Abstract

Infection by Helicobacter pylori, a noninvasive bacterium, induces chronic leukocyte infiltration in the stomach by still largely unknown molecular mechanisms. We investigated the possibility that a membrane protein of H. pylori induces an inflammatory reaction in the subepithelial tissue of the stomach. By generating an expression library of H. pylori chromosomal DNA and screening with rabbit antiserum raised to a membrane fraction of H. pylori and sera of infected patients, we cloned a 16.0-kDa protein (HP-MP1) which appeared to attach to the inner membrane of the H. pylori in a homodimeric form. Anti-HP-MP1 antibodies were detected in the sera of infected patients but not in those of uninfected controls. Coincubation of monocytes with recombinant HP-MP1 led to cell activation and production of interleukin-1α (IL-1α), tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-8, and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α. The results indicate that HP-MP1 is an antigenic membrane-associated protein of H. pylori which potentially activates monocytes. This suggests that HP-MP1 may play roles in the pathogenesis of perpetual tissue inflammation associated with H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori is a curved, microaerophilic, gram-negative bacterium that was isolated in 1983 for the first time from the stomach biopsy specimens of patients with chronic gastritis (58). The infection persists for decades and is associated with virtually all cases of duodenal ulcer, most gastric ulcers, and the majority of primary B-cell lymphomas arising from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (5, 6, 14, 20). In certain regions of the world, a considerable population of infected subjects develop atrophic gastritis, a documented precursor lesion of gastric cancer (5, 6, 14, 20). H. pylori infection is likely to be involved in abnormal acid production in the infected stomachs (4, 18, 21, 30). Although the bacteria mostly colonize the gastric mucus and do not invade the basal membrane of the epithelium, the results of eradication therapy clearly indicate a direct relationship between bacterial load and severity of gastritis.

The molecular mechanisms of tissue damage caused by H. pylori infection are still largely unknown. H. pylori-associated gastritis is frequently characterized by chronic subepithelial infiltration by activated mononuclear cells and neutrophils (7, 17, 19, 42), which can be explained by the fact that H. pylori-infected gastric epithelium shows an increase in interleukin-8 (IL-8) production (9, 11, 26, 47). However, a recent report by Uemura et al. (53) showed a discrepancy in the level of IL-8 in gastric biopsy specimens and the grade of leukocyte infiltration in the corpus gastritis in H. pylori-infected patients. In addition, submucosal production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and IL-6 in infected patients has been reported (3, 9–11, 26, 40, 47). These cytokines are produced primarily by the activated monocytes, which are not the target cells of IL-8 and are not directly exposed to the gastric mucus containing H. pylori. Thus, these observations suggest alternative unknown mechanisms by which H. pylori might recruit inflammatory cells either by inducing unidentified cytokines secreted by the epithelial cells or by directly exerting biological effects by releasing soluble proteins (22, 31, 32) or shedding cell wall components which are translocated to the subepithelium like urease (32). Moreover, H. pylori infection associates with germinal-center formation, which requires the presence of an antigen in addition to the antigen-specific T and B cells and follicular dendritic cells. All this evidence suggests the subepithelial presence of bacterial products, which may function as chemoattractants and/or serve as antigens.

In this paper, we report a novel membrane-associated protein which not only serves as an antigen in infected patients but also has the potential to induce proinflammatory cytokine production by monocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth medium.

Type strains (ATCC 43629 and NCTC 11637) and two strains of H. pylori isolated from clinical sources (SR 7791, TN2) were used. These strains were grown under microaerobic conditions in brucella broth (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (25).

Antiserum to the membrane-associated protein of H. pylori.

H. pylori SR 7791 cells were sonicated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.15 M NaCl in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.5]) at 4°C and cleared of cellular debris by low-speed centrifugation (6,000 × g for 20 min). The membrane fraction was separated from the precipitate by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 20 min. The resulting pellet was then resuspended in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.6), emulsified with complete Freund’s adjuvant, and injected intradermally at multiple sites in three New Zealand White rabbits. Booster injections were given twice at 3-week intervals. The antibody titer in immunized rabbits was monitored by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the membrane fraction.

Preparation of outer and inner membrane fractions.

The above-mentioned membrane fraction of H. pylori was resuspended in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and washed three times with the same buffer. Total membranes were resuspended in 20 mM Tris–7 mM EDTA (pH 7.5) containing 2.0% sodium lauroyl sarcosine and incubated at room temperature for 30 min (13, 35). Inner membrane proteins were collected as sarcosyl-soluble fractions by centrifugation (40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C). The pellet (outer membrane) was washed three times with distilled water, resuspended in distilled water, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C until used.

Expression libraries and gene cloning.

