Abstract

Due to the numerous side effects of conventional drugs against herpetic infections and the growing phenomenon of resistance, the researchers turned to natural compounds as a source of new drugs because they are less toxic than the synthetic molecules. This study aimed to analyse the activity of Pistacia vera L. male floral bud extracts, against the replication of herpes simplex virus type 2, as well as to investigate their mode of action, isolate, and identify the active compound. Cell viability and anti-herpes virus activity were performed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide and the plaque reduction assay, respectively. Three extracts (ethanolic, aqueous and polysaccharide extracts) were tested, only aqueous and polysaccharide extracts had anti-herpetic activity with a selectivity index of 29.12 and 20.25, respectively. Investigation about the mechanism of action indicated that the two active extracts inhibited the virus replication by direct contact with virucidal selectivity indexes of 39.15 and 32.09, respectively. An active compound was isolated from the aqueous extract using TLC bio-guided assay: it was identified as gallic acid by high-performance liquid chromatography–diode array detection coupled with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC–DAD–ESI-MSn). The antiviral activity of Pistacia vera L. has been previously shown. The selectivity index of gallic acid is much lower than that of the active extract from which it has been isolated. Therefore, we can consider the aqueous extract prepared from Pistacia vera L. male floral buds as a promising natural product for treating herpetic diseases.

Keywords: Pistacia vera L., Male floral buds, Herpes virus, Cytotoxicity, Antiviral activity, Gallic acid

Introduction

Pistacia vera L. is also known by the common name pistachio, belongs to the Anacardiaceae family (Tomaino et al. 2010). It is productive within the harsh desert climates and is native to the arid zones of West and Central Asia and widely distributed in the Mediterranean region as well as the USA (Alma et al. 2004; Sonmezdag et al. 2017). This plant has been introduced away from its center of natural distribution and domestication only in the last century. It develops mainly in Tunisia, Syria, Iraq, Italy, Turkey, Iran, Greece, Arizona, and California (Davis 1970). Among the 11 species of Pistacia genus, which comprises plants such as sumac, mango, cashew nut, and poison ivy, Pistacia vera (2n = 32) is economically the most important one and it is the only species in this genus which produces edible nuts large enough to be commercially most important (Barghchi and Alderson 1985; Carla Gentile et al. 2007; Choulak et al. 2017).

Pistacia vera L. tree, also called “Green Gold Tree” (Jannesar et al. 2020), is a long-lived tree up to 10 m high, has brownish green tiny flowers, tough leaves, and clusters of oblong fruits containing the pistachio nuts or seeds, with a wooden shell and a green or yellow kernel (Carla Gentile et al. 2007). In Tunisia, Pistacia vera L. tree is an important fruit crop, which appears to have been growing for a long time and increased over the last 20 years, particularly in the semi-arid areas due to its high-level tolerance to the drought conditions (Aouadi et al. 2019). Economically, Tunisia classifies eighth in the production of pistachio, with 3.637 tons in 2017 and the area of pistachio crops in Tunisia stands currently at 31.980 ha (Aouadi et al. 2019).

Pistacia vera L. is a unique deciduous and dioecious tree variety, meaning that female and male flowers are borne on two separate trees. Consequently, both female and male trees are necessary to produce nuts, and only the female trees produce the fruits. Thus, if we want to harvest fruits, we should plant one male tree of pistachio in the middle of every 7–9 female pistachio trees, to facilitate the spread of pollen through the air and wind. Male pistachio trees are usually higher and much more robust than female trees. The flowers are apetalous and include up to five sepals, the female flowers include a single superior ovary tricarpellate and the males have a five little stamens (Kashaninejad and Tabil 2011). The bees are not attracted to the female flowers since that their nectarine-free, but they attracted to the male flowers for the pollen. Thus, the pollen is scattered by the wind and the pistachios grow up on trees in grape-like clusters on first-year-old wood (Kashaninejad and Tabil 2011).

In the traditional medicine, Pistacia vera L. have been generally used to treat a various diseases such as periodontal disease, throat infections, blood clotting, peptic ulcer, renal stones, toothache, gastralgia, asthma, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and jaundice (Alma et al. 2004). Also, they are reported to have a numerous biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-atherogenic, and hypoglycemic activities (Demo et al. 1998; Duru et al. 2003; Kordali et al. 2003; Satil et al. 2003; Hamdan and Afifi 2004). Recently, some studies showed their antiviral activities including the anti-herpetic activity (Özçelik et al. 2005; Musarra-pizzo et al. 2020).

The herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are among the leading causes of diseases in the world. Especially, HSV-2 has been described to be a risky factor for human immunodeficiency virus infection, it has significantly increased and affected a significant challenge to public health owing to the growing problem of drug resistance. The anti-herpetic drug resistance crisis has been ascribed to the overuse of these medications, as well as the lack of new drug development by the pharmaceutical industry due to reduced economic inducements and challenging regulatory requirements. Moreover, due to the numerous secondary effects of these conventional drugs, the researchers turn to the plants and natural products as a source of new drugs with anti-HSV potential for the development of novel antiviral drugs against these infections and improving global combat against these infections because of their often-lower toxicity, poly-pharmacological activities, and biodegradability (Olivon et al. 2015).

Natural compounds are an important source of novel antiviral drugs. Some reports have previously shown a significant anti HSV activity of the extracts from different parts of Pistacia vera L. (seeds, stems, branches, shells, leaves, kernel) (Özçelik et al. 2005; Musarra-pizzo et al. 2020). However, to our knowledge, the antiviral bioactive compound has not been yet isolated and identified, and no study investigated the antiviral activity of this plant. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate for the first time the antiviral activity of Pistacia vera L. male floral bud extracts against herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), as well as to isolate and identify the active compound and investigate its mode of action. HSV-2 in an enveloped DNA virus responsible for a sexually transmitted disease mucosa causing lesions around the genital tract (Gupta et al. 2007) and induces a lifelong latent infection within sensory dorsal root ganglia (Wagner et al. 1988).

Materials and methods

Chemical and reagents

Methylcellulose and violet crystal were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide), ethanol, chloroform, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were from Scharlau, 35-mm dishes and 96-well tissue culture plates were from Orange Scientific, Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), Modified Eagle’s Medium (MEM) and Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) were from PAN Biotech, antibiotics–antimycotic (100 X) and trypsin–EDTA (10 X) were from Gibco BRL, Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) silica gel 60 F254 glass plate (20 × 20 cm; 60 Å) was from Silicycle. Gallic acid (> 99%), formic acid MS grade, and acetonitrile MS grade were purchased from Merck-Millipore, (Milan, Italy),

Plant material

The Pistacia vera L. male floral buds used in our study were collected in April 2019 from the region of ELGuettar-Gafsa (S 32° 09′ 22′′/W 52° 06′ 01′′) in the southwest of Tunisia. The botanical identification was accomplished by Dr. Asma EL Ayeb-Zakhama, in the Laboratory of Genetic, Biodiversity and Valorization of Bioresources (LR11ES41), Higher Institute of Biotechnology of Monastir, Tunisia. Then, a voucher specimen (P.v1) was deposited in the Laboratory of Interfaces and Advanced Materials (LR11ES55), Faculty of Sciences of Monastir, Tunisia for future reference.

Cells and viruses

The cell line used for cytotoxicity assay and virus culture was African green monkey kidney cell line (Vero) (ATCC® CCL-81™). This line was graciously provided by Pr. Hela Kallel (Laboratory of Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology, Vaccinology and Biotechnological Development, Pasteur Institute of Tunis, Tunisia). Vero cells were grown in MEM supplemented with 5% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and amphotericin B (25 μg/mL), and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The virus used for antiviral activity assay was HSV-2. The tested strain was a clinical isolate graciously provided by Mrs Ahlem Ben Yahia (Laboratory of Clinical Virology, Pasteur Institute of Tunis). HSV-2 was propagated on Vero cells in MEM supplemented with 2% FBS and containing antibiotics and antimycotic as reported above.

Plant extracts preparation

Pistacia vera L. male floral buds were dried at 45 °C in a forced convection laboratory oven until the stabilization of its weight and reduced to powder using a mill. A total of three extracts (ethanolic, aqueous, and polysaccharide extracts) were prepared to test their anti-HSV-2 activity.

