Abstract

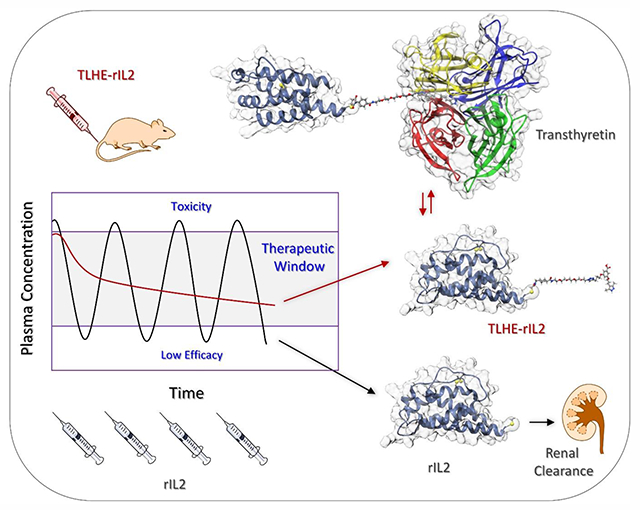

Protein drugs hold great promise as therapeutics for a wide range of diseases. Unfortunately, one of the greatest challenges to be addressed during clinical development of protein therapeutics is their short circulation half-life. Several protein conjugation strategies have been developed for half-life extension. However, these strategies have limitations and there remains room for improvement. Here we report a novel nature-inspired strategy for enhancing the in vivo half-life of proteins. Our strategy involves conjugating proteins to a hydrophilic small-molecule that binds reversibly to the plasma protein, transthyretin. We show here that our strategy is effective in enhancing the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of human interleukin 2 in rats, potentially opening the door for more effective and safer cancer immunotherapies. To our knowledge, this is the first example of successful use of a small-molecule that not only extends the half-life but also maintains the smaller size, binding potency, and hydrophilicity of proteins.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The revolution of the biotechnology field over the last few decades has resulted in more than 200 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved recombinant protein therapeutics.1 These biotherapeutics are available as hormones, enzymes, clotting factors, cytokines, and antibodies, which are used to treat critical diseases such as cancer, diabetes, HIV, and multiple sclerosis.2,3 The biotherapeutics field is expected to experience an exponential growth due to the development of various biotechnological advances and the emerging role of artificial intelligence in predicting the structure of endogenous proteins and generating novel biotherapeutics.4

One of the greatest challenges to be addressed during the clinical development of protein therapeutics is their short circulation half-life due to rapid renal clearance and enzymatic degradation in plasma and liver.5,6 The half-lives of many protein therapeutics that are less than 50 kDa in size typically range from minutes to hours.7,8 Therefore, frequent administration of higher doses is usually required, which results in large fluctuation in the peak-to-trough plasma concentrations, causing lower efficacy and toxic side effects.5 Most FDA-approved recombinant proteins are identical or similar in their amino acid sequence to the natural proteins, and therefore display similar poor pharmacokinetic profiles to their natural counterparts. Therefore, over the past three decades several strategies have been developed for extending the half-lives of therapeutic proteins.5,7,8

It is estimated that only 15% of FDA-approved therapeutic proteins are modified by half-life extension strategies, which mostly aim at reducing renal clearance of proteins by simply increasing their size and hydrodynamic volume.1,7 Conjugation to polyethylene glycol (PEGylation) is the most common half-life extension strategy.9,10 More than ten PEGylated proteins are approved for various therapeutic indications, and most of these were generated by random conjugation to lysine groups in the protein drug.9–11 While the large size of the PEG polymer (~20–40 kDa) can decrease renal filtration of proteins, the bulk of the PEG polymer can also reduce the potency of a protein drug, mainly by sterically hindering the binding of the protein to its target receptor.7 PEGylation is generally recognized by the FDA as safe, however, PEG is not 100% safe. PEG is non-biodegradable and has been shown to form vacuoles in organs such as kidneys, liver, and spleen.12 It is estimated that ~25% of healthy individuals already contain anti-PEG antibodies, possibly due to previous exposure to PEG in various food and cosmetics products.13 The presence of these anti-PEG antibodies raises the potential for allergic reactions to PEG in certain patient populations and also accelerates clearance of biotherapeutics from circulation upon repeated exposure to PEGylated protein drugs.

Genetic fusion to albumin and Fc proteins represents another promising class of approved biotherapeutics with extended half-lives.5,7,8 However, this approach is more complex than PEGylation due to the need for optimizing the solubility and stability of the fusion protein. Similar to PEGylation, the steric bulk of the fusion partner often decreases the biological activity of the modified protein compared with the native protein. Therefore, although these strategies have sometimes been successful, they have limitations and there remains room for improvement. These deficiencies have led researchers to investigate alternative half-life extension strategies.5,8,10 However, most of the new technologies depend on increasing the size by conjugation to large polymers or proteins, and therefore share some of the limitations of PEGylation and genetic fusion. Therefore, novel strategies that enhance the pharmacokinetic properties along with additional advantages such as maintaining the potency and small size of protein drugs will be important to advance the field of protein therapeutics and to develop next generation biotherapeutics.

We have previously reported a new strategy for extending the circulation half-life of small peptides without compromising their potency, which we term transthyretin ligands for half-life extension (TLHE) approach.14 Our approach involves endowing peptides with a derivative of the small molecule, AG10, that binds reversibly to the serum protein transthyretin (TTR) (Scheme 1). AG10 was discovered by our group and is currently in Phase III clinical trials for TTR amyloid cardiomyopathy.15 TTR is a 55 kDa tetrameric protein that is secreted from liver into blood and has a circulation half-life of ~48 h. The main function of TTR in human (concentration ~5 μM) is to transport holo-retinol binding protein (RBP bound to retinol or vitamin A) in blood. Using orthogonal sites to those of holo-RBP, TTR acts as a back-up carrier of thyroxine (<1% thyroxine bound). AG10 and TLHEs bind to the two thyroxine sites in TTR and do not interfere with the interaction between TTR and holo-RBP.14,15 The apo-RBP (RBP without retinol) has low affinity for TTR and therefore, owing to its relatively small size (21 kDa), undergoes fast renal excretion (half-life ~3.5 h).16 Reversible association between holo-RBP and TTR in blood (holo-RBP–TTR complex; ~76 kDa) decreases glomerular filtration of holo-RBP, which results in a threefold increase in its circulation time (half-life ~11 h).16 Inspired by how the human body enhances the circulation half-life of holo-RBP, and based on our success with small peptides, we hypothesized that the TLHE approach could also work for protein drugs. Owing to the reversible binding of these AG10 ligands to TTR, the intrinsic activity of the protein conjugates would not be adversely affected.

Scheme 1.

Chemical Structure of AG10 and Tafamidis and Chemical Synthesis of TLHE (3). a) Azido-PEG4-amine, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, THF/H2O (4:1), rt, 16 h; b) N-Succinimidyl 4-(N-Maleimidomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxylate, DIPEA, DMF, rt, 16 h.

