Abstract

Oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in several human diseases including Parkinson’s disease (PD). Curcuma comosa, a member of Zingiberaceae, is widely known in Thailand as an alternative medicinal herb for uterine inflammation and estrogenic properties. In this study (3S)-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-7-phenyl-(6E)-6-hepten-3-ol or compound 092 (C-092, or ASPP 092), a pure compound isolated from ethanol extract of C. comosa, was evaluated for neuroprotective effect on hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. C-092 demonstrated a radical scavenging effect with comparable efficacy to ascorbic acid and exhibited a neuroprotective effect via suppression of apoptotic cell death as evidenced by a reduction in phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase-3 expression. C-092 causes induction of Nrf-2, which is a transcription factor responsible for the expression of a range of antioxidant genes. Moreover, the reduction in catalase activity caused by hydrogen peroxide was also alleviated by C-092 treatment. These results suggested the therapeutic potential of this compound for neurodegenerative diseases caused by oxidative stress.

Keywords: SH-SY5Y, Curcuma comosa, Antioxidant, Nrf-2, Anti-apoptosis

Graphical abstract

SH-SY5Y; Curcuma comosa; Antioxidant; Nrf-2; Anti-apoptosis.

1. Introduction

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder associated with the loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) [1]. The exact etiology of PD is still not known, and aging is proposed as the major risk factor [2]. Although age is considered to be the greatest risk factor, mutations in several genes such as LARK2 and PINK1 are also involved in the pathogenesis of PD [3]. In addition, there is a link between exposure to certain environmental toxins—for example, pesticides, herbicides and heavy metals—and the risk of developing PD [4]. However, the discovery of synthetic neurotoxin MPTP, which can selectively damage the substantia nigra neurons and induce parkinsonism in both humans and primates, has shed light on the pathogenesis of PD [5]. Once taken up by the nigral neurons, MPTP in the form of MPP+ is highly concentrated in the mitochondria and inhibits Complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, resulting in the decline in ATP and marked free radical generation [6, 7, 8]. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated the correlation between mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of PD [9, 10]. Mitochondria are one of the major sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their dysfunction can lead to an increase in superoxide anion, and then hydrogen peroxide upon dismutation by superoxide dismutase [11]. Hydrogen peroxide is less harmful to cells compared to superoxide anion, however, in the presence of metal ions, it can be converted by Fenton reactions into highly reactive hydroxyl radicals that rapidly oxidize cellular DNA, proteins, and lipids [12]. Excessive production of ROS can also impair mitochondrial function, leading to apoptotic cascades and ultimately resulting in apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc [11].

In PD mouse models and cultured cells, upregulation of Bax expression, activation of caspase-3, and fragmentation of DNA are involved in mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis [13]. Transcriptional induction of Bax is induced by p53 that is activated through excessive release of ROS or DNA damage [14]. Thus, a defensive antioxidant system is crucial for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis during oxidative stress. Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) is a transcription factor associated with the induction of phase 2 detoxification enzymes and endogenous antioxidants through Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1-Nrf-2-antioxidant response element/electrophile response element (Keap-1-Nrf-2-ARE/ERE) pathways [15, 16].

Curcuma comosa (Roxb.), a member of the Zingiberaceae family, is widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions of Asia including Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. C. comosa is known as Waan Chak Mod Luk in Thai and it has long been used as traditional medicine for the treatment of postpartum uterine bleeding, peri-menopausal bleeding, and uterine inflammation. C. comosa possesses several biological effects such as anti-inflammatory [17] and estrogenic activities [18]. Besides crude extract, several fractions can be isolated from the rhizome of C. comosa. Both hexane and ethanol extracts exhibit anti-inflammatory effects [19]. Compound 092 (C-092, or ASPP 092, or (3S)-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-7-phenyl-(6E)-6-hepten-3-ol) (Figure 1A) possesses antioxidant activity as it can alleviate cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice via direct radical scavenging activity and restoration of the antioxidant systems [20]. C-092 demonstrated antioxidant potential in H2O2-induced retinal pigment epithelial cell toxicity by increasing the level of catalase (CAT) and attenuating the reduction of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) levels [21]. However, there is no study that demonstrates the protective activity of C-092 against oxidative stress-induced toxicity in neuronal cells; therefore, in this study, we investigate the potential therapeutic value of C-092 isolated from ethanol extract of C. comosa against oxidative stress-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structure of C-092. (B) The viability of SH-SY5Y cells at 12 h, and (C) at 48 h after treatment with various concentrations of C-092 (0.1–20μM), ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control (ctl). (D) Protective effect of C-092 on H2O2-induced cell deaths after exposure to 200 μM H2O2 for 12 h; #p < 0.001 compared to control, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared to H2O2-treated cells. (E) Effect of C-092 on intracellular ROS levels in cells incubated with H2O2, #p < 0.001 compared to control, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared to H2O2-treated cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM), Ham’s F12, Trypsin-EDTA, and trypan blue were purchased from Gibco BRL (USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS; PAA Laboratories, Australia), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 1, 1-diphenyl, 2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ascorbic acid, glutathione (GSH), glutathione reductase (GR) and β-NADPH were purchased from Sigma (USA), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) was purchased from Invitrogen (USA). Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, rabbit monoclonal anti-caspase-3, rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-p53, mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibodies, biotinylated protein ladder, HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit, and anti-mouse antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-Nrf-2 (H-300) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system was obtained from Pierce (USA). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and H2O2 were purchased from MERCK Millipore (Germany).

