Abstract

Merozoite surface protein 1 is a candidate for blood-stage vaccines against malaria parasites. We report here an immunization study of Saimiri monkeys with a yeast-expressed recombinant protein containing the C terminus of Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 1 and two T-helper epitopes of tetanus toxin (yP2P30Pv20019), formulated in aluminum hydroxide (alum) and block copolymer P1005. Monkeys immunized three times with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 had significantly higher prechallenge titers of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against the immunogen and asexual blood-stage parasites than those immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in alum, antigen alone, or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (P < 0.05). Their peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferative responses to immunogen stimulation 4 weeks after the second immunization were also significantly higher than those from the PBS control group (P < 0.05). Upon challenge with 100,000 asexual blood-stage parasites 5 weeks after the last immunization, monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 had prepatent periods longer than those for the control alone group (P > 0.05). Three of the five animals in this group also had low parasitemia (peak parasitemia, ≤20 parasites/μl of blood). Partially protected monkeys had significantly higher levels of prechallenge antibodies against the immunogen than those unprotected (P < 0.05). There was also a positive correlation between the prepatent period and titers of IgG antibodies against the immunogen and asexual blood-stage parasites and a negative correlation between accumulated parasitemia and titers of IgG antibodies against the immunogen (P < 0.05). These results indicate that when combined with block copolymer and potent T-helper epitopes, the yeast-expressed P2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein may offer some protection against malaria.

Plasmodium vivax is one of the most widely distributed human malaria parasites, prevalent in South America, Asia, and Oceania (27). With the appearance of resistance to current antimalarial drugs (9), an effective vaccine against the parasite is urgently needed. Several antigens expressed at different stages of the parasite life cycle have been characterized and found to have the potential for use in a subunit vaccine against P. vivax (2, 15, 32, 37). One of these antigens. merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP-1), is considered a leading candidate for vaccines targeted at asexual blood stages of the life cycle (27).

Plasmodium MSP-1 is a glycoprotein synthesized during schizogony and proteolytically processed into a complex of polypeptides (18). Only the C-terminal 19-kDa fragment derived from a second processing step remains on the merozoite surface during the invasion of a new erythrocyte. Two epidermal growth factor-like domains have been identified in the cysteine-rich region of the fragment (3, 4). Comparison of the MSP-1 amino acid sequences of two monkey-adapted P. vivax strains with those of P. falciparum MAD 20 and P. yoelii YM has revealed that the C-terminal 19-kDa fragment, especially the cysteine residues responsible for the formation of the two epidermal growth factor-like domains (4, 13, 16), is well conserved among these plasmodial species. This finding indicates that the C-terminal 19-kDa fragment of MSP-1 may be involved in important biological functions during invasion.

In vitro and in vivo studies with P. falciparum (3, 7, 8, 10, 20, 26, 33) and P. yoelii (6, 11, 28, 30, 34, 42) have shown that immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies or monoclonal antibodies directed against the C-terminal 19-kDa fragment can inhibit the invasion of parasites into erythrocytes or protect mice or monkeys against live parasite challenges. Field studies have also shown that production of IgG antibodies against the 19-kDa fragment of P. falciparum correlates with the development of clinical immunity against falciparum malaria (17, 35, 36). Taken together, these findings suggest that the C-terminal 19-kDa fragment of MSP-1 is a vaccine candidate antigen against asexual blood-stages of malaria parasites.

Both humoral and cellular immune responses are necessary for an effective malaria vaccine against blood-stage parasites (29, 40). One way to influence the host immune responses to an antigen is by the use of adjuvants (1, 19, 23, 25, 45). Immunization studies with C-terminal fragments of P. falciparum MSP-1 in primate malaria models showed that no protection was induced when an Escherichia coli-expressed 19-kDa antigen was formulated in aluminum hydroxide (alum) and liposomes (5). However, protection was achieved when a baculovirus-expressed 42-kDa or yeast-expressed 19-kDa antigen mixed with the Freund’s complete adjuvant (7, 26). A recent report has also shown that rhesus monkeys immunized with baculovirus-expressed 42- or 19-kDa antigen of P. cynomolgi MSP-1 in Freund’s complete or incomplete adjuvants were protected (32). Thus, adjuvants affect the efficacy of recombinant MSP-1 vaccines. Unfortunately, Freund’s adjuvant is too toxic for human use, and alum is currently the only approved human-usable adjuvant.

One adjuvant currently under development for use in humans is the nonionic block copolymer, which is a simple linear chain of the hydrophobic polyoxypropylene flanked by two chains of the hydrophilic polyoxyethylene (22). Antigens bind to the hydrophobic surface of copolymers by hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions. Our studies with different formulations of nonionic block copolymers P1004 and P1005 with malaria antigens have shown that they can modulate both humoral and cellular immune responses, resulting in different outcomes of challenge infections (21, 41, 46, 47).

