Abstract

Objectives

Telemedicine and telehealth are increasingly used in nursing homes (NHs). Their use was accelerated further by the COVID-19 pandemic, but their impact on patients and outcomes has not been adequately investigated. These technologies offer promising avenues to detect clinical deterioration early, increasing clinician's ability to treat patients in place. A review of literature was executed to further explore the modalities' ability to maximize access to specialty care, modernize care models, and improve patient outcomes.

Design

Whittemore and Knafl's integrative review methodology was used to analyze quantitative and qualitative studies.

Setting and Participants

Primary research conducted in NH settings or focused on NH residents was included. Participants included clinicians, NH residents, subacute patients, and families.

Methods

PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, Embase, PsycNET, and JSTOR were searched, yielding 16 studies exploring telemedicine and telehealth in NH settings between 2014 and 2020.

Results

Measurable impacts such as reduced emergency and hospital admissions, financial savings, reduced physical restraints, and improved vital signs were found along with process improvements, such as expedient access to specialists. Clinician, resident, and family perspectives were also discovered to be roundly positive. Studies showed wide methodologic heterogeneity and low generalizability owing to small sample sizes and incomplete study designs.

Conclusions and Implications

Preliminary evidence was found to support geriatrician, psychiatric, and palliative care consults through telemedicine. Financial and clinical incentives such as Medicare savings and reduced admissions to hospitals were also supported. NHs are met with increased challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which telemedicine and telehealth may help to mitigate. Additional research is needed to explore resident and family opinions of telemedicine and telehealth use in nursing homes, as well as remote monitoring costs and workflow changes incurred with its use.

Keywords: Telemedicine, telehealth, remote monitoring, nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities

Globally, the number of adults aged 85 years and older is projected to increase 351% between 2010 and 2050.1 As the population ages, the need for specialized facility and home-based care will increase.2 Even today, nursing homes (NHs) struggle with staff shortages and access to specialty care expertise, while simultaneously facing increased pressures to reduce avoidable hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) visits.3 , 4

Health technology is frequently championed as a modality to improve care delivery in order to meet the demands of providing complex care in the setting of limited internal resources. The United States Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) defines telehealth as the use of videoconferencing, remote patient monitoring (RPM), store-and-forward technologies (eg, sending wound images for evaluation), and mobile health (mHealth) applications.4 , 5 The term telemedicine refers to the use of live synchronized videoconferencing, allowing for interactive video communications between a provider and a patient.6

Telehealth and telemedicine are a potential tool for scaling caregiving capacity and business efficiency for NHs. In the United States, 39% of NHs currently use some form of telehealth or telemedicine,3 whereas 76% of acute care hospitals use telemedicine and telehealth.7 The use of these technologies has become even more salient recently as NHs have been in the spotlight as a result of the emergence of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). NH residents are among the most at-risk groups for COVID-19 fatality.8 This combined with stringent infection control practices such as lockdowns, and other concerns such as staffing and availability of specialty care, presents an even greater impetus for exploring telemedicine and telehealth as modalities in the NH setting.9 One recent approach to COVID-19 used telemedicine and remote monitoring to treat residents in place, resulting in lower hospitalizations and mortality compared with other NHs.10 Moreover, there have been increasing calls to focus research on the use of technology to enhance care in NHs and other settings from the National Institutes of Health, the IMPACT Collaboratory, Health Resources and Services Administration, and others both previous to and in response to the pandemic.11, 12, 13, 14 Therefore, it is important to synthesize the most recent literature to provide groundwork for the future design, implementation, and expansion of telehealth services in NHs.

Previous systematic reviews have explored the use of technology in the care of older adults with chronic conditions, persons living with dementia in supportive environments, ambulatory care, and in long-term care settings.15, 16, 17, 18 Another international review focused on assistive technology, alarms, and surveillance technology.16 Outcomes in the reviews were generally positive, though most call for further research. Overall, a gap was found in published reviews of NH telemedicine and technology studies from 2014 to 2020. Given the pace of technology development, a re-evaluation of the current evidence is needed.

The purpose of this integrative review is therefore to evaluate and appraise the outcomes of recent primary research involving telemedicine and telehealth in NHs. This integrative review adds to the knowledge base by evaluating and synthesizing recent studies and will conclude with recommendations for practice and future research.

Methods

Whittemore and Knafl's19 methodology was used as the framework for this integrative review. Studies capturing clinician, patient, and family feedback on the technology's usability and user experience were analyzed within the context of the Technology Acceptance Model.20

Search Strategy

Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Excerpta Medica Database (Embase), PsycNET, and the Journal Storage (JSTOR) were searched for relevant articles. A medical librarian was consulted for the search strategy. A combination of the terms remote patient monitoring, telehealth, telecare, telemonitoring, telemedicine, videoconferencing, skilled nursing facilit∗, SNF, long-term care, LTC, and nursing home were searched using Boolean logic in these databases. In PubMed, the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms Skilled Nursing Facilities, Nursing Homes, and Telemedicine were used, including their automatic explosion functionality to include a larger array of articles. CINAHL major headings Nursing Homes+ and Telehealth+, as well as Embase subject terms exp telehealth/and ∗nursing home found additional articles.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search included studies in the English language published from January 2014 through October 2020. Because of limited results specific to the United States, international studies were included. Primary quantitative and qualitative studies using telemedicine and telehealth were included. Studies were required to involve NH clinicians or NHs as the primary setting. Exclusion criteria omitted conference abstracts, magazine articles, and protocol proposals. Patient-facing mHealth applications (ie, no direct interactions with clinicians) were excluded.

