Abstract

Purpose

Maintaining or increasing user adherence to digital healthcare services is of great concern to service providers. This study aims to verify whether the donation model is an effective strategy to increase adherence to physical exercise using a mobile application.

Materials and Methods

A total of 5618 users of a motion-detecting mobile exercise coaching application participated in a donation or self-reward exercise challenge with the same exercise protocol. The workout consisted of 50 squats daily for 14 days. The user’s exercise was monitored through a smartphone camera, providing real-time visual and audio feedback. In the donation group, 6 USD was donated to the economically disadvantaged if a participant completed their workout each day. In the self-reward group, three people who completed the program and 20 people who completed ≥12 days of exercise were randomly selected and provided with goods worth 60 USD and 4.3 USD of online currency, respectively.

Results

The average daily exercise completion rate (% of participants who completed daily exercise) in the donation group was 1.8 times higher than that of the self-reward group (donation, 41.7%; self-reward, 22.7%; p<0.0001). The donation group completed more days of the program (donation, 5.8; self-reward, 3.2; p<0.0001). The completion rate of both groups decreased with time and decreased most on day two (donation, -9.9%; self-reward, -14.5%).

Conclusion

The donation model effectively promoted adherence to mobile app-based exercise. This donation model is expected to effectively enhance user adherence to digital healthcare services.

Keywords: Machine learning, marketing, mobile application, motion, telehealth

INTRODUCTION

The development of smartphones and communication technology has resulted in an evolution in the public’s interest in digital healthcare. As such, both the healthcare market and medical academies are focusing increasingly on digital services.1,2 The basis of digital healthcare services related to physical exercise is the recording of a user’s movements. Bluetooth-based wearable devices using global positioning system and related applications (apps) have improved greatly over the past decade and can now automatically record movement-related data, including step counts, speed, distances, or altitudes.3,4,5,6,7 However, these developments are mainly focused on aerobic exercise. Meanwhile, the monitoring of joint motion during exercises has been limited: a large monitor and related extra Bluetooth-based devices are usually needed, and the number of joints that can be monitored is limited. Therefore, despite inaccuracy and low reporting rates, clinicians have had no choice but to rely on patient self-reporting of adherence to prescribed stretching or strengthening exercises.8,9,10

Computer-based motion analysis systems have been used in medical institutions with markers attached to a patient’s large joints since the late 1970s.11 Only recently, the detecting of joint motion through a smartphone camera without body-attachable markers has become possible with the help of artificial intelligence.12,13 Now, a machine learning-based motion-detecting mobile exercise coaching application (MDMECA) makes it possible to provide real-time feedback to users based on several algorithms and has been found to increase exercise adherence more than watching a one-way exercise guide-video.14

However, the age-old problem of digital healthcare apps ‘not being maintained continuously’ remains. Marketers have been using strategies of setting alarms or providing rewards for long-term use to increase the adherence on apps. Nevertheless, getting people to exercise consistently with simple rewards remains difficult. Therefore, this study was designed to find a way to improve user adherence to mobile app-based home exercises by comparing two different settings. One involved the user receiving the rewards for exercise themselves and the other involved donations to the socioeconomically disadvantaged. The objective amount of exercise could be monitored in real-time through an MDMECA without concerns of bias caused by user reports.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was designed as a physician-initiated retrospective case-control study conducted using an exercise dataset from a MDMECA, LikeFit app (WeHealed, Seoul, Korea), between December 2019 and April 2021. Researchers in the department of rehabilitation medicine at a tertiary hospital analyzed the transferred data obtained through the MDMECA. The transferred data was blinded, and only age and sex were included as demographic data. The study protocol was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board (IRB: 3-2021-0213) and complied with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. The IRB confirmed that written informed consent was not required because this study does not expose participant-identifiable information, but the consent to transfer users’ data to third parties was obtained from WeHealed prior to the start of the challenge. The researchers were not funded by WeHealed or from any charitable organization recruited for the donation challenges. The charitable organizations were able to get tax relief through donations.

