Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive facultative intracellular pathogen, produces two distinct phospholipases C. PC-PLC, encoded by plcB, is a broad-range phospholipase, whereas PI-PLC, encoded by plcA, is specific for phosphatidylinositol. It was previously shown that PI-PLC plays a role in efficient escape of L. monocytogenes from the primary phagosome. To further understand the function of PI-PLC in intracellular growth, site-directed mutagenesis of plcA was performed. Two potential active-site histidine residues were mutated independently to alanine, serine, and phenylalanine. With the exception of the activity of the enzyme containing H38F, which was unstable, the PI-PLC enzyme activities of culture supernatants containing each mutant enzyme were <1% of wild-type activity. In addition, the levels of expression of the mutant PI-PLC proteins were equivalent to wild-type expression. Derivatives of L. monocytogenes containing these specific plcA mutations were found to have phenotypes similar to that of the plcA deletion strain in an assay for escape from the primary vacuole, in intracellular growth in a murine macrophage cell line, and in a plaquing assay for cell-to-cell spread. Thus, catalytic activity of PI-PLC is required for all its intracellular functions.

Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipases C (PI-PLC) are secreted by several gram-positive bacteria, including Bacillus cereus, Bacillus thuringiensis, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium novyi, and Staphylococcus aureus. Except for the two proteins from the Bacillus spp., which are almost identical in amino acid sequence, amino acid identities among the other proteins for which sequences are known range from 21 to 40% (25). Bacterial PI-PLC are highly specific for PI and show no activity on PI-4-P or PI-4,5-P2. The latter two are cleaved by eukaryotic phospholipases, giving rise to the important intracellular messengers diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-P3 from PI-4,5-P2 (26, 27). Bacterial PI-PLC can also cleave the glycerol-P bond in glycosyl-PI anchors (GPI anchors) (8, 22).

L. monocytogenes PI-PLC, a 33-kDa protein, is encoded by plcA, one of six genes in a small chromosomal cluster positively regulated by PrfA (28). PI-PLC of L. monocytogenes was first identified based on sequence homology with the two enzymes from Bacillus spp. (3, 21, 24) and purified from supernatants produced by an overexpressing L. monocytogenes strain (13). It is the most basic among the bacterial PI-PLC, is activated by salts including divalent cations, and has relatively weak activity on a variety of GPI anchors (11, 13).

L. monocytogenes invades a wide variety of eukaryotic cells. When taken up by macrophages, one of the first cell types it encounters in an infected host, it escapes from the primary vacuole, thereby avoiding destruction by the phagolysosome (7, 10, 36). Upon escape, the bacterium facilitates its motility in eukaryotic cells by recruiting host actin, leading to the eventual formation of a filopodium containing a bacterium, which is then engulfed by a neighboring cell (36). The bacterium is then surrounded by a double-membrane vacuole from which it can escape. Genetic experiments have shown that a pore-forming sulfhydryl-activated hemolysin, listeriolysin O (LLO), is essential for escape from the primary vacuole and is aided in this process by PI-PLC (5). PI-PLC also appears to play a role in escape from the double-membrane secondary vacuole (33).

Previous work on PI-PLC function was performed with strains containing an in-frame deletion in plcA (5, 15, 33). In this study we have performed site-specific mutagenesis designed to permit expression of full-length inactive PI-PLC. This was accomplished by changing two histidines, thought to be in the active site. These residues are highly conserved in all PI-PLC, including the mammalian forms (16). Previous to the initiation of our work, these histidines had been mutated to phenylalanine in mammalian PLC-γ1, with a resulting loss of activity (34). Our studies confirm the importance of these histidines for enzyme activity and demonstrate that with regard to PI-PLC activity these mutants are fully defective in escape from the primary vacuole, growth in the host cell, and cell-to-cell spread.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The wild-type L. monocytogenes was strain 10403S (2). All L. monocytogenes derivatives were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and were maintained on BHI agar. The Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Life Technologies) was used for routine maintenance and construction of plasmids and was grown in liquid Luria-Bertani or on Luria-Bertani agar. E. coli strains containing pKSV7 derivatives were grown in the presence of 50 μg of ampicillin per ml.

TABLE 1.

