Proteogenomic analyses of triple-negative breast cancer samples from a neoadjuvant carboplatin/docetaxel chemotherapy trial identified LIG1 loss as a biomarker for carboplatin-selective resistance, chromosomal instability, and disease progression.

Abstract

Microscaled proteogenomics was deployed to probe the molecular basis for differential response to neoadjuvant carboplatin and docetaxel combination chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Proteomic analyses of pretreatment patient biopsies uniquely revealed metabolic pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation, adipogenesis, and fatty acid metabolism, that were associated with resistance. Both proteomics and transcriptomics revealed that sensitivity was marked by elevation of DNA repair, E2F targets, G2–M checkpoint, interferon-gamma signaling, and immune-checkpoint components. Proteogenomic analyses of somatic copy-number aberrations identified a resistance-associated 19q13.31–33 deletion where LIG1, POLD1, and XRCC1 are located. In orthogonal datasets, LIG1 (DNA ligase I) gene deletion and/or low mRNA expression levels were associated with lack of pathologic complete response, higher chromosomal instability index (CIN), and poor prognosis in TNBC, as well as carboplatin-selective resistance in TNBC preclinical models. Hemizygous loss of LIG1 was also associated with higher CIN and poor prognosis in other cancer types, demonstrating broader clinical implications.

Significance:

Proteogenomic analysis of triple-negative breast tumors revealed a complex landscape of chemotherapy response associations, including a 19q13.31–33 somatic deletion encoding genes serving lagging-strand DNA synthesis (LIG1, POLD1, and XRCC1), that correlate with lack of pathologic response, carboplatin-selective resistance, and, in pan-cancer studies, poor prognosis and CIN.

This article is highlighted in the In This Issue feature, p. 2483

INTRODUCTION

Ten percent to 15% of breast cancers are designated triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) because of low expression of HER2, the estrogen receptor (ER), and the progesterone receptor. TNBC exhibits high mortality and frequent chemotherapy resistance (1). A minority of TNBC cases are linked to hereditary homologous recombination defects (HRD), most commonly in the BRCA1 gene, and are treatable with PARP inhibitors (2). However, the majority of TNBC cases do not have an obvious hereditary explanation, and therefore the underlying DNA repair defects are more obscure (3). Cytotoxic chemotherapy is standard of care but is only partially effective; hence, lack of pathologic complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is frequent and associated with poor survival (4). Post non-pCR, salvage therapy with adjuvant capecitabine has modest efficacy (5). The programmed cell death receptor (PD1)–targeting antibody pembrolizumab is also approved for neoadjuvant TNBC treatment based on the results of the KEYNOTE-522 trial (6). In combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pembrolizumab significantly prolongs event-free survival versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (7). In contrast to metastatic TNBC, outcome improvements are not predicted by PD-L1 IHC in primary disease (8). Carboplatin also has efficacy in TNBC. The BrighTNess trial enrolled patients with stage II or III operable TNBC and randomized patient treatment to one of three arms prior to doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide: paclitaxel/carboplatin/veliparib (arm A), paclitaxel/carboplatin (arm B), or paclitaxel alone (arm C). Carboplatin-containing arms A and B showed significantly improved pCR compared with paclitaxel alone (53% and 58%, respectively, vs. 31%; ref. 9). The efficacy of carboplatin addition is supported by two other randomized neoadjuvant trials: CALGB 40603 (Alliance; ref. 10) and GeparSixto (11). Thus, in the absence of predictive markers for individual components of each regimen, the neoadjuvant treatment for TNBC involves up to seven different drugs.

Herein we describe the first study to deploy microscaled proteogenomics (12) to discover neoadjuvant chemotherapy response biomarkers in TNBC. Snap-frozen, optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT)–embedded core needle biopsies were accrued from patients enrolled in two clinical trials that investigated a simplified carboplatin and docetaxel regimen designed to be less toxic by omitting doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (NCT02547987 and NCT02124902; ref. 13). This dataset included germline-matched tumor whole-exome DNA sequencing (WES), RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), and tandem mass tag (TMT)–based proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Analyses focused on the identification of biomarker associations with pCR, with the goal of identifying patients who would be better served with investigational drugs at diagnosis rather than suffer an ineffective standard of care. Multiple independent datasets were used to validate findings in the discovery analysis, including mRNA profiles of other TNBC clinical trials, IHC, preclinical therapeutic studies in patient-derived TNBC xenografts (PDX), and pan-cancer analysis using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).

RESULTS

Overview of the Proteogenomic Analysis Approach

OCT-embedded, snap-frozen core needle biopsies were accrued from consented patients with clinical stage 2 or 3 TNBC (70% Caucasian, 27% African American, and 3% other racial categories). Patients were subsequently treated with six cycles of neoadjuvant carboplatin and docetaxel combination chemotherapy (NCT02547987 and NCT02124902). Pretreatment samples from 59 patients had >25% tumor content (TC) and were ultimately analyzed. For 16 patients, an additional sample was obtained 48 to 72 hours after initiating chemotherapy. A Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) diagram demonstrates sample flow into different analytical pipelines (Fig. 1A). Using previously described BioTEXT sample processing and microscaled proteogenomics methods (12), frozen core biopsies were processed on a cryotome to produce 50-μm sections for analyte extraction interspersed with 5-μm sections to document TC. Alternating 50-μm sections were distributed into three different analyte preparation approaches to ensure even representation of analytes from different layers in the biopsy. Multianalyte extraction allowed for paired normal/tumor DNA exome sequencing (100×), RNA-seq, and quantitative, multiplexed (TMT) mass spectrometry (MS)–based proteomics and phosphoproteomics (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Figure 1.

TNBC patient sample overview. A, REMARK diagram showing pre- and on-treatment sample accrual schema from patients with TNBC enrolled in two clinical trials [NCT02544987 (BCM) and NCT201404107 (WashU)] and treated with carboplatin and docetaxel in the neoadjuvant setting. *, <45% samples were later excluded from the analysis based on evidence from data quality control. B, Overview of available omics datasets from 59 patients (22 tumors with pCR and 37 tumors without pCR). Pathogenic BRCA1/2 and PALB2 mutation status, RCB, and patient race are indicated via color-coded annotation tracks. C, Venn diagram showing the overlap of gene IDs detected across multiple analytes and omics data profiled. SCNA, somatic copy-number alteration. D, Hallmark metabolism pathways are induced by chemotherapy exclusively at the protein level. Scatter plot shows signed −log10 FDR from GSEA using the signed (by direction of change) −log10P values from paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests comparing RNA (x-axis) and protein levels (y-axis) for on-treatment (cycle 1, day 3) samples to matching baseline samples (n = 14).E, MSigDB Hallmark metabolism pathways are elevated in baseline non-pCR tumors at the protein level, whereas immune and cell-cycle pathways are elevated in baseline pCR tumors at both RNA and protein levels. Scatter plot shows the signed −log10 FDR values from GSEA using ranked lists of signed (by direction of change) −log10P values from Wilcoxon rank sum tests comparing RNA (x-axis) and protein (y-axis) levels in non-pCR tumors to pCR tumors. F, Cell-cycle kinase targets and PTM-SigDB phosphosites associated with genotoxic stress are enriched in pCR tumors relative to non-pCR tumors at baseline. Volcano plot shows results from PTM-SEA using the signed −log10P values from Wilcoxon rank sum tests comparing phosphosite levels in non-pCR tumors to pCR tumors. Red and blue dots indicate significant (FDR <0.05) posttranslational modification signatures.

Sample-level mRNA to protein correlations deteriorated in seven samples with an average TC below 45% (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Based on this cutoff, a total of nine samples with proteomics data (including one sample that lacked RNA and one sample that lacked both RNA and protein) were therefore excluded from further bioinformatic analyses. TMT11 multiplexes were linked using a pooled sample common reference to serve as a denominator for calculating peptide and phosphosite ratios (12). The common reference samples showed very strong correlations across multiplexes, indicating consistent data quality (Supplementary Fig. S1B). For each qualified sample, DNA, RNA, and protein level information was available for an average of 10,500 genes (Fig. 1C) and phosphoproteomic analysis quantified ∼27,000 phosphorylation sites in ∼5,000 distinct phosphoproteins (Fig. 1C). Comparable with previous Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) proteogenomic analyses, median per gene mRNA to protein correlation was 0.37 (ref. 14; Supplementary Fig. S1C). Genes with significant positive RNA–protein correlations were enriched for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways involved in cellular respiration as well as amino acid and lipid metabolism. Genes with lower correlations were enriched in pathways containing large protein complexes serving the spliceosome, replication, transcription, and pyrimidine metabolism (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Consistent with previous observations, protein data significantly outperformed RNA data for coexpression-based gene function predictions (Supplementary Fig. S1D; refs. 12, 15–17).

A pairwise analysis was also conducted using 14 cases with baseline high TC (out of 16 pairs) matched to a second high TC specimen collected 48 to 72 hours after treatment (only 13 pairs had RNA data; Fig. 1B). Whereas immune-related pathways were downregulated upon treatment at both the RNA and protein level, cell-cycle and metabolic pathways (except glycolysis) were significantly upregulated specifically at the protein level (Fig. 1D; Supplementary Table S4). Induction of DNA replication and repair pathways linked to the cell cycle was observed, likely in response to genotoxic stress triggered by chemotherapy exposure (18). This observation was also present in the phosphorylation site data (Supplementary Fig. S1E). Sets of phosphosites induced by treatment overlapped with those established to be induced by nocodazole and ionizing radiation treatment, which is logical in the setting of docetaxel and carboplatin exposure. Increases in phosphorylation were also detected for targets of the cell cycle and DNA damage kinases CDK1, CDK2, and ATM (Supplementary Fig. S1E).