Participants

Exercise data meeting the following conditions were screened and transferred to the researchers: 1) healthy voluntary participants participating in a single challenge, whether it was the donation or self-reward challenge, 2) participants in the same exercise protocol, and 3) the same challenge period. Consequently, a total of eight challenges (donation, 7; self-reward, 1) were screened, all of which comprised 14 days of squat exercises. A total of 78652 exercise records from 5618 users (donation, 2318; self-reward, 3300) were used during analysis. The slogans for the seven donation challenges were 1) support for food expenses for seniors living alone, 2) special meals for nursery schools, 3) support for living expenses for families of single mothers, 4) support for living expenses for low-income families with grandchildren, 5) support for psychological counseling and treatment expenses for abused children, 6) support for COVID-19-related expenses in low-income households, and 7) support for living expenses for single mothers. The slogan for the self-reward challenge was “make pretty lines.”

Intervention

Each challenge consisted of a 14-day program with the same daily exercise set, which consisted of two sets of squats (25 squats per set) with a 30-second rest interval.

Reward for exercise challenge: donation vs. self-reward

Among those participating in the donation challenge, only those who completed each day of exercise could make a proxy donation of 7000 KRW (6 USD) to the socioeconomically disadvantaged through recruited charitable organizations.

In the self-reward group, three people who completed every exercise and 20 who exercised for ≥12 days were randomly selected and provided with goods worth 70000 KRW (60 USD) and 5000 KRW (4.3 USD) in online currency, respectively.

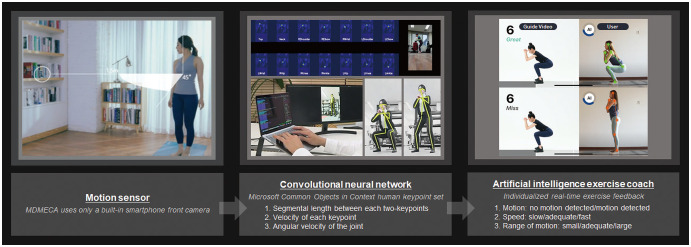

MDMECA

MDMECAs utilize deep learning technology, namely the convolutional neural network using the Microsoft Common Objects in Context (COCO) keypoint detection task (Fig. 1). A built-in smartphone camera was the only motion sensor utilized, and no supporting health-related devices were used. To participate in the challenge, the users had to run the MDMECA and enter the challenge banner on it. The users were then instructed to stand in front of a simple background while wearing clothes that clung to the body to facilitate accurate detection of movement. Thereafter, they were instructed to place their smartphones at a distance of 1–2 meters in front of them so that the front camera captured their whole body with no additional people in the camera angle. The users then proceeded with the exercises while following the prerecorded tutor’s exercise guide-video playing on the smartphone screen. The user’s motion was reflected on the screen and analyzed in real time (Supplementary Video 1, only online). The movements of the users were detected using the Microsoft COCO human keypoint set. A total of 14 keypoints were used in analyses: top of the head, neck, bilateral shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles. The following parameters were measured in real time during the exercise: 1) distance between two keypoints, 2) joint angles, 3) movement velocity of each keypoint, and 4) angular velocity of the joint.

Fig. 1. A machine learning-based motion-detecting mobile exercise coaching application (MDMECA).

During the squat challenge, the real-time feedback was classified and provided as follows, considering the angle and angular velocity of the hip and knee joints, as well as the movement velocity of the head, compared to movement of the tutor’s keypoint provided as a guide video: 1) motion (there is no motion detected/please start exercising), 2) velocity (the movement is too fast/stand up slowly/try to stand up faster/etc.), and 3) range of motion (sit more/bend your knees more/stand upright/etc.). The users could hear the real-time audio feedback simultaneously watching the visual cues on the smartphone screen (Supplementary Video 1, only online).

Exercise was encouraged in several ways. First, an encouraging push alarm was triggered in the late evening to prompt users to exercise if they had not completed their daily workout. Second, an encouraging audio message was played during the workout so that users would not stop while exercising. Third, a real-time message was displayed on-screen with a short message, such as “missed,” “good,” or “great.”

Outcomes

The exercise data of users who completed the daily workout was coded as 1, and the others as 0. The exercise data is coded as 0 regardless of whether the user ceases exercising while the app is running or while it is stopped. Therefore, the 14 days of individual exercise data comprised 14 cells containing the numbers 0 or 1.

