Abstract

Objectives

Acute bronchiolitis is a major public health issue with high number of infants hospitalised worldwide each year. In France, hospitalisations mostly occur between October and March and peak in December. A reduction of emergency visits for bronchiolitis has been observed at onset of the COVID-19 outbreak. We aimed to assess the pandemic effects on the hospitalisations for bronchiolitis during the 2020–2021 winter (COVID-19 period) compared with three previous winters (pre-COVID-19).

Design

Retrospective, observational and cross-sectional study.

Setting

Tertiary university paediatric hospital in Paris (France).

Participants

All infants aged under 12 months who were hospitalised for acute bronchiolitis during the autumn/winter seasons (1 October to 31 March) from 2017 to 2021 were included. Clinical and laboratory data were collected using standardised forms.

Results

During the COVID-19 period was observed, a 54.3% reduction in hospitalisations for bronchiolitis associated with a delayed peak (February instead of November–December). Clinical characteristics and hospitalisation courses were substantially similar. The differences during the COVID-19 period were: smaller proportion of infants with comorbidities (8% vs 14% p=0.02), lower need for oxygen (45% vs 55%, p=0.01), higher proportions of metapneumovirus, parainfluenzae 3, bocavirus, coronavirus NL63 and OC43 (all p≤0.01) and no influenza. The three infants positive for SARS-CoV-2 were also positive for respiratory syncytial virus, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 alone does not cause bronchiolitis, despite previous assumptions.

Conclusion

The dramatic reduction in infants’ hospitalisations for acute bronchiolitis is an opportunity to change our future habits such as advising the population to wear masks and apply additional hygiene measures in case of respiratory tract infections. This may change the worldwide bronchiolitis burden and improve children respiratory outcomes.

Keywords: COVID-19, community child health, respiratory infections

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The vast majority of infants admitted to our paediatric hospital between 2017 and 2021 for acute bronchiolitis in their first year after birth will have been identified.

The clinical and viral characteristics of these infants hospitalised during the COVID-19 epidemic season 2020–2021 were compared with those of three previous winters.

Three physicians independently reviewed the medical records to collect clinical data and laboratory tests results using a standardised-specific form.

Introduction

In autumn and winter in the Northern Hemisphere, community medicine (paediatricians and general practitioners) as well as emergency and general paediatric departments are usually overwhelmed by children, especially infants, with acute bronchiolitis.1 2 Hospital paediatric inpatient departments have to reorganise every winter to handle the high number of infants with this acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI), mostly due to the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).1–5 Neonates and young infants often require hospitalisation in general wards and some even require intensive care unit (ICU) care.2 6 Moreover, RSV is the third leading cause of death in children aged below 5 years (from ALRI, after pneumonia), secondary to Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenzae type b.2 Acute bronchiolitis is thus a yearly worldwide public health issue. In France, similar epidemic patterns are seen each year with a large majority of hospitalisations between October and March, with a peak in December.7 Management is largely supportive, focusing on maintaining oxygenation and hydration.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the global public health responses related to this pandemic have influenced the viruses’ epidemiology. A striking reduction of admission for ALRIs in paediatric ICUs was observed during the winter 2020 in the Southern Hemisphere.8 In France, collective measures to contain the pandemic have been implemented since mid-March 2020, namely lockdowns, curfews, social distancing, requirement of masks, strict hand hygiene and restriction of commerce activities. We observed a reduction in the visits to the paediatric emergency department of our hospital for bronchiolitis in the autumn 2020.9 Here, we aimed to assess the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clinical and viral characteristics of infants hospitalised for bronchiolitis during the epidemic season 2020–2021 (COVID-19 period) compared with previous winters (pre-COVID-19 period).