Ten grams of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds powder was weighed accurately, and three kinds of the extract were prepared separately. For the two first extract, vegetable matters were defatted by chloroform in Soxhlet apparatus. Then, the defatted residues were separately macerated in ethanol (96%) and distilled water, at room temperature two times, every 24 h the solvent is removed. Following the filtration, ethanol, and aqueous extracts were concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at 40 °C to yield crude extracts were named EE-Pis and AE-Pis, respectively, for the ethanolic and aqueous extracts. Second, for obtaining the polysaccharide extract, the extraction was performed using hot deionized water for 2 h under mechanical stirring. After extraction, the mixture obtained was filtered and then centrifuged (3500 rpm for 15 min). Then, it was precipitated with three volumes of ethanol (96%) and kept 12 h at around 4 °C. The resulting precipitate was dissolved in deionized water and blended with Sevag reagent to eliminate proteins (Mzoughi et al. 2018). Thereafter, the aqueous phase was dialyzed against deionized water (for 3 days at 4 °C) via dialysis membrane (cut-off 14 kDa). Finally, the dialysate was lyophilized to provide fraction P-Pis.

Yield (%) of each extract was determined using the following equation:

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the tested extracts on Vero cells was performed by the MTT assay, as reported by Mosmann (1983) with minor modifications. Briefly, a serial twofold dilution of samples was deposed in 96-well plates containing 104 cells. MEM without plant extract was used as negative control. After 72 h of incubation at 37 °C, the medium was replaced by the MTT solution (2 mg/mL in PBS), and the plates were further incubated for 4 h. The MTT solution was removed and the formed formazan crystals were dissolved using DMSO. The optical densities were read in a reader plate at 540 nm. The extract concentration required to reduce cell viability by 50% (CC50) was estimated by linear regression analysis based on the data obtained from concentration–response curves.

Antiviral activity assay

The evaluation of the anti HSV-2 activity of the tested extracts on Vero cells was performed by the plaque number reduction assay, as reported by Kanekiyo et al. (2007) with minor modifications. Briefly, a serial twofold dilution of samples from the CC50/2 was deposed with 200 plaque-forming units (PFU) of HSV-2 in 35 mm dishes containing confluent cells. After 1-h virus penetration, the extracts were removed and replaced with the same dilutions added with 1% methyl cellulose. MEM without plant extract was used as positive control. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, the medium was removed, and the viral plaques were visualized by staining with 0.1% violet crystal solution and then counted using a stereomicroscope. The extract concentration required to reduce plaque number by 50% (IC50) was estimated by linear regression analysis based on data obtained from concentration–response curves. The selectivity index (SI) was calculated by the ratio of CC50 to IC50. We estimated extract has activity when its SI was > 10.

Pretreatment of cells assay

Confluent cells were treated with the active extracts (10 × IC50) for 2 h at 37 °C. After washing with PBS to eliminate free compounds, cells were infected with 200 PFU of HSV-2 for 1 h. After washing with PBS to eliminate unbound viruses, MEM was added. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentages of viral inhibition were calculated compared with that of the virus control.

Virus entry inhibition assay

Confluent cells were simultaneously infected with 200 PFU of HSV-2 and treated with the active extracts (10 × IC50) for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing with PBS to eliminate both free compounds and unbound viruses, MEM was added. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentages of viral inhibition were calculated compared with that of the virus control.

Viral post-infection inhibition assay

Confluent cells were infected with 200 PFU of HSV-2 for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing with PBS to eliminate unbound viruses, cells were treated with the active extracts (10 × IC50) for 6 h at 37 °C. After washing with PBS to eliminate free compounds, MEM was added. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentages of viral inhibition were calculated compared with that of the virus control.

Viral cycle inhibition assay

Confluent cells were treated with the active extracts (10 × IC50) for 9 h at 37 °C including the steps before, during and after viral infection (2, 1, and 6 h, respectively). Cells were infected with 200 PFU of HSV-2 for 1 h at 37 °C during the viral infection step. Cells were washed with PBS between the different steps to eliminate both free compounds and/or unbound viruses. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentage of viral inhibition was calculated comparing with that of the virus control.

Virucidal assay

Active extracts (10 × IC50) were incubated with 20.000 PFU of HSV-2 for 2 h at 37 °C. Then, the mixture was diluted 100-fold to remove the effect of the active extracts on virus replication and then added to confluent cells. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentage of viral inhibition was calculated compared with that of the virus control.

Dose–response virucidal assay

A serial twofold dilution of the active extracts from 10 × IC50 was incubated with 20.000 PFU of HSV-2 for 2 h at 37 °C. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentage of viral inhibition was calculated compared with that of the virus control. The concentration of samples required to reduce plaque number by 50% (VC50) was estimated by linear regression analysis based on data obtained from concentration–response curves. Virucidal activity was evaluated by the determination of the selectivity index (SIv) calculated by the ratio of CC50 to VC50.

