Abstract

Baiyinhua lignite was treated by hydrothermal treatment dewatering (HTD). The production characteristics of the gas, solid, and liquid were studied. Results show that HTD is an effective means to decrease water content and water-holding capacity. When the treatment temperature was increased to 310 °C, the moisture was reduced from 26.55% to 5.27%, and the dehydration rate reached 80.20%. At the same time, the carbon content and calorific value increased during the HTD process, which increased energy density. The H/C atomic ratio increased first, then decreased with the increasing temperature. The increase in the H/C atomic ratio was due to the breakdown of aromatic ether and formation of phenolic compounds at the low temperature. The phenolic compounds started to break at the high temperature, which resulted in the decrease in the H/C atomic ratio. These results can be proven by 13C NMR analysis. Combined with the analyses of calorific value, dehydration ratio, recovery of combustible product, and heat loss, the relative balance dehydration and deoxidation efficiency were evaluated, and 250 °C is a suitable temperature for the HTD process in lignite upgrading. The HTD process promoted the breakage and decomposition of weak chemical bonds in lignite, which resulted in many organic compounds in wastewater after the HTD process. The chemical oxygen demand and biochemical oxygen demand continually increase, and the biodegradability of the wastewater is relatively good. The index of biodegradability for wastewater is greater than 0.3 even at a hydrothermal treatment temperature of 310 °C. This indicates that wastewater can be subjected to biochemical treatment at a low treatment cost. At the same time, the metal ions and nonmetallic ions in wastewater and the gas component were studied. These research results aim to provide theoretical guidance for the industrialization of lignite hydrothermal modification.

1. Introduction

The “30–60 goals” of “carbon peaking and carbon neutral” proposed by our government, and the bottleneck of low coal utilization efficiency, serious environmental pollution, and high carbon emissions, have become a key issue again. China is rich in lignite reserves, which are an important energy guarantee for China’s social and economic development, especially for the long-cycle energy supply in the northeast of China. With the continuous exploitation and depletion of high-quality coal, the development and utilization of lignite resources are imperative.1,2 However, the high content of oxygen-containing functional groups leads to the high moisture content and low calorific value, which has seriously hindered the efficient and clean utilization of lignite. Dehydration and quality improvement of lignite are the keys to efficient and clean utilization of lignite.

At present, technology for pretreating lignite is still mainly based on evaporative dehydration, but there are some problems, such as high energy consumption and moisture reabsorption.3 HTD is a case in nonevaporative modification technology, in which moisture is removed as liquid water, and it greatly promotes the fracture and decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups in lignite. It is just an in-depth, comprehensive modification technology and has received attention from experts and scholars at home and abroad. Wu et al.4 used Ximeng lignite as the research object and investigated the physical and chemical structure of raw and HTD samples. The results demonstrate that the contents of moisture and the oxygen-containing functional groups quickly reduce with the increasing temperature. At the same time, HTD promotes the conversion of aliphatic structures to aromatic structural units. Liu et al.5 investigated the effect of HTD on pyrolysis characteristics for lignite. Results showed that HTD could effectively improve the pyrolysis tar yield, which was mainly caused by the transfer of hydrogen in water to the macromolecular structure of the lignite under elevated temperatures and high pressure. Wang et al.6 also demonstrated this process using the isotope method. However, the mechanisms by which hydrogen transfer takes place during hydrothermal pretreatment are still unclear.

In addition, hydrothermal pretreatment improves the surface characteristics of lignite, which not only increases the slurry concentration of the coal,7,8 but also improves the flotation characteristics. Both the clean coal yield and the recovery ratio of combustible matter are increased.9,10 These results indicate that hydrothermal pretreatment is a promising technology. It not only effectively reduces the water content. But also improves the downstream application of upgrading coal. However, the current research on hydrothermal treatment is mainly focused on the characterization of the physicochemical structure of the upgraded coal and its influence on the downstream applications, and there is a lack of research and evaluation on the characterization of the three-phase products of the hydrothermal pretreatment process itself. In this paper, the effect of hydrothermal modification on the properties of the three-phase products was investigated, and the hydrogen transfer mechanism of the hydrothermal modification process was elaborated upon. The research results serve as a theoretical basis and data support for the industrial application of the hydrothermal pretreatment of lignite.