Methods

Study design and patients

This retrospective, observational and cross-sectional study was conducted in the Paediatric University Hospital Armand Trousseau, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, in Paris (France). All infants aged less than 12 months hospitalised for a first episode of acute bronchiolitis during the autumn/winter seasons (1 October to 31 March) from 2017 to 2021 (ie, 2017–2018; 2018–2019; 2019–2020; and 2020–2021) were included. Exclusion criteria were age over 12 months, a second episode (or more) of bronchiolitis and/or an asthma attack. These exclusion criteria were chosen based on the French National Guidelines for bronchiolitis.10

Patient’s selection was performed using the ICD10 code diagnoses of bronchiolitis (J21.0, J21.1, J21.8 and J21.9). Three physicians reviewed the medical records to collect demographic and clinical data as well as laboratory tests results using a standardised-specific form. The demographic data collected comprised date of birth, gender and underlying conditions such as prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, intrauterine growth retardation, congenital heart disease, sickle cell disease and genetic disease. The clinical data collected at the time of the bronchiolitis episode included date, age, weight, results of the PCR in nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates for virus identification (Allplex Respiratory Panel Assays (Seegene), and/or Simplexa Flu A/B & RSV Direct Gen II Kit (Diasorin Molecular)), and medical evolution with duration of the hospitalisation, hopitalisation in ICU, respiratory support (oxygen therapy, high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation, invasive ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and nutritional support.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the distribution for continuous variables was tested using the Shapiro-wilk test and was rejected for each variable. Patients’ characteristics were described as medians with IQR for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. We compared the patients’ characteristics between the pre-COVID-19 periods, defined as 1 October to 31 March 2017–2018, 2018–2019 and 2019–2020, with those of the COVID-19 period, defined as 1 October 2020 to 31 March 2021 by using a χ2 test for categorical variables and a Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The analyses were performed using STATA V.14.2.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Number of hospitalisations

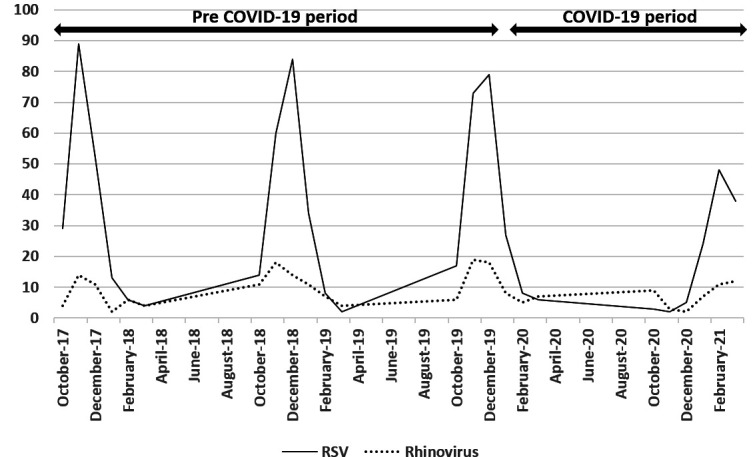

Over the pre-COVID-19 period, 1347 infants were hospitalised for bronchiolitis in our hospital, with a mean of 449 infants per winter, compared with 205 infants during the COVID-19 period; which corresponds to a 54.3% reduction in the number of hospitalisations (table 1). As shown in figure 1, the bronchiolitis outbreak was delayed during the COVID-19 period, with a peak in the hospitalisations in February, compared with the usual peaks in November–December during the pre-COVID-19 periods.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the infants hospitalised for acute bronchiolitis in a tertiary university paediatric hospital in Paris (France) between 2017 and 2021

| Pre-COVID-19 period | COVID-19 period | P value* | ||||

| 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2017–2020 aggregated data | 2020–2021 | ||

| Infants, n | 479 | 451 | 417 | 1347 | 205 | – |

| Age (months): median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.5–4.9) | 2.6 (1.4–4.8) | 2.4 (1.3–4.4) | 2.5 (1.4–4.7) | 2.7 (1.5–4.7) | 0.7 |