We decided to test our TLHE approach with cytokines, a large family of immunoregulatory proteins that are <30 kDa.17 Cytokines are involved in many pathological states with promising potential as therapeutic agents for cancers, autoimmune, infectious, and inflammatory diseases.18 The poor pharmacokinetics of cytokines is a major challenge associated with their clinical use, and therefore various half-life extension strategies are being applied to reduce their toxicity while maintaining potency.19 While PEGylation is the most common half-life extension approach for cytokines, only a handful of PEGylated cytokine therapeutics have received FDA approval.10,18 Unfortunately, even for the five approved PEGylated cytokines, PEGylation reduces protein activity by hindering the binding of the cytokine to its receptor. For example, peginterferon α-2a (Pegasys; conjugated to 40 kDa PEG) retains less than 10% of the original potency of interferon α-2a.20

Human interleukin 2 (IL2), a cytokine with poor pharmacokinetic profile, was chosen for our approach. Recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL2) has a very short half-life in humans (distribution and elimination phases are 13 and 85 minutes, respectively).21 Because of the small size of rIL2 (~16 kDa), it is rapidly cleared by renal filtration and metabolism in the kidneys.22,23 While immunotherapy with rIL2 has showed complete cancer regression in 10% of patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cancer,24 administering high doses of rIL2 often results in severe hypotension and vascular leak syndrome.25 Therefore, rIL2 has to be administered in intensive care units at specialized cancer centers via 15-minute intravenous infusion every 8 hours for a maximum 14 doses.21,26 This dosing schedule is repeated for another 14 doses after 9 days of rest. Unfortunately, the side effects profile restricts optimal dosing, limiting the number of patients who might achieve durable response.

PEGylation of rIL2 has been widely explored in the literature, therefore it represents an excellent case to compare with our TLHE half-life extension approach. It has been shown that PEGylation of rIL2 changes the selectivity of rIL2 to the various IL2 receptor subunits. For example, conjugating one or two 20 kDa PEG polymers to rIL2 resulted in 73-fold and 161-fold reduction, respectively, in the binding affinity to rIL2 receptor αβ.27 While PEGylation extended the half-life of rIL2,28,29 clinical trials of PEG-IL2 in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma did not show significant differences in efficacy over treatment with unconjugated rIL2.30 Here, we show that by conjugating rIL2 to a small molecule TLHE ligand (molecular weight = 837 Daltons), we generated rIL2 derivatives that displayed extended circulation half-life in rats and at the same time retained its binding affinity to the IL2 receptor. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a successful use of small molecule to extend the in vivo half-life of a therapeutic protein without affecting its overall size or binding potency.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression of a recombinant rIL2.

Native human IL2 is a 133 amino acids cytokine that is glycosylated at threonine 3. A disulfide bond between cysteines 58 and 105 is required for biological activity.31 The amino acid sequence of our rIL2 is based on the structure of the FDA-approved rIL2, aldesleukin (Figure 1A and Figure S1). The first amino acid in aldesleukin (alanine 1) was removed and cysteine 125 was mutated to serine. These two modifications have been reported to both maintain the biological activity of rIL2 and to reduce the intermolecular disulfide bridges (between cysteine 125 and cysteines 58 or 105), thus improving the refolding and stability of the protein. An engineered cysteine was introduced at position 3 of the rIL2 sequence, replacing the naturally occurring threonine in IL2. Cysteine 3 will provide the thiol group for conjugation to a maleimide group in TLHE. This threonine-3-cysteine mutation has also been reported earlier to provide a good conjugation site for small PEG polymers.32 In addition, our analysis of the crystal structure of IL2 revealed that position 3 is solvent accessible and is not located in the interaction surface between IL2 and IL2 receptor (Figure 1B and 1C). The recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli system and purified using affinity chromatography (~95% purity).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence of rIL2. (A) The amino acids highlighted in red font or boxed indicate differences from the native IL2. The N terminal alanine, which is present in native IL2, was removed in our rIL2. Cysteine 125 was mutated to serine to improve the refolding and stability of the protein. Threonine 3 was mutated to cysteine to provide the site for thiol-maleimide conjugation. Hexa-histidine (6His) tag was introduced into the C-terminal end for the metal-affinity purification. (B) and (C) are different views of the binding of rIL2 to the heterotrimeric IL2 receptor (pdb id: 2ERJ) highlighting solvent accessibility of threonine 3 residue (red sphere) at the N-terminus of rIL2.

Design and Synthesis of TLHE Used for Conjugation.

We have previously developed a series of TLHEs that were used effectively in extending the in vivo half-life of both hydrophilic peptides and hydrophobic anticancer agents.14,33 One of these TLHEs, compound 1, is a small-molecule TTR ligand that has a linker equipped with a terminal alkyne group (Scheme 1). The alkyne group of 1 allowed us to functionalize the linker with a maleimide group which could potentially be used for conjugation to a cysteine group in rIL2. A short ethylene glycol spacer containing an amine group was first attached to 1 using CuAAC click reaction to give compound 2. Maleimidomethyl cyclohexane-1-carboxylate, a functionality used in the approved ADC Trodelvy, was incorporated into 2 to give 3. The hydrophilic spacer in TLHE (3) is designed to serve two purposes. First, it will enhance the hydrophilicity of TLHE, which is important for maintaining the aqueous solubility of the protein conjugate. Second, our modeling studies suggested that extending the linker of TLHEs to a length of ~20 Å should be sufficient to extend out of the TTR thyroxine binding sites and potentially be functionalized with proteins. The total length of the entire linker system in TLHE is ~32 Å, intentionally designed to be longer than 20 Å, which should allow the TLHE-rIL2 conjugate to interact with both TTR and IL2 receptor without any steric interference. The synthesis of TLHE is described in Scheme 1. This approach allowed for efficient generation of TLHE (3) with high purity (>95% purity by HPLC analysis).

Conjugation of TLHE (3) to rIL2.