Properties of L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Strain | Characteristics | % PI-PLC activity | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10403S | Wild type | 100 | 29 |

| DP-L1552 | ΔplcA | <1 | 5 |

| DP-L3432 | PI-PLC H38A | <1 | This study |

| DP-L2998 | PI-PLC H38F | 1.6 | This study |

| DP-L3434 | PI-PLC H38S | <1 | This study |

| DP-L3430 | PI-PLC H86A | <1 | This study |

| DP-L2997 | PI-PLC H86F | <1 | This study |

| DP-L3448 | PI-PLC H86S | <1 | This study |

| DP-L1935 | ΔplcB | 100 | 33 |

| DP-L1936 | ΔplcA, ΔplcB | <1 | 33 |

| DP-L3433 | PI-PLC H38A ΔplcB | <1 | This study |

| DP-L3435 | PI-PLC H38S ΔplcB | NDa | This study |

| DP-L3431 | PI-PLC H86A ΔplcB | <1 | This study |

| DP-L3449 | PI-PLC H86S ΔplcB | <1 | This study |

ND, not determined.

Construction of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC mutant derivatives.

The L. monocytogenes 10403S plcA gene used in this study originated from the chromosomal clone pDP1228 obtained from Daniel A. Portnoy (University of California, Berkeley). The plasmid pDP1228 was originally derived from a Tn917-LTV3 insertion into the 10403S chromosome as previously described (4). Restriction mapping of pDP1228 determined that this clone contained complete copies of the plcA and hlyA genes and an incomplete mpl gene. The plcA gene was subcloned from pDP1228 into pBluescript II KS(−) on a 2.1-kb fragment utilizing a SalI site located within Tn917-LTV3 and an EcoRI site located in hlyA. This clone, pDP2910, contains a complete copy of the plcA gene. The nucleotide sequence of the entire plcA gene was determined by using the Sequenase version 2.0 kit (United Biochemical Corp.). Site-directed mutagenesis of the plcA gene was performed by using the U.S.E. mutagenesis kit (Pharmacia). The selection primer used (CTGCAGCCCGGGGGATATCGTAGTTCTAGAGCGGCC) changed an EcoRV site to an SpeI site. The following mutagenesis primers were used: for H38A, GCTCATCGTATCTGCTGTACCTGGTAT; for H38F, GCTCATCGTATCAAATGTACCTGGTAT; for H38S, GCTCATCGTATCTGACGTCCCTGGTATAGA; for H86A, ATAAATTGGCCCTGCGTAAATTTTGAG; for H86F, ATAAATTGGCCCAAAGTAAATTTTGAG; and for H86S, TAAATAAATTGGTCCTGAGTAAATTTTGAG. All mutated plcA genes were confirmed by sequencing and subcloned into the shuttle vector pKSV7. Allelic exchange was performed as previously described (5).

PI-PLC activity assays.

L. monocytogenes supernatants were analyzed for PI-PLC enzymatic activity by using the previously described procedure (5, 13). Briefly, [3H-inositol]PI is suspended in deoxycholate-Tris buffer, pH 7.2, and incubated with bacterial supernatants from cells grown for 5 to 6 h in BHI broth with shaking. The unhydrolyzed lipid is extracted with chloroform–methanol–HCl, and the water-soluble [3H]inositol phosphate is measured in a liquid scintillation spectrometer. Each strain was assayed three times, and the results are presented as percentages of the PI-PLC activity present in supernatants of the wild-type strain which were measured in parallel.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunodetection of PI-PLC from culture supernatants and infected cells.

Proteins secreted from the wild-type L. monocytogenes 10403S and derivatives were precipitated with trichloracetic acid, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.) as previously described (23). The PI-PLC protein was detected by using rabbit polyclonal anti-PI-PLC antibodies from this laboratory. Immunoprecipitation of PI-PLC from infected J774 cell monolayers was performed as previously described (23).

Growth and escape from the vacuole in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages.

Intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes in bone marrow macrophages was measured as previously described (19, 29). The fraction of bacteria that had escaped from the primary vacuole was inferred by calculating the percentage of internalized bacteria that costained for polymerized actin with rhodamine phalloidin at 1.5 h after infection (20).

Plaquing of PI-PLC mutants in L2 cells.