Chromosomal DNA obtained from H. pylori SR 7791 was sonicated to random fragments, and the resulting fragments were electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel. Fragments in the 2- to 10-kb size range were extracted from the gel, treated with T4 DNA polymerase to produce blunt ends, and ligated to BamHI-NotI-EcoRI linkers (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The DNA fragments thus obtained were ligated to the EcoRI arms of ZAP II vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The library was screened first with the rabbit antiserum and then with pooled sera from patients with H. pylori infection.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

The nucleotide sequence of the cloned genes was determined by ABI Prism 310 Collect (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The nucleotide sequence thus determined was analyzed with a genetics software package (12). For database searches, sequence interpretation tools of BLAST (1), MOTIF (2, 39), PSORT (34), SOSUI at GenomeNet (Kyoto University), and COMPASS (Biomolecular Engineering Research Institute, Osaka, Japan) were used.

Recombinant HP-MP1, urease B, and chicken egg albumin (ovalbumin) proteins.

One of the cloned genes, designated HP-MP1, was subcloned into the His tag expression vector, pET28c(+) (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). Overexpression of HP-MP1 with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), treatment of the host cells [Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)], cell lysis with T7 lysozyme, and purification of protein were all done as described in the manufacturer’s protocol (38). The expression of the protein in the bacterial cells and the purity of the recombinant HP-MP1 were assessed by a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) method (29). After dialysis against PBS buffer, the purified protein was stored at −70°C.

A similar strategy was used to overexpress recombinant urease B and ovalbumin. First, a DNA fragment containing the entire coding region of the urease B gene was generated by PCR with genomic DNA from H. pylori NCTC 11637 as a template. The primers used for the amplification were 5′-GCAGCATATGAAAAAGATTAGCAGA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCCTAGAAAATGCTAAAGAG-3′ (antisense). Amplification with this sense primer generates a NdeI site at the N terminus of the amplified DNA. Amplification was carried out with the Takara LA PCR kit. The reaction conditions were as follows: denaturation at 96°C for 1 min, annealing at 42°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min (25 cycles). The amplified product was cloned into PCR II vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and sequenced with T7 and Sp6 primers (Novagen). The urease B gene thus obtained, containing NdeI and XhoI sites, was subcloned into the pET28c(+) vector. Next, a cDNA fragment containing the entire coding region of the ovalbumin gene was generated by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with RNA from chicken ovaries as a template. The primers used for the amplification were 5′-ACAACTCAGAGTTCCATATGGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGCTGGATCCTGATACTACAGTGCTCTG-3′ (antisense). Amplification with these sense and antisense primers generated an NdeI site and a BamHI site in the amplified DNA. Amplification was carried out with the Takara LA PCR kit. The reaction conditions were as follows: denaturation at 96°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min (25 cycles). The amplified product was cloned into PCR II vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced with T7 and Sp6 primers (Novagen). The ovalbumin gene thus obtained, containing NdeI and BamHI sites, was subcloned into the pET28c(+) vector. The purified HP-MP1, urease B, and ovalbumin used in these analyses contained <3.0 ng of endotoxin per ml by the Limulus amebocyte lysate inhibition assay (Whittaker Biologicals, Walkersville, Md.) (33, 44).

Antibodies to fusion proteins and Western blot analysis.

Purified fusion proteins of HP-MP1 and urease B were emulsified with complete Freund’s adjuvant and injected in the footpad of Sprague-Dawley rats. Booster injections were given twice at 3-week intervals. The antibody titer in immunized rats was monitored by ELISA with purified fusion proteins. HP-MP1 in bacterial cells was detected by Western blot analysis with the anti-HP-MP1 antibody and alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). The presence or absence of antibodies to HP-MP1 and urease B in patient sera was examined by Western blot analysis with recombinant HP-MP1, urease B proteins, biotin-labeled goat anti-human IgG, IgA, and IgM (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, Calif.), and alkaline phosphatase-labeled streptavidin (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, Ala.).

Immunoelectron microscopy.

H. pylori cells (SR 7791) were washed in PBS and fixed for 2 h at 4°C in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. The specimens were cryoprotected by a serial increase of sucrose concentrations (10, 15, 20, and 25%) in PBS, embedded in OCT compound (Miles Inc., Elkhart, Ind.), quick-frozen, and sectioned (2-μm-thick sections) in a cryostat. The frozen sections were mounted on slides, washed with 50 mM Tris buffer for 30 min, and incubated with PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin. The sections were incubated at 4°C for 24 h with either anti-HP-MP1 or anti-urease B polyclonal antibodies in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.005% saponin. After being washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.005% saponin, the sections were incubated for 24 h with 1 nM gold-conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody (Nanoprobes Inc., Stony Brook, N.Y.) at a final dilution of 1:50. After the sections were washed, the staining was enhanced with a silver enhancement kit (Nanoprobes Inc.) and postfixed by incubation in 0.2% OsO4 in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h at 4°C. After being washed in PBS, the sections were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol followed by propylene oxide, and embedded in Epon 812 (Nakalai tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Ultrathin sections were made with an LKB Ultrotome (LKB, Stockholm, Sweden) and examined with a 1200 EX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). No significant staining was detected in any sections treated with nonimmune rat serum or specific antisera preincubated with an excess amount of recombinant antigens.

Stimulation of monocytes.

Monocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors. In brief, mononuclear leukocytes were isolated by a density gradient sedimentation (Lymphoprep R; Nyegaard, Oslo, Norway) as described elsewhere (55). They were washed twice in PBS and suspended in RPMI medium (Life Technologies) containing 100 U of penicillin, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 10% autologous serum. They were then incubated at 37°C for 60 min in a plate precoated with autologous serum and collected after being washed twice in 5% EDTA containing 10% autologous serum. The purity of the monocytes was determined by morphology (>95% mononuclear phagocytes) and by staining surface markers (>90% CD14+, <2% CD3+) and esterase (>95% positive).

Monocytes were suspended (106/ml) in RPMI medium containing 10% autologous serum and incubated with PBS, H. pylori whole-cell sonicate, H. pylori culture supernatant (10%), brucella broth (10%), E. coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co.), recombinant urease B (50 μg/ml), recombinant HP-MP1 (50 μg/ml), or recombinant ovalbumin (50 μg/ml) for 6 h at 37°C in a 12-well plate (MS-8012R; Sumilon, Tokyo, Japan) pretreated for the culture of nonadherent cells. The viability of monocytes after an incubation was always more than 90% as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Flow-cytometric analysis.

Staining and analysis of surface antigens were performed as previously described (57). Monocytes (106) were incubated at 4°C for 20 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD19 and anti-CD3 to assess the contamination of B and T cells. After stimulation, the monocytes were washed twice in PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin. Activation of the viable monocytes was evaluated by the expression of the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) (CD25) (Chemicon International Inc.) and HLA-DR (Nichirei Inc., Tokyo, Japan) molecules with the gates set in the forward-side-scattergram in a population negative for propidium iodide staining. Antibodies to CD19 (Nichirei Inc.) and CD3 (Nichirei Inc.) were used to assess contamination of the monocyte preparation by B and T cells. Before being stained, the cells were treated with the culture supernatant of 2.4G2 cells (ATCC HBO-197) to prevent nonspecific binding of antibody to Fc receptors. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (EPICS XL; Coulter Electronics, Inc., Hialeah, Fla.).

Measurement of cytokines.

After 6 h of stimulation as described above, culture supernatants were collected. The concentrations of IL-1α, TNF-α, IL-8, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) released into the supernatants were determined with ELISA kits (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.).

Statistical analysis.

Data in the figures are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and the statistical significance was evaluated by Student’s t test.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the HP-MP1 gene has been deposited in the DDBJ under accession no. D30661.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of HP-MP1.

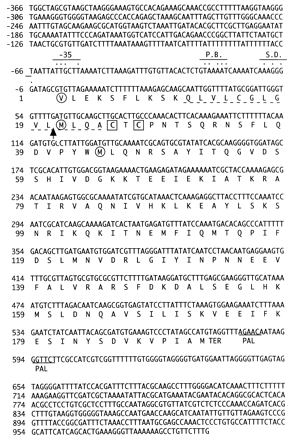

An expression library of H. pylori genomic DNA containing more than 106 PFU was screened with the rabbit antisera raised against the membrane fraction of H. pylori. The positive clones were further screened for reactivity to the sera of infected patients, which identified five clones unrelated to each other. One of those clones contained a gene of 579 nucleotides coding for a putative protein with a calculated molecular mass of 21.8 kDa (Fig. 1). This gene, designated HP-MP1 (H. pylori membrane protein 1), encoded a cluster of hydrophobic amino acid residues followed by two cysteine residues in its N terminus. This N-terminal region of 20 amino acids has features similar to those of most signal peptides (23, 24). It is composed of the amino-terminal subregion containing a positively charged residue (lysine at the fourth position), a highly hydrophobic central subregion, and a carboxyl-terminal subregion with three polar residues (cysteine at position 15 and glycine at positions 16 and 18). Particularly, the glycine residue at position 18 fits the so-called “(-3, -1) rule” of the carboxyl terminal of signal peptides (23, 24). Moreover, we sequenced 20 amino acid residues at the N terminus of the recombinant HP-MP1, which was designed to be translated from the first valine at position 1. We found that the N terminus of the recombinant HP-MP1 purified from the E. coli clone had methionine at position 21. From these data, we conclude that HP-MP1 has a putative cleavable site between positions 20 and 21 (Fig. 1). This structural feature is compatible with the molecular size determined by Western blot analysis and the properties of membrane proteins and has been corroborated by electron micrography (see below). In fact, a PSORT search of the deduced protein was compatible with its being either an inner or an outer membrane protein (outer membrane certainty = 0.790 [affirmative]; inner membrane certainty = 0.700) but not a periplasmic or cytoplasmic protein (both certainties = 0.000).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of HP-MP1. The genomic sequence spanning the region encoding HP-MP1 is shown. The amino acid sequence is shown below the nucleotide sequence in one-letter symbols. Dashed underlines depict a hydrophobic region. The arrow indicates a cleavage site. The consensus sequences, such as the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (S.D.) and the −10 (Pribnow box; P.B.) and −35 regions, are indicated by dots above the sequences. TER and PAL denote a termination codon and a palindromic sequence, respectively. Squares indicate two cystine residues. Circles indicate valine or methionine, which was used to create recombinant HP-MP1 (see Discussion).

