Abstract

The role of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I- and class II-restricted functions in Helicobacter pylori infection and immunity upon oral immunization was examined in vivo. Experimental challenge with H. pylori SS1 resulted in significantly greater (P ≤ 0.025) colonization of MHC class I and class II mutant mice than C57BL/6 wild-type mice. Oral immunization with H. pylori whole-cell lysates and cholera toxin adjuvant significantly reduced the magnitude of H. pylori infection in C57BL/6 wild-type (P = 0.0083) and MHC class I knockout mice (P = 0.0048), but it had no effect on the H. pylori infection level in MHC class II-deficient mice. Analysis of the anti-H. pylori antibody levels in serum showed a dominant serum immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) response in immunized C57BL/6 wild-type and MHC class I mutant mice but no detectable serum IgG response in MHC class II knockout mice. Populations of T-cell-receptor (TCR) αβ+ CD4+ CD54+ cells localized to gastric tissue of immunized C57BL/6 wild-type and MHC class I knockout mice, but TCRαβ+ CD8+ cells predominated in the gastric tissue of immunized MHC class II-deficient mice. These observations show that CD4+ T cells engaged after mucosal immunization may be important for the generation of a protective anti-H. pylori immune response and that CD4+ CD8− and CD4− CD8+ T cells regulate the extent of H. pylori infection in vivo.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium with gastric trophism that is implicated in the development of chronic gastritis, peptic ulceration, gastric adenocarcinoma, and lymphoma (4, 23, 25). Infection with Helicobacter spp. results in the development of markedly heterogeneous systemic immunoglobulin G (IgG) and mucosal IgA antibody responses (6, 26). Whereas populations of B cells can assemble into gastric lymphoid follicles and germinal centers driven by persistent antigenic stimulation (14, 30), the antibody and lymphofollicular reactions generated during Helicobacter infections are insufficient for clearance. On the other hand, populations of CD3+, CD4+ CD8−, and CD4− CD8+ T cells (2, 14) are recruited into gastric tissue during Helicobacter infections. A high frequency of H. pylori CD4+ T-cell clones derived from infected gastric biopsies respond to H. pylori antigenic stimulation in vitro in a Th1-like fashion (9, 10). At present, the relative contributions of gastric IgA-committed B cells and of Helicobacter-specific T cells in H. pylori immunity are not understood, although recent studies in murine models of Helicobacter felis infection have shown that Th2-type cells may reduce the infection level (21).

The experiments presented here examined the H. pylori infection density and the ability of oral immunization to interfere with H. pylori infection in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II mutant mice. We show the role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the regulation of H. pylori infection level and the requirement for CD4+ CD8− T cells for effective immunity against H. pylori infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

H. pylori infection and immunization schedules.

Groups (n = 10) of 6- to 8-week-old β2-microglobulin−/−, MHC class I-deficient mice (C57BL/6GphTacfBR-[KO]β2m N5), Abβ MHC class II knockout mice (C57BL/6TacfBR-[KO]Abβ N5), and C57BL/6 wild-type mice were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, N.Y.) and maintained in laminar flow microisolators for the duration of the experimental treatments. The mice were immunized per os (0.25 ml) with a blunt feeding needle (Popper & Sons, Inc., New Hyde Park, N.Y.) four times weekly with 500 μg of H. pylori whole-cell lysate antigens and 10 μg of cholera toxin (CT) adjuvant (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) in 0.2 M bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0), with buffer and 10 μg of CT adjuvant or with buffer alone, and challenged 2 weeks later with 106 CFU of H. pylori SS1 (19; kindly provided by A. Lee, University of New South Wales). Previous studies demonstrated that this H. pylori challenge doses resulted in 100% infection rates and represented >100 50% infective doses in C57BL/6 mice. The experiment was terminated 2 weeks after H. pylori challenge.

Growth of H. pylori and experimental challenge.

H. pylori SS1 was grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) containing 5% sheep blood (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) and 100 μg of vancomycin, 3.3 μg of polymyxin B, 200 μg of bacitracin, 10.7 μg of nalidixic acid, and 50 μg of amphotericin B (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. The plates were incubated for 72 to 80 h at 37°C in 10% CO2 and 5% O2 in a Trigas incubator (Queue Systems, Asheville, N.C.). The bacteria were then harvested, inoculated into brucella broth (BBL; Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Intergen, Purchase, N.Y.), and shaken at 120 rpm at 37°C in the Trigas incubator. Cultures were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 (ca. 5 × 108 CFU/ml) and diluted in brucella broth for inoculation. Prior to use, H. pylori cells were analyzed in wet mounts to assess motility and morphology and subjected to urease, catalase and oxidase tests.