Plaque formation in mouse fibroblast L2 cells was evaluated as previously described (20, 35). Plaques were visualized in infected monolayers by overlaying with medium containing 1% agarose and 0.2% neutral red. The resultant plaques were measured after projection of the plate by an overhead projector (33). For each strain the average of the diameters of 10 plaques was determined. The relative plaque size for each strain is reported as a percentage of the wild-type plaque size and is the average of three independent experiments.

RESULTS

L. monocytogenes PI-PLC mutant derivatives. (i) Effects on catalytic activity.

For these studies, a cloned copy of the wild-type plcA gene from L. monocytogenes 10403S was obtained and completely sequenced. This revealed, as expected, a high degree of similarity to the previously sequenced plcA gene from L. monocytogenes LO28, except that the mature protein contained I47M, N83K, and F90Y (24). In keeping with previous nomenclature, residue 1 is the first amino acid of the mature form of PI-PLC (13).

Alignment of the primary sequences of PI-PLC proteins from B. cereus, S. aureus (6), and L. monocytogenes revealed two histidine residues that were completely conserved, and mutation of related histidines in a mammalian PLC had been shown to result in loss of activity (34). Thus, these residues were targeted for site-directed mutagenesis. For examination of the requirement of the conserved histidine residues for PI-PLC activity, H38 and H86 were independently mutated to alanine, phenylalanine, and serine. In each case, the wild-type plcA gene was replaced by the mutant derivative by allelic exchange. This was done in both the 10403S wild-type strain and in the strain with ΔplcB, DP-L1935, previously derived from 10403S. The strains constructed are listed in Table 1.

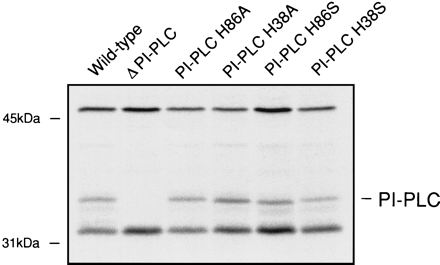

To determine the effects of mutating H38 and H86 on PI-PLC catalytic activity, assays were performed on culture supernatants. It was found that each of the mutant strains produced a less-than-detectable level of PI-PLC activity in the wild-type background with the exception of H38F, which was not studied further (see below). The expression of PI-PLC protein by each of these derivatives was examined by immunoblotting of culture supernatants. Strains harboring the PI-PLC derivatives bearing H38A, H38S, H86A, and H86S were found to produce a PI-PLC protein in amounts equivalent to that of the wild-type strain (1). However, mutation of H38 and H86 to phenylalanine led to the production of unstable forms of PI-PLC. Therefore, these strains were excluded from further experiments.

(ii) Effects on escape from a primary vacuole.

Before comparison of the host cell interactions of site-specific mutants with those of the previously studied in-frame deletion mutants, the normal expression of the mutant derivatives of PI-PLC was confirmed by immunoprecipitation following L. monocytogenes infection of J774 cells (Fig. 1). Stable proteins having the predicted size of PI-PLC were detected from strains harboring the PI-PLC derivatives H38A, H86A, H38S, and H86S.

FIG. 1.

Expression of PI-PLC in the J774 murine macrophage-like cell line. J774 cells were infected with each L. monocytogenes strain for 3.5 h, after which the cells were labelled for 1 h with [35S]methionine. PI-PLC was precipitated with rabbit polyclonal anti-PI-PLC bound to protein A-coated beads. For each lane of the resulting autoradiograph the PI-PLC phenotype of the infecting strain is indicated.