The database search did not reveal any striking homology to other known sequences except for HP0596 (94.5% homology), which was classified as a hypothetical protein (51; H. pylori genome database [see the World Wide Web site at http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/hpdb/hpdb.html]).

Purification of the recombinant HP-MP1 and immunoblot analysis.

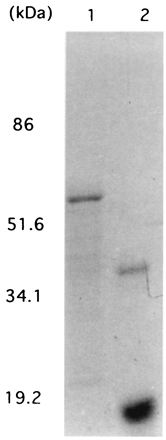

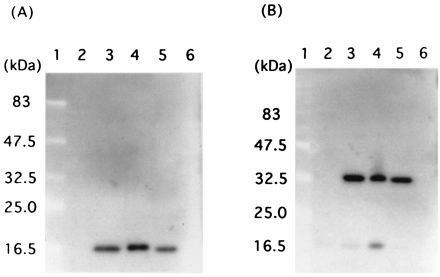

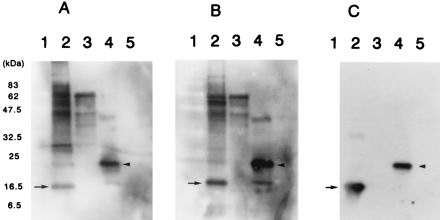

HP-MP1 translated from the first methionine at position 21 (Fig. 1) and urease B with a hexahistidine tag at the N amino acid terminus were overexpressed in an E. coli system (Fig. 2). Sequencing of the 22 amino acid residues at the N terminus of the recombinant proteins confirmed that both HP-MP1 and urease B were translated in the predicted reading frame. These proteins were purified to homogeneity and used to raise rat polyclonal antisera. These antisera were used in a Western blot analysis (Fig. 3). This analysis, with the anti-HP-MP1 antiserum, detected a discrete single band in all strains of H. pylori tested but not in Campylobacter jejuni or E. coli BL21(DE3), which was used as a host strain to express HP-MP1. Anti-HP-MP1 serum reacted with a 16.0-kDa polypeptide in whole lysates of H. pylori strains under reducing conditions (Fig. 3A), whereas preimmune sera failed to react with this protein (data not shown). Under nonreducing conditions, the rat antiserum recognized almost exclusively a 32.0-kDa polypeptide (Fig. 3B). The Western analysis also showed a size variation of HP-MP1 among the different strains of H. pylori (Fig. 3). Thus, these data indicate that HP-MP1 exists as a homodimeric form in H. pylori.

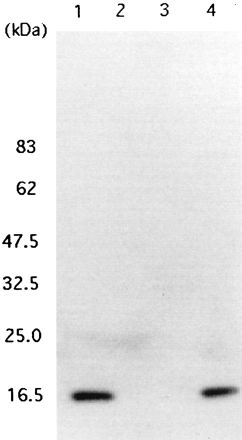

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of the recombinant HP-MP1 and urease B. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) under reducing conditions with 2-mercaptoethanol, and the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lanes: 1, urease B purified from a lysate of IPTG-treated E. coli BL21(DE3) containing an expression plasmid encoding urease B; 2, HP-MP1 purified from a lysate of IPTG-treated E. coli BL21(DE3) which harbors an expression plasmid encoding HP-MP1. Part of this purified HP-MP1 formed dimers because its reduction was incomplete.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of HP-MP1. Anti-HP-MP1 antiserum recognized a 16.0-kDa polypeptide in the lysates of whole cells of various H. pylori strains under reducing conditions with 2-mercaptoethanol (A) and a 32.0-kDa polypeptide under nonreducing conditions without 2-mercaptoethanol (B). Lanes: 1, molecular mass standards; 2, E. coli BL21(DE3); 3, H. pylori ATCC 43629; 4, H. pylori NCTC 11637; 5, H. pylori TN2 (a clinical isolate); 6, C. jejuni 542.

Localization of HP-MP1 in H. pylori.

We first examined whether HP-MP1 is secreted into the culture supernatant by Western blot analysis with specific antisera. HP-MP1 was detected only in the whole lysate (Fig. 4A), whereas urease B was detected both in the whole lysate and in the culture supernatant (Fig. 4B). This result led us to test whether HP-MP1 exists in the membrane fractions or nonsecretory cytosolic compartment of H. pylori.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of the culture supernatant and the whole-cell lysate of H. pylori NCTC 11637 for HP-MP1 and urease B. (A) Anti-HP-MP1 antiserum. (B) Rat antiserum to urease B. Lanes: 1, culture supernatant (concentrated fivefold); 2, whole-cell lysate. Both protein samples were prepared from the same batch of the sample.