Statistical analyses

The demographic data included the average age and sex ratio of the participants by group. The intergroup differences in the daily exercise completion rate (% of participants who completed the daily workouts) and the total exercise completion days were analyzed using an independent t-test of the coded data. The linear mixed model was used to identify intergroup differences in the degree of change in daily exercise completion rate over time. The daily exercise completion rates among those participating in the seven donation challenges and the self-reward challenge were compared through repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). SPSS version 23.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for analysis. Two-sided p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Confidence intervals of the difference between two independent proportions were calculated.

RESULTS

Flow of participants

The basic characteristics of the donation and the self-reward groups, and each subgroup in the donation group are listed in Table 1, including the target number for recruitment, actual recruited participants, days spent in recruitment, average recruiting ratio, challenge duration, average age, and sex ratio. The t-test revealed that the average age of the participants differed significantly between the groups {average (SD); donation, 36.2 (9.7); self-reward, 34.5 (10.1); mean difference (MD) [95% confidence interval (CI)], 1.7 (1.17 to 2.23)}. The sex ratio also differed between groups [donation, 1:7.3; self-reward, 1:10.9; MD (95% CI), 0.05 (0.03 to 0.06)].

Table 1. Basic Characteristics.

| Subgroups | Target recruitment | Actual recruitment | Days of recruitment | Daily recruitment (day) | Exercise period | Age (yr) | M:F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donation group | 2320 | 2318 | 36.2 (11–70) | 1:7.3 | ||||

| 1. Support for food expenses for seniors living alone | 300 | 299 | 3 | 99.7 | December, 2020 | 37.1 (11–70) | 1:7.8 | |

| 2. Support for psychological counseling and treatment expenses for abused children | 300 | 300 | 2 | 150.0 | January, 2021 | 38.0 (13–70) | 1:7.5 | |

| 3. Support for living expenses for single mother families | 500 | 499 | 6 | 83.2 | May, 2021 | 37.5 (9–70) | 1:6.6 | |

| 4. Support for living expenses for low-income families with grandchildren | 300 | 300 | 5 | 60.0 | June, 2020 | 32.9 (13–52) | 1:7.8 | |

| 5. Support for special meals at nursery schools | 320 | 320 | 6 | 53.3 | March, 2020 | 34.9 (14–50) | 1:4.8 | |

| 6. Support for low-incomes with COVID-19 | 300 | 300 | 3 | 100.0 | March, 2020 | 33.8 (13–64) | 1:9.3 | |

| 7. Support for living expenses for single mothers | 300 | 300 | 2 | 150.0 | September, 2020 | 36.7 (13–64) | 1:9.0 | |

| Self-reward group | ||||||||

| Make pretty lines | 3300 | 3300 | 15 | 220.0 | August, 2020 | 34.5 (11–70) | 1:10.9 | |

M, male; F, female; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Data are presented as n or mean (range).

Primary outcome

Daily exercise completion rate

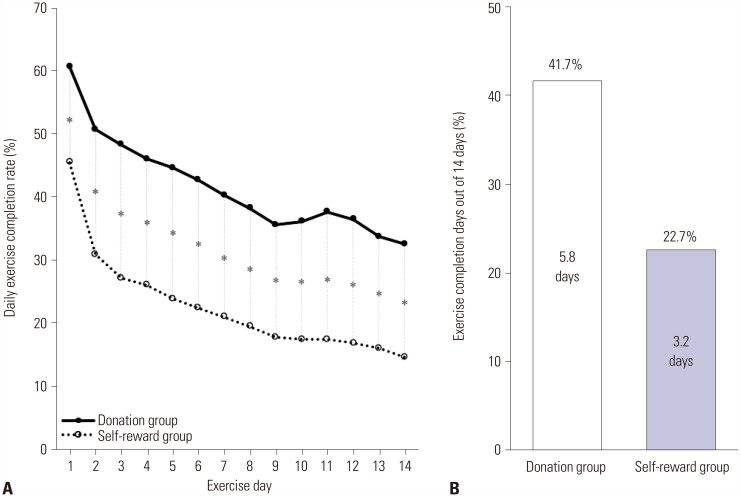

The average daily exercise completion rate of the donation group was 1.8 times higher than that of the self-reward group [donation, 41.7%; self-reward, 22.7%; MD (95% CI), 19.1% (16.6 to 21.5)] (Table 2). This rate also differed significantly between groups for each day of the program (Table 2 and Fig. 2A). The completion rate of both groups decreased with time, and the rate decreased the most on day two, compared to day one (donation, -9.9%; self-reward, -14.5%) (Fig. 2A). The linear mixed model revealed a statistically significant difference in the degree of decrease in daily exercise completion rate over time between the two groups (p<0.001).