Exploration of Proteogenomic Pathway Signatures and Response to Chemotherapy

Primary study endpoints were pCR and residual cancer burden (RCB) in the surgical specimen where 0 indicates pCR and I to III indicate increasing levels of residual disease (19). PAM50 intrinsic subtype (20), TNBC type (21), and racial categories lacked association with pCR, as did other cohort-specific clinical metadata (Supplementary Fig. S1F). Expected associations for pCR with germline mutations in the homologous recombination genes BRCA1/2 and PALB2 (22) or with homologous recombination deficiency–associated Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) signature 3 were also not observed (23, 24). These negative findings emphasize the limitations of our study in terms of sample size. However, an elevated COSMIC signature 6 score, indicating a mismatch repair defect (23, 24), was associated with high RCB (II or III; P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. S1G). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of proteogenomic features (Supplementary Table S5) that differed by pCR status indicated upregulation of the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) Hallmark metabolic pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid metabolism, and adipogenesis in samples without pCR. These associations were observed in the proteomic data but not at the mRNA level (Fig. 1E; Supplementary Table S6). In contrast, immune signaling (interferon alpha and gamma response) and cell cycle (G2–M checkpoint and E2F and MYC target) pathways were elevated in pCR cases in both the proteomic and transcriptomic datasets (Fig. 1E). Enrichment analysis of differential phosphorylation sites [posttranslational modification-set enrichment analysis (PTM-SEA); ref. 25] logically demonstrated elevated phosphoproteome-driven signatures in samples from pCR cases for treatment with inhibitors that generate DNA damage (etoposide, hydroxyurea, and ionizing radiation; Fig. 1F). Elevated MARK2 target sites were enriched in non-pCR tumors (Fig. 1F), corroborating prior evidence for higher MARK2 levels in cisplatin resistance in other cancer types (26, 27). Consistent with significantly elevated cell-cycle pathways observed in pCR samples in the RNA and protein data, CDK1, 2, and 7 and CDC7 target phosphosites were also significantly higher in pCR samples (Fig. 1F). Further sample-wise investigation of cell-cycle proteogenomic features revealed that multigene proliferation scores (MGPS), single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) scores, and PTM-SEA scores for cell cycle–related pathways and cyclin-dependent kinases were higher in pCR but were variable in non-pCR (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Of note, a subset of non-pCR samples had elevated CDK4 activity and Rb phosphorylation (highlighted in the box in Supplementary Fig. S2A), and Rb phosphorylation was marginally higher in non-pCR tumors (Supplementary Fig. S2B). To study the therapeutic significance of these findings, TNBC cell lines from the DepMap resource were explored (www.depmap.org). In this database, higher Rb protein was associated with reduced carboplatin response but enhanced CDK4/6 inhibitor response (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

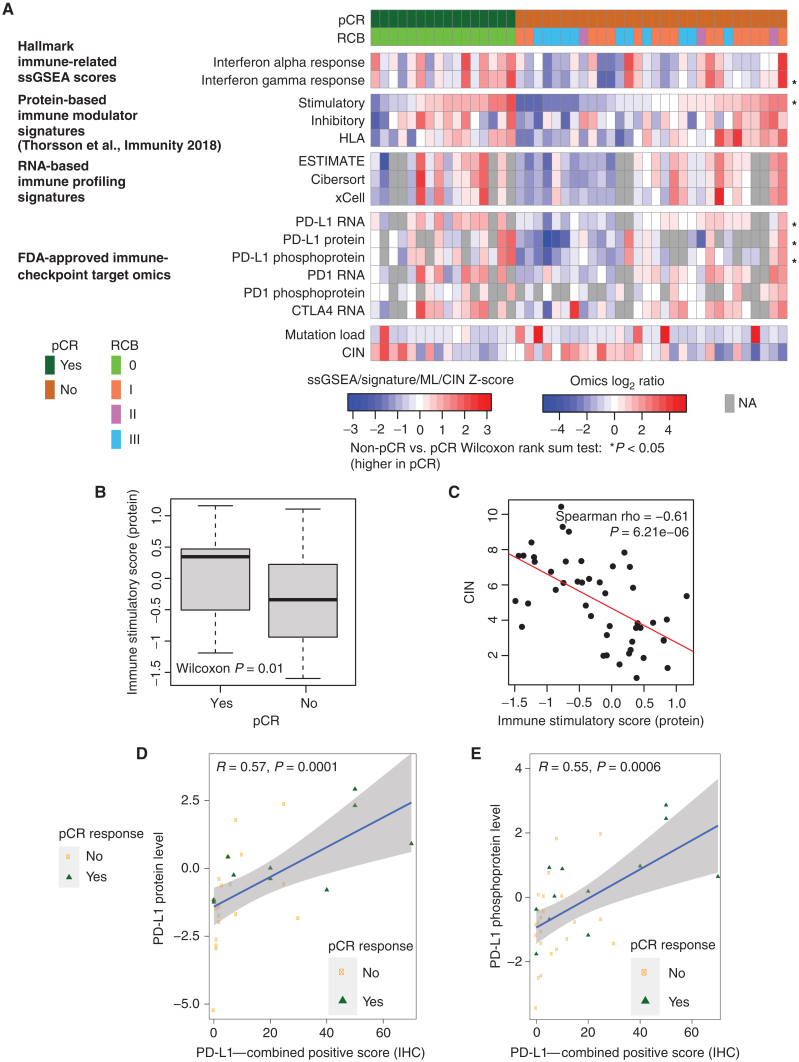

Immune Pathways and Response to Chemotherapy

Because interferon alpha and gamma response signatures were elevated in samples from pCR cases, signals from the immune microenvironment were further explored (Fig. 2A). Protein-derived immune stimulatory scores, previously found to be well correlated with immune infiltration (14), as well as PD-L1 RNA, protein, and phosphorylation levels, were significantly higher in pCR-associated samples (Fig. 2A and B). Nonsynonymous mutation load was associated with neither pCR (Wilcoxon rank sum P = 0.57, median for pCR = 77, median for non-pCR = 78) nor immune scores (Spearman rho = −0.17, P = 0.25), suggesting increased mutation burden was not a strong determinant of immune infiltration in this TNBC dataset. Rather, immune scores were significantly anticorrelated with chromosomal instability index (CIN; Spearman Rho = −0.61, P = 6.2e−6; Fig. 2C). Both PD-L1 protein and phosphoprotein levels significantly correlated with PD-L1 IHC (Fig. 2D and E). Similar correlations were also observed between PD-L1 RNA and IHC (Supplementary Fig. S2D). Representative IHC images for high and low PD-L1 staining are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2E and S2F, respectively.

Figure 2.

Proteogenomic features associated with the immune microenvironment are elevated in pCR tumors relative to non-pCR tumors. A, Heat map shows protein-based Hallmark ssGSEA scores, protein-based immune modulator scores, RNA-based immune profiles, and proteogenomic features for immune-checkpoint genes that are targets of FDA-approved inhibitors. Within each group (pCR and non-pCR), samples are ordered by increasing immune stimulatory score. *, P < 0.05 by the Wilcoxon rank sum test comparing non-pCR with pCR tumors. NA, not available. B, The protein-based immune stimulatory score is significantly higher in pCR tumors than in non-pCR tumors (P = 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Box plots show interquartile range (IQR) with the median marked in the center. Whiskers indicate 1.5× IQR. C, The immune stimulatory score is negatively correlated to CIN (Spearman rho = −0.612, P = 6.2e−6). The scatter plot shows immune stimulatory score on the x-axis and CIN on the y-axis.D and E, Scatter plots showing the Pearson correlation between PD-L1 IHC levels with PD-L1 protein (D) and phosphoprotein levels (E). pCR cases are shown in green and non-pCR in orange.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis and Response to Chemotherapy