In contrast to the intensive studies done on P. falciparum and P. yoelii MSP-1, little is known about P. vivax MSP-1. Our previous study of mice with a yeast-expressed 19-kDa antigen of P. vivax MSP-1 formulated in nonionic block copolymer P1005 showed that this formulation was highly immunogenic. Mice produced high antibody and proliferative responses comparable to those induced by using Freund’s complete adjuvant (46). In this study, we further evaluated the immunogenicity of this yeast-expressed P. vivax MSP-1 19-kDa fragment in Saimiri monkeys and assessed the protective effect of immunizations with this recombinant protein in the human-usable adjuvant alum and a potentially usable adjuvant block copolymer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antigen.

The antigen was a yeast-expressed recombinant protein, yP2P30Pv20019, consisting of the C terminus (amino acids Asn1622 to Ser1729) of the MSP-1 of P. vivax Sal I (16). In addition, two universal T-helper epitopes (P2 and P30) of tetanus toxin (31, 44) and six histidine residues for purification purposes were attached to the N and C termini, respectively. The expression, purification, and characterization of this antigen are described in detail elsewhere (24). The purity of the recombinant protein was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. No aggregates were present in the recombinant antigen preparation used in this study.

Adjuvants.

The two adjuvants used were the nonionic block copolymer P1005 (provided by Vaxcel Corp., Norcross, Ga.) and alum (Rehsorptar; Intergen, Purchase, N.Y.). For the nonionic block copolymer P1005, a water-in-oil emulsion was prepared by mixing a 20% oil phase (10% Span 80 in squalene) and a 80% aqueous phase (200 μg of yP2P30Pv20019 and 5 mg of P1005 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] per immunization ) (39). For the adsorption of yP2P30Pv20019 onto alum, a procedure developed by de Oliveira et al. (14) was used. Briefly, acid washed Rehsorptar was mixed with yP2P30Pv20019 in a ratio of 1 μg of antigen to 2 μg of alum. The antigen-alum mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with rotation. The adsorbed alum-antigen complex was then centrifuged and resuspended in PBS. The adsorption efficiency was monitored by measuring the remaining protein in the supernatant after centrifugation.

Animals and immunization.

Twenty Saimiri boliviensis boliviensis monkeys of Bolivian origin (8 males and 12 females, average body weight of about 700 g) were used. Before the study began, the animals were quarantined and acclimated for 6 weeks. During this period, they were weighed, physically examined by a staff veterinarian, and tested for tuberculosis and other infections. All animals were determined to be healthy at the beginning of this study. None of the animals had antibodies against P. vivax and P. brasilianum (the only known malaria parasite naturally infective to Saimiri monkeys) blood-stage parasites by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). Protocols were reviewed and approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

The study was conducted in a double-blind format. Monkeys were randomly assigned into four groups of five animals each, with the same sex ratio and average body weight. Animals in group I were immunized with the yP2P30Pv20019 antigen formulated in block copolymer P1005 in a water-in-oil emulsion. Animals in group II were given yP2P30Pv20019 adsorbed onto alum. Animals in group III received only yP2P30Pv20019 in PBS. Animals in group IV were used as controls and received PBS. Immunization consisted of three subcutaneous injections at 4-week intervals starting at week −13. Monkeys in the first three groups received 200 μg of yP2P30Pv20019 for each immunization. For each immunization, 50- or 100-μl doses of the immunization formulations were injected into four sites on the back of each animal. The code for antigen administration was revealed only after the completion of parasitemia determination and cellular and humoral immune response analyses.

Asexual blood-stage parasite challenge.

Five weeks after the third immunization (week 0), each of the animals were intravenously challenged with 100,000 P. vivax Sal I asexual blood-stage parasites from a infected donor Saimiri monkey. Seven or eight days following the blood-stage parasite challenge, monkeys were splenectomized to allow higher parasitemia. Animals were monitored daily for the development of parasitemia, starting at day 6 after the blood-stage parasite challenge and ending at day 42.

Antibody assays. (i) ELISA.

To monitor humoral immune responses to immunizations, titers of antibodies against immunogen yP2P30Pv20019 were determined by a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedure (47). Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Immulon 2; Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., McLean, Va.) were coated with yP2P30Pv20019 (100 μl/well; 0.2 μg/ml in borate-buffered saline [167 mM boric acid, 134 mM NaCl {pH 8.0}]) at 4°C overnight. The plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), blocked with 5% fat-free dry milk in borate-buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature, and washed again with PBS-T to remove unbound recombinant proteins. Serial dilutions of serum samples were added to the wells in triplicate, starting with a 1:100 dilution and followed by twofold dilutions. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, plates were washed three times with PBS-T plus 0.5M NaCl and once with PBS-T and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-Saimiri IgG for another hour. The bound antibodies were detected by incubation of wells with 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine-peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μl of 1 M H3PO4 and read at 450 nm with a microplate reader. Titers were based on the highest dilution of the sample that generated an optical density greater than the mean of preimmunization sera plus 2 standard deviations (cutoff optical density = 0.805).

(ii) IFA.

Antibodies against asexual blood-stage parasites 1 week after the third immunization, on the day of the asexual blood-stage parasite challenge (week 0), and 2 and 4 weeks after the asexual blood-stage parasite challenge were determined by IFA as described by Sulzer et al. (38). In short, 10 μl aliquots of twofold serial dilutions of sera were added onto multispot antigen slides containing P. vivax Sal I blood-stage parasite-infected blood from a Saimiri monkey. The slides were incubated in a most chamber at 37°C for 30 min. After washing with PBS, fluorescence isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-Saimiri IgG antibodies were added. After incubation and washing, antibody titers were determined under a fluorescence microscope.

