Abstract

Purpose

Evaluate the frequency of benign versus malignant masses within the prestyloid parapharyngeal space (PPS) and determine if tumor margins on preoperative cross-sectional imaging can predict malignancy status.

Materials and Methods

The electronic health record at UC Davis Medical Center was searched for PPS masses surgically resected between 2015 and 2021. Cases located centrally within the prestyloid PPS with confirmed histologic diagnosis were included and separated into either benign or malignant groups. Margins of the tumors were categorized as “well defined” or “infiltrative” on preoperative cross-sectional imaging. Statistical analysis was performed to evaluate relationships between malignancy status and tumor margins.

Results

A total of 31 cases met the inclusion criteria. Fourteen separate histologic diagnoses were observed. Benign cases comprised 77% (24/31) and the remaining 23% (7/31) were malignant. Pleomorphic adenoma was the most common overall diagnosis at 48% (15/31). Adenoid cystic carcinoma 6% (2/31) was the most common malignant diagnosis. Well-defined tumor margins were seen in 81% (25/31) of cases. A benign diagnosis was found in 96% (24/25) of the cases with well-defined margins. Infiltrative tumor margins were displayed in 19% (6/31) of cases, all were malignant. The sensitivity and specificity of infiltrative tumor margins for malignancy were 85.7% and 100%, respectively. The negative predictive value of infiltrative margins for malignancy was 96%.

Conclusion

Infiltrative tumor margins on preoperative imaging demonstrate high specificity and negative predictive value for malignant histology in prestyloid PPS masses. Margins should therefore be considered when determining clinical management for newly diagnosed PPS tumors.

Keywords: Parapharyngeal space, PPS tumors, prestyloid PPS, infiltrative margins

Introduction

Primary masses of the parapharyngeal space (PPS) comprise 0.5% of head and neck neoplasms. 1 The rarity of primary PPS tumors is largely due to the limited number of anatomical structures native to the space. It is primarily composed of fat, though other components including minor salivary glands, branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, and minor vasculature structures have been described as well. 1 Anatomically, the PPS forms an inverted pyramid on either side of the pharynx extending from the skull base to the hyoid bone. 2 It is bordered by the parapharyngeal mucosal space medially, masticator space anteriorly, parotid space laterally, and posteriorly by the carotid space and the lateral retropharyngeal spaces.1,3,4,5 Masses arising from these adjacent spaces occur more frequently than primary tumors and often extend into the PPS producing a predictable pattern of fat displacement commonly used for localizing neck masses. 6

Approximately 80% of PPS masses are benign and most are derived from salivary tissue, with pleomorphic adenoma representing the majority of cases.7–12 Malignant tumors account for about 20% of cases, with adenocarcinomas and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma being most commonly reported.1,13 Of the benign cases, approximately a quarter are clinically asymptomatic and are potential candidates for observation. 13 Unfortunately, determination of malignancy status by biopsy can be technically challenging due to limited percutaneous accessibility to the PPS and most cases are identified post-operatively. Accurate distinction between malignant and benign entities on cross-sectional imaging has the potential to influence patient care by identifying candidates for surveillance. Reports in the literature have correlated malignancy status with the appearance of tumor margins in neck masses located outside the parapharyngeal space.14–17 There are no published studies evaluating tumor margins in PPS masses as a predictive tool for determining malignant versus benign pathology. The purpose of this study is to evaluate tumor margins of prestyloid PPS masses and evaluate their predictive value of malignancy status on pre-operative imaging (Figure 1).