2.2. Plant material

The rhizomes of C. comosa were obtained from Nakhon Pathom province, Thailand. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Department of Plant Science, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand (SCMU No. 300). (3S)-7-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-(1E)-1-hepten-3-ol (C-092 or ASPP 092) was prepared as previously reported [22] and provided by Professor Apichart Suksamran, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Ramkhamhaeng University, Bangkok, Thailand. The compound was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 100 mM as stock solution and further diluted with DMSO to working concentrations, of which the final concentration of DMSO was maintained at 0.1%.

2.3. Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). The cells were grown in Eagle’s MEM/Ham’s F-12 (1:1), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, and 100 units/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with a 5% CO2 environment. The cells were sub-cultured when reaching 80 % confluence.

2.4. Antioxidant activity of C-092

Antioxidant activity was determined by the ability of the compound to scavenge the stable free radical, 1,1-diphenyl, 2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). Radical scavenging activity was characterized by decolorization of the purple DPPH to pale yellow, which can be measured at the absorbance of 520 nm [23]. For each experiment, 100 μl of C-092 in methanol at concentrations from 0.1 to 2 μM were mixed with 100 μl of 0.2 mM DPPH solution (1:1) in a 96-well plate and were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The spectrophotometer was used to measure absorbance at 520 nm. Assays were performed in triplicate. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The data were expressed as IC50 (the concentration to give 50% of the maximum scavenging effect).

2.5. Assessment of cell viability

Cell viability was determined with MTT assay. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well. The cells were treated with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and C-092 at various concentrations for 12 h and 48 h. Afterward, the cell culture media were removed, and the cells were incubated with MTT solution at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml for 3 h at 37 °C in the dark. The purple crystal formazan product of MTT was then solubilized with 100 μl DMSO. The optical density was measured at 570/620 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek instrument, Winooski, VT, USA). The cell viability was expressed as a percent of vehicle-treated control.

2.6. Measurement of intracellular ROS level

The intracellular ROS were measured by using DCFDA assay. In brief, the probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) can penetrate the cellular membrane and be enzymatically deacetylated by cellular esterase to 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (H2DCF), which can be oxidized by ROS to the highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). The fluorescence intensity was measured at 485 and 528 nm. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on a 96-well plate at 3 × 104 cells/well for 24 h prior to incubation with 20 μM of DCFDA probe for 1 h. Afterward, the cells were treated with C-092 at various concentrations from 0.1 to 1.0 μM for 1 h before exposure to 200 μM of H2O2 for 30 min in the dark. Fluorescence intensity was measured by fluorescence microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instrument, Winooski, VT). The data were expressed as the fold of control.

2.7. Western blot analysis of Nrf-2, phosphorylated-p53 (phospho-p53), and cleaved caspase-3 expression

For time course study of Nrf-2 expression, SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on a 6-well plate at 8×105 cells per well for 24 h prior to treatment with 2 μM of C-092 or 200 μM of H2O2. Protein samples were collected at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 h after the treatment. For time course study of phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase-3 expression, the cells were exposed to 200 μM of H2O2 for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 9 h prior to protein collection.

To determine the dose-response of Nrf-2, phospho-p53, and cleaved caspase-3 expression after treatment, SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on a 6-well plate (8 × 105 cells/well) for 24 h prior to incubation with C-092 at 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM for 1 h, followed by 200 μM H2O2 exposure. Protein samples were collected at 3 h after treatment for phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase-3 and at 4 h for Nrf-2.

Western blot analysis was performed as follows. The cells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and lysed with RIPA buffer and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected for protein measurement using Lowry’s method. Forty micrograms of proteins from each sample were used for separation by sodium dodecyl-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were thoroughly rinsed with tris-buffered saline containing 0.1 % Tween 20 (TBST) and blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat milk prior to incubation with primary antibody (1:2000) overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was rinsed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. The protein bands were visualized using an ECL detection system and quantified using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). β-actin was used as an internal control.

