Abstract

Infection of humans and dogs by Leishmania infantum may result in visceral leishmaniasis, which is characterized by impaired T-cell-mediated immune responses to parasite antigens. Dogs are natural hosts of Leishmania parasites and play an important role in the transmission of the parasites to humans. In an effort to characterize the immune response in dogs infected with this intracellular pathogen, we examined how infection with L. infantum affects canine macrophages and the consequences for T-cell activation in vitro. We showed that the proliferation of T-cell lines to cognate antigen decreases to background levels when infected autologous monocyte-derived macrophages are used as antigen-presenting cells (APC). The observed reduction of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation was shown to be dependent on the parasite load and to require cell-to-cell interaction of T cells with the infected APC. In addition, we observed a decreased expression of costimulatory B7 molecules on infected monocyte-derived macrophages. The expression of other surface molecules involved in T-cell activation, such as major histocompatibility complex class I and class II, on these cells did not change upon infection, whereas the expression of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 was marginally increased. Compensation for the decreased expression of B7 molecules by the addition of B7-transfected cells resulted in the restoration of cell proliferation and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by a Leishmania-specific T-cell line. These results showed that for the activation of parasite-specific canine T cells producing IFN-γ, which are most likely involved in protective immunity, sufficient expression of B7 molecules on infected macrophages is required. Provision of costimulatory molecules may be an approach for immunotherapy of leishmaniaisis as well as for vaccine development.

The intracellular protozoan parasite Leishmania infantum, transmitted by the female sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, causes visceral leishmaniasis in both humans and dogs in Mediterranean countries (1). Parasites invade and multiply within macrophages (Mφ) of the viscera, causing a fatal disease if untreated because of the failure of the host to generate a protective immune response.

In progressive disease, cellular immune responses are impaired, as indicated by studies showing that peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) from affected humans and dogs fail to respond to parasite antigens both in vitro and in vivo. Protective immunity has generally been associated with a distinct cellular immune response, manifested by a strong proliferative response of PBL to leishmanial antigens (4, 5, 28, 35) and the production of cytokines, such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor, which are required for Mφ activation and killing of intracellular parasites (17, 18, 25, 29).

Mφ play an important role in the immune response against Leishmania parasites, since they are the host cells for the parasites; they are potential antigen-presenting cells (APC) and, depending on their capacity to respond to T-cell-derived cytokines during the course of the disease, can kill intracellular pathogens. Initial studies have suggested impaired antigen presentation by infected Mφ (13). For T-cell activation by APC, engagement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) with a peptide-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) complex and interaction between costimulatory molecules are required (3). Engagement of the TCR in the absence of costimulation can lead to the induction of T-cell unresponsiveness (15). Whether L. infantum interferes with the activation of protective T cells by modulation of either of the signals required for T-cell activation in dogs remains to be studied.

Here we report on the decreased proliferation of T-cell lines to cognate antigen when canine monocyte-derived Mφ (MDM) infected with L. infantum were used as APC. Analysis of the expression of various surface molecules indicated a decreased expression of costimulatory B7 molecules on infected APC. The decreased T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production by a Leishmania-specific T-cell line could be overcome by compensating for the decreased expression of B7 molecules on infected APC by adding B7.1-transfected fibroblasts. The expression of other surface molecules involved in T-cell activation, such as MHC class I and class II, on these APC did not change upon infection, whereas the expression of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) was marginally increased. These data demonstrate an important role for B7 molecules in parasite-specific T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production and suggest down-regulation of B7 expression on infected APC as a way for this intracellular pathogen to evade the immune response of the host. The implications of these parasite-induced changes on the immune response of the host to L. infantum are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and dogs.

L. infantum (MCAN/ES/88/1SS441 DOBA) parasites were maintained as promastigotes at 25°C in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Pasley, Renfrewshire, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sera Lab, Crawley Down, Sussex, United Kingdom), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 100 IU of penicillin (Gibco) per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin (Gibco) per ml. Parasites at the stationary phase of growth were used for infection of MDM. The dogs used in this study were healthy animals housed at the animal facility of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Generation of T-cell lines.

An L. infantum-specific T-cell line was generated from the peripheral blood of a beagle dog (no. 9157) that was immunized with Leishmania soluble antigen (LSA) by a procedure described previously (27). For these experiments, at 14 days after initial stimulation, the T-cell line (106 cells/ml) was restimulated by the addition of irradiated (6,000 rads) autologous MDM (105 cells/ml) and LSA (10 μg/ml). After 72 h, the culture supernatant was harvested and IFN-γ activity was measured by a bioassay (29). Dohyvac, a combination canine vaccine (Duphar B. V., Weesp, The Netherlands) against distemper, hepatitis, and parainfluenza, routinely administered to the dogs, was also used to generate T-cell lines from dog 9158. For restimulation, Dohyvac was inactivated by UV irradiation for 20 min and subsequently boiled for 10 min. Dohyvac soluble antigen (35 μg/ml) was added to Dohyvac-specific T cells together with irradiated MDM as described above.

