Abstract

This mini-review summarizes the development of intracellular fluorogenic probes for biological investigations of hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite (HOCl/OCl–) in living cells and tissues. Monitoring the formation or effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) inside living systems is critical in determining their roles in human physiology. HOCl/OCl– is considered as an important member of the nonradical ROS family for its decisive microbicidal action in the innate immune system. Even though HOCl/OCl– plays a defensive role in human health, abnormal or overexpression may have detrimental effects on the host physiology leading to many diseases, including neurodegeneration and cancer. In recent years, progress in the development of fluorescent imaging probes for observing HOCl/OCl– levels in live cells and tissues has been made. Despite considerable advancement, challenges still exist in areas like working solvent/media, pH, response time, buffer selection, emission region, and others. In addition, this account aims to discuss the design strategies and sensing mechanisms of the representative fluorogenic probes for bioimaging of HOCl/OCl–, endogenously and exogenously. Herein, we also have tried to provide the future direction to develop HOCl/OCl– specific probes for disease diagnosis with particular attention to the requirement of the recognition group, solvent, and buffer media, which will be beneficial for those working in the domain of biomedical research.

Introduction

Hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite (HOCl/OCl–) is an essential nonradical reactive oxygen species (ROS), which plays a pivotal role in our body’s defense mechanism.1 A typical concentration of HOCl/OCl– is a crucial requirement to maintain a healthy lifestyle. In this context, understanding the endogenous actions of HOCl/OCl– is of paramount interest. Inside live cells and tissues, HOCl/OCl– is highly reactive and its endogenous levels fluctuate rapidly. Therefore, a fast responsive detection method is highly desirable to monitor the analyte at the cellular site. HOCl/OCl– acts as a powerful microbicidal agent in the innate immune system.3 HOCl/OCl– is a highly potent oxidant, with Cl in the +1 oxidation state.4 It is generated during phagocytosis. Inside living organisms, hypochlorite is generated due to the peroxidation of chloride ions, catalyzed by a heme enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO). The latter is mainly localized in the leucocytes, including neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes.1,2 More specifically, activated neutrophils help in the secretion of MPO along with superoxide. The oxygen-centered free radical superoxide (O2•–) dismutases spontaneously to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) via an enzymatic process, which afterward reacts with MPO to produce HOCl. The average level of HOCl in human body fluid is around 200 μM.2 However, in diseased airways, its levels can reach up to mM.2 Regulated production of HOCl is required for the host to defend itself from the invading pathogens.5 For this reason, HOCl is also well-known as a key “killer” for pathogens.5 The evidence suggests that intracellular HOCl is essential in regulating inflammation and cellular apoptosis.1,2 However, aberrant accumulation of HOCl could pose a risk to the host physiology attributed to the oxidative damage of the biological proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.6 The oxidative stress mediated by HOCl triggers various diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, neuron degeneration, and arthritis.7 Divergent levels of intracellular HOCl can also cause mitochondrial permeabilization, lysosomal rupture, and cell death.8 Neutrophil-derived HOCl has been found connected to lung injury, arthritis, hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury, and renal disease.1,9 Recently, overexpression of HOCl has been identified as a biomarker of early diagnosis of osteoarthritis.10 Despite the significant roles of HOCl/OCl– in human health, the mechanism of action of HOCl is not well comprehended because of the lack of feasible tools for real-time monitoring of the analyte at subcellular levels.

The fluorescence imaging technique has emerged as a powerful tool for determining biological processes with a high spatial resolution.11 Fluorogenic dyes have revolutionized the imaging technique by establishing it as a fantastic tool for monitoring various biological species in cells and organisms.12 Therefore, integrating an organic dye as a signaling unit with a target specific binding motif within a single molecule has evolved as a topic of utmost interest. Several examples of HOCl/OCl– selective fluorogenic probes have appeared in recent years wherein various interaction pathways such as p-methoxyphenol oxidation to p-benzoquinones, oxime oxidation to aldehydes, p-aminophenol analogs oxidation, oxidation of chalcogenides (S, Se, and Te), cleavage of carbon–carbon double bonds, and a few other oxidative processes were explored (Scheme 1).2 However, very few probes are soluble in 100% water, i.e., no organic solvent was used in the experiments.3−6,9,10,12−33 Considering the importance of HOCl/OCl– levels in various biological processes, water-soluble fluorogenic probes are highly preferable for biomedical research. For biological uses, fluorogenic dyes should possess a few characteristics, such as high fluorescence intensity, low excitation energy, long emission wavelength (far-red, NIR (near-infrared) probes), low detection limit, rapid response time, cell membrane permeability, and nontoxicity.12,14,22,30 This mini-review provides an overview of the advancement of 100% water-soluble intracellular fluorogenic probes, which might be useful to monitor both endogenous and exogenous HOCl/OCl– levels in live cells and tissues. The scientific community has devoted significant efforts to shape various interaction pathways to develop the techniques for detecting HOCl/OCl–.1,2,11,34 Therefore, various HOCl/OCl– specific recognition sites and mechanistic details have also been discussed herein (Scheme 1). Furthermore, challenges that have been entirely under-investigated by the researchers while developing intracellular HOCl/OCl– specific probes are also addressed in this account. In summary, this mini-review emphasized the needs and opportunities in designing new water-soluble probes to monitor the intracellular levels of HOCl/OCl–.

Scheme 1. Schematic Representations of Fluorescent Probes with HOCl/OCl– Specific Chemo Recognition Sites.

Design of Water-Soluble Fluorogenic Probes for Intracellular Recognition of Hypochlorite/Hypochlorous Acid

Endogenous HOCl/OCl– is formed through various intracellular biochemical processes involving electron transport chains. Generally, mitochondria are the primary source of ROS in most cells. Overexpression of HOCl/OCl– can destroy the mitochondrial permeability and promote cell apoptosis. Overproduction of HOCl has recently been considered a prominent symptom in the early onset of osteoarthritis. HOCl also irreversibly disrupts the calcium homeostasis inside the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), eventually leading to cell dysfunction and even apoptosis. Accordingly, monitoring OCl– in the cellular compartments is imperative to reveal its diverse physiological and pathological functions. Considering its biological importance, reagents for efficient recognition, quantification, and mapping of intracellular HOCl/OCl– are highly preferred. The fundamental challenging feature in this area is designing selective fluorescent probes with HOCl/OCl– specific chemo recognition site(s) (Scheme 1). However, challenges still exist because of similar reactions with competitive ROS/RNS (reactive nitrogen species) present in the response sites. Recently, selective reaction sites for HOCl/OCl– detection coupled with various electron transfer mechanisms have been well established.2,34 In this mini-review, our discussions on this topic would be limited to those 100% aqueous soluble (i.e., no organic solvent requirement for probes’ solubilization) intracellular fluorogenic probes that have demonstrated their cellular applications. Furthermore, mechanistic details involving different electron transfer processes such as PET (photoinduced electron transfer), ICT (intramolecular charge transfer), and FRET (Forster resonance energy transfer) are discussed.

HOCl/OCl– Induced Oxidation of p-Methoxyphenol to Benzoquinone

Based on the ability of HOCl to oxidize p-methoxyphenol to benzoquinone (Scheme 1A), Yang and co-workers have reported a BODIPY (boron dipyromethane)-derived HOCl responsive PET-based probe that triggered “turn-on” fluorescence.3 Because of the PET process, 1 is nonfluorescent (ΦF < 0.01). The nonfluorescent nature of 1 has been attributed to the higher highest occupied molecule orbital (HOMO) energy level (−8.71 eV) of the p-methoxyphenol moiety than that of the BODIPY unit (−9.14 eV). On interaction with HOCl, 1 is completely oxidized to its corresponding quinine (Figure 1, top), thereby lowering the HOMO energy level (−10.9 eV) of the benzoquinone moiety than that of the BODPY scaffold. Accordingly, disruption of the PET process has resulted in a 1079-fold increase in the emission intensity of 1 at 541 nm. Various spectroscopic techniques have identified oxidized product. Moreover, it has been found that 1 remained selective toward HOCl over a broad pH regime (4–9). Other ROS and RNS failed to induce any optical changes. However, with peroxynitrite, 1 showed a little fluorescence at a higher concentration. Considering the significance of HOCl inside live cells, 1 was successfully demonstrated for luminescence visualization of enzymatically stimulated HOCl production in RAW264.7 cells. As shown in Figure 1 (bottom), modulation in fluorescence intensity implicated the potential of 1 for detecting HOCl inside live cells. The rapid response time of 1 towards HOCl, and low excitation energy, renders its potential application for bioimaging the production of HOCl in living macrophage cells.

Figure 1.

Top: structure of 1 and the reaction mechanism of it with HOCl. Bottom: images of RAW264.7 macrophages treated with various stimulants: (a) control; (b) LPS and IFN-γ for 4 h, then PMA for 0.5 h; (c) TEMPO, LPS, and IFN-γ for 4 h, then PMA for 0.5 h. For more details, see ref (3). Reproduced from ref (3). Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society.

