Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic brought many challenges to the health care workforce. A novel infectious disease, COVID-19 uncovered information gaps that were essential for frontline staff, including nurses, to care for patients and themselves. The authors developed a Web-based solution consisting of saved searches from PubMed on clinically relevant topics specific to nurses’ information needs. This article discusses the objectives, development, content, and usage of this Internet resource and also provides tips for hospitals of all sizes to implement similar tools to evidence-based practice during infectious disease outbreaks.

Keywords: Information needs, Information seeking behavior, Nursing, Infodemic, Information overload, COVID-19

Key points

-

•

Identify a single point of access to reduce information seeking barriers (time, searching skills, resource awareness).

-

•

Creating saved search strings tailored to nursing interests enables efficient access to relevant information.

-

•

Monitor the literature and revise search strings accordingly.

-

•

Use a team-based approach to reduce workload, burden, and increase scalability.

Introduction

Infectious disease outbreaks or epidemics can appear very suddenly and with little to no notice. Whether the etiological organism is novel or familiar, these abrupt public health events can immediately overwhelm the local or national health care infrastructure and the health care workforce. Nurses’ roles as frontline staff are particularly prone to anxiety and burnout due to clinical uncertainty and the feeling of being unprepared, powerless, and frightened for their health and families.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Studies from previous global infectious disease outbreaks, epidemics, or pandemics (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]/AIDS, influenza, Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], Middle East respiratory syndrome [MERS]) and the current COVID-19 pandemic illustrate the importance of timely delivery of information pertaining to protocols, guidelines, precautionary measures, identifying and avoiding risks, and overall safety.1 , 4 , 7, 8, 9, 10 This information is traditionally derived from trusted sources such as federal agencies, Ministries of Health, and the World Health Organization.9 , 11 The timing, content, and mechanisms of disseminating outbreak-related information are empowering; instill a sense of control and confidence; improve the ability to cope; and reduce psychological distress, anxiety, fear, confusion, error, and spreading of misinformation.7 , 12

Since January 2020, the world has been saturated with information related to the novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome-COV-2, SARS-COV-2, or the more popular term, COVID-19. Information is disseminated from local, state, national, and international health authorities, governments, print and visual media news outlets, businesses, organizations, educational institutions, and countless social media platforms. Nurses were experiencing information overload long before the COVID-19 pandemic13 , 14 but current information and communication technologies increased the amount of available information exponentially and with less effort.15 Evidence derived from biomedical research and clinical practice is essential for improving health care safety, quality, and efficiency. When the pandemic began, evidence was badly needed. However, the information or evidence ecosystem was perceived as being in constant disarray during the pandemic.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

The issues surrounding nursing and evidence-based practice have been investigated, discussed, and are well documented.23 As previously stated, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated those issues due to the amount of information generated and the constant changing of preventative measures and treatment guidance disseminated to health care providers. However, it is interesting to note that only a small percentage of preventative and treatment guidance can be considered research evidence and an even smaller amount applied to the varied information needs of nurses. A broad Medline (via PubMed) search (performed June 30, 2022) on COVID-19 yields 272,667 results. However, as shown in Table 1 , less than 0.07% of the COVID-19 literature in the Medline database was research evidence. The nursing-specific literature base was even more sparse and remains so today. When the pandemic began, nurses needed the best available evidence quickly and in a format that was consumable.

Table 1.

Medline (PubMed) evidence-based practice search results

| Limits (January 1, 2020–June 30, 2022) | Number of Results (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | None | 272,667 |

| COVID-19 | Evidence publication typesa | 18,336 (0.07) |

| COVID-19 AND nursea | None | 16,606 (0.06) |

| COVID-19 AND nursea | Evidence publication typesa | 1275 (0.005) |

NOTE: PubMed EBM search filters: clinical trial, comparative study, controlled clinical trial, guidelines, meta-analysis, multicenter study, observational study, practice guidelines, randomized clinical trial, systematic review.

