Abstract

Asthma treatment goals currently focus on symptom and exacerbation control rather than remission. Remission is not identical to cure, but is a step closer. This review considers the current definitions of remission in asthma, the prevalence and predictors, the pathophysiology of remission, the possibility of achieving it using the available treatment options, and the future research directions. Asthma remission is characterised by a high level of disease control, including the absence of symptoms and exacerbations, and normalisation or optimisation of lung function with or without ongoing treatment. Even in those who develop a symptomatic remission of asthma, persistent pathological abnormalities are common, leading to a risk of subsequent relapse at any time. Complete remission requires normalisation or stabilisation of any underlying pathology in addition to symptomatic remission. Remission is possible as part of the natural history of asthma, and the prevalence of remission in the adult asthma population varies between 2% and 52%. The factors associated with remission include mild asthma, better lung function, better asthma control, younger age, early-onset asthma, shorter duration of asthma, milder bronchial hyperresponsiveness, fewer comorbidities and smoking cessation or never smoking. Although previous studies have not targeted treatment-induced remission, there is some evidence to show that the current long-term add-on therapies such as biologics and azithromycin can achieve some criteria for asthma remission on treatment, at least in a subgroup of patients. However, more research is required. Long-term remission could be included as a therapeutic goal in studies of asthma treatments.

Short abstract

As we are moving through a new era of highly effective targeted biologics, macrolides and precision medicine in asthma management, it is logical to consider a paradigm shift in the treatment goals from asthma control to asthma remission https://bit.ly/3N9nEqN

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic respiratory disease affecting over 300 million people around the world with significant morbidity and mortality [1]. It is a heterogeneous disease characterised by variable airflow limitation, bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR), mucus hypersecretion and airway inflammation, leading to airway narrowing which causes symptoms of wheeze, breathlessness and chest tightness for people with the disease [2]. Persistent or repeated inflammation of the airways may lead to airway structural changes such as epithelial hyperplasia and metaplasia, changes in mucus-secreting cells, subepithelial fibrosis, muscle cell hyperplasia, and angiogenesis. These pathological alterations in the airways may result in a change in composition, distribution, thickness, mass or volume and/or the number of structural components observed in the airway wall. This is believed to contribute to a progressive irreversible loss of lung function referred to as airway remodelling [3–5]. Based on the underlying pathological changes and the corresponding physiological consequences in the airways, people may experience mild, moderate, severe or refractory asthma. Some of these individuals also might be at risk of irreversible airway remodelling and/or fixed airflow limitation.

A fundamental feature of asthma is variability, characterised by inconsistency in the expression of the disease. While it is well recognised that variability in asthma may cause asthma attacks, it is less well understood that some people may spontaneously become asymptomatic with or without resolving their underlying pathological airway impairment and enter into a symptom-free state [6, 7]. This is referred to as “asthma remission”. These individuals who remit or resolve the manifestations of asthma constitute a very interesting cohort who have recently gained much attention among the research community [8, 9]. Understanding the mechanisms of remission may shed light on novel therapeutic approaches to asthma. In addition, a proportion of people who have achieved asthma remission or have “grown out of asthma” may relapse later in life. The reason for relapse is unclear, but it might be due to the ongoing dysfunction of underlying pathology. Consequently, these symptom-free patients have a certain risk of relapse, which may occur at any time, and this capricious phenomenon of diminution of disease is called remission [9–11].

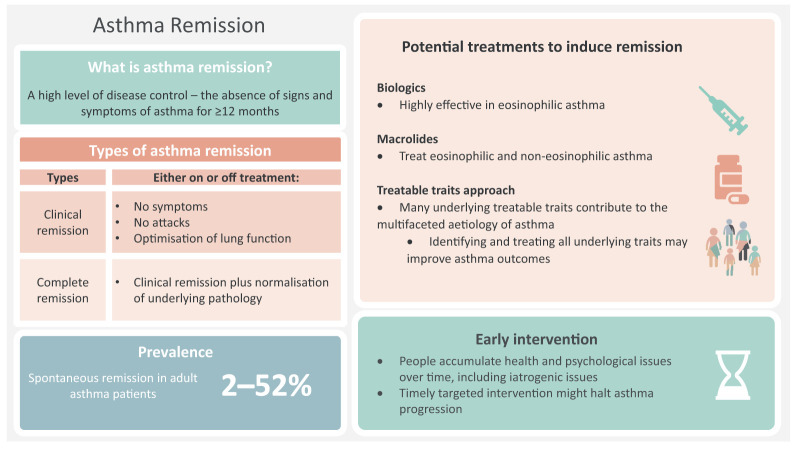

Although the term remission is rarely used in the current management of asthma, it is well defined in other chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and systemic lupus erythematosus [8, 12]. In asthma, the treatment goals are still minimisation of acute attacks and achievement of symptom control, with less attention paid to achieving remission. Furthermore, although remission in childhood asthma is a common phenomenon [13, 14], remission in adults with asthma is a relatively new concept and a less researched area that has, however, recently gained attention. Since remission is possible as part of the natural history of the disease (e.g. childhood asthma remission), it might also be possible to induce remission with treatments. Developing or identifying a treatment that can induce remission in asthma will be a paradigm shift in the asthma management goals, a step closer to the cure. Such success has already been achieved in rheumatoid arthritis, largely with the widespread use of effective targeted therapy using monoclonal antibodies [12, 15]. Effective monoclonal antibody therapies are now increasingly used in asthma [16, 17], raising the hope of asthma remission as a realistic therapeutic goal. In this review, we critically evaluate the current concept of asthma remission, what it constitutes, the prevalence and predictors of remission, the pathophysiology of remission, the possibility of achieving remission in the current clinical environment, and future research directions (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

A visual summary of remission. Content has been reproduced with permission from the Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits, originally developed as part of the Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits (https://treatabletraits.org.au).

Asthma remission: what is it?

Remission is not cure. Cure requires reversing to the normal pathological state of the airways in addition to prolonged absence of symptoms, typically in the absence of ongoing treatment requirements. An objective demonstration of normal airway function, normal airway responsiveness and the absence of any airway pathology suggestive of asthma are required to establish that asthma has been cured. Once cured, no treatment is required. Suboptimal treatment outcomes in asthma are mainly attributed to the fact that a large number of factors contribute to the clinical features of asthma and some are not modifiable. Moreover, it is far from clear whether currently available treatments normalise the underlying pathology such as airway remodelling. Hence, a cure for asthma may not be achievable in the current environment.

We may need a more realistic and achievable goal. The absence of signs and symptoms of a disease for a prolonged time with or without normalising underlying pathology may be referred to as remission. It can be a complete remission or partial remission based on the rigidity of the definition (e.g. no symptoms, absence of pathology, etc.) with or without background treatment [18]. In rheumatology, there was a shift in disease management after the introduction of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and targeted anti-tumour necrosis factor therapies from a treatment model aiming at disease control to disease remission [19–21]. It is now a logical time to consider a similar paradigm shift in the asthma management goals with the increased understanding of the pathobiology of asthma (e.g. the role of epithelial-derived cytokines in asthma) and the introduction of targeted biological therapies (e.g. mepolizumab, omalizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab and reslizumab) [9, 22–24].

