Key Points

Question

What is the estimated proportion of deaths among US adults aged 20 to 64 years attributable to excessive alcohol consumption, and are there differences by sex, age, and US state?

Findings

The estimates in this cross-sectional study of 694 660 mean deaths per year between 2015 and 2019 suggest that excessive alcohol consumption accounted for 12.9% of total deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years and 20.3% of deaths among adults aged 20 to 49 years. Among adults aged 20 to 64 years, the proportion of alcohol-attributable deaths to total deaths varied by state.

Meaning

These findings suggest that an estimated 1 in 8 deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years were attributable to excessive alcohol use and that greater implementation of evidence-based alcohol policies could reduce this proportion.

This cross-sectional study estimates the mean annual number of deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years overall; by sex, age group, and US state; and as a proportion of total deaths.

Abstract

Importance

Alcohol consumption is a leading preventable cause of death in the US, and death rates from fully alcohol-attributable causes (eg, alcoholic liver disease) have increased in the past decade, including among adults aged 20 to 64 years. However, a comprehensive assessment of alcohol-attributable deaths among this population, including from partially alcohol-attributable causes, is lacking.

Objective

To estimate the mean annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use relative to total deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years overall; by sex, age group, and state; and as a proportion of total deaths.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cross-sectional study of mean annual alcohol-attributable deaths among US residents between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019, used population-attributable fractions. Data were analyzed from January 6, 2021, to May 2, 2022.

Exposures

Mean daily alcohol consumption among the 2 089 287 respondents to the 2015-2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System was adjusted using national per capita alcohol sales to correct for underreporting. Adjusted mean daily alcohol consumption prevalence estimates were applied to relative risks to generate alcohol-attributable fractions for chronic partially alcohol-attributable conditions. Alcohol-attributable fractions based on blood alcohol concentrations were used to assess acute partially alcohol-attributable deaths.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Alcohol-attributable deaths for 58 causes of death, as defined in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact application. Mortality data were from the National Vital Statistics System.

Results

During the 2015-2019 study period, of 694 660 mean deaths per year among adults aged 20 to 64 years (men: 432 575 [66.3%]; women: 262 085 [37.7%]), an estimated 12.9% (89 697 per year) were attributable to excessive alcohol consumption. This percentage was higher among men (15.0%) than women (9.4%). By state, alcohol-attributable deaths ranged from 9.3% of total deaths in Mississippi to 21.7% in New Mexico. Among adults aged 20 to 49 years, alcohol-attributable deaths (44 981 mean annual deaths) accounted for an estimated 20.3% of total deaths.

Conclusions And Relevance

The findings of this cross-sectional study suggest that an estimated 1 in 8 total deaths among US adults aged 20 to 64 years were attributable to excessive alcohol use, including 1 in 5 deaths among adults aged 20 to 49 years. The number of premature deaths could be reduced with increased implementation of evidenced-based, population-level alcohol policies, such as increasing alcohol taxes or regulating alcohol outlet density.

Introduction

Excessive alcohol use is associated with several leading causes of death among adults aged 20 to 64 years in the US, including heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, and liver disease.1 Excessive alcohol use is a leading preventable cause of premature death,2 and rates of deaths due to fully alcohol-attributable causes (eg, alcoholic liver disease) have increased in the past decade, including among adults aged 20 to 64 years.3 However, a US-based assessment of alcohol-attributable deaths among this population that also accounts for partially alcohol-attributable causes (eg, cancers) is lacking. Using the conditions in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application,4 this study estimated the mean annual number of deaths due to excessive alcohol use among adults aged 20 to 64 years overall; by sex, age group, and US state; and as a proportion of total deaths.