2. Test Method

2.1. Hydrothermal Upgrading Process

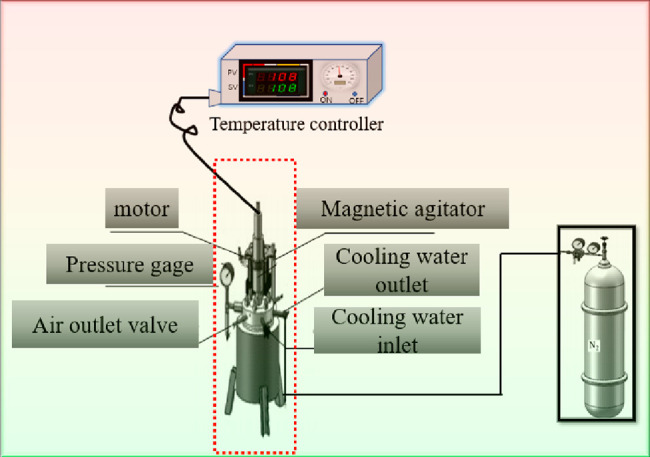

The hydrothermal treatment dewatering process is illustrated in Figure 1. A total of 160 g of air-dried basic coal and 200 mL of deionized water were mixed in a beaker and stirred in the reactor, and then 120 mL of deionized water was used to clean the remaining lignite in the beaker of the reactor. The lid was gently placed onto the reactor, being careful not to scratch the mechanical seal, and tightened with bolts, taking care to tighten the bolts diagonally. Then, 4 MPa nitrogen was injected into the reactor, and the stirrer was set at 200 r/min at the same time while maintaining the pressure gauge for 2 h to check the reactor gas tightness. After ensuring that the pressure remained constant for 2 h, the nitrogen was drained, and the pressure in the kettle was brought to atmospheric pressure, and the experiment was begun. To start, the thermostat was adjusted to the programmed temperature rise at 4 °C/min and maintained for 30 min at the end of the reaction. The solid–liquid reactants were weighed. The solids were kept separate from the liquids using a qualitative filter paper and a vacuum filter, and the liquids were placed in sealed jars prepared in advance and temporarily stored for analysis. The solid extracted coal was placed in a drying oven at 50 °C for 24 h to obtain air-dried basic coal samples, which were weighed and recorded. The final temperature was set to 150 °C, 200 °C, 250 °C, and 310 °C, and the samples were named after the sample name and the final temperature of the reaction, for example, HTD150.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the hydrothermal treatment process.

2.2. Test Analysis

2.2.1. Particle Size Analysis

The particle size variation in the lignite after the hydrothermal reaction was tested by a laser particle size meter produced by Malvern Instruments Ltd. in London. The sample refractive index was set to 1.70, the medium was water, the refractive index was 1.33, and the sharing ratio was 11.9%.

2.2.2. Gas–Liquid Phase Product Determination

The decarboxylation, decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups, and demethylation reactions that occur during hydrothermal processes result in the generation of small-molecule gas products. The gas-phase products were determined by a multifunctional gas chromatograph, model GC-7890, manufactured by Shandong Jinpu Analytical Instruments Co in Qingdao, China. Considering that the varying stability of the gas chromatograph, which is different every time, may produce errors in the detection value of the gas concentration, each batch, comprising a single coal sample, was used after all the thermal modifications to detect the gas components, and the standard gas was tested at least three times to determine the stability of the equipment at the peak of each component of the standard gas. The concentration of gas products was the ratio of the peak area to the total area of a component.

The high temperature and pressure reaction environment of the hydrothermal modification process lead to the breakage and decomposition of some weak covalent bonds in lignite. A considerable amount of soluble inorganic and organic carbon in the waste was dissolved. In this paper, the total carbon content in the hydrothermal waste was analyzed by a model LB-2000 instrument produced by Qingdao Lubo Xingye Environmental Protection Technology Co in Qingdao, China. The inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS2000), produced by Jiangsu Tianrui Instrument Co., Ltd. in Nanjing, China, was used to determine the metal cation. The anions were analyzed using an ion chromatograph produced by Guangzhou Xiaofen Instruments Co in Guangzhou, China.

2.2.3. 13C NMR

The 13C NMR test was operated at the Kexuezhinanzhen Analysis Center, and the model was a Bruker AVANCE 400 M solid state NMR instrument. The resonance frequency is MHz, and the static magnetic field is 9.37 T. The cross-polarization contact time is 3000 μs. The total sideband suppression is applied to eliminate the corner sideband. The magic angle rate (MAS) is 5 kHz. The cycle delay time and pulse delay time is 2 s and 16.5 μs, respectively. The time of scans is 200 s, and the time to obtain the carbon spectrum is 0.05 s. The assignment of different carbon structures, according to previous literature,5,10, was listed in Table 1. The carbon spectrum of raw and upgraded samples was analyzed and fitted by an original spectrum from 2018. The correlation index (R2) exceeds 0.99.

Table 1. Structure Assignment of Chemical Shifts in 13C NMR.

| Carbon styles | Chemical shift/ppm | Structure fragments | symbols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic carbon Fal | 0–16 | Aliphatic CH3 | Fal1 |

| 16–22 | Aromatic CH3 | ||

| 22–36 | CH, CH2 | ||

| 36–65 | Methine, quaternary | ||

| 65–100 | Oxygen-aliphatic carbon | Fal2 | |

| Aromatic carbon Far | 100–125 | Aromatic protonated | Far1 |

| 125–137 | Aromatic bridgehead | ||

| 137–150 | Aromatic branched | ||

| 150–165 | Phenol hydroxyl carbon | Far2 | |

| 165–190 | Carboxyl carbon | FCOO | |

| 190–220 | Carbonyl carbon | FC=O |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hydrothermal Treatment on Lignite Coal Quality Analysis