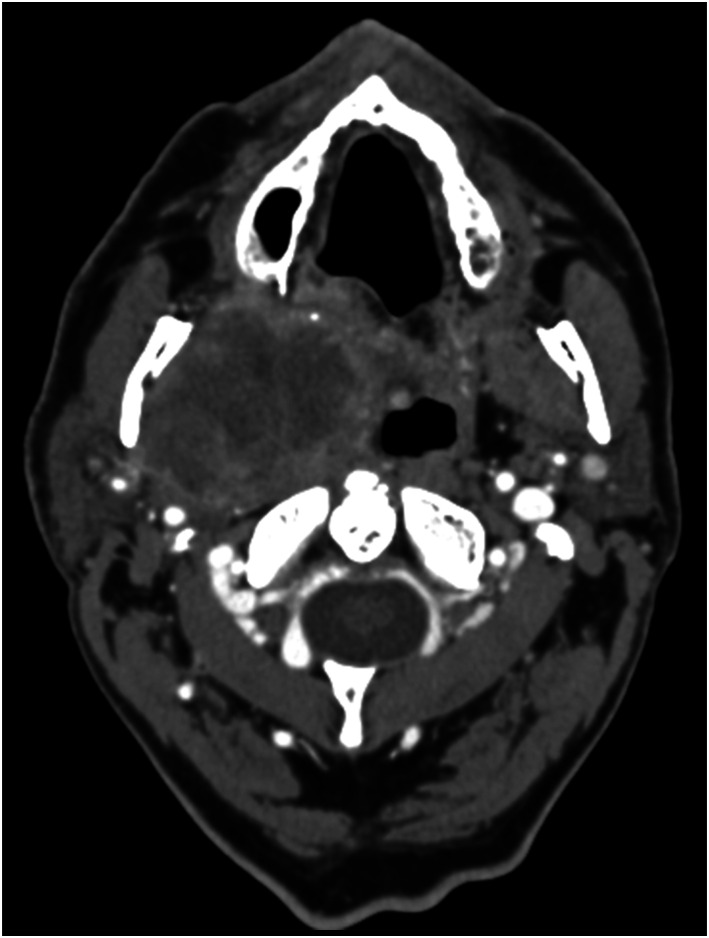

Figure 1.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT images of the right PPS in a 64-year-old male at the level of the maxillary sinuses show an infiltrative mass with irregular enhancing borders. The mass extends into the surrounding spaces of the neck. Surgical pathology revealed carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this retrospective study with a waiver of informed consent. The UC Davis Surgical database was searched for parapharyngeal masses that were surgically resected between 2015 and 2021. To be included in the study, cases needed a pathologically confirmed diagnosis and needed to be localized to the parapharyngeal space on pre-operative CT or MRI. Tumors originating in any of the nearby spaces with secondary extension into the prestyloid PPS were excluded. Radiologic criteria for localizing a mass to the PPS were determined by evaluating the directionality of PPS fat displacement. Tumors located primarily within the prestyloid PPS space were considered primary PPS lesions and included in this study. All cases were reviewed by two neuroradiologists. If lesions displaced the PPS fat, then they were deemed to originate from other spaces within the neck. Lateral displacement was attributed to parapharyngeal mucosal space lesions, medial to parotid space lesions, anterior to carotid space lesions, posterior to masticator space lesions, and anterolateral to retropharyngeal space lesions. Data on patient demographics, histological diagnosis, and malignancy status were obtained. Tumor histology was grouped into two categories: benign and malignant. Tumor margins were evaluated on pre-operative cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) and categorized as well-defined (smooth, lobulated) or infiltrative (poorly defined, irregular tumor margins). Both CT and MRI have excellent soft tissue contrast and allow adequate visualization of tumor borders. We defined tumor boarders on MRI, and used CT when MRI was unavailable. We also collected T1 (low, high signal), T2 (low, intermediate, high, or mixed) signal characteristics and ADC values for tumors that had available MRI. Two neuroradiologists independently evaluated tumor margins, blinded to the final histologic analysis. Inter-reader agreement for tumor margins was calculated between two board-certified neuroradiologists, and any differences resolved by a consensus. Tumor margins were correlated with the presence of benign or malignant histology. A Fisher exact test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between malignancy status and irregularity of tumor margins (Figure 2).