2.8. Measurement of catalase activity (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activities

For experiments on antioxidant activities, the cells were grown on a 6-well plate at a density of 8 × 105 cells/well and allowed to grow for 24 h, and were pretreated with C-092 at 1 and 2 μM for 1 h before exposure to 200 μM of H2O2 for 4 h. Afterward, the proteins were extracted, and the enzyme activities were assessed.

The CAT activity assay was performed according to Beers and Sizer [23]. Briefly, 490 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl containing 5 mM EDTA buffer pH 8.0 and 500 μl of 10 mM H2O2 solution were added into a quartz cuvette and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Next, 10 μl of the protein sample was added to the mixture. The absorbance of H2O2 can be measured at 240 nm. The enzyme activity can be calculated upon decreasing the absorbency of the solution. The decrease in H2O2 absorbance was monitored in real-time for 2 min with a UV-VIS spectrometer (GBC Scientific Equipment, Melbourne, Australia). Catalase activity was calculated as μM H2O2/min/mg protein using a molar extinction coefficient of 43.3 mM−1cm−1 and expressed as % of control.

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity was determined by an indirect coupled assay using tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BuOOH) [24]. The method involved oxidation of glutathione (GSH) and reduction of t-BuOOH by GPx, coupled with the recovery of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) by consumption of NADPH, which can be detected at 340 nm absorbance. In brief, 1 ml of the total reaction mixture consisted of 10 μl of the sample protein, 100 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl containing 5 mM EDTA buffer pH 8.0, 20 μl of 0.1 M glutathione (GSH), 100 μl of 10 units/ml glutathione reductase (GR), 100 μl of 2 mM NADPH, and 670 μl of deionized water. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 min, then 10 μl of 7 mM t-BuOOH was added to initiate the reaction. The consumption of NADPH was monitored at 340 nm for 2 min using a UV-VIS spectrometer (GBC Scientific Equipment, Melbourne, Australia). GPx activity was calculated as μM NADPH/min/mg protein using a molar extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1cm−1 and expressed as % of control.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey comparison test using GraphPad Prism software version 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The results were from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was considered at the value of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Antioxidant activity of C-092

Our study demonstrated that C-092 displayed radical scavenging activity at a similar level to ascorbic acid. The IC50 values of C-092 and ascorbic acid were 42.83 ± 0.6 μM and 43.83 ± 1.42 μM, respectively.

3.2. Protective effect of C-092 on H2O2 cytotoxicity

At 0.1μM to 2 μM, C-092 has no effect on cell viability of SH-SY5Y cells. However, at 5 μM of C-092, 25 % reduction in cell survival was observed after 12 h of treatment (Figure 1B). Moreover, the cell viability was further decreased to 47% of the control after 48 h of treatment (Figure 1C). Thus, the non-toxic concentrations of C-092 (0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 μM) were used to test the protective ability of the compound. H2O2 causes reduction of cell viability in a dose dependent manner. H2O2 at 200 μM, which reduces the cell viability to 60 % of control after 12 h of treatment, was selected for further experiments. Interestingly, pre-treatment of C-092 for 1 h significantly protected the cells from H2O2-induced toxicity in a dose-dependent manner, in which the cell viability after pre-treatment with C-092 at 0.5μM, 1 μM and 2 μM was 83.4 ± 2.07, 94.1 ± 4.07 and 96.8 ± 1.65% of control, respectively (Figure 1D).

3.3. Reduction of intracellular ROS level by C-092

C-092 displays antioxidant activity in DPPH assay; thus, we questioned whether this effect is also active in intracellular systems. The cells were incubated with DCFDA probe for 1 h and washed with PBS before treatment with C-092 for 1 h, followed by exposure to H2O2 for 30 min. H2O2 exposure caused intracellular ROS level to surge to 1.58 ± 0.07-fold of control, however, C-092 demonstrated the ability to reduce the intracellular ROS level in a concentration-dependent manner. C-092 at 0.5 μM and 1 μM significantly decreased the intracellular ROS to 1.28 ± 0.02 and 1.26 ± 0.01-fold of control, respectively (Figure 1E).