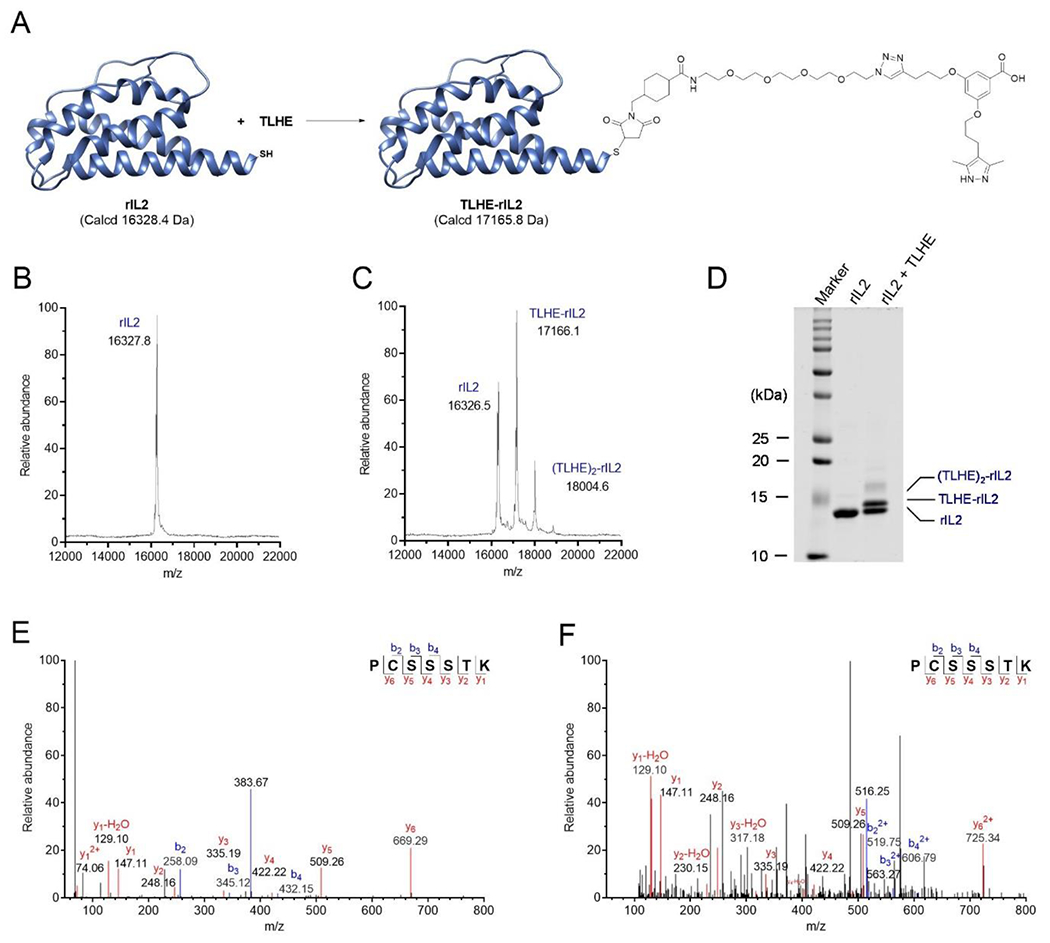

The thiol-maleimide reaction between TLHE (3) (6-fold molar excess) and rIL2 was carried out in 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 6.5 (Figure 2A). At the end of the reaction, excess TLHE was removed by dialysis. In parallel, rIL2 was treated the same way as the TLHE/rIL2 reaction (but without the presence of TLHE) to make sure that conjugation process does not change conformation or bioactivity of rIL2. The removal of excess TLHE by dialysis was confirmed by analytical HPLC (Figure S2). To ensure the dialysis is effective in removing excess TLHE, a TLHE sample in buffer was subjected to dialysis followed by analytical HPLC, which also showed that no residual unreacted TLHE remained (Figure S2). The degree of conjugation was evaluated using matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Figure 2B and 2C). First, we used MALDI-TOF MS to confirm the mass of rIL2 (m/z value of 16327.8; Figure 2A and 2B). The MALD-TOF MS for the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture showed three peaks, 16326.5, 17166.1 and 18004.6, which correspond to the unlabeled rIL2, rIL2 labeled with one TLHE (i.e., the desired TLHE-rIL2 product), and rIL2 labeled with two molecules of TLHE, which we refer to as (TLHE)2-rIL2, respectively (Figure 2A and 2C). The results from MALDI-TOF MS were then confirmed by resolving the protein samples using SDS-PAGE under reducing condition. As expected, there was a single band for rIL2 and three bands for the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture sample (Figure 2D), which is consistent with the three different m/z values found in the MALDI-TOF MS data. The band intensities in the gel were used to calculate the percentage of each species in the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture (rIL2 = 47%; TLHE-rIL2 = 42%; and (TLHE)2-rIL2 = 11%).

Figure 2.

Bioconjugation of rIL2 with TLHE (3). (A) Schematic of the reaction of rIL2 with TLHE to generate TLHE-rIL2. (B) MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of rIL2. (C) MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of the TLHE-rIL2 conjugation reaction mixture. (D) SDS-PAGE analysis for the rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 conjugation reaction. Lane 1: Prestained marker; Lane 2: unlabeled rIL2; Lane 3: TLHE-rIL2 conjugation reaction mixture. (E) MS/MS spectrum of the m/z 383.67 double charged ion of the tryptic peptide PC(+57.02)SSSTK, containing the carbamidomethyl modification at the cysteine 3 residue. (F) MS/MS spectrum of the m/z 516.25 triple charged ion of the tryptic peptide PC(+837.43)SSSTK, containing the TLHE modification at the cysteine 3 residue.

Our assignment of the three bands in the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture was further confirmed by in-gel tryptic digest and LC-MS/MS analysis. The single band on the SDS-PAGE of rIL2 and the three bands of TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture were excised separately and then subjected to in-gel tryptic digest and LC-MS/MS analysis. Peptide sequence PC(+57.02)SSSTK (Figure 2E) was found for both the rIL2 control and the bottom band from the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture, which confirmed that the bottom band is the unreacted rIL2. A mass increase of 57.02 in cysteine indicated a carbamidomethyl modification of the free cysteine. Compared with the unreacted rIL2 control, the modified sequence PC(+837.43)SSSTK (Figure 2F) was found for the middle band in the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture, which demonstrated that the middle band is the expected TLHE-rIL2 conjugation product. The mass spectrum for the minor upper band indicated the labeling of rIL2 with two TLHE molecules.

Preliminary attempts to separate the desired TLHE-rIL2 from unreacted rIL2 using reverse phase HPLC were not successful. The small size of TLHE does not significantly change the overall size of TLHE-rIL2 compared to rIL2, and therefore it is unlikely that TLHE-rIL2 can be separated from rIL2 by size exclusion chromatography. In addition, the hydrophilicity of TLHE (the AG10 portion exists as a zwitterion at physiological pH)34 made it difficult to separate the two proteins using reverse-phase HPLC (Figure S2). Therefore, rather than exploring other protein separation methods, we decided to proceed with the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture without purification. Therefore, for all subsequent experiment, for simplicity we will refer to the TLHE-rIL2 reaction mixture as “TLHE-rIL2”. We also made sure that all subsequent sections will clearly address the presence of ~50% unlabeled rIL2 in the “TLHE-rIL2” sample.

Evaluation of Binding Affinity and Selectivity of TLHE-rIL2 to TTR in Buffer and Human Serum.

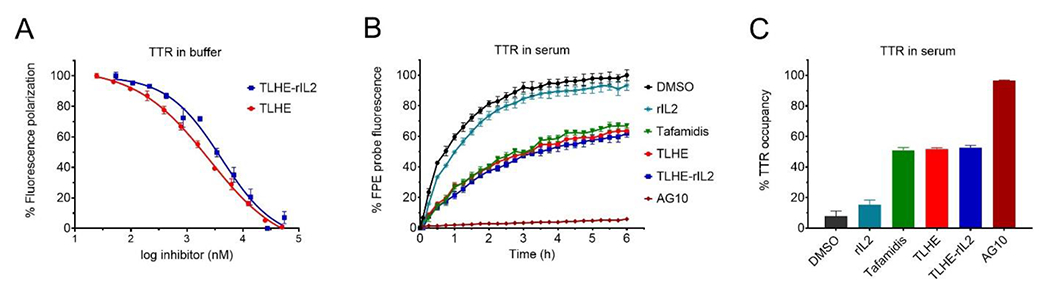

The binding affinity (Kd) of TLHE (3) and TLHE-rIL2 to human TTR was evaluated using fluorescence polarization (FP) binding assay.35 There was no binding affinity of rIL2 to TTR. TLHE (Kd = 516 nM) and TLHE-rIL2 (Kd = 851 nM) displayed binding affinity to TTR that is comparable to the other TLHE conjugates that we have reported earlier14,33 (Figure 3A). It is important to note that the binding affinity of TLHE-rIL2 is likely underestimated because ~50% of the TLHE-rIL2 sample is rIL2.

Figure 3.