(iii) Lymphocyte proliferation assays.

To determine the cellular immune responses to the immunogen yP2P30Pv20019, proliferation assays were performed with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from immunized animals at preimmunization, 4 weeks after the first and second immunization, and 4 weeks after the asexual blood-stage parasite challenge. Proliferation assays were also conducted with splenocytes 1 week after the blood-stage parasite challenge. For lymphoproliferation assays, blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes and PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) centrifugation. For splenocytes proliferation assay, splenocytes were released from the spleen by crushing. After washing with RPMI 1640, 2 × 105 PBMCs or splenocytes in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% human AB+ serum and 5% fetal bovine serum were added to 96-well U-bottom culture plates in triplicate. The yP2P30Pv20019 antigen in 100 μl of culture medium (20 μg/ml) was also added to the wells, using phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) at 10 μg/ml as a control. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 6 days. Eighteen hours before the termination of incubation, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well. Cells were harvested onto glass fibers, and the incorporated radioactivity was measured in a scintillation counter. The results were expressed as stimulation index (SI) calculated by the following formula: SI = mean counts per minute of antigen wells/mean counts per minute of control wells.

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as geometric means. Differences among groups were compared by Fisher’s protected least significant difference test. The association between prechallenge IgG antibody titers and the prepatent period or parasitemia was determined by Pearson correlation analysis. Parasitemia data were analyzed after logarithmic transformation. Significance was declared at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Prepatent period and parasitemia.

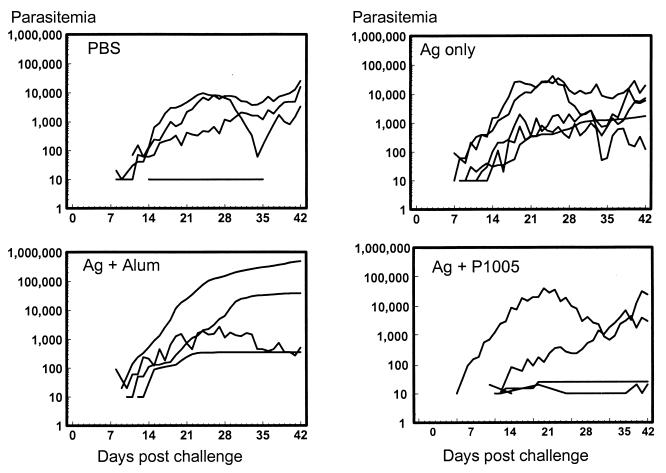

Monkey were immunized three times at 4-week intervals with yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein in two different adjuvants: nonionic block copolymer P1005 and alum. No adverse reactions to the immunizations were detected in monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 or yP2P30Pv20019 in alum during the experimental period. Animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in P1005, however, developed skin sores at the injection sites after the second immunization. One monkey each from the alum and PBS control groups died from causes unrelated to the study after the second and third immunizations, respectively. All remaining animals were challenged intravenously with 100,000 P. vivax Sal I asexual blood-stage parasites. Parasitemia developed in all four animals in the PBS control group (Fig. 1). Of the four animals, three had high parasitemia (accumulated parasite counts of 54,587, 68,536, and 185,916 parasites/μl), and one had a low parasite count (100 parasites/μl) (Table 1). Three of the five animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 developed low parasitemia (25, 30, and 120 Parasites/μl) and thus were considered to be partially protected; the other two monkeys developed a high parasite counts (93,399 and 291,391 parasites μl). Among the animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in alum or antigen alone, one animal from each group had a low parasite count (<2,000 parasites/μl), and the remaining animals all developed moderate to high parasitemia (11,703 to 485,947 parasites/μl). In addition, monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 had slightly longer prepatent periods than control monkeys (geometric mean, 12.3 days versus 9.9 days; P >0.05) Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Parasitemia (parasites per microliter) of control monkeys (PBS) and monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 (Ag [antigen] only), yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer (Ag + P1005), or yP2P30Pv20019 in alum (Ag + Alum) three times at 4-week intervals (weeks −13, −9, and −5) and challenged at week 0.

TABLE 1.

Prepatent periods, peak parasitemia, accumulate parasitemia, PBMC proliferative responses, and titers of IgG antibodies against the immunogen and blood-stage parasites in Saimiri monkeys after immunization with three doses of yP2P30Pv20019 and challenged 5 weeks after the last immunization with 100,000 P. vivax asexual blood-stage parasites

| Immunogen | Monkey | Prepatent period (day) | Parasitemia (parasites/μl of blood) peak

|

SIb | Antibody titer at challenge

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Accumulated | ELISA | IFA | ||||