Time-course virucidal assay

Three dilutions of the active extracts (10 × IC50, 2 × IC50 and IC50) were incubated with 20.000 PFU of HSV-2 for different contact times at 37 °C. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, plaque number was counted as previously described and the percentage of viral inhibition was calculated comparing with that of the virus control.

Isolation of the active compound

To isolate the active compound, the active extract (AE-Pis) was subjected to a Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) using a combination of solvents. After visualization under UV at 254 nm, the obtained bands were scraped off dissolved in ethanol and filtered. After evaporating solvent, the dried products were weighted and dissolved in 75% ethanol to a concentration of 10 mg/mL to evaluate their antiviral activity. A second separation of this band using the same mobile phase system with changes in the proportion of the used solvents was performed for detecting impurities.

Identification of the active compound

The separation was achieved using an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity II analytical HPLC with reverse-phase column type Beckman-Ultrasphere ODS 5u C18 (4.6 mm × 25 cm). The system is controlled by the software “Agilent Open Lab ChemStation”. The detector (DAD) is adjusted to a scanning range of 200–400 nm and the temperature of the column is maintained at 23 °C. The mobile phase used consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) at 0.3 mL/min (injected volume of 5 µL). The linear solvent gradient used is as follows: 0–5 min, 0–20% B; 5–10 min, 20–30% B; 10–15 min, 30–50% B; 15–20 min, 50–70% B; 20–25 min, 70–90% B; 25–30 min, 90–50% B; 30–35 min, 50–10% B. Chromatograms were registered at 254 nm. The ion trap operated in a data-dependent, full scan (60–1500 m/z), and MSn mode to obtain fragment ions m/z with a collision energy of 33% and an isolation width of 3 m/z. The positive parameters of the ion mode ESI source have been optimized to an ionization voltage of 3.5 kV, a capillary temperature of 330 °C, a capillary voltage of 30 V, a sheath gas flow rate of 40 arbitrary units (AU), and an auxiliary gas flow rate of 18 AU.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were carried out in triplicate and values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments.

Results

Cytotoxicity and anti HSV-2 activity of of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds extracts

The yields of extraction were 13.20%, 28.07%, and 26.69%, respectively, for EE-Pis, AE-Pis, and P-Pis. The cytotoxicity results of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds extracts on Vero cells were shown in the Table 1. EE-Pis was the most cytotoxic extract as it exhibited the lowest CC50, while P-Pis and AE-Pis extracts showed a less cytotoxicity (CC50 > 1 mg/mL). AE-Pis and P-Pis extracts showed an antiviral activity against HSV-2 because their selectivity index (SI) was > 10. However, the EE-Pis extract did not exhibit anti HSV-2 activity. Furthermore, the antiviral activity of AE-Pis was slightly higher than that of P-Pis (SI = 29.12 vs 20.25, respectively).

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity and anti HSV-2 activity of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds extracts and gallic acid standard compound

| Extracts | CC50 (µg/mL) | IC50 (µg/mL) | SI = CC50/IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| EE-Pis | 112 ± 12.41 | 64.29 ± 5.53 | 1.74 |

| AE-Pis | 1424 ± 86.14 | 48.89 ± 3.67 | 29.12 |

| P-Pis | 2633 ± 241.22 | 130.60 ± 14.38 | 20.25 |

| Gallic acid | 260 ± 36.25 | 75.69 ± 12.74 | 3.44 |

HSV-2 was grown on Vero cells, CC50 and IC50 values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments

CC50 Cytotoxic Concentration 50%, IC50 Inhibitory Concentration 50%, SI Selectivity Index

Mode of anti HSV-2 action of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds active extracts

