 18,253 | EFSA |

| Number of reporting MS | 25 | 25 | 26 | 22 | 21 | EFSA |

| Milk and milk products d | ||||||

| Number of sampling units | 2,145 | 2,749 | 3,227 | 2,317 | 2,062 | EFSA |

| Number of reporting MS | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 11 | EFSA |

ECDC: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; EFSA: European Food Safety Authority.

When UK data were collected for the period 2016–2019, the UK was an EU MS, but on 1 February 2020, it became a third country. Data from the UK are taken into account for the years 2016–2019, but are not considered in the EU overview for 2020.

Summary statistics referring to MS were obtained by totalling all sampling units (single, batch, slaughter batch), sampling stages (farm, packing centre, processing plant, cutting plant, slaughterhouse, catering, hospital or medical care facility, restaurant or cafe or pub or bar or hotel or catering service, retail, wholesale, border control posts, school or kindergarten, unspecified), sampling strategies (census, convenience sampling, selective sampling, objective sampling and unspecified) and samplers (official sampling, official and industry sampling, private sampling, unspecified).

‘Meat and meat products’ refer to carcases and fresh meat/ready‐to‐eat (RTE), cooked and fermented products.

‘Milk and milk products’ refer to raw and pasteurised milk and all dairy products including cheeses.

A more detailed description of foodborne outbreak statistics can be found in the chapter on foodborne outbreaks.

1.4.2. Human campylobacteriosis

In 2020, 120,946 confirmed cases of human campylobacteriosis were reported by the 27 EU MS, corresponding to an EU notification rate of 40.3 cases per 100,000 population (Table 6). This is a decrease of 33.4% and 25.4% compared with the rate in 2019 (60.6 and 54.0 per 100,000 population) with and without data from the United Kingdom, respectively. The highest country‐specific notification rates in 2020 were observed in Czechia (163.8 cases per 100,000), Luxembourg (116.4), Slovakia (90.2) and Denmark (64.3). The lowest rates in 2020 were observed in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Latvia and Portugal (≤ 7.7 per 100,000) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Reported human cases of campylobacteriosis and notification rates per 100,000 population in EU‐MS and non‐MS countries, by country and by year, 2016–2020

| Country | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National coverage a | Data format a | Confirmed cases and rates | Confirmed cases and rates | Confirmed cases and rates | Confirmed cases and rates | Confirmed cases and rates | ||||||

| Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | Cases | Rate | |||

| Austria | Y | C | 5,406 | 60.7 | 6,572 | 74.2 | 7,999 | 90.7 | 7,204 | 82.1 | 7,083 | 81.4 |

| Belgium | Y | A | 5,595 | 48.6 | 7,337 | 64.0 | 8,086 | 70.9 | 8,649 | 76.2 | 10,055 | 88.9 |

| Bulgaria | Y | A | 127 | 1.8 | 229 | 3.3 | 191 | 2.7 | 195 | 2.7 | 202 | 2.8 |

| Croatia | Y | C | 1,054 | 26.0 | 1,722 | 42.2 | 1,965 | 47.9 | 1,686 | 40.6 | 1,524 | 36.4 |

| Cyprus | Y | C | 18 | 2.0 | 21 | 2.4 | 26 | 3.0 | 20 | 2.3 | 21 | 2.5 |

| Czechia | Y | C | 17,517 | 163.8 | 22,894 | 215.0 | 22,895 | 215.8 | 24,326 | 230.0 | 24,084 | 228.2 |

| Denmark | Y | C | 3,742 | 64.3 | 5,402 | 93.0 | 4,559 | 78.9 | 4,255 | 74.0 | 4,712 | 82.6 |

| Estonia | Y | C | 265 | 19.9 | 347 | 26.2 | 411 | 31.2 | 285 | 21.7 | 298 | 22.6 |

| Finland | Y | C | 2,074 | 37.5 | 4,382 | 79.4 | 5,099 | 92.5 | 4,289 | 77.9 | 4,637 | 84.5 |

| France b | N | C | 7,920 | 58.8 | 7,712 | 57.4 | 7,491 | 55.9 | 6,579 | 49.2 | 6,698 | 50.3 |