Preparation of H. pylori antigens.

H. pylori was grown on selective blood agar plates at 37°C in 10% CO2 and suspended in 20 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.5). The cells were washed three times in PBS by centrifugation (12,000 × g) for 20 min at 4°C and disrupted by passage through a French press at a pressure of 15,000 lb/in2. After centrifugation (2,000 × g for 10 min) to remove cell fragments, the protein content was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay, and aliquots were frozen at −70°C until used.

Assessment of H. pylori infection.

Longitudinal segments of gastric tissue were homogenized in 0.5 ml of brucella broth, and replicate serial 10-fold dilutions were plated on Helicobacter-selective blood agar plates. The plates were incubated (37°C in a Trigas incubator), and quantitation of the CFU was performed 5 to 7 days later. For determination of infection with a urease assay, segments of antrum, including the corpus-antrum junction, were incubated in urea broth as described elsewhere (15). After 4 h, the extent of color change was recorded in an automated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader at OD550.

Determination of serum and gastric anti-H. pylori antibody levels.

Blood was obtained from the retroorbital sinus at the termination of the experiment. Gastric secretions were collected with absorbent wicks (15) positioned longitudinally in the gastric lumen after the stomach was rinsed extensively with PBS containing 0.2 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride (Calbiochem), 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, 10 μM leupeptin (Sigma), and 3.25 μM Bestatin (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) protease inhibitors (17). An ELISA was used for antibody measurements (24). In brief, triplicate wells of microtiter plates (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.) were incubated with purified H. pylori SS1 lysate antigens (100 μg/ml) in carbonate buffer. After being washed with PBS–0.5% Tween 20, the wells were blocked with PBS-Tween containing 2.5% nonfat dry milk and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with serial dilutions of sera or gastric secretions. The wells were then incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG1, anti-mouse IgG2a, or anti-mouse IgA (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.), followed by streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Calbiochem). Negative control sera and positive serum controls with known anti-H. pylori activity were included in each assay.

Immunohistochemical analyses of gastric resident leukocytes.

Longitudinal sections of gastric tissue, from the esophageal junction to the pyloric antrum, were mounted in OCT compound (Miles Scientific, Naperville, Ill.) and frozen in liquid nitrogen as described elsewhere (24). Tissue sections (7 μm) were fixed with acetone, and biotin-avidin binding sites were blocked for 30 min (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). The tissue sections were incubated with the biotinylated monoclonal antibodies (MAb) anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8α (53-6.7), anti-CD49d (9C10), anti-CD54 (3E2), anti-H-2Kb and -H-2Db MHC class I (28-8-6), or anti-I-Ab MHC class II (KH74) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), followed by avidin conjugated to biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (ABC; Vector Laboratories) as described elsewhere (24). Cell-bound peroxidase was visualized with 0.05% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.) and 0.01% H2O2 in PBS. For identification of IgA-containing cells (IgACC), the tissue sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgA (Southern Biotechnology), followed by avidin conjugated to biotinylated glucose oxidase (ABC-GO; Vector Laboratories). Cell-bound GO was visualized with TNBT tetrazolium salt (Vector Laboratories) in Tris-HCl buffer. The sections were counterstained with methyl green, and infiltrating leukocytes in the gastric antrum were quantitated in five random fields of duplicate tissue sections from each group of mice. The field was calibrated with a micrometer grid, and the mean number of cells was enumerated per field and adjusted to cells per square millimeter of tissue.

RESULTS

H. pylori infection in MHC class I and class II mutant mice.

The contribution of MHC class I or class II functions to experimental infection with H. pylori was examined. Challenge of MHC knockout mice and of C57BL/6 wild-type mice with H. pylori resulted in 90 to 100% infection rates (Table 1). Evaluation of the magnitude of colonization by quantitative bacterial culture showed a significantly increased H. pylori burden in MHC class I (P = 0.017) and MHC class II (P = 0.025) mutant mice compared to that in C57BL/6 wild-type mice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

H. pylori infection in C57BL/6 wild-type and MHC mutant micea

| Mouse strain | Infection levelb | No. of mice positive/total no.c | Quantitative H. pylori cultured |

|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 wild type | 1.51 ± 0.41 | 10/10 | 1.12 ± 0.37 |

| β2m−/− MHC class I deficient | 1.87 ± 0.52 | 10/10 | 2.41 ± 0.38e |

| Abβ MHC class II deficient | 2.14 ± 0.54 | 9/10 | 2.59 ± 0.55f |

Mice were challenged per os with 106 CFU of H. pylori SS1. After 2 weeks, gastric tissues were examined for infection level by a quantitative urease assay.

