SUMMARY

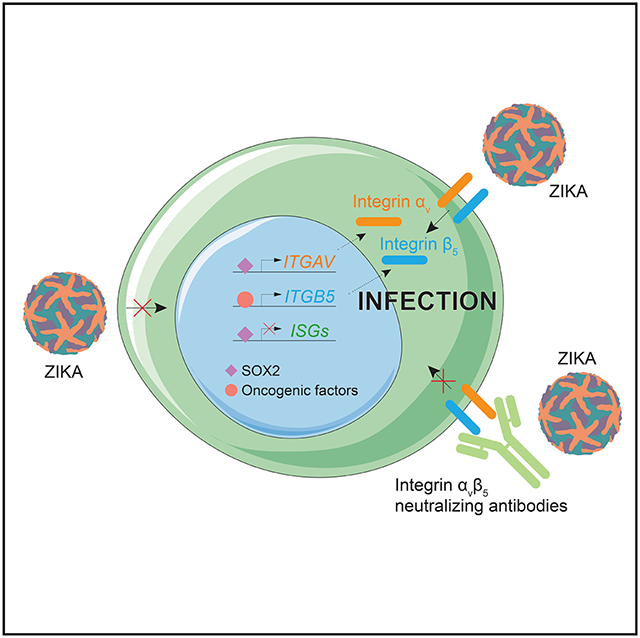

Zika virus (ZIKV) causes microcephaly by killing neural precursor cells (NPCs) and other brain cells. ZIKV also displays therapeutic oncolytic activity against glioblastoma (GBM) stem cells (GSCs). Here we demonstrate that ZIKV preferentially infected and killed GSCs and stem-like cells in medulloblastoma and ependymoma in a SOX2-dependent manner. Targeting SOX2 severely attenuated ZIKV infection, in contrast to AXL. As mechanisms of SOX2-mediated ZIKV infection, we identified inverse expression of antiviral interferon response genes (ISGs) and positive correlation with integrin αv (ITGAV). ZIKV infection was disrupted by genetic targeting of ITGAV or its binding partner ITGB5 and by an antibody specific for integrin αvβ5. ZIKV selectively eliminated GSCs from species-matched human mature cerebral organoids and GBM surgical specimens, which was reversed by integrin αvβ5 inhibition. Collectively, our studies identify integrin αvβ5 as a functional cancer stem cell marker essential for GBM maintenance and ZIKV infection, providing potential brain tumor therapy.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Zika virus causes microcephaly by killing neural precursor cells but also acts as an oncolytic virus against glioblastoma. Zika preferentially targets glioblastoma stem cells through core stem cell transcription factor downregulation of innate immunity and induction of internalization through an integrin heterodimer that marks cancer stem cells.

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM) ranks among the most lethal of all human cancers, with current therapies offering only palliation (Stupp et al., 2005). Replication-competent oncolytic viruses have been employed against GBM and other types of brain cancer (Foreman et al., 2017). Oncolytic viruses may offer selective targeting, internalization, and killing of tumor cells while sparing normal tissues. Because GBM cells are highly invasive, preventing complete surgical resection and cure, neurotropic viruses can target cells protected from chemotherapy and other systemic therapies by the blood-brain barrier. Several oncolytic viruses have been investigated in preclinical and clinical trials for brain tumors (Russell et al., 2012). GBMs contain self-renewing, highly tumorigenic stem-like cells, called GBM stem cells (GSCs), that display preferential therapeutic resistance, invasion into normal brain tissue, stimulation of neoangiogenesis, and tumor immune escape (Singh et al., 2003; Bao et al., 2006b; Wu et al., 2010; Bach et al., 2013). Previous studies have suggested that oncolytic viruses can be engineered to target GSCs (Wakimoto et al., 2009; Allen et al., 2013; Bach et al., 2013; Zemp et al., 2013; Josupeit et al., 2016). Thus, we hypothesized that an oncolytic virus targeting effort could be optimized by leveraging neurotropic viruses that preferentially target specific cell types, such as neural precursor cells (NPCs).

In 2015, a Zika virus (ZIKV) epidemic in Central and South America became a global health emergency (Heymann et al., 2016) following a dramatic increase in the number of newborns with microcephaly and other congenital anomalies (Nowakowski et al., 2016; Oliveira Melo et al., 2016; Schuler-Faccini et al., 2016). Infected adults are often asymptomatic, whereas ZIKV infection of pregnant mothers can be associated with developmental and neurological disorders in subsequent live births (Petersen et al., 2016). The neurotropism and neurovirulence of ZIKV have been appreciated in model systems, confirming a causal link between ZIKV and birth defects (Lazear et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Miner et al., 2016). Numerous studies have shown that different cell populations in the nervous and immune systems are differentially susceptible to ZIKV infection (Retallack et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2016; Foo et al., 2017; Michlmayr et al., 2017; Oh et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018a; Mesci et al., 2018). One challenge in predicting the tropism of ZIKV has been the lack of a consistent molecular pathway mediating cellular infection of ZIKV. AXL has been proposed to mediate ZIKV infection of astrocytes but not NPCs via bridging by its natural ligand, Gas6 (Meertens et al., 2017), but AXL may have only indirect effects on ZIKV infection of astrocytes because of its role in modulating antiviral immunity (Chen et al., 2018a). To date, the identity of the ZIKV entry factor remains controversial (Nowakowski et al., 2016; Wells et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018a).

We recently reported that ZIKV selectively kills patient-derived GSCs compared with differentiated GBM cells (DGCs) in culture, tumor organoids, and slice cultures (Zhu et al., 2017). These observations have been confirmed by others (Kaid et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018b). Although the use of wild-type ZIKV is unlikely to be directly translated into clinical use for GBM patients, we hypothesized that interrogating the molecular mechanisms of ZIKV in GSCs could not only improve the potential application of future modified ZIKV in neuro-oncology but also elucidate mechanisms by which ZIKV gains entry into brain cells.

RESULTS

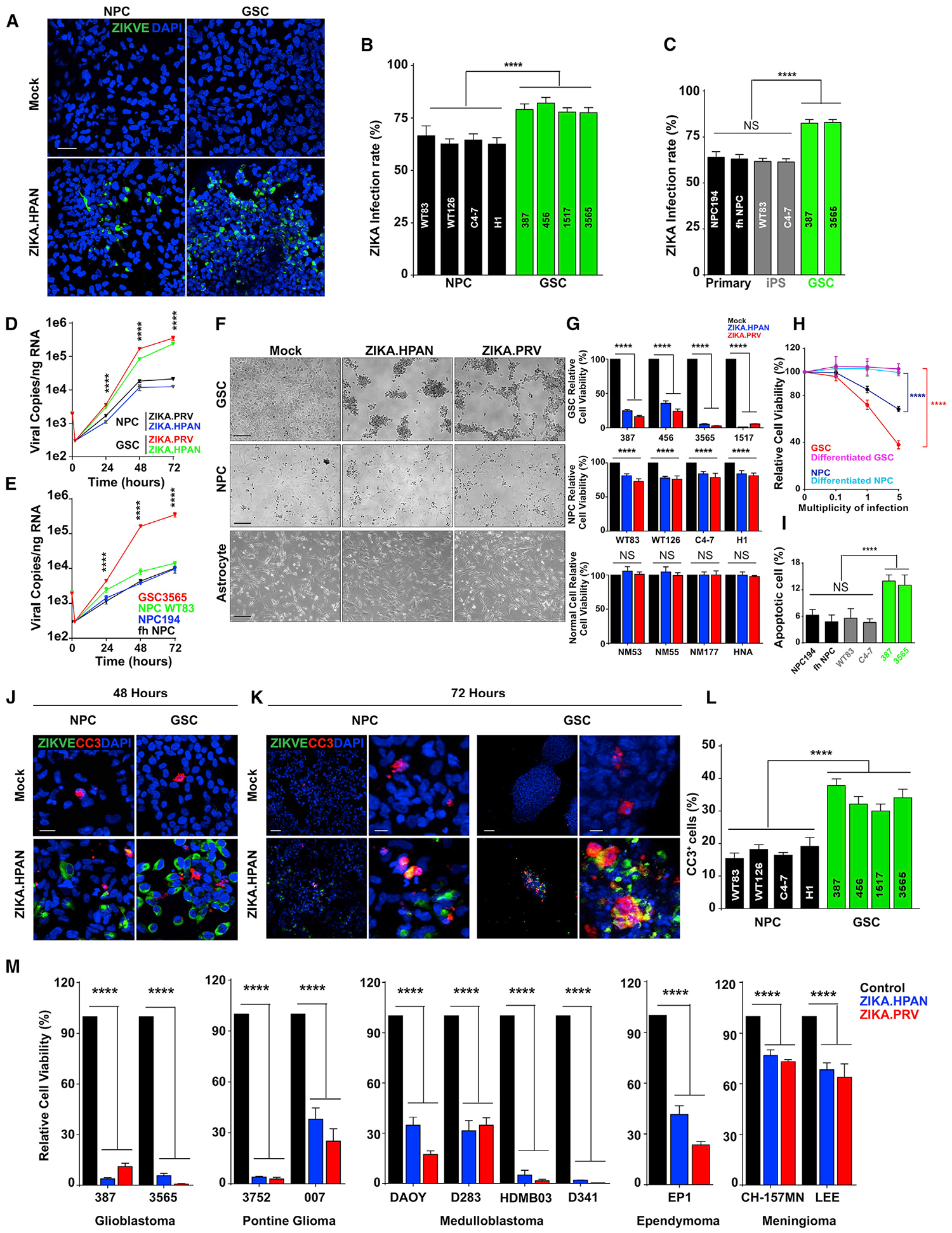

ZIKV Preferentially Infects and Kills Brain Tumor Stem Cells

To determine the potential of ZIKV to achieve preferential anti-tumor efficacy against GSCs with limited toxicity for normal brain, we compared ZIKV infection of GSCs with human NPCs derived from either induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or primary tissues. ZIKV preferentially infected patient-derived GSCs, as quantified by both detection of ZIKV envelope protein (ZIKV-E) (Figures 1A–1C) and viral RNA (Figures 1D and 1E). Although the infection of GSCs was moderately higher than that of normal NPCs, ZIKV induced greater cell death in GSCs (Figures 1F–1I). ZIKV reduced GSC numbers through induction of apoptotic cell death and reduced proliferation (Figures 1J–1L, S1M, and S1N). These results were validated in a panel of 5 GSCs and 5 NPCs from different genetic backgrounds (Figures S1A–S1I and S1N). Although NPCs were less sensitive to ZIKV than GSCs, NPCs were killed by ZIKV, but over a longer time course than GSCs (Figures S1J–S1L and S1N), associated with mildly lower apoptosis (Figure S1O) and induction of differentiation (Figures S1O and S1P).

Figure 1. Zika Virus (ZIKV) Infects and Kills GBM Stem Cells (GSCs) More Efficiently Than Neural Precursor Cells (NPCs).

(A) Representative immunostaining for ZIKV envelope protein (ZIKV-E, green) and DAPI (blue) of GSCs and forebrain-specific NPCs 48 h post-infection (p.i.) with ZIKV. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(B) Quantification of infection efficiency in four GSC and NPC lines 48 h p.i. with ZIKV.

(C) Quantification of ZIKV+ cells in a panel of human GSCs and NPCs.

(D) Kinetics of viral RNA copies p.i. with ZIKV by measuring viral RNA copies by qRT-PCR in NPC C4–7 and GSC3565.

(E) ZIKV infection efficiency of GSCs and NPCs was measured by direct measurement of viral RNA copies.

(F) Representative bright-field images 5 days p.i. with ZIKV for GSCs, NPCs, and primary astrocytes. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(G) Cell viability normalized to day 5 mock, as measured 5 days p.i. with ZIKV for GSCs, NPCs, and primary astrocytes.

(H) GSCs (GSC3565), differentiated GSCs, NPCs (NPC C4–7), and differentiated NPCs were assayed for cell viability 72 h p.i. with ZIKV.

(I) Apoptosis of GSCs (387, 3565) and primary (NPC194, fetal human [fh] NPC) or iPSC-derived NPCs (WT83, C4–7) p.i. with ZIKV was measured by cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) staining.

(J) Representative immunostaining for ZIKV-E (green), CC3 (red), and DAPI (blue) of GSCs and forebrain-specific NPCs 48 h p.i. with ZIKV. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(K) Representative immunostaining for ZIKV-E (green), CC3 (red), and DAPI (blue) of GSCs and forebrain-specific NPCs 72 h p.i. with ZIKV. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(L) Quantification of the percentage of CC3+ cells in DAPI+ cells for GSCs and NPCs 72 h p.i. with ZIKV.

(M) Cell viability of patient-derived cultures from GBM (387 and 3565), pontine glioma (3752 and 007), meningioma (CH-157MN, IOMM-LEE), ependymoma (EP1), and medulloblastoma cell lines (DAOY, D283, HDMB03, D341) 72 h after ZIKV infection.

Experiments were performed in two biological replicates with three technical repeats. Values represent mean ± SEM. NS, no significance. ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

GBMs represent the brain cancer for which the tumor hierarchy is most clearly delineated, but other brain tumors, especially pediatric brain tumors, contain stem-like tumor cells (Bao et al., 2006a; Mack et al., 2018). We interrogated the anti-tumor efficacy of ZIKV against 2 pediatric pontine gliomas, 4 medulloblastomas, an ependymoma, and 2 meningiomas grown under serum-free conditions to enrich for stem-like populations (Wang et al., 2017a). For all models except meningiomas, ZIKV induced apoptotic cell death (Figures 1M and S2A–S2C). Unlike the other tumor types tested, meningioma is not intrinsic to the brain parenchyma; it is posited to arise from the arachnoid granulations (Buetow et al., 1991). Collectively, these results establish preferential ZIKV killing of stem-like brain tumor cells, supporting its potential utility as a platform for an oncolytic virus.

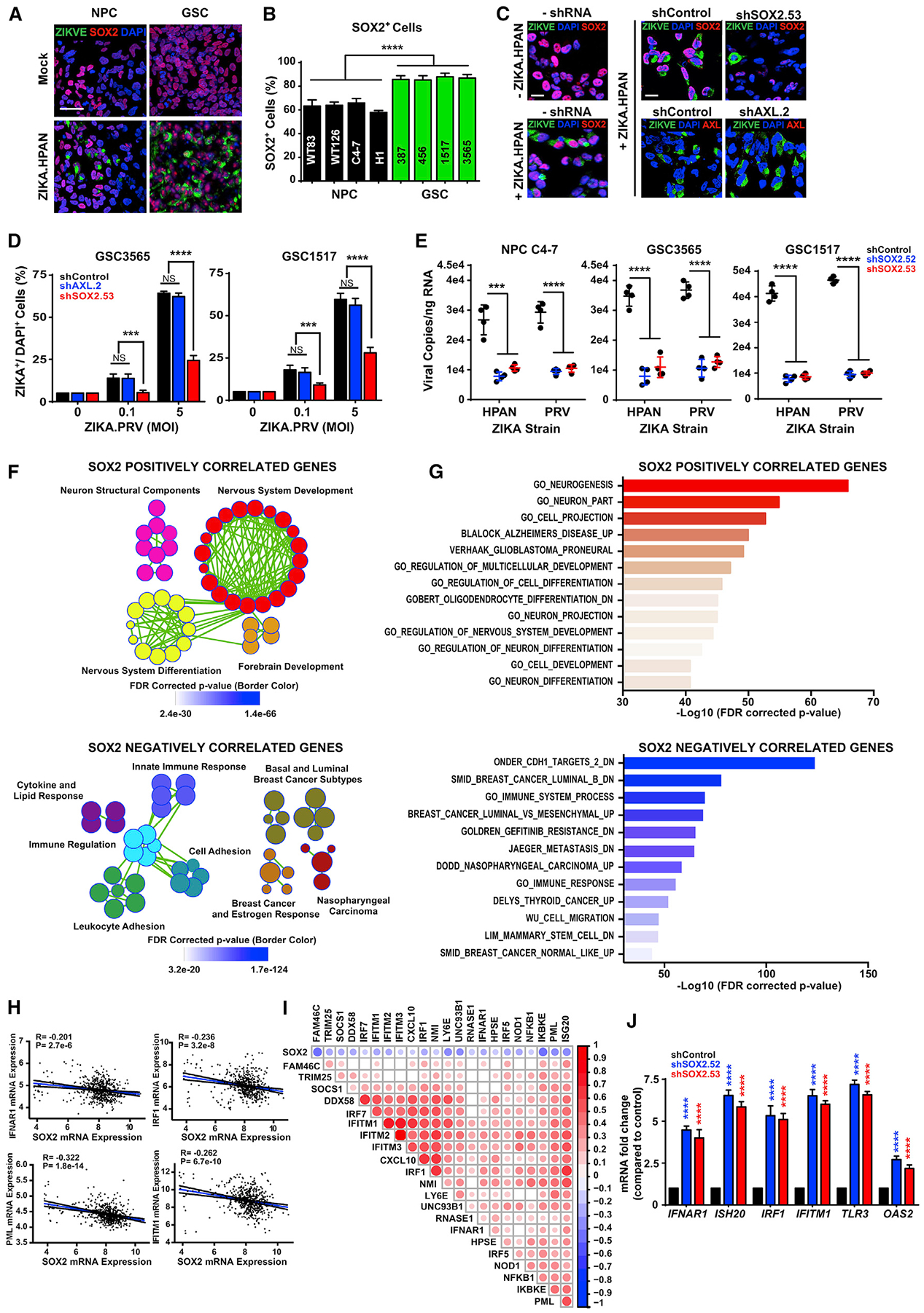

SOX2 Modulates Infection of GSCs Associated with Repression of Innate Antiviral Responses

To define the molecular determinants of ZIKV infection of GSCs, we investigated a core regulator of GSCs reported to mark NPCs infected by ZIKV, SOX2 (Souza et al., 2016). SOX2 is an SRY-box transcription factor that is expressed at high levels during neural development and contributes to induced pluripotency (Sarkar and Hochedlinger, 2013). GSCs express high levels of SOX2, and targeting SOX2 expression attenuates GSC maintenance (Gangemi et al., 2009). Nearly all ZIKV-infected NPCs and GSCs were SOX2+, and most SOX2+ cells were infected by ZIKV (Figures 2A and 2B). The fraction of ZIKV-infected cells mirrored the fraction of SOX2+ cells in other brain tumor types (Figures S2D and S2E); meningioma cultures had both the lowest fraction of SOX2+ cells and ZIKV infection. GSCs expressed higher levels of SOX2 than NPCs by immunoblot (Figure S2F).

Figure 2. SOX2 Mediates Infection of GSCs Associated with Repression of Innate Antiviral Responses.

(A) Representative immunostaining for ZIKV-E (green), SOX2 (red), and DAPI (blue) of GSCs and forebrain-specific hiPSC-derived NPCs 48 h p.i. with ZIKV. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(B) Quantification of the percentage of SOX2+ cells in DAPI+ cells for GSCs and NPCs 48 h p.i. with ZIKV.

(C) Representative immunostaining for ZIKV-E (green), SOX2 or AXL (red), and DAPI (blue) of GSCs (GSC3565) without transduction (shRNA) or transduced with control shRNA (shCONT), AXL shRNA (shAXL.2), or SOX2 shRNA (shSOX2.53) for 72 h and then 48 h with ZIKV infection. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(D) Quantification of the percentage of ZIKV+ cells in DAPI+ cells in GSCs 1517 and 3565 under conditions for (C), with a range of ZIKV infection.

(E) Viral copy number by qRT-PCR of GSCs (GSC3565 or GSC1517) or NPC C4–7 transduced with either shCONT or SOX2 shRNA (shSOX2.52 or shSOX2.53) for 72 h and then either exposed to mock conditions or infected with ZIKV for another 72 h. All comparisons are versus shCONT.

(F) Gene set enrichment (GSE) bubble plots showing pathways positively (top, r > 0.4) or negatively (bottom, r < −0.4) correlated with SOX2 expression in the TCGA GBM HG-U133A microarray dataset. Each circle represents an enriched pathway, with the border color indicating the false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected p value.

(G) GSE graph showing the top pathway enrichments positively or negatively correlated with SOX2 as described in (F).

(H) Correlation of mRNA levels of SOX2 with IFNAR1, IRF1, promyelocytic leukemia (PML), and IFITIM1 from the TCGA GBM HG-U133A microarray dataset.

(I) Correlation between SOX2 with ISGs from the TCGA GBM HG-U133A microarray dataset. The size and color of the dots indicate the degree of correlation (p < 0.001). Blank cells indicate a non-significant correlation.

(J) qPCR of ISGs (IFNAR-1, ISH20, IRF1, IFITM1, TLR3, and OAS2) in GSCs (GSC3565) transduced with either shCONT or SOX2 shRNA (shSOX2.52 or shSOX2.53).

Experiments were performed in two biological replicates with three technical repeats. Values represent mean ± SEM. **p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

To address the functional role of SOX2 in ZIKV infection, we targeted SOX2 expression using two non-overlapping short hairpin RNAs (designated shSOX2.52 and shSOX2.53) relative to a control short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence designed to avoid targeting any sequence in the mammalian genome (shCONT) (Figure S2G). Consistent with its role in GSC maintenance, targeting SOX2 expression induced expression of the differentiation marker GFAP (Figure S2G). GSCs transduced with shCONT retained their ability to be infected by ZIKV, as measured by both ZIKV-E protein and RNA, whereas GSCs transduced with shSOX2 showed attenuated ZIKV infectivity (Figures 2C–E). Although AXL is a putative ZIKV receptor (Nowakowski et al., 2016), we did not observe differential ZIKV infection following AXL knockdown, suggesting that AXL is dispensable for ZIKV infection of GSCs (Figures 2C, 2D, and S2H). Moreover, in GBM surgical specimens, the majority of AXL+ cells were GFAP+, not SOX2+, suggesting that SOX2 and AXL mark discrete tumor populations (Figures S2I and S2J).

SOX2 exerts many of its effects through transcriptional regulation of gene targets. To focus our efforts on mediators of ZIKV infection, we interrogated The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) GBM database for genes that correlated with SOX2 mRNA expression. SOX2 positively correlated with genes involved in nervous system development and neuronal structural components, whereas SOX2 negatively correlated with genes of the innate immune response and regulation (Figures 2F and 2G). Because suppression of cell-intrinsic innate immune responses can render cells susceptible to viral infection, we interrogated the relationship between SOX2 mRNA expression and mediators of the interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) family. SOX2 mRNA consistently negatively correlated with ISGs in GBM (Figures 2H, 2I, and S3A). Silencing SOX2 induced ISG expression, supporting SOX2 regulation of antiviral cellular responses (Figures 2J and S3B). To determine whether these changes in ISGs were biologically relevant, we examined ISG levels in GSCs treated with increasing concentrations of type I interferon (Figure S3C). The inverse relationship between SOX2 and ISGs in GSCs contrasts with normal stem cells, where ISGs are highly expressed (Wu et al., 2018), suggesting that SOX2 function differs between normal and neoplastic stem cells.

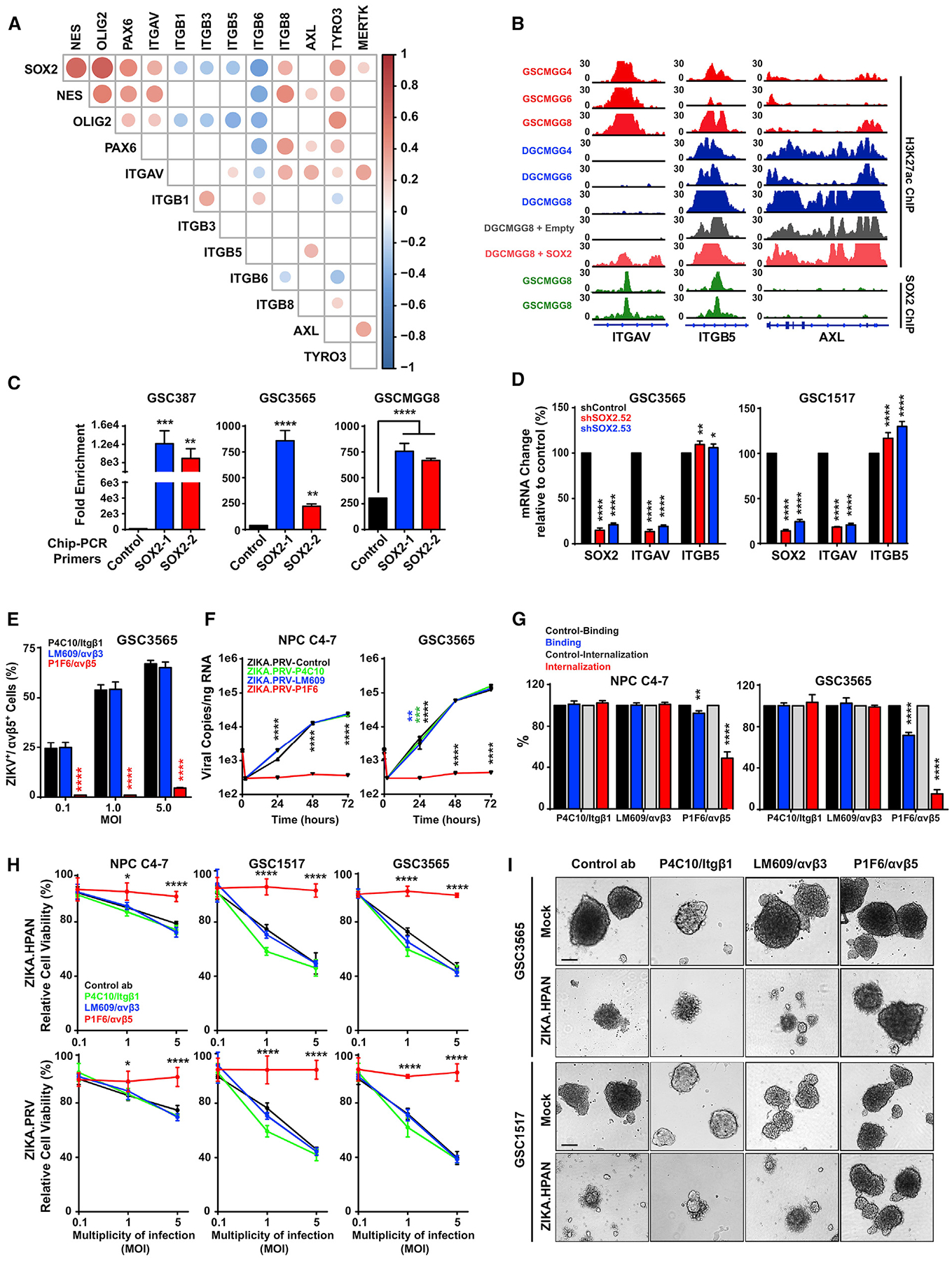

SOX2 Regulates Integrin αv Expression in GSCs

SOX2 suppression of the innate antiviral response provides one mechanism by which its expression correlates with ZIKV infection. We hypothesized that SOX2 also may regulate the expression of molecules involved in the primary infection process, based on the rapid decrease in ZIKV infection after SOX2 targeting, so we interrogated the TCGA GBM database for associations between SOX2 mRNA, expression of other GSC markers, and possible ZIKV receptors, including the TAM receptors (TYRO3, AXL, and MERTK) and several integrins, which may serve as attachment factors for West Nile virus and other flaviviruses (Chu and Ng, 2004; Meertens et al., 2017; Figure 3A). AXL and SOX2 expression were not correlated, whereas the mRNA levels of integrin αv (ITGAV) correlated with SOX2 and other GSC markers (NES, PAX6, and OLIG2) (Figures 3A and S4A). Because SOX2 is a transcription factor, we investigated SOX2 regulation of ITGAV. Measurement of active chromatin through histone 3 lysine 27 acetyl chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (H3K27ac ChIP-seq) of GSCs and DGCs revealed activation of the ITGAV locus in GSCs, whereas the AXL locus was more activated in DGCs (Suvà et al., 2014; Figure 3B); these data were consistent with the immunofluorescence staining of GBMs (Figure S2I). SOX2 bound within the ITGAV locus by ChIP-seq, and its binding was associated with an increase in the active chromatin mark H3K27ac at this locus (Figure 3B). ChIP-PCR of SOX2 on the ITGAV locus in a set of GSCs confirmed SOX2 binding (Figure 3C). Gene silencing of SOX2 using either of two non-overlapping shRNAs showed reduced ITGAV expression but not that of another integrin subunit, ITGB5, as measured by mRNA levels, immunohistochemistry, and immunoblotting (Figures 3D, S4B, and S4C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that SOX2 regulates ITGAV expression in GSCs.

Figure 3. SOX2 Regulates Integrin αv in GSCs, and Integrin αvβ5 Mediates ZIKV Infection in GSCs.

(A) Correlation between SOX2 mRNA expression with ITGAV, Nestin (NES), PAX6, OLIG2, ITGB1, ITGB3, ITGB5, ITGB6, ITGB8, AXL, TYRO3, and MERTK levels from the TCGA GBM HG-U133A microarray dataset. Size and color indicate the degree of correlation (p < 0.001), with blank cells indicating a non-significant correlation.

(B) ChIP-seq for H3K27ac or SOX2 at the ITGAV, ITGB5, and AXL loci in matched GSCs and DGCs and following SOX2 overexpression. Data were derived from GSE54792 and GSE17312.

(C) ChIP-PCR assessing SOX2 occupancy at the ITGAV locus with two distinct sequences (denoted SOX2–1 and SOX2–2) in three GSC lines (387, 3565, and MGG8).

(D) mRNA levels of SOX2, ITGAV, and ITGB5 by qPCR for GSCs (GSC3565 or GSC1517) transduced with either shCONT or SOX2 shRNA (shSOX2.52 or shSOX2.53). p values indicate comparisons with shCONT.

(E) GSCs (GSC3565) were cultured with an IgG control antibody (LM142) or one of three neutralizing antibodies against integrins (Itgβ1, 4C10; αvβ3, LM609; αvβ5, P1F6; 50 μg/mL) and then exposed to mock conditions or infection with ZIKV. The fraction of GBM integrin αvβ5+ cells was assessed by immunofluorescence 72 h p.i. with ZIKV.

(F) GSCs (GSC3565) or NPCs (C4–7) were cultured as in (E). The number of intracellular ZIKV viral particles was quantified by qRT-PCR.

(G) Quantification of viral RNA by qRT-PCR in (F) was performed to assess surface binding or internalization with normalization to the IgG control.

(H) GSCs (GSC3565) were cultured as in (E). Cell viability was assessed 72 h p.i. with ZIKV.

(I) Representative bright-field images of GSCs (GSC3565 and GSC1517) that were cultured as in (E). Scale bars, 50 μm.

Experiments were performed in two biological replicates with three technical repeats. Values represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

Blockade of αvβ5 Integrin Reduces ZIKV Infection in GSCs

The integrin αv subunit forms heterodimers with one of five different β subunits (β1, β3, β5, β6, or β8) to mediate its binding to matrix ligands and promote intracellular signaling, adhesion, cell migration, and cell proliferation (Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010). To determine whether any of the integrin heterodimers were involved in ZIKV infection, we screened a panel of function-blocking antibodies against different integrins—pan-β1 (P4C10), αvβ3 (LM609), and αvβ5 (P1F6)—for the capacity to prevent viral infection. Although blocking antibodies against β1 and αvβ3 integrins had limited effect on ZIKV infection of NPCs or GSCs, as measured by ZIKV-E staining (Figures 3E and S4D) or ZIKV RNA levels (Figure 3F), blockade of αvβ5 integrin substantially reduced viral infection (Figures 3E, 3F, and S4D–S4G). Although blocking antibodies against β1 and αvβ3 integrins did not alter surface binding or internalization of ZIKV to GSCs, a blocking antibody against integrin αvβ5 reduced ZIKV internalization to a greater extent than cell binding (Figure 3G). We assessed the effects of antibody blocking of integrins on ZIKV killing of NPCs and GSCs. With blocking antibodies against β1 or αvβ3 integrins, we observed similarly reduced cellular viability with increasing multiplicity of infection (MOI) compared with a control antibody (Figure 3H). In contrast, a blocking antibody against αvβ5 integrin attenuated ZIKV-mediated cell death in both NPCs and GSCs (Figures 3H, S4H, and S4I). The αvβ5 integrin-blocking antibody also attenuated ZIKV effects on sphere formation under serum-free conditions (Figure 3I).

Brain organoids are complex, three-dimensional structures that self-organize and provide models that share features with normal and neoplastic brain tissues (Drost and Clevers, 2018); they have proven useful for studying viral infections (Zhou et al., 2018), including ZIKV (Garcez et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2016). We recently reported GBM organoids as a system for investigating the basis of GBM heterogeneity (Hubert et al., 2016). GBM organoids grow over time, as measured by organoid diameter (Figures S4K and S4L). Supporting a functional importance for αvβ5 integrin in GBM growth, tumor organoids incubated with an integrin αvβ5-blocking antibody were static or reduced in size over time. In contrast, tumor organoids infected with ZIKV were obliterated, an effect that was lost upon treatment with the αvβ5 integrin-blocking antibody (Figures S4K and S4L).

To determine whether GBMs preferentially express specific integrins, we interrogated the TCGA GBM dataset, which revealed that αv and β1, β3, β5, and β8, but not β6 integrin subunits, were overexpressed in GBM relative to normal brain (Figure 4A). The preferential expression of these integrins suggested that they might contribute to the specificity of ZIKV infection, so we silenced expression of the β subunits known to associate with integrin αv (β1, β3, β5, β6, or β8) using two non-overlapping shRNAs each (Figure 4B). Only silencing of integrin β5 prevented killing of GSCs by ZIKV infection, as measured by cell viability (Figure 4C), sphere formation (Figure 4D), sphere size (Figure 4E), and ZIKV RNA copy number (Figure 4F). In complementary studies, we targeted ITGB3, ITGB5, and ITGAV using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing (Figure S5A), revealing that ZIKV infection required ITGAV and ITGB5 but not ITGB3 (Figure S5B). We previously demonstrated that integrin α6 (ITGA6) is a functional GSC marker (Lathia et al., 2010). Targeting ITGAV by CRISPR/Cas9 did not change ITGA6 levels (Figures S5C and S5D). Targeting ITGA6 by CRISPR/Cas9 reduced ITGA6 expression and the number of GSCs, consistent with our previous study (Figures S5E–S5G). Although ITGA6 single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and ZIKV infection both targeted GSCs (Figure S5G), GSCs surviving loss of ITGA6 were not infected by ZIKV at higher rates, and ZIKV infection did not specifically deplete ITGA6+ cells in surviving GSCs (Figures S5H and S5I), suggesting that ITGA6 is not essential for ZIKV infection of GSCs. Collectively, these results support a specific role for αvβ5 integrin in ZIKV infection and cellular killing.

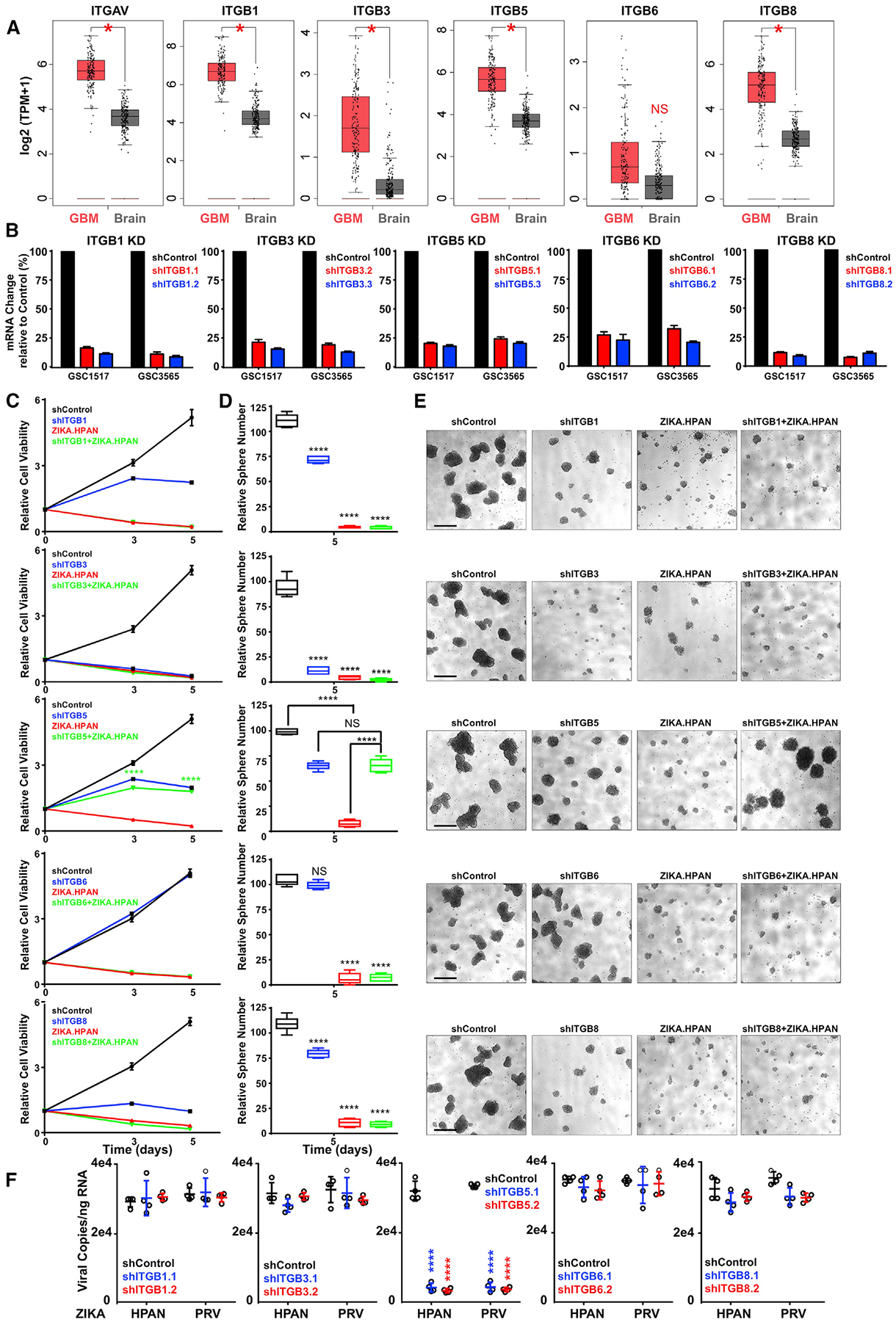

Figure 4. ZIKV Infection of GSCs Requires Integrin β5.

(A) Matched TCGA GBM and normal brain from the genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) dataset, showing the expression levels of selected integrins; log scale by Log2 (transcripts per million [TPM]+1). *p < 0.0001 (n = 163 samples for GBM, n = 207 samples for normal brain).

(B) mRNA expression of integrins following shRNA-mediated knockdown in two patient-derived GSCs (GSC1517 and GSC3565). Values were normalized to a non-targeting shCONT.

(C) Cell viability in GSC3565 on days 0, 3, and 5 following treatment with integrin-targeting shRNAs, ZIKV, or a combination.

(D) Quantification of the number of spheres formed by GSCs on day 5 following treatment with integrin-targeting shRNAs, ZIKV, or a combination.

(E) Representative images of spheres derived from GSC3565 (C and D). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(F) ZIKV infectivity assessed by qRT-PCR on patient-derived GSCs transduced with either shCONT or one of two non-overlapping shRNAs targeting integrin β subunits that paired with integrin αv.

Two biological replicates with three technical repeats were performed. Data presented as mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

αvβ5 Integrin Maintains GSCs

To interrogate the role of integrin αvβ5 in GSCs, we leveraged a panel of H3K27ac profiles that we developed from primary GBM resection specimens (Wang et al., 2017b) and compared these with normal brain H3K27ac profiles derived from the Roadmap Epigenomics database (Figure 5A). The loci for SOX2, ITGAV, and ITGB5 displayed more active chromatin states in GBM than non-neoplastic brain. AXL, in contrast, showed similar chromatin states between tumor and non-neoplastic tissues (Figure 5A). High ITGB5 mRNA levels were associated with a poor prognosis in IDH1 wild-type GBM patients, with a particularly poor prognosis for patients with high levels of both ITGAV and ITGB5 (Figure 5B). To further link SOX2 and αvβ5 integrin in GBM, we performed immunofluorescence for SOX2, αvβ5 integrin, and GFAP (a marker of differentiated cells) on surgical specimens from GBM and control brain tissue derived from epilepsy patients (Figure 5C). GBM tissues had more integrin avb5+ cells than non-neoplastic brain, and the majority of SOX2+, but not GFAP+, cells expressed αvβ5 integrin (Figure 5D). CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of ITGAV with two distinct sgRNAs (sgITGAV) in GSCs reduced integrin αvβ5 protein expression, as measured by immunofluorescence, but not SOX2 expression, supporting that ITGAV is downstream of SOX2 (Figure 5E). As expected, GSCs transduced with sgITGAV had reduced surface expression of αvβ5 integrin (Figure 5F). Targeting ITGAV attenuated GSC viability (Figure 5G) and self-renewal, as measured by limiting dilution sphere formation (Figures 5H and 5I). Immunocompromised mice bearing two different GSCs transduced with one of two sgITGAVs survived longer and had reduced tumor growth compared to a control sgRNA (sgCONT) (Figures 5J and 5K). These results demonstrate that the cells targeted by ZIKV and marked by ITGAV expression are critical to tumor growth.

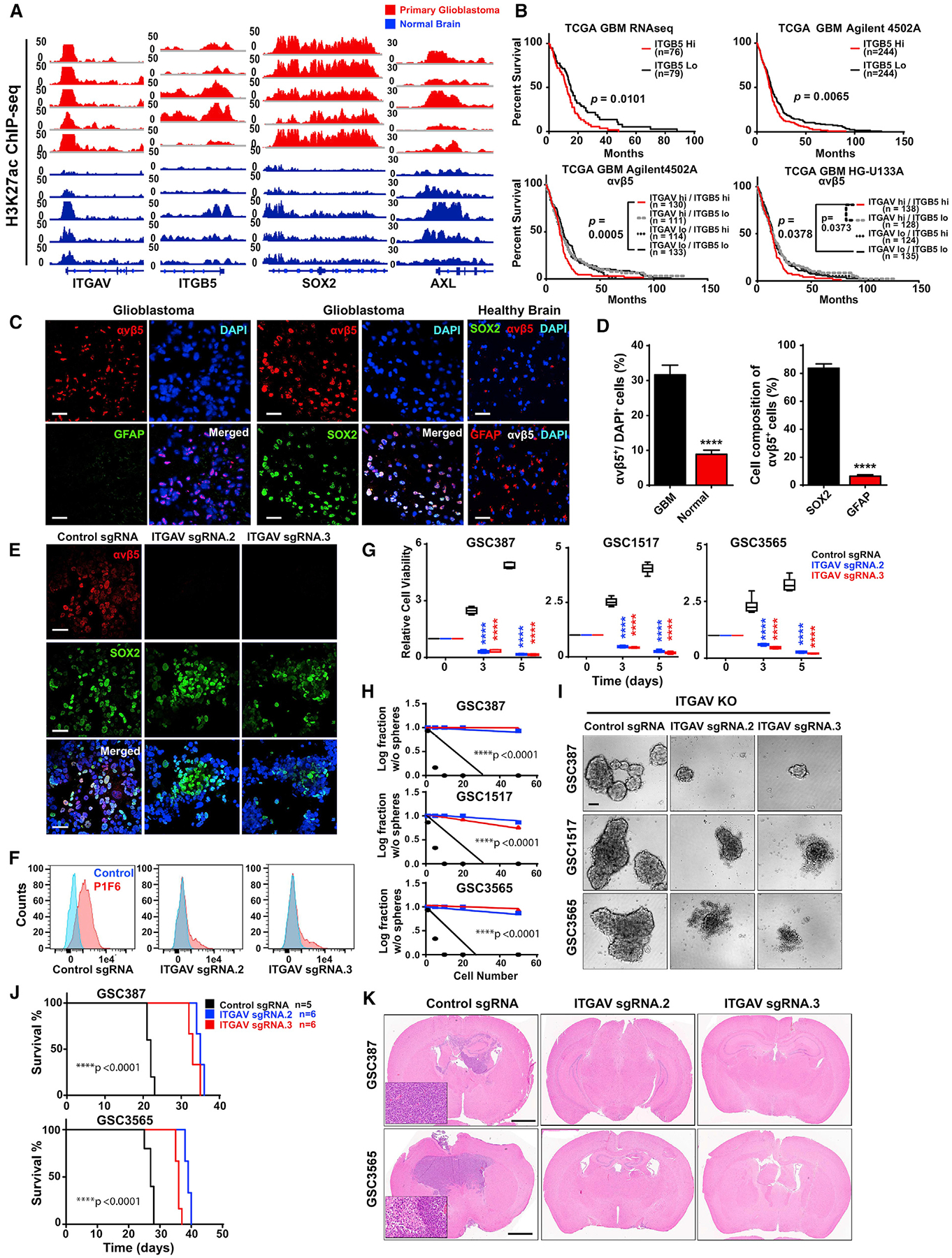

Figure 5. Integrin αvβ5 Maintains GSCs.

(A) H3K27ac ChIP-seq of primary GBM (red, n = 5 samples) and normal human brain (blue, n = 5 specimens) at the ITGAV, ITGB5, SOX2, and AXL loci.

(B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of patients from the TCGA database. Patients were categorized into a “high” or “low” expression group based on the median mRNA expression of ITGB5 and integrin αvβ5 in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the Agilent 4502 microarray, or the HG-U133A microarray. The p values were calculated by log rank test.

(C) Immunostaining for integrin αvβ5 (red), GFAP (green), SOX2 (green), and DAPI (blue) of primary human GBM surgical biopsy specimens (n = 3) or normal human brain (n = 2). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(D) (Left) The fraction of DAPI+ cells from Figure 4C that stained for integrin αvβ5. Right: the fraction of SOX2+ and GFAP+ cells in integrin αvβ5+ GSCs. Values represent mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(E) Representative immunostaining of GSCs (GSC3565) for integrin αvβ5 (red), SOX2 (green), and DAPI (blue) after transduction with either a sgCONT or one of two sgRNAs targeting ITGAV. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(F) Flow cytometry analysis for three patient-derived GSCs (GSC387, GSC1517, and GSC3565) transduced with either sgCONTor one of two sgRNAs targeting ITGAV following incubation with an IgG control antibody (LM142) or an integrin αvβ5 antibody (P1F6).

(G) Cell viability of three patient-derived GSCs (GSC387, GSC1517, and GSC3565) transduced with either sgCONT or one of two sgRNAs targeting ITGAVs normalized to day 0. Values represent mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

(H) Neurosphere formation of three patient-derived GSCs (GSC387, GSC1517, and GSC3565) transduced with either sgCONT or one of two sgRNAs targeting ITGAV. Values represent mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA).

(I) Representative bright-field images of (H) at 5 days. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(J) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for mice bearing GSCs (GSC387 and GSC3565) transduced with either sgCONT or one of two sgRNAs targeting ITGAV (sgCONT, n = 5; ITGAV sgRNA, n = 6). ****p < 0.0001 by log rank analysis.

(K) Representative H&E images from (J). Boxes show magnified sections. Scale bars, 50 μm.

ZIKV Induces Cellular Changes in Normal Mature Cerebral Organoids but Has Little Effect on Size

To avoid species differences between tumor and normal cells, we determined the relative effects of ZIKV infection on GBM and normal cerebral organoids. Mature brain cortical organoids (BCOs) from human pluripotent stem cells (Thomas et al., 2017; Trujillo et al., 2019) contain mature neurons from different layers (CTIP2, NeuN, SATB2, and MAP2+ cells) and neuronal progenitors (SOX2+) and glia (GFAP+) (Figures 6A and S6A). ZIKV had little effect on the size of BCOs over time (Figures 6B, 6C, and S6B), but there was an increase in apoptotic cells and decrease in SOX2+ cells (Figures 6D and 6E). ZIKV had little to no effect on the proportions of different neuronal and astrocytic cell types in cerebral organoids (Figures 6F–6I).

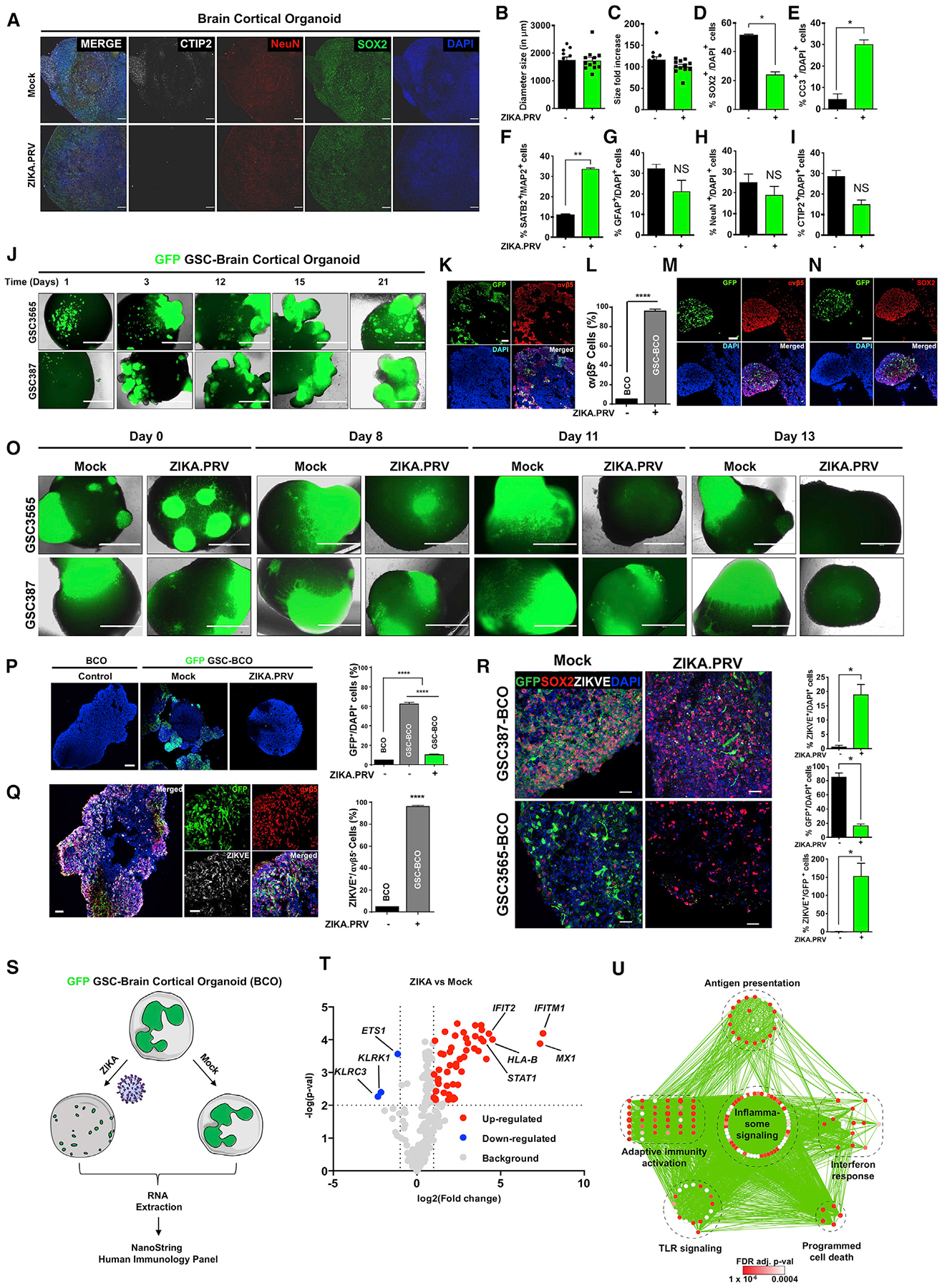

Figure 6. ZIKV Infection Preferentially Targets GBM in GBM-Brain Cortical Organoid (GSC-BCO) Models and Activates Viral Process and Type I IFN Signaling Pathways.

(A) Representative images of mock- or ZIKV-infected BCOs stained with neuronal markers (CTIP2 and NeuN), a neural progenitor cell marker (SOX2), and DAPI. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(B) Quantification of BCO size p.i. with ZIKV. Significance was assessed by two-tailed Student’s t test, and experiments were performed in two batches with 12 organoids per group per batch.

(C) BCO size fold change of ZIKV- and mock-treated groups over a period of 1 month.

(D) Quantification of SOX2+ cells in ZIKV- versus mock-infected groups. *p < 0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(E) Quantification of CC3+ cells in ZIKV- versus mock-infected groups. *p < 0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(F) Quantification of SATB2+ cells within MAP2+ cells in ZIKV- versus mock-infected groups. **p < 0.01 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(G) Quantification of GFAP+ cells in ZIKV- versus mock-infected groups. N.S., not significant by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(H) Quantification of NeuN+ cells in ZIKV- versus mock-infected groups. N.S., not significant by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(I) Quantification of CTIP2+ cells in ZIKV- versus mock-infected groups. N.S., not significant by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(J) Bright-field images of engraftment of two patient-derived GSCs (387 and 3565) transduced with GFP into human BCOs over a time course. Scale bars, 1 mm.

(K) Engrafted GSCs (GFP+) with normal BCO immunostained for integrin αvβ5 (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 200 μm.

(L) Quantification of integrin αvβ5+ cells in normal BCOs or GSC-BCOs. Values represent mean ± SEM. n = 6. ****p < 0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(M) Representative images of GFP-labeled GSC-BCOs immunostained for integrin αvβ5 (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(N) Representative images of GFP-labeled GSC-BCOs immunostained for SOX2 (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(O) Images of GFP-labeled GSC-GFP BCOs 13 days p.i. with ZIKV. Scale bars, 1 mm.

(P) Representative images of residual GSCs (green) and DAPI staining (blue) of GFP-labeled GSC-GFP BCOs cultured under mock conditions or with ZIKV for 2–4 weeks. Scale bars, 200 μm. The percentage of GFP+ cells among DAPI+ cells was quantified. Values represent mean ± SEM. n = 6. ****p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA.

(Q) Representative immunostaining for integrin αvβ5 (red), GFP (green), ZIKV-E (white), and DAPI (blue) of GFP-labeled GSC-GFP BCOs mock- or ZIKV-infected for 2–4 weeks. Scale bars, 200 μm (left) and 100 μm (center). The percentage of ZIKV-E+ cells among integrin αvβ5 cells was quantified. Values represent mean ± SEM. n = 6. ****p < 0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(R) Representative images of 387 and 3565 GSC-BCOs with or without ZIKV, respectively, stained with SOX2, ZIKV-E, and DAPI. GFP shows the presence of GSCs (scale bars, 50 μm). ZIKV-E+, GFP+, and ZIKV-E+ cells among GFP+ cells were quantified by counting (two GSCs cell lines, two repeats, n = 12 organoids/group); *p < 0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(S) Schematic of the experiment design.

(T) Volcano plot showing differences between GSC-BCO ZIKV versus GSC-BCO mock. 113 genes were differentially expressed (greater than 1.5-fold) between these two groups (*p < 0.05).

(U) Network analysis of genes differentially expressed upon ZIKV infection, represented as a bubble plot.

Generation of Human GBM-Cerebral Organoid Models

To test the relative efficacy of ZIKV infection against human GBM relative to toxicity to normal human brain, we implanted human GBM tumors grown in mature (6-month-old) human BCOs. After 6 months, most NPCs differentiated into neurons and astrocytes (Thomas et al., 2017; Trujillo et al., 2019). Mimicking tumor growth, the GFP-GSCs invaded the BCOs and expanded over time (Figure 6J). The cerebral organoids alone without GSCs displayed substantially lower expression of αvβ5 integrin than the GBM organoids (Figures 6K and 6L). The GFP-GSCs preferentially expressed SOX2 and αvβ5 integrin relative to normal BCO cells (Figures 6M and 6N). These results demonstrate that fused GSC-BCOs preserve the differential expression profiles found in human tumors and normal brain and offer a platform to study human GBM.

ZIKV Infection Preferentially Targets GSCs in GBM-BCOs

ZIKV infection of GBM-BCOs preferentially reduced GFP-GSCs (Figure 6O) and infected αvβ5 integrin+ cells in combined GBM-BCOs, reducing the number of GFP-labeled tumor cells (Figures 6P and 6Q). In 2 patient-derived GSCs fused with human BCOs, ZIKV showed a potent anti-tumor effect over time (Figures S7A and S7B). We followed the number of GFP-GSCs by measuring the integrated density of GFP+ cells (Figures S7A and S7B) and immunostaining of GFP+ cells (Figures 6R and S7C); this showed preferential infection of GSCs by ZIKV and reduced cell numbers. Upon ZIKV infection, GFP-GSC-BCOs had an increased number of ZIKV-E+ cells that were mainly seen in GFP+ cells (Figures 6R and S7C). To rule out a contribution of GFP to the increased vulnerability of GFP-labeled GSCs to ZIKV infection, we generated GFP-BCOs by transducing iPSCs with a phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter-driven GFP lentivirus and then infected them with ZIKV (Figure S7D). ZIKV decreased the fraction of GFP+ cells in GFP-GSC-BCOs, concomitant with GSC apoptosis (Figure S7E), but not the number of GFP+ cells in GFP-BCOs (Figure S7F), confirming that GSC vulnerability to ZIKV in GSC-BCOs is not due to the presence of GFP. Given the regulation of ISGs by SOX2 in cell culture, we interrogated our GBM-BCOs for immune responses after infection with ZIKV by performing targeted RNA sequencing using a Nanostring panel of 770 immune-related genes (Figure 6S). Upon infection with ZIKV, 113 genes were differentially expressed, including increased expression of several ISGs as well as inflammasome, adaptive immunity, antigen presentation, interferon (IFN) response, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways (Figure 6T and 6U), suggesting that organoids induce an immune response associated with elimination of GSCs by the virus. Collectively, these results confirm that ZIKV has oncolytic activity against GSCs and that this is associated with preferential expression of αvβ5 integrin in a fully humanized model system.

ZIKV Does Not Induce Malignant Transformation in Normal Brain but Targets GSCs In Vivo

To address the potential for ZIKV induction of malignancy in vivo, we tested its toxicity on NPCs and the potential for oncogenic transformation of normal NPCs using 4- to 6-week-old immunocompromised mice (non-obese diabetic [NOD].Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJl [NSG]). ZIKV (103 focus-forming units [FFU]/mouse of either the Human Panama [HPAN] or Puerto Rican isolate of ZIKV [PRVABC-59] [PRV] strains) was inoculated directly into the subventricular zone (SVZ). 72 h later, ZIKV infection of murine NPCs in the SVZ was confirmed through co-localization of ZIKV-E with the NPC marker SOX2 and αvβ5 integrin staining (Figures 7A and 7B). One month after ZIKV inoculation, the immunocompromised mice reached endpoint criteria (neurological signs), likely because of ZIKV virulence (Figure 7C). Analysis of ZIKV-infected brains revealed no gross morphological changes or evidence of malignancy (Figure 7D). These findings suggest that ZIKV induces neural toxicity in vivo in NSG mice but does not cause oncogenic transformation.

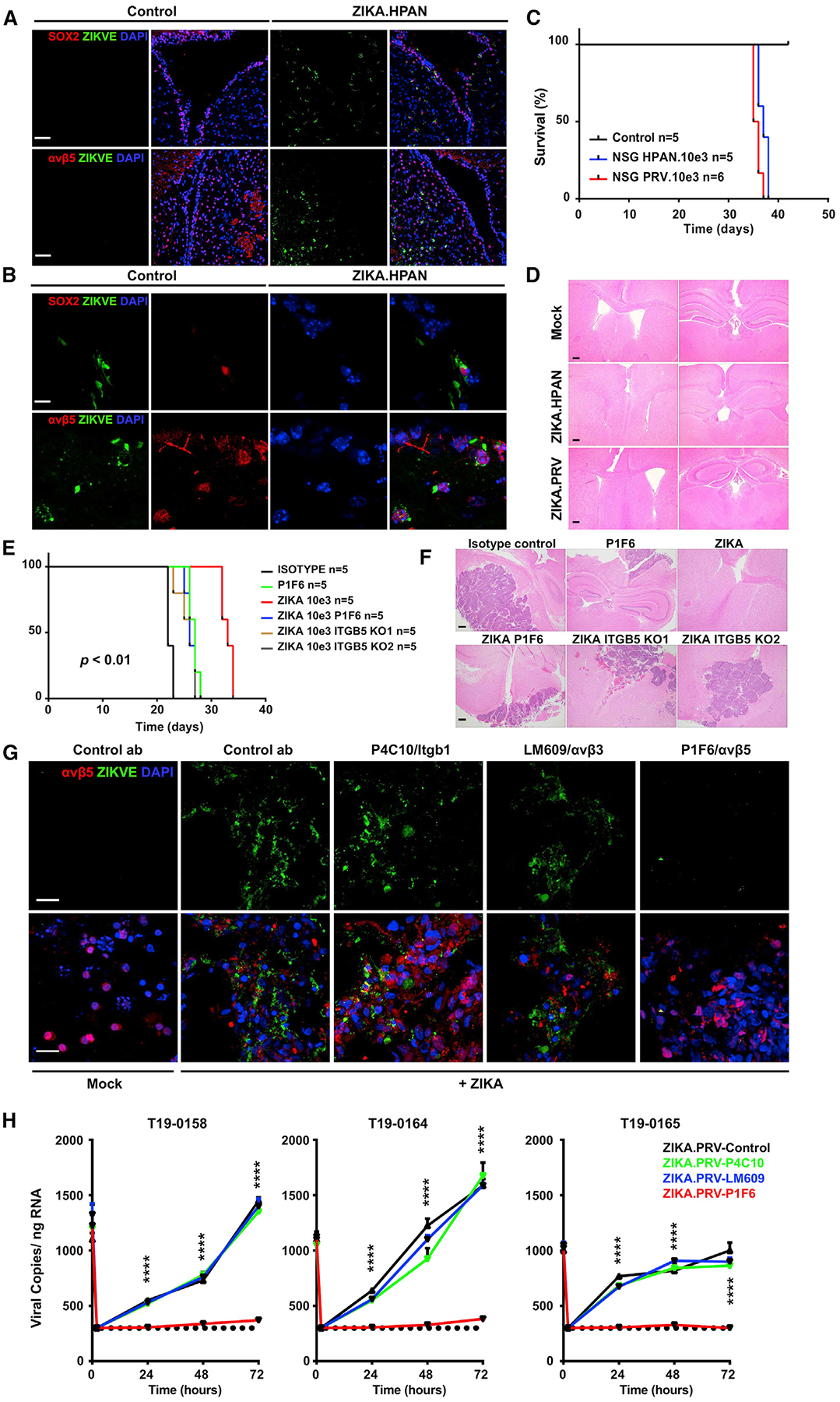

Figure 7. Integrin αvβ5 Mediates In Vivo ZIKV Targeting of GSCs in Mouse Models and in Human GBM.

(A) Immunostaining of the subventricular zone (SVZ) of mice 72 h following ZIKV infection ZIKV-E (green), SOX2 (red, top panels), and integrin αvβ5 (red, bottom panels). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(B) Higher magnification of images from (A), demonstrating ZIKV infection of SOX2+ (top panels) and integrin αvβ5+ cells. Scale bars, 10 μm.

(C) Survival of ZIKV-infected NSG mice from (A) was plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method.

(D) ZIKV-infected brains from the mice in (A) were collected upon death, and histology was assessed by H&E staining. Scale bars, 20 μm.

(E) Survival of NSG mice following implantation of GSCs treated with isotype control, P1F6 antibody, ZIKV, combined P1F6 and ZIKV, combined CRISPR knockout (KO) of integrin β5 (sgRNA1 sgRNA2) with ZIKV inoculation, analyzed by log rank test; p < 0.01.

(F) H&E staining of tumor-bearing brains from (E). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(G) Intraoperative brain slices from GBM patients were pre-incubated with an IgG control antibody or an integrin-blocking antibody under mock conditions or upon ZIKV infection (10e3 FFU). Slices then underwent immunofluorescence staining for ZIKV-E (green), integrin αvβ5 (red), and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

(H) Intraoperative brain slices from GBM patients were pre-incubated with an IgG control antibody or an integrin-blocking antibody under mock conditions or upon ZIKV infection. Slices then underwent a viral RNA copy assay by qRT-PCR. Experiments were performed in two biological replicates with three technical repeats. Values represent mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

Previous reports from our laboratory and others have shown that ZIKV kills GSCs in vivo (Zhu et al., 2017; Kaid et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018b). To assess the role of αvβ5 integrin in ZIKV-dependent oncolytic activity against GSCs in vivo, we used a tumor transplantation model in NSG mice and two complementary techniques: pharmacological inhibition with an integrin αvβ5-blocking antibody and genetic targeting of integrin β5 expression using CRISPR/Cas9-based techniques. GSCs treated with an immunoglobulin G (IgG) control antibody had the shortest survival, whereas treatment with ZIKV extended the survival of tumor-bearing hosts (Figures 7E and 7F). Treatment of GSCs with an antibody targeting αvβ5 or gene editing of ITGB5 in the tumor attenuated Zika-mediated cytotoxicity and reduced host survival (Figures 7E and 7F). However, treatment with the αvβ5 integrin-blocking antibody extended the survival of tumor-bearing hosts in the absence of ZIKV treatment, which is consistent with the independent role of αvβ5 integrin in GSC maintenance. Collectively, these results support a role of integrin αvβ5 in ZIKV-dependent targeting of GSCs in vivo.

Blocking αvβ5 Integrin Inhibits ZIKV Infection in Patient-Derived Tissues

Finally, to rule out possible effects of culture of tumors, we infected fresh intraoperative patient-derived GBM slices with ZIKV. To establish this model, we obtained freshly isolated primary human GBM slices and then incubated them with either an IgG control antibody or blocking integrin antibodies and infected them with ZIKV. Attenuation of ZIKV infection by αvβ5 integrin blockade was confirmed by staining for the ZIKV-E protein (Figure 7G) and quantifying the levels of ZIKV RNA (Figure 7H). These data support a dependence of αvβ5 integrin on ZIKV infection of GBM.

DISCUSSION

Identification of molecular mediators of viral infection is important for antiviral and oncolytic virus strategies (Medigeshi et al., 2008; Brinton, 2013). Enrichment strategies for effective oncolytic therapy trials now include testing for expression of key determinants of viral infection in tumor tissues prior to patient enrollment. Here we demonstrate that SOX2 and integrin αvβ5 mark GSCs that are preferentially targeted by ZIKV in association with suppression of immune response genes and a molecular complex involved in viral internalization. αv integrins are a particularly attractive set of targets for several reasons. These integrins are often expressed at low levels in normal tissues, with induction upon stress environments found in tumors (Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010). Further, integrins can be modulated with acceptable toxicity through neutralizing antibodies or small molecules. More than two decades ago, these integrins were linked to adenovirus infection (Wickham et al., 1993). More recently, selected integrins have been associated with viral infection of other viruses in the flavivirus family, albeit with differential results based on assay (Schmidt et al., 2013; Fan et al., 2017). αv integrins have been linked to cancer stem cells; integrin αvβ3 is expressed in epithelial cancer stem cells, where it serves as a driver of tumor initiation and drug resistance (Seguin et al., 2014, 2017). In GBM, αvβ3 expression inhibits senescence (Poirot et al., 2015) and facilitates glucose uptake by promoting upregulation of the high-affinity glucose transporter Glut3 (Cosset et al., 2017). ZIKV infection was not inhibited by shRNAs or sgRNAs against ITGB3 or LM609, a highly selective antibody antagonist of αvβ3. Instead, our results suggest that a specific integrin heterodimer, αvβ5, closely related to αvβ3, is required for optimal ZIKV infection in GSCs. Although αv integrin also is expressed by NPCs, expression of the β5 integrin subunit is more selective to GBM, both stem-like and differentiated tumor cells. Therefore, GSCs display preferential sensitivity to ZIKV based on one integrin that is linked to a stem-like state and its partner, which is linked to a neoplastic state.

Our studies suggest an additional molecular mechanism mediating the effects of ZIKV against GSCs: downregulation of the antiviral immune response by SOX2, a core regulator of GSCs. These results stand in contrast to high expression levels of several ISGs in embryonic stem cells and more restricted ISG expression in neural stem cells, which have high levels of SOX2 expression (Wu et al., 2018). The divergent results between GSCs and normal stem cells suggest that SOX2 transcriptional control of ISGs is likely defined by other levels of control, including co-binding of other transcription factors and differential chromatin states. Comparison of the chromatin landscapes of GSCs and NPCs revealed that GSCs have greater activation of chromatin across the genome, which can alter transcriptional regulation (Mack et al., 2019). To further consider the role of immune responses in GSCs upon ZIKV infection, we interrogated transcriptional regulation of immunological modulators of GSCs grown in organoids with normal brains, which demonstrated upregulation of genes in the inflammasome, adaptive immune responses, TLR signaling, and IFN responses. Although SOX2 does not solely determine GSC response to ZIKV, GSCs appear to be less immunogenic than DGCs, offering a potential advantage in sustained tumor growth in the inflammatory environment found in GBMs. This immune phenotype may offer a potential selection factor.

Here we extend the recent description of GBM-BCO systems by another group (Ogawa et al., 2018). We leveraged the system to model the growth patterns of patient-derived models and test the efficacy of antitumor therapies. This system is particularly valuable for measuring the direct therapeutic index of therapies, such as oncolytic viruses, that must provide substantial anti-tumor activity while minimizing toxicity against normal tissues, like the brain. Because some viral infections display strong species specificity, the use of human GBMs in organoids of normal human brain may empower greater relevance of selective tumor targeting in preclinical studies. Further, we employed genetic and pharmacologic targeting strategies that can be leveraged to dissect the determinants of tumor response to oncolytic viral therapies.

Although direct application of wild-type ZIKV as an oncolytic virus in GBM would likely be challenging, we and others have already reported that genetically attenuating modifications to ZIKV strains may offer reduced toxicity against normal tissues (Zhu et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018b). Identification of SOX2-associated downregulation of the innate antiviral immune response that distinguishes normal and neoplastic stem cells and of integrin αvβ5 as an important molecular feature mediating infection may prioritize selection of genetically modified ZIKV for use in patients to augment efficacy against the most resistant and aggressive GBMs cells while minimizing virus-induced disease.

STAR⋆METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

All data will be provided to reviewers and/or editors upon request. There are no restrictions on data availability. Further information and requests should be addressed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jeremy Rich (drjeremyrich@gmail.com).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Ethical Compliance Statement

For intracranial tumor models, NSG (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJl, #005557, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) mice were used under the University of California, San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved protocol. All experiments conformed to the ethical and humane standards for animal treatment as defined by our protocol. Animals were monitored daily and were humanely sacrificed upon the appearance of any neurological signs.

Culture of GSCs, DGCs, and nonmalignant brain cultures

Glioblastoma tissues were obtained from excess surgical materials from patients at the Cleveland Clinic after neuropathology review with appropriate consent, in accordance with an IRB-approved protocol. To prevent culture-induced drift, patient-derived xenografts were generated and maintained as a recurrent source of tumor cells for study (Wang et al., 2017a). To prevent culture-induced drift in GBM models, patient-derived subcutaneous xenografts were generated in NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJl mice (#005557, Jackson Laboratory) and maintained as a recurrent source of tumor cells for study. Upon xenograft removal, a papain dissociation system (Worthington Biochemical) was used to dissociate tumors according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then cultured in Neurobasal complete media (Neurobasal medium; Life Technologies) supplemented with 1 × B27 without vitamin A (Thermofisher), 2 mM l-glutamine (Thermofisher), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Thermofisher), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; R&D Systems). The GSCs phenotype was validated by OLIG2 and SOX2 expression, functional assays of self-renewal (serial neurosphere passage), and tumor propagation using in vivo limiting dilution. All cells were incubated at 37°C in humidified incubators supplemented with 5% CO2 and tested to ensure that they were negative for mycoplasma. See also Table S1 for GSCs lines.

Proliferation and neurosphere formation assay

Cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All data were normalized to day 0, prior to infection with ZIKV, and expressed as a relative cell number. Neurosphere formation was measured as previously described (Wang et al., 2017b, 2018). Briefly, decreasing numbers of cells per well (50, 20, 10, 5, and 1) were plated into 96-well plates. Seven days after plating, the presence and number of neurospheres in each well were recorded. Extreme limiting dilution (ELDA) analysis was performed using software available at http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda (Wang et al., 2017a, 2018).

Brightfield images

GFP-GSC, GSCs and BCOs images were acquired on an EVOS cell imaging microscope (Thermofisher). Images were acquired using an ImageXpress Micro automated microscope (Molecular Devices) and exported using MetaXpress 5.3 (Molecular Devices).

Immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and microscopy

Ten μm-thick cryosections were air-dried and fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes before being washed twice with PBS. Tissues were permeabilized by incubating the slides with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. After blocking for 1 hour at room temperature in a blocking buffer containing 0.25% Triton X-100, 2.5% BSA in 1 × PBS, slides were incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C with primary antibodies for ZIKV (Millipore; AB10216; working dilution 1:1,000), SOX2 (Millipore; AB5603; stock: 1 mg/ml; working dilution 1:400), GFAP (Invitrogen, PA5–18598; working dilution 1:1,000), AXL (Abcam; AB32828; stock: 1 mg/ ml; working dilution 1:200), TUBB3 (Thermofisher; MA1–118; working dilution 1:500) and MAP2 (Abcam; ab5392, working dilution 1:2000). After 1xPBS washes, slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–, 594–, or 647–conjugated anti–mouse, anti–rat, anti-goat, or anti–rabbit secondary antibodies (Thermofisher, working dilution 1:1000). Slides were subsequently washed and mounted using VECTASHIELD with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). For immunocytochemistry stainings, 105 cells were seeded into a 12-well chamber slide (Thermofisher) and cultured overnight. Slides were then processed as described previously for tissue staining. 10 ×, 20 ×, and 40 × images were collected at room temperature on Zeiss Apotome microscope. The cells were identified based on DAPI. Image analysis was performed by thresholding for positive staining and normalizing to total tissue area using ImageJ and Zen (Zeiss) software. Quantification was performed in a blinded manner to eliminate bias.

EdU labeling and imaging

The EdU labeling was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermofisher). Briefly, cells were plated on coverslips and allowed to recover overnight. A final concentration of 10 μM EdU was added (Click-iT EdU imaging Kit, molecular probes). The cells were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After incubation, the media was removed and 0.5 mL of 3.7% paraformaldehyde was added in PBS to each well containing the coverslips. The cells were then incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. The paraformaldehyde was removed, and the cells were washed twice with 1 mL of 3% BSA in PBS. The wash solution was then removed and 1 mL of 0.5% Triton® X-100 in PBS (permeabilization buffer) was added to each well, then incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. The permeabilization buffer was then removed, the cells were washed twice with 1 mL of 3% BSA in PBS. Finally, 0.5 mL of Click-iT® reaction cocktail was added to each well containing a coverslip. The plate was briefly rocked to ensure that the reaction cocktail was distributed evenly over the coverslip for 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light. After 30 minutes, the reaction cocktail was removed, cells were washed once with 1 mL of 3% BSA in PBS before proceeding to DNA staining (DAPI, Vector Laboratories H-1200) and imaging (Zeiss Apotome).

ZIKV preparation

ZIKV human isolates H/PAN/2016/BEI-259634 and PRVABC59 (BEI Resources, NR-50210 and NR-50240) from Panama and Puerto Rico, respectively, were acquired from the ATCC and distributed by BEI. Viruses were amplified in Vero cells, totaling 2–3 serial passages of the original viral stock. Infected cell supernatants were concentrated through a 30% sucrose cushion, and re-suspended in neural maintenance medium base (50% DMEM/F12 Glutamax, 50% Neurobasal medium, 1x N2 Supplement, 1x B27 Supplement all from Life Technologies) supplemented with 1% DMSO and 5% FBS and stored at −80°C. Viral stock titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells and were greater or equal to 2 × 108 plaque forming units/ml. Mock media was prepared by concentrating uninfected Vero cell supernatant as above.

ZIKV titration

Viral titers (plaque forming units (FFU)/mL) were calculated by plaque-forming assays on Vero cells. Vero cells were seeded at a density of 7.5 × 104 cells per well in standard 24-well plates and incubated at 5% CO2, 37°C for 48 hours before infection. Serial dilutions of supernatants were collected from ZIKV-infected NPCs and GSCs after infection with ZIKV at MOI of 0.1 FFU/cell, and then added to Vero cells for 1 hour. Cells were covered with an agarose overlay and further incubated for 72 hours. 3.7% paraformaldehyde was added on top of overlays for 24 hours to fix monolayers, overlays were removed, and cell monolayers were stained with crystal violet to visualize plaques.

In vitro viral infection

GSCs were plated at 5,000 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture plates and allowed to attach overnight. For viral infection and growth inhibition assays, ZIKA.HPAN and ZIKA.PRV at a range of MOI 0.1, 1, and 5 FFU/cell.

Zika viral RNA quantification

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using primers, probes, RNA standards, and conditions described previously (Boonnak et al., 2008). Briefly, Viral RNA was extracted from cell culture using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). ZIKV RNAs were detected using TaqMan® Universal Master Mix II, no UNG (Thermofisher). The samples were carried out in 20 μL reactions and the run method was as follows: 10 minutes at 95°C, 42 cycles of 15 s at 95°C followed by 1 minute at 58°C. The sensitivity of the ZIKV real-time assays was evaluated by titration of serial dilution of virus with a previously known titer. GraphPad Prism was used as fitting software. See also Table S2 for the ZIKV primers.

Binding and internalization assay

To measure ZIKV cell surface binding/adsorption, the GSCs and hNPCs incubated with indicated integrin receptor neutralizing antibodies at 50 mg/ml for 1 hour at 4°C, were exposed to ZIKV at a MOI of 5 FFU/cell, along with serum-only and media-only controls for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were washed three times at 4°C with 10 mL PBS containing 10% BSA. The number of viruses that bound to the cells was determined by qRT-PCR. To measure ZIKV immune complex internalization, cells were exposed to ZIKV at MOI of 5 FFU/cell. The cells were washed three times with 10 mL PBS and resuspended with PBS containing 10% BSA. The cells were treated with 5 mg/ml of Pronase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) to remove excess virus on the cell surface. The number of internalized viruses was determined by qRT-PCR (Boonnak et al., 2008).

Lentiviral shRNA transfection

shRNA sequences were selected from the Mission 2.0 library (Sigma-Aldrich). Plasmids were transformed and amplified in Dh5α competent E. coli and purified using EndoFree Plasmid mini kit (Omega, #D6948). For lentivirus preparation, 293T cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with shRNA against SOX2, AXL vectors and Mission Lentiviral Packaging Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, #SHP001) using JetPrime transfection reagent (Polyplus, #89129–926). After 24 hours, growth media was changed to Neurobasal media and after 48 hours, supernatants were collected and GSCs were infected. After 48 hours of infection, GSCs were trypsinized and reseeded on a 96-well plate for subsequent ZIKV infection. In parallel, total RNA was extracted using Quick-RNA MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo Research, #R1055). 500 ng of RNA was used to synthesize complementary DNA using qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quanta, #101414–106). Samples were diluted tenfold and gene expression was analyzed by a CFX96 Touch Detection System (Bio-Rad) using FastStart SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche). See also Table S2 for shRNA sequences and primer pairs.

Quantitative PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by RT into cDNA using the qScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Quanta BioSciences). Real-time PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500HT cycler using Taq-Man Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermofisher Scientific). See also Table S2 for primer pairs sequences.

NanoString nCounter Gene Expression

Total RNA was extracted from mock or ZIKV-infected GSC-brain cortical organoids using QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Plus kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. 50ng of total RNA was then processed with the NanoString nCounter system (NanoString, Seattle, Washington, USA) per vendor instructions with Human Immunology Panel. Data export and normalization were performed using nSolver software (NanoString). Data was further analyzed using Rosalind On Ramp software.

Rosalind NanoString analysis methods

Data was analyzed by Rosalind (https://rosalind.onramp.bio/), with a HyperScale architecture developed by OnRamp BioInformatics, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Read Distribution percentages, violin plots, identity heatmaps, and sample MDS plots were generated as part of the QC step. The limma R library (Ritchie et al., 2015) was used to calculate fold changes and p values. Clustering of genes for the final heatmap of differentially expressed genes was done using the PAM (Partitioning Around Medoids) method using the fpc R library that takes into consideration of the direction and type of all signals on a pathway, the position, role and type of every gene, etc. Functional enrichment analysis of pathways, gene ontology, domain structure and other ontologies was performed using HOMER (Heinz et al., 2010). Several database sources were referenced for enrichment analysis, including Interpro (Mitchell et al., 2019), NCBI (Geer et al., 2010), KEGG6 (Kanehisa et al., 2017, 2019), MSigDB (Subramanian et al., 2005; Liberzon et al., 2011), REACTOME (Fabregat et al., 2018), WikiPathways (Slenter et al., 2018). Enrichment was calculated relative to a set of background genes relevant for the experiment. Additional gene enrichment is available from the following partner institutions: Advaita (http://advaitabio.com/ipathwayguide/; Draghici et al., 2007; Donato et al., 2013).

Western blotting

Cells were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mmol/L NaCl; 0.5% NP-40; 50 mmol/L NaF with protease inhibitors) and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes, and supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Equal amounts of protein samples were mixed with SDS Laemmli loading buffer, boiled and electrophoresed using NuPAGE Bis-Tris Gels (Life Technologies), and then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). Blocking was performed for 45 minutes using TBS-T supplemented with 5% nonfat dry milk and blotting performed with primary antibodies at 4°C for 16 hours. Primary antibodies used were SOX2 antibody (R&D, #AF2018), OLIG2 antibody (Millipore, #MABN50), GFAP antibody (BD, #BDB610565), β-Actin antibody (Cell signaling, #4970), Integrin alpha V antibody (Abcam, ab124968), Integrin β5 antibody (R&D, AF3824), Integrin β3 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, SAB4501586), Integrin alpha 6 antibody (Abcam, ab181551), Cleaved Caspase-3 antibody (Cell signaling, #9664) and GAPDH antibody (Abcam, ab9484).

In silico analysis

mRNA data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) GBM HG-U133A microarray dataset using the GlioVis web portal (Bowman et al., 2017). Expression of each gene was correlated with expression of SOX2. A “SOX2 positively correlated” gene set was defined by selecting genes with an r > 0.4 and the “SOX2 negatively correlated” gene set was defined by selecting genes with an r < −0.4. Gene sets were inputted into the Broad Institute online Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Tool (Mootha et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2005) (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). The top enrichment pathways were visualized using a bar graph showing the −Log10 of FDR corrected p value for the pathway enrichment. Gene set enrichment bubble plots were generated using the Bader Lab Enrichment Map (Merico et al., 2010) in cytoscape. Bubbles represent single gene sets that are enriched with lines demonstrating overlapping genes between enriched pathways. The borders of the circles represent the FDR corrected p value for each pathway.

ChIP-Seq and ChIP-PCR

Cells (5 × 106) per condition were collected, and 5 mg SOX2 antibody (R&D Systems, #AF2018-SP) or goat-IgG (R&D Systems, #AB-108-C) was used for the immunoprecipitation of the DNA protein immunocomplexes. ChIP was performed using the Millipore Magna ChIP (MAGNA0017) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. See also Table S3 for the purified DNA qPCR primer sets.

Three technical replicates were performed with SOX2 ChIP-PCR data presented as fold change relative to the non-specific antibody (goat-IgG). Stem and differentiated glioma cell ChIP-seq data were downloaded from GEO using accession number GSE54047. GBM primary tissue ChIP-seq data was accessed from GSE101148. Normal Brain primary tissue ChIP-seq data was accessed through the publicly available Roadmap Epigenomics (http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/) and Encode Project web portals (https://www.encodeproject.org/). Data were viewed using IGV (http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/).

Flow cytometry

Cell pellets were washed with PBS and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature and stained with anti-αvβ5 antibody (Millipore, #MAB1961, 5 μg/mL in 1% BSA in PBS) and a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (Thermofisher, #A21235, 1:1000). After the staining, the cells were incubated with PI (Sigma-Aldrich, #P4864, 1:1000), and flow cytometry was performed on BD LSRFortessa™. The levels of αvβ5 integrin were analyzed using the flow cytometry analysis program FlowJo (FlowJo, LLC).

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was assessed using the Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit with Annexin V Alexa Fluor 488 from Thermofisher (#V13241) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were analyzed using flow cytometry on a BD LSR Fortessa Flow Cytometer.

CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA and cloning

The CRISPR design tool from the Broad Institute (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/analysis-tools/sgrna-design) was used to design the guide RNA (gRNA). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Thermofisher and were annealed and cloned into LentiCRISPR v2 plasmid, which was a gift from F. Zhang (Addgene plasmid 52961). 293FT cells were used to generate lentiviral particles through co-transfection of the packaging vectors pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr and pCI-VSVG using a standard calcium phosphate transfection method in Neurobasal complete media.

For knockout studies, GSC3565 cells were transduced with a CRISPR-Cas9 construct targeting integrins or a non-targeting control and selected for integration of the lentiviral construct by puromycin. Single cells were expanded in vitro to obtain clonal populations and knockout was confirmed by immunostaining and western blotting. Two clonal populations per sgRNA were subjected to parallel in vitro proliferation assays and in vivo survival assays. For in vitro studies, cells were plated in 96-well plates on Matrigel as above and maintained in standard serum-free media. For in vivo studies, cells were intracranially implanted into age-matched female NSG mice. Between five and six mice where used for each sgRNA construct. All mice were monitored daily until development of neurological signs, at which time they were euthanized, as described previously (Wang et al., 2018). See also Table S4 for the gRNA oligonucleotide sequences.

ZIKV in vivo inoculation experiments

The 4–6 weeks old female NSG mice (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJl, #005557) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Laboratory Animal Center (Washington University, IACUC-20170066). For the ZIKV transformed NPCs in vivo study, NSG mice were inoculated intracranially with 103 FFU of ZIKA.HPAN or PRV at subventricular zone (SVZ). PBS injection was used as a control. For the tumor implantation survival study, groups of NSG mice were inoculated intracranially with 104 GSC3565. For P1F6 treatment, GSC3565 were incubated with αvβ5 antibody at 50 μg/ml for an hour in cold PBS. For ZIKV inoculation, 103 FFU of ZIKA.HPAN or PRV was mixed with GSCs before implantation in vivo. PBS injection was used as a control.

Histology

10 μm-thick sections of paraffin-embedded tissues were analyzed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Thermofisher), Picro-Sirius Red (Sigma-Aldrich), and Masson’s Trichrome (Diagnostic Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 4 ×, 10 ×, and 20 × images were captured by AT2 Aperio Scan Scope. Image analysis was performed by thresholding for positive staining and normalizing to total tissue area using ImageJ (NIH) and MetaMorph v7.7.0.0 (Molecular Devices) software.

TUNEL staining

Tissue sections were deparaffinized and permeabilized with proteinase K (25 μg/ml in 100 mM Tris·HCl). An in situ apoptotic cell death detection kit (TUNEL Assay Kit - HRP-DAB, Abcam) based on the TUNEL assay was used as per the manufacturer’s instructions to detect apoptotic cells. The percentage of apoptotic nuclei per section was calculated by counting the total number of TUNEL-staining nuclei divided by the total number of hematoxylin-positive nuclei in 8–10 randomly selected fields at × 20 magnification.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), NPCs and BCO generation

Human iPSCs cell lines obtained from healthy patients were generated as previously described (Marchetto et al., 2010; Chailangkarn et al., 2016), by reprogramming fibroblasts from healthy donors. The iPSC colonies were plated on Matrigel-coated (BD Biosciences) plates and maintained in mTESR media (Stem Cell Technologies). hiPSC-derived NPCs were obtained and maintained as previously described (Marchetto et al., 2010; Chailangkarn et al., 2016). The iPSCs lines maintained in mTESR media were switched to N2 media, DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 1x N2 NeuroPlex Serum-Free Supplement (Gemini) supplemented with the dual SMAD inhibitors 1 μM of dorsomorphin (Tocris) and 10 μM of SB431542 (Stemgent) daily, for 48 hours. After two days, colonies were scraped off and cultured under agitation (95 rpm) as embryoid bodies (EB) for seven days using N2 media with dorsomorphin and SB431542. Media was changed every other day. EBs were then plated on Matrigel-coated dishes and maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 0.5x of N2 supplement, 0.5x Gem21 NeuroPlex Serum-Free Supplement (Gemini), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). After seven days in culture, rosettes arising from the plated EBs were manually picked, gently dissociated with StemPro Accutase (Life Technologies) and plated onto poly-L-ornithine/Laminin-coated (Life Technologies) plates. NPCs were maintained in DMEM/F12 with 0.5x N2, 0.5x Gem21, 20 ng/ml bFGF and 1% P/S. The media was changed every other day. NPCs were split as soon as confluent using StemPro Accutase for 5 mininutes at 37°C, centrifuged and replated with NGF with a 1:3 ratio in poly-L-ornithine/Laminin-coated plates.

Human iPSC-derived cortical organoids were obtained as previously described by Paşca et al. (2015) with modifications (Thomas et al., 2017; Trujillo et al., 2019). Briefly, iPSC colonies were gently dissociated using Accutase in PBS (1:1) (Life Technologies). Cells were then transferred to 6-well plates and kept under suspension. For neural induction, media containing DMEM/F12, 15 mM HEPES, 1x Glutamax, 1x N2 NeuroPlex (Gemini), 1x MEM-NEAA, 1 μM dorsomorphin (R&D Systems), 10 μM SB431542 (Stemgent) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin was used for six days. NPCs proliferation was obtained in the presence of Neurobasal media supplemented with 2x Gem21 NeuroPlex, 1x NEAA, 1x Glutamax, 20 ng/ml bFGF (Life Technologies) for seven days followed by seven additional days with the same media supplemented with 20 ng/ml EGF (PeproTech). Finally, for neuronal maturation, Neurobasal media supplemented 2x Gem21 NeuroPlex, 1x NEAA, 1x Glutamax, 10ng/mL of BDNF, 10ng/mL of GDNF, 10ng/mL of NT-3 (all from PeproTech), 200 μM L-ascorbic acid and 1mM dibutyryl-cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for seven days. The cells were kept in the same media thereafter in the absence of growth factors for neuronal maturation.

All the cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. All experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) and Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight (ESCRO) guidelines and regulations.

Generation of GFP-BCOs

The PGK-EGFP lentiviral vector construct was provided by Dr. Peter Yingxiao Wang’s laboratory in UC San Diego. For virus production, HEK293T cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000, the virus was harvested and concentrated using PEG-it solution according to manufacturer’s instructions (System Biosciences). A healthy control iPS line was then infected with the PGK-EGFP lentivirus and the EGFP+ cells were sorted by FACS (Aria, BD Biosciences) and replated on Matrigel plates. The brain cortical organoids were then generated from the sorted iPS cells.

GSC-brain cortical organoid formation

102 to 105 3565, 387 or 1517 GFP-labeled GSCs were added per BCOs and allowed to proliferate. GFP-labeled GSCs were present inside brain cortical organoids as early as 24 hours post-addition. The experiments were conducted 2–3 weeks after adding GSCs onto the BCOs. Neurobasal media supplemented with 1X GEM21 (Gemini), 1% NEAA (Life Technologies), 1% Glutamax (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) was used throughout the experiment.

GSC organoid formation

Between 1 × 105 or 2 × 105 of 3565, 387 or 1517 GSCs were put per well in a 24-well plate under constant agitation at 95 rpm at 37°C in Neurobasal media supplemented with 1X GEM21 (Gemini), 1% NEAA (Life Technologies), 1% Glutamax (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). The organoids started forming as early as 2 days after being put in suspension but were allowed to grow for 2–4 weeks before performing subsequent experiments.

GBM organoid and BCOs in vitro ZIKV infection

GSC-BCOs and GSC organoids were infected with H/PAN/2016/BEI-259634, Panama 2016 and PRVABC59, Puerto Rico 2015 ZIKV strains for 2 hours at 37°C at MOI of 5 FFU/cell and then the media containing the virus were removed and fresh media were added, Neurobasal media supplemented with 1X GEM21 (Gemini), 1% NEAA (Life Technologies), 1% Glutamax (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies).

Anti-integrin αvβ5 antibody treatment of GBM organoids

2- to 4-weeks-old GSC organoids were incubated with 50 μg/ml of the integrin αvβ5 antibody for 2–4 hours, then infected with PRVABC59 ZIKV strain for 2 hours at 37°C at an MOI of 5 FFU/cell. The media was then removed and fresh media containing 50 μg/ml of integrin αvβ5 antibody was added. The integrin αvβ5 antibody was added twice a week and GSC organoids were monitored for a month.

Image analysis

To calculate the integrated density of GFP in GSC-brain cortical organoids, ImageJ software was used. Briefly, the channels were split and the integrated density of the GFP channel was measured by the software.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad). The number of animals and replicate experiments is specified in each figure legend. Sample size is similar to those reported in previous publications (Wang et al., 2017a). All grouped data were presented as mean ± SEM as indicated in the figure legends. Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison correction, and two-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni multiple comparison test were used to assess the significance of differences between groups. These tests were performed when the sample size was large enough to assume that the means were normally distributed or that the distribution of residuals was normal. For groups being statistically compared, variances in data were similar. For animal survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier curves were generated and the Log-rank test was performed to assess statistical significance between groups.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Correlation between gene expression and patient survival was performed through analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and brain tumor datasets downloaded from the TCGA data portal (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/) or NCBI GEO database. Raw data from enhancer profiling of primary glioma tissues were deposited at GSE101148. ChIP-seq data from Suvà et al. (2014) were accessed from the NCBI GEO database at GSE54792 and GSE17312.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal antibody to SOX2 | Abcam | Cat# ab97959; RRID:AB_2341193 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibody to ZIKVE | EMD Millipore | Cat# MAB10216; RRID:AB_827205 |

| Rabbit Cleaved Caspase3 antibody | Cell signaling | Cat# 9664; RRID:AB_2070042 |

| Rabbit polyclonal antibody to AXL | Abcam | Cat# ab32828; RRID:AB_725598 |

| Rabbit polyclonal antibody to GFAP (Poly284000) | Biolegend | Cat# 840001; RRID:AB_2565444 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibody to beta-actin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A5316; RRID:AB_476743 |

| Rabbit monoclonal antibody to αvβ5 | Absolute Antibody | Cat# Ab00888 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibody to TUBB3 | Thermofisher | Cat# MA1-118; RRID:AB_2536829 |

| PE Mouse IgG1, κ Isotype Ctrl (FC) Control Antibody [Clone: MOPC-21] | Biolegend | Cat# 400113; RRID:AB_326435 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti-mouse | Thermofisher | Cat# A-11001; RRID:AB_2534069 |

| Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated anti-rabbit | Thermofisher | Cat# A-11012; RRID:AB_2534079 |

| Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated anti-rat | Thermofisher | Cat# A-11007; RRID:AB_10561522 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated anti-goat | Thermofisher | Cat# A-21447; RRID:AB_2535864 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked Secondary Antibody | Cell Signaling | Cat# 7074; RRID:AB_2099233 |

| Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Secondary Antibody | Cell Signaling | Cat# 7076; RRID:AB_330924 |

| donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP-lined Secondary Antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-2020; RRID:AB_631728 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Life Technologies | Cat# A-21206; RRID:AB_2535792 |

| Normal Goat IgG antibody (negative control for ChIP-PCR) | R & D Systems | Cat# AB-108-C; RRID:AB_354267 |

| Rabbit monoclonal (14C10) antibody to GAPDH | Cell Signaling | Cat# 2118; RRID:AB_561053 |

| Rabbit polyclonal antibody to CTIP2 | US Biological | Cat# B0807-13E2; RRID:AB_2064140 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibody to NeuN | PhosphoSolutions | Cat# 538-FOX3; RRID:AB_2560943 |

| Rat monoclonal antibody to ITGA6 | Thermofisher | Cat# 17-0495-82; RRID:AB_2016694 |

| Chicken polyclonal antibody to MAP2 | Abcam | Cat# ab5392; RRID:AB_2138153 |

| Rabbit monoclonal antibody to SATB2 | RevMAb Biosciences | Cat# 31-1251-00; RRID:AB_2783604 |

| LM609 antibody | EMD Millipore | Cat# MAB1976; RRID:AB_2296419 |

| P1F6 antibody | EMD Millipore | Cat# MAB1961Z; RRID:AB_94466 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| One Shot™ Stbl3™ Chemically Competent E. coli | Thermofisher | Cat# C737303 |

| ZIKA.HPAN | BEI Resources | NR-50210 |

| ZIKA.PRV | BEI Resources | NR-50240 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Neurobasal-A Medium | Life Technologies | Cat# A2477501 |

| GlutaMAX Supplement | Life Technologies | Cat# 35050061 |

| MEM nonessential amino acids | Thermofisher | Cat# 11140-050 |

| Sodium Pyruvate | Life Technologies | Cat# 11360070 |

| N2 NeuroPlex | Gemini Bio-Products | Cat# 400163 |

| Gem21 NeuroPlex | Gemini Bio-Products | Cat# 400160 |

| B27-supplement w/o Vitamin A | Life Technologies | Cat# 12587010 |

| Recombinant Human EGF Protein | R&D Systems | Cat# 236-EG-01M |

| Recombinant Human FGF basic, 145 aa (TC Grade) Protein | R&D Systems | Cat# 4114-TC-01M |

| Recombinant Human BDNF | Peprotech | Cat# 450-02 |

| Recombinant Human GDNF | Peprotech | Cat# 450-10 |

| Recombinant Human NT-3 | Peprotech | Cat# 450-03 |

| L-Ascorbic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A4403 |

| N6,20-O-Dibutyryladenosine 30,50-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D0627 |

| Stemolecule SB431542 | StemGent | Cat# 04-0010-10 |

| Dorsomorphin | R&D Systems | Cat# 3093 |

| ROCK inhibitor (Ri) Y-27632 dihydrochloride | Tocris | Cat# 125410 |

| StemPro Accutase Cell Dissociation Reagent | Thermofisher | Cat# A1110501 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) | Thermofisher | Cat# 15140122 |

| TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (1X), no phenol red | Thermofisher | Cat# 12604021 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum, qualified, US origin | Thermofisher | Cat# 26140079 |

| NuPage 4%−12% Bis-Tris gels | Invitrogen | NP0321BOX |

| PVDF membranes | EMD Millipore | Cat# ISEQ00010 |

| Matrigel hESC-Qualified Matrix | Corning | Cat# 354277 |

| LipoD293™ In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent | SignaGen Laboratories | Cat# SL100668 |

| JetPrime transfection reagent | Polyplus | Cat# 89129-926 |

| qScript cDNA synthesis kit | Quanta | Cat# 101414-106 |

| EndoFree Plasmid mini kit | Omega | Cat# D6948 |

| Click-iT EdU imaging Kit with Alexa 594 | Molecular probes | Cat# C10086 |

| TUNEL Assay Kit - HRP-DAB | Abcam | Cat# ab206386 |

| PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix | Thermofisher | Cat# A25742 |

| Radiant™ Green Hi-ROX qPCR Kit, 5000 × 20μl Reactions,50 × 1μL | Alkali scientific inc | Cat# QS2050 |

| Qiagen RNeasy Mini Plus kit | Qiagen | Cat# 74134 |

| QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 52904 |

| Cell Titer-Glo™ Cell Viability Reagent | Promega | Cat# G7570 |

| Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit with Annexin V Alexa Fluor™ 488 | Thermofisher | Cat# V13241 |

| High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Life Technologies | Cat# 4368814 |

| Lenti-X Concentrator | Clontech (Takara Bio USA) | Cat# 631232 |

| Pronase | Roche Applied Science | Cat# 10165921001 |

| Bradford assay | Bio-Rad Laboratories | Cat# 5000006 |

| Mission Lentiviral Packaging Mix | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SHP001 |