Abstract

Background

The number of recorded human cowpox cases are recently increasing. The symptoms caused by cowpox virus (CPXV) in a number of human cases are close to the symptoms characteristic of the orthopoxviral human infections caused by monkeypox or smallpox (variola) viruses. Any rapid and reliable real-time PCR method for distinguishing cowpox from smallpox and monkeypox is yet absent.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to develop a quick and reliable real-time TaqMan PCR assay for specific detection of cowpox virus and to determine the sensitivity and specificity of this method.

Study design

Based on aligned nucleotide sequences of orthopoxviruses, we found a virus-specific region in the CPXV genome and selected the oligonucleotide primers and hybridization probe within this region. The specificity of the developed method was tested using a panel of various orthopoxvirus (OPV) DNAs. The sensitivity was determined using the recombinant plasmid carrying a fragment of CPXV DNA and genomic DNA of the CPXV strain GRI-90.

Results

The analytical specificity of this method was determined using DNAs of 17 strains of four OPV species pathogenic for humans and amounted to 100%. The method allows 6 copies of plasmid DNA and 20 copies of CPXV DNA in the reaction mixture to be detected.

Conclusion

A quick and reliable TaqMan PCR assay providing for a highly sensitive and specific detection of CPXV DNA was developed.

Abbreviations: CPXV, cowpox virus; OPV, orthopoxvirus; MPXV, monkeypox virus; VARV, variola virus; VACV, vaccinia virus; ECTV, ectromelia virus; CMLV, camelpox virus; ORF, open reading frame; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism

Keywords: Orthopoxvirus, Cowpox virus, Real-time PCR, Detection

1. Background

Human cowpox is a zoonotic disease; the human cowpox cases are mainly recorded in European countries.1 The natural reservoir of cowpox virus (CPXV) is rodents.2 The virus is transmitted via a direct contact with infected animal, be it a rodent3, 4 or the animals contacting rodents, such as cows,5 cats,6, 7 dogs,8 and others.9, 10 In the majority of cases, the human disease has a benign course with development of local lesions, mainly on hands, forearms, face, and less frequently, other body parts.11, 12, 13, 14 The infection course is accompanied by indisposition and fever; in some cases, generalization of the process is observed.15 In rare cases, when the disease affects eczema patients, its course can be accompanied by severe complications.1, 4 A similar pattern is observed in immunodeficiencies of various etiologies.5, 16, 17 In rare cases, cowpox can have a lethal outcome.18

Along with monkeypox (MPXV), variola (VARV), and vaccinia (VACV) viruses pathogenic for humans, CPXV belongs to the members of the genus Orthopoxvirus. All the representatives of this group are genetically close; their antigenic structures are also very similar.19, 20, 21, 22

In 1980, the WHO officially declared smallpox eradicated on the globe and recommended to stop the vaccination against this disease; in particular, this was determined by the complications accompanying the vaccination. However, the cessation of vaccination had its negative consequences. The human cohort completely lacking the immunity to VARV and other orthopoxviruses (CPXV and MPXV) increases annually; consequently, the reports on human cases of these orthopoxvirus infections have become numerous.23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Recently, the number of recorded human cowpox cases in European countries has increased.18 An unprecedented outbreak of human cowpox occurred in December 2008 to January 2009 in France and Germany28, 29 with 18 cases in Germany and 12 cases in France.30 This demonstrates the need in special efforts aimed at training of medical staff and search for the antivirals specific for orthopoxviruses.18 However, the most important problem is to develop a rapid and reliable method for CPXV diagnosis. This is determined by several reasons. A correct diagnosing is necessary for choosing the treatment strategy. Moreover, the quickness of diagnosis is no less important than the accuracy. All the orthopoxviruses pathogenic for humans cause a similar clinical pattern at the early stages; however, they display different contagiousness and pathogenicity. It is most important to obtain the information about the infectious agent to undertake the corresponding anti-epidemic measures. Finally, note that numerous rapid and accurate specific diagnostic tools have been developed for VARV and MPXV,31, 32, 33, 34 whereas such method for detection and simultaneous differentiation of CPXV is absent.

Currently, CPXV is diagnosed by serological35 and biological6 methods. PCR in combination with RFLP assay36, 37, 38 and sequencing39 were proposed for CPXV identification. However, both these methods are not free from shortcomings. As has been demonstrated, RFLP assay of DNA of various CPXV strains gives a polymorphic pattern, which hinders interpretation of results.36 Sequencing gives a precise information; however, this method requires expensive equipment and is inapplicable under field conditions. Of the molecular diagnostic methods, the real-time PCR is becoming ever more popular. This method combines quickness and reliability, which allowed this approach to be successfully applied to VARV and MPXV diagnostics.34, 31 Earlier attempts to use real-time PCR for diagnosing human cowpox gave insufficient specificity only to a level of genus identification.6, 35 In this work, we for the first time propose a species-specific CPXV identification based on real-time PCR assay.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to develop a quick and reliable real-time TaqMan PCR assay for specific detection of cowpox virus and to determine the sensitivity and specificity of this method.

3. Study design

To calculate the oligonucleotide primers and probe, all the currently known 85 complete genome sequences of the orthopoxviruses pathogenic for humans as well as sequences of other members of the genus Orthopoxvirus were aligned. The nucleotide sequences of orthopoxvirus strains were extracted from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.hih.gov). The nucleotide sequence of ectromelia virus strain Naval was obtained at www.sanger.ac.uk. The nucleotide sequences were aligned using the BioEdit v.7.0 and MUSCLE v.3.6 programs. The region of CPXV GRI-90 ORF D11L, unique for cowpox virus,40 was chosen as the target for the oligonucleotide fluorescent probe. The criteria for primer selection were a specific amplification of orthopoxvirus DNA independently of the presence of related species and the length of the produced amplicon not exceeding 250 bp. The proposed primer pair was analyzed using the program Oligo v.6.31 and tested for the presence of homology to the nucleotide sequences of other viruses and human genome using the BLAST program. The oligonucleotide primers CPXV_D11L_upper (5′-AAAACTCTCCACTTTCCATCTTCT-3′), CPXV_D11L_lower (5′-GCATTCAGATACGGATACTGATTC-3′) and the probe CPXV_D11L_probe (HEX-5′-CCACAATCAGGATCTGTAAAGCGAGC-3′-BHQ1) were synthesized in an ABI 3400 DNA/RNA Synthesizer (DNA sintez, Moscow, Russia).

A recombinant plasmid pCD11 carrying CPXV GRI-90 ORF D11L40 was constructed. The fragment of CPXV DNA was obtained by PCR using the primer pair 5′-CCCAAGCTTTTATTTTCTAACGAATGTAACGA-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCGAACGTATCAACATGGTCAAG-3′. For further cloning, the sites for restriction endonucleases HindIII and BamHI were introduced into the primers. The amplification product with a length of 1944 bp was hydrolyzed with the restriction endonucleases HindIII and BamHI and purified with a Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). The resulting DNA fragment was ligated with the plasmid vector pBluescript II SK(+), also hydrolyzed with HindIII and BamHI. Competent Escherichia coli strain Dh5αF′ cells were transformed with the ligation product and plated onto the solid selective medium STI containing 200 mg/ml ampicillin and 40 mg/ml X-gal to select the transformants. The recombinant plasmid pCD11 was isolated using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAGEN). The presence of the target insert in the selected hybrid plasmids was verified by restriction analysis, PCR assay, and sequencing. The concentration of purified plasmid pCD11 was determined spectrophotometrically in an Ultrospec 3000 pro.

For iQ 5 (BioRad, USA) and Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Australia), PCR analysis with 5′-terminal label cleavage (TaqMan system) was performed in 25 μl of the reaction mixture containing 200 μM dNTP, 10 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM KCl, 0.08% Nonidet P40, 5 mM MgCl2, 300 nM primers, and 250 nM hybridization probe, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, USA), and 1 μl of the analyzed DNA solution. For a Real-Time PCR System 7500 (Applied Biosystems, USA), the reaction mixture contained 1× TaqMan® Buffer A, 200 μM dNTP, 5 mM MgCl2, 300 nM primers, 250 nM hybridization probe, 0.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold® DNA polymerase, and 1 μl of the analyzed DNA solution.

PCR with recording of fluorescence intensity in iQ 5 and Rotor-Gene 6000 was conducted according to the following mode: 10 min at 95 °C and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 58 °C, and 30 s at 60 °C; with Real-Time PCR System 7500: 10 min at 95 °C and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 58 °C.

The specificity of the assay was assessed using a panel of orthopoxvirus DNAs (Table 1 ). Chickenpox virus (Table 1) and human (Medigen, Novosibirsk, Russia) DNAs were used as negative controls. Blood and tissue samples of experimental animals infected with CPXV strain GRI-90 were used as clinical specimens.

Table 1.

The list of virus strains whose DNA was used in real-time PCR.

| Species | Strain | DNA source |

|---|---|---|

| Cowpox virus | GRI-90 | 1 |

| OPV-Claus | 2 | |

| 88-Lunge | 2 | |

| OPV-90/2 | 2 | |

| OPV-90/5 | 2 | |

| OPV-89/3 | 2 | |

| OPV-89/4 | 2 | |

| OPV-98/5 | 2 | |

| Vaccinia virus | LIVP | 1 |

| Elestree 3399 | 1 | |

| Western Reserve | 1 | |

| Monkeypox virus | CDC#v79-I-005 | 3 |

| CDC#v97-I-004 | 3 | |

| Variola virus | Ngami | 1 |

| 65/58 | 1 | |

| Butler | 1 | |

| Congo 9 | 1 | |

| Chickenpox virus | VZV No. 4 | 4 |

(1) Virus DNAs were isolated from the strains deposited with the collection of the SRC VB Vector.

(2) Virus DNAs were kindly provided by H. Meyer (Munich, Germany).

(3) Virus DNAs were kindly provided by J. Esposito (Atlanta, United States).

(4) Virus DNA was kindly provided by M.A. Susloparov, SRC VB Vector.

4. Results

The TaqMan assay occupies a top position among the real-time PCR formats. This method utilizes a 5′-exonuclease activity of the Taq polymerase. The fluorescence signal is accumulated due to liberation of the fluorescent label conjugated with oligonucleotide hybridization probe.41 For the first time, this approach to OPV diagnostics was applied to VARV.42 Recently, TaqMan assay was used to develop several methods for detecting VARV32, 43 and MPXV31, 33 DNA; however, the specific method for detecting CPXV is still absent.

When selecting the oligonucleotide primers and hybridization probe for detecting CPXV DNA, we analyzed the nucleotide sequences of 85 strains of six OPV species, namely, VARV, MPXV, CPXV, VACV, ectromelia (mousepox) virus (ECTV), and camelpox virus (CMLV).

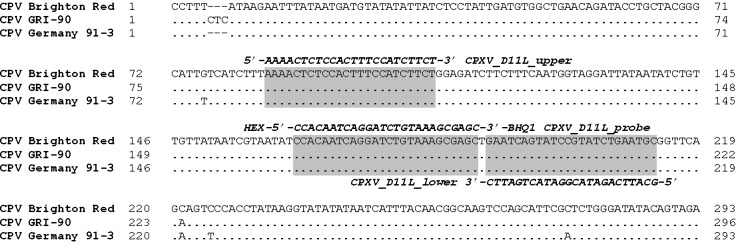

The procedure of primer selection for real-time PCR assay is similar to the analogous procedure for a standard PCR; the main distinction is a short length of the produced amplicon, no longer than 250 bp. When selecting the hybridization probe, we assumed that its melting temperature had to exceed that for the primers by 8–10 °C and its sequence had to differ from any other genomic region in any other OPV by at least two nucleotides.44 The only region in the nucleotide sequence of CPXV ORF D11L meeting all these requirements is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the ORF D11L sequence of CPXV strain GRI-90 with the corresponding regions of the strains Germany 91-3 and Brighton Red. The identical nucleotides in the compared sequences of virus genomes relative to the CPXV Brighton Red sequence are denoted with dots and the deletions, with dashes. The positions of nucleotides in the analyzed DNA segment are shown to the left and right. The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers CPXV_D11L_upper and CPXV_D11L_lower and hybridization probe CPXV_D11L_probe for fluorescence detection of CPXV DNA are boldfaced.

We used three devices for testing the primers and probe: Real-Time PCR System 7500 (Applied Biosystems, USA), iQ 5 (BioRad, USA), and Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Australia). Two different Taq polymerases—AmpliTaq Gold® DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, USA) with the corresponding reagents and Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, USA)—were used. The testing was performed with the help of a DNA panel (Table 1).

The performed analysis has demonstrated a high detection specificity. A positive signal was observed only for the specimens containing CPXV DNA used in this work (Table 1). The mixture of primers and probe gave no fluorescence signal with either human or chickenpox DNAs. This result was obtained with all the used devices and reagents. Thus, the specificity of the developed oligonucleotide primers and fluorescent probe in our experiments was 100%.

In the experiment of intranasal infection of mice with CPXV strain GRI-90 using developed method the viral DNA was identified from 3 to 10 days in the lungs, spleen, liver, blood, whereas the titration in CV-1 cell culture revealed the CPXV only in the lungs. Analysis of clinical samples did not detect any unexpected amplicons. Thus, the developed real-time TaqMan PCR assay allows reliable and highly specific identification of CPXV.

We have assessed the sensitivity of the developed method. For this purpose, we constructed the recombinant plasmid pCD11 carrying a fragment of the CPXV GRI-90 ORF D11L. After measuring the concentration, tenfold dilutions of the plasmid from 250 μg/ml to 25 fg/ml (namely, 6 × 1013 to 6 × 103 copies/ml) were prepared. Each dilution was made in triplicate. Fig. 2 shows the results of real-time PCR assay for the dilutions of the plasmid recorded in an iQ 5 device. The minimal quantity of the plasmid detectable by this device was six copies in the reaction mixture. The minimal quantity of the plasmid detectable using a Real-Time PCR System 7500 device was also six copies. However, a Rotor-Gene 6000 was able to detect no less than 60 copies in the reaction mixture.

Fig. 2.

The dependences of fluorescence signal on the number of real-time PCR cycles recorded by an iQ 5 (BioRad) using the oligonucleotide primers and probe calculated for the region of CPXV GRI-90 ORF D11L. The groups of curves reflect the shift in the threshold cycle depending on the concentration of recombinant plasmid; Cycle, the number of real-time PCR cycle, and RFU, the value of fluorescence signal.

Also we assessed limit of detection on genomic viral DNA purified from CPXV virions. Sample of the CPXV strain GRI-90, purified in sucrose density gradient, with the known titer determined in cell culture and by electron microscoping was used. After DNA isolation, using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN), it was diluted so that a known number of the virus DNA molecules were present in real-time PCR reaction mixture. Experiments demonstrated that reproducibly detected approximately 20 copies of the genomic CPXV DNAs using a Real-Time PCR System 7500 device.

5. Discussion

The human cowpox cases were rather rare1; however, an increase in the number of human cowpox cases has recently revealed.18 Correspondingly, creation of a rapid and reliable method for CPXV diagnosis is a topical problem. We have performed a computer analysis of all available orthopoxvirus genomic sequences and, based on the aligned nucleotide sequences, selected the oligonucleotide primers and fluorescently labeled hybridization probe for real-time TaqMan PCR assay to perform a species-specific CPXV identification. The primers and probe were experimentally tested using a panel of orthopoxvirus DNAs (Table 1). Three devices—Real-Time PCR System 7500, iQ 5, and Rotor-Gene 6000—and two polymerases, AmpliTaq Gold® DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, USA) and Taq polymerase (Fermentas, USA), were used. The specificity of CPXV DNA detection in all cases was 100%. To assess the sensitivity of the method, the recombinant plasmid carrying a fragment of CPXV GRI-90 ORF D11L was constructed. The sensitivity was determined using all these three devices. The minimal detectable quantity for iQ 5 and Real-Time PCR System 7500 was six copies in the reaction mixture and 60 copies for Rotor-Gene 6000. For the viral genomic DNA, the sensitivity was determined using Real-Time PCR System 7500 and compounded 20 copies of the CPXV DNA.

Thus, we for the first time selected a pair of oligonucleotide primers and the fluorescently labeled hybridization probe that provide for a reliable and specific detection of CPXV DNA by real-time PCR assay. The proposed method displays a high sensitivity and provides for detecting 6–60 copies of the plasmid carrying a CPXV specific DNA sequence and no less than 20 copies of the complete viral DNA.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Baxby D., Bennett M., Getty B. Human cowpox 1969–93: a review based on 54 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:598–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crouch A.C., Baxby D., McCracken C.M., Gaskell R.M., Bennet M. Serological evidence for the reservoir hosts of cowpox virus in British wildlife. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:185–191. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfs T.F., Wagenaar J.A., Niesters H.G., Osterhaus A.D. Rat-to-human transmission of cowpox infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1495–1496. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.020089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honlinger B., Huemer H.P., Romani N., Czerny C.-P., Eisendel K., Hopel R. Generalized cowpox infection probably transmitted from a rat. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:451–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claudy A.L., Gaudin O.G., Granouillet R. Pox virus infection in Darier's disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1982;7:261–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1982.tb02425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnekoh B., Falk K., Reckling K., Kenklies S., Nitsche A., Ghebremedhin B., et al. Cowpox infection transmitted from a domestic cat. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haenssle H.A., Kiessling J., Kempf V.A., Fuchs T., Neumann C., Emmert S. Orthopoxvirus infection transmitted by a domestic cat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:S1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelkonen P.M., Tarvainen K., Hynninen A., Kallio E.R.K., Henttonen H., Palva A., et al. Cowpox with severe generalized eruption, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1458–1461. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.020814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurth A., Wibbelt, Gerber H., Petschaelis A., Pauli G., Nitsche A. Rat-to-elephant-to-human transmission of cowpox virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:670–671. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.070817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marennikova S.S., Shelukhina E.M., Efremova E.V. New outlook on the biology of cowpox virus. Acta Virol. 1984;28:437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxby D. Is cowpox misnamed? A review of 10 human cases. Br Med J. 1977;1:1379–1381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6073.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feuerstein-Kadgien B., Korn K. Cowpox infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm010078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajan N., Carmichael A.J., McCarron B.M. Human cowpox: presentation and investigation in an era of bioterrorism. J Infect. 2005;51:e167–e169. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marennikova S.S., Gashnikov P.V., Zhukova O.A., Ryabchikova E.I., Strel’tsov V.V., Ryazankina O.I., et al. Biotype and genetic characterization of a cowpox virus isolate that caused infection of a child. Zh Mikrobiol. 1996;4:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackford S., Roberts D.L., Thomas P.D. Cowpox infection causing a generalized eruption in a patient with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:628–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pahlitzsch R., Hammarin A., Widell A. A case of facial cellulitis and necrotizing lymphadenitis due to cowpox virus infection. Clin Infect Diseases. 2006;43:737–742. doi: 10.1086/506937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tryland M., Myrmel H., Holtet L., Haukenes G., Traavik T. Clinical cowpox cases in Norway. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:301–303. doi: 10.1080/00365549850160972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vorou R.M., Papavassiliou V.G., Pierroutsakos I.N. Cowpox virus infection: an emerging health threat. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:153–156. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f44c74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shchelkunov S.N., Marennikova S.S., Moyer R.W. Springer; New York: 2005. Orthopoxviruses pathogenic for humans. 425. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shchelkunov S.N., Resenchuk S.M., Totmenin A.V., Blinov V.M., Marennikova S.S., Sandakhchiev L.S. Comparison of the genetic maps of variola and vaccinia viruses. FEBS Lett. 1993;327:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shchelkunov S.N. Functional organization of variola major and vaccinia virus genomes. Virus Genes. 1995;10:53–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01724297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shchelkunov S.N., Totmenin A.V., Babkin I.V., Safronov P.F., Ryazankina O.I., Petrov N.A., et al. Human monkeypox and smallpox viruses: genomic comparison. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moussatche N., Damaso C.R., McFadden G. When good vaccines go wild: feral orthopoxvirus in developing countries and beyond. J Infect Dev Countries. 2008;2:156–173. doi: 10.3855/jidc.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nitsche A. Sporadic human cases of cowpox in Germany. Eurosurveillance. 2007;12:3178–3179. doi: 10.2807/esw.12.16.03178-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed K.D., Melski J.W., Graham M.B., Regnery R.L., Sotir M.J., Wegner M.V., et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strenger V., Muller M., Richter S., Revilla-Fernandez S., Nitsche A., Klee S.R., et al. A 17-year-old girl with a black eschar. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:133–134. doi: 10.1086/595004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trindade G.S., Guedes M.I., Drumond B.P., Mota B.E.F., Abrahao J.S., Lobato Z.I.P. Zoonotic vaccinia virus: clinical and immunological characteristics in a naturally infected patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:e37–40. doi: 10.1086/595856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campe H., Zimmermann P., Glos K., Bayer M., Bergemann H., Dreweck C., et al. Cowpox virus transmission from pet rats to humans, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:777–780. doi: 10.3201/eid1505.090159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ninove L., Domart Y., Vervel C., Voinot C., Salez N., Raoult D., et al. Cowpox virus transmission from pet rats to humans, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:781–784. doi: 10.3201/eid1505.090235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control . 2009. Cowpox in Germany and France related to rodent pets.http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/files/pdf/Health_topics/RA_Cowpox_updated.pdf Feb 11. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y., Olson V.A., Laue T., Laker M.T., Damon I.K. Detection of monkeypox virus with real-time PCR assays. J Clin Virol. 2006;36:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulesh D.A., Baker R.O., Loveless B.M., Norwood D., Zwiers S.H., Mucker E., et al. Smallpox and pan-orthopox virus detection by real-time 3′-minor groove binder TaqMan assays on the Roche LightCycler and the Cepheid Smart Cycler platforms. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:601–609. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.601-609.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulesh D.A., Loveless B.M., Norwood D., Garrison J., Whitehous C.A., Hartmann C., et al. Monkeypox virus detection in rodents using real-time 3′-minor groove binder TaqMan assay on Roche LightCycler. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1200–1208. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim M.S., Kulesh D.A., Saleh S.S., Damon I.K., Esposito J.J., Schmaljohn A.L., et al. Real-time PCR assay to detect smallpox virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3835–3839. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3835-3839.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nitsche A., Kurth A., Pauli G. Viremia in human Cowpox virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loparev V.N., Massung R.F., Esposito J.J., Meyer H. Detection and differentiation of old world orthopoxviruses: restriction fragment length polymorphism of the crmB gene region. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:94–100. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.94-100.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schupp P., Pfeffer M., Meyer H., Burck G., Kolmel K., Neumann C. Cowpox virus in a 12-year-old boy: rapid identification by an orthopoxvirus-specific polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:146–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wienecke R., Wolff H., Schaller M., Meyer H., Plewig G. Cowpox virus infection in an 11-year-old girl. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:892–894. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carletti F., Bordi L., Castilletti C., Di Caro A., Falasca L., Gioia C. Cat-to-human orthopoxvirus transmission northeastern Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:499–500. doi: 10.3201/eid1503.080813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shchelkunov S.N., Safronov P.F., Totmenin A.V., Petrov N.A., Ryazankina O.I., Gutorov V.V., et al. The genomic sequence analysis of the left and right species-specific terminal region of a cowpox virus strain reveals unique sequences and a cluster of intact ORFs for immunomodulatory and host range proteins. Virology. 1998;243:432–460. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackey I.H., Arden K.E., Nitsche A. Real-time PCR in virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1292–1305. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibrahim M.S., Esposito J.J., Jahrling P.B., Lofts R.S. The potential of 5′ nuclease PCR for detection a single-base polymorphism in orthopoxvirus. Mol Cell Probes. 1997;11:143–147. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1996.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fedele C.G., Negredo A., Molero F., Sanchez-Seco M.P., Tenorio A. Use of Controlled real-time genome amplification for detection of variola virus and other orthopoxviruses infecting humans. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4464–4470. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00276-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackay I.M. Horizon Press/Caister Academic Press; I.M. United Kingdom: 2007. Real-time PCR in microbiology from diagnosis to characterization edited by Mackay. p. 455. [Google Scholar]