Current definition

Menzies-Gow et al. [8] proposed a generalised framework for asthma remission based on the evidence from other chronic inflammatory diseases with remission definitions (rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and systemic lupus erythematosus) and considering the components of published definitions of spontaneous asthma remission. The framework derived from the literature was subject to a modified Delphi survey to gain expert consensus on the core elements of an asthma remission definition.

The authors produced four subtypes of asthma remission definitions with varying degrees of rigour in criteria [8]. Clinical remission requires stabilisation of lung function and patient/clinician agreement on remission in addition to absence of significant asthma symptoms and acute attacks for a minimum duration of 12 months, whereas complete remission also requires normalisation of underlying pathology (e.g. resolution of airway inflammation) in addition to clinical remission. Both are further subdivided into remission on treatment and off treatment.

Strengths and limitations of current definition

The definition of asthma remission derived by Menzies-Gow et al. [8] is comprehensive and covers the complex nature and impacts of the disease, including symptoms, acute attacks and airways pathology, and is applicable across the range of asthma severity. The definition also includes remission on treatment, which is a pragmatic and valuable goal in more severe asthma cases, albeit none of the previous studies that evaluated spontaneous asthma remission included remission on treatment. There are also four independent definitions of remission provided (table 1), and researchers and clinicians have the flexibility to adapt a definition that is achievable and measurable based on their clinical setting and study population.

TABLE 1.

Types and measures of asthma remission

| Type | Criteria | Assessments |

| Clinical remission | No symptoms | Sustained absence of significant asthma symptoms established using a validated instrument (e.g. ACQ score ≤1 or ACT score ≥20); the use of relievers is not permitted during the remission period |

| No exacerbations | The use of systemic corticosteroids for exacerbation treatment is not permitted during the remission period; hospitalisation or emergency department visit or unscheduled doctor visit for asthma exacerbation management are also not permitted during the remission period | |

| Optimisation of lung function | Example: post-bronchodilator FEV1 ≥80% predicted | |

| Complete remission | Clinical remission plus normalisation of underlying pathology | No evidence of current inflammation established using either blood eosinophil count (<300 cells·μL−1), sputum eosinophil count (<3%) or FENO (<40 ppb) [97, 98]; other measures of underlying pathology may include a negative bronchial hyperresponsiveness test (e.g. histamine or methacholine provocation tests) or degree of subepithelial fibrosis (subepithelial thickness) |

Both clinical and complete remission can be achieved either on treatment or off treatment. ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT: Asthma Control Test; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FENO: exhaled nitric oxide fraction. With acknowledgement of [8].

The Menzies-Gow et al. [8] definition for asthma remission is lenient on reliever (rapid-onset β2-agonist) use, which might be a questionable element. Rapid-onset β2-agonists are mainly used on an ad hoc basis to relieve symptoms when people experience symptoms. Since the absence of symptoms is one of the main criteria for remission in all four definitions, we propose the absence of reliever use also should be included. The authors acknowledge that the framework needs to be further tested in prospective studies, and streamlined based on input from experts, professional bodies and patients, so the opportunity exists to further develop this definition.

Assessment of remission

Recognition of remission requires an assessment of asthma status. Key variables may include evaluation of asthma symptoms and exacerbations, and assessment of lung function and underlying pathology. Table 1 summarises the key variables of asthma remission and measures to assess them.

Several validated tools exist for the assessment of symptoms in asthma; however, these have seldom been applied to the definition of remission. The Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) is a useful tool for reliably assessing symptoms in asthma and has established criteria for symptom control. Mean scores range from 0=no impairment to 6=maximum [25]. Harvey et al. [26] assessed super-response to mepolizumab therapy in severe asthma patients using a cut-off of <1 using the five-item ACQ (ACQ-5), indicating the value of an asthma control measure to address possible remission of symptoms in asthma. The Asthma Control Test (ACT) is another widely used tool to assess symptom control [27]. The total scores range from 5=poor asthma control to 25=complete asthma control. An ACT score >19 indicates well-controlled asthma. The PROSPERO (Prospective Observational Study to Evaluate Predictors of Clinical Effectiveness in Response to Omalizumab) study classified responders as an ACT score ≥20 [28], whereas Tuomisto et al. [29] used a cut-off of 25 in the Seinäjoki Adult-onset Asthma Study (SAAS). These studies indicate the potential to use asthma control measurements when assessing remission in future work.

Exacerbations, or attacks, are a key outcome in asthma. There are many criteria available to assess exacerbations such as attacks causing hospitalisation, emergency department visit or unscheduled doctor visit. The most widely used is the oral corticosteroid (OCS) burst, which records OCS treatment to manage acute attacks of asthma [26, 30]. Use of OCS for acute attack or long-term disease control is not permitted during the remission period.

Normal or stabilised lung function (e.g. normal spirometry assessments) and absence of airway inflammation (e.g. reduced blood or sputum eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide fraction (FENO), etc.) and BHR (e.g. histamine or methacholine provocation tests) are the other important factors that researchers and clinicians could consider including in the remission definition.

A broad range of symptom-free periods has been used in previous studies, ranging from 6 months to 3 years with an average of 1 year [10]. The minimum duration of 12 months seems to be reasonable, which will cover the seasonality of the disease activity. The majority of the clinical trials have a 12-month follow-up and hence it is feasible to use in research. However, wherever possible, a longer duration should be considered as disease stabilisation and relapse may depend on the length of remission [31].

The risk of relapse depends on how strict remission is defined. For example, the risk of relapse might be minimal for those who achieved “complete remission off treatment” with an ACT score of 25 for a long period of time [11]. However, it might not be feasible to achieve complete remission in all severities of asthma [10], and adapting a feasible and achievable remission definition based on the study population is important.

The super-responder model

Upham et al. [32] recently developed an international consensus-based definition for severe asthma super-responders using a modified Delphi process. The definition encompassed two domains: major and minor criteria. The major criteria include an absence of exacerbation, a large improvement in asthma control and cessation of maintenance OCS or weaning to adrenal insufficiency. The minor criteria were composed of a 75% exacerbation reduction, having well-controlled asthma and ≥500 mL improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). Improvement in three or more criteria (including at least two major criteria) assessed over 12 months is required to meet the super-responder definition. The proposed super-responder definition is more relaxed and looking for improvement rather than normalisation, and hence not meeting the requirements for remission. Two recent studies have identified severe asthma super-responders to biological agents, but they did not use the composite outcome remission [26, 32, 33]. Eger et al. [34] identified super-responders after 2 years of treatment with anti-interleukin (IL)-5 agents. The authors used a composite outcome (no chronic OCS use, no OCS bursts in the past 3 months, ACQ score <1.5, FEV1 ≥80% predicted, FENO <50 ppb and complete control of comorbidities, such as chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, chronic otitis, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis). Although this definition resembles remission, it was more lenient on OCS use, i.e. assessing OCS bursts only in the past 3 months and considering only the current use of maintenance OCS [34]. Remission represents an important step beyond super-response, eliminating exacerbations and asthma symptoms for a sustained period rather than reducing the number of attacks.