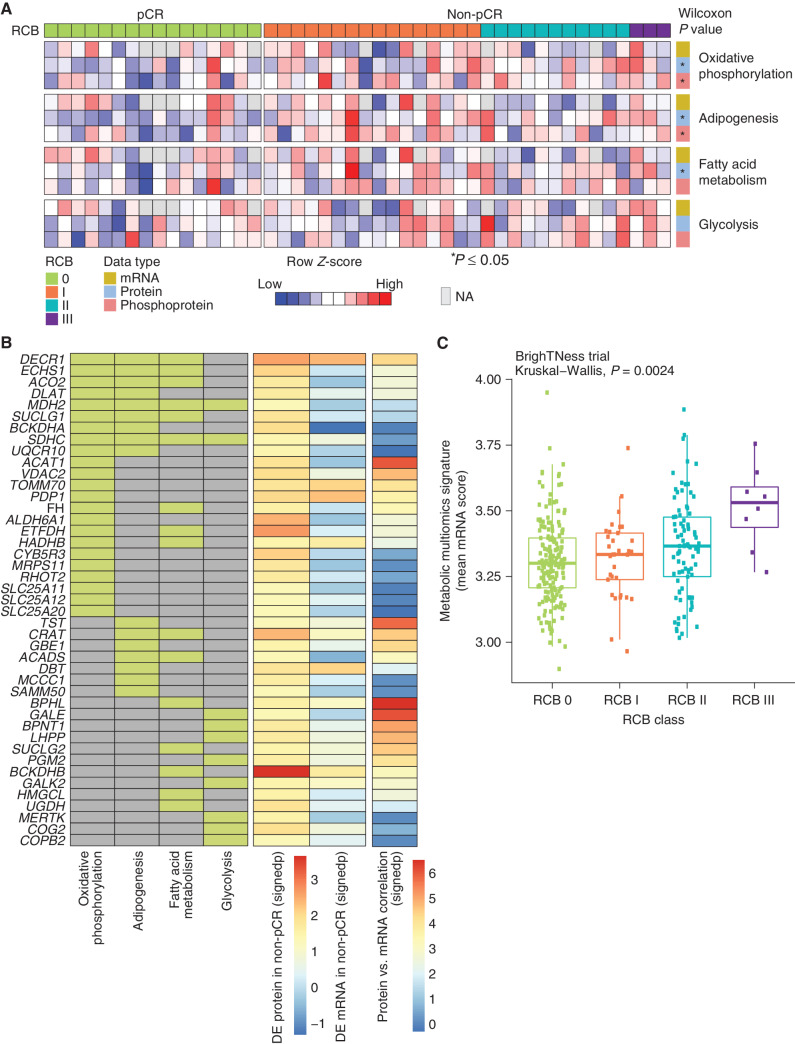

As noted above, (Fig. 1D and E) metabolic pathway enrichment appeared specific to proteomic data (with FDR correction). Both GSEA (Fig. 1E) and ssGSEA showed that differential metabolic pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation, adipogenesis, and fatty acid metabolism, as well as glycolysis, were significantly higher in pretreatment tumors without subsequent pCR (Fig. 3A). Further analyses of the individual protein levels identified many chemotherapy resistance–associated metabolic proteins, such as those directly involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (ACO2, FH, MDH2, SUCLG1, SUCLG2, PDP1, and DLAT), the electron transport chain (SDHC and UQCR10), fatty acid metabolism (CRAT, ACADS, ACAT1, DECR1, ECHS1, and HADHB), and amino acid catabolism (ALDH6A1, HMGCL, DBT, and BCKDHB; Fig. 3B). Although pCR-associated metabolic pathway scores were more robust at the proteomic data level than transcriptomic data, this did not equate to lack of mRNA and protein correlation for all metabolism gene products associated with non-pCR. A subset (29 of 43) from the relevant Hallmark metabolic pathways showed sufficient protein–mRNA correlation to allow independent validation of metabolic gene expression associations with pCR at the mRNA level (Fig. 3B) in the BrighTNess trial dataset (9). In this study, patients in arms A and B received combination treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel plus/minus veliparib (addition of which did not affect outcomes), as well as subsequent treatment with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (9). Baseline RNA expression data for the subset of metabolism-associated resistance genes with high mRNA–protein correlation were used for association with pCR status on data from both arms A and B combined. Geometric mean metabolic scores were significantly higher for non-pCR cases as compared with pCR cases (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P = 0.003; N = 359; Supplementary Fig. S3). Additionally, increasing metabolic scores were observed as the RCB category increased (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.0024; Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Proteogenomic features associated with the lack of pCR in TNBC tumors. A, Heat map showing ssGSEA normalized enrichment score for metabolic Hallmark pathways that are significantly higher in non-pCR cases, arranged by RCB 0 (pCR) and RCB I/II/III (non-pCR). Shown are the four pathways that showed significant enrichment at either the RNA or protein level in Fig. 1E. Single-sample pathway enrichment scores were assessed at the level of mRNA (yellow), protein (blue), and phosphoprotein (red). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare scores for non-pCR vs. pCR scores; *, P < 0.05. NA, not available. B, Membership of differentially regulated proteins to pathways highlighted in A. Proteins (rows) belonging to a given pathway (columns) are shown in light green. The differential expression (DE) at protein and mRNA levels for each gene along with mRNA–protein correlation scores are shown as signed −log10P value (signedp). C, A multiomics metabolic gene signature derived for genes that are correlated at mRNA and protein levels was further investigated in patients treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel in the BrighTNess clinical trial (treatment arms A and B) for which RNA-seq data were available. The mean mRNA expression score for this signature was significantly higher in higher RCB tumors.

Proteogenomic Analyses of Copy-Number Alteration Reveal Novel Chemotherapy Response Biomarkers

The somatic landscape of TNBC is dominated by recurrent copy-number alterations (CNA; ref. 28); however, the significance of many recurrent CNA events remains unclear, because typically many genes are involved in larger scale chromosomal deletions and rearrangements (29). A typical pattern of CNA for TNBC was observed in this dataset (Supplementary Fig. S4A). To explore whether chemotherapy response correlates with the expression of genes located at specific chromosomal locations (cytobands), GSEA was run against the cytoband database (Fig. 4A). Individual gene expression ranks derived from the non-pCR versus pCR sample comparison using a signed −log10P value derived from the Wilcoxon test were used as the input for this analysis. This unbiased prioritization demonstrated that expression of gene products from the 8q21.3 (amplified) and 19q13.31–33 (deleted) cytobands was elevated and suppressed, respectively, in non-pCR versus pCR tumors (Fig. 4B). Four genes located at 8q21.3, RMDN1, CPNE3, DECR1, and OTUD6B, showed higher mRNA and protein expression in non-pCR tumors (Supplementary Fig. S4B). In addition, RIPK2, which may mediate metastasis in advanced breast cancer (28), also located on 8q21.3, was significantly higher in non-pCR tumors but only at the protein level. Similarly, four genes located on 19q13.31–33, LIG1, PPP5C, BCL3, and NOSIP, showed lower mRNA and protein expression in non-pCR tumors (Fig. 4C). Both mRNA and protein level expression from these coordinately downregulated genes were confirmed to be suppressed in association with single-copy LIG1 loss (GISTIC = −1) status in a subset of non-pCR–associated samples (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Hallmark pathway GSEA of the genes on cytoband 19q13.31–33 showed enrichment in the DNA damage repair (DDR) pathway, with LIG1, XRCC1, POLD1, and ERCC2 comprising the leading-edge genes (Fig. 4D). LIG1 showed the strongest association with treatment response at the protein level, followed by POLD1 (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Discovery of DNA repair and replication components enriched in non-pCR TNBC tumors. A, Cytobands enriched in genes differentially expressed between non-pCR and pCR for both mRNA and protein. To identify upregulated or downregulated features overrepresented in certain cytobands within the chromosome, GSEA was used to identify regions from chromosomal location databases enriched with differential genes [GSEA input was ranked expression list (signed −log10P value) from Wilcoxon rank sum tests]. Overrepresented cytobands that were either enriched or depleted using differentially expressed mRNA and protein are indicated in B, and the overlapping sets were used for further analysis. B, Plot showing significantly enriched or depleted cytobands obtained by running differential mRNA and protein ranked lists through GSEA. NES, normalized enrichment score. Genes downregulated in non-pCR samples corresponding to cytoband 19q13.31–33 are indicated in C. C, Venn diagram showing differential (non-pCR vs. pCR) mRNA and proteins located on cytoband 19q13.3. D, Overrepresentation analysis (ORA) shows that differential 19q13.31–33 genes are enriched with Hallmark DNA repair pathway genes. Downregulation of these DNA repair genes at the mRNA and protein levels in non-pCR cases is shown in the bar chart on the right as signed −log10P values from Wilcoxon rank sum tests. E, Box plot comparing RNA expression of DNA repair genes located on 19q13.31–33 in the previously published BrighTNess clinical trial (treatment arms A and B), in which patients were treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare residual disease (RD) cases with pCR cases. F, Forest plot showing hazard ratios (HR) and P values for metastasis-free survival associated with LIG1, POLD1, XRCC1, and ERCC2. HR is based on categorizing samples using a median expression cutoff for each gene in the Hatzis dataset.

To determine whether these observations were reproducible in other datasets, the association of LIG1, XRCC1, POLD1, and ERCC2 mRNA with pCR and RCB was evaluated at the mRNA level in the BrighTNess trial. For this analysis, the two carboplatin- and paclitaxel-containing arms were combined to parallel the docetaxel and carboplatin treatment in this study (9). LIG1 and POLD1 were confirmed to be significantly downregulated in baseline tumor samples from patients who experienced residual disease (Fig. 4E). Similar differences were not observed in the paclitaxel-only arm, although the sample size was smaller (treatment arm C, P > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S4D). Low RNA expression levels for LIG1 and XRCC1 were also significantly associated with poor metastasis-free survival in the TNBC subset of another neoadjuvant chemotherapy–treated patient cohort (ref. 30; Fig. 4F; Supplementary Fig. S4E). Finally, a trial where a modest number of patients were treated with single-agent cisplatin neoadjuvant therapy was interrogated (31). Consistent with the other datasets, LIG1 mRNA levels were significantly lower in samples associated with stable or progressive disease (SD + PD) as opposed to samples associated with a complete or partial response (CR + PR; Supplementary Fig. S4F). Of the four DDR genes located within 19q13.31–33, LIG1 was the most consistently associated with chemotherapy resistance and poor metastasis-free survival across datasets (Fig. 4E and F; Supplementary Fig. S4E and S4F).