3.1.1. Industrial and Ultimate Analyses of Raw Coal and Upgraded Coals

The coal quality analysis of Baiyinhua raw and upgraded coals is listed in Table 2. As can be seen, HTD is an effective means of removing moisture from lignite. When the treatment temperature was increased to 310 °C, the moisture was reduced from 26.55% to 5.27%, and the dehydration rate reached 80.20%. The volatile content decreased continuously with increasing HTD temperature, which was mainly attributable to the decomposition and transformation of unstable oxygen-containing functional groups and the collapse of the pore structure.2,11 The decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups was the main intrinsic motivation for lignite’s avoidance of moisture reabsorption. In addition, the fixed carbon content increased and the oxygen content decreased with the increasing temperature. The lower oxygen content and higher fixed carbon content can reduce the risk of spontaneous combustion during transportation. This is mainly due to the fact that the ignition point of low-rank coals is closely related to their oxygen and fixed carbon content, with the ignition point increasing as the oxygen content decreases and the fixed carbon content increases.12

Table 2. Coal Quality of Baiyin Hua Raw Coal and Treated Coal Samples.

| Industrial analysis (wt %) |

Ultimate analysis (wt %, daf) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | Mad | Ad | Vdaf | FCdaf | C | H | N | S | Oa |

| BYH | 26.55 ± 0.22 | 25.56 ± 0.02 | 45.32 ± 0.01 | 54.68 ± 0.02 | 69.13 ± 0.01 | 4.91 ± 0.04 | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 24.02 ± 0.06 |

| HTD150 | 8.35 ± 0.05 | 25.68 ± 0.01 | 44.93 ± 0.02 | 55.07 ± 0.02 | 70.18 ± 0.02 | 5.09 ± 0.02 | 1.24 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 22.73 ± 0.05 |

| HTD200 | 7.86 ± 0.05 | 26.02 ± 0.01 | 43.26 ± 0.01 | 56.74 ± 0.01 | 72.36 ± 0.03 | 5.17 ± 0.01 | 1.23 ± 0.06 | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 20.41 ± 0.04 |

| HTD250 | 7.78 ± 0.03 | 26.38 ± 0.03 | 41.01 ± 0.03 | 58.99 ± 0.03 | 73.28 ± 0.01 | 5.49 ± 0.02 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.42 | 18.49 ± 0.13 |

| HTD310 | 5.27 ± 0.01 | 26.85 ± 0.01 | 38.19 ± 0.02 | 61.81 ± 0.02 | 75.46 ± 0.02 | 5.06 ± 0.01 | 1.28 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.14 | 17.42 ± 0.05 |

By difference.

3.1.2. Trends in H/C and O/C Atomic Ratio

The H/C and O/C atomic ratios of the upgraded coals are shown in Figure 2. As shown, the H/C atomic ratio increased and then decreased with increasing HTD temperature, with a maximum peak at 250 °C. This is consistent with the research results of Liu et al.13 and Zhang et al.,14 suggesting that this may be due to the transfer of hydrogen ions and hydroxide ions in the water to lignite through chemical ion channels during the HTD process, as shown by Schemes 1 and 2. Related studies showed that hot water can cause depolymerization of the coal macromolecular network structure by breaking weak covalent bonds, such as ether bonds. These ether bonds are relatively stable under thermal conditions, whereas they are unstable under hydrothermal conditions.15 In discussing these reactions and instability in hydrothermal environments, it should be noted that the physicochemical properties of water at high temperature are similar to those of an organic solvent. In these hydrochemical cracking reactions, water plays one or more roles as a catalyst, reactant, and reaction medium.16 Therefore, organic compounds with oxygenated functions are more likely to undergo ionic polymerization, bond breaking, and hydrolysis during the HTD process. Therefore, hydrogen ions and hydroxide ions in water can be transferred to lignite through ether bonding.

|

1 |

|

2 |

Figure 2.

Atomic ratio of H/C and O/C from raw coal and HTD coal.

When the treatment temperature was higher than 250 °C, the H/C atomic ratio began to decrease. The phenolic hydroxyl functional groups may begin to decompose when the treatment temperature is above 250 °C. The phenolic hydroxyl functional groups are more stable at low temperatures. Studies have shown that the thermal stability of the main oxygen-containing functional groups in lignite follow the order of phenolic hydroxyl groups > carbonyl groups > carboxyl groups > ether groups.13,17 Therefore, when the hydrothermal temperature was below 250 °C, the decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as carbonyl, carboxyl, and ether groups, was dominant. When the temperature was above 250 °C, the phenolic hydroxyl group started to decompose, leading to a decrease in the H/C atomic ratio.