3.4. C-092 induces up-regulation of Nrf-2

We next aimed to characterize whether Nrf-2 plays a role in the observed antioxidant activity of C-092. Treatment with C-092 resulted in sustained up-regulation of Nrf-2 expression for more than 2-fold of the basal level for 6 h. At 9 h, the expression declined to 1.84-fold and continued to decline to the basal expression at 12 h (Figure 2A). Interestingly, up-regulation of Nrf-2 also occurred after treatment with H2O2 but in a different manner from C-092. H2O2 produced quick and non-sustained Nrf-2 induction that resolved within 1 h (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Time-course of Nrf-2 protein expression after the cells were treated with 2 μM C-092. (B) Time-course of Nrf-2 protein expression after the cells were exposed to 200 μM H2O2. (C) Nrf-2 expression after pretreating the cells with various concentrations of C-092 (0.1–2 μM) for 1 h before exposure to 200 μM H2O2 for 4 h. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control. Non-adjusted images from this figure are available in Supplementary Material.

Since the effect of H2O2 on Nrf-2 was completely worn off at 4 h, this time point was chosen for the next experiment. SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with C-092 at various concentrations for 1 h, followed by H2O2 exposure for 4 h before the analysis of Nrf-2 expression. C-092 induced Nrf-2 expression in a dose-dependent manner, in which the expression was 1.2-, 1.74-, and 2.26-fold of the basal level after treatment with C-092 at 0.5, 1, and 2 μM, respectively (Figure 2C). It is noted that H2O2 exposure did not alter the level and the pattern of Nrf-2 induction by C-092.

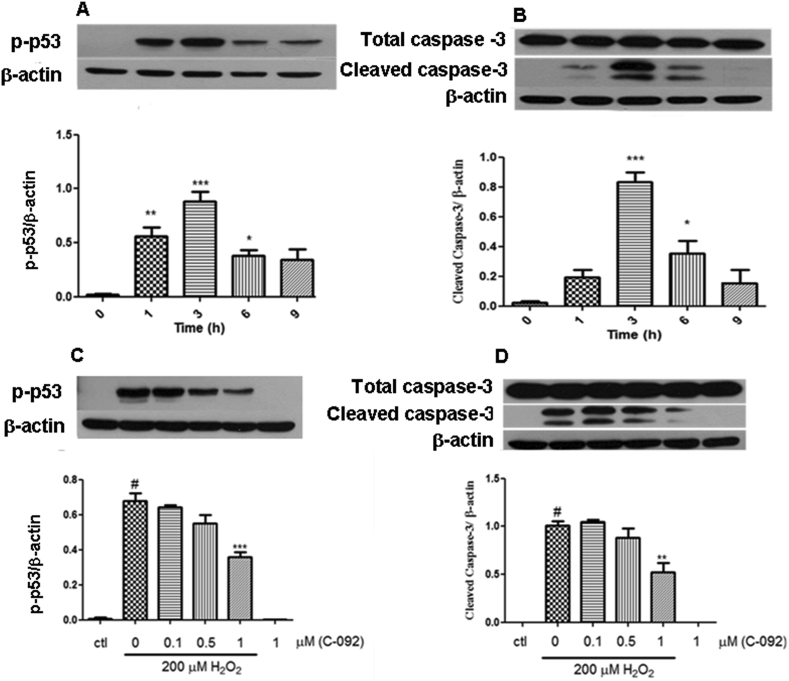

3.5. C-092 reduced protein levels of phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase-3

Next, we investigated whether inhibition of apoptosis is related to the protective effect of C-092. For this purpose, protein levels of phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase-3 were assessed by western blot analysis. After exposure to H2O2, p53 activation occurred at 1 h with the maximum effect at 3 h. A similar pattern was observed in caspase-3 activation, as measured by the level of cleaved caspase-3 expression (Figure 3A and 3B). Pre-treatment with C-092 for 1 h prior to H2O2 exposure for 3 h resulted in a reduction of phospho-p53 and cleaved caspase-3 levels, in which significant reduction was observed after 1μM treatment (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

(A) Time-course of p-p53 protein expression and (B) cleaved caspase-3 protein expression after the cells were exposed to 200 μM H2O2. ∗p < 0.5, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared to control. (C) The levels of p-p53 protein expression and (D) cleaved caspase-3 protein expression after pretreating the cells with various concentrations of C-092 (0.1–1 μM) for 1 h before exposure to 200 μM H2O2 for 3 h. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared to H2O2-treated group and #p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control. Non-adjusted images from this figure are available in Supplementary Material.

3.6. C-092 can restore the activity of antioxidant enzymes, CAT and GPx

Treatment with H2O2 significantly reduced the activity of CAT to 69.28 ± 1.13% of control. However, C-092 at 1 μM and 2 μM significantly restored CAT activity to 89.95 ± 5.26% and 85.33 ± 1.72% of control, respectively (Figure 4A). Similarly, treatment with H2O2 reduced GPx activity to 72.32 ± 6.02% of control, and administration of C-092 at 1 μM and 2 μM restored the GPx activity to 82.0 ± 6.19% and 84.2 ± 5.53% of control, respectively; however, the levels were not statistically significant (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Effect of C-092 on the restoration of catalase and (B) glutathione peroxidase activities after pretreating the cells with C-092 (1–2 μM) for 1 h before exposure to 200 μM H2O2 for 4 h, ∗p < 0.05, compared to H2O2-treated group and #p < 0.001 compared to the untreated control.