| yP2P30Pv20019 + P1005 | SI-1024 | 15 | 10 | 25 | 11.47 | 218,700 | 12,800 |

| SI-2126 | 13 | 20 | 30 | 6.11 | 218,700 | 25,600 | |

| SI-2053 | 14 | 20 | 120 | 4.01 | 409,600 | 25,600 | |

| SI-2119 | 15 | 24,170 | 93,399 | 5.91 | 218,600 | 25,600 | |

| SI-2063 | 7 | 40,140 | 291,391 | 4.08 | 72,900 | 12,800 | |

| Geometric mean | 12.3 | 329 | 1,196 | 5.84 | 199,016 | 19,401 | |

| yP2P30Pv20019 + alum | SI-1021 | 12 | 60 | 321 | 0.88 | 218,700 | 12,800 |

| SI-2083 | 8 | 2,727 | 27,925 | 2.83 | 145,800 | 3,200 | |

| SI-2016 | 10 | 7,909 | 37,789 | 2.77 | 72,900 | 3,200 | |

| SI-2021 | 9 | 41,580 | 485,947 | 2.38 | 24,300 | 1,600 | |

| Geometric mean | 10.1 | 2,798 | 20,142 | 2.49 | 102,368 | 5,271 | |

| yP2P30Pv20019 + PBS | SI-1069 | 8 | 242 | 1,694 | 1.03 | 100 | 0 |

| SI-2143 | 8 | 990 | 11,703 | ND | 16,200 | 1,600 | |

| SI-2109 | 11 | 14,400 | 65,576 | 0.56 | 900 | 100 | |

| SI-2059 | 7 | 41,580 | 460,524 | 0.97 | 600 | 50 | |

| SI-2128 | 7 | 35,087 | 232,798 | 1.33 | 0 | 0 | |

| Geometric mean | 8.1 | 5,468 | 42,542 | 0.93 | 244 | 24 | |

| PBS | SI-2105 | 14 | 10 | 100 | 1.07 | 0 | 0 |

| SI-2026 | 8 | 8,272 | 68,536 | 2.10 | 0 | 0 | |

| SI-2077 | 8 | 16,020 | 54,587 | 1.10 | 0 | 0 | |

| SI-793 | 11 | 25,200 | 185,916 | 1.42 | 0 | 0 | |

| Geometric mean | 9.9 | 2,404 | 16,240 | 1.37 | 0 | 0 | |

Sum of parasitemia for 42 days.

Determined 4 weeks after the second immunization. ND, not done.

IgG antibodies against the yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein.

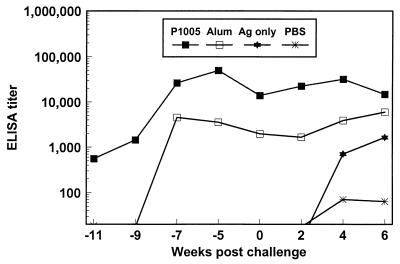

Levels of total IgG antibodies against the immunogen yP2P30Pv20019 were measured by ELISA at 2-week intervals, starting 2 weeks after the first immunization (−11 weeks) until the end of the study (6 weeks). Monkeys from the PBS control group had no detectable antibodies after the third immunization (Fig. 2). Animals immunized with the yP2P30Pv20019 alone also had no detectable antibodies after the first immunization. Although antibody titers in monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 or in alum were low after the first immunization, monkeys immunized with block copolymer P1005 as adjuvant had antibody titers significantly higher than those from all of the three other groups (P < 0.05). Antibody titers increased in animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 or in alum after the second immunization and reached the maximal levels after the third immunization (P < 0.05 between the P1005 or alum group and the antigen-alone or PBS group).

FIG. 2.

Levels of IgG antibodies against the yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein in sera from control monkeys (PBS) and monkeys immunizaed with yP2P30Pv20019 (Ag [antigen] only), yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer (P1005), or yP2P30Pv20019 in alum (Alum) three times at 4-week intervals (weeks −13, −9, and −5) and challenged at week 0. Group geometric means are shown.

Challenge of monkeys with 100,000 asexual blood stage-parasites failed to further boost the titers of antibodies against the immunogen in monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 or in alum, although antibody levels 4 weeks after the challenge were higher than at challenge (week 0). Titers of antibodies against the immunogen from animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 alone or PBS were moderately increased after the challenge and reached higher levels 6 weeks after the challenge. However, antibody levels from animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 or alum were still significantly higher than in those immunized with antigen alone or PBS at challenge and at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after the challenge (P < 0.05).

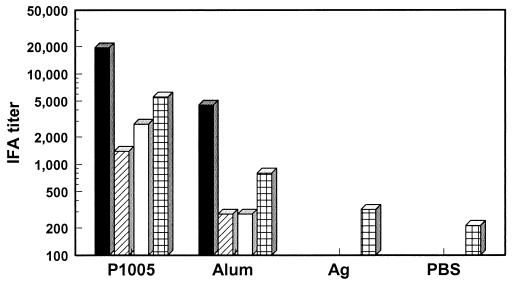

IgG antibodies against asexual blood-state parasites.