To verify the accuracy of the hydrogen transfer mechanism during the HTD process, the raw coal and upgraded samples were tested by 13C NMR. The spectra of raw and upgraded samples, seen in Figure 3(a), indicate that there are two obvious peaks: the aliphatic carbon peak region (0–100 ppm) and the aromatic carbon peak region (100–165 ppm). In addition, the chemical shift at the range of 165–190 ppm and 190–220 ppm are carboxyl and carbonyl carbon. In order to quantitatively analyze the relative content of different carbon types by a single peak area to the total area of NMR spectra, the fitting curve of raw coal is used as an example and shown in Figure 3(b). The chemical shift range at 150–165 ppm is assigned to the phenol hydroxyl carbon. The content of the phenol hydroxyl carbon is calculated and shown in Table 3. The data indicated that the content of phenol hydroxyl carbon constantly increased below 250 °C from 9.19% to 10.37% of HTD250, and subsequently decreased. The hydrogen transfer mechanism of the hydrothermal modification process can be supported by these results.

Figure 3.

13C NMR spectra of raw and HTD samples: (a) original spectra of raw and HTD samples; (b) fitting-spectra of raw coal sample.

Table 3. Relative Content of Different Carbon Structure of Raw Coal and HTD Samples.

| samples | Fal1 | Fal2 | Fal1+ Fal2 | Far1 | Far2 | Far1+ Far2 | FCOO | FC=O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chemical shift (ppm) | 0–65 | 65–100 | 0–100 | 100–150 | 150–170 | 100–170 | 170–190 | 190–220 |

| raw coal | 32.12 | 2.78 | 34.90 | 49.97 | 9.19 | 59.16 | 4.55 | 1.39 |

| HTD150 | 31.27 | 3.12 | 34.39 | 50.78 | 9.50 | 60.28 | 4.23 | 1.10 |

| HTD200 | 30.89 | 2.04 | 32.93 | 52.27 | 9.91 | 62.18 | 3.98 | 0.91 |

| HTD250 | 26.83 | 1.85 | 28.68 | 56.48 | 10.37 | 66.85 | 3.67 | 0.80 |

| HTD310 | 25.95 | 1.37 | 27.32 | 59.79 | 8.99 | 68.78 | 2.91 | 0.99 |

In addition, as shown in Table 3, aliphatic carbon gradually decreases and aromatic carbon gradually increases, indicating the conversion and decomposition of the aliphatic structural units to aromatic structural units. The chemical shift at the range of 65–100 ppm is assigned the oxygen-containing aliphatic carbon, which showed generally a decreasing trend with the increasing HTD temperature. The oxygen-containing aliphatic carbon, such as alcohol hydroxyl, alkyl ether, and so on, has a slight increase at low temperature. This may occur because oxygen retained in the pore structure in lignite can form an oxygen-containing complex with nonradical polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as coronene and anthracene in the presence of oxygen.17 The reduction of oxidation effect and increment of breakage and decomposition reaction of unstable oxygen-containing functional groups with the increasing HTD temperature, which leads to decrease in the content of oxygen-containing aliphatic carbon.

Besides, the relative content of carboxyl and carbonyl carbon is generally decreased with the increasing HTD temperature. These results indicate that the decrease of the oxygen content in lignite comes from mainly the breakage and decomposition of oxygen-containing aliphatic functional groups, carboxyl, and carbonyl groups.

However, there is an issue that needs further discussion. Decomposition and fracture of ether bonds introduce hydrogen and hydroxide ions, so the O/C atomic ratio should have the same trend as the H/C atomic ratio during the HTD process. In contrast, the O/C atomic ratio decreased from 0.26 for the original coal to 0.17 for HTD310, indicating that the O/C atomic ratio decreased continuously with increasing temperature during the HTD process. This may have been caused by the simultaneous occurrence of hydrolysis reactions and decomposition reactions of oxygen-containing functional groups. Moreover, the decomposition rate is faster than the hydrolysis reaction rate.18 The O/C atomic ratio is an important parameter of coal rank and decreases as the rank increases. Coal formation in nature occurs under a certain pressure and temperature. The temperature and static pressure under the stratum provide conditions for coal formation, but temperature is the main factor. Under the action of these factors, the O/C atomic ratio decreases continuously, and the coal quality improves. The hydrothermal environment of high temperature and high pressure is similar to that seen in coal formation, so hydrothermal modification and quality improvement are also called artificial simulation of coalification.

3.1.3. Analysis of Hydrothermal Lifting Parameters

The effect of hydrothermal treatment can be evaluated in terms of calorific value, dehydration rate, combustible recovery and energy loss parameters.18,19

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where M0 and Mx represent moisture content of air-dried basic raw coal and upgraded coal, respectively; μ represents the yield of solid products after hydrothermal treatment; A0 and Ax represent the ash content of raw coal and upgraded coal samples under dry, basic conditions, respectively. Qnet. Ad0 and Qnet. Adx represent the calorific value of raw coal and upgraded coal samples under air-dry basic conditions, respectively.