Binding affinity and selectivity of test compounds to TTR in buffer and human serum (A) Evaluation of the binding affinity of TLHE (3) (Kd = 516 nM) and TLHE-rIL2 (Kd = 851 nM) to TTR in buffer using fluorescence polarization assay. The binding constant (Kd) values were calculated using the Cheng−Prusoff equation from IC50 values. Data represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 3). (B) Fluorescence change caused by modification of TTR in human serum (TTR concentration, ~5 μM) by covalent FPE probe monitored for 6 h in the presence of FPE probe alone (black circles) or probe and TTR ligands (colors; 10 μM). The lower the binding and fluorescence of FPE probe, the higher is the binding selectivity of ligand to TTR. (C) Bar graph representation of percent occupancy of TTR in human serum by test compounds in the presence of FPE probe measured after 3 h of incubation relative to probe alone. Error bars indicate mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

For our approach to be successful in vivo, TLHE-rIL2 should be able to selectively bind to TTR in the presence of more than other 4000 human serum proteins. We evaluated the selectivity of TLHE and TLHE-rIL2 binding to TTR in human serum using a well-established TTR serum fluorescent probe exclusion (FPE) selectivity assay.36,37 The FPE assay utilizes a fluorogenic probe, which is not fluorescent by itself. However, when the FPE probe binds to the thyroxine binding site of TTR, it covalently modifies lysine 15 at the periphery of the thyroxine pocket, creating a fluorescent conjugate. Ligands that bind selectively to TTR in serum decrease the binding of FPE probe to TTR, thus lowering the fluorescence. Our data demonstrated that both TLHE and TLHE-rIL2 maintained very good binding selectivity toward TTR (51.8 ± 0.9%, and 52.6 ± 1.5% TTR occupancy, respectively) (Figure 3B and 3C). Importantly, the performance of both TLHE and TLHE-rIL2 were similar to that of the TTR stabilizer, tafamidis (an approved drug for TTR amyloidosis; 50.9 ± 1.9% TTR occupancy).

Evaluating the Potency of TLHE-rIL2 in Cells Expressing IL2 Receptor.

The bioactivity of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 was evaluated by measuring CTLL-2 cell proliferation in response to IL-2 stimulants. The CTLL-2 cell line (cytotoxic T lymphocyte), which expresses the high-affinity mouse IL2 receptor, is dependent upon IL2 for growth. The cell proliferation assay showed that the potency of rIL2 (EC50 = 0.42 ng/mL) and TLHE-rIL2 (EC50 = 0.51 ng/mL) were similar to the potency of the FDA approved, aldesleukin (EC50 = 0.60 ng/mL) (Figure 4A and Figure S3). Since there is ~50% of unlabeled rIL2 in the TLHE-rIL2 sample, we wanted to eliminate the possibility that the bioactivity of TLHE-rIL2 was contributed mainly from the 50% of unlabeled rIL2. We prepared 50% unlabeled rIL2 by adding the same amount of human albumin into the rIL2 sample and tested the protein mixture potency in the cell proliferation assay. The data showed that there was a 2-fold increase in the EC50 of rIL2 + albumin sample (EC50 = 0.85 ng/mL) compared to rIL2 (Figure 4B). These data demonstrated that after labeling rIL2 with TLHE, the protein conjugate still maintained its bioactivity. We also tested TLHE-rIL2 in the presence of TTR (50 nM; ~40-fold molar excess than the highest TLHE-rIL2 concentration used). There was no significant effect of TTR on the ability of TLHE-rIL2 to promote cell growth (Figure 4C). These data are supported by modeling studies which show that TLHE-rIL2 can interact freely with TTR through a flexible linker that has ~20 Å distance between the surfaces of both TTR and rIL2 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

CTLL-2 cell proliferation assay to evaluate the bioactivity of (A) rIL2 (EC50 = 0.42 ng/mL) and TLHE-rIL2 (EC50 = 0.51 ng/mL), (B) IL-2 sample containing albumin (1:1 ratio; EC50 = 0.85 ng/mL), and (C) TLHE-rIL2 in the presence or absence of 50 nM TTR (EC50 = 0.50 ng/mL and 0.56 ng/mL, respectively). The y-axis in A-C represents the measured absorbance, which directly correlates with the number of viable CTLL-2 cells. The higher the absorbance the higher the cell viability. (D) Modeled complex illustrating binding of TLHE-rIL2 to TTR and the IL2 receptor. The distance between the surfaces of TTR and IL2 receptor is ~20 Å which allows TLHE-rIL2 to interact freely with both proteins.

TTR extended the circulation half-life of TLHE-rIL2 in rats.

We have evaluated the pharmacokinetic properties of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 in rats. rIL2 or TLHE-rIL2 (0.8 mg/kg) were administered as single intravenous doses to jugular vein cannulated male Sprague Dawley rats. Blood samples were withdrawn from the jugular vein cannula at predetermined time points (ranging from 2 min to 24 h) and concentrations of test compounds were quantitated using a commercially available IL2 detection ELISA kit (Figure 5A and Figure S4). The pharmacokinetic profile of TLHE-rIL2 was markedly different than rIL2. While there was no measurable amount of rIL2 after 8 h, TLHE-rIL2 was still present even after 24 h (Figure 5A). There was ~4-fold increase in the half-life of TLHE-rIL2 compared to rIL2 (half-life = 5.22 ± 0.6 h vs. 1.26 ± 0.18 h, respectively). Importantly, the mean residence time (MRT) (~8-fold higher; 8.76 ± 0.74 h for TLHE-rIL2 and 1.04 ± 0.07 h for rIL-2) and AUC (exposure) (~5-fold higher; 1219.47 ± 53.48 ng.h/mL for TLHE-rIL2 and 251.22 ± 11.60 ng.h/mL for rIL-2) were significantly higher for TLHE-rIL2 than rIL-2. This data strongly supports and validates our approach that TTR recruitment can indeed enhance the half-life and pharmacokinetic profile of TLHE-rIL2 in vivo.

Figure 5.

TLHE-rIL2 displayed enhanced pharmacokinetic properties in rats and superior ex vivo efficacy compared to rIL2. (A) Evaluation of the pharmacokinetic properties of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 in rats. Single intravenous bolus dose of rIL2 or TLHE-rIL2 (0.8 mg/kg) was administered to two groups of male rats (n = 3 for each group). The concentration of test compounds in plasma was determined using ELISA. Concentrations are expressed as means ± s.d. of three biological replicates. (B) Evaluating the ex vivo efficacy of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2. The 2 min (0.03 h), 8 h and 24 h plasma samples from the pharmacokinetic study were evaluated for their ex vivo efficacy to promote the CTLL-2 proliferation. For negative control, cells were treated with blank rat plasma. For the 2 min sample, it was first diluted 2-fold with blank rat plasma and then added into the cells as described above. Bar graph showed the respective mean ± s.d. (n = 6). The significance of differences was measured by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (ns, not significant; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001).

Binding to TTR enhanced the ex vivo efficacy of TLHE-rIL2.

The 2 min, 8 h and 24 h plasma samples from the rat pharmacokinetic study were evaluated for their ex vivo efficacy in the CTLL-2 cell proliferation assay described above (Figure 5B). The comparable efficacy at 2 min for rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 is consistent with the similar potency obtained for both molecules (EC50 = 0.42 ng/mL and 0.51 ng/mL, respectively) (Figure 4A). While the activity of rIL2 group declined at 8 h, there was a significantly higher level of activity for TLHE-rIL2 compared to rIL2 at 8 h. Importantly, the activity of TLHE-rIL2 was maintained for at least 24 h (Figure 5B). This efficacy data correlates well with our pharmacokinetic data and strongly shows that the enhanced ex vivo efficacy of TLHE-rIL2 is a result of its extended circulation half-life, mainly due to its binding to TTR.