Search Results

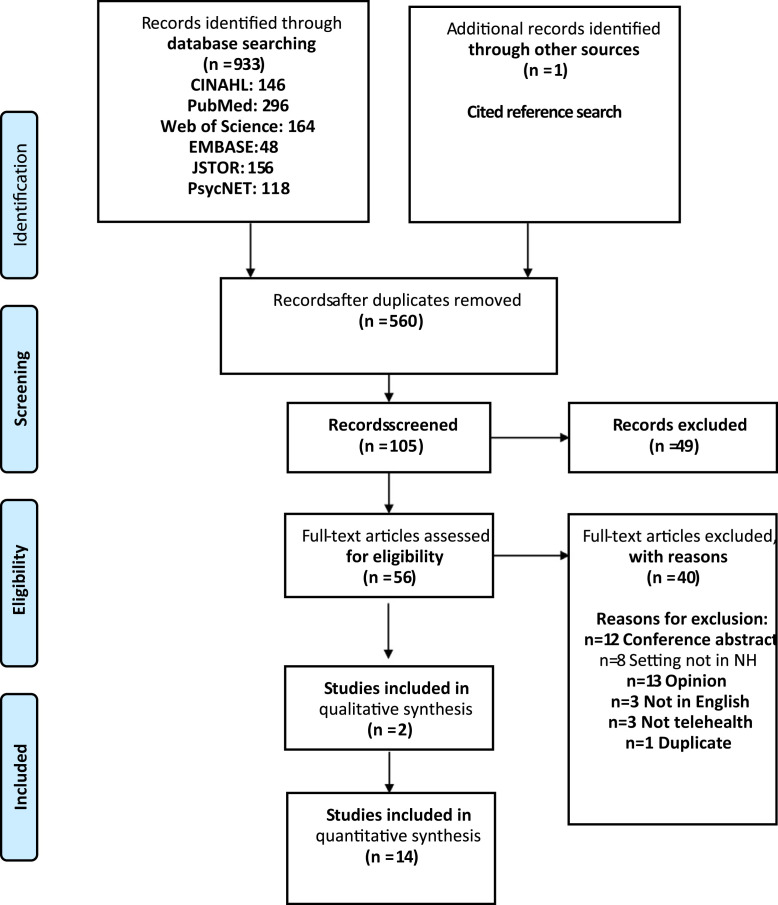

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram is shown in Figure 1 .21 A total of 933 results were screened by study title. Fifty-six were included for full-text review. A final sample of 16 articles meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria were kept for data extraction and evaluation. A Cochrane Systematic Review of telemedicine's effects on health outcomes was referenced but only included studies published before 2013.6

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

From Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Data Evaluation

The final sample of 16 empirical studies in this integrative review included randomized controlled trials (n = 3), nonrandomized experimental studies (n = 4), cohort studies (n = 2), cross-sectional studies (n = 3), mixed methods (n = 2), and qualitative studies (n = 2). Joanna Briggs Institute Checklists aided evaluation of the rigor of experimental and cross-sectional studies (Supplementary Table 1).22 The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist was used to appraise the qualitative studies (Supplementary Table 2).23 Appraisal of a quality improvement study was completed with the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence tool.

Data Analysis

A constant comparative method was undertaken to discover patterns, themes, variations, and relationships.19 Table 1 summarizes extracted data by purpose, study design, technology used, and main findings. Because of the variety present in the research studies, a table organizing studies by focus, intervention details, roles involved, and demographics was used to discover common elements (see Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Study Summary

| Lead Author | Purpose | Study Design | Sample and Strategy | Data Collection | Technology Used | Statistical Analysis | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telemedicine Consults | |||||||

| Cheng et al, 202024 |

|

Descriptive cross-sectional study | N = 32 consults

|

Telemedicine Satisfaction Scale (TeSS) Telemedicine Usability Questionnaire (TUQ) |

Video sessions |

|

Reporting percentages of survey results only

|

| Driessen et al, 201825 |

|

Cross-sectional survey | N = 524 physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs) Convenience sample. Survey made available to all attendees of AMDA Long-Term Care Medicine and Annual Care Conference. 41% response rate |

Author-developed paper survey measuring likelihood of ordering telemedicine consults for 26 medical specialties. Likelihood ordering ancillary services and nonmedical specialties. Responses related to perceived benefits and concerns. Participant demographics |

N/A |

|

Most likely to use telemedicine for dermatology consults and geriatric psychiatry. Infectious disease, cardiology, and neurology were the next most likely to be requested through telemedicine High level of agreement that subspecialty telemedicine may fill existing service gaps and access to and improve timeliness of care Authors report enthusiasm for telemedicine but “few respondents actually had access to telemedicine in their facilities.” In introduction, quoted to be 40%. Majority of respondents were medical directors |

| Georgeton et al, 201526 |

|

Prospective cohort study | N = 69 Included patients had received a geriatric teleconsultation and resided at one of 3 NHs |

Histories, demographics, and reason for consult Geriatrician's assessment data and recommendations recorded CIRS-G, BMI, ADL, GDS, NPI, history of falls |

Dedicated teleconsult room in NH High-definition camera Computer with broadband Internet |

|

83% of teleconsults were for neuropsychological reasons. GPs followed recommendations for 58 teleconsults (84%). 86% of patients received pharmacologic recommendations, 78% received nonpharmacologic recommendations, and 7% received expert medical advice (eg, hospitalization, referral to specialist recommendations) Expert medical advice was associated with GP adherence to recommendations (OR = 7.71, 95% CI 1.57-37.98, P = .04) Risk of depressive syndrome (OR = 8.00, 95% CI 1.10-58.10, P = .004) and expert medical advice recommendation (OR = 17.97, 95% CI 1.10-58.10, P = .04) were associated with GP adherence to recommendations Lack of adherence to teleconsult recommendations is a serious potential barrier to effectiveness of telemedicine programs. |

| Gordon et al, 201627 |

|

2:1 prospective matched cohort study | N = 11 NHs in Massachusetts and Maine. Each ECHO-AGE SNF matched with 2 other similar facilities based on size. 115 cases discussed during study period |

Minimum Data Set (MDS) outcomes:

|

Video consult |

|

ECHO-AGE residents were 75% less likely to be physically restrained than in control facility (OR = 0.25, P = .05). ECHO-AGE residents were 17% less likely to receive antipsychotic medications than in control facilities (OR = 0.73, P = .07) ECHO-AGE residents were 23% less likely to experience UTI during follow up period (OR = 0.77, P = .01) Preliminary evidence shows reduction in primary outcomes (physical and chemical restraint usage). Both changed most dramatically between baseline and the first quarter after the intervention's initiation. Antipsychotic use continued to gradually decline throughout the remaining quarters, whereas physical restraints remained lower overall but fluctuated quarter to quarter. |

| Helmer-Smith et al, 202028 |

|

Mixed Methods | N = 64 eConsults requested from

|

Specialty consulted and response time Specialist billing time PCP responses on mandatory close-out survey Focus groups |