Figure 4a shows the influence of hydrothermal treatment on the calorific value and dehydration ratio of lignite. As shown, the calorific value and the dehydration rate gradually increased with the increasing HTD temperature. When the temperature reached 310 °C, the calorific value increased from 18.23 MJ/kg for raw coal to 20.25 MJ/kg. Dehydration efficiency increases from 70.70% of HTD150 to 83.58% of HTD310, indicating that most water in lignite was removed, and the energy density increased. On the other hand, water removal can effectively improve the combustion efficiency of power plant boilers and reduce greenhouse gas emissions per unit of energy density.19

Figure 4.

Hydrothermally modified upgrading parameters: (a) low level calorific value and dehydration rate; (b) combustible matter recovery and heat loss.

The effect of HTD on combustible matter recovery and heat loss is shown in Figure 4b. As shown, the combustible matter recovery decreased as the hydrothermal temperature increased. The decrease in combustible matter recovery was mainly due to the decomposition and breakage of chemically unstable oxygen-containing functional groups, which decompose into small molecules of gas and tar material.20 The heat loss, on the other hand, increased as the treatment temperature increased, so the energy density of the upgraded coal increased after HTD. However, the growth rate in heat loss was significantly higher when the treatment temperature was above 250 °C. Taking into account the relative equilibrium deoxidation and energy loss, 250 °C is a more suitable temperature for hydrothermal modifications. In addition, the H/C atomic ratio has an important effect on downstream pyrolysis and coal liquefaction processes. Coal pyrolysis and liquefaction not only break the reaction of the alkyl aliphatic chain, but also the free radical reaction. The increase in the H/C atom ratio can increase the concentration of hydrogen radicals in the reaction process, and then achieve the stable formation of tar from hydrocarbon radicals. These results have been reported by our research and some other researchers.1,5,14 From this point of view, 250 °C is also the best temperature for lignite hydrothermal modification and improvement.

3.1.4. Analysis of the Effect of Hydrothermal Modification on the Particle Size of Lignite

The effect of HTD on the particle size distribution of lignite is shown in Figure 5. Particle size of lignite shifted to the left after hydrothermal upgrading, and the particle size of lignite followed a decreasing trend.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the effect of hydrothermal modification on lignite particle size.

To further analyze the influence of hydrothermal modification on particle size distribution, particle size parameters of raw coal and upgraded coal are listed in Table 4. The Dx is the size of the particle as a percentage of all particles that are smaller than this particle size. For example, D95 represents that 95% of the particle size is less than 7.85 and 4.76 μm for BYH and HTD310 samples, respectively. As can be seen from the table, particle size decreased with the increasing temperature. On the one hand, this was mainly due to the fact that lignite is easily marginalized. On the other hand, the lignite structure is loose, and its particle shape is irregular. The particle surface becomes more compact under the action of thermal stress in the process of modification, and particle size becomes smaller and tends to be regular.

Table 4. Parameters of Particle Diameter in Raw and Hydrothermally Dewatered Coals.

| Parameters

of particle size/μm |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | D10 | D25 | D50 | D75 | D90 | D95 |

| BYH | 140.66 | 95.94 | 56.57 | 28.90 | 13.47 | 7.85 |

| HTD150 | 135.89 | 92.85 | 54.66 | 27.94 | 13.01 | 7.60 |

| HTD200 | 119.34 | 81.09 | 47.85 | 24.55 | 11.52 | 6.75 |

| HTD250 | 117.92 | 78.82 | 45.36 | 22.56 | 10.24 | 5.86 |

| HTD310 | 82.75 | 56.33 | 33.22 | 17.10 | 8.05 | 4.76 |

3.1.5. Characterization of Liquid Products during Hydrothermal Treatment

The high-temperature and -pressure reaction environment of hydrothermal modification led to the dissolution of a large number of inorganic mineral salts. Table 5 shows the concentration of inorganic salts in the liquid product after hydrothermal modification. As can be seen from the table, temperature was the main factor in the removal of various inorganic salt ions from lignite to the increase in hydrothermal temperature. The number of inorganic salt ions removed gradually increased with the increasing temperature. The alkali metal ions of Na+ and K+ increased from 572 mg/L and 25.36 mg/L in HTD150 to 1120 mg/L and 133.58 mg/L in HTD310. The removal effect of alkali metal was significant, and the removal of alkali metal could effectively improve the corrosion and slagging of lignite in the later application process. Therefore, HTD effectively improves the downstream application of coal with a high alkali metal content.21 On the other hand, the alkaline earth metal cation concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ increased from 55.52 mg/L and 53.52 mg/L in HTD150 to 151.08 mg/L and 742.60 mg/L in HTD310, indicating that the hydrothermal modification was also effective in the removal of alkaline earth metals in lignite. The removal of alkaline earth metals can effectively reduce pipeline scaling problems in downstream applications. Inoue et al.22 used hydrothermally modified coal as direct coal liquefaction feed stock. Results show that hydrothermal treatment can effectively improve scale deposition due to the coal liquefaction on reactor walls and connecting pipes, and achieve long, stable operation of the liquefaction plant. This is mainly due to the decomposition of a large number of carboxyl functional groups during the hydrothermal treatment. In addition, scale precursors, such as exchangeable cations of Ca and Na, are reduced during the hydrothermal modification process. Moreover, the decrease in NaCl and CaCO3 also effectively inhibits the formation of iron sulfide and silica in scale components. The concentration of ions in liquid products gradually decreases with the increase in hydrothermal temperature, and may be due to the release of more sulfur elements in the form of H2S, SO2, and other gases with the increase in treatment temperature.23 The concentration of PO43– and NO3– in the liquid products showed no significant change with the increase in temperature.