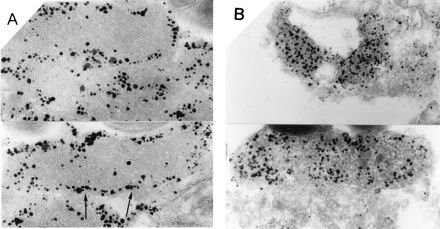

Next we prepared outer and inner membrane fractions of H. pylori and performed an immunoblot analysis. The immunoblot analysis with anti-HP-MP1 serum revealed a single band in the sarcosyl-soluble fraction, suggesting that HP-MP1 is present in the inner membrane fraction (Fig. 5). In addition, we investigated the localization of HP-MP1 by immunoelectron microscopy of sections of H. pylori NCTC 11637 cells. For comparison, localization of urease B was also studied. The immunogold particles specific to HP-MP1 appeared to line the inner membrane (Fig. 6A). Binding of these gold particles was inhibited by preincubation of anti-HP-MP1 serum with an excess of recombinant HP-MP1. In contrast, immunogold particles specific to urease B were distributed diffusely in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6B). Thus, HP-MP1 appears to be present in the inner membrane.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of the inner and outer membrane fractions of H. pylori NCTC 11637. Rat anti-HP-MP1 antiserum was used. Lanes: 1, whole-cell lysate; 2, cytosol fraction; 3, sarcosyl-insoluble (outer membrane) fraction; 4, sarcosyl-soluble (inner membrane) fraction.

FIG. 6.

Immunoelectron micrographs of a section of H. pylori cells with either anti-HP-MP1 or anti-urease B antiserum. (A) Localization of immunoreactive HP-MP1. Arrows show the cytoplasmic membrane. (B) Localization of immunoreactive urease B.

Detection of the antibodies to HP-MP1 in patient sera.

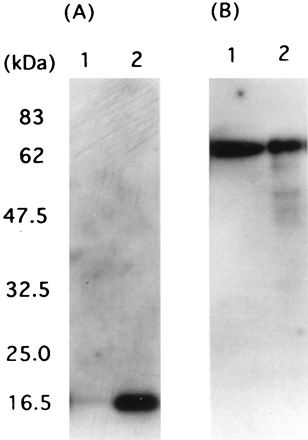

We used Western blot analysis to examine whether infected patients have antibodies to HP-MP1. The sera of H. pylori-infected patients bound to both the purified recombinant HP-MP1 (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 4) and native HP-MP1 (lanes 2) in a cell lysate of H. pylori, whereas uninfected controls failed to react with this protein (data not shown). The molecular weight of the recombinant protein in the blot was greater than that of the native form of HP-MP1, because of the addition of the hexahistidine tag to the recombinant antigen (Fig. 7C). Recombinant urease B antigen was also included as a control to demonstrate specificity in H. pylori-infected patients (lanes 3). Similar results were obtained with a total of 26 H. pylori-infected patient sera (only two representative cases are shown in Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis with anti-HP-MP1 antibody in patient sera and rat anti-HP-MP1 antibody. (A and B) The sera of two H. pylori-infected patients contain an antibody binding to the purified HP-MP1 fusion protein (arrowhead in lanes 4) and native HP-MP1 in a cell lysate of H. pylori strain (arrow in lanes 2). (C) Immunoblot with rat anti-HP-MP1 antibody identifies both native and fusion forms of HP-MP1. Lanes: 1, molecular mass standards; 2, cell lysate of H. pylori NCTC 11637; 3, purified urease B fusion protein; 4, purified HP-MP1 fusion protein; 5, purified ovalbumin fusion protein.

Cytokine production by monocytes stimulated with HP-MP1 and urease B.

Since urease B is known to activate monocytes in culture, we examined whether HP-MP1 has a similar effect. The peripheral blood monocytes were cultured in medium containing a sonicate of H. pylori NCTC 11637 (10 μg/ml), purified fusion proteins of urease B (50 μg/ml), HP-MP1 (50 μg/ml), and ovalbumin (50 μg/ml). HP-MP1 and urease B stimulated the expression of IL-2R (CD25) (Fig. 8a), which is usually expressed in monocytes only after they have been activated (56). This effect by HP-MP1 on CD25 expression was statistically significant (Fig. 8b). HP-MP1 and urease B also induced an increase in the expression of HLA-DR (data not shown), which is usually expressed at a low level on monocytes, and the expression is up-regulated by cell activation (49).

FIG. 8.

Effects of coincubation with medium containing HP-MP1 on cell activation of monocytes. (a) Flow-cytometric analysis of IL-2R (CD25) expression in monocytes. Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were incubated for 6 h with E. coli LPS, H. pylori NCTC 11637 sonicate, purified recombinant urease B, purified HP-MP1, and purified recombinant ovalbumin. The monocytes were stimulated with fusion proteins of HP-MP1 (A), urease B (B), ovalbumin (C), H. pylori sonicate (D), E. coli LPS (E), and PBS (F). After 6 h of incubation in the culture, monocytes in each culture were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled CD25 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative histograms of three consecutive experiments are shown. (b) Percentage of monocytes expressing CD25 in the indicated stimulation cultures. Results are mean and standard error of the mean of five experiments. An asterisk indicates a significant difference from the value obtained with PBS (P < 0.05 to P < 0.01).