| Gender: boys, n (%) | 279 (58.2) | 249 (55.2) | 244 (58.5) | 772 (57) | 119 (58) | 0.5 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 66 (14) | 66 (15) | 53 (13) | 185 (14) | 16 (8) | 0.02 |

| Weight (kg): median (IQR) | 5.6 (4.4–6.9) | 5.5 (4.6–7.0) | 5.4 (4.3–7.0) | 5.5 (4.4–7.0) | 5.7 (4.5–6.9) | 0.6 |

| Evolution | ||||||

| Duration of hospitalisation (days), median (IQR) | 2.4 (1.2–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.9 (2.0–5.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.9) | 3.0 (1.5–4.2) | 0.3 |

| Oxygen therapy, n (%) | 259 (54) | 237 (52) | 257 (61) | 753 (56) | 93 (45) | 0.01 |

| Intensive care unit, n (%) | 48 (13) | 42 (9) | 67 (16) | 157 (12) | 21 (11) | 0.6 |

| Non-invasive ventilation, n (%) | 42 (8) | 38 (8) | 67 (16) | 147 (11) | 22 (12) | 0.9 |

| Invasive ventilation, n (%) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 7 (1.6) | 17 (1.2) | 3 (1.7) | 0.6 |

| Extracorporeal circulation, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.4 |

*P value for the comparison between pre-COVID-19 aggregated data and COVID-19 data using χ2 test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the number of RSV and rhinovirus cases during the pre-COVID-19 period (between 2017 and 2020) and the COVID-19 period (2020–2021).

Characteristics of the patients

The clinical characteristics of the infants hospitalised for bronchiolitis are shown in table 1. The age distribution and the sex ratio were not significantly different between the pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 periods (p=0.7 and 0.5, respectively). During the pre-COVID-19 periods, 14% of the infants presented with comorbidities (with 11% of preterm), whereas only 8% had comorbidities during the COVID-19 period, (p=0.02).

The number of infants who received oxygen therapy was significantly lower during the COVID-19 period than during the pre-COVID-19 period (45% and 55%, respectively, p=0.01). There were no significant differences between the pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 periods regarding the length of hospitalisation (p=0.3), the number of patients transferred to a paediatric ICU (p=0.6) and the need for non-invasive (p=0.9) or invasive ventilation (p=0.6).

Viral epidemiology

PCR in nasopharyngeal swabs for virus identification were performed increasingly across the years (p<0.01) (table 2). RSV remains the most common virus found (74%), followed by rhinovirus and adenovirus (table 2). The RSV outbreak was significantly delayed during the COVID-19 period compared with the previous winters, with a plateau between January and March 2021, compared with peaks in November–December during the pre-COVID-19 periods (figure 1).

Table 2.

Results of the PCR performed in nasopharyngeal swabs for virus identification in the infants hospitalised in paediatric general wards for acute bronchiolitis between 2017 and 2021

| Pre-COVID-19 | Post-COVID-19 | P value* | ||||

| 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2017–2020 aggregated data |

2020–2021 | ||

| Infants, n | 479 | 451 | 417 | 1347 | 205 | |

| Nasal PCR†, n (%) | 245 (51.1) | 274 (60.7) | 281 (67.4) | 800 (59.4) | 167 (74.2) | <0.01 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 193 (78) | 202 (73) | 211 (75) | 606 (75) | 120 (71) | 0.3 |

| Rhinovirus | 41 (17) | 65 (24) | 63 (22) | 169 (12) | 44 (21) | 0.1 |

| Adenovirus | 17 (7) | 10 (4) | 14 (5) | 16 (11) | 12 (7) | 0.3 |

| Metapneumovirus | 17 (7) | 10 (4) | 10 (4) | 37 (2.7) | 19 (11) | 0.001 |

| Influenzae A | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.4 |

| Influenzae B | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.4 |

| Parainfluenzae 3 | 9 (4) | 6 (2) | 10 (4) | 27 (2) | 16 (10) | <0.01 |

| Bocavirus | 6 (2) | 11 (4) | 7 (2) | 24 (1.7) | 14 (8) | 0.001 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.02 |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 10 (0.7) | 9 (5) | <0.01 |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.2) | 7 (4) | <0.01 |

| No PCR, n (%) | 234 (48.8) | 177 (39) | 136 (32) | 547 (40) | 38 (18) | <0.01 |

*P value for the comparison between pre-COVID-19 aggregated data and COVID-19 data using χ2 test.