Methods

Mean annual national and state mortality data from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019, were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System, WONDER,5 and the ARDI application for the 58 alcohol-related causes. In addition to deaths due to fully alcohol-attributable causes, deaths due to partially alcohol-attributable conditions were calculated in the ARDI application using cause-specific, alcohol-attributable fractions (AAFs) for select acute (eg, injuries) and chronic (eg, cancers) conditions (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Deaths due to acute conditions were calculated using direct AAFs based on high blood alcohol concentrations (eg, ≥0.10 g/dL). Deaths due to 23 chronic conditions were calculated using indirect AAFs, which include the prevalence of mean daily alcohol consumption levels and cause-specific relative risks that corresponded to those consumption levels.6 To account for substantial underreporting of alcohol consumption in nationwide surveys, the same methodology as in the ARDI application was used to adjust alcohol consumption from 2 089 287 respondents to the 2015-2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.6 Consumption was adjusted to 73% of national per capita alcohol sales (from tax and shipment data in the Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System) to align with alcohol use reported in US epidemiologic cohort studies.7 This study estimated deaths due to excessive alcohol consumption; therefore, for chronic conditions, the adjusted prevalence of medium (>1 to ≤2 alcoholic drinks for women or >2 to ≤4 drinks for men) and high (>2 alcoholic drinks for women or >4 drinks for men) mean daily alcohol consumption (eTable 2 in the Supplement) were applied to relative risks to generate cause-specific AAFs.4 Alcohol-attributable fractions and relative risks are generally not available by race and ethnicity, and alcohol attribution to deaths might differ across these groups; therefore, deaths in this study were not estimated by race and ethnicity. Because data were deidentified and secondary analyses were performed, institutional review board oversight and informed consent were not required as determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under 45 CFR 46. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Analyses of alcohol consumption prevalence were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). We used the ARDI application to assess the mean annual number of deaths due to excessive drinking and the leading causes of death.4 Alcohol-attributable deaths were calculated as a percentage of total deaths overall and by sex, age, and US state. Alcohol-attributable death rates per 100 000 population were assessed using US Census population counts from WONDER.5

Results

Our findings suggest that an estimated annual mean of 140 557 deaths (men: 97 182 [69.1%]; women: 43 375 [30.9%]) could be attributed to excessive alcohol consumption in the US during the 2015-2019 study period, accounting for 5.0% of total deaths (Table 1). Among all adults aged 20 to 64 years, 694 660 annual mean total deaths were noted (men: 432 575 [66.3%]; women: 262 085 [37.7%]), and an estimated 89 697 of these (12.9%) were alcohol-attributable (64 998 [15.0%] among men and 24 699 [9.4%] among women). Our analysis showed that although the number and rate of alcohol-attributable deaths per 100 000 increased by age group, alcohol-attributable deaths accounted for a larger proportion of total deaths among younger groups: 19 782 of 77 973 total deaths (25.4%) among adults aged 20 to 34 years and 25 199 of 143 663 (17.5%) among those aged 35 to 49 years. The 3 leading causes of alcohol-attributable deaths by age group were the same for men and women (eg, adults aged 20-34 years: other poisonings, motor vehicle traffic crashes, and homicide; adults aged 35-49 years: other poisonings, alcoholic liver disease, and motor vehicle traffic crashes).

Table 1. Mean Annual Total and Estimated Alcohol-Attributable Deaths in the US, 2015 to 2019a.

| Sex by age group, y | Total No. of all-cause deaths | Deaths due to excessive alcohol usea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of deaths (%)b | Rate per 100 000 population | 3 Leading causes (No. of deaths)c | ||

| Men and women | ||||

| All | 2 792 885 | 140 557 (5.0) | 43.2 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 22 472); other poisonings (n = 17 671); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 12 650) |

| 20-64 | 694 660 | 89 697 (12.9) | 46.7 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 17 129); other poisonings (n = 16 609); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 10 627) |

| 20-34 | 77 973 | 19 782 (25.4) | 29.4 | Other poisonings (n = 5537); motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 4707); and homicide (n = 3911) |

| 35-49 | 143 663 | 25 199 (17.5) | 40.8 | Other poisonings (n = 6085); alcoholic liver disease (n = 4605); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 3100) |

| 50-64 | 473 024 | 44 716 (9.5) | 70.8 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 11 709); other poisonings (n = 4987); and unspecified liver cirrhosis (n = 3878) |

| Men | ||||

| All | 1 429 008 | 97 182 (6.8) | 60.7 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 15 614); other poisonings (n = 12 014); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 9590) |