MDM.

Canine MDM were prepared from peripheral blood of beagle dogs as described in detail elsewhere (29). Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were plated in 9.5-cm2 wells of six-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) at 6 × 106 cells/well for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Nonadherent cells were removed, and the monolayer of adherent monocytes was washed gently with prewarmed culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml). MDM were obtained after differentiation of monocytes by maintaining the adherent cells for an additional 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Flow cytometric analysis.

The expression of various surface molecules on MDM was analyzed with monoclonal antibodies directed against canine ICAM-1 (CL18.1D8) (26) and human MHC class I (B1.1.G.6) and class II (7.5.10.1), shown to cross-react with canine MHC molecules (8); the antibodies were kindly provided by F. Koning, Academic Hospital, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Determination of the expression of various T-cell markers was carried out with monoclonal antibodies directed against canine Thy.1 (8.358), CD4 (12.125), and CD8 (1.140), (11), kind gifts from D. Gebhard, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University. Monoclonal antibodies against canine TCR α/β (CA15.8G7) and TCR γ/δ (CA20.6A3) (22, 23) were also included in this study. Incubation of 105 cells with the appropriate dilutions of the antibodies was performed for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% normal dog serum and incubated for a further 20 min at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody specific for mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). The soluble CTLA4-Ig fusion protein used to measure the expression of costimulatory B7 molecules (20) was generously provided by P. Linsley (Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Seattle, Wash.). For experiments with CTLA4-Ig, human IgG was used as a control antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody specific for human IgG (Becton Dickinson) was used as the detecting antibody. The relative fluorescence intensity was measured on a FACScan apparatus (Becton Dickinson).

Infection of MDM and proliferation of T-cell lines.

Monolayers of MDM were infected with promastigotes of L. infantum at a parasite-to-MDM ratio of 50:1 (unless indicated otherwise) for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Residual parasites were removed by gentle washing with prewarmed medium. Infected MDM were incubated for a further 24 h, gently washed with prewarmed medium, and then collected by incubation with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline–EDTA for 10 min. The final number of cells was controlled for every experiment after infection and washes. The number of intracellular parasites per MDM was determined by counting intracellular parasites in at least 100 infected cells by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained preparations.

To assay proliferative responses, T-cell lines (5 × 104/well) and irradiated (6,000 rads) autologous uninfected or infected MDM (5 × 103 cells/well) were incubated in flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (Costar) in the presence of either concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (2 μg/ml), LSA (10 μg/ml), or Dohyvac (35 μg/ml) or in the absence of antigen in a total volume of 200 μl of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Fluka AG, Buchs, Switzerland) (28). Cells were cultured for 4 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 and pulsed with [3H]thymidine during the last 18 h. Cells were harvested on glass-fiber filters, and [3H]thymidine incorporation was determined by liquid scintillation counting. All tests were performed in triplicate. Proliferative responses were expressed as mean counts per minute ± standard deviations (SD).

Human B7.1-transfected 3T6-FcγRII/B7 (3TB7) and untransfected 3T6-FcγRII (3TFII) cell lines and a monoclonal antibody directed against human B7.1 molecules (7) (kindly provided by Mark de Boer, Pan Genetics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were also used in this study. Irradiated (8,000 rads) 3TB7 or 3TFII fibroblasts (1,000 cells/well) were added to cultures of L. infantum-specific T cells and autologous uninfected or infected MDM as described above.

Transwell cultures.

To determine whether infected MDM produce soluble factors that may modulate antigen-specific T-cell proliferation, coincubation of an L. infantum-specific T-cell line in close proximity with infected MDM but without direct cell-to-cell contact was achieved by use of a dual-chamber Transwell culture system (Costar). In this system, 3 × 105 Leishmania-specific T cells were cultured with 3 × 104 irradiated (6,000 rads) uninfected MDM and 10 μg of LSA per ml or medium only in 600 μl in the lower compartment. L. infantum-infected or uninfected MDM (3 × 104 in 100 μl) were added to the upper compartment. As a control, parasite-specific T cells were incubated with infected MDM in the lower compartment and medium only in the upper compartment. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 days and pulsed with [3H]thymidine during the last 18 h. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Cells from the lower well were reseeded in a 96-well plate (Costar) and harvested on glass-fiber filters as described above.

Statistical analysis.

The data were expressed as mean counts per minute ± SD. The statistical significance (P < 0.05) of the data was evaluated by Student’s t test of paired samples.

RESULTS

Reduced proliferation of and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T-cell lines upon stimulation with L. infantum-infected MDM.