Mean OD550 ± standard error of the mean for each group of 10 mice.

A positive urease test indicative of H. pylori infection was defined as an OD550 >2 standard deviations above the group mean OD550 from unchallenged control mice.

Culture was performed on segments of gastric tissue at 2 weeks after H. pylori challenge as described in Materials and Methods. The values represent the mean CFU (105) ± the standard error of the mean for each group.

P = 0.017 by Wilcoxon rank sum analysis compared with C57BL/6 wild-type mice.

P = 0.025 by Wilcoxon rank sum analysis compared with C57BL/6 wild-type mice.

Protective immunity in MHC mutant mice with H. pylori antigens.

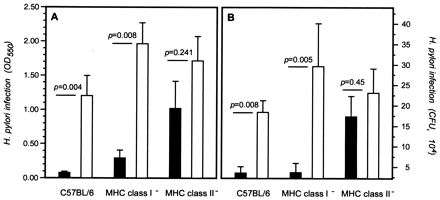

The ability of oral immunization to limit the severity of H. pylori infection was investigated. Whereas oral immunization with H. pylori lysate antigens resulted in a significant reduction of the H. pylori infection level in C57BL/6 wild-type (P = 0.0083) and in MHC class I-deficient (P = 0.0048) mice relative to those immunized with CT alone, immunization of MHC class II mutant mice with H. pylori lysate antigens had no effect on the magnitude of H. pylori infection (Fig. 1). Oral immunization of wild-type and MHC-deficient mice with CT did not affect the H. pylori density relative to treatment of the corresponding strain with buffer alone (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of oral immunization on H. pylori infection in MHC mutant mice. Groups of C57BL/6 wild-type, MHC class I mutant, or MHC class II mutant mice (n = 10 per group) were immunized with H. pylori whole-cell lysates and CT adjuvant (solid bars) or with CT alone (open bars) four times weekly, followed 2 weeks later by challenge with 106 CFU H. pylori SS1 organisms. Segments of gastric tissues were harvested 2 weeks after H. pylori challenge and were assayed for infection by a quantitative urease assay (A) or by quantitative culture (B). Bars show the mean CFU per biopsy for each group, and the brackets indicate 1 standard error of the mean.

Immune response in MHC knockout and C57BL/6 control mice.

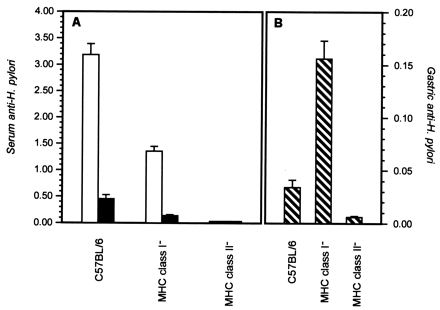

Oral immunization with H. pylori cell lysate antigens resulted in the development of a serum IgG anti-H. pylori antibody response of greater magnitude in C57BL/6 wild-type mice than in MHC class I mutant mice (Fig. 2). A higher level of serum IgG1 than IgG2a anti-H. pylori was consistently elicited as a function of oral immunization of wild-type and MHC class I mutant mice, but MHC class I knockout mice exhibited a depressed serum IgG1 and IgG2a response compared to C57BL/6 wild-type mice. In contrast, gastric H. pylori-specific IgA antibody levels were greatest in MHC class I mutant mice (Fig. 2). Serum IgG and gastric IgA anti-H. pylori antibody responses were not measurable in immunized MHC class II knockout mice. Challenge of buffer- or CT-treated MHC class I knockout and wild-type responder mice with 106 H. pylori organisms stimulated low anti-H. pylori antibody responses in serum (IgG1 levels < 0.30; IgG2a levels < 0.05 [OD405]) and gastric (<0.025) compartments.

FIG. 2.