CONCLUSIONS

Protein half-life extension approaches have been recognized, by both academia and the pharmaceutical industry, as an integral part of the development of protein drugs. Although many of these technologies have been successful in enhancing the half-lives of certain biotherapeutics, they often adversely affect other parameters such as binding potency, biodistribution, tissue penetration, stability, immunogenicity, and manufacturing. We believe that the TLHE system would complement and address some of the shortcomings of these technologies by specifically enhancing the pharmacokinetic properties of small proteins. The smaller size and non-peptidic nature of TLHE could offer several additional advantages such as maintaining binding potency, lower antigenicity, lower production cost, and chemical stability. For example, maintaining the small size of biotherapeutics has been recognized in developing imaging and targeted biotherapeutics with better tumor penetration, especially in the case of solid tumors. While some other approaches could extend the half-life of proteins to several days or weeks, the TLHE system would be preferred for certain applications where prolonged exposure is undesirable or the duration of action has to be temporally restricted. Therefore, our TLHE system would be a valuable addition to the toolbox for enhancing the efficacy of protein therapeutics.

Here we show that our novel TLHE approach is successful in improving the pharmacokinetic profile and ex vivo efficacy of rIL2. An important advantage of the TLHE system is maintaining the hydrophilicity of the conjugated proteins as indicated by our HPLC analysis. This is particularly important for proteins with limited solubility at physiological pH, such as rIL2, where fatty acid conjugation is not an option for half-life extension.38 The new TLHE-rIL2 conjugate we developed has the potential to decrease rIL2 toxicity and increase its clinical success rate for renal cancers and melanoma, which is a tough cancer to treat because it is typically resistant to many drugs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a successful approach that not only extends the circulation half-life but also maintains the smaller size, binding potency, and hydrophilicity of proteins. We believe that there is likely room for further improvement in half-life of rIL2 and other proteins through improving the affinity of the TLHE ligand to TTR. This could provide the strategy with the potential to be optimized for a tunable half-life extension of proteins.

Like many cytokines, rIL2 is hydrophobic protein that is prone to aggregation. In addition, rIL2 is structurally more stable at pH 4 than at pH 7 and has limited solubility at neutral pH. For these reasons, sodium dodecyl sulfate is included in the commercial formulation of aldesleukin. The hydrophobicity of rIL2 and poor solubility at pH 7 makes it challenging for efficient thiol-maleimide reaction. Similar to the results of our conjugation reaction, previous attempts to conjugate rIL2 with excess PEG-maleimide (4.5-fold molar excess; performed at pH 5.5) also resulted in mixture of unmodified rIL2, single PEGylated rIL2, and multiple PEGylated rIL2.32 Future work will focus on optimizing the efficiency of the conjugation process and the separation of TLHE-rIL2 from rIl2, which will result in additional enhancement of the pharmacokinetic profile of the conjugate. For example, performing the coupling at neutral pH in the presence of various co-solvents or introducing a short hydrophilic amino acid spacer between an engineered cysteine and the N-terminus of rIL2 might be helpful.

There are more than twenty thousand proteins that are expressed by the human genome, many of which could be utilized to treat various diseases. In addition, the emerging artificial intelligence programs are predicted to revolutionize the field of biotherapeutics by predicting the structures of millions of endogenous and non-endogenous proteins. Therefore, there will be an exponential growth in the number of proteins that could be utilized as therapeutics. Developing protein half-life extension approaches will continue to be an exciting field requiring interdisciplinary collaboration between biologists, chemists, physicists, and pharmacologists. Based on the success of our TLHE with peptides, small hydrophobic molecules, and in this report with proteins, we envision that our approach could potentially be applicable for enhancing the in vivo pharmacokinetic properties and hydrophilicity of oligonucleotides, oligosaccharides, and liposomes. This should broaden the scope and utility of our approach.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of rIL2.

The cDNA sequence of rIL2 (Figure S1) was chemically synthesized and subcloned into the pRSET A vector between the NdeI and XhoI restriction endonuclease sites through Invitrogen GeneArt Gene Synthesis. The constructed pRSET A plasmid was then transformed into the BL21(DE3) pLysS (Fisher Scientific, catalog No. C606010) following the basic transformation procedure of the competent cells. For large scale expression (1.2 L), a single colony was first inoculated into 200 mL of LB broth with 50 μg/mL ampicillin (Gold Biotechnology, catalog No. A-301–10) and 35 μg/mL chloramphenicol (Fisher Scientific, catalog No. AAB2084114), followed by incubation at 37 °C, 225 rpm overnight. The overnight culture was added into 1 L of fresh LB broth with 50 μg/mL ampicillin and 35 μg/mL chloramphenicol. And then, 1 mM IPTG (Gold Biotechnology, catalog No. I2481C25) was added, followed by further incubation at 37 °C, 225 rpm for 6 h. After that, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and stored as pellet in −80 °C.

For purification, the pellet was resuspended into 25 mM HEPES buffer with 10% glycerol, 0.3 M KCl (pH 7.4), and lysed using sonication. The pellet was carefully separated from the supernatant after centrifuging at 16,000 g for 30 min at 18 °C and washed again with 25 mM HEPES buffer. Then the insoluble materials were resuspended into 6 M GuHCl buffer (100 mM Tris, 6M GuHCl, 0.3 M NaCl, pH 8), incubated at room temperature for 1 h, followed by sonication for 1 min on ice. After centrifuging at 16,000 g for 30 min at 18 °C, the resulting obtained supernatant was loaded on pre-equilibrated cobalt resin (Gold Biotechnology; catalog No. H-310–100) for metal-affinity purification. The enriched protein fractions were eluted with the elution buffer (100 mM Tris, 6 M GuHCl, 0.3 M NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8).

To refold the protein, this enriched protein fraction was first diluted to 1 mg/mL with the elution buffer and then brought to a concentration around 0.1 mg/mL with a buffer (pH 8) containing 1.1 M guanidine, 100 mM Tris, 6.5 mM cysteamine, and 0.65 mM cystamine. The solution was equilibrated at room temperature for 16 h, followed by dialysis in 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.5). The precipitate formed during the dialysis process was removed by centrifugation. Finally, the refolded protein was concentrated using the Amicon Ultra-15 device and then stored at −80 °C.

Chemical Synthesis and HPLC Purity Analysis

Materials for Chemical Synthesis.

All reactions were carried out under an argon or nitrogen atmosphere using dry solvents under anhydrous conditions, unless otherwise noted. The solvents used were ACS grade from Fisher. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL JNM−ECA600 spectrometer and calibrated using residual undeuterated solvent as an internal reference. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were determined by JEOL AccuTOF DART using Helium as an ionization gas and polyethylene glycol (PEG) as an external calibrating agent. Coupling constants (J) were expressed in Hertz. All compounds were >95% pure by analytical HPLC (Figure S5).

3-(3-(3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)propoxy)-5-(3-(1-(1-(4-((2,5-dioxo-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)methyl)cyclohexyl)-1-oxo-5,8,11,14-tetraoxa-2-azahexadecan-16-yl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)propoxy)benzoic acid (TLHE) (3).