The two active extracts, AE-Pis and P-Pis showed a virucidal activity against HSV-2 with 100% of viral inhibition at a concentration of 10 × IC50 after two hours contact (Fig. 1). In addition, due to the inhibition of the virus by direct contact, these two extracts showed low viral inhibition (21.46 and 18.45%, respectively) at this same concentration during the virus entry step. Furthermore, at this concentration, AE-Pis and P-Pis extracts showed better activity by direct contact with HSV-2 for 2 h than they showed on cell culture during a viral cycle step for 9 h (100% vs. 89.68 and 83.09%, respectively). In addition, at a concentration of 10 × IC50, AE-Pis and P-Pis extracts completely inhibited HSV-2 at a concentration of 2 × IC50 after 1 h of contact (Fig. 2). However, these extracts completely inhibited HSV-2 replication after 5 h of contact. The virucidal concentration 50% (VC50) was 36.37 ± 4.06 and 82.04 ± 6.31 µg/mL, giving a virucidal selectivity index (SIv) of 39.15 and 32.09 for AE-Pis and P-Pis, respectively. Their VC50 decreased compared to their IC50 (36.37 vs 48.89 and 82.04 vs 130.60 µg/mL for AE-Pis and P-Pis, respectively). The increase in their SI showed that these two active extracts showed greater activity when they are in direct contact with HSV-2 for 2 h than when acting for 48 h in the antiviral activity test. Nevertheless, these two extracts showed no activity when added before or after virus inoculation.

Fig. 1.

Mode of anti-HSV-2 action of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds active extracts

Fig. 2.

Effect of time course on HSV-2 inhibition by direct contact with Pistacia vera L. male floral buds active extracts

Isolation of the active compound

The active extracts that demonstrated the highest antiviral activity (AE-Pis) was separated using TLC. A total of 86 mg of AE-Pis were deposed on a pre-coated silica gel 60 F254 and migrated using butanol/water/formic acid/acetic acid in the ratio 4:1:0.25:0.25–v/v/v/v as mobile phase. This separation yielded six bands (Fig. 3a). The evaluation of their anti HSV-2 activity showed that only one fraction exhibited activity. The active band has the following characteristics: dark under white light, blue color under UV light, retention factor = 0.95, mass ≈ 10.4 mg (Fig. 3a and b). A second separation of this band with changes in the proportion of the used solvents (butanol/water/formic acid/acetic acid in the ratio 4:0.5:0.25:0.25) revealed no impurities.

Fig. 3.

TLC profile of Pistacia vera L. male floral buds aqueous extract (a) and of gallic acid (b)

Identification of the active compound

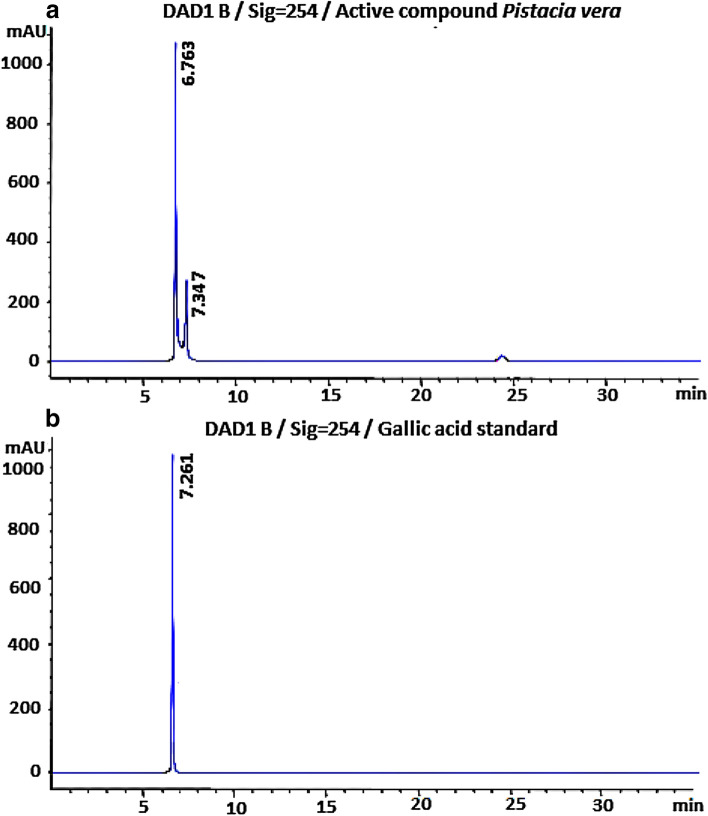

The chromatographic analysis of the active fraction showed the presence of two peaks at 6.76 and 7.34 min at 254 nm UV wavelength (Fig. 4). Each peak was recovered for the evaluation of their antiviral activity. Only the fraction eluted at 6.76 min demonstrated significant activity. Total ion chromatogram (Fig. 5a) registered in the negative ionization mode indicated the presence of one compound which had 170 molecular mass and fragmented by losing the carboxylic group giving ions at [M-H-44]-. This compound was identified as gallic acid and its chemical structure was confirmed by analyzing the pure standard commercial compound under identical experimental conditions. These data were confirmed by performing the MSn of the standard compound (Fig. 5b) which showed similar profile. The chemical formula of gallic acid is C7H6O5 and its chemical structure is illustrated in this figure.