4. Discussion

A number of studies have already established the effects of ethanol extracts of C. comosa, including its anti-inflammatory effect [19] and antioxidant activity [20, 21]. This study emphasized on its antioxidant action and cytoprotective effect on SH-SY5Y cells intoxicated by H2O2. Studies have frequently employed H2O2 as a simple model for oxidative stress and here we selected 200 μM as an appropriate concentration at which 40% of cell deaths occurred. C-092 was assessed for its cytotoxic effect on cell viability of SH-SY5Y in a range of concentrations for 12 h and 48 h. In short-term exposure, the cells were afflicted at 5 μM with 25% cell loss and 47% at long-term exposure (48 h), but no significant cell death was observed up until 2 μM in our experimental scheme. Then, the isolated pure C-092 was examined for its direct scavenging effect by DPPH assay and observed to be a potent antioxidant with comparable efficiency to ascorbic acid in this aspect. In accordance with that result, pre-incubation of C-092 can significantly reduce the level of ROS produced by H2O2 in a concentration-related pattern when the cells are measured for intracellular ROS levels after exposure to H2O2 for 30 min. This direct radical trapping capacity may derive from its bearing a catechol moiety, which has the electron-donating properties of its (OH) group at C-7 position of the structure of C-092. Similarly, other phenolic compounds such as flavonoids contain a catechol group (ring B) attached to a flavonoid structure (AC ring) and OH groups, features that are both supposed to be critical for radical scavenging potency [25].

It has been found that this compound has a direct scavenging effect, as measured by DPPH assay, at an equivalent efficiency to ascorbic acid. The IC50 value of C-092 in this study was similar to that previously reported by Jitsanong et al [21]. Interestingly, C-092 also demonstrated antioxidant activity in the cells. Pre-incubation of the compound significantly reduced the level of ROS production by H2O2 in a concentration-dependent pattern. We questioned whether the observed intracellular antioxidant activity could be attributed to direct radical scavenging through the catechol moiety in C-092 or through other unexplored mechanisms. Natural compounds exert antioxidant activities through several mechanisms, either directly through quenching of intracellular ROS or indirectly through promoting cellular antioxidant systems, such as the Keap-1-Nrf-2/ARE pathway [26]. Among nutraceutical products, carnosic acid, which is one of the main constituents in rosemary, was reported to protect neurons through the activation of the Keap-1-Nrf-2 pathway in both vitro and vivo models [27]. Nrf-2 activation confers protective effects against toxicity from environmental and carcinogenic insults [15, 16]. Upon exposure to oxidative stimuli, Nrf-2 is dissociated from its binding partner, Keap-1, and translocated to the nucleus to interact with specific DNA sequences, ARE/ERE, which drive the expression of antioxidant genes that encode either direct antioxidants and reductive cofactors or enzymes involved in the proteosome system that also participate in detoxification [16, 28]. There is little known about pure C-092’s mechanism despite the extensive reporting on its antioxidant effects. Hence, we investigated it and found that C-092 up-regulated Nrf-2 at a level of protein expression that was maintained over a period of 9 h. Pro-oxidants like H2O2 can stimulate Nrf-2 induction but in a brisk manner dissimilar to that of C-092, resulting in cell death. It is likely that differences in Nrf-2 response patterns lead to different consequences. To observe the effect of co-administration of C-092 and H2O2 on Nrf-2 expression, the cells were pre-incubated with various concentrations of C-092 before exposure to H2O2. H2O2 did not hamper the effect of C-092 on Nrf-2 activation. Moreover, the level of Nrf-2 induction was in accordance with the concentration of C-092. This result suggested that the protective mechanism of C-092 against oxidative damage might be in fact mediated through the Nrf-2 activation pathway. Our results are in line with the results of several recent studies demonstrating that Nrf-2 activators derived from plants or synthetic compounds such as curcumin [29], sulforaphane [30], lycopene [31], resveratrol [32], and dimethyl fumarate [33] are associated with neuroprotection.