Titers of IgG antibodies against air-dried P. vivax asexual blood-stage parasites were determined by IFA 1 week after the third immunization, at challenge, and 2 and 4 weeks after the challenge (Fig. 3). One week after the third immunization or at challenge (5 weeks after the third immunization), animals immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 or in alum had higher antibody levels than those immunized with antigen alone or PBS. The difference between the block copolymer P1005 group and the three other groups was significant (P < 0.05). Challenge with 100,000 P. vivax asexual blood-stage parasites boosted antibody titers in all groups, with the block copolymer P1005 group having the highest titers. The difference between the block copolymer P1005 or alum group and the antigen-alone or PBS group was significant (P < 0.05). This boosting in IFA titers after parasite challenge might be due to specific antibodies or antibodies of other parasite specificities.

FIG. 3.

Levels of IgG antibodies against asexual blood-stage parasite antigens in sera from control monkeys (PBS) and monkeys immunized yP2P30Pv20019 (Ag[antigen]), yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer (P1005), or yP2P30PV20019 in alum (Alum). Monkey sera were tested by IFA for total IgG antibodies against air-dried P. vivax blood-stage-infected Saimiri monkey erythrocytes 1 week after the third immunization (■), on the day of challenge (▨), and 2 (□) and 4 ( ) weeks after challenge. Group geometric means are shown.

) weeks after challenge. Group geometric means are shown.

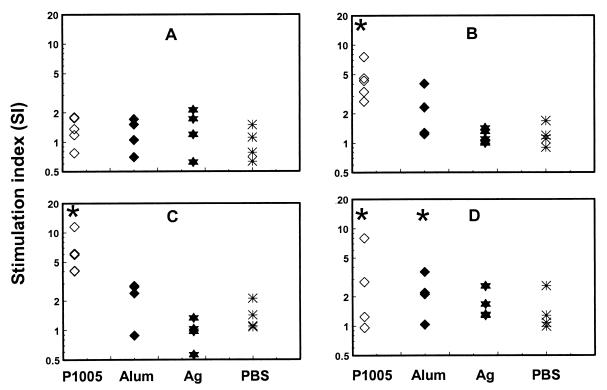

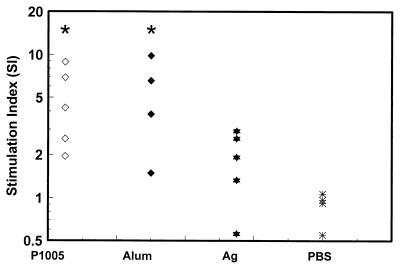

PBMC proliferative responses to the yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein.

To evaluate T-cell responses in the yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein, PBMC proliferation assays were performed with monkey PBMCs collected at preimmunization, 4 weeks after the first and second immunization, and 4 weeks after the asexual blood-stage parasite challenge. As a control, PBMCs were simultaneously stimulated with the mitogen PHA. PBMCs from all monkeys responded to PHA stimulation at SI values ranging from 5 to 45, with unstimulated PBMCs having around 2,500 cpm (data not shown). All monkeys (except one from the antigen-alone group) had not proliferative responses to yP2P30Pv20019 (SI values ranges from 0.62 to 1.80; P > 0.05 among all groups) at preimmunization (Fig. 4A). Four weeks after the first immunization, PBMC proliferative responses yP2P30Pv20019 started to increase in monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer P1005 or alum compared with those in the antigen-alone or PBS group. The difference in SI values between the block copolymer P1005 group and alum, antigen alone, or PBS control group significantly (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). The SI values of monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in P1005 or alum continued to increase 4 weeks after the second immunization, with the block copolymer P1005 group having the highest proliferative responses (SI ranging from 4.0 to 11.47) (Fig. 4C and Table 1). The difference between the block copolymer P1005 group and the other three groups was significant (P < 0.05). Challenge of monkeys with 100,000 asexual blood-stage parasites failed to boost PBMC proliferative responses to the immunogen (Fig. 4D). Although the P1005 and alum groups had significantly higher SI values than the control group, the proliferative response in the P1005 group was actually lower than before the challenge.

FIG. 4.

Proliferative responses (SI) of PMBCs) from control monkeys (PBS) and monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 (Ag [antigen]), yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer (P1005), or yP2P30Pv20019 in alum (Alum) after stimulation with 2 μg of yP2P30Pv20019/well. (A) preimmunization; (B and C) 4 weeks after the first and second immunizations; (D) 4 weeks after asexual blood-stage parasite challenge. Individual SI values are shown. Asterisks indicate that the group mean is significantly different from that of the immunized control monkeys (P < 0.05).

Splenocyte proliferative responses to the yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein.

Splenocyte proliferative responses to the immunogen were also conducted 1 week after the asexual blood-stage parasite challenge. Splenocytes from PBS control monkeys had no responses to the stimulation of yP2P30Pv20019 recombinant protein (mean SI of 0.55 to 1.07, with counts per minute ranging from 769 to 1,439) (Fig. 5). In contrast, splenocytes from monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 in P1005 or alum responded to the immunogen stimulation with average SI values of 4.19 and 4.38, respectively. The difference between the block copolymer or alum groups and the PBS control group was significant (P < 0.05).

FIG. 5.

Proliferative responses (SI) to yP2P30Pv20019 of splenocytes from control monkeys (PBS) and monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019 (Ag [antigen]), yP2P30Pv20019 in block copolymer (P1005), or yP2P30Pv20019 in alum (Alum) 1 week after blood-stage parasite challenge. Individual SI values are shown. Asterisks indicate that the group mean is significantly different from that of the unimmunized control monkeys (P < 0.05).