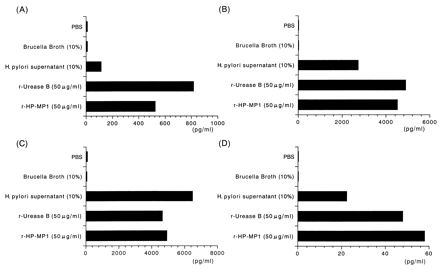

We next analyzed the cytokines produced by monocytes that had been exposed to HP-MP1 and urease B for 6 h (Fig. 9). Culture supernatant of H. pylori was most potent in the induction of IL-8 (Fig. 9C). However, in the induction of IL-1α, TNF-α, and MIP-1α, recombinant urease B and HP-MP1 were more potent than the culture supernatant.

FIG. 9.

Cytokine production by monocytes activated in medium containing HP-MP1. Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were incubated for 6 h with PBS, brucella broth, H. pylori supernatant, recombinant urease B (50 μg/ml), or HP-MP1 (50 μg/ml). The supernatant from each culture was collected to measure cytokines. IL-1α (A), TNF-α (B), IL-8 (C), and MIP-1α (D) were all measured by ELISA. The results shown are representative histograms of three experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized HP-MP1, a novel membrane protein of H. pylori which activates monocytes to secrete cytokines and is recognized as an antigen in the infected patients.

In whole bacterial lysate made from various H. pylori strains, HP-MP1 was detected as a 32.0- and 16.0-kDa polypeptide under nonreducing and reducing conditions, respectively (Fig. 3). This indicates that HP-MP1 exists as a homodimer in H. pylori. Since HP-MP1 has two cysteine residues (Fig. 1), they appear to be involved in dimer formation. Indeed, a deletion mutant of HP-MP1, which starts translation at the second methionine at position 44, did not form dimers (data not shown).

Although HP-MP1 has a cleavable hydrophobic region, the protein was not detected in culture supernatants of H. pylori (Fig. 4) but was detected in a sarcosyl-soluble (inner membrane) fraction (Fig. 5). In addition, the findings in the immunoelectron microscopy analysis were compatible with the notion that the cleaved protein still associates with the inner membrane. The envelope protein export or extracellular protein secretion of gram-negative bacteria is initiated by an insertion mechanism of the protein in either a Sec-dependent or Sec-independent manner. Then the signal peptides of membrane-anchored proteins are processed during translocation across the cytoplasmic membrane. One report proposed that signal peptides on presecretory proteins destined for secretion or for export to different membrane compartments in gram-negative bacteria are structurally distinct (48). However, there is experimental evidence showing that signal peptides on presecretory proteins destined for different locations can be exchanged without affecting the sorting process (27, 46, 52). The locations of putative cleavage sites and the moieties of amino acids in the signal peptide of HP-MP1 suggest some features common to monotopic membrane proteins (46a). Considering other findings in this paper, we postulate that the presence of unknown cofactor molecules and/or the lack of appropriate sorting signals in HP-MP1 may help retain HP-MP1 in the cytosolic membrane compartment. Thus, for the moment, we conclude that HP-MP1 exists as a homodimer on the inner membrane of H. pylori and that its function in H. pylori has not yet been determined.

Although urease is known to be present on the surface of H. pylori, we saw urease B exclusively in the cytosol in our electron microscopy study. This could be because the bacterial sample was taken from fresh log-phase cultures and washed extensively in PBS, which presumably led to the loss of urease adsorbed onto the cell surface (15, 45). Alternatively, the strain we used could be one of those recently described types which do not adsorb urease (28).

With regard to the tissue injury in the H. pylori-infected stomach, there is still some controversy about the mechanisms. H. pylori could release toxins, such as VacA, which have a vacuolating effect in vitro and in vivo (8, 41, 50). However, recent studies suggest involvement of mononuclear cells and phagocytes as effector cells mediating tissue damage. These cells are likely to be activated by cell-bound factors (11, 16, 32, 43), cell-free factors released into culture medium (3, 22, 54), or factors released only by sonication or extraction (37) of H. pylori. To date, very few molecules in H. pylori have been shown to activate monocytes and neutrophils (3, 22, 31, 32, 54). In fact, urease B has recently been shown to activate monocytes (22, 31, 32). Since a membrane component of gram-negative bacteria has a mitogenic effect on the mononuclear cells, we tested whether HP-MP1 could activate monocytes to produce cytokines. The fact that HP-MP1 induced more IL-1α, TNF-α, and MIP-1α than did culture supernatant indicates that HP-MP1 could trigger an inflammatory reaction in the gastric tissue, since these cytokines are important in both migration and activation of monocytes and neutrophils. Thus, the continuous presence of HP-MP1 in the tissue would induce a dysregulated production of these cytokines, which would lead to perpetual tissue inflammation.