Antibody responses in serum (A) and in gastric secretions (B) of wild-type and MHC knockout mice. Groups of immunized mice were challenged with live H. pylori. Two weeks later, the serum IgG1 (open bars), serum IgG2a (solid bars), and gastric IgA (striped bars) were quantitated by ELISA. The bars show the mean OD405 for each group, and the brackets indicate 1 standard error of the mean.

Phenotypic composition of gastric resident leukocytes in immunized MHC mutant mice.

The distribution of mononuclear leukocytes infiltrating gastric tissue in C57BL/6, MHC class I-deficient, and MHC class II knockout mice was investigated by immunohistochemistry. Populations of T-cell-receptor (TCR) αβ+ CD4+ cells were the dominant T cells resident in the antral mucosa of C57BL/6 wild-type and MHC class I knockout mice (Table 2). In contrast, a high frequency of TCRαβ+ CD4− CD8α+ cells were observed scattered in the antral mucosa and epithelia of MHC class II mutant mice (Table 2). While approximately 10 to 20% of the gastric leukocytes expressed the α4 integrin subunit, the majority of infiltrating leukocytes in wild-type and MHC mutant mice exhibited the CD54 activation marker (Table 2). Analyses of the IgA+ B-cell populations showed that immunized wild-type and MHC knockout mice accumulated equivalent frequencies of IgACC in the gastric antrum. Examination of gastric tissue from MHC knockout mice with anti-H-2Kb and -H-2Db MAb or with anti-I-Ab MAb confirmed the absence of MHC class I or class II expression in the epithelium and gastric resident leukocytes in the appropriate mutant mice.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypes of the infiltrating gastric leukocytes in immunized C57BL/6 wild-type and MHC mutant micea

| Mouse strain | Mean no.b of positively labeled cells/mm2 of gastric antrum ± SEM with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCRαβ | CD4 | CD8α | CD49d | CD54 | IgACC | |

| C57BL/6 wild type | 31 ± 3 | 25 ± 6 | 2 ± 0 | 7 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 37 ± 4 |

| β2m−/− MHC class I deficient | 25 ± 1 | 20 ± 3 | 1 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 16 ± 2 | 26 ± 8 |

| Abβ MHC class II deficient | 82 ± 15 | 1 ± 1 | 68 ± 11 | 17 ± 4 | 44 ± 4 | 57 ± 13 |

Mice were immunized with H. pylori lysate antigens and CT adjuvant and subsequently challenged with 106 CFU of H. pylori SS1. Gastric biopsies were excised 2 weeks later and were frozen for immunohistochemical staining with the MAb indicated.

Mean numbers of positively labeled cells/mm2 of gastric antrum from groups of five mice.

DISCUSSION

Infection with Helicobacter spp. results in the recruitment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in gastric tissue (2, 14). The accumulation of gastric Th1-type H. pylori-specific CD4+ cells has been proposed to account for their failure to generate protective immunity and to contribute to disease pathogenesis (2, 9). Although peripheral T cells derived from infected mice are unable to mediate clearance when adoptively transferred into H. felis-infected recipients (21), the present findings, showing that MHC deficiency exacerbates H. pylori infection, suggest an important regulatory role for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and/or their secreted cytokines during the early course of infection.

Oral immunization of MHC class I mutant mice with H. pylori antigens resulted in a significant reduction of the gastric H. pylori burden and in the generation of anti-H. pylori serum IgG and gastric IgA antibody. In contrast, MHC class II-deficient mice were unable to respond to oral antigenic stimulation and remained persistently infected with H. pylori. Because MHC class I-deficient mice are virtually devoid of peripheral CD4− CD8+ and intestinal CD8α+ intraepithelial lymphocytes (6, 31), while MHC class II mutant mice essentially lack mature CD4+ T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs (16), the present study strongly implicates CD4+ T cells in the protection against H. pylori infection upon mucosal immunization. The findings in immunized MHC class II knockout mice of a high frequency of gastric TCRαβ+ CD4− CD8+ CD54+ T cells further support the notion that antigen-specific CD4+ T cells activated after mucosal immunization may be involved in protective immunity against H. pylori in vivo. Although the events in T-cell activation, recirculation, and cytokine secretion are not understood, a low incidence of α4+ T cells was observed in gastric tissue of immunized wild-type and MHC knockout mice. The α4 integrin can be coexpressed either with the β1 subunit to form VLA-4, which mediates leukocyte transendothelial migration (28), or with the β7 integrin subunit to direct lymphocyte homing via the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM (3). The small numbers of α4+ TCRαβ+ cells suggested that T-cell populations recruited into gastric tissue after immunization may be largely derived from peripheral lymphoid organs, rather than recirculating from Peyer’s patches or the intestinal lamina propria.

