Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi, the spirochetal agent of Lyme disease, is transmitted by Ixodes ticks. When an infected nymphal tick feeds on a host, the bacteria increase in number within the tick, after which they invade the tick’s salivary glands and infect the host. Antibodies directed against outer surface protein A (OspA) of B. burgdorferi kill spirochetes within feeding ticks and block transmission to the host. In the studies presented here, passive antibody transfer experiments were carried out to determine the OspA antibody titer required to block transmission to the rodent host. OspA antibody levels were determined by using a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that measured antibody binding to a protective epitope defined by monoclonal antibody C3.78. The C3.78 OspA antibody titer (>213 μg/ml) required to eradicate spirochetes from feeding ticks was considerably higher than the titer (>6 μg/ml) required to block transmission to the host. Although spirochetes were not eradicated from ticks at lower antibody levels, the antibodies reduced the number of spirochetes within the feeding ticks and interfered with the ability of spirochetes to induce ospC and invade the salivary glands of the vector. OspA antibodies may directly interfere with the ability of B. burgdorferi to invade the salivary glands of the vector; alternately, OspA antibodies may lower the density of spirochetes within feeding ticks below a critical threshold required for initiating events linked to transmission.

Borrelia burgdorferi, the spirochete that causes Lyme disease, is transmitted when infected Ixodes ticks feed on susceptible hosts. Studies with infected nymphal ticks have given insight into spirochete transmission. Within unfed nymphal ticks, spirochetes are generally restricted to the lumen of the gut (2). When a tick engorges, spirochetes move from the gut through the hemolymph to the salivary glands and then enter the host along with the saliva of the vector (1, 7, 13, 15, 22). The bacteria need approximately 48 h to complete their journey from the tick gut to the vertebrate host. During the 48 h it takes for transmission, spirochetes within the vector also alter the expression of genes coding for surface antigens. In unfed ticks, the spirochetes in the lumen of the tick gut synthesize outer surface protein A (OspA) in abundance (7). When ticks engorge, the majority of organisms within feeding ticks downregulate OspA during migration (4, 7) and upregulate the synthesis of OspC (17), an antigen that then continues to be produced in the early stages of infection in the mammalian host (12).

B. burgdorferi OspA is a candidate antigen for a Lyme disease vaccine and is currently being tested in clinical trials. Active immunization with recombinant OspA or the passive administration of OspA antibodies protects mice against B. burgdorferi infection (9, 16, 19). Mice immunized with OspA are protected from tick-borne spirochetes because OspA antibodies in the tick blood meal target OspA-producing B. burgdorferi present in the tick gut before the bacteria have an opportunity to downregulate OspA (7). The vaccine is not effective against spirochetes in the host, probably because the majority of organisms that initially enter the host clear OspA from their surfaces (6, 7, 12). Thus, the vaccine is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking vaccine (7).

Since the OspA antigen is expressed primarily by spirochetes in the tick gut, the memory immune cells of the OspA-immunized host are unlikely to be stimulated by the antigen during tick-borne transmission. Protection of the immunized host will depend on circulating levels of OspA antibody which enter the tick gut at the beginning of the blood meal. Here we describe studies that were done to further understand the transmission of B. burgdorferi and to determine the mechanism by which OspA antibodies in the tick gut block transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and ticks.

Female mice, 4 to 6 weeks of age, were obtained from the pathogen-free-colony of outbred Imperial Cancer Research (ICR) mice maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory in Fort Collins, Colo. Nymphal Ixodes scapularis ticks were infected with B. burgdorferi B31 (from Shelter Island, N.Y.). Batches of ticks were included in the B. burgdorferi B31-infected colony if >80% of nymphs were infected.

Preparation of hyperimmune OspA antiserum.

Antigens used for immunization were a recombinant OspA–glutathione S-transferase (OspA-GST) fusion protein and the GST fusion partner (control). Escherichia coli harboring the recombinant plasmids was grown and recombinant proteins were purified as previously described (9). Mice were immunized by subcutaneously injecting 20 μg of the purified antigen suspended in complete Freund’s adjuvant and boosting at 2 and 4 weeks with 20 μg of antigen suspended in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. Six mice were immunized with the OspA-GST antigen, and three mice were immunized with the GST fusion partner. One week after the final immunization, the mice were killed and blood was collected by cardiac exsanguination. Sera from individual mice were pooled to obtain the OspA and GST hyperimmune antisera. On immunoblots with cultured B. burgdorferi as the antigen, the hyperimmune OspA antiserum specifically bound to the 31-kDa OspA.

Competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to determine levels of antibody in sera binding to the OspA C3.78 epitope.

The amount of antibody in a serum sample binding to the C3.78 epitope on OspA was determined by measuring the ability of the serum to compete the binding of the C3.78 OspA monoclonal antibody (MAb). The preparation and characterization of the C3.78 OspA MAb have been previously reported (9, 18). For the present study, the C3.78 MAb was obtained from serum-free hybridoma supernatant and concentrated by using protein G-Sepharose beads (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Half of the purified MAb was biotin labeled by using the Immunoprobe Biotinylation Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Chemical Co.). Ninety-six-well Titertek microtiter plates (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, Ohio) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of recombinant OspA (100 ng/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The following day the plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween). The plates were blocked for 0.5 h at 37°C with 5% skim milk in PBS. Next, the plates were incubated with 12.5 ng of biotin-labeled C3.78 MAb in the presence or absence of the unknown serum sample in a final volume of 200 μl for 1 h at 37°C. The unknown sera were tested in duplicate at multiple dilutions to obtain readings within the linear range of the assay. The plates were washed three times with PBS-Tween. The amount of biotin-labeled C3.78 MAb bound to the plate was determined by adding alkaline phosphatase-conjugated strepavidin (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) diluted 1:5,000 for 0.5 h at 37°C, washing away the unbound streptavidin, and developing the plates with commercially prepared phosphatase substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.). The optical densities of the plates were read at 405 nm. The ability of antibodies in the unknown serum sample to compete the binding of the biotinylated antibody to OspA was a measure of the amount of antibody in the unknown serum binding to the C3.78 epitope. In order to convert optical density readings to C3.78 MAb equivalents, a standard curve was set up by incubating different amounts of unlabeled C3.78 MAb with 12.5 ng of biotin-labeled C3.78 MAb. A linear inhibition of biotin-labeled antibody binding was observed at concentrations below 250 ng of unlabeled C3.78 MAb per ml. This standard curve was used to calculate C3.78 MAb equivalents in the unknown sera.

Evaluation of mice for B. burgdorferi infection.

To determine whether the mice were infected, 1 month after tick detachment the mice were sacrificed, and ear, urinary bladder, and heart tissue biopsies were obtained. Ear biopsies were soaked in Wescodyne for 15 min and in 70% alcohol for 15 min. Bladder and heart tissues were dipped in 70% alcohol. The tissues were finely minced and placed in 4-ml snap-cap tubes containing Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK) medium. Cultures were maintained at 34°C and checked weekly, for 4 weeks, for viable spirochetes by dark-field microscopy.

Estimation of the prevalence of infected ticks and the mean number of spirochetes within individual ticks.

To determine the prevalence of infection, 10 to 12 days after repletion the ticks were disinfected, homogenized, and cultured in BSK medium as previously described (8). Cultures were maintained at 34°C and checked weekly, for 4 weeks, for viable spirochetes by dark-field microscopy. To determine the mean number of spirochetes within individual nymphal ticks from each group, one to four ticks from each mouse were pooled and homogenized, and the spirochetes in each homogenate were stained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit B. burgdorferi antiserum and counted as previously described (7).

Double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy to determine the proportion of spirochetes expressing ospC.

The proportion of spirochetes from each group producing OspC was determined by performing double-labeling immunofluorescence microscopy as previously described (5). The primary antisera used were a rabbit polyclonal OspC antiserum (kindly provided by Stephen Schutzer) and a mouse polyclonal B. burgdorferi antiserum. The secondary antisera were FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G and rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G. In each group, 50 to 75 individual spirochetes staining with the B. burgdorferi antiserum (FITC channel) were examined for labeling with the OspC antiserum (rhodamine channel) to determine the percentage of spirochetes producing OspC.

RT-PCR for characterizing the expression of B. burgdorferi genes within ticks.