Fluorogenic Probes with Se and S as HOCl/OCl– Target Specific Sites

One electron oxidation of chalcogenides to the respective oxidized products upon reaction with strong oxidants such as HOCl/OCl– has so far been utilized as an important design strategy for developing HOCl/OCl– selective probes (Scheme 1B).2 Selenides and thioethers are electron-donating groups, which can be oxidized to the respective electron withdrawing selenoxides and sulfonates on reaction with HOCl/OCl–. As a result, significant optical changes can be observed. Based on the selenoxide elimination reaction, Jiang et al. have developed Se-containing coumarin-derived fluorogenic probes.6 HOCl facilitated a selenoxide elimination reaction strategy involving a two-step process. Oxidation of Se and subsequent intramolecular syn elimination generated a conjugated alkene bond. Because of selenylation, the nonconjugated probes 2a (ΦF = 0.036) and 2b (ΦF = 0.047) are nonfluorescent. Restoration of the conjugation due to HOCl triggered selenoxide elimination reaction resulted in a “turn-on” response of the probes (Figure 2, top). The “turn-on” spectral feature of the probes toward HOCl over a wide range of pH (4–9) suggested the possibility of detecting both HOCl as well as OCl–. Furthermore, other ROS failed to induce any detectable optical changes with 2a. The rapid response time (within seconds) and water solubility of 2a have enabled the detection of both exogenous and endogenous HOCl/OCl–. The authors have successfully tested 2a for imaging of exogenous OCl– in NIH3T3 cells, as shown in Figure 2 (middle). Bright fluorescence was observed after incubating 50 μM NaOCl with 2a pretreated cells. To further investigate its applicability in the imaging of intracellular HOCl/OCl–, 2a was also exposed to RAW264.7 macrophages and HL-60 human progranulocytic leukemia cell lines. In both cell lines, MPO is highly expressed in primary azurophilic granules of leukocytes, including neutrophils and macrophages. Initially, both cell lines showed weak fluorescence response (Figure 2a,e). However, stronger fluorescence was noticed when 2a loaded HL-60 cell lines upon treatment with 100 μM H2O2 for 20 min. The observation concluded the requirement of H2O2 to activate the MPO for converting Cl®– to OCl–. Incubation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in RAW264.7 macrophages also enhanced the fluorescence intensity after incubation of 2a (Figure 2, bottom), thus confirming the generation of endogenous OCl–. The successful biological investigations have proved the potential of 2a in the visualization of endogenous OCl– in progranulocytes and macrophages. The low detection limit (10 nM) and rapid response time (within seconds) of the probe toward HOCl/OCl– over a broad pH range makes it a good candidate for real-time monitoring of HOCl/OCl–. However, the blue emissive property of the probe poses a major limitation in this context.

Figure 2.

Top: structures of 2a and 2b and their reaction with HOCl/OCl–. Middle: fluorescent imaging of exogenous OCl– in 2a labeled NIH3T3 cells: (i) control; (ii) 2a treated with NaOCl for 30 s; (iii) bright field image of panels i and ii. Bottom: fluorescent imaging of endogenous OCl– in 2a-labeled HL-60 (a–d) and RAW264.7 (e–h) macrophages. For more details, see ref (6). Reproduced from ref (6). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Another Se containing NIR dye has been developed by Peng et al. to detect HOCl.12 A heptamethine cyanine probe with rapid response and high selectivity for HOCl was observed via an aggregation pathway. Probes possessing NIR characteristics are highly preferred for biological investigations due to their minimal photodamage in biological samples, good tissue penetration, and correction of weak autofluorescence interference from complicated living systems. Cyanine dyes with NIR features are known for self-aggregation in the aqueous medium. With this knowledge, probe 3 has been designed by incorporating redox-sensitive divalent selenium atom in a cyanine core for specific detection of HOCl. Probe 3 exhibited a “turn-off” response in a PBS buffer (pH = 7.4) due to aggregation. Upon interaction with HOCl, 3 showed a high “turn-on” response at 786 nm within 100 s (Figure 3, top). The formation of new quadrivalent Se species was confirmed via 77Se nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra and time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOF-MS). The high selectivity of the NIR probe toward HOCl over other ROS/RNS encouraged the investigators to check its potential in a complex biological system. Owing to its spectacular NIR spectroscopic features, 3 was employed to detect HOCl in mice. Initially, HOCl was visualized in the mouse by injecting 3 and NaOCl in the right leg of the mouse, as shown in Figure 3 (bottom). After that, endogenous HOCl imaging was checked in mice. After the treatment of 3 in both the legs of the mouse (regions A and B), a stable fluorescence was observed in area A. In region B, the fluorescence gradually increased because of the generation of enzymatically stimulated HOCl. The investigations concluded the suitability of 3 for detection of HOCl, both endogenous as well as exogenous, in live mice. Albeit a tedious synthetic procedure, the robust “turn-on” nature of the NIR dye toward HOCl with a detection limit of 310 nM over a broad pH range (4–10) emerged as one of the suitable candidates for monitoring HOCl in biological samples.

Figure 3.

Top: structure of 3 and its reaction with HOCl. Bottom: representative fluorescence images of a mouse given a skin-pop injection of 3. For more details, see ref (12). Reprinted with permission from ref (12). Copyright 2014 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Churchill and co-workers actively utilized the OCl– specific oxidation of thioether to sulfoxide to develop BODIPY-based water-soluble “turn-on” fluorogenic probe.4 Because of the PET occurring between the electron-rich meso-thienyl donor moiety to the acceptor BODIPY moiety, probe 4a yielded a low quantum yield (ΦF = 0.050). In the presence of OCl–, the PET process is inhibited due to the oxidation of the thienyl moiety resulting in an alteration of the spectral property (Figure 4, top (right)). Furthermore, the pH profile study indicated that the working pH window of probe 4a falls within 7–10. As a result, the probe showed a selective response toward OCl– instead of HOCl. Presumably, the presence of the carboxylic group in 4a has made the probe water-soluble nature, and therefore, 4a has been explored for bioimaging of OCl– in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. However, the low cell permeability of 4a exhibited an inadequate fluorescence response inside the cells. Therefore, 4b was modified by replacing the acid with an ester moiety for neurological studies. As a result, the lipophilic nature of the probe increased significantly. As expected, 4b has easily permeated through the cell membrane and transformed into the carboxylate version due to esterase action in the cytosol. Figure 4 (bottom) depicted a “turn-on” response of 4b in neuronal cells, which is responsible for excess MPO activity. The long response time of the red emissive 4b marks a significant limitation in bioimaging OCl– selectively in cells.

Figure 4.

Top: structures of 4a and 4b (left) and 4a’s reaction with OCl– (right). Bottom: (i) bright field and (iv) fluorescent images of untreated SH-SY5Y cells; (ii) bright field and (v) fluorescent images after the treatment with 4b; (iii) bright field and (vi) fluorescent images of NaOCl with 4b in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma. For more details, see ref (4). Reprinted with permission from ref (4). Copyright 2013 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Osteoarthritis is a chronic and degenerative joint disorder that severely impairs the living quality of any person.10 Recently, overproduced HOCl has been considered a prominent symptom in the early onset of osteoarthritis. To evaluate OCl– for early diagnosis of osteoarthritis, Yu and the group reported a phenothiazine-derived coumarin dye that showed remarkable selectivity for OCl–.10 The oxidation of the sulfur atom of the probe exhibited a significant increase in the fluorescence intensity of 5 at 503 nm (ΦF = 7.8%). The inhibition of the ICT process from electron-rich phenothiazine scaffold to electron-deficient carboxyl coumarin has resulted in a “turn-on” response. Various spectroscopic techniques have confirmed the expected oxidized product, as shown in Figure 5 (top). Probe 5 exhibited excellent selectivity over pH 4–10, indicating the response of 5 for both HOCl as well as OCl–. The rapid “turn-on” spectral behavior was next utilized to image endogenous OCl– generated by stimulating interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in RAW264.7 macrophages. The high fluorescence intensities in all three cases (Figure 5, bottom) have confirmed the permeability of 5 through the cell membrane of the stimulated cells. The intracellular biochemistry of OCl– was further explored by pretreating the LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells with ABAH (4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide), a potent MPO inhibitor. Low fluorescence suggests the inhibition of MPO activity by significantly reducing the generation of OCl–. This observation has encouraged Yu and co-workers to test the anti-inflammatory response of selenocysteine (Sec), and methotrexate (MTX) in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. The observations from Figure 6 (top) depicted the inhibition of OCl– by Sec and MTX triggered cytoprotective action. As shown in Figure 6 (bottom), the treatment efficacy of MTX in osteoarthritis mice was also investigated by the authors. The results inferred the suppression of OCl– by both drugs. Therefore, the drugs have the potential to be used for osteoarthritis treatment. The detailed biological investigations for the detection of OCl– in osteoarthritis mice conclude the role of HOCl as a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Therefore, the probe’s excellent selectivity and sensitivity with a nM detection limit (16.1 nM) towards OCl– can be considered a potential candidate for early diagnosis of osteoarthritis in patients.

Figure 5.

Top: structure of 5 and its reaction with OCl–. Bottom: (A) generation of OCl– in RAW264.7 cells treated with different stimuli using 5; (B–F) fluorescence intensities collected from the corresponding images. For more details, see ref (10). Reproduced from ref (10). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Figure 6.

Top: protective effects of different agents in inflamed RAW264.7 cells using 5. (a1–e1) Bright field and (a2–e2) fluorescent images of cells treated with 5 and different agents. For more details, see ref (10). Bottom: (A) protective effects of other agents in BALB/c mice with the OA model using 5; (B–F) fluorescence intensities collected from respective images; (G) representative H&E staining of the knee slices from the mice treated under various conditions. For more information, see ref (10). Reproduced from ref (10). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

In 2017, Ye and co-workers documented a lysosome-targeted naphthalimide-based two-photon fluorescent probe for intracellular imaging of HOCl.13 The pendant methyl thioether group of the probe acts as a redox cycle between HOCl and glutathione. The high fluorescence nature of 6 has been assigned due to the favorable ICT process in the naphtalimide framework. OCl–-induced oxidation of the S atom to sulfoxide has resulted in a complete “turn-off” response (Figure 7, top). Furthermore, 6 was also explored for two-photon imaging of OCl– because of the strong fluorescence responses of 6 at 405 and 800 nm. Not to mention that two-photon microscopy has many advantages due to its long wavelength excitation, deeper tissue penetration, and three-dimensional imaging of the live cells. Figure 7 clearly shows the imaging of the exogenous OCl– in MCF-7 cells. The monitoring of the lysosomal OCl– fluctuations was also achieved by introducing morpholine moiety into the naphthalimide scaffold. As shown in Figure 7, the fluorescence intensity of 6 is colocalized smoothly with LysoTracker Red DND-99, and the Pearson’s overlap coefficients of 0.8789 and 0.8937 suggest the potential of 6 to be useful as a commercial LysoTracker. Therefore, the bioimaging investigations using two-photon microscopy offered 6 as an efficient probe for monitoring intracellular OCl– in the lysosomes. However, the “switch-off” nature of 6 in the presence of OCl– limited its real-time application in live cells as biological studies prefer a “turn-on” probe.