Previous studies have suggested that mucosal IgA (8, 24) or IgG (13) antibody may mediate immunization-induced protection from Helicobacter infections, and this might explain the absence of effective immunity in MHC class II-deficient mice reported here. However, the relationship between antibody level and the extent of host protection against Helicobacter infections is discordant (20), and oral immunization may confer protection from H. felis infection in B-cell-deficient μMT mice (22). Furthermore, while MHC class I mutant mice show a less-efficient serum antibody response than do wild-type mice (28) and, as shown in this study, also exhibit depressed serum anti-H. pylori IgG responses after oral immunization, the extent of protective efficacy against H. pylori was comparable to that observed in wild-type mice. The finding that orally immunized MHC class II mutant mice generated a frequency of gastric IgACC equivalent to that of wild-type and MHC class I mutant mice is consistent with observations that CD4-deficient mice fail to respond to oral antigenic stimulation despite having a normal complement of mucosal IgA B cells (18). Thus, while orally immunized wild-type and MHC knockout mice harbored equivalent frequencies of IgACC, the magnitude of serum or gastric antibody responses was not predictive of the extent of protective immunity.

A common histopathologic feature in H. felis-immunized mice is the progressive infiltration into gastric tissue of CD4+ and, to a greater extent, CD8+ T-cell populations of unknown function (12). The observations reported here that gastric tissue of MHC class II knockout mice contained a high incidence of CD4− CD8+ CD54+ activated T cells within 2 weeks of H. pylori challenge may help to define the functional contribution of CD8+ cells to gastritis and epithelial-cell damage in the absence of CD4+ T cells. While gastric leukocyte infiltration appears to be a hallmark of protective anti-Helicobacter immunity in murine models, the H. pylori infection density in humans has been found to be associated with the degree of gastritis (1), and patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) show a lower incidence of gastritis and a lower prevalence of H. pylori infection relative to HIV-negative subjects (5, 11). Because T-cell recruitment into murine gastric tissue may be mediated by residual antigenic stimulation by live Helicobacter organisms in previously immunized hosts (12) and because CD4+ cells can regulate mucosal inflammatory reactions (27), the findings reported here raise the possibility that CD4+ T-cell populations generated during immunization in vivo may play an important role in limiting the severity of an H. pylori infection. Currently, it is not clear whether the lack of immune protection identified in MHC class II knockout mice is related to a deficit of CD4+ T cells in peripheral and gastric tissues or whether it is associated with elimination of class II MHC-restricted antigen presentation by gastric epithelia. However, both the current findings and the observation that T cells can reduce the H. felis burden when adoptively transferred into unimmunized recipients (21) strongly implicate CD4+ T cells in the protection against H. pylori infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maria Uria-Nickelsen for helpful discussions and Heather Kamp for technical assistance with bacterial quantitation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton J C, Tham K T, Peek R M, Clover T L, Blaser M J. Density of Helicobacter pylori infection in vivo as assessed by quantitative culture and histology. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:552–556. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamford K B, Fan X, Crowe S E, Leary J F, Gourley W K, Luthra G K, Brooks E G, Graham D Y, Reyes V E, Ernst P B. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:482–492. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin C, Berg E, Briskin M, Andrew D, Kilshaw P, Holtzmann B, Weissman I, Hamman A, Butcher E. α4β7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM. Cell. 1994;74:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori and the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:626–633. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacciarelli A G, Marano B J, Gualtieri N M, Zuretti A R, Torres R A, Starpoli A A, Robilotti J G. Lower Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease prevalence in patients with AIDS and suppressed CD4 counts. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1783–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa I, Bix M, Liao N S, Zijlstra M, Jaenish R, Raulet D. Most γδ T cells develop normally in β2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:653–657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crabtree J E, Shallcross T M, Wyatt J I, Taylor J D, Heatley R V, Rathbone B J, Losowsky M S. Mucosal humoral immune response to Helicobacter pylori in patients with duodenitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1266–1273. doi: 10.1007/BF01307520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czinn S J, Cai A, Nedrud J G. Protection of germ-free mice from infection by Helicobacter felis after active oral or passive IgA immunization. Vaccine. 1993;11:637–642. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90309-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Elios M M, Manghetti M, De Carli M, Costa F, Baldari C T, Burroni D, Telford J L, Romagnani S, Del Prete G. T helper 1 effector cells specific for Helicobacter pylori in the gastric antrum of patients with peptic ulcer disease. J Immunol. 