Abstract

Background

Cognitive decline is common in older people. Numerous studies point to the detrimental impact of polypharmacy and inappropriate medication on older people’s cognitive function. Here we aim to systematically review evidence on the impact of medication optimisation and drug interventions on cognitive function in older adults.

Methods

A systematic review was performed using MEDLINE and Web of Science on May 2021. Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions on quantitative measures of cognitive function in older adults (aged > 65 years) were included. Single-drug interventions (e.g., on drugs for dementia) were excluded. The quality of the studies was assessed by using the Jadad score.

Results

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria. In five studies a positive impact of the intervention on metric measures of cognitive function was observed. Only one study showed a significant improvement of cognitive function by medication optimisation. The remaining four positive studies tested methylphenidate, selective oestrogen receptor modulators, folic acid and antipsychotics. The mean Jadad score was low (2.7).

Conclusion

This systematic review identified a small number of heterogenous RCTs investigating the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions on cognitive function. Five trials showed a positive impact on at least one aspect of cognitive function, with comprehensive medication optimisation not being more successful than focused drug interventions. More prospective trials are needed to specifically assess ways of limiting the negative impact of certain medication in particular and polypharmacy in general on cognitive function in older patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40266-022-00980-9.

Key Points

| This systematic review included 13 heterogeneous studies evaluating the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions (excluding single-drug trials) on cognitive function. |

| Most of the studies did not include medication optimisation (e.g., listing approaches) as an intervention, but used pharmacological interventions instead. |

| Five of the trials showed a positive impact on aspects of cognitive function. |

| Overall, there are few high-quality studies evaluating the impact of medication optimisation or drug interventions on cognitive functioning. |

| The improvement of cognitive function by these interventions should be addressed in future pharmacological studies. |

Introduction

Cognitive decline is common in older people [1, 2], especially after acute hospitalisation [3]. While the pathogenesis of cognitive decline and cognitive impairment is multifactorial, there are numerous reports on the negative impact of polypharmacy (often defined as ≥ 5 daily medications) and inappropriate drug treatment on cognitive functioning in older adults [4–12]. For instance, the use of anticholinergics/antimuscarinics, antiepileptics or benzodiazepines has been linked with drug-induced cognitive impairment [13–15], which increases the risk of dementia and mortality in older adults [16–18]. Therefore, assessment of approaches towards medication optimisation and pharmacological interventions is urgently needed to evaluate whether cognitive decline can be prevented (or reversed) or whether cognitive function can be improved by such methods. Those proven to be effective could then be utilised in addition to numerous existing non-pharmacological approaches [19, 20].

In recent decades, several screening tools and listing approaches [21–23] designed to improve drug treatment (medication optimisation) in older people such as the Beers Criteria [24], STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons' Prescriptions)/START (Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment) criteria [25] and the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list [26, 27] have been developed [21]. Previous studies have shown that most existing methods tested in randomised controlled trials were ineffective in improving clinical outcomes including those addressing cognitive function [21, 28]. Some trials, such as the trial using the FORTA list as an intervention, showed promising clinical effects on important parameters such as the Barthel index, but had no details on the intervention’s effects on cognition [21]. In addition, the impact of pharmacological interventions such as the withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs on cognitive function has been tested in older people [29] but the results were uncertain.

So far, the established cognitive evaluation methods for assessing the impact of anti-dementia drugs on cognition [30, 31] have not been applied to the study of the impact of polypharmacy on cognitive function in multimorbid older people. An exception is the documented effect of certain prescribing cascade drugs on cognition, but these are mostly in the form of case reports [32, 33].

To our best knowledge, the number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions (except for anti-dementia medication) on cognitive function in geriatric patients is limited. In this systematic review, we aimed to assess and summarise evidence from RCTs on the impact of interventions designed to attenuate polypharmacy and inappropriate drug treatment (medication optimisation) [22] and other pharmacological interventions apart from single drug trials (for example trials testing single drugs for dementia) on the quantitative measures of cognitive function in this vulnerable population. Since we were interested in all potential comprehensive interventions with a positive impact on cognitive function, pharmacological interventions were also included.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the methodological manual of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA [34]). Details of the PRISMA checklist and “Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design” (PICOS [35]) are provided in Supplementary Material 1 & 2. This systematic review was not previously registered in the PROSPERO database. The study was an initiative of the European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS) special interest group (SIG) on Pharmacology.