Figure 7.

Top: structure of 6 and its reaction with OCl–. Middle: (A) (a and c) bright field and (b and d) fluorescent images of OCl– in MCF-7 cells with 6; (B) one-photon bright field (a and d), fluorescent (b and e), and merged images (c and f) of live 4T1 cells with 6. Bottom: (C) two-photon bright field (a and d), fluorescent (b and e), and merged images (c and f) of live 4T1 cells with 6. (D) (a–d) Confocal images of live 4T1 cells pretreated with 6 and LysoTracker Red DND-99; (e and f) intensity profile and intensity correlation plot of 6 and LysoTracker Red DND-99. For more details, see ref (13). Reproduced from ref (13). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Increasing the electron density on the sulfur atom through the electron-donating phenothiazine core, Zhao and co-workers have established a phenothiazine-hemicyanine-derived OCl– specific fluorescent probe (7).14 The oxidation of sulfur to sulfoxide resulted in the inhibition of the PET process from phenothiazine to hemicyanine group, which has allowed the detection of OCl– via “turn-on” fluorescent at 595 nm. Furthermore, an increase in OCl– concentration has resulted in the emission intensity change via cleavage of C=C from the sulfoxide product (Figure 8, top). The structural changes of 7 with a gradual increase in OCl– concentration are evident in Figure 8 (top). The significant decrease in fluorescence intensity at 595 nm around pH 10–12 indicated the cleavage of the alkene bond. The practical applicability of 7 has been further tested by visualization of intracellular OCl– using L929 cell lines. Figure 8 (bottom) has concluded the permeability of 7 in the intracellular area and the ability to detect exogenous OCl– in L929 cell lines. The ratiometric probe 7, with remarkable fluorescence enhancement accompanied by a distinct color shift, can be offered as a promising candidate for the detection of OCl– in biological samples.

Figure 8.

Top: structure of 7 and its reaction with OCl–. Bottom: (a and d) bright field, (b and e) fluorescent, and (c and f) merged images of L929 cells with 7 in the presence and absence of OCl–. For more details, see ref (14). Reprinted with permission from ref (14). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

HOCl/OCl– Induced Oxidation of p-Aminophenol Analogues

p-Aminophenyl aryl ether analogs are known to react expeditiously with HOCl/OCl– to give the corresponding imine via an ipso substitution mechanism (Scheme 1C).2 Using this cascade strategy, Libby and co-workers have reported a water-soluble sulfonaphthoaminophenyl fluorescein, as a NIR probe 8 (Figure 9), for the detection of HOCl.15 Because of the oxidative cleavage of the 4-aminomethyl moiety upon interaction with HOCl, as envisaged, highly “turn-on” spectral response at 676 nm was noticed. Accordingly, the dye with an extended π system restored red fluorescence in a PBS buffer (pH = 7.4). Because of better spectral separation from cellular absorption, red emissive fluorescent probes are highly attractive for bioimaging studies. Thus, 8 was further utilized to detect endogenously generated HOCl in human neutrophils. Activated neutrophils can cause high levels of MPO. The researchers successfully achieved the detection of PMA (phorbol-12-myrisate-13-acetate) stimulated HOCl generation in human neutrophils. However, no fluorescence response was observed when a specific amount of MPO inhibitor (ABAH) was induced in the stimulated cells, inferring the requirement of MPO to generate endogenous HOCl. The biochemistry of HOCl was further explored by detecting HOCl in stimulated murine macrophages transgenic in human MPO (h-MPOTg). Murine macrophages are not capable of generating immune-reactive MPO. After coincubation with MPO inhibitor, completely switched off fluorescence intensity. Probe 8 has also been successfully employed to detect stimulated human MPO-containing macrophages. Motivated by the previously mentioned results, fluorescence reflectance imaging of HOCl in hMPO-Tg mice was also performed by Libby et al. The in vivo imaging of HOCl was performed in experimental murine peritonitis (evident from Figure 10, top). A “turn-on” spectral response was observed when hMPO-Tg mice peritonitis was induced with thioglycollate. However, no fluorescence response was observed when 8 was injected into control mice with peritonitis. Thus, indicating the role of thioglycollate in the generation of endogenous HOCl. The presence of HOCl within human atherosclerotic plaque has also been successfully verified with 8 (Figure 10, bottom). Due to the unmet medical need for preclinical diagnosis of atherosclerosis, the in-depth biological investigations of 8 offered a new window to monitor the impact of OCl– on the atherogenic process.

Figure 9.

Top: structure of 8 and its reaction with OCl–.

Figure 10.

Top: fluorescence reflectance imaging of hMPO-Tg mouse (A) preinjection; (B) the same animal postinjection of 8. Bottom: (a–i) images showing different sections incubated with 8 in the presence of HOCl within the human atherosclerotic plaque. For more details, see ref (15). Photographs courtesy of Joanna Shepherd. Reprinted with permission from ref (15). Copyright 2007 Science Direct.

Liver cancer has been considered one of the highest malignant cancers and ranked the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the world.5 Therefore, tools for the early diagnosis of liver cancer are imperative. To understand the role of HOCl in liver cancer pathogenesis, a galactose appended naphthalimide with p-aminophenylether as HOCl specific receptor (9) was reported by Zhang et al.5 The quenched nature of 9 (ΦF = 0.014) was due to the enhanced PET process as well as inhibition of ICT process occurring between the naphthalimide from p-aminophenylether moieties. The oxidative cleavage of the ether group in the presence of HOCl has resulted in an instant (within 3 s) “turn-on” response with ΦF = 0.143. The researchers strategically incorporated the pendant galactose moiety because of its hepatoma cell targeting specificity. The introduction of the galactose moiety increased the probe’s water solubility. Altogether, water solubility and noninterference from other analytes have developed 9 good candidates for bioimaging applications. It has been found that 9 can perform hepatoma-selective imaging of HOCl through asialoglycoprotein-receptor (ASGPR)-promoted endocytosis (Figure 11). The discrimination of hepatoma cells over other cancer cells human gastric carcinoma cells (MGC803), lung cancer (A549), and marrow neuroblastoma cells (SHSY5Y)) and the simultaneous tracing of endogenous HOCl levels in HepG2 cells have also been demonstrated with this probe (Figure 11). PMA and LPS pretreated HepG2 cells displayed strong green fluorescence after incubation with 9, as shown in Figure 11, bottom. However, the cells showed weaker fluorescence when treated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (Figure 11, bottom, right). However, endogenous imaging of HOCl in hepatoma cells by 9 constitutes the first report in this direction. The transient response of 9 towards HOCl and hepatoma selective fluorescent imaging has been considered a useful tool for studying various roles of HOCl in liver-related diseases.

Figure 11.

Top: structure of 9 and its reaction with HOCl. Bottom: left: fluorescence imaging of 9 in HepG2, MGC803, A549, and SHSY5Y cells. Right: fluorescence imaging in HepG2 cells incubated with 9. For more details, see ref (5). Reproduced from ref (5). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

As a vital organelle, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) plays a pivotal role in protein synthesis and maintaining a proper balance of intracellular calcium ions.16 However, improper folding of proteins leads to the accumulation of proteins in the ER cavity. Excessive accumulation of the proteins leads to ER stress, resulting in ROS production.16 Accordingly, HOCl, one of the ROS family’s crucial members, irreversibly disrupts the ER calcium homeostasis. It leads to cell dysfunction and even apoptosis. Therefore, to understand the biological role of HOCl in ER stress-related diseases, Gao et al. have documented a naphthalimide-based ER targetable two-photon fluorescence “turn-on” probe (10).16 The design of the probe has been based on anchoring p-aminophenyl ether as a HOCl specific receptor and methyl sulphonamide as an ER targetable moiety. The fast (within 60 s) fluorescence enhancement was attributed to the enhanced ICT process because HOCl promoted cleavage of the ether bond forming a hydroxyl ion in a 100% PBS solution (Figure 12, left). The high sensitivity, water solubility, low cytotoxicity, and biocompatibility of 10 have also been utilized for in-depth biological investigations of HOCl. The excellent overlap and Pearson’s coefficient of 10 with ER-Tracker Blue in colocalization imaging experiments demonstrated the ER targeting ability of 10 (Figure 12, right). Cell imaging of endogenous and exogenous HOCl was also successfully achieved via two-photon imaging in HeLa cells (Figure 13, left). However, fluorescence intensity diminished after NAC treatment (Figure 13, left). Encouraged by the results, the researchers also performed further imaging of enzymatically generated HOCl in HeLa cells using 10 (Figure 13, left). This has demonstrated the imaging sensitivity of the probe toward mild fluctuation of intracellular HOCl. Furthermore, Gao and his teammates sought to study the relation between ER stress and HOCl in HeLa cells (Figure 13, middle). They have found an increase in fluorescence intensity of 10 with an increase in the concentration of the ER stress inducer (tunicamycin). Thus, a direct relation between ER stress and HOCl has been established. In vivo imaging in zebrafish utilizing 10 has shown a promising feature in 10 (Figure 13, right). The excellent water solubility, rapid response time, and two-photon properties of the ER-targetable probe 10 make it a suitable candidate for studying the biological roles of HOCl in ER-stress-related diseases.

Figure 12.

