Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a human pathogen and one of the leading causes of food poisoning in Europe and the United States. The outside of the bacterium is coated with a capsular polysaccharide that assists in the evasion of the host immune system. Many of the serotyped strains of C. jejuni contain a 6-deoxy-heptose moiety that is biosynthesized from GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose by the successive actions of a 4,6-dehydratase, a C3/C5-epimerase, and a C4-reductase. We identified 18 different C3/C5 epimerases that could be clustered together into three groups at a sequence identity of >89%. Four of the enzymes from the largest cluster (from serotypes HS:3, HS:10, HS:23/36, and HS:41) were shown to only catalyze the epimerization at C3. Three enzymes from the second largest cluster (HS:2, HS:15, and HS:42) were shown to catalyze the epimerization at C3 and C5. Enzymes from the third cluster were not characterized. The three-dimensional structures of the epimerases from serotypes HS:3, HS:23/36, HS:15, and HS:41 were determined to resolutions of 1.5 – 1.9 Å. The overall subunit architecture places these enzymes into the diverse “cupin” superfamily. Within X-ray coordinate error, the immediate regions surrounding the active sites are identical suggesting that factors extending farther out may influence product outcome. The X-ray crystal structures are consistent with His-67 and Tyr-134 acting as general acid/base catalysts for the epimerization of C3 and/or C5. Two amino acid changes (A76V/C136L) were enough to convert the C3-epimerase from serotype HS:3 to one that could now catalyze the epimerization at both C3 and C5.

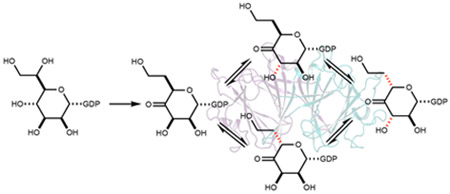

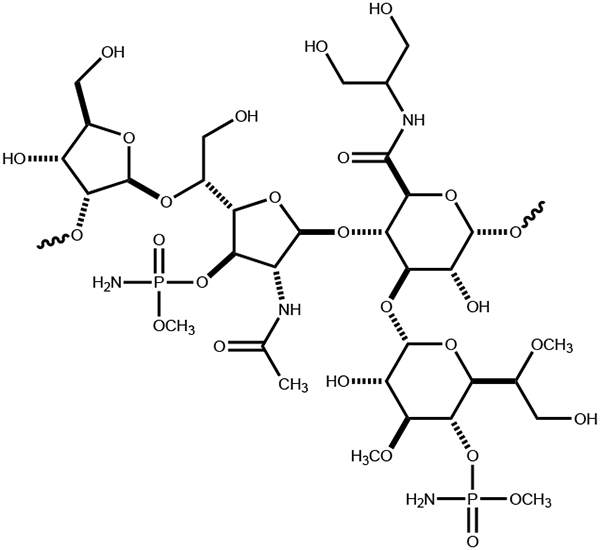

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Campylobacter jejuni is a Gram-negative pathogenic bacterium commonly found in chickens and cattle, and is the leading cause of food poisoning in North America and Europe (1-2). C. jejuni has shown high adaptability, antibiotic resistance, and an ability to evade the host immune response (2). Like many enteric bacteria, the various strains of C. jejuni produce different carbohydrate-based lipooligosaccharides (LOS) and capsular polysaccharides (CPS). These polysaccharides are essential for the structural integrity and maintenance of the bacterial cell wall (3-4). Deletion of the polysaccharide synthesis genes drastically decreases the pathogenicity of C. jejuni (5). Thus, the enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of these polysaccharides are potential therapeutic targets (5).

The capsular polysaccharides from C. jejuni are composed of repeating units of monosaccharides attached to one another via glycosidic bonds. Perhaps the most well-characterized example comes from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (serotype HS:2). This CPS consists of a repeating series of d-ribose, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, d-glucuronate, and d-glycero-l-gluco-heptose sugars as shown in Scheme 1 (6). There are at least 12 known CPS structures identified to date, and nine of these contain either a heptose or 6-deoxy-heptose moiety (7). A total of ten different heptose variations has been structurally characterized within the known serotypes of C. jejuni (Scheme 2), and it is currently thought that all the heptose variations originate from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (8-10).

Scheme 1:

Structure of the repeating polysaccharide unit in the CPS from C. jejuni NCTC 11168.

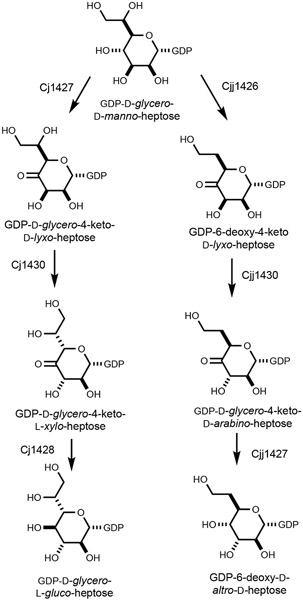

Scheme 2:

Structures of heptoses previously identified in the capsular polysaccharides of C. jejuni (7).

Of the ten heptose sugars shown in Scheme 2, the biosynthetic pathways for only two of them have been functionally characterized. The Creuzenet laboratory has shown that GDP-6-deoxy-α-d-altro-heptose from the HS:23/36 serotype is synthesized from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose via the combined action of a 4,6-dehydratase, a C3-epimerase, and a C4-reductase (10-12). We have demonstrated that GDP-d-glycero-β-l-gluco-heptose from the HS:2 serotype can be synthesized via the combined activities of a C4-dehydrogenase, a C3/C5-epimerase and a C4-reductase (13-15). These two pathways are summarized in Scheme 3. At C3 and C5, there are four possible stereochemical combinations, and all four have been identified in the ten heptoses examined to date. It is apparent that an epimerase is responsible for the racemization of the stereochemistry at C3 and/or C5 after oxidation of C4, but it is not clear as to whether the ultimate stereochemistry of the heptose is dictated by the substrate profile for the C4-reductase.

Scheme 3.

Biosynthetic pathways for the formation of GDP-d-glycero-l-gluco-heptose from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (13-15) and GDP-6-deoxy-d-altro-d-heptose from C. jejuni 81-176 (10-12).