Search Strategy

Search terms were proposed by two authors (FP and MW) to all EuGMS Pharmacology SIG members who agreed to participate in this study (N = 25). The search terms were discussed and amended accordingly. The final search terms as depicted in Supplementary Material 3, were used to search MEDLINE and Web of science. The search was conducted on 19th May 2021 (end date). The start date was not restricted. The key elements in our search were cognitive function, drug treatment, geriatric patients, polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing. In our search, only RCTs were included for analysis.

Inclusion Criteria

We included RCTs on the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions on pre-defined quantitative measures of cognitive function in geriatric patients. Geriatric patients were defined as follows: aged ≥ 80 years or patients aged ≥ 65 years with significant typical comorbidities defined by having 3 or more active diagnoses from a predefined list: arterial hypertension, heart failure, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoporosis, type II diabetes mellitus, dementia, behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, depression, bipolar disorder, insomnia, chronic pain, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, incontinence, anaemia. Thus, robust and active older people aged < 80 years were not included. A broad definition of medication optimisation [36] was used that included not only medication review, but also educational interventions, care coordination, use of technology (e.g., Computerized Clinical Decision Support), or ‘brown bag’ analyses. For the latter, a physician, pharmacist or nurse reviews patient’s medications that have previously been put into a bag at home. For this purpose, patients need to put all of their prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines (OTCs) and supplements that they are currently using into the bag.

Exclusion Criteria

Single drug interventions for drugs approved for treatment in the field of interest (e.g., single drug interventions for dementia or pain) were excluded. However, single drug group interventions such as those relating to withdrawal of antiepileptics or antipsychotics or drug interventions involving at least two drug substances were included. Studies exclusively describing non-geriatric patients were excluded as were studies without measurement of cognitive function. No exclusions were made regarding the language of the study unless the European study group (please see affiliations of all authors) was not able to understand the language (e.g., articles written in Chinese, Russian or Japanese).

Study Selection

The search results were exported from MEDLINE & Web of Science to EndNote® [37], duplicates were searched for and removed using EndNote® and ultimately, they were exported to Excel® files (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Subsequently, 14 reviewers independently screened the titles (titles were divided between the reviewers) and abstracts of the manuscripts to identify relevant publications according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Abstracts were categorised as ineligible, possibly eligible, or clearly eligible. All abstracts chosen as clearly or possibly eligible for inclusion were screened by full-text analysis of the original publications in a second round by another reviewer independently. Records generating uncertainty regarding inclusion or exclusion criteria were discussed by FP and MW in order to reach consensus about inclusion.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The following data were extracted from the selected publications: PubMed ID (PMID), first author, publication year, type of study population, mean age of study participants and standard deviation if provided, number of study participants, percentage of female participants, outcome(s) relating to cognitive function, brief description of the intervention and its duration, details on medication review/medication optimisation, positive outcome(s) relating to cognitive function. Methodological quality, or risk of bias of clinical trials, was assessed by using a three-item questionnaire, known as the Jadad score [38]. For the determination of the Jadad score, drop-outs/withdrawals, randomisation, blinding, and the quality of the latter two items are calculated and a score is derived ranging from 0 (very poor) to 5 (rigorous) [38]. In the evaluation of the RCTs, positive study outcomes corresponded to at least one primary or secondary endpoint exposing a significant improvement by the intervention (i.e., p < 0.05).

Measurement of Cognitive Function Considered for Study Selection and Data Extraction

The following terms/assessments (including common synonyms) were chosen by the authors to cover various quantitative measures of cognitive function:

Neuropsychological Tests, Stroop test, Trail Making Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Wechsler Memory Scale, NEECHAM Confusion Scale, DOSS, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Neuropsychological Battery, Delirium Detection Score, Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Brief Alzheimer screen, Timed Test of Money Counting (TTMC), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Clock draw test, Clock Drawing test, Clock-drawing test, 3-item recall, The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS), Mini-Cog, The Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration (BOMC), Global Deterioration Scale, Confusion Assessment Method, Serial sevens, Reisberg-Scale, Dementia detection (DemTect), The 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT), Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT-10, AMT-4), Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM), The Short Confusion Assessment Method (short-CAM), months of the year backwards (MOTYB), Informant Single Question in Delirium, Informant single screening questions for delirium and dementia, The Single Question in Delirium (SQiD), Six-Item-Screener, Bamberger Demenz-Screening test (BDST), Severe Mini Mental State Examination, Test for early diagnosis of dementia with differentiation from depression (TFDD), Syndrom-Kurz-Test, Nursing Delirium Screening Scale, Delirium Observation Screening Scale, Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS), Mini-Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination, Nurses’ Observation Scale of Cognitive Abilities (NOSCA).