Asynchronous communication between NH providers and specialists |

|

23 specialties contacted: Dermatology (19%), geriatric medicine (11%), infectious disease (9%) Specialists responded in median of 0.6 days with a median billing time of 15 minutes (Can$50/case) Consult results: 60% new course of action, 31% no change. 70% were resolved without face-to-face visit, and 2% initiated new referrals. Perceived value: improved access, cost reductions, enhanced quality of care, reduce transfers, shorter wait periods. |

| Hofmeyer et al, 201629 |

|

Quality improvement pilot study | 736 two-way video consultations (they don't count this in participants) 863 telephonic encounters |

Utilization of eLTC services Averted transfers as a percentage of total encounters Quality improvement staff surveys |

Video consult 2-way stethoscope High-definition camera |

|

500 potential transfers deemed unnecessary

Clinician buy-in achieved with after-hours eLTC support Chief complaints: 24% shortness of breath, 24% skin complaint, 14% upper respiratory infection, 13% fever, 12% neurologic, 10% joint pain, 10% GI complaint, 10% urologic Highest proportions of CC transfers: 66% of neurologic transferred, 45% GI, 44% shortness of breath |

| Low et al, 202030 |

|

Descriptive cross-sectional study | N = 1673 consults with 850 unique patients (95% scheduled, 5% ad hoc) All NH patients referred for teleconsult from December 2010 to May 2017 |

Resident assessment form categorize patients by functional status Data from health record |

Video sessions |

|

Reason for consult: 27% medication review, 15% behavioral, 15% symptom review, 13% follow-up review Session length: 20-129 min Outcomes: A month after teleconsult, 84% remained in NH, 3.4% passed away, 6.3% referred to outpatient specialist, and 6.2% sent to ED |

| Perri et al, 202014 |

|

Pre-post nonrandomized experimental study | N = 61 residents at 2 pilot facilities Convenience sample that included all residents at the facilities 11 palliative care video consults |

Demographics PPS CHESS ADL Surveys for patient and family experience Clinical staff survey on confidence in palliative care, and video satisfaction surveys. |

Video consult Dedicated room for video consult Widescreen monitor, video camera, external microphone |

|

55% of the telemedicine conferences were triggered by quarterly review screening. Next most common triggers were 27% clinical judgement and 18% readmission from acute care 11 families joined by videoconference:

|

| Piau et al, 202031 |

|

Qualitative | N = 10 NHs using geriatrician telemedicine consults for 2 y

|

Semistructured interviews | Video sessions |

|

Improvements seen in greater involvement of staff in managing neuropsychiatric symptoms, greater involvement of families, and promotion of nonpharmacologic treatments Staff felt telemedicine improves the quality of care; barriers include providers not accepting specialist's advice and lack of time and workforce for telemedicine visits |

| Stern et al, 201432 |

|

Pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial | N = 137 SNF residents with PU | Digital wound photography Visual analog scale (VAS)–pain EQ5D (QOL) VAS-pain Rates of hospitalization and ED visits Ethnographic observations and in-depth interviews with NH staff |

Stage II or greater pressure ulcers |

|

No difference in rate of healing with and without the EMDT telemedicine intervention Telemedicine-delivered EMDTs found to be cost-effective. Results similar to usual care but less expensive to deliver In-person nurse practitioner visits were preferred by NH staff Concluded that strengthening primary care within the NH is more advantageous than using a multidisciplinary specialty wound care team Qualitative: Inadequate staff time allocated for study implementation; unavailable wound care supplies; frequent staff turnover was prohibitory |

| After-hours support and remote assessments | |||||||

| Grabowski and O’Malley, 201433 |

|

Randomized controlled trial with pre-post design | Treatment group = 6 NHs Control group = 5 NHs |

NH EHR: transfers, demographics, resident days Monthly data from telemedicine provider CMS NH's 5-star rating, number of beds |

Not specified |

|

Did not observe statistically significant difference between telemedicine intervention group and usual care. When intervention NHs were classified into high-engagement and low-engagement with telemedicine, the authors found a significant decrease. An SNF with 180 hospitalizations per year could see a decrease by 15.1 hospitalizations per year (8.4%). Average savings to Medicare that were more engaged with telemedicine intervention were $151,000 per NH per year. |

| Stephens et al, 202034 |

|

Exploratory qualitative – grounded theory | N = 8 focus groups with an average of 5 participants Purposive sampling to construct groups of NH nurses. After themes arose, focus groups then convened with providers, families, and other stakeholders together. |

Focus groups | N/A |

|

Focus group results support that telehealth would be useful in NHs to aid communication between family members and staff to avert avoidable ED transfers when care could be provided in the NH environment. |

| Remote monitoring | |||||||

| Dadosky et al, 201835 |

|

Prospective nonrandomized trial | Convenience sample – patients screened on admission Intervention group: n = 49 Historical comparison group: n = 92 |

Patient satisfaction questionnaire Self-care knowledge questionnaire Number or type of video conferences Number of on-site visits by SNF provider Number of patient transports Number of provider office visits Length of stay from hospital and NH EHR |

Video sessions Chest patch (HR, RR, body position, single-lead ECG) BP cuff, weight scale, pulse-oximeter Cloud-based clinician dashboard Bluetooth stethoscope i-STAT labs (BNP, Chem 8+/BMP) Tablet with video camera |

|

17.39% of case group rehospitalized within 30 days post discharge in comparison with 23.9% of control group Telemedicine group had 6.51% absolute risk reduction and 27.24% relative risk reduction 70% of patients felt telehealth intervention was “good”; 30% rated as “excellent” Time to intervention for medication adjustment significantly reduced (clinically significant but not statistically significant due to sample size):