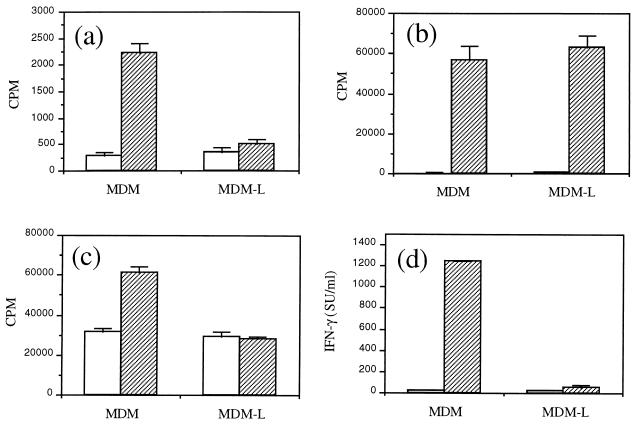

Antigen-specific T-cell lines were generated from immunized animals and restimulated in vitro with autologous MDM as APC and cognate antigen. Proliferation of the Dohyvac-specific T-cell line to cognate antigen was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) relative to background levels when L. infantum-infected MDM were used as APC relative to uninfected MDM (Fig. 1a). In contrast, polyclonal stimulation of this T-cell line after incubation with either uninfected or L. infantum-infected MDM and the mitogen ConA was not significantly different (Fig. 1b). In addition, we observed that restimulation of a Leishmania-specific T-cell line with LSA and infected MDM resulted in significantly (P < 0.05) decreased proliferation (Fig. 1c) and production of IFN-γ (Fig. 1d) relative to background levels and relative to restimulation of this T-cell line with uninfected MDM. No significant difference in the proliferation of this T-cell line in the presence of either infected or uninfected APC and ConA was observed (data not shown). Analysis by flow cytometry of the T-cell lines used in this study indicated that both Dohyvac- and Leishmania-specific T-cell lines were Thy.1+, CD4+, and TCR α/β+ cells.

FIG. 1.

T-cell proliferation against cognate antigen is reduced when L. infantum-infected MDM are used as APC. Uninfected MDM or L. infantum-infected MDM (MDM-L) were used as APC. Cells were incubated in medium only (□) or in the presence of cognate antigen (▨). (a and b) A Dohyvac-specific T-cell line was stimulated with Dohyvac (a) or ConA (b). (c and d) A Leishmania-specific T-cell line was stimulated with LSA (c), and after 72 h supernatants were collected for determination of IFN-γ activity (d). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Data are representative of three independent experiments. SU, standard units.

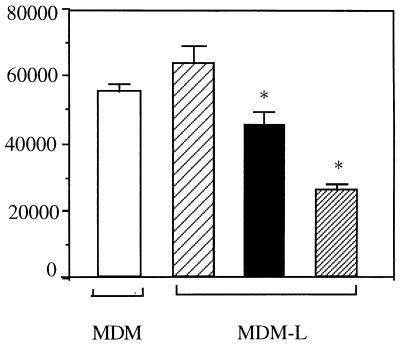

Reduced proliferation of an L. infantum-specific T-cell line upon stimulation by infected MDM is dependent on the parasite load.

To determine whether the number of intracellular parasites per macrophage influences the observed reduction of T-cell proliferative responses, MDM were infected at different parasite-to-MDM ratios and used as APC. When MDM were infected at a 50:1 ratio, reduction of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation to background levels was observed (Fig. 2). Infection of MDM at a 10:1 ratio led to a significant reduction of the T-cell proliferative response to LSA which, however, remained above background levels. In contrast, MDM infected at a 2:1 ratio and used as APC resulted in no reduction of the Leishmania-specific T-cell proliferative response to LSA. Infection carried out at a parasite-to-MDM ratio of 50:1 resulted in 96% ± 3% infected cells with 15 ± 2.9 intracellular parasites per infected cell. This number of parasites per infected cell can be found in dogs with visceral leishmaniasis. At a 10:1 parasite-to-MDM infection ratio, 70% ± 7% of the cells were infected, with 5 ± 2.5 intracellular parasites per infected MDM. Infection at a 2:1 ratio resulted in 30% ± 5% infected cells with 1.5 ± 1.0 intracellular parasites per infected MDM.

FIG. 2.

Effect of the parasite load of MDM on the proliferation of a Leishmania-specific T-cell line against LSA. Autologous uninfected MDM (□) or MDM infected at a 2:1 (▨), 10:1 (■), or 50:1 (▨) ratio were used as APC to stimulate a Leishmania-specific T-cell line. Background proliferation of T-cell lines incubated with APC and medium only ranged from 15,000 to 24,000 cpm. Results are expressed as mean ± SD counts per minute. ∗, significant difference from Leishmania-specific T cells stimulated with uninfected cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. MDM-L, L. infantum-infected MDM.

Decreased T-cell proliferation upon stimulation by Leishmania-infected MDM requires cell-to-cell interactions.