To combat the known barriers to evidence-based practice, the investigators discussed the need for a technological solution to provide nurses with efficient access to the biomedical literature, particularly to topics that may not be addressed in standard governmental, organizational, or association communications. This article discusses the development of a Web-based platform composed of saved search strings in the Medline database (PubMed) and other vetted information resources pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

Similar to many hospitals and health systems, our academic medical center created a COVID-19 Command Center in March, 2020. Initially, the command center focused on planning for the nursing care needs for the influx of patients seeking COVID-19 testing or treatment. Operational and research colleagues modeled various scenarios based on trends of COVID-19 spread in other countries and its arrival in the United States; nursing operations projected staffing needs based on this modeling. Nursing stakeholders and the local health department planned alternate locations for patients should existing acute care beds be full. We organized COVID-19 testing locations to minimize exposure and risk. We created contingency plans for staffing that included mobilizing additional clinical nurses who were currently working in nonclinical roles. We monitored supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) and updated PPE use policies. Visitor policies were modified. Student clinical rotations moved from onsite to simulated experiences. Telehealth services expanded. Workers, including nurses who were not at the bedside, began working remotely. Because COVID-19 was a novel virus, little was definitively known about how best to protect against it or how best to treat it. The medical center’s office of evidence-based practice (EBP) and nursing research wanted to provide the best available evidence to nursing teams to use for decision making.

Approach

We (CI, PW) met virtually on April 3, 2020 to discuss opportunities to collate evidence-based practice resources into an interface useful for bedside nurses, nursing leaders, and nursing faculty. A prototype was developed by using the LibGuides (SpringShare, Miami, FL, USA) platform, including several of the recent searches performed by one of us (PW). After reviewing the prototype, authors agreed upon a few minor edits and finalized an initial set of search topics and Web resources that were perceived to be relevant and specific to nursing. Because of the urgency of COVID-19 information needs, the project’s user template and search topics were communicated to the biomedical library’s Information Services Team to expedite its development. The resulting Nursing EBP for COVID-19 Webpage, https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/COVID19ebp, was given top-level placement on the Eskind Biomedical Library’s homepage (Fig. 1 ). The biomedical library’s Web portal was already a well-known, respected, and highly used resource; thus, this new, central point of access did not require any additional permissions or health information technology resources. Once live, the Web portal was promoted through the previously mentioned Command Center. After the initial national lockdown period, our shared governance committees began meeting virtually, which provided additional opportunities to promote these evidence-based resources through shared governance committees, especially clinical practice committees. There were also links to the biomedical library interface included on other nursing Web sites across the enterprise.

Fig. 1.

Eskind library home page quick links.

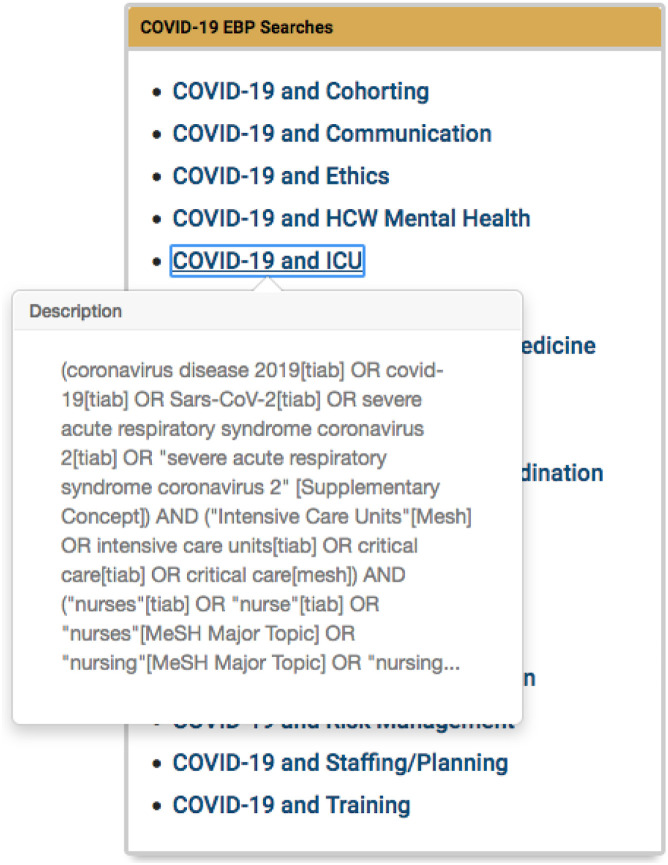

Additional topics were added from search requests by the adult academic health center’s clinical practice committee, as well as any pressing issues deemed valuable by the library team. The primary objective was to create and save search strings (Fig. 2 ) on topics specifically related to COVID-19 but its novelty resulted in a shortage of relevant literature. An opportune discovery in PubMed uncovered numerous research articles on the experience of nurses caring for patients during other infectious diseases and other pandemics, including HIV/AIDS, Ebola, Zika virus, SARS, MERS, and H1N1 influenza. Many of these articles were international studies but yielded insightful information in the absence of COVID-19 literature. Thus, all searches were duplicated but supplemented with broader search terms such as “epidemics,” “pandemics,” “infectious disease outbreaks,” and the aforementioned diseases. As the COVID-19 research literature began to increase in availability, it was vital to begin providing tips and training on how to revise, refine, and tailor searches to bring efficiencies to information seeking and knowledge translation. The Webpage for the office of EBP and Nursing Research included tips about how to refine search results and members of the Information Services Team provided individual instruction upon request on how to refine and revise the existing search strings.