New diagnoses of atrial fibrillation and pneumonia through video session assessment, ECG, and stethoscope |

| De Vito et al, 202036 |

|

Mixed methods | n = 18 residents n = 6 caregivers |

Bristol ADL NPI-Q QoL-AD QUALIDEM Activity monitor Outcomes tracked: Falls, hospitalizations, medication changes, behavioral episodes Caregiver interviews |

Fitbit activity monitor Video sessions |

|

88% daytime adherence to wearing activity monitor across 6 mo; poor adherence at night. >90% adherence to monthly telemedicine intervention; 92% of medical wellness goals, 89% of behavioral goals, and 82% of cognitive goals were met. Caregivers liked the ability to check the resident's heart rate and step counts; could encourage exercise if they noted a low step count. Residents liked to compare the number of steps they took. Additional time of 5 min per patient required to clean and charge the devices. |

| De Luca et al, 201637 | Develop telehealth care model and evaluate its effectiveness. Include multiparametric vital sign monitoring and teleconsulting for neurologic and psychological conditions | Randomized controlled trial | N = 59 residents Randomly divided into 2 groups in order of recruiting: tele-dementia care vs standard care |

MMSE ADL IADL GDS BPRS BANSS EuroQoL VAS |

PC with webcam and microphone Bluetooth pulse-oximeter, BP cuff, ECG Bluetooth stethoscope audio files |

|

Experimental group

Telemedicine may improve individual's neurobehavioral symptoms and quality of life Presence of telehealth care professional may help local nurses and caregivers manage clinical symptoms and vital signs |

| Yu et al, 201438 |

|

Nonrandomized quasi-experimental field design | N = 32 SNF residents | ACFI Sensor recorded time onset of urinating event for 72-h period per patient Staff manually entered toileting events, time continence aid was changed, whether successful in voiding in toilet, weight of pad, and fluid intake Care plan adherence measures |

Sensor placed in continence aid Clinical dashboard |

|

Incontinence void was lower in the post implementation group (P = .015) Baseline (preintervention) only 44% compliance with prescribed toilet visits. After the intervention, compliance with care plan was 106% (P = .033) because of some patients being offered trips to toilet more than ordered Fewer prescribed toilet visits after implementation (P = .015) More frequent actual toilet visits (P ≤ .001) Increased number of successful toilet visits (P = .011) |

ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACFI, Aged Care Funding Instrument; ADL, activities of daily living; AMDA, American Medical Directors Association; APPs, advanced practice providers; BANSS, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity; BMI, body mass index; BMP, basic metabolic panel; BNP-B, type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CC, critical care; CHESS, Changes in Health, End-stage disease, Signs and Symptoms scale; CIRS-G, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECHO-AGE, Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes; EHR, electronic health record; eLTC, electronic long-term care; GDS, Geriatric Depression Score; GI, gastrointestinal; GP, general practitioner; HR, heart rate; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MSK, musculoskeletal; N/A, not applicable; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; OR, odds ratio; PC, personal computer; PCP, primary care physician; POC, point of care; PPS, Palliative Performance Scale; PU, pressure ulcer/injury; QOL, quality of life; RR, respiratory rate; SNF, skilled nursing facility; UTI, urinary tract infection; VAS, visual analog scale.

Table 2.

Intervention Details

| Study | Focus | Intervention Details | Diagnoses | Roles Involved | Resident Mean Age in Study, y | NH Beds | Setting | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telemedicine Consults | ||||||||

| Cheng et al, 202024 |

|

|

|

|

— | 26 NHs | Rural | Canada |

| Driessen et al, 201825 |

|

|

|

|

— | — | — | United States |

| Georgeton et al, 201526 |

|

|

|

|

86 | 220 beds (across 3 NHs) | — | France |

| Gordon et al, 201627 |

|

|

|

|

— | 16 NHs (min 46, max 335 beds) | — | United States |

| Helmer-Smith et al, 202028 |

|

|

|

|

80 | 3400 beds (across 18 NHs) | — | Canada |

| Hofmeyer et al, 201629 |

|

|

|

|

- | 5000 beds (across 34 NHs) | Rural | United States |

| Low et al, 202030 |

|

|

|

|

77 | 1600 beds (across 8 NHs) | Urban | Singapore |

| Perri et al, 202014 |

|

|

|

|

87 | 472 | Urban | Canada |

| Piau et al, 202031 |

|

|

|

|

— | 10 NHs (min 60, max 133 beds) | — | France |

| Stern et al, 201432 |

|

|

|

|

82 | 1992 beds (across 12 NHs) | - | Canada |

| After-Hours Support and Remote Assessments | ||||||||

| Grabowski and O’Malley, 201433 |

|

|

|

|

- | 11 NHs (min 140, max 175 beds) | - | United States |

| Stephens et al, 202034 |

|

|

|

|

— | — | Urban, suburban, and semirural | United States |

| Remote monitoring | ||||||||

| Dadosky et al, 201835 |

|

|

|

|

81 | — | Suburban | United States |

| De Luca et al, 201637 |

|

|

|

|

80 | — | — | Italy |

| De Vito et al, 202036 |

|

|

|

|

84 | — | — | United States |

| Yu et al, 201438 |

|

|

|

|

81 | 120 | Urban | Australia |

BMP, basic metabolic panel; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; GP, general practitioner; HF, heart failure; HHC, home health care; HR, heart rate; N/A, not available; NP, nurse practitioner; PLWD, person living with dementia; POC, point of care; PU, pressure ulcer/injury; RN, registered nurse; RR, respiratory rate; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Results

The NH settings included locations in Canada, France, Italy, Australia, Singapore, and the United States. NH settings were not reliably described for each study, but those that reported spanned across rural, suburban, and urban settings (Table 2). Studies involved patient, family members, and clinician participants.

