Abstract

Optimal protective immunity against babesial infection is postulated to require both complement-fixing and opsonizing antibodies in addition to gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-mediated macrophage activation. The rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1) of Babesia bigemina induces partial protective immunity and is a candidate vaccine antigen. Previous studies demonstrated that cattle immunized with native protein that were subsequently protected against challenge had a strong IFN-γ and weaker interleukin-4 (IL-4) response in immune lymph node lymphocytes that reflected the cytokine profile of the majority of CD4+ T-cell clones obtained from peripheral blood. RAP-1-specific T helper (Th) cell clones that coexpress IFN-γ and IL-4 are typical of numerous parasite-specific clones examined. However, the function of such cells as helper cells to enhance immunoglobulin secretion by bovine B cells has not been reported. In cattle, both immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2 can fix complement, but IgG2 is the superior opsonizing subclass. Therefore, studies were undertaken to ascertain the functional relevance of RAP-1-specific, CD4+ Th0 cells as helper cells to enhance IgG1 and/or IgG2 production by autologous B lymphocytes. For comparison, Th0 clones specific for the metazoan parasite Fasciola hepatica that expressed relatively more IL-4 than the B. bigemina-specific Th cells were similarly assayed. B. bigemina RAP-1-specific clones could enhance production of both IgG1 and IgG2 by autologous B cells, whereas Th cell clones specific for F. hepatica enhanced predominantly IgG1 production. The capacity to enhance IgG2 production was associated with production of IFN-γ by Th cells cocultured with B cells, antigen, and IL-2. The in vitro helper T-cell activity of these T-cell clones was representative of the in vivo serologic responses, which were composed of a mixed IgG1-IgG2 response in B. bigemina RAP-1 immune cattle and a biased IgG1 response in F. hepatica-immune cattle.

The apical complex antigen of Babesia bigemina, rhoptry-associated protein-1 (RAP-1), induces partial protection in cattle immunized with native protein (12, 39), but the precise mechanisms of protective immunity against this and the related B. bovis remain largely undefined (13, 44). Based on murine models of malarial and babesial parasite infection, it is hypothesized that T helper type 1 (Th1) cellular and humoral responses are important for maximum protection (18, 56–58, 61). Through gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production, CD4+ T cells can activate macrophages to enhance phagocytosis and secrete toxic molecules such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates (35, 54). As helper cells, CD4+ T cells can enhance synthesis of antibody subclasses that can activate complement-mediated killing and increase phagocytosis through opsonization (11, 44, 56).

In calves immunized with B. bigemina RAP-1 and subsequently shown to be protected against a challenge B. bigemina infection, there was a dominant IFN-γ response in draining lymph node lymphocytes following immunization and antigen stimulation ex vivo, although lower levels of interleukin-4 (IL-4) were also present (12, 47). CD4+ T-cell clones derived from these calves similarly expressed IFN-γ and little or no IL-4 and were characterized as either Th0 or Th1 clones (12, 46). RAP-1-specific Th cell clones that coexpress IL-4 and IFN-γ typify this predominant phenotype that has been identified in over 70 clones specific for a variety of parasitic and bacterial pathogens of cattle (8, 16). Based on this type of analysis, used originally to define murine Th1 and Th2 clones (42), a Th1-versus-Th2 dichotomy does not appear to be characteristic of the bovine CD4+ T-cell response at the clonal level (8). Although several CD4+ T-cell clones specific for the cattle parasite Theileria parva were shown to possess cytolytic activity (2), the helper cell function of bovine antigen-specific, CD4+ T-cell clones has not been previously demonstrated.

In studies where T-cell-independent polyclonal activators were used to stimulate bovine B cells, IL-4 induced production of immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgE, whereas IFN-γ induced IgG2 production (25, 26). Similar studies performed with mice showed that IFN-γ stimulated production of IgG2a, whereas IL-4 induced IgG1 and IgE production (51). Murine and human Th2 cells enhanced IgG1 and IgE production, respectively, in T-cell-dependent systems (5, 22, 38, 45). However, attempts to demonstrate helper function of classical Th1 cells from mice and humans produced conflicting results (5, 21, 38, 48, 53). In one study, the lack of helper cell activity by human Th1 clones was attributed to cytotoxicity for autoglogous B lymphocytes (21), which is consistent with the known ability of murine Th1 clones to induce Fas ligand (FasL)-mediated killing of target B cells that express Fas antigen (36, 55). The ability of IL-4 to rescue B cells from FasL-mediated apoptosis (28, 43) may also explain the differential helper function of Th2 and Th1 clones.

The objective of this study was to determine whether B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cell clones could promote or enhance IgG1 and IgG2 production by autologous B cells. Since sera from cattle immunized with B. bigemina RAP-1 had similar titers of RAP-1-specific IgG1 and IgG2, and several cloned T-cell lines coexpressed IFN-γ and IL-4 (46), we hypothesized that such clones could enhance both IgG1 and IgG2 production by autologous B cells. As controls, Th cell clones specific for the unrelated metazoan parasite Fasciola hepatica were similarly evaluated. F. hepatica-specific clones were selected since several were shown to express apparently higher levels of IL-4 than IFN-γ mRNA (7) and to produce less IFN-γ than Babesia-specific clones (8), and F. hepatica infection induces a restricted IgG1 response (19). In cattle, both IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses can fix complement, but IgG2 is the superior opsonizing antibody (40). The importance of both complement-fixing and opsonizing antibodies in protective immunity against hemoparasites underscores the relevance of understanding how antigen-specific bovine Th cells govern production of these IgG subclasses. We report that B. bigemina RAP-1-specific CD4+ T cells that coexpress IFN-γ and IL-4 function as helper cells to promote enhanced B-cell synthesis of IgG1 and IgG2. Furthermore, addition of IL-4 to the cultures could augment these responses when they were otherwise limited. In contrast, under similar culture conditions, F. hepatica-specific clones enhanced only IgG1 production by autologous B cells. These results mirrored the composition of parasite antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2 in the sera of B. bigemina RAP-1- and F. hepatica-immune cattle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CD4+ T-cell clones.

The antigen-specific, cloned T-cell lines used in these studies were derived from bovine 2216, immunized with native B. bigemina RAP-1 protein (clones 2216.1H4, 2216.1G8, and 2216.2B2), and bovine G1, infected with F. hepatica (clones G1.1H5, G1.2H4, and G1.3G10). Their origin, maintenance, antigen specificity, and cytokine profiles are described in detail elsewhere (7, 12, 14, 46). Briefly, B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cell clones proliferate in response to recombinant RAP-1 protein and soluble or membrane fractions of B. bigemina merozoites. F. hepatica-specific clones proliferate in response to soluble worm antigen.

Stimulation of cells and analysis of cytokines, Fas, FasL, and CD40 ligand (CD40L) in mRNA prepared from parasite-specific Th cells by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

T-cell clones were used 7 days after the last stimulation with antigen and antigen-presenting cells (APC), washed twice in complete medium, and cultured for 4 to 8 h at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml with 2.5 μg of concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml in the absence of APC. Total cellular RNA was isolated by the TRIzol reagent RNA isolation method as instructed by the manufacturer (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). RNA purity was assessed by evaluation of the A260/A280 ratio, and integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. As a positive control for cytokine mRNA expression, RNA was prepared from bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) stimulated at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per ml with 2.5 μg of ConA per ml for 18 h.

All RNA samples were treated with DNase (Ambion, Inc., Austin, Tex.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were then reverse transcribed, and PCR was performed with 10 ng of cDNA for cytokines, Fas, FasL, and CD40L amplification and with 0.05 to 0.2 ng of cDNA for β-actin amplification under conditions that amplified the product within a linear range with respect to input cDNA (16, 46). Total RNA (0.125 μg/reaction) was reverse transcribed to cDNA by adding a master mixture prepared as instructed by the manufacturer (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) and consisting of a final concentration of 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (PCR nucleotide mix; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), 20 U of RNase inhibitor, 50 U of murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, and 2.5 μM oligo(dT)16 in a final volume of 20 μl. The reactions were performed with a GeneAmp PCR 9600 system (Perkin-Elmer) under the following incubation conditions: 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 15 min, and 99°C for 5 min. Following reverse transcription, cDNA was amplified by PCR with bovine cytokine- or β-actin-specific primers (16). The primer sequences for bovine IL-2 and IFN-γ were kindly provided by Dante Zarlenga (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], Beltsville, Md.), and those for β-actin (20) were kindly provided by Gary Splitter (University of Wisconsin, Madison). Levels of expression of CD40L and FasL transcripts were also determined for all clones, including clone G1.2H4, which had not been previously analyzed, by RT-PCR using published primer sequences (33). Fas transcript expression in the Th cell clones was determined by using primers derived from the bovine Fas sequence (62). Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Forward and reverse primers (25 μM each) were added to each reaction in individual tubes, and a master mixture yielding a final concentration of 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, and 1.25 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) was added, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, in a total volume of 50 μl. The mixtures were heated to 94°C for 10 min and then amplified in a GeneAmp PCR 9600 system for 35 cycles under the following conditions: 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, with an extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products (25 μl) were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. To amplify cytokine-, Fas-, FasL-, or CD40L-specific product, the same amount (10 ng) of cDNA was used for each clone; and to amplify actin product, 0.05 to 0.2 ng of cDNA was used for each clone. After 35 cycles, these quantities of input cDNA from these clones resulted in amplification of product within the linear portion of the curve plotted as input cDNA concentration versus relative density of the PCR product. The specificities of the PCR products amplified from ConA-activated PBMC were verified by sequencing and found to be identical to the published GenBank sequences. Negative controls included simultaneous amplification of reactions performed without reverse transcriptase or without template, which yielded no detectable PCR products.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences used in this study

| Product | Forward primer (5′ to 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ to 3′) | Size (bp) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | GTACAAGATACAACTCTTGTCTTGC | TCAAGTCATTGTTGAGATGCTT | 466 | M12791 |

| IL-4 | TGCATTGTTAGCGTCTCCT | GTCTTTCAGCGTACTTGT | 423 | M77120 |

| IL-10 | GTTGCCTGGTCTTCCTGGCTG | TATGTAGTTGATGAAGATGTC | 482 | U00799 |

| IFN-γ | TATGGCCAGGGCCAATTTTTTAGAGAAATAG | TTACGTTGATGCTCTCCGGCCTCGAAAGAG | 438 | M29867 |

| TNF-α | ATGAGCACCAAAAGCATGATCCGG | CCAAAGTAGACCTGCCCAGACTC | 686 | Z14137 |

| TNF-β | TCCGTGGCATTGGCCTCACA | GGGACCAGGAGGGAATTGTTGC | 202 | Z14137 |

| Fas | ATGTCCTTCATGACTATGTCAC | ATGTCCGGGATCTGGGTTC | 917 | U24240 |

| FasL | TATTCCAAAGTATACTTCCGGGGTCA | ACTGCCCCCAGGTAGGCTGCTG | 168 | U95844 |

| CD40L | AACTCTAACGCAGCATGATC | GCTTTCCTGGATTGTGAAGA | 862 | Z48469 |

| β-Actin | ACCAACTGGGACGACATGGAG | GCATTTGCGGTGGACAATGGA | 890 | K00622/3 |

To compare relative levels of cytokine, Fas, FasL, and CD40L transcripts expressed by individual Th cell clones used in this study, the amount of amplified cDNA stained with ethidium bromide relative to that of actin cDNA was determined by detecting fluorescent signals activated by UV light, using an IS-1000 digital imaging system (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.). For each clone, the ratio of IFN-γ to IL-4 steady-state mRNA was then calculated.

B-lymphocyte purification.

B cells were purified from PBMC of bovines G1 and 2216 by negative selection using a modified panning procedure (9, 25, 50). Macrophages were removed by addition of 15 μl of a 4% carbonyl iron suspension in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to 60 ml of blood collected in 2 ml of EDTA (0.5 M, pH 8.0) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min with gentle agitation. PBMC were isolated by Histopaque (Sigma) density centrifugation, washed twice in Alsever’s solution (Sigma), and resuspended in panning solution (3% bovine serum albumin fraction V [Sigma] in Hanks balanced salt solution [pH 7.4]) containing 0.9 mM Mg2+ and 1.25 mM Ca2+). Following centrifugation at 250 × g for 10 min at 10°C, the cells were resuspended at a concentration of 107 cells per ml in panning solution, and 9 ml of cell suspension was placed in a T-75 flask (Corning, Cambridge, Mass.) and allowed to adhere at room temperature for 1 h, with gentle swirling after 30 min. The nonadherent cells were removed, and after careful rinsing with complete RPMI 1640 medium (10), the adherent, enriched B-cell population was collected by vigorous agitation. The cells were washed and resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution, and CD3+ T cells were removed following incubation of 107 cells per ml with sodium azide-free bovine CD3-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) MM1A (15 μg/ml; kindly provided by William C. Davis, Washington State University, Pullman) for 30 min at 4°C, incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG-coated magnetic beads (Dynabead M-450;) Dynal Inc., Lake Success, N.Y.), and removal of bead-bound cells with a magnet according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The remaining cells were washed in complete RPMI 1640, and aliquots were removed for cell surface phenotype analysis.

Flow cytometric analysis of purified B cells.

Cell surface phenotype analysis was performed by using flow cytometry and MAbs (15 μg/ml) specific for bovine CD2 (MUC 2A), CD3 (MM1A), CD4 (CACT 138A), CD8 α and β chains (CACT 80C and BAT 82A), γδ TcR1-N12 (CACT 61A), and CD14 (CAM 36A). These MAbs were kindly provided by William C. Davis. A MAb (IL-A24) that stains a molecule present on dendritic cells and macrophages/monocytes (24, 41) was obtained from the International Laboratory for Research in Animal Diseases, Nairobi, Kenya. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin [a mixture of IgG, IgA, and IgM affinity-purified F(ab′)2 fragments; Cappel/Organon Teknika, Malvern, Pa.] was used as a secondary antibody, and background staining was indicated by staining with this antibody alone. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled, affinity-purified (Fab′)2 goat anti-bovine IgG F(ab′)2-specific antibody (50 μg/ml; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc., Avondale, Pa.) was used to label B cells. Following the negative selection panning procedure, <1% of the cells expressed TcR1, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, or the molecule recognized by IL-A24, indicating that T cells, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells were depleted. The majority (approximately 90%) of the panned cells expressed surface immunoglobulin, indicating the purity of the B-cell population.

B-cell proliferation assays.

To verify the purity of the negatively selected B cells, PBMC or B cells were cultured for 3 days in complete RPMI 1640 medium at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per ml in 100 μl with 1 to 2 μg of the T-cell mitogen ConA or the T- and B-cell mitogen pokeweed mitogen (PWM; Sigma) per ml. The cells were radiolabeled for the last 6 to 18 h of culture with 0.25 μCi [3H]thymidine (New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.), harvested, and counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Results are expressed as mean counts per minute ± 1 standard deviation (SD) and are presented as mean proliferative responses of two bovines.

Antigen presentation by B cells or PBMC to Th cell clones.

Cloned T-cell lines were used in proliferation assays 7 days after stimulation with antigen and irradiated (3,000 rads from a 60Co source) PBMC as a source of APC as described elsewhere (7, 46). Soluble worm antigen, kindly provided by Allison Ficht, Texas A&M University, College Station, was prepared from F. hepatica liver flukes as described elsewhere (7). Briefly, 15 frozen adult flukes were ground to a fine powder and suspended in 10 ml of PBS in the presence of 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The suspension was homogenized with a tissue homogenizer and centrifuged at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant was diluted to a concentration of 1 mg of protein per ml and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter. Recombinant B. bigemina RAP-1 protein was prepared as described previously (46). T cells (3 × 105 cells/ml) and antigen (25 μg/ml) were cultured in 100-μl volumes in duplicate or triplicate wells of 96-well round-bottom plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) for 3 days with irradiated APC consisting of PBMC or B cells used at 0.5 × 106, 1 × 106, 2 × 106, and 4 × 106 cells per ml. The cells were radiolabeled with 0.25 μCi of [3H]thymidine for the last 6 to 8 h of culture, harvested, and counted. Results are expressed as the mean counts per minute of replicate cultures ± 1 SD and are representative of two or three independent assays.

Coculture of B cells and T cells.

Th cell clones (2 × 105 cells/ml) and autologous B cells (4 × 105 cells/ml) were cultured with 25 μg of antigen per ml in complete RPMI 1640 medium in duplicate in 0.5- or 1-ml volumes in polypropylene 6-ml snap-cap tubes (Falcon 2063 tubes; Becton Dickinson, Lincoln, Park, N.J.) for 6 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air with 25 U of recombinant human IL-2 (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml, with or without 20 ng of Pichia pastoris-expressed recombinant bovine IL-4 (8), per ml. IL-2 was included in most cultures since it has been shown to enhance Th cell proliferation and secretion of both IgG1 and IgG2 by B cells stimulated via T-cell-independent means (25, 26). As a positive control to show that negatively selected B cells secreted IgG1 and IgG2 when stimulated by T-cell-independent means (25, 26), B cells were cultured with 100 μg of PWM and 50 U of IL-2 per ml plus either 25 ng of recombinant bovine IL-4 or 5 ng of recombinant bovine IFN-γ (kindly provided by Lorne Babiuk, VIDO, Sasketoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) per ml. The bovine IFN-γ had a biological activity of approximately 0.6 U/ng when assayed for neutralization of vesicular stomatitis virus (4). To determine background levels of IgG secretion, B cells were cultured with antigen alone in the absence or presence of the indicated cytokines. Alternatively, B cells were cultured with T cells in the absence of antigen. Supernatants were harvested following centrifugation of the tubes at 250 × g for 10 min and were stored at −20°C.

Determination of IgG concentrations in culture supernatants.

Prior to assay, supernatants were centrifuged (5,000 × g for 10 min) to pellet any cellular debris. Each duplicate sample was analyzed two or more times by sandwich capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect IgM, IgG1, and IgG2, using reagents specific for these immunoglobulin classes and subclasses as described elsewhere (9). To detect IgM, a symmetrical sandwich capture ELISA was performed (26). Briefly, Immulon II 96-well U-bottom plates (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.) were coated overnight at 4°C with goat anti bovine IgM (1 μg/well; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) diluted in PBS. The plates were washed three times, blocked for 1 h at 37°C with 10% horse serum (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) diluted in PBS, and washed three times; culture supernatants diluted 1:2 to 1:10 in PBS were added to the wells in triplicate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. To measure IgG1 and IgG2, plates were coated with goat anti-mouse IgG (1 μg/well; Kirkegaard & Perry) in PBS overnight, washed three times in PBS, and blocked with 10% horse serum in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. Mouse anti-bovine IgG1 (1:500 dilution) or anti-bovine IgG2 (1:1,000 dilution) MAb purchased from Serotec, Ltd. (Oxford, England) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Test supernatants diluted in 5% IgG-free normal horse serum (GIBCO-BRL) in PBS were added, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were then washed, and alkaline phosphate-conjugated goat anti-bovine IgM (Kirkegaard & Perry) or alkaline phosphate-conjugated goat anti-bovine IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry), which had previously adsorbed against mouse IgG, was added. The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and washed, and substrate was added for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction was developed by using a kit supplied by Kirkegaard & Perry according to the manufacturer’s instruction, and the optical density at 405 nm (OD405) was determined with a Dynatech MR5000 ELISA plate reader. Each assay plate contained immunoglobulin standards consisting of purified bovine IgM (Sigma) or protein G affinity-purified bovine IgG1 and IgG2 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, Pa.). Results are presented as mean IgM, IgG1, or IgG2 concentrations (in nanograms or micrograms per milliliter) ± 1 SD in duplicate cultures of B cells. The levels of secreted immunoglobulin were analyzed for statistical significance by Student’s one-tailed t test.

Determination of IFN-γ in culture supernatants.

Supernatants harvested at 6 days from the same cocultures of B and T cells used for IgG1 and IgG2 analysis were assayed for IFN-γ with a commercial ELISA kit (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, Maine) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. IFN-γ activity was estimated from a standard curve derived with a dilution series of a Th cell clone culture supernatant that was shown to contain 400 U of IFN-γ per ml by the vesicular stomatitis virus cytopathic effect reduction assay (15).

B. bigemina RAP-1- and F. hepatica-specific ELISA.

ELISAs were performed essentially as described previously (46), with the following modifications. Immulon II ELISA plates (Dynatech) were coated overnight with 0.1 μg of recombinant B. bigemina RAP-1 fusion protein or F. hepatica soluble worm antigen. The plates were washed extensively and blocked for 1 h with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.5% porcine serum albumin (blocking buffer). Bovine sera obtained from the cattle before and at several time points after infection with F. hepatica or immunization with native B. bigemina RAP-1 were serially diluted (threefold) in blocking buffer and added in triplicate for 1 h at 37°C. After being washed, the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with anti-bovine IgG1 (MAb DAS17) diluted 1:2,000 or anti-bovine IgG2 (MAb DAS2) diluted 1:4,000 in blocking buffer. The MAbs were kindly provided by Al Guidry, USDA. The plates were then washed and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy plus light chains; Kirkegaard & Perry) diluted 1:1,000 in PBS. The plates were washed and developed with TMB substrate, using a kit supplied by the manufacturer (Kirkegaard & Perry). The reactions were analyzed at OD650 on an ELISA plate reader. Serially diluted bovine IgG1 and IgG2 (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.) were simultaneously used to directly coat the plates to verify the specificity of the anti-IgG subclass antibodies. The dilutions of anti-IgG1 and IgG2 MAbs used gave similar reactivities with serially diluted, purified IgG1 and IgG2, respectively. The serum titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the dilution that gave a positive ELISA value greater than 3 SD above the background reading, which was the mean OD reading of blocking buffer alone in the absence of bovine serum. The results are presented as the mean titers from two or three separate assays.

RESULTS

Cytokine, Fas, FasL, and CD40L expression by B. bigemina RAP-1- and F. hepatica-specific Th cell clones.

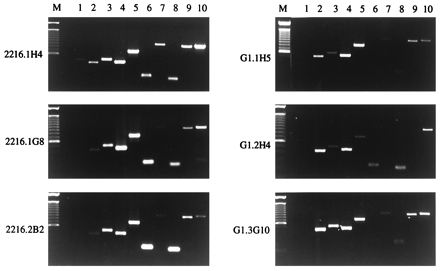

The main objective of this study was to determine the capacity of B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cells to provide antigen-dependent cognate help for autologous B cells. Furthermore, it was of interest to determine whether Th cells coexpressing IL-4 and IFN-γ could enhance both IgG1 and IgG2 production by B cells. Therefore, T-cell clones selected for these studies included three B. bigemina RAP-1-specific clones that expressed Th0- or Th1-like cytokine profiles and relatively high levels of IFN-γ protein (46). For comparative purposes, we also selected three F. hepatica-specific clones that expressed Th0 cytokine profiles and relatively low levels of IFN-γ protein (7, 14). T cells were stimulated with ConA in the absence of APC; then RT-PCR was performed to analyze expression of cytokines IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and TNF-β and of molecules involved in cell signaling, including Fas, FasL, and CD40L (Fig. 1). The data are summarized in Table 2. As observed before, RAP-1 specific clones 2216.1H4, 2216.1G8, and 2216.2B2 expressed no or barely detectable IL-2, low levels of IL-4, high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α, and detectable levels of TNF-β, categorizing these as type 1 Th clones. Somewhat different cytokine profiles were observed with the F. hepatica-specific T cells, which had undetectable levels of IL-2, relatively more IL-4, and less TNF-β, classifying these as unrestricted, or Th0, cells. IL-10 was expressed at some level by all clones and is not diagnostic of a Th2 response in cattle (8, 14). In these and previous studies, we observed similar patterns of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ production by these clones stimulated with either ConA or antigen and APC (7, 14, 46). We also previously reported that all of these clones except G1.2H4, which had not been examined, expressed FasL and CD40L transcripts (33). We made the same observation in the present study and in addition found that clone G1.2H4 also expressed FasL but barely detectable levels of CD40L. Fas mRNA, which had not been examined for bovine Th cell clones, was detected in all Th cell clones except G1.2H4. Thus, assuming that mRNA expression predicts surface CD40L expression, all of these T-cell clones have the potential to provide B-cell help through CD40 ligation. Similarly, all clones could potentially mediate FasL-induced apoptosis via interaction with Fas+ T or B cells.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of steady-state levels of transcripts for cytokines, Fas, FasL, and CD40L in B. bigemina RAP-1 and F. hepatica-specific Th cell clones by RT-PCR. RT-PCR was performed with DNase-treated RNA prepared from the indicated Th cell clones specific for B. bigemina RAP-1 (left) or F. hepatica (right) following stimulation with ConA. Primers specific for bovine IL-2 (lane 1), IL-4 (lane 2), IL-10 (lane 3), IFN-γ (lane 4), TNF-α (lane 5), TNF-β (lane 6), Fas (lane 7), FasL (lane 8), CD40L (lane 9), and β-actin (lane 10) were used. For each PCR, 10 ng of cDNA was used with the exception of β-actin, where 0.05 to 0.2 ng of cDNA was used. The amplified PCR products were electrophoresed on agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light, and the densitometry images were recorded. The sizes of the amplified PCR products are listed in Table 1. Markers (M) consisting of a 1-kb DNA ladder were included for each gel.

TABLE 2.

Summary of cytokine, Fas, FasL, and CD40L steady-state mRNA expression by Th cell clones specific for B. bigemina RAP-1 or F. hepatica soluble worm antigen

| Th cell clone and specificitya | Relative level of expression of steady-state mRNAb

|

Ratio, IFN-γ/IL-4 steady-state mRNAc | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | IL-4 | IL-10 | IFN-γ | TNF-α | TNF-β | Fas | FasL | CD40L | ||

| B. bigemina RAP-1 | ||||||||||

| 2216.1H4 | w | w | w | + | + | w | w | w | w | 7 |

| 2216.1G8 | − | w | w | ++ | ++ | + | w | w | w | 16 |

| 2216.2B2 | − | w | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | w | ++ | ++ | 9 |

| F. hepatica | ||||||||||

| G1.1H5 | − | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | − | w | w | + | 2 |

| G1.2H4 | − | ++ | w | ++ | w | w | − | w | w | 1 |

| G1.3G10 | − | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | − | w | w | + | 1 |

Th cell clones specific for B. bigemina RAP-1 or F. hepatica were stimulated with ConA as described in the text, and total RNA was harvested.

DNase-treated RNA was reverse transcribed, PCR was performed for the indicated genes or β-actin, and products were analyzed by densitometry imaging on ethidium bromide-stained gels. Comparison of the signal intensity relative to that of β-actin is indicated as w (weaker), + (comparable), or ++ (stronger). −, no signal detected.

Determined by densitometric analysis of RT-PCR products.

Antigen presentation of Th cell clones by autologous B cells.

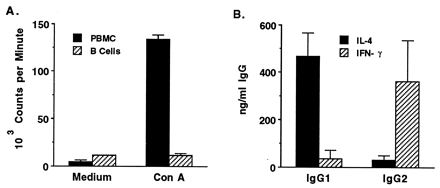

Following removal of macrophages with carbonyl iron, B cells were purified by negative selection using a modified panning method and removal of CD3+ T cells (9). To verify the lack of contaminating T cells, negatively selected B cells or PBMC were tested for responsiveness to ConA. ConA elicited strong proliferation by PBMC but was repeatedly not stimulatory for B cells (Fig. 2A). In contrast, PWM (1 μg/ml) stimulated proliferation of purified B cells approximately 10-fold (data not shown). The ability of B cells to present antigen to the Th cell clones used in this study was then determined by measuring T-cell proliferation to a single, optimal concentration of antigen and different numbers of purified B cells or PBMC. As seen in Fig. 3, B cells were generally poorer APC than unseparated PBMC. However, the differences in antigen-induced proliferation stimulated by B cells or PBMC were less evident for clones 2216.1G8, 2216.2B2, G1.2H4, and G1.3G10, whereas clones 2216.1H4 and G1.1H5 responded reproducibly (in three assays) very poorly to antigen when B cells were used as APC. The reasons for these differences are not known, but differences in the density of costimulatory molecules, such as CD40L, or death molecules, such as FasL, on the T-cell clones could contribute to these results (3, 31, 49).

FIG. 2.

Verification of B-cell purity and function. PBMC or negatively selected B cells were obtained from animals 2216 and 2234, cultured for 3 days with 2 μg of Con A per ml, radiolabeled, harvested, and counted. Results are presented as means ± 1 SD and represent the mean responses of the two animals (A). B cells from these animals were cultured for 6 days with PWM (100 μg/ml), IL-2 (50 U/ml), and either IL-4 (25 ng/ml) or IFN-γ (5 ng/ml), as indicated; total IgG1 and IgG2 in the cell supernatants were quantified by ELISA. Results are presented as the mean levels of IgG1 or IgG2 present in B-cell cultures of donor animals 2216 and 2234.

FIG. 3.

Antigen presentation by B cells to Th cell clones specific for B. bigemina RAP-1 or F. hepatica. Th cells clones were cultured for 3 days with 0.5 × 105 to 4 × 105 autologous B cells or PBMC and 25 μg of B. bigemina RAP-1 antigen (A to C) or F. hepatica soluble worm antigen (D to F) per ml, radiolabeled, and harvested. Results are presented as means ± 1 SD of duplicate cultures.

Immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells cocultured with RAP-1-specific Th cell clones and specific antigen.

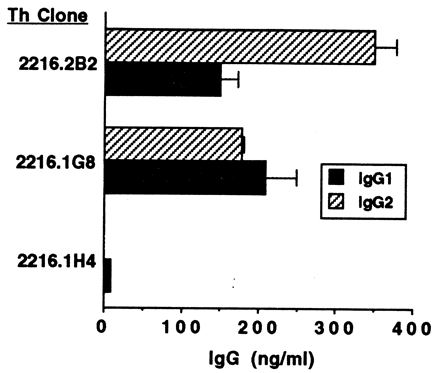

We wished to determine whether B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cells could provide cognate help to B cells for IgG1 or IgG2 production. Furthermore, Th cell clones derived from cattle immune to two different types of parasite (protozoan and metazoan) and which expressed somewhat different cytokine profiles were compared for stimulation of IgG1 and IgG2 by autologous B lymphocytes cocultured with specific antigen. Preliminary studies with lymphocytes cultured for 6 or 10 days showed that optimal IgG synthesis occurred at 6 days of culture, which was used thereafter (data not shown). To ensure that the B cells purified by negative selection were capable of synthesizing IgG1 and IgG2, PWM and IL-2 were used to activate B cells (Fig. 2B). Enhanced levels of IgG1 in response to yeast-expressed IL-4 were observed as described previously, using COS 7 cell-expressed IL-4 (26), and enhanced levels of IgG2 in response to IFN-γ were also observed as reported previously (25). Furthermore, supernatants from mixtures of B cells and Th cell clones cultured in the absence of antigen did not contain more IgG1 or IgG2 than supernatants of B cells cultured without antigen (data not shown). When B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cell clones cultured with autologous B cells, RAP-1 antigen, and IL-2 were tested for helper cell function, two clones (2216.2B2 and 2216.1G8) stimulated IgG1 and IgG2 production that was significantly greater (P ≤ 0.05) than that by B cells cultured with antigen and IL-2 alone, and one clone (2216.1H4) was unable to provide help (Fig. 4). IgM levels were not substantially above background levels (data not shown). Data are presented for one of two experiments with similar results, except that in the second experiment clone 2216.2B2 did not provide help for IgG1 synthesis (Fig. 5). The reason for this difference in results is not known, but in the second experiment the high background level of IgG1 (2.4 μg/ml) secreted by B cells cultured with antigen alone may have masked any additional effect of this Th cell clone.

FIG. 4.

Helper cell function of B. bigemina RAP-1-specific T-cell clones. T cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were cocultured for 6 days with autologous B cells (4 × 105 cells/ml), 25 μg of B. bigemina RAP-1 antigen per ml, and 20 U of IL-2 per ml; total IgG1 and IgG2 levels in the cell supernatants were determined by ELISA. Results were presented as mean levels ± 1 SD of IgG1 or IgG2 in supernatants of duplicate cultures tested by ELISA. The background IgG levels in cultures of B cells plus antigen and IL-2 were subtracted; these amounts were 0 (undetectable) for B cells cultured with clones 2216.1H4 and 2216.2B2 and 20 ng of IgG1 per ml and 37 ng of IgG2 per ml for B cells cultured with clone 2216.1G8.

FIG. 5.

Effects of exogenous IL-4 on IgG1 and IgG2 production by cocultures of B cells and B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th clones. T cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were cocultured for 6 days with autologous B cells (4 × 105 cells/ml), B. bigemina RAP-1 antigen (25 μg/ml), and IL-2 (20 U/ml) alone or with IL-4 (20 ng/ml), as indicated; total IgG1 and IgG2 levels in the cell supernatants were determined by ELISA. Results are presented as mean levels ± 1 SD of IgG1 or IgG2 in supernatants of duplicate cultures determined by ELISA. The background IgG1 and IgG2 levels in cultures of B cells, antigen, and IL-2 without or with IL-4 were subtracted; these amounts were 20 to 124 ng of IgG1 per ml and 37 to 60 ng of Ig2 per ml IgG2 per ml for clone 2216.1H4 and 1.5 to 3.0 μg of IgG1 per ml and 0 to 153 ng of IgG2 per ml for clones 2216.1G8 and 2216.2B2.

Effect of adding exogenous IL-4 on IgG secretion by B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cell clones.

Because B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cell clones expressed relatively little IL-4 mRNA, and IL-4 has been shown to enhance B-cell survival in several ways that include the prevention of FasL-mediated activation induced B-cell death (28, 43), the effect of exogenous bovine IL-4 on IgG1 and IgG2 production by B cells cultured with Th cells, antigen, and IL-2 was determined. Exogenous IL-4 resulted in enhanced (clone 2216.1H4; P < 0.05) or equivalent (clones 2216.1G8 and 2116.2B2) levels of IgG2 production by B cells (Fig. 5). IL-4 also enhanced IgG1 secreted in response to clone 2216.2B2, which in this experiment did not enhance IgG1 in the absence of IL-4.

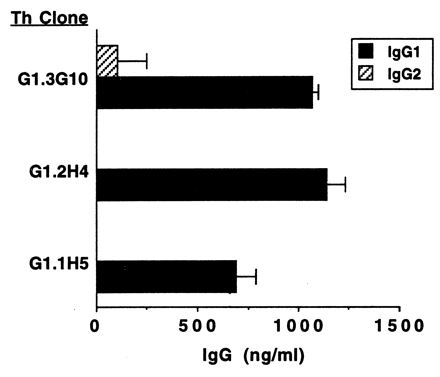

Immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells cocultured with F. hepatica-specific Th cell clones and specific antigen.

The three F. hepatica Th cell clones cultured with antigen, IL-2, and autologous B cells all stimulated significantly (P ≤ 0.05) enhanced production of IgG1 by B cells (increased by approximately 650 to 1,150 ng/ml above background). In contrast, IgG2 levels were either less than or not significantly grater than background levels of B-cell-secreted IgG2 (Fig. 6). IgM levels were not substantially affected (data not shown). Addition of IL-4 to the cultures of F. hepatica-specific Th cell clones did not stimulate IgG1 or IgG2 production by B cells significantly above background (Table 3 and data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Helper cell function of F. hepatica-specific T-cell clones. T cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were cocultured for 6 days with autologous B cells (4 × 105 cell/ml), 25 μg of F. hepatica soluble worm antigen per ml, and 20 U of IL-2 per ml; total IgG1 ad IgG2 levels in the cell supernatants were determined by ELISA. Results are presented as mean levels ± 1 SD of IgG1 or IgG2 in supernatants of duplicate cultures tested by ELISA. The background IgG levels in cultures of B cells plus antigen and IL-2 were subtracted; these amounts were 472 ng of IgG1 per ml and 1,564 ng of IgG2 per ml.

TABLE 3.

Relationship of IgG2 and IFN-γ secreted by cocultures of antigen-stimulated Th cell clones and autologous B lymphocytes

| Th cell clone and specificity | Cytokine(s) addeda | IgG2 (ng/ml)b | IFN-γ (U/ml)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. bigemina RAP-1 | |||

| 2222.16.1H4 | None | 185 ± 11 | 0 |

| IL-2 | 220 ± 82 | 87.5 | |

| IL-2 ± IL-4 | 1,238 ± 95 | 79.2 | |

| 2216.1G8 | None | 1,999 ± 60 | 0.4 |

| IL-2 | 1,611 ± 223 | 10.4 | |

| IL-2 ± IL-4 | 1,653 ± 209 | 12.6 | |

| 2216.2B2 | None | 387 ± 43 | 0.04 |

| IL-2 | 1,714 ± 456 | 37.1 | |

| IL-2 ± IL-4 | 1,957 ± 91 | 43.5 | |

| F. hepatica | |||

| G1.1H5 | None | 0 | 0.1 |

| IL-2 | 0 | 0 | |

| IL-2 ± IL-4 | 0 | 0 | |

| G1.2H4 | None | 0 | 0 |

| IL-2 | 0 | 0.3 | |

| IL-2 ± IL-4 | 0 | 0.4 | |

| G1.3G10 | None | 0 | 0 |

| IL-2 | 101 ± 147 | 1.0 | |

| IL-2 ± IL-4 | 0 | 0.8 |

B cells (4 × 105) and Th cells (2 × 105) were cultured for 6 days with 25 μg of B. bigemina RAP-1 antigen (2216 clones) or F. hepatica soluble worm antigen (G1 clones) per ml with medium, 25 U of human recombinant IL-2 per ml, or IL-2 plus 20 ng of bovine IL-4, per ml.

Culture supernatants were analyzed for IgG2 by ELISA. Results represent as IgG2 concentrations after subtraction of the background IgG2 levels of B cells plus antigen. The levels of IgG2 produced by B cells cultured with B. bigemina RAP-1 antigen were 37 to 60 ng/ml in the experiment with clone 2216.1H4 and 0 to 153 ng/ml in the experiments with clones 2216.1G8 and 2216.1H4. The IgG2 levels produced by B cells cultured with F. hepatica soluble worm antigen were 1,564 to 1,620 ng/ml.

Culture supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ by ELISA and compared with a standard IFN-γ supernatant which contained 400 U/ml.

Comparison of IFN-γ levels in cocultures of B cells and Th cell clones.

Levels of IFN-γ protein were determined by ELISA in the same supernatants used to measure IgG1 and IgG2 shown in Fig. 5 and 6. IFN-γ was undetectable or low in supernatants of all clones stimulated without IL-2, but only B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cells expressed significant levels of IFN-γ when optimally stimulated with antigen and IL-2 (Table 3). These levels, which range from approximately 10 to 87 U/ml (equivalent to 17 to 145 ng/ml), are similar to the amount of recombinant bovine IFN-γ used to induced IgG2 production by mitogen and IL-2-activated B cells (Fig. 2B and reference 25). Although incapable of producing significant amounts of IFN-γ under these culture conditions, the F. hepatica-specific clones proliferated in response to specific antigen presented by either PBMC or B cells as APC (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, a specific biological assay or ELISA for bovine IL-4 is not available for determining IL-4 protein levels. However, for individual clones, the steady-state levels of mRNA were compared for the signature cytokines IL-4 and IFN-γ involved in IgG1 and IgG2 production. Ethidium bromide-stained RT-PCR products for these cytokines were semiquantified by densitometry image analysis (Fig. 1). The ratios of IFN-γ to IL-4 transcript levels for these clones are presented in Table 2. As shown previously for antigen-stimulated T-cell clones (7, 46), the three B. bigemina RAP-1-specific clones expressed type 1 cytokine profiles following ConA stimulation, indicated by a high ratio of IFN-γ to IL-4. In contrast, F. hepatica-specific clones expressed relatively lower ratios of IFN-γ to IL-4.

Analysis of IgG1 and IgG2 titers specific for B. bigemina RAP-1 or F. hepatica in immune cattle.

We previously reported that the titers of B. bigemina RAP-1-specific IgG1 and IgG2 were comparable in immune cattle 2216 and 2234 (46). Using a different set of anti-bovine IgG1 and IgG2 antibody reagents, we reanalyzed these sera together with sera from F. hepatica-immune cattle G1 and G8 (Table 4). Once again, the titers of B. bigemina RAP-1-specific IgG1 and IgG2 were similar in each animal and representative of a mixed response. In contrast, the F. hepatica-specific response was restricted to IgG1; IgG2 was not detected.

TABLE 4.

Antigen-specific titers in sera of cattle immunized with B. bigemina RAP-1 or infected with F. hepatica

| Animal | Parasitea | Time relative to immunization or infectionb | Antigen-specific IgG titerc

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 | IgG2 | |||

| 2216 | B. bigemina | Preimmunization | <10 | <10 |

| 2 mo after 5th inoculation | 3,000 | 1,900 | ||

| 2234 | B. bigemina | Preimmunization | 10 | 10 |

| 2 mo after 5th inoculation | 900 | 1,050 | ||

| G1 | F. hepatica | Preinfection | <30 | <30 |

| 3 mo postinfection | 270 | <10 | ||

| 1 mo postchallenge | 45,000 | <30 | ||

| G8 | F. hepatica | Preinfection | <10 | <10 |

| 3 mo postinfection | 810 | <30 | ||

| 1 mo postchallenge | 8,100 | <10 | ||

Calves 2216 and 2234 were immunized five times with B. bigemina RAP-1 in RIBI adjuvant (46). Calves G1 and G8 were infected with 1,000 metacercariae of F. hepatica (7) and challenged 2 years later with 2,000 metacercariae.

Sera were obtained before immunization or infection and at the indicated times thereafter.

Mean titer determined in two or three ELISAs.

DISCUSSION

These studies demonstrate for the first time helper cell function for bovine CD4+ T cells and extend our analysis of Th cells responses to B. bigemina RAP-1, a candidate vaccine antigen for this parasite. We show that Th cell clones derived from B. bigemina-immune cattle that produce IFN-γ can enhance production of IgG2, which is the most important opsonizing antibody subclass in cattle. Although the levels of IgG1 and IgG2 produced by autologous B lymphocytes varied from experiment to experiment, which may reflect different basal levels of B-cell activation, we repeatedly observed enhanced production of IgG2 by clone 2216.2B2 and of both IgG1 and IgG2 by clone 2216.1G8. In contrast, clone 2216.1H4 was repeatedly a poor helper cell for enhancing either IgG subclass. Although CD40L expression on the cell surface was not examined due to lack of specific reagents, there were no striking differences in the level of expression of CD40L steady-state mRNA that could readily explain the differential helper cell functions among these RAP-1-specific clones (reference 33, Fig. 1, and Table 2). Thus, all of the Th cell clones examined in this study have the potential to express surface CD40L required for cognate T-cell help (3, 31).

In general, bovine B cells were less effective APC than unseparated PBMC. Cytokine expression patterns by the T-cell clones did not appear to correlate with the ability to respond to antigen presented by B cells. For example, B cells were capable APC for the type 1 Th clone 2216.2B2 (Table 2 and Fig. 3) and for several Mycobacterium tuberculosis or M. bovis purified protein derivative-specific Th1 clones (references 6 and 8 and data not shown). Studies with murine and human B cells have also reported variable APC function, which did not always correlate with Th cell phenotype (23, 27, 29, 37). The capacity of B cells to present antigen may be dictated by requirements for costimulation by the different Th clones (1). In addition, radiation sensitivity may explain the reduced Th cell proliferative responses in our assays when B cells were used as APC (30).

Using Th cell clones specific for two different types of parasite, we observed differences in the relative levels of steady-state expression of IL-4 transcripts, the ratios of IFN-γ to IL-4 transcript levels, and levels of secreted IFN-γ that appear to be associated with differences in Th cell function in vitro. Clones specific for F. hepatica enhanced production of IgG1 but were incapable of enhancing IgG2 production by B cells above background levels. This was associated with (i) expression of relatively high levels of IL-4 and low ratios of IFN-γ to IL-4 steady-state mRNA levels upon antigen or mitogen stimulation and (ii) a lack of IFN-γ production by these cells cultured with B cells, antigen, and IL-2. In contrast, stimulation of B. bigemina RAP-1-specific clones under the same conditions resulted in relatively low levels of IL-4 and high ratios of IFN-γ to IL-4 steady-state mRNA levels, as well as significant IFN-γ production that was associated with the ability to enhance IgG2 production by autologous B cells. Interestingly, addition of IL-4 to the cultures resulted in enhanced IgG2 production by one B. bigemina RAP-1-specific clone and enhanced IgG1 production by one B. bigemina RAP-1-specific clone that otherwise stimulated low levels of these IgG subclasses. In contrast, IL-4 did not potentiate IgG production by B cells cocultured with F. hepatica-specific Th cell clones. Thus, our results suggest that Th cells must be capable of secreting significant IFN-γ to enhance IgG2 production, which is consistent with results for T-cell-independent assay systems (25).

The function of IL-4 in augmenting IgG2 and IgG1 responses may be to promote B-cell survival. Proliferation and IgG secretion by bovine B cells stimulated with CD40L-transfected mouse L cells was enhanced approximately 40% by IL-4 (32). We have recently found that Fas transcript levels are upregulated in bovine B cells activated by CD40 ligation (34). This observation coupled with the finding that the majority of Th cell clones coexpress Fas and FasL transcipts suggests the potential for these T cells to kill each other as well as activated Fas+ B cells (49, 62). As with bovine Th cells, FasL expression is not strictly limited to Th1 cells in the mouse; FasL+ Th0 and Th2, as well as Th1, cells were shown to kill autologous, Fas+ B cells (36, 55). Furthermore, IL-4 prevented Fas-induced apoptosis of CD40L-activated B cells (28, 43). Thus, our results are compatible with the possibility that IL-4 prevents either B-cell or T-cell-mediated apoptosis signaled via FasL-Fas interactions. IL-4 may also potentiate IgG production by enhancing the expression of B7 costimulatory molecules on B cells (52). These possibilities are currently under investigation.

As demonstrated earlier for B cells stimulated by T-independent means (25, 26), IL-2 occasionally enhanced IgG1 or IgG2 synthesis by B cells cocultured with Th cells and antigen (Table 3 and data not shown). This is likely due to its positive effects on T- and B-cell growth. IL-2 augments antigen-induced proliferation by Th cell clones, using either PBMC or B cells as APC (references 7 and 12 and data not shown). Furthermore, IL-2 supports the survival of murine germinal center B cells in culture (17) and proliferation of bovine peripheral blood B cells (59).

The ability of Th cell clones to promote IgG2 production by B cells in vitro also reflected the parasite antigen-specific IgG subclasses in the sera of B. bigemina RAP-1-immunized and F. hepatica-exposed cattle. These were composed of a mixed IgG1 and IgG2 response in the B. bigemina RAP-1-immunized animals and a restricted IgG1 response in two F. hepatica-infected cattle. The use of RIBI adjuvant containing monophosphoryl lipid A and trehalose dimycolate, which is reported to stimulate enhanced IgG2a responses in mice (60), may have stimulated IgG2 responses in the B. bigemina RAP-1-immunized calves (46). The restricted IgG1 response to F. hepatica infection also has been observed in cattle chronically infected with this parasite (19).

In summary, B. bigemina RAP-1- and F. hepatica-specific CD4+ T cells derived from cattle immune to these different parasites can function as helper cells. Importantly, the biological activity of the clones cultured in vitro is representative of the serum antibody responses in the same animals from which the Th cell clones were obtained. Furthermore, Th cells that coexpress IL-4 and IFN-γ (Th0 cells) apparently can provide the dual cytokine and costimulatory signals needed to promote enhanced B-cell synthesis of IgG1 and IgG2. The ability of B. bigemina RAP-1-specific Th cells to secrete IFN-γ and promote IgG2 production may be immunologically relevant, since protective mechanisms of immunity against babesiosis are hypothesized to involve clearance of parasitized erythrocytes and free merozoites by opsonizing antibody and activated macrophages (13, 44, 54).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bev Hunter, Kim Kegerreis, Ruguang Oh, Carla Robertson, and Daming Zhu for excellent technical assistance.

This research was supported by the USDA-BARD grant US-2496-94C and USDA NRICGP grants 93-37206-9657, 96-35204-3667, 96-35204-3584, and 97-35204-4513.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin C L, Iams K P, Brown W C, Grab D J. Theileria parva: CD4+ helper and cytotoxic T-cell clones react with a schizont-derived antigen associated with the surface of Theileria parva-infected lymphocytes. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90118-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, Briere F, Galizzi J P, van Kooten C, Liu Y J, Rousset F, Saeland S. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyer J C, Stich R W, Hoover D S, Brown W C, Cheevers W P. Cloning and expression of caprine interferon-gamma. Gene. 1998;210:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boom W H, Liano D, Abbas A K. Heterogeneity of helper/inducer T lymphocytes. II. Effects of interleukin-4- and interleukin-2-producing T cell clones on resting B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1352–1363. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, W. C. Unpublished observations.

- 7.Brown W C, Davis W C, Dobbelaere D A E, Rice-Ficht A C. CD4+ T-cell clones obtained from cattle chronically infected with Fasciola hepatica and specific for adult worm antigen express both unrestricted and Th2 cytokine profiles. Infect Immun. 1994;62:818–827. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.818-827.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown W C, Estes D M. Type I and type II responses in cattle and their regulation. In: Schijns V E C J, Horzinek M, editors. Cytokines in veterinary medicine. Wallingford, England: CAB International; 1997. pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown W C, Estes D M, Chantler S E, Kegerreis K A, Suarez C E. DNA and a CpG oligonucleotide derived from Babesia bovis are mitogenic for bovine B cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5423–5432. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5423-5432.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown W C, Logan K S, Wagner G G, Tetzlaff C L. Cell-mediated immune responses to Babesia bovis merozoite antigens in cattle following infection with tick-derived or cultured parasites. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2418–2426. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2418-2426.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown W C, McElwain T F, Hötzel I, Ruef B J, Rice-Ficht A C, Stich R W, Suarez C E, Estes D M, Palmer G H. Immunodominant T cell antigens and epitopes of Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1998;92:473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown W C, McElwain T F, Hötzel I, Suarez C E, Palmer G H. Helper T-cell epitopes encoded by the Babesia bigemina rap-1 gene family in the constant and variant domains are conserved among parasite strains. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1561–1569. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1561-1569.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown W C, Rice-Ficht A C. Use of helper T cells to identify potentially protective antigens of Babesia bovis. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown W C, Woods V M, Chitko-McKown C G, Hash S M, Rice-Ficht A C. Interleukin-10 is expressed by bovine type 1 helper, type 2 helper, and unrestricted parasite-specific T-cell clones, and inhibits proliferation of all three subsets in an accessory-cell-dependent manner. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4697–4708. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4697-4708.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown W C, Zhao S, Rice-Ficht A C, Logan K S, Woods V M. Bovine helper T-cell clones recognize five distinct epitopes on Babesia bovis merozoite antigens. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4364–4372. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4364-4372.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown W C, Zhu D, Shkap V, McGuire T C, Blouin TE F, Kocan K M, Palmer G H. The repertoire of Anaplasma marginale antigens recognized by CD4+ T-lymphocyte clones from protectively immunized cattle is diverse and includes major surface protein 2 (MSP-2) and MSP-3. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5414–5422. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5414-5422.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe J, Kim H-S, Zhang X, Armitage R J, Choi Y S. Cellular and molecular factors that regulate the differentiation and apoptosis of germinal center B cells. Anti-Ig down-regulates and inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 1996;157:1006–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark I A, Allison A C. Babesia microti and Plasmodium yoelii infections in nude mice. Nature. 1974;252:328–329. doi: 10.1038/252328a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clery D, Torgerson P, Mulcahy G. Immune responses of chronically infected adult cattle to Fasciola hepatica. Vet Parasitol. 1996;62:71–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00858-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degen J L, Neubauer M G, Degen S J, Seyfried C E, Morris D R. Regulation of protein synthesis in mitogen-activated bovine lymphocytes. Analysis of actin-specific and total mRNA accumulation and utilization. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12153–12162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Prete G F, De Carli M, Ricci M, Romaginini S. Helper activity for immunoglobulin synthesis of T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 human T cell clones: the help of Th1 clones is limited by their cytolytic capacity. J Exp Med. 1991;174:809–813. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Prete G, Maggi E, Parronchi P, Chretien I, Tiri A, Macchia D, Ricci M, Banchereau J, de Vries J, Romagnani S. IL-4 is an essential factor the IgE synthesis induced in vitro by human T cell clones and their supernatants. J Immunol. 1988;140:4193–4198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, Roncarolo M-G, te Velde A, Figdor C, Johnson K, Kastelein R, Yssel H, de Vries J E. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and vial IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis J A, Davis W C, MacHugh N D, Emery D L, Kaushal A, Morrison W I. Differentiation antigens in bovine mononuclear phagocytes identified by monoclonal antibodies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1988;19:325–340. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(88)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estes D M, Closser N M, Allen G K. IFN-γ stimulates IgG2 production from bovine B cells costimulated with anti-μ and mitogen. Cell Immunol. 1994;154:287–295. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Estes D M, Hirano A, Heussler V T, Dobbelaere D A E, Brown W C. Expression and biological activities of bovine interleukin 4: effects of recombinant bovine interleukin 4 on T cell proliferation and B cell differentiation and proliferation in vitro. Cell Immunol. 1995;163:268–279. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiorentino D F, Zlotnick A, Vieira P, Mosmann T R, Howard M, Moore K W, O’Garra A. IL-10 acts on the antigen-presenting cell to inhibit cytokine production by Th1 cells. J Immunol. 1991;146:3444–3451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foote L C, Howard R G, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rothstein T L. IL-4 induces Fas resistance in B cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:2749–2753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gajewski T F, Pinas M, Wong T, Fitch F W. Murine Th1 and Th2 clones proliferate optimally in response to distinct antigen-presenting cell populations. J Immunol. 1991;146:1750–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gajewski T F, Schell S R, Nau G, Fitch F W. Regulation of T-cell activation: differences among T-cell subsets. Immunol Rev. 1989;111:79–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. A central role of CD40 ligand in the regulation of CD4+ T-cell response. Immunol Today. 1996;17:410–414. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirano A, Brown W C, Estes D M. Cloning, expression, and biologic function of the bovine CD40 homologue. Role in B lymphocyte growth and differentiation in cattle. Immunology. 1997;90:294–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirano A, Brown W C, Trigona W, Tuo W, Estes D M. Kinetics of expression and subset distribution of the TNF superfamily members CD40 ligand and Fas ligand on T lymphocytes in cattle. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;61:251–263. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirano, A., D. M. Estes, and W. C. Brown. Unpublished observations.

- 35.Jacobs P, Radzioch D, Stevenson M M. A Th1-associated increase in tumor necrosis factor alpha expression in the spleen correlates with resistance to blood-stage malaria in mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:535–541. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.535-541.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ju S-T, Cui H, Panka D J, Ettinger R, Marshak-Rothstein A. Participation of target Fas protein in apoptosis pathway induced by CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4185–4189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy M K, Picha K S, Shanebeck K D, Anderson D M, Grabstein K H. Interleukin-12 regulates the proliferation of Th1, but not Th2 or Th0, clones. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2271–2278. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Killar L, MacDonald G, West J, Woods A, Bottomly K. Cloned, Ia-restricted T cells that do not produce interleukin 4 (IL 4)/B cell stimulatory factor 1 (BSF-1) fail to help antigen-specific B cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:1674–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McElwain T F, Perryman L E, Musoke A J, McGuire T C. Molecular characterization and immunogenicity of neutralization-sensitive Babesia bigemina merozoite surface proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;47:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGuire T C, Musoke A J, Kurtti T. Functional properties of bovine IgG1 and IgG2: interaction with complement, macrophages, neutrophils and skin. Immunology. 1979;38:249–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKeever D J, MacHugh N D, Goddeeris B M, Awino E, Morrison W I. Bovine afferent lymph veiled cells differ from blood monocytes in phenotype and accessory function. J Immunol. 1991;147:3703–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosmann T R, Cherwinski H, Bond M W, Gieldin M A, Coffman R L. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakanishi K, Matsui K, Kashiwamura S, Nishioka Y, Nomura J, Nishimura Y, Sakaguchi N, Yonehara S, Higashino K, Shinka S. IL-4 and anti-CD40 protect against Fas-mediated B cell apoptosis and induce B cell growth and differentiation. Int Immunol. 1996;8:791–798. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer G H, McElwain T F. Molecular basis for vaccine development against anaplasmosis and babesiosis. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:233–253. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03123-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parronchi P, Macchia D, Piccinni M-P, Biswas P, Simonelli C, Maggi E, Ricci M, Ansari A A, Romagnani S. Allergen- and bacterial antigen-specific T-cell clones established from atopic donors show a different profile of cytokine production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4538–4542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez S D, Palmer G H, McElwain T F, McGuire T C, Ruef B J, Chitko-McKown C G, Brown W C. CD4+ T-helper lymphocyte responses against Babesia bigemina rhoptry-associated protein 1. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2079–2087. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2079-2087.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruef B J, Rodriguez S D, Roussel A J, Palmer G H, McElwain T F, Chitko-McKown C G, Rice-Ficht A C, Brown W C. Immunization with Babesia bigemina rhoptry-associated protein 1 induces a type 1 cytokine response. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:45–54. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salgame P, Abrams J S, Clayberger C, Goldstein H, Convit J, Modlin R L, Bloom B R. Differing lymphokine profiles in functional subsets of human CD4 and CD8 T cell clones. Science. 1991;254:279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott D W, Grdina T, Shi Y. T cells commit suicide, but B cells are murdered! J Immunol. 1996;156:2352–2356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Severson C D, Burg D L, Lafrenz D E, Feldbush T L. An alternative method of panning for rat B lymphocytes. Immunol Lett. 1987;15:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(87)90130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snapper C M, Paul W E. Interferon-γ and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stack R M, Leschow D L, Gray G S, Bluestone J A, Fitch F W. IL-4 treatment of small, splenic B cells induces costimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2. J Immunol. 1994;152:5723–5733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevens T L, Bossie A, Sanders V M, Fernandez-Botran R, Coffman R L, Mosmann T R, Vitetta E S. Regulation of antibody isotype secretion by subsets of antigen-specific helper T cells. Nature. 1988;334:255–258. doi: 10.1038/334255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stich R W, Shoda L K M, Dreewes M, Adler-Frech B, Jungi T W, Brown W C. Stimulation of nitric oxide production by Babesia bovis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4130–4136. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4130-4136.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suda T, Okazaki T, Naito Y, Yokota T, Arai N, Ozaki S, Nagata S. Expression of the Fas ligand in cells of T cell lineage. J Immunol. 1995;154:3806–3813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor-Robinson A W. Regulation of immunity to malaria: valuable lessons learned from murine models. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:334–342. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor-Robinson A W, Phillips R S. B cells are required for the switch from Th1- to Th2-regulated immune responses to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2490–2498. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2490-2498.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor-Robinson A W, Phillips R S, Severn A, Moncada S, Liew F Y. The role of TH1 and TH2 cells in a rodent malaria infection. Science. 1993;260:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.8100366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trueblood E S, Brown W C, Palmer G H, Davis W C, Stone D M, McElwain T F. B-lymphocyte proliferation during bovine leukemia virus-induced persistent lymphocytosis is enhanced by T-lymphocyte-derived interleukin-2. J Virol. 1998;72:3169–3177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3169-3177.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ulrich J T, Meyers K R. Monophosphoryl lipid A as an adjuvant. In: Powell M F, Newman M J, editors. Vaccine design. The subunit and adjuvant approach. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 495–524. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Von der Weid T, Langhorne J. The roles of cytokines produced in the immune response to the erythrocytic stages of mouse malarias. Immunobiology. 1993;189:397–418. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoo J, Stone R T, Beattie C W. Cloning and characterization of bovine Fas. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:227–234. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]