Fig. 2.

Covid-19 EBP pubMed search example.

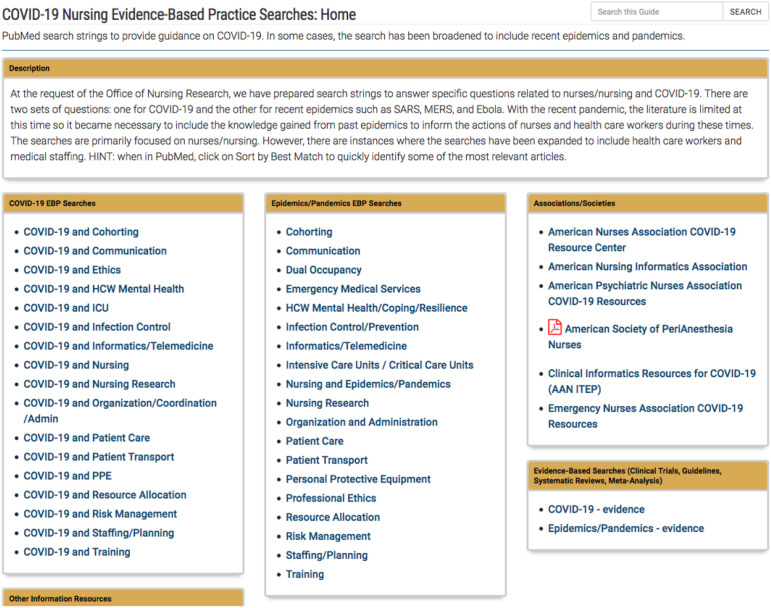

Final content and usage analysis

The final Nursing EBP for COVID-19 Webpage consists of 38 saved searches (17 COVID-19, 19 Epidemics/Pandemics, 2 EBP search strings; limited to clinical trials, guidelines, systematic reviews, meta-analyses) and 18 curated links to vetted resources from professional associations, library vendors, US governmental agencies, and international bodies. The full list of search topics is listed in Fig. 3 . The Webpage had a total of 3129 views from April 2020 to June 2022, averaging 116 views each month. The highest use period was April 2020 to March 2021, with more than 100 Webpage views each month. The range of monthly views during that high use period was 105 to 356. Usage has remained constant but reduced since October 2021.

Fig. 3.

Covid-19 EBP pubMed search topics.

The most searched topics (from highest to lowest) are Nursing, Infection Control, Nursing Research, Patient Care, and Personal Protective Equipment (Table 2 ). These topics coincide with what has been presented in previous epidemic/pandemic related literature. From an informatics and administrative perspective, if research suggests these topics are highly valued by nurses, then further investigation is warranted, in order to be more proactive with dissemination of this type of clinical information and the generation of new knowledge, in order to be prepared for the next infectious disease outbreak.

Table 2.

Most popular PubMed search topics

| Most Used Links (March 2020–June 2022) | |

|---|---|

| Topic | Total |

| COVID-19 and Nursing | 347 |

| COVID-19 and Infection Control | 299 |

| COVID-19 and Nursing Research | 215 |

| COVID-19 and Patient Care | 188 |

| COVID-19 and PPE | 138 |

| COVID-19 and ICU | 114 |

| COVID-19 and Patient Cohorting | 100 |

| COVID-19 and Health Care Worker Mental Health | 88 |

| COVID-19 Evidence-Based Search Filters | 77 |

| COVID-19 and Communication | 74 |

| COVID-19 and Staffing/Planning | 74 |

Discussion

- Here is a summary of what worked well with the technology solution:

-

a.Creating a single point of access to reduce information seeking barriers (time, searching skills, resource awareness).

-

b.Saving search strings tailored to nursing interests enabled efficient access to relevant information.

-

c.Monitoring the literature and revising search strings accordingly kept resources current.

-

d.Using a team-based approach reduced workload, burden, and increased scalability.

