BACKGROUND:

Every year, U.S. laundry providers reprocess over 4 billion pounds of healthcare textiles (HCTs), including surgical scrubs, uniforms, bed sheets, blankets, patient gowns, towels, and washcloths [1]. When laundered according to guidelines provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and standards set forth by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI), in facilities constructed according to the Facility Guidelines Institute standards at the time of construction [2, 3], contaminated HCTs can be rendered hygienically clean and safe for use in general patient care [4]. Contamination of HCTs after laundering has been linked to healthcare-associated infections, including outbreaks of mucormycosis, a disease caused by mucormycetes found throughout the environment and primarily affecting immunocompromised persons [5–8]. HCT-associated mucormycosis infections cause devastating patient illness, have high mortality rates, and can result in substantial financial and reputational damage to institutions [6].

Acute care hospitals commonly outsource laundry to offsite contracted providers [1], which may decrease oversight and increase opportunities for environmental contamination during laundered HCT handling, transportation, and delivery. Once laundered HCTs arrive at the healthcare facility, contamination may occur if HCTs are handled improperly during storage, staging, or distribution to the point of use. Hospital governing boards are responsible for ensuring the quality of contracted services and might not be aware of the degree to which suboptimal laundry management practices may threaten patient safety [9].

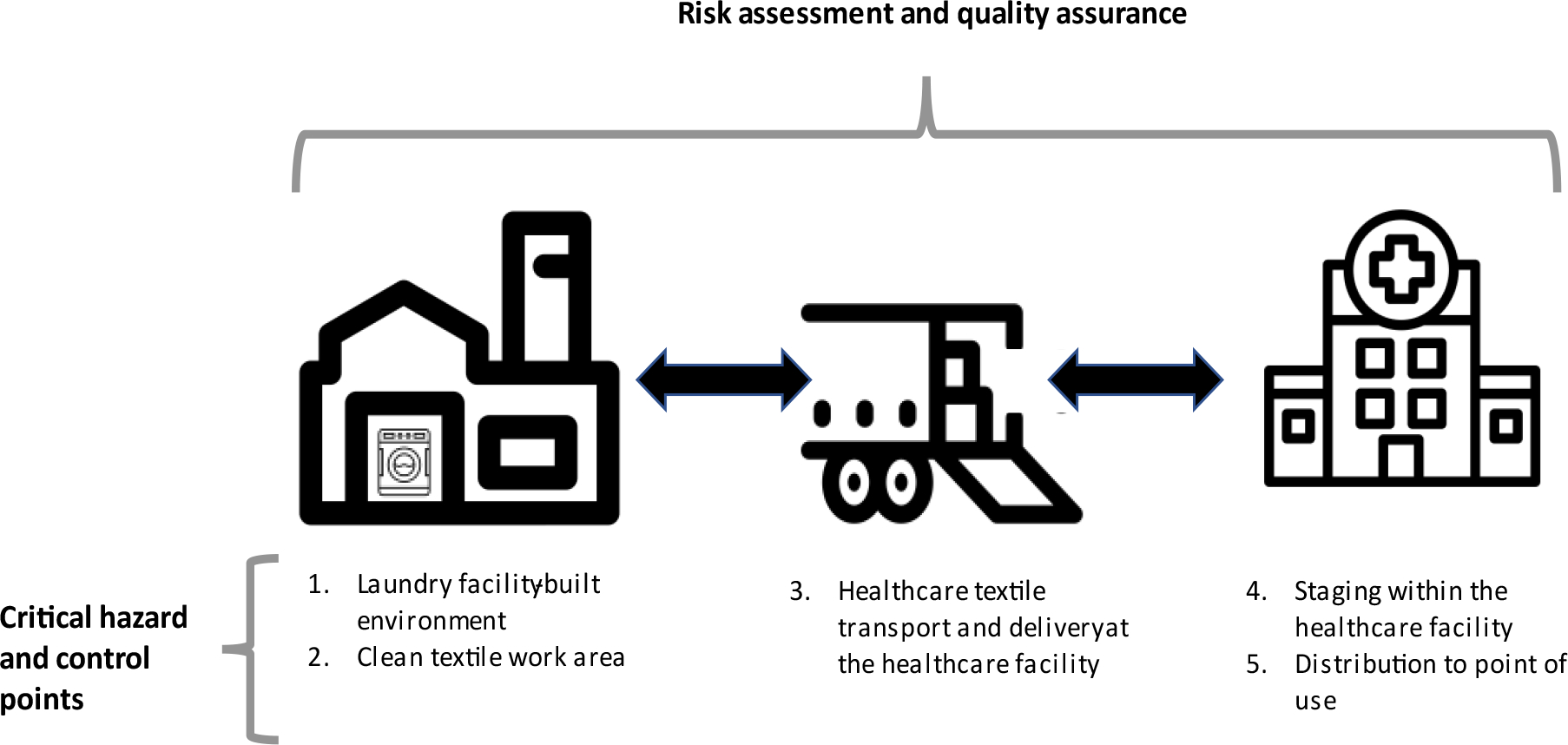

Infection preventionists play a central role in guiding HCT management practices, including the recognition of lapses at laundry or healthcare facilities and verification of remediation. Industries outside of healthcare often use a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) framework to systematically identify points in distribution systems where interventions may prevent product contamination [10]. A critical control point is a process step during which hazards (agents likely to cause illness if not controlled) can be prevented, eliminated, or reduced to acceptable levels [10]. Applying an HACCP framework (Figure 1), we describe the essential components of risk assessment and quality assurance and highlight underrecognized hazards, critical control points, and corresponding actions that infection preventionists can take to prevent the contamination of laundered HCTs, with the ultimate goal of preventing HCT-associated infections among patients. We compiled this report based on a review of existing guidelines, standards, published literature, and previous CDC experience investigating outbreaks of HCT-associated infections. This report contains accompanying checklists that infection preventionists may use to assess laundry and healthcare facilities for potential laundered HCT contamination hazards (Supplemental Materials).

Figure 1.