Table 2. Intergroup Differences in Daily Exercise Completion Rates.

| Exercise day | Donation group (n=2318) | Self-reward group (n=3300) | Intergroup difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants who completed daily exercise (n) | Daily exercise completion rate (%) | No. of participants who completed daily exercise (n) | Daily exercise completion rate (%) | Δ Daily exercise completion rate (%) (95% CI) | |

| Day 1 | 1408 | 60.7 | 1503 | 45.5 | 15.2 (12.6 to 17.8) |

| Day 2 | 1177 | 50.8 | 1022 | 31.0 | 19.8 (17.2 to 22.4) |

| Day 3 | 1120 | 48.3 | 897 | 27.2 | 21.1 (18.6 to 23.7) |

| Day 4 | 1069 | 46.1 | 862 | 26.1 | 20.0 (17.5 to 22.5) |

| Day 5 | 1037 | 44.7 | 789 | 23.9 | 20.8 (18.3 to 23.3) |

| Day 6 | 990 | 42.7 | 739 | 22.4 | 20.3 (17.8 to 22.8) |

| Day 7 | 936 | 40.4 | 694 | 21.0 | 19.3 (16.9 to 21.8) |

| Day 8 | 886 | 38.2 | 644 | 19.5 | 18.7 (16.3 to 21.1) |

| Day 9 | 828 | 35.7 | 589 | 17.8 | 17.9 (15.5 to 20.2) |

| Day 10 | 836 | 36.1 | 579 | 17.5 | 18.5 (16.2 to 20.9) |

| Day 11 | 874 | 37.7 | 579 | 17.5 | 20.2 (17.8 to 22.5) |

| Day 12 | 847 | 36.5 | 557 | 16.9 | 19.7 (17.3 to 22.0) |

| Day 13 | 783 | 33.8 | 530 | 16.1 | 17.7 (15.4 to 20.0) |

| Day 14 | 755 | 32.6 | 486 | 14.7 | 17.8 (15.6 to 20.1) |

| Average | 967.6 | 41.7 | 747.9 | 22.7 | 19.1 (16.6 to 21.5) |

CI, confidence interval.

Daily exercise completion rate=No. of participants who completed daily exercise/No. of total participants for each group.

Fig. 2. Intergroup differences in the daily exercise completion rate and the average number of exercise completion days. The exercise completion rate (A) in the donation group was higher than that of the self-reward group for each exercise day. The average number of exercise completion days (B) was also 1.8 times higher in the donation group than in the self-reward group.