Here we have purified and functionally characterized seven different C3/C5 epimerases from various strains of C. jejuni. Three of them were found to epimerize C3 and C5, while four of them were found to epimerize only C3. The three-dimensional structures for four of these enzymes were determined to high resolution. Two mutations to the C3-only group of epimerases conferred the ability to epimerize both C3 and C5.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Lysogeny broth (LB) medium, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and NADPH were purchased from Research Products International. The protease inhibitor cocktail, lysozyme, kanamycin, imidazole, Tris, and HEPES were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Ammonium bicarbonate, 2-mercaptoethanol, KCl, and MgCl2 were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. DNase I was purchased from Roche. HisTrap columns and Vivaspin 20 spin filters were obtained from Cytiva. The 3 kDa Nanosep spin filters were purchased from Pall Corporation (Port Washington, NY). Deuterium oxide was acquired from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. Oligonucleotide primers were bought from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reagents, pfu polymerase, pfu polymerase buffers, Escherichia coli XL1 Blue and BL21 (DE3) strains were purchased from New England Biolabs. The kit for isolation of DNA was obtained from Qiagen.

Equipment.

Ultraviolet spectra were collected on a SpectraMax 340 (Molecular Devices) ultraviolet-visible plate reader using 96-well Greiner plates. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz system equipped with a broadband probe and sample changer. Mass spectrometry data were collected on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Focus system run in negative ion mode.

Sequence Similarity Network Analysis of Epimerases.

The FASTA protein sequence for Cj1430 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (serotype HS:2) was used as the initial BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) query in the EFI-EST database (Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool, https://efi.igb.illinois.edu/efi-est/) (16). The sequence similarity networks (SSN) were generated by submitting the FASTA sequences to the EFI-EST webtool. All network layouts were created and visualized using Cytoscape 3.8.2 (17).

Homologues to Cj1430 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168.

The DNA for the expression of the genes homologous to Cj1430 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 were chemically synthesized and codon optimized from either Twist Biosciences (San Francisco, CA) or GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). These genes included those from serotypes HS:2 (UniProt entry: Q0P8I4), HS:3 (UniProt entry: F2X702), HS:10 (UniProt entry: F2X784), HS:15 (UniProt entry: A0A3Z9HSX9), HS:23/36 (UniProt entry: Q6EF58), HS:41 (UniProt entry: Q5M6T7), and HS:42 (UniProt entry: F2X7E5). The DNA was inserted between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of a pET-28a (+) expression vector. The gene constructs encode for the expression of an N-terminal His6-affinity tag and the complete amino acid sequences of the seven proteins purified for this investigation are shown in Figure S1.

Homologues to Cj1428 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168.

The DNA for the expression of the genes homologous to that for Cj1428 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2) were chemically synthesized and codon optimized from either Twist Biosciences or GenScript. These genes included those from HS:2 (UniProt entry: Q0P8I6), HS:3 (UniProt entry: F2X701), and HS:15 (UniProt entry: F2X7A6). The DNA was inserted between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of a pET-28a (+) expression vector. The gene constructs encode for the expression of an N-terminal His6-affinity tag and the complete amino acid sequences of the three proteins purified for this investigation are presented in Figure S2.

Protein Expression and Purification.

The wild-type epimerases from the HS:2, HS:3, HS:10, HS:15, HS:23/36, HS:41 and HS:42 serotypes, in addition to the variants made from the HS:3 and HS:15 serotypes, were purified according to the procedure reported previously (15). Similarly, the wild-type C4-reductases from serotypes HS:2, HS:3 and HS:15 were expressed and purified according to a published procedure (15). E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells were transformed by the appropriate plasmids. Single colonies were inoculated in 50 mL of LB medium (20 g/L yeast extract, 35 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L sodium chloride, pH 7.0) supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and grown at 37 °C with shaking. The starter cultures were used to inoculate 1 L of LB medium, grown at 37 °C with shaking to an OD600 of ~0.8. Expression was induced by the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1.0 mM. The cultures were subsequently incubated for 18 h at 15 °C, with shaking at 140 rpm. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C.

Purification of the seven epimerases was conducted at 22 °C. In a typical purification, ~5 g of frozen cell paste were resuspended in 50 mL buffer A (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 5.0 mM imidazole) supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL lysozyme, 0.05 mg/mL protease inhibitor cocktail powder, 40 U/mL DNase I, and 10 mM MgCl2. The suspended cells were lysed by sonication (Branson 450 Sonifier) and the supernatant solution was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 30 min. The supernatant solution was loaded onto a prepacked 5-mL HisTrap column and eluted with a linear gradient of buffer B (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 500 mM imidazole). Fractions containing the desired protein, as identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), were combined, and concentrated in a 20-mL spin filter with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff. The imidazole was removed from the protein by dialysis using buffer C (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl). The protein was concentrated to 5-10 mg/mL, aliquoted, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C. Typical yields of 20-30 mg were obtained from 1 L of culture.

Determination of Protein Concentration.

Concentrations of the proteins were determined spectrophotometrically using computationally derived molar absorption coefficients at 280 nm (18). The values of ε280 (M−1 cm−1) used for the epimerases from serotypes HS:2, HS:3, HS:10, HS:15, HS:23/36, HS:41, and HS:42 are 41,370, 34,380, 35,870, 39,880, 34,380, 34,380, and 39,880, respectively.

Mutagenesis of the Epimerase from Serotype HS:3.

Mutations were made to the C3-epimerase from serotype HS:3 in an attempt to alter the reaction specificity to match that of the C3/C5-epimerase from HS:2. This was done by changing the conserved residues found at specific locations within the HS:3 serotype for those found in the epimerase from the HS:2 serotype. All site-directed amino acid changes were constructed using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit from Qiagen. Three single-site variants (A76V, C136L, and E128K), two double-site variations (A76V/C136L and E128K/T129E), and one triple-site substitution (A76V/A122S/C136L) of the epimerase from serotype HS:3 were prepared. For the A76V, C136L, and E128K single-site variants, the gene for the wild-type epimerase from HS:3 was used as the template. For the A76V/C136L and E128K/T129E variants, the genes from A76V and E128K, respectively, were used as the initial template. For the A76V/A122S/C136L modification, the gene for A76V/C136L was used as the template. Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were conducted to amplify the genes using a PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eton Bioscience Inc).