-

e.Long-standing relationships and established trust with the library and information specialists proved to be beneficial.

-

a.

- There were lessons learned along the way:

-

f.We did not place Help or Contact Us links on the Webpage and thus wonder how many information needs went unmet because of that omission. Although our focus was on technology and information access; we acknowledge that basic human-to-human interaction is helpful.

-

g.Future iterations should identify and use a platform that incorporates technologies that allow push notifications or other automated dissemination of new search results.

-

h.We might have considered identifying key nursing journals to include on the Webpage.

-

i.We were heavily dependent on PubMed (Medline) because of its accessibility and familiarity but are aware it was not all inclusive.

-

f.

Although we successfully formatted a Webpage for easy access to resources to guide EBP, we identified the need to increase the competency of our teams to evaluate and summarize the resources in order to make decisions based on an entire body of available evidence, rather than to rely on a single article or study. We also identified examples of decisions made without an evidence search. Some of the variabilities may be explained by chaos related to a worldwide pandemic but the variability highlighted the need to expand the culture of EBP at our institution. In early 2022, more than 20 health system nurse leaders completed a 40-hour EBP Immersion Workshop.24 The workshop experience included practice with literature searches and tools to rapidly appraise and summarize relevant literature, as well as tools to synthesize the literature in such a way that recommendations may be visualized. Nurse leaders who attended the workshop are currently working with their individual teams to expand EBP competency and capacity.

We acknowledge the resources afforded to an academic medical center may not be available in other settings. Infectious microorganisms do not care if you have a library or library access. The need for efficient access to credible and translatable information is necessary for all health care workers, their families, and the public at large. Organizations without their own library can still replicate our actions with a small, dedicated team (formal or informal) of evidence-based champions or knowledge brokers.25 Champions can perform an environmental scan on free or low-cost Web-based tools and seek approval within their organization. Although many organizations are familiar with intranets, they consider experimenting with social media platforms such as blogs26 or wikis.27 Information and guidance during infectious disease outbreaks are in a state of constant flux. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that future pandemics would require health care personnel to participate in a living evidence ecosystem supported by integrated Internet and communication technologies that provide the right information at the right time to the right people.

Summary

The speed of research and publishing brought many challenges to evidence-based practice and nursing care but none more paramount than the questions regarding the utility and futility of the traditional evidence-based paradigm during the pandemic. Information overload in health care is not a novel concept. However, the COVID-19 pandemic provides health care practitioners and information professionals an opportunity to revisit existing information management policies, strategies, architecture, and technologies to reduce the noise and deliver pertinent information in a systematic way that is effective, actionable, and tailored to its recipient. As we begin to prepare for the next pandemic, it will be crucial that we increase our competencies in accessing, rapidly appraising, and summarizing the evidence to make evidence-based decisions. Clinical nurses and nurse leaders must also start incorporating models and principles from the Information Sciences, Health Informatics, Communication Sciences, Health/Science Communication, and Information Ecology to effectively address the information needs of the health care workforce while staying empathetic to the demands of their workload and well-being.

Our project was a team-based initiative to reduce information seeking barriers by connecting nurses to strategically identified topics that were specifically related to the nursing context. By reducing obstacles such as time, resource awareness, searching skills, and other logistics we can instill confidence and comfort in knowing the workforce is applying the best possible care through informed decision-making and clinical decision support.4 , 28 , 29 The Nursing EBP for COVID-19 Webpage is a centrally located, well promoted, Web-based information resource that is user-friendly, independent of operating systems, and compatible with mobile or desktop devices. The development and constant revisioning of aggregated and vetted information from professional societies and associations and state and federal health authorities still left many information gaps for nurses and other health care practitioners. It was important to acknowledge the value of contextual primary research literature and identify methods to efficiently access it. Creating and saving search strings on the PubMed platform allows all health care organizations the ability to find primary literature within the Medline database. Furthermore, this approach connected users to thousands of freely available full-text articles related to COVID-19 in PubMed and PubMed Central that served as a viable supplement to the aggregated information from the State Department of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Health care environments are dynamic and constantly changing, facts that are magnified when stressed by a global pandemic. As the largest segment of the health care workforce, the information needs of nurses must be supported so that nurses can consistently provide evidence-based care for their patients and maintain their own well-being.

Clinics care points

-

•

Nurses are hungry for information needed to take care of their patients and themselves.

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the need for evidence-based information, but information consumers must be competent to appraise and summarize the information.