The synthesis of TLHE was carried out as described in Scheme 1. TTR ligand 114 was first converted to 2 using the CuAAC click reaction. Azido-PEG4-amine (11.77 mg, 0.045 mmol, 1 equiv) was added to 1 (16 mg, 0.045 mmol, 1 equiv) in 1.6 mL THF, followed by the addition of 0.4 ml of water containing CuSO4·5H2O (5.60 mg, 0.0225 mmol, 0.5 equiv) and sodium ascorbate (8.89 mg, 0.045 mmol, 1 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under argon for 16 h. The solution was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by preparative HPLC to afford 2 which was used directly in the next step. Compound 2 (7.05 mg, 0.0114 mmol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in 0.8 ml DMF and then DIPEA (5.93 μL, 0.0343 mmol, 3 equiv) was added. N-Succinimidyl 4-(N-Maleimidomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxylate (3.83 mg, 0.0114 mmol, 1 equiv) was then added to the ice-cooled reaction mixture. The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min and then warmed to room temperature. After stirring at room temperature under argon for 16 h, the reaction mixture was purified by preparative HPLC to afford TLHE (3) (7.38 mg, 20% yield over 2 steps). (>95% purity by HPLC): tR (column) (C18) = 21.4 min; tR (C4) = 12.1 min; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.13 (d, 2H, J = 13.7 Hz), 6.79 (s, 2H), 6.69 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 4.55 (t, 2H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.04 (t, 2H, J = 6.2 Hz), 3.98 (t, 2H, J = 5.8 Hz), 3.88–3.87 (m, 2H), 3.60–3.55 (m, 14H), 3.49 (t, 2H, J = 5.5 Hz), 3.31–3.30 (m, 2H), 2.91 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 2.70 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.32 (s, 6H), 2.18–2.09 (m, 3H), 2.02–1.98 (m, 2H), 1.80–1.60 (m, 5H), 1.43–1.36 (m, 2H), 1.04–0.94 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz) δ 179.08, 172.95, 169.39, 148.12, 144.98, 135.40, 134.13, 124.46, 118.62, 109.19, 109.08, 107.20, 71.71, 71.64, 71.42, 70.70, 70.58, 68.40, 67.87, 51.54, 46.21, 44.66, 40.39, 38.04, 31.13, 30.21, 30.17, 30.06, 23.00, 19.55, 9.92. HRMS (DART) m/z: calcd for C42H59N7O11 [M + H] + 838.4351; Found 838.4369.

Preparative HPLC Method for Purification of TLHE (3).

The preparative HPLC was carried out in a Waters Delta 600 HPLC system connected to a photodiode array detector operating between the UV ranges of 210 – 600 nm with Waters Masslynx V4.1 software. The sample injection loop was 5 mL. The purification was performed on a Waters Xbridge® prep C18 column (10 X 250 mm, 5μm) with 2 mL/min flow rate. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (95% H2O, 5% MeOH, 0.1% TFA) and solvent B (95% MeOH, 5% H2O, 0.1% TFA). The HPLC gradient started from 0% B to 100% B in 20 min. After staying in 100% B for 5 min, the solvent composition was changed to 0% B in 3 min and maintained at 0% for another 7 min.

Analytical HPLC Method for Evaluating the Purity TLHE (3) and Conjugation Reaction with rIL2.

The analytical HPLC was performed in a Waters e2695 alliance HPLC system connected to a photodiode array detector. For analytical analysis of TLHE (3), Waters XBridge® C18 column (4.6 X 250 mm, 5μm) and Waters Symmetry300™ C4 column (2.1 X 150 mm, 5 μm) were used. The mobile phase was composed of the methanol-water-TFA system as mentioned above. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. HPLC gradient increased linearly from 0% B to 100% B in 20 min. After running isocratically in 100% B for 5 min, the solvent composition went down from 100% B to 0% B in 3 min and stayed in 0% B for another 2 min. The injection volume was 50 μL. For rIL2/TLHE-rIL2, Waters Symmetry300™ C4 column (2.1 X 150 mm, 5 μm) was used. Solvent A (95% H2O, 5% ACN, 0.1% TFA) and solvent B (95% ACN, 5% H2O, 0.1% TFA) was used as mobile phase. The solvent composition started from 0% B to 100% B in 30 min, stayed in 100% for 5 min, then went down to 0% in 3 min. After staying in 100% B for another 2 min, one injection was finished.

Conjugation of TLHE (3) to rIL2.

The thiol-maleimide reaction between TLHE (3) and rIL2 was carried out in 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.5). 6-fold molar excess of TLHE (3) was added to rIL2 in buffer in the presence of 1% DMSO under argon. After 24 h at room temperature, excess TLHE was removed by dialysis. Dialysis was performed with 10 kDa MWCO dialysis cassettes (Thermo Scientific™, catalog No. PI87729) against 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.5) at 4 °C for 72 hours. To make sure that rIL2 does not undergo conformational change or loss in bioactivity, rIL2 was treated in the same 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (without the presence of TLHE) and underwent the same dialysis process. TLHE was also added into 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer to serve as a control to monitor the removal of the unreacted TLHE. The removal of the TLHE was evaluated with the analytical HPLC. In analytical HPLC, no TLHE could be detected (Figure S2). The concentration of the dialyzed protein samples was determined using BCA assay. The samples were stored at −80 °C for further experiment.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis.

The degree of modification of rIL2 using mass spectrometry was monitored with the Bruker UltraFlextreme MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. For the in-gel tryptic digest, proteins samples were first resolved in the SDS-PAGE in the reducing condition. The gel bands were excised, destained, and then subjected to in-gel tryptic digest protocol with reduction and alkylation procedure. The extracted peptide solution was analyzed using the Thermo Fisher Q exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer.

SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE was carried out in 15% handcast polyacrylamide gels (1.5 mm thick). Proteins samples were 2-fold diluted with the 2x Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-rad, catalog No. 1610737). The Laemmli buffer was supplemented with 5% β-mercaptoethanol as a reducing reagent. The samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 mins and loaded for electrophoresis. Protein samples were stacked at 80 V for 15 mins and then resolved at 120 V for 90 mins. Gels were stained with coomassie blue R250, destained and scanned using the LI-COR Odyssey CLx imaging system.

In Silico Modeling Studies.

The silico modeling studies was carried out as previously reported.14,33 The geometry optimization of the TLHE (3) was carried out at the hybrid density functional B3LYP level with 6–31G(d) basis set using Gaussian 09 program package. To confirm the optimized geometry is at minimum, frequency calculations were carried out on the optimized geometries. The docking experiments were carried out using Dock6. The crystal structure of TTR (pdb id: 4HIQ)15 and the heterotrimeric interleukin-2 receptor in complex with interleukin 2 (pdb id: 2ERJ)39 were obtained from RCSB.org. UCSF Chimer program was used to analyze and visualize the proteins and docking complex structures.

Evaluation of Binding Affinity of Test Compounds to TTR in Buffer.

The binding affinity of TLHE, rIL2, and TLHE-rIL2 to TTR was determined by their ability to displace FP probe from TTR using previously reported fluorescence polarization (FP) assay.35 The FP assay was carried out in 384-well plates (E&K Scientific, catalog No. EK-31076) in a 25 μL reaction volume. Serial dilutions of test compounds (0.024 μM to 55 μM) were added into the assay buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 0.01% Triton-X100) containing FP-probe (50 nM) and TTR (300 nM). The samples were equilibrated by agitation on a plate shaker for 20 min at room temperature. Fluorescence polarization (excitation λ 485 nm, emission λ 525 nm, Cutoff λ 515 nm) measurements were taken using a SpectraMax M5Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). The IC50 values were obtained by fitting the data to the following equation [y = (A – D)/(1 + (x/C)B) + D], where A is the maximum FP signal, B is the slope factor, C is the inflection point (IC50), and D is the minimum FP signal. The binding constant (Kd) values were calculated using the Cheng–Prusoff equation from the IC50 values. All reported data represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

Evaluation of Binding Affinity and Selectivity of Test Compounds to TTR in Human Serum.

The binding affinity and selectivity of test compounds to TTR were determined by their ability to compete with the binding of a fluorescent probe exclusion (FPE probe) binding to TTR in human serum as previously reported.36,37 The assay was carried out in a 120 μL reaction volume. 20 μL of rIL2 or TLHE-rIL2 were added to a 100 μL human serum containing FPE probe (3.6 μM final concentration in serum). AG10 and tafamidis were used as positive controls. The final concentration of all test compounds in serum was 10 μM. The fluorescence changes (λex = 328 nm and λem = 384 nm) were monitored every 15 min using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader for 6 h at 25 °C.