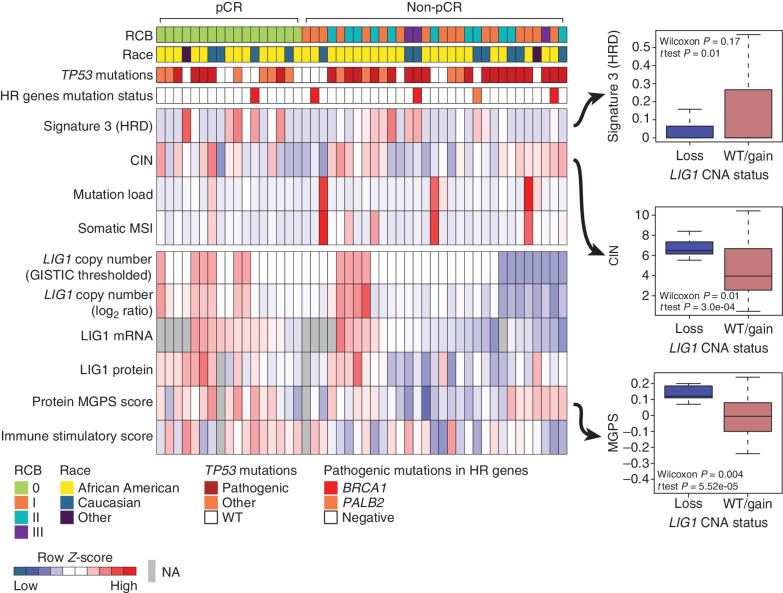

Molecular Features of TNBCs Harboring LIG1 Deletion

The associations between LIG1 deletion and/or reduced expression with tumor pathophysiologic features were further investigated in the discovery set. Low LIG1 copy-number levels (GISTIC = −1) were observed in 8 of the 31 (∼26%) tumors without pCR (Fig. 5). LIG1 copy-number log ratios were strongly and positively correlated with the level of both LIG1 mRNA (Pearson, R = 0.67, P = 2.8e−06) and LIG1 protein (R = 0.55, P = 8.2e−05; Supplementary Fig. S5A and S5B). At the genomic level, COSMIC HRD signature 3 was lower in tumors with LIG1 loss (t test, P = 0.01; Fig. 5). In contrast, tumors harboring LIG1 loss exhibited significantly higher CIN (t test, P = 0.0003; Fig. 5). Although no significant differences were observed in immune stimulatory scores when LIG1 loss tumors were compared other tumors, tumors with LIG1 loss had lower immune stimulatory scores when compared with tumors that were associated with pCR (P = 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S5C). At the level of phosphosite expression-based PTM-SEA (25) analysis, the IL33 pathway was significantly downregulated in LIG1-loss tumors (Supplementary Fig. S5D and S5E). Tumors with LIG1 loss also had significantly higher protein-based proliferation scores (p-MGPS; Wilcoxon P = 0.004; Fig. 5) as well as upregulation of CDK1/2 activity (Supplementary Fig. S5D) in PTM-SEA analysis of differential phosphosites (25), supporting increased cell-cycle activity (FDR P < 0.05). Collectively, these results suggest that the loss of LIG1 is associated with a constellation of poor prognosis features including higher proliferation rates, a less active immune microenvironment, and higher copy-number instability. Furthermore, when the phosphoproteomic data were examined, signatures of EGFR (gefitinib) and PI3K (wortmannin) perturbations were significantly enriched in LIG1-loss tumors but in a negative direction (Supplementary Fig. S5D and S5E). Because LIG1-loss tumors have suppressed EGFR and PI3K signaling, they may be less responsive to EGFR, PI3K, or AKT inhibition.

Figure 5.

Proteogenomic features associated with LIG1. Heat map showing copy number, mRNA, and protein levels of LIG1, which are significantly (Wilcoxon rank sum test) lower (blue) in non-pCR tumors. Corresponding box plots show that tumors with low-level copy loss of LIG1 (GISTIC = −1, likely single copy-number loss) display significantly higher chromosomal instability and MGPS and significantly lower signature 3 (COSMIC mutational signature associated with HRD) than tumors that are wild-type (WT) or show gain of CNA (GISTIC ≥0). Wilcoxon rank sum tests and t tests were used to compare LIG1-loss cases with LIG1-intact (WT/gain) cases. HR, homologous recombination; MSI, microsatellite instability; NA, not available.

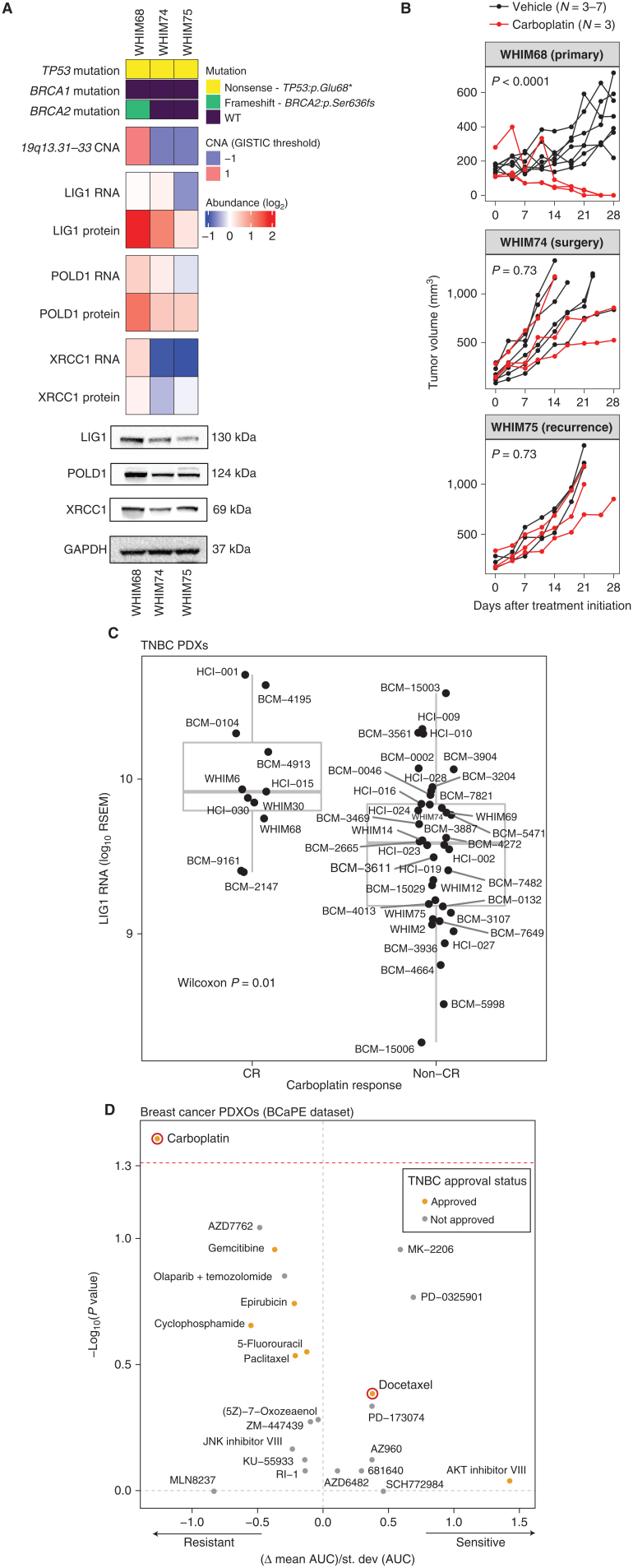

LIG1 and Chemotherapy Response in Model Systems

When chemotherapy-resistance biomarkers are identified, the question arises as to whether the biomarker relationship is drug selective. Model systems can be useful in this regard because patients almost always receive multiple drugs. Another concern is whether a biomarker is associated with intrinsic resistance, acquired resistance, or both. Patient data suggested a higher frequency of LIG1 copy loss in metastatic disease (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Patterns of 19q13.31–33 loss during malignant progression were therefore explored using three orthotopic PDX models generated from a single patient on the discovery trial NCT02544987. WHIM68 grew from the pretreated breast primary tumor, WHIM74 from a surgical sample accrued after 5 months of neoadjuvant carboplatin and docetaxel, and WHIM75 from a liver metastasis that appeared 1 year after treatment initiation. Proteogenomic analysis revealed a progressive loss of LIG1 at the copy-number, mRNA, and protein levels as the tumor progressed to a chemotherapy-resistant state (Fig. 6A). Progressive loss of LIG1 protein was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Fig. S6B) along with similar reductions of POLD1 and XRCC1 protein expression. Consistent with the progressive loss of chemotherapy sensitivity observed clinically, WHIM68, which expressed the highest LIG1 level, was sensitive to carboplatin, whereas WHIM74 and 75 were progressively and remarkably less sensitive (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Table S7). Interestingly, this relationship was not as marked with docetaxel treatment (Supplementary Fig. S6C; Supplementary Table S7). Of note, a BRCA2 loss-of-function somatic mutation was present in the baseline PDX (WHIM68) but was undetectable in the two PDXs derived from patient tumors after treatment. This suggests a treatment-induced clonal selection—that is, as the patient was treated, the BRCA2-mutant clone regressed, and a LIG1-deleted clone expanded. To further assess the potential association between LIG1 loss and selective carboplatin insensitivity, a large TNBC PDX cohort from the NCI PDXnet program was examined (32). LIG1 mRNA levels were significantly lower in PDXs that failed to demonstrate a CR to carboplatin (Fig. 6C), and this relationship was not significant for docetaxel treatment (Supplementary Fig. S6D). A second independent TNBC PDX sample with short-term in vitro treatment with multiple different oncology drugs was also examined [ref. 33; Breast Cancer PDTX Encyclopaedia (BCaPE) database]. This dataset demonstrated that LIG1 copy-number loss was uniquely correlated with carboplatin resistance among over 100 drugs tested (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

LIG1 association with advanced TNBC disease in preclinical models. A, Proteogenomic status of LIG1, POLD1, and XRCC1 in three PDX models derived from longitudinal biopsies from the same patient with TNBC prior to any treatment (WHIM68), at the time of surgery after completing 5 months of neoadjuvant carboplatin and docetaxel (WHIM74), and from a liver metastasis 1 year after treatment initiation (WHIM75). Mutation and copy-number data were derived from WES and RNA from RNA-seq, and protein data were obtained from TMT proteomics generated by this current study. Bottom, representative western blots from three biological repeats for LIG1, POLD1, and XRCC1 protein levels. GAPDH was used as a loading control. WT, wild-type. *, stop codon. B, Tumor volume was measured in three PDX models. Black and red lines indicate changes in tumor volume in PDXs treated with vehicle and carboplatin, respectively. WHIM68, with the highest LIG1 protein levels, was most sensitive to carboplatin, whereas WHIM74 and 75, which displayed progressive LIG1 loss at the copy-number, mRNA, and protein levels, were insensitive to carboplatin treatment. P values derived from a general linear model within each PDX were computed using estimated mean log2 fold changes in tumor volume at day 28 versus day 0 for each treatment arm.C, Box plots showing LIG1 mRNA levels in TNBC PDXs categorized into CR and non-CR groups. After 4 weeks of carboplatin treatment, CR was defined as PDXs with nonpalpable tumors, and non-CR was defined as PDXs with residual tumors with measurable dimensions. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the two groups. RSEM, expected counts from RNA-seq by expectation-maximization. D, Association between LIG1 copy-number loss and treatment response in PDX organoids (PDXO) obtained from the BCaPE database. Carboplatin and docetaxel are highlighted in red.