Table 5. Main Cations and Anions in Wastewater after the HTD Process (mg/L).

| samples | Na+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | K+ | PO43– | SO42– | NO3– | Cl– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTD150 | 572.24 | 55.52 | 53.52 | 25.36 | 21.77 | 432.85 | 28.94 | 7.88 |

| HTD200 | 744.01 | 98.42 | 101.25 | 65.91 | 18.63 | 395.45 | 42.76 | 10.57 |

| HTD250 | 899.63 | 121.56 | 345.89 | 92.16 | 23.85 | 259.73 | 55.21 | 9.67 |

| HTD310 | 1120.56 | 151.08 | 742.60 | 133.58 | 19.78 | 153.42 | 57.99 | 12.11 |

The variation in the total organic carbon content in the liquid product of the increasing temperature during the hydrothermal modification process is presented in Figure 6. As shown, the total organic carbon content of the liquid-phase product increased with the rising temperature. This indicates that some weak chemical bonds broke during the hydrothermal process, and related studies have shown that the liquid product contains a large amount of inorganic matter and many furans, organic acids, and compounds such as alcohols.24 These results are consistent with the combustible product recovery of raw and upgraded samples. As shown in Figure 3 in the manuscript, the combustible product recovery continually decreases with the increasing HTD temperature. This combustible products loss is converted into the organic compound in the liquid-phase product and gaseous products.

Figure 6.

Concentration of total organic compounds in wastewater after HTD process.

To further investigate the influence of hydrothermal pretreatment on liquid water quality, the chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) of liquid water were analyzed and are shown in Figure 7a. As can be seen, COD and BOD values constantly rose with the increase in the hydrothermal pretreatment temperature, indicating that the breakage of unstable chemical bonds in the coal continued to increase. The wastewater treatment produced in the hydrothermal modification process is the most controversial issue based on energy consumption and cost consideration. However, as showing in Figure 7b, the biodegradability of wastewater was good. The biodegradability of wastewater was above 0.3, even at the hydrothermal treatment temperature of 310 °C. These results indicate that the biochemical treatment of wastewater at a relatively low cost can be adopted.

Figure 7.

Effect of HTD on water quality. (a) COD and BOD values; (b) biodegradability.

3.2. Characterization of the Gas Products of the Hydrothermal Treatment Process

The comparison between the actual monitored pressure of the reaction kettle and the saturated vapor pressure of water at the corresponding temperature is shown in Figure 8. The hydrothermal modification process, which involves a high temperature and high-pressure environment, led to the decomposition of volatile hydrocarbons and generated a lot of gas products. So, the actual monitoring pressure inside the reaction kettle should be greater than the saturated vapor pressure of liquid water corresponding to the temperature. The higher is the treatment temperature, the more gas is produced. Thus, the difference between the actual pressure and saturated vapor pressure continually increase with the increasing temperature in HTD.

Figure 8.

Actual pressure with the treatment temperature in the process of hydrothermal treatment.

The composition of the gas products at different temperatures is listed in Table 6. As shown, the major component of the gas product was CO2. Moreover, the content of CO2 increased with the increasing temperature in HTD. Specifically, the volume fraction increased from 35.55% of HTD150 to 71.98% of HTD310. The formation of CO2 mainly originates from the residual microporous structures in lignite and the decarboxylation reaction during the hydrothermal modification process.5,24,25 The increase in temperature intensified the decarboxylation reaction and led to an increase in the content of the CO2 component. The reaction pathways of the decarboxylation reactions during hydrothermal processes are presented in Figure 9. This result can be proven by the relative content of carboxyl carbon of raw and upgraded samples. As shown in Table 3, the relative content of carboxyl carbon continually decreases with the increasing HTD temperature. This is consistent with the volume fraction of CO2 released in the process of hydrothermal modification.

Table 6. Volume Percentage of Different Gas Products after Hydrothermal Modification.

| Samples | CO2/% | O2/% | N2/% | CO/% | H2/% | CnHm/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTD150 | 35.55 | 0.96 | 64.50 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| HTD200 | 39.39 | 0.82 | 58.71 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.25 |

| HTD250 | 52.25 | 0.55 | 44.79 | 1.62 | 0.17 | 0.62 |

| HTD310 | 71.98 | 0.42 | 24.11 | 1.84 | 0.58 | 1.07 |

Figure 9.

Reaction mechanism of decarboxylation during hydrothermal treatment dewatering.

