Abstract

Background

Seizures can present at any time before or after the diagnosis of a glioma. Roughly, 25%–30% of glioblastoma (GBM) patients initially present with seizures, and an additional 30% develop seizures during the course of the disease. Early studies failed to show an effect of general administration of antiepileptic drugs for glioblastoma patients, since they were unable to stratify patients into high- or low-risk seizure groups.

Methods

111 patients, who underwent surgery for a GBM, were included. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling was performed, before methylation subclasses and copy number changes inferred from methylation data were correlated with clinical characteristics. Independently, global gene expression was analyzed in GBM methylation subclasses from TCGA datasets (n = 68).

Results

Receptor tyrosine Kinase (RTK) II GBM showed a significantly higher incidence of seizures than RTK I and mesenchymal (MES) GBM (P < .01). Accordingly, RNA expression datasets revealed an upregulation of genes involved in neurotransmitter synapses and vesicle transport in RTK II glioblastomas. In a multivariate analysis, temporal location (P = .02, OR 5.69) and RTK II (P = .03, OR 5.01) were most predictive for preoperative seizures. During postoperative follow-up, only RTK II remained significantly associated with the development of seizures (P < .01, OR 8.23). Consequently, the need for antiepileptic medication and its increase due to treatment failure was highly associated with the RTK II methylation subclass (P < .01).

Conclusion

Our study shows a strong correlation of RTK II glioblastomas with preoperative and long-term seizures. These results underline the benefit of molecular glioblastoma profiling with important implications for postoperative seizure control.

Keywords: glioma, glioma-related seizures, methylation, RTKII

Key Points.

The RTK II glioblastoma methylation subclass is predictive for preoperative and postoperative seizures.

RTK II glioblastomas show an upregulation of genes related to neurotransmitter synapses and vesicle transport.

The need for antiepileptic medication and its increase due to treatment failure was highly associated with the RTK II methylation subclass.

Importance of the Study.

Seizures are a common symptom in glioma patients. Even though seizures occur more often in IDH mutant tumors, 30%–60% of glioblastoma (GBM) patients develop seizures during the course of the disease, thus affecting their quality of life and that of their peers. However, the general administration of antiepileptic medication is not recommended, mostly due to the inability of stratifying patients into low- and high-risk groups for the onset of seizures. Here, we demonstrate that the RTK II GBM methylation subclass is highly enriched for patients that have a particularly strong risk for the development of seizures. Furthermore, integrative DNA methylation and RNA expression analyses reveal an upregulation of genes related to synapses and vesicle transport in RTK II glioblastomas. Our findings therefore indicate that patients with an RTK II GBM might benefit from prophylactic antiepileptic treatment.

Seizures are a common symptom of glioma patients. They are more common in patients with low-grade or IDH-mutated gliomas, but also affect a large proportion of patients with IDH wild type glioblastoma (IDH wt GBM). Approximately 25%–30% of these patients present with seizures at initial diagnosis. Another 30% develop tumor-associated epilepsy after surgery.1,2 Seizures lead to frequent hospitalization of GBM patients and strongly affect the quality of their lives. Unfortunately, early studies have failed to show any benefit of a general, prophylactic antiepileptic therapy. Instead, adverse effects of an antiepileptic therapy range from psychiatric and behavioral effects to interactions with chemotherapies through cytochrome P450 (CYP450) induction or inhibition. Such therapy for all GBM patients is therefore not recommended in the updated SNO and EANO guideline.3–5 However, the identification of patients at high risk for seizure development is still highly desired.6

Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling has recently been developed into a tool that allows the exact molecular classification of central nervous system tumors with the potential to further stratify patients for postoperative therapies.7 Through DNA methylation profiling glioblastomas can be subclassified in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) I, RTKII, RTK III, H3.3. G34-mutant, midline, MYCN and mesenchymal (MES). In adults the three most common methylation subclasses are RTK I, RTK II, and MES. RTK I tumors are enriched for platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) gene amplification, whereas RTK II tumors frequently harbor amplification of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene, while MES tumors have no typical recurrent mutations.8–10 Even though an overlap was reported between the methylation-based subclassification and transcriptome analysis, DNA methylation does not match with RNA-based subclasses or the proteogenomic and metabolomic landscape of glioblastomas.10 Nevertheless, thus far no real translation to the clinical practice from these extensive subclassification has been achieved. Previous studies linked various DNA methylation patterns with epileptiform activity and offered novel opportunities to understand genetic drivers of epilepsy.11,12 Vasudevaraja and colleagues identified an upregulation of receptor tyrosine kinase genes (RTK), such as EGFR and PDGFRA, in resection specimens of patients with focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) that presented with seizures.13 Furthermore, Choi et al. showed an association of amplification of RTK genes, mainly MET, with intraoperative seizures during glioma resection.14 However, the relation between the global DNA methylation profile and tumor-related epilepsy in glioblastoma is still unclear.