One 10-site variant (A39Y/V40L/D41S/L44V/N46D/L48I/I51K/H57N/K59H/H60F) and one 11-site variant (H100W/R102K/N106S/Q107Y/D108K/K111Q/I112L/V115L/A117P/G118N/F119M) of the epimerase from serotype HS:3 were also constructed. The DNA for the expression of these genes were chemically synthesized and codon optimized by GenScript. The DNA was inserted between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of a pET-28a (+) expression vector. The genes enable the expression of an N-terminal His6-affinity tag and the complete amino acid sequences of the eight variants are provided in Figure S3.

Mutation of His67 and Tyr134 from the Epimerases from Serotypes HS:3 and HS:15.

Mutation of the two putative general acid/base catalysts in the active site of the epimerases from the HS:3 and HS:15 serotypes was completed. Two single-site variants (H67N and Y134F) of each epimerase were prepared. The DNA for the H67N and Y134F of the epimerase from HS:3 and HS:15, respectively, were chemically synthesized and codon optimized from Twist Biosciences. The DNA for the Y134F and H67N variants of the epimerase from serotypes HS:3 and HS:15, respectively, were constructed using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit from Qiagen and the genes for the wild-type epimerases as the template. Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were conducted to amplify the genes using a PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eton Bioscience Inc). The DNA was inserted between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites of a pET-28a (+) expression vector. The genes enable the expression of an N-terminal His6-affinity tag and the complete amino acid sequences of the four variants are provided in Figure S4.

Determination of Kinetic Constants.

The kinetic constants for the reaction catalyzed by the various epimerases were determined using a coupled enzyme assay with the appropriate C4-reductase by monitoring the oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ at 340 nm. GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) was obtained by incubation of 4.0 mM GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) with 5.0 μM GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose 4,6-dehydratase from C. jejuni 81-176 (HS:23/36) in buffer D (50 mM HEPES/K+, pH 7.5) for 2 h at 20 °C. The dehydratase was removed using a 3 kDa molecular weight cutoff spin filter. For the determination of the kinetic constants, the concentration of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) was varied between 10 μM and 2.5 mM. The assays were carried out in a total reaction volume of 250 μL with 100 nM epimerase, 20 μM C4-reductase, and 300 μM NADPH in buffer D at 25 °C. The apparent values of kcat and kcat/Km were determined by fitting the initial velocity data to eq 1 using SigmaPlot 11.0, where ν is the initial velocity of the reaction, Et is the enzyme concentration, S is the substrate concentration, kcat is the turnover number, and Km is the Michaelis constant.

| (1) |

Crystallization and Structural Analyses.

For protein crystallization trials the enzymes were dialyzed against 200 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and then concentrated between 24 to 40 mg/mL depending upon the specific enzyme under investigation. Crystallization conditions were surveyed by the hanging drop method of vapor diffusion (in the presence and absence of 5.0 mM GDP) using a sparse matrix screen developed in the Holden laboratory. Both the N-terminally histidine-tagged enzymes and tag-free enzymes from serotypes HS:3 and HS:15 were tested for crystallization properties. The enzymes from serotypes HS:23/36 and HS:42 were additionally screened using a construct with a C-terminal histidine tag.

Epimerase from Serotype HS:3.

Crystals of the tag-free enzyme at 40 mg/mL and 5.0 mM GDP were grown at room temperature from 10-12% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 0.75 M tetramethylammonium chloride, and 100 mM homopiperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) at pH 5.0. For X-ray data collection, the crystals were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution composed of 20% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 1.0 M tetramethylammonium chloride, 300 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM GDP, 10% ethylene glycol, and 100 mM homopiperazine-1,4-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) at pH 5.0.

Epimerase from Serotype HS:23/36.

Crystals of the C-terminally tagged enzyme at 25 mg/mL and with 5.0 mM GDP were grown at room temperature from 18-20% poly(ethylene glycol) 3350, 200 mM KCl, and 100 mM 3-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]propane-1-sulfonic acid at pH 8.0. For X-ray data collection, they were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution composed of 28% poly(ethylene glycol) 3350, 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 5.0 mM GDP, 18% ethylene glycol, and 100 mM 3-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]propane-1-sulfonic acid at pH 8.0.

Epimerase from Serotype HS:15.

Crystals of the tag-free enzyme at 24 mg/mL and with 5.0 mM GDP were grown at room temperature from 26-28% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000 and 100 mM 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid at pH 7.0. For X-ray data collection , the crystals were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution composed of 31% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 300 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM GDP, 5% ethylene glycol, and 100 mM 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid at pH 7.0.

Epimerase from Serotype HS:42.

Crystals of the tag-free enzyme at 25 mg/mL and with 5.0 mM GDP were grown at room temperature from 7-12% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 200 mM KCl, and 100 mM 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid at pH 7.0. For X-ray data collection, they were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution composed of 25% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 5.0 mM GDP, 18% ethylene glycol, and 100 mM 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid at pH 7.0.

X-ray data were collected at 100 K utilizing a BRUKER D8-VENTURE sealed tube system equipped with Helios optics and a PHOTON II detector. These X-ray data were processed with SAINT and scaled with SADABS (Bruker AXS). All structures were solved via molecular replacement with the software package PHASER and using the structure of Cj1430 from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2) (PDB entry 7M14) as the search probe (15,19). The models were refined by iterative cycles of model building in COOT (20-21) and refinement with REFMAC (22). X-ray data collection and refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