Left: structure of 10 and its reaction mechanism with HOCl. Right: (A) two-photon imaging of HeLa cells coincubated with 10 collected from green channels; (B) blue channels; (D) bright field; and (C) merge images of panels A, B, and D. Colocalization plots of 10 and ER-Tracker Blue in HeLa cells (E, F). For more details, see ref (16). Reprinted with permission from ref (16). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Figure 13.

Left: two-photon bright field (a, d, g, j), green channel (b, e, h, k), and merged images (c, f, i, l) of 10 with different reagents in HeLa cells. Right: in vivo imaging in zebrafish utilizing 10. For more details, see ref (16). Reprinted with permission from ref (16). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

HOCl/OCl– Mediated Oxidative Deoximation Reaction of Oxime

Conversion of hydroxylamines to the corresponding aldehydes via a deprotection reaction with HOCl/OCl– is well-known in the literature (Scheme 1D).34 Fluorogenic compounds comprising unbridged C=N bonds are usually nonfluorescent due to C=N isomerization.34 Using this cascade strategy, Wu et al. have reported a “turn-on” BODIPY functionalized probe (11) for selective detection of OCl– in a PBS buffer solution (pH = 7.4).17 The predominant decay process of the excited states due to C=N isomerization led to the nonfluorescent nature of 11. As shown in Figure 14 (top), OCl– facilitated an oxidative deoximation reaction, i.e., oxidation of the C=N bond to the corresponding aldehyde resulted in the fluorescence enhancement of 11. The rapid (within 1 s) emission enhancement of 11 in the pH regime 7.1–8.3 signifies the detection of OCl– rather than HOCl. High photostability, quantum yield, and relatively strong emission at higher wavelengths make BODIPY a good candidate for bioimaging applications. Considering its superior property for biological purposes, strategically incorporated hydrophilic carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties in the BODIPY scaffold make 11 water-soluble. Thus, the low toxicity and water solubility of 11 have helped in the biological investigation of OCl– in live cells. The probe has been successfully explored to track exogenous OCl– in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. The successful demonstration of the detection of endogenously generated OCl– in enzymatically stimulated cells revealed the remarkable characteristics of the probe (Figure 14, bottom). The rapid response time, less excitation energy for the probe, low limit of detection (17.7 nM), and a detailed enzymatic assay of 11 in macrophage cells suggest its potential to become a suitable candidate to study biological roles of OCl–.

Figure 14.

Top: structure of 11 and its reaction with OCl–. Bottom: imaging of PMA-induced OCl– production in RAW264.7 cells. For more details, see ref (17). Reprinted with permission from ref (17). Copyright 2013 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Fluorogenic Probes Bearing HOCl/OCl– Specific Borane Moieties

A strategy based on nucleophilic oxidation of the C—B bond in aryl boronate into the hydroxyl moiety in the presence of OCl– was adopted by Yoon and co-workers to design and develop the OCl– specific fluorescent probe 12 (Scheme 1E).18 The reported OCl– probe was based on a “dual-lock” fluorescein molecule wherein the aryl boronate group is coupled with a thiolactone moiety. Among the ROS/RNS; H2O2, ONOO®, and OCl– are known to oxidize the arylboronate system. Since H2O2 and OCl– are closely related in their enzymatic pathways, detection of OCl– in the presence of H2O2 is a critical task. However, due to the “dual-lock” strategy and OCl– being a much stronger oxidizing agent, 12 possesses the potential to react with aryl boronate as well as hydrolyze the thiolactone ring to afford the ring-opened fluorescein. Accordingly, strong green fluorescence has been observed on excitation of the probe at 498 nm in the presence of OCl– (Figure 15, top). Other ROS/RNS failed to show any optical changes. The high selectivity and sensitivity of 12 were further utilized for bioimaging microbe-induced HOCl production in the mucosa of the Drosophila gut system. The Drosophila gut system is a well-known HOCl-producing organ in which HOCl is made in response to bacterial invasion. Therefore, the flies were initially subjected to oral ingestion of bacterial extracts before in vivo HOCl imaging. Probe 12 successfully carried out the biological investigations of PLCβ-DUOX-dependent HOCl productions in the Drosophila gut system. Later it was also explored successfully to image bacterial-induced HOCl production, as shown in Figure 15, bottom. The dual-lock strategy and detailed investigations of 12 for in vivo imaging of HOCl production in animals make it a promising tool among other reported probes.

Figure 15.

Top: structure and reaction mechanism of 12 with OCl–. Bottom: detection of DUOX-dependent HOCl induction in the intestinal epithelia of Drosophila. For more details, see ref (18). Reproduced from ref (18). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

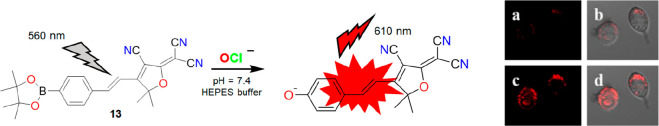

Following similar chemistry of aryl boronate with HOCl, Zhu et al. reported a 2-dicyanomethylene-3-cyano-4,5,5-trimethyl-2,5-dihyrofuran (TCF) containing far-red fluorescent probe 13 for selective detection of OCl– in a 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer solution (pH = 7.4).19 TCF has been known for its higher emission wavelength, which is highly preferred for cellular studies. Therefore, probe 13 was designed by employing a TCF moiety with an OCl– targeting the aryl boronate group. Probe 13 displayed a highly “turn-on” spectral response for OCl– over other ROS/RNS at 610 nm due to the ICT pathway (Figure 16, left). The production of a strong electron-donating O atom from aryl boronate on interaction with OCl– resulted in a charge transfer phenomenon from the O atom to the electron withdrawing TCF scaffold. The advantageous properties of 13, such as high emission wavelength (610 nm), water solubility, and rapid response time (within 1 min), were used for imaging exogenous OCl– in live RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Figure 16 clearly depicts the potential of 13 for successful imaging of OCl– in live RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Albeit for 13, with excellent selectivity and a rapid response feature exhibiting a red emission in live RAW264.7 macrophage cells, more detailed biological investigations with OCl– in various cell lines could make it a more promising candidate.

Figure 16.

Left: structure and reaction mechanism of 13 with OCl–. Right: images of RAW264.7 macrophage cells stained with 13 in absence (a, b) and presence (c, d) of OCl–. Reprinted with permission from ref (19). Copyright 2015 Elsevier.

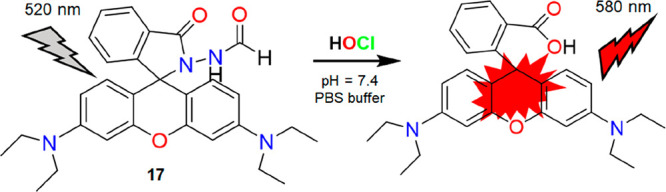

HOCl/OCl– Mediated Ring Opening

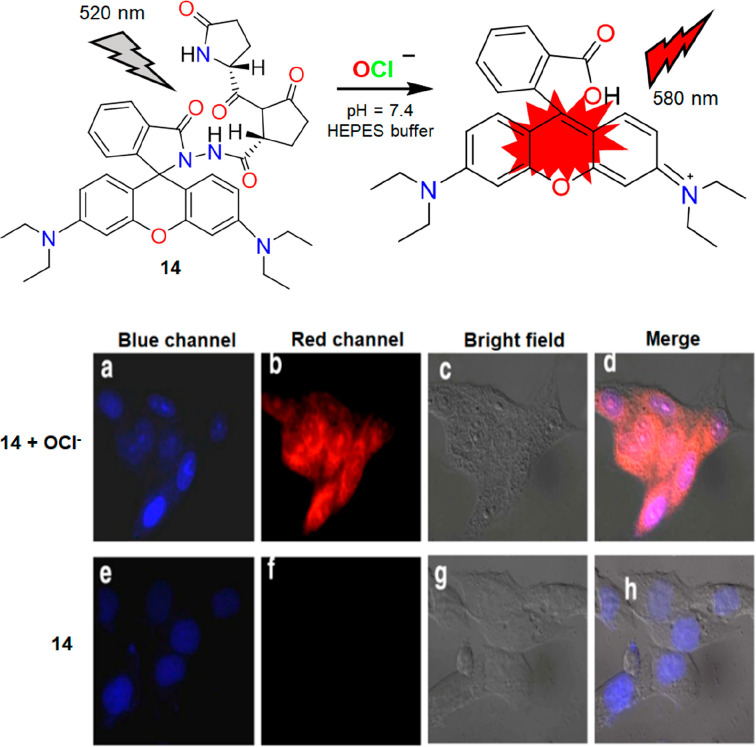

Because of its high quantum yield, red emissive nature, and excellent spirolactam ring “open-close” properties, rhodamine framework-based systems are widely used for biological applications of an OCl– specific system.20 By employing the oxidation property of OCl–, Goswami et al. developed rhodamine-based fluoro-chromogenic chiral probe 14 for nanomolar detection of OCl– in aqueous HEPES buffer solution (pH = 7.4). A “turn-on” fluorescence response was observed due to OCl– mediated oxidation of 14 and subsequent hydrolysis of the diimide intermediate product. Oxidation of 14 resulted in the opening of the spirolactam ring, which altered fluorescence intensity at 580 nm (Figure 17, top). The high selectivity of 14 towards OCl– over a pH range between 7 and 10.5 was due to the introduction of the triketo chiral moiety (S)-(−)-2-pyrrolidone-5-carboxamide acid containing. Rapid response time (within 2 min), water solubility, and high selectivity toward OCl– among other competitive ROS/RNS species encouraged the authors to visualize exogenous OCl– in live HeLa cells. As shown in Figure 17 (bottom), cell membrane permeable 14 shows a red fluorescence in the cytoplasm of the cells. However, 14 with long excitation wavelength, excellent selectivity with a nanomolar detection limit (1.4 nM) toward OCl–, use of HEPES buffer medium for detection purpose poses a drawback to this system.

Figure 17.