| 20-64 | 432 575 | 64 998 (15.0) | 68.0 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 11 601); other poisonings (n = 11 337); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 8227) |

| 20-34 | 55 306 | 15 147 (27.4) | 44.2 | Other poisonings (n = 3990); motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 3607); and homicide (n = 3323) |

| 35-49 | 89 723 | 17 846 (19.9) | 58.1 | Other poisonings (n = 4131); alcoholic liver disease (n = 2945); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 2395) |

| 50-64 | 287 546 | 32 005 (11.1) | 104.3 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 8155); other poisonings (n = 3216); and unspecified liver cirrhosis (n = 2395) |

| Women | ||||

| All ages | 1 363 877 | 43 375 (3.2) | 26.3 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 6857); hypertension (n = 6808); and other poisonings (n = 5656) |

| 20-64 | 262 085 | 24 699 (9.4) | 25.6 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 5527); other poisonings (n = 5273); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 2399) |

| 20-34 | 22 667 | 4635 (20.4) | 14.0 | Other poisonings (n = 1547); motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 1100); and homicide (n = 588) |

| 35-49 | 53 940 | 7353 (13.6) | 23.7 | Other poisonings (n = 1955); alcoholic liver disease (n = 1660); and motor vehicle traffic crashes (n = 704) |

| 50-64 | 185 478 | 12 711 (6.9) | 39.1 | Alcoholic liver disease (n = 3553); other poisonings (n = 1771); and unspecified liver cirrhosis (n = 1482) |

Consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application,4 data pertain to excessive alcohol use, which includes deaths due to (1) conditions that are 100% alcohol-attributable, (2) acute conditions that involved binge drinking, and (3) chronic conditions that involved medium (>1 to ≤2 alcoholic drinks for women or >2 to ≤4 drinks for men) or high (>2 alcoholic drinks for women or >4 drinks for men) levels of mean daily alcohol consumption. Numbers may not sum to totals due to rounding.

For underlying chronic causes of death that were estimated in the ARDI application using indirect alcohol-attributable fractions that account for the risk of dying at 3 levels of mean daily alcohol consumption, self-reported mean daily alcohol consumption was adjusted to account for 73% of per capita alcohol sales.7

Other poisonings (eg, drug overdoses) indicates deaths involving another substance in addition to a high blood alcohol concentration (≥0.10 g/dL).

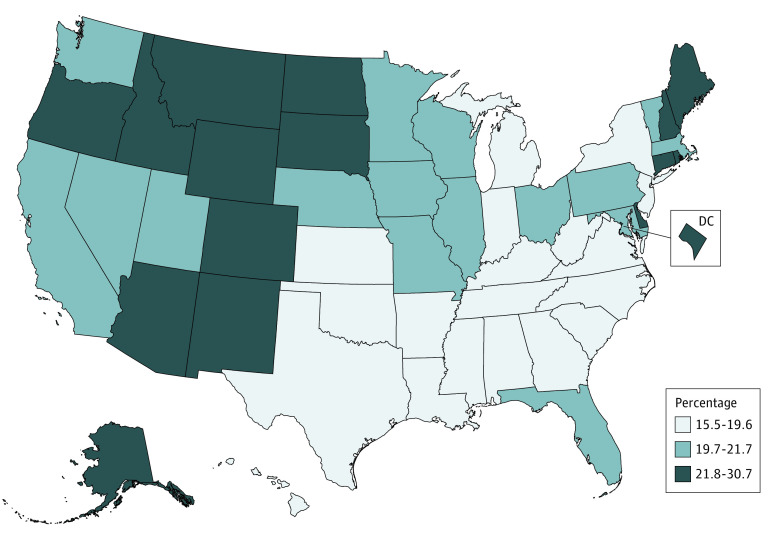

By state, alcohol-attributable deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years ranged from 9.3% of total deaths in Mississippi to 21.7% in New Mexico (Table 2). State-level variations were found by age group (eg, the proportion of alcohol-attributable deaths to total deaths among adults aged 20-34 years ranged from 22.4% in Utah to 33.3% in New Mexico). Among adults aged 20 to 49 years, our estimates suggest that excessive drinking was responsible for 44 981 mean annual deaths, or 20.3% of total deaths. This percentage was generally lower in states in the Southeast and higher in the West, upper Midwest, and New England (Figure).