Here, we show that the RTK II GBM wt subclass, identified by genome-wide DNA methylation, experiences significantly more seizures than other common GBM subclasses. We further show that the RTK II subclass correlates with a transcriptional deregulation of synaptic genes. Through methylation classification, we therefore provide the basis for the molecular stratification of GBM patients that harbor a high potential for seizures and might therefore benefit from prophylactic antiepileptic treatment.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Glioma tissue from n = 111 patients undergoing surgery with the diagnosis of isocitrate-dehydrogenase (IDH)-wild type glioblastoma was obtained as approved by the medical ethics committee of the Hamburg chamber of physicians (PV4904). Informed written consent was obtained from all patients. Diagnosis was based on the current WHO classification for central nervous tumors.15 Clinical characteristics were prospectively recorded and retrospectively analyzed. Types of seizures and use of antiepileptic medication were defined according to the current guidelines of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE).16 Postoperative seizure outcome was recorded based on patient self-reporting and reports of relatives without confirmatory electrophysiological data analysis. All patients were seen in our neurooncological outpatient clinic at regular interviews every 3 months. The extent of resection was stratified into gross total resection (GTR), near GTR, partial resection (PR), and stereotactic biopsy. A GTR was defined as a complete removal of contrast-enhancing parts, a near GTR as a removal of more than 90% of the contrast-enhancing parts, whereas a resection of lower than 90% was defined as PR. The extent of resection of contrast-enhancing parts was evaluated in the MRI up to 48 h after surgery.

DNA Methylation Profiling

DNA was extracted from tumors and analyzed for genome-wide DNA methylation patterns using the Illumina EPIC (850k) array. Processing of DNA methylation data was performed with custom approaches as previously described. Classification was performed using the brain tumor classifier of the Deutsche Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ). The evaluation of the MGMT promoter methylation status was made according to the MGMT-STP27 method of the DKFZ classifier output.

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as previously described.17 Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) from 29 Tumor samples. RNA concentration was quantified using NanoDrop RNA 6000 nanoassays and analyzed using the STEP one PLUS Applied Biosystems PCR machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). mRNA expression analysis was carried out using Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The following primer pairs were purchased from Thermo Fisher: HTR2A (#Hs06626790_s1); SLC32A1 (#Hs00369773_m1); SNAP25 (#Hs00938957_m1); SV2C (#Hs01026335_m1); SYT4 (#Hs01086433_m1). Relative amounts of target mRNA were normalized to 18S as internal control (∆CT). Values were calibrated according to the ΔΔCT method, and relative quantity (RQ) values were calculated by normalizing each CT value to the mean CT value of all samples.

Gene Alteration Analyses

Genome-wide DNA methylation was used to analyze structural alterations in the tumor genome and to provide information regarding gene amplifications and losses as routinely done by the tumor classifier of the DKFZ. For the assessment of relevant deviations, we followed the recommendations as described by Capper et al. using a focal shifting of the gene locus above a log2 value of 0.4.17

3D Volumetric Segmentation

We analyzed T1-weighted as well as T2-weighted Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) axial images of all GBM patients before surgery. The program BRAINLAB was used for all analyses. To measure tumor volume, the tumor region of interest was delineated with the tool “Smart Brush” in every slice by hand, enabling a multiplanar 3D reconstruction. With this methodology, the volume of contrast enhancement and of FLAIR hyperintensity was assessed in cm3.

TCGA Data Use

Data were downloaded from the TCGA database (https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga). We classified the methylation data based on the tumor classifier of the DKFZ. We used the AutoPipe (CRAN) to identify marker gene expression from each methylation subgroup. Gene Set Enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed for functional annotations as described recently.18

Statistical Analysis

Differences in continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test and differences in proportions were analyzed with the chi-square-test or Fisher exact test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the effects of variables on seizure outcome and to compute odds ratio (OR). A two-sided P-value less than .05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA).

Availability of Data

The raw methylation IDAT files and patients data are available via gene expression omnibus (GEO) indexed as GSE188547.

Results

Study Population

A total of n = 111 patients, who had been diagnosed with isocitrate-dehydrogenase (IDH)-wild type glioblastoma, were enrolled in this study. Mean age of the study population was 61.9 years (range 34–84 years). 46 patients (41.4%) were female. A gross or near gross total resection (GTR) was achieved in 58.5% of the patients, whereas 22.5% underwent biopsy only (Table 1). 57 patients (51.4%) had a methylated O6-methylguanine DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Population With the Respected Clinical Features According to their Methylation Glioblastoma Subclass

| Preoperative features | n = 111 | RTK I (n = 33) | RTK II (n = 54) | Mesenchymal (n = 24) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 61.9 (11.7) | 64.5 (10.3) | 60.1 (12.7) | 62.6 (10.8) | .21 |

| Female, n (%) | 46 (41.4) | 15 (45.5) | 20 (37.0) | 11 (45.8) | .66 |

| Preoperative Karnofsky, %, mean (SD) | 84.6 (12.7) | 82.4 (12.8) | 84.8 (12.8) | 87.1 (12.3) | .39 |

| Preoperative NANO, mean (SD) | 1.8 (2.4) | 2.1 (2.5) | 1.5 (1.7) | 2.1 (3.7) | .46 |

| Seizure-related features | |||||

| Preoperative seizures, n (%) | 36 (32.4) | 4 (12.1) | 27 (50.0) | 5 (20.8) | <.01 |

| Focal | 19 (17.1) | 3 (9.1) | 13 (24.1) | 3 (12.5) | .57 |

| FBTCS | 17 (15.3) | 1 (3.0) | 14 (25.9) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Antiepileptic medication, n (%) | |||||

| Levetiracetam | 26 (23.4) | 1 (3.0) | 21 (38.9) | 4 (16.7) | <.01 |

| Lamotrigine | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lacosamide | 1 (0.9) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Glioblastom-related features | |||||