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point framework for keeping clean healthcare linens clean.

Footnote: Icons for this diagram were obtained from the Noun Project (https://thenounproject.com/). The icons were created by Vectorify (laundry facility), Circlonteach (washing machine) Andrejs Kirma (truck), and Fran Couto (healthcare facility).

Risk assessment and quality assurance

Hospital governing boards should be aware that accreditation or certification of laundry facilities by external agencies does not supplant infection preventionist expertise and in-person assessment. Two U.S. organizations, the Healthcare Laundry Accreditation Council and the TRSA, provide accreditation or certification of healthcare laundry facilities and offer valuable assurance that laundry standards are met. However, they are not considered deeming agencies by the CMS. In one study, neither laundry accreditation nor certification was associated with reductions in the number of fungal pathogens detected on reprocessed HCTs [5]. The governing board should rely on its facility infection preventionists to assess the risk to specific patient populations that will be exposed to items processed by the laundry facility. This risk assessment should be accompanied by an assessment of the facility’s ability to minimize opportunities for laundered healthcare textiles to become contaminated. Examples of high-risk inpatient populations may include burn, neonatal, cancer, and solid organ or stem cell transplant patients, those with disease processes such as uncontrolled diabetes, and those taking immunosuppressive medications [11].

Infection preventionists should lead the establishment of facility-specific quality benchmarks and other strategies to prevent HCT contamination and should consider seeking multidisciplinary input from healthcare environmental services, building managers, clinical staff, and laundry facility leadership. These benchmarks should be incorporated into contracts between the laundry and healthcare facility. Contracts should outline the expectation that infection preventionists will conduct regular, unscheduled, onsite observations of the laundry facility; such visits should occur at least once per year, or more frequently if issues are identified. The contract should also specify that the laundry facility will notify infection preventionists about planned construction projects so that infection preventionists can perform an Infection Control Risk Assessment (ICRA) to proactively protect patients for the duration of the project.

Previous HCT-associated mucormycosis cases highlight the importance of ensuring that laundry personnel have appropriate experience and expertise in HCT management [6]. The Association for Linen Management provides laundry and linen directors, managers, and technicians with education and role-specific certifications in specific domains, including infection prevention and control [12]. The healthcare facility should verify the credentials of laundry providers and ensure that laundry facility supervisory personnel have completed training related to HCT management.

