ABSTRACT

Background: Experiencing potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) has been found to be significantly associated with poor mental health outcomes in military personnel/veterans. Currently, no manualised treatment for moral injury-related mental health difficulties for UK veterans exists. This article describes the design, methods and expected data collection of the Restore & Rebuild (R&R) protocol, which aims to develop procedures to treat moral injury related mental ill health informed by a codesign approach.

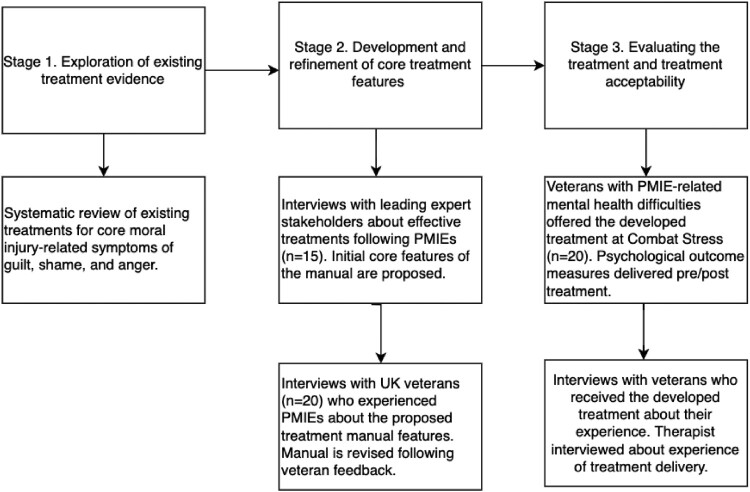

Methods: The study consists of three main stages. First, a systematic review will be conducted to understand the best treatments for the symptoms central to moral injury-related mental ill health (stage 1). Then the R&R manual will be co-designed with the support of UK veteran participants with lived experience of PMIEs as well as key stakeholders who have experience of supporting moral injury affected individuals (stage 2). The final stage of this study is to conduct a pilot study to explore the feasibility and acceptability of the R&R manual (stage 3).

Results: Qualitative data will be analysed using thematic analysis.

Conclusions: This study was approved by the King's College London's Research Ethics Committee (HR-20/21-20850). The findings will be disseminated in several ways, including publication in academic journals, a free training event and presentation at conferences. By providing information on veteran, stakeholder and clinician experiences, we anticipate that the findings will not only inform the development of an acceptable evidence-based approach for treating moral injury-related mental health problems, but they may also help to inform broader approaches to providing care to trauma exposed military veterans.

KEYWORDS: Moral injury, treatment, veteran, clinic, protocol, co-design

HIGHLIGHTS

No manualised treatment for UK veterans with moral injury-related mental health difficulties currently exists.

This protocol outlines the co-design process of the Restore & Rebuild (R&R) treatment.

R&R will be informed by a comprehensive review of existing research, interviews with international stakeholders, interviews with UK veterans & feedback from veteran patients who receive R&R.

Abstract

Antecedentes: Se ha encontrado que experimentar eventos potencialmente dañinos para la moral (PMIE, por sus siglas en inglés) se asocia significativamente con malos resultados de salud mental en el personal militar/veteranos. Actualmente no existe un tratamiento manualizado para los problemas de salud mental relacionadas con daño moral para los veteranos del Reino Unido. Este artículo describe el diseño, los métodos y la recopilación de datos esperada del protocolo Restore & Rebuild (R&R), que tiene como objetivo desarrollar procedimientos para tratar la salud mental relacionada con el daño moral informado por un enfoque de codiseño.

Métodos: El estudio consta de tres etapas principales. Primero, se realizará una revisión sistemática para comprender los mejores tratamientos para los síntomas centrales de la enfermedad mental relacionada con el daño moral (etapa 1). Luego, el manual de R&R se diseñará conjuntamente con el apoyo de participantes veteranos del Reino Unido con experiencia vivida de PMIE, así como con partes interesadas clave que tengan experiencia en el apoyo a las personas afectadas por daño moral (etapa 2). La etapa final de este estudio es realizar un estudio piloto para explorar la factibilidad y aceptabilidad del manual R&R (etapa 3).

Resultados: Los datos cualitativos se analizarán mediante análisis temático.

Conclusiones: Este estudio fue aprobado por el Comité de Ética en Investigación del King's College London (HR-20/21-20850). Los hallazgos se difundirán de varias maneras, incluida la publicación en revistas académicas, un evento de capacitación gratuito y presentaciones en conferencias. Al proporcionar información sobre las experiencias de veteranos, partes interesadas y médicos, anticipamos que los hallazgos no solo informarán el desarrollo de un enfoque basado en evidencia aceptable para tratar problemas de salud mental relacionados con daño moral, sino que también pueden ayudar a transmitir enfoques más amplios para proporcionar atención a veteranos militares expuestos a traumas.

PALABRAS LLAVE: Daño moral, Tratamiento, Veterano, Clínica, Protocolo, Co-diseño

Abstract

背景:已发现经历潜在道德伤害事件 (PMIE) 与军人/退伍军人的不良心理健康结果显著相关。目前,尚无针对英国退伍军人道德伤害相关心理健康困难的治疗手册。本文描述了恢复与重建 (R&R) 计划的设计、方法和预期数据收集,该计划旨在通过合作设计方法开发治疗道德伤害相关心理健康的流程。

方法:该研究包括三个主要阶段。首先,将进行系统综述,以了解与道德伤害相关的精神障碍核心症状的最佳治疗方法(第 1 阶段)。然后,将在具有 PMIE 亲身经历的英国老兵参与者以及具有支持受道德伤害影响者经验的利益相关者的支持下共同设计R&R 手册(第 2 阶段)。本研究的最后阶段是进行试点研究,以考查 R&R 手册的可行性和可接受性(第 3 阶段)。

结果:定性数据将使用主题分析进行分析。

结论:本研究得到了伦敦国王学院研究伦理委员会的批准(HR-20/21-20850)。研究结果将通过多种方式传播,包括在学术期刊上发表、免费培训活动和在会议中展示。通过提供有关退伍军人、利益相关者和临床医生经验的信息,我们预计这些发现不仅将为开发一种可接受的循证方法来治疗道德伤害相关心理健康问题提供信息,而且还可能有助于为创伤暴露老兵提供护理带来更多启发。

关键词: 道德伤害, 治疗, 老兵, 临床, 计划, 合作设计

1. Introduction

Moral injury may follow events which greatly transgress one's deeply held moral and ethical belief systems and frequently comprises of feelings of guilt, shame, disillusionment and anger (Atuel et al., 2021; Williamson et al., 2021). Potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) can be categorised into three distinct event types: acts of commission, omission or betrayal by a trusted other (Bryan et al., 2016). While it has been recognised that moral injury is experienced in civilian settings, currently the majority of literature on moral injury stems from experiences of military personnel (Griffin et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2018). In military personnel and veterans, an example of an act of commission could be guiding a bomb to a location which unintentionally leads to the wounding or killing of civilians in combat; or having to make clinical decisions with limited resources in a deployment theatre which leads to some patients dying who could have otherwise survived. An act of omission in a military context may be not being able to feed starving local children or protect them from violence due to rules of engagement. Finally, a PMIE involving betrayal may be experienced when a veteran perceives their injury results from being provided with inadequate battlefield safety equipment or they have been mistreated historically under policies that have now changed, such as being discharged for being gay or pregnant.

Moral injury may have profound effects on an individual's view of themselves and others, commonly describing a loss of identity or sense of self, as well as a mistrust of others, with a worldview they can no longer make sense of (Farnsworth, 2019; Yeterian et al., 2019) After experiencing PMIEs, people may question their identity in relation to previously held ‘just-world’ beliefs about good and bad people and how they define themselves within these measures (Farnsworth, 2019; Yeterian et al., 2019). The emotions described most frequently by veterans and other professionals are shame, guilt and anger as well as sadness, anxiety and disgust (Purcell et al., 2018; Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, Allen, et al., 2020). Moral injury has subsequently been significantly associated with symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, (Battles et al., 2018; Williamson et al., 2018) increased suicidality (Ames et al., 2019; Bryan et al., 2018; Williamson et al., 2018) and alcohol misuse (Battles et al., 2019; Hamrick et al., 2019). Furthermore, exposure to PMIE can significantly impact the family of the veteran and their occupational functioning; veterans describe withdrawal from loved ones, avoidance of disclosing the event, increased risk-taking behaviours and distrust of authority leading to wider social difficulties such as workplace relationships (Williamson et al., 2021a). Here, veterans described feelings of shame as being a barrier to relationships with their loved ones as well as feelings of guilt connecting with their family who are safe and healthy after witnessing devastation of families during deployment (Williamson et al., 2021a).

While individuals who experience what appear to be classically traumatic events, involving threats to self or others, may present with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), it is not uncommon for them also to report symptoms characteristic of moral injury (i.e. shame, guilt, worthlessness) if clinicians ask about them (Williamson et al., 2021b). However, there are some clear distinctions between PTSD and moral injury (Barnes et al., 2019). Those experiencing symptoms of moral-injury related trauma tend to have increased negative cognitions relating to self, self-blame, sadness and increased re-experiencing symptoms compared to those who have experienced life-threat traumas (Barnes et al., 2019; Litz et al., 2018). Those who have been exposed to PMIEs also have been found to have increased suicidality and rumination (Hamrick et al., 2019) in comparison to veterans without PMIE exposure. Moreover, large national studies of US veterans find, after controlling for trauma history, psychiatric history & demographic characteristics, those exposed to PMIEs are at increased risk of psychiatric symptoms than those not exposed (Wisco et al., 2017).

Cases of mental illness associated with moral injury can be challenging for clinical care teams to treat. Currently no manualised treatment for moral injury-related mental health difficulties exists and clinicians have reported considerable uncertainty about the best approach for managing patient symptoms (Currier et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2021b; Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, Jones, et al., 2020). For example, it has been argued that when exposure-based PTSD treatments are applied to those who have experienced PMIEs, it may be unhelpful – or even harmful – if insufficient attention is paid to the emotional processing of patient's symptoms of shame and guilt (Maguen & Burkman, 2013; Steinmetz & Gray, 2015). Equally, many evidence-based approaches for PTSD (e.g. trauma-focused CBT) utilise cognitive restructuring to update a patient's erroneous, maladaptive or distorted appraisals and replace them with more adaptive beliefs about the self or event. However, this may not be effective or appropriate in cases of moral injury where a patient's distress arises from PMIEs, including acts of perpetration, where appraisals of blame may be accurate or appropriate (Steinmetz & Gray, 2015). Finally, recent studies have found evidence of increased moral-injury related difficulties (e.g. shame, guilt, anger) amongst those who met criteria for Complex PTSD (CPTSD) exposed to PMIEs (Currier et al., 2021), with CPTSD presentations being associated with poorer treatment outcomes (Lonergan, 2014). Taken together, these findings highlight a clinical need for a manualised treatment that has been developed for the distinct needs of those who have experienced PMIEs, which may not currently be being met through existing PTSD treatment approaches.

The lack of a manualised treatment, lower clinician confidence in treating cases of moral injury (Phelps et al., 2022; Williamson et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2021b) and the significant associations found between PMIE exposure and suicidality suggests that moral injury may represent an important public health concern. Whilst there is some early evidence of potential treatments for moral injury related mental health difficulties in the USA, such as ‘The Impact of Killing’ treatment (Maguen et al., 2017; Purcell et al., 2018). This treatment is thought to be beneficial by helping veterans to acknowledge their distress and increase feelings of acceptance and forgiveness, whilst also addressing spiritual dimensions (Maguen et al., 2017; Purcell et al., 2018). However, ‘Impact of Killing’ focuses primarily on acts of perpetration (i.e. killing in war) and wouldn't target the range of PMIEs that UK veterans have been found to be exposed to (i.e. acts of omission or betrayal). Another proposed treatment, Adaptive Disclosure (Gray et al., 2012) has also been developed to treat moral injury in US veterans which considers a wider range of PMIEs. Evidence suggests that Adaptive Disclosure can be effective for those who suffer from MI-related difficulties (Litz et al., 2017), but this treatment was developed for, and currently has only been delivered to small numbers of US military populations (Gray et al., 2012). Studies have shown there are key differences in trauma exposure and resultant mental health difficulties between UK and US militaries (Castro & Hall, 2021; Fear et al., 2010; Malcolm et al., 2015; Sundin et al., 2014). US and UK troops can have different approaches to how they conduct themselves on deployment (Fear et al., 2010; Sundin et al., 2014) making translating a US approach to a UK context challenging, suggesting that a treatment which considers the needs of UK personnel/veterans could be beneficial.

Developing a treatment for UK veterans who have experienced moral injury that is acceptable and well tolerated represents a number of challenges. First, the very nature of PMIEs and resulting symptoms of shame and guilt may make accessing and engaging in treatment particularly challenging for patients. UK veterans also have higher rates of treatment drop out, lower engagement and higher rates of relapse compared to the general population rates (Kitchiner et al., 2012). A frequently reported reason for veteran treatment drop-out is a belief that their unique military experiences and trauma exposure cannot be understood by a civilian treatment centre (Weiss & Coll, 2011).

One approach often used in healthcare service design and development is ‘codesign’, where the lived experiences and knowledge of service users themselves are incorporated to enhance the quality and experiences of care. Codesign aims to develop a detailed understanding of how key stakeholders and service users perceive and experience the look, feel, processes and structures of a service (Yeterian et al., 2019; Dimopoulos-Bick et al., 2019). By engaging stakeholders and service users in codesigning a service, this is argued to result in better care and improved service performance by emphasising individual's subjective experiences at various stages in the care pathway which, in turn, may lead to improvements in health outcomes and more efficient use of limited healthcare resources (Yeterian et al., 2019; Dimopoulos-Bick et al., 2019). Given the increased awareness of the exposure and deleterious impact experiences of PMIE can have on veteran wellbeing, an acceptable treatment that helps veterans process and manage symptoms characteristic of moral injury, improves daily functioning and repairs veterans’ relationships with themselves and others is urgently needed. The Rebuild and Restore (R&R) study will develop procedures to treat moral injury related mental health informed by a codesign approach. This article describes the R&R codesign protocol. Data collection for this study will take place between October 2021 and November 2022. The codesigned procedures will be evaluated in a subsequent feasibility pilot study and, if indicated, a randomised control trial.

2. Method

This protocol and its associated procedures were approved by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (HR-20/21-20850).

2.1. Study design

The purpose of this project will be to develop a manualised treatment for UK veterans experiencing moral injury-related mental ill health characterised as a ‘moral injury’ following exposure to a PMIE. The project will have three main stages. The first of these is to conduct a systematic review to understand the best treatments for the symptoms central to moral injury-related mental ill health. The second stage is to co-design the intervention with the support of veteran participants with lived experience of PMIEs as well as key stakeholders, including clinicians and members of the clergy who have been involved with supporting moral injury affected individuals. The final stage of this study will be to conduct a pilot study to explore the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention we developed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the co-design process for developing the R&R treatment manual. Note: PMIEs = potentially morally injurious events.

Several of the key elements of the treatment will be specified in advance of the codesign work based on the existing empirical literature on moral injury and consultation with clinicians working at a national mental health charity in the UK that provides clinical services to veterans with complex mental health needs (Combat Stress, 2021). Specifically, it was pre-specified that veteran exposure to PMIE would be assessed by screening questionnaires and by clinicians conducting the veteran patient's initial assessment, which takes place when a patient is referred for psychological support. As the trial will be run during the course of COVID-19 social distancing restrictions, it was prespecified that treatment would take place with a therapist on a one-to-one basis using an online video consultation platform (i.e. MS Teams). The one-to-one online method of delivery was agreed as it has the potential to overcome many of the barriers to care detailed above, such as veterans’ feelings of shame and guilt surrounding the PMIE which might potentially prevent disclosure and discussion in a group therapy setting. It was also prespecified that the therapist will be a CBT practitioner. CBT practitioners are postgraduate psychological therapists who have received specific (12 months) training in the delivery of psychological therapies to patients who have difficulties with anxiety, depression, PTSD and suicidality. The therapist will be based within a mental health setting (Combat Stress, 2021) where they can offer rapid access to other manualised psychological therapies and have access to an interdisciplinary team, should the developed R&R manual prove ineffective. Participants will then be followed up three months after completing treatment to monitor treatment outcomes.

In parallel to this research, we are working on refining a measure for screening for moral injury event exposure and event-related distress (Moral Injury scale [MORIS], (Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, et al., 2020)). In the interim, to screen veteran patients for PMIE exposure and associated distress, exposure will be determined via clinician rating during the patient's initial assessment for treatment at Combat Stress. Following a detailed clinical assessment, the details of veterans who express symptoms of moral injury related mental health difficulties will be forwarded onto treatment therapist for review. Following review of the completed assessment, the therapist will contact the veteran to discuss the pilot and through discussion of moral injury, will obtain confirmation from the veteran that moral injury appears to be their main presenting difficulty. Following this screening outcome measures will be sent to the veteran including validated questionnaire measure of military moral injury (Expressions of Moral Injury measure EMIS, Currier et al., 2015). This approach was based on feedback from Combat Stress that the use of questionnaires and clinician assessment is standard practice on referral to Combat Stress and would fit well with their existing procedures.

We will use a mixed-method codesign process to determine what aspects the intervention treatment manual should include, how the treatment should be presented to prospective patients, and by whom, and to address any important considerations to optimise accessibility of, and engagement with the treatment.

The codesign process of the treatment manual will consist of three stages (see Figure 1). Stage 1 will involve an initial systematic review of the existing literature about effective treatment approaches for managing core symptoms thought to be associated with PMIE exposure, namely guilt, shame and anger (Seforti et al., under review). This review will be followed by scoping interviews with leading world expert stakeholders to explore their experience and beliefs about treating moral injury-related distress (Stage 2). The stakeholder interviews, coupled with the results of the systematic review, will inform the development of the initial core features of the manual (Stage 2). Interviews will also be conducted with UK veterans who experienced PMIEs, with their feedback sought on the proposed core features of the manual and how it compares to their previous experiences of treatment (Stage 2). The manual will be further revised and refined following veterans’ feedback (Stage 2) and then delivered to veteran patients who are experiencing moral injury-related distress at Combat Stress (Stage 3). Psychological outcome measures will be administered pre/post treatment, as well as at multiple time points throughout the treatment, to assess the effectiveness of the developed treatment manual in reducing veteran symptoms of PTSD, depression, alcohol misuse and expressions of moral injury (e.g. symptoms of guilt, shame, anger). These veteran patients will also be invited to provide their feedback on their experience of receiving the developed treatment with further amendments made to the manual where necessary (Stage 3). Feedback from any veteran patients who drop out of treatment will also be sought to ensure any barriers to engagement are captured (Stage 3). The therapist who delivers the treatment manual will also be interviewed about their views of the manual in the first six months of the trial and on trial completion (Stage 3).

2.2. Patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE)

Involvement from veterans, clinicians, leading experts in the field of moral injury and wider stakeholders informed the development of this protocol, the prespecified elements of the pathway, and will contribute throughout the delivery of the codesign project. At the protocol development stage, consultation was carried out with veterans with lived experience, leading experts and representatives from key policy and practitioner organisations. Examples of decisions that were made on the basis of this consultation include specifically focusing recruitment on veterans who were seeking psychological treatment from Combat Stress on the basis that Combat Stress is a well-established organisation for providing mental health treatment to trauma exposed veterans, and this setting will allow for rapid delivery of alternative validated treatments should the developed treatment be poorly tolerated by patients.

Throughout the codesign process, we will conduct PPIE and consult with external stakeholders in the following ways: (1) five clinical psychologists and one psychiatrist with experience of treating military and civilian patients exposed to PMIEs, and two chaplains who provide pastoral support to the UK AF, who are independent from the research team will contribute to the manual development decisions made at a strategic level. (2) This dedicated stakeholder group will meet regularly to review manual procedures data and to make decisions to address how to solve key issues and manage potentially conflicting points of view that have emerged through the codesign process.

2.3. Codesign participants

Participants will include leading professional stakeholders in the field of moral injury (Stage 2), UK AF veteran participants (Stage 2), and veteran patients who will receive the developed treatment from Combat Stress (Stage 3). Expected recruitment numbers for each group are detailed in Table 1 and final numbers will be informed by assessing the range of views represented in the sample and the data provided by participants.

Table 1.

Recruitment estimates.

| Expert professional stakeholders | Veteran participants | Veteran patients | Therapist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1. Exploration of existing evidence | ||||

| Stage 2. Development and refinement of core treatment features | 15 | 20 | ||

| Stage 3. Evaluating the treatment and treatment acceptability | 20 | 1 |

Note: The veteran participants are participants who were interviewed about their views on the treatment features that had been developed in Stage 2. These participants will not be offered the developed treatment from Combat Stress (Stage 3).

2.4. Participant recruitment and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Stage One. As Stage one consists of a systematic review, no participants will be recruited for this stage of the project.

Stage Two. To recruit expert professional stakeholders with a wide range of perspectives to Stage two, we will circulate study advertisements within organisations that provide mental health treatment to UK AF personnel/veterans, as well as via mailing lists and social media. Contact details of leading professionals in the field of moral injury will be sought from relevant moral injury publications, with emails sent inviting the individual for an interview. Participating expert professional stakeholders will also be asked to share the study with potentially eligible colleagues. The 15 expert professional stakeholders will be eligible to participate if they have experience of either providing clinical treatment or another form of support (e.g. chaplaincy support) to service personnel, veterans or civilians who have experienced moral injury. Alternatively, expert professional stakeholders must have experience of carrying out evidence-based moral injury research published in academic journals. No limitation on expert professional stakeholder eligibility will be imposed according to demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, etc.) or professional grade, rank or qualification (e.g. PhD, clinical psychologist, psychiatrist, etc.) will be imposed. This inclusive strategy will ensure we collect rich data from a range of professionals with diverse knowledge of moral injury and military mental health.

To recruit UK AF veterans to Stage two interviews, a similar process will be followed in that study advertisements will be shared via mailing lists, social media and in veteran-affiliated newsletters. Participating veterans in Stage two will also be asked to share the study with potentially eligible veterans. Veterans will be eligible to participate if they are UK AF veterans, with self-report questions administered in an attempt to ensure this is the case. Self-report questions will also be issued to examine whether UK AF veterans experienced military-related moral injury (e.g. ‘during your military service, did you ever experience an event that was a serious challenge to your sense of who you are, your sense of the world, or your sense of right and wrong?’) as well as a standardised questionnaire measure of moral injury (see psychometric assessments section below). The inclusion of veterans who self-report experiencing a moral injury will ensure that the information they provide will meaningfully inform the moral injury treatment manual development. Participants will not be excluded by self-reported demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, rank). Further, we will not restrict participation by self-reported deployment location or AF service branch. We will exclude veteran participants who are not aged 18 years or more, who do not self-report experiencing a moral injury; have speech or hearing difficulties or are unwilling to provide informed consent.

All participants in Stage two will be required to give verbal (audio-recorded) consent.

Stage Three. To recruit veteran patients (Stage three) to the pilot of the treatment manual, veterans who have expressed moral injury as their main presenting difficulty during their clinical assessment will have their details forwarded onto the pilot therapist for further screening. Following the screening of assessment notes, the therapist will conduct a screening call with the veteran to discuss moral injury, the veterans’ current difficulties and the treatment pilot. In doing so, confirmation of treatment suitability can be obtained and initial potential barriers to treatment can be addressed. A minimum of 20 veteran patients will be recruited to receive the developed treatment manual. To receive the treatment, participants must be UK AF veterans who are engaged with the mental health charity for treatment. Participant moral injury will be determined via clinician rating as well as a questionnaire measure of moral injury (EMIS; Currier et al., 2015). In line with inclusion/exclusion criteria for veterans in Stage two, veteran patients in Stage three will not be excluded by self-reported demographic criteria (e.g. gender, rank, age), AF branch or deployment location. Veteran patients will be excluded if they are not aged 18 years or more; do not have moral injury-related mental health problems as determined by their assessing clinician; have speech or hearing difficulties; are not proficient in English; or are unwilling to provide informed consent. Veteran patients will also be excluded if they have active self-harm or suicidal ideation; if they completed an alternative treatment within the last three months; if they have planned concurrent additional treatment; severe psychotic disorder, dissociative identity or other severe mental health disorder (identified by previous diagnosis; serious cognitive impairment; concurrent significant life stressors that impairs ability to engage in therapy at this time (i.e. homelessness, currently in court case etc.; or current alcohol or drug abuse disorder)).

To recruit veteran patients to the acceptability interviews (Stage three), veteran patients will be contacted at various stages of the treatment process and invited to an interview about their experiences of treatment. For example, up to 10 patients will be recruited to interviews within their first ten sessions of treatment. Veteran patients will be interviewed by a member of the research team not affiliated with Combat Stress and informed that the information they provide will be held confidentially and will not be reported back to the Combat Stress therapist unless the patient disclosed a risk of harming themselves or others. All veteran patients will provide written consent prior to participation in the trial and study interviews.

2.5. Procedure

We will collect data and analyse at three stages to inform the treatment manual development. We will follow the Medical Research Council's guidance on the development of complex interventions (Craig et al., 2008; O’Cathain et al., 2019).

Stage One. In line with MRC guidance for complex intervention development (Craig et al., 2008; O’Cathain et al., 2019) we will begin by reviewing published evidence to identify existing interventions for the core symptoms associated with experiences of PMIEs, specifically guilt, shame and anger. This will offer insight into existing effective – as well as ineffective – interventions. The review will provide an understanding of what causal factors or existing intervention components that have the greatest scope for producing patient symptom change and provide an evidence base for intervention components that may be included in the developed treatment manual (O’Cathain et al., 2019).

Stage Two. Building on the results of the Stage 1 systematic review, we will conduct one-to-one interviews with leading professional stakeholders in the field of moral injury. These interviews will generate insight about the content, format and delivery of the treatment manual. Interviews will explore participants views about: the core challenges faced in providing support or treatment to individuals with moral injury-related mental health problems; the support or treatments currently available in cases of moral injury; and features of existing support or treatments that may help or hinder psychological recovery. Interviews will be conducted remotely via telephone or video conferencing (e.g. MS Teams), audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. These data will be used to develop a detailed prototype of the manual to be developed further and tested.

One-to-one in-depth interviews will also be conducted with veterans who have experienced military-related PMIEs. Interview questions will draw on questioning techniques informed by the Critical Incident Approach (Butterfield et al., 2005) to explore veterans’ perceptions of the psychological difficulties faced by those who experience PMIEs; features of previous treatments that have helped/hindered their recovery; and aspects of the developed manual that may facilitate or inhibit a positive experience or which might have been overlooked by the research team altogether. During the interview, veteran participants will be shown a visual representation of different aspects of the manual's proposed core components, developed from the findings of Stage 1 and the interviews conducted with professional stakeholders. Veteran participants will be asked to discuss their thoughts, feelings and concerns with questions including ‘What would be the best way to do this?’, ‘What might need to be done to support this part happening?’, ‘and ‘Do you have any concerns about this part of the treatment?’. Visual representations of the manual aspects will be shown to participants via screenshare (e.g. MS Teams) or sent via email/post for telephone interviews. Interviews will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Following an iterative process, these data will be used to refine and optimise the initial manual prototype. The dedicated stakeholder group (see PPIE section above) will be consulted at key decision-making points in the process to generate solutions to problems raised or inconsistent messages elicited from the Stage two interviews.

Stage Three. The CBT therapist will receive training in the concept of moral injury, PMIEs and delivering the treatment manual prototype developed across Stages one and two. The manual will be delivered to eligible veterans seeking mental health treatment following PMIEs at Combat Stress. The therapist will coordinate recruitment efforts, such as circulating study information at weekly Combat Stress Inter-disciplinary Team (MDT) meetings. Treatment delivery will be closely monitored for manual adherence during clinical supervision.

2.5.1. Psychometric assessments

During Stage three, we will quantitatively examine manual treatment outcomes, including the proportion of veteran patients who screen as eligible for the treatment, the number of eligible veteran patients who take up the treatment, the number of veteran patients who withdraw and symptom improvement rates. Therapist time required for treatment sessions will also be measured for cost effectiveness.

To measure if treatment benefits are maintained over time, patients will be followed up at three-months post-treatment. To ensure no patient gets significantly worse during the treatment, we will record patient scores on the Short-Form PCL-5 (Zuromski et al., 2019) and the Clinical Global Impression rating (Guy, 1976) at the start of every session. Patients will also be asked to complete the PCL-5 (Zuromski et al., 2019) measuring symptoms of PTSD, the AUDIT (Babor et al., 2001) measuring alcohol intake, the MORIS (Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, et al., 2020) and EMIS(Currier et al., 2015) measuring moral injury exposure and related symptoms and the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001a) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Pre/post treatment psychometric measures.

| Measures | Baseline | Session 19 | Post-treatment | 3-months post-treatment | Every session |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-5 | X | X | X | X | |

| AUDIT | X | X | X | ||

| MORIS | X | X | X | ||

| EMIS | X | X | X | ||

| PHQ-9 | X | X | X | X | |

| Short-Form PCL-5 | X | ||||

| CGI | X |

Note: PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) with Criterion A (Zuromski et al., 2019), AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 2001), MORIS = Moral Injury Scale (Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, et al., 2020) EMIS = expressions of moral injury (Currier et al., 2015), PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., 2001b), CGI = Clinical Global Impressions rating (Guy, 1976).

2.5.2. Qualitative assessments

To understand how acceptable and well tolerated the administered treatment manual is, qualitative interviews will be conducted with veteran patients and the therapist. We will carry out interviews with participating veteran patients who engaged with and completed the treatment sessions, and with any patients who withdraw. Veteran patients will be interviewed at varying points of treatment, with some interviewed early on during the treatment process, others midway through or at the end of treatment, others post-treatment at the three month follow up. Interviews will focus on how the treatment was experienced, what aspects work well, and what patients found both helpful and challenging. The therapist will be interviewed about their experience of delivering the manual in the first six months of manual delivery, as well as at the end of treatment. These data will provide an in-depth understanding of the context in which the manual will operate, the needs which have been met (or not) by the developed manual prototype, as well any unintended consequences or potential harms, and will be used to further refine the manual.

2.6. Data analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative data analysis

In Stage three, demographic characteristics and military history will be explored. Random slope non-linear growth models with a fixed coefficient of time squared will be fitted to explore the longitudinal health and functional impairment data collected at pre-treatment, end of treatment and three-month follow-up. These analyses will be repeated and adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics. The final stage of the analysis assessed whether the secondary outcomes collected at pre-treatment are predictors of PTSD (PCL-5) (Zuromski et al., 2019) and moral injury (EMIS) (Currier et al., 2015) severity scores at three-month follow-up. This will be done by fitting multivariate linear regression models to assess for predictors in changes between pre-treatment and three-month follow-up PCL-5 and EMIS scores.

2.6.2. Qualitative data analysis

Interviews (Stages 2 and 3) will be analysed using two procedures: ‘fast and direct’ and ‘in-depth and detailed’. The ‘fast and direct’ analysis will use written summaries of the interviews to collate core themes and provide readily understandable feedback about the manual. This approach will provide immediate feedback about the manual. The ‘in-depth and detailed’ analysis will utilise a thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) where interview data are preliminary coded using an inductive ‘bottom up’ approach. The ‘in-depth and detailed’ analysis process will provide nuanced feedback about the acceptability and feasibility of the manual to fine-tune the final iteration. This analysis will capture areas of disagreement that may be missed in the ‘fast and direct’ analysis. Credibility will be checked via analytic triangulation using reflective discussions with co-authors.

2.7. Ethics and dissemination

This study has received ethical approval from King's College London Research Ethics Committee (HR-20/21-20850). There are a number of ethical concerns that have been considered when developing the study protocol. Firstly, the potential for this novel treatment to cause further psychological distress and a worsening of symptoms. During treatment sessions participants will be required to recount and focus on PMIEs from their time in the military. Finding ways to successfully approach these events and manage the associated distress is a key feature of the protocol, but this could also potentially be detrimental for participants (Maguen & Burkman, 2013). Whilst the treatment manual has been developed collaboratively with experts, veterans and taking into account previous research and findings, it has not been previously delivered to a clinical population. To address this concern, throughout the delivery of the R&R treatment, the emerging data will be closely monitored by the study team. The therapist will also receive close clinical supervision and have the support of a multi-disciplinary team of clinicians, experienced in working with military veterans, who can quickly provide alternative treatment options if necessary.

There is also the possibility that participants may disclose events that are illegal or violate the military rules of engagement. In such circumstances these events may require confidentiality to be breached and events reported accordingly to the relevant authorities. To mitigate against any potential harm or distress this could cause, all participants will be fully informed of the therapist's need to disclose any illegality prior to participating. The therapist will also have full access to an experienced clinical team and supervisor to discuss any potential disclosures (Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, Jones, et al., 2020).

The results of the study are expected to have national and international interest for researchers, professionals and clinicians who work with veterans and other groups known to be vulnerable to moral injury. The findings will be disseminated via a free event which will be made available to all relevant stakeholders and UK clinicians delivering trauma-related psychological treatment. This event will be delivered in collaboration with the UK Psychological Trauma Society (UK PTS). The study may also lead to a further randomised control trial, should this be indicated by the findings.

3. Discussion

It has been identified that exposure to PMIEs can have a profound impact on mental health (Griffin et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2021c). The cost of moral injury is often seen in the impact it has not only on veterans, but also on the wider family unit, as occupational functioning declines and observable increased risk-taking and wider social difficulties are evident (Williamson et al., 2021a; Williamson, Murphy, Stevelink, Allen, et al., 2020). Those with a moral injury may present with changes to how they view themselves, the world and others, and report intense emotions such as shame, guilt, anger, sadness, and disgust (Yeterian et al., 2019). Developing moral injuries is significantly associated with psychiatric comorbidities including PTSD, depression, anxiety, increased suicidality and alcohol misuse (Bryan et al., 2018; Currier et al., 2021; Hamrick et al., 2019). It therefore presents as an important public health concern.

Currently there is no manualised treatment for moral injury and its related mental health difficulties. Clinicians working in the field report a lack of confidence and uncertainty in treating individuals with this presentation (Steinmetz & Gray, 2015; Williamson et al., 2021b). It is unclear whether existing treatments for PTSD, which commonly draw on CBT principles and techniques, are effective; particularly where the PMIE is an act of perpetration and appraisals of blame may be accurate (Steinmetz & Gray, 2015). Recent studies found evidence for increased moral injury-related symptoms in those with CPTSD, a clinical group associated with poorer treatment outcomes (Currier et al., 2021), which may help to further explain the difficulty care teams report when applying existing therapeutic methods. Where the needs of veterans presenting with moral injury may not be being met through existing PTSD treatment approaches, an effective manualised treatment for moral injury is clearly needed.

To address this gap, the aim of the present article is to detail the protocol for the development of a manualised treatment for UK veterans with psychological distress characterised as moral injury. Previously developed treatments for moral injury have focused on US military populations (Litz et al., 2017; Maguen et al., 2017) which have been shown to differ from UK personnel in terms of trauma exposure and resulting mental health problems (Sundin et al., 2014), highlighting the potential benefit of developing a treatment specifically with UK personnel/veterans. The codesign approach to this study is a strength that will allow for a detailed understanding of the presenting difficulties of UK veterans, who are experiencing mental health problems because of PMIEs, to be incorporated into the development and delivery of the treatment. This may help to reduce the associated difficulties this population face when trying to engage with mental health treatment, that commonly results in lower engagement and high drop-out rates (Kitchiner et al., 2012; Weiss & Coll, 2011). The study will lead to the development of the first manualised moral injury treatment for a UK veteran population that has been codesigned with the intended clinical population and stakeholders in an effort to overcome these barriers.

There are several limitations to this study protocol which need to be considered. Most prominent is the difficulty that is widely faced when assessing for and measuring moral injury. Currently there is no validated screening measure for moral injury related distress and/or associated cut off scores for clinical presentations for UK military veterans. This study will therefore rely on the clinical judgement of both the assessing clinician and treating therapist to determine that moral injury is the primary presenting difficulty. This may impact on the reliability during the pilot phase of the study.

The sample will be recruited from a national mental health charity in the UK and participants are required to volunteer to this novel study and ‘opt in’ to provide consent. As such, the views of a more diverse population may not be captured, and the sample may not be representative of all veterans who have a moral injury related mental health difficulty. This could limit the generalisability of the findings. Recruiting through a mental health charity does however bring with it the benefit of being able to validate the mental health status of participants. All participants will have been assessed by experienced clinicians in the field of veteran mental health and considered to have mental health difficulties pertaining to experiences during their military service which will improve the validity of the sample.

A final consideration is the method of treatment delivery. Delivering the treatment through an online video consultation platform may inadvertently exclude individuals who would have otherwise taken part. Whilst this decision is preferable during the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing restrictions, individuals without internet access and a method of conducting video calls may not be able to take part due to the method of delivery. With these potential limitations in mind, it is our intention that this study will collaboratively create a manualised treatment to care for veterans who have psychological problems following experiences of military related PMIEs, informed by veterans themselves, clinicians, chaplains and other stakeholders, that will ultimately improve access to effective treatment and support.

Funding Statement

Forces in Mind Trust.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ames, D., Erickson, Z., Nagy, A. Y., Youssef, N. A., Arnold, I., Adamson, C. S., Sones, A. C., Yin, J., Haynes, K., Volk, F., Teng, E. J., Oliver, J. P., & Koenig, H. G. (2019). Moral injury, religiosity, and suicide risk in U.S. veterans and active duty military with PTSD symptoms. Military Medicine, 184(3-4), 271–278. 10.1093/milmed/usy148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atuel, H. R., Barr, N., Jones, E., Greenberg, N., Williamson, V., Schumacher, M. R., Vermetten, E., Jetly, R., & Castro, C. A. (2021). Understanding moral injury from a character domain perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 41(3), 155–173. 10.1037/teo0000161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., & Monteiro, M. G. (2001). The alcohol use disorders identification test (pp. 1-37). Geneva: World. 10.1177/0269881110393051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, H. A., Hurley, R. A., & Taber, K. H. (2019). Moral injury and PTSD: Often co-occurring yet mechanistically different. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 31(2), A4–103. 10.1176/APPI.NEUROPSYCH.19020036/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/APPI.NEUROPSYCH.19020036F3.JPEG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battles, A. R., Bravo, A. J., Kelley, M. L., White, T. D., Braitman, A. L., & Hamrick, H. C. (2018). Moral injury and PTSD as mediators of the associations between morally injurious experiences and mental health and substance use. Traumatology, 24(4), 246–254. 10.1037/trm0000153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battles, A. R., Kelley, M. L., Jinkerson, J. D., C. Hamrick, H., & F. Hollis, B. (2019). Associations among exposure to potentially morally injurious experiences, spiritual injury, and alcohol use Among combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 405–413. 10.1002/jts.22404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Bryan, A. B. O., Roberge, E., Leifker, F. R., & Rozek, D. C. (2018). Moral injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidal behavior among national guard personnel. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(1), 36–45. 10.1037/TRA0000290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Bryan, A. O., Anestis, M. D., Green, B. A., Etienne, N., Morrow, C. E., & Ray-Sannerud, B. (2016). Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment, 23(5), 557–570. 10.1177/1073191115590855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, L. D., Borgen, W. A., Amundson, N. E., & Maglio, A.-S. T. (2005). Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954-2004 and beyond. Qualitative Research, 5(4), 475–497. 10.1177/1468794105056924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, C., & Hall, J. K. (2021). Post-traumatic stress disorder in UK and US forces deployed to Iraq Cite this paper. Retrieved 22 September, 2022, from www.thelancet.com. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Combat Stress . (2021). Mental health services for veterans | Combat Stress. 2022. Retrieved 23 September, 2020 from https://combatstress.org.uk/.

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 337(jul24 3), 979–983. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier, J. M., Drescher, K. D., & Nieuwsma, J. (2020). Future directions for addressing moral injury in clinical practice: Concluding comments. Addressing Moral Injury in Clinical Practice, 27(1), 61–68. 10.1037/0000204-015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Currier, J. M., Foster, J. D., Karatzias, T., & Murphy, D. (2021). Moral injury and ICD-11 complex PTSD (CPTSD) symptoms among treatment-seeking veterans in the United Kingdom. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(4), 417–421. 10.1037/TRA0000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., Drescher, K., & Foy, D. (2015). Initial psychometric evaluation of the moral injury questionnaire-military version. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(1), 54–63. 10.1002/cpp.1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos-Bick, D. P., Maher, L., Dawda, P., Verma, R., & Palmer, V. (2019). Experience-based co-design: Tackling common challenges. The Journal of Health Design, 3(1), 86–93. Retrieved 15 September, 2020 from https://www.journalofhealthdesign.com/JHD/article/view/46. 10.21853/JHD.2018.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth, J. K. (2019). Is and ought: Descriptive and prescriptive cognitions in military-related moral injury. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 373–381. 10.1002/JTS.22356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fear, N. T., Jones, M., Murphy, D., Hull, L., Iversen, A. C., Coker, B., Machell, L., Sundin, J., Woodhead, C., Greenberg, N., Landau, S., Dandeker, C., Rona, R. J., Hotopf, M., & Wessely, S. (2010). What are the consequences of deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the mental health of the UK armed forces? A cohort study The Lancet, 375(9728), 1783–1797. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60672-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. J., Schorr, Y., Nash, W., Lebowitz, L., Amidon, A., Lansing, A., Maglione, M., Lang, A. J., & Litz, B. T. (2012). Adaptive disclosure: An open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members with combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 407–415. 10.1016/J.BETH.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, B. J., Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Litz, B. T., Bryan, C. J., Schmitz, M., Villierme, C., Walsh, J., & Maguen, S. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 350–362. 10.1002/JTS.22362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy, W. (1976). The Clinical Global Impresssion Scale.

- Hamrick, H. C., Kelley, M. L., & Bravo, A. J. (2019). Military behavioral health morally injurious events, moral injury, and suicidality among recent-era veterans: The moderating effects of rumination and mindfulness. Military Behavioral Health, 8, 109–120. 10.1080/21635781.2019.1669509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchiner, N. J., Roberts, N. P., Wilcox, D., & Bisson, J. I. (2012). Systematic review and meta-analyses of psychosocial interventions for veterans of the military. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 19267. 10.3402/EJPT.V3I0.19267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001a). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001b). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/J.1525-1497.2001.016009606.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Contractor, A. A., Rhodes, C., Dondanville, K. A., Jordan, A. H., Resick, P. A., Foa, E. B., Young-McCaughan, S., Mintz, J., Yarvis, J. S., & Peterson, A. L. (2018). Distinct trauma types in military service members seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 286–295. 10.1002/jts.22276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Lebowitz, L., Gray, M. J., & Nash, W. P. (2017). Adaptive Disclosure: A new Treatment for Military Trauma, Loss, and Moral Injury. The Guildford Press. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=w20sDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Adaptive+Disclosure%3B+Litz+et+al.,+2017&ots=PuKBQC8yBg&sig=Pm54_VyKSnadr80KdsrIhvgEiK4#v=onepage&q=Adaptive%20Disclosure%3B%20Litz%20et%20al.%2C%202017&f=false. [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan, M. (2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD: The role of complex PTSD on treatment outcome. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 23(5), 494–512. 10.1080/10926771.2014.904467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen, S., & Burkman, K. (2013). Combat-Related killing: Expanding evidence-based treatments for PTSD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(4), 476–479. 10.1016/J.CBPRA.2013.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen, S., Burkman, K., Madden, E., Dinh, J., Bosch, J., Keyser, J., Schmitz, M., & Neylan, T. C. (2017). Impact of killing in war: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(9), 997–1012. 10.1002/jclp.22471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, E., Stevelink, S. A. M., & Fear, N. T. (2015). Care pathways for UK and US service personnel who are visually impaired. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 161(2), 116–120. 10.1136/jramc-2014-000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Cathain, A., Croot, L., Duncan, E., Rousseau, N., Sworn, K., Turner, K. M., … & Hoddinott, P.. 2019. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare Communication, BMJ open, 9(8), e029954. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, A. J., Adler, A. B., Belanger, S. A. H., Bennett, C., Cramm, H., Dell, L., Fikretoglu, D., Forbes, D., Heber, A., Hosseiny, F., Morganstein, J. C., Murphy, D., Nazarov, A., Pedlar, D., Richardson, J. D., Sadler, N., Williamson, V., Greenberg, N., & Jetly, R. (2022). Addressing moral injury in the military. BMJ Military Health, e002128. 10.1136/BMJMILITARY-2022-002128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Keyser, J., Fucella, P., & Maguen, S. (2018). Healing from moral injury: A qualitative evaluation of the impact of killing treatment for combat veterans. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(6), 645–673. 10.1080/10926771.2018.1463582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz, S., & Gray, M. (2015). Treatment for distress associated with accurate appraisals of self-blame for moral transgressions. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 11(3), 207–219. 10.2174/1573400511666150629105709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, J., Herrell, R. K., Hoge, C. W., Fear, N. T., Adler, A. B., Greenberg, N., … & Bliese, P. D. (2014). Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(3), 200–207. Retrieved 10 May 2017, from http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/early/2014/01/02/bjp.bp.113.129569.short. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, E., & Coll, J. (2011). The influence of military culture and veteran worldviews on mental health treatment: Practice implications for combat veteran help-seeking and wellness. International Journal of Health, Wellness & Society, Retrieved 26 May, from https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/socwork_fac/403. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Greenberg, N., & Murphy, D. (2019). Moral injury in UK armed forces veterans: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1562842. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1562842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Phelps, A., Forbes, D., & Greenberg, N. (2021). Moral injury: The effect on mental health and implications for treatment. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(6), 453–455. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00113-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A., Allen, S., Jones, E., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The impact of trauma exposure and moral injury on UK military veterans: a qualitative study. European journal of psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1704554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A., Jones, E., Allen, S., & Greenberg, N. (2021a). Family and occupational functioning following military trauma exposure and moral injury. BMJ Military Health, 10.1136/BMJMILITARY-2020-001770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A. M., Jones, E., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2020). Confidentiality and psychological treatment of moral injury: The elephant in the room. BMJ Military Health, 167(6), 451–453. 10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A. M., Allen, S., Jones, E., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The impact of trauma exposure and moral injury on UK military veterans: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1704554. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1704554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A. M., Allen, S., Jones, E., & Greenberg, N. (2021b). Delivering treatment to morally injured UK military personnel and veterans: The clinician experience. Military Psychology, 33(2), 115–123. 10.1080/08995605.2021.1897495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A. M., Allen, S., Jones, E., & Greenberg, N. (2021c). The impact of moral injury on the wellbeing of UK military veterans. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 1–7. 10.1186/s40359-021-00578-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A. M., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(6), 339–346. 10.1192/BJP.2018.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco, B. E., Marx, B. P., May, C. L., Martini, B., Krystal, J. H., Southwick, S. M., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2017). Moral injury in U.S. combat veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depression and Anxiety, 34(4), 340–347. 10.1002/DA.22614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeterian, J. D., Berke, D. S., Carney, J. R., McIntyre-Smith, A., St. Cyr, K., King, L., Kline, N. K., Phelps, A., & Litz, B. T. (2019). Defining and measuring moral injury: Rationale, design, and preliminary findings from the moral injury outcome scale consortium. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 363–372. 10.1002/JTS.22380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeterian, J. D., Berke, D. S., Carney, J. R., McIntyre-Smith, A., St. Cyr, K., King, L., … & Moral Injury Outcomes Project Consortium . (2019). Defining and measuring moral injury: Rationale, design, and preliminary findings from the moral injury outcome scale consortium. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuromski, K. L., Ustun, B., Hwang, I., Keane, T. M., Marx, B. P., Stein, M. B., Ursano, R. J., & Kessler, R. C. (2019). Developing an optimal short-form of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Depression and Anxiety, 36(9), 790–800. 10.1002/DA.22942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]