Top: structure and reaction mechanism of 14 with OCl–. Bottom: fluorescence images of HeLa cells incubated with 14 in the presence (a–d) and absence (e–h) of OCl–. Reproduced from ref (20). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

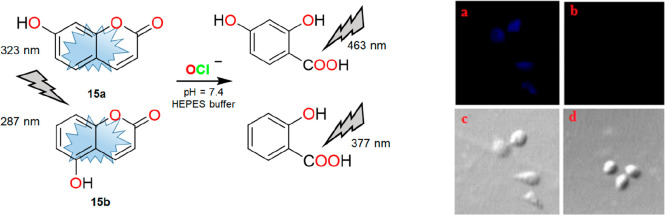

Huo et al. reported two highly selective fluorogenic probes, 15a and 15b, for selective detection of OCl– in the HEPES buffer medium (pH = 7.4).9 Being a strong oxidant, OCl– oxidized the ethylenic bond of coumarin to form a carboxyl product. Subsequent hydrolysis of the intermediate has resulted in the final product, as shown in Figure 18. The oxidized ring-opening reaction and hydrolyzed products were confirmed by NMR and electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS analyses. The rapid response behavior of the probes toward OCl– offered the researchers for bioimaging applications. Probe 15a was found to visualize OCl– in live HepG2 cells. As shown in Figure 18 (right), 15a showed good cell permeability to detect OCl– within the cells. The “turn-off” nature and use of HEPES buffer medium for detection purposes of OCl– are the major drawbacks of the system. Therefore, 15a and 15b cannot be considered suitable candidates to study the biological roles of OCl– in cells.

Figure 18.

Left: structure and interaction of 15a and 15b with OCl–. Right: fluorescence image of HepG2 cells with 15a (a and c) and after treatment with NaOCl (b and d). Reprinted with permission from ref (9). Copyright 2016 Elsevier.

The importance of a suitable buffer medium in detecting HOCl was explained in the communication of Xing and co-workers.21 The authors proposed that the HEPES buffer is unsuitable in HOCl detection as HEPES behaves as a HOCl scavenger. Higher fluorescence enhancement of 16 in PBS than a HEPES buffer at 516 nm further confirms the hypothesis proposed by Xing et al. The authors also suggested avoiding a tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane buffer solution for HOCl detection. Furthermore, increasing the current in the difference pulse voltammetry (DPV) for HEPES and tris buffers suggested the nonsuitability of the buffer media for HOCl. Utilizing the oxidation property of HOCl, a fluorescein platform containing an azo moiety was developed for selective detection of HOCl in the PBS buffer medium (Figure 19, left). The quick response, water solubility, and high emission wavelength made the probe a good candidate for bioimaging HOCl in living cells. Accordingly, imaging of exogenous HOCl in HeLa cells was achieved with 16. Imaging results inspired authors to take a step forward in detecting HOCl in the living mouse. As shown in Figure 19 (right), the fluorescence intensity increases gradually inside the mouse on the reaction of HOCl with 16. Therefore, 16 can be a potential tool for real-time imaging of endogenous HOCl. The choice of a proper buffer medium for the detection of ROS/RNS with convincing evidence has remained the highlight of this work. The excellent selectivity, long excitation wavelength, rapid “turn-on” response, and excellent bioimaging properties of 16 make it an excellent candidate for studying the biological roles of intracellular HOCl.

Figure 19.

Left: structure and mechanism of 16 with HOCl. Right: fluorescence images of live mice. Subcutaneous injection of a solution of PBS buffer (control), followed by subcutaneous injection of a solution of 16 and then a solution of HOCl. Reprinted with permission from ref (21). Copyright 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry.

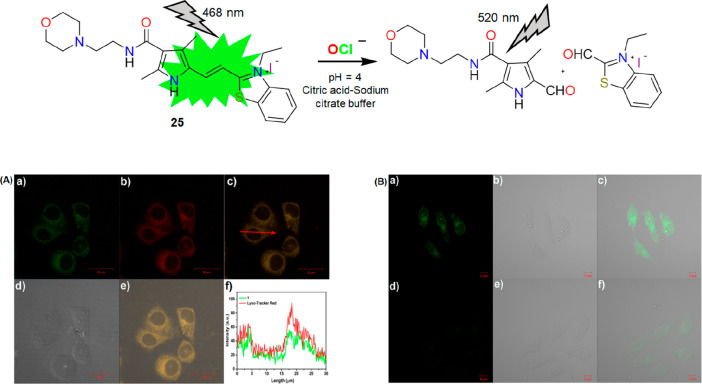

Utilizing the remarkable photophysical properties of the rhodamine dyes, Sheng and co-workers developed a formylhydrazine-based receptor for HOCl recognition in a PBS buffer (pH = 7.4).22 The nonfluorescent nature of 17 was due to the closed spirocyclic structure of the rhodamine moiety. HOCl induced oxidative cleavage of the formylhydrazine moiety, which then led to the opening of the spirolactam ring resulting in the enhancement of red fluorescence within 3 s (Figure 20). The desirable features and high selectivity of 17 toward HOCl over other ROS/RNS motivated the authors to pursue in-depth studies of the probe in biological environments. Intracellular basal HOCl was monitored by treating 17 for 30 min in RAW264.7 macrophages. The macrophages treated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) showed a decrease in fluorescence, whereas enzymatically generated and exogenous HOCl displayed a similar “turn-on” fluorescence. Thus, probe 17 possesses the ability to trace intracellular basal HOCl without external stimuli. To distinguish basal HOCl in normal cells (HUVEC and RAW264.7) and cancer cells (HeLa, A549, and HepG2), 17 was successfully employed (Figure 21, left). The bioimaging applications of 17 were also studied by the researchers upon measuring HOCl in living animals. The zebrafish loaded with 17 displayed an apparent fluorescence enhancement in the presence of HOCl. However, NAC-induced zebrafish showed a lower fluorescent response (Figure 21, right). Therefore, probe 17 appears to be a potential candidate for accurately monitoring HOCl in complex biological systems. The ultrasensitive detection limit (0.116 nM) with red emissive properties of 17 toward HOCl and the probe’s potential to distinguish cancer cells from normal cells are impressive.

Figure 20.

Structure of 17 and its proposed reaction mechanism with HOCl.

Figure 21.

Left: fluorescence images of live HUVEC, RAW264.7, HeLa, A549, and HepG2 cells treated with 17. Right: bright field, fluorescence and merged images of zebrafish with 17 with different reagents. For more details, see ref (22). Reproduced from ref (22). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

It has been well-known that mitochondria are the primary source of ROS in most cells, including OCl–.23 Accordingly, monitoring of OCl– is imperative to unravel its diverse physiological and pathological functions. Considering the significance of mitochondrial OCl–, Shen and co-workers reported mitochondria targeting red emitting fluorogenic probes to monitor the production of endogenous OCl– in macrophage cells and mice.23 The incorporation of the quaternary N-containing pyridine group in the rhodamine scaffold facilitated the probe’s (18) mitochondria targeting ability (Figure 22, left). Upon interaction with OCl–, an open form of rhodamine showed a signal at 637 nm within 10 s. The authors have also studied OCl– in biological environments. Figure 22 (right) shows that endogenously generated OCl– in RAW264.7 macrophages can be observable by 18. The fluorescence of 18 decreased drastically in NAC (a scavenger of OCl–) incubated cells. The colocalization experiment was successfully performed to evaluate the subcellular distribution of 18 by utilizing MitoTracker Deep Red (Figure 23, top). Encouraging results prompted the authors to test 18 for endogenously induced OCl– monitoring in Kunming mice. As evident from Figure 23 (bottom), a “turn-on” fluorescence in the right leg of the mouse inferred the potential of 18 in the imaging of endogenously generated OCl– in the living mouse. The ultrasensitive detection limit (0.9 nM) of the far-red mitochondria targeting probe 18 toward OCl– can provide a good platform for imaging OCl– in mitochondria, which are biologically significant.

Figure 22.

Left: structure of 18 and its mode of reaction with OCl–. Right: (a, c, and e) bright field and (b, d, and f) fluorescence images of endogenously produced OCl– in RAW264.7 cells using 18. Reprinted with permission from ref (23). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

Figure 23.

Top: (a–d) images of RAW264.7 cells costained with 18 and MitoTracker Deep Red; (e) intensity scatter plot red and green channels. Bottom: representative fluorescence images (a–f) of endogenous OCl– in Kunming mice. For more details, see ref (23). Reprinted with permission from ref (23). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

HOCl/OCl– Promoted Other Oxidative Reactions

In 2018, Zhu and co-workers reported an OCl– specific fluorescent probe (19), which localizes itself inside mitochondria.24 The probe could monitor the basal OCl– level in the mitochondria without exogenous stimuli. The fluorescence intensity of 19 at 672 nm decreases rapidly with the addition of OCl–. Moreover, the insignificant change in the fluorescence intensity of 19 at pH 5 after the addition of OCl– established the detection of OCl– rather than HOCl. The oxidation of amido-to-nitroso by OCl– (Scheme 1F) was attributed to the specificity of 19 toward OCl– in basic conditions (Figure 24, top). Intracellular red fluorescence after 20 min of incubation of 19 in HeLa cells was evident in Figure 24 (bottom, A). However, after pretreatment of HeLa cells with ABAH, high fluorescence was displayed (Figure 24, bottom, A). HeLa cells pretreated with PMA showed a weak fluorescence confirming the generation of OCl–. The authors have successfully applied 19 to track the exogenous OCl– in living RAW 264.7 macrophages. From Figure 24 (bottom, B), the synchronous fluorescence of the probe with commercial MitoTracker Green confirmed the accumulation of 19 in the mitochondria of living cells. Figure 24 (bottom, B) showed successful tracking of OCl– fluctuations in the mitochondria of living HeLa cells and RAW264.7 macrophages. Albeit 19 can detect basal OCl– at mitochondria with a detection limit of 10.8 pM, the “turn-off” response of 19 toward OCl– limits its real-time intracellular bioimaging applications.