Fig. 4.

Total ion chromatogram at 254 nm UV wavelength of the active compound isolated from Pistacia vera L. male floral buds aqueous extract (a) and of the standard compound (gallic acid) (b)

Fig. 5.

MS/MS spectrum of the active compound isolated from Pistacia vera L. male floral buds aqueous extracts (a) and of the standard compound (gallic acid) (b) registered in negative ionization mode

Cytotoxicity and anti HSV-2 activity of the active compound

Gallic acid standard was evaluated for both cytotoxicity and anti HSV-2 activity (Table 1). It showed a CC50 = 260 µg/mL and IC50 = 75.69 µg/mL giving a SI = 3.44. If its IC50 is not much different to that of the active extract from which it was isolated (75.69 µg/mL versus 48.49 µg/mL), however, its cytotoxic action on Vero cells is more important (260 µg/mL versus 1424 µg/mL), which generated a decrease of the SI (3.44 versus 29.12).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the anti-HSV-2 activity of Pistacia vera from male flower buds. The antiviral activity of this plant had already been found in previous studies against HSV-1 and Parainfluenza viruses (PIV) but from other organs (seeds, stems, branches, shells, leaves, kernel) (Özçelik et al. 2005; Musarra-pizzo et al. 2020). However, the main difference is that in our study, the active extracts are the aqueous and polysaccharide extracts, whereas the active extracts were the polyphenol-rich and lipophylic extracts in the study of Musarra-Pizzo et al. (2020) and Özçelik et al. (2005), respectively. Moreover, the lipophylic extracts obtained from different Pistacia vera organs in the study of Özçelik et al. showed activity against both HSV and PIV; however, these authors did not calculate the selectivity index of the active extracts to establish a comparison with our results. Regarding the study of Musarra-Pizzo et al., the selectivity index (SI = 3) of the polyphenol-rich extract obtained from pistachio kernels was very low to consider it active against HSV-1. In our study, we also found a low selectivity index in the ethanolic extract of male flower buds (SI = 1.74), so we did not consider it as active. Indeed, it is commonly accepted that an extract would preferably be considered as active if its selectivity index is higher than 10 to keep a safety zone with respect to the limit of toxicity. Nevertheless, the aqueous and polysaccharide extracts isolated from male flower buds exhibited a selectivity index of 29.12 and 20.25, respectively. These two extracts also showed a low cytotoxicity (CC50 < 1 mg/mL) compared with the ethanolic extract (CC50 = 112 µg/mL), which explains their “acceptance” as active extracts, although the IC50 of the ethanolic extract was close to that of the two other extracts and even lower than that of the polysaccharide extract.

The aqueous and polysaccharide extracts showed virucidal activity against HSV-2, they demonstrated a virucidal activity probably by altering the viral membrane or by interacting with viral ligands, which inhibited their binding to receptors on target cells. Nevertheless, the study of Musarra-Pizzo et al. (2020) demonstrated that the polyphenol-rich extract obtained from pistachio kernels reduced the expression of viral proteins. In addition, we also showed that the active extract weakly inhibited virus entry during attachment and/or penetration into cells. We can speculate that the inhibition of virus entry could be due to the interaction between the virus ligands and the active compound which would prevent the virus from interacting with the cell receptors. Therefore, further research is required to verify the underlying antiviral mechanisms involved in these inhibitions, such as the nature of the viral attachment glycoproteins and the cellular receptors implicated in this inhibition to confirm our preliminary results.

The bioactive compound responsible for the anti HSV-2 was identified as gallic acid. This molecule, also named 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid is a colorless or slightly yellow crystalline compound that is one of the most abundant ethanolic acids in the plant and widely distributed in vegetables and fruits (Choubey et al. 2015; Kahkeshani et al. 2019). It has a good antioxidant potential (Hugo et al. 2012) and demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects (Kroes et al. 1992; Yoshioka et al. 2000; Veluri et al. 2006; Chia et al. 2010; Verma et al. 2013). Its antiviral activities have also been shown against HSV-1 and -2 (Savi et al. 2005; Müller Kratz et al. 2008; Kratz et al. 2008), as well as against rhinovirus (Choi et al. 2010). Kratz et al. (2008) found that gallic acid inhibited HSV-1 attachment and penetration into cells Müller Kratz et al. (2008) and Choi et al. (2010) demonstrated that this compound interacts or activates directly on rhinovirus particles (Choi et al. 2010), which is in agreement with the results on the mode of antiviral action we found in this study.