X-ray Data Collection Statistics and Model Refinement Statistics

| PDB code | 8DAK | 8DCL | 8DB5 | 8DCO |

| C. jejuni serotype | HS:3 | HS:23/36 | HS:15 | HS:42 |

| Space group | P212121 | P1 | P21 | P41212 |

| Unit cell a, b, c, (Å) α ,β, γ (º) | 61.5, 67.9, 96.1 90, 90, 90 | 39.8, 44.8, 57.4 83.3, 79.4, 65.1 | 41.5,154.5,120.5 90, 91.3, 90 | 73.7, 73.7, 152.3 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 50.0-1.5 (1.6 – 1.5)b | 50.0-1.55 (1.65 – 1.55)b | 50.0-1.9 (1.95 – 1.9)b | 50.0-1.9 (1.95 – 1.9)b |

| Number of independent reflections | 63904 (10456) | 48120 (7423) | 118325 (8051) | 33405 (2225) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.5 (89.6) | 93.9 (85.0) | 99.3 (96.9) | 98.7 (96.5) |

| Redundancy | 5.7 (2.7) | 3.5 (1.9) | 4.5 (2.8) | 9.6 (5.5) |

| avg I/avg σ(I) | 11.4 (2.8) | 15.5 (3.6) | 9.3 (2.5) | 17.6 (3.4) |

| Rsym (%)a | 9.4 (36.9) | 4.9 (25.8) | 8.1 (38.9) | 5.4 (33.5) |

| cR-factor (overall)%/no. reflections | 19.3/63904 | 16.7/48120 | 19.1/118325 | 20.7/33405 |

| R-factor (working)%/no. reflections | 19.2/60748 | 16.5/45672 | 18.9/112415 | 20.4/31665 |

| R-factor (free)%/no. reflections | 21.9/3156 | 20.0/2448 | 23.6/5910 | 25.4/1740 |

| number of protein atoms | 2909 | 2965 | 11666 | 2975 |

| number of heteroatoms | 589 | 470 | 1276 | 345 |

| Average B values | ||||

| protein atoms (Å2) | 8.9 | 16.0 | 15.5 | 24.8 |

| ligand (Å2) | 9.7 | 25.4 | 20.5 | 26.5 |

| solvent (Å2) | 21.3 | 27.9 | 21.5 | 29.2 |

| Weighted RMS deviations from ideality | ||||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| bond angles (º) | 1.60 | 1.76 | 1.61 | 1.66 |

| planar groups (Å) | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Ramachandran regions (%)d | ||||

| most favored | 99.1 | 99.2 | 97.5 | 97.2 |

| additionally allowed | 0.9 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| generously allowed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

.

Statistics for the highest resolution bin.

R-factor = (Σ∣Fo - Fc∣ / Σ∣Fo∣) x 100 where Fo is the observed structure-factor amplitude and Fc. is the calculated structure-factor amplitude.

Distribution of Ramachandran angles according to PROCHECK (23).

Results and Discussion

Bioinformatic Analysis of the C3/C5-Epimerases.

To better understand the sequence diversity within the C3/C5-epimerases responsible for the synthesis of the stereochemical modifications to the heptose moieties of the CPS from C. jejuni, a bioinformatic analysis was conducted. The amino acid sequence of the epimerase from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (serotype HS:2) was used as the initial BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) query in the EFI-EST database for the closest 1000 sequences. The sequence similarity network (SSN) was constructed at a sequence identity of 60% and is presented in Figure 1a. The epimerase from serotype HS:2 is shown in yellow and the epimerases from the other serotyped strains of C. jejuni are shown in green. To gain deeper insight into the sequence differences for the specific epimerases from serotyped strains of C. jejuni, we retrieved the complete FASTA protein sequences of the epimerases for the 18 serotyped strains of C. jejuni from UniProt and compiled them into a local custom database. The SSN shows that at a cutoff of 89% the epimerases form three separate groups (Figure 1b). The largest group contains 10 sequences and includes those from serotypes HS:23/36 and HS:3. The second most populated group contains the epimerases from HS:2 and HS:15. The third group from the HS:5, HS:11, and HS:45 serotypes are likely required for the biosynthesis of 3,6-dideoxy heptoses. A sequence identity matrix for all 18 enzyme is provided in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Sequence similarity networks (SSN) for the Cj1430-like epimerases from C. jejuni. (A) The closest 1000 sequences to Cj1430 from the HS:2 serotype at a sequence identity cutoff of 60%. The initial target protein from serotype HS:2 is shown in yellow and the related epimerases from the other serotyped strains of C. jejuni are shown in green. (B) SSN for the epimerases from 18 serotyped strains of C. jejuni at a sequence identity of 89%. The specific serotype is labeled in each circle. Yellow and green colors represent the C3/C5- and C3-epimerases that were tested for catalytic activity, whereas the gray color represent epimerases that have not been tested for catalytic activity.

Isolation and Characterization of Seven Epimerases.

We purified the epimerases from seven different strains of C. jejuni including those from serotypes HS:2, HS:3, HS:10, HS:15, HS:23/36, HS:41, and HS:42. The epimerases were produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) with a 21-residue His6-containing affinity tag appended to the N-terminus. The proteins were isolated using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography.

Isolation of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2).

The enzyme-catalyzed formation of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) involves the transient oxidation/dehydration/reduction of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) (24). To prepare sufficient quantities of the appropriate substrate for the various epimerases, GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) was incubated with GMH dehydratase from serotype HS:23/36 to enzymatically synthesize GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) in high yield (~95%). The 1H NMR spectrum of (1) is presented in Figure S5a, and the isolated dehydrated product (2) is presented in Figure S5b.

Reactions Catalyzed by the Epimerases from Various Strains of C. jejuni.

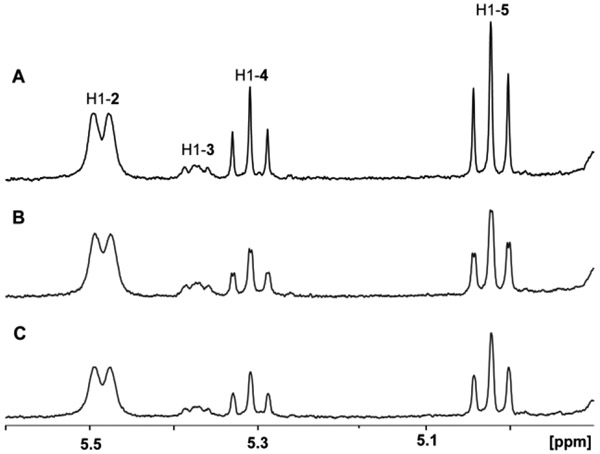

The reaction profiles for the C3/C5 epimerases from seven different strains of C. jejuni (serotypes HS:2, HS:3, HS:10, HS:15, HS:23/36, HS:41, and HS:42) were determined using the enzymatically-prepared GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) as the substrate. When 2 was incubated with the epimerase from serotypes HS:2, HS:15, or HS:42, three new resonances were detected between 4.5 and 6.0 ppm in the region expected for the anomeric hydrogen of C1 (Figure 2). There are two new triplets at 5.02 ppm and 5.31 ppm, and an unresolved doublet of doublets at 5.37 ppm. However, when substrate 2 was incubated with any of the epimerases from serotypes HS:3, HS:10, HS:23/36, or HS:41, only one new resonance appeared at 5.37 ppm (Figure 3). These results clearly indicate that each of the two sets of epimerases with sequence identities to one another of >89% in the SSN (Figure 1b and Table S1) have distinct product outcomes.