| Location, n (%) | |||||

| Eloquent | 65 (58.6) | 20 (60.6) | 32 (59.3) | 13 (54.2) | .88 |

| Frontal | 36 (32.4) | 12 (36.4) | 15 (27.8) | 9 (37.5) | .59 |

| Parietal | 55 (49.5) | 16 (48.5) | 30 (55.6) | 9 (37.5) | .34 |

| Temporal | 44 (39.6) | 12 (36.4) | 22 (40.7) | 10 (41.7) | .89 |

| Occipital | 22 (19.8) | 7 (21.2) | 12 (22.2) | 3 (12.5) | .59 |

| Side, n (%) | |||||

| Left | 61 (55.0) | 17 (51.5) | 31 (57.4) | 13 (54.2) | .11 |

| Right | 46 (41.4) | 15 (45.5) | 23 (42.6) | 46 (41.4) | |

| Both | 4 (3.6) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Contrast enhancement, n (%) | 194 (93.7) | 32 (97.0) | 50 (92.6) | 22 (91.7) | .65 |

| Contrast enhancement volume, cm3, mean (SD) | 25.3 (25.8) | 22.2 (24.3) | 25.3 (27.6) | 30.3 (23.7) | .77 |

| Flair volume, cm3, mean (SD) | 62.8 (41.8) | 69.6 (40.6) | 52.4 (37.4) | 84.3 (49.9) | .11 |

| Extent of resection, n (%) | |||||

| GTR | 42 (37.8) | 13 (39.4) | 19 (35.2) | 10 (41.7) | .62 |

| Near GTR | 23 (20.7) | 9 (27.3) | 11 (20.4) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Partial resection | 21 (18.9) | 3 (9.1) | 13 (24.1) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Biopsy | 25 (22.5) | 8 (24.2) | 11 (20.4) | 6 (25.0) | |

| MGMT status, n (%) | |||||

| Methylated | 57 (51.4) | 17 (51.5) | 27 (50.0) | 13 (54.2) | .94 |

| Nonmethylated | 54 (48.6) | 16 (48.5) | 27 (50.0) | 11 (45.8) |

Methylation Profiles

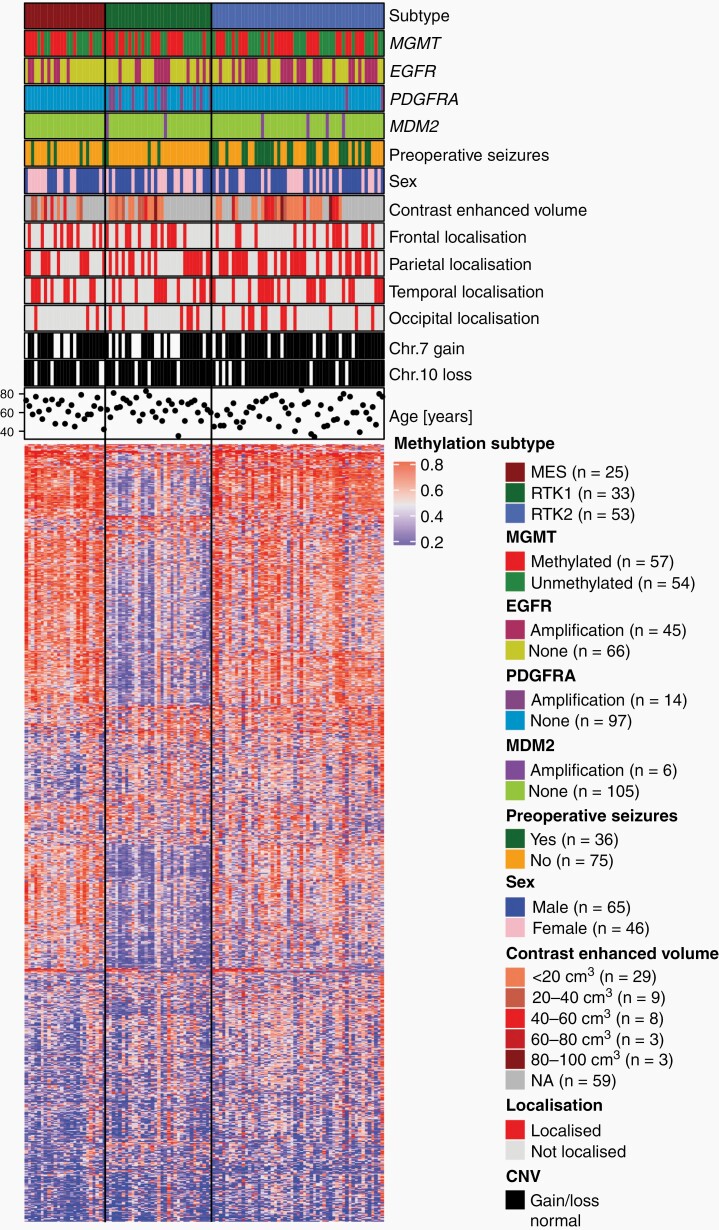

After applying DNA methylation profiling using the DKFZ methylation classifier, patients were stratified according to their methylation subclass with the result of RTK II class being the most frequent (48.6%, Table 1, Figure 1). Supervised hierarchical clustering revealed, as expected, differentially methylated genomic regions between the different glioblastoma methylation subclasses via heatmap analysis (Figure 1). Genomic alterations inferred from the methylation data showed an amplification of EGFR predominantly in RTK II glioblastomas (26/54), whereas PDGFRA amplification was predominantly seen in RTK I tumors (12/33) (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Supervised methylation subclass-based clustering of patients. Genomic alterations were inferred from genome-wide methylation data by 850K EPIC arrays. As expected, PDGFRA amplification were predominantly seen in RTK I glioblastomas, and EGFR amplification were predominantly seen in RTK II tumors. Seizures showed a strong correlation to RTK II tumors.