| Germany | Y | C | 46,379 | 55.8 | 61,277 | 73.8 | 67,585 | 81.6 | 69,251 | 83.9 | 73,736 | 89.7 |

| Greece | Y | A | 218 | 2.0 | 366 | 3.4 | 357 | 3.3 | – | – | – | – |

| Hungary | Y | C | 4,461 | 45.7 | 6,400 | 65.5 | 7,117 | 72.8 | 7,807 | 79.7 | 8,556 | 87.0 |

| Ireland | Y | C | 2,419 | 48.7 | 2,776 | 56.6 | 3,044 | 63.0 | 2,779 | 58.1 | 2,511 | 53.1 |

| Italy c | N | C | 1,418 | – | 1,633 | – | 1,356 | – | 1,060 | – | 1,057 | – |

| Latvia | Y | C | 104 | 5.5 | 133 | 6.9 | 87 | 4.5 | 59 | 3.0 | 90 | 4.6 |

| Lithuania | Y | C | 1,183 | 42.3 | 1,221 | 43.7 | 919 | 32.7 | 990 | 34.8 | 1,225 | 42.4 |

| Luxembourg | Y | C | 729 | 116.4 | 271 | 44.1 | 625 | 103.8 | 613 | 103.8 | 518 | 89.9 |

| Malta | Y | C | 206 | 40.0 | 278 | 56.3 | 333 | 70.0 | 231 | 50.2 | 212 | 47.1 |

| Netherlands d | N | C | 2,549 | 25.2 | 3,415 | 34.1 | 3,091 | 34.6 | 2,890 | 32.5 | 3,383 | 38.3 |

| Poland | Y | C | 414 | 1.1 | 715 | 1.9 | 719 | 1.9 | 874 | 2.3 | 773 | 2.0 |

| Portugal | Y | C | 790 | 7.7 | 887 | 8.6 | 610 | 5.9 | 596 | 5.8 | 359 | 3.5 |

| Romania | Y | C | 300 | 1.6 | 805 | 4.1 | 573 | 2.9 | 467 | 2.4 | 517 | 2.6 |

| Slovakia | Y | C | 4,921 | 90.2 | 7,690 | 141.1 | 8,339 | 153.2 | 6,946 | 127.8 | 7,623 | 140.5 |

| Slovenia | Y | C | 811 | 38.7 | 1,085 | 52.1 | 1,305 | 63.1 | 1,408 | 68.2 | 1,642 | 79.5 |

| Spain(c)(e) | N | C | 6,891 | – | 9,658 | – | 18,410 | – | 18,860 | – | 15,542 | – |

| Sweden | Y | C | 3,435 | 33.3 | 6,693 | 65.4 | 8,132 | 80.4 | 10,608 | 106.1 | 11,021 | 111.9 |

| EU Total 27 | – | – | 120,946 | 40.3 | 161,921 | 54.0 | 181,324 | 58.1 | 182,927 | 61.0 | 188,079 | 64.4 |

| United Kingdom | – | – | – | – | 58,718 | 88.1 | 65,246 | 98.4 | 63,267 | 96.1 | 58,901 | 90.1 |

| EU Total f | – | – | 120,946 | 40.3 | 220,639 | 60.6 | 246,570 | 66.0 | 246,194 | 68.2 | 246,980 | 69.6 |

| Iceland | Y | C | 95 | 26.1 | 136 | 38.1 | 145 | 41.6 | 119 | 35.2 | 128 | 38.5 |

| Norway | Y | C | 2,422 | 45.1 | 4,154 | 78.0 | 3,668 | 69.3 | 3,883 | 73.8 | 2,317 | 44.5 |

| Switzerland g | Y | C | 6,200 | 71.7 | 7,223 | 84.2 | 7,675 | 90.1 | 7,221 | 85.4 | 7,984 | 95.4 |

–: Data not reported.

Y: yes; N: no; A: aggregated data; C: case‐based data.

Sentinel surveillance; notification rates calculated with an estimated coverage of 20%.