Total RNA was isolated from B. burgdorferi-infected ticks that had not fed (240 ticks) or that had fed for 60 h (240 ticks) by standard protocols for purifying total RNA (3). The RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) for 3 h at 37°C to eliminate any contaminating DNA. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT) and random primers (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). This cDNA was used in quantitative PCR experiments with flaB- and ospC-specific primer pairs to estimate the amounts of flaB and ospC mRNAs in flat and feeding ticks. The flaB primers were 5′-CGGCACATATTCAGATGCAGACAG-3′ (nucleotides 297 to 320) and 5′-CCAACGCAAGCATAAGGAACAAC-3′ (nucleotides 668 to 646) and amplified a 355-bp fragment of flaB. The ospC primers were 5′-GCCGTGAAAGAAGTTGAGACCTTA-3′ (nucleotides 172 to 195) and 5′-TAAGATTGTCCAGACCAAGCACTG-3′ (nucleotides 448 to 425) and amplified a 276-bp fragment of ospC. Quantitative PCR was performed by adding a known amount of ospC or flaB competitor DNA fragments to different amounts of the cDNA preparations and then performing PCR with flaB or ospC primers (14). The competitor DNA fragment consisted of a 495-bp internal fragment of DNA from the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, which does not have homology to any B. burgdorferi genes, linked to either the flaB or ospC primer sequences. In the PCR in which the competitor and the target PCR products were at similar intensities, the target DNA and competitor DNA were assumed to be present at equimolar concentrations. This information was used to calculate the amount of flaB or ospC mRNA in unfed and feeding ticks.

RESULTS

Titer of OspA antibody required to block transmission from the vector to the host.

We first performed experiments to determine OspA antibody levels required to destroy B. burgdorferi within the feeding ticks and to protect animals from spirochete infection. Groups of mice were passively administered increasing dilutions of hyperimmune OspA antiserum 24 h prior to the placement of 10 B. burgdorferi-infected nymphal ticks on each mouse (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Amount of hyperimmune OspA antiserum required to protect mice from tick-borne B. burgdorferi infectiona

| Antiserum and dilution | Mean circulating C3.78 equivalents (μg/ml) in recipient mice (SD) | No. infected/total (% infected)

|

Mean no. of borreliae per tick (SD)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Ticks | |||

| GST (undiluted) | 0 | 4/4 (100) | 13/13 (100) | 49,000 (23,900) |

| OspA | ||||

| Undilutedc | 216.3 (45.3) | 0/4 (0) | 2/13 (15) | 15 (20)* |

| 1:5 | 48.5 (5.3) | 0/4 (0) | 9/12 (75) | 300 (600)* |

| 1:25 | 6.0 (1.8) | 0/4 (0) | 7/13 (54) | 7,900 (9,100)* |

| 1:50 | 4.5 (0.5) | 4/4 (100) | 12/12 (100) | 8,500 (4,100)* |

| 1:100 | <2 | 4/4 (100) | 12/15 (80) | 29,200 (21,800) |

| 1:200 | <2 | 4/4 (100) | 9/9 (100) | 26,300 (17,700) |

Groups of four mice were passively administered a control antiserum (GST) or different dilutions of hyperimmune OspA antiserum. The antisera were administered by injecting 200 μl (100 μl subcutaneously and 100 μl intraperitoneally) at the appropriate dilution in each mouse. Twenty-four hours after passive immunization, the mice were challenged by placement of 10 nymphal ticks infected with B. burgdorferi B31 on each mouse. At the time of challenge, the mice were bled and the circulating titer of passively administered antibody binding to the C3.78 protective epitope was determined. The ticks were allowed to feed to repletion and detach from the mice. The mice were tested for B. burgdorferi infection by culturing selected organs in BSK II medium as described in Materials and Methods. After the ticks detached, they were tested to determine the prevalence of infected ticks in each group as well as the mean number of spirochetes within individual ticks from each group.

For the OspA antibody-treated groups, an asterisk indicates that the mean number of spirochetes is significantly different from that in the control group (Student’s t test, P < 0.05).

The undiluted hyperimmune OspA antiserum had 6,800 μg of C3.78 antibody equivalents per ml.