Secondary outcomes

Exercise completion days

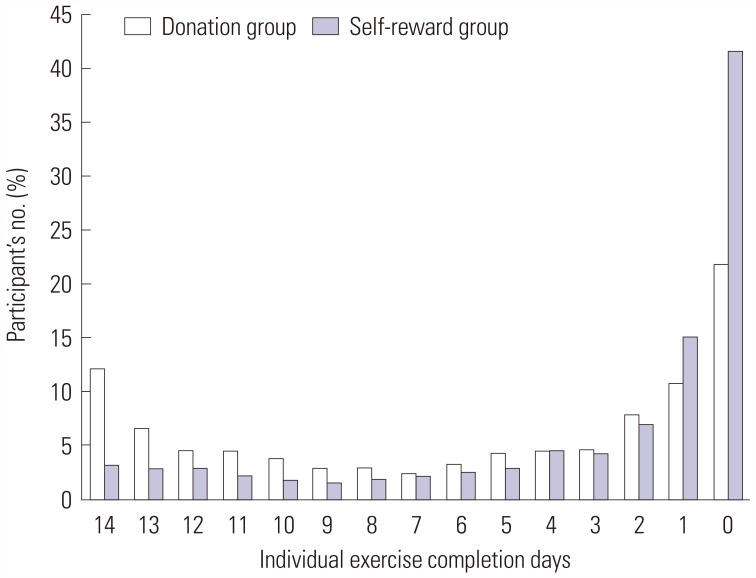

The donation group completed more days of exercise on average [mean (SD), donation, 5.8 (5.3); self-reward, 3.2 (4.3); MD (95% CI), 2.6 (2.4 to 2.9)] (Fig. 2B). The total number of participants who completed the workout on all 14 days was 286 (12.3%) in the donation group and 114 (3.5%) in the self-reward group. The proportion of those who did not exercise for even a day among the participants was 1.9 times higher in the self-reward group (41.8%) than in the donation group (22.0%). In the self-reward group, we confirmed that more than half of the participants exercised less than 3 days (64.4%) (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Table 3. Participants according to Total Exercise Days in Each Group.

| Total exercise days | Donation group (n=2318) | Self-reward group (n=3300) |

|---|---|---|

| Day 14 | 286 (12.3) | 114 (3.5) |

| Day 13 | 157 (6.8) | 101 (3.1) |

| Day 12 | 108 (4.7) | 102 (3.1) |

| Day 11 | 108 (4.7) | 79 (2.4) |

| Day 10 | 93 (4.0) | 65 (2.0) |

| Day 9 | 73 (3.1) | 61 (1.8) |

| Day 8 | 73 (3.1) | 74 (2.2) |

| Day 7 | 62 (2.7) | 80 (2.4) |

| Day 6 | 81 (3.5) | 91 (2.8) |

| Day 5 | 105 (4.5) | 101 (3.1) |

| Day 4 | 109 (4.7) | 161 (4.9) |

| Day 3 | 112 (4.8) | 146 (4.4) |

| Day 2 | 187 (8.1) | 237 (7.2) |

| Day 1 | 255 (11.0) | 510 (15.5) |

| Day 0 | 509 (22.0) | 1378 (41.8) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Fig. 3. Individual exercise completion days in two groups. The total number of participants who completed the workout on all 14 days was 286 (12.3%) in the donation group and 114 (3.5%) in the self-reward group. The proportion of those who did not exercise for even a day among the participants was 1.9 times higher in the self-reward group (41.8%) than in the donation group (22.0%). In the self-reward group, we confirmed that more than half of the participants exercised less than 3 days (64.4%).

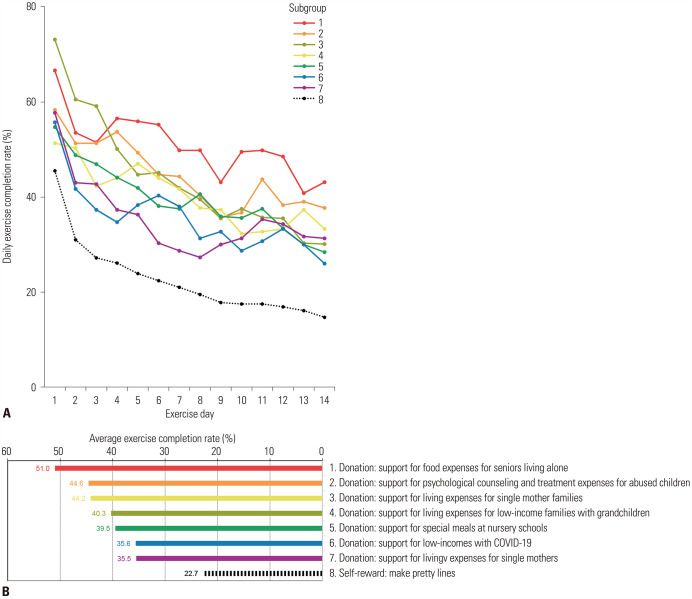

Subgroup analysis according to the challenge slogan

Subgroup analyses using repeated-measure ANOVA conducted based on the challenge slogan revealed that all subgroups in the donation challenge had significantly higher daily exercise completion rates than all subgroups in the self-reward group (all subgroups, p<0.001) (Fig. 4A). The average exercise completion rate ranged from 35.5%–51.0% in each subgroup in the donation challenge (Fig. 4B) and was highest in subgroup #1, with which the slogan was “support for food expenses for seniors living alone.”