The content of the CO component increased first and then decreased with the increase in the hydrothermal temperature, which may have been due to the thermal decomposition of carbonyl and ether–oxygen-containing functional groups.26,27 The content of organic small molecules (CnHm) was mainly derived from the fracture of alkyl side chains of aromatic structures. When the temperature reached 310 °C, the content of CnHm reached 1.07%, indicating that high temperatures promote the decomposition of volatile organic hydrocarbons and the formation and release of organic small molecules.

The oxygen and nitrogen in the gas products mainly come from the air and residue in the reaction kettle. In addition, in the process of hydrothermal modification, decomposition and fracture of some oxygen-containing groups and nitrogen-containing functional groups will also produce a certain amount of oxygen and nitrogen.24 Furthermore, the hydrogen component in the gas products may have been derived from a certain degree of dehydrogenation in the hydrothermal process.28−30

4. Conclusion

This paper comprehensively analyzed the evolution of lignite three-phase products during the hydrothermal modification process. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Hydrothermal modification is an effective means of reducing the moisture and lowering the water-holding capacity of lignite, which can effectively increase the carbon content and calorific value and increase the energy density. When the treatment temperature was increased to 310 °C, the moisture was reduced from 26.55% to 5.27%, and the dehydration rate reached 80.20%.

-

(2)

The H/C atomic ratio increased at first and then decreased with the increasing temperature. The increase at a low temperature was mainly due to the transfer of hydrogen ions in water to the macromolecular structure of lignite. The decrease at a high temperature was mainly due to the breakage of phenolic hydroxyl groups. The O/C atomic ratio continually decreased with the increasing temperature. Specifically, the O/C atomic ratio decreased from 0.26 to 0.17 for HTD310, which was the main reason for the decrease in the water-holding ability.

-

(3)

The treatment of wastewater via the HTD process is the most contentious issue in discussions concerning industrialization of hydrothermal treatment. Fortunately, the index of biodegradability for wastewater was greater than 0.3, even at a hydrothermal treatment temperature of 310 °C. This indicates that the wastewater can be subjected to biochemical treatment at a low cost.

-

(4)

A temperature of 250 °C seems to be appropriate for achieving hydrothermal upgrading of lignite, which basically achieves dehydration and deoxygenation of lignite. In addition, the relative integrity of the organic structure of lignite can be retained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Shucheng Liu and Keli Zhu; methodology, Qiang Zhou; software, Shucheng Liu; validation, Qiang Zhou and Jun Zhang; formal analysis, Shucheng Liu and Keli Zhu; investigation, Xingyuan Weng; resources, Qi Zhang; data curation, Jun Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Shucheng Liu; writing—review and editing, Jiaoyang Yang; visualization, Jiaoyang Yang; supervision, Jun Zhang; project administration, Jiaoyang Yang; funding acquisition, Shucheng Liu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 51372108) and the State Key Program for Basic Research of Basic research on large-scale utilization of low-quality coal (Grant No.:2012CB214902)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Liu S.; Zhao H.; Liu X.; Li Y.; Zhao G.; Wang Y.; Zeng M. Effect of hydrothermal upgrading on the pyrolysis and gasification characteristics of baiyinhua lignite and a mechanistic analysis. Fuel 2020, 276, 118081. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Wang J.; Liu J.; Yang Y.; Cheng J.; Wang Z.; Zhou J.; Cen K. Moisture removal mechanism of low-rank coal by hydrothermal dewatering: Physicochemical property analysis and DFT calculation. Fuel 2017, 187, 242–249. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.09.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L. C.; Zhang Y. W.; Wang Z. H.; Yan K.; Zhou J. H.; Cen K. F. Influence of microwave irradiation treatment on the pyrolysis characteristics of typical Chinese brown coal. Proc. CSEE 2014, 34, 1717–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Liu J.; Zhang X.; Wang Z.; Zhou J.; Cen K. Chemical and structural changes in XiMeng lignite and its carbon migration during hydrothermal dewatering. Fuel 2015, 148, 139–144. 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.01.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Wang L. L.; Zhou Y.; Pan T. L.; Lu Y. L.; Zhang D. X. Effect of hydrothermal treatment on the structure and pyrolysis product distribution of Xiaolongtan lignite. Fuel 2016, 164, 110–118. 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.09.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Pan T.; Liu P.; Zhang D. Hydrogen Transfer Route during Hydrothermal Treatment of Lignite Using the Isotope Tracer Method and Improving the Pyrolysis Tar Yield. Energy Fuel 2016, 30, 4562–4569. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b00281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Liu J.; Wang R.; Zhou J.; Cen K. Effect of hydrothermal dewatering on the slurryability of brown coals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 57, 8–12. 10.1016/j.enconman.2011.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J.; Wang J. Enhanced slurryability and rheological behaviors of two low-rank coals by thermal and hydrothermal pretreatments. Powder Technol. 2014, 266, 183–190. 10.1016/j.powtec.2014.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Guo F.; Xia Y.; Xing Y.; Gui X. Improved floatability of low-rank coal through surface modification by hydrothermal pretreatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119025. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Zhao H.; Zhou J.; Fan T.; Yang J.; Li G.; Wang Y.; Zeng M. The Effect of Hydrothermal Treatment on Structure and Flotation Characteristics of Lignite and a Mechanistic Analysis. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1930–1940. 10.1021/acsomega.0c04713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J.; Fei Y.; Marshall M.; Chaffee A. L.; Chang L. Hydrothermal dewatering of a Chinese lignite and properties of the solid products. Fuel 2016, 180, 473–480. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C.; Sung Y.; Ahn S.; Kim T.; Choi G.; Kim D. Thermochemical and combustion behaviors of coals of different ranks and their blends for pulverized-coal combustion. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 54, 111–119. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Li W.; Chen H.; Li B. The Adjustment of Hydrogen Bonds and Its Effect on Pyrolysis Property of Coal. Fuel Process. Technol. 2004, 85, 815–825. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2003.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.; Liu P.; Lu X.; Wang L.; Pan T. Upgrading of low rank coal by hydrothermal treatment: Coal tar yield during pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 141, 117–122. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.06.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C.; Favas G.; Wu H.; Chaffee A. L.; Hayashi J.; Li C. Effects of Pretreatment in Steam on the Pyrolysis Behavior of Loy Yang Brown Coal. Enery Fuel 2006, 20, 281–286. 10.1021/ef0502406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siskin M.; Katritzky A. R. Reactivity of organic compounds in hot water: Geochemical and technological implications. Science 1991, 254, 231–237. 10.1126/science.254.5029.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Zhao H.; Liu X.; Li Y.; Zhao G.; Wang Y.; Zeng M. Effect of a combined process on pyrolysis behavior of huolinhe lignite and its kinetic analysis. Fuel 2020, 279, 118485. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu s.; Zhao H.; Fan T.; Zhou J.; Liu X.; Li Y.; Zhao G.; Wang Y.; Zeng M. Investigation on chemical structure and hydrocarbon generation potential of lignite in the different pretreatment process. Fuel 2021, 291, 120205. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.; Dai Gl Qin R. Experimental study of low-teperature oxidation and self-reaction of heated coal under nitrogen atmosphere. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2021, 20, 992–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Lang J.; Li Y.; Huang P.; Zhou Z.. Influence of associated minerals and moisture on the cohesion characteristics of coal. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2021.