We tested the cytotoxicity and the antiviral activity of the gallic acid standard compound. This molecule demonstrated a low selectivity index compared to the active extract from which it was isolated (aqueous extract) (SI = 3.44 versus 29.12). By the way, Vilhelmova-Ilieva et al. (2019) did not find a significant antiviral activity against HSV-1 (Vilhelmova-Ilieva et al. 2019). Certainly, if one were to choose a candidate as a complement or alternative to the usual antivirals, the aqueous extract would be clearly preferred. The higher activity of the active extract compared to the active compound could be explained by synergy phenomena with other molecules present in the active extract which would have amplified the antiviral activity of the gallic acid.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first study which the bioactive compound has been isolated from Pistacia vera L. for its antiviral activity. Since the active compound (gallic acid), which has been previously described as having antiviral activity, did not show interesting results in our study. The aqueous extract prepared from male flower buds of Pistacia vera L. could be considered as a promising therapeutic source for treating herpetic infections, due to its low cytotoxicity and high selectivity index.

Abbreviations

- HSV-1

Herpes Simplex Virus type 1

- HSV-2

Herpes Simplex Virus type 2

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- EE-Pis

Ethanolic extract from Pistacia vera L. male floral buds

- AE-Pis

Aqueous extract from Pistacia vera L. male floral buds

- P-Pis

Polysaccharide from Pistacia vera L. male floral buds

- TLC

Thin-Layer Chromatography

- PFU

Plaque Forming Unit

- CC50

50% Cytotoxic Concentration

- IC50

50% Inhibitory Concentration

- VC50

50% Virucidal concentration

- SI

Selectivity Index

- HPLC–DAD–ESI-MSn

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Diode Array Detection coupled with Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or other competing interests.