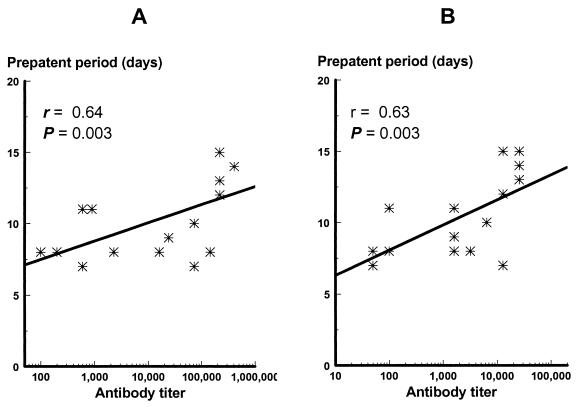

Association of partial protection with IgG antibody production.

To assess the role of IgG antibodies in protection, the association between partial protection and IgG antibody levels measured by ELISA and IFA was analyzed. Monkeys (SI-1024, -2126, -2053, -1021, -1069, and -2142) partially protected (with peak parasitemia lower than 1,000/μl) from the asexual blood-stage parasite challenge had significantly higher prechallenge IgG antibody levels than those unprotected when IgG antibody titers were determined by ELISA (geometric mean of 147,327.7 versus 2,775.1; P < 0.05). Likewise, there was also a significant positive correlation between the prepatent period and prechallenge IgG antibody levels by both ELISA and IFA (r = 0.64 and 0.63, respectively; P < 0.05) (Fig. 6) and a significant negative correlation between accumulated parasitemia and prechallenge IgG antibody titers (r = −0.59 for ELISA and −0.48 for IFA; P < 0.05).

FIG. 6.

Correlation between titers of prechallenge IgG antibodies against the immunogen (A) and blood-stage parasite (B) and the prepatent period in monkeys immunized with yP2P30Pv20019.

DISCUSSION

We have assessed the immunogenicity of a yeast-expressed recombinant protein containing the C-terminal 19-kDa fragment of P. vivax MSP-1 and two T-helper epitopes of tetanus toxin and have evaluated this recombinant protein formulated in human usable and potentially human-usable adjuvants, alum and block copolymer P1005, for the ability to induce protective immune response in a nonhuman primate malaria model system. Our results showed that Saimiri monkeys immunized three times with the C-terminal 19-kDa recombinant protein formulated in block copolymer P1005 produced titers of IgG antibody response against both the immunogen and asexual blood-stage parasite antigens higher than those immunized with the C-terminal 19-kDa antigen in alum or antigen alone. These monkeys also had significantly higher PBMC proliferative response than PBS control animals when stimulated with the immunogen 4 weeks after the second immunization. Upon challenge with 100,000 asexual blood-stage parasites, monkeys immunized with the C-terminal 19-kDa recombinant antigen in block copolymer P1005 had somewhat longer prepatent periods than control monkeys. Three of the five monkeys in this group developed very low blood-stage parasite infections and thus were partially protected.

Both humoral and cellular immune responses were induced by vaccination with the recombinant 19-kDa protein. Monkeys immunized with the recombinant antigen in P1005 or alum had high titers against the immunogen as well as proliferative responses. Antibody production and proliferative responses were the highest in animals immunized with the 19-kDa antigen in P1005, probably as a result of the potent stimulatory effect of P1005 to both humoral and cellular immunity (43). The protective immunity induced by vaccination, nevertheless, appears to be mediated in part by antibodies. Monkeys with higher IgG antibody titers at the challenge had longer prepatent periods and lower peak and accumulated parasite counts than those with lower IgG antibody titers. Studies with rodent malaria P. yoelii also showed that protection against blood-stage infection after immunization of mice with the C-terminal domain of P. yoelii MSP-1 was partially mediated by antibodies since passive transfer of immune sera or purified IgG protected some naive mice against lethal disease (28). Factors other than antibodies probably also played a role in protection against malaria, because one partially protected monkey (SI-1069) had not titers of antimalaria antibodies.

Adjuvants appear to play a role in protective immunity induced by MSP-1. Previous studies with the C-terminal 42- or 19-kDa fragment of P. falciparum and P. cynomolgi MSP-1 showed that monkeys immunized with the C-terminal fragment were partially protected against blood-stage parasite challenge when the immunogen was formulated in Freund’s complete adjuvant (7, 26, 32). However, when liposome and alum were used as adjuvants, monkeys were not protected against blood-stage parasite challenge (5). In agreement with previous studies (5, 12), results of this study with the 19-kDa fragment of P. vivax showed that alum, the only approved human-usable adjuvant, failed to induce a protective immune response against blood-stage parasite challenge following immunizations, although it induced moderate levels of IgG antibodies. In contrast, when the potentially human-usable adjuvant block copolymer P1005 was used as adjuvant, the recombinant 19-kDa MSP-1 antigen induced a protective immune response in a nonhuman primate malaria model. Our previous studies showed that mice immunized with the C terminus of P. vivax MSP-1 formulated in block copolymer P1005 generated high humoral and cellular immune responses comparable to those for mice immunized with the C terminus in Freund’s complete adjuvant (46). Furthermore, monkeys immunized with a P. vivax circumsporozoite protein-based multiple-antigen construct formulated in P1005 were protected against sporozoite challenges (47). Taken together, these findings indicate that the block copolymer P1005 is an effective adjuvant. Its usage in human malarial vaccine, however, has to be tested further in laboratory animals because of the development of skin sores at the injection sites seen in this study. Perhaps an aqueous phase rather than the water-in-oil emulsion of the adjuvant should be used, because P1005 in aqueous solution has been shown recently to be safe in humans (43).