Figure 2.

1H NMR 400 MHz spectra of products formed from GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) after the addition of the C3/C5-epimerases from serotypes HS:2, HS:15, or HS:42. Reaction products include GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-arabino-heptose (3), GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-ribo-heptose (4) and GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-xylo-heptose (5) formed by the catalytic activity of epimerases from serotype HS:2 (A), HS:15 (B) or HS:42 (C). In these experiments 4.0 μM of the epimerase was incubated with 4.0 mM of compound 2 for 30 min prior to the acquisition of the NMR spectrum of the products.

Figure 3.

1H NMR 400 MHz spectra of product formed from GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) by the addition of C3-epimerases from serotype HS:3, HS:10, HS:23/36, or HS:41. The sole reaction product is GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-arabino-heptose (3) formed by the catalytic activity of epimerases from HS:3 (A), HS:10 (B), HS:23/36 (C), or HS:41 (D). In these experiments 4.0 μM of the epimerase was incubated with 4.0 mM of compound 2 for 30 min prior to the acquisition of the NMR spectrum of the products.

The likely reaction products that can be formed by any one of the seven epimerases tested are highlighted in Scheme 4. The sole epimerization at C3 or C5 will generate GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-arabino-heptose (3) or GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-ribo-heptose (4), respectively, whereas the double epimerization at C3 and C5 will form GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-xylo-heptose (5). It has previously been shown that the doublet of doublets at 5.37 ppm originates from the C3-isomerized product 3 and that the C5-isomerized product 4 resonates at 5.31 ppm (15). The C3/C5-isomerized product resonates at 5.02 ppm (15).

Scheme 4:

Potential reaction products from the epimerization of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) catalyzed by the various C3/C5-epimerases from C. jejuni.

Determination of Equilibrium Constants.

The equilibrium constants for the epimerase-catalyzed reactions were determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy. The relative concentrations at equilibrium for compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5 were determined by integration of the NMR signals for the hydrogen at C1 (Figure 2). The percentages of each product at equilibrium were calculated to be 41, 9, 18, and 32 for compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. The equilibrium constants from the product ratios for [3]/[2], [4]/[2], [5]/[3], and [5]/[4] are 0.22, 0.44, 3.6, and 1.8, respectively.

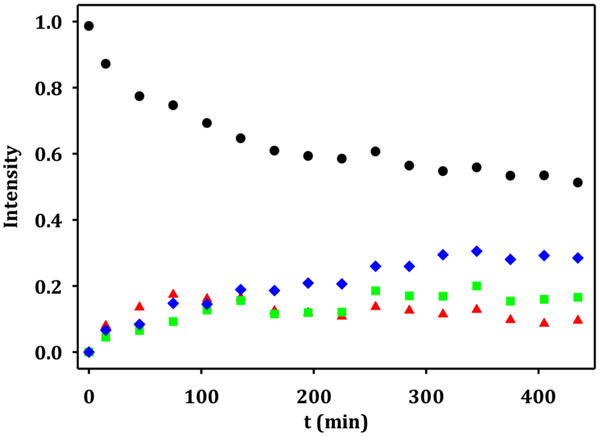

Relative Reaction Rates.

The reaction for the epimerization of C3 and C5 was followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy as function of time. The substrate, GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2), was incubated with 40 nM of the Cj1430 epimerase from C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2) and the time course for the formation of the reaction products 3, 4, and 5 was monitored over a period of 450 min at pD 7.5 (Figures 4 and 5). The relative concentrations of 2, 3, 4, and 5, were determined by integration of the NMR signals for the hydrogen at C1. The relative concentration of the substrate 2 decreases as a function of time and eventually reaches a plateau. At the earliest reaction times, the relative concentration of 3, the C3-epimerized product, exceeded that of 4, the C5-epimerized product. At later reaction times the absolute concentration of 3 decreased relative to the other reaction products 4 and 5. These results suggests that the epimerization of C3 is initially faster than the epimerization of C5.

Figure 4.

1H NMR 400 MHz spectra of products formed from GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) after the addition of the epimerase from serotype HS:2 as a function of time. (A) Control reaction in absence of enzyme, (B) 15 min, (C) 45 min, (D) 75 min, (E) 105 min, and (F) 135 min. Relative integration values for shaded peaks are shown in parentheses.

Figure 5.

Time course for the formation of reaction products from GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) after the addition of the Cj1430 epimerase from serotype HS:2. GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2), black circle; GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-arabino-heptose (3), red triangle; GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-ribo-heptose (4), green square; and GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-xylo-heptose (5), blue diamond.

Catalytic Activity of the Epimerases from Serotypes HS:3 and HS:15.

The catalytic activities of two epimerases were determined using a coupled enzyme assay with the appropriate C4-reductase by monitoring the oxidation of NADPH as a function of time. To obtain the catalytic activity of the epimerases from serotypes HS:3 and HS:15, the C4-reductases from serotypes HS:3 (locus_tag HS3.14) and HS:15 (locus_tag HS15.12) were used. The assays were carried out at pH 7.5 and 25 °C. The kinetic constants were determined using GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) as the initial substrate for either of the two epimerases. The kinetic constants for the epimerase from serotype HS:3 are kcat = 5.8 ± 0.2 s−1, Km = 440 ± 35 μM and kcat/Km = 13,200 ± 800 M−1 s−1. For the epimerase from serotype HS:15, the kinetic constants are kcat = 2.6 ± 0.1 s−1, Km = 180 ± 17 μM and kcat/Km = 14,400 ± 1,000 M−1 s−1. These kinetic constants are similar to that reported for the epimerase from serotype HS:2 (kcat = 3.5 ± 0.2 s−1, Km = 136 ± 16 μM and kcat/Km = 25,700 ± 3,400 M−1 s−1) using GDP-d-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose as substrate (15).