-

•

Evidence-based resources can be made available to health care workers without access to formal libraries.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Health Sciences Informationists at the Eskind Biomedical Library, Camille Ivey; Heather Laferriere; and Rachel Walden, for their hard work and diligence with the search strings and their continued efforts with supporting the evidence-based practice culture of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, United States.

References

- 1.Chung B.P., Wong T.K., Suen E.S., et al. SARS: caring for patients in Hong Kong. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(4):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebreselassie A.F., Bekele A., Tatere H.Y., et al. Assessing the knowledge, attitude and perception on workplace readiness regarding COVID-19 among health care providers in Ethiopia-An internet-based survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.González-Gil M.T., González-Blázquez C., Parro-Moreno A.I., et al. Nurses' perceptions and demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;62:102966. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam S.K.K., Kwong E.W.Y., Hung M.S.Y., et al. Nurses' preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks: A literature review and narrative synthesis of qualitative evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7–8):e1244–e1255. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norful A.A., Rosenfeld A., Schroeder K., et al. Primary drivers and psychological manifestations of stress in frontline healthcare workforce during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;69:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih F.J., Gau M.L., Kao C.C., et al. Dying and caring on the edge: Taiwan's surviving nurses' reflections on taking care of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Appl Nurs Res. 2007;20(4):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim Y. Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(7):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Monshed A.H., Amr M., Ali A.S., et al. Nurses' knowledge, concerns, perceived impact and preparedness toward COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Pract. 2021;27(6):e13017. doi: 10.1111/ijn.13017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prescott K., Baxter E., Lynch C., et al. COVID-19: how prepared are front-line healthcare workers in England? J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(2):142–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M., Zhou M., Tang F., et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(2):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olum R., Chekwech G., Wekha G., et al. Coronavirus Disease-2019: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Health Care Workers at Makerere University Teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front Public Health. 2020;8:181. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirois F.M., Owens J. Factors Associated With Psychological Distress in Health-Care Workers During an Infectious Disease Outbreak: A Rapid Systematic Review of the Evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:589545. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamric A.B. Dealing with the knowledge explosion. Clin Nurse Specialist: J Adv Nurs Pract. 2002;16(2):68–69. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGuire J.M. Putting nursing research findings into practice: research utilization as an aspect of the management of change. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(1):65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03674.x. Wiley-Blackwell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valika T.S., Maurrasse S.E., Reichert L. A Second Pandemic? Perspective on Information Overload in the COVID-19 Era. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(5):931–933. doi: 10.1177/0194599820935850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casigliani V., De Nard F., De Vita E., et al. Too much information, too little evidence: is waste in research fuelling the covid-19 infodemic? BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2020;370:m2672. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Else H. How a torrent of COVID science changed research publishing - in seven charts. Nature. 2020;553:7839. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenhalgh T. Will COVID-19 be evidence-based medicine's nemesis? PLoS Med. 2020;6:e1003266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannidis J.P.A. Coronavirus disease 2019: The harms of exaggerated information and non-evidence-based measures. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;4:e13222. doi: 10.1111/eci.13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krouse H.J. Whatever Happened to Evidence-Based Practice During COVID-19? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):318–319. doi: 10.1177/0194599820930239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makic M.B.F. Providing Evidence-Based Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Crit Care Nurse. 2020;40(5):72–74. doi: 10.4037/ccn2020908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson R., McCrae N. Will evidence-based medicine be another casualty of COVID-19? J Adv Nurs. 2020;12:3228–3230. doi: 10.1111/jan.14543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnyk B.M., Fineout-Overholt E., Gallagher-Ford L., et al. The state of evidence-based practice in US nurses: critical implications for nurse leaders and educators. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42(9):410–417. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182664e0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helene Fuld Health Trust National Institute for Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare. https://fuld.nursing.osu.edu/ Available at: Accessed June 30, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Catallo C. Should Nurses Be Knowledge Brokers? Competencies and Organizational Resources to Support the Role. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2015;28(1):24–37. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2015.24235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blog. Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary. 2022. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/blog. Accessed November 22, 2022.

- 27.Wiki. Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary. 2022. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/wiki. Accessed November 22, 2022.

- 28.Brown R.J.L., Michalowski M. Nurses' Utilization of Information Resources for Patient Care Tasks: A Survey of Critical Care Nurses in an Urban Hospital Setting. Comput Inform Nurs. 2022 doi: 10.1097/cin.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Boyle C., Robertson C., Secor-Turner M. Nurses' beliefs about public health emergencies: fear of abandonment. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(6):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]