The partial protection induced by immunization with 19-kDa MSP-1 antigen of P. vivax in Saimiri monkeys observed in this study is lower than that recently achieved by immunization against P. cynomolgi in toque monkeys with 42- or 19-kDa MSP-1 antigen (32). In the latter, close to complete protection was obtained by immunization with baculovirus-expressed P. cynomolgi MSP-1 antigens in Freund’s adjuvant. This difference is likely the result of differences in model systems and/or adjuvants. Development of immunity against P. cynomolgi in toque monkeys is rapid; thus, animals recovered from primary infection appear refractory to subsequent infections. In contrast, development of immunity against P. vivax in Saimiri monkeys is a gradual process; animals that recover from primary infection are not protected against subsequent infections.

Further investigations, however, are needed to validate the efficacy of this vaccine. These studies should include adjuvant controls as well as large number of animals per group to minimizing the effect of variations in parasitemia and the prepatent period. Subsequent studies should also investigate the protective efficacy of this vaccine in intact rather splenectomized animals. Notwithstanding these issues, results of this preliminary study suggest that the C terminus of MSP-1 is highly immunogenic and may offer some protection against P. vivax blood-stage parasites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ae M. Saekhou, Carla L. Morris, Robb C. Reed, and personnel at the Scientific Resources Program, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC, for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by USAID IAA 963-9001-G-00-6-540-00.