In addition, using three or more cognitive tests in a study was regarded as a comprehensive testing of cognitive function.

Results

Study Selection

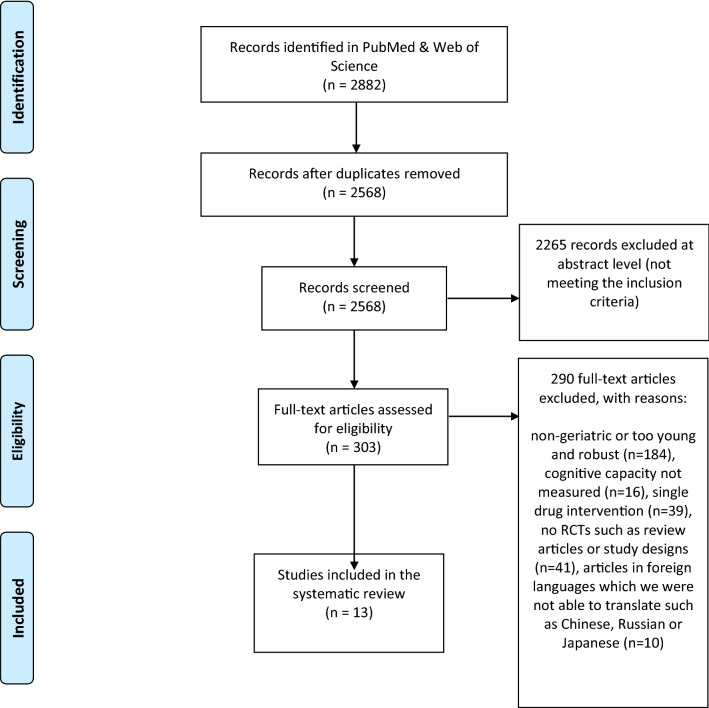

The search yielded 2568 publications, of which 2265 were excluded at the abstract assessment level (Fig. 1). The remaining 303 studies were reviewed in full-text: 290 were excluded based on the predefined criteria (vide supra), leading to the inclusion of 13 articles [39–51] in this systematic review.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions on quantitative measures of cognitive function in geriatric patients (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA])

The majority of the RCTs (10 of 13) used a comprehensive cognitive testing (3 or more tests) of cognitive function (Table 1). The total number of study participants, types of intervention, number of trials with positive outcome(s), and the number of trials with a Jadad score ≥ 3 (a trial with a score above 2 is considered to be of high quality [52]) are depicted in Table 1. In addition, a more comprehensive summary of all 13 RCTs found in this review is provided in Supplementary Material 4.

Table 1.

Results of the systematic review on the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions on quantitative measures of cognitive function in geriatric patients

| Total number of trials | Number of study participants | Number of trials on pharmacological interventions#/number of trials utilising medication optimisation## | Number of trials with positive outcome(s) | Number of studies with a Jadad score* of 3 or above | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional trials with aspects (1–2 tests) of cognitive function | 3 | 498 |

1 2 |

0 | 1 |

| Interventional trials with a comprehensive$ testing of cognitive function | 10 | 3159 |

7 3 |

5 | 6 |

$Three or more different tests of cognitive function were considered as comprehensive testing #Single-drug interventions for drugs approved for treatment in the particular field (for example, dementia, pain) were not included. However, “single drug group interventions” such as those with withdrawal of antiepileptics or antipsychotics or trials involving at least two drug substances were included

##A broad definition of medication optimisation was used including not only medication review, but also educational interventions, care coordination, use of technology, or ‘brown bag’ analyses

*The Jadad score which is a scale to assess the methodological quality or risk of bias of clinical trials is calculated by using a three-item questionnaire. Drop-outs/withdrawals, randomisation, blinding and the quality of latter two items are assessed. The derived score ranges from zero (very poor) to five (rigorous) [38]

Among the 13 identified RCTs, five trials [39, 42–44, 49] reported a positive impact on at least one quantitative measure of cognitive function, though the quality of the majority of these positive trials was low (four had a Jadad score of only two). In contrast, the majority of all 13 trials (7 of 13) had a Jadad score of 3 or more.