Telemedicine and Telehealth Processes

Studies varied in regard to patient populations, technology used, and scheduling of telehealth services. Four studies focused on telemedicine consultations with geriatricians9 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 31; another presented telemedicine services delivered by neurologists and psychologists.37 Palliative care specialists trialed video consultations with patients living with dementia.39 A quality improvement study implemented a telemedicine group practice offering numerous specialists,29 and another implemented asynchronous messages between NH providers and 100 consulting specialty groups.28 The remaining studies enabled access to heart failure, musculoskeletal, and wound care specialists.24 , 32 , 35 Eight studies implemented video capabilities only, whereas 3 studies used Bluetooth stethoscopes for remote auscultation.29 , 35 , 37

The scheduling of telemedicine was varied. In 2 studies, persons living with dementia received weekly37 or monthly36 counseling. Other programs scheduled geriatrician consults individually as needed.26 , 31 Another held biweekly 120-minute case-based teleconsultations where 3 to 4 cases were reviewed between NH providers and specialists at a medical center.27

RPM studies undertook varied approaches. Subacute patients collected their own daily weights, pulse oximetry, heart rate, and blood pressure readings in anticipation of discharging to home with the same wireless equipment.35 The same study deployed multiparameter continuous monitoring patches, point-of-care lab testing, and video visits with heart failure specialists. De Luca et al37 deployed Bluetooth blood pressure cuffs and pulse oximeters to collect vitals 3 times a week, sending data to a remote-monitored dashboard to supplement the monitoring provided within the NH. Another study used sensors to detect urinary incontinence episodes and display data on a telemonitoring application.38 An activity monitor was trialed with persons living with dementia.36

Clinical Outcomes

Patient-level outcomes

Patients experienced improved self-report measures as well as objective improvements in blood pressure and incontinence. In a study combining psychiatric teleconsultations with remote monitoring, persons living with dementia showed improvement in Geriatric Depression Scale, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and quality of life measurements.37 Another study combined telemedicine counseling with activity and heart rate monitoring and found that persons living with dementia achieved 92% of the care management program's wellness goals, 89% of behavioral goals, and 82% of cognitive goals.36 In facilities with access to geropsychiatric specialists via telemedicine, persons living with dementia were 75% less likely to be physically restrained, 17% less likely to be prescribed antipsychotic medications, and 23% less likely to develop a urinary tract infection than similar residents in control facilities.27

Clinically significant results were found in reductions in hospitalizations and improved time to intervention.35 A 10-point decrease in systolic blood pressure (P < .001) and heart rate (P = .02) was found in an RPM intervention group.37 This improvement indicated that telehealth provider collaboration with NH staff improved patient care. In a store-and-forward study, telehealth wound care was found to be noninferior to in-person care in relation to wound healing, while incurring substantial cost benefits.32 Remote monitoring of urinary incontinence showed improved scheduling of toileting assistance with a decrease in incontinence episodes.38

Provider-level outcomes

One study found NH providers to be enthusiastic regarding telemedicine's ability to fill service gaps, and were most likely to use telemedicine for dermatology and geriatric psychiatry consults.40 In another, specialist recommendations were more likely to be followed if residents were at risk for depression [odds ratio (OR) = 8.00, P = .04] and in cases where the geriatrician was providing medical advice such as a decision to transfer to the hospital (OR = 17.97, P = .04).26 There was a trend toward shortened time to new medication orders and new diagnoses of atrial fibrillation and pneumonia,35 though results were not statistically significant. Asynchronous consults, in which NH providers sent written questions to specialists, found that 60% resulted in a new course of action and 30% of requests were resolved without the need for a face-to-face visit.28

Increased telemedicine use was associated with decisions to treat residents in place, as telemedicine consultants deemed potential transfers unnecessary.29 Results of this study are harmonious with qualitative work indicating that telemedicine may help address lack of on-site medical expertise and communication challenges.34 NH nurses reported that on-call physicians often do not trust nurse assessments, and the use of video may validate their assessment and prevent a transfer to a hospital.34 In an example of a perceived lack of parity between telemedicine and face-to-face care, a wound care study concluded that strengthening a primary team would be more advantageous than implementing a multidisciplinary team over telemedicine.36

Facility-level outcomes

Reductions in preventable ED and hospital transfers was a common outcome in 5 of the studies. In one multisite telemedicine consultation program, reductions in hospitalizations were clinically and statistically significant using a derived categorical variable indicating high and low engagement.33 Staff in high-engagement facilities used the after-hours and weekend telemedicine support program more frequently. The decrease in hospitalizations was 8.4% lower at high-engagement than low-engagement facilities.33 Another report found a clinically significant absolute risk reduction of 6.51% and a relative risk reduction of 27.24% in hospital readmissions.35 Admission to a health care service was higher in the control group than in the experimental group (χ2 = 3.96, P < .05).37 Over a period of 3 years, 500 potential transfers were deemed unnecessary within 20 NH pilot telemedicine sites.29 Conversely, a remote wound care team study found that the mean ED visit rate was 1.3 times larger during the intervention period, though this result was not statistically significant.32

Billing claims, medical record data, and facility reporting were used to track outcomes in 2 studies.33 , 35 Savings to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services were frequently reported. One after-hours and weekend telemedicine service cost $30,000 per NH annually.33 The study found that a 170-bed NH with 180 hospitalizations per year saw a reduction of 15 hospitalizations per year, and generated a net Medicare savings of $120,000.33 By another measure, 500 avoided transfers over a 3-year program prevented more than $5 million in admission-related charges.29 The other 2 studies calculated savings and costs on a per-resident level. Itemized direct care cost savings from wound care nurse practitioners accumulated to Can$649 per Canadian resident, though the authors flagged uncertainties in their calculation.32 One study's continuous monitoring and other telehealth equipment cost $1386 per patient, with hospital savings of $9234, though the analysis was not provided.35

Clinician, Family, and Resident Perspectives

Feedback from clinicians, families, and residents was collected in several studies (Tables 3 and 4 ). NH providers responded that they would be most likely to use telemedicine for dermatology, geriatric psychiatry, infectious disease, cardiology, and neurology consults.25 NH staff who did not use telemedicine opined that it would be a powerful tool to influence medical decision making.34 Palliative care specialists and NH physicians, nurses, personal support workers, and rehabilitative therapists’ knowledge of using palliative care (r = 0.565, P = .018), confidence in using palliative telemedicine (r = 0.673, P = .003), and overall telemedicine acceptance (r = 0.698, P = .002) was positively correlated with an increased number of videoconferences.39 More frequent usage seemed to improve satisfaction with the modality.

Table 3.