Basic characteristics and clinical risk factors, such as location, contrast enhancement volume, and extent of resection (EOR) did not differ between the methylation subclasses in our series (Table 1).

We identified 36 patients (32.4%), who suffered from focal or focal to bilateral tonic–clonic (FBTCS) seizure prior to surgery. Of these patients, 83.3% had to begin immediate antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment. RTK II glioblastomas showed a higher incidence of preoperative seizures (50.0%) than RTK I (12.1%) and mesenchymal (MES) glioblastomas (20.8%, P < .01) (Figure 1 and Table 1). Concurrently, the need for an AED was strongly associated with the RTK II subclass (P < .01). Levetiracetam (86.7%), lamotrigine (10.0%), and lacosamide (3.3%) were used for AED therapy. The type of seizure showed no significant association with the methylation subclasses (P = .57, Table 1). Since both RTK subclasses are known to correlate with an amplification of either PDGFRA (RTK I) or EGFR (RTK II), we hypothesized that PDGFRA or EGFR amplification are negatively (PDGFRA) or positively (EGFR) associated with preoperative seizures. Analysis of genomic alterations inferred from the global methylation profiling showed no association of PDGFRA and EGFR amplification with preoperative seizures (Supplementary Table S1). Interestingly, the MDM2 status showed a positive correlation with the onset of seizures prior to surgery (P = .04, Supplementary Table S2).

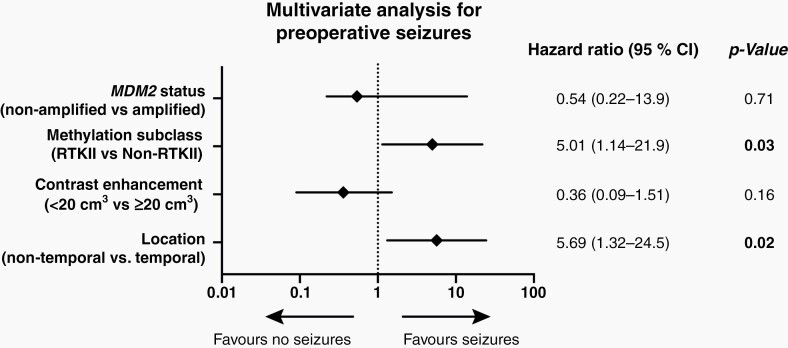

Univariate analysis including clinical and methylation-based characteristics revealed that temporal location (P = .04), RTK II subclass (P < .01), smaller tumors (<20 cm3 contrast enhancement, P = .02), and MDM2 amplification status (P = .04) were positively correlated with preoperative seizures. The multivariate analysis including relevant parameters from the univariate analysis demonstrated that only temporal location (OR = 5.69, CI = 1.32–24.5, P = .02) and the RTK II subclass (OR = 5.01, CI = 1.14–21.9, P = .03) were significantly associated with preoperative seizures (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Multivariate analysis for preoperative seizures.