Only 5 of 13 studies included a medication optimisation and of those, only 1 showed a significant impact on cognitive function [49] (Tables 1 and 2). In total, 4 of 5 trials used a specific listing approach (i.e., they used a specific structured method. These were Beers Criteria®, STOPP criteria and START criteria) as a method for medication optimisation [46, 47, 49, 50] and only one study [49] using the STOPP criteria as part of a multicomponent intervention showed a positive impact on cognitive function (measured by a neurocognitive battery) of community-dwelling older people. In the study conducted by Cole et al [41], the intervention involved consultation and treatment by a psychiatrist and follow-up by a research nurse and the patient’s family physician and no specific listing approach was used.

Table 2.

An overview of cognitive tests and their frequency in the interventional studies included in this review and details on the interventions and assessments utilised in those studies

| Number of cognitive tests | Number of studies (thereof pharmacological interventions) | Number of studies with positive outcome (thereof pharmacological interventions) | Intervention(s) and cognitive tests (underlined and in italics) used in the studies without impact (separated by a semicolon) | Intervention(s) and cognitive tests (underlined and in italics) used in the studies with positive outcome (separated by a semicolon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 |

3 (1) |

0 (−) |

A multi-component intervention including medication review and recommendations to primary care providers regarding discontinuing or reducing medications associated with delirium, using the American Geriatrics Society Beers guidelines, versus usual care [46] Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale (MDS-CPS), Brief Interview of Mental Status (BIMS); Educational intervention for nursing staff working in the intervention wards/two 4-h interactive training sessions based on constructive learning theory to recognise harmful medications and adverse drug events [47] Verbal fluency and clock drawing tests; One group was treated with antioxidant formula F at a dose of one ampule/day in the morning immediately before breakfast [48] MMSE II and a three-point scale for sleeping; |

– |

| 3 or more tests |

10 (7) |

5 (4) |

In a parallel group design participants were randomised to receive 24 weeks of treatment with daily oral doses of 1000 mg cobalamin, a combination of 1000 mg cobalamin and 400 mg folic acid, or placebo [40] A neuropsychological test battery including MMSE; The intervention involved consultation and treatment by a psychiatrist and follow-up by a research nurse and the patient’s family physician [41] Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD), the Medical Outcomes 36-item Short Form (SF-36), the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), MMSE; Oral oestradiol 1mg daily and norethisterone 0.5 mg daily or placebo [45] Dementia Rating Scale, MMSE, Word List Memory, constructional praxis, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Digit Symbol-Coding, Trail Making Test, Part Al; Modified Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD (CERAD) Boston Naming Test; Single Multidisciplinary Multistep Medication Review (3MR) [50]. MMSE, Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home Version (NPI-NH); Discontinuation of antihypertensive medications [51]. MMSE & overall cognition (compound score): computed if 5 of the following 6 tests were available: Stroop Colour Word Test and Trail Making Test for executive functioning, 15-Word Verbal Learning Test and Visual Association Test for (immediate and delayed) verbal and picture memory and Letter-Digit Substitution Test for psychomotor speed |

Patients were withdrawn from their usual antiparkinsonian medications. On 3 consecutive days, they took 0.2 mg/kg oral methylphenidate or placebo followed 30 minutes later by a 1-h intravenous L-Dopa (2 mg/kg/h) or placebo infusion [39] Simple reaction time and choice reaction time Stroop test, covert orienting of spatial attention, and digit ordering. Self-assessed mood, anxiety, arousal or concentration; Four component intervention: exercise training, intake of high protein nutritional shakes, memory training, and medication review. Control group received standard care. Both groups were also given counselling regarding dietary habits, lifestyle recommendations, and domestic hazards [49] Neuropsychological performance as measured by Short and Medium-Term Verbal Memory, Animal Naming Test, evocation of words beginning with one explicit letter, designation of famous people’s names, Verbal designation of images and verbal abstraction of word pairs; Concurrent treatment with a AChEI and either folic acid (1 mg capsule) or placebo [42] Response according to the NICE criteria, MMSE, DSST, and IADL and Social Behaviour (SB) subscales of NOSGER; Treatment with Quetiapine (25–200 mg) or haloperidol (0.5– mg) in addition to cholinesterase inhibitors [43]. NPI, CERAD neuropsychological test battery (which included the following tests: verbal fluency, modified Boston Naming Test, MMSE, constructional praxis and recall, word-list memory, word-list recognition and recall), NOSGER; Oral tamoxifen 20 mg per day or oral raloxifene 60 mg per day [44] A cognitive test battery: Global cognition screening, verbal knowledge, verbal fluency, memory (figural and verbal), attention and working memory, spatial ability, fine motor speed |