To determine whether infected MDM require cell-to-cell interactions with T cells for decreased proliferative responses to occur or whether these responses are mediated by soluble factors, a Transwell system was used. As shown in Table 1, no significant differences in the proliferative response of the Leishmania-specific T-cell line to LSA were observed when infected MDM were separated from responder cells by the semipermeable membrane relative to uninfected MDM and medium only. L. infantum-infected MDM were also cultured with the T-cell line in the lower compartment and medium only in the upper compartment; these conditions resulted in a reduction of the proliferative response to LSA to background levels. Thus, decreased T-cell proliferation in vitro does not appear to be mediated by soluble factors but instead seems to require cell-to-cell contact. An additional control experiment was performed by mixing MDM and L. infantum-infected MDM in the presence of LSA and Leishmania-specific T cells. Under these conditions, T-cell proliferation was restored, compared to the results obtained with L. infantum-infected MDM alone (data not shown). These results indicate that there is no contact-dependent suppression but rather a failure of infected MDM to stimulate antigen-specific T-cell proliferation.

TABLE 1.

Effect of coculturing with uninfected versus infected MDM on the proliferation of a Leishmania-specific T-cell line in a Transwell systema

| Upper compartment | Lower compartment | Proliferative response (cpm) |

|---|---|---|

| Med | Leish-T + MDM + Med | 9,650 ± 360 |

| Med | Leish-T + MDM + LSA | 34,206 ± 938 |

| MDM-L | Leish-T + MDM + LSA | 32,278 ± 1,151 |

| MDM | Leish-T + MDM + LSA | 29,282 ± 1,741 |

| Medb | Leish-T + MDM-L + LSA | 10,112 ± 1,151 |

Leishmania-specific T cells (Leish-T) (3 × 105) were cultured in the lower compartment with 3 × 104 irradiated (6,000 rads) autologous MDM as APC and 10 μg of LSA per ml or medium (Med) only to show background proliferation. To the upper compartment, 3 × 104 L. infantum-infected MDM (MDM-L) (infected at a 50:1 ratio), uninfected MDM, or medium (Med) only was added.

As a control to show the effect of infected MDM on T-cell prolifetation, 3 × 105 Leishmania-specific T cells were cultured in the lower compartment with 3 × 104 irradiated (6,000 rads) autologous L. infantum-infected MDM and 10 μg of LSA per ml. To the upper compartment, medium only was added.

Infection with L. infantum leads to changes in the expression of surface molecules on canine Mφ.