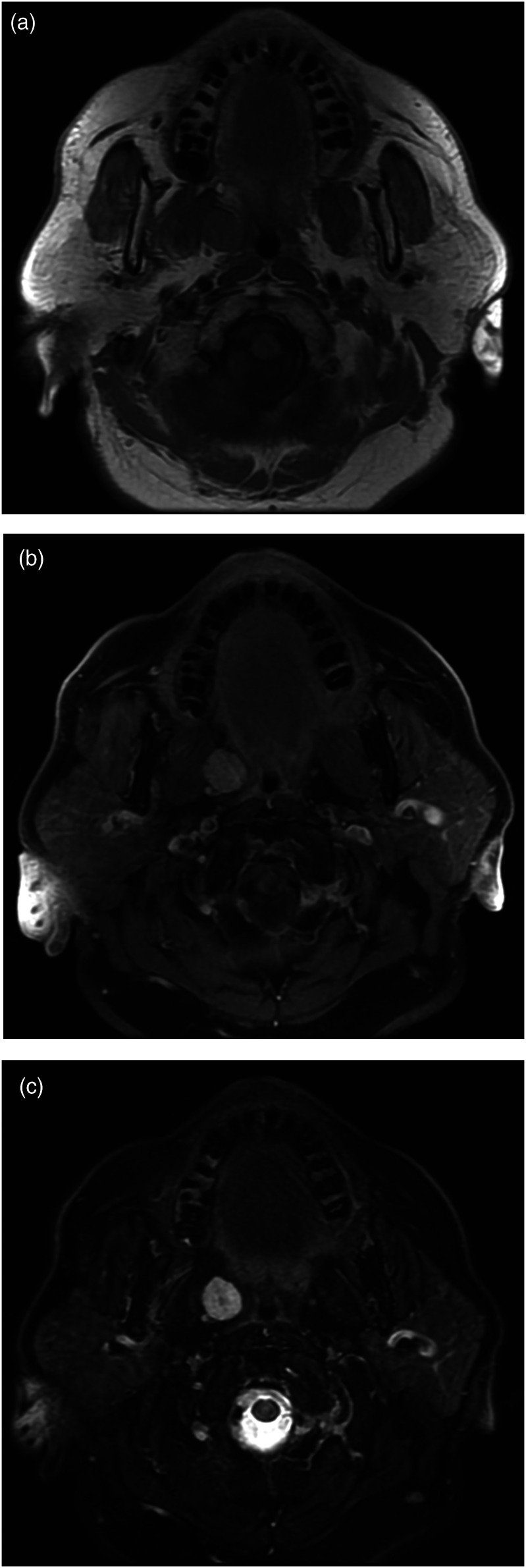

Figure 2.

MRI through the right PPS in a 66-year-old female with path-proven hemangioma. Axial T1 weighted pre- (a) and (b) post-gadolinium images demonstrate a well-circumscribed smooth bordered mass in the right PPS with uniform enhancement. (c) Axial T2 weighted image showing a well-defined hypertense mass in the PSS without extension into adjacent spaces.

Results

A total of 31 patients met inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the study. The median age of included patients was 53.6 years (range 4–76 years) and 68% of the cases were female. Twelve separate histologic diagnoses were observed and are displayed in Table 1. Of these, 23% (7/31) were malignant and included: adenoid cystic carcinoma 6.5% (2/31), carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma 3.2% (1/31), acinic cell carcinoma 3.2% (1/31), giant cell fibroblastoma 3.2% (1/31), and a low-grade malignant neuroendocrine tumor 3.2% (1/31). A benign diagnosis was present in 77% of cases and included: pleomorphic adenoma 48.4% (15/31), hemangioma 9.7% (3/31), lipoma 6.5% (2/31), schwannoma 6.5% (2/31), basal cell adenoma 3.2% (1/31), hemangiopericytoma 3.2% (1/31), and reactive lymph node 3.2% (1/31) (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Pathological findings of the PPS masses.

| Histologic diagnosis | Percentage of total cases | Malignancy status |

|---|---|---|

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 48.4% (15/31) | Benign |

| Hemangioma | 9.6% (3/31) | Benign |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 6.5% (2/31) | Malignant |

| Schwannoma | 6.5% (2/31) | Benign |

| Lipoma | 6.5% (2/31) | Benign |

| Acinic cell carcinoma | 3.2% (1/31) | Malignant |

| Basal cell adenoma | 3.2% (1/31) | Benign |

| Giant cell fibroblastoma | 3.2% (1/31) | Malignant |

| Hemangiopericytoma | 3.2% (1/31) | Benign |

| Reactive lymph nodes | 3.2% (1/31) | Benign |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 3.2% (1/31) | Malignant |