The findings that HP-MP1 is specific to H. pylori and that only infected patients have anti-HP-MP1 antibody suggest two possibilities. First, since HP-MP1 synthesis is specific to H. pylori, the anti-HP-MP1 antibody can be used as a serological marker for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection and may provide new information about the association of this antibody with the disease type in the infected patients when used in combination with other serological markers. Second, although we show here the proinflammatory property of HP-MP1 in vitro, there is no direct evidence that a membrane-integrated protein of H. pylori can translocate to the submucosa and interact with host mononuclear phagocytic cells. The presence of anti-HP-MP1 antibody in the infected patients indicates that HP-MP1 was recognized by the subepithelial lymphoid tissue in the inflamed stomach or the intestine (gut-associated lymphoid tissue). We postulate that once H. pylori degrades and goes through a proteolytic process in the stomach, the relatively small molecular size of HP-MP1 facilitates this translocation through the intercellular canaliculi of the inflamed gastric epithelium, similarly to urease (32).

In summary, we have characterized a novel membrane protein of H. pylori and have shown evidence suggesting that not only secretory products of the bacteria but also a membrane product may be released. This product may translocate the epithelium and act as a proinflammatory mediator in the H. pylori-infected stomach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hisato Jingami (Protein Engineering Institute, Osaka, Japan) and Keiko Takemoto (Kyoto University Virus Institute) for sequence analysis, Kenich Imagawa (Otsuka Pharmaceutical) for measurement of the cytokine, Mitsuaki Nishibuchi (Kyoto University) for critical reading of the manuscript, and Naoko Sakanashi for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Japan; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS); and the Dr. Shimizu grant in Immunological Research for 1996.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bairoch A, Bucher P, Hofmann K. The PROSITE database, its status in 1997. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:217–221. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M, Walz A, Kunkel S L. Neutrophil-activating peptide-1/interleukin-8, a novel cytokine that activates neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1045–1049. doi: 10.1172/JCI114265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beales I L, Calam J. Helicobacter pylori infection and tumour necrosis factor-alpha increase gastrin release from human gastric antral fragments. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:773–777. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori and the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:626–633. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser M J. Gastric Campylobacter-like organisms, gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:371–383. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)91028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser M J, Parsonnet J. Parasitism by the “slow” bacterium Helicobacter pylori leads to altered gastric homeostasis and neoplasia. J Clin Investig. 1994;94:4–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI117336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cover T L, Reddy L Y, Blaser M J. Effects of ATPase inhibitors on the response of HeLa cells to Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1427–1431. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1427-1431.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabtree J E, Wyatt J I, Trejdosiewicz L K, Peichl P, Nichols P H, Ramsay N, Primrose J N, Lindley I J D. Interleukin-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori infected, normal, and neoplastic gastroduodenal mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:61–66. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crabtree J E, Shallcross T M, Heatley R V, Wyatt J I. Mucosal tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 in patients with Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis. Gut. 1991;32:1473–1477. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.12.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowe S E, Alvarez L, Dytoc M, Hunt R H, Muller M, Sherman P, Patel J, Jin T, Ernst P B. Expression of interleukin 8 and CD54 by human gastric epithelium after Helicobacter pylori infection in vitro. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doig P, Trust T J. Identification of surface-exposed outer membrane antigens of Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4526–4533. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4526-4533.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolley C P, Cohen H. The clinical significance of Campylobacter pylori. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:70–79. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn B E, Vakil N B, Schneider B G, Miller M M, Zitzer J B, Peutz T, Phadnis S H. Localization of Helicobacter pylori urease and heat shock protein in human gastric biopsies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1181–1188. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1181-1188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engstrand L, Scheynius A, Pahlson C, Grimelius L, Schwan A, Gustavsson S. Association of Campylobacter pylori with induced expression of class II transplantation antigens on gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1989;57:827–832. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.827-832.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genta R M, Hamner H W, Graham D Y. Gastric lymphoid follicles in Helicobacter pylori infection. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbons A H, Legon S, Walker M M, Ghatei M, Calam J. The effect of gastrin-releasing peptide on gastrin and somatostatin messenger RNAs in human infected with Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1940–1947. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodwin C S, Armstrong J A, Marshall B J. Campylobacter pyloridis, gastritis, and peptic ulceration. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:353–365. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham D Y. Campylobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:615–625. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(89)80057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutierrez O, Melo M, Segura A M, Angel A, Genta R M, Graham D Y. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection improves gastric acid secretion in patients with corpus gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:664–668. doi: 10.3109/00365529708996515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris P R, Mobley H L T, Perez-Perez G I, Blaser M J, Smith P D. Helicobacter pylori urease is a potent stimulus of mononuclear phagocyte activation and inflammatory cytokine production. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:419–425. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heijne G V. Topical review: the signal peptide. J Membr Biol. 1990;115:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01868635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heijne G V. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu L T, Mobley L T. Purification and N-terminal analysis of urease from Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1990;58:992–998. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.992-998.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J, O’Toole P W, Doig P, Trust T J. Stimulation of interleukin-8 production in epithelial cell lines by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1732–1738. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1732-1738.