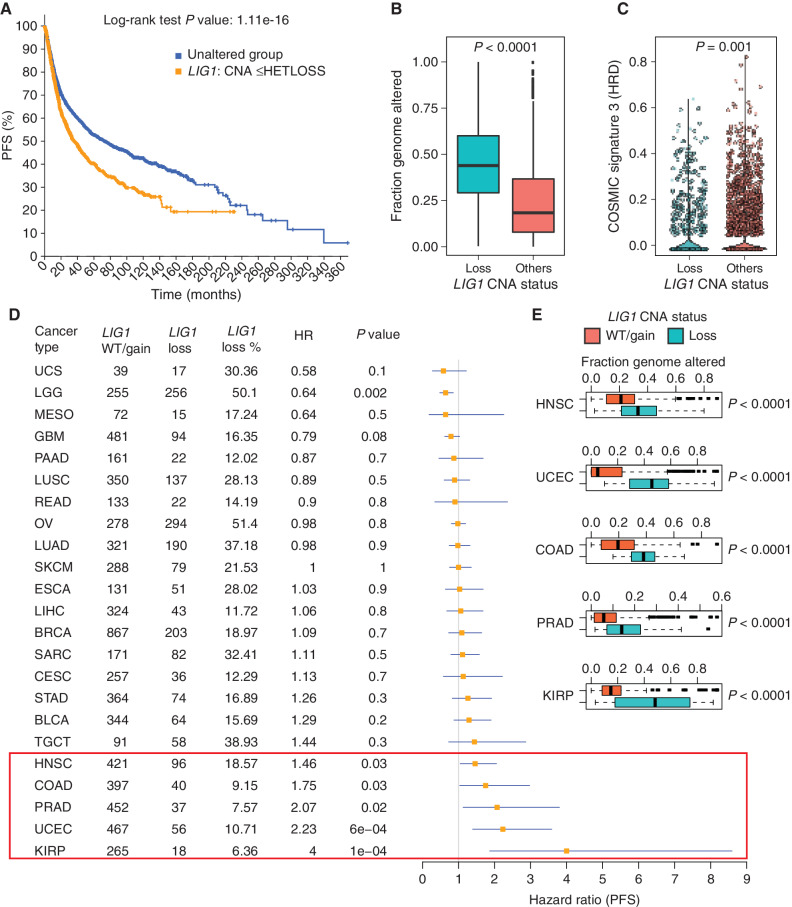

LIG1 Copy-Number Loss Is Associated with Poor Progression-Free Survival and CIN across Multiple Cancer Types

Gene copy-number analysis of tumors characterized by TCGA demonstrated that LIG1 single-copy loss is present in other cancer types. In the TCGA pan-cancer dataset, LIG1 heterozygous loss was associated with poor progression-free survival (PFS; Fig. 7A; P < 0.0001), significantly higher fraction genome altered (Fig. 7B), and lower signature 3 scores (suggesting proficient homologous recombination; Fig. 7C). Cancer types driving these relationships include endometrial carcinoma (hazard ratio = 2.23, P = 0.02), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (hazard ratio = 1.46, P = 0.03), prostate adenocarcinoma (hazard ratio = 2.07, P = 0.02), colon adenocarcinoma (hazard ratio = 1.75, P = 0.03), and most convincingly renal papillary cell carcinoma (hazard ratio = 4, P = 0.0001; Fig. 7D). Despite a marginal association between PFS and LIG1 loss in testicular germ cell tumors, the seminoma subtype, which demonstrates exquisite sensitivity to carboplatin (34), displayed no cases of LIG1 loss (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Higher genomic instability was observed with LIG1 loss in several other cancers (Fig. 7E, fraction genome altered in TCGA cohorts; Supplementary Fig. S7B, CIN in CPTAC cohorts).

Figure 7.

Pan-cancer analysis of LIG1 loss. A, Kaplan–Meier curve showing significantly reduced (log-rank P value) PFS for tumors with single-copy loss of LIG1 (HETLOSS, GISTIC ≤−1, indicated in orange) in the TCGA pan-cancer cohort. B, Box plot showing higher fraction genome altered (FGA) in tumors with LIG1 copy-number-loss tumors (shown in teal) relative to tumors that were LIG1 wild-type or displayed LIG1 gain (shown in orange). C, Violin plot showing significantly lower (Wilcoxon rank sum test) COSMIC signature 3 scores in LIG1-loss tumors (shown in teal). D, Forest plot showing the impact of LIG1 copy-number loss on PFS by cancer type along with LIG1 wild-type (WT)/gain/loss frequency, HR, and corresponding P value. BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; MESO, mesothelioma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TGCT, testicular germ cell tumors; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma. E, Box plot showing significantly higher (by Wilcoxon rank sum test) FGA (representing chromosomal instability) in tumors that had LIG1 copy-number loss versus tumors with either wild-type LIG1 or LIG1 copy-number gain. Shown are the only five cancers (HNSC, UCEC, COAD, PRAD, and KIRP) that displayed a significant association between LIG1 loss and adverse prognosis.

DISCUSSION

The absence of a baseline pCR predictor is a persistent unmet need for the precision treatment of TNBC. Patients without pCR suffer prolonged exposures to toxic and ineffective treatment and therefore do not receive alternative treatment soon enough. Additionally, PD-L1 IHC assays have failed to predict the benefit of immune-checkpoint blockade in TNBC (35). Thus, alternative biomarkers for antitumor immunity are required. This study suggests that integrated proteogenomic characterization provides more extensive information on the immune microenvironment that could be used to complement PD-L1 IHC. Although a TMT-based proteomic assay for PD-L1 would not be practical, targeted proteomic assays optimized for quantitative measurement using heavy isotope–labeled peptides for multiple immune response components are an efficient and cost-efficient approach that could complement IHC (36). Secondly, we observed a novel association for baseline oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism gene products with chemoresistance in TNBC. These findings are supported by functional studies in TNBC model systems demonstrating a role for oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism as drivers of TNBC chemoresistance (37, 38). In fact, fatty acid synthase inhibition using the proton pump inhibitor omeprazole in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with TNBC is currently being evaluated in a phase II trial (NCT02595372). pCR prediction models could therefore be strengthened by the inclusion of protein level analysis of these pathways. The cellular origin of these resistance-associated metabolic signals is unresolved. An additional possibility is immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages with high lipid content (39). A third class of potential pCR predictors are G2–M checkpoint components, E2F regulators, and MYC target pathways. For example, TNBC tumors with high/intact Rb protein and phosphorylation levels have lower pCR rates and lower levels of proliferation and E2F target gene expression than tumors with the loss of Rb protein (14). CDK4/6 or CDK2 inhibitors could therefore be an alternative treatment for RB intact TNBC. Finally, the proteomic analysis clearly assists in the prioritization of genomic chromosomal alterations associated with pCR status, exemplified herein by the identification of LIG1 as a TNBC chemotherapy-resistance and multicancer-type poor prognosis marker. The finding from preclinical models that LIG1 loss is a selective biomarker for carboplatin resistance is provocative. The use of carboplatin adds toxicity to an already toxic anthracycline-based regimen and could potentially be avoided in LIG1-depleted tumors.

Regarding LIG1 loss as a potential pathogenetic event in TNBC, there are already mechanistic studies of LIG1 loss that support this hypothesis. LIG1 encodes an ATP-dependent DNA ligase that seals DNA nicks during replication, recombination, and a variety of DNA damage responses (40). Of the three DNA ligases in the human genome (LIG1, 3, and 4), LIG1 is the main enzyme responsible for ligating Okazaki fragments during lagging-strand synthesis at the replication fork during S-phase (41–43). LIG1 also ligates single-stranded or double-stranded DNA breaks in various DDR pathways, including long-patch base-excision repair, nucleotide-excision repair, and alternative nonhomologous end-joining repair (44, 45). A phenotype for LIG1 deficiency in humans was first identified in an immunodeficient patient with homozygous germline hypomorphic LIG1 alleles causing impaired Okazaki fragment ligation (46). Insufficient LIG1 activity results in the accumulation of replication intermediates that cause single-stranded and double-stranded breaks (DSB; refs. 47, 48), ultimately leading to reduced genome integrity. In transgenic mice, hypomorphic LIG1 alleles were associated with high susceptibility to cancer formation (49). However, the relevance of these observations can be challenged in the setting of TNBC, because single-copy LIG1 loss observed in our studies may not produce sufficient functional deficiency to generate a phenotype. However, codeletion of LIG1, POLD1, and XRCC1 on 19q13.31–33 may produce a hemizygous compound deficiency phenotype because all three genes serve lagging-strand synthesis. XRCC1 is particularly noteworthy because LIG3/XRCC1 provides a backup pathway for LIG1-mediated DNA ligation during DNA repair and lagging-strand DNA synthesis (50).

The presence of LIG1 loss was found to be orthogonal to the HRD mutational signature 3. Consequently, LIG1-deficient cells may be required to be proficient in DSB repair, that is, HRD and LIG1 loss are orthogonal routes to TNBC pathogenesis, and this potentially could explain the correlation with carboplatin insensitivity. The PDX study (Fig. 6) hints at this, as the model derived from the pretreatment sample (WHIM68) had a BRCA2 frameshift mutation and no LIG1 loss, and the subsequent carboplatin-resistant lines (WHIM74 and 75) had lost the BRCA2 mutation and gained a LIG1 hemizygous deletion. It remains unclear why LIG1 loss is so strongly associated with chromosomal instability across cancer types, and mechanistic studies connecting these events are an important next step. However, it can be hypothesized that cells that enter mitosis with unrepaired lagging strands are at risk for chromosomal breakage, illicit chromosomal fusion events, and aneuploidy.