Table 2. Estimated Alcohol-Attributable Deaths and Percentage of Total Deaths Among Adults Aged 20 to 64 Years by State and Age Group.

| Location | Age group, No. of deaths due to excessive alcohol use (% of total deaths)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-34 y | 35-49 y | 50-64 y | 20-64 y | |

| Entire US | 19 782 (25.4) | 25 199 (17.5) | 44 716 (9.5) | 89 697 (12.9) |

| Stateb | ||||

| Alabama | 381 (24.2) | 443 (13.8) | 665 (6.5) | 1489 (9.9) |

| Alaska | 86 (29.6) | 97 (26.3) | 149 (14.5) | 332 (19.7) |

| Arizona | 512 (27.3) | 707 (22.5) | 1148 (12.2) | 2367 (16.4) |

| Arkansas | 195 (23.2) | 266 (14.6) | 426 (7.1) | 887 (10.3) |

| California | 1880 (25.8) | 2578 (19.2) | 5051 (11.6) | 9509 (14.8) |

| Colorado | 390 (28.5) | 536 (24.2) | 902 (14.0) | 1828 (18.2) |

| Connecticut | 195 (26.6) | 262 (19.8) | 466 (10.5) | 923 (14.2) |

| Delaware | 78 (27.7) | 89 (19.1) | 148 (9.8) | 315 (13.9) |

| Florida | 1328 (25.6) | 1700 (18.0) | 3407 (10.6) | 6435 (13.7) |

| Georgia | 620 (23.5) | 721 (14.0) | 1272 (7.7) | 2613 (10.7) |

| Hawaii | 56 (23.0) | 82 (15.8) | 162 (9.2) | 300 (11.9) |

| Idaho | 87 (25.1) | 129 (20.2) | 240 (11.5) | 456 (14.8) |

| Illinois | 796 (27.1) | 923 (17.7) | 1558 (8.7) | 3277 (12.6) |

| Indiana | 465 (24.7) | 575 (16.7) | 930 (8.3) | 1970 (11.9) |

| Iowa | 133 (24.0) | 202 (17.9) | 409 (9.4) | 744 (12.3) |

| Kansas | 158 (24.1) | 197 (16.8) | 374 (8.6) | 729 (11.8) |

| Kentucky | 317 (23.1) | 476 (15.7) | 733 (7.8) | 1526 (11.1) |

| Louisiana | 408 (25.8) | 454 (16.0) | 716 (7.8) | 1578 (11.6) |

| Maine | 78 (26.1) | 121 (20.0) | 226 (10.2) | 425 (13.6) |

| Maryland | 467 (27.1) | 476 (17.2) | 755 (8.6) | 1698 (12.8) |

| Massachusetts | 397 (25.2) | 503 (19.4) | 867 (10.5) | 1767 (14.3) |

| Michigan | 626 (24.4) | 799 (17.0) | 1442 (8.8) | 2867 (12.1) |

| Minnesota | 230 (24.1) | 334 (19.2) | 680 (10.8) | 1244 (13.8) |

| Mississippi | 217 (22.5) | 247 (12.2) | 423 (6.4) | 887 (9.3) |

| Missouri | 492 (26.9) | 551 (17.6) | 865 (8.1) | 1908 (12.2) |

| Montana | 83 (30.0) | 113 (24.5) | 194 (12.1) | 390 (16.7) |

| Nebraska | 88 (25.9) | 120 (17.6) | 220 (9.0) | 428 (12.3) |

| Nevada | 178 (25.5) | 278 (19.2) | 525 (11.5) | 981 (14.6) |

| New Hampshire | 91 (25.6) | 119 (20.8) | 218 (11.2) | 428 (14.9) |

| New Jersey | 480 (24.6) | 577 (16.6) | 910 (8.1) | 1967 (11.8) |

| New Mexico | 261 (33.3) | 383 (29.1) | 530 (16.1) | 1174 (21.7) |

| New York | 817 (22.6) | 1060 (15.6) | 1965 (8.2) | 3842 (11.2) |

| North Carolina | 673 (25.3) | 819 (16.3) | 1414 (8.6) | 2906 (12.1) |

| North Dakota | 56 (27.6) | 64 (21.4) | 110 (11.9) | 230 (16.1) |

| Ohio | 871 (24.9) | 1099 (17.3) | 1791 (8.6) | 3761 (12.3) |

| Oklahoma | 273 (24.6) | 400 (17.2) | 724 (9.4) | 1397 (12.6) |

| Oregon | 203 (26.2) | 336 (21.6) | 756 (13.3) | 1295 (16.1) |

| Pennsylvania | 942 (25.8) | 992 (16.9) | 1690 (8.4) | 3624 (12.2) |

| Rhode Island | 59 (27.4) | 90 (21.7) | 160 (11.1) | 309 (14.9) |

| South Carolina | 387 (25.9) | 470 (16.4) | 840 (9.0) | 1697 (12.4) |