Sentinel surveillance; no information on the estimated coverage. So the notification rate cannot be estimated.

Sentinel surveillance; notification rates calculated with an estimated coverage of 52% in 2016–2018, 58% in 2019–2020.

Data not complete in 2020, rate not estimated.

Cases reported by the United Kingdom for the period 2016–2019 were also considered for this estimation (EU‐28). When UK data were collected for the period 2016–2019, the UK was an EU MS, but on 1 February 2020, it became a third country.

Switzerland provided data directly to EFSA. Human data for Switzerland include data from Liechtenstein.

For most (98.5%) of the reported campylobacteriosis cases of known origin, the infection was contracted in the EU (Table 5) as compared to 94.4% in 2019. Nineteen countries reported data on the importation of cases. The proportion of domestic cases with known data was over 95% in all countries except in the Nordic countries, which reported the highest proportion of travel‐associated cases: Finland (49.2%), Sweden (25.6%), Denmark (10.3%), Iceland (16.5%) and Norway (14.8%). A decrease of travel‐associated cases was observed in 2020 (3.7%) compared to 2019 (10.8%). Of the 2,676 travel‐associated cases among MS with a known country of infection, 1,090 cases (40.7%) were linked to travel within the EU, with most of the infections being acquired in Spain, Croatia, France and Austria (23.7%, 9.7%, 8.0% and 7.2%, respectively). Thailand, India, Morocco and Indonesia were the most frequently reported probable countries of infection outside the EU (29.5%, 8.3%, 7.8% and 6.1%, respectively). Campylobacteriosis cases were reported in all age groups, with the highest proportion of reported cases belonging to the youngest age group from 0 to 4 years (18,920 cases: 15.6%).

Between 2011 and 2020, the number of confirmed campylobacteriosis cases reported in the EU showed a clear seasonal trend, peaking in the summer months. Annual winter peaks were also observed in January from 2011 to 2020, although peak numbers were lower than those observed during the summer. A fall in cases was observed in 2020, particularly in March and April, probably due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. However, the overall campylobacteriosis trend in 2016–2020 showed no statistically significant increase or decrease (Figure 2). Finland, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden reported significantly decreasing trends (p < 0.01) during the period 2016–2020. Latvia and Italy reported significantly increasing trends over the same period.

Figure 2.

- Source: Austria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden.

Information on hospitalisation status was provided for 33.9% of all campylobacteriosis cases by 14 MS in 2020. Of the cases with known hospitalisation status, 8,605 (21%) were hospitalised. The highest hospitalisation rates were reported in Latvia (93.3%), Poland (76.6%) and Cyprus (66.7%), where most of the reported cases were hospitalised. Outcomes were reported for 69.2% of all cases by 15 MS. Forty‐five deaths from campylobacteriosis were reported in 2020, resulting in an EU case fatality rate of 0.05%. The average percentage of fatal outcomes observed has remained unchanged over the past 5 years. Information on gender was provided for 120,514 confirmed cases in the EU: 54.1% were male and 45.9% female.

Campylobacter species information was provided by 20 MS for 64.7% of confirmed cases reported in the EU, an increase over 2019 (55.2%). Of these cases, 88.1% concerned Campylobacter jejuni, 10.6% Campylobacter coli, 0.16% Campylobacter fetus, 0.11% Campylobacter upsaliensis and 0.09% Campylobacter lari. Other Campylobacter species accounted for 0.94% of cases, but most of those cases were reported at national level as ‘C. jejuni /C. coli/C. lari not differentiated’. No information on species was provided by Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Greece, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Sweden.

Human campylobacteriosis cases and cases associated with foodborne outbreaks

The reporting of foodborne campylobacteriosis outbreaks in humans is mandatory, in compliance with Zoonoses Directive 2003/99/EC, with data collected by reporting countries and submitted to EFSA. In TESSy, the cases reported are classified according to the EU case definition. All these cases visited a doctor and either confirmed by a laboratory test (confirmed cases) or not confirmed (probable case with classification based on the clinical symptoms and epidemiological link). Cases that never visited a doctor are not reported to TESSy. Moreover, there may be other missing probable cases in TESSy, as these data are not analysed or published and there is no incentive for reporting such cases. Information on which cases are linked to an outbreak and which are not is also not systematically collected. In practice, the cases reported to TESSy are considered mostly as sporadic cases In foodborne outbreaks, human cases are the people involved in the outbreak as defined by the investigators (case definition), and cases must be linked, or probably linked, to the same food source (Directive 2003/99/EC). This can include both people who are ill (whether or not confirmed microbiologically) and people with confirmed asymptomatic infections (EFSA, 2014).