In conclusion, our findings emphasize the potential of microscaled proteogenomic approaches for the investigation of cancer treatment resistance. Follow-up mechanistic studies are clearly warranted, not just for LIG1-related biology but also, for example, the role of lipid-related metabolic signatures in chemotherapy resistance. However, the lack of complete mechanistic insight does not diminish the clinical importance of novel chemotherapy drug-selective predictive biomarkers in a setting where a genomic approach or transcriptomic analyses have yet to produce actionable models.

METHODS

Clinical Sample Collection

Eligible patients for the two clinical trials (NCT02547987 and NCT02124902) included pre- or postmenopausal women at least 18 years old with clinical stages II/III ER-negative and HER2-negative (0 or 1+ by IHC or FISH negative) invasive breast cancer. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both participating sites, WashU and BCM, and written informed consent from the patients was obtained. The studies were conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines and followed the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients were uniformly treated (without randomization or blinding) with neoadjuvant intravenous docetaxel 75 mg/m2 and carboplatin every 21 days for 6 cycles with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support (13). Research tumor biopsies for correlative studies were obtained at baseline prior to chemotherapy and on cycle 1, day 3. On-treatment biopsy on cycle 1, day 3 and biopsy at the time of relapse were optional. Details of the clinical cohort have recently been published (13). Treatment response information was provided by clinical teams associated with these trials and RCB was calculated using the RCB calculator (http://www3.mdanderson.org/app/medcalc/index.cfm?pagename=jsconvert3).

IHC

For IHC, cut tissue sections (5 mm) on charged glass slides were baked for 10 to 12 hours at 58°C in a dry slide incubator, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated via an ethanol step gradient. The IHC slides were stained for CD3 and PD-L1. Pathology slide scoring was performed using established professional guidelines for TNBC when appropriate. All IHC results were evaluated against positive and negative tissue controls. See Supplementary Data and Methods for more details.

Genomic Analysis

WES

Tumor DNA was extracted from fresh-frozen biopsies and matched leukocyte germline DNA from blood samples. WES data were generated for 59 unique baseline DNA samples using the Illumina platform. For this, paired-end libraries were constructed as described previously (51) with the modifications described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Whole exome sequencing (WES)” section.

RNA-seq data

Transcriptome data were generated for 60 samples in this study. For this, strand-specific, poly-A+ RNA-seq libraries for sequencing on the Illumina platform were prepared as previously described (52). See the Supplementary Data and Methods “RNA-seq data” section for additional details. Between 59.96 and 112.62M total reads were generated for these 60 samples. The average strand specificity and rRNA rate were 97.04% and 1.79%, respectively. The transcripts for 22,868 to 27,856 genes were detected in these samples.

The paired-end reads were mapped to the human genome version GRCh38.d1.vd1 (from Genomic Data Commons) using STAR-2.7.1a. Gene expression estimation was performed using RSEM-1.3.1, and expected counts from RNA-seq by expectation-maximization (RSEM) and fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) values were upper-quartile normalized. Unless otherwise noted, gene median-centered log2-transformed RSEM values were used for the analyses presented here.

Somatic and copy-number variant calling

Somatic variants were called using paired tumor and blood normal from WES data. Tools used for somatic variant calling were Strelka2, Mutect2, CARNAC, and Pindel (v 0.2.5b9). Filtering steps are described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Somatic and copy number variant calling” section. Similarly, germline mutations were called by comparing normal WES against the reference genome. Hg19.UCSC.add_miR.140312.refgene was used to map the copy-number information to genes. COSMIC mutational signature scores for every sample were estimated using deconstructSigs (53).

For somatic CNA analysis, bam files were processed by the CopywriteR package (54) to derive log2 tumor-to-normal copy-number ratios, and the circular binary segmentation algorithm (55) implemented in the CopywriteR package was used for the copy-number segmentation with the default parameters.

CIN for each chromosome in each sample was inferred from the segmentation data using a weighted-sum approach in which the absolute values of the log2 ratios of all segments within a chromosome were weighted by the segment length and summed up (16). The genome-wide chromosome instability index (CIN) was derived by adding up the instability scores for all 22 autosomes in each sample. MSIsensor (56) was used to calculate somatic microsatellite instability (MSI) counts.

GISTIC2 (57) was used to retrieve gene-level copy-number values and call significant CNAs in the cohort. A threshold of ±0.3 was applied to log2 copy-number ratio to identify gene-wise gain or loss of copy number, respectively. Each gene of every sample was assigned a thresholded copy-number level that reflected the magnitude of its deletion or amplification. These are integer values ranging from −2 to 2, where 0 means no amplification or deletion of magnitude greater than the threshold parameters described above. Amplifications are represented by positive numbers: 1 means amplification above the amplification threshold; 2 means amplification larger than the arm-level amplifications observed in the sample. Deletions are represented by negative numbers: −1 means deletion beyond the threshold; −2 means deletions greater than the minimum arm-level copy number observed in the sample.

For the pan-cancer analysis, GISTIC value ±2 exceeds the high-level thresholds for amplifications/deep deletions, and that with ±1 exceeds the low-level thresholds but not the high-level thresholds. The low-level thresholds are just the “ampthresh” and “delthresh” noise threshold input values to GISTIC (typically 0.1 or 0.3) and are the same for every threshold.

Proteomics Data Generation and Analysis

Proteomic sample preparation

Samples were prepared for proteomic analysis as described in a previous microscaled proteogenomic study (12) with minimal alterations. The details are described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Proteomic sample preparation” section. For TMT labeling, a total of 30 μg peptides in 100 μL 50 mmol/L HEPES, pH 8.5, were labeled with 240 μg TMT reagent for an 8:1 TMT:peptide ratio and incubated at 25°C for 1 hour. Excess TMT reagent was quenched by incubating with 5 μL 5% hydroxylamine (Sigma) for 15 minutes. Samples within each plex were combined according to the ratios determined to achieve sample representation within ±15% error margin to all other samples. The combined peptides were desalted on a 100-mg tC18 Sep-Pak (Waters), eluted with 50% acetonitrile/0.1% FA, and dried in a vacuum centrifuge.

Experimental design for proteomics and phosphoproteomics

Samples were analyzed in a TMT11 format as described above. To measure relative protein and phosphosite expression, common references were constructed. The first core common reference consisted of peptide material from all clinical core samples, such that an even proportion was contributed for each of the 60 patients. The second common reference (“prospective BRCA CR”) was from a previous large cohort breast cancer proteomics study (14). Protein and phosphosite expression was reported as the TMT intensity ratio between each sample and the core common references within each plex. For analysis of clinical core samples, eight TMT 11-plexes each contained peptides from nine core needle biopsies in the first nine channels. If available, paired pre- and posttreatment tumor samples from a patient were grouped within the same 11-plex. As a quality control measure, we obtained protein and phosphopeptide ratios between the prospective BRCA CR and the core common reference, and the results are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1C.

Basic Reverse-Phase Fractionation and Phosphoenrichment

For basic reverse-phase fractionation, ∼330 μg of peptides were dissolved in 500 μL of 5 mmol/L ammonium formate and 5% acetonitrile using an offline Agilent 1260 LC with a 30-cm long, 2.1-mm inner diameter C18 column, running at 200 μL per minute in a total of 72 fractions, and further concatenated into 18 fractions for proteome analysis and 6 fractions for Fe3+ immobilized metal affinity chromatography-based phosphoproteomics analysis. The details of this method have been described (12) and appear in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Basic reverse phase fractionation and phosphoenrichment” section.

Proteomic Data Acquisition and Processing

Proteome and phosphoproteome data acquisition was performed with a Proxeon nLC-1200 coupled to Thermo Lumos instrumentation with parameters described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Proteomic data acquisition and processing” section.

Raw files were searched against the human (clinical cores) or humanRefSeq protein databases complemented with 553 small open reading frames (smORF) and common contaminants (Human: RefSeq.20171003_Human_ucsc_hg38_cpdb_mito_259contamsnr_553smORFS.fasta) using Spectrum Mill (Broad Institute) and parameters described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Proteomic data acquisition and processing” section.

Quantification, Normalization, and Filtering of Proteomics Data

Before the calculation of protein and phosphopeptide ratios, reporter ion signals were corrected for isotopic impurities. Relative abundances of proteins and phosphosites were selected as the median of TMT reporter ion intensity ratios from all peptide spectral matches (PSM) matching to the protein or phosphosite. PSMs were excluded if they lacked a TMT label, had a precursor ion purity <50%, or had a negative delta forward-reverse score. To normalize across 11-plex experiments, TMT intensities were divided by the common reference for each protein and phosphosite. Log2 TMT ratios were further normalized by median centering and median absolute deviation scaling. Proteins and phosphosites quantified in fewer than 30% of samples (i.e., missing in >70% of samples) were removed from the respective datasets.

PDX Proteomics Data Generation and Analysis

For the PDX experiment, cryopulverized PDX tumor tissues were lysed and digested as described above. Peptides (50 μg) were dissolved in 200 μL 50 mmol/L HEPES, pH 8.5, and labeled with 400 μg of the TMT reagent. TMT sample generation, basic reverse fractionation, and proteomic analysis were performed identically to that of clinical core biopsies. Raw files were searched against the human and mouse (PDX samples) UniProt protein databases complemented with 553 smORFs and common contaminants (human and mouse: UniProt.human.mouse.20171228.RIsnrNF.553smORFs.264contams.fasta) using the Spectrum Mill subgroup-specific option described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “PDX proteomics data generation and analysis” section.