A battery of cellular defense molecules, including thiol-containing molecules (e.g. thioredoxin, glutathione), radical inactivation enzymes (e.g. SOD, CAT, Gpx), and nucleophile-trapping molecule (e.g. glutathione-s-transferase; GST) are Nrf-2 driven genes [16]. Thus, we next investigated the enzymes that play a role in inactivating the hydroperoxides and are under Nrf-2 regulation such as CAT and Gpx. In regard to this aspect, C-092 significantly attenuated the reduction of CAT activity by H2O2. Interestingly, a very recent study has proposed that CAT plays a critical role in cellular defense against H2O2-induced cell death in astrocytes via Nrf-2 regulation [34]. Although results for Gpx activity showed a similar trend to those for CAT activity, they were not statistically significant. The data correlated with the total GSH content (data not shown). However, it has been reported that Gpx activity was not solely dependent on Nrf-2 activity [35]; Gpx can also be regulated by other transcription factors such as p53 [36]. Additional studies have suggested that Nrf-2 protection is independent of de novo glutathione synthesis [37, 38]. Another possible reason for the minimal restoration of the level of glutathione and GPx activity in this study might be due to the catechol moiety of the compound. It has been reported that catecholic antioxidants can shift oxidative damage from lipid peroxidation to thiol arylation [39]. Nevertheless, the current data suggest that C-092 protected cells from oxidative damage via Nrf-2 downstream effectors other than GPx activity.

It is well established that oxidants like H2O2 induce apoptotic cell death by causing DNA damage [40] that subsequently activates transcription factor p53 [41]. Moreover, Nrf-2 and p53 also cross-talk to each other as p53 is negatively regulated by MDM2 which is, in turn, regulated by Nrf-2. Binding of MDM2 to p53 results in ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of p53 [42]. Our study demonstrated that phosphorylation of p53 at serine 15, which is important for activation of p53 [43], occurred after exposure to H2O2. Once p53 is activated, it triggers the transcription of target genes that subsequently promote apoptosis [44]. When C-092 was given, the p-p53 level decreased in accordance with the increasing dose of C-092, with a significant decline at 1 μM. We next investigated the apoptosis executioner caspase-3 level. As with p-p53, cleaved caspase-3 expression was induced by H2O2, and C-092 treatment appeared to significantly lower the expression at 1μM. Our data suggested for the first time that C-092 can protect cells against p53-mediated apoptotic cell death through Nrf-2 activation. Further studies are needed to clarify the details of downstream effectors of Nrf-2 that mediate this effect.

Accumulating evidence confirms the involvement of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of PD [45]. Our recent study reported that C-092 exhibited anti-inflammatory activity in lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation through suppression of the production of NO along with the suppression of iNOS expression in LPS-stimulated HAPI cells, and these effects originated from its ability to attenuate the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, as determined by the reduction in p–NF–κB and p-IκB kinase (IKK) protein levels. In addition, C-092 significantly lowered LPS-activated intracellular ROS production and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation [46]. In keeping with the results of this study, the antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties of C-092 (ASPP 092) in astroglia were also reported in our other previous study [47]. Although, the pharmacological activities of C. comosa, either in the forms of crude extracts or pure compounds, have been widely studied, there are few reports about the pharmacokinetics of this plant. However, it has been demonstrated that the pure compounds isolated from the hexane extract are distributed in the brain, liver, kidney, ovaries and uteri of rats after oral and intravenous administration [48], and the hexane extract has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and improve learning and memory on ovariectomized rats [49]. Since inflammation and oxidative stress are the key players in the pathogenesis of PD, using agents that have more than one effect may provide more therapeutic value in neurological diseases caused by neuroinflammation and oxidative stress such as PD.