Prevalence and predictors of asthma remission

Many studies have evaluated the incidence of spontaneous remission in asthma. The rate varied considerably across studies mainly because of the clinical heterogeneity between study populations, designs, definitions and assessments. For example, age: these studies evaluated a range of age groups including children, adolescents and adults; used several design types such as birth cohort, cross-sectional surveys, extended follow-up of clinical trials and national databases; and applied variable rigour to the definition of remission, e.g. clinical and complete, length of remission (6 months to 3 years) and assessment methods (e.g. questionnaire-based and objective assessment) [8, 11]. The majority of these studies included a mix of childhood and adult asthma, which most likely caused an overestimation of the remission rate since the rate of remission in childhood asthma is much higher than that in adult asthma [35–37]. The overall incidence rate reported in these studies ranged from 2% to 74% and there was a higher incidence of clinical remission compared with complete remission [11].

Remission in the adult asthma population

A handful of studies (n=14) have evaluated the remission rate and factors associated with remission in the adult asthma population. Of these, five studies exclusively included new adult-onset asthma [29, 38–41]. Although the remaining nine studies included both adult- and childhood-onset asthma [42–50], the participants were adults at the time of enrolment. Tupper et al. [39] included 62% adult-onset asthma and 38% childhood-onset asthma, and their report includes only data from the former group. The studies were predominantly conducted in Europe. A majority of the studies (n=11) were longitudinal studies with a baseline assessment and a follow-up assessment. Two studies identified the asthma population from medical records and conducted a follow-up interview [43, 50], and one study was a cross-sectional survey [44]. The characteristics of the studies are presented in table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of studies that have evaluated adult asthma remission: study characteristics, prevalence and predictors of remission

| First author [ref .] | Study characteristics | Remission definition | Remission | Associated with remission | Comments |

| Adult-onset asthma | |||||

| Almqvist [38] | n=205; follow-up: 15.3 years; Sweden | No symptoms or asthma medications in past 12 months | 11.2% | Better lung function and less severe BHR | Objective assessment of asthma at baseline; population: asthma onset after 20 years; prospective longitudinal study |

| Tupper [39] | n=78; mean follow-up: 33.3 years; Denmark | No symptoms or asthma medications in past 12 months; FENO <50 ppb, no bronchodilator reversibility, no airway hyperresponsiveness and no airflow limitation | 17% | Shorter duration of asthma at baseline | Objective assessment of asthma both at baseline and follow-up; prospective longitudinal study |

| Westerhof [40] | n=170; follow-up: 5 years; the Netherlands | No symptoms or asthma medications in past 12 months | 15.9% | Independent predictors of remission include less BHR and no nasal polyps; remission was associated with younger age, better asthma control, lower doses of ICS and lower levels of blood neutrophils | Clinically assessed asthma at baseline; prospective longitudinal study |

| Tuomisto [29] | n=203; follow-up: 12.2 years; Finland | No asthma symptoms, ACT score 25, no asthma medication in last 6 months, no use of oral prednisolone in past 2 years; objective assessment of normal lung function | Clinical: 3%; normalisation of lung function: 2% | Better lung function and lower IgE level both at baseline and follow-up visit | Objective assessment of asthma at baseline and follow-up; asthma onset after adulthood (mean±sd baseline age 46±14 years); prospective longitudinal study |

| Rönmark [41] | n=250; follow-up: 5.8 years; Sweden | Clinical: no asthma symptoms and no asthma medications in past 12 months; complete: no medications, no symptoms, FEV1 >80% predicted and PC20 >8 mg·mL−1 | Clinical: 4.8%; complete: ∼3%# | Mild disease, normal lung function at onset, absence of allergic sensitisation, rhinitis and being a non-smoker | Objective assessment of asthma; asthma onset after 20 years; prospective longitudinal study |

| Adult at the time of enrolment | |||||

| Traulsen [42] | n=239; follow-up: 9 years; Denmark | No current use of asthma medications and no asthma symptoms in past 12 months | 28% | Use of medication at baseline | Questionnaire-based asthma diagnosis and remission; age at enrolment 20–44 years; 19% had asthma and COPD; prospective longitudinal study |

| Sözener [43] | n=160; follow-up: 7 years; Turkey | Clinical: no current use of asthma medications and no asthma symptoms in past 2 years; complete: no BHR (assessed in 50% of clinical remission cases) | Clinical: 11.3%; complete: of the 9 with BHR assessment, 3 achieved BHR normalisation | Younger age, younger onset, atopy, allergic rhinitis and few comorbidities | Asthma cohort identified from medical records and questionnaire survey at follow-up; mean±sd age at onset 35.8±11.4 years; retrospective cohort followed-up after 7 years |

| Pesce [44] | n=38 596; follow-up: 70 years; Italy | No asthma attacks in past 2 years and no current use of medications | 52% | Presence of hay fever, age at onset and time since asthma onset | Questionnaire-based asthma diagnosis; age at enrolment 20–84 years; cross-sectional cohort |

| Cazzoletti [45] | n=214; follow-up: 9 years; Italy | No current use of asthma medication, no asthma-like symptoms and no asthma attacks in past 12 months | 29.7% | Asthma control at baseline | Questionnaire-based asthma diagnosis and remission; age at enrolment 21–47 years; prospective longitudinal study |

| Lindström [50] | n=119; follow-up: 20 years; Finland | No asthma symptoms and using no asthma medication in past 3 years | 11.8% | Exercise test and spirometry results | Military servicemen in 1987–1990; age at enrolment 18–27 years (mean±sd 20.1±1.4 years); asthma diagnosis based on medical records (symptoms, medication use, lung function and allergy tests); retrospective cohort followed-up after 20 years |

| Ekerljung [49] | n=295; follow-up: 10 years; Sweden | No symptoms or asthma medications in past 12 months | 14.6% | Mild disease and no rhinitis | No objective assessments; population-based questionnaire surveys 10 years apart; age at enrolment 20–69 years; prospective longitudinal study |

| Holm [48] | n=1153; follow-up: ∼8.5 years; Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Sweden, Estonia | No asthma symptoms in 2 consecutive years and no current use of asthma medications | 18.6% | Quitting smoking and presence of mild disease at baseline | No objective diagnosis of asthma (i.e. self-reported questionnaire-based asthma at baseline); age at enrolment 26–53 years; prospective longitudinal study |

| de Marco [47] | n=586; follow-up: 9 years; Europe, North America and Oceania | No symptoms and no use of medications in past 12 months | 11.9% | Less severe asthma and lowest increase in body mass index | No objective diagnosis of asthma (i.e. self-reported questionnaire-based); age at enrolment 20–44 years (mean±sd 34±7 years); prospective cohort study |

| Rönmark [46] | n=267; follow-up: 10 years; Sweden | No asthma symptoms and no asthma medications in past 12 months | 6% | Mild disease and smoking cessation | Objective assessment of asthma; age at enrolment 35–66 years; prospective longitudinal study |

BHR: bronchial hyperresponsiveness; FENO: exhaled nitric oxide fraction; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; ACT: Asthma Control Test; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; PC20: provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in FEV1; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. #: visually presented in a figure.