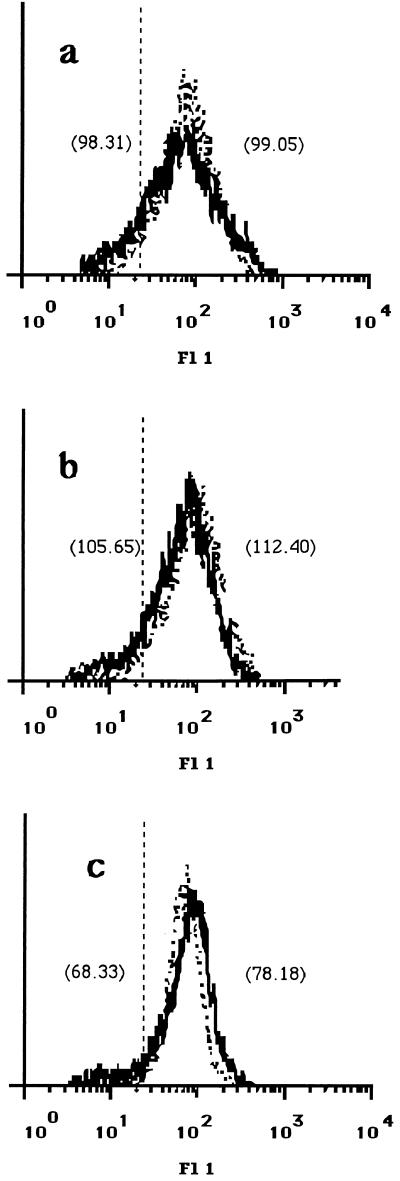

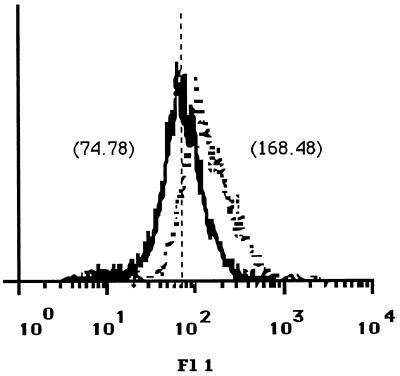

The observed decreased proliferative responses of the T-cell lines to parasite antigen may have resulted from altered expression on infected APC of surface molecules which are required for T-cell activation. As the TCR recognizes antigen as peptide fragments in the context of MHC molecules, we analyzed the expression of MHC class II and class I molecules on canine MDM before and after infection with L. infantum by flow cytometry. For this purpose, MDM were infected at a 50:1 infection ratio, which resulted in 98% ± 5% infected cells with 12 ± 3 parasites per infected MDM. Canine MDM that have been cultured for 5 days in vitro express both MHC class II and MHC class I molecules. At 24 h after infection, the expression of both MHC class II and MHC class I on infected MDM did not change compared to that on uninfected cells (Fig. 3a and b). Similar results were found 48 h after infection (data not shown). The expression of other molecules involved in interactions between APC and T cells, such as ICAM-1, was found to be marginally increased upon infection of MDM with L. infantum (Fig. 3c). In contrast, the expression of costimulatory B7 molecules on infected MDM was strongly decreased compared to that on uninfected cells (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Expression of MHC class I and class II and ICAM-1 on canine MDM. Monoclonal antibodies B1.1.G6 (a) directed against MHC class I, 7.5.10.1 (b) directed against MHC class II, and CL18.1D8 (c) directed against ICAM-1 were used to analyze the expression of these molecules on uninfected MDM (dotted line) and L. infantum-infected MDM (solid line) 24 h after infection. Scores of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are given in parentheses. MDM were infected at a 50:1 parasite-to-MDM ratio. Incubation of cells with an irrelevant mouse isotype control antibody resulted in an MFI of 13.70 (vertical broken line). The data shown are representative of four independent experiments. Fl 1, fluorescence.

FIG. 4.

Expression of B7 molecules on canine MDM. The expression of B7 molecules on uninfected MDM (dotted line) and L. infantum-infected MDM (solid line) was analyzed with fusion protein CTLA4-Ig. Scores of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are given in parentheses. As a control, human Ig was used and resulted in an MFI of 65.52 (vertical broken line). MDM were infected at a 50:1 parasite-to-MDM ratio. The data shown are representative of four independent experiments. Fl 1, fluorescence.

Compensation for decreased B7 expression on infected MDM results in restoration of Leishmania-specific T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production.

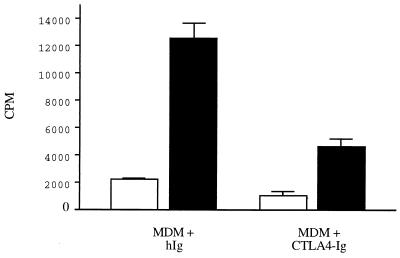

The importance of costimulatory B7 molecules for antigen-specific proliferation of canine T cells is shown in Fig. 5. The addition of CTLA4-Ig, which interacts with canine B7 molecules, in the presence of Leishmania-specific T cells, MDM as APC, and LSA resulted in decreased proliferative responses compared to those in cells incubated in the presence of human Ig, used as a control antibody.

FIG. 5.

T-cell proliferation against cognate antigen is dependent on interactions with B7 molecules. A Leishmania-specific T-cell line was restimulated with MDM as APC in the presence of LSA (■) or medium only (□). Cells were incubated in the presence of 10 μg of human IgG per ml used as a control antibody (hIg) or CTLA4-Ig. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± SD.

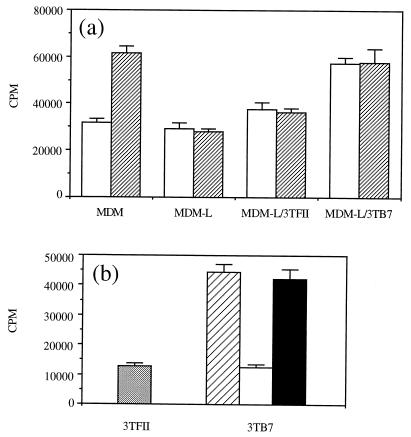

To investigate the relevance of the observed down-regulation of B7 expression on L. infantum-infected MDM for parasite-specific T-cell proliferation, B7-transfected fibroblasts were added to the cultures. Fig. 6a shows that the addition of transfected 3TB7 cells to T cells and L. infantum-infected MDM resulted in the restoration of parasite-specific T-cell proliferation compared to the proliferation of T cells cultured with infected MDM in the absence of 3TB7 or in the presence of untransfected 3TFII cells. T-cell proliferation was restored when cells were incubated with infected MDM and 3TB7 cells both in the presence of LSA and in medium only. The observed effect of transfected 3TB7 cells on Leishmania-specific T-cell proliferation was blocked when 3TB7 cells were incubated in the presence of 5 μg of a monoclonal antibody directed against human B7.1 molecules per ml compared to an isotype control antibody (Fig. 6b). From previous studies, it was shown that this monoclonal antibody does not cross-react with canine B7 molecules. The IFN-γ concentration in supernatants derived from T cells stimulated with infected MDM, LSA, and 3TB7 cells was 1,120 ± 226 standard units/ml; in contrast, this cytokine was undetectable in supernatants derived from T cells stimulated with infected MDM and LSA in the absence of 3TB7 cells or the presence of 3TFII cells.

FIG. 6.