Fig. 4. Subgroup analysis of exercise completion rates. In subgroup analyses conducted according to the challenge slogan, all subgroups participating in the donation challenge showed significantly higher daily exercise completion rates than those in the self-reward group (A). The average exercise completion rates according to the challenge slogan are visualized in ascending order (B).

DISCUSSION

One strength of this study is that we elucidated the effects of marketing strategies to promote exercise through a machine learning-based digital healthcare app and demonstrate the applicability of the donation model in facilitating an increase in exercise adherence in the mobile healthcare market. The fact that the average daily exercise completion rate was higher in the donation group for each challenge day indicated that the donation model would be more effective in maintaining the exercise adherence than the self-reward model. In addition, the fact that the proportion of those who did not exercise for even a day was lower in the donation group suggested that the donation model can also motivate the initiation of exercise.

Hospital-based supervised exercise can accurately evaluate adherence to exercise and provide feedback; however, not all patients need to exercise at a hospital.15,16,17,18 People with low intrinsic motivation often pay for a gym-based supervised activity to initiate or continue physical exercise. However, some people want to exercise alone or cannot afford the high costs for personal coaching.18 A randomized trial revealed that home-based exercise with telephone support is more cost-effective than gym-based exercise.19 However, visual or tactile feedback on movement is still difficult simply through tele-monitoring. In this context, MDMECAs are expected to address the needs of these users to some extent.

In the healthcare market, financial incentive has already been proven to effectively increase user activity levels.20,21,22,23 However, studies on the long-term effectiveness of financial incentives are lacking.21,24 This is mainly due to the economic burden placed on the service providers, and small financial incentives for physical activities that are sustainable for 12 months have been presented as a substitute.22 The effectiveness of the donation model over the financial incentive model was also studied prospectively in some previous studies.22,23 However, the main outcome of these studies was the number of visits to the institution rather than exact exercise amount. In another previous study comparing the financial incentive and charity models while tracking the amount of activity using a wearable device, the charity model more effectively increased the level of physical activity.24 In addition, the high cash self-reward model was far more effective in maintaining the activity level and usage rate of a digital tracker than the charity model during a 6-month incentive period. However, interestingly, activity levels in the cash incentive group dramatically decreased after the incentive period ended. Meanwhile, regarding these incentive exercise models, an argument has been raised that the financial incentive itself may undermine the basic value of physical activity.25 Indeed, such financial incentive models are difficult to apply in the clinical field since long-term funding is limited. On the other hand, applying the charity model consistently in the healthcare market may be easier because a social system allowing participating companies to receive tax benefits from providing financial resources is already in place.24

The parameters of the activities detected through mobile healthcare apps have primarily focused on aerobic exercise to date. Although the tracking of a user’s posture has become partially possible through a smartwatch, checking the precise movements of the extremities remains difficult.26,27 The advent of MDMECAs heralded a new era in terms of quantifying joint movements. Real-time feedback can be provided through several algorithms based on the detected joint motion and may help participants to keep exercising. According to a 10-year review of smartphone-based intervention between 2008 and 2018, researchers had to rely on subjective records through surveys or interviews for data that cannot be obtained with preexisting apps.28 Therefore, it was difficult to conduct large-scale studies due to the low response rate of participants, so much so that the largest sample size to date was about 800.20,28 However, conducting a large-scale study on the physical activities dealing with joint motion-related parameters is now possible through this MDMECA, even retrospectively, because it utilizes the accumulated objective exercise performance data of users through convolutional neural network technology.