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson M E, Pratt J M, Stocker N G, Holland I B. An inner membrane protein N-terminal signal sequence is able to promote efficient localization of an outer membrane protein in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1985;4:2377–2383. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnamurthy P, Parlow M, Vakil N, Phadnis S H, Dunn B E. American Gastroenterological Association Digestive Disease Week. 1998. H. pylori urease can be exclusively cytoplasmic in vivo, abstr. A-642. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee A, Fox J, Hazell S. Pathogenicity of Helicobacter pylori: a perspective. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1601–1610. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1601-1610.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mai U E H, Perez-Perez G I, Allen J B, Wahl S M, Blaser M J, Smith P D. Surface proteins from Helicobacter pylori exhibit chemotactic activity for human leukocytes and are present in gastric mucosa. J Exp Med. 1992;175:517–525. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mai U E H, Perez-Perez G I, Whal L M, Whal S M, Blaser M J, Smith P D. Soluble surface proteins from Helicobacter pylori activate monocytes/macrophages by a lipopolysaccharide-independent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:894–900. doi: 10.1172/JCI115095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marra M N, Wilde C G, Griffith J E, Snable J L, Scott R W. Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein has endotoxin-neutralizing activity. J Immunol. 1990;144:662–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newell D G, McBride H, Pearson A D. The identification of outer membrane proteins and flagella of Campylobacter jejuni. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;130:1201–1208. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-5-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen H, Andersen L P. Activation of phagocytes by Helicobacter pylori correlates with the clinical presentation of the gastric infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:347–350. doi: 10.3109/00365549509032729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nielsen H, Andersen L P. Activation of human phagocyte oxidative metabolism by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1747–1753. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91430-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novagen, Inc. pET system manual. 6th ed. Madison, Wis: Novagen, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogiwara A, Uchiyama I, Takagi T, Kanehisa M. Construction and analysis of a profile library characterizing groups of structurally known proteins. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1991–1999. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oppenheim J J, Zachariae C O C, Mukaieda N, Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene intercrine cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papini E, Satin B, Bucci C, Bernard M D, Telford J L, Manetti R, Rappuoli R, Zerial M, Montecucco C. The small GTP binding protein rab7 is essential for cellular vacuolation induced by Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin. EMBO J. 1997;16:15–24. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paull G, Yardley J. Pathology of Campylobacter pylori-associated gastric and esophageal lesions. In: Blaser M J, editor. Campylobacter pylori in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. New York, N.Y: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1989. pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Perez G I, Shepherd V L, Morrow J D, Blaser M J. Activation of human THP-1 cells and rat bone marrow-derived macrophages by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1183–1187. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1183-1187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petsch D, Deckwer W D, Anspach F B. Proteinase K digestion of proteins improves detection of bacterial endotoxins by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay: application for endotoxin removal from cationic proteins. Anal Biochem. 1998;259:42–47. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phadnis S H, Parlow M H, Levy M, Ilver D, Caulkins C M, Connors J B, Dunn B E. Surface localization of Helicobacter pylori urease and heat shock protein homolog requires bacterial autolysis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:905–912. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.905-912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poquet I, Faucher D, Pugsley A P. Stable periplasmic secretion intermediate in the general secretory pathway of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1993;12:271–278. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46a.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma S A, Tummuru M R, Miller G G, Blaser M J. Interleukin-8 response of gastric epithelial cell lines to Helicobacter pylori stimulation in vitro. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1681–1687. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1681-1687.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sjöstrom M, Wold S, Wieslandr A, Rilfors L. Signal peptide amino acid sequences in Escherichia coli contain information related to final protein localization. A multivariate data analysis. EMBO J. 1987;6:823–831. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith P D, Lamerson C L, Wong H, Wahl L M, Wahl S M. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates human monocyte accessory cell function. J Immunol. 1990;144:3829–3834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telford J L, Ghiara P, Dell’Orco M, Comanducci M, Burroni D, Bugnoli M, Tecce M F, Censini S, Covacci A, Xiang Z, et al. Gene structure of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin and evidence of its key role in gastric disease. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1653–1658. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tommassen J, van Tol H, Lugtenberg B. The ultimate location of an outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli K-12 is not determined by the signal sequence. EMBO J. 1983;2:1275–1279. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uemura N, Oomoto Y, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Sumii K, Haruma K, Kajiyama G. Gastric corpus IL-8 concentration and neutrophil infiltration in duodenal ulcer patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:793–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vans D J, Jr, Evans D G, Takemura T, Nakano H, Lampert H C, Graham D Y, Granger D N, Kvietys P R. Characterization of a Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2213–2220. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2213-2220.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wahl L M, Smith P D. Isolation of macrophages/monocytes from human peripheral blood and tissues. In: Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Marguilies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1991. pp. 7.6.1–7.6.8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wahl S M, McCartney-Francis N, Hunt D A, Smith P D, Wahl L M, Katona I M. Monocyte interleukin-2 receptor gene expression and interleukin-2 augmentation of microbicidal activity. J Immunol. 1987;139:1342–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakatsuki Y, Neurath N F, Max E E, Strober W. The B cell specific transcription factor BSAP regulates B cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1099–1108. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Warren J R, Marshall B J. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;i:1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]