- Wiatowski M.; Muzyka R.; Kapusta K.; Chrubasik M. Changes in properties of tar obtained during underground coal gasification process. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 8 (5), 1054–1066. 10.1007/s40789-021-00440-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T.; Okuma O.; Masuda K.; Yasumuro M.; Miura K. Direct Liquefaction of Brown Coal Using a 0.1 Ton/Day Process Development Unit: Effect of Hydrothermal Treatment on Scale Deposition and Liquefaction Yield. Energy Fuel 2012, 26, 5821–5827. 10.1021/ef300999r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Q.; Liao J.; Chang L.; Chaffee A. L.; Bao W. Transformation behaviors of C, H, O, N and S in lignite during hydrothermal dewatering process. Fuel 2019, 236, 228–235. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.08.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mursito A. T.; Hirajima T.; Sasaki K.; Kumagai S. The effect of hydrothermal dewatering of Pontianak tropical peat on organics in wastewater and gaseous products. Fuel 2010, 89, 3934–3942. 10.1016/j.fuel.2010.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.; Zhang Z.; Qiang L.; Gao T.; Lan T.; Sun M.; Xu L.; Ma X. Study on the pyrolysis characteristics of a typical low rank coal with hydrothermal pretreatment. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 3871–3880. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b04312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Liu J.; Yuan S.; Zhang X.; Liu Y.; Wang Z.; Zhou J. Sulfur Transformation during Hydrothermal Dewatering of Low Rank Coal. Energy Fuel 2015, 29, 6586–6592. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b01258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Zhou Q.; Li G.; Feng L.; Zhang Q.; Weng X.; Zhang J.; Ma Z. Remoal of O-containing functional groups during hydrothermal treatment dewatering: A combined experimental and theoretical theory study. Fuel 2022, 326, 124971. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyoni B.; Duma S.; Bolo L.; Shabangu S.; Hlangothi S. P. Co-pyrolysis of South African bituminous coal and Scenedesmus microalgae: Kinetics and synergistic effects study. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 7 (4), 807–815. 10.1007/s40789-020-00310-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Li Y.; Song Q.; Liu S.; Ma L.; Shu X. Catalytic reforming of volatiles from co-pyrolysis of lignite blended with corn straw over three iron ores: Effect of iron ore types on the product distribution, carbon-deposited iron ore reactivity and its mechanism. Fuel 2021, 286, 119398. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Li Y.; He Y.; Kong D. B.; Klein B.; Yin S.; Zhao H. Co-pyrolysis characteristics of lignite and biomass and efficient adsorption of magnetic activated carbon prepared by co-pyrolysis char activation and modification for coking wastewater. Fuel 2022, 324, 124816. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]