The follow-up duration ranged from 5 to 33 years. All the adult-onset asthma studies used objective assessments to confirm asthma diagnosis, whereas only one study in the mixed adult/childhood-onset group used objective assessments [46]. The remission period evaluated ranged from 6 months to 3 years. The majority of studies assessed clinical remission (no symptoms and no asthma medications) for a duration of ≥12 months.

The incidence of remission in the adult-onset asthma population ranged from 2% to 17%, whereas it ranged from 6% to 52% in the other group. Three studies reported a remission rate <10%, eight reported 10–20% and four reported >20%. Four studies included some objective measures of remission and the rate ranged from 2% to 17%. All of these studies assessed spontaneous remission. It is important to note that none of the studies assessed treatment-induced remission, which identifies a significant knowledge gap that needs to be addressed.

The predictors of asthma remission are summarised in table 2. Baseline factors such as mild asthma [41, 46–49], better lung function [29, 38, 41], better asthma control [40, 45], younger age [40, 43], early-onset asthma [43, 44], shorter duration asthma [39, 44], milder BHR [38, 40], no/few comorbidities [40, 41, 43, 44, 49] and smoking cessation or never smoking [41, 46, 48] were consistently associated with remission. The majority of the listed factors are well established due to the fact that these are also inversely related to uncontrolled asthma [2]. An important factor which may influence remission might be the severity of the disease. The disease activity stays much the same over a longer period of time in moderate-to-severe asthma, while mild asthma cases are likely to experience remission [11]. This will have a major impact on the ability to achieve remission based on the population or asthma severity studied.

Pathophysiology of remission

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease. The aetiology and pathophysiology of asthma are complex and poorly understood. Moreover, there is a paucity of research that has sought to understand the pathophysiology of asthma remission. However, some previous research suggests that people with remitted asthma might still have some degree of ongoing inflammation, BHR and airway remodelling [10, 11, 51, 52], which may determine the future risk of relapse [53, 54].

Previous reviews have reported that the level of airway inflammation is related to the development of asthma remission over time [10, 55]. Carpaij et al. [11] reviewed the studies comparing inflammatory markers in people with asthma remission and current asthmatic and/or healthy individuals. The authors noted that inflammatory markers were generally lower in remission compared with current asthma, but higher compared with healthy individuals, albeit some studies report no difference between groups [11, 56, 57]. Likewise, some previous studies have shown that BHR persists in a considerable proportion of people with symptomatic asthma remission [54, 56, 58]. Chronic or frequent inflammation in asthma may damage the surface epithelium of the airways leading to airway remodelling. A specific characteristic of airway remodelling is thickening of the subepithelial reticular basement membrane resulting from subepithelial fibrosis. It can even occur in the early stages of life and is more prominent in severe disease [59]. The consequences of airway remodelling may include increased BHR, fixed airflow limitation and irreversible loss of lung function. The exact sequence of events that take place during the remodelling process is hard to disentangle and the mechanisms regulating these changes are poorly understood; studies assessing airway remodelling in asthma remission are also scarce. Available evidence suggests that basement membrane thickening is still present in asthma remission [11, 53, 60]. These findings indicate that some aspects of asthma pathophysiology remain during remission. However, the results should be interpreted with some caution, carefully considering the clinical heterogeneity between studies. For example, factors such as asthma severity of the included population, duration of asthma, duration of remission and rigour of remission definition may modify the underlying pathology and affect the study results [57].

The question remains, how will this ongoing airway inflammation and remodelling affect asthma remission, and how it can be effectively treated to prevent relapse in those who are in clinical remission? Currently, there are no effective treatments that halt or reverse the changes of airway remodelling and its effects on lung function. Existing asthma treatments are aimed at controlling airway inflammation and may subsequently reduce the progress of airway remodelling. However, this approach is only partially successful in treating airway remodelling. The search for novel therapies that can directly target individual components of the remodelling process should be made a priority, which may provide a more effective strategy to prevent or reverse structural changes and restore lung function. The interrelationship between airway remodelling, inflammation and BHR should be clearly evaluated and demonstrated. A clear understanding of the molecular events leading to airway remodelling and factors influencing each of the components of remodelling may facilitate the development of new treatment approaches [5].

Another important element contributing to asthma pathobiology is genetic. Although previous genome-wide association studies have identified multiple genes associated with asthma origin and remission, more research is required in this area [61].

Enablers and challenges of achieving asthma remission

The multifaceted aetiology and the complex pathology make asthma a difficult disease to cure. Although advances in asthma treatments have improved the symptoms of asthma and reduced the frequency of attacks and the overall burden experienced by people with asthma, the treatments and advances in care still fail to cure the disease, and to date, asthma treatment has mainly focused on disease control over cure. A few studies have identified super-responders to biological agents [26, 33], a step closer to remission [32], but these failed to evaluate their effectiveness in inducing remission. Previous work which demonstrated that a certain percentage of individuals spontaneously outgrow the disease for a certain period of time, or the rest of their lives, is promising. The question is whether the proportion of individuals attaining remission can be increased or is it possible to prolong the remission period with treatment?

The lack of disease-modifying agents in asthma is a weakness. Reversing the remodelling that has already occurred might be a challenge that requires the development of new therapies. Although the person with asthma may be asymptomatic in remission, the underlying disease might be active and continuing to progress, and treatment with ongoing anti-inflammatory agents might be useful [18]. This is an important lesson in asthma, since history reveals that minimising symptoms with β-agonists without addressing the underlying airway inflammation is associated with severe acute attacks and asthma deaths. This lesson would argue that a proposed clinical definition of remission, and seeking treatments to induce remission, may be risky without an accompanying measure of airway pathophysiology in asthma.

Treatments to induce remission

The introduction of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in the 1980s has revolutionised asthma treatment and currently they are the cornerstone of asthma therapy. Although ICS are generally very effective in reducing asthma symptoms, preventing exacerbations and improving lung function in mild-to-moderate asthma, their ability to alter the natural history of asthma and effectiveness on disease progression are questionable [62, 63]. Likewise, the introduction of a combination of inhaled ICS and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) further improved asthma management, but their effectiveness on disease progression needs to be evaluated [64].

Biologics

Over the past decade, greater awareness of the underlying biology of asthma has led to the development of a new range of treatment targets. Researchers understood that the multifaceted aetiology of asthma includes many phenotypes caused by a variety of pathophysiological mechanisms referred to as endotypes. Two inflammatory subtypes are currently identified: the type 2 (T2)-high and T2-low inflammatory pathways. The inflammatory cascade is often initiated by inhaled allergens, microbes or pollutants that interact with the airway epithelium. This interaction leads to the activation of mediators such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-25 and IL-33. Subsequent immune cell activation (type 2 innate lymphoid cells, T-helper 2 cells, etc.) releases IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, leading to the attraction and activation of basophils, eosinophils, mast cells and immunoglobulin class switching and secretion of IgE by B-cells. This inflammatory process leads to bronchoconstriction, BHR, mucus production and subsequent airway remodelling [65]. Current biological agents such as omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab, reslizumab and dupilumab mainly act on the effector molecules of the T2 inflammatory cascade (i.e. IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IgE) [66]. Newer agents targeting the upstream targets of T2 inflammation (i.e. TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33) are under development [67]. Biologics are a promising tailored treatment approach for eosinophilic asthma with a high potential to achieve disease remission in at least a subset of patients [26, 30]. The improved efficacy achieved when biologics are added to previous treatment may meet the criteria for remission. However, it is challenging to evaluate the effectiveness of biologics in inducing remission using the current evidence since the majority of the previous studies aimed for disease control rather than remission.