Overall in 2020, 98.5% of the reported human campylobacteriosis cases, who acquired in the EU (70,769), were domestic infections (acquired within the home country) (Table 5). In 2020, Campylobacter was the fourth most frequently reported causative agent for foodborne outbreaks within the EU, with 317 outbreaks reported by 17 MS at EU level, 1,319 cases of illness, 112 hospitalisations (8.5%) and no deaths. If we compare the number of foodborne outbreak cases (1,319) reported to EFSA, with the number of cases of human campylobacteriosis acquired in the EU (70,769) including the proportion with unknown travel data (0.978 × 48,591), reported to the ECDC, it could be suggested that overall, within the EU, only 1.1% of human campylobacteriosis cases were reported through foodborne outbreak investigations in 2020.

C. jejuni and C. coli were identified in 142 and six outbreaks, respectively. However, most Campylobacter foodborne outbreaks were reported without species determination (169 outbreaks: 53.3%). Eleven campylobacteriosis outbreaks were reported with strong evidence and 306 with weak evidence. Of the former outbreaks, four were caused by ‘broiler meat’ and four by ‘milk’ (three by ‘raw milk’ and one by ‘pasteurised milk’). During the period 2011–2019, these were also the food vehicles causing most strong‐evidence foodborne campylobacteriosis outbreaks. Further details and statistics on campylobacteriosis outbreaks for 2020 can be found in the foodborne outbreaks chapter.

1.4.3. Campylobacter in food

Campylobacter data in the context of Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005

Table 7 shows Campylobacter PHC monitoring data, with the test results obtained using a culture‐based enumeration method (ISO 10272‐2), from the neck skins of chilled broiler carcases sampled at slaughterhouses within the EU. Twelve MS reported ad hoc official sampling results, 17 MS reported monitoring results from FBOp and eight MS (Belgium, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Romania and Spain) reported data from both samplers. In total, 52,643 neck skin units were tested, of which 32% were Campylobacter positive (N = 16,869).

Table 7.

Comparison of proportions (%) of Campylobacter‐positive samples and samples exceeding the Campylobacter PHC limit according to Regulation (EC) No. 2073/2005, by sampler, from reporting MS, EU, 2020

| Country | Competent Authority (CA) | Food business operator (FBOp) | p‐value b , c | Interpretation c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N samples Tested | N (%) samples positive | N (%) samples above 1,000 CFU/g | CI95 samples above 1,000 CFU/g | N samples Tested | N (%) samples positive | N (%) samples above 1,000 CFU/g | CI95 samples above 1,000 CFU/g | |||

| Austria | – | – | – | – | 795 | 248 (31.2) | 38 (4.8) | [3.4; 6.5] | – | – |

| Belgium | 643 | 238 (37.0) | 95 (14.8) | [12.1; 17.8] | 1,883 | 202 (10.7) | 202 (10.7) | [9.4; 12.2] | < 0.01 | CA > FBOp |

| Bulgaria | 650 | 160 (24.6) | 17 (2.6) | [1.5; 4.2] | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Croatia | 1,058 | 324 (30.6) | 319 (30.2) | [27.4; 33.0] | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cyprus | 230 | 162 (70.4) | 87 (37.8) | [31.5; 44.4] | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Czechia | – | – | – | – | 3,738 | 2,267 (60.7) | 1,255 (33.6) | [ 32.1; 35.1] | – | – |

| Denmark | – | – | – | – | 985 | 186 (18.9) | 69 (7.0) | [5.5; 8.8] | – | – |

| Estonia | 12 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | [0; 26.5] a | 260 | 10 (3.9) | 5 (1.9) | [0.63; 4.4] | NS | |