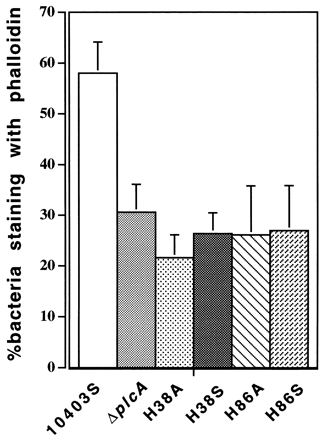

Intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes in macrophages consists of four distinct stages: initial entry into the cell by phagocytosis, escape from the primary vacuole, replication in the cytoplasm, and subsequent intercellular spread. The abilities of different L. monocytogenes derivatives to escape from the primary vacuole can be conveniently studied by using an immunofluorescence actin nucleation assay (20). This assay was shown to produce data similar to those found in earlier electron microscopic studies implicating PI-PLC in escape of L. monocytogenes from the primary vacuole (5, 33). The fraction of the histidine-mutant bacteria that was stained with fluorescent phalloidin was approximately 50% of that for the wild-type strain and indistinguishable from that for the derivative harboring an in-frame deletion of plcA (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The percentage of bacteria that escaped from the primary vacuole into the host cell cytoplasm, determined as previously described (20). Monolayers of bone marrow-derived macrophages were infected for 90 min. The total number of intracellular bacteria was obtained by staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-tagged polyclonal anti-Listeria antibody. Cytoplasmic bacteria were inferred by staining with tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-labelled phalloidin, which stains polymerized F actin.

(iii) Effects on intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes.

It is well documented that wild-type L. monocytogenes is able to replicate in bone marrow-derived macrophages, and previous studies showed that an in-frame deletion of plcA led to decreased growth (5). Most of the apparent difference reflects the deficiency in escape from the primary vacuole. We investigated the abilities of the PI-PLC mutant derivatives to grow in these cells and found that they also showed decreased growth. The observed growth rates of the strains containing PI-PLC H38A, H86A, H38S, and H86S mutations were all indistinguishable from each other and were identical to the growth rate of the strain harboring an in-frame deletion of the plcA gene (1).

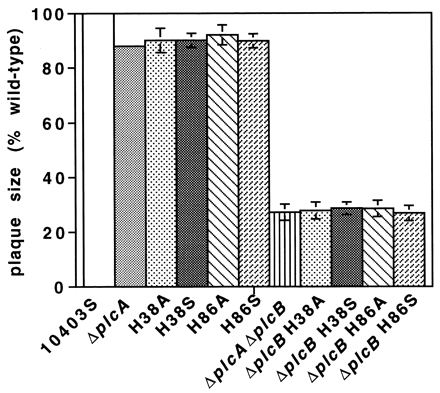

(iv) Effects on cell-to-cell spread.

Mutation of the broad-range phospholipase C of L. monocytogenes (PC-PLC) is known to decrease the ability of the bacterium to spread from cell to cell by 34%, as measured by plaque size on monolayers of L2 fibroblast cells, whereas mutation of PI-PLC results in only a 10% reduction. A double mutant lacking both phospholipases shows a 68% reduction in plaque size (5, 33). We tested the stable histidine mutants for their ability to spread from cell to cell in both the wild-type background and in a strain containing an additional in-frame plcB deletion. The plaque sizes observed for the histidine mutants in both backgrounds were identical to those obtained with strains containing in-frame deletions in plcA or in both plcA and plcB (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Plaque formation by L. monocytogenes derivatives in L2 cell monolayers. Plaquing was done as previously described (35). The size of the plaque formed by each strain was calculated as a percentage of the plaque size of the wild-type strain.

DISCUSSION

The original objectives of this research were (i) to construct stably expressed active-site mutations in L. monocytogenes PI-PLC, an important virulence factor; (ii) to verify the contributions of two conserved histidines to the active site of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC; and (iii) to learn whether a single amino acid substitution provided the same defects in biological activities of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC that had previously been observed with an in-frame deletion in this gene (5, 33). Both sequence alignments (6) and mutagenesis of conserved histidines in mammalian PLC-γ1 (34) had implicated these histidines in enzymatic activity. More-recent studies have revealed that these histidines are present in the active sites of rat PLC-δ1 (9), B. cereus PI-PLC (12, 17), and L. monocytogenes PI-PLC (25). The work presented in this paper demonstrates the need for the two mutated histidines for both the enzymatic and biological activities of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC.

Previous work done in this laboratory had indicated that L. monocytogenes PI-PLC had activities that could contribute to its biological activities other than catalysis of PI hydrolysis (14). Our finding that all the characteristics of the deletion mutant were displayed by stable histidine mutants led us to reconsider our earlier finding that L. monocytogenes PI-PLC possesses a membrane-permeabilizing activity that is separate from its catalytic activity. We produced a C-terminal his-tagged version of PI-PLC, expressed it in E. coli, and purified it by standard methods. This protein, while possessing good catalytic activity, was inactive in the membrane permeabilization assay. We then obtained recombinant wild-type L. monocytogenes PI-PLC (a generous gift of D. Heinz, University of Freiburg) and found that it too lacked membrane permeabilization activity. Lastly, we carried out additional purification of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC and were able to separate catalytic and membrane-permeabilizing activities by hydrophobic-interaction chromatography (38).