MMSE mini-mental state examination, DAT The human dopamine transporter, VNTR variable number of tandem repeats, AD Alzheimer’s Disease, AChEI Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor, NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, DSST Digit Symbol Substitution Test, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, NOSGER Nurses Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients, HDRS Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, WCST Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, CERAD Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacological interventions: “single drug group interventions” such as those with withdrawal of antiepileptics or antipsychotics or trials involving at least two drug substances. Single drug interventions for drugs approved for treatment in the particular field (e.g., dementia, pain) were excluded

Five RCTs formally fulfilling the inclusion criteria had to be excluded as their readouts were related to depression [53–55] or BPSD/delusions [56, 57]. Dementia or related measures were inclusion or exclusion criteria in these trials; thus, they were detected by the search terms. Nevertheless, no measurements of aspects of cognition were reported in these trials.

Studies Addressing Aspects (≤2 Tests) of Cognitive Function (N = 3)

Juola et al [47] examined if educating nursing staff in assisted living facilities about harmful drug treatment has an impact on aspects of cognition as measured by verbal fluency and the clock drawing test; no significant difference between the groups was observed [47]. In this study, the nurses in the intervention group received two 4-h interactive training sessions to recognise potentially harmful medications and adverse drug events [47]. The Beers Criteria® was used in this trial.

Another study by Boockvar et al [46], which showed no impact on aspects of cognition also involved medication optimisation. In this trial, a multi-component intervention including medication review and recommendations to physicians regarding discontinuing or reducing medications associated with delirium was utilised. The Beers Criteria® were also used in this trial.

In contrast to the other two studies [46, 47], the trial by Cornelli et al [48] used a pharmacological intervention. But, similar to the other 2 studies, the intervention in this trial had no impact on aspects of cognition [48].

Studies Including a Comprehensive Testing (≥ 3 Tests) of Cognitive Function (N = 10)

In 5 out of 10 studies with a comprehensive testing of cognitive function a significant amelioration of cognitive function arising from a structured medication intervention was observed [39, 42–44, 49]. This intervention involved medication optimisation in only one study [49] and the remaining four were specific pharmacological treatments.

In one study of older patients with Parkinson’s disease [39], involving withdrawal of patients from their usual antiparkinsonian drugs, short-term treatment with methylphenidate alone was preferable over subsequent short-term intravenous L-Dopa treatment (with or without concomitant methylphenidate) as measured by a significantly decreased choice reaction time in the methylphenidate only treatment group. No differences regarding the Stroop test, digit ordering, simple reaction time, or covert orienting of attention validity effect were observed. Changes in self-assessed analogue ratings of mood, anxiety, arousal, or concentration did not differ significantly between the groups.

Connelly et al [42] assessed the impact of folic acid in addition to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Social Behaviour (SB) subscales of Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients (NOSGER) in patients with Alzheimer's Disease (AD). A significant difference was observed for the change from baseline in combined Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) and Social Behaviour scores between groups, but no significant changes in MMSE scores were reported. This study indicated that response to AChEI in patients with AD may be improved by the concomitant use of folic acid.

A comparative study in patients with AD investigated the effects of quetiapine and haloperidol on various aspects of cognition [43]. In this study, a comprehensive psychometric test battery, including the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) neuropsychological evaluation schedule and NOSGER were used. Both quetiapine and haloperidol reduced delusions and agitation. Quetiapine improved the mean scores in the depression and anxiety subscales. Both haloperidol and quetiapine also improved word recall. Quetiapine (but not haloperidol) had a significant positive effect on word-list memory.

A study in postmenopausal women compared the effects of tamoxifen and raloxifene on global and domain-specific cognitive function [44]. No differences were observed regarding global cognition, memory, visuospatial skills and verbal knowledge. However, there were significant time effects across the three visits for some of the cognitive measures. Compared to tamoxifen, raloxifene was associated with significantly higher scores for verbal memory.

In another study [49] utilising a multicomponent intervention consisting of exercise training, intake of high protein nutritional drink supplements, memory training, and medication review the neurocognitive battery test results improved significantly in the intervention group as compared to the control group at 3 and 18 months’ follow-up.

In 5 studies, no significant impact of the intervention on comprehensive tests of cognitive function [40, 41, 45, 50, 51] was observed. In two of those studies the intervention included a medication optimisation [41, 50].