Mutation of Active Site Residues.

The three-dimensional structures of the C3- and C3/C5-epimerases reported here are all superimposable with one another (shown below), but the reaction outcomes are different. An amino acid sequence alignment for the seven epimerases evaluated for this investigation is provided in Figure 6. Even though the four epimerases that catalyze changes in stereochemistry at only C3 are all greater than 78% identical in amino acid sequence to the three enzymes that catalyze epimerization at both C3 and C5, there are regions in both sets of enzymes that are fully conserved in one group and fully conserved with another set of residues in the other group. One cluster of differentially conserved amino acids occurs between residues 39-60 and another between residues 100-120, where in each group there are seven residues conserved in one group and another residue conserved in the other group. In addition to these differences, there are five residues near the two critical active site residues (His-67 and Tyr-134) that are differentially conserved between the two groups of enzymes (12, 15). These residues include Ala-76, Ala-122, Glu-128, Ser/Thr-129, and Cys-136 for the C3-epimerases and Val-76, Ser-122, Lys-128, Glu-129, and Leu-136 for the C3/C5-epimerases (Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Multiple sequence alignment for the epimerases from serotypes HS:2, HS:3, HS:10, HS:15, HS:23, HS:12, and HS:42. The residues highlighted in yellow illustrate those that are conserved in the C3-epimerases while another amino acid is conserved (shaded grey) is conserved in the C3/C5-epimerases. Two active site general acid/base groups (histidine and tyrosine) are highlighted in blue.

We investigated the influence of these differentially conserved residues from the HS:3 serotype in an attempt to convert a C3-epimerase into one that catalyzes epimerization at both C3 and C5. The A76V, C136L, E128K/T129E, A76V/C136L, A76V/A122S/C136L, A39Y/V40L/D41L/L44V/N46D/L48I/I51K/H57N/K59H/H60F, and H100W/R102K/N106S/Q107Y/D108K/K111Q/I112L/V115L/A117P/G118N/F119M epimerase variants made of the wild-type enzyme from serotype HS:3 were assayed for their ability to catalyze the epimerization of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2). Epimerization activity at both C3 and C5 was observed only for the A76V/C136L and A76V/A122S/C136L variants after incubation with GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) for 15 h at 20 °C (pD 7.5) (Figure 7 and Figure S6).

Figure 7.

1H NMR 400 MHz spectra of products formed from GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-D-lyxo-heptose (2) by the addition of wild-type and variant epimerases from serotype HS:3. Reaction products GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-arabino-heptose (3), GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-ribo-heptose (4) and GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-β-l-xylo-heptose (5) formed by the catalytic activity of epimerases from HS:2 (A), HS:3 (B), A76V/C136L HS:3, (C) and A76V/A122S/C136L HS:3 (D). The epimerases (4 μM) were incubated with (2) for 15 h at 20 °C (pD 7.5).

Catalytic Activity of the Mutated Epimerases from Serotype HS:3.

The catalytic activities of the two mutant epimerases from HS:3 that possess C3/C5-epimerase activity were determined using a coupled enzyme assay using the C4-reductase from HS:2 by monitoring the oxidation of NADPH as a function of time. The assays were carried out at pH 7.5 and 25 °C. The kinetic constants were determined using GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) as the initial substrate for either of the two mutant epimerases. The kinetic constants for formation of the C3/C5-epimerized product are kcat = 0.032 ± 0.001 s−1, Km = 156 ± 12 μM and kcat/Km = 205 ± 12 M−1 s−1 for the A76V/C136L variant using the C4-reductase from serotype HS:2. The kcat, Km, and kcat/Km for the formation of the C3-epimerized product is 2.4 ± 0.2 s−1, 156 ± 12 μM, and 15,400 ± 1,750 M−1s−1, respectively, using the C4-reductase from HS:3 as the coupling enzyme. For the A76V/A122S/C136L variant, the kinetic constants for isomerization at C3/C5 are kcat = 0.052 ± 0.001 s−1, Km = 125 ± 12 μM and kcat/Km = 419 ± 62 M−1 s−1 using the C4-reductase from serotype HS:2. The kcat, Km, and kcat/Km for the isomerization at C3 are 2.5 ± 0.2 s−1, 125 ± 12 μM, and 20,000 ± 2,500 M−1 s−1, respectively, using the C4-reductase from serotype HS:3. It is clear that the two mutants are able to catalyze the additional isomerization at C5 but the rate, relative to that for the isomerization at C3, is significantly slower.

Crystal Structures of Epimerases from C. jejuni.

The crystals of the C-3 epimerase from C. jejuni serotype HS:3 in complex with GDP belonged to the space P212121 with a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The structural model was refined to an overall R-factor of 19.3% at 1.5 Å resolution. Each subunit of the dimer consists of 13 β-strands and two α-helices that fold into a classical “cupin” architecture. Members in this superfamily are remarkably diverse with some displaying enzymatic activities and others functioning as seed storage proteins (25). The α-carbons for the two subunits in the asymmetric unit superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.3 Å.

As can be seen in Figure 8a, the first four N-terminal amino acid residues and the β-hairpin motif formed by Asn-22 to Thr-36 from one subunit reach over to the second subunit to form a binding platform for the GDP ligand. As a consequence, the active site is shared between the two subunits. A stereo view surrounding the ligand (labeled B in the X-ray coordinate file) is displayed in Figure 8b. The guanine ring is positioned into the active site by the side chains of Asn-22, Thr-33, and Lys-54 and a water molecule (subunit A). The ribose hydroxyls lie within 3.2 Å of the backbone amide and carbonyl oxygen of Met-1 of subunit A and a water molecule. The pyrophosphoryl group is surrounded by six waters and the guanidinium groups of Arg-28 (subunit A) and Arg-64 (subunit B). The positions of the catalytic residues, His-67 and Tyr-134 (subunit B) are shown in Figure 8b. Note that Ile-66 adopts the cis peptide conformation. Also included in Figure 8b are the locations of Ala-76 and Cys-136, that were changed to a valine and leucine, respectively in this investigation.