| Finland | – | – | – | – | 595 | 1 (0.17) | 1 (0.17) | [0; 0.93] | – | – |

| France | – | – | – | – | 15,481 | 4,405 (28.5) | 4,405 (28.5) | [27.7; 29.2] | – | – |

| Germany | – | – | – | – | 5,556 | 419 (7.5) | 419 (7.5) | [6.9; 8.3] | – | – |

| Greece | 155 | 35 (22.6) | 25 (16.1) | [10.7; 22.9] | 975 | 835 (85.6) | 94 (9.6) | [7.9; 11.7] | 0.01 | CA > FBOp |

| Ireland | 178 | 118 (66.3) | 19 (10.7) | [6.6; 16.2] | 1,026 | 388 (37.8) | 72 (7.0) | [5.5; 8.8] | 0.04 | CA > FBOp |

| Italy | 491 | 397 (80.9) | 157 (32.0) | [27.9; 36.3] | 6,591 | 3,078 (46.7) | 707 (10.7) | [10.0; 11.5] | < 0.001 | CA > FBOp |

| Latvia | 100 | 56 (56) | 18 (18.0) | [11.0; 26.95] | 297 | 121 (40.7) | 54 (18.2) | [14.0; 23.1] | NS | – |

| Netherlands | 284 | 73 (25.7) | 26 (9.2) | [6.1; 13.1] | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Portugal | – | – | – | – | 3,601 | 868 (24.1) | 455 (12.6) | [11.6; 13.8] | – | – |

| Romania | 1,510 | 400 (26.5) | 62 (4.1) | [3.2; 5.2] | 2,090 | 612 (29.3) | 24 (1.2) | [0.74; 1.7] | < 0.001 | CA > FBOp |

| Slovenia | – | – | – | – | 784 | 564 (71.9) | 291 (37.1) | [33.7; 40.6] | – | – |

| Spain | 1,073 | 509 (47.4) | 313 (29.2) | [26.5; 32.0] | 695 | 292 (42.0) | 74 (10.7) | [8.5; 13.2] | < 0.001 | CA > FBOp |

| Sweden | – | – | – | – | 907 | 7 (0.77) | 7 (0.77) | [0.31; 1.6] | – | – |

| Total EU | 6,384 | 2,473 (38.7) | 1,138 (17.8) | [16,89; 18,79] | 46,259 | 14,503 (31.3) | 8,172 (17.6) | [17.3; 18.0] | NS | |

| Total EU providing CA and FBOp data | 4,162 | 1,754 (42.1) | 689 (16.6) | [15.4; 17.7] | 13,817 | 5,538 (40.1) | 1,232 (8.9) | [8.5; 9.4] | < 0.001 | CA > FBOp |

One‐sided, 97.5% confidence interval.

p‐value: NS, not significant.

Related to the percentage of positive samples above 1,000 CFU/g.

Ad hoc official sampling reported the test results for 6,384 units. The number of Campylobacter‐positive units totalled 2,473 (38.7%) with 1,138 (17.8%) exceeding the limit of 1,000 CFU/g. Moderate variability was observed in percentage test results exceeding the limit. In particular, one MS (Estonia) showed no units exceeding the limit and four MS (Croatia, Cyprus, Italy and Spain) showed a high number of units above the limit, ranging between 29.2% and 37.8%.

FBOp reported test results for 46,259 neck skin samples from own‐check sampling activities. The number of Campylobacter‐positive units detected totalled 14,503 (31.3%), with 8,172 (17.6%) exceeding the limit of 1,000 CFU/g. Two MS (Finland and Sweden) showed very low (< 1%) levels of positives exceeding the limit: 0.17% and 0.77%, respectively. Switzerland reported 183 positive units, of which 65 out of 780 tests exceeded the limit.

The eight MS (Belgium, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Romania and Spain) reporting results from both samplers showed 42.1% (N = 1,754) Campylobacter‐positive samples from carcases for official samples and 40.1% (N = 5,538) for samples collected by FBOp. The total number of units exceeding the limit in the eight MS was significantly higher in official samples (16.6%, N = 689) than in those based on own‐checks (8.9%, N = 1,232). For single MS, this was also the case for Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Romania and Spain.