Restoration of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation in the presence of infected APC is dependent on interactions with B7 molecules. (a) B7.1-transfected 3TB7 cells or untransfected 3TFII cells (1,000 cells/well) were added to a Leishmania-specific T-cell line incubated with L. infantum-infected MDM (MDM-L) in the presence of LSA (▨) or medium only (□). (b) A Leishmania-specific T-cell line was restimulated with LSA, infected MDM, and 3TFII cells (░⃞) or 3TB7 cells without a monoclonal antibody (▨), with a monoclonal antibody against human B7.1 molecules (□), or with a control monoclonal antibody (■). Background proliferation of T-cell lines incubated with infected MDM and medium only ranged from 13,055 to 16,062 cpm. Results are expressed as mean ± SD.

DISCUSSION

We previously showed that PBL from symptomatic dogs infected with L. infantum fail to respond both in vitro and in vivo to parasite antigens (28). T-cell unresponsiveness to parasite antigens was also reported for human visceral leishmaniasis (14, 35). However, following successful chemotherapy, T-cell responsiveness was found to be fully restored (5, 12). The cellular basis for T-cell unresponsiveness is still not fully understood. Since Leishmania parasites are obligate intracellular pathogens that reside within Mφ, several studies of the effect of infection on Mφ functions have been carried out. Infection of murine Mφ with L. donovani was shown to result in decreased expression of MHC class I and II molecules and interleukin 1 (IL-1) secretion (32, 33). In contrast, our studies showed that infection of canine MDM with L. infantum does not result in any significant change in the surface expression of MHC class I and II molecules. Others have also observed that decreased antigen-presenting capacity of L. major-infected murine Mφ could not be attributed to an unavailability of MHC class II molecules or impaired processing of antigen by the infected cells (10). These authors suggested that the presence of the parasites could interfere with the intracellular loading of MHC class II molecules with antigenic peptides.

Another possible mechanism by which decreased proliferation of T cells may occur is through the induction of soluble factors produced by infected Mφ. This mechanism has been shown for Mφ from BALB/c mice infected with L. donovani, for which the synthesis of prostaglandin E2, a known down-regulator of class II expression (37), was enhanced compared to that for uninfected Mφ. Cytokines such as transforming growth factor β, which was found to be associated with down-regulation of the activation of Th1-type cells involved in protective responses in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis, may be produced by Mφ upon infection (2). The alteration in the cytokine profile may vary depending on the origin of the Mφ and the species of Leishmania. Studies of murine leishmaniasis have shown that infecting Mφ with L. major results in very little, if any, production of cytokines such as IL-6, transforming growth factor β, IL-12, and IL-10 (6, 34). Using a Transwell system, we observed that cell-to-cell interactions are required for the decreased T-cell proliferation observed.

Several studies have shown that Leishmania-infected murine Mφ activate antigen-specific T cells less efficiently than uninfected cells (10, 21, 30). However, Chakkalath and Titus (6) showed that only Th1-type cells are less efficiently activated by L. major-infected Mφ, whereas Th2-type T-cell activation is enhanced in response to stimulation with infected Mφ and cognate antigen. In our study, both the proliferative response of and the amount of IFN-γ produced by the Leishmania-specific T-cell line were decreased after restimulation with LSA and L. infantum-infected Mφ compared to uninfected cells. Whether Th2-type cells are activated by infected Mφ in dogs is a question that could be addressed when tools to measure cytokines such as IL-4 become available. We have also shown that protective immunity is associated with a Th1 type of response in dogs, as indicated by parasite-specific proliferation of and IFN-γ production by PBL from L. infantum-infected asymptomatic dogs (29). Characterization of the mechanism by which the reactivity of Th1-type cells is down-regulated is of crucial importance for vaccine development or immunotherapy of leishmaniasis.

T-cell proliferation and induction of effector functions require the recognition of peptide-MHC complexes by the TCR and interactions between costimulatory molecules. The interaction between the B7 family of membrane molecules on APC and their receptors on T cells appears to be an important costimulatory signal (9, 19). We observed that B7 molecules play an important role in antigen-specific proliferation of canine T cells. An additional observation was the reduction of the expression of B7 molecules on infected canine MDM compared to uninfected cells. If this reduction were the cause of the observed reduction of T-cell proliferation when infected MDM were used as APC, proliferative responses could be restored by the addition of anti-CD28 antibodies. As no antibodies to canine CD28 molecules or cross-reactive antibodies are available, we tried to compensate for the decreased B7 expression on canine MDM by adding B7.1-transfected cells, which would provide in trans costimulation to T cells. This approach resulted in restoration of the proliferation of and IFN-γ production by a Leishmania-specific T-cell line, indicating an important role of these molecules in the activation of the Th1 type of parasite-specific T cells. In addition, we observed the restoration of T-cell proliferation after incubation with 3TB7 cells not only in the presence of LSA but also in medium only, suggesting that infected MDM can process and present antigen derived from intracellular parasites but fail to do so because of decreased B7 expression.