1997;158:962–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Tommaso A, Xiang Z, Bugnolli M, Pileri P, Figura N, Bayeli P F, Rappuoli R, Abrignani S, De Magistris T. Helicobacter pylori-specific CD4+ T-cell clones from peripheral blood and gastric biopsies. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1102-1106.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eidt S, Schrappe M, Fischer R. Analysis of antral biopsy specimens for evidence of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in HIV1-seropositive and HIV1-negative patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:635–639. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ermak T H, Ding R, Ekstein B, Hill J, Myers G A, Lee C K, Pappo J, Kleanthous H K, Monath T P. Gastritis in urease-immunized mice after Helicobacter felis challenge may be due to residual bacteria. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1118–1128. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero R L, Thiberge J M, Labigne A. Local immunoglobulin G antibodies in the stomach may contribute to immunity against Helicobacter infection in mice. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox J G, Blanco M, Murphy J C, Taylor N S, Lee A, Kabok Z, Pappo J. Local and systemic immune responses in murine Helicobacter felis active chronic gastritis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2309–2315. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2309-2315.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox J G, Perkins S, Yan L, Shen Z, Attardo L, Pappo J. Local immune response in Helicobacter pylori-infected cats and identification of H. pylori in saliva, gastric fluid and faeces. Immunology. 1996;88:400–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grusby M J, Johnson R S, Papaioannou V E, Glimcher L H. Depletion of CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Science. 1991;253:1417–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.1910207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haneberg B, Kendall D, Amerongen H M, Apter F M, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Neutra M R. Induction of specific immunoglobulin A in the small intestine, colon-rectum, and vagina measured by a new method for collection of secretions from local mucosal surfaces. Infect Immun. 1994;62:15–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.15-23.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornquist C E, Ekman L, Dubravka Grdic K, Schon K, Lycke N Y. Paradoxical IgA immunity in CD4-deficient mice. Lack of cholera toxin-specific protective immunity despite normal gut mucosal IgA differentiation. J Immunol. 1995;155:2877–2887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee A, O’Rourke J, Corazon de Ungria M, Robertson B, Deskalopoulos G, Dixon M F. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C K, Weltzin R, Thomas W D, Kleanthous H, Ermak T H, Soman G, Hill J E, Ackerman S K, Monath T P. Oral immunization with recombinant Helicobacter pylori urease induces secretory IgA antibodies and protects mice from challenge with Helicobacter felis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:161–172. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammadi M, Nedrud J, Redline R, Lycke N, Czinn S J. Murine CD4 T-cell response to Helicobacter infection: Th1 cells enhance gastritis and Th2 cells reduce bacterial load. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nedrud J, Blanchard T, Redline R, Sigmund N, Czinn S. Orally immunized μMT antibody-deficient mice are protected against H. felis infection. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A1049. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nomura A, Stemmermann G N, Chyou P H, Kato I, Perez-Perez G I, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pappo J, Thomas W D, Kabok Z, Taylor N S, Murphy J C, Fox J G. Effect of oral immunization with recombinant urease on murine Helicobacter felis gastritis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1246–1252. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1246-1252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb A B, Warnke R A, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman J H, Friedman G D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Perez G I, Dworkin B M, Chodos J E, Blaser M J. Campylobacter pylori antibodies in humans. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:11–17. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powrie F, Leach M W, Mauze S, Menon S, Barcomb-Caddle L, Coffman R L. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–562. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spriggs M K, Koller B H, Sato T, Morrisey P J, Fanslow W C, Smithies O, Voice R F, Widmer M B, Laliszewski C R. β2-Microglobulin, CD8+ T-cell-deficient mice survive inoculation with high doses of vaccinia virus and exhibit altered IgG responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6070–6074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vonderheide R, Tedder T, Springer T, Staunton D. Residues within a conserved amino acid motif of domains 1 and 4 of VCAM-1 are required for binding to VLA-4. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:215–222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wotherspoon A C, Doglioni C, Diss T C, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson P G. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zijlstra M, Bix M, Simister N E, Loring J M, Raulet D H, Jaenisch R. β2-Microglobulin deficient mice lack CD4− CD8+ cytolytic T cells. Nature. 1990;344:742–746. doi: 10.1038/344742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]