Menzies-Gow et al. [9] evaluated the efficacy of biologics in inducing remission using the current evidence. The authors critically reviewed the current studies, and retrospectively extracted and constructed data related to remission. They used the remission definition “clinical remission on treatment”. The authors concluded that biologics are highly effective in reducing exacerbations and symptoms, and in improving lung function. These treatments achieve some, but in most cases not all, criteria for remission.

A recent post hoc analysis of dupilumab found that 20% of the dupilumab-treated participants achieved clinical remission (no exacerbation, ACQ-5 score <1.5 and post-bronchodilator FEV1 ≥80%) at 12 months [68]. Hence, dupilumab has the potential to achieve asthma remission in a subset of people with severe asthma. However, the study was a post hoc analysis and it is important to include this outcome as an objective in future study designs.

The Harvey et al. [26] super-responder study found that 31% of severe asthma patients treated with mepolizumab achieved well-controlled asthma (ACQ-5 score <1). Of those, 67% were free of OCS burst and 79% were free of maintenance OCS therapy. Although the study failed to identify the proportion of patients achieving the composite outcome remission, it provided an insight into the potential of mepolizumab in achieving remission in a subset of patients with severe asthma. The Eger et al. [34] super-responder model was more or less similar to the proposed remission definition and 14% (16 out of 141) of patients treated with anti-IL-5 agents achieved the composite criteria. Shorter asthma duration, higher FEV1 and adult asthma onset predicted super-response.

Biologics were initially used in rheumatology for end-stage severe disease conditions, but were later integrated at an earlier stage of disease management to modify disease progression, which resulted in a durable and treatment-free remission in some patients [69, 70]. Asthma clinicians and researchers can learn from this experience and identify the future role of biologics in the management of asthma. Achieving remission in mild-to-moderate cases may help to hinder the further deterioration of airway remodelling and lung function decline, leading to more severe and uncontrolled asthma. Conceptually, timely introduction of biologics therapy may weaken the inflammatory process at the earlier stages of disease activity, restricting the exposure of inflammatory mediators to the airway wall, lowering the potential for airway remodelling and halting the disease progression.

Since it is believed that underlying inflammation has a role in relapse, continuing the treatment with biologics might be an option to prolong remission and prevent relapse [71], although this needs to be evaluated in clinical trials. The dosing frequency of biologics is convenient, requiring administration only once a fortnight, month or every 2 months, depending on the treatment. It might also be logical to think about and explore the possibility of stopping all asthma treatments except biologics in a patient who has achieved remission with biological therapies. Continuing ongoing treatment with biologics may help to control underlying inflammation and subsequent relapse. In the COLUMBA (Open-label Long Term Extension Safety Study of Mepolizumab in Asthma Subjects) trial, 33% of participants did not experience exacerbation during the average 3.5-year study period [72]. Moreover, the COMET study assessed the clinical impact of stopping mepolizumab after 3 years of use. The authors concluded that stopping mepolizumab was significantly associated with a shorter duration to first clinically significant exacerbation and reduced asthma control [73].

The effect of biologics on airway remodelling needs to be investigated. Previous research reported some beneficial effects [74–76]. A recent study found anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody lebrikizumab reduced the degree of subepithelial fibrosis and T2-high biomarkers in addition to improved lung function [75]. Anti-IgE monoclonal antibody omalizumab also improved airway structure and decreased inflammatory markers in many previous studies [76–81], although one recent small study reported no benefit on airway remodelling [82]. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to show whether biologics can truly maintain improved airway structure.

Additionally, these agents are relatively newer therapies and their long-term safety profiles are still emerging. Moreover, the long-term consequences of blocking a biological pathway for the lifetime in an individual need to be explored.

Macrolide antibiotics

Low-dose long-term azithromycin (a macrolide antibiotic) significantly reduced asthma attacks in both eosinophilic asthma and non-eosinophilic asthma [83, 84]. Although azithromycin meets some criteria for remission (e.g. more than half of the patients in the azithromycin group did not experience attacks during the 12-month study period and azithromycin treatment improved asthma control, measured using ACQ-6), further research is required to evaluate its effectiveness in inducing sustained remission. Azithromycin has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties and is cost-effective, and current guidelines recommend its use in severe asthma [23, 85, 86]. Azithromycin also could be considered for non-eosinophilic asthma in which no other promising treatment options are currently available. However, concerns such as the potential for anti-microbial resistance and side-effects, including cardiac, sensory and gastrointestinal effects, may limit its widespread use [86, 87].

Although the exact mechanism of action of azithromycin in asthma is yet to be determined, it is believed that azithromycin operates by non-T2 pathways [88]. The alternate mechanism of action of azithromycin provides an opportunity to combine it with biologics, and that might provide additional benefits and may address residual disease burden (ongoing exacerbations despite treatment) of individual treatment.

The treatable traits concept

Many underlying treatable conditions contribute to the multifaceted aetiology of asthma, deterioration of health-related quality of life in patients and suboptimal response to treatment [89]. The most prominent underlying risk factors in severe asthma include airflow limitation, eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic inflammation (also termed T2-high and T2-low disease), obstructive sleep apnoea, vocal cord dysfunction, inhaler device polypharmacy and non-adherence, upper airway disease, physical inactivity and obesity, systemic inflammation, anxiety and depression, and being exacerbation prone [90–92]. These treatable underlying conditions are referred to as treatable traits [93, 94]. Researchers identified an average of 10 treatable traits in severe asthma patients [89, 91, 92]. The treatable traits concept has several useful implications for asthma remission. Since traits such as comorbidity and smoking are associated with remission, and some underlying comorbid conditions may trigger asthma-like symptoms and/or worsen asthma severity, it is possible that targeting treatable traits may increase the chance of asthma remission; however, this approach should be assessed in clinical studies. Remission includes the absence of asthma symptoms. It is hard to disentangle the symptoms caused by airflow limitation and other comorbid conditions, such as vocal cord dysfunction, and this may lead to inappropriate asthma assessment or symptom misattribution [95]. A treatable traits assessment will identify these other conditions, and identify and treat symptom misattribution, leading to a more accurate assessment of remission. Current treatments are mainly focused on airflow limitation, airway inflammation and exacerbation control, and the other traits are largely neglected. To achieve remission in severe asthma patients, we propose identifying and treating all underlying behavioural and biological treatable risk factors, so that their effect on asthma is minimised. It is crucial considering the absence of comorbidities was one of the key variables associated with remission in multiple spontaneous remission studies.

