Abstract

Objectives

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are key biological mediators of several physiological functions within the cell microenvironment. Platelets are the most abundant source of EVs in the blood. Similarly, platelet lysate (PL), the best platelet derivative and angiogenic performer for regenerative purposes, is enriched of EVs, but their role is still too poorly discovered to be suitably exploited. Here, we explored the contribution of the EVs in PL, by investigating the angiogenic features extrapolated from that possessed by PL.

Methods

We tested angiogenic ability and molecular cargo in 3D bioprinted models and by RNA sequencing analysis of PL‐derived EVs.

Results

A subset of small vesicles is highly represented in PL. The EVs do not retain aggregation ability, preserving a low redox state in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and increasing the angiogenic tubularly‐like structures in 3D endothelial bioprinted constructs. EVs resembled the miRNome profile of PL, mainly enriched with small RNAs and a high amount of miR‐126, the most abundant angiogenic miRNA in platelets. The transfer of miR‐126 by EVs in HUVEC after the in vitro inhibition of the endogenous form, restored angiogenesis, without involving VEGF as a downstream target in this system.

Conclusion

PL is a biological source of available EVs with angiogenic effects involving a miRNAs‐based cargo. These properties can be exploited for targeted molecular/biological manipulation of PL, by potentially developing a product exclusively manufactured of EVs.

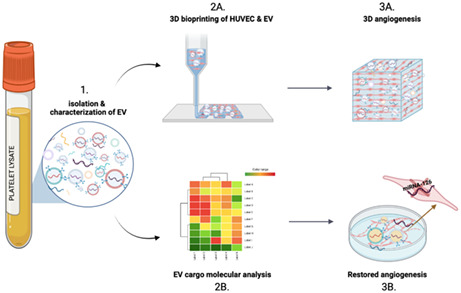

A high amount of small‐size extracellular vesicles (EVs) can be isolated from platelet lysate (PL)‐based preparations. When endothelial cells (HUVEC) are cultured in presence of EVs of platelet origin, they are able to significantly enhance the formation of angiogenic tubularly‐like structures in 3D endothelial bioprinted constructs (2A,B). PL‐derived EVs reflect a similar angiogenic microRNA profile (3A). Accordingly, EVs are mainly enriched with miR‐126, also known as angio‐miRNA, the most expressed miRNA by platelets in the blood. Hence, the silencing of the endogenous levels of miR‐126 in HUVEC and the retransferring of the same through PL‐derived EVs, restore angiogenesis in endothelial cells (3B). Images were created with the Biorender software.

1. INTRODUCTION

Beyond haemostasis and thrombosis, platelets have been also described as the main regulators of angiogenesis, a key process for tissue regeneration and repair outcome of vascular insults or wound healing and based on the activation of endothelial proliferation, sprouting and organization into functional tubules. 1 , 2 , 3 The emerging role of platelets to act as inflammatory/immune effectors and to enhance angiogenesis, stems from their intrinsic physiological role to interact with the endothelium during vascular damage, preserving the integrity and vessel homeostasis. 4

Platelets exhibit a unique secretory profile of multiple combined factors with a dual pro‐ and anti‐angiogenic role. Among them, we could list growth factors, cytokines, microRNAs, small soluble molecules and proteins, including those related to cytoskeleton, adhesion, inflammation, and extracellular matrix interaction. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 This balanced combination of mediators, is mainly contained in plasma membranes delimited nanoparticles, named extracellular vesicles (EVs). These later, now conceived as signalosomes and biological vectors of heterogeneous size and composition, are released upon platelets activation, interacting with the microenvironment. 9 , 10

Platelets represent the most abundant source of EVs of different dimensions and quantities in the systemic circulation 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 depending on multiple variables including age, physiological states and lifestyle habits. 15 , 16 EVs mirror the haemostatic properties of platelets, 17 by exerting both anti‐ and pro‐coagulant effects according to the subpopulation of EVs involved. 11 , 18 , 19 Hence, their circulating levels can act as predictive biomarkers of haemostatic and inflammatory disorders. 20 Patients with metabolic syndrome, myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, ischemia or inflammatory diseases exhibit higher levels of circulating EVs, because of activated platelets, 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 suggesting their relevance to mediate pathogenetic effects beyond their physiological role. On the other hand, platelet‐derived EVs have been also demonstrated to regulate angiogenesis when released at the site of endothelial sprouts 29 and secretion of VEGF, 30 or to transfer proliferative and survival biological information to the endothelium. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 Platelet‐derived EVs can modulate the vascular tone as shown in rabbit models, 30 or even attenuate blood pressure in preeclampsia women, by stimulating the inducible nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells, 34 consistently with a beneficial functional role on the vasculature.

Similarly to their parental cells, EVs would also act indirectly in a paracrine fashion on the intercellular network as cargos of cytokines and decoy proteins are locally released in the microenvironment. For instance, endothelial progenitor cell‐mediated angiogenesis 1 , 3 and tissue engraftment is enhanced by EVs of platelets origin through the activation of specific targets (MMP‐2, MMP‐9, PI3K, ERK) or after the transfer of specific soluble platelet receptors and activation of integrins on the endothelial surface. 30 , 35 , 36 , 37 The preconditioning of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with platelet‐derived EVs has demonstrated their effective capacity of boosting the biological potency and vascular effects of the stromal fraction. 38 Strong evidence of their ability to support angiogenesis has been also observed in myocardial infarction and cerebral ischemia after in vivo direct injection, when platelets, activated by thrombin, release EVs. 39 , 40 Moreover, the key contribution of platelet‐derived EVs in supporting the angiogenic profile of cancer invasion and metastasis parallel to clinical thrombotic complications has been strongly highlighted. 41 , 42 , 43

Based on these studies, evidence that platelets and platelet‐derived biological products can trigger angiogenic programs in endothelial cells has encouraged a better understanding of their potential therapeutic use for those regenerative‐based applications where the restoration or the enhancement of angiogenesis represents the clinical goal. Accordingly, parallel to the investigations regarding the key involvement of platelets in regulating angiogenesis, it has been demonstrated that platelet‐derived clinical preparations (i.e., platelet‐rich plasma and gels) are similarly able to boost and reflect the angiogenic properties of platelets. Particular attention has been dedicated to platelet lysate (PL), considered the gold preparation concentrate derived from platelets, and whose clinical efficacy is currently considered superior to other platelet‐derived formulations. 44 The employment of PL, alone or even in combination with different sources of stem cells, has shown to enhance blood perfusion in peripheral artery diseases, 45 to heal difficult wounds, to sustain stromal proliferation, epithelization, angiogenesis, and to prime cardiovascular differentiation. 1 , 2 , 3 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 The angiogenic capacity of PL is ascribable to the plethora of highly concentrated factors in this hemoderivative. When PL is manufactured, platelets are repeatedly lysed, therefore enriching the preparations with vesicles and granules, representing a primary source of angiogenic EVs. So far, the vast majority of studies have only explored the effects of vesicles of different origins (i.e., from MSCs, fibroblasts, lymphocytes) after treatment with PL, or EVs released by intact and activated platelets. 43 Only a couple of studies have described the presence of exosomes in platelet‐derived clinical formulations but as effectors of the osteogenic differentiation on MSCs or with neuroregenerative capacities. 38 , 50 Thus, the wide range of mechanisms by which PL‐derived EVs might regulate angiogenesis still needs to be fully addressed.

This study investigates from a biological and molecular standpoint the role of EVs in relation to PL formulations regarding the ability to mediate angiogenesis by endothelial cells.

2. METHODS

2.1. Isolation of EVs from PL‐based preparations

EVs were isolated from PL‐based preparations 2 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 51 by sequentially ultracentrifugation (500 rcf for 10 min; 2000 rcf for 10 min; 100,000 rcf for 1 h). EV pellet was then resuspended to reconstitute the initial PL volume and subsequently used at 5%, 10% or 20% in the medium for the experiments. For FACS analysis and uptake assay in human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC), 100 μl of EVs were stained for 10 min at 37°C with 5 μM 5(6)‐CFDA‐SE [5‐(and‐6)‐carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester] (CFSE; Invitrogen/Thermo Fischer Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Excess dye was removed using Exosome Spin Columns (Thermo Fischer Scientific) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

2.2. Nanotracking analysis of EVs in PL

Nanoparticles tracking analysis in terms of size distribution and concentration was performed on PL using a NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern Panalytical). Five 30‐s videos were recorded for each sample with a camera level set at 15 of 16 and a detection threshold set between 5 and 7. The EVs concentration and size distribution were subsequently analysed with NTA 3.2 software.

2.3. Western blot

EV were resuspended in a radioimmunoprecipitation buffer and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Proteins (10 μl solubilized in 2X Laemmli/20% of 2‐mercaptoethanol) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gel (Bio‐Rad). Subsequently, the membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) milk and the membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit Anti‐Annexin A1/ANXA1 antibody monoclonal antibody [EPR19342]‐BSA and Azide free (1:25,000; Abcam; Cat. N. ab222398), ALIX (1:1000; Biorbyt; Cat. N. orb235075), CD9 (1:500; Abcam; ab186429), calnexin (1:1000; Santa Cruz; Cat. N. sc‐46669), TSG101 (4A10) (1:500; Invitrogen; Cat. N. #MA1‐23296) After incubation, the membranes were incubated with secondary anti‐rabbit antibody (Cell Signalling; 1:10,000) and the immune complexes thus formed were detected by enhanced substrate chemiluminescence. Densitometric detection of the bands was performed by Chemidoc (Bio‐Rad).

2.4. Cell culture, transfection and treatment with antagomiR‐126

HUVECs were cultured between passages 3 and 6 in an EGM‐2 complete medium (Lonza). 3 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 Fluorescein‐conjugated antagomirs were used for quantification of antagomir or control incorporation and detected by flow cytometry. For antagomiR‐126 transfection, cells were plated at a density of 3.5 × 104/24 wells with EGM‐2 without gentamicin. A mix composed of 25 pmol LNA_126 (miRCURY LNA miRNA Inhibitor (5) ‐ 3′ Fam; Cat. N. 339121; Qiagen) or 25 pmol control (miRCURY LNA miRNA Inhibitor Control (5)‐No Modification Fam; Cat N. 339126; Qiagen) in Opti‐MEM Reduced‐Serum Media and lipofectamine (1 μl/100 μl Optimem; RNAiMAX; Invitrogen; Cat. N. 56531) was added to the HUVEC and incubated overnight. The next day, the medium was removed, and new EGM‐2 was added to the cells for up to 24 and 48 h of total transfection. To verify transfection, HUVEC were analysed by flow cytometry detecting FAM fluorescence. See Supporting Information Methods S1, for cytometric analysis, transmission electron microscopy, Matrigel assay and immunofluorescence on HUVEC in 3D‐bioprinting constructs, platelets aggregation, determination of soluble human prothrombin fragment 1 + 2 and quantification of peroxide hydrogen and molecular biology.

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad PRISM 5 software. Student's t‐test and one‐way analysis of variance (Bonferroni correction) were used to compare the difference between the control and groups. A p < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were presented as mean ± standard error unless specified. Additional information on statistics and confidence intervals have been reported in the corresponding sections above and in figure legends.

3. RESULTS

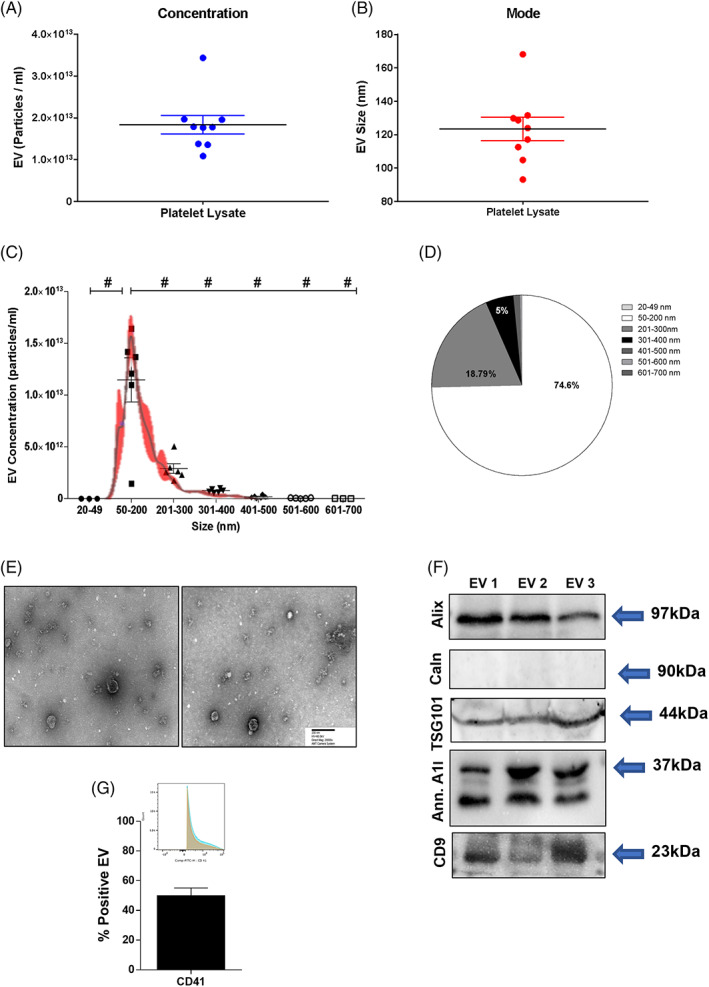

We investigated in detail the EV content and characteristics of human PL preparations. To assess the concentration and absolute size distribution, 56 we measured the EVs by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) in eight different batches of PL. Results showed that PL‐based preparations contain a very high concentration of EVs with a mean of 1.84 × 1013 particles/ml, with the EV size mode of 123.37 ± 7.02 nm (Figure 1A,B). Among all distinctive subclasses of EVs, the most representative group in terms of concentration was the 50–200 nm subset, corresponding to small microvesicles including exosomes 57 (Figure 1C,D, p < 0.001 vs. all subsets). Occasionally, EVs of <50 nm size were found, but not in all batches.

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in platelet lysate (PL). (A) Concentration measurement and (B) size mode from Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) of EVs derived by nine batches of PL. (C) NTA graph and (D) pie chart display the EVs size distributions. # p < 0.001. (E) Representative transmission electron microscopy images of EVs within PL‐based preparations. Scale bar (200 nm) and magnification (×20,000) are displayed. (F) Western blot analysis of ALIX, calnexin, TSG101, Annexin A1 and CD9 of three EV batches isolated by ultracentrifugation from PL. (G) Representative histogram of the flow cytometry displaying the relative percentage of EVs in the graph below for CD41, platelet marker. N = 3 lots of EVs were tested

Following international guidelines, 58 , 59 EVs were further characterized by evaluating their morphology and phenotype by transmission electronic microscopy (TEM), and Western blot for the recommended universal markers. TEM analysis confirmed that PL preparations contained EVs with heterogeneous but small dimensions, roundish morphology and electron‐dense features, suggesting a significant cargo function (Figure 1E). According to the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (‘MISEV’) guidelines, 58 TEM was qualitatively implemented by both Western blot showing the positive expression of the proteins ALIX, CD9, Annexin A1, TSG101 (cytosolic, membrane and marker of biogenesis of EV) in PL‐derived EVs 60 , 61 and negative expression for calnexin, therefore suggesting the absence of non‐EV structures in the preparation of EVs 62 (Figure 1F). The characterization of EVs was further verified by cytofluorimetry. The FACS analysis confirmed the expression of CD41, the main marker of platelet origin of EVs (49.92 ± 5.22%, also known as glycoprotein IIb possessing a critical role in modulating platelet aggregation 63 ), but also the negative expression for calnexin (Figure 1G).

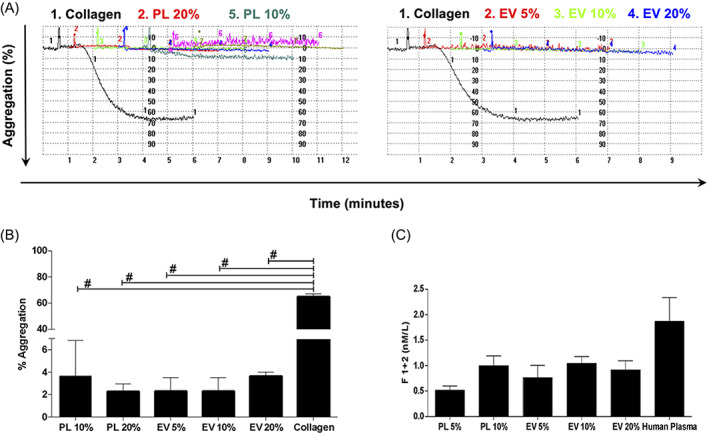

To discriminate the biological effects of EVs from the whole PL, we isolated the EVs according to methodological standardized guidelines by high‐speed ultracentrifugation. 64 , 65 Afterwards, we investigated whether EVs may convey haemostatic properties, such as aggregation and pro‐coagulant abilities, which are two key physiological properties exerted by platelets but also reported for EVs. 66 We stimulated platelets of healthy subjects with increasing percentages of EVs (5%, 10% and 20%). PL (10% and 20%) and collagen were used as biological and positive references, respectively. In addition, the quantification of the soluble fragment 1 + 2 of prothrombin (F1 + 2) was employed to test the coagulation property of EVs. Results showed that neither the increasing concentration of EVs nor PL were able to induce aggregation compared to collagen (Figure 2A,B). A similar amount of F1 + 2 among samples was detected (comparable to physiological soluble levels in the human plasma), with no statistically significant differences (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Hemostatic properties of EVs derived from PL. (A) Representative plots of the aggregometer displaying both PL and EVs at different percentage and (B) relative analysis showing no aggregation compared to collagen used as positive reference. # p < 0.001 (C) Immunoassay of the F1 + 2 assaying the coagulative ability of both PL and EVs compared with human plasma with no significant difference. EV, extracellular vesicle; PL, platelet lysate

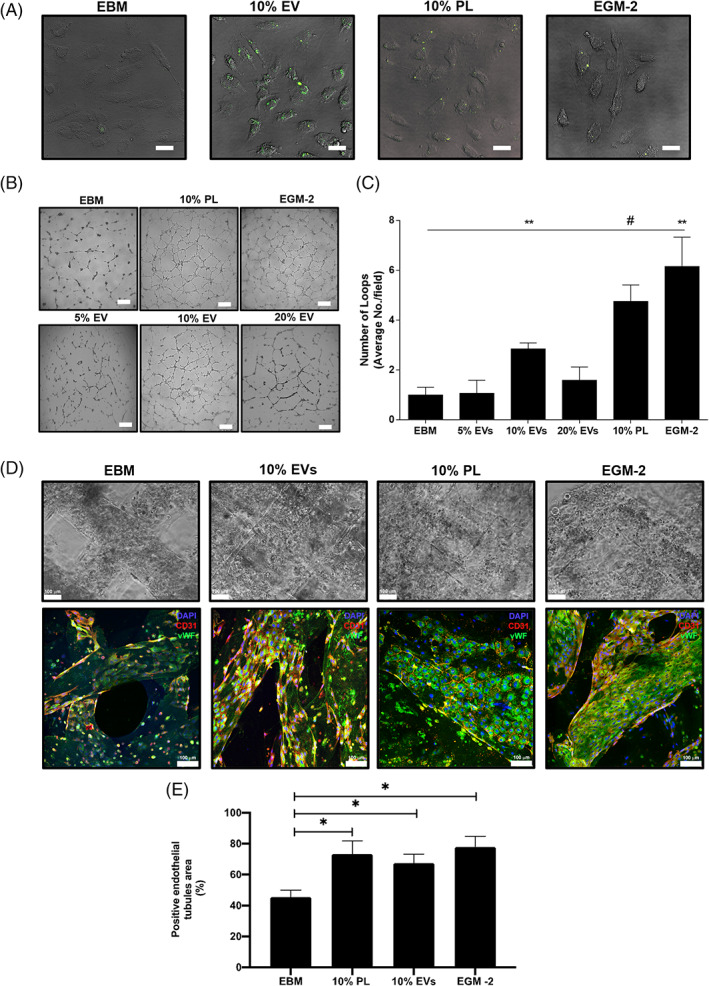

As one of the most significant bioactive properties of PL is the ability to induce angiogenesis, 2 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 we investigated the contribution of EVs to the angiogenesis stimuli mediated by PL. We isolated and labelled the EVs with the green fluorescent dye CFSE. Afterwards, HUVECs were stimulated for 24 h with the EV preparation (10% vol/vol, corresponding to the same PL volume in percentage routinely employed in cell culture 47 , 48 , 49 , 51 ). HUVECs were able to uptake EVs, as demonstrated by the presence of green fluorescent dots visible in the cytoplasm (Figure 3A). When HUVECs were subjected to the in vitro angiogenesis Matrigel assay at increasing concentrations of EVs (5%, 10%, 20%), we found that 10% EVs was the optimal percentage to significantly enhance the number of closed loops (Figure 3B,C) compared to the negative control (EBM, non‐supplemented endothelial basal media, p = 0.0038). Platelets lysate and EGM‐2 were used as positive angiogenic inducers. To corroborate this observation, we employed a 3D bioprinting‐based approach by encapsulating HUVECs in a gelatin/methacrylamide (GelMA) bioink, to evaluate their ability to induce the generation of vessel‐like structures in a more physiologically suitable 3D microenvironment in presence of 10% EVs (the best performer in the Matrigel assay). The confocal microscopy analysis showed that endothelial cells were able to colonize the bioprinted construct after treatment with both PL and PL‐derived EVs. Coherent with the observed spatial distribution, the proportion of the endothelial area (defined as CD31+/vWF+), corresponding to the organization of HUVECs in 3D tubular structures, was significantly higher with PL‐derived EV and PL treatments, compared to EBM control (Figure 3D,E; p < 0.05 vs. 10% EVs and 10% PL).

FIGURE 3.

Angiogenic effects of PL‐derived EVs in endothelial cells. (A) Merged images of optical and fluorescent microscopy showing HUVEC uptaking after 24 h the CSFE‐labelled isolated EVs in different experimental conditions (EBM and EGM‐2 negative and positive controls, respectively). White scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Representative images of capillary‐like structures from Matrigel assay and (C) quantitative analysis of number of formed loops with different percentage of EVs (5%, 10% and 20%). Magnification ×4. White scale bar = 200 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, # p < 0.001. One‐way ANOVA test was applied. A range of N = 3–12 experiments was performed. (D) Confocal microscopy images of 3D in vitro bioprinted HUVEC (bright and fluorescent images), displaying the formation of 3D‐tubules angiogenic structures. DAPI, CD31 and vWF stain blue, red and green, respectively. White scale bar = 100 μm. (E) Analysis of the immunofluorescence indicating the percentage of the positive 3D endothelial tubules area in the different conditions. *p < 0.05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; EV, extracellular vesicle; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; PL, platelet lysate

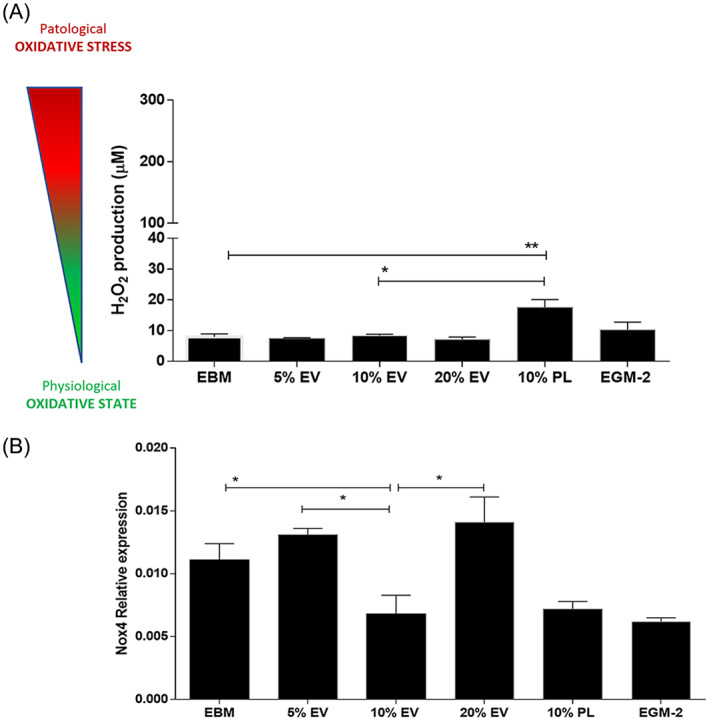

Several studies have demonstrated the modulation of the redox status in cells exposed to intact platelet‐derived EVs. 67 Thus, we investigated the levels of hydrogen peroxide in the conditioned media of HUVECs collected after 24 h of treatment with EVs. Results showed a lower release of hydrogen peroxide after treatment with 10% EVs compared to PL (p = 0.03; Figure 4A). We observed that the treatment with all percentages of EVs were able to maintain very low amounts of H2O2 in the media as both controls (EBM and EGM‐2). However, the 10% EVs reveals as the optimal anti‐oxidant stimulation respect to 10% PL (p < 0.05). This result was also coherent with the lowest expression level of the NADPH isoform Nox4 (the main and specific isoform responsible for the direct production of hydrogen peroxide by endothelial cells 52 , 53 , 68 , 69 , 70 ) after stimulation with 10% EVs among the three concentrations of EVs (p < 0.05; Figure 4B). The Nox4 mRNA levels in presence of 10% EVs were similarly downregulated as PL and EGM‐2 with respect to EBM (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of the oxidative states of endothelial cells after treatment with different percentage of PL‐derived EVs (5%, 10%, 20%). (A) Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) measurement of HUVEC‐derived condition media in all experimental conditions. The cartoon on the left of the graph shows the wide concentration range of H2O2 from physiological states (≤100 μM) to oxidative stress (≥300 μM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. One‐way ANOVA test was applied. A range of N = 3–16 experiments was performed. (B) Relative expression of the NADPH oxidase isoform 4 (NOX4) assayed by real‐time PCR and downregulated in HUVEC after treatment with 10% EVs respect to EBM and all other percentage of EVs (5% and 20%). The effect is also and comparable to that exerted by 10% PL and EGM‐2. *p < 0.05. One‐way ANOVA test was applied. A range of N = 3–11 experiments was performed. ANOVA, analysis of variance; EV, extracellular vesicle; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; PL, platelet lysate

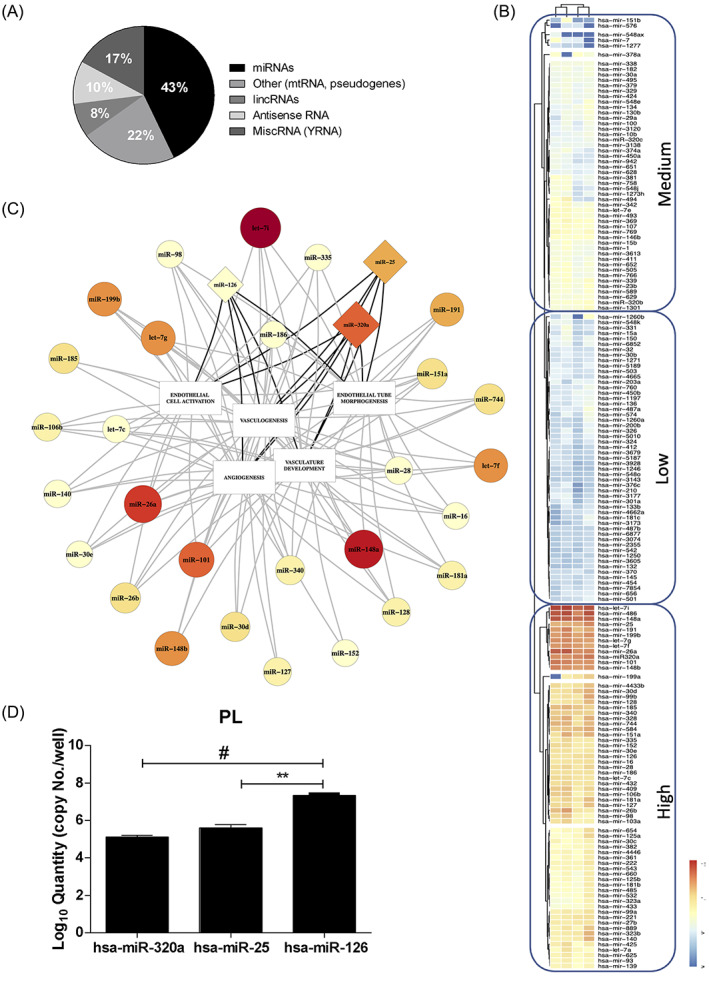

Some key functions of platelets, such as aggregation, activation and angiogenesis, are known to be mediated by miRNAs released by platelets in response to a wide range of stimuli, both physiological and pathological. 71 , 72 This ability can also be mediated by EVs, since they are known to transfer information to target cells through miRNAs, 73 and therefore to determine diverse biological effects in relation to the cargo within the vesicles. With these premises, we hypothesized the presence of miRNAs in PL‐based formulations and assessed this by analysing the miRNA profile of two different batches of PL for a total of four replicates. Results showed that the majority of the small RNA content in PL is represented by miRNAs (43%), followed by Y RNAs (17%), anti‐sense RNAs (10%), and lincRNAs (8%) (Figure 5A). A miscellaneous group is also represented (22%). After applying a cut‐off of >10 copies in all analysed batches of PL (average count among the four PL samples; Table 1), the identified miRNAs clustered into three macrogroups based on their expression levels (low, medium and high) when analysed by heatmap with hierarchical clustering (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

MiRNome characterization of platelet lysate by small RNA sequencing. (A) Small RNA percentage distribution in PL (a total of four replicates). (B) The heatmap has been obtained by including highly and consistently expressed miRNAs among the four analysed replicates with a cut‐off of >10 copies. The red‐yellow and the blue range colour indicate miRNAs with high and low average copy count, respectively. (C) Integration of the biological function with the expression of miRNAs in PL using a linkage group intertwined with five GO terms. Both the dimension of the box (circle/triangle) and the colour range reflect the expression levels as in the heatmap. (D) Quantitative PCR of hsa‐miR‐hsa‐320a, hsa‐miR‐25 and hsa‐miR‐126 have been employed to quantitatively validate the miRNome of PL. These three miRNAs are represented in the triangle box in C. PL, platelet lysate

TABLE 1.

List of all miRNAs contained in PL and obtained by small RNA sequencing Illumina

| ENSEMBL gene | miRBase ID | Avg count (four replicates) |

|---|---|---|

| ENSG00000199179 | hsa‐let‐7i | 35,420.48575 |

| ENSG00000283450.1 | hsa‐miR‐486 | 25,404.28176 |

| ENSG00000199085 | hsa‐miR‐148a | 21,102.40537 |

| ENSG00000207789.1 | hsa‐miR‐26a | 16,213.89862 |

| ENSG00000208037 | hsa‐miR320a | 9701.952607 |

| ENSG00000199065.3 | hsa‐miR‐101 | 9436.507077 |

| ENSG00000199122 | hsa‐miR‐148b | 7450.524382 |

| ENSG00000199150 | hsa‐let‐7g | 7267.479277 |

| ENSG00000207581 | hsa‐miR‐199b | 6969.810643 |

| ENSG00000208012 | hsa‐let‐7f | 6357.87107 |

| ENSG00000207605 | hsa‐miR‐191 | 5812.577567 |

| ENSG00000207547 | hsa‐miR‐25 | 5236.777868 |

| ENSG00000207948 | hsa‐miR‐328 | 3040.629801 |

| ENSG00000207714 | hsa‐miR‐584 | 2989.181797 |

| ENSG00000266297 | hsa‐miR‐744 | 2822.249642 |

| ENSG00000254324 | hsa‐miR‐151a | 2812.521101 |

| ENSG00000199121 | hsa‐miR‐26b | 2632.304808 |

| ENSG00000208023 | hsa‐miR‐185 | 2630.517199 |

| ENSG00000199153 | hsa‐miR‐30d | 2122.871247 |

| ENSG00000207550 | hsa‐miR‐99b | 2005.789909 |

| ENSG00000198995 | hsa‐miR‐340 | 1944.070041 |

| ENSG00000199107 | hsa‐miR‐409 | 1709.570737 |

| ENSG00000207595.1 | hsa‐miR‐181a | 1664.90131 |

| ENSG00000207654.4 | hsa‐miR‐128 | 1615.027686 |

| ENSG00000264297 | hsa‐miR‐4433b | 1526.263215 |

| ENSG00000208036 | hsa‐miR‐106b | 1475.271861 |

| ENSG00000207608 | hsa‐miR‐127 | 1461.537107 |

| ENSG00000208004 | hsa‐miR‐323b | 1379.391397 |

| ENSG00000207651 | hsa‐miR‐28 | 1345.078854 |

| ENSG00000208017 | hsa‐miR‐140 | 1321.751562 |

| ENSG00000271886 | hsa‐miR‐98 | 1222.679492 |

| ENSG00000199030 | hsa‐let‐7c | 1214.65648 |

| ENSG00000272458 | hsa‐miR‐432 | 1207.070114 |

| ENSG00000199161 | hsa‐miR‐126 | 1171.006656 |

| ENSG00000207721 | hsa‐miR‐186 | 1166.72288 |

| ENSG00000207947 | hsa‐miR‐152 | 1111.222163 |

| ENSG00000198987 | hsa‐miR‐16 | 1072.827202 |

| ENSG00000216099 | hsa‐miR‐889 | 1046.656644 |

| ENSG00000198974 | hsa‐miR‐30e | 1001.082556 |

| ENSG00000199043 | hsa‐miR‐335 | 982.9147665 |

| ENSG00000199024.1 | hsa‐miR‐103a | 974.3511292 |

| ENSG00000207752 | hsa‐miR‐199a | 919.4531345 |

| ENSG00000207870 | hsa‐miR‐221 | 895.0699612 |

| ENSG00000207864 | hsa‐miR‐27b | 821.4878295 |

| ENSG00000199032 | hsa‐miR‐425 | 772.8305776 |

| ENSG00000207638 | hsa‐miR‐99a | 740.1333674 |

| ENSG00000207934 | hsa‐miR‐654 | 621.1900075 |

| ENSG00000208008 | hsa‐miR‐125a | 597.3963088 |

| ENSG00000207725 | hsa‐miR‐222 | 538.5877917 |

| ENSG00000198975 | hsa‐let‐7a | 515.1025809 |

| ENSG00000207781 | hsa‐miR‐625 | 505.7290621 |

| ENSG00000265253 | hsa‐miR‐4446 | 451.4169995 |

| ENSG00000212040 | hsa‐miR‐543 | 409.0533201 |

| ENSG00000207757 | hsa‐miR‐93 | 403.8187224 |

| ENSG00000272036 | hsa‐miR‐139 | 399.12804 |

| ENSG00000207962 | hsa‐miR‐30c | 390.0986257 |

| ENSG00000199051 | hsa‐miR‐361 | 389.718269 |

| ENSG00000207970 | hsa‐miR‐660 | 340.2597669 |

| ENSG00000207758 | hsa‐miR‐532 | 318.869568 |

| ENSG00000208008.1 | hsa‐miR‐125b | 315.48886 |

| ENSG00000283170 | hsa‐miR‐382 | 314.8899174 |

| ENSG00000207737.1 | hsa‐miR‐181b | 314.5318373 |

| ENSG00000208027 | hsa‐miR‐485 | 289.3005292 |

| ENSG00000211580 | hsa‐miR‐769 | 283.8908085 |

| ENSG00000199025 | hsa‐miR‐369 | 273.869608 |

| ENSG00000199069 | hsa‐miR‐323a | 248.201048 |

| ENSG00000198972 | hsa‐let‐7e | 228.5801569 |

| ENSG00000207569 | hsa‐miR‐433 | 218.3957338 |

| ENSG00000207989 | hsa‐miR‐493 | 216.51903 |

| ENSG00000202569 | hsa‐miR‐146b | 214.64207 |

| ENSG00000198997 | hsa‐miR‐107 | 203.1544061 |

| ENSG00000194717 | hsa‐miR‐494 | 200.0772964 |

| ENSG00000199023 | hsa‐miR‐339 | 193.5326846 |

| ENSG00000199082 | hsa‐miR‐342 | 190.9249656 |

| ENSG00000221406.1 | hsa‐miR‐320b | 180.4782364 |

| ENSG00000221445 | hsa‐miR‐1301 | 166.0596828 |

| ENSG00000207633 | hsa‐miR‐505 | 149.7697394 |

| ENSG00000207563 | hsa‐miR‐23b | 149.2282785 |

| ENSG00000207973 | hsa‐miR‐589 | 143.1520471 |

| ENSG00000208013 | hsa‐miR‐652 | 133.0130015 |

| ENSG00000211578 | hsa‐miR‐766 | 129.7966503 |

| ENSG00000207965 | hsa‐miR‐629 | 125.3803452 |

| ENSG00000207779 | hsa‐miR‐15b | 125.0636251 |

| ENSG00000199047 | hsa‐miR‐378a | 121.8129584 |

| ENSG00000199020 | hsa‐miR‐381 | 116.4263774 |

| ENSG00000199017 | hsa‐miR‐1 | 109.082889 |

| ENSG00000199109 | hsa‐miR‐411 | 103.8221213 |

| ENSG00000264864 | hsa‐miR‐3613 | 97.42976184 |

| ENSG00000283604 | hsa‐miR‐338 | 94.82506088 |

| ENSG00000221214 | hsa‐miR‐548e | 92.96228251 |

| ENSG00000211582 | hsa‐miR‐758 | 91.70920684 |

| ENSG00000207990 | hsa‐miR‐182 | 90.79786569 |

| ENSG00000207993 | hsa‐miR‐134 | 88.31512911 |

| ENSG00000283871 | hsa‐miR‐130b | 83.90167079 |

| ENSG00000207827 | hsa‐miR‐30a | 81.14539472 |

| ENSG00000221760 | hsa‐miR‐548j | 77.90232379 |

| ENSG00000207743 | hsa‐miR‐495 | 76.96521629 |

| ENSG00000266192 | hsa‐miR‐1260b | 74.37795737 |

| ENSG00000207703 | hsa‐miR‐7 | 74.26392405 |

| ENSG00000199088 | hsa‐miR‐379 | 72.24067434 |

| ENSG00000207762.1 | hsa‐miR‐329 | 71.91954104 |

| ENSG00000284032 | hsa‐miR‐29a | 68.38616085 |

| ENSG00000274466 | hsa‐miR‐1273 h | 66.08291135 |

| ENSG00000284231 | hsa‐miR‐424 | 65.47781571 |

| ENSG00000199168 | hsa‐miR‐374a | 60.16913084 |

| ENSG00000207994 | hsa‐miR‐100 | 58.7905659 |

| ENSG00000207744 | hsa‐miR‐10b | 55.09601822 |

| ENSG00000221493.1 | hsa‐miR‐320c | 54.59647569 |

| ENSG00000264931 | hsa‐miR‐3138 | 53.8840101 |

| ENSG00000265154 | hsa‐miR‐151b | 53.70004073 |

| ENSG00000283152 | hsa‐miR‐3120 | 52.16606838 |

| ENSG00000207742 | hsa‐miR‐487a | 50.73182344 |

| ENSG00000207628 | hsa‐miR‐651 | 50.33440178 |

| ENSG00000199172 | hsa‐miR‐331 | 46.95913882 |

| ENSG00000207782 | hsa‐miR‐150 | 46.70553224 |

| ENSG00000207755 | hsa‐miR‐450a | 43.8147299 |

| ENSG00000283891 | hsa‐miR‐628 | 41.5096656 |

| ENSG00000284195 | hsa‐miR‐6852 | 40.13295067 |

| ENSG00000215930 | hsa‐miR‐942 | 39.06812916 |

| ENSG00000221745 | hsa‐miR‐1197 | 38.78852425 |

| ENSG00000207942 | hsa‐miR‐136 | 37.06113531 |

| ENSG00000207944 | hsa‐miR‐574 | 36.46764017 |

| ENSG00000207568 | hsa‐miR‐203a | 35.70390632 |

| ENSG00000216001 | hsa‐miR‐450b | 35.41952103 |

| ENSG00000211575 | hsa‐miR‐760 | 33.74964625 |

| ENSG00000221333 | hsa‐miR‐548 k | 32.79941145 |

| ENSG00000283785 | hsa‐miR‐15a | 31.76970682 |

| ENSG00000208005 | hsa‐miR‐503 | 29.37422859 |

| ENSG00000199090 | hsa‐miR‐326 | 29.13483177 |

| ENSG00000263456 | hsa‐miR‐5189 | 28.39871136 |

| ENSG00000221754 | hsa‐miR‐1260a | 25.23317752 |

| ENSG00000265820 | hsa‐miR‐3177 | 24.77186052 |

| ENSG00000263575 | hsa‐miR‐4665 | 24.67230585 |

| ENSG00000207582 | hsa‐miR‐30b | 23.72914734 |

| ENSG00000283929 | hsa‐miR‐5010 | 23.58517512 |

| ENSG00000221464 | hsa‐miR‐1271 | 23.45850327 |

| ENSG00000207959 | hsa‐miR‐656 | 23.24797065 |

| ENSG00000207698 | hsa‐miR‐32 | 22.99690997 |

| ENSG00000199053 | hsa‐miR‐324 | 22.04029532 |

| ENSG00000207613 | hsa‐miR‐181c | 21.68525112 |

| ENSG00000211538 | hsa‐miR‐501 | 21.6197488 |

| ENSG00000207996 | hsa‐miR‐301a | 19.45112604 |

| ENSG00000207730 | hsa‐miR‐200b | 18.50465325 |

| ENSG00000199005 | hsa‐miR‐370 | 17.84907533 |

| ENSG00000277255 | hsa‐miR‐7854 | 17.66723576 |

| ENSG00000276365 | hsa‐miR‐145 | 16.87146305 |

| ENSG00000199080 | hsa‐miR‐133b | 16.79696452 |

| ENSG00000283609 | hsa‐miR‐4662a | 16.70017447 |

| ENSG00000264607 | hsa‐miR‐3173 | 16.28783901 |

| ENSG00000211514 | hsa‐miR‐454 | 15.84741881 |

| ENSG00000283279 | hsa‐miR‐376c | 15.5124361 |

| ENSG00000263813 | hsa‐miR‐3679 | 15.27222439 |

| ENSG00000284035 | hsa‐miR‐5187 | 15.25222619 |

| ENSG00000199038 | hsa‐miR‐210 | 14.78583447 |

| ENSG00000199012 | hsa‐miR‐412 | 13.67471599 |

| ENSG00000264141 | hsa‐miR‐3928 | 13.43883139 |

| ENSG00000273932 | hsa‐miR‐6877 | 12.95400748 |

| ENSG00000263652 | hsa‐miR‐548ax | 12.60596835 |

| ENSG00000253008 | hsa‐miR‐2355 | 12.55831531 |

| ENSG00000207754 | hsa‐miR‐487b | 12.31700799 |

| ENSG00000207617 | hsa‐miR‐3074 | 12.1477769 |

| ENSG00000284154 | hsa‐miR‐3605 | 11.67230493 |

| ENSG00000221463 | hsa‐miR‐1277 | 11.51886948 |

| ENSG00000207988 | hsa‐miR‐576 | 11.43428817 |

| ENSG00000207784 | hsa‐miR‐542 | 10.87185064 |

| ENSG00000267200 | hsa‐miR‐132 | 10.58107814 |

| ENSG00000221025 | hsa‐miR‐1250 | 10.23723849 |

| ENSG00000221510 | hsa‐miR‐548o | 10.11483819 |

| ENSG00000283203 | hsa‐miR‐1246 | 10.02602246 |

| ENSG00000265565 | hsa‐miR‐3143 | 10.02172938 |

Note: Specifically, the selection here reported was made by including only those miRNAs with average counts >10 copies. The miRNome was performed on four replicates of PL batches. The first 39 miRNAs with a threshold of over 1000 reads are highlighted in red.

Abbreviation: PL, platelet lysate.

As a further selective step, we set a threshold for miRNAs with over 1000 reads, thus obtaining a shortlist of 39 miRNAs (Table 1), which underwent a bioinformatic top‐down analysis on the mirPath v.3 online tool (reverse search). The gene ontology (GO) terms selection was performed according to the function of interest observed for PL treatment on endothelial cells, which is angiogenesis. We interrogated the database by employing five GO, including the first two with the highest hierarchy for processes of capillary and vascular formation, in particular: VASCULOGENESIS (GO_0001570), ANGIOGENESIS (GO_0001525), ENDOTHELIAL CELL ACTIVATION (GO_0042118), VASCULAR DEVELOPMENT (GO_0001944) and ENDOTHELIAL TUBE MORPHOGENESIS (GO_0061154).

After intersecting each GO term with the top 39 miRNA shortlist, we extrapolated potential eligible candidates for the abovementioned roles. We found that the highest overlap was with the angiogenesis gene list as displayed in the function‐expression interaction network that we generated by software (Figure 5C). Afterwards, we compared the results and shortlisted the main group of 31 miRNAs and a further subset of 11 miRNAs correlating with two and all five GO categories, respectively, where three miRNAs (hsa‐miR‐320a, hsa‐miR‐25 and hsa‐miR‐126) were selected to quantitatively validate the seq data by real‐time PCR (Table 2). Notably, miR‐126 is a key regulator of angiogenesis and is known as the angio‐miRNA and one of the most abundant and specific miR to endothelial cells, human platelets and platelet‐derived vesicles. 74 Notably, the qPCR data accurately highlighted that miR‐126 is the most abundant miRNA in PL, compared to miR‐320a and miR‐25 (Figure 5D; p < 0.01 and p > 0.001).

TABLE 2.

List of the 31 miRNAs derived from the bioinformatic analysis to the five angiogenic GOs regarding the shortlist of 39 top expressed miRNAs in PL

| miRNAs | let‐7i | miR‐148a | miR‐26a | miR‐320a | miR‐101 | miR‐148b | let‐7g | miR‐199b | let‐7f | miR‐191 | miR‐25 | miR‐744 | miR‐151a | miR‐26b | miR‐185 | miR‐30d | miR‐340 | miR‐181a | miR‐128 | miR‐106b | miR‐127 | miR‐28 | miR‐140 | miR‐98 | let‐7c | miR‐126 | miR‐186 | miR‐152 | miR‐16 | miR‐30e | miR‐335 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOs | Angiogenesis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vasculogenesis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vascularature development | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Endothelial cell activation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Endothelial tube morphogenesis |

Note: In bold (black and red) are highlighted the 11 miRNAs included in all five GO categories (each one coloured according to the grayscale). In bold red the three miRNAs (miR‐320a, miR‐25 and miR‐126) employed for the validation of the small RNA seq of all platelet lysate batches. The miRNA belonging to the GO category is coloured differently as displayed. The white box suggests no association to the GO indicated.

Abbreviations: GO, gene ontology; PL, platelet lysate.

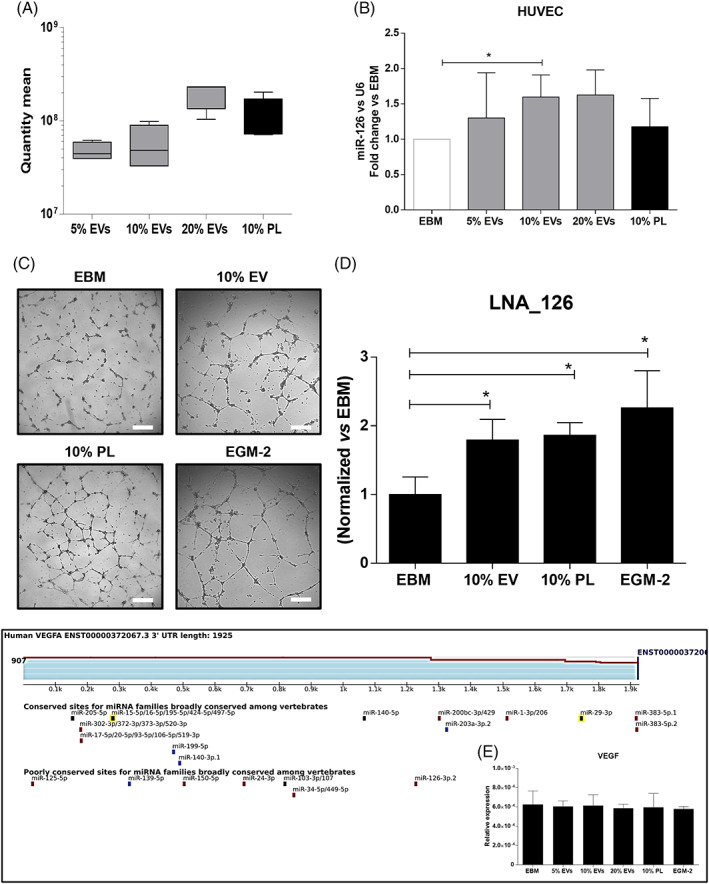

Next, we validated the role of miR‐126 in the biological effects of PL and EVs on HUVECs, by comparing the sole stimuli that were the media supplemented with 10% PL or 5%, 10% and 20% EVs (with volumes and dilutions adjusted to correspond to 10% PL). Although an increasing but not statistically significant trend of miR‐126 was observed among the percentages of EVs, real‐time PCR testing confirmed the equivalent content of miR‐126 in all media recipes (Figure 6A). The treatment with 10% EVs was the only able to significantly upregulate the levels of intracellular miR‐126 in endothelial cells compared to the negative control (Figure 6B; p < 0.05). We sought to verify whether EV‐miR‐126 could play a direct role in mediating angiogenesis ascribable to the transferring of this miRNA through EVs. To this aim, we transfected HUVECs with the antagomiR‐126 (LNA‐126) to rule out endogenous contribution. 75 Then, we stimulated the cells with 10% EVs or PL. Results showed that HUVECs were efficiently transfected by both the LNA‐126 and control, as shown by flow cytometry analysis (Figure S1a; 84.84 ± 0.4% positive cells with LNA‐126 and 78.5 ± 5.15% with control). Moreover, the copy number of miR‐126 in HUVEC, quantified by droplet digital PCR, was significantly decreased at the lowest levels 24 h after treatment with the LNA‐126, compared to both untreated and transfection controls (Figure S1b; p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively), while at 48 h the levels had increased again.

FIGURE 6.

Evaluation of hsa‐miR‐126 in endothelial cells after treatment with PL‐derived EVs. (A) Quantitative real‐time PCR, showing a similar amount of has‐miR‐126 among the percentages of EVs (5%, 10% and 20%) and 10% PL when employed as stimulus. One‐way ANOVA test was applied. A range of N = 3–16 experiments was performed. (B) Relative expression of has‐miR‐126 in HUVEC by real‐time PCR after treatment with 5%, 10% and 20% EVs or 10% PL. The fold change on the basal EBM is indicated. *p < 0.05. (C) Representative optical images and (D) quantification of the matrigel assay of HUVEC after antagomir‐126 (LNA_126) transfection and different treatments. Magnification ×4. White scale bar = 200 μm. *p < 0.05. (E) Targetscan analysis at the human 3′‐UTR of VEGF, highlighting that it is a target of miR‐126‐3p in the poorly conserved category and the validation by RTPCR showing no modulatory effect of this gene in our system. A range of N = 3–7 experiments was performed. ANOVA, analysis of variance; EV, extracellular vesicle; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; PL, platelet lysate

Finally, we tested the functional effects of blocking EV‐miR‐126 on angiogenesis and if HIF‐1α or VEGF, known to upregulate miR‐126 76 and to be abundant in PL, 2 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 respectively, might be downstream targets. In physiological conditions, the Matrigel assay showed that the number of loops significantly increased in presence of LNA‐126 but with treatment with 10% EV or 10%, PL compared to control EBM (Figure 6C,D, all p < 0.05 and Figure S1c,d for Matrigel with control), therefore, confirming the angiogenic effect contained in the EVs derived from PL and mediated at least partially by miR‐126. The analysis of the matches to human 3′‐UTRs of both HIF‐1α and VEGF through the TargetScan software revealed that only VEGF is a target of miR‐126‐3p in the poorly conserved category (Figure 6E). Nevertheless, the validation by real‐time PCR showed no modulatory effect in our system ascribable to VEGF (Figure 6E), suggesting different molecular targets controlled by miR‐126.

4. DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that PL formulations are enriched with EVs, which are biologically active and efficiently sustain angiogenesis in endothelial cells. Interestingly, the EV concentration in our PL is very high and mainly composed of a small EVs subset (50–200 nm), 58 suggesting that PL might be reinterpreted as an abundant biological source of this EVs subpopulation.

Intriguingly, in line with reports showing comparable in vitro and in vivo haemostatic properties of both platelet microparticles and PL‐derived EVs on platelets, 77 , 78 , 79 our EVs only partially retain this feature. Our PL‐derived EVs do not promote platelet aggregation, but they are able to preserve coagulation in a physiological manner, strengthening their versatile use as angiogenic/antiaggregant mean for cardiovascular applications (where platelet aggregation is a critical risk factor 80 ), as a topical product for bleeding during surgery, or as a substitute of platelet transfusion. Anti‐aggregant therapies are acknowledged to negatively impact coagulation, causing bleeding, 81 therefore, the possibility to investigate and distinguish these two interconnected haemostatic properties in platelet‐derived products (such as PL) is of paramount significance, in order to develop novel products with a unique haemostatic function compatible with the clinical use.

Our results demonstrated that EVs after being internalized by endothelial cells, positively enhances angiogenesis by fostering endothelial tubule‐like networks in a complex 3D microenvironment, similarly to PL. This phenomenon is in line with those describing the angiogenic effects of EVs derived from circulating intact platelets, 82 , 83 or from other non‐platelet cell types. 84 , 85 Although PL also contains a plethora of several soluble mediators with angiogenic function, 2 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 it is conceivable that EVs implement this property that PL normally possesses. Notably, 10% of EVs were revealed as the optimal condition in culture, showing a non‐canonical dose–response of EVs without additional effects at a higher percentage in line with the variable biological effects of EVs already verified. 86 The 10% EVs might represent a sort of ‘balanced’ amount. We have already experienced that the 10% PL itself is the optimal percentage for angiogenic assay also in presence of inhibition of specific soluble factors within the preparation. Below or above this threshold angiogenic effects are not optimal. 46 Nevertheless, some biological differences exist between PL and EVs: these latter preserve the physiological levels of hydrogen peroxide (<100 μM) 87 more efficiently than PL and other percentages of EVs in parallel to a comparable redox status (Nox4), therefore generating an anti‐oxidant microenvironment, known to foster beneficial angiogenic effects in endothelial cells 68 , 87 , 88 , 89 and to preserve vascular function, homeostasis and integrity of the vascular network beyond pathological scenarios. 90 This phenomenon also occurs in platelets: H2O2 enhances their activation 91 or aggregation upon specific agonists, 92 resulting in a loop of specific NADPH which acts as a sensor of the H2O2 axis in endothelial cells. 68 , 93 , 94 This result is consistent with the lower production of H2O2 found between EVs and PL. It is plausible that EVs contain the machinery for both oxidant and anti‐oxidant molecules, therefore acting in a double fashion according to metabolic needs and signals within the microenvironment. 95

To date, the molecular mechanism by which clinical preparations obtained from platelets enhance regenerative angiogenesis remains not fully explored. Both platelets, the main contributor of miRNAs released in the blood, and their microparticle counterparts, contain a wide range of overlapping miRNAs, 96 whose investigation so far has been restricted mainly to physiological functions related to aggregation and activation. 96 , 97 The miRNAs derived from EVs of platelet origin are both novel biomarkers in the context of anti‐platelet therapies and platelet function, 98 and biological mediators in the cellular microenvironment, 6 , 99 , 100 suggesting their extra‐platelet role beyond hemostatic properties.

We have demonstrated that half of the small RNA content of PL is composed of miRNAs. We found that angiogenic miRNAs (miR‐320, miR‐25 and miR‐126) are contained in the EV cargo as well as in PL. So far, proper screening of the miRNA profile has been performed only in PRP 101 and intact or hyperreactive platelets from healthy subjects, or in the presence of cardiovascular pathologies. Interestingly, when we profiled our PL, data have shown that the formulation reflects a similar repertoire of mature miRNAs found in human platelets and described in the literature, 71 , 72 including the abundant miRlet‐7 (a marker of platelet differentiation and maturation in megakaryocytopoiesis 102 ), or defined microRNA families (i.e., miR‐25 and miR‐103). 72 By intertwining the transcriptomic expression profile with the vascular function, we have confirmed that in PL‐based preparations the miRNAs quantitatively more represented are also strictly interconnected to the angiogenic function. The EVs contained in PL mirror this picture and confirm that miR‐126 is the most significant miRNA in both preparations.

The angio‐miRNA miR‐126 is one of the most abundant miRNA expressed in platelets. 103 , 104 Sharing with miR‐320 (that we also found as highly represented) the unique expression also in endothelial cells, miR‐126 is able to downregulate adhesion molecules (e.g., VCAM‐1) upon the influence of specific cytokines (i.e., VEGF), therefore contributing to endothelial migration, proliferation, activation and vascular inflammation. 75 Exosomes enriched in miR‐126 are strictly correlated with protection from ischemic events 105 and atherosclerosis progression. 106 Changes in circulating levels of miR‐126 have been described in patients with acute ischemic stroke, 107 coronary artery disease or type 2 diabetes. 108 Moreover, vascular development and integrity are sustained by miR‐126 in zebrafish and mice, 109 , 110 whereas in vivo silencing of miR‐126 impaired angiogenesis 111 upon ischemic insult. Thus, miR‐126 appears as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for angiogenesis. Nonetheless, the transfer of miRNAs in the form of EVs under physiological and pathological conditions from platelets to endothelial cells (and vice versa), and the modality by which biological functions are sustained, are still under intensive investigation.

Our data confirm that miR‐126 of platelet origin plays a key role in the angiogenic homeostasis of endothelial cells. Accordingly, results highlight that HUVECs increase intracellular levels of miR‐126 upon stimulation with EVs of PL origin, by adding exogenous miR126 by EV transfer when the endogenous miR‐126 is silenced. Thus, our results demonstrate that a fraction of the angiogenic effect induced by the whole PL preparation is directly ascribable to the EV cargo, specifically to platelet‐derived miR‐126.

This study has some limitations. Although we found that VEGF is a target of miR‐126, we could not observe any modulatory effect in our system, suggesting that alternative mechanisms are needed to be verified. Only a few of them have been already described. For instance, the DNA methyltransferase, playing a role in hypoxia tolerance, has been found as a target of miR‐126 contained in exosomes. 112 Further mechanisms can coexist, including the reduction of cell apoptosis, 105 the overactivation of autophagy through Beclin, 113 the novel delivery system by apoptotic bodies through CXCL12 114 or the inhibition of the negative regulators of the VEGF‐axis. 110 , 115 More importantly, the angiogenic properties of both EVs and PL cannot be explained uniquely by the miR‐126. The miRNome here described suggests the presence of additional miRNAs with similar functions. For instance, the exosomal derived‐miR25 has been found to promote angiogenesis, vascular permeabilization, metastatic niches in cancer and involvment in cardiovascular disorders. 116 , 117

To date, the individual contribution of EVs within PL has not been fully elucidated in terms of regenerative angiogenesis. Certainly, the methodology to manufacture PL severely impacts the quantity and the quality of EVs within the formulations and in particular that employed to concentrate, lyse or activate platelets 118 in the formulation. Accordingly, PL preparations with excessive heterogeneity of EV content might result in parallel different downstream signalling and pathways activated with a wide range of unpredictable biological effects, also depending on cells potentially targeted by clinical PL preparations.

In conclusion, PL‐based formulations are a source of both biologically available miRNAs and EVs defining the hallmark of platelet origin. The EVs reflect the ‘angiogenic physiology’ of PL, confirming that a cell‐free therapy approach may be a novel effective strategic tool in clinical applications.

Future investigations will be required to unveil the role of downstream targets of different miRNAs potentially preserved in EVs of platelet origin, and how additional processes not limited to angiogenesis are modulated, including immunomodulatory functions and paracrine effects.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Antonella Bordin performed the main experiments. Maila Chirivì, Marika Milan and Roberto Rizzi performed 3D constructs. Francesca Pagano performed qPCR of small RNA seq. Marco Iuliano and Eleonora Scaccia isolated the EVs. Orazio Fortunato and Giorgio Mangino performed NTA and cytofluorimetry. Xhulio Dhori developed the matrix for the angiogenic network of the small RNA seq. Elisabetta De Marinis performed the droplet digital PCR. Alessandra D'Amico and Fabio Pulcinelli performed all experiments on aggregation and oxidative states. Selenia Miglietta performed the TEM. Vittorio Picchio the cell transfection. Giacomo Frati and Isotta Chimenti reviewed and edited the manuscript. Elena De Falco conceived the study and wrote the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

FIGURE S1 Validation of cell transfection with antagomir‐126 (LNA_126) in endothelial cells. (A) Representative histogram of the cytometric analysis of HUVEC with LNA_126 (light blue line) and Control (orange line) in FITC channel. Autofluorescence is highlighted with the red line. (B) Absolute quantification of hsa‐miR‐126 by Droplet digital PCR, showing the efficient downregulation of the number of the copies in HUVEC after transfection with LNA_126 LNA or Control (Ctl_126) compared to untreated cells (WT) at 24 h and 48 h. (C) Representative optical images and (D) quantification of the matrigel assay of HUVEC after Control (Ctl_126) transfection and different treatments. Magnification 4X. White scale bar, 200 μm. *p < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Sapienza Department of Medical‐Surgical Sciences and Biotechnologies in Latina for the continuous support and effort. The authors also thank the FlowCore in Mannheim (Medical Faculty Mannheim, University of Heidelberg) whose Cytek was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Ministry of Science Baden‐Württemberg within the framework of the Excellence Strategy of the Federal and State Governments of Germany. This study was funded by the Sapienza University of Rome Prot. N. AR220172B836675B: “New insight into the hemoderivate GMP‐grade Platelet Lysate: extracellular vesicle content, size and composition” granted to Antonella Bordin. This project has also received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement No 813839.

Bordin A, Chirivì M, Pagano F, et al. Human platelet lysate‐derived extracellular vesicles enhance angiogenesis through miR‐126. Cell Prolif. 2022;55(11):e13312. doi: 10.1111/cpr.13312

Funding information European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie, Grant/Award Number: 813839; Sapienza Università di Roma, Grant/Award Number: AR220172B836675B

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Main data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article, and detailed data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. De Falco E, Porcelli D, Torella AR, et al. SDF‐1 involvement in endothelial phenotype and ischemia‐induced recruitment of bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104(12):3472‐3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Businaro R, Corsi M, Di Raimo T, et al. Multidisciplinary approaches to stimulate wound healing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1378(1):137‐142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Falco E, Carnevale R, Pagano F, et al. Role of NOX2 in mediating doxorubicin‐induced senescence in human endothelial progenitor cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016;159:37‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rondina MT, Garraud O. Emerging evidence for platelets as immune and inflammatory effector cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tamir A, Sorrentino S, Motahedeh S, et al. The macromolecular architecture of platelet‐derived microparticles. J Struct Biol. 2016;193(3):181‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boilard E, Nigrovic PA, Larabee K, et al. Platelets amplify inflammation in arthritis via collagen‐dependent microparticle production. Science. 2010;327(5965):580‐583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prokopi M, Pula G, Mayr U, et al. Proteomic analysis reveals presence of platelet microparticles in endothelial progenitor cell cultures. Blood. 2009;114(3):723‐732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mause SF, Ritzel E, Liehn EA, et al. Platelet microparticles enhance the vasoregenerative potential of angiogenic early outgrowth cells after vascular injury. Circulation. 2010;122(5):495‐506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dinkla S, van Cranenbroek B, van der Heijden WA, et al. Platelet microparticles inhibit IL‐17 production by regulatory T cells through P‐selectin. Blood. 2016;127(16):1976‐1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vasina EM, Cauwenberghs S, Staudt M, et al. Aging‐ and activation‐induced platelet microparticles suppress apoptosis in monocytic cells and differentially signal to proinflammatory mediator release. Am J Blood Res. 2013;3(2):107‐123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heijnen HF, Schiel AE, Fijnheer R, Geuze HJ, Sixma JJ. Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha‐granules. Blood. 1999;94(11):3791‐3799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Becker RC, Sexton T, Smyth SS. Translational implications of platelets as vascular first responders. Circ Res. 2018;122(3):506‐522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Edelstein LC. The role of platelet microvesicles in intercellular communication. Platelets. 2017;28(3):222‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berckmans RJ, Nieuwland R, Boing AN, Romijn FP, Hack CE, Sturk A. Cell‐derived microparticles circulate in healthy humans and support low grade thrombin generation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85(4):639‐646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van der Zee PM, Biro E, Ko Y, et al. P‐selectin‐ and CD63‐exposing platelet microparticles reflect platelet activation in peripheral arterial disease and myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 2006;52(4):657‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morel O, Jesel L, Hugel B, et al. Protective effects of vitamin C on endothelium damage and platelet activation during myocardial infarction in patients with sustained generation of circulating microparticles. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(1):171‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walsh TG, Metharom P, Berndt MC. The functional role of platelets in the regulation of angiogenesis. Platelets. 2015;26(3):199‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Assinger A, Koller F, Schmid W, et al. Specific binding of hypochlorite‐oxidized HDL to platelet CD36 triggers proinflammatory and procoagulant effects. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(1):153‐160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lhermusier T, Chap H, Payrastre B. Platelet membrane phospholipid asymmetry: from the characterization of a scramblase activity to the identification of an essential protein mutated in Scott syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(10):1883‐1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Italiano JE Jr, Mairuhu AT, Flaumenhaft R. Clinical relevance of microparticles from platelets and megakaryocytes. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17(6):578‐584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Amabile N, Rautou PE, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microparticles: key protagonists in cardiovascular disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36(8):907‐916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Namba M, Tanaka A, Shimada K, et al. Circulating platelet‐derived microparticles are associated with atherothrombotic events: a marker for vulnerable blood. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(1):255‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tan KT, Tayebjee MH, Lynd C, Blann AD, Lip GY. Platelet microparticles and soluble P selectin in peripheral artery disease: relationship to extent of disease and platelet activation markers. Ann Med. 2005;37(1):61‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duchez AC, Boudreau LH, Naika GS, et al. Platelet microparticles are internalized in neutrophils via the concerted activity of 12‐lipoxygenase and secreted phospholipase A2‐IIA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(27):E3564‐E3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hartopo AB, Puspitawati I, Gharini PP, Setianto BY. Platelet microparticle number is associated with the extent of myocardial damage in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12(3):529‐537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stepien E, Stankiewicz E, Zalewski J, Godlewski J, Zmudka K, Wybranska I. Number of microparticles generated during acute myocardial infarction and stable angina correlates with platelet activation. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(1):31‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perez‐Pujol S, Marker PH, Key NS. Platelet microparticles are heterogeneous and highly dependent on the activation mechanism: studies using a new digital flow cytometer. Cytometry A. 2007;71(1):38‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rhee JS, Black M, Schubert U, et al. The functional role of blood platelet components in angiogenesis. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92(2):394‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim HK, Song KS, Chung JH, Lee KR, Lee SN. Platelet microparticles induce angiogenesis in vitro. Br J Haematol. 2004;124(3):376‐384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun C, Feng SB, Cao ZW, et al. Up‐regulated expression of matrix metalloproteinases in endothelial cells mediates platelet microvesicle‐induced angiogenesis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41(6):2319‐2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ratajczak J, Wysoczynski M, Hayek F, Janowska‐Wieczorek A, Ratajczak MZ. Membrane‐derived microvesicles: important and underappreciated mediators of cell‐to‐cell communication. Leukemia. 2006;20(9):1487‐1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taraboletti G, D'Ascenzo S, Borsotti P, Giavazzi R, Pavan A, Dolo V. Shedding of the matrix metalloproteinases MMP‐2, MMP‐9, and MT1‐MMP as membrane vesicle‐associated components by endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(2):673‐680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. VanWijk MJ, Nieuwland R, Boer K, van der Post JA, VanBavel E, Sturk A. Microparticle subpopulations are increased in preeclampsia: possible involvement in vascular dysfunction? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(2):450‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Janowska‐Wieczorek A, Majka M, Kijowski J, et al. Platelet‐derived microparticles bind to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and enhance their engraftment. Blood. 2001;98(10):3143‐3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zaldivia MTK, McFadyen JD, Lim B, Wang X, Peter K. Platelet‐derived microvesicles in cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Merten M, Pakala R, Thiagarajan P, Benedict CR. Platelet microparticles promote platelet interaction with subendothelial matrix in a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa‐dependent mechanism. Circulation. 1999;99(19):2577‐2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Torreggiani E, Perut F, Roncuzzi L, Zini N, Baglio SR, Baldini N. Exosomes: novel effectors of human platelet lysate activity. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:137‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayon Y, Dashevsky O, Shai E, Varon D, Leker RR. Platelet lysates stimulate angiogenesis, neurogenesis and neuroprotection after stroke. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(2):323‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brill A, Dashevsky O, Rivo J, Gozal Y, Varon D. Platelet‐derived microparticles induce angiogenesis and stimulate post‐ischemic revascularization. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67(1):30‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Young A, Chapman O, Connor C, Poole C, Rose P, Kakkar AK. Thrombosis and cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(8):437‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Slomka A, Urban SK, Lukacs‐Kornek V, Zekanowska E, Kornek M. Large extracellular vesicles: have we found the holy grail of inflammation? Front Immunol. 2018;9:2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aatonen MT, Ohman T, Nyman TA, Laitinen S, Gronholm M, Siljander PR. Isolation and characterization of platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:24692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Klatte‐Schulz F, Schmidt T, Uckert M, et al. Comparative analysis of different platelet lysates and platelet rich preparations to stimulate tendon cell biology: an in vitro study. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(1):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tao SC, Guo SC, Zhang CQ. Platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles: an emerging therapeutic approach. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13(7):828‐834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Businaro R, Scaccia E, Bordin A, et al. Platelet lysate‐derived neuropeptide y influences migration and angiogenesis of human adipose tissue‐derived stromal cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carducci A, Scafetta G, Siciliano C, et al. GMP‐grade platelet lysate enhances proliferation and migration of tenon fibroblasts. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2016;8:84‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Siciliano C, Chimenti I, Bordin A, et al. The potential of GMP‐compliant platelet lysate to induce a permissive state for cardiovascular transdifferentiation in human mediastinal adipose tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:162439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Siciliano C, Ibrahim M, Scafetta G, et al. Optimization of the isolation and expansion method of human mediastinal‐adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells with virally inactivated GMP‐grade platelet lysate. Cytotechnology. 2015;67(1):165‐174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nyam‐Erdene A, Nebie O, Delila L, et al. Characterization and chromatographic isolation of platelet extracellular vesicles from human platelet lysates for applications in Neuroregenerative medicine. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7(12):5823‐5835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bordin A, Pagano F, Scaccia E, et al. Oral plaque from type 2 diabetic patients reduces the clonogenic capacity of dental pulp‐derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:1516746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Loffredo L, Perri L, Catasca E, et al. Dark chocolate acutely improves walking autonomy in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4):e001072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carnevale R, Raparelli V, Nocella C, et al. Gut‐derived endotoxin stimulates factor VIII secretion from endothelial cells. Implications for hypercoagulability in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):950‐956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Margariti A, Zampetaki A, Xiao Q, et al. Histone deacetylase 7 controls endothelial cell growth through modulation of beta‐catenin. Circ Res. 2010;106(7):1202‐1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Di Carlo A, Beji S, Palmerio S, et al. The nucleolar protein nucleophosmin is physiologically secreted by endothelial cells in response to stress exerting proangiogenic activity both in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dragovic RA, Gardiner C, Brooks AS, et al. Sizing and phenotyping of cellular vesicles using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(6):780‐788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Willms E, Cabanas C, Mager I, Wood MJA, Vader P. Extracellular vesicle heterogeneity: subpopulations, isolation techniques, and diverse functions in cancer progression. Front Immunol. 2018;9:738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Poupardin R, Wolf M, Strunk D. Adherence to minimal experimental requirements for defining extracellular vesicles and their functions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;176:113872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Antich‐Rossello M, Forteza‐Genestra MA, Monjo M, Ramis JM. Platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles for regenerative medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):e13123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, et al. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell. 2019;177(2):428‐445.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oggero S, de Gaetano M, Marcone S, et al. Extracellular vesicles from monocyte/platelet aggregates modulate human atherosclerotic plaque reactivity. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10(6):12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wagner CL, Mascelli MA, Neblock DS, Weisman HF, Coller BS, Jordan RE. Analysis of GPIIb/IIIa receptor number by quantification of 7E3 binding to human platelets. Blood. 1996;88(3):907‐914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Coumans FAW, Brisson AR, Buzas EI, et al. Methodological guidelines to study extracellular vesicles. Circ Res. 2017;120(10):1632‐1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Angelini F, Ionta V, Rossi F, et al. Exosomes isolation protocols: facts and artifacts for cardiac regeneration. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2016;8:303‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosinska J, Lukasik M, Kozubski W. The impact of vascular disease treatment on platelet‐derived microvesicles. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(5–6):627‐644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chiaradia E, Tancini B, Emiliani C, et al. Extracellular vesicles under oxidative stress conditions: biological properties and physiological roles. Cells. 2021;10(7):1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Takac I, Schroder K, Zhang L, et al. The E‐loop is involved in hydrogen peroxide formation by the NADPH oxidase Nox4. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(15):13304‐13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Breton‐Romero R, Lamas S. Hydrogen peroxide signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Redox Biol. 2014;2:529‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, et al. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J. 2007;406(1):105‐114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nagalla S, Shaw C, Kong X, et al. Platelet microRNA‐mRNA coexpression profiles correlate with platelet reactivity. Blood. 2011;117(19):5189‐5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ple H, Landry P, Benham A, Coarfa C, Gunaratne PH, Provost P. The repertoire and features of human platelet microRNAs. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e50746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pienimaeki‐Roemer A, Konovalova T, Musri MM, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of platelet senescence and platelet extracellular vesicles. Transfusion. 2017;57(1):144‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pordzik J, Pisarz K, De Rosa S, et al. The potential role of platelet‐related microRNAs in the development of cardiovascular events in high‐risk populations, including diabetic patients: a review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA‐126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1516‐1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Song W, Liang Q, Cai M, Tian Z. HIF‐1α‐induced up‐regulation of microRNA‐126 contributes to the effectiveness of exercise training on myocardial angiogenesis in myocardial infarction rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(22):12970‐12979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Delila L, Wu YW, Nebie O, et al. Extensive characterization of the composition and functional activities of five preparations of human platelet lysates for dedicated clinical uses. Platelets. 2021;32(2):259‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Refaai MA, Conley GW, Hudson CA, et al. Evaluation of the procoagulant properties of a newly developed platelet modified lysate product. Transfusion. 2020;60(7):1579‐1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chao FC, Kim BK, Houranieh AM, et al. Infusible platelet membrane microvesicles: a potential transfusion substitute for platelets. Transfusion. 1996;36(6):536‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Khodadi E. Platelet function in cardiovascular disease: activation of molecules and activation by molecules. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2020;20(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stark K, Massberg S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(9):666‐682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tang Y, Li J, Wang W, et al. Platelet extracellular vesicles enhance the proangiogenic potential of adipose‐derived stem cells in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kong L, Li K, Gao L, et al. Mediating effects of platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles on PM2.5‐induced vascular endothelial injury. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;198:110652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Merino‐Gonzalez C, Zuniga FA, Escudero C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles promote angiogenesis: potencial clinical application. Front Physiol. 2016;7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hu GW, Li Q, Niu X, et al. Exosomes secreted by human‐induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate limb ischemia by promoting angiogenesis in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tabak S, Schreiber‐Avissar S, Beit‐Yannai E. Extracellular vesicles have variable dose‐dependent effects on cultured draining cells in the eye. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(3):1992‐2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Park WH. The effects of exogenous H2O2 on cell death, reactive oxygen species and glutathione levels in calf pulmonary artery and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31(2):471‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sellke FW, Simons M. Angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease: current status and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1999;58(3):391‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Datla SR, Peshavariya H, Dusting GJ, Mahadev K, Goldstein BJ, Jiang F. Important role of Nox4 type NADPH oxidase in angiogenic responses in human microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(11):2319‐2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kim YW, Byzova TV. Oxidative stress in angiogenesis and vascular disease. Blood. 2014;123(5):625‐631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pratico D, Iuliano L, Pulcinelli FM, Bonavita MS, Gazzaniga PP, Violi F. Hydrogen peroxide triggers activation of human platelets selectively exposed to nonaggregating concentrations of arachidonic acid and collagen. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;119(4):364‐370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Canoso RT, Rodvien R, Scoon K, Levine PH. Hydrogen peroxide and platelet function. Blood. 1974;43(5):645‐656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Martyn KD, Frederick LM, von Loehneysen K, Dinauer MC, Knaus UG. Functional analysis of Nox4 reveals unique characteristics compared to other NADPH oxidases. Cell Signal. 2006;18(1):69‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Altenhofer S, Kleikers PW, Radermacher KA, et al. The NOX toolbox: validating the role of NADPH oxidases in physiology and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(14):2327‐2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bodega G, Alique M, Puebla L, Carracedo J, Ramirez RM. Microvesicles: ROS scavengers and ROS producers. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8(1):1626654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Edelstein LC, McKenzie SE, Shaw C, Holinstat MA, Kunapuli SP, Bray PF. MicroRNAs in platelet production and activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(suppl 1):340‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Landry P, Plante I, Ouellet DL, Perron MP, Rousseau G, Provost P. Existence of a microRNA pathway in anucleate platelets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(9):961‐966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Czajka P, Fitas A, Jakubik D, et al. MicroRNA as potential biomarkers of platelet function on antiplatelet therapy: a review. Front Physiol. 2021;12:652579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Risitano A, Beaulieu LM, Vitseva O, Freedman JE. Platelets and platelet‐like particles mediate intercellular RNA transfer. Blood. 2012;119(26):6288‐6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Laffont B, Corduan A, Rousseau M, et al. Platelet microparticles reprogram macrophage gene expression and function. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(2):311‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Willeit P, Zampetaki A, Dudek K, et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for platelet activation. Circ Res. 2013;112(4):595‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Boyerinas B, Park SM, Hau A, Murmann AE, Peter ME. The role of let‐7 in cell differentiation and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(1):F19‐F36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Di Stefano AB, Massihnia D, Grisafi F, et al. Adipose tissue, angiogenesis and angio‐MIR under physiological and pathological conditions. Eur J Cell Biol. 2019;98(2‐4):53‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bai Y, Lu W, Han N, Bian H, Zhu M. Functions of miR126 and innate immune response. Yi Chuan. 2014;36(7):631‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Luo Q, Guo D, Liu G, Chen G, Hang M, Jin M. Exosomes from MiR‐126‐overexpressing Adscs are therapeutic in relieving acute myocardial Ischaemic injury. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44(6):2105‐2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Knoka E, Trusinskis K, Mazule M, et al. Circulating plasma microRNA‐126, microRNA‐145, and microRNA‐155 and their association with atherosclerotic plaque characteristics. J Clin Transl Res. 2020;5(2):60‐67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Jin F, Xing J. Circulating miR‐126 and miR‐130a levels correlate with lower disease risk, disease severity, and reduced inflammatory cytokine levels in acute ischemic stroke patients. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(10):1757‐1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. de Boer HC, van Solingen C, Prins J, et al. Aspirin treatment hampers the use of plasma microRNA‐126 as a biomarker for the progression of vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(44):3451‐3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, et al. The endothelial‐specific microRNA miR‐126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;15(2):261‐271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, et al. miR‐126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev Cell. 2008;15(2):272‐284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. van Solingen C, Seghers L, Bijkerk R, et al. Antagomir‐mediated silencing of endothelial cell specific microRNA‐126 impairs ischemia‐induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(8A):1577‐1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Cui J, Liu N, Chang Z, et al. Exosomal microRNA‐126 from RIPC serum is involved in hypoxia tolerance in SH‐SY5Y cells by downregulating DNMT3B. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;20:649‐660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Shi CC, Pan LY, Peng ZY, Li JG. MiR‐126 regulated myocardial autophagy on myocardial infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(12):6971‐6979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, et al. Delivery of microRNA‐126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12‐dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2009;2(100):ra81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Jing BQ, Ou Y, Zhao L, Xie Q, Zhang YX. Experimental study on the prevention of liver cancer angiogenesis via miR‐126. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(22):5096‐5100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Zeng Z, Li Y, Pan Y, et al. Cancer‐derived exosomal miR‐25‐3p promotes pre‐metastatic niche formation by inducing vascular permeability and angiogenesis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sarkozy M, Kahan Z, Csont T. A myriad of roles of miR‐25 in health and disease. Oncotarget. 2018;9(30):21580‐21612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]