| Low-grade neuroendocrine tumor | 3.2% (1/31) | Malignant |

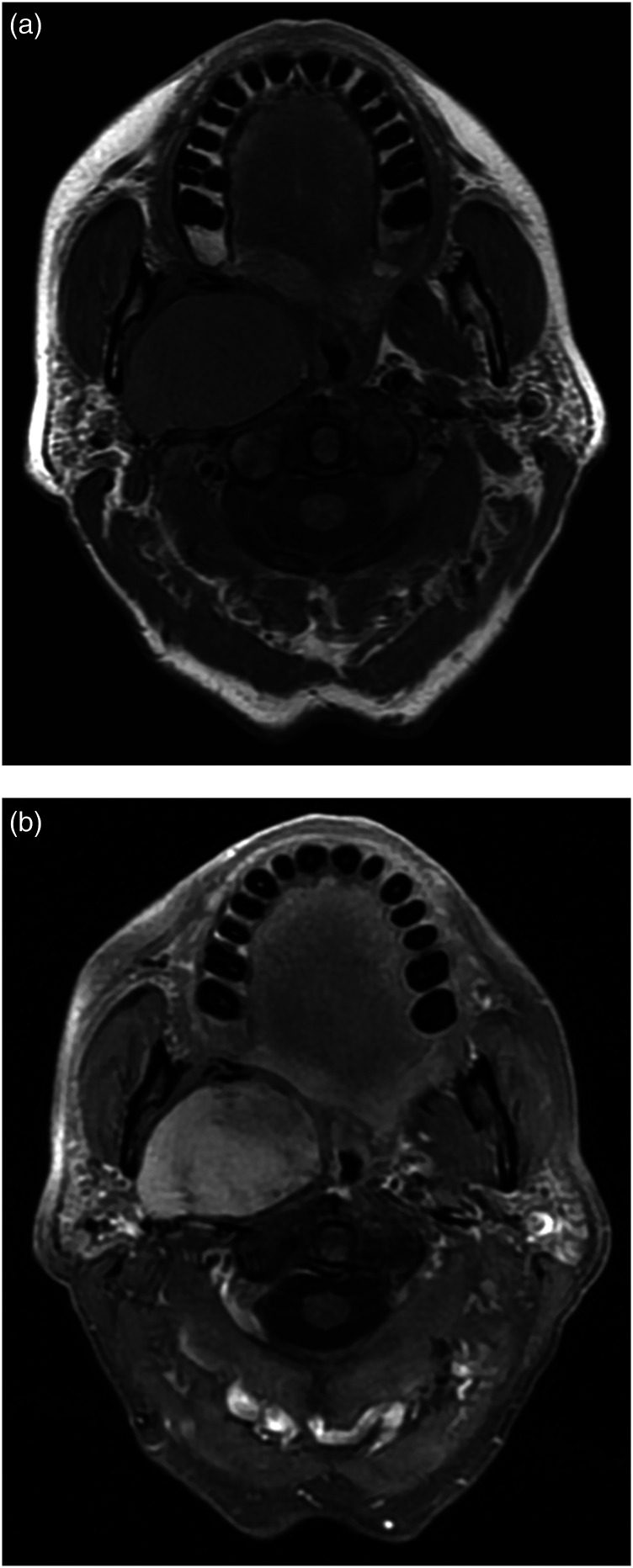

Figure 3.

MRI through the right PPS in a 65-year-old female with path-proven pleomorphic adenoma. Axial (a) T1 pre- and (b) post-contrast fat-saturated images showing a large enhancing mass with smooth borders compressing adjacent spaces without infiltration.

Included cases were evaluated preoperatively via MRI 84% of the time (26/31) and by CT for the remaining 16% (5/31). Cross-sectional imaging demonstrated smooth peripheral tumor margins in 81% (25/31) of cases. All but one of these cases, acinic cell carcinoma, was found to be benign. Irregular and infiltrative tumor margins were displayed in 19% (6/31) of cases and all had malignant histology. Malignant histologic diagnosis and infiltrative tumor margins are dependent variables as demonstrated by a Fisher exact test statistic of 1 × 10−5 (p < 0.05). Irregular tumor margins had a sensitivity of 85.7% and specificity of 100% for a malignant diagnosis within the prestyloid PPS, with PPV of 100% and NPV 96%. Inter-reader agreement for tumor margins showed 96.8% agreement (Cohen’s K 0.89).