References

- Alma MH, Nitz S, Kollmannsberger H, et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils from the gum of Turkish Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:3911–3914. doi: 10.1021/jf040014e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aouadi M, Guenni K, Abdallah D, et al. Conserved DNA-derived polymorphism, new markers for genetic diversity analysis of Tunisian Pistacia vera L. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2019;25:1211–1223. doi: 10.1007/s12298-019-00690-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barghchi M, Alderson PG. In vitro propagation of Pistacia vera L. and the commercial cultivars Ohadi and Kalleghochi. J Horticult Sci. 1985;60:423–430. doi: 10.1080/14620316.1985.11515647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chia YC, Rajbanshi R, Calhoun C, Chiu RH. Anti-Neoplastic effects of gallic acid, a major component of toona sinensis leaf extract, on oral squamous carcinoma cells. Molecules. 2010;15:8377–8389. doi: 10.3390/molecules15118377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Song JH, Bhatt LR, Baek SH. Anti-human rhinovirus activity of gallic acid possessing antioxidant capacity. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1292–1296. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choubey S, Varughese LR, Kumar V, Beniwal V. Medicinal importance of gallic acid and its ester derivatives: a patent review. Pharmaceutical Patent Analyst. 2015;4:305–315. doi: 10.4155/ppa.15.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choulak S, Chatti K, Marzouk Z, Chatti N. Genetic differentiation and gene flow of some Tunisian pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) varieties using chloroplastic DNA. J Res Biol Sci. 2017;2:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Davis PH. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Demo A, Petrakis C, Kefalas P, Boskou D. Nutrient antioxidants in some herbs and Mediterranean plant leaves. Food Res Int. 1998;31:351–354. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(98)00086-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duru ME, Cakir A, Kordali S, et al. Chemical composition and antifungal properties of essential oils of three Pistacia species. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:170–176. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile C, Tesoriere L, Butera D, et al. Antioxidant activity of Sicilian pistachio (Pistacia vera L. Var. Bronte) nut extract and its bioactive components. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:643–648. doi: 10.1021/jf062533i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370:2127–2137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61908-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan II, Afifi FU. Studies on the in vitro and in vivo hypoglycemic activities of some medicinal plants used in treatment of diabetes in Jordanian traditional medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo PC, Gil-Chávez J, Sotelo-Mundo RR, et al. Antioxidant interactions between major phenolic compounds found in “Ataulfo” mango pulp: chlorogenic, gallic, protocatechuic and vanillic acids. Molecules. 2012;17:12657–12664. doi: 10.3390/molecules171112657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannesar M, Seyedi SM, Moazzam Jazi M, et al. A genome-wide identification, characterization and functional analysis of salt-related long non-coding RNAs in non-model plant Pistacia vera L. using transcriptome high throughput sequencing. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–23. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62108-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahkeshani N, Farzaei F, Fotouhi M, et al. Pharmacological effects of gallic acid in health and disease: a mechanistic review. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2019;22:225–237. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2019.32806.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekiyo K, Hayashi K, Takenaka H, et al. Anti-herpes simplex virus target of an acidic polysaccharide, nostoflan, from the edible blue-green alga Nostoc flagelliforme. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1573–1575. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashaninejad M, Tabil LG. Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) postharvest biology and technology of tropical and subtropical fruits a volume in woodhead publishing series in food science. Technol Nutr. 2011;247:218–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kordali S, Cakir A, Zengin H, Duru ME. Antifungal activities of the leaves of three Pistacia species grown in Turkey. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:164–167. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz JM, Andrighetti-Fröhner CR, Leal PC, et al. Evaluation of anti-HSV-2 activity of gallic acid and pentyl gallate. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:903–907. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes BH, Van Den Berg AJJ, Quarles Van Ufford HC, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of gallic acid. Planta Med. 1992;58:499–504. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller Kratz J, Regina Andrighetti-Fröhner C, Juliana Kolling D, et al. Anti-HSV-1 and anti-HIV-1 activity of gallic acid and pentyl gallate. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz Rio De Janeiro. 2008;103:437–442. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762008000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musarra-pizzo M, Pennisi R, Ben-amor I, et al. In vitro anti-HSV-1 activity of polyphenol-rich extracts and pure polyphenol compounds derived from pistachios kernels (Pistacia vera L.) Plants. 2020;9:267–278. doi: 10.3390/plants9020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mzoughi Z, Abdelhamid A, Rihouey C, et al. Optimized extraction of pectin-like polysaccharide from Suaeda fruticosa leaves: characterization, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities. Carbohyd Polym. 2018;185:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivon F, Palenzuela H, Girard-Valenciennes E, et al. Antiviral activity of Flexibilane and Tigliane diterpenoids from Stillingia Lineata. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:1119–1128. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçelik B, Aslan M, Orhan I, Karaoglu T. Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities of the lipophylic extracts of Pistacia vera. Microbiol Res. 2005;160:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satil F, Azcan N, Baser KHC. Fatty acid composition of pistachio nuts in Turkey. Chem Nat Compd. 2003;39:322–324. doi: 10.1023/B:CONC.0000003408.63300.b5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savi LA, Leal PC, Vieira TO, et al. Evaluation of anti-herpetic and antioxidant activities, and cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of synthetic alkyl-esters of gallic acid. Arzneimittel-Forschung/drug Res. 2005;55:66–75. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonmezdag AS, Kelebek H, Selli S. Characterization and comparative evaluation of volatile, phenolic and antioxidant properties of pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) hull. J Essent Oil Res. 2017;29:262–270. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2016.1216899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaino A, Martorana M, Arcoraci T, et al. Antioxidant activity and phenolic profile of pistachio (Pistacia vera L., variety Bronte) seeds and skins. Biochimie. 2010;92:1115–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veluri R, Singh RP, Liu Z, et al. Fractionation of grape seed extract and identification of gallic acid as one of the major active constituents causing growth inhibition and apoptotic death of DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1445–1453. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Singh A, Mishra A. Gallic acid: molecular rival of cancer. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;35:473–485. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva N, Jacquet R, Deffieux D, et al. Anti-herpes simplex virus type 1 activity of specially selected groups of Tannins. Drug Research. 2019;69:374–381. doi: 10.1055/a-0640-2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EK, Flanagan WM, Devi-Rao G, et al. The herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is spliced during the latent phase of infection. J Virol. 1988;62:4577–4585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4577-4585.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka K, Kataoka T, Hayashi T, et al. Induction of apoptosis by gallic acid in human stomach cancer KATO III and colon adenocarcinoma COLO 205 cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:1221–1223. doi: 10.3892/or.7.6.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]