When comparing all Campylobacter PHC monitoring data provided by 21 MS, the percentage of units exceeding the limit was comparable (not significantly different) between official samples (17.8%) and FBOp samples (17.6%).

Other food monitoring data

Table 8 summarises the reported occurrence of Campylobacter in the main food categories in 2020 and over the 4‐year period of 2016–2019 within the EU. A distinction is made between RTE and non‐RTE food, and fresh meat.

Table 8.

Occurrence of Campylobacter in the main food categories (RTE food – non‐RTE food), EU

| Food | 2020 | 2016–2019 a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N reporting MS | N sampled units | Positive N (%) | N reporting MS | N sampled units | Positive N (%) | |

| RTE food | ||||||

| All | 7 | 3,202 | 4 (0.12) | 15 | 9,827 | 19 (0.19) |

| Meat and meat products | 4 | 414 | 1 (0.24) | 10 | 1,145 | 4 (0.35) |

| Meat and meat products from broilers | 2 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 29 | 0 |

| Meat and meat products from turkeys | 2 | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Other meat and meat products | 4 | 398 | 0 | 9 | 1,107 | 4 (0.4) |

| Milk and milk products | 7 | 774 | 2 (0.26) | 11 | 2,645 | 10 (0.38) |

| Milk | 4 | 307 | 2 (0.65) | 6 | 817 | 8 (0.98) |

| Raw milk b | 4 | 304 | 2 (0.66) | 6 | 801 | 8 (1.0) |

| Cheese | 4 | 458 | 0 | 7 | 1,819 | 2 (0.11) |

| Dairy products excluding cheeses (butter, cream, ice cream, whey, yoghurt and fermented dairy products) | 2 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 0 |

| Fruit, vegetables and juices | 3 | 1,173 | 1 (0.09) | 6 | 2,228 | 3 (0.13) |

| Salads | 3 | 327 | 0 | 5 | 339 | 1 (0.29) |

| Other processed food products and prepared dishes | 3 | 326 | 0 | 5 | 277 | 0 |

| Non‐RTE food | ||||||

| All | 16 | 13,240 | 2,684 (20.3) | 21 | 71,870 | 16,675 (23.2) |

| Meat and meat products | 16 | 10,547 | 2,658 (25.2) | 21 | 65,761 | 16,594 (25.2) |

| Meat and meat products from broilers | 14 | 7,298 | 2,223 (30.5) | 17 | 35,854 | 12,006 (33.5) |

| Meat and meat products from turkeys | 6 | 1,169 | 251 (21.5) | 10 | 3,892 | 981 (25.2) |

| Other meat and meat products | 12 | 2,080 | 184 (8.6) | 17 | 26,015 | 3,607 (13.9) |

| Milk and milk products | 7 | 713 | 5 (0.70) | 9 | 2,080 | 47 (2.3) |

| Fruit, vegetables and juices | 3 | 443 | 1 (0.23) | 7 | 2,036 | 4 (0.20) |

| Other food | 5 | 1,536 | 20 (1.3) | 8 | 1,981 | 30 (1.5) |

| Fresh meat | ||||||

| All | 15 | 9,506 | 2,463 (25.9) | 19 | 57,660 | 15,327 (26.6) |

| Fresh meat from broilers | 14 | 6,747 | 2,031 (30.1) | 18 | 33,344 | 11,253 (33.6) |

| Fresh meat from turkeys | 6 | 1,077 | 226 (21) | 9 | 3,439 | 892 (26) |

| Fresh meat from pigs | 6 | 406 | 15 (3.7) | 7 | 1,989 | 107 (5.4) |

| Fresh meat from bovines | 3 | 242 | 1 (0.4) | 9 | 3,611 | 43 (1.2) |

| Other fresh meat | 9 | 378 | 95 (25.1) | 12 | 15,277 | 3,032 (19.9) |

RTE: ready‐to‐eat.