MRI was available in five of the seven malignant tumors. ADC values were available in 18 cases and were not helpful in distinguishing benign from malignant histology; three cases with malignant histology had ADC values of 1067, 1439, 2205 × 10−3 mm2/s; 15 with benign histology had ADC values between 751 to 2390 × 10−3 mm2/s. T1 signal of the tumor was high in three cases, all of which had benign histology; all malignant tumors had low T1 signal. T2 signal characteristics of the tumor were not helpful in distinguishing benign from malignant histology. Two malignant tumors had high, two had mixed, and one had low T2 signal characteristics. Fourteen benign tumors had high, four had intermediate, and three had mixed T2 signal characteristics. Examples of tumor margins and accompanying pathologies are included in Figures 1 – 3.

Discussion

Our results indicate that tumor margins on cross-sectional imaging can be a useful tool in predicting malignancy status for prestyloid PPS masses. Infiltrative margins were found to demonstrate a high specificity and negative predictive value when assessing for malignancy within the space. Tumor ADC and T2 values demonstrated little utility in distinguishing benign from malignant PPS pathologies, although our study had lower power to evaluate these two variables. High T1 signal, when present, appeared to be associated with benign etiologies as it was only demonstrated in benign tumors, though only in a few cases. These findings are in line with the published literature on salivary gland tumors.18–20

The proportion of benign and malignant masses found in this study was consistent with those previously reported in the literature. However, our investigation shed some light on masses found specifically within the prestyloid PPS. Most published data on these tumors included masses from adjacent spaces (poststyloid/carotid space).7,8,21,22 Despite the prestyloid component being predominantly composed of fat, we identified a total of 12 distinct histological diagnoses within the space. Fewer neurogenic tumors were demonstrated in our results compared to those with a more broadly defined PPS. 7 However, similarly to those reports, salivary tumors remained the leading histologic etiology with pleomorphic adenomas representing the most common diagnosis overall.

Twenty percent of the masses found within the prestyloid PPS were malignant with five separate histologic diagnoses identified. Most of these malignant masses were found to have ill-defined infiltrative borders. This characteristic was not seen amongst the benign tumors. Accordingly, we found infiltrative borders to be extremely supportive of a malignant diagnosis with a specificity of 100% and a negative predictive value of 96%. These findings support the use of cross-section imaging as a predictive tool in determining benign from malignant masses in the prestyloid PPS. While there appears to be a strong association between infiltrative margins and malignancy, a notable consideration is that pleomorphic adenomas can have malignant transformation over time. Approximately 1.5% of pleomorphic adenomas undergo malignant degeneration within 5 years of discovery and this can increase to 9.5% after 15 years. 14 Thus, pleomorphic adenomas with an initially benign-appearing margin may eventually progress to a malignant mass, and surgical resection needs to be considered especially in younger patients.

Limitations of this study include retrospective nature of the study, limitation to surgically treated cases, and small sample size related to the rarity of PPS tumors. In comparison to published reports, our series containing 31 cases of pathologically proven prestyloid PPS masses is relatively large. 23 Further evaluation with multicenter analysis with larger number of cases is warranted and would help verify the findings of our investigation. Use of a retrospective study design likely contributes to selection bias for larger and more aggressive appearing lesions. With appreciation for these limitations, we believe that meaningful conclusions can be drawn from the results.

Our results demonstrate that tumor margins have a high specificity and negative predictive value for differentiating benign from malignant masses within the prestyloid PPS. These findings can help guide decisions about how aggressively to manage masses within the space. Infiltrative tumor margins are concerning for malignancy and their presence would strongly argue for aggressive management, information that could be incorporated into the informed consent. If a tumor is well-defined, conservative management can be considered, especially in subsets of populations with likely benign pathology and high risks involved with undergoing a procedure. Therefore, tumor margins should be considered when determining the clinical management of newly diagnosed masses in the prestyloid PPS.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Nicholas Vargas https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8294-7622