Figure 24.

Top: structure of 19 and its proposed mechanism of interaction with OCl–. Bottom: (A) fluorescence images of (a) living HeLa cells incubated with 19; (b) HeLa cells incubated with 19 after preincubation with ABAH; (c) HeLa cells incubated with 19 after preincubation with PMA; (d) HeLa cells incubated with 19 after preincubation with NaOCl. (B) (a–d) Images of living HeLa cells coincubated with 19 and MitoTracker Green; (e, f) intensity scatter profiles of red and green channels. For more details, see ref (24). Reprinted with permission from ref (24). Copyright 2018 Elsevier.

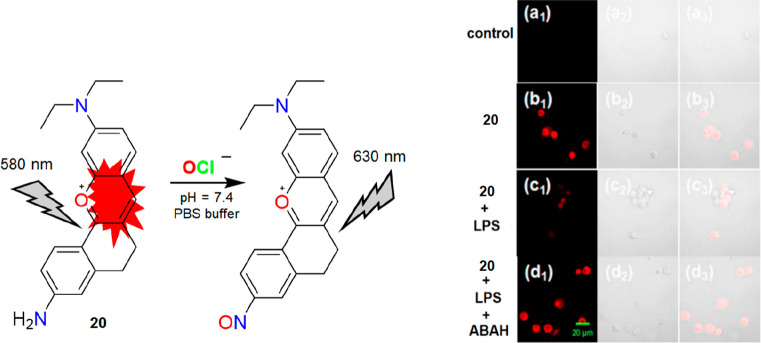

Following a similar trend, Zhou and co-workers developed a water-soluble red emitting xanthene-based fluorescent probe (20) for rapid detection of OCl– with high specificity over other ROS/RNS.25 The probe was strategically designed to oxidize the amide group into nitroso using the oxidative property of OCl– (Figure 25, left). This, in turn, resulted in a charge transfer process leading to an alteration in the optical properties. An insignificant emission change of 20 in the presence of OCl– at pH 5 confirms its detection ability at physiological pH. This further motivated the researchers to track enzymatically generated OCl– as well as exogenous OCl– in PC12 cells. As shown in Figure 25 (right), probe 20 can detect enzymatically generated OCl– by showing a “turn-off” response. The red fluorescence of 20 was recovered when the cells were pretreated with OCl– inhibitor ABAH. Finally, 20 was also used to track exogenous OCl–. There is no doubt that 20 can serve as a promising tool for OCl– detection with a nanomolar detection limit (2.41 nM). However, the quenching nature of 20 toward OCl– poses a major drawback in bioimaging applications.

Figure 25.

Left: structure of 20 and its mode of reaction with OCl–. Right: confocal microscopic images of enzymatically generated OCl– (produced by LPS) in PC12 cells. For more details, see ref (25). Reprinted with permission from ref (25). Copyright 2019 Elsevier.

Song et al. utilized a similar protocol by reporting an OCl– specific NIR probe 21 (Figure 26, top).26 The probe showed a strong fluorescence response after the pretreatment of HepG2 cells with ABAH. The results indicated the successful detection of basal OCl– (Figure 26). Furthermore, the addition of exogenous OCl– weakened the fluorescence of the cell. Therefore, the observations suggested that 21 is a potential probe for monitoring the fluctuations of intracellular OCl–. However, the long response time (10 min) accompanied by a “turn-off” response possess limitations in bioimaging applications of 21.

Figure 26.

Top: molecular structure of 21 and its mechanism of reaction with OCl–. Bottom: (a–d) images of 21 in living HepG2 cells. For more details, see ref (26). Reprinted with permission from ref (26). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

HOCl-promoted triazolo formation was reported by Tang and co-workers.27 The authors have developed a rhodol-based mitochondria-targeted HOCl specific fluorescent probe (22). HOCl-triggered triazole ring formation is fast and eco-friendly. The triphenylphosphine moiety was appended with 22 to make the probe mitochondria targeting. A significant “turn-on” fluorescence of 22 upon addition of HOCl (Figure 27, top) was observed. However, other competitive species and ROS/RNS failed to elicit any optical changes with HOCl. The excellent selectivity, rapid response (4 s), water compatibility, and anti-interference ability of 22 prompted the authors to utilize it as a potential tool for biological investigations of intracellular HOCl. It was found that 22 can image exogenous HOCl in the HepG2 cell line (Figure 27A, bottom). Figure 27B demonstrates the ability of 22 in the visualization of endogenous HOCl in living cells. A good Pearson’s correlation coefficient (0.94) of 22 with MitoTracker Green concluded the mitochondrial imaging of HOCl in living cells (Figure 28, left). Probe 22 can also be used to image the endogenous HOCl in zebrafish (Figure 28, right). The excellent physicochemical property of the rhodol-based mitochondria targeting probe toward HOCl thus can be a potential candidate for visualization of HOCl in live cells.

Figure 27.

Top: structure of 22 and its reaction mechanism with HOCl. Bottom: (A) fluorescence imaging of exogenous HOCl in HepG2 cells using 22. (B) Fluorescence imaging of endogenous HOCl in HepG2 cells using 22. For more details, see ref (27). Reprinted with permission from ref (27). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Figure 28.

Left: fluorescence imaging of HepG2 cells costained with 22 and MitoTracker Green, ERTracker Green, LysoTracker Green, and GolgiTracker Green along with HOCl. Right: fluorescence imaging of endogenous HOCl in zebrafish using 22. For more details, see ref (27). Reprinted with permission from ref (27). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Jia and HuiMin designed a FRET-based water-soluble probe (23) for selective detection of HOCl in a PBS buffer (pH = 7.4).28 The dansyl moiety was attached to a rhodamine scaffold, which acts as a FRET acceptor. HOCl selective N′-acylsulfonohydrazide links the two fluorophores. Upon addition of HOCl, the N′-acylsulfonohydrazide bridge cleaved, which resulted in the decrease of FRET efficiency and an increase in the fluorescence of the donor at 501 nm (Figure 29, top). Moreover, the charge on the rhodamine moiety enabled 23 to be water-soluble, successfully used in the fluorescence imaging of ex vivo HOCl in HeLa cells. As shown in Figure 29 (bottom), the fluorescence intensity of 23 inside cells gradually increased after incubation with NaOCl. Since HOCl is highly reactive and short-lived in biological systems, the long response time of 23 toward HOCl does not make it a suitable candidate for bioimaging applications.

Figure 29.

Top: structure of 23 and its reaction mechanism with HOCl. Bottom: fluorescence imaging of HOCl in (a) HeLa cells only; (b) HeLa cells treated with 23; (c) 23 loaded HeLa cells incubated with NaOCl for 15 min; (d) for 30 min. For more details, see ref (28). Reprinted with permission from ref (28). Copyright 2011 Elsevier.

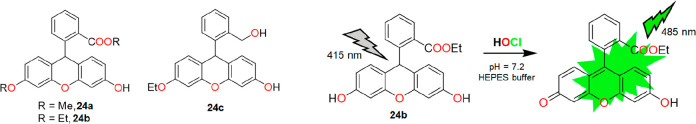

In 2012, a series of water-soluble dihydrofluorescein-based probes were reported by Yao and co-workers.29 The probes 24a–c (Figure 30) work in a 100% HEPES buffer medium (pH = 7.2) and were designed specifically based on the HOCl-promoted oxidation reaction. A distinct photo switch of the nonfluorescent deconjugated form to a highly fluorescent conjugated form was observed during the interaction of the probe with HOCl. 24b resulted in a 1643-fold fluorescence enhancement at 485 nm (ΦF = 0.71). High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-MS characterized the oxidized product. However, the auto-oxidation tendency of the probes upon exposure to an aerial HEPES buffer solution was noticed. 24c was found relatively more stable than the other two compounds for more than 48 h. 24b was the best and was further exploited by the authors to detect in situ production of HOCl in NIH3T3 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast cells). Incubation of the probe in a pretreated MPO enzymatic system for 30 min yielded negligible fluorescence, as shown in Figure 31. However, the intracellular fluorescence intensity of the same cell was significantly enhanced after adding H2O2 (Figure 31A). The MTT assay confirmed the nontoxic nature of the probe. Nontoxicity, cell permeability, and in vivo high performance enabled the probe for exogenous tracking of HOCl in 3 month old zebrafish (Figure 31B). As depicted in Figure 31C, the incremental fluorescence intensity inferred the highest degree of accumulation in the gall bladder, followed by the intestine, eye, liver, and egg. However, the use of reductive HEPES buffer for detection purposes and long response time are the few drawbacks of this system.

Figure 30.

Left: molecular structures of 24a, 24b, and 24c. Right: reaction mechanism of 24b with HOCl.

Figure 31.

Top (A): (a–e) images of NIH3T3 cells preincubated with NaOCl and 24b in MPO; (f) average emission intensities of cells. Top (B): (a–e) bright field and fluorescence microscopy images of AB/Tubingen larvae zebrafish incubated with HOCl (E3 embryo media) during the development. Bottom (C): images of isolated organs of zebrafish were analyzed. For more details, see ref (29). Reprinted with permission from ref (29). Copyright 2012 Royal Society of Chemistry.