Correlation of Methylation Subclass RTK II with Upregulated Genes

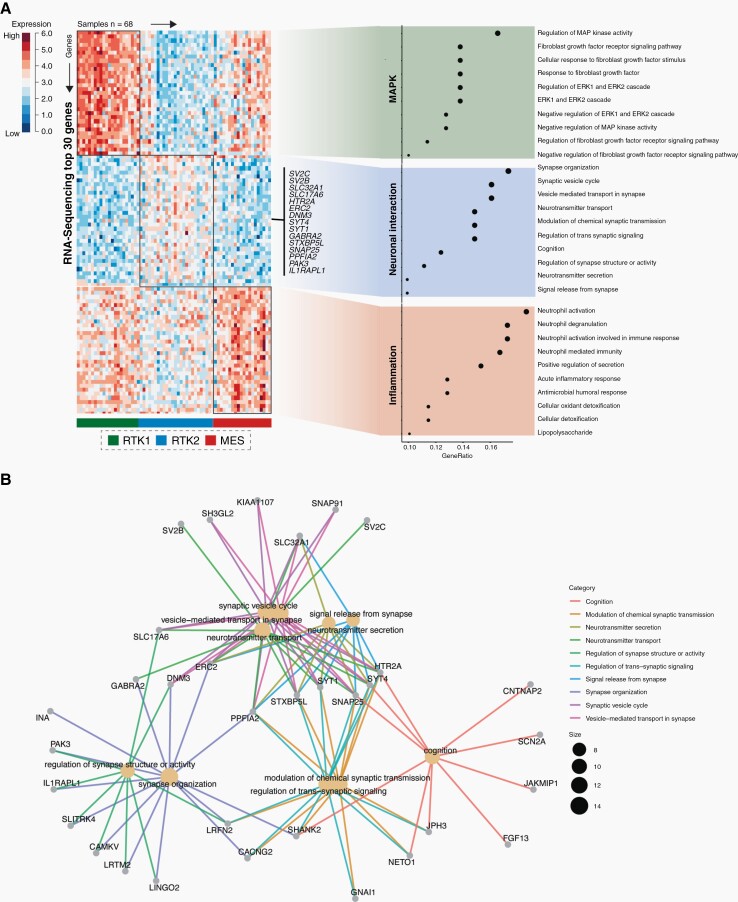

To identify transcriptional modules that rely on methylation subclasses we queried the TCGA database to identify tumors, for which DNA methylation and RNA expression datasets were available (n = 68). After vertical integration of both data modalities, we identified the methylation subclasses using the Heidelberg classifier and performed supervised clustering to determine marker gene expression across all methylation subclasses, namely the RTK I, RTK II, and MES glioblastomas (Figure 3A). Functional enrichment of the top scored genes (n = 30) revealed an enrichment of MAP Kinase pathways (pFDRP < .001) in the RTKI class, whereas the mesenchymal subclass showed alterations in gene expression of inflammation associated pathways (neutrophil activation pFDR = .002). Interestingly, RTK II tumors were marked by upregulation of genes related to neuronal interaction. We observed a prominent upregulation of synapse organization (pFDRP < .001), vesicle cycle (pFDRP < .021), and neurotransmitter transport (pFDRP < .015). This included members of the synaptic vesicle proteins 2 (SV2) family that are localized to synaptic vesicles and may function in the upregulation of vesicle trafficking as well as the solute carrier family 17 member 6 (SLC17A6) known to mediate the uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles. Additionally, SLC32A1 was upregulated in RTKII tumors, coding for an integral membrane protein involved in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine trafficking (Figure 3B). However, expression analysis of individual genes involved in synaptic and vesicle trafficking showed no correlation with the occurrence of epileptic seizures, both pre- and postoperatively (Supplementary Figure S1). This reinforces our statement that the occurrence of epileptic seizures in GBM is not determined by a single gene, but rather is due to the epigenetic profile of the tumor.

Fig. 3.

Integrative analysis of DNA methylation subclasses and RNA expression. (A) Query of the TCGA database identified 68 datasets for whom both DNA methylation and RNA expression were present. Functional enrichment of the top scored genes revealed an enrichment of MAP Kinase pathways (pFDRP < .001) in the RTK I class. RTK II tumors are marked by upregulation of genes related to neuronal interaction (pFDR p<0.001) while the mesenchymal subclass showed alterations in gene expression of inflammation associated pathways (neutrophil activation pFDR = 0.0021). An exhibit of the most differentially genes for RTK II tumors are displayed (n = 15); (B) Ontology network visualization of the most differentially expressed genes within the RTK II subclass.

Methylation Subgroup-related Seizure Outcome

Patients were followed up concerning the persistence or freedom of seizures with a mean follow-up time of 12.7 months (range: 3–64 months) (Tables 2 and 3). Of these 111 patients, 14 (12.6%) suffered from a new onset seizure during the postoperative stay and 53 (47.7 %) had a new onset or persistence of seizure during follow-up (Tables 2 and 3). As with the association for preoperative seizure, patients, who suffered from a seizure during follow-up, were more likely to be in the RTK II subclass (72.2%, P < .01). Consequently, patients in the RTK II subclass had to increase or begin an AED more often (70.4%, P < .01, Table 2).

Table 2.

Methylation Subgroup-related Outcome of All Patients

| Feature | n = 111 | RTK I (n = 33) | RTK II (n = 54) | Mesenchymal (n = 24) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure during postoperative stay, n (%) | 14 (12.6) | 1 (3.0) | 13 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | <.01 |

| Persistence or new onset of seizure until last follow-up or death, n (%) 1 | 53 (47.7) | 10 (30.3) | 39 (72.2) | 4 (16.7) | <.01 |

| Seizure-freedom until last follow-up or death, n (%) 1 | 58 (52.3) | 23 (69.7) | 15 (27.8) | 20 (83.3) | <.01 |

| Antiepileptic medication at last follow-up, n (%) | |||||

| None or unchanged | 59 (53.2) | 23 (69.7) | 16 (29.6) | 20 (83.3) | <.01 |

| Increased or additional drug | 52 (46.8) | 10 (30.3) | 38 (70.4) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Number of antiepileptic medications, n (%) | |||||

| None | 53 (47.7) | 23 (69.7) | 12 (22.2) | 18 (75.0) | <.01 |

| 1 | 52 (46.8) | 9 (27.3) | 37 (68.5) | 6 (25.0) | |

| ≥ 2 | 6 (5.4) | 1 (3.0) | 5 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) |

1 Mean (range) follow-up: all patients 12.7 months (3–64 months), RTK I: 15.8 months, RTK II: 10.9 months, MES: 12.6 months.

Table 3.

Methylation Subgroup-related Outcome of Patients With Preoperative Seizures

| Feature | n = 36 | RTK I (n = 4) | RTK II (n = 27) | Mesenchymal (n = 5) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure during postoperative stay, n (%) | 11 (30.6) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (40.7) | 0 (0.0) | .02 |

| Seizure until last follow-up or death, n (%) 1 | 21 (58.3) | 1 (25.0) | 19 (70.4) | 1 (20.0) | .04 |

| Seizure-freedom until last follow-up or death, n (%) 1 | 15 (41.7) | 3 (75.0) | 8 (29.6) | 4 (80.0) | .04 |

| Antiepileptic medication at last follow-up, n (%) | |||||

| None or unchanged | 12 (33.3) | 2 (50.0) | 6 (22.2) | 4 (80.0) | .01 |

| Increased or additional drug | 24 (66.7) | 1 (25.0) | 21 (77.8) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Number of antiepileptic medications, n (%) | |||||

| None | 7 (19.4) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (40.0) | .18 |

| 1 | 24 (66.7) | 1 (25.0) | 20 (74.1) | 3 (60.0) | |

| ≥ 2 | 5 (13.9) | 1 (25.0) | 4 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) |

1 Mean (range) follow-up: all patients 10.9 months (3–38 months), RTK I: 14.5 months, RTK II: 10.3 months, MES: 10.8 months.