Figure 8:

Structure of the C-3 epimerase from C. jejuni serotype HS:3. Shown in (A) is a ribbon drawing of the dimer as observed in the asymmetric unit. Those secondary structural elements involved in domain swapping are highlighted in green. The bound ligands (GDP) are displayed in sphere representations. The arrow indicates the twofold rotational axis of the dimer. A closeup view of the active site, in stereo, is provided in (B). Those side chains colored in green belong to subunit A whereas those displayed in blue are contributed by subunit B. The dashed lines indicate possible interactions between the protein and the ligand within 3.2 Å. Water molecules are drawn as red spheres.

Crystals of the C-3 epimerase from C. jejuni serotype HS:23/36 in complex with GDP belonged to the space P1 with a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The model was refined to an overall R-factor of 16.7% at 1.55 Å resolution. The α-carbons for the two C-3 epimerases from serotypes HS:3 and HS:23/36 superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.4 Å (subunits B), and the regions surrounding the ligands are identical within experimental error.

The crystals of the C3/C5 epimerase from C. jejuni serotype HS:15 in complex with GDP belonged to the space P21 with four dimers in the asymmetric unit. The model was refined to an R-factor of 19.1% at 1.9 Å resolution. The crystals of the C3/C5 epimerase from C. jejuni serotype HS:42 in complex with GDP belonged to the space P41212 with a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The model was refined to an R-factor of 20.7 % at 1.9 Å resolution. The α-carbons for these two C3/C5 epimerases superimpose with an approximate root-mean-square deviation of 0.4 Å. Importantly, within X-ray coordinate error, the immediate active site architectures for the four enzymes structurally interrogated in this investigation are identical including the cis peptides preceding the catalytic histidines.

Mechanism of Action.

Two different clusters of C3- and C5-epimerases have been characterized from the various serotypes of C. jejuni. The larger cluster is restricted to the epimerization of C3 of the common substrate GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-D-lyxo-heptose (2) while the smaller cluster efficiently epimerizes both C3 and C5. A third cluster that is apparently involved in the biosynthesis of 3,6-dideoxy heptose products has not thus far been characterized. It is apparent from the three-dimensional structures of the C3 and C3/C5-epimerases that these enzymes use a common set of residues that function as the general acid/base groups for the abstraction and donation of protons to C3 and/or C5 during the epimerization of these chiral centers. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain a high-resolution X-ray structure of either epimerase subgroup in the presence of a complete substrate/product. However, the previously determined three-dimensional structures of the homologous enzymes RmlC by the Naismith laboratory (26) and ChmJ by the Holden laboratory (27) strongly support the proposal that His-67 is utilized as the base to abstract a proton from either C3 or C5 of the bound substrate and that Tyr-134 is used as the general acid to reprotonate the carbanionic intermediate.

To test this proposal, we mutated His67 and Tyr134 from a C3-epimerase (from serotype HS:3) and a C3/C5-epimerase (from serotype HS:15) to an asparagine and phenylalanine, respectively. The four variants were purified to homogeneity and subsequently tested for catalytic activity using GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) as the substrate at a fixed concentration of 1.0 mM. None of the four variants were able to catalyze the isomerization of C3 of this substrate with a rate constant greater than 0.003 s−1. Under these conditions the wild-type C3-epimerase from serotype HS:3 has a rate constant of 5.4 s−1 and the C3/C5-epimerase from serotype HS:15 catalyzes the epimerization of C3 with a rate constant of 3.0 s−1. Thus, the four variants are reduced in catalytic activity by a factor of more than 3 orders of magnitude. The Creuzenet laboratory has previously shown that mutation of H67 and Y134 in the C3/C5- and C3-epimerases from serotypes HS:2 and HS:23/36, respectively, also showed significant reductions in catalytic activity but the specific rate constants were not quantified (12). In the proposed catalytic reaction mechanism for the C3- and C3/C5-epimerases His67 abstracts a proton from C3 and the negative charge is delocalized to the carbonyl group at C4. In the second step the process is reversed and C3 is reprotonated on the opposite face by Tyr134. It is also clear that for the C3/C5-epimerases that the process can subsequently be repeated at C5 for the ultimate isomerization at both C3 and C5. The chemical mechanism is depicted in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5:

Proposed mechanism of action.

What is not so clear is what specifically separates the C3-epimerases from the C3/C5-epimerases. Based on the identification of differentially conserved residues within the C3- and C3/C5-epimerases we have successfully changed Cys-136 and Ala-76, found exclusively in the C3-epimerases, to Leu-136 and Val-76, found only in the C3/C5-epimerases, and demonstrated that a C3-epimerase could be transformed into one that now catalyzes the epimerization at both C3 and C5. These two residues are indeed close to the two active-site general acid/base groups and thus it is quite probable that the two residues found within the C3-epimerases restrict the subtle conformational changes needed to access both C3 and C5. In the GDP-bound structures the thiol group of Cys-136 is 4.8 Å from the phenolic oxygen of Tyr-134. Electrostatic interactions between these two residues may restrict the mobility of Tyr-134 and thus render this residue unable to function properly for the epimerization of C5.

With the C3/C5-epimerases it is also quite apparent that the mono-epimerized products are released from the active site and that eventually an equilibrium mixture of four species is formed in solution. This means that the ultimate determinant of the final product formed is the C4-reductase. For example, in the HS:15 serotype the heptose product is 6-deoxy-l-gulo-heptose. This product is formed via the epimerization at only C5 and thus the C4-reductase must exclusively reduce the C5-epimerized intermediate (4). Perhaps this precludes the need for a C5-only epimerase.