†Virus identifications by PCR in nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates were performed by means of Allplex Respiratory Panel Assays (Seegene) and/or Simplexa Flu A/B & RSV Direct Gen II Kit (Diasorin Molecular).

The proportion of the following viruses was significantly higher during the COVID-19 period than during the pre-COVID period: metapneumovirus (p=0.001), parainfluenzae 3 (p<0.01), bocavirus (p=0.001), coronavirus OC43 (p<0.01) and NL63 (p<0.01) (table 2). No influenza (A and B) was found during the COVID-19 period. Only three infants with bronchiolitis had a PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swabs during the COVID-19 period, but all three were also positive for RSV.

Discussion

This study highlights the dramatic reduction in the number of infants who required a hospitalisation for acute bronchiolitis during the COVID-19 outbreak compared with the three previous years. The outbreak of acute bronchiolitis was not only smaller but also delayed by several weeks. The clinical characteristics of the infants hospitalised for acute bronchiolitis as well as the hospitalisation courses were substantially similar during pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods. While the proportions of RSV and rhinovirus were similar between both periods, those of metapneumovirus, parainfluenzae 3, bocavirus, coronavirus NL63 and coronavirus OC43 increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, during the COVID-19 period, no influenza was found and the only three infants with a PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 were also positive for RSV, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 alone does not cause bronchiolitis.

This winter, we observed a strong decrease in the number of hospitalisations for acute bronchiolitis. This observation is consistent with data first from the Southern Hemisphere, Australia and South America11 12 and, more recently, from Europe and North America.9 13–16 Several studies reported reductions in the rate of admission to paediatric emergency departments for acute bronchiolitis during the COVID-19 outbreak.9 14 Results similar to ours were reported in Belgium with a dramatic decrease in bronchiolitis hospitalisations and very limited RSV positive as compared with the last 3 years.16 Two recent studies also suggest that social distancing and other lockdown strategies are effective in slowing down the spreading of respiratory diseases and decreasing the need for hospitalisation among children.13 15 Indeed, after reaching France in January 2020, a major progression of COVID-19 led to public health prevention interventions. The first national lockdown officially started on 17 March 2020 and ended on 10 May 2020. Masks had to be worn by persons 11 years of age and older in enclosed public places as of 20 July 2020. As shown in this study, the number of hospitalisations for acute bronchiolitis has therefore drastically decreased, even while schools and nurseries have remained open during winter. A recent publication shows the extent to which transmission of common paediatric infections can be altered when close contact with other children is eliminated.17 However, in our study, infants hospitalised for acute bronchiolitis had a mean age of 3.5 months, so a majority of these infants were not yet in collective nurseries, but were at home with their mothers (who were on maternity leave). Moreover, since September 2020, professionals in nurseries are required to wear a mask in the presence of children. It can therefore be suggested that the RSV transmission to these young children can also occur through their parents or older siblings. Intriguingly, we observed a lower proportion of infants with comorbidities hospitalised during the COVID-19 period. This could be due to the fact that parents have protected these at-risk children much more for fear that they would develop severe infections during the pandemic period.