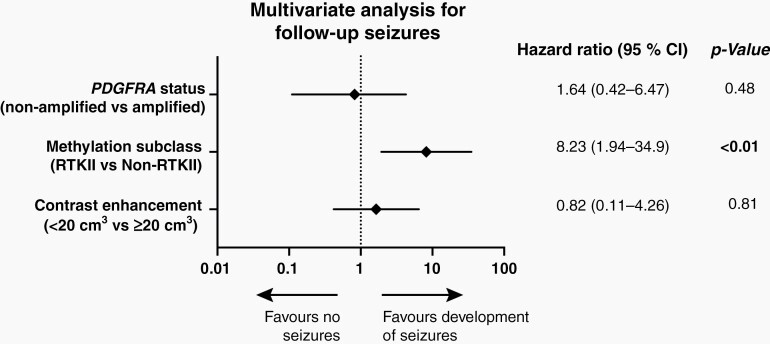

Similarly, patients with preoperative seizures more often experienced additional seizures during follow-up, if they were diagnosed with a RTK II tumor (70.4% P = .04, Table 3). With respect to gene alterations, we observed an inverse correlation with PDGFRA status with the development of seizures (P = .02), whereas no other alteration showed a correlation (Supplementary Table S4). Univariate analysis showed that again RTK II subclass (P < .01), tumor size (P < .01) and nonamplified PDGFRA status (P = .03) positively correlated with the development of seizures during follow-up (Supplementary Table S5). These results were retained in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model assessing the methylation subclass and seizure outcome (Figure 4). Multivariate analysis revealed that the RTK II subclass was the only independent factor for the development of seizures during the course of the disease (OR = 8.23, CI = 1.94–34.9, P < .01).

Fig. 4.

Multivariate analysis for follow-up seizures.

Discussion

Glioma-related seizures are a feature of at least 60% of all glioma patients.19 Factors such as temporal location and smaller tumor size were linked to the development of seizures20; however, prophylactic antiepileptic medication is not recommended in the updated SNO and EANO guideline.3–5 One underlying reason is a missing reliable stratification of patients into high- and low-risk groups for an onset of seizures. Our study presents the following major findings: (1) The RTKII glioblastoma methylation subclass is predominantly associated with preoperative and postoperative seizures; (2) RTKII glioblastoma show an upregulation of genes related to neurotransmitter synapses and vesicle transport; (3) The need for antiepileptic medication and its increase due to persistent seizures is strongly associated with the RTK II methylation subclass.

Seizures often occur in gliomas suggesting that the two conditions share common underlying pathogenic mechanism.19 Many studies suggest that the neurotransmitter glutamate plays a central role in this context and supports both the development of epilepsy and tumor progression. In low-grade gliomas the mutation of IDH causes the production of d-2-hydroxyglutarate, a steric analog of glutamate, whereas in IDH wt glioblastoma altered expression of genes of glutamate receptors leads to an excessive glutamate release that promotes glioma mitosis and migration21–23 and on the other hand causes epileptic discharge.24,25 Indeed, measurements of extracellular glutamate in glioma-surrounding tissue revealed levels that are up to 10-fold higher than nontumorous brain.26,27

Several factors cause this peritumoral glutamate accumulation. Altered glutamate homeostasis by deregulation of genes directly related to glutamate or cystine release and reuptake seems to play a major role.21,25,28,29 In accordance, we found, through methylation-based RNA expression analysis, that RTK II tumors showed a distinct transcriptional neuronal interaction module when compared to RTK I and MES tumors. Genes include members of the SV2 as well as SLC17 family that are linked to vesicle and glutamate trafficking. Next to glutamate accumulation, aberrant GABAergic mechanism and accompanying changes of intracellular chloride concentration were also described to contribute to epileptogenicity in glioma.30 In this context, SLC32A11, which encodes for a protein related to GABA trafficking was one of the most significantly dysregulated genes in RTK II tumors. Hence, our data support a global DNA methylation-based epileptogenic transcriptional module in RTK II that may explain the clinical evident association of RTK II tumors with seizures.

Genomic alterations of genes encoding for the tyrosine kinases EGFR and PDGFRA can occur in up to 90% of glioblastomas.31,32 Despite the knowledge of the effect of these alterations on tumorigenesis and progression, they have not been adequately linked to epileptogenicity in glioma. In regard to EGFR, conflicting results have been reported, most probably due to mixed cohorts of gliomas that were analyzed.33 These included low- and high-grade glioma as well as oligodendroglioma. EGFR was linked to preoperative seizures,33 whereas a different study showed no association for the prediction of intraoperative seizures in glioma.14 In accordance to the study by Choi et al., our data show no association of EGFR alterations with glioma-related seizure, even though EGFR amplification is predominantly seen in RTK II tumors, which has been described by others.7 In a nontumorous mice model, PDGFRA protein expression was shown to potentiate epilepsy in mice.34 Additionally, Vasudevaraja identified an upregulation of PDGFRA as well as EGFR, in resection specimens of patients with FCD that presented with seizures.13 However, this was not recapitulated for gliomas.14 Our data even show that a PDGFRA amplification is a negative predictor for the development of seizures in glioblastoma. Therefore, our cohort shows no evidence of association of amplified PDGFRA or EGFR status with the onset or development of seizures in glioblastoma. An altered MDM2 status was associated with preoperative seizures in univariate analysis but was not an independent factor in the multivariate analysis. Nevertheless, it must be mentioned that our study did not identify genetic alterations as the underlying biological mechanism for seizure development and the presence of seizures could rather be dependent on the DNA methylation subclass.