When UK data were collected for the period, the UK was an EU MS, but on 1 February 2020, it became a third country. Data from the UK are taken into consideration for the period 2016–2019, but not for 2020 in this EU overview.

Raw RTE milk sampling units are a subset of RTE milk.

The proportion of Campylobacter‐positive samples in the RTE and non‐RTE categories was 0.12% and 20.3%, respectively. In fresh meat, 25.9% of sampling units were positive.

In 2020, most of the results from the 3,202 RTE food sampling units reported by seven MS came from ‘fruit, vegetables and juices’ (36.6%), followed by ‘milk and milk products’ (24.2%) and ‘meat and meat products’ (12.9%). In total, Campylobacter was detected in four RTE food samples: two in ‘raw milk’, one in ‘fruit, vegetables and juices’ and one in ‘meat and meat products’. During the period 2016–2019, for RTE food, the percentage of Campylobacter‐positive sampling units was low, at below 1% for all categories. Over the entire period, the highest percentage of Campylobacter‐positive units was for ‘raw milk’: eight positives out of 801 (1%) sample units tested.

The results reported in 2020 by 16 MS for non‐RTE food show that ‘meat and meat products’ was the most contaminated food category, followed by ‘milk and milk products’ and ‘fruit, vegetables and juices’. Similar results were observed for the period 2016–2019.

Sixteen MS reported results for fresh meat categories. The percentage of Campylobacter‐positive units was highest for fresh meat from broilers (30.1%) followed by ‘other fresh meat’ (25.1%) and meat from turkeys (21%). The percentage for fresh meat from pigs and bovines remained relatively low; 3.7% and 0.4%, respectively. Similar results were observed for the period 2016–2019, except for meat from turkeys where the positive percentage was higher than for ‘other fresh meat’.

1.4.4. Campylobacter in animals

Table 9 shows the number of positive Campylobacter spp. samples detected during 2020 in the five main animal species, as well as in the ‘other animals’ category containing more than 50 different animal groups. Of the 20,891 units tested, Campylobacter was detected in 4,638 (22.2%) units. In total, 17 MS and four non‐MS reported data, primarily relating to broilers (65.2%), followed by bovines, turkeys, cats and dogs, and pigs. Sixteen countries reported data for broilers whereas only a few countries provided data for the other animal species. The proportion of positive units was highest in turkeys (62.1%) and pigs (58.5%) followed by broilers (24.5%), cats and dogs (15%) and finally bovines (5.1%). Although fewer samples were tested in ‘other animals’, a considerable proportion of positive units were detected in sheep (30.6%, N = 1,077), wild boars (19.6%, N = 61) and wild birds (15.4%, N = 279).

Table 9.

Summary of Campylobacter statistics related to major animal species, reporting MS and non‐MS, 2020

| Animals | N reporting MS/non‐MS | N tested units a in EU | Positive units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||

| Broilers | 14/2 | 13,625 | 3,340 | 24.5 |

| Turkeys | 4/1 | 1,360 | 845 | 62.1 |

| Pigs | 3/0 | 147 | 86 | 58.5 |

| Bovines b | 3/1 | 2,613 | 134 | 5.1 |

| Cats and dogs | 4/3 | 538 | 81 | 15.1 |

| Other animals c | 5/3 | 2,608 | 152 | 5.8 |

MS: Member State.

Summary statistics were obtained by totalling all sampling units (single samples, batch samples, animals, slaughter animal batches and herds or flocks).

‘Artificial insemination stations’ at the ‘sampling stage’ were not included in the count of the units tested.