5. Conclusion

In our study, C-092 exhibited protection against oxidative stress through a direct antioxidant effect as radical scavenger in combination with an indirect effect as a Nrf-2 inducer. It also demonstrated an ability to restore the antioxidant enzyme CAT activity, which might be related with Nrf-2 activation. On top of that, C-092 can suppress apoptotic cell death induced by H2O2 by decreasing the protein levels of p-p53 and cleaved caspase-3 in a dose-dependent manner. Taken together, C-092 is a potential plant-derived antioxidant nutraceutical product that can be effective in protecting neurons against oxidative damage and neurodegeneration.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Zon Mie Khin Aung: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Nattinee Jantaratnotai: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Pawinee Piyachaturawat: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Pimtip Sanvarinda: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the office of the Higher Education Commission and Mahidol University under the National Research Universities Initiative (NRU).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Fearnley J.M., Lees A.J. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez M., Morales I., Rodriguez-Sabate C., Sanchez A., Castro R., Brito J.M., et al. The degeneration and replacement of dopamine cells in Parkinson’s disease: the role of aging. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8:80. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pankratz N., Foroud T. Genetics of Parkinson disease. Genet. Med. 2007;9(12):801–811. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31815bf97c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kieburtz K., Wunderle K.B. Parkinson’s disease: evidence for environmental risk factors. Mov. Disord. 2013;28(1):8–13. doi: 10.1002/mds.25150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langston J.W., Langston E.B., Irwin I. MPTP-induced parkinsonism in human and non-human primates-clinical and experimental aspects. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 1984;100:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsay R.R., Salach J.I., Singer T.P. Uptake of the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MPP+) by mitochondria and its relation to the inhibition of the mitochondrial oxidation of NAD+-linked substrates by MPP+ Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986;134(2):743–748. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsay R.R., Kowal A.T., Johnson M.K., Salach J.I., Singer T.P. The inhibition site of MPP+, the neurotoxic bioactivation product of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine is near the Q-binding site of NADH dehydrogenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987;259(2):645–649. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan P., DeLanney L.E., Irwin I., Langston J.W., Di Monte D. Rapid ATP loss caused by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in mouse brain. J. Neurochem. 1991;57(1):348–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen A.D., Schapira A.H., Jenner P., Marsden C.D. Oxidative stress and Parkinson’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1996;786:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb39064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J., Perry G., Smith M.A., Robertson D., Olson S.J., Graham D.G., et al. Parkinson’s disease is associated with oxidative damage to cytoplasmic DNA and RNA in substantia nigra neurons. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;154(5):1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin T.K., Liou C.W., Chen S.D., Chuang Y.C., Tiao M.M., Wang P.W., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Chang Gung Med. J. 2009;32(6):589–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dauer W., Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39(6):889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perier C., Tieu K., Guegan C., Caspersen C., Jackson-Lewis V., Carelli V., et al. Complex I deficiency primes Bax-dependent neuronal apoptosis through mitochondrial oxidative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(52):19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508215102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gansauge S., Gansauge F., Gause H., Poch B., Schoenberg M.H., Beger H.G. The induction of apoptosis in proliferating human fibroblasts by oxygen radicals is associated with a p53- and p21WAF1CIP1 induction. FEBS Lett. 1997;404(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang D.D. Mechanistic studies of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway. Drug Metab. Rev. 2006;38(4):769–789. doi: 10.1080/03602530600971974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kensler T.W., Wakabayashi N., Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jantaratnotai N., Utaisincharoen P., Piyachaturawat P., Chongthammakun S., Sanvarinda Y. Inhibitory effect of Curcuma comosa on NO production and cytokine expression in LPS-activated microglia. Life Sci. 2006;78(6):571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winuthayanon W., Suksen K., Boonchird C., Chuncharunee A., Ponglikitmongkol M., Suksamrarn A., et al. Estrogenic activity of diarylheptanoids from Curcuma comosa Roxb. Requires metabolic activation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57(3):840–845. doi: 10.1021/jf802702c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sodsai A., Piyachaturawat P., Sophasan S., Suksamrarn A., Vongsakul M. Suppression by Curcuma comosa Roxb. of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate stimulated human mononuclear cells. Int. Immunopharm. 2007;7(4):524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jariyawat S., Kigpituck P., Suksen K., Chuncharunee A., Chaovanalikit A., Piyachaturawat P. Protection against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice by Curcuma comosa Roxb. ethanol extract. J. Nat. Med. 2009;63(4):430–436. doi: 10.1007/s11418-009-0345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jitsanong T., Khanobdee K., Piyachaturawat P., Wongprasert K. Diarylheptanoid 7-(3,4 dihydroxyphenyl)-5-hydroxy-1-phenyl-(1E)-1-heptene from Curcuma comosa Roxb. protects retinal pigment epithelial cells against oxidative stress-induced cell death. Toxicol. Vitro. 2011;25(1):167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suksamrarn A., Eiamong S., Piyachaturawat P., Byrne L.T. A phloracetophenone glucoside with choleretic activity from Curcuma comosa. Phytochemistry. 1997;45(1):103–105. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beers R.F., Jr., Sizer I.W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;195(1):133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weydert C.J., Cullen J.J. Measurement of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in cultured cells and tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5(1):51–66. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amić D., Davidović-Amić D., Bešlo D., Trinajstić N. Structure-radical scavenging activity relationships of flavonoids. Croat. Chem. Acta. 2003;76(1):55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natalie A., Kelsey H.M. Nutraceutical antioxidants as novel neuroprotective agents. Molecules. 2010;15:7792–7814. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satoh T., Kosaka K., Itoh K., Kobayashi A., Yamamoto M., Shimojo Y., et al. Carnosic acid, a catechol-type electrophilic compound, protects neurons both in vitro and in vivo through activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway via S-alkylation of targeted cysteines on Keap1. J. Neurochem. 2008;104(4):1116–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You A., Nam C.W., Wakabayashi N., Yamamoto M., Kensler T.W., Kwak M.K. Transcription factor Nrf2 maintains the basal expression of Mdm2: an implication of the regulation of p53 signaling by Nrf2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;507(2):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong W., Yang B., Wang L., Li B., Guo X., Zhang M., et al. Curcumin plays neuroprotective roles against traumatic brain injury partly via Nrf2 signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018;346:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo I.H., Kim M.J., Kim J., Sung J.J., Park S.T., Ahn S.W. The anti-inflammatory effect of sulforaphane in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Kor. Med. Sci. 2019;34(28):e197. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C.B., Wang R., Yi Y.F., Gao Z., Chen Y.Z. Lycopene mitigates beta-amyloid induced inflammatory response and inhibits NF-kappaB signaling at the choroid plexus in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018;53:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuang Y.C., Chen S.D., Hsu C.Y., Chen S.F., Chen N.C., Jou S.B. Resveratrol promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and protects against seizure-induced neuronal cell damage in the Hippocampus following status epilepticus by activation of the PGC-1alpha signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(4) doi: 10.3390/ijms20040998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L., Vollmer M.K., Kelly M.G., Fernandez V.M., Fernandez T.G., Kim H., et al. Reactive gliosis contributes to Nrf2-dependent neuroprotection by pretreatment with dimethyl fumarate or Korean red ginseng against hypoxic-ischemia: focus on hippocampal injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020;57(1):105–117. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-01760-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.James A. Dowell JAJ. Mechanisms of Nrf2 protection in astrocytes as identified by quantitative proteomics and siRNA screening. PLoS One. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu H., Itoh K., Yamamoto M., Zweier J.L., Li Y. Role of Nrf2 signaling in regulation of antioxidants and phase 2 enzymes in cardiac fibroblasts: protection against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species-induced cell injury. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(14):3029–3036. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan M., Li S., Swaroop M., Guan K., Oberley L.W., Sun Y. Transcriptional activation of the human glutathione peroxidase promoter by p53. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(17):12061–12066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kann S., Estes C., Reichard J.F., Huang M.Y., Sartor M.A., Schwemberger S., et al. Butylhydroquinone protects cells genetically deficient in glutathione biosynthesis from arsenite-induced apoptosis without significantly changing their prooxidant status. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;87(2):365–384. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaPash Daniels C.M., Austin E.V., Rockney D.E., Jacka E.M., Hagemann T.L., Johnson D.A., et al. Beneficial effects of Nrf2 overexpression in a mouse model of Alexander disease. J. Neurosci. 2012;32(31):10507–10515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1494-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boots A.W., Haenen G.R., den Hartog G.J., Bast A. Oxidative damage shifts from lipid peroxidation to thiol arylation by catechol-containing antioxidants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1583(3):279–284. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imlay J.A., Chin S.M., Linn S. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science. 1988;240(4852):640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.2834821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson W.G., Kastan M.B. DNA strand breaks: the DNA template alterations that trigger p53-dependent DNA damage response pathways. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):1815–1823. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rotblat B., Melino G., Knight R.A. NRF2 and p53: Januses in cancer? Oncotarget. 2012;3(11):1272–1283. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shieh S.Y., Ikeda M., Taya Y., Prives C. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 1997;91(3):325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moll U.M., Zaika A. Nuclear and mitochondrial apoptotic pathways of p53. FEBS Lett. 2001;493(2-3):65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grotemeyer A., McFleder R.L., Wu J., Wischhusen J., Ip C.W. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease - putative pathomechanisms and targets for disease-modification. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.878771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiamvoraphong N., Jantaratnotai N., Sanvarinda P., Tuchinda P., Piyachaturawat P., Thampithak A., et al. Concurrent suppression of NF-kappaB, p38 MAPK and reactive oxygen species formation underlies the effect of a novel compound isolated from Curcuma comosa Roxb. in LPS-activated microglia. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017;69(7):917–924. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vattanarongkup J., Piyachaturawat P., Tuchinda P., Sanvarinda P., Sanvarinda Y., Jantaratnotai N. Protective effects of a diarylheptanoid from Curcuma comosa against hydrogen peroxide-induced astroglial cell death. Planta Med. 2016;82(17):1456–1462. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-109173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su J., Sripanidkulchai K., Suksamrarn A., Hu Y., Piyachuturawat P., Sripanidkulchai B. Pharmacokinetics and organ distribution of diarylheptanoid phytoestrogens from Curcuma comosa in rats. J. Nat. Med. 2012;66(3):468–475. doi: 10.1007/s11418-011-0607-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su J., Sripanidkulchai K., Wyss J.M., Sripanidkulchai B. Curcuma comosa improves learning and memory function on ovariectomized rats in a long-term Morris water maze test. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.