Hazard and Action at Control Point 1. Laundry facility built environment

Infection preventionists should evaluate the built environment of the laundry facility, with particular attention to the facility’s heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system. Several HCT-associated mucormycosis outbreaks involved laundry facilities that did not meet recommended HVAC standards [5–7]. The healthcare facility should obtain documentation that the laundry facility’s ventilation system has been assessed by an HVAC professional and meets standards for healthcare laundry facilities set forth by the Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) and the ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE standard at the time of facility construction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ventilation standards for healthcare 20012

| Area | Pressure relationship to adjacent areas | Minimum outdoor ach | Minimum total ach | All room air exhausted directly to outdoors | Number of filter beds | Filter bed no.1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soiled linen sorting | In (Negative) | NR | 10 | Yes | 1 | 30 |

| Clean workroom | Out (Positive) | 2 | NR | NR | 1 | 30 |

| Clean linen storage * | Out (Positive) | NR | 2 | NR | 1 | 30 |

Abbreviations: ach = air changes per hour; NR = not required

Refers to storage at the laundry facility and staging area at the hospital.

Each U.S. state has Administrative Code that sets forth construction guidance for commercial facilities, and this code may supersede other standards or guidelines.

When laundry is performed onsite, healthcare facilities are required by The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to meet ventilation standards. Off site laundries are not likely to be surveyed and the infection preventionist must determine risk to populations served if the laundry facility building does not meet hospital ventilation standards. For high-risk patient populations, laundry facilities that lack an HVAC system to control the indoor climate and maintain appropriate air filtration and pressure relationships may represent a critical hazard. The presence of open louvers, windows, or dock doors on the clean side may indicate a lack of climate controls and exposes reprocessed HCT to environmental contaminants. Other previously noted failures to meet healthcare facility laundry construction standards include incorrect placement of unfiltered air intake and exhaust valves, which has been associated with contaminated HCTs and healthcare-associated infections [5]. If infection preventionists find concerns with the facility’s-built environment, then the healthcare facility should identify high-risk patients and proactively develop alternative means of providing them with safe HCTs until the laundry facility is able to meet construction and ventilation standards. If alternate sources for laundry are unavailable, the laundry facility might provide high risk patient populations with specially processed bed and bath packs that are monitored to ensure dryness and shrink-wrapped immediately after processing to protect them from environmental exposure.

Hazard and Action at Control Point 2. Laundry facility clean textile work area

Previous investigations of HCT-associated mucormycosis outbreaks have identified a variety of lapses in the handling of reprocessed textiles at laundry facilities, including failure to appropriately clean and line the interior of laundry carts and failure to adequately cover reprocessed HCTs during transport. In one outbreak, cleaned laundry carts at the laundry facility were air dried uncovered outdoors [6]. In another outbreak, exchange carts taken to an offsite location for refilling were cleaned only when visibly soiled, rather than being cleaned between each refilling [8].

Infection preventionists should verify that the laundry facility has access to and uses Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered disinfectants in accordance with label instructions (i.e., at appropriate dilutions, for adequate amounts of time) [4]. Surfaces of work areas in the clean textile folding and packaging area should be cleaned and disinfected routinely (e.g., daily or whenever soiled). Carts used to transport soiled textiles may be cleaned and disinfected using a manual or automated process and should remain within the controlled environment of the facility [6]. Carts may have holes in the bottom to facilitate water drainage following washing; if so, laundry personnel should use an impervious barrier to protect laundered HCT from soiling during transport. Laundry personnel should minimize the handling of laundered HCT and should have easy access to hand hygiene supplies.

Hazard and Action at Control Point 3. Healthcare textile transport and delivery at the healthcare facility

Soiled and clean HCT may be transported on the same truck, but methods such as functional separation must be in place to preserve HCT cleanliness and protect HCTs from dust and soil during loading, transport, and unloading [2]. During previous HCT-associated outbreaks, CDC investigators have observed several hazards at the healthcare facility receiving dock, including the presence of vermin and bird droppings, failure to maintain separation of clean and soiled supplies, delays in moving clean linen from the dock to internal linen staging areas, and improperly placed or torn impervious barriers (unpublished data). Infection preventionists should regularly evaluate sanitary conditions on the HCT receiving dock and collaborate with appropriate department directors to facilitate processes that minimize the amount of time laundered HCTs remain on the dock, outside of controlled staging areas. Ideally, the transport of soiled materials and waste should occur separately (i.e., at a different time or location) from the receipt of laundered HCTs. The healthcare facility should also establish and enforce policies and procedures to inspect carts upon arrival and reject carts that are visibly soiled, contain visibly soiled HCTs, or that have breaks in impervious barriers [13].

Hazard and Action at Control Point 4. Staging within the healthcare facility

Previous outbreak reports have identified several concerns regarding staging areas for laundered HCTs within healthcare facilities, including improper air pressure relationships, uncontrolled access by personnel, storage on wooden shelving that cannot be disinfected, and evidence of water intrusion in ceiling tiles [8]. The bottom shelf of wire racks should be solid or lined with an impervious barrier; alternatively, items on the bottom shelf can be placed in impervious containers [4]. For healthcare facilities that use exchange cart distribution systems in which carts are regularly refilled, failure to rotate stock may result in increased time for HCT contamination, particularly if carts are not sanitized on a regular schedule. A “first in, first out” rotation of HCT should be implemented so that textiles that have been in stock longest are used first. HCT staging areas should receive regularly scheduled environmental cleaning and routine validation of positive air pressure relationships to adjacent hallways or receiving areas.

Hazard and Action at Control Point 5. Healthcare facility distribution to the point of use

The HCT distribution process must ensure that supplies remain protected while in stock on the unit. Infection preventionists should conduct routine audits of HCT storage during unit-based rounds. HCT should remain protected from the environment (i.e., covered) and access to HCT storage areas should be controlled or under direct observation by healthcare personnel. Within patient rooms, HCTs should be kept away from splash zone of sinks, changed regularly or whenever visibly soiled, and used only for their intended purposes. Unused and soiled HCT should be placed in hampers for transport to soiled storage areas [13, 14].

CONCLUSIONS

Infection preventionists may prevent life-threatening infections by recognizing hazards in the management of laundered HCTs and taking action to prevent contaminated HCTs from reaching patients. For this report, we described six underrecognized hazards and corresponding actions that infection preventionists can take to protect patients from exposure to contaminated HCTs. We also provided checklists developed using outbreak literature and onsite experience, to assess laundry and healthcare facility management of laundered HCTs. This report does not address hazards to patients or healthcare personnel related to used HCTs, nor does it address the HCT laundering process itself. Information on these topics is available from laundry management or infection prevention professional organizations [15]. As the population of patients living with immunosuppression continues to grow [16], so will the urgency of preventing HCT-associated infections. Infection preventionists are well-poised to address this emerging challenge.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Frankie Wolfe and Amy Wilson, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Arkansas Department of Health. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy (see e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2), 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sehulster LM. Healthcare Laundry and Textiles in the United States: Review and Commentary on Contemporary Infection Prevention Issues. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 2015; 36(9): 1073–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI). Processing Of Reusable Surgical Textiles For Use In Health Care Facilities. ANSI/AAMI ST65:2008 (R2018). Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers. ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170–2021. Ventilation of Health Care Facilities. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehulster L, Chinn RY. Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports 2003; 52(Rr-10): 1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundermann AJ, Clancy CJ, Pasculle AW, et al. How Clean Is the Linen at My Hospital? The Mucorales on Unclean Linen Discovery Study of Large United States Transplant and Cancer Centers. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018; 68(5): 850–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy J, Harris J, Gade L, et al. Mucormycosis outbreak associated with hospital linens. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33(5): 472–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng VCC, Chen JHK, Wong SCY, et al. Hospital Outbreak of Pulmonary and Cutaneous Zygomycosis due to Contaminated Linen Items From Substandard Laundry. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2016; 62(6): 714–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teal LJ, Schultz KM, Weber DJ, et al. Invasive Cutaneous Rhizopus Infections in an Immunocompromised Patient Population Associated with Hospital Laundry Carts. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37(10): 1251–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Code of Federal Regulations. 482.12 Condition of participation: Governing body. Accessed: October 19, 2021. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-G/part-482/subpart-B/section-482.12.

- 10.United States Food and Drug Administration. HACCP Principles & Application Guidelines, National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods, Adopted August 14, 1997, Silver Spring, MD: Accessed: December 8, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/food/hazard-analysis-critical-control-point-haccp/haccp-principles-application-guidelines [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2012; 54 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): S16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association for Linen Management. Education and Training. Access date: January 10, 2022. https://www.almnet.org/page/EducationTraining.

- 13.Hartnett KP, Jackson BR, Perkins KM, et al. A Guide to Investigating Suspected Outbreaks of Mucormycosis in Healthcare. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland) 2019; 5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Reduce Risk from Water. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/environment/water.html.

- 15.Association for Linen Management. Advancing excellence in the textile care industry through education, certification, and best practices. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://www.almnet.org/.

- 16.Harpaz R, Dahl RM, Dooling KL. Prevalence of Immunosuppression Among US Adults, 2013. JAMA 2016; 316(23): 2547–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.