Analysis of Clinician Perspectives in Accordance with the Technology Acceptance Model

| Concept | Facilitators and Benefits | Barriers and Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Experience |

|

— |

| Job relevance |

|

|

| Output quality |

|

|

| Result demonstrability |

|

|

| Perceived Usefulness |

|

|

| Perceived ease of use | ||

| Intention to use | ||

| Usage behavior |

|

APP, advanced practice provider; TUQ, Telemedicine Usability Questionnaire.

Table 4.

Analysis of Resident and Family Perspectives in Accordance with the Technology Acceptance Model

| Concept | Facilitators and Benefits | Barriers and Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Experience | — | |

| Output quality |

|

— |

| Result demonstrability | — | |

| Perceived usefulness |

|

— |

| Perceived ease of use |

|

|

| Intention to use |

|

|

| Usage behavior |

|

|

4G, fourth-generation broadband cellular; TeSS, Telemedicine Satisfaction Scale; TUQ, Telemedicine Usability Questionnaire; Wi-Fi, wireless fidelity.

Two studies collected feedback from NH residents directly, who reported their experiences as positive.24 , 35 Family perspectives were explored in 3 of the articles.24 , 34 , 35 Family members considered telemedicine visits advantageous if they resulted in quicker access to a provider or resulted in more frequent visits.34 , 39 There was also agreement that families would benefit from joining consultations through videoconferencing.24 , 34

Facilitators and Barriers

Clinician-identified facilitators to telehealth implementation included having adequate technical support, integration into the electronic health record, and strong facility leadership.24 , 28 , 32 , 39 Perceived benefits included improved timeliness of resident's care, elevated productivity, improved access to specialist advice, increased connection opportunities between NH nurses and providers, and subjective gains from involving families in care.25 , 28 , 31 , 34 Resident- and family-identified facilitators included being able to see a provider sooner, high-quality audio and video, and functionality to allow family participation during visits.24 , 34 , 39

Clinician-identified barriers included poor audio quality, missing functionality, technical difficulties slowing time to connect, time required to clean and charge devices, reimbursement challenges, and lack of workforce allocation for telemedicine.24 , 25 , 31 , 32 , 36 , 39 Residents and families noted barriers as charging devices, preferences for in-person visits, and difficulties in connecting to Wi-Fi or cellular broadband.35 , 39

Discussion

This integrative review of 16 international studies illustrates the modes in which telemedicine and telehealth potentially expand access, cover gaps in care, improve resident outcomes, reduce unnecessary trips to the hospital, and generate cost savings for NHs. Throughout the studies, there is consensus in benefits to patient care, and enthusiasm or at least curiosity for its use from providers, residents, and family. In no study was there unequivocal evidence that telemedicine or telehealth negatively affected resident outcomes or presented an excessive cost burden.

This appraisal finds wide methodologic heterogeneity and low generalizability because of small sample sizes with poorly described characteristics, and study designs that fail to collect or report sufficient intervention data. These aspects impair the ability to construct overarching evidence-based recommendations and highlight the need for conducting future research with more comprehensive and consistent study designs.

Geriatric, wound care, psychiatric, and palliative specialist teleconsults were found most effective in this review. Some NH clinicians preferred in-person wound care nurse practitioners and palliative care providers over telemedicine providers.32 , 39 Results suggests that telemedicine enables rapid specialist consultations and allows on-call NH providers to evaluate residents from home. Similarly, ED telemedicine research programs found reductions in unnecessary transfers and that 18% to 66% of teleconsultations influenced patient diagnosis or management.41

Limited qualitative work explores telemedicine and telehealth in the NH setting. This scarcity may be due to the technologies' relatively recent emergence in the NH setting. Qualitative research emphasizes the experiences of residents, clinicians, and other users, which is beneficial to technology developers improving the usability and utility of systems. Although limited in this setting, in other settings, patients and caregivers have highly rated telehealth's impact on information sharing, consumer focus, and overall satisfaction.40 However, given the NH setting's unique nature, future work is needed to better understand these issues.

Difficulties related to staff turnover introduce training issues that impair the consistent implementation of telehealth interventions.32 Despite such issues, there appear to be numerous opportunities for telehealth and telemedicine in NH settings, especially given the relatively low rollout and operational costs. According to the survey data included in this integrative review, participants are generally enthusiastic toward the use of telemedicine and telehealth in NHs.

The results of the present review are consistent with the Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine's standards document that guides NHs on the use of telemedicine to evaluate and manage changes of condition for residents.42 Reductions in hospitalizations and emergency visits in particular are further supported by this review. This review adds new perspectives on remote monitoring in NHs and potential new metrics such as reductions in restraint use.

An earlier systematic review of telemedicine services for residents in NHs from 1990 to 2013 found that dermatology, geriatrics, psychiatry, and other specialties were successfully delivered via telemedicine while also showing economic savings.17 This review extends this prior work's findings as our included studies also found financially and clinically efficacious results with asynchronous dermatology teleconsultations,35 geriatric specialist teleconsultations,24 , 28 , 30 , 37 and psychiatric care delivered over telemedicine.37

COVID-19 has brought new difficulties as NH residents are at high risk because of resident age, comorbidities, and proximity to other residents and staff.9 Visitation restrictions meant to limit potential contagion from unnecessary in-person contact created a push for telehealth to enable family visitation, mental health services, and allow remote assessments by specialists. Hospital COVID-19 programs indicate that telemedicine helps preserve personal protective equipment, limits exposures bidirectionally, encourages fast triage, and allows a specialist group to service multiple facilities.43 A COVID-19 collaborative model between an academic hospital and NH enabled telemedicine consultations, infection advisory consultations, and nursing liaisons to prevent or limit outbreaks.44

Limitations of the Included Studies

Overall, there was a general lack of rigorous experimental study designs. Studies using a historical group for comparison lacked matching procedures or propensity scores, which results in a risk of a study's internal validity due to selection bias. A large number of studies used author-developed surveys, which present risks of measurement bias. In other cases, advanced statistical methods may have given more robust results by for example using Poisson regression models for the analysis of count data and multiple hospitalizations. This would have permitted predictions around the effectiveness of the intervention.45

No studies in this sample used a theoretical framework to guide their approach. Sampling strategies frequently were not described. Baseline characteristics of samples were poorly described, with few consistently captured demographic, psychometric, and physiological measures. This limited the analysis of person-level differences between groups. Inclusion of these data could help to identify disparities related to rurality, socioeconomics, or language barriers.