CTLL-2 Cell Proliferation Assay.

CTLL-2 cells (ATCC® TIB-214™) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The cell line was maintained in RPMI-1640 Medium (ATCC® 30-2001™) supplemented with 10% FBS (Fisher Scientific, catalog No. SH3039603), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Fisher Scientific, catalog No. 15-140-122), and 2 ng/mL human IL2 (aldesleukin) (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog No. SRP3085). Before the cell proliferation assay, the cells were spun down to remove the medium containing 2 ng/mL aldesleukin and then seeded in 96 well plates at a density of 6000 cells per well in 100 μL culture medium with serial dilutions of stimulants (aldesleukin/rIL-2/TLHE-rIL2). The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. Then 10 μL of WST-1 reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog No. CELLPRO-RO) was added into each well. After incubation for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the absorbance at 450 and 655 nm was measured with the microplate reader (BioTek). The nonlinear regression analysis was performed in the GraphPad Prism 8. The maximal effective concentration (EC50) was obtained by fitting the data into the dose-response stimulation model: [Agonist] vs response--Variable slop.

Evaluation of Pharmacokinetic Profile of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 in Rats.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats with jugular vein cannulation surgery (body weight: 201–225 g) were purchased from Charles River. Each rat was dosed intravenously (IV via jugular vein catheter) with rIL2 or TLHE-rIL2 (0.8 mg/kg in 200 μL ammonium acetate buffer), followed by injection of 200 μL sterile saline. Blood samples were taken from the catheter using heparin rinsed syringe at the following time points (2 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h and 24 h). The plasma sample was obtained by centrifuging the blood at 1500 g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The plasma concentration of rIL-2/TLHE-rIL2 was determined using commercially available sandwich-type ELISA kit (Fisher Scientific, catalog No. ENEH2IL22) following the manufacture’s protocol. Five-fold diluted plasma (20% plasma) was first prepared by adding 500 μL blank rat plasma with 2000 μL of the standard diluent the ELISA kit provided. Serial dilutions of rIL2 or TLHE-rIL2 were then spiked into the diluted plasma to prepare two standard curves. Plasma samples from the pharmacokinetic study were diluted five-fold with the standard diluent and then then 50 μL each diluted plasma sample was added into each well of the antibody coated ELISA plate for the assay. If the determined plasma concentration was above the standard curves, the plasma sample would be first diluted with the blank rat plasma, and then follow the same procedure as mentioned above.

The calculated concentrations were plotted against time in a semi-logarithmic scale. Data sets from individual rats was analyzed by noncompartmental analysis (NCA) with Phoenix WinNonlin software to calculate the pharmacokinetic parameters. The time points used to calculate the Lambda Z was determined automatically by Phenix WinNonlin with a build in best fit method. Lambda Z is the negative slop of these determined time points. Half-life (t1/2) was calculated with the equation: t1/2 = 0.693/Lambda Z. Area Under Curve (AUC) and area under the first moment curve (AUMC) was calculated using the trapezoid method. The mean residence time (MRT) was calculated using the equation: MRT = AUMC/AUC.

Evaluation of Ex Vivo Efficacy of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 in CTLL-2 cells.

The 2 min, 8 h and 24 h plasma samples from the pharmacokinetic study were evaluated ex vivo (in cell culture) for their efficacy to promote CTLL-2 proliferation. Cells treated with blank rat plasma were used as negative controls. 6700 cells per well in 90 μL RPMI-1640 Medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin was first seeded into the 96 well plate. The 2 min plasma sample was first diluted 2- times with the blank rat plasma, and then 10 μL plasma was added into the cells. For the 8 h and 24 h samples, 10 μL samples were added directly into the cells. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. And then cell viability was determined with the WST-1 reagent as described in the experimental procedure of CTLL-2 cell proliferation assay.

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad PRISM 8 software. The significance of the differences was measured by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (ns, not significant; ∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the US National Institutes of Health Grant No. 1R15GM129676-01 (M.M.A.). The support by a National Science Foundation Instrumentation grant (NSF-MRI-0722654) is gratefully acknowledged. Thanks to Andreas Franz, Vyacheslav Samoshin, and Jianhua Ren for NMR and mass spectrometric analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- PEGylation

conjugation to polyethylene glycol

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- TLHE

transthyretin ligands for half-life extension

- TTR

transthyretin

- RBP

retinol binding protein

- IL2

interleukin 2

- rIL2

recombinant interleukin 2

- 6His

Hexa-histidine

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

- FP

fluorescence polarization

- FPE

fluorescent probe exclusion

- MRT

mean residence time

- AUC

Area under the curve

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at:

cDNA sequence used to generate rIL2 in E. coli; HPLC traces for TLHE, rIL2 and rIL2 + TLHE conjugation reaction before and after dialysis; Evaluation of the bioactivity of aldesleukin in CTLL-2 cell proliferation assay; Calibration curves of rIL2 and TLHE-rIL2 using the commercial IL2 ELISA kit; Purity of TLHE (3) evaluated by HPLC using C18 and C4 reversed phase columns.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Fang Liu, Department of Pharmaceutics and Medicinal Chemistry, Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California 95211, United States.

Toufiq Ul Amin, Department of Pharmaceutics and Medicinal Chemistry, Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California 95211, United States.

Dengpan Liang, Department of Pharmaceutics and Medicinal Chemistry, Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California 95211, United States.

Miki S. Park, Department of Pharmaceutics and Medicinal Chemistry, Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California 95211, United States

Mamoun M. Alhamadsheh, Department of Pharmaceutics and Medicinal Chemistry, Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California 95211, United States.