Besides excessive glutamate levels and genetic alterations, previous studies have reported additional nongenetic factors that correlate with an increased risk of seizure onset in gliomas. These included patient age, tumor grade, tumor location, and tumor size. As our study only consisted of WHO grade 4 glioblastomas we were unable to analyze tumor grade, but we did not find an association of patients’ age with the development of seizures. In regard to tumor size and location, we and others had already described that smaller tumor size can be a predictive marker for preoperative seizures in glioblastoma,20,35 which we recapitulated in this study. Several studies have recently highlighted the importance of interaction in the neuronal glioma environment with respect to progression and seizures. The neuronal microenvironment leading to network hyperexcitability and seizures is particularly influenced by variants of PIK3CA as presented by Yu and colleagues.36 A PIK3CA mutation in glioblastoma occurs in 8.3%–17.0% of the cases according to the current literature.36,37 Besides the groundbreaking work by Yu et al., further studies underpinned the relevance of PIK3CA-mutated glioblastoma since a mutation was associated with early tumor recurrence resulting in poorer prognosis, and inhibition of PIK3CA suppresses the intrinsic hyperactivity of mutant neurons which constitutes a new therapeutic target.37,38 In addition, Park and colleagues reported a PIK3CA-mutation in 11.7% of the mesenchymal glioblastoma and 12.7% of the classical glioblastoma.39 In silico analysis revealed no significant differences in genes related to PIK3CA activation in our dataset. Moreover, glutamergic neurogliomal synapses appear to stimulate glioma invasion and growth, which may open a new field for AMPA inhibitors.40,41 Thus, these preclinical studies showed increased seizures especially in large tumors. In our study, seizures during follow-up occurred more often in larger tumors that could indicate a morphological correlate for a pathological change in the glioma neuronal microenvironment.

Even though tumor size may correlate with glioma-associated epilepsy the only two factors in our cohort that are independently associated with preoperative seizures are temporal lobe location and RTK II methylation subclass.

It seems plausible that both the transmission of epileptic potential along anatomic structures, that rely on tumor location, as well as the biological features imprinted by epigenetic modules are most likely responsible for the development and maintenance of glioma-associated epilepsy.

Due to conflicting results regarding whether to initiate AED prophylaxis in brain tumor patients42–44 and the potential side effects and interaction with chemotherapy,45 it is currently not advised to begin AED without a seizure history in the updated SNO and EANO guideline.3–5 Nevertheless, seizure freedom is one of the main goals in the treatment of patients with a brain tumor, given the adverse effects of seizures on quality of life.46 It is thus necessary to stratify glioblastoma patients into high- and low-risk groups to prescribe AED to those, who will most likely develop a seizure. Our study provides strong evidence that the RTKII methylation subclass is mainly associated with glioma-associated seizures. Furthermore, it appears that the RTK II is the most important factor for the occurrence of a seizure during the clinical course of the disease and that 70% RTK II glioblastoma patients will experience a failure of their AED treatment.

In conclusion, our study provides the basis for methylation-based stratification of glioblastoma patients into high- and low-risk groups for seizures. Patients with a RTKII glioblastoma are of high risk for the development of a seizure and might therefore benefit from AED treatment after diagnosis, which should be addressed in future clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katharina Kolbe, Svenja Zapf, Sarina Heinemann and Jessica Stanik for technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Franz L Ricklefs, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Richard Drexler, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Kathrin Wollmann, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Alicia Eckhardt, Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Research Institute Children’s Cancer Center Hamburg, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Department of Radiation Hematology and Oncology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Dieter H Heiland, Department of Neurosurgery, Medical Center University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany (D.H.H.).