Badgers – wild, Bears – zoo animals, Birds – pets, Birds – wild, Birds – zoo animals, Camels – zoo animals, Canaries – pets, Cantabrian chamois – wild, Deer – wild, Deer wild ‐ fallow deer, Deer ‐ wild ‐ red deer, Deer ‐ wild ‐ roe deer, Deer ‐ zoo animals, Dolphins, Doves – wild, Elephants ‐ zoo animals, Falcons – wild, Ferrets – wild, Foxes, Foxes – wild, Giraffes ‐ zoo animals, Goats, Goats ‐ animals over 1 year, Guinea pigs – pets, Hares – wild, Hedgehogs – wild, Kangaroos ‐ zoo animals, Land game mammals, Lions ‐ zoo animals, Marine mammals – wild, Monkeys ‐ zoo animals, Other animals ‐ exotic pets, Other ruminants ‐ zoo animals, Parrots – pets, Parrots – wild, Peafowl, Pigeons, Pigeons – wild, Rabbits – farmed, Rabbits – pets, Rats – wild, Rhinoceroses ‐ zoo animals, Rodents ‐ zoo animals, Sheep, Sheep ‐ animals over 1 year, Sheep ‐ animals under 1 year (lambs), Solipeds, domestic – donkeys, Solipeds, domestic – horses, Swans – wild, Turtles – wild, Water buffalos, Wild boars – farmed, Wild boars – wild, zoo animals, all.

1.5. Discussion

Campylobacteriosis has been the most frequently reported zoonosis in humans across the EU since 2005. Despite comprehensive surveillance and national coverage in most MS, the number of reported cases is underestimated in the EU (Teunis et al., 2013). In 2019, in two‐thirds of the EU MS, the number of confirmed campylobacteriosis cases decreased. A fall in cases was also observed in 2020, probably due to the COVID‐19 pandemic and the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU. However, the overall campylobacteriosis trend in 2016–2020 showed no statistically significant increase or decrease.

Compared with 2019, a major decrease in travel‐associated campylobacteriosis cases was observed. The lockdown measures put in place across the EU, as well as national/international mobility restrictions caused by air, sea and/or land border closures in some countries, could have contributed to this phenomenon.

Campylobacter has a characteristic seasonality with cases increasing sharply in the summer. Campylobacteriosis cases have been positively associated with temperature and, to a lesser degree, precipitation (Lake et al., 2019). However, a smaller but distinct winter peak has become apparent in the past 10 years in the EU, including in 2020. Disease onsets concerning cases that were notified during the winter peaks occurred predominantly in January. This points to exposure around the Christmas/New Year period. In some of the countries where a winter peak was observed, meat fondues or table‐top grilling are popular during the festive season and could promote the transmission of Campylobacter (Bless et al., 2017). The significant reduction in the number of cases observed in spring 2020 is probably due to the COVID‐19 pandemic and the implementation of lockdown measures across the EU.

Within the EU, over 8,500 campylobacteriosis cases were hospitalised and it was by far the foodborne agent associated with the highest number of hospitalisations. The proportion of hospitalised campylobacteriosis cases was higher than expected in some MS, where all or most of the confirmed cases were hospitalised. These MS also reported the lowest notification rates, indicating that surveillance focuses primarily on hospitalised (i.e. severe) cases. This can lead to the number of hospitalised cases being overestimated in some countries. As in previous years, C. jejuni and C. coli were the main species notified by MS, but there was still a high percentage (35.3%) of campylobacteriosis cases in which the Campylobacter species was not determined.

In 2020, as part of a food control strategy, it became mandatory to report data from the Campylobacter PHC on the neck skins of chilled broiler carcases, as stated in the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627. According to this legislation, the CA must verify whether the FBOp is correctly implementing the PHC, either by ad hoc official sampling or by collecting the relevant information on the test analyses carried out by the FBOp for own‐check purposes. Overall, 21 MS submitted their data, compared with 14 for 2019. Of this total, eight MSs reported both official and own‐check results, four only official results and nine only own‐check results. An increase in the number and percentage of Campylobacter‐positive units was noted compared with the numbers from 2019. In respect to the previous year, it is worth noting an increase in the number of samples reported and the number of MS declaring their data. This increase was expected, in the light of the need to comply with the EU regulation. The percentage of positives from broiler neck skins, as set out in the current report, is significantly lower than from broiler carcases in the 2008 EU harmonised survey: 75.8% (EFSA, 2010). This difference could be attributed to the different sampling methods, and to the sole use of the enumeration method for the Campylobacter PHC, negatively impacting the sensitivity of the tests performed. Better populated EU summary tables with more complete data sets from all MS will in future allow better trend watching and trend analyses.