REFERENCE

- (1).Walsh G Biopharmaceutical Benchmarks 2014. Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32 (10), 992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Murray JE; Laurieri N; Delgoda R Chapter 24. Proteins. In Pharmacognosy Fundamentals, Applications and Strategies; 2017; pp 477–494. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Leader B; Baca QJ; Golan DE Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2008, 7 (1), 21–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jumper J; Evans R; Pritzel A; Green T; Figurnov M; Olaf Ronneberger O; unyasuvunakool K; Bates R; Žídek A; Potapenko A; Bridgland A; Meyer C; Kohl A; Ballard A; Cowie A; Romera-Paredes B; Nikolov S; Jain R; Adler J; Back T; Petersen S; Reiman D; Clancy E; Zielinski M; Steinegger M; Pacholska M; Berghammer T; Bodenstein S; Silver D; Vinyals O; Senior A; Kavukcuoglu K; Kohli P; Hassabis D Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596 (7873) 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zaman R; Islam RA; Ibnat N; Othman I; Zaini A; Lee CY; Chowdhury EH Current Strategies in Extending Half-Lives of Therapeutic Proteins. J. Control. Release 2019, 301, 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Werle M; Bernkop-Schnürch A Strategies to Improve Plasma Half Life Time of Peptide and Protein Drugs. Amino Acids 2006, 30 (4), 351–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kontermann RE Half-Life Extended Biotherapeutics. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 2016, 16 (7), 903–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).AlQahtani AD; O’Connor D; Domling A; Goda SK Strategies for the Production of Long-Acting Therapeutics and Efficient Drug Delivery for Cancer Treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother 2019, 113, 108750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pelegri-O’day EM; Lin EW; Maynard HD Therapeutic Protein-Polymer Conjugates: Advancing beyond Pegylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (41), 14323–14332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).van Witteloostuijn SB; Pedersen SL; Jensen KJ Half-Life Extension of Biopharmaceuticals Using Chemical Methods: Alternatives to PEGylation. ChemMedChem 2016, 11 (22), 2474–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dozier JK; Distefano MD Site-Specific Pegylation of Therapeutic Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2015, 16 (10), 25831–25864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Qi Y; Chilkoti A Protein-Polymer Conjugation-Moving beyond PEGylation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 28, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Armstrong JK The Occurrence, Induction, Specificity and Potential Effect of Antibodies against Poly(Ethylene Glycol). In PEGylated Protein Drugs: Basic Science and Clinical Applications; 2009; pp 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Penchala SC; Miller MR; Pal A; Dong J; Madadi NR; Xie J; Joo H; Tsai J; Batoon P; Samoshin V; Franz A; Cox T; Miles J; Chan WK; Park MS; Alhamadsheh MM A Biomimetic Approach for Enhancing the in Vivo Half-Life of Peptides. Nat. Chem. Biol 2015, 11 (10), 793–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Penchala SC; Connelly S; Wang Y; Park MS; Zhao L; Baranczak A; Rappley I; Vogel H; Liedtke M; Witteles RM; Powers ET; Reixach N; Chan WK; Wilson IA; Kelly JW; Graef IA; Alhamadsheh MM AG10 Inhibits Amyloidogenesis and Cellular Toxicity of the Familial Amyloid Cardiomyopathy-Associated V122I Transthyretin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110 (24), 9992–9997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ingenbleek Y; Young V Transthyretin (Prealbumin) in Health and Disease: Nutritional Implications. Annu. Rev. Nutr 1994, 14 (1), 495–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Berraondo P; Sanmamed MF; Ochoa MC; Etxeberria I; Aznar MA; Pérez-Gracia JL; Rodríguez-Ruiz ME; Ponz-Sarvise M; Castañón E; Melero I Cytokines in Clinical Cancer Immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120 (1), 6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Vazquez-Lombardi R; Roome B; Christ D Molecular Engineering of Therapeutic Cytokines. Antibodies 2013, 2 (3), 426–451. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Pires IS; Hammond PT; Irvine DJ Engineering Strategies for Immunomodulatory Cytokine Therapies: Challenges and Clinical Progress. Adv. Ther 2021, 2100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Milla P; Dosio F; Cattel L PEGylation of Proteins and Liposomes: A Powerful and Flexible Strategy to Improve the Drug Delivery. Curr. Drug Metab 2012, 13 (1), 105–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Georgiev K; Georgieva M Pharmacological Properties of Monoclonal Antibodies Directed Against Interleukins. In Immunopathology and Immunomodulation; 2015; pp 261–286. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Anderson PM; Sorenson MA Effects of Route and Formulation on Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Interleukin-2. Clin. Pharmacokinet 1994, 27 (1), 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ohnishi H; Lin KM; Chu TM Prolongation of Serum Half-Life of Interleukin 2 and Augmentation of Lymphokine-Activated Killer Cell Activity by Pepstatin in Mice. Cancer Res. 1990, 50 (4), 1107–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rosenberg SA IL-2: The First Effective Immunotherapy for Human Cancer. J. Immunol 2014, 192 (12), 5451–5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Klatzmann D; Abbas AK The Promise of Low-Dose Interleukin-2 Therapy for Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2015, 15 (5), 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Dutcher JP; Schwartzentruber DJ; Kaufman HL; Agarwala SS; Tarhini AA; Lowder JN; Atkins MB High Dose Interleukin-2 (Aldesleukin) - Expert Consensus on Best Management Practices-2014. J. Immunother. Cancer 2014, 2 (1), 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Charych DH; Hoch U; Langowski JL; Lee SR; Addepalli MK; Kirk PB; Sheng D; Liu X; Sims PW; VanderVeen LA; Ali CF; Chang TK; Konakova M; Pena RL; Kanhere RS; Kirksey YM; Ji C; Wang Y; Huang J; Sweeney TD; Kantak SS; Doberstein SK NKTR-214, an Engineered Cytokine with Biased IL2 Receptor Binding, Increased Tumor Exposure, and Marked Efficacy in Mouse Tumor Models. Clin. Cancer Res 2016, 22 (3), 680–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Katre NV Immunogenicity of Recombinant IL-2 Modified by Covalent Attachment of Polyethylene Glycol. J. Immunol 1990, 144 (1), 209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Knauf MJ; Bell DP; Hirtzer P; Luo Z-P; Young JD; Katre NV Relationship of Effective Molecular Size to Systemic Clearance in Rats of Recombinant Interleukin-2 Chemically Modified with Water-Soluble Polymers. J. Biol. Chem 1988, 263 (29), 15064–15070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Yang JC; Topalian SL; Schwartzentruber DJ; Parkinson DR; Marincola FM; Weber JS; Seipp CA; White DE; Rosenberg SA The Use of Polyethylene Glycol‐modified Interleukin‐2 (PEG‐IL‐2) in the Treatment of Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma and Melanoma. Cancer 1995, 76 (4), 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Yamada T; Fujishima A; Kawahara K; Kato K; Nishimura O Importance of Disulfide Linkage for Constructing the Biologically Active Human Interleukin-2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1987, 257 (1), 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Goodson RJ; Katre NV Site-Directed PEGylation of Recombinant Interleukin-2 at Its Glycosylation Site. Nat. Biotechnol 1990, 8 (4), 343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pal A; Albusairi W; Liu F; Tuhin MTH; Miller M; Liang D; Joo H; Amin TU; Wilson EA; Faridi JS; Park M; Alhamadsheh MM Hydrophilic Small Molecules That Harness Transthyretin to Enhance the Safety and Efficacy of Targeted Chemotherapeutic Agents. Mol. Pharm 2019, 16 (7), 3237–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Miller M; Pal A; Albusairi W; Joo H; Pappas B; Haque Tuhin MT; Liang D; Jampala R; Liu F; Khan J; Faaij M; Park M; Chan W; Graef I; Zamboni R; Kumar N; Fox J; Sinha U; Alhamadsheh M Enthalpy-Driven Stabilization of Transthyretin by AG10 Mimics a Naturally Occurring Genetic Variant That Protects from Transthyretin Amyloidosis. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61 (17), 7862–7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Alhamadsheh MM; Connelly S; Cho A; Reixach N; Powers ET; Pan DW; Wilson IA; Kelly JW; Graef IA Familial Cardiac Amyloidosis: Potent Kinetic Stabilizers That Prevent Transthyretin-Mediated Cardiomyocyte Proteotoxicity. Sci. Transl. Med 2011, 3 (97), 97ra81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Choi S; Connelly S; Reixach N; Wilson IA; Kelly JW Chemoselective Small Molecules That Covalently Modify One Lysine in a Non-Enzyme Protein in Plasma. Nat. Chem. Biol 2010, 6 (2), 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Choi S; Kelly JW A Competition Assay to Identify Amyloidogenesis Inhibitors by Monitoring the Fluorescence Emitted by the Covalent Attachment of a Stilbene Derivative to Transthyretin. Bioorganic Med. Chem 2011, 19 (4), 1505–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Qian M; Zhang Q; Lu J; Zhang J; Wang Y; Shangguan W; Feng M; Feng J Long-acting human Interleukin 2 bioconjugate modified with fatty acids by sortase A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32 (3), 615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Stauber DJ; Debler EW; Horton PA; Smith KA; Wilson IA Crystal Structure of the IL-2 Signaling Complex: Paradigm for a Heterotrimeric Cytokine Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103 (8), 2788–2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.