References

- 1.Shin JH, Lee HK, Kim SY, et al. Imaging of parapharyngeal space lesions: focus on the prestyloid compartment. AJR 2001; 177: 1465–1470. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771465 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orloff LA. Head and neck ultrasonography: essential and extended applications. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing Inc., 2017, pp. 61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta J, Chazen JL, Phillips CD. Imaging evaluation of the parapharyngeal space. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2012; 45: 1223–1232. DOI: 10.1016/j.otc.2012.08.002 10.1016/j.otc.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grodinsky M, Holyoke EA. The fasciae and fascial spaces of the head, neck and adjacent regions. Am J Anat 1938; 63: 367–408. DOI: 10.1002/aja.1000630303 10.1002/aja.1000630303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall C. LXIV. The parapharyngeal space: an anatomical and clinical study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1934; 43: 793–812. DOI: 10.1177/000348943404300314 10.1177/000348943404300314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stambuk HE, Patel SG. Imaging of the parapharyngeal space. Otolaryngol Clin North AM 2008; 41: 77–101. DOI: 10.1016/j.otc.2007.10.012 10.1016/j.otc.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hees T, van Weert S, Witte B, et al. Tumors of the parapharyngeal space: the VU University Medical Center experience over a 20-year period. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018; 275: 967–972. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-018-4891-x 10.1007/s00405-018-4891-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locketz GD, Horowitz G, Abu-Ghanem S, et al. Histopathologic classification of parapharyngeal space tumors: a case series and review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016; 273: 727–734. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-015-3545-5 10.1007/s00405-015-3545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldarelli C, Bucolo S, Spisni R, et al. Primary parapharyngeal tumours: a review of 21 cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 18: 283–292. DOI: 10.1007/s10006-014-0451-8 10.1007/s10006-014-0451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riffat F, Dwivedi RC, Palme C, et al. A systematic review of 1143 parapharyngeal space tumors reported over 20 years. Oral Oncol 2014; 50: 421–430. DOI: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.02.007 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betka J, Chovanec M, Klozar J, et al. Transoral and combined transoral-transcervical approach in the surgery of parapharyngeal tumors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 267: 765–772. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-009-1071-z 10.1007/s00405-009-1071-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh M, Gupta SC, Singla A. Our experiences with parapharyngeal space tumors and systematic review of the literature. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 61: 112–119. DOI: 10.1007/s12070-009-0047-z 10.1007/s12070-009-0047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SM, Burkey BB, Netterville JL. Surgical management of parapharyngeal space masses. Head Neck 2005; 27: 669–675. DOI: 10.1002/hed.20199 10.1002/hed.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madani G, Beale T. Tumors of the salivary glands. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI 2006; 27: 452–464. DOI: 10.1053/j.sult.2006.09.004 10.1053/j.sult.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahuja AT, Evans RM. Practical head and neck ultrasound. London, UK: Greenwich Medical Media, 2000, pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahuja AT, King AD, Kew J, et al. Head and neck lipomas: sonographic appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 505–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Som PM, Biller HF. High-grade malignancies of the parotid gland: identification with MR imaging. Radiology 1989; 173(3): 823–826. DOI: 10.1148/radiology.173.3.2813793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christe A, Waldherr C, Hallett R, et al. MR imaging of parotid tumors: typical lesion characteristics in MR imaging improve discrimination between benign and malignant disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32(7): 1202–1207. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsushima N, Maeda M, Takamura M, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficients of benign and malignant salivary gland tumors. Comparison to histopathological findings. J Neuroradiol 2007; 34(3): 183–189. DOI: 10.1016/j.neurad.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takumi K, Nagano H, Kikuno H, et al. Differentiating malignant from benign salivary gland lesions: a multiparametric non-contrast MR imaging approach. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 2780, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-82455-2 10.1038/s41598-021-82455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsen KD. Tumors and surgery of the parapharyngeal space. Laryngoscope 1994; 104: 1–28. DOI: 10.1288/00005537-199405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pang KP, Goh CH, Tan HM. Parapharyngeal space tumours: an 18 year review. J Laryngol Otol 2002; 116(3): 170–175. DOI: 10.1258/0022215021910447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallabhaneni AC, Mandakulutur SG, Vallabhaneni S, et al. True parapharyngeal space tumors: case series from a teaching oncology center. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017; 69(2): 225–229. DOI: 10.1007/s12070-017-1099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]