The trajectory of remission

Complete remission off treatment is the ultimate goal of asthma management and it essentially constitutes a cure. It might not always be achievable and measurable in the current environment, but nevertheless should remain as a goal. Aiming for complete remission in populations with early-onset and mild asthma, and aiming for clinical remission on or off treatment in more severe and treatment-refractory asthma populations, might be a practical and achievable approach.

The exact trajectory of remission still needs to be explored and defined. However, in most cases, achieving clinical remission on treatment might be the initial step and then aiming for complete remission. Hence, the initial aim of achieving remission is to eliminate the exacerbations and symptoms, and halt disease progression and further damage to the airway wall, which will help the people to live a normal life. Subsequently steps should then aim to normalise the impairment already caused by the disease.

Future research should explore the possibility of withdrawing treatment after achieving remission and it may not be possible in more severe cases, at least in the current scenario. Identifying the predictors and markers of successful treatment withdrawal will assist clinicians in trying deprescribing.

The way forward

The question arising is in what direction do scientists need to delve to discover a definitive cure for asthma? Is there a silver bullet to treat asthma? The current answer is no. However, observations of spontaneous asthma remission (table 2) offer hope that this may be possible. An analysis of patients treated with available treatment options such as biologics and macrolides might be useful to assess the proportion of people meeting the criteria for remission with these treatments. Better characterisation of patients responding to available therapies will help to streamline the treatment (e.g. some may respond to a particular biological agent and some may respond to macrolides or emerging therapies). Treatment should also target other modifiable underlying risk factors. A combination of therapies could also be considered to cover the multifaceted aetiology of asthma.

It is also important to identify the areas of remission that are met and not met with current treatments, which will help to identify the unmet areas for further research [9]. Additionally, it is also crucial to identify the factors associated with lung function decline and develop treatments that could alter disease progression. Furthermore, evaluating the effect of early intervention to halt the onset of asthma or disease progression is also important as an early intervention might halt or delay the progression of the disease [96]. This is vital as people accumulate health and psychological issues over time, including iatrogenic issues, and timely intervention might radically modify this process. Table 3 presents a number of critical research questions associated with asthma remission. Of those, the priority might be producing an international consensus on the remission definition.

TABLE 3.

Asthma remission: future research questions

| Definition | |

| 1 | Does the definition of remission require measurement of inflammation? |

| 2 | How do asthma control and severity relate to asthma remission? |

| Treatment-induced remission | |

| 3 | Is treatment-induced remission possible? |

| 4 | How does treatment-induced remission compare with spontaneous asthma remission, based on prevalence, predictors and risk of relapse? |

| 5 | Is it possible to increase the proportion of people achieving remission with treatment? |

| 6 | Is it possible to prolong the remission period with treatment? |

| 7 | What are the rates of remission with MART and step therapy? |

| 8 | Does prolonging asthma treatment after control is achieved increase the chance of asthma remission? |

| Trajectory of remission | |

| 9 | How long should the treatment be continued to achieve remission? When to move from one stage to another? |

| Pathophysiology | |

| 10 | What are the molecular events leading to airway remodelling? |

| 11 | Can airway remodelling be treated? |

| 12 | Does treating airway remodelling induce remission? |

| Relapse | |

| 13 | How does ongoing airway inflammation and remodelling affect relapse? |

| 14 | How can inflammation/remodelling be effectively treated to prevent relapse in those who are in clinical remission? |

| Biologics and asthma remission | |

| 15 | What is the prevalence of remission after biologics therapy for asthma? |

| 16 | Are biologics more effective than inhaled preventers at achieving asthma remission? |

| 17 | Does the early introduction of biologics modify the trajectory of asthma and halt the disease progression? |

| 18 | Does continuing the treatment with biologics prolong remission and prevent relapse? |

| 19 | Is it possible to stop all asthma treatments except biologics in a patient who has achieved remission with biological therapies? |

| Macrolide therapy | |

| 20 | What is the prevalence of remission after macrolide therapy for asthma? |

| Treatable traits | |

| 21 | Does targeting treatable traits increase the chance of asthma remission? |

MART: maintenance and reliever therapy.

Asthma guidelines in the future should also include a definition for remission as a treatment goal that could be implemented by researchers. Nevertheless, by acknowledging the aforementioned factors and evaluating the promising research skyline, we are much closer to reaching the treatment goal of remission in asthma management.

Shareable PDF

Footnotes

Number 7 in the series “Innovations in asthma and its treatment” Edited by P. O'Byrne and I. Pavord

Previous articles in this series: No. 1: Asher MI, García-Marcos L, Pearce NE, et al. Trends in worldwide asthma prevalence. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2002094. No. 2: Hinks TSC, Levine SJ, Brusselle GG. Treatment options in type-2 low asthma. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2000528. No. 3: O'Byrne PM, Reddel HK, Beasley R. The management of mild asthma. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2003051. No. 4: Pijnenburg MW, Frey U, De Jongste JC, et al. Childhood asthma: pathogenesis and phenotypes. Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2100731. No. 5: Riccardi D, Ward JPT, Yarova PL, et al. Topical therapy with negative allosteric modulators of the calcium-sensing receptor (calcilytics) for the management of asthma: the beginning of a new era? Eur Respir J 2022; 60: 2102103. No. 6: Mortimer K, Reddel HK, Pitrez PM, et al. Asthma management in low- and middle-income countries: case for change. Eur Respir J 2022; 60: 2103179.

Conflict of interest: D. Thomas has nothing to disclose. V.M. McDonald reports grants and personal fees from GSK and AstraZeneca, and personal fees from Menarini, outside the submitted work. I.D. Pavord reports speaker's honoraria for sponsored meetings from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Aerocrine, Almirall, Novartis, Teva, Chiesi, Sanofi, Regeneron and GSK; payments for organising educational events from AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi, Regeneron and Teva; honoraria for attending advisory panels with Genentech, Sanofi, Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Merck, Circassia, Chiesi, Knopp, Almirall, Dey Pharma, Napp Pharmaceuticals, RespiVert and Schering-Plough; sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, AstraZeneca, Teva, Sanofi, Regeneron and Chiesi; grants from Chiesi to support a Phase II clinical trial in Oxford; and is co-patent holder of the rights to the Leicester Cough Questionnaire and has received payments for its use in clinical trials from Merck, Bayer and Insmed. P.G. Gibson reports grants and personal fees from GSK and AstraZeneca, and personal fees from Novartis, Chiesi and Sanofi, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Global Asthma Network . The Global Asthma Report 2018. 2018. http://globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2018.pdf Date last accessed: 26 March 2022.