| South Dakota | 66 (30.6) | 91 (24.2) | 142 (12.2) | 299 (17.0) |

| Tennessee | 470 (23.1) | 651 (15.4) | 1120 (8.3) | 2241 (11.4) |

| Texas | 1608 (25.8) | 1946 (16.3) | 3416 (9.2) | 6970 (12.6) |

| Utah | 163 (22.4) | 216 (18.7) | 278 (10.2) | 657 (14.3) |

| Vermont | 35 (24.7) | 45 (19.3) | 99 (11.0) | 179 (14.0) |

| Virginia | 454 (25.2) | 533 (15.8) | 981 (8.3) | 1968 (11.6) |

| Washington | 355 (25.2) | 512 (19.5) | 1062 (11.6) | 1929 (14.6) |

| Washington, DC | 61 (30.5) | 63 (18.5) | 133 (11.6) | 257 (15.2) |

| West Virginia | 152 (23.9) | 232 (16.7) | 345 (8.1) | 729 (11.6) |

| Wisconsin | 326 (26.4) | 415 (19.0) | 849 (10.9) | 1590 (14.2) |

| Wyoming | 45 (29.5) | 78 (27.6) | 121 (14.3) | 244 (19.0) |

Mean annual number of alcohol-attributable deaths between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019. Numbers may not sum to totals due to rounding. Consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application,4 data pertain to excessive alcohol use, which includes deaths due to (1) conditions that are 100% alcohol-attributable, (2) acute conditions that involved binge drinking, and (3) chronic conditions that involved medium (>1 to ≤2 alcoholic drinks for women or >2 to ≤4 drinks for men) or high (>2 alcoholic drinks for women or >4 drinks for men) levels of mean daily alcohol consumption. For underlying chronic causes of death that were estimated in the ARDI application using indirect alcohol-attributable fractions that account for the risk of dying at 3 levels of mean daily alcohol consumption, self-reported mean daily alcohol consumption was adjusted to account for 73% of per capita alcohol sales.7

Ranges in percentage of total deaths by state were 22.4% to 33.3% for those aged 20 to 34 years; 12.2% to 29.1% for those aged 35 to 49 years; 6.4% to 16.1% for those aged 50 to 64 years; and 9.3% to 21.7% for those aged 20 to 64 years.

Figure. Estimated Percentage of Total Deaths Attributable to Excessive Alcohol Use Among US Adults Aged 20 to 49 Years, 2015 to 2019.

Discussion

We found that 89 697 of an estimated 140 557 deaths due to excessive alcohol use annually during the 2015-2019 study period, or nearly two-thirds of the deaths, were among adults aged 20 to 64 years. Our estimates suggest that alcohol-attributable deaths were responsible for 1 in 8 deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years, including 1 in 5 deaths among adults aged 20 to 49 years.

Compared with 2019, death rates involving alcohol as an underlying or contributing cause of death increased during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, including among adults aged 20 to 64 years.8 Therefore, the proportion of deaths due to excessive drinking among total deaths might be higher than reported in this study. Nevertheless, these study findings are consistent with the epidemiology of excessive drinking. For example, the prevalence of binge drinking is generally higher among younger adults, and this population tends to consume more alcohol while binge drinking,9 which contributes to their leading causes of alcohol-attributable deaths.