Data Quality Control and Differential Expression and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Samples with estimated TC below 45% were entirely removed from the dataset due to a lack of RNA-to-protein correlation in these samples (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The Wilcoxon rank sum test in R was used to identify genes (RNA), proteins, phosphosites, and phosphoproteins (mean of all sites on a given protein) that were differential between samples from pCR and non-pCR cases (Supplementary Table S5) and between samples with LIG1 loss (GISTIC = −1) and those without a loss (LIG1 wild-type/gain GISTIC ≥0). WebGestaltR (58) and PTM-SEA (25) were used to identify MSigDB Hallmark pathways (gene-level data) and posttranslational modification (PTM) signature sets (phosphosite-level data), respectively, that show enrichment in pCR or non-pCR tumors by applying the GSEA/PTM-SEA algorithms to signed (by direction of change) log10P values from the differential expression analysis (Supplementary Table S6). Additionally, the ssGSEA R package (59, 60) was applied to RNA, protein, and phosphoprotein data, and scores for Hallmark pathways were obtained for individual samples (Supplementary Table S6). Normalized enrichment scores (NES) were utilized for visualization purposes. The Wilcoxon signed rank test in R was used for paired differential analysis of on-treatment to baseline measurements for RNA, protein, phosphosite, and phosphoprotein data for 14 patients with matched on-treatment and baseline biopsies (only 13 had matched RNA data). GSEA using WebGestaltR and PTM-SEA was applied to signed log10-transformed P values from this analysis. PTM-SEA was also applied to phosphosite log2 TMT ratios for each baseline sample to obtain single-sample kinase activity scores (NES for kinase target PTM sets).

Functional Prediction based on Gene Coexpression

Coexpression network construction using mRNA and protein expression data and network-based gene function prediction for KEGG pathways were performed as previously described (15) using OmicsEV (https://github.com/bzhanglab/OmicsEV).

Multigene Proliferation and Immune Profiling Scores

RNA-based MGPS were calculated as described previously (14, 61) by averaging the gene median-centered log2 RSEM data for all genes previously characterized as cycle-regulated (62) in each sample. Protein-based MGPS were generated for each sample by averaging log2 TMT ratios for all proteins that showed significant correlation with the RNA-based MGPS (Pearson correlation, P < 0.01 after Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction). Immune profile and microenvironment scores were inferred from the FPKM version of the RNA-seq data using ESTIMATE (63), Cibersort (ref. 64; run in absolute mode), and xCell (65). Protein-based immune modulator scores were calculated as described previously (14) by averaging log2 TMT ratios for expert-curated sets of immune modulators belonging to three categories: immune stimulatory, immune inhibitory, and HLA (66).

Immunoblotting

Fresh-frozen WHIM68, WHIM74, and WHIM75 tumors were cryopulverized (Covaris CP02) and then lysed in RIPA buffer. Lysates were blotted for LIG1 (cat. #18051-1-AP, ProteinTech, 1:1,000), POLD1 (cat. #15656-1-AP, ProteinTech, 1:1,000), or XRCC1 (cat. #ab134056, Abcam, 1:1,000). GAPDH (cat. #sc-47724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:4,000) was used as a loading control. Details are described in the Supplementary Data and Methods “Immunoblotting” section).

Validation Using DepMap

Global TMT measurements for RB1 and response profiles to approved drugs from the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal, Genomics of Drug-Sensitivity in Cancer, and Profiling Relative Inhibition Simultaneously in Mixtures (PRISM) drug response datasets for cancer cell lines were retrieved from the DepMap resource (www.depmap.org). TNBC cell lines were selected based on ERneg_HER2neg lineage_sub_subtype for breast lineages from sample information provided by DepMap. For TNBC cell lines, Pearson correlation was calculated between RB1 protein abundance (log2 TMT ratio) and drug responses (AUC). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

The genomics and transcriptomics data have been deposited in the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP) under the accession code phs002505.v1, and the proteomics data are accessible through the NCI Proteomics Data Commons (https://pdc.cancer.gov/pdc/) with the accession identifiers PDC000408 (TNBC biopsies proteome raw files), PDC000409 (TNBC biopsies phosphoproteome raw files), and PDC000410 (TNBC PDX proteome raw files). MS raw files can also be accessed via MassIVE (https://massive.ucsd.edu/) with the accession identifier MSV000089758.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following funding support: U24CA160034 (S.A. Carr), U24CA210986 (S.A. Carr and M.A. Gillette), U01CA214125 (M.J. Ellis /M. Anurag, S.A. Carr), U24CA210979 (D.R. Mani), R03OD032626 (D.R. Mani), U24CA210954 (B. Zhang), P50 CA186784-06 (M.J. Ellis), U54CA224083 (S. Li), U54 CA224076 (M.T. Lewis), U24 CA226110 (M.T. Lewis), P30 NCI-CA125123 (C.K. Osborne), RR160027 [B. Zhang, Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar in Cancer Research], RR RR140027 (M.J. Ellis, CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research), RR200009 (G.V. Echeverria, CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research), RP170691 (CPRIT Core Facilities Support Grant), GH0005083 Breast Cancer Research (S. Li). The NCI-SPORE Career Enhancement Award to M. Anurag (part of P50 CA186784-06), T32CA203690 support to J.T. Lei, 1S10OD028671-01 to G. Miles, and K12 CA167540 to F.O. Ademuyiwa are also acknowledged. M.J. Ellis is a Susan G. Komen Foundation Scholar. M.J. Ellis and B. Zhang are McNair Scholars supported by the McNair Medical Institute at The Robert and Janice McNair Foundation. This work was also supported by generous gifts from the Korell family, Lisa and Ralph Eads, and Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Oncology (Dr. John Dipersio). The authors are most grateful to the NCI CPTAC along with patients and caregivers participating in this study. The authors thank the patient advocates (GRASP Huddle) for their insightful comments and suggestions.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Discovery Online (http://cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors’ Disclosures

M. Anurag reports grants from the NIH (U01CA214125 and P50 CA186784-06) during the conduct of the study, as well as a patent for proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in TNBC pending. E.J. Jaehnig reports grants from the NCI and the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas during the conduct of the study, as well as a patent for proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in TNBC pending. K. Krug reports a patent for Provisional Application No. 63/317,402 pending to the Broad Institute. J.T. Lei reports grants from the NIH during the conduct of the study. D.M. Muzny reports grants from the NIH during the conduct of the study. L.E. Dobrolecki reports grants from Harold & Patricia Korell, a Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas Core Facility Award (RP170691), and NCI-CA125123 P30 Cancer Center Support Grant during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees from StemMed, Ltd. outside the submitted work. M.T. Lewis reports grants from the NCI and the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, and other support from the Korrell family during the conduct of the study, as well as other support from StemMed, Ltd., Tvardi Therapeutics Inc., and StemMed Holdings outside the submitted work. M. Nemati Shafaee reports other support from Eli Lilly, Moderna, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi and grants from Pfizer outside the submitted work. S. Li reports other support from Envigo outside the submitted work. I.S. Hagemann reports personal fees as part of expert witness services and from Change Healthcare outside the submitted work. B. Lim reports consulting fees in the past from Natera, Novartis, Lilly, Pfizer, Puma, AstraZeneca, and Daiichi Sankyo; research funding to conduct trials from Puma, Pfizer, Amgen, Merck, Takeda, Genentech, and Calithera; and honoraria from Prime Oncology and Alpine Oncology. C.K. Osborne reports other support from GeneTex outside the submitted work. D.R. Mani reports grants from the NCI during the conduct of the study. M.A. Gillette reports grants from NIH during the conduct of the study, as well as a pending patent describing proteogenomic methods for diagnosing cancer. B. Zhang reports grants from the NCI and the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas during the conduct of the study; personal fees from AstraZeneca and TNIK Pharmaceuticals Ltd outside the submitted work; and a patent for proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in TNBC pending. M.F. Rimawi reports grants from Pfizer and personal fees from Macrogenics, Seagen, AstraZeneca, and Novartis outside the submitted work. F.O. Ademuyiwa reports personal fees from Pfizer and Gilead, grants from NeoImmnueTech, Cardinal Health, Biotheranostics, QED, AstraZeneca, and Athenex outside the submitted work. S. Satpathy reports a patent for proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in TNBC pending. M.J. Ellis reports grants from NIH NCI U01214125, NIH NCI P50186784, RR140033, NIH NCI P30 125123, RP210227, and U24CA210954, other support from Lisa and Ralph Eads, and grants and other support from the Korell family during the conduct of the study; personal fees from AstraZeneca outside the submitted work; and a patent for US/094,898 issued and with royalties paid from Veracyte, a patent for CA2,630,974 issued and with royalties paid from Veracyte, a patent for EU06844413.2 issued and with royalties paid from Veracyte, and a patent for U.S. Provisional 63/317,402 pending. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