These findings and the data contained in the present work show conclusively that the catalytic activity of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC is essential for its biological activity and that two histidines conserved in all prokaryotic and eukaryotic glycerophosphoinositide-specific PLCs (16) are essential for the catalytic activity of these enzymes. This work does not rule out other features, such as specific membrane interactions, that may be unique to L. monocytogenes PI-PLC and important for its biological roles, but it provides no support for this concept.

LLO is absolutely required for escape from the primary vacuole of cells of most types (28), and mutants lacking both phospholipases manage to escape, albeit in reduced numbers (33). Thus, we are led to consider that the pore-forming ability of LLO may lead to autolysis of the phagocytic membrane as the pores become larger and more numerous or as a result of equilibration of vacuolar contents with the cytosol. It is also possible that lysis requires activation and recruitment of host proteins. The role of L. monocytogenes PI-PLC in escape from a vacuole and in cell-to-cell spread remains enigmatic. Earlier work with pure PI-PLC from B. thuringiensis had shown that it does not cause permeabilization of membranes containing 10% PI (14). As PI is a minor lipid in eukaryotic plasma membranes, its hydrolysis in the phagosome is unlikely to cause gross membrane degradation. Therefore, it is unlikely that the role of PI-PLC in escape of L. monocytogenes from a vacuole is due to membrane degradation. We have thus been led to consider the alternative possibility that PI-PLC contributes to escape from a vacuole by producing DAG (33) and possibly also cyclic inositol-1,2-P and inositol-1-P (30), all of which may be involved in intracellular signaling.

Recently, Sibelius et al. showed that human umbilical endothelial cells, which did not internalize L. monocytogenes, produced products of phosphoinositide hydrolysis when incubated with listeriae that produced LLO alone or LLO plus PI-PLC (31, 32). The two proteins produced synergistic effects on release of inositol phosphates and DAG (31, 32). Recent work in our laboratory with the J774 macrophage cell line infected with L. monocytogenes similarly shows effects of LLO and PI-PLC on PI hydrolysis and the activation of host cell phosphoinositide-specific PLC. The PI-PLC deletion mutant and strain DP-L3434 (H38S) produced similar results in these experiments (18). Parallel experiments show that intracellular calcium signaling in infected J774 cells is completely dependent on LLO expression and partly dependent on PI-PLC expression (37). We are thus led to the conclusion that a major contribution of PI-PLC is induction of host cell intracellular signaling. Our work is directed towards elucidation of the signaling pathways involved in modifying the functioning of the primary vacuole so that it does not progress to lysis of the invading bacterium. The availability of site-specific mutations will be of value in these and other future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the advice and stimulation provided by our colleagues Dan Portnoy, Wolf Zückert, Margaret Gedde, Darren Higgins, Siân Jones, Hélène Marquis, Marlena Moors, and Greg Smith. We thank Dirk Heinz for the generous gift of recombinant PI-PLC.

This research was supported by grant GM-52797 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannam, T. L., and H. Goldfine. Unpublished data.