The methods for estimating deaths due to excessive alcohol consumption in this study differ somewhat from those of other studies. From 2006 to 2010, an estimated 1 in 10 deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years was attributable to excessive alcohol consumption.10 That finding was partially based on self-reported mean daily consumption prevalence estimates that were adjusted to account for binge drinking occasions but not per capita alcohol sales. Because survey-based adjustments alone can lead to underestimates of alcohol-attributable deaths that are calculated using indirect AAF methods, this study adjusted self-reported alcohol use data to account for 73% of per capita alcohol sales.7 Global studies estimating alcohol-attributable deaths also adjust using per capita alcohol sales, but they generally adjust to 80%.11 The ARDI methods used in this study provide estimates of deaths pertaining to excessive drinking rather than all levels of consumption. Also, the ARDI application uses direct AAFs for estimating the number of alcohol-attributable deaths due to acute causes. This method differs from those of global studies that estimate alcohol-attributable deaths across all levels of consumption and consistently base estimates on continuous risk functions.11,12

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The alcohol-attributable death estimates in this study may be conservative because they are based on deaths due to alcohol-related conditions that were identified as the underlying cause of death only; contributing causes of death were not included. In addition, alcohol-attributable deaths due to partially alcohol-attributable conditions were not estimated for adults who formerly used alcohol, despite some dying of alcohol-related causes,11 because the prevalence of former alcohol consumption is not collected in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Direct AAFs were used to estimate alcohol-attributable deaths due to acute causes (eg, injuries)6; however, the sources of some AAFs were based on older data that may less accurately represent current alcohol-attribution. Last, some conditions related to alcohol use (eg, HIV/AIDS) were not included because suitable AAFs for the US were not available.

Conclusions

The findings of this cross-sectional study suggest that an estimated 1 in 8 deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 years was attributable to excessive alcohol consumption, including 1 in 5 deaths among adults aged 20 to 49 years. These premature deaths could be reduced through increased implementation of evidence-based alcohol policies (eg, increasing alcohol taxes, regulating alcohol outlet density),13 and alcohol screening and brief intervention.14

eTable 1. ICD-10 Codes and Alcohol-Attributable Fraction Information by Causes of Death in the Alcohol-Related Disease Impact Application

eTable 2. Adjusted Prevalence of US Mean Daily Alcohol Consumption by Level of Consumption and Age Group

eReferences

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . WISQARS injury data. Ten leading causes of death, United States, 2019, both sexes, ages 20-64, all races. Reviewed February 10, 2022. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://wisqars-viz.cdc.gov:8006/

- 2.Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996-2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921451. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application. Updated April 25, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/ardi

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research). Reviewed August 17, 2022. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://wonder.cdc.gov

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . ARDI methods. Reviewed April 19, 2022. Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/ardi/methods.html

- 7.Esser MB, Sherk A, Subbaraman MS, et al. Improving estimates of alcohol-attributable deaths in the United States: impact of adjusting for the underreporting of alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2022;83(1):134-144. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2022.83.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White AM, Castle IP, Powell PA, Hingson RW, Koob GF. Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2022;327(17):1704-1706. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.4308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohm MK, Liu Y, Esser MB, et al. Binge drinking among adults, by select characteristics and state—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(41):1441-1446. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7041a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shield K, Manthey J, Rylett M, et al. National, regional, and global burdens of disease from 2000 to 2016 attributable to alcohol use: a comparative risk assessment study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e51-e61. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30231-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GBD 2020 Alcohol Collaborators . Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):185-235. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00847-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Community Guide. Excessive alcohol consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/excessive-alcohol-consumption

- 14.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1899-1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-10 Codes and Alcohol-Attributable Fraction Information by Causes of Death in the Alcohol-Related Disease Impact Application

eTable 2. Adjusted Prevalence of US Mean Daily Alcohol Consumption by Level of Consumption and Age Group

eReferences