Sample sizes were frequently small, with one study reporting results from a single orthopedic surgeon.24 Most studies involved a small number of sites, thus limiting generalizability. Others involved multiple co-occurring treatments (eg, RPM, telemedicine, point-of-care testing) but lacked representation as independently measured covariates. A full critical analysis may be reviewed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Limitations of this Review

Encouraging telepharmacy, teledentistry, and telerehabilitation studies exist in NH settings but were out of scope for this review because of its focus on the medical-nursing nexus of telemedicine. This review used the ONC's definition of telehealth and did not include surveillance technology, passive monitoring, and robotics, though these are promising areas of research.16 , 46 Videoconferencing for connection between NH residents and family was not included. Telehealth support of family caregivers of persons living with dementia in residential care was not included, though interesting work is ongoing in this area.47

Implications

Practice

Stakeholders may choose to implement a pilot program to validate telehealth's suitability for their NH. Quality improvement outcomes such as number of unnecessary hospital transfers, satisfaction surveys, and changes in selected clinical measures may be the most appropriate outcomes to track.42 Further, technology implementations are more readily accepted when they are interoperable with existing system architecture.48

Geriatric psychiatry and dermatology teleconsultations specialties can be effectively delivered through telemedicine.25, 26, 27 , 32 Other work suggests after-hours telemedicine services help facilities maintain census and decrease patient transportation costs.49

Research

NH resident perceptions of telemedicine are absent from recent literature. Only 1 study used a patient-focused questionnaire.35 Community-based studies eliciting feedback from older participants indicated that telehealth was well-received.50 Similar studies may be undertaken in NHs. Furthermore, given the small size of many of the studies, performing embedded pragmatic clinical trials of those technologies with an underlying evidence base could provide more generalizable outcomes as well as information on effective implementation methods and intervention fidelity. Qualitative research could illuminate specifications for types of alerts that may be most beneficially triggered from RPM-collected data for NH residents.

Conclusions and Implications

This integrative review presents a comprehensive synthesis of empirical evidence regarding the state of the science on telemedicine and telehealth in NHs. There is evidence that telemedicine and telehealth may improve outcomes for patients, staff, and administrators in NHs, provide broader full-time coverage, and decrease costs. Telemedicine may help reduce the exposure to COVID-19 in NHs and decrease unnecessary hospitalizations. As may be expected, certain kinds of diagnostic support are better suited to remote settings than others. The research is far from comprehensive, indicating that this is a nascent field for future investigations into the implementation and adoption of these technologies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Supplementary Table 1.

Quantitative Study Critical Appraisal

| Study | Purpose | Methods | Variables and Measures | Statistical Analyses | Results | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al, 202024 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dadosky et al, 201835 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| De Luca et al, 201637 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| De Vito et al, 202036 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Driessen et al, 201825 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

• Twenty-question survey responses clearly described with 7-point Likert scale description |

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Georgeton et al, 201526 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gordon et al, 201627 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grabowski and O’Malley, 201433 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Helmer-Smith et al, 202028 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hofmeyer et al, 201629 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Low et al, 202030 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perri et al, 202014 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Stern et al, 201432 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yu et al, 201438 | ||||||

| Strengths |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ADL, activities of daily living; BANSS, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity; BMI, body mass index; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CIRS, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; ECG, electrocardiogram; EHR, electronic health record; EMDT, enhanced multidisciplinary teams; GDS, Geriatric Depression Score; GP, general practitioner; GSF-PIG, Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guidance; HF, heart failure; MDS, Minimum Dataset; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MSK, musculoskeletal; NH, Nursing home; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; RPM, remote patient monitoring; SD, standard deviation; SNF, skilled nursing facility; STROBE, Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology; TM, telemedicine.

Appraisal tools used: The Joanna Briggs Institute's (JBI) Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials was used to evaluate 3 RCTs included in the review (JBI, 2020). Nonrandomized experimental studies were evaluated with the JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies. Research engaging cross-sectional study designs were evaluated with JBI's Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies. JBI's Checklist for Cohort Studies aided the evaluation of cohort studies, and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist was used to appraise the qualitative study (CASP, 2018). Critical appraisal of a quality improvement was completed with the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) tool.

Supplementary Table 2.

Qualitative Study Critical Appraisal

| CASP Checklist Item | Stephens et al, 202034 |

Piau et al, 202031 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Strengths | Weaknesses | |

| Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? |

|

|

|

|

| Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? |

|

|

|

|

| Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? |

|

|

|

|

| Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? |

|

|

|

|

| Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? |

|

|

|

|

| Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? |

|

|

|

|

| Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? |

|

|

|

|

| Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? |

|

|

|

|

| Is there a clear statement of findings? |

|

|

|

|

| How valuable is the research? |

|

|

|

|

CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Program; IRB, institutional review board; NH, nursing home; NPS, neuropsychiatric symptoms; PLWD, person living with dementia; SWOT, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

References

- 1.World Health Organization National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Global health and aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-06/global_health_aging.pdf Available at:

- 2.World Health Organization World report on aging and health. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186463/1/9789240694811_eng.pdf?ua=1 Available at:

- 3.Daras L.C., Wang J.M., Ingber M.J., et al. What are nursing facilities doing to reduce potentially avoidable hospitalizations? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:442–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment: Workshop Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) Telemedicine and telehealth. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-initiatives/telemedicine-and-telehealth Available at:

- 6.Flodgren G., Rachas A., Farmer A.J., et al. Interactive telemedicine: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD002098. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002098.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Hospital Association Fact sheet: Telehealth. https://www.aha.org/factsheet/telehealth Available at:

- 8.Solis J., Franco-Paredes C., Henao-Martínez A.F., et al. Structural vulnerability in the U.S. revealed in three waves of covid-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:25–27. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMichael T.M., Currie D., Clark S., et al. Epidemiology of covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris D.A., Archbald-Pannone L., Kaur J., et al. Rapid telehealth-centered response to covid-19 outbreaks in postacute and long-term care facilities. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:102–106. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institutes of Biomedical Imaging and Engineering. Connected health—Mobile health and telehealth. https://www.nibib.nih.gov/research-funding/connected-health Available at:

- 12.National Institutes of Health mHealth tools for individuals with chronic conditions to promote effective patient-provider communication, adherence to treatment and self-management. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-18-386.html Available at:

- 13.National Institute on Aging IMPACT Collaboratory Pilot pragmatic clinical trials for people living with Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (AD/ADRD) and their care partners. https://impactcollaboratory.org/ Available at:

- 14.Health Resources and Services Administration Telehealth focused rural health research center program. https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/hrsa-20-023 Available at:

- 15.Batsis J.A., DiMilia P., Seo L., et al. Effectiveness of ambulatory telemedicine care in older adults: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1737–1749. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daly Lynn J., Rondón-Sulbarán J., Quinn E., et al. A systematic review of electronic assistive technology within supporting living environments for people with dementia. Dementia. 2019;18:2371–2435. doi: 10.1177/1471301217733649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edirippulige S., Martin-Khan M., Beattie E., et al. A systematic review of telemedicine services for residents in long term care facilities. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19:127–132. doi: 10.1177/1357633X13483256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rada R. Trends in information systems and long-term care: A literature review. Int J Healthc Inf Syst Inform. 2015;10:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittemore R., Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden R.J., Karsh B.T. The technology acceptance model: Its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joanna Briggs Institute Critical appraisal tools. https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools Available at:

- 23.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme CASP qualitative checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf Available at:

- 24.Cheng O., Law N.H., Tulk J., et al. Utilization of telemedicine in addressing musculoskeletal care gap in long-term care patients. JAAOS Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:e1900128. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Driessen J., Castle N.G., Handler S.M. Perceived benefits, barriers, and drivers of telemedicine from the perspective of skilled nursing facility administrative staff stakeholders. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37:110–120. doi: 10.1177/0733464816651884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georgeton E., Aubert L., Pierrard N., et al. General practitioners adherence to recommendations from geriatric assessments made during teleconsultations for the elderly living in nursing homes. Maturitas. 2015;82:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon S.E., Dufour A., Monti S., et al. Impact of a videoconference educational intervention on physical restraint and antipsychotic use in nursing homes: Results from the ECHO-AGE pilot study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:553–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helmer-Smith M., Fung C., Afkham A., et al. The feasibility of using electronic consultation in long-term care homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1166–1170e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmeyer J., Leider J., Satorius J., et al. Implementation of telemedicine consultation to assess unplanned transfers in rural long-term care facilities, 2012-2015: A pilot study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:1006–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low J.A., Toh H.J., Tan L.L., et al. The nuts and bolts of utilizing telemedicine in nursing homes—The gericare@north experience. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1073–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piau A., Vautier C., De Mauleon A., et al. Telemedicine for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in long- term care facilities: The DETECT study, methods of a cluster randomised controlled trial to assess feasibility. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020982. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stern A., Mitsakakis N., Paulden M., et al. Pressure ulcer multidisciplinary teams via telemedicine: A pragmatic cluster randomized stepped wedge trial in long term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:83. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grabowski D.C., O’Malley A.J. Use of telemedicine can reduce hospitalizations of nursing home residents and generate savings for Medicare. Health Aff. 2014;33:244–250. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephens C.E., Halifax E., David D., et al. “They don’t trust us”: The influence of perceptions of inadequate nursing home care on emergency department transfers and the potential role for telehealth. Clin Nurs Res. 2020;29:157–168. doi: 10.1177/1054773819835015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dadosky A., Overbeck H., Barbetta L., et al. Telemanagement of heart failure patients across the post-acute care continuum. Telemed J E Health. 2017;24:360–366. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Vito A.N., Sawyer R.J., LaRoche A., et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a multicomponent telehealth care management program in older adults with advanced dementia in a residential memory care unit. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2333721420924988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Luca R., Bramanti A., De Cola M., et al. Tele-health-care in the elderly living in nursing home: The first Sicilian multimodal approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28:753–759. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu P., Hailey D., Fleming R., et al. An exploration of the effects of introducing a telemonitoring system for continence assessment in a nursing home. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3069–3076. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perri G.A., Abdel-Malek N., Bandali A., et al. Early integration of palliative care in a long-term care home: A telemedicine feasibility pilot study. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18:460–467. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlando J.F., Beard M., Kumar S. Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.du Toit M., Malau-Aduli B., Vangaveti V., et al. Use of telehealth in the management of non-critical emergencies in rural or remote emergency departments: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25:3–16. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17734239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillespie S.M., Moser A., Gokula M., et al. Standards for the use of telemedicine for evaluation and management of resident change of condition in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gadzinski A.J., Andino J., Odisho A., et al. Telemedicine and eConsults for hospitalized patients during covid-19. Urology. 2020;141:12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Archbald-Pannone L.R., Harris D., Albero K., et al. Covid-19 collaborative model for an academic hospital and long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:939–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Austin P.C., Stryhn H., Leckie G., et al. Measures of clustering and heterogeneity in multilevel Poisson regression analyses of rates/count data. Stat Med. 2018;37:572–589. doi: 10.1002/sim.7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rantz M., Lane K., Phillips L., et al. Enhanced registered nurse care coordination with sensor technology: Impact on length of stay and cost in aging in place housing. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63:650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaugler J.E., Statz T., Birkeland R., et al. The residential care transition module: A single-blinded randomized controlled evaluation of a telehealth support intervention for family caregivers of persons with dementia living in residential long-term care. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:133. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01542-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harst L., Timpel P., Otto L., et al. Identifying barriers in telemedicine-supported integrated care research: scoping reviews and qualitative content analysis. J Public Health. 2019;28:583–594. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chess D., Whitman J.J., Croll D., et al. Impact of after-hours telemedicine on hospitalizations in a skilled nursing facility. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24:385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Demiris G., Thompson H., Boquet J., et al. Older adults’ acceptance of a community-based telehealth wellness system. Inform Health Soc Care. 2013;38:27–36. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2011.647938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]