- 2.Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 143–178. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousquet J, Jeffery PK, Busse WW, et al. Asthma: from bronchoconstriction to airways inflammation and remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161: 1720–1745. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9903102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fehrenbach H, Wagner C, Wegmann M. Airway remodeling in asthma: what really matters. Cell Tissue Res 2017; 367: 551–569. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2566-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang ML, Wilson JW, Stewart AG, et al. Airway remodelling in asthma: current understanding and implications for future therapies. Pharmacol Ther 2006; 112: 474–488. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpaij OA, Nieuwenhuis MA, Koppelman GH, et al. Childhood factors associated with complete and clinical asthma remission at 25 and 49 years. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601974. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01974-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vonk J, Postma D, Boezen H, et al. Childhood factors associated with asthma remission after 30 year follow up. Thorax 2004; 59: 925–929. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.016246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menzies-Gow A, Bafadhel M, Busse WW, et al. An expert consensus framework for asthma remission as a treatment goal. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145: 757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menzies-Gow A, Szefler SJ, Busse WW. The relationship of asthma biologics to remission for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upham JW, James AL. Remission of asthma: the next therapeutic frontier? Pharmacol Ther 2011; 130: 38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpaij OA, Burgess JK, Kerstjens HA, et al. A review on the pathophysiology of asthma remission. Pharmacol Ther 2019; 201: 8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlager L, Loiskandl M, Aletaha D, et al. Predictors of successful discontinuation of biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission or low disease activity: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology 2020; 59: 324–334. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin AJ, McLennan LA, Landau LI, et al. The natural history of childhood asthma to adult life. Br Med J 1980; 280: 1397–1400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6229.1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phelan PD, Robertson CF, Olinsky A. The Melbourne Asthma Study: 1964–1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109: 189–194. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.120951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold S, Jaeger VK, Scherer A, et al. Discontinuation of biologic DMARDs in a real-world population of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission: outcome and risk factors. Rheumatology 2021; 61: 131–138. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trevor J, Lugogo N, Carr W, et al. Severe asthma exacerbations in the United States: incidence, characteristics, predictors, and effects of biologic treatments. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021; 127: 579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rupani H, Murphy A, Bluer K, et al. Biologics in severe asthma – which one, when and where? Clin Exp Allergy 2021; 51: 1225–1228. doi: 10.1111/cea.13989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Toorn LM, Overbeek SE, Prins J-B, et al. Asthma remission: does it exist? Curr Opin Pulm Med 2003; 9: 15–20. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200301000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emery P, Salmon M. Early rheumatoid arthritis: time to aim for remission? Ann Rheum Dis 1995; 54: 944. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.12.944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, Huizinga TW. Can we achieve true drug-free remission in patients with RA? Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6: 68–70. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Tuyl LH, Felson DT, Wells G, et al. Systematic review: evidence for predictive validity of remission on long term outcome in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2010; 62: 108. doi: 10.1002/acr.20021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell PD, O'Byrne PM. Biologics and the lung: TSLP and other epithelial cell-derived cytokines in asthma. Pharmacol Ther 2017; 169: 104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holguin F, Cardet JC, Chung KF, et al. Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1900588. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00588-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busse WW. Biological treatments for severe asthma: a major advance in asthma care. Allergol Int 2019; 68: 158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juniper EF, Svensson K, Mörk A-C, et al. Measurement properties and interpretation of three shortened versions of the asthma control questionnaire. Respir Med 2005; 99: 553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harvey ES, Langton D, Katelaris C, et al. Mepolizumab effectiveness and identification of super-responders in severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1902420. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02420-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casale TB, Luskin AT, Busse W, et al. Omalizumab effectiveness by biomarker status in patients with asthma: evidence from PROSPERO, a prospective real-world study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 7: 156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuomisto LE, Ilmarinen P, Niemelä O, et al. A 12-year prognosis of adult-onset asthma: Seinäjoki Adult Asthma Study. Respir Med 2016; 117: 223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas D, Harvey ES, McDonald VM, et al. Mepolizumab and oral corticosteroid stewardship: data from the Australian Mepolizumab Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 9: 2715–2724. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruo H. [The relapse rate in patients with bronchial asthma remission and the risk factors of relapse]. Arerugi 1999; 48: 425–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Upham JW, Le Lievre C, Jackson DJ, et al. Defining a severe asthma super-responder: findings from a Delphi process. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 9: 3997–4004. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kavanagh JE, d'Ancona G, Elstad M, et al. Real-world effectiveness and the characteristics of a “super-responder” to mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest 2020; 158: 491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eger K, Kroes JA, Ten Brinke A, et al. Long-term therapy response to anti-IL-5 biologics in severe asthma – a real-life evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 9: 1194–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tai A, Tran H, Roberts M, et al. Outcomes of childhood asthma to the age of 50 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133: 1572–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bisgaard H, Bønnelykke K. Long-term studies of the natural history of asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: 187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almqvist L, Rönmark E, Stridsman C, et al. Remission of adult-onset asthma is rare: a 15-year follow-up study. ERJ Open Res 2020; 6: 00620-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00620-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tupper OD, Håkansson KEJ, Ulrik CS. Remission and changes in severity over 30 years in an adult asthma cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 9: 1595–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westerhof GA, Coumou H, de Nijs SB, et al. Clinical predictors of remission and persistence of adult-onset asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rönmark E, Lindberg A, Watson L, et al. Outcome and severity of adult onset asthma – report from the obstructive lung disease in northern Sweden studies (OLIN). Respir Med 2007; 101: 2370–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traulsen LK, Halling A, Bælum J, et al. Determinants of persistent asthma in young adults. Eur Clin Respir J 2018; 5: 1478593. doi: 10.1080/20018525.2018.1478593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sözener ZÇ, Aydın Ö, Mungan D, et al. Prognosis of adult asthma: a 7-year follow-up study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 114: 370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pesce G, Locatelli F, Cerveri I, et al. Seventy years of asthma in Italy: age, period and cohort effects on incidence and remission of self-reported asthma from 1940 to 2010. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0138570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cazzoletti L, Corsico AG, Albicini F, et al. The course of asthma in young adults: a population-based nine-year follow-up on asthma remission and control. PLoS One 2014; 9: e86956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rönmark E, Jönsson E, Lundbäck B. Remission of asthma in the middle aged and elderly: report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden study. Thorax 1999; 54: 611–613. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Marco R, Marcon A, Jarvis D, et al. Prognostic factors of asthma severity: a 9-year international prospective cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: 1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holm M, Omenaas E, Gíslason T, et al. Remission of asthma: a prospective longitudinal study from northern Europe (RHINE study). Eur Respir J 2007; 30: 62–65. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ekerljung L, Rönmark E, Larsson K, et al. No further increase of incidence of asthma: incidence, remission and relapse of adult asthma in Sweden. Respir Med 2008; 102: 1730–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindström I, Suojalehto H, Lindholm H, et al. Positive exercise test and obstructive spirometry in young male conscripts associated with persistent asthma 20 years later. J Asthma 2012; 49: 1051–1059. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.733992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mak JC, Ho SP, Ho AS, et al. Sustained elevation of systemic oxidative stress and inflammation in exacerbation and remission of asthma. ISRN Allergy 2013; 2013: 561831. doi: 10.1155/2013/561831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broekema M, Volbeda F, Timens W, et al. Airway eosinophilia in remission and progression of asthma: accumulation with a fast decline of FEV1. Respir Med 2010; 104: 1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van den Toorn LM, Overbeek SE, de Jongste JC, et al. Airway inflammation is present during clinical remission of atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 2107–2113. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2006165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boulet L-P, Turcotte H, Brochu A. Persistence of airway obstruction and hyperresponsiveness in subjects with asthma remission. Chest 1994; 105: 1024–1031. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.4.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuchs O, Bahmer T, Rabe KF, et al. Asthma transition from childhood into adulthood. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 224–234. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30187-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Toorn LM, Prins J-B, Overbeek SE, et al. Adolescents in clinical remission of atopic asthma have elevated exhaled nitric oxide levels and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162: 953–957. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9909033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boulet L-P, Turcotte H, Plante S, et al. Airway function, inflammation and regulatory T cell function in subjects in asthma remission. Can Respir J 2012; 19: 19–25. doi: 10.1155/2012/347989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mochizuki H, Muramatsu R, Hagiwara S, et al. Relationship between bronchial hyperreactivity and asthma remission during adolescence. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009; 103: 201–205. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60182-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Payne DN, Rogers AV, Ädelroth E, et al. Early thickening of the reticular basement membrane in children with difficult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 78–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-414OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Broekema M, Timens W, Vonk JM, et al. Persisting remodeling and less airway wall eosinophil activation in complete remission of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 310–316. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0494OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vonk J, Nieuwenhuis M, Dijk F, et al. Novel genes and insights in complete asthma remission: a genome-wide association study on clinical and complete asthma remission. Clin Exp Allergy 2018; 48: 1286–1296. doi: 10.1111/cea.13181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1985–1997. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Loland L, et al. Intermittent inhaled corticosteroids in infants with episodic wheezing. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1998–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnes P. Scientific rationale for inhaled combination therapy with long-acting β2-agonists and corticosteroids. Eur Respir J 2002; 19: 182–191. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00283202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Israel E, Reddel HK. Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 965–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1608969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dávila IJ. Clinical recommendations for the management of biological treatments in severe asthma patients: a consensus statement. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2021; 31: 36–43. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McGregor MC, Krings JG, Nair P, et al. Role of biologics in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 433–445. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1944CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pavord I, Busse W, Israel E, et al. Dupilumab treatment leads to clinical asthma remission in patients with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma with type 2 inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147: AB4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.FitzGerald JM, Emery P. Modifying the trajectory of asthma – are there lessons from the use of biologics in rheumatology? Lancet 2017; 389: 1082–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30600-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ajeganova S, Huizinga T. Sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis: latest evidence and clinical considerations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2017; 9: 249–262. doi: 10.1177/1759720X17720366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van den Toorn LM, Prins J-B, de Jongste JC, et al. Benefit from anti-inflammatory treatment during clinical remission of atopic asthma. Respir Med 2005; 99: 779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khatri S, Moore W, Gibson PG, et al. Assessment of the long-term safety of mepolizumab and durability of clinical response in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143: 1742–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moore WC, Kornmann O, Humbert M, et al. Stopping versus continuing long-term mepolizumab treatment in severe eosinophilic asthma (COMET study). Eur Respir J 2022; 59: 2100396. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00396-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng S-L. Immunologic pathophysiology and airway remodeling mechanism in severe asthma: focused on IgE-mediated pathways. Diagnostics 2021; 11: 83. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11010083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Austin CD, Gonzalez Edick M, Ferrando RE, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating effects of lebrikizumab on airway eosinophilic inflammation and remodelling in uncontrolled asthma (CLAVIER). Clin Exp Allergy 2020; 50: 1342–1351. doi: 10.1111/cea.13731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riccio AM, Dal Negro R, Micheletto C, et al. Omalizumab modulates bronchial reticular basement membrane thickness and eosinophil infiltration in severe persistent allergic asthma patients. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2012; 25: 475–484. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zastrzeżyńska W, Przybyszowski M, Bazan-Socha S, et al. Omalizumab may decrease the thickness of the reticular basement membrane and fibronectin deposit in the bronchial mucosa of severe allergic asthmatics. J Asthma 2020; 57: 468–477. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1585872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoshino M, Ohtawa J. Effects of adding omalizumab, an anti-immunoglobulin E antibody, on airway wall thickening in asthma. Respiration 2012; 83: 520–528. doi: 10.1159/000334701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mauri P, Riccio AM, Rossi R, et al. Proteomics of bronchial biopsies: galectin-3 as a predictive biomarker of airway remodelling modulation in omalizumab-treated severe asthma patients. Immunol Lett 2014; 162: 2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roth M, Zhao F, Zhong J, et al. Serum IgE induced airway smooth muscle cell remodeling is independent of allergens and is prevented by omalizumab. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0136549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riccio AM, Mauri P, De Ferrari L, et al. Galectin-3: an early predictive biomarker of modulation of airway remodeling in patients with severe asthma treated with omalizumab for 36 months. Clin Transl Allergy 2017; 7: 6. doi: 10.1186/s13601-017-0143-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Przybyszowski M, Paciorek K, Zastrzeżyńska W, et al. Influence of omalizumab therapy on airway remodeling assessed with high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) in severe allergic asthma patients. Adv Respir Med 2018; 86: 282–290. doi: 10.5603/ARM.a2018.0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 659–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31281-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hiles SA, McDonald VM, Guilhermino M, et al. Does maintenance azithromycin reduce asthma exacerbations? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1901381. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01381-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li S, Wang G, Wang C, et al. The REACH trial: a randomized controlled trial assessing the safety and effectiveness of the spiration valve system in the treatment of severe emphysema. Respiration 2019; 97: 416–427. doi: 10.1159/000494327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith D, Du Rand IA, Addy C, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for the use of long-term macrolides in adults with respiratory disease. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020; 7: e000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Serisier DJ. Risks of population antimicrobial resistance associated with chronic macrolide use for inflammatory airway diseases. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 262–274. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70038-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fricker M, Gibson PG, Powell H, et al. A sputum 6-gene signature predicts future exacerbations of poorly controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 144: 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hiles SA, Gibson PG, Agusti A, et al. Treatable traits that predict health status and treatment response in airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 9: 1255–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McDonald VM, Hiles SA, Godbout K, et al. Treatable traits can be identified in a severe asthma registry and predict future exacerbations. Respirology 2019; 24: 37–47. doi: 10.1111/resp.13389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McDonald VM, Simpson JL, Higgins I, et al. Multidimensional assessment of older people with asthma and COPD: clinical management and health status. Age Ageing 2011; 40: 42–49. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McDonald VM, Clark VL, Cordova-Rivera L, et al. Targeting treatable traits in severe asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901509. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01509-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McDonald VM, Fingleton J, Agusti A, et al. Treatable traits: a new paradigm for 21st century management of chronic airway diseases: Treatable Traits Down Under International Workshop report. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1802058. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02058-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Agusti A, Bel E, Thomas M, et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 410–419. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01359-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boulet L. Influence of comorbid conditions on asthma. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 897–906. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koh M, Irving L. The natural history of asthma from childhood to adulthood. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61: 1371–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang XY, Simpson JL, Powell H, et al. Full blood count parameters for the detection of asthma inflammatory phenotypes. Clin Exp Allergy 2014; 44: 1137–1145. doi: 10.1111/cea.12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, et al. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FeNO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184: 602–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-02583-2021.Shareable (425.7KB, pdf)