Thomas Sauvigny, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Cecile Maire, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Katrin Lamszus, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Manfred Westphal, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Ulrich Schüller, Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Research Institute Children’s Cancer Center Hamburg, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Lasse Dührsen, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from Illumina to F.L.R. U.S. was supported by the Fördergemeinschaft Kinderkrebszentrum Hamburg, A.E. is thankful for the support within the interdisciplinary graduate school “Innovative Technologies in Cancer Diagnostics and Therapy” funded by the city of Hamburg.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Authorship statement. F.L.R., R.D., and U.S. for acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data. F.L.R., R.D., and L.D. for statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript. K.W., A.E., and D.H.H. for technical and material support. D.H.H. performed TCGA integrative DNA methylation and RNA expression analysis, F.L.R., C.M., K.L. performed qPCR analysis. F.L.R., M.W., U.S., and L.D. for study concept and design, obtainment of funding and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Bauchet L, Mathieu-Daude H, Fabbro-Peray P, et al. Oncological patterns of care and outcome for 952 patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma in 2004. Neuro-Oncol. 2010;12(7):725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wychowski T, Wang H, Buniak L, Henry JC, Mohile N. Considerations in prophylaxis for tumor-associated epilepsy: prevention of status epilepticus and tolerability of newer generation AEDs. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(11):2365–2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walbert T, Harrison RA, Schiff D, et al. SNO and EANO practice guideline update: Anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Neuro-Oncol. 2021;23(11):1835–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wali AR, Rennert RC, Wang SG, Chen CC. Prophylactic anticonvulsants in patients with primary glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2017;135(2):229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Happold C, Gorlia T, Chinot O, et al. Does valproic acid or levetiracetam improve survival in glioblastoma? A pooled analysis of prospective clinical Trials in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(7):731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klein M, Engelberts NHJ, van der Ploeg HM, et al. Epilepsy in low-grade gliomas: the impact on cognitive function and quality of life: epilepsy in low-grade glioma. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(4):514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 2018;555(7697):469–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dejaegher J, Solie L, Hunin Z, et al. DNA methylation based glioblastoma subclassification is related to tumoral T-cell infiltration and patient survival. Neuro-Oncol. 2021;23(2):240–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(4):425–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang LB, Karpova A, Gritsenko MA, et al. Proteogenomic and metabolomic characterization of human glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(4):509–528.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller-Delaney SFC, Das S, Sano T, et al. Differential DNA methylation patterns define status epilepticus and epileptic tolerance. J Neurosci. 2012;32(5):1577–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Machnes ZM, Huang TCT, Chang PKY, et al. DNA methylation mediates persistent epileptiform activity in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vasudevaraja V, Rodriguez JH, Pelorosso C, et al. Somatic focal copy number gains of noncoding regions of receptor tyrosine kinase genes in treatment-resistant epilepsy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80(2):160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi BD, Lee DK, Yang JC, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase gene amplification is predictive of intraoperative seizures during glioma resection with functional mapping. J Neurosurg. 2020;132(4):1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro-Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58(4):512–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Capper D, Stichel D, Sahm F, et al. Practical implementation of DNA methylation and copy-number-based CNS tumor diagnostics: the Heidelberg experience. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2018;136(2):181–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schneider M, Vollmer L, Potthoff AL, et al. Meclofenamate causes loss of cellular tethering and decoupling of functional networks in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. 2021;23(11):1885–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huberfeld G, Vecht CJ. Seizures and gliomas—towards a single therapeutic approach. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(4):204–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dührsen L, Sauvigny T, Ricklefs FL, et al. Seizures as presenting symptom in patients with glioblastoma. Epilepsia. 2019;60(1):149–154. doi: 10.1111/epi.14615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takano T, Lin JH, Arcuino G, et al. Glutamate release promotes growth of malignant gliomas. Nat Med. 2001;7(9):1010–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lyons SA, Chung WJ, Weaver AK, Ogunrinu T, Sontheimer H. Autocrine glutamate signaling promotes glioma cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9463–9471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishiuchi S, Yoshida Y, Sugawara K, et al. Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors regulate growth of human glioblastoma via Akt activation. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2007;27(30):7987–8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buckingham SC, Campbell SL, Haas BR, et al. Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1269–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yuen TI, Morokoff AP, Bjorksten A, et al. Glutamate is associated with a higher risk of seizures in patients with gliomas. Neurology 2012;79(9):883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marcus HJ, Carpenter KLH, Price SJ, Hutchinson PJ. In vivo assessment of high-grade glioma biochemistry using microdialysis: a study of energy-related molecules, growth factors and cytokines. J Neurooncol. 2010;97(1):11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roslin M, Henriksson R, Bergström P, Ungerstedt U, Bergenheim AT. Baseline levels of glucose metabolites, glutamate and glycerol in malignant glioma assessed by stereotactic microdialysis. J Neurooncol. 2003;61(2):151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Groot J, Sontheimer H. Glutamate and the biology of gliomas. Glia 2011;59(8):1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ye ZC, Rothstein JD, Sontheimer H. Compromised glutamate transport in human glioma cells: reduction-mislocalization of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters and enhanced activity of cystine-glutamate exchange. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1999;19(24):10767–10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lange F, Hörnschemeyer J, Kirschstein T. Glutamatergic Mechanisms in Glioblastoma and Tumor-Associated Epilepsy. Cells 2021;10(5):1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 2013;155(2):462–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang P, You G, Zhang W, et al. Correlation of preoperative seizures with clinicopathological factors and prognosis in anaplastic gliomas: a report of 198 patients from China. Seizure 2014;23(10):844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fredriksson L, Stevenson TK, Su EJ, et al. Identification of a neurovascular signaling pathway regulating seizures in mice. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2(7):722–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee JW, Wen PY, Hurwitz S, et al. Morphological characteristics of brain tumors causing seizures. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(3):336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gallia GL, Rand V, Siu IM, et al. PIK3CA gene mutations in pediatric and adult glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4(10):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tanaka S, Batchelor TT, Iafrate AJ, et al. PIK3CA activating mutations are associated with more disseminated disease at presentation and earlier recurrence in glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roy A, Han VZ, Bard AM, et al. Non-synaptic cell-autonomous mechanisms underlie neuronal hyperactivity in a genetic model of PIK3CA-Driven intractable epilepsy. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:772847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park AK, Kim P, Ballester LY, Esquenazi Y, Zhao Z. Subtype-specific signaling pathways and genomic aberrations associated with prognosis of glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. 2019;21(1):59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Venkataramani V, Tanev DI, Strahle C, et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature 2019;573(7775):532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Venkatesh HS, Morishita W, Geraghty AC, et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature 2019;573(7775):539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sirven JI, Wingerchuk DM, Drazkowski JF, Lyons MK, Zimmerman RS. Seizure prophylaxis in patients with brain tumors: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(12):1489–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Glantz MJ, Cole BF, Friedberg MH, et al. A randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex sodium prophylaxis in adults with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Neurology 1996;46(4):985–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Forsyth PA, Weaver S, Fulton D, et al. Prophylactic Anticonvulsants in Patients with Brain Tumour. Can J Neurol Sci J Can Sci Neurol. 2003;30(2):106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cramer JA, Mintzer S, Wheless J, Mattson RH. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs: a brief overview of important issues. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(6):885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Englot DJ, Chang EF, Vecht CJ. Epilepsy and brain tumors. Handb Clin Neurol 2016;134:267–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw methylation IDAT files and patients data are available via gene expression omnibus (GEO) indexed as GSE188547.