In order to accurately correlate immunity with protective antibody levels in vivo, a quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was developed to determine the equivalents of OspA MAb C3.78 (a protective MAb that binds a carboxyl-terminal epitope of OspA) present in sera (see Materials and Methods). As expected, sera from mice immunized with the OspA-GST fusion protein had large amounts of C3.78 MAb equivalents (6,800 μg/ml), and the number of C3.78 MAb equivalents declined linearly when the sera were diluted (data not shown). Moreover, when OspA antiserum was administered to mice, circulating C3.78 MAb equivalents were approximately 30-fold less than in the initial OspA antiserum, reflecting the dilution of 200 μl of serum into approximately 6 ml of murine blood and interstitial fluid (Table 1). Recipient mice were also tested for C3.78 MAb equivalents on day 4 (when ticks had fed to repletion), and the levels did not appreciably decrease at this time point (data not shown).

We then determined the C3.78 MAb equivalents required to protect mice from tick-borne infection (Table 1). One month after tick challenge, the mice were sacrificed and tested for B. burgdorferi infection. Mice receiving OspA antiserum dilutions of up to 1:25 (mean C3.78 MAb equivalents of 6 μg/ml) were protected from infection. However, when sera were used at dilutions of ≥1:50 (mean C3.78 equivalents of 4.5 μg/ml), all of the mice were infected. These data indicate that circulating OspA antibody titers of C3.78 equivalents of 6 μg/ml or greater were required to protect mice from tick challenge. At C3.78 MAb concentrations of below 4.5 μg/ml all of the mice were infected.

Titer of OspA antibody required to clear B. burgdorferi within the vector.

Engorged ticks recovered from the mice treated with different concentrations of OspA antiserum were also examined to determine the prevalence of infection after feeding (Table 1). As expected, all of the ticks that fed on a control mouse were culture positive for B. burgdorferi. Spirochetes were eradicated from the majority of ticks that fed on mice administered undiluted OspA antiserum (Table 1). Surprisingly, the majority of ticks that had fed on animals given a 1:5 or 1:25 dilution of OspA antiserum, levels found to be fully protective against murine infection, were culture positive for B. burgdorferi. Thus, it was not necessary to eradicate infection in the vector in order to protect the host.

Although the majority of ticks feeding on mice treated with 1:5 and 1:25 dilutions of OspA antiserum remained infected, they may not have transmitted spirochetes to the host, because OspA antibody might have severely reduced the number of bacteria within the ticks. To assess the impact of OspA antibodies on the intensity of tick infection, the mean number of spirochetes within a subset of ticks recovered from each group, 3 days after engorgement, was determined (Table 1). Ticks recovered from mice treated with a control antiserum had a mean of 49,000 spirochetes per nymph, while in the OspA antibody-treated groups, the mean number of spirochetes per nymph ranged from 15 in the group treated with undiluted OspA antiserum to 29,200 in the group treated with the 1:100 dilution. A clear decrease in the intensity of tick infection was noted with increasing concentrations of OspA antibody. No significant difference (by Student’s t test, P = 1) was noted, however, for the mean number of spirochetes within the vector between the 1:25 dilution group (7,900), in which all of the mice were protected, and the 1:50 dilution group (8,500), in which all of the mice were infected.

Experiments were then performed to further explore why mice treated with a 1:25 dilution of OspA antiserum were completely protected from infection while mice treated with a 1:50 dilution were susceptible, despite a lack of difference in the intensity of B. burgdorferi infection in ticks recovered from the two groups. Spirochete transmission to the host occurs at approximately 2 to 3 days after tick attachment, and there may be differences at this critical time for transmission that are not apparent 3 days after detachment (the time at which the intensity of infection in the tick was assessed in the first experiment). Groups of four mice were therefore treated with a 1:10, 1:25, 1:50, or 1:200 dilution of OspA antiserum 24 h prior to the placement of 10 infected nymphal ticks on each animal. Sixty hours into the blood meal, the feeding ticks were removed from the mice to estimate the mean number of spirochetes within ticks from each group (Table 2). Unlike the case for the ticks assessed at 3 days after engorgement, a twofold difference in the severity of infection was observed in ticks recovered from mice treated with dilutions above (≥1:50) and below (≤1:25) the critical threshold required to protect mice from infection (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Spirochete number and OspC production within ticks feeding on mice treated with OspA antiseruma