REFERENCES

- 1.al-Yaman F, Genton B, Kramer K J, Chang S P, Hui G S, Baisor M, Alpers M P. Assessment of the role of naturally acquired antibody levels to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in protecting Papua New Guinea children from malaria morbidity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:443–448. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnot D E, Barnwell J W, Tam J P, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig R S, Enea V. Circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium vivax: gene cloning and characterization of the immunodominant epitope. Science. 1985;230:815–818. doi: 10.1126/science.2414847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackman M J, Heidrich H G, Donachie S, McBride J S, Holder A A. A single fragment of a malaria merozoite surface protein remains on the parasite during red cell invasion and is the target of invasion-inhibiting antibodies. J Exp Med. 1990;172:379–382. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackman M J, Ling I T, Nicholls S C, Holder A A. Proteolytic processing of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 produces a membrane-bound fragment containing two epidermal growth factor-like domains. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90127-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burghaus P A, Wellde B T, Hall T, Richards R L, Egan A F, Riley E M, Ballou W P, Holder A A. Immunization of Aotus nancymai with recombinant C terminus of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 in liposomes and alum adjuvant does not induce protection against a challenge infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3614–3619. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3614-3619.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns J M, Jr, Parke L A, Daly T M, Cavacini L A, Weidanz W P, Long C A. A protective monoclonal antibody recognizes a variant-specific epitope in the precursor of the major merozoite surface antigen of the rodent malarial parasite Plasmodium yoelii. J Immunol. 1989;142:2835–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang S P, Case S E, Gosnell W L, Hashimoto A, Kramer K, Tam L Q, Hashiro C Q, Nikaido C M, Hui G S N. A recombinant baculovirus 42-kilodalton C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 protects Aotus monkeys against malaria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:253–261. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.253-261.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappel J A, Holder A A. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum invasion in vitro recognize the first growth factor-like domain of merozoite surface protein-1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;60:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90141-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins W E, Jeffery G M. Primaquine resistance in Plasmodium vivax. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:243–249. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper J A, Cooper L T, Saul A J. Mapping of the region predominantly recognized by antibodies to the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen MSA 1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;51:310–312. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly T M, Lang C A. A recombinant 15-kilodalton carboxyl-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii yoelii 17XL merozoite surface protein 1 induces a protective immune response in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2462–2467. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2462-2467.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly T M, Long C A. Influence of adjuvants on protection induced by a recombinant fusion protein against malarial infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2602–2608. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2602-2608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.del Portillo H A, Longacre S, Khouri E, David P H. Primary structure of the merozoite surface antigen 1 of Plasmodium vivax reveals sequences conserved between different Plasmodium species Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4030–4034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Oliveira G A, Clavijo P, Nussenzweig R S, Nardin E H. Immunogenicity of an alum-adsorbed synthetic multiple-antigen peptide based on B- and T-cell epitopes of the Plasmodium falciparum CS protein: possible vaccine application. Vaccine. 1994;12:1012–1017. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang X D, Kaslow D C, Adams J H, Miller L H. Cloning of the Plasmodium vivax duffy receptor. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;44:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson H L, Tucker J E, Kaslow D C, Krettli A U, Collins W E, Kiefer M C, Bathurst I C, Barr P J. Structure and expression of the gene for Pv200, a major blood-stage surface antigen of Plasmodium vivax. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:325–334. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90230-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Høgh B, Marbiah N T, Burghaus P A, Andersen P K. Relationship between maternally derived anti-Plasmodium falciparum antibodies and risk of infection and disease in infants living in an area of Liberia, west Africa, in which malaria is highly endemic. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4034–4038. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4034-4038.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holder A A. The precursor to major merozoite surface antigens: structure and role in immunity. Prog Allergy. 1988;41:72–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui G S N, Chang S P, Gibson H, Hashimoto A, Hashiro C, Barr P J, Kotani S. Influence of adjuvants on the antibody specificity to the Plasmodium falciparum major merozoite surface protein, gp195. J Immunol. 1991;147:3935–3941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui G S N, Hashiro C, Nikaido C, Case S E, Hashimoto A, Gibson H, Barr P J, Chang S P. Immunological cross-reactivity of the C-terminal 42-kilodalton fragment of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 expressed in baculovirus. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3403–3411. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3403-3411.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter R L, Kidd M R, Olsen M R, Patterson P S, Lal A A. Induction of long-lasting immunity to Plasmodium yoelii malaria with whole blood-stage antigens and copolymer adjuvants. J Immunol. 1995;154:1762–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter, R. L., and A. A. Lal. 1994. Copolymer adjuvants in malaria vaccine development. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 50(Suppl.):52–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kalish M L, Check I J, Hunter R L. Murine IgG isotype responses to the Plasmodium cynomolgi circumsporozoite peptide (NAGG)5. I. Effects of carrier, copolymer adjuvants, and lipopolysaccharide on isotype selection. J Immunol. 1991;146:3583–3590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaslow D C, Kumar S. Expression and immunogenicity of the C-terminus of a major blood-stage protein of Plasmodium vivax Pv20019, secreted from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Immunol Lett. 1996;51:187–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenney J S, Hughes B W, Masada M P, Allison A C. Influence of adjuvants on the quantity, affinity, isotype and epitope specificity of murine antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 1989;121:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Yadava A, Keister D B, Tian J H, Ohl M, Perdue-Greenfield, Miller L H, Kaslow D C. Immunogenicity and in vivo efficacy of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in Aotus monkeys. Mol Med. 1995;1:325–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitus G, Del Portillo H A. Advances toward the development of an asexual blood stage MSP-1 vaccine of Plasmodium vivax. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1994;89:81–84. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761994000600019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling I T, Ogun S A, Momin P, Richards R L, Garcon N, Cohen J, Ballou W R, Holder A A. Immunization against the murine malaria parasite Plasmodium yoelii using a recombinant protein with adjuvants developed for clinical use. Vaccine. 1997;15:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long, C. A., T. M. Daly, P. Kima, and I. Srivastava. 1994. Immunity to erythrocytic stages of malarial parasites. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 50(Suppl.):27–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Majarian W, Daly R T M, Weidanz W P, Long C A. Passive immunization against murine malaria with an IgG3 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1984;132:3131–3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panina-Bordignon P, Tan A, Termijtelen A, Demotz S, Corradin G, Lanzavecchia A. Universally immunogenic T cell epitopes: promiscuous binding to human MHC class II and promiscuous recognition by T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2237–2242. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perea L, R. K L, Handunnetti S M, Holm I, Longacre S, Mendis K. Baculovirus merozoite surface protein 1 C-terminal recombinant antigens are highly protective in a natural primate model for human Plasmodium vivax malaria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1500–1506. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1500-1506.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pirson P J, Perkins M E. Characterization with monoclonal antibodies of a surface antigen of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. J Immunol. 1985;134:1946–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renia L, Ling I T, Marussig M, Miltgen F, Holder A A, Mazier D. Immunization with a recombinant C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 protects mice against homologous but not heterologous P. yoelii sporozoite challenge. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4419–4423. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4419-4423.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shai S, Blackman M J, Holder A A. Epitopes in the 19kDa fragment of the Plasmodium falciparum major merozoite surface protein-1 (PfMSP-119) recognized by human antibodies. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi Y P, Sayed U, Qari S H, Roberts J M, Udhayakumar V, Oloo A J, Hawley W A, Kaslow D C, Nahlen B L, Lal A A. Natural immune response to the C-terminal 19-kilodalton domain of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2716–2723. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2716-2723.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snewin V A, Khouri E, Wattavidanage J, Perera L, Premawansa S, Mendis K N, David P H. A new polymorphic marker for PCR typing of Plasmodium vivax parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;71:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00040-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sulzer A J, Wilson M, Hall E C. Indirect fluorescent antibody tests for parasitic disease. V. An evaluation of a thick-smear antigen in the IFA test for malarial antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takayama K, Olsen M, Datta P, Hunter R L. Adjuvant activity of non-ionic block copolymers V. modulation of antibody isotype by lipopolysaccharides, lipid and precursors. Vaccine. 1991;9:257–265. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90109-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor-Robinson A W, Phillips R S, Severn A, Moncada S, Liew F Y. The role of TH and TH2 cells in a rodