Abstract

Purpose:

Ionizing radiation induces a vast array of DNA lesions including base damage, and single- and double-strand breaks (SSB, DSB). DSBs are among the most cytotoxic lesions, and mis-repair causes small- and large-scale genome alterations that can contribute to carcinogenesis. Indeed, ionizing radiation is a ‘complete’ carcinogen. DSBs arise immediately after irradiation, termed ‘frank DSBs,’ as well as several hours later in a replication-dependent manner, termed ‘secondary’ or ‘replication-dependent DSBs. DSBs resulting from replication fork collapse are single-ended and thus pose a distinct problem from two-ended, frank DSBs. DSBs are repaired by error-prone non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), or generally error-free homologous recombination (HR), each with sub-pathways. Clarifying how these pathways operate in normal and tumor cells is critical to increasing tumor control and minimizing side effects during radiotherapy.

Conclusions:

The choice between NHEJ and HR is regulated during the cell cycle and by other factors. DSB repair pathways are major contributors to cell survival after ionizing radiation, including tumor-resistance to radiotherapy. Several nucleases are important for HR-mediated repair of replication-dependent DSBs and thus replication fork restart. These include three structure-specific nucleases, the 3’ MUS81 nuclease, and two 5’ nucleases, EEPD1 and Metnase, as well as three end-resection nucleases, MRE11, EXO1, and DNA2. The three structure-specific nucleases evolved at very different times, suggesting incremental acceleration of replication fork restart to limit toxic HR intermediates and genome instability as genomes increased in size during evolution, including the gain of large numbers of HR-prone repetitive elements. Ionizing radiation also induces delayed effects, observed days to weeks after exposure, including delayed cell death and delayed HR. In this review we highlight the roles of HR in cellular responses to ionizing radiation, and discuss the importance of HR as an exploitable target for cancer radiotherapy.

Keywords: DNA repair, DNA double-strand breaks, homologous recombination, ionizing radiation, replication stress, cancer radiotherapy

Introduction

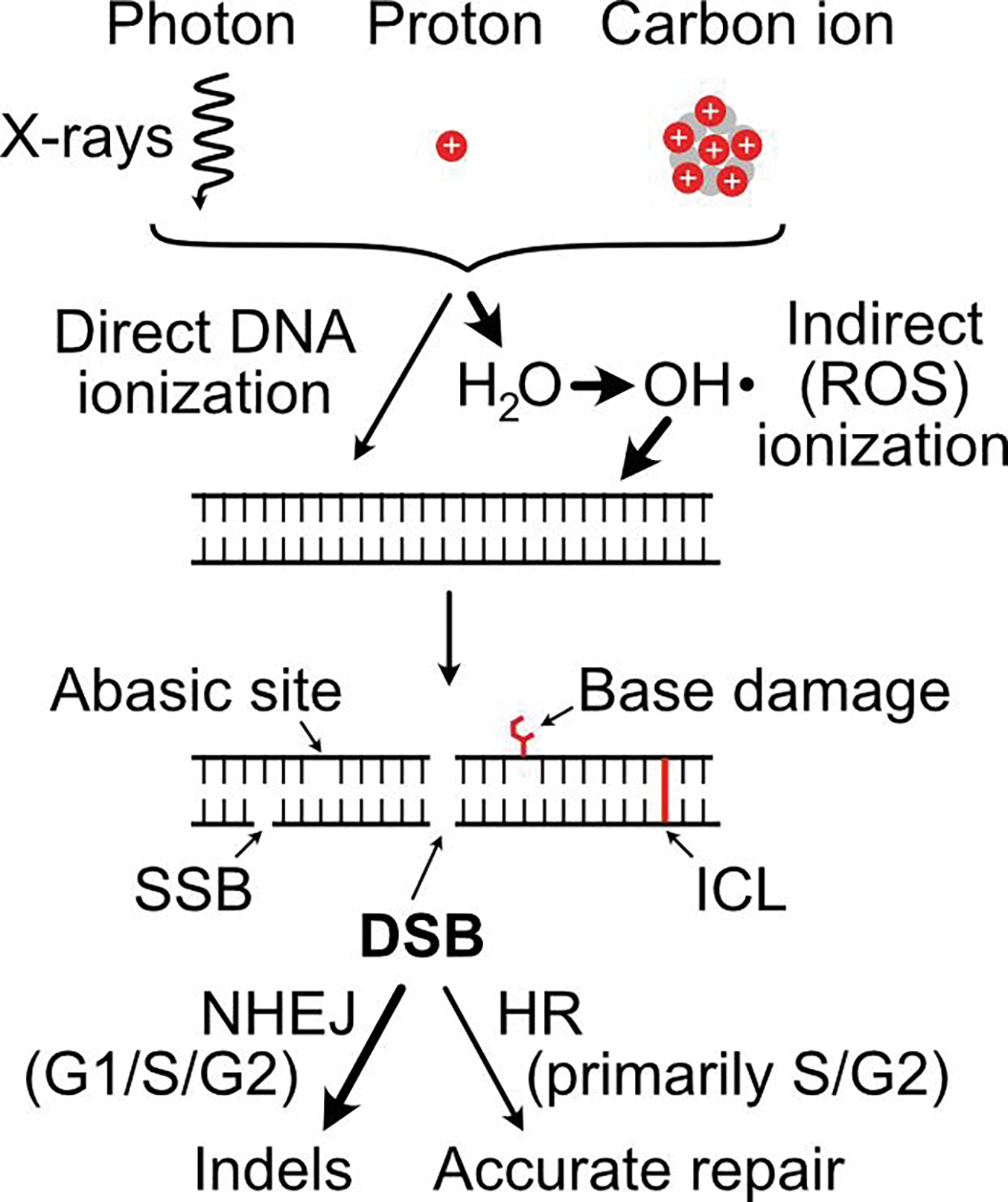

Ionizing radiation comprises high-energy photons (X- and γ-rays) and charged particles, including protons and ions with greater mass and charge, such as carbon and iron ions. At present, many solid tumors are treated with X-rays, protons, and carbon ions in mono- or combination therapies (Halperin et al. 2018), although early studies suggest other intermediate mass/charge particles have potential therapeutic value, including neon and oxygen (Linstadt et al. 1991; Sokol et al. 2017). Fast neutrons are also used in therapeutic applications, but neutrons are more difficult to focus than charged particles, and shielding poses significant challenges, severely limiting its use in clinical practice. Currently, neutrons are largely being explored in boron-neutron capture therapy (Moss 2014). Regardless of how ionizing radiation is delivered, its cell-killing effects are due to cellular damage caused by direct energy absorption and to a greater extent, to indirect effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radicals produced by ionization of water (Azzam et al. 2012), although secondary ROS produced by mitochondria are also induced by ionizing radiation (Yoshino and Kashiwakura 2017). In terms of cell killing, the most important target for ionization radiation and ROS is DNA, and these events result in a wide variety of DNA lesions including oxidative damage, ring-opened bases, and single-strand breaks (collectively termed single-strand damage), and double-strand breaks (DSBs) (Ward 2000). DSBs have long been the lesion of interest in radiobiology and radiation oncology because DSBs, along with intra-strand DNA crosslinks, are the most cytotoxic DNA lesions. These general features of ionizing radiation damage to DNA are summarized in Figure 1. Cells respond to DSBs and other types of DNA damage by activating checkpoint signaling and DNA repair pathways, collectively termed the DNA damage response (DDR). The DDR promotes cell survival and suppresses cancer by promoting genome stability and by triggering programmed cell death pathways (Ciccia and Elledge 2010; Goldstein and Kastan 2015; O’Connor 2015; Tian et al. 2015; Desai et al. 2018). The DDR responds to frank DSBs induced by ionizing radiation as well as DSBs that arise at collapsed replication forks. Central regulators of the DDR include three related kinases of the phosphatidyl inositol 3’ kinase-related kinase (PIKK) family, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), ATM and RAD3-related (ATR), and the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs). These kinases are activated after DNA damage and phosphorylate many downstream targets to activate DNA damage checkpoints and stimulate DNA repair. PIKKs operate in cross-talking damage signaling networks. For example, all three PIKKs phosphorylate RPA32 bound to ssDNA, a key step in checkpoint activation, and certain RPA32 serine/threonine residues are phosphorylated by multiple PIKKs (Liu et al. 2012). Despite the extensive cross-talk among PIKKs, the emerging view is that DNA-PKcs has a direct and central role in NHEJ, while ATM and ATR have critical roles in promoting HR repair of frank DSBs, and DSBs at collapsed replication forks, respectively (Blackford and Jackson 2017). DDR networks, and replication stress responses in particular, are important research areas because altered expression or mutation of replication stress proteins predispose to cancer and determine tumor response to chemo- and radiotherapy (Carrassa and Damia 2017; Hengel et al. 2017; Pilie et al. 2019; Nickoloff et al. 2020b).

Figure 1.

Overview of ionizing radiation effects on DNA and DSB repair pathways. Three types of ionizing radiation are currently used therapeutically. Photons are massless energy, protons are low mass particles with a single positive charge, and carbon ions have six positively charged protons and six neutrons. Protons and neutrons are shown by red and grey circles, respectively. Radiation can ionize DNA directly or indirectly via production of ROS (principally H2O) that attacks DNA. Five major classes of DNA damage that result are diagrammed, including DSBs, the principal cytotoxic lesions that are repaired by NHEJ and HR. Dominant ionization mechanisms and DSB repair pathways are indicated by thick arrows.

DSBs are repaired by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) (Chang et al. 2017; Nickoloff et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2018). NHEJ rejoins ends without requiring a repair template, thus it is error-prone and typically yields short deletions or insertions at repair junctions. NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle, and it is the dominant DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells. HR requires a homologous repair template and is therefore generally error-free, although rare mutations do arise during repair synthesis (Strathern et al. 1995; Hicks et al. 2010; Guirouilh-Barbat et al. 2014), and crossovers can result in large-scale rearrangements including deletions, inversions, amplifications, and (rarely) translocations (Narayanan and Lobachev 2007; Hermetz et al. 2012; Guirouilh-Barbat et al. 2014; Reams and Roth 2015; Nickoloff 2017). HR is largely restricted to S/G2 phases of the cell cycle, reflecting several levels of regulation, such as expression of key HR proteins including RAD51 (Yamamoto et al. 1996), and factors that regulate 5’–3’ end resection like CtIP, BRCA1, 53BP1 and RIF1 (Sartori et al. 2007; Huertas and Jackson 2009; Escribano-Diaz et al. 2013; Cruz-Garcia et al. 2014; Makharashvili and Paull 2015). During HR, broken ends can invade any homologous sequence in the genome (homologous chromosomes, repetitive sequences, etc.), but the general restriction of HR to S/G2 phases means that most HR is accomplished using proximate, sister chromatid repair templates, which increases repair accuracy. In addition, factors that suppress crossovers (e.g., Sgs1 in yeast, BLM in mammalian cells), and the bias toward synthesis-dependent strand annealing, limit HR-associated chromosomal rearrangements (Ira et al. 2003; Lo et al. 2006; Raynard et al. 2006; Oh et al. 2007; Moynahan and Jasin 2010). As discussed further below, HR is important for (generally) accurate repair of frank DSBs, such as those induced directly by ionizing radiation, and it is critical for repair of replication-associated DSBs, including those arising when replication forks encounter radiation-induced single-strand lesions.

HR-mediated DSB repair mechanisms

RAD51-dependent and RAD51-independent HR mechanisms

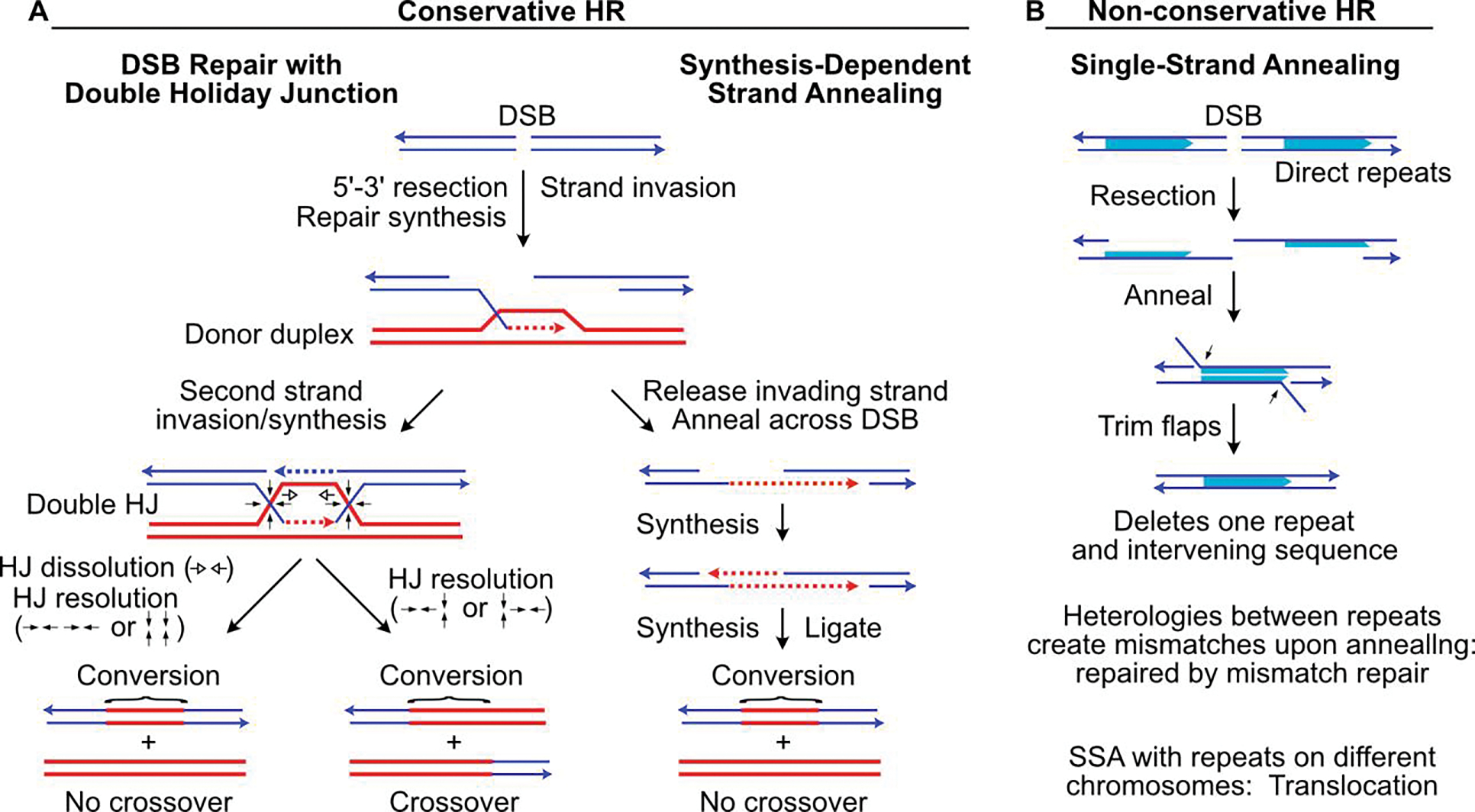

HR comprises conservative, RAD51-dependent, and non-conservative, RAD51-independent repair mechanisms. RAD51-dependent HR generally results in accurate repair and gene conversion. Two RAD51-dependent DSB repair mechanisms have been proposed, one that involves one strand invasion into a homologous donor duplex, termed synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), and a second in which both ends invade, producing double-HJ structures, often denoted by the generic term ‘DSB repair’ (Figure 2A). Non-conservative HR, termed single-strand annealing (SSA) is RAD51-independent, but requires the ssDNA annealing function of RAD52 (Bhargava et al. 2016). SSA can operate when interacting homologous sequences are linked in direct orientation, so-called ‘direct repeats’ (Figure 2B). SSA can also mediate translocations if interacting repeats are on different chromosomes, as shown with nuclease-induced DSBs in mammalian cells (Elliott et al. 2005) and ionizing radiation in yeast (Argueso et al. 2008). SSA is non-conservative because it deletes one of the repeats, as well as intervening sequences between linked repeats, or causes translocations with unlinked repeats. Defects in RAD51-dependent HR shift repair toward error-prone NHEJ and SSA, which increases genome instability, first shown in BRCA2-defective cells (Tutt et al. 2001).

Figure 2.

HR-mediated DSB repair mechanisms. (A) DSB repair by conservative HR can proceed by two-strand invasion (left) of a homologous donor duplex, producing a double HJ intermediate that can be resolved into crossover or non-crossover gene conversion products. Dissolution of the double HJ intermediate can occur by convergence of HJs by branch migration (open arrows) to yield a non-crossover product. HJ resolution by cleavage/rejoining (filled arrows), leads to non-crossover products if cleaved in the same ‘horizontal’ or ‘vertical’ sense (bottom left), or to crossover products if cleaved in opposite senses (bottom right). SDSA (right) involves a single end invasion, repair synthesis across the DSB, release from the donor, and reannealing to the non-invading strand, followed by gap filling and DNA ligation. (B) SSA shown between linked, direct repeats. Resection from broken ends exposes ssDNA in flanking homologous sequences (shaded arrows) that anneal. Flap trimming and gap filling completes repair, with one repeat and intervening sequence deleted, yielding non-conservative repair products.

In mammalian cells, HR and NHEJ both contribute to repair of ionizing radiation-induced DSBs. Thus, HR and NHEJ are competing DSB repair mechanisms (Allen et al. 2003; Kass and Jasin 2010; Scully et al. 2019). In mammalian cells, NHEJ is the dominant mechanism that repairs ionizing radiation-induced DSBs, but there is evidence that HR has increased importance in the repair of clustered DSBs induced by high linear energy transfer (LET) carbon and other heavy ions (Hada and Sutherland 2006; Okayasu et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2010), although despite this shift, NHEJ may still be dominant (Takahashi et al. 2014). Because HR has increased importance in repairing clustered DSBs, targeting HR may provide specific benefits to patients treated with carbon ion radiotherapy (Nickoloff et al. 2020a; Nickoloff et al. 2020b).

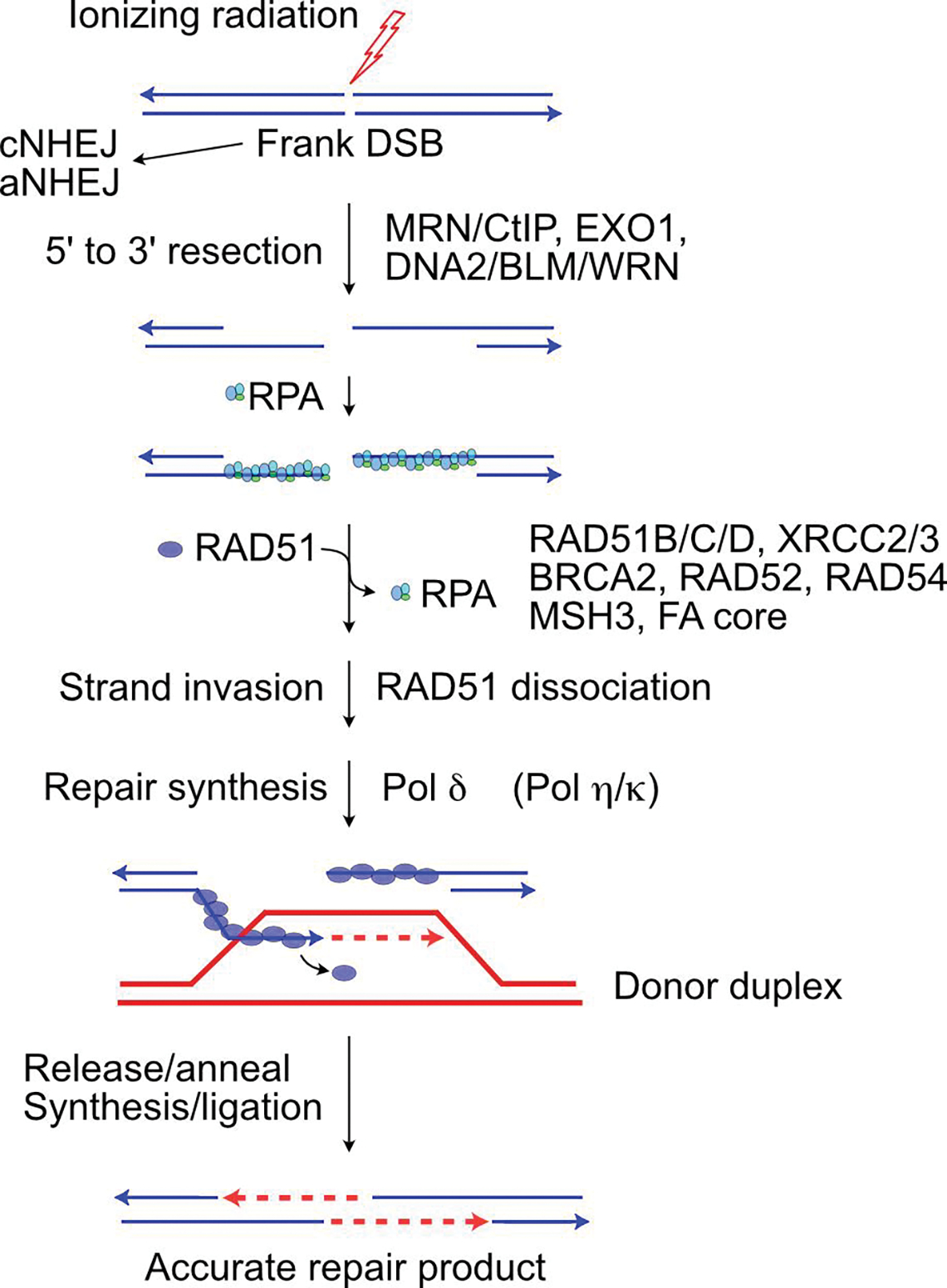

Overview of HR enzymology: end resection, strand invasion and repair synthesis

BRCA1 has a key role in coordinating the choice between NHEJ and HR (Durant and Nickoloff 2005). Classical, DNA-PK-mediated NHEJ, and alternative, DNA-PK-independent NHEJ, require no, or very limited resection, exposing nearby microhomologies flanking the DSB. HR requires many proteins that operate in distinct steps, diagrammed for SDSA in Figure 3. HR is initiated by extensive 5’ to 3’ end resection, which creates long 3’ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails. BRCA1 promotes end resection by inhibiting the early-acting DSB repair proteins 53BP1 and RIF1 that suppress end resection, and by promoting activity of resection nucleases/co-factors MRE11/RAD50/NBS1 (MRN), CtIP, EXO1, and DNA2/BLM (Zimmermann et al. 2013; Cruz-Garcia et al. 2014; Ceccaldi et al. 2016; Symington 2016; Nickoloff et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2020). MRN and CtIP collaborate to expose ssDNA tails up to ~100 nt, and more extensive resection is catalyzed by EXO1, and by DNA2 with BLM or WRN helicases as co-factors (Sturzenegger et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2020). Excessive resection is suppressed by HELB and by phosphorylation of EXO1 SQ motifs by the DNA damage signaling kinase ATR (Tkac et al. 2016; Tomimatsu et al. 2017). ssDNA exposed by resection is rapidly coated by the single-strand binding protein RPA, which is subsequently replaced with RAD51 in a reaction facilitated by RAD51 paralogs (XRCC2, XRCC3, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D), RAD52, RAD54, BRCA2, MSH3, and the Fanconi anemia core complex (Jasin and Rothstein 2013; Michl et al. 2016; Nickoloff et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2018). In higher eukaryotic cells, RAD51 knockout is cell lethal (Sonoda et al. 1998), but defects in the facilitator proteins generally reduce HR by ~50% and increase genome instability, reflected in shifts toward SSA (Tutt et al. 1999; Tutt et al. 2001) and altered gene conversion tract structures (Brenneman et al. 2000; Brenneman et al. 2002; Nagaraju et al. 2006; Nagaraju et al. 2009; Chandramouly et al. 2013). The resulting RAD51 nucleoprotein filament is able to scan the genome for homologous donor duplexes and catalyze strand invasion aided by the RAD54 chromatin remodeler and other factors (Miyagawa et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2007; Ceballos and Heyer 2011; Yasuhara et al. 2014). RAD51 then dissociates from ssDNA to allow repair synthesis by DNA polymerase δ and/or polymerases η and κ to extend invading 3’ ends. This requirement for RAD51 dissociation prior to repair synthesis means that detection of RAD51 foci is indicative of functional, early HR steps, but not necessarily completion of HR. Thus, persistent RAD51 foci may reflect failed, late HR steps (Shrivastav et al. 2009). Once repair synthesis extends beyond the position of the original DSB, invading strands dissociate from the donor duplex and reanneal with ssDNA distal to the original DSB. Repair is then completed by further repair synthesis and ligation to fill remaining gaps and restore the uninterrupted duplex DNA. If double-HJ intermediates arise during HR, they can be dissolved by convergent HJ branch migration mediated by the ‘dissolvasome’ complex comprising BLM, TopoIIIα, and RMI1 (Bizard and Hickson 2014), or resolved via cleavage/religation initiated by MUS81/EME1, or by the SLX4 docking protein and the GEN1 structure-specific nuclease (Dehe et al. 2013; Naim et al. 2013; Wyatt et al. 2013; Amangyeld et al. 2014; Pepe and West 2014a, 2014b).

Figure 3.

HR-mediated DSB repair enzymology. Resection by indicated nucleases prevents DSB repair by classical or alternative NHEJ, exposing 3’ ssDNA tails that are first coated by RPA and then RAD51, an exchange facilitated by RAD51 paralogs, BRCA2, RAD52, RAD54 and other factors. RAD51-ssDNA filaments invade homologous duplex DNA, and RAD51 dissociates to allow repair synthesis. In this SDSA reaction, the invading strand is released to reanneal with the second broken (resected) end. Further repair synthesis fills remaining gaps and ligation completes repair.

HR-mediated repair of secondary, replication-dependent DSBs induced by ionizing radiation

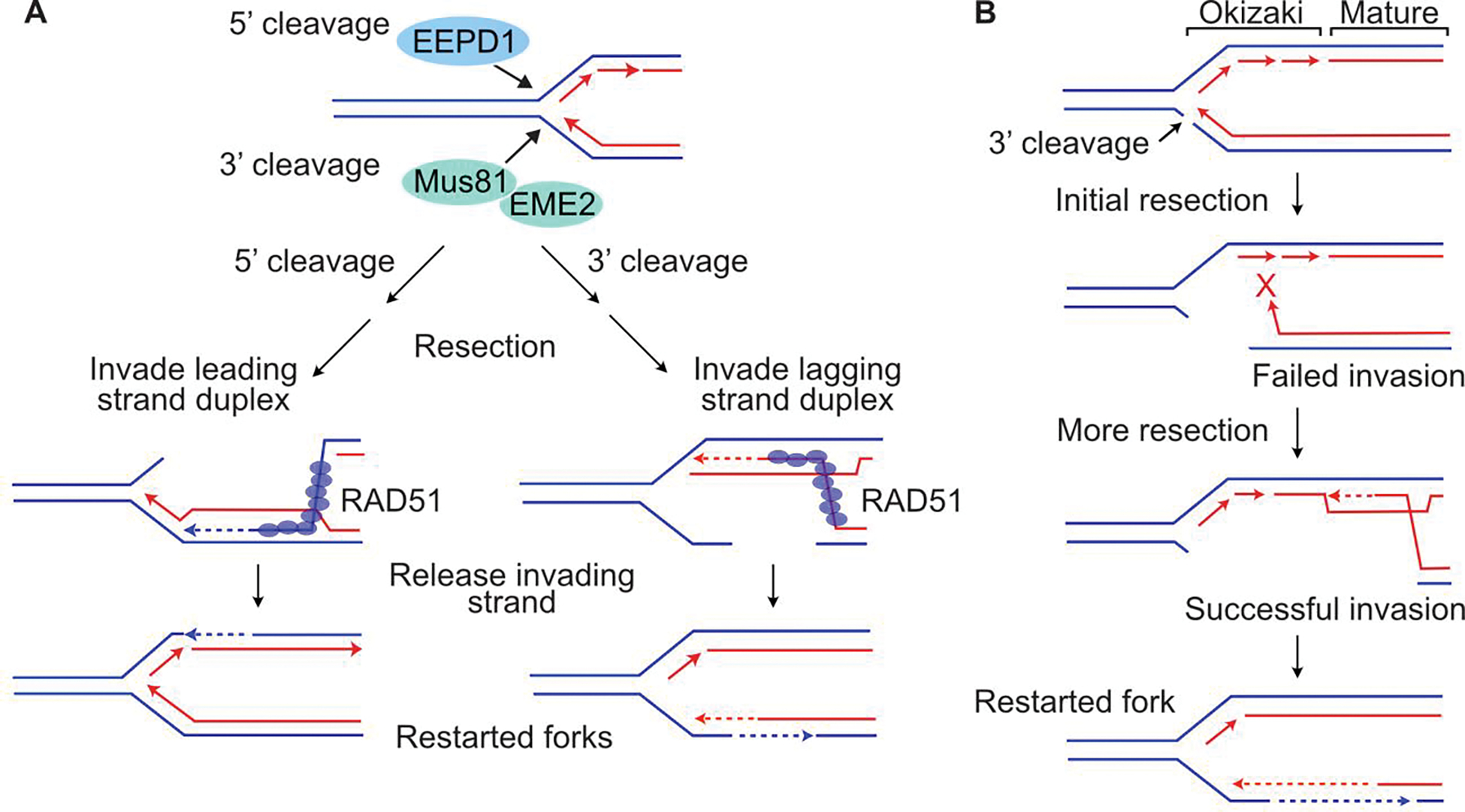

The discussion above focuses on HR repair of frank DSBs, such as those induced by nucleases or immediately after irradiation. HR also plays a critical role in response to replication stress caused by single-strand DNA lesions that arise spontaneously due to endogenous ROS, and that are induced by chemotherapeutic drugs and ionizing radiation. For every DSB induced by ionizing radiation, ~100-fold more SSBs and other single-strand lesions are induced (Ward 2000). While most single-strand lesions are repaired efficiently, even moderate doses of ionizing radiation (1 to a few Gy) induce thousands of such lesions. As noted in the Introduction, the DDR includes DNA damage checkpoints that cause cell cycle arrest and promote DNA repair. The G1/S checkpoint prevents G1 cells from entering S phase, and the intra-S checkpoint stops ongoing replication and prevents new origin firing. Both checkpoints prevent replication stress by preventing replication fork encounters with single-strand damage (Grallert and Boye 2008; Yazinski and Zou 2016). However, cell cycle checkpoints have limitations. For example, yeast display ‘checkpoint adaptation’ in which cells re-enter the cell cycle despite persistent DSBs, a response regulated by Ku, Mre11, and RPA; although adaptation permits cells to resume cycling, this ultimately has lethal consequences (Lee et al. 1998). Moreover, in mammalian cells, the G1/S checkpoint is activated slowly by ionizing radiation, and some G1 cells with damage enter S phase for several hours after IR (Deckbar et al. 2011). The intra-S checkpoint is mediated by ATR, but ATR activation is slow because it requires DSB processing to yield RPA-bound ssDNA (Yazinski and Zou 2016), and hyperphosphorylation of the RPA32 subunit in RPA-bound ssDNA, marked by phosphorylated RPA32 Ser4/Ser8, is critical for activation of Chk1 (Liaw et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2012; Ashley et al. 2014). Indeed, irradiation of S-phase cells, even with a very high dose (50 Gy), doesn’t slow or stop elongating replisomes (Merrick et al. 2004; Groth et al. 2012). Thus, despite DDR safeguards, ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage is encountered by replication forks, causing replication stress that reflects fork stalling and/or fork collapse to DSBs (Zeman and Cimprich 2014; Puigvert et al. 2016; Hsieh and Peng 2017). Unlike frank DSBs, replication-dependent DSBs are one-ended (Figure 4). It is well-appreciated that replication-dependent DSBs are repaired by HR (Arnaudeau et al. 2001; Budzowska and Kanaar 2009; Allen et al. 2011; Prado 2018). Although HR-mediated fork repair and restart poses risks associated with the production of toxic HR intermediates (Appanah et al. 2020; Lehmann et al. 2020; Malacaria et al. 2020), it is even more risky for single-ended DSBs to be repaired by NHEJ as this is guaranteed to result in chromosomal rearrangements because such repair necessarily involves joining of DSBs arising at distant, collapsed replication forks (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

HR-mediated repair and restart of stressed replication forks. Ionizing radiation induces single-strand lesion (shown here as ring-opened base, red) that blocks a replication fork. MUS81 cleavage yields a one-ended DSB (EEPD1 cleaves in the opposite polarity; see Figure 5). Resection of the broken end initiates RAD51-mediated strand invasion of the sister chromatid, followed by repair synthesis, and release/reannealing of the invading strand, as shown in Figure 3. Failure to resect the one-ended DSB may lead to genome rearrangements via NHEJ-mediated joining of one-ended DSBs from different collapsed forks.

Replication-dependent DSBs appear several hours after irradiation, once replication forks encounter damage and collapse to single-ended DSBs. The first evidence for these late-arising DSBs was obtained by kinetic analysis of co-localized, radiation-induced repair foci by RAD51, BCCIP (BRCA2 and CDKN1A-interacting protein), RAD52, and γH2AX, a well-characterized marker of DSBs (Wray et al. 2008). This study showed an initial wave of RAD51 foci co-localized with BCCIP that peaked 2 h after irradiation, and a second wave of RAD51 foci co-localized with RAD52 that peaked 6 h after irradiation. Subsequently, direct measures of replication-dependent DSBs after irradiation were reported (Groth et al. 2012). The kinetics of RAD52 foci formation was surprising at that time, because RAD52 roles in HR in mammalian cells were unclear. RAD52 plays an essential role in all HR in yeast, including HR repair of DSBs induced by radiation, nucleases, and replication stress. Yeast RAD52 has two key HR functions: ssDNA annealing and its mediator function to load RAD51 onto ssDNA (by exchanging RPA with RAD51). RAD52 defects in yeast cause extreme sensitivity to ionizing radiation and nuclease-induced DSBs, yet RAD52 defects in mouse cells confer no radiosensitivity (Rijkers et al. 1998). In mammalian cells, BRCA2 mediates RAD51 loading onto ssDNA through nine domains that interact with RAD51, including 8 BRC repeats and an exon 27 domain (Davies et al. 2001; Powell et al. 2002). Yeast lack BRCA2, and the absence of a strong radiosensitivity phenotype in RAD52-defective mammalian cells led to speculation in 2002 that BRCA2 had subsumed RAD52 roles in HR (Yang et al. 2002) - this despite strong conservation of RAD52 from yeast to human, and its expression in many tissues in mice (Shen et al. 1995). This puzzle began to be resolved with the finding that RAD52 foci appear many hours after irradiation, with the proposal in 2008 that mammalian RAD52 had lost much of its functionality in HR repair of frank DSBs, but retained an evolutionarily-conserved function in HR-mediated repair of replication-dependent DSBs (Wray et al. 2008). Several subsequent studies established the critical roles of mammalian RAD52 in HR during replication stress (Hengel et al. 2016; Sotiriou et al. 2016; Ozer and Hickson 2018; Kelso et al. 2019; Malacaria et al. 2019; Wu 2019; Malacaria et al. 2020).

Nucleases involved in HR-mediated replication fork repair and restart

Replication-dependent DSBs observed after irradiation may arise when replication forks encounter SSBs, directly producing a single-ended DSB. Most DNA lesions block replicative DNA polymerases, although some are bypassed when error-prone, translesion DNA `s are engaged, such as human polymerases η, ι, and κ, REV1, and REV3 (Goodman and Woodgate 2013; Sweasy 2020). In addition, replication-dependent DSBs can arise at blocked replication forks, and forks stalled by nucleotide depletion with hydroxyurea, by cleavage with structure-specific nucleases. Although this introduces yet another type of DNA damage (DSBs), fork cleavage creates a substrate for accurate fork repair and restart (Allen et al. 2011; Yeeles et al. 2013; Pepe and West 2014a; Fu et al. 2015; Mayle et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2015; Pasero and Vindigni 2017; Sharma et al. 2020), and it avoids both translesion DNA polymerase-induced mutations and aberrant fork restructuring, such as fork regression to HJ-like ‘chicken foot’ structures that may convert to toxic HR intermediates (Fabre et al. 2002; Heyer et al. 2010; Appanah et al. 2020).

Three nucleases have been implicated in cleavage of blocked or stalled replication forks, yielding replication-dependent DSBs. MUS81 is an ancient, 3’ structure-specific endonuclease that is assisted by EME1 or EME2 co-factors. MUS81/EME2 cleaves blocked or stalled replication forks to promote accurate fork restart Defects in MUS81 or EME2 inhibit restart of stressed replication forks, and increase genome instability (Pepe and West 2014a). As noted above, HJs in HR intermediates can be resolved by MUS81/EME1 or SLX4/GEN1. Of note, SLX4 also assists MUS81 in cleaving stressed replication forks, and it also regulates GEN1 activity during fork processing (Malacaria et al. 2017). EEPD1 is a 5’ structure-specific endonuclease that arose ~500 million years ago in chordates and early vertebrates. Metnase is another 5’ structure-specific endonuclease that evolved much later, first appearing in monkeys ~50 million years ago (Cordaux et al. 2006). Defects in either EEPD1 or Metnase slow restart of stressed replication forks and increase the frequency of forks that fail to restart within 20–30 min of release from replication stress (De Haro et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2017; Sharma et al. 2020). Metnase also promotes NHEJ and TopoIIα-dependent chromosome decatenation (Lee et al. 2005; Hromas et al. 2008; Wray et al. 2009a; Wray et al. 2009b; Fnu et al. 2011). Despite the similarities between EEPD1 and Metnase, recent evidence indicates that only EEPD1 cleaves stalled/blocked forks. Metnase has both protein methylation and nuclease activities, both of which are important for timely, HR-mediated restart of stalled replication forks (Kim et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2015). This suggests that Metnase nuclease may function later during fork restart, perhaps trimming flaps that arise during fork processing (Sharma et al. 2020). Once EEPD1 cleaves stalled forks, it recruits EXO1 to initiate resection of the resulting single-ended DSBs, thereby suppressing (genome-destabilizing) NHEJ and promoting (genome-stabilizing) HR-mediated fork repair and restart (Wu et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2017). Interestingly, Metnase also promotes EXO1 resection at stressed replication forks (Kim et al. 2016).

Single-strand base damage arising spontaneously from endogenous ROS, or induced by ionizing radiation, is repaired by the base excision repair (BER) pathway, with a family of DNA glycosylases and APEX1 playing central roles (Wallace 2014; Mullins et al. 2019). We recently discovered that EEPD1 can substitute for APEX1 in BER (Jaiswal et al., communicated). EEPD1 binds to and cleaves DNA with an abasic site mimic, mirroring APEX1 activity, and EEPD1 can replace APEX1 in abasic site repair in reconstituted short- and long-patch BER. EEPD1 can also process 8-oxo-dG and abasic lesions in genomic DNA in vivo, and EEPD1 knockout cells are hypersensitive to oxidative and alkylation damage. As mentioned above, EEPD1 cleaves stalled replication forks (Wu et al. 2015; Sharma et al. 2020), and we further demonstrated that EEPD1 is recruited to, and promotes restart of replication forks stressed by H2O2 oxidative damage. Thus, EEPD1 appears to function in an alternative BER pathway during replication stress. It is likely that EEPD1 plays a similar role in accelerating repair and restart of replication forks blocked by base damage induced by ionizing radiation.

As noted above, EEPD1 evolved much later than MUS81, co-incident with large expansions in genome size and the number of repetitive elements. Neither EEPD1 nor Metnase are essential as human knockout cells are viable (Sharma et al. 2020), suggesting that these proteins augment DNA repair. In particular, their ability to promote fork restart may have been important to ensure timely and accurate DNA replication as genomes grew larger and more complex. In this regard, the fact that EEPD1 is a 5’ nuclease that cleaves stressed replication forks provides a counterpart to the previously established 3’ nuclease function of MUS81 (Figure 5A). Not only does EEPD1 represent additional means to cleave stressed replication forks to promote HR-mediated fork repair, its 5’ polarity may be superior to MUS81 given that single-ended DSBs produced by MUS81 must invade the sister chromatid produced by lagging strand synthesis (Figure 5B). By contrast, 5’ cleavage by EEPD1 produces single-ended DSBs that invade the leading strand sister chromatid (Fig. 4A). With 3’ cleavage by MUS81, limited resection would force invasion into the discontinuous (immature), Okazaki fragment region, and invasion may thus fail. More extensive resection would allow successful invasion into the mature duplex DNA, but this would require more time. This limitation does not apply when single-ended DSBs are created by EEPD1 as this involves invasion of the (continuous) leading strand sister chromatid. 5’ cleavage by EEPD1 may be a superior fork restart mechanism because it requires less resection and accelerating fork restart, which could promote genome stability by minimizing the chance that blocked forks will assume toxic recombination structures. Indeed, defects in EEPD1 slow fork restart and this correlates with increased genome instability, both in human cells and during zebrafish embryonic development (Wu et al. 2015; Chun et al. 2016).

Figure 5.

Polarity of fork cleavage may influence timing of fork restart. (A) 5’ or 3’ fork cleavage by EEPD1 or MUS81/EME2, respectively, can initiate HR-mediated fork repair and restart via steps as shown in Figure 3. (B) 3’ fork cleavage by MUS81/EME2 forces strand invasion into sister chromatid produced by lagging strand DNA synthesis, which has discontinuous Okazaki fragments adjacent to the fork and mature, continuous duplex DNA further from the fork. Limited resection may result in failed invasion into discontinuous region (red X), but more extensive resection, requiring more time, allows successful invasion into mature duplex DNA. 5’ cleavage by EEPD1 may speed fork restart as less resection is needed because strand invasion can occur anywhere along the continuous, leading strand sister chromatid (see panel A).

Delayed HR after irradiation

The effects described above are observed within minutes to hours after irradiation. Ionizing radiation also induces delayed effects that are observed days or weeks after exposure, and such late effects can be seen with very low, non-lethal (e.g., cGy) doses. The pioneering work of J. B. Little at Harvard University School of Public Health, and other groups, discovered that ionizing radiation induces a variety of delayed effects, including mutations, chromosome translocations, chromosome aberrations, micronuclei, microsatellite instability, giant cells, and cell death (Kennedy et al. 1980; Kennedy et al. 1984; Gorgojo and Little 1989; Little et al. 1990; Chang and Little 1991, 1992a, 1992b; Roy et al. 1999; Dahle and Kvam 2003; Morgan 2003b, 2003a). Based on these results, the Morgan and Nickoloff labs investigated whether radiation would also induce delayed HR. To monitor delayed HR, a human cell line with a single integrated copy of a GFP direct repeat HR substrate was used. HR between the two inactive copies of GFP creates a functional GFP detectable by green fluorescence via microscopy. Cells were irradiated, seeded to dishes, and colonies were scored after two weeks. In this system, HR induced immediately by radiation yields fully GFP-positive colonies, whereas delayed HR yields mixed GFP-positive and -negative colonies. Low dose X-ray exposures showing little or no cytotoxicity induced delayed HR in up to 10% of cells (Huang et al. 2004), and delayed HR was subsequently shown to be suppressed by very low (cGy) ‘priming’ doses, indicative of an adaptive response (Huang et al. 2007). Delayed HR is induced by low LET X-rays and high LET carbon ions, and in both cases, HR was found to increase over a two-week period before resolving to background levels in the third week after irradiation (Allen et al. 2017). These results indicated that although delayed HR might raise concerns about the induction of HR-mediated genome instability by low-dose exposures of normal tissue during radiotherapy, such concerns apply equally to conventional X-ray therapy and high LET carbon ion radiotherapy.

Future perspectives: Targeting HR to enhance cancer radiotherapy

Given that radiotherapy has been practiced since the early 20th century and more than half of cancer patients receive radiation treatments, there was strong motivation to move clinical practice from an empirical to a mechanistic foundation. This prompted the expansion of the molecular radiobiology field in the latter half of the century, built on the pioneering work of J.B. Little, S.S. Wallace, R.B. Setlow, H.B. Stone, P. Hanawalt, H.H. Evans, P. Howard-Flanders, P.L. Olive, J. Fowler, G. Failla, J. Denekamp, V.D. Courtenay, E.L. Travis, S.L. Tucker, W.H. McBride, F.A. Stewart, H.R. Withers, and many others (Wallace 2021). With the advent of genetic engineering, tools to isolate, modify, and detect specific proteins, and sensitive imaging techniques such as fluorescence microscopy, radiobiology flourished and a plethora of DSB repair and DDR proteins were characterized. These advances have driven more effective cancer therapies, and personalized therapy in particular. An important example is the discovery that cancer cells with HR defects, such as those with mutant BRCA1 or BRCA2, are hypersensitive to PARP1 inhibitors (del Rivero and Kohn 2017). In recent years, several HR proteins have emerged as potential targets to enhance the efficacy of cancer radiotherapy, in particular against radioresistant tumors such as glioblastoma. Important therapeutic HR targets include RAD51, which can be inhibited by the small molecule inhibitors RI-1 and B02 (Balbous et al. 2016; King et al. 2017), and cell-penetrating antibodies and antibody fragments (Turchick et al. 2017; Cyteir Therapeutics 2019; Pastushok et al. 2019; Turchick et al. 2019). BRCA2 knockdown radiosensitizes tumor xenografts in mice (Yu et al. 2008), and several PARP1 inhibitors are used both to treat HR-defective tumors and to augment radiotherapy (Hirai et al. 2012; Hirai et al. 2016; Jannetti et al. 2020). Several DDR factors regulate HR and these too are under investigation in the lab and in clinical trials to augment cancer radiotherapy (Carrassa and Damia 2017; Hengel et al. 2017; Tu et al. 2018; Pilie et al. 2019; Nickoloff et al. 2020b). Because HR (and other DNA repair and damage response systems) play important roles in normal cells, a continuing challenge is to identify treatment strategies that enhance tumor cell killing selectively. A promising approach to meet this challenge is illustrated by a recent study showing marked sensitization of tumor cells to high LET Bragg peak proton damage by the ATM inhibitor AZD0156 (Zhou et al. 2021). In this study, specific tumor radiosensitization derives not, per se, from suppression of frank DSB repair by ATM inhibition, but rather from the physical targeting of high LET Bragg peak protons to the tumor volume, and from what appears to be a specific requirement for ATM-promoted HR to repair clustered DSBs induced in the high LET region of the proton Bragg peak. Given the complexity of DSB repair and DDR mechanisms, the search for specific tumor radiosensitization strategies will continue to spawn pre-clinical and clinical investigations for the foreseeable future.

Acknowledgements

We thank S.M. LaRue, S.M. Bailey, Keara Boss, and members of our laboratories and academic departments for helpful discussions. Research in the Nickoloff lab was supported by NIH grant R01 GM084020, American Lung Association grant LCD-686552, the CSU Office of the Vice President for Research, and the Japan National Institute of Radiological Sciences Open Laboratory program. Research in the Hromas lab is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA139429.

Biographies

Biographical sketches for IJRB ms

Jac A. Nickoloff, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and a member of the Flint Animal Cancer Center and the University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Neelam Sharma, PhD, is a Senior Research Scientist in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Christopher P. Allen, PhD, is Co-Director of the Colorado State University Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Lynn Taylor is a Senior Research Associate in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Sage J. Allen is a Research Assistant in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Aruna S. Jaiswal, PhD, is a Research Associate Professor in the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA.

Robert Hromas, MD, FACP, is Professor and Dean of the Long School of Medicine, Vice President for Medical Affairs, faculty in the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, and a member of the Mays Cancer Center, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen C, Ashley AK, Hromas R, Nickoloff JA. 2011. More forks on the road to replication stress recovery. J Mol Cell Biol. 3:4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen C, Halbrook J, Nickoloff JA. 2003. Interactive competition between homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining. Mol Cancer Res. 1:913–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CP, Hirakawa H, Nakajima NI, Moore S, Nie J, Sharma N, Sugiura M, Hoki Y, Araki R, Abe M et al. 2017. Low- and high-LET ionizing radiation induces delayed homologous recombination that persists for two weeks before resolving. Radiat Res. 188(1):82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amangyeld T, Shin YK, Lee M, Kwon B, Seo YS. 2014. Human MUS81-EME2 can cleave a variety of DNA structures including intact Holliday junction and nicked duplex. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(9):5846–5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appanah R, Jones D, Falquet B, Rass U. 2020. Limiting homologous recombination at stalled replication forks is essential for cell viability: DNA2 to the rescue. Curr Genet. 66(6):1085–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argueso JL, Westmoreland J, Mieczkowski PA, Gawel M, Petes TD, Resnick MA. 2008. Double-strand breaks associated with repetitive DNA can reshape the genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105(33):11845–11850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudeau C, Lundin C, Helleday T. 2001. DNA double-strand breaks associated with replication forks are predominantly repaired by homologous recombination involving an exchange mechanism in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 307(5):1235–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley AK, Shrivastav M, Nie J, Amerin C, Troksa K, Glanzer JG, Liu S, Opiyo SO, Dimitrova DD, Le P et al. 2014. DNA-PK phosphorylation of RPA32 Ser4/Ser8 regulates replication stress checkpoint activation, fork restart, homologous recombination and mitotic catastrophe. DNA Repair. 21:131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam EI, Jay-Gerin JP, Pain D. 2012. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer letters. 327(1–2):48–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbous A, Cortes U, Guilloteau K, Rivet P, Pinel B, Duchesne M, Godet J, Boissonnade O, Wager M, Bensadoun RJ et al. 2016. A radiosensitizing effect of RAD51 inhibition in glioblastoma stem-like cells. BMC Cancer. 16:604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava R, Onyango DO, Stark JM. 2016. Regulation of single-strand annealing and its role in genome maintenance. Trends Genet. 32(9):566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizard AH, Hickson ID. 2014. The dissolution of double Holliday junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 6(7):a016477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackford AN, Jackson SP. 2017. ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK: the trinity at the heart of the DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 66(6):801–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenneman MA, Wagener BM, Miller CA, Allen C, Nickoloff JA. 2002. XRCC3 controls the fidelity of homologous recombination: roles for XRCC3 in late stages of recombination. Mol Cell. 10:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenneman MA, Weiss AE, Nickoloff JA, Chen DJ. 2000. XRCC3 is required for efficient repair of chromosome breaks by homologous recombination. Mutat Res. 459:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzowska M, Kanaar R. 2009. Mechanisms of dealing with DNA damage-induced replication problems. Cell Biochem Biophys. 53(1):17–31. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrassa L, Damia G. 2017. DNA damage response inhibitors: Mechanisms and potential applications in cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 60:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos SJ, Heyer WD. 2011. Functions of the Snf2/Swi2 family Rad54 motor protein in homologous recombination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1809(9):509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccaldi R, Rondinelli B, D’Andrea AD. 2016. Repair pathway choices and consequences at the double-strand break. Trends Cell Biol. 26(1):52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouly G, Kwok A, Huang B, Willis NA, Xie A, Scully R. 2013. BRCA1 and CtIP suppress long-tract gene conversion between sister chromatids. Nat Commun. 4:2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HHY, Pannunzio NR, Adachi N, Lieber MR. 2017. Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 18(8):495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WP, Little JB. 1991. Delayed reproductive death in X-irradiated Chinese hamster ovary cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 60(3):483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WP, Little JB. 1992a. Delayed reproductive death as a dominant phenotype in cell clones surviving X-irradiation. Carcinogenesis. 13(6):923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WP, Little JB. 1992b. Evidence that DNA double-strand breaks initiate the phenotype of delayed reproductive death in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Radiat Res. 131(1):53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun C, Wu Y, Lee SH, Williamson EA, Reinert BL, Jaiswal AS, Nickoloff JA, Hromas RA. 2016. The homologous recombination component EEPD1 is required for genome stability in response to developmental stress of vertebrate embryogenesis. Cell Cycle. 15(7):957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. 2010. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 40(2):179–204. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R, Udit S, Batzer MA, Feschotte C. 2006. Birth of a chimeric primate gene by capture of the transposase gene from a mobile element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:8101–8106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Garcia A, Lopez-Saavedra A, Huertas P. 2014. BRCA1 accelerates CtIP-mediated DNA-end resection. Cell Rep. 9(2):451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyteir Therapeutics I 2019. A phase 1/2 study of CYT-0851, an oral RAD51 inhibitor, in B-cell malignancies and advanced solid tumors. [accessed]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03997968.

- Dahle J, Kvam E. 2003. Induction of delayed mutations and chromosomal instability in fibroblasts after UVA-, UVB-, and X-radiation. Cancer Res. 63(7):1464–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AA, Masson JY, McLlwraith MJ, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Venkitaraman AR, West SC. 2001. Role of BRCA2 in control of the RAD51 recombination and DNA repair protein. Mol Cell. 7(#2):273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haro LP, Wray J, Williamson EA, Durant ST, Corwin L, Gentry AC, Osheroff N, Lee SH, Hromas R, Nickoloff JA. 2010. Metnase promotes restart and repair of stalled and collapsed replication forks. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:5681–5691. Eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckbar D, Jeggo PA, Lobrich M. 2011. Understanding the limitations of radiation-induced cell cycle checkpoints. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 46(4):271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehe PM, Coulon S, Scaglione S, Shanahan P, Takedachi A, Wohlschlegel JA, Yates JR 3rd, Llorente B, Russell P, Gaillard PH. 2013. Regulation of Mus81-Eme1 Holliday junction resolvase in response to DNA damage. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 20(5):598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rivero J, Kohn EC. 2017. PARP inhibitors: the cornerstone of DNA repair-targeted therapies. Oncology. 31(4):265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Yan Y, Gerson SL. 2018. Advances in therapeutic targeting of the DNA damage response in cancer. DNA Repair. 66–67:24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant ST, Nickoloff JA. 2005. Good timing in the cell cycle for precise DNA repair by BRCA1. Cell Cycle. 4(9):1216–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott B, Richardson C, Jasin M. 2005. Chromosomal translocation mechanisms at intronic alu elements in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 17(6):885–894. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribano-Diaz C, Orthwein A, Fradet-Turcotte A, Xing M, Young JT, Tkac J, Cook MA, Rosebrock AP, Munro M, Canny MD et al. 2013. A cell cycle-dependent regulatory circuit composed of 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP controls DNA repair pathway choice. Mol Cell. 49(5):872–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre F, Chan A, Heyer WD, Gangloff S. 2002. Alternate pathways involving Sgs1/Top3, Mus81/Mms4, and Srs2 prevent formation of toxic recombination intermediates from single-stranded gaps created by DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99(26):16887–16892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fnu S, Williamson EA, De Haro LP, Brenneman M, Wray J, Shaheen M, Radhakrishnan K, Lee SH, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R. 2011. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 enhances DNA repair by nonhomologous end-joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108(2):540–545. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Martin MM, Regairaz M, Huang L, You Y, Lin CM, Ryan M, Kim R, Shimura T, Pommier Y et al. 2015. The DNA repair endonuclease Mus81 facilitates fast DNA replication in the absence of exogenous damage. Nat Commun. 6:6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M, Kastan MB. 2015. The DNA damage response: implications for tumor responses to radiation and chemotherapy. Annu Rev Med. 66:129–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MF, Woodgate R. 2013. Translesion DNA polymerases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 5(10):a010363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgojo L, Little JB. 1989. Expression of lethal mutations in progeny of irradiated mammalian cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 55(4):619–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grallert B, Boye E. 2008. The multiple facets of the intra-S checkpoint. Cell Cycle. 7(15):2315–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth P, Orta ML, Elvers I, Majumder MM, Lagerqvist A, Helleday T. 2012. Homologous recombination repairs secondary replication induced DNA double-strand breaks after ionizing radiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(14):6585–6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirouilh-Barbat J, Lambert S, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. 2014. Is homologous recombination really an error-free process? Front Genet. 5:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada M, Sutherland BM. 2006. Spectrum of complex DNA damages depends on the incident radiation. Radiat Res. 165(2):223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin EC, Wazer DE, Perez CA, Brady LW. 2018. Perez & Brady’s Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. Seventh ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Hengel SR, Malacaria E, Folly da Silva Constantino L, Bain FE, Diaz A, Koch BG, Yu L, Wu M, Pichierri P, Spies MA et al. 2016. Small-molecule inhibitors identify the RAD52-ssDNA interaction as critical for recovery from replication stress and for survival of BRCA2 deficient cells. Elife. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengel SR, Spies MA, Spies M. 2017. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting DNA repair and DNA repair deficiency in research and cancer therapy. Cell Chem Biol. 24(9):1101–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermetz KE, Surti U, Cody JD, Rudd MK. 2012. A recurrent translocation is mediated by homologous recombination between HERV-H elements. Mol Cytogenet. 5(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer WD, Ehmsen KT, Liu J. 2010. Regulation of homologous recombination in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 44:113–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks WM, Kim M, Haber JE. 2010. Increased mutagenesis and unique mutation signature associated with mitotic gene conversion. Science. 329(5987):82–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T, Saito S, Fujimori H, Matsushita K, Nishio T, Okayasu R, Masutani M. 2016. Radiosensitization by PARP inhibition to proton beam irradiation in cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 478(1):234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T, Shirai H, Fujimori H, Okayasu R, Sasai K, Masutani M. 2012. Radiosensitization effect of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition in cells exposed to low and high linear energy transfer radiation. Cancer Sci. 103(6):1045–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hromas R, Wray J, Lee SH, Martinez L, Farrington J, Corwin LK, Ramsey H, Nickoloff JA, Williamson EA. 2008. The human set and transposase domain protein Metnase interacts with DNA Ligase IV and enhances the efficiency and accuracy of non-homologous end-joining. DNA Repair. 7(12):1927–1937. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HJ, Peng G. 2017. Cellular responses to replication stress: Implications in cancer biology and therapy. DNA Repair. 49:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Grimm S, Smith LE, Kim PM, Nickoloff JA, Goloubeva OG, Morgan WF. 2004. Ionizing radiation induces delayed hyperrecombination in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 24:5060–5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Kim PM, Nickoloff JA, Morgan WF. 2007. Targeted and non-targeted effects of low-dose ionizing radiation on delayed genomic instability in human cells. Cancer Res. 67:1099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas P, Jackson SP. 2009. Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 284(14):9558–9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE. 2003. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 115:401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannetti SA, Zeglis BM, Zalutsky MR, Reiner T. 2020. Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and radiation therapy. Front Pharmacol. 11:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasin M, Rothstein R. 2013. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 5(11):a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass EM, Jasin M. 2010. Collaboration and competition between DNA double-strand break repair pathways. FEBS Lett. 584(17):3703–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso AA, Lopezcolorado FW, Bhargava R, Stark JM. 2019. Distinct roles of RAD52 and POLQ in chromosomal break repair and replication stress response. PLoS Genet. 15(8):e1008319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AR, Cairns J, Little JB. 1984. Timing of the steps in transformation of C3H 10T 1/2 cells by X-irradiation. Nature. 307(5946):85–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AR, Fox M, Murphy G, Little JB. 1980. Relationship between x-ray exposure and malignant transformation in C3H 10T1/2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 77(12):7262–7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-S, Chen Q, Kim S-K, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R, Georgiadis MM, Lee S-K. 2014. The DDN catalytic motif is required for Metnase functions in NHEJ repair and replication restart. J Biol Chem. 289:10930–10938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Kim SK, Hromas R, Lee SH. 2015. The SET domain Is essential for Metnase functions in replication restart and the 5’ end of SS-overhang cleavage. PLoS ONE. 10(10):e0139418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Nickoloff JA, Wu Y, Williamson EA, Sidhu GS, Reinert BL, Jaiswal AS, Srinivasan G, Patel B, Kong K et al. 2017. Endonuclease EEPD1 is a gatekeeper for repair of stressed replication forks. J Biol Chem. 292:2795–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Williamson EA, Nickoloff JA, Hromas RA, Lee SH. 2016. Metnase mediates loading of Exonuclease 1 onto single-strand overhang DNA for end resection at stalled replication forks. J Biol Chem. 292:1414–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King HO, Brend T, Payne HL, Wright A, Ward TA, Patel K, Egnuni T, Stead LF, Patel A, Wurdak H et al. 2017. RAD51 Is a selective DNA repair target to radiosensitize glioma stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 8(1):125–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD, Haber JE. 1998. Saccharomyces Ku70, Mre11/Rad50, and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 94(#3):399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Oshige M, Durant ST, Rasila KK, Williamson EA, Ramsey H, Kwan L, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R. 2005. The SET domain protein Metnase mediates foreign DNA integration and links integration to nonhomologous end-joining repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102(50):18075–18080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann CP, Jimenez-Martin A, Branzei D, Tercero JA. 2020. Prevention of unwanted recombination at damaged replication forks. Curr Genet. 66(6):1045–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw H, Lee D, Myung K. 2011. DNA-PK-dependent RPA2 hyperphosphorylation facilitates DNA repair and suppresses sister chromatid exchange. PLoS ONE. 6(6):e21424. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linstadt DE, Castro JR, Phillips TL. 1991. Neon ion radiotherapy: results of the phase I/II clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 20(4):761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JB, Gorgojo L, Vetrovs H. 1990. Delayed appearance of lethal and specific gene mutations in irradiated mammalian cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 19(6):1425–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Opiyo SO, Manthey K, Glanzer JG, Ashley AK, Troksa K, Shrivastav M, Nickoloff JA, Oakley GG. 2012. Distinct roles for DNA-PK, ATM, and ATR in RPA phosphorylation and checkpoint activation in response to replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:10780–10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y-C, Paffett KS, Amit O, Clikeman JA, Sterk R, Brenneman MA, Nickoloff JA. 2006. Sgs1 regulates gene conversion tract lengths and crossovers independently of its helicase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 26:4086–4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makharashvili N, Paull TT. 2015. CtIP: A DNA damage response protein at the intersection of DNA metabolism. DNA Repair. 32:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malacaria E, Franchitto A, Pichierri P. 2017. SLX4 prevents GEN1-dependent DSBs during DNA replication arrest under pathological conditions in human cells. Sci Rep. 7:44464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malacaria E, Honda M, Franchitto A, Spies M, Pichierri P. 2020. Physiological and pathological roles of RAD52 at DNA replication forks. Cancers. 12(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malacaria E, Pugliese GM, Honda M, Marabitti V, Aiello FA, Spies M, Franchitto A, Pichierri P. 2019. Rad52 prevents excessive replication fork reversal and protects from nascent strand degradation. Nat Commun. 10(1):1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayle R, Campbell IM, Beck CR, Yu Y, Wilson M, Shaw CA, Bjergbaek L, Lupski JR, Ira G. 2015. DNA REPAIR. Mus81 and converging forks limit the mutagenicity of replication fork breakage. Science. 349(6249):742–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick CJ, Jackson D, Diffley JF. 2004. Visualization of altered replication dynamics after DNA damage in human cells. J Biol Chem. 279(19):20067–20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl J, Zimmer J, Tarsounas M. 2016. Interplay between Fanconi anemia and homologous recombination pathways in genome integrity. EMBO J. 35(9):909–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa K, Tsuruga T, Kinomura A, Usui K, Katsura M, Tashiro S, Mishima H, Tanaka K. 2002. A role for RAD54B in homologous recombination in human cells. EMBO J. 21(1–2):175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan WF. 2003a. Non-targeted and delayed effects of exposure to ionizing radiation: I. Radiation-induced genomic instability and bystander effects in vitro. Radiat Res. 159(5):567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan WF. 2003b. Non-targeted and delayed effects of exposure to ionizing radiation: II. Radiation-induced genomic instability and bystander effects in vivo, clastogenic factors and transgenerational effects. Radiat Res. 159(5):581–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss RL. 2014. Critical review, with an optimistic outlook, on Boron Neutron Capture Therapy (BNCT). Appl Radiat Isot. 88:2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynahan ME, Jasin M. 2010. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11(3):196–207. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins EA, Rodriguez AA, Bradley NP, Eichman BF. 2019. Emerging roles of DNA glycosylases and the base excision repair pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 44(9):765–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju G, Hartlerode A, Kwok A, Chandramouly G, Scully R. 2009. XRCC2 and XRCC3 regulate the balance between short- and long-tract gene conversions between sister chromatids. Mol Cell Biol. 29(15):4283–4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju G, Odate S, Xie A, Scully R. 2006. Differential regulation of short- and long-tract gene conversion between sister chromatids by Rad51C. Mol Cell Biol. 26(21):8075–8086. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim V, Wilhelm T, Debatisse M, Rosselli F. 2013. ERCC1 and MUS81-EME1 promote sister chromatid separation by processing late replication intermediates at common fragile sites during mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 15(8):1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan V, Lobachev KS. 2007. Intrachromosomal gene amplification triggered by hairpin-capped breaks requires homologous recombination and is independent of nonhomologous end-joining. Cell Cycle. 6(15):1814–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff JA. 2017. Paths from DNA damage and signaling to genome rearrangements via homologous recombination. Mutat Res. 806:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff JA, Jones D, Lee S-H, Williamson EA, Hromas R. 2017. Drugging the cancers addicted to DNA repair. J Natl Cancer Inst. 109:djx059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff JA, Sharma N, Taylor L. 2020a. Clustered DNA double-strand breaks: biological effects and relevance to cancer radiotherapy. Genes. 11(1):99–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff JA, Taylor L, Sharma N, Kato TA. 2020b. Exploiting DNA repair pathways for tumor sensitization, mitigation of resistance, and normal tissue protection in radiotherapy. Cancer Drug Res 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ. 2015. Targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Mol Cell. 60(4):547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SD, Lao JP, Hwang PY, Taylor AF, Smith GR, Hunter N. 2007. BLM ortholog, Sgs1, prevents aberrant crossing-over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell. 130(2):259–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okayasu R, Okada M, Okabe A, Noguchi M, Takakura K, Takahashi S. 2006. Repair of DNA damage induced by accelerated heavy ions in mammalian cells proficient and deficient in the non-homologous end-joining pathway. Radiat Res. 165(1):59–67. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer O, Hickson ID. 2018. Pathways for maintenance of telomeres and common fragile sites during DNA replication stress. Open Biol. 8(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasero P, Vindigni A. 2017. Nucleases Acting at Stalled Forks: How to Reboot the Replication Program with a Few Shortcuts. Annu Rev Genet. 51:477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastushok L, Fu Y, Lin L, Luo Y, DeCoteau JF, Lee K, Geyer CR. 2019. A novel cell-penetrating antibody fragment inhibits the DNA repair protein RAD51. Sci Rep. 9(1):11227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe A, West SC. 2014a. MUS81-EME2 promotes replication fork restart. Cell Rep. 7(4):1048–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe A, West SC. 2014b. Substrate specificity of the MUS81-EME2 structure selective endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(6):3833–3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilie PG, Tang C, Mills GB, Yap TA. 2019. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 16(2):81–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SN, Willers H, Xia F. 2002. BRCA2 keeps Rad51 in line: high-fidelity homologous recombination prevents breast and ovarian cancer? Mol Cell. 10:1262–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado F 2018. Homologous recombination: to fork and beyond. Genes. 9(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigvert JC, Sanjiv K, Helleday T. 2016. Targeting DNA repair, DNA metabolism and replication stress as anti-cancer strategies. FEBS J. 283(2):232–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynard S, Bussen W, Sung P. 2006. A double Holliday junction dissolvasome comprising BLM, topoisomerase IIIalpha, and BLAP75. J Biol Chem. 281(20):13861–13864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reams AB, Roth JR. 2015. Mechanisms of gene duplication and amplification. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 7(2):a016592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijkers T, Vandenouweland J, Morolli B, Rolink AG, Baarends WM, Vansloun PPH, Lohman PHM, Pastink A. 1998. Targeted inactivation of mouse RAD52 reduces homologous recombination but not resistance to ionizing radiation. Mol Cell Biol. 18(#11):6423–6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K, Kodama S, Suzuki K, Watanabe M. 1999. Delayed cell death, giant cell formation and chromosome instability induced by X-irradiation in human embryo cells. J Radiat Res. 40(4):311–322. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, Lukas J, Jackson SP. 2007. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 450(7169):509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully R, Panday A, Elango R, Willis NA. 2019. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20(11):698–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Speed MC, Allen CP, Maranon DG, Williamson E, Singh S, Hromas R, Nickoloff JA. 2020. Distinct roles of structure-specific endonucleases EEPD1 and Metnase in replication stress responses. NAR Cancer. 2(2):zcaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Denison K, Lobb R, Gatewood JM, Chen DJ. 1995. The human and mouse homologs of the yeast RAD52 gene: cDNA cloning, sequence analysis, assignment to human chromosome 12p12.2-p13, and mRNA expression in mouse tissues. Genomics. 25(1):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastav M, Miller CA, De Haro LP, Durant ST, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Nickoloff JA. 2009. DNA-PKcs and ATM co-regulate DNA double-strand break repair. DNA Repair. 8(8):920–929. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol O, Scifoni E, Tinganelli W, Kraft-Weyrather W, Wiedemann J, Maier A, Boscolo D, Friedrich T, Brons S, Durante M et al. 2017. Oxygen beams for therapy: advanced biological treatment planning and experimental verification. Phys Med Biol. 62(19):7798–7813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda E, Sasaki MS, Buerstedde JM, Bezzubova O, Shinohara A, Ogawa H, Takata M, Yamaguchiiwai Y, Takeda S. 1998. Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death. EMBO J. 17(#2):598–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriou SK, Kamileri I, Lugli N, Evangelou K, Da-Re C, Huber F, Padayachy L, Tardy S, Nicati NL, Barriot S et al. 2016. Mammalian RAD52 functions in break-induced replication repair of collapsed DNA replication forks. Mol Cell. 64(6):1127–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathern JN, Shafer BK, McGill CB. 1995. DNA synthesis errors associated with double-strand-break repair. Genetics. 140(3):965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturzenegger A, Burdova K, Kanagaraj R, Levikova M, Pinto C, Cejka P, Janscak P. 2014. DNA2 cooperates with the WRN and BLM RecQ helicases to mediate long-range DNA end resection in human cells. J Biol Chem. 289(39):27314–27326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweasy JB. 2020. DNA polymerase kappa: Friend or foe? Sci Signal. 13(629). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington LS. 2016. Mechanism and regulation of DNA end resection in eukaryotes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 51(3):195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Kubo M, Ma H, Nakagawa A, Yoshida Y, Isono M, Kanai T, Ohno T, Furusawa Y, Funayama T et al. 2014. Nonhomologous end-joining repair plays a more important role than homologous recombination repair in defining radiosensitivity after exposure to high-LET radiation. Radiat Res. 182(3):338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Gao Z, Li H, Zhang B, Wang G, Zhang Q, Pei D, Zheng J. 2015. DNA damage response--a double-edged sword in cancer prevention and cancer therapy. Cancer letters. 358(1):8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkac J, Xu G, Adhikary H, Young JT, Gallo D, Escribano-Diaz C, Krietsch J, Orthwein A, Munro M, Sol W et al. 2016. HELB is a feedback inhibitor of DNA end resection. Mol Cell. 61(3):405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomimatsu N, Mukherjee B, Harris JL, Boffo FL, Hardebeck M, Potts PR, Khanna KK, Burma S. 2017. DNA damage-induced degradation of EXO1 limits DNA end resection to ensure accurate DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 292(26):10779–10790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu X, Kahila MM, Zhou Q, Yu J, Kalari KR, Wang L, Harmsen WS, Yuan J, Boughey JC, Goetz MP et al. 2018. ATR inhibition is a promising radiosensitizing strategy for triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 17(11):2462–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchick A, Hegan DC, Jensen RB, Glazer PM. 2017. A cell-penetrating antibody inhibits human RAD51 via direct binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(20):11782–11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchick A, Liu Y, Zhao W, Cohen I, Glazer PM. 2019. Synthetic lethality of a cell-penetrating anti-RAD51 antibody in PTEN-deficient melanoma and glioma cells. Oncotarget. 10(13):1272–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutt A, Bertwistle D, Valentine J, Gabriel A, Swift S, Ross G, Griffin C, Thacker J, Ashworth A. 2001. Mutation in Brca2 stimulates error-prone homology-directed repair of DNA double-strand breaks occurring between repeated sequences. EMBO J. 20:4704–4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutt A, Gabriel A, Bertwistle D, Connor F, Paterson H, Peacock J, Ross G, Ashworth A. 1999. Absence of brca2 causes genome instability by chromosome breakage and loss associated with centrosome amplification. Curr Biol. 9:1107–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SS. 2014. Base excision repair: a critical player in many games. DNA Repair. 19:14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SS. 2021. Molecular radiobiology and the origins of the base excision repair pathway - an historical perspective. Int J Radiat Biol. *in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhang X, Wang P, Yu X, Essers J, Chen D, Kanaar R, Takeda S, Wang Y. 2010. Characteristics of DNA-binding proteins determine the biological sensitivity to high-linear energy transfer radiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(10):3245–3251. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JF. 2000. Complexity of damage produced by ionizing radiation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 65:377–382. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J, Liu J, Nickoloff JA, Shen Z. 2008. Distinct RAD51 associations with RAD52 and BCCIP in response to DNA damage and replication stress. Cancer Res. 68(8):2699–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J, Williamson EA, Fnu S, Lee S-H, Libby E, Willman CL, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R. 2009a. Metnase mediates chromosome decatenation in acute leukemia cells. Blood. 114:1852–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J, Williamson EA, Royce M, Shaheen M, Beck BD, Lee SH, Nickoloff JA, Hromas R. 2009b. Metnase mediates resistance to topoisomerase II inhibitors in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 4(4):e5323. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WD, Shah SS, Heyer WD. 2018. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 293(27):10524–10535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X 2019. Replication stress response links RAD52 to protecting common fragile sites. Cancers. 11(10):1467–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Lee SH, Williamson EA, Reinert BL, Cho JH, Xia F, Jaiswal AS, Srinivasan G, Patel B, Brantley A et al. 2015. EEPD1 rescues stressed replication forks and maintains genome stability by promoting end resection and homologous recombination repair. PLoS Genet. 11(12):e1005675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt HD, Sarbajna S, Matos J, West SC. 2013. Coordinated actions of SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 for Holliday junction resolution in human cells. Mol Cell. 52(2):234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Taki T, Yagi H, Habu T, Yoshida K, Yoshimura Y, Yamamoto K, Matsushiro A, Nishimune Y, Morita T. 1996. Cell cycle-dependent expression of the mouse Rad51 gene in proliferating cells. Mol Gen Genet. 251:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Jeffrey PD, Miller J, Kinnucan E, Sun Y, Thoma NH, Zheng N, Chen PL, Lee WH, Pavletich NP. 2002. BRCA2 function in DNA binding and recombination from a BRCA2-DSS1-ssDNA structure. Science. 297:1837–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara T, Suzuki T, Katsura M, Miyagawa K. 2014. Rad54B serves as a scaffold in the DNA damage response that limits checkpoint strength. Nat Commun. 5:5426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazinski SA, Zou L. 2016. Functions, regulation, and therapeutic implications of the ATR checkpoint pathway. Annu Rev Genet. 50:155–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeeles JT, Poli J, Marians KJ, Pasero P. 2013. Rescuing stalled or damaged replication forks. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 5(5):a012815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino H, Kashiwakura I. 2017. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in ionizing radiation-induced upregulation of cell surface Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 expression in human monocytic cells. J Radiat Res. 58(5):626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Sekine E, Fujimori A, Ochiya T, Okayasu R. 2008. Down regulation of BRCA2 causes radio-sensitization of human tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 99(4):810–815. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman MK, Cimprich KA. 2014. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat Cell Biol. 16(1):2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Fan HY, Goldman JA, Kingston RE. 2007. Homology-driven chromatin remodeling by human RAD54. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 14(5):397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Kim W, Kloeber JA, Lou Z. 2020. DNA end resection and its role in DNA replication and DSB repair choice in mammalian cells. Exp Mol Med. 52(10):1705–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Howard ME, Tu X, Zhu Q, Denbeigh JM, Remmes NB, Herman MG, Beltran CJ, Yuan J, Greipp PT et al. 2021. Inhibition of ATM induces hypersensitivity to proton irradiation by upregulating toxic end joining. Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M, Lottersberger F, Buonomo SB, Sfeir A, de Lange T. 2013. 53BP1 regulates DSB repair using Rif1 to control 5’ end resection. Science. 339(6120):700–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]