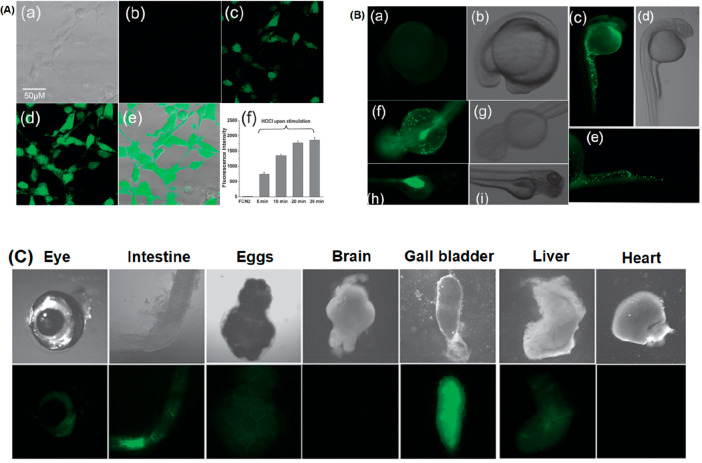

C=C bonds are susceptible to oxidation by OCl– (Scheme 1G). In 2020, Xu et al. reported the cleavage of the C=C bond of a morpholine functionalized pyrrole-cyanine probe (25) by OCl–.30 The green emission of 25 was decreased within 30 s due to the oxidation of the C=C bond (Figure 32, top). The oxidation inhibited the ICT process occurring in the probe in the absence of OCl–. The morpholine moiety was strategically incorporated to target the lysosome. A colocalization study of 25 with LysoTracker Red showed an overlap coefficient of 0.83 (Figure 32, bottom A). Furthermore, the authors have also performed the bioimaging of exogenous lysosomal OCl– in HeLa cells (Figure 32, bottom B). The “turn-off” response of 25 toward OCl– further restricts the probe from becoming a suitable candidate for imaging purposes.

Figure 32.

Top: molecular structure of 25 and its proposed reaction mechanism with OCl–. Bottom left (A): fluorescence images of HeLa cells stained with 25 (a) and LysoTracker Red (b); merged images of HeLa cells stained with 25 and LysoTracker Red (c), bright field images of HeLa cells stained with 25 (d), and intensity profile across the HeLa cell costained with LysoTracker Red and the green channel of 1 (f). Bottom right (B): (a–f) confocal, bright field, and overlay images of Hela cells incubated with 25 in the absence and presence of OCl–. For more details, see ref (30). Reprinted with permission from ref (30). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Yin’s group has also followed a similar strategy to report a nonfluorescent OCl– specific probe (26).31 The introduction of a pyrazoline ring on the coumarin framework and a hydroxyl group in the 4-position of the dye led to a synergistic effect, which presumably activated the coumarin lactone ring. The C=C bond of the coumarin moiety cleaved, leading to a “turn-off” response upon reaction with OCl– under physiological conditions (Figure 33, top). Bioimaging of 26 inside HeLa cells showed a green fluorescence when cells were pretreated with NAC (a scavenger of OCl–, Figure 33, bottom A). Upon addition of OCl–, the green fluorescence was quenched (Figure 33, bottom A). Similar quenching was also observed when OCl– was added to zebrafish (Figure 33, bottom B). Therefore, 26 is not suitable as a potential candidate for biological studies.

Figure 33.

Top: molecular structure of 26 and its reaction mechanism with OCl–. Bottom A: (a–l) bright field, fluorescence, and merged images of HeLa cells after incubation with NAC, 26, and LPS. Bottom B: bright field (a, d, g, and j), fluorescence (b, e, h, and k), and merged images (c, f, i, and l) of zebrafish recorded after incubation with 26 without and with OCl–. For more details, see ref (31). Reprinted with permission from ref (31). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

Recently, ratiometric probes have proven to be more fruitful for biological applications due to their accurate detection ability to reduce measurement error.32 Considering the requirement of HOCl specific water-soluble ratiometric probe for bioimaging purposes, a NIR ratiometric fluorescent probe (27) was reported by Ni and co-workers in 2020.32 The probe was designed by attaching a malononitrile derivative to a coumarin scaffold via an alkene bond (Figure 34, top). It exhibited a red fluorescence at 713 nm due to FRET. The addition of HOCl/OCl– to the solution of 27 interrupted the extended π conjugation, resulting in the disruption of the FRET process. As a result, a new peak appeared at 496 nm with a concomitant decrease of the 713 nm peak, and thus, an isosbestic point at 600 nm emerged. With the excellent ratiometric NIR characteristic features of 27, it was further investigated in the bioimaging of HOCl inside HeLa cells. The successful demonstration of the imaging of both exogenous and endogenous HOCl in enzymatically stimulated was remarkable (Figure 34, bottom). Therefore, the ratiometric nature of the NIR probe is highly preferable to study the biological roles of HOCl in live cells.

Figure 34.

Top: molecular structure of 27 and its reaction mechanism with HOCl. Bottom: fluorescence images of untreated and treated HeLa cells. For more details, see ref (32). Reprinted with permission from ref (32). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Again, based on HOCl-promoted oxidative cleavage of the C=C bond, Li et al. reported an OCl– specific ratiometric fluorescent probe.33 A color change of 28 from red to orange was observable by the naked eyes upon the addition of OCl–. The HOCl-induced oxidative cleavage of the C=C functionality resulted in a strong emission at 567 nm, which is responsible for a discernible color change under UV illumination. As mentioned earlier, boron BODIPY, a fantastic fluorophore, is highly suitable for biological investigations because of its high molar absorption coefficient, strong fluorescence emission, and high quantum yield. The quaternary ammonium moiety endowed the probe with excellent water solubility. The fluorescence imaging of 28 in L929 cells suggested easy cell permeability of the probe. The probe can detect OCl– in a ratiometric mode (Figure 35). The time-dependent studies of 28 in the presence of OCl– showed the enhancement of the green channel with a slight increase of red fluorescence intensity (Figure 35). The results suggested the real-time feasibility of 28 in recognizing exogenous OCl– in living cells (Figure 36A). Probe 28 also successful in imaging enzymatically generated endogenous OCl– inside L929 cells (Figure 36B). The remarkable features of 28 enabled further monitoring of subcellular-targeted hypochlorite fluctuations via costaining with commercial MitoTracker Green and LysoTracker Green. The colocalization coefficient indicated better overlapping of 28 with the MitoTracker agent. Therefore, 28 has a higher localization ability in mitochondria, as shown in Figure 36C. With all these promising features, 28 can be used as a powerful tool to detect OCl– in biological samples.

Figure 35.

Molecular structure of 28 and its proposed reaction mechanism with OCl–.

Figure 36.

Top left (A): (1–4) confocal fluorescence images of 28 inside living L929 cells with the increasing exogenous HOCl (1, 0.075 equiv; 2, 0.15 equiv; 3, 0.6 equiv; 4, 1.5 equiv). Top right (B): (1–3) confocal fluorescence imaging of L929 cells upon treatment with LPS (1, 0 μg/mL; 2, 1 μg/mL; 3, 2 μg/mL) for 12 h, then probe 28 for 30 min. Bottom (C): colocalization images of 28 with (a) MitoTracker Green FM and (b) LysoTracker Green DND in L929 cells (1, bright field; 2, red chanel; 3, green chanel; 4, overlay images of 1 and 2; 5, intensity correlation plots). For more details, see ref (33). Reprinted with permission from ref (33). Copyright 2019 Elsevier.

Key Factors while Designing Water-Soluble Fluorescent Probes for HOCl/OCl–

Water is the solvent for life. To elucidate intracellular biological functions of HOCl/OCl–, 100% water-soluble probes are highly desirable, i.e., no use of organic solvents for the analysis is allowed. Organic solvents tend to destroy the normal functions of the cells. For example, DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) is not suitable for detecting HOCl/OCl–, as it can be readily oxidized, leading to inaccurate results.21 Therefore, proper design of the probes is required to develop HOCl/OCl– selective chemosensors, which possess a higher degree of water solubility for tracking intracellular HOCl/OCl–. Yoon and co-workers have clearly mentioned it in their seminal contribution that HOCl/OCl– can oxidize HEPES.1 Hence, it acts as a scavenger of HOCl/OCl– and provides inaccurate results or wrong information regarding the actual concentrations of HOCl/OCl–.21 Thus, one should avoid the use of HEPES buffer. Another concerning factor is the probe’s diffusion through the cell membrane, which should be taken care of while developing intracellular water-soluble probes for HOCl/OCl–. In the case of monitoring the biochemistry of HOCl/OCl–, the design and development of probes that bear cell organelle targeting motif(s) is another significant challenge in this domain.23,24,27,30 At 25 °C, the pKa of HOCl is 7.53.2 Therefore, under physiological conditions (pH = 7.4), HOCl and OCl– coexist in equilibrium. Accordingly, a proper technique for discrimination of OCl– and HOCl is extremely desirable. Furthermore, HOCl/OCl– with strong oxidization properties is highly reactive and short-lived under physiological conditions. It is imperative to develop HOCl/OCl– specific fluorogenic probes that would function instantly at the physiological pH regime. Literature scrutiny reveals that probes 9, 17, 19, and 21 can monitor native OCl– in live HeLa or HepG2 (cancerous) cells without external stimuli. Although, reports suggest the absence of MPO in these cell lines. The generation of OCl– is presumably due to the activated growth receptor [RTKs (receptor tyrosine kinases)] signaling cascades, including activation by platelet-derived growth factor, cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, γ-interferon, and interleukins (ROS inducers).35

Conclusions and Outlook

This mini-review summarizes the development of 100% water-soluble HOCl/OCl– specific fluorogenic probes to be helpful in biology. An overview of various design principles and their detection mechanisms with HOCl/OCl– to modulate spectral responses has been presented. Another critical aspect of this mini-review is highlighting in vitro and in vivo biological applications of fluorescent probes in living cells and animals. In this regard, several probes have been reported over the past decade, which has been applied for bioimaging or diagnostic purposes. Despite a few impressive examples (Table 1), many reported probes do not meet the qualifying criteria to be ideal for HOCl/OCl– sensing, as stated earlier. Since HOCl/OCl– is highly reactive in biological environments, probes with a rapid response are apparent. However, probes 21, 23, and 24b failed to meet the criteria, thus limiting their real-time use in biological systems. Even probes 6, 15, 19, 20, 21, 25, and 26 with a “turn-off” nature are unsuitable for bioapplications. Therefore, selecting a proper fluorogenic framework anchored with the recognition unit is highly desirable for fluorescence amplification. HOCl/OCl– is/are biologically relevant species. Therefore, probes with long emission wavelengths such as far red NIR or NIR-II emissive dyes will work better in studying HOCl/OCl– by minimizing cellular autofluorescence. Thus, probes 3, 8, 13, 18, 19, 27, and 28 are successful in this regard. Ratiometric probes, which are considered superior to simple “turn-on” fluorogenic probes, are largely unexplored in this domain. The NIR-I probe has the issue of autofluorescence. It poses a limitation for tissue penetration. As a suitable alternative, NIR-II probes (1000–1700 nm) showed an improved signal-to-noise ratio and can be considered to explore deep tissue information. However, 100% water-soluble probes with NIR-II characteristics for detecting HOCl/OCl– properties have not yet been reported.