This study has several limitations. Due to limitations of a retrospective study, we could not assess the amount of exercise that people who did not use the app might have done in a different way. The short challenge period made it difficult to verify whether the donation model effectively contributed to the formation of exercise habits. In addition, due to the limitations of a retrospective study that uses transferred institutional data, equalizing the size of rewards of the self-reward and the donation group was not possible. The amount of reward had to be planned within the budget of app developers and charitable organizations considering the expected number of participants. It can be easily expected that the adherence of each group may vary depending on the level of reward. However, this kind of study has a limitation in that results may be biased if participants know the purpose of study before participating in the challenge. Rather, if the outcomes of the challenge programs for various budgets and participant sizes accumulate, a more sophisticated retrospective analysis on the appropriate reward level will be possible in the future. The two groups of challenges were not conducted with the same number of participants or during the same period, which was an additional limitation. Limitations in newly developed digital healthcare models have always existed in that they promote or increase digital inequity.29 However, if the donation model is applied, a virtuous cycle can be created that may make up for these fundamental limitations.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the amount of home-based physical activity and the use of digital devices. Digital healthcare apps increasingly allow the real-time monitoring of various parameters during physical activity, and developing a marketing strategy that maintains or increases the usage rate of users is necessary. The donation model may be an effective marketing strategy with which to enhance user adherence to digital healthcare app-based physical activity while improving overall health in a modern society.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Jinyoung Park and Jung Hyun Park.

- Data curation: Jinyoung Park and Myungsang Kim.

- Formal analysis: Jinyoung Park.

- Investigation: all authors.

- Methodology: Jinyoung Park and Jung Hyun Park.

- Project administration: all authors.

- Resources: Jinyoung Park.

- Software: Jinyoung Park.

- Supervision: Jung Hyun Park.

- Validation: Jung Hyun Park.

- Visualization: Jinyoung Park.

- Writing—original draft: Jinyoung Park.

- Writing—review & editing: Jinyoung Park and Jung Hyun Park.

- Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Motion-detecting mobile exercise coaching application. The user is instructed to wear tight-fitting clothes and stand in front of a simple background. The guidance video for squats is shown before the workout starts. The user then stands with their lateral side facing the screen and ensures that their whole body is on the smartphone screen. Then, 14 human key points are immediately detected and traced. A real-time feedback message is prompted via audio and video using real-time monitoring. For example, when the user makes an exact exercise motion that suits the expected range of motion and speed, both visual and audio applause is provided in real-time. When the user squats slower or faster than the guide video, a visual alarm signals a “miss,” and audio feedback prompts the user to “exercise at the same speed as in the guide video.” When the user leaves the screen, an audio alarm warns users not to go off-screen.