Deficient expression of B7.1 molecules on L. donovani-infected Mφ derived from BALB/c mice (16, 36) but not on infected C57BL/6 Mφ has been reported (36), suggesting that selective down-regulation of costimulatory molecules by Leishmania parasites may influence the outcome of the disease. Recently, Murphy et al. (24) reported that selective B7.2 blockade enhances T-cell responsiveness to L. donovani and was found to be associated with clearance of the parasites from the livers of infected mice. Selective manipulation of the expression of costimulatory molecules may be of importance for vaccine development. Probst et al. (31) have suggested LeIF, a Leishmania protein, as a Th1-type adjuvant due to its immunomodulatory characteristics, including up-regulation of the expression of B7.1 molecules.

In addition to the down-regulation of B7 molecules on infected MDM, we observed a marginal increase in the expression of ICAM-1. This finding has been described by others for the murine model of visceral leishmaniasis as well (36). These molecules not only have been implicated in regulating interactions between cells but also can directly contribute to lymphocyte activation (38, 39) and may play a role in the outcome of infection.

Our results show that decreased T-cell proliferation against cognate antigen is dependent on the parasite load. Furthermore, we observed that cells with infection ratios of 50:1 and 10:1 showed decreased expression of B7 molecules, whereas cells infected at 2:1 did not (data not shown). These results indicate that the parasite load plays an important role in the modulation of the immune response.