An overview of cognitive tests used in all 13 studies and the frequency and types of interventions with and without significantly positive impact on aspect(s) of cognitive function is summarised in Table 2.

We found no studies with a negative impact of an intervention on cognitive function.

Discussion

This systematic review revealed that approximately 40% of the included studies reported a positive impact on at least one quantitative measure of cognitive function in older people with multimorbidity and associated polypharmacy. This proportion was lower for those studies utilising medication optimisation as part of the interventional approach [49] (Tables 1 and 2). In total, only 4 trials used a specific listing approach as a method for medication optimisation [46, 47, 49, 50], and only one of those studies [49] using the STOPP criteria as part of a multicomponent intervention showed a positive impact on cognitive function in community-dwelling older people. Other components of the intervention in this particular trial included memory training, exercise training and intake of high protein nutritional shakes. Thus, the interventional impact on cognitive function that may be specifically attributed to medication optimisation remains unclear in this report. Indeed, non-pharmacological approaches to improve cognition such as memory training or even effective hydration care may play a more important role in this context.

Two studies using the Beers criteria [46, 47] or combining the START/STOPP and Beers Criteria did not report improved cognitive function [50]. It is therefore speculative at this time to suggest that a patient-focused approach requiring intricate knowledge of the patient (e.g., FORTA) might have been more successful in relation to achieving improved cognition in older people with multimorbidity and associated polypharmacy.

Based on the very low number of studies found, we debated on whether to include 4 additional RCTs [53–57] in this review. However, these studies assessed depression or BPSD/delusions as an endpoint and they did not report outcome measures of cognition.

It does not come as a surprise, and is in line with previous reports [21, 28, 58, 59], that the total number of studies examining the impact of medication optimisation approaches on cognitive function is very limited and therefore the impact on this crucial geriatric outcome remains largely unclear.

The higher number of trials using pharmacological interventions when compared to medication optimisation approaches is notable. Those studies were heterogenous in nature and did not allow for direct comparisons. Nevertheless, half of them (4 of 8) showed a positive impact of the pharmacological intervention on cognitive function.

The compounds tested in the included studies of this systematic review (such as folic acid, cobalamin, sex steroids, selective oestrogen receptor modulators) were partially successful compared to placebo or a comparator, but none of those studies has the evidential power of changing medical practice or drug labelling. The Jadad scores were low (2.7) on average, and no follow-up or marketing approval studies for these hypothesis-generating RCTs could be detected in this review.

Despite the fact that the use of many medications has been associated with cognitive side effects in older adults, the number of RCTs examining approaches to improve cognitive functioning by optimising drug treatment is surprisingly low in this population with particular susceptibility to side effects of CNS drugs. This review shows that the complexity of reasons for cognitive impairment in older age is very challenging in regard to simple or more nuanced approaches to amelioration. Medication reviews, which could at least help to optimise drug treatment across all therapeutic areas, were not convincingly successful in this regard, although the optimal approaches to medication review towards cognitive protection still need to be tested.

Nevertheless, approximately 40% of the trials identified for inclusion in this systematic review showed a positive impact on aspect(s) of cognitive function. This indicates opportunities for improving cognitive function in older patients by medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions. However, these findings still need to be better explored and evaluated by further clinical trials.

Limitations

This systematic review was restricted to Web of Science and MEDLINE entries and to prespecified search terms. Therefore, relevant publications may have been overlooked. However, the likelihood of missing relevant studies with only one entry (if exclusively reported in Cochrane or Scopus, for example) was considered to be low as most studies typically have several detectable citations referring to each other. Also, unpublished trials were not searched for by contacting study investigators or sponsors. The analysis of results was primarily done by 14 investigators who could have partially misinterpreted data from RCTs. Finally, publication bias might exist, as trials with neutral or even negative effects on cognitive function may not have been published.

Conclusion

This systematic review indicates that the number of randomised controlled trials examining the impact of medication optimisation or pharmacological interventions on cognitive function is very limited and identified included studies are heterogenous and did not allow for direct comparisons or meta-analyses. About 40% of the trials showed a positive impact on at least one aspect of cognitive function. In the future, large-scale prospective high-quality clinical trials are needed to assess the impact of validated medication optimisation approaches or drug interventions on cognitive function using comprehensive assessment tools.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Author contributions