References

- 1.Sheikh A, Anderson M, Albala S, Casadei B, Franklin BD, Richards M, et al. Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3:e383–e396. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S, Kim JA, Lee JY. International trend of non-contact healthcare and related changes due to COVID-19 pandemic. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63 Suppl:S22–S33. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2022.63.S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummins C, Orr R, O’Connor H, West C. Global positioning systems (GPS) and microtechnology sensors in team sports: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2013;43:1025–1042. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duncan MJ, Wunderlich K, Zhao Y, Faulkner G. Walk this way: validity evidence of iphone health application step count in laboratory and free-living conditions. J Sports Sci. 2018;36:1695–1704. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1409855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King AC, Hekler EB, Grieco LA, Winter SJ, Sheats JL, Buman MP, et al. Effects of three motivationally targeted mobile device applications on initial physical activity and sedentary behavior change in midlife and older adults: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liew SJ, Gorny AW, Tan CS, Müller-Riemenschneider F. A mobile health team challenge to promote stepping and stair climbing activities: exploratory feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e12665. doi: 10.2196/12665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park Y, Go TH, Hong SH, Kim SH, Han JH, Kang Y, et al. Digital biomarkers in living labs for vulnerable and susceptible individuals: an integrative literature review. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63 Suppl:S43–S55. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2022.63.S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Huerta BD, Díaz-Pulido B, Pecos-Martin D, Beckwee D, Lluch-Girbes E, Fernandez-Matias R, et al. Effectiveness of a program combining strengthening, stretching, and aerobic training exercises in a standing versus a sitting position in overweight subjects with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2020;9:4113. doi: 10.3390/jcm9124113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azevedo DC, Ferreira PH, de Oliveira Santos H, Oliveira DR, Leite de Souza JV, Pena Costa LO. Association between patient independence in performing an exercise program and adherence to home exercise program in people with chronic low back pain. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;51:102285. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourke L, Homer KE, Thaha MA, Steed L, Rosario DJ, Robb KA, et al. Interventions for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD010192. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010192.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutherland DH. The evolution of clinical gait analysis. Part II kinematics. Gait Posture. 2002;16:159–179. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(02)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zago M, Luzzago M, Marangoni T, De Cecco M, Tarabini M, Galli M. 3D tracking of human motion using visual skeletonization and stereoscopic vision. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:181. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JS, Kim YW, Woo YK, Park KN. Validity of an artificial intelligence-assisted motion-analysis system using a smartphone for evaluating weight-bearing activities in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Musculoskelet Sci Technol. 2021;5:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J, Chung SY, Park JH. Real-time exercise feedback through a convolutional neural network: a machine learning-based motion-detecting mobile exercise coaching application. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63 Suppl:S34–S42. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2022.63.S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srivastava P. Drug metabolism and individualized medicine. Curr Drug Metab. 2003;4:33–44. doi: 10.2174/1389200033336829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liaghat B, Ussing A, Petersen BH, Andersen HK, Barfod KW, Jensen MB, et al. Supervised training compared with no training or self-training in patients with subacromial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:2428–2441.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latham NK, Harris BA, Bean JF, Heeren T, Goodyear C, Zawacki S, et al. Effect of a home-based exercise program on functional recovery following rehabilitation after hip fracture: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:700–708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freene N, Waddington G, Chesworth W, Davey R, Cochrane T. Community group exercise versus physiotherapist-led home-based physical activity program: barriers, enablers and preferences in middle-aged adults. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014;30:85–93. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.816894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansons P, Robins L, O’Brien L, Haines T. Gym-based exercise was more costly compared with home-based exercise with telephone support when used as maintenance programs for adults with chronic health conditions: cost-effectiveness analysis of a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2018;64:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein EA, Sahasranaman A, John G, Haaland BA, Bilger M, Sloan RA, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of participants in the TRial of Economic Incentives to Promote Physical Activity (TRIPPA): a randomized controlled trial of a six month pedometer program with financial incentives. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;41:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DM, Lee HH, Connell L, Boyle H, Emerson J, Strohacker K, et al. Small sustainable monetary incentives versus charitable donations to promote exercise: rationale, design, and baseline data from a randomized pilot study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;66:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galárraga O, Bohlen LC, Dunsiger SI, Lee HH, Emerson JA, Boyle HK, et al. Small sustainable monetary donation-based incentives to promote physical activity: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2020;39:265–268. doi: 10.1037/hea0000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkelstein EA, Haaland BA, Bilger M, Sahasranaman A, Sloan RA, Nang EEK, et al. Effectiveness of activity trackers with and without incentives to increase physical activity (TRIPPA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:983–995. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirgios EL, Chang EH, Levine EE, Milkman KL, Kessler JB. Forgoing earned incentives to signal pure motives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:16891–16897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000065117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortazavi B, Nemati E, VanderWall K, Flores-Rodriguez HG, Cai JY, Lucier J, et al. Can smartwatches replace smartphones for posture tracking? Sensors (Basel) 2015;15:26783–26800. doi: 10.3390/s151026783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceron JD, Lopez DM. Towards a personal health record system for the assesment and monitoring of sedentary behavior in indoor locations. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;228:804–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domin A, Spruijt-Metz D, Theisen D, Ouzzahra Y, Vögele C. Smartphone-based interventions for physical activity promotion: scoping review of the evidence over the last 10 years. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e24308. doi: 10.2196/24308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watts G. COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:e395–e396. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Motion-detecting mobile exercise coaching application. The user is instructed to wear tight-fitting clothes and stand in front of a simple background. The guidance video for squats is shown before the workout starts. The user then stands with their lateral side facing the screen and ensures that their whole body is on the smartphone screen. Then, 14 human key points are immediately detected and traced. A real-time feedback message is prompted via audio and video using real-time monitoring. For example, when the user makes an exact exercise motion that suits the expected range of motion and speed, both visual and audio applause is provided in real-time. When the user squats slower or faster than the guide video, a visual alarm signals a “miss,” and audio feedback prompts the user to “exercise at the same speed as in the guide video.” When the user leaves the screen, an audio alarm warns users not to go off-screen.