In conclusion, our results indicate that costimulatory B7 molecules are required for proliferation of and IFN-γ production by canine Leishmania-specific T cells. Down-regulation of the expression of costimulatory molecules on Mφ may serve as an additional mechanism used by these parasites to evade the protective immune responses of the host and may contribute to the impaired T-cell-mediated protective immune responses observed for patients with progressive visceral leishmaniasis. Compensation for decreased B7 expression on infected Mφ may be an approach for the immunotherapy of leishmaniasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rene van Lier and Claire Boog for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashford R W, Bettini S. Ecology and epidemiology: Old World. In: Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R, editors. Leishmaniasis in biology and medicine. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1987. pp. 365–424. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barral N M, Barral A, Brownell C E, Skeiky Y A, Ellingsworth L R, Twardzik D R, Reed S G. Transforming growth factor-beta in leishmanial infection: a parasite escape mechanism. Science. 1992;257:545–548. doi: 10.1126/science.1636092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bretscher P. The two signal model of lymphocyte activation twenty-one years later. Immunol Today. 1992;13:74–76. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90138-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabral M, O’Grady J, Alexander J. Demonstration of Leishmaniaspecific cell mediated and humoral immunity in asymptomatic dogs. Parasite Immunol. 1992;14:531–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1992.tb00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho E M, Teixeira R S, Johnson W D., Jr Cell-mediated immunity in American visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1981;48:409–414. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.498-500.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakkalath H R, Titus R G. Leishmania major-parasitized macrophages augment Th2-type T cell activation. J Immunol. 1994;153:4378–4387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Boer M, Parren P, Dove J, Ossendorp F, van der Horst G, Reeder J. Functional characterization of a novel anti-B7 monoclonal antibody. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:3071–3075. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doveren R F C, Buurman W A, Schutte B, Groenewegen G, Van der Linden C J. Class II antigens on canine T lymphocytes. Tissue Antigens. 1985;25:255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1985.tb00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman G J, Gray G S, Gimmi C D, Lombard D B, Zhou L, White M, Fingeroth J D, Gribben J G, Nadler L M. Structure, expression, and T cell costimulatory activity of the murine homologue of the human B lymphocyte activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174:625–631. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fruth U, Solioz N, Louis J A. Leishmania majorinterferes with antigen presentation by infected macrophages. J Immunol. 1993;150:1857–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebhard D H, Carter P B. Identification of canine T-lymphocyte subsets with monoclonal antibodies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;33:187–199. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90181-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haldar J P, Ghose S, Saha K C, Ghose A C. Cell-mediated immune response in Indian kala-azar and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1983;42:702–707. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.2.702-707.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handman E, Ceredig R, Mitchell G F. Murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: disease patterns in intact and nude mice of various genotypes and examination of some differences between normal and infected macrophages. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1979;57:9–30. doi: 10.1038/icb.1979.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho M, Koech D K, Iha D M, Bryceson A D M. Immunosuppression in Kenyan visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;51:207–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins M K. Models of lymphocyte activation. Immunol Today. 1992;13:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaye P M, Rogers N J, Curry A J, Scott J C. Deficient expression of co-stimulatory molecules on Leishmania-infected macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2850–2854. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemp M, Kurtzhals J A L, Bendtzen K, Poulsen L K, Hansen M B, Koech D K, Kharazmi A, Theander T G. Leishmania donovani-reactive Th1- and Th2-like T-cell clones from individuals who have recovered from visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1069–1073. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1069-1073.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liew F Y, O’Donell C A. Immunology of leishmaniasis. Adv Parasitol. 1993;32:161–259. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linsley P S, Brady W, Grosmaire L, Aruffo A, Damle N K, Ledbetter J A. Binding of the B cell activation antigen B7 to CD28 costimulates T cell proliferation and interleukin 2 mRNA accumulation. J Exp Med. 1991;173:721–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linsley P S, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire L S, Damle N K, Ledbetter J A. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174:561–569. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lytton S D, Mozes E, Jaffe C. Effect of macrophage infection by Leishmaniaon the proliferation of an antigen-specific T cell line, TPB1, to non-parasite antigen. Parasite Immunol. 1993;15:489–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1993.tb00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore P F, Rossitto P V. Development of monoclonal antibodies to the canine T cell receptor complex (TCR/CD3) and their utilization in the diagnosis of T cell neoplasia. Vet Pathol. 1993;30:457. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore P F, Rossitto P V, Olivry T. Development of monoclonal antibodies to canine T cell receptor-1 (TCR-γδ) and their utilization in the diagnosis of epidermotropic cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Vet Pathol. 1994;31:597. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy M L, Engwerda C R, Gorak P M A, Kaye P M. B7-2 blockade enhances T cell responses to Leishmania donovani. J Imunnol. 1997;159:4460–4466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nacy C A, Nelson B J, Meltzer M S, Green S J. Cytokines that regulate macrophage production of nitrogen oxides and expression of antileishmanial activities. Res Immunol. 1991;7:573–576. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(91)90105-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olivry T, Moore P F, Naydan D K, Danilenko D M, Affolter V K. Investigation of epidermotropism in canine mycosis fungoides: expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and beta-2 integrins. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:186–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01262330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinelli E, Boog C J P, Rutten V P M G, Van Dijk B, Bernadina W, Ruitenberg E J. A canine CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell line specific for Leishmania infantuminfected macrophages. Tissue Antigens. 1994;43:189–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1994.tb02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinelli E, Killick-Kendrick R, Wagenaar J, Bernadina W, del Real G, Ruitenberg E J. Cellular and humoral immune responses in dogs experimentally and naturally infected with Leishmania infantum. Infect Immun. 1994;62:229–235. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.229-235.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinelli E, Gonzalo R M, Boog C J, Rutten V P, Gebhard D, del Real G, Ruitenberg J. Leishmania infantum-specific T cell lines derived from asymptomatic dogs that lyse infected macrophages in a major histocompatibility complex-restricted manner. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1594–1600. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prina E, Jouanne C, de Souza Lao S, Szabo A, Guillet J-G, Antoine J-C. Antigen presentation capacity of murine macrophages infected with Leishmania amazonensisamastigotes. J Immunol. 1993;151:2050–2061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Probst P, Skeiky Y A W, Steeves M, Gervassi A, Grabstein K H, Reed S G. A Leishmaniaprotein that modulates interleukin (IL)-12, IL-10 and tumor necrosis factor-α production and expression of B7-1 in human monocyte-derived antigen presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2634–2642. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiner N E. Parasite-accessory cell interactions in murine leishmaniasis. I. Evasion and stimulus-dependent suppression of macrophage interleukin 1 response by Leishmania donovani. J Immunol. 1987;138:1919–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiner N E, Winnie N G, McMaster W R. Parasite-accessory cell interactions in murine leishmaniasis. II. Leishmania donovanisuppresses macrophage expression of class I and class II major histocompatibility complex gene products. J Immunol. 1987;138:1926–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiner S L, Zheng S, Wang Z E, Stowring L, Locksley R M. Leishmania promastigotes evade interleukin 12 (IL-12) induction by macrophages and stimulate a broad range of cytokines from CD4+T cells during initiation of infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:447–456. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacks D L, Lal S L, Shrivastava S N, Blackwell J, Neva F A. An analysis of T cell responsiveness in Indian kala-azar. J Immunol. 1987;138:908–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha B, Das G, Vohra H, Ganguly N K, Mishra G C. Macrophage-T cell interaction in experimental visceral leishmaniasis: failure to express costimulatory molecules on Leishmania-infected macrophages and its implication in the suppression of cell-mediated immunity. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2492–2498. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snyder D S, Lu C Y, Unanue E R. Control of macrophage Ia expression in neonatal mice—role of a splenic suppressor cell. J Immunol. 1982;128:1458–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Noesel C, Miedema F, Brouwer M, de Rie M A, Aarden L A, van Lier R A W. Regulatory properties of LFA-1α and β chains in human T cell activation. Nature. 1988;333:850–852. doi: 10.1038/333850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Seventer G A, Shimizu Y, Horgan K J, Ginther Luce G E, Webb D, Shaw S. Remote T cell co-stimulation via LFA-1/ICAM-1 and CD2/LFA-3: demonstration with immobilized ligand/mAb and implication in monocyte-mediated co-stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1711–1718. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]