FP & MW contributed to the study conception and design. FP performed project administration and data collection. FP, MP, KI, GZ, ANP, KWT, BS, AG, WK, CR, AC, HB, MD, DOM, HG, MAF, TJMC, PC, JS, AM, ACJ, NVV, MSB, JASR, GS and RM screened all studies and assessed the risk of bias and quality of evidence. The manuscript was written by FP & MW. All authors contributed to validation of eligible studies, data analysis, and visualisation, commented on previous versions of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflicts of interest

MW was employed by AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, as director of discovery medicine (translational medicine) from 2003 to 2006, while on sabbatical leave from his professorship at the University of Heidelberg. Since returning to this position in January 2007, he has received lecturing and consulting fees from Bristol Myers, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, LEO, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Polyphor, Helsinn, Allergan, Allecra, Novo-Nordisk, Heel, AstraZeneca, Roche, Santhera, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, Berlin-Chemie und Daichii-Sankyo. FP, MP, KI, GZ, ANP, KWT, BS, AG, WK, CR, AC, HB, MD, DOM, HG, MAF, TJMC, PC, JS, AM, ACJ, NVV, MSB, JASR, GS and RM have no COIs to declare.

Availability of data and material

Available upon request.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Code availability

Not applicable

References

- 1.Cornelis MC, Wang Y, Holland T, et al. Age and cognitive decline in the UK Biobank. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0213948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eshkoor SA, Hamid TA, Mun CY, Ng CK. Mild cognitive impairment and its management in older people. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:687–693. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S73922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinnappa-Quinn L, Bennett M, Makkar SR, et al. Is hospitalisation a risk factor for cognitive decline in the elderly? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33:170–177. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore AR, O'Keeffe ST. Drug-induced cognitive impairment in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1999;15:15–28. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray SL, Lai KV, Larson EB. Drug-induced cognition disorders in the elderly: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1999;21:101–122. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199921020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starr JM, Whalley LJ. Drug-induced dementia. Incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf. 1994;11:310–317. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199411050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan ECK, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17:1185–1196. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1546841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niikawa H, Okamura T, Ito K, et al. Association between polypharmacy and cognitive impairment in an elderly Japanese population residing in an urban community. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:1286–1293. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park HY, Park JW, Song HJ, et al. The association between polypharmacy and dementia: a nested case-control study based on a 12-year longitudinal cohort database in South Korea. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0169463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vetrano DL, Villani ER, Grande G, et al. Association of polypharmacy with 1-year trajectories of cognitive and physical function in nursing home residents: results from a multicenter European study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:710–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii N, Mochizuki H, Sakai K, et al. Polypharmacy associated with cognitive decline in newly diagnosed Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2019;9:338–343. doi: 10.1159/000502351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawle MJ, Cooper R, Kuh D, Richards M. Associations between polypharmacy and cognitive and physical capability: a British birth cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:916–923. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai X, Campbell N, Khan B, et al. Long-term anticholinergic use and the aging brain. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nafti M, Sirois C, Kroger E, et al. Is benzodiazepine use associated with the risk of dementia and cognitive impairment-not dementia in older persons? The Canadian study of health and aging. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:219–225. doi: 10.1177/1060028019882037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur U, Chauhan I, Gambhir IS, Chakrabarti SS. Antiepileptic drug therapy in the elderly: a clinical pharmacological review. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae JB, Han JW, Kwak KP, et al. Impact of mild cognitive impairment on mortality and cause of death in the elderly. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:607–616. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pais R, Ruano L, Moreira C, et al. Prevalence and incidence of cognitive impairment in an elder Portuguese population (65–85 years old) BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:470. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01863-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312:2551–2561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farhang M, Miranda-Castillo C, Rubio M, Furtado G. Impact of mind-body interventions in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:643–666. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218002302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yorozuya K, Kubo Y, Tomiyama N, et al. A systematic review of multimodal non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive function in older people with dementia in nursing homes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;48:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000503445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazan F, Kather J, Wehling M. A systematic review and novel classification of listing tools to improve medication in older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75:619–625. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02634-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazan F, Petrovic M, Cherubini A, et al. Current evidence on the impact of medication optimization or pharmacological interventions on frailty or aspects of frailty: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00228-020-02951-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. Tools for assessment of the appropriateness of prescribing and association with patient-related outcomes: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:43–60. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0516-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society Updated AGS beers criteria(R) for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;2019(67):674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Mahony D, O'Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M, Forta. The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List Fourth version of a validated clinical aid for improved pharmacotherapy in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2021;2022(39):245–247. doi: 10.1007/s40266-022-00922-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M. Forta. The EURO-FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list: international consensus validation of a clinical tool for improved drug treatment in older people. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rankin A, Cadogan CA, Patterson SM, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:8165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jongstra S, Harrison JK, Quinn TJ, Richard E. Antihypertensive withdrawal for the prevention of cognitive decline. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:11971. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011971.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frederiksen KS, Cooper C, Frisoni GB, et al. A European Academy of Neurology guideline on medical management issues in dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1805–1820. doi: 10.1111/ene.14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt R, Hofer E, Bouwman FH, et al. EFNS-ENS/EAN Guideline on concomitant use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:889–898. doi: 10.1111/ene.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kristensen RU, Norgaard A, Jensen-Dahm C, et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication in people with dementia: a nationwide study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63:383–394. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kucukdagli P, Bahat G, Bay I, et al. The relationship between common geriatric syndromes and potentially inappropriate medication use among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:681–687. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picton CW. Medicines Optimisation: Helping patients to make the most of medicines. Good practice guidance for healthcare professionals in England. In. Royal Pharmaceutical Society 2013.

- 37.Gotschall T. EndNote 20 desktop version. J Med Libr Assoc. 2021;109:520–522. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2021.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camicioli R, Lea E, Nutt JG, et al. Methylphenidate increases the motor effects of L-Dopa in Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24:208–213. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eussen SJ, Ueland PM, Clarke R, et al. The association of betaine, homocysteine and related metabolites with cognitive function in Dutch elderly people. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:960–968. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507750912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole MG, McCusker J, Elie M, et al. Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of depression in older medical inpatients: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2006;174:38–44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connelly PJ, Prentice NP, Cousland G, Bonham J. A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of folic acid supplementation of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:155–160. doi: 10.1002/gps.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savaskan E, Schnitzler C, Schroder C, et al. Treatment of behavioural, cognitive and circadian rest-activity cycle disturbances in Alzheimer's disease: haloperidol vs. quetiapine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9:507–516. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705006036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Legault C, Maki PM, Resnick SM, et al. Effects of tamoxifen and raloxifene on memory and other cognitive abilities: cognition in the study of tamoxifen and raloxifene. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5144–5152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valen-Sendstad A, Engedal K, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on depressive symptoms and cognitive functions in women with Alzheimer disease: a 12 month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of low-dose estradiol and norethisterone. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:11–20. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181beaaf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boockvar KS, Judon KM, Eimicke JP, et al. Hospital elder life program in long-term care (HELP-LTC): a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2329–2335. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Juola AL, Bjorkman MP, Pylkkanen S, et al. Nurse education to reduce harmful medication use in assisted living facilities: effects of a randomized controlled trial on falls and cognition. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:947–955. doi: 10.1007/s40266-015-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornelli U. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease with a cholinesterase inhibitor combined with antioxidants. Neurodegener Dis. 2010;7:193–202. doi: 10.1159/000295663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romera-Liebana L, Orfila F, Segura JM, et al. Effects of a primary care-based multifactorial intervention on physical and cognitive function in frail, elderly individuals: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:1688–1674. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wouters H, Scheper J, Koning H, et al. Discontinuing inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:609–617. doi: 10.7326/M16-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moonen JE, Foster-Dingley JC, de Ruijter W, et al. Effect of discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people on cognitive functioning–the DANTE study leiden: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1622–1630. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavretsky H, Park S, Siddarth P, et al. Methylphenidate-enhanced antidepressant response to citalopram in the elderly: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:181–185. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192503.10692.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavretsky H, Siddarth P, Kumar A, Reynolds CF., 3rd The effects of the dopamine and serotonin transporter polymorphisms on clinical features and treatment response in geriatric depression: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:55–59. doi: 10.1002/gps.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mann AH, Blanchard M, Waterreus A. Depression in older people. Some criteria for effective treatment. Encephale. 1993;19(3):445–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merims D, Balas M, Peretz C, et al. Rater-blinded, prospective comparison: quetiapine versus clozapine for Parkinson's disease psychosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29:331–337. doi: 10.1097/01.WNF.0000236769.31279.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruths S, Straand J, Nygaard HA, Aarsland D. Stopping antipsychotic drug therapy in demented nursing home patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled study–the Bergen District Nursing Home Study (BEDNURS) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:889–895. doi: 10.1002/gps.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pazan F, Wehling M. Polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00479-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cherubini A, Laroche ML, Petrovic M. Mastering the complexity: drug therapy optimization in geriatric patients. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:431–434. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00493-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.