Conclusions

In C. jejuni the 6-deoxy-heptoses found within the capsular polysaccharides are made from GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose via the combined actions of a 4,6-dehydratase, C3/C5-epimerase, and a C4-reductase. Here we have demonstrated that there are two major classes of epimerases in C. jejuni; those that catalyze the epimerization at C3 and those that catalyze the epimerization at both C3 and C5. Three-dimensional structures of both classes were determined to high resolution and the active sites were shown to be nearly identical, reflecting the greater than 76% sequence identity between the two epimerase classes. Mutation of two residues in the epimerase from serotype HS:3 was sufficient to convert an enzyme that catalyzes the epimerization at C3-only into one that could epimerize both C3 and C5. Two residues, His-67 and Tyr-134 are positioned to function as the general acid/base catalysts for the epimerization of C3 and C5. The structural constraints that limit the epimerization at a single chiral center are not clear.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was funded the National Institutes of Health (GM 139428 and GM122825 to FMR and GM 134643 to HMH).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

The SI include the amino acid sequences of the purified proteins; enzyme modifications; sequence identity matrix; and NMR spectra of carbohydrate substrates and products.

Accession Codes

Epimerases from serotypes HS:2 (UniProt entry: Q0P8I4), HS:3 (UniProt entry: F2X702), HS:10 (UniProt entry: F2X784), HS:15 (UniProt entry: A0A3Z9HSX9), HS:23/36 (UniProt entry: Q6EF58), HS:41 (UniProt entry: Q5M6T7), and HS:42 (UniProt entry: F2X7E5).

C4-reductases from serotypes HS:2 (UniProt entry: Q0P8I6), HS:3 (UniProt entry: F2X701), and HS:15 (UniProt entry: F2X7A6).

The authors declare no competing conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heimesaat MM, Backert S, Alter T, and Bereswill S (2021) Human Campylobacteriosis-A serious infectious threat in a One Health Perspective. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 431, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnham PM, and Hendrixson DR (2018) Campylobacter jejuni: collective components promoting a successful enteric lifestyle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 551–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaudet RG, and Gray-Owen SD (2016) Heptose sounds the alarm: Innate sensing of a bacterial sugar stimulates immunity. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosma P (2008) Occurrence, synthesis and biosynthesis of bacterial heptoses. Curr. Org. Chem 12, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlyshev AV, Champion OL, Churcher C, Brisson JR, Jarrell HC, Gilbert M, Brochu D, St Michael F, Li JJ, Wakarchuk WW, Goodhead I, Sanders M, Stevens K, White B, Parkhill J, Wren BW, and Szymanski CM (2005) Analysis of Campylobacter jejuni capsular loci reveals multiple mechanisms for the generation of structural diversity and the ability to form complex heptoses. Mol. Microbiol 55, 90–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St Michael F, Szymanski CM, Li JJ, Chan KH, Khieu NH, Larocque S, Wakarchuk WW, Brisson JR, and Monteiro MA (2002) The structures of the lipooligosaccharide and capsule polysaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni genome sequenced strain NCTC 11168. Eur. J. Biochem 269, 5119–5136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monteiro MA, Noll A, Laird RM, Pequegnat B, Ma ZC, Bertolo L, DePass C, Omari E, Gabryelski P, Redkyna O, Jiao YN, Borrelli S, Poly F, and Guerry P (2018) Campylobacter jejuni capsule polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. In Carbohydrate-based vaccines: from concept to clinic, pp 249–271, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huddleston JP, and Raushel FM (2019) Biosynthesis of GDP-D-glycero-α-D-manno-heptose for the capsular polysaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 58, 3893–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kneidinger B, Graninger M, Puchberger M, Kosma P, and Messner P (2001) Biosynthesis of nucleotide-activated D-glycero-D-manno-heptose. J. Biol. Chem 276, 20935–20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCallum M, Shaw SD, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2012) Complete 6-deoxy-D-altro-heptose biosynthesis pathway from Campylobacter jejuni: more complex than anticipated. J. Biol. Chem 287, 29776–29788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCallum M, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2013) Comparison of predicted epimerases and reductases of the Campylobacter jejuni d-altro- and l-gluco-heptose synthesis pathways. J. Biol. Chem 288, 19569–19580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnawi H, Woodward L, Fava N, Roubakha M, Shaw SD, Kubinec C, Naismith JH, and Creuzenet C (2021) Structure-function studies of the C3/C5 epimerases and C4 reductases of the Campylobacter jejuni capsular heptose modification pathways. J. Biol. Chem 296, 100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huddleston JP, and Raushel FM (2020) Functional characterization of Cj1427, a unique ping-pong dehydrogenase responsible for the oxidation of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose in Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 59, 1328–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huddleston JP, Anderson TK, Spencer KD, Thoden JB, Raushel FM, and Holden HM (2020) Structural analysis of Cj1427, an essential NAD-dependent dehydrogenase for the biosynthesis of the heptose residues in the capsular polysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 59, 1314–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huddleston JP, Anderson TK, Girardi NM, Thoden JB, Taylor Z, Holden HM, and Raushel FM (2021) Biosynthesis of d-glycero-l-gluco-heptose in the capsular polysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 60, 1552–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerlt JA, Bouvier JT, Davidson DB, Imker HJ, Sadkhin B, Slater DR, and Whalen KL (2015) Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST): A web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 1854, 1019–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, and Ideker T (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud SE, Wilkins MR, and A. RD, and Bairoch A (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (J. M. Walker, Ed.) pp 571–607, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laskowski RA, Moss DS, and Thornton JM (1993) Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol 231, 1049–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butty FD, Aucoin M, Morrison L, Ho N, Shaw G, and Creuzenet C (2009) Elucidating the formation of 6-deoxyheptose: biochemical characterization of the GDP-D-glycero-D-manno-heptose C6 dehydratase, DmhA, and its associated C4 reductase, DmhB. Biochemistry 48, 7764–7775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunwell JM, Purvis A, and Khuri S (2004) Cupins: the most functionally diverse protein superfamily? Phytochemistry 65, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong C, Major LL, Allen A, Blenkenfeldt W, Maskell D, and Naismith JH (2003) High-resolution structure of RmlC from Streptococcus suis in complex with substrate analogs locate the active site of this class of enzyme. Structure 11, 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubiak RL, Phillips RK, Zmudka MW, Ahn MR, Maka EM, Pyeatt GL, Roggensack SJ, and Holden HM (2012) Structural and functional studies on a 3’-epimerase involved in the biosynthesis of dTDP-6-deoxy-d-allose. Biochemistry, 51, 9375–9383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.