M. Anurag: Conceptualization, resources, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. E.J. Jaehnig: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing–review and editing. K. Krug: Data curation, investigation, visualization, writing–review and editing. J.T. Lei: Formal analysis, visualization, writing–review and editing. E.J. Bergstrom: Methodology. B.-J. Kim: Data curation, methodology. T.D. Vashist: Methodology. A.M. Tran Huynh: Methodology, writing–review and editing. Y. Dou: Software, methodology. X. Gou: Methodology. C. Huang: Software, methodology. Z. Shi: Methodology. B. Wen: Methodology. V. Korchina: Resources. R.A. Gibbs: Resources. D.M. Muzny: Resources. H. Doddapaneni: Resources, methodology. L.E. Dobrolecki: Resources, methodology. H. Rodriguez: Project administration. A.I. Robles: Project administration, writing–review and editing. T. Hiltke: Project administration. M.T. Lewis: Resources, methodology. J.R. Nangia: Resources. M. Nemati Shafaee: Resources. S. Li: Resources. I.S. Hagemann: Resources, methodology. J. Hoog: Data curation, methodology. B. Lim: Writing–review and editing. C.K. Osborne: Resources. D.R. Mani: Visualization, methodology. M.A. Gillette: Resources, writing–review and editing. B. Zhang: Resources, data curation, supervision, methodology. G.V. Echeverria: Writing–review and editing. G. Miles: Data curation, visualization, methodology. M.F. Rimawi: Resources. S.A. Carr: Conceptualization, resources, supervision. F.O. Ademuyiwa: Resources, investigation. S. Satpathy: Conceptualization, resources, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. M.J. Ellis: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rottenberg S, Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A, van der Burg E, Nygren AO, Zander SA, et al. High sensitivity of BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors to the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 alone and in combination with platinum drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:17079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Staaf J, Glodzik D, Bosch A, Vallon-Christersson J, Reutersward C, Hakkinen J, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of triple-negative breast cancers in a population-based clinical study. Nat Med 2019;25:1526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Symmans WF, Wei C, Gould R, Yu X, Zhang Y, Liu M, et al. Long-term prognostic risk after neoadjuvant chemotherapy associated with residual cancer burden and breast cancer subtype. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1049–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, Im YH, Lee ES, Yokota I, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2147–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, McArthur H, Kummel S, Bergh J, et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:810–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, Pusztai L, McArthur H, Kummel S, et al. Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:556–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fountzila E, Ignatiadis M. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy in breast cancer: a paradigm shift? Ecancermedicalscience 2020;14:1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loibl S, O'Shaughnessy J, Untch M, Sikov WM, Rugo HS, McKee MD, et al. Addition of the PARP inhibitor veliparib plus carboplatin or carboplatin alone to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (BrighTNess): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sikov WM, Berry DA, Perou CM, Singh B, Cirrincione CT, Tolaney SM, et al. Impact of the addition of carboplatin and/or bevacizumab to neoadjuvant once-per-week paclitaxel followed by dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide on pathologic complete response rates in stage II to III triple-negative breast cancer: CALGB 40603 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2015;33:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. von Minckwitz G, Schneeweiss A, Loibl S, Salat C, Denkert C, Rezai M, et al. Neoadjuvant carboplatin in patients with triple-negative and HER2-positive early breast cancer (GeparSixto; GBG 66): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:747–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Satpathy S, Jaehnig EJ, Krug K, Kim BJ, Saltzman AB, Chan DW, et al. Microscaled proteogenomic methods for precision oncology. Nat Commun 2020;11:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ademuyiwa FO, Chen I, Luo J, Rimawi MF, Hagemann IS, Fisk B, et al. Immunogenomic profiling and pathological response results from a clinical trial of docetaxel and carboplatin in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021;189:187–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krug K, Jaehnig EJ, Satpathy S, Blumenberg L, Karpova A, Anurag M, et al. Proteogenomic landscape of breast cancer tumorigenesis and targeted therapy. Cell 2020;183:1436–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang J, Ma Z, Carr SA, Mertins P, Zhang H, Zhang Z, et al. Proteome profiling outperforms transcriptome profiling for coexpression based gene function prediction. Mol Cell Proteomics 2017;16:121–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vasaikar S, Huang C, Wang X, Petyuk VA, Savage SR, Wen B, et al. Proteogenomic analysis of human colon cancer reveals new therapeutic opportunities. Cell 2019;177:1035–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang C, Chen L, Savage SR, Eguez RV, Dou Y, Li Y, et al. Proteogenomic insights into the biology and treatment of HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2021;39:361–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Christmann M, Kaina B. Transcriptional regulation of human DNA repair genes following genotoxic stress: trigger mechanisms, inducible responses and genotoxic adaptation. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:8403–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, Rajan R, Kuerer H, Valero V, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, Leung S, Voduc D, Vickery T, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest 2011;121:2750–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Byrski T, Huzarski T, Dent R, Marczyk E, Jasiowka M, Gronwald J, et al. Pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant cisplatin in BRCA1-positive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;147:401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 2012;149:979–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Deciphering signatures of mutational processes operative in human cancer. Cell Rep 2013;3:246–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krug K, Mertins P, Zhang B, Hornbeck P, Raju R, Ahmad R, et al. A curated resource for phosphosite-specific signature analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2019;18:576–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hubaux R, Thu KL, Vucic EA, Pikor LA, Kung SH, Martinez VD, et al. Microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 2 is associated with DNA damage response and cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2015;137:2072–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wei X, Xu L, Jeddo SF, Li K, Li X, Li J. MARK2 enhances cisplatin resistance via PI3K/AKT/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in osteosarcoma cells. Am J Transl Res 2020;12:1807–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smid M, Hoes M, Sieuwerts AM, Sleijfer S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Patterns and incidence of chromosomal instability and their prognostic relevance in breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;128:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mertins P, Mani DR, Ruggles KV, Gillette MA, Clauser KR, Wang P, et al. Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature 2016;534:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hatzis C, Pusztai L, Valero V, Booser DJ, Esserman L, Lluch A, et al. A genomic predictor of response and survival following taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. JAMA 2011;305:1873–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Silver DP, Richardson AL, Eklund AC, Wang ZC, Szallasi Z, Li Q, et al. Efficacy of neoadjuvant cisplatin in triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1145–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petrosyan V, Dobrolecki LE, Thistlethwaite L, Lewis AN, Sallas C, Rajaram R, et al. A network approach to identify biomarkers of differential chemotherapy response using patient-derived xenografts of triple-negative breast cancer. BioRxiv 2021.08.20.457116 [Preprint]. 2021. Available from: 10.1101/2021.08.20.457116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bruna A, Rueda OM, Greenwood W, Batra AS, Callari M, Batra RN, et al. A biobank of breast cancer explants with preserved intra-tumor heterogeneity to screen anticancer compounds. Cell 2016;167:260–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alifrangis C, Sharma A, Chowdhury S, Duncan S, Milic M, Gogbashian A, et al. Single-agent carboplatin AUC10 in metastatic seminoma: a multi-centre UK study of 216 patients. Eur J Cancer 2020;164:105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Badve SS, Penault-Llorca F, Reis-Filho JS, Deurloo R, Siziopikou KP, D'Arrigo C, et al. Determining PD-L1 status in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: lessons learned from IMpassion130. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022;114:664–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morales-Betanzos CA, Lee H, Gonzalez Ericsson PI, Balko JM, Johnson DB, Zimmerman LJ, et al. Quantitative mass spectrometry analysis of PD-L1 protein expression, N-glycosylation and expression stoichiometry with PD-1 and PD-L2 in human melanoma. Mol Cell Proteomics 2017;16:1705–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee KM, Giltnane JM, Balko JM, Schwarz LJ, Guerrero-Zotano AL, Hutchinson KE, et al. MYC and MCL1 cooperatively promote chemotherapy-resistant breast cancer stem cells via regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab 2017;26:633–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Echeverria GV, Ge Z, Seth S, Zhang X, Jeter-Jones S, Zhou X, et al. Resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer mediated by a reversible drug-tolerant state. Sci Transl Med 2019;11:eaav0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luo Q, Zheng N, Jiang L, Wang T, Zhang P, Liu Y, et al. Lipid accumulation in macrophages confers protumorigenic polarization and immunity in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci 2020;111:4000–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Howes TR, Tomkinson AE. DNA ligase I, the replicative DNA ligase. Subcell Biochem 2012;62:327–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waga S, Bauer G, Stillman B. Reconstitution of complete SV40 DNA replication with purified replication factors. J Biol Chem 1994;269:10923–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soderhall S, Lindahl T. DNA ligases of eukaryotes. FEBS Lett 1976;67:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Petrini JH, Xiao Y, Weaver DT. DNA ligase I mediates essential functions in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 1995;15:4303–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paul-Konietzko K, Thomale J, Arakawa H, Iliakis G. DNA ligases I and III support nucleotide excision repair in DT40 cells with similar efficiency. Photochem Photobiol 2015;91:1173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pascucci B, Stucki M, Jonsson ZO, Dogliotti E, Hubscher U. Long patch base excision repair with purified human proteins. DNA ligase I as patch size mediator for DNA polymerases delta and epsilon. J Biol Chem 1999;274:33696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barnes DE, Tomkinson AE, Lehmann AR, Webster AD, Lindahl T. Mutations in the DNA ligase I gene of an individual with immunodeficiencies and cellular hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Cell 1992;69:495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Soza S, Leva V, Vago R, Ferrari G, Mazzini G, Biamonti G, et al. DNA ligase I deficiency leads to replication-dependent DNA damage and impacts cell morphology without blocking cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29:2032–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harrison C, Ketchen AM, Redhead NJ, O'Sullivan MJ, Melton DW. Replication failure, genome instability, and increased cancer susceptibility in mice with a point mutation in the DNA ligase I gene. Cancer Res 2002;62:4065–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bentley D, Selfridge J, Millar JK, Samuel K, Hole N, Ansell JD, et al. DNA ligase I is required for fetal liver erythropoiesis but is not essential for mammalian cell viability. Nat Genet 1996;13:489–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Le Chalony C, Hoffschir F, Gauthier LR, Gross J, Biard DS, Boussin FD, et al. Partial complementation of a DNA ligase I deficiency by DNA ligase III and its impact on cell survival and telomere stability in mammalian cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012;69:2933–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rokita JL, Rathi KS, Cardenas MF, Upton KA, Jayaseelan J, Cross KL, et al. Genomic profiling of childhood tumor patient-derived xenograft models to enable rational clinical trial design. Cell Rep 2019;29:1675–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peters TL, Kumar V, Polikepahad S, Lin FY, Sarabia SF, Liang Y, et al. BCOR-CCNB3 fusions are frequent in undifferentiated sarcomas of male children. Mod Pathol 2015;28:575–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Taylor BS, Swanton C. DeconstructSigs: delineating mutational processes in single tumors distinguishes DNA repair deficiencies and patterns of carcinoma evolution. Genome Biol 2016;17:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kuilman T, Velds A, Kemper K, Ranzani M, Bombardelli L, Hoogstraat M, et al. CopywriteR: DNA copy number detection from off-target sequence data. Genome Biol 2015;16:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Venkatraman ES, Olshen AB. A faster circular binary segmentation algorithm for the analysis of array CGH data. Bioinformatics 2007;23:657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]