The outbreak of acute bronchiolitis was not only lower but was also delayed by several weeks. Besides, RSV emerged in January, after the Christmas break. One explanation might be that families got together during this celebration break, and social distancing measures might have been followed less strictly. Interestingly, we observed that while the proportions of RSV and rhinovirus were similar to that of previous years during the COVID-19 period, those of parainfluenzae 3, bocavirus, coronavirus NL63 and coronavirus OC43 were higher. Our results on the prevalence of the various respiratory viruses during the pre-COVID-19 period are in agreement with the literature.18 Moreover, during the COVID-19 period, no influenza was found, suggestive that this virus is sensitive to the hygiene measures adopted during the pandemic. A recent epidemiological study on common communicable diseases in the general population in France during the COVID-19 pandemic also showed that patients who presented with ALRI symptoms and underwent a PCR test were most likely infected by influenza in 2019, but by SARS-CoV-2 or metapneumovirus in 2020.19 Moreover, in contradiction to assumptions made at the pandemic onset, our data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 alone does not cause bronchiolitis, as the only three infants SARS-CoV-2 positive were also positive for RSV. It will be important to confirm these results in the future, especially if SARS-CoV-2 remains endemic in the years to come.

The high impact of bronchiolitis in terms of cost of hospitalisation is not insignificant. In Italy, a recent study showed that the main cost item is related to young infants, in particular, those below 3 months of age, and RSV continues to be the main causative agent of severe bronchiolitis.20 The authors highlight that new vaccination strategies, such as the extension of immunoprophylaxis to infants is essential. Therefore, it would be useful, after the COVID-19 pandemic, for adults to continue to wear masks and wash their hands regularly to mitigate the risk of transmission of respiratory infection to young children. Acute severe RSV bronchiolitis in early childhood is associated with long-term morbidities including recurrent wheezing, asthma and lower lung function in later life.21 Therefore, the decrease in the number of severe bronchiolitis cases due to RSV or other viruses might not only have financial consequences but also impact the long-term respiratory outcome of children.

We are aware of some limitations of our study. The decrease in the number of hospitalisations may have been partly the consequence of a decrease in the overall number of emergency room visits since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is likely that, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, children with the most severe respiratory distress were still seen in the emergency room. In the UK, a significant reduction of non-urgent healthcare demands were observed during the pandemic and were associated with an increase in severe or urgent cases.22

In conclusion, our work provides an overview of the infants’ hospitalisations for acute bronchiolitis during the COVID-19 period in the winter of 2020–2021. This dramatic reduction in infants’ hospitalisations constitutes a great opportunity to change our habits for future autumn and winter seasons by advising people, especially adults, to wear masks and increase social distancing and hygiene measures in case of upper and lower respiratory tract infections. This may drastically change the worldwide burden of bronchiolitis and hospitalisations caused by RSV in the future, as well have important implications for patient outcomes and prevalence of asthma in children.23 The scientific community should nevertheless keep close surveillance of RSV epidemics since, as underlined by Di Mattia et al, the increase of an immunologically naïve population with infants born from mothers who have not reinforced their immunity to RSV could lead to greater epidemics in the next winters.24

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the medical and nursing staff of the paediatric pulmonology, general paediatric and paediatric emergency departments at Trousseau Hospital, Assistance Publique—Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Sorbonne Université, Paris, France.

Footnotes

Contributors: LB and HC conceptualised and designed the study, collected the data, drafted the initial manuscript and reviewed and revised the manuscript. RG designed the data collection, collected data, carried out the statistical analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript. A-SR, SR, AS, MP, ML and RC participated in the study conceptualisation and data collection. They also reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. HC accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the French Society for Respiratory Medicine (Société de Pneumologie de Langue Française, #CEPRO_2020-080). In accordance with French laws for observational studies, the requirement for written informed consent was waived (study BronChioVID N°20201119185601).

References

- 1.Florin TA, Plint AC, Zorc JJ. Viral bronchiolitis. Lancet 2017;389:211–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30951-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1545–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright M, Piedimonte G. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention and therapy: past, present, and future. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011;46:324–47. 10.1002/ppul.21377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bont L, Checchia PA, Fauroux B, et al. Defining the epidemiology and burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among infants and children in Western countries. Infect Dis Ther 2016;5:271–98. 10.1007/s40121-016-0123-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obando-Pacheco P, Justicia-Grande AJ, Rivero-Calle I, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality: a global overview. J Infect Dis 2018;217:1356–64. 10.1093/infdis/jiy056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair H, Simões EA, Rudan I, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2013;381:1380–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61901-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Che D, Nicolau J, Bergounioux J, et al. [Bronchiolitis among infants under 1 year of age in France: epidemiology and factors associated with mortality]. Arch Pediatr 2012;19:700–6. 10.1016/j.arcped.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vásquez-Hoyos P, Diaz-Rubio F, Monteverde-Fernandez N, et al. Reduced PICU respiratory admissions during COVID-19. Arch Dis Child 2020. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320469. [Epub ahead of print: 07 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guedj R, Lorrot M, Lecarpentier T, et al. Infant bronchiolitis dramatically reduced during the second French COVID-19 outbreak. Acta Paediatr 2021;110:1297–9. 10.1111/apa.15780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prise en charge Du 1er épisode de bronchiolite aiguë CheZ Le nourrisson de moins de 12 mois. Recommandations pour La pratique clinique. Avalaible at https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-11/hascnpp_bronchiolite_texte_recommandations_2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britton PN, Hu N, Saravanos G, et al. COVID-19 public health measures and respiratory syncytial virus. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e42–3. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nascimento MS, Baggio DM, Fascina LP, et al. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on the seasonality of pediatric respiratory diseases. PLoS One 2020;15:e0243694. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angoulvant F, Ouldali N, Yang DD, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: impact caused by school closure and national Lockdown on pediatric visits and admissions for viral and nonviral Infections-a time series analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72:319–22. 10.1093/cid/ciaa710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curatola A, Lazzareschi I, Bersani G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak in acute bronchiolitis: lesson from a tertiary Italian emergency department. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021;56:2484–8. 10.1002/ppul.25442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatoun J, Correa ET, Donahue SMA, et al. Social distancing for COVID-19 and diagnoses of other infectious diseases in children. Pediatrics 2020;146:e2020006460. 10.1542/peds.2020-006460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Brusselen D, De Troeyer K, Ter Haar E, et al. Bronchiolitis in COVID-19 times: a nearly absent disease? Eur J Pediatr 2021;180:1969–73. 10.1007/s00431-021-03968-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakamoto H, Ishikane M, Ueda P. Seasonal influenza activity during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Japan. JAMA 2020;323:1969–71. 10.1001/jama.2020.6173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenmoe S, Kengne-Nde C, Ebogo-Belobo JT, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of common respiratory viruses in children < 2 years with bronchiolitis in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic era. PLoS One 2020;15:e0242302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0242302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Launay T, Souty C, Vilcu A-M, et al. Common communicable diseases in the general population in France during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2021;16:e0258391. 10.1371/journal.pone.0258391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozzola E, Ciarlitto C, Guolo S, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy: the acute hospitalization cost. Front Pediatr 2020;8:594898. 10.3389/fped.2020.594898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitcharoensakkul M, Bacharier LB, Schweiger TL, et al. Lung function trajectories and bronchial hyperresponsiveness during childhood following severe RSV bronchiolitis in infancy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2021;32:457–64. 10.1111/pai.13399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valitutti F, Zenzeri L, Mauro A, et al. Effect of population Lockdown on pediatric emergency room demands in the era of COVID-19. Front Pediatr 2020;8:521. 10.3389/fped.2020.00521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi T, McAllister DA, O'Brien KL, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet 2017;390:946–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30938-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Mattia G, Nenna R, Mancino E, et al. During the COVID-19 pandemic where has respiratory syncytial virus gone? Pediatr Pulmonol 2021;56:3106–9. 10.1002/ppul.25582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.