Table 1. Representative Fluorogenic Probes (100% Water-Soluble) for Bioimaging of Hypochlorite/Hypochlorous Acid in Cells and Organisms.

| Probe | λex and λem | Buffer/pH | Technique/Response time | Biological application | Advantage | Disadvantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 520 and 541 | Sodium phosphate/7.4 | Turn-on/2 min | Imaging of enzymatically stimulated HOCl production in RAW264.7 cells | Higher excitation wavelength, 1079-fold enhancement | Small interference from ONOO– | (3) |

| 2a and 2b | 405 and 480 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/within few seconds | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in NIH3T3 and endogenous OCl– in RAW264.7 macrophages, HL-60 human progranulocytic leukemia cell lines, respectively | Response time, LOD = 10 nM | Blue emission hampering cellular autofluorescence | (6) |

| 3 | 690 and 786 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/100 s | Imaging of exogenous and endogenous HOCl in living mice | Low energy excitation, NIR probe, response time | Synthetic procedure | (12) |

| 4 | 542 and 560 | Water/7–10 | Turn-on/5 min | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells | Emission at red region | Long response time | (4) |

| 5 | 400 and 503 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/within few seconds | Imaging and biological investigations of endogenously generated OCl– in RAW264.7 cells, evaluation of anti-inflammatory effects of Sec and MTX in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, imaging of OCl– in an osteoarthritic mouse model | Response time, LOD = 16.1 nM | (10) | |

| 6 | 405 and 505 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-off/150 s | Imaging of OCl– in MCF-7 cells, comparison study between one-photon and two-photon imaging techniques in 4T1 cells, lysotracking investigations | Two-photon probe for detection of lysosomal OCl– | Turn-off | (13) |

| 7 | 325 and 488/600; 488 and 595 | PBS/7.4 | Ratiometric/NA | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in L929 cells | Ratiometric, LOD = 38 nM | Tedious synthetic procedure | (14) |

| 8 | 614 and 676 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/NA | Imaging of endogenous HOCl produced by neutrophils in experimental murine peritonitis and MPO expressing cells in human atherosclerotic arteries | Less energy for excitation, far-red emissive probe, in-depth bioimaging studies | (15) | |

| 9 | 470 and 558 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/3 s | Hepatoma selective imaging of HOCl, imaging of endogenous HOCl in HepG2 cells | Hepatoma cell selective fluorescent probe, LOD = 0.46 nM | (5) | |

| 10 | 450 and 550 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/60 s | Two-photon imaging of exogenous and endogenous HOCl in HeLa cells, ER tracking studies with ER stress inducer tunicamycin, in vivo imaging in zebrafish | Organelle specific probe, two-photon imaging, LOD = 6.2 nM | (16) | |

| 11 | 500 and 525 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/within 1 s | Imaging of exogenous and endogenous OCl– in RAW264.7 cells | Less energy for excitation, LOD = 17.7 nM | (17) | |

| 12 | 498 and 523 | KH2PO4/7.4 | Turn-on/1 min | Visualization of microbe-induced HOCl production in the mucosa of Drosophila | Detail biological investigations | (18) | |

| 13 | 560 and 610 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/within 1 min | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in RAW264.7 cells | Far-red emission probe | (19) | |

| 14 | 520 and 580 | HEPES/7.4 | Turn-on/within 2 min | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in HeLa cells | Red emission property, LOD = 1.4 nM | HEPES buffer | (20) |

| 15a and 15b | 323/287 and 463/377 | HEPES/7.4 | Turn-off/9 and 17 s | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in HepG2 cells | LOD = 56.8 nM | Turn-off, HEPES buffer | (9) |

| 16 | 485 and 516 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/2 min | Imaging of exogenous HOCl in HeLa cells and in living mouse | Long excitation wavelength, LOD = 8.7 nM | (21) | |

| 17 | 520 and 580 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/within 3 s | Monitoring basal HOCl in live cells and zebrafish, visualization in distinguishing cancer cells (HeLa, A549, and HepG2) from normal ones. (RAW264.7 and HUVEC) | Long excitation wavelength, response time, LOD = 0.11 nM | (22) | |

| 18 | 580 and 637 | PBS/8 | Turn-on/10 s | Visualization of endogenously generated OCl– in Kunming mouse and RAW264.7 cells, mito-tracking investigations | Mitochondria targeting, long excitation and emission wavelength, response time, LOD = 0.9 nM | (23) | |

| 19 | 600 and 672 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-off/5 s | Tracking OCl– in mitochondria of living HeLa cells, imaging of exogenous OCl– in RAW264.7 cells | Mitochondria targeting, long excitation wavelength, LOD = 10.8 pM | Turn-off | (24) |

| 20 | 580 and 630 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-off/10 s | Imaging of exogenous and enzymatically generated OCl– in PC12 cells | Long excitation wavelength, LOD = 2.41 nM | Turn-off | (25) |

| 21 | 580 and 626 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-off/10 min | Imaging of exogenous and endogenous OCl– in HepG2 cells | Long excitation wavelength, LOD = 72 nM | Turn-off, response time | (26) |

| 22 | 505 and 580 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-on/4 s | Imaging of exogenous HOCl in HepG2 cells and zebrafish, mito-tracking investigations | Mitochondria targeting, red emissive property, response time, LOD = 2.2 nM | (27) | |

| 23 | 370 and 501 | PBS/7.4 | FRET/20 min | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in HeLa cells | FRET-based probe | Response time | (28) |

| 24a, 24b, and 24c | 415 and 485 | HEPES/7.2 | Turn-on/30 min | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in NIH3T3 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast cells), visualization of accumulated OCl– level in zebrafish organs | LOD = 6.8 nM | HEPES buffer, response time | (29) |

| 25 | 468 and 520 | Citric acid-sodium citrate/4 | Turn-off/30 s | Imaging of exogenous OCl– in HeLa cells, tracking OCl– in lysosome of HeLa cells | Lysosome targeting, response time | Turn-off | (30) |

| 26 | 390 and 520 | PBS/7.4 | Turn-off/NA | Imaging of endogenous OCl– in HeLa cells, imaging of exogenous OCl– in zebrafish | LOD = 10 nM | Turn-off | (31) |

| 27 | 488 and 496/713 | PBS/7.4 | Ratiometric/NA | Imaging of exogenous and endogenously generated OCl– in HeLa cells | Ratiometric probe with NIR feature, LOD = 65 nM | (32) | |

| 28 | 500 and 567/629 | PBS/7.4 | Ratiometric/10 s | Imaging of exogenous and endogenously generated OCl– in L929 cells, mitotracking investigations | Ratiometric probe, response time, LOD = 31.6 nM | (33) |

In recent times, organelle-targeted fluorescent probes have gained immense interest due to their use in monitoring various intracellular subcompartmental bioactivities. Probes that can target specific organelles can provide valuable information on oxidative stress. However, the task is quite challenging due to the low concentration and short lifetime of HOCl/OCl– in the subcellular compartments. Knowledge of the distribution of HOCl at cellular levels remains elusive, even though probes with cell organelle targeting ability are available. In an acidic environment, the generation of OCl– occurs. Therefore, detection of OCl– requires a wide range of pH values. Probe 16 provided proof of application regarding the choice of a suitable buffer medium for the detection of HOCl/OCl–.21,22

Nevertheless, few probes described in this account have successfully been utilized for bioimaging purposes. However, further research is warranted in advancing HOCl/OCl– selective water-soluble probes. In this regard, mentioning the impact of the multiphoton imaging tool is worthwhile. Two-photon microscopy can be an attractive approach for monitoring HOCl/OCl– in live cells and tissues.36 In this line, probes 6 and 10 have been successfully utilized and paved the way for further research in this field. The use of fluorescence lifetime will also broaden the range of biological investigations. For in-depth biological studies, probes compatible with a super-resolution approach would also be beneficial. Recently, single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) techniques with precision localization have been widely applied in live cell imaging.37−39 Therefore, SMLM could become a dominant tool for visualizing the intracellular structural morphology with a lateral resolution range of 20–30 nm to study new biological roles of HOCl/OCl–. Due to aqueous solubility, high photon counts, favorable biocompatibility, and the eco-friendly nature, fluorescent carbon dots could be a suitable alternative to organic dyes.38,39 We expect researchers in this field to focus on developing new classes of molecules with improved photophysical properties such as super-resolution imaging, high photostability, NIR/NIR-II emission region, instant response ability, etc. So far, HOCl/OCl– specific probes have been developed for either monitoring or imaging intracellular HOCl/OCl–. Recently, HOCl/OCl– has been considered a biomarker of various cancers, osteoarthritis, neurodegeneration, and biological disorders. In other words, more efforts are also required to study the clinical functions of HOCl/OCl– in disease diagnosis and drug screening. Imaging-guided surgery, activated phototherapy, drug delivery systems, etc. require highly efficient probes to improve therapeutic and theranostic precision. The widespread use of these studies can be of great significance in the healthcare sector. We foresee significant research outcomes in this area in the days to come.

Acknowledgments