- 2.Bishop D K, Hinrichs D J. Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes: the influence of in vitro stimulation on lymphocyte subset requirements. J Immunol. 1987;139:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilli A, Goldfine H, Portnoy D A. Listeria monocytogenes mutants lacking phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C are avirulent. J Exp Med. 1991;173:751–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilli A, Portnoy D A, Youngman P. Insertional mutagenesis of Listeria monocytogenes with a novel Tn917 derivative that allows direct cloning of DNA flanking transposon insertions. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3738–3744. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3738-3744.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camilli A, Tilney L G, Portnoy D A. Dual roles of plcA in Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daugherty S, Low M G. Cloning, expression, and mutagenesis of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C from Staphylococcus aureus: a potential staphylococcal virulence factor. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5078–5089. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5078-5089.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Chastellier C, Berche P. Fate of Listeria monocytogenes in murine macrophages: evidence for simultaneous killing and survival of intracellular bacteria. Infect Immun. 1994;62:543–553. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.543-553.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englund P T. The structure and biosynthesis of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol protein anchors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:121–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essen L-O, Perisic O, Cheung R, Katan M, Williams R L. Crystal structure of a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase Cδ. Nature (London) 1996;380:595–602. doi: 10.1038/380595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Sansonetti P. Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1986;52:50–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.50-55.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi A J, Perussia B, Goldfine H. Listeria monocytogenes phosphatidylinositol (PI)-specific phospholipase C has low activity on glycosyl-PI anchored proteins. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:8014–8017. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.8014-8017.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gässler C S, Ryan M, Liu T, Griffith O H, Heinz D W. Probing the roles of active site residues in phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C from Bacillus cereus by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12802–12813. doi: 10.1021/bi971102d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldfine H, Knob C. Purification and characterization of Listeria monocytogenes phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4059–4067. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4059-4067.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldfine H, Knob C, Alford D, Bentz J. Membrane permeabilization by Listeria monocytogenes phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C is independent of phospholipid hydrolysis and cooperative with listeriolysin O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2979–2983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Hauf N, Goebel W, Fiedler F, Sokolovic Z, Kuhn M. Listeria monocytogenes infection of P388D1 macrophages results in a biphasic NF-κB (RelA/p50) activation induced by lipoteichoic acid and bacterial phospholipases and mediated by IκBα and IκBβ degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9394–9399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinz D W, Essen L O, Williams R L. Structural and mechanistic comparison of prokaryotic and eukaryotic phosphoinositide-specific phospholipases C. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:635–650. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinz D W, Ryan M, Bullock T L, Griffith O H. Crystal structure of the phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C from Bacillus cereus in complex with myo-inositol. EMBO J. 1995;14:3855–3863. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston, N. C., and H. Goldfine. Unpublished data.

- 19.Jones S, Portnoy D A. Intracellular growth of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1994;236:463–467. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)36034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones S, Portnoy D A. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis in a strain expressing perfringolysin O in place of listeriolysin O. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5608–5613. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5608-5613.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leimeister-Wächter M, Domann E, Chakraborty T. Detection of a gene encoding a phosphatidylinositol specific phospholipase C that is co-ordinately expressed with listeriolysin in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:361–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Low M G. The glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor of membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;988:427–454. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marquis H, Goldfine H, Portnoy D A. Proteolytic pathways of activation and degradation of a bacterial phospholipase C during intracellular infection by Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1381–1392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mengaud J, Braun-Breton C, Cossart P. Identification of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C activity in Listeria monocytogenes: a novel type of virulence factor. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:367–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moser J, Gerstel B, Meyer J E W, Chakraborty T, Wehland J, Heinz D W. Crystal structure of the phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C from the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:269–282. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portnoy D A, Chakraborty T, Goebel W, Cossart P. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1263–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1263-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portnoy D A, Jacks P S, Hinrichs D J. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross T S, Wang F P, Majerus P W. Mammalian cells that express Bacillus cereus phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C have increased levels of inositol cyclic 1:2-phosphate, inositol 1-phosphate, and inositol 2-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19919–19923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sibelius U, Chakraborty T, Krögel B, Wolf J, Rose F, Schmidt R, Wehland J, Seeger W, Grimminger F. The listerial exotoxins listeriolysin and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C synergize to elicit endothelial cell phosphoinositide metabolism. J Immunol. 1996;157:4055–4060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibelius U, Rose F, Chakraborty T, Darji A, Wehland J, Weiss S, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Listeriolysin is a potent inducer of the phosphatidylinositol response and lipid mediator generation in human endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:674–676. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.674-676.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith G A, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston N C, Portnoy D A, Goldfine H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4231-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith M R, Liu Y-L, Matthews N T, Rhee S G, Sung W K, Kung H-F. Phospholipase Cγ1 can induce DNA synthesis by a mechanism independent of its lipase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6554–6558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun A N, Camilli A, Portnoy D A. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3770–3778. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3770-3778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tilney L G, Portnoy D A. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wadsworth, S. J., and H. Goldfine. Unpublished data.

- 38.Zhao, X., T. Bannam, and H. Goldfine. Unpublished data.