| OspA antiserum dilution | Mean no. of borreliae per tick (SD)b | No. of spirochetes producing OspC/total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1:10 | 12,100 (6,087) | 1/54 (2) |

| 1:25 | 54,900 (5,948)* | 12/73 (16) |

| 1:50 | 107,300 (8,928)* | 26/62 (42) |

| 1:200 | 172,000 (20,736) | 38/70 (54) |

Groups of four mice were passively administered hyperimmune OspA antiserum at different dilutions as described in Table 1, footnote a. Twenty-four hours after passive immunization, B. burgdorferi-infected nymphal ticks were placed on the mice and allowed to feed. Sixty hours into the blood meal, 20 feeding nymphs were removed from the mice in each group, homogenized, and prepared for staining with fluorescently labeled antibodies to count the mean number of spirochetes per nymph. The proportion of spirochetes in each group producing OspC was determined by performing double-labeling immunofluorescence with an OspC antiserum and an antiserum developed against whole spirochetes. In each group, 50 to 75 individual spirochetes staining with the B. burgdorferi antiserum (FITC channel) were examined for labeling with the OspC antiserum (rhodamine channel) to determine the percentage of spirochetes producing OspC.

The mean numbers of spirochetes in the two groups marked with asterisks are significantly different from one another (Student’s t test, P < 0.05).

Salivary gland infections in ticks containing reduced numbers of spirochetes.

Experiments were next done to identify the barrier that prevented ticks with reduced numbers of B. burgdorferi organisms from successfully infecting mice. For many vector-borne pathogens transmitted by a salivary route, the gut epithelium acts as a major barrier to effective transmission. It is conceivable that under conditions of reduced spirochete numbers in the tick, B. burgdorferi may not be able to cross the gut epithelium and infect the salivary glands of the tick. Four groups of two mice each were immunized passively with 200 μl of a control antiserum or hyperimmune OspA antiserum at different dilutions prior to the placement of 10 infected ticks on each mouse. Sixty hours into the blood meal, ticks were removed and the salivary glands were dissected and examined for spirochetes by fluorescent-antibody staining and confocal microscopy as previously described (5). Salivary glands were scored as infected if at least one gland from a pair contained spirochetes. From the groups treated with 1:5 and 1:25 OspA antiserum dilutions, none of the ticks (0 of 23) had salivary glands containing spirochetes. In contrast 25% of the ticks (2 of 8) recovered from the 1:50 dilution group and 100% of the ticks (10 of 10) recovered from the control antiserum-treated group had infected salivary glands. Thus, 60 h into the blood meal, salivary gland infections were detected only in ticks that transmitted B. burgdorferi to mice. These data indicate that under conditions of reduced spirochete numbers in the vector, the tick gut may act as a barrier that prevents salivary gland invasion and host infection.

ospC expression within ticks with reduced numbers of spirochetes.

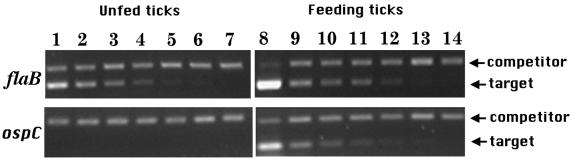

During transmission from the vector to the host, under normal conditions, the number of B. burgdorferi organisms increases exponentially within engorging ticks (5). Furthermore, spirochetes within feeding ticks upregulate the synthesis of OspC (17). Experiments were done to determine if the increase in the synthesis of the OspC protein is initiated by increased transcription of the ospC gene. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to estimate the amounts of ospC and flaB mRNAs within unfed and partially engorged (60-h) ticks. mRNA for flaB, which is most likely a constitutively expressed gene, was detected in both flat and feeding ticks (Fig. 1). Unfed ticks had 3 fg of flaB cDNA per tick, and feeding ticks had 88 fg of flaB per tick. This increase in flaB cDNA is due to the increase in the number of spirochetes during tick feeding. In contrast to flaB mRNA, ospC mRNA was not expressed by spirochetes in unfed ticks, and it was induced upon tick feeding. While unfed ticks did not have detectable ospC cDNA, feeding ticks had 10 fg of ospC cDNA per tick. The sensitivity of the ospC RT-PCR assay was 0.12 fg of cDNA per tick. Therefore, during tick feeding the amount of ospC cDNA was increased by at least 80-fold. The increase in ospC expression was therefore due to the induction of the ospC gene and not simply due to the 30-fold increase in spirochete numbers. These data indicate for the first time that the differential production of OspC protein by spirochetes within feeding ticks (17) is regulated at the level of transcription.

FIG. 1.

Expression of flaB and ospC by spirochetes within feeding ticks. RNA was prepared from B. burgdorferi-infected nymphal ticks that had not fed (unfed ticks) or that had fed for 60 h (feeding ticks). Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out with flaB and ospC primers to estimate the levels of flaB and ospC expression by spirochetes in ticks. Quantitative PCR was performed by adding a known constant amount of ospC or flaB competitor DNA fragments to decreasing amounts of the cDNA preparations and then performing PCR with flaB or ospC primers. Each PCR mixture for flaB (top panels) contained 14 fg of the flaB competitor, and each mixture for ospC (bottom panels) contained 3.5 fg of the ospC competitor. The cDNA preparations from unfed and partially fed ticks were diluted to obtain decreasing cDNA concentrations in the PCR. Lanes 1 to 6, samples with cDNA from unfed ticks that were undiluted and diluted 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, and 1:32, respectively. Lanes 8 to 13, samples with cDNA from partially fed ticks that were undiluted and diluted 1:30, 1:60, 1:120, 1:240, and 1:480, respectively. No cDNA was added to lanes 7 and 14. Because the number of spirochetes increases during tick feeding, it was necessary to dilute the cDNA from feeding ticks more than the cDNA from unfed ticks to be within the sensitive range of the assay. In each panel the higher band corresponds to the amplified competitor, while the lower band corresponds to the amplified target. For each panel, in the lane in which the competitor and the target PCR products were at similar intensities, the amounts of target DNA and competitor DNA were assumed to be present at equimolar concentrations. Unfed ticks had 3 fg of flaB cDNA per tick, and feeding ticks had 88 fg of flaB per tick. Unfed ticks did not have detectable ospC cDNA, and feeding ticks had 10 fg of ospC cDNA per tick. The sensitivity of the ospC RT-PCR was 0.12 fg of cDNA.

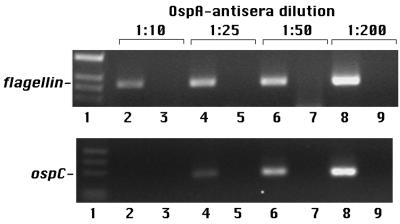

Having established that ospC transcription is induced by spirochetes within feeding ticks, we performed experiments to characterize ospC expression within feeding ticks containing different numbers of bacteria due to OspA antibody treatment. flaB mRNA was detected in all four groups of ticks that had fed for 60 h and contained different numbers of bacteria (Fig. 2). Thus, flaB is expressed irrespective of the spirochete number. In contrast to the case for flaB, strong ospC expression was detected only in ticks (1:50 and 1:200 OspA antiserum dilution treatment groups) that had high numbers of bacteria that invaded the salivary glands and infected the host. A weak ospC band was present in the 1:25 dilution group, and ospC expression was not detected in the 1:10 dilution treatment group. These RT-PCR results were also confirmed by immunofluorescence experiments (Table 2). Double-labeling experiments were done with antiserum raised against whole spirochetes as well as specific antiserum raised against OspC, to detect OspC production by spirochetes within ticks containing different numbers of Borrelia organisms. In the groups treated with 1:200 and 1:50 dilutions of OspA antiserum, 54 and 42% of the spirochetes, respectively, synthesized OspC at 60 h into the blood meal (Table 2). A reduction in the proportion of Borrelia producing OspC was observed within feeding ticks containing reduced numbers of spirochetes due to OspA antiserum treatment (Table 2). Only 16 and 2% of spirochetes within ticks recovered from the 1:25 and 1:10 OspA antiserum dilution treatment groups, respectively, synthesized OspC. Thus, the induction of ospC was markedly decreased in spirochetes that were unable to attain high numbers during tick feeding.

FIG. 2.

Expression of flaB and ospC by feeding ticks containing different numbers of spirochetes due to OspA antibody treatment. Groups of mice were passively immunized with 200 μl of hyperimmune OspA antiserum at dilutions of 1:10 (lanes 2 and 3), 1:25 (lanes 4 and 5), 1:50 (lanes 6 and 7), and 1:200 (lanes 8 and 9) prior to challenge with B. burgdorferi-infected ticks. Sixty hours into the blood meal, 60 ticks were removed from mice in each group and RNA was prepared for RT-PCR with flaB (upper panel) or ospC (lower panel) primers. Lanes 1, DNA molecular weight markers; lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9, samples used in PCR without reverse transcription; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, samples used in PCR after reverse transcription. Amplified products were observed only in samples that had been reverse transcribed, indicating that the RNA preparations were not contaminated with DNA. flaB expression was detected in ticks recovered from all four groups, while strong ospC expression was detected in the 1:50 and 1:200 dilution groups. Weak ospC expression was detected in the 1:25 dilution group, and ospC expression was not evident in the 1:10 dilution group. In these cDNA preparations, not enough flaB and ospC cDNAs were available for quantitative PCR studies.

DISCUSSION

The OspA Lyme disease vaccine is unique in that OspA antibodies target spirochetes in the guts of feeding ticks and block transmission to the host. Protection of the immunized host will depend on circulating levels of OspA antibody which enter the tick gut at the beginning of the blood meal. The data reported here demonstrate that during tick-borne transmission, protection of the immunized host was dependent on the circulating OspA antibody titer. Even a small drop in titer from a mean of 6.0 to 4.5 μg/ml (C3.78 equivalents) led to infection of mice (Table 2). Thus, hosts receiving the OspA vaccine need to maintain a critical circulating titer of OspA antibody, and immunized hosts may have to be boosted at regular intervals to maintain protective titers. In fact, in a recent phase 3 clinical trial of a recombinant OspA Lyme disease vaccine, people who were infected after receiving the vaccine had lower titers of protective antibody than those who were not infected after receiving it (20).

Surprisingly, the antibody concentration required to protect mice was much lower than the concentration required to eradicate spirochetes from feeding ticks. When an infected nymphal tick attaches to a host and begins to feed, the number of B. burgdorferi organisms within the tick increases, and the spirochetes induce ospC (1, 5, 15, 17). At 48 h into the blood meal, the bacteria invade the salivary glands of the tick and infect the host (1, 7, 13, 15, 22). The host protease plasminogen, which is present in the blood meal, binds to spirochetes in the tick gut and appears to enhance the ability of spirochetes to invade salivary glands (4). The data reported in this study indicate that mere suppression of spirochete numbers within the feeding vector, and not total eradication, was sufficient for preventing transmission. In feeding ticks with reduced spirochete numbers, even though large numbers of B. burgdorferi organisms were present within the vector, a specific defect in the induction of ospC and in salivary gland invasion was noted. The fact that the spirochetes failed to infect salivary glands under conditions of limited ospC induction may indicate that this protein plays a pivotal role in salivary gland invasion. Alternatively, this may be only a correlation, and the failure to infect salivary glands may be due to phenotypic changes associated with the expression of other genes or to OspA antibody directly interfering with the ability of spirochetes to invade the salivary glands.

Irrespective of whether OspC is directly involved in salivary gland invasion, it was interesting that feeding ticks with reduced numbers of bacteria failed to efficiently induce ospC. Previous studies have demonstrated that exposing culture-grown spirochetes to an increase in temperature leads to a partial induction of ospC (21). However, temperature alone cannot be the signal for ospC induction in ticks, because feeding ticks in our experiments with reduced spirochete numbers failed to induce ospC even though they were exposed to the same temperature increase as ticks with higher B. burgdorferi numbers that induced ospC. Schwan and colleagues have also reported that simply raising the temperature of infected nymphal ticks to 37°C was not sufficient for OspC synthesis (17). Our data indicate that the ability of spirochetes to multiply unhindered in the vector and/or the ability to reach a critical density was required for triggering ospC expression. Indest and colleagues recently provided evidence for cell density-dependent expression of another Borrelia lipoprotein in vitro (11). Those investigators characterized a 35-kDa antigen of B. burgdorferi that was upregulated by culture-grown organisms as they increased in density and approached stationary-phase growth. Therefore, B. burgdorferi may be able to alter its phenotype in response to changes in population density by using quorum-sensing mechanisms similar to those described for other bacteria (10).

The exact mechanism by which OspA antibodies in the tick gut block transmission remains to be worked out. OspA antibodies may directly interfere with the transmission process by binding to the surface of live Borrelia and blocking critical interactions required for transmission. Alternately, OspA antibodies in the tick gut may prevent the bacteria from reaching a critical density that triggers the expression of genes required for Borrelia to invade the salivary glands of the vector and infect the host. Future studies will focus on better delineating the mechanism by which OspA antibodies block transmission from the vector to the host.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI-45253 and AI-49387), the Arthritis Foundation, the American Heart Association, and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (DF95-034).

REFERENCES

- 1.Benach J L, Coleman J L, Skinner R A, Bosler E M. Adult Ixodes dammini on rabbits: a hypothesis for the development and transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1300–1306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgdorfer W, Anderson J F, Gern L, Lane R S, Piesman J, Spielman A. Relationship of Borrelia burgdorferi to its arthropod vectors. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1991;77:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman J L, Gebbia J A, Piesman J, Degan J L, Bugge T H, Benach J L. Plasminogen is required for efficient dissemination of B. burgdorferi in ticks and for enhancement of spirochetemia in mice. Cell. 1997;89:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Silva A M, Fikrig E. Growth and migration of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ticks during blood feeding. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:397–404. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Silva A M, Fikrig E. Arthropod and host-specific gene expression by Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:377–379. doi: 10.1172/JCI119169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Silva A M, Telford S R, Brunet L R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1996;183:271–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan M C, Maupin G O, Panella N A, Golde W T, Piesman J. Vector competence of Ixodes scapularis, I. spinipalpis, Dermancentor andersoni (Acari: Ixodidae) in transmitting Borrelia burgdorferi, the etiological agent of Lyme disease. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:128–135. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Kantor F S, Flavell R A. Protection of mice against the Lyme disease agent by immunizing with recombinant OspA. Science. 1990;250:553–556. doi: 10.1126/science.2237407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuqua C, Winans S C, Greenberg E P. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:727–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indest K J, Ramamoorthy R, Sole M, Gilmore R D, Johnson B J B, Philipp M T. Cell-density-dependent expression of Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins in vitro. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1165–1171. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1165-1171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery R B, Malawista S E, Feen K J M, Bockenstedt L K. Direct demonstration of antigenic substitution of Borrelia burgdorferi ex vivo: exploration of the paradox of the early immune response to outer surface proteins A and C in Lyme disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183:261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piesman J. Dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi transmission by nymphal Ixodes dammini ticks. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1082–1085. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiner S L, Zheng S, Corry D B, Locksley R M. Constructing polycompetitor cDNAs for quantitative PCR. J Immunol Methods. 1994;175:275. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90104-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribeiro J M, Mather T N, Piesman J, Spielman A. Dissemination and salivary delivery of Lyme disease spirochetes in vector ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) J Med Entomol. 1987;24:201–205. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaible U E, Kramer M D, Eichmann K, Modolell M, Museteanu C, Simon M M. Monoclonal antibodies specific for the outer surface protein A (OspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi prevent Lyme borreliosis in severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3768–3772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwan T G, Piesman J, Golde W T, Dolan M C, Rosa P A. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2909–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sears J, Fikrig E, Nakagawa T, Deponte K, Marcantonio N, Kantor F, Flavell R A. Molecular mapping of OspA-mediated protection against Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. J Immunol. 1991;147:1995–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon M M, Schaible U E, Kramer M D, Eckerskorn C, Museteanu C, Muller-Hermelink H K, Wallich R. Recombinant outer surface protein A from Borrelia burgdorferi induces antibodies protective against spirochetal infection in mice. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:123–132. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steere A C, Sikand V K, Meurice F, Parenti D L, Fikrig E, Schoen R T, Nowakowski J, Schmid C H, Laukamp S, Buscarino C, Krause D S. Vaccination against lyme-disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevenson B, Schwan T G, Rosa P. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4535–4539. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4535-4539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zung J L, Lewengrub S, Rudzibnska M A, Spielman A, Telford S R, Piesman J. Fine structural evidence for the penetration of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi through the gut and salivary tissues of Ixodes dammini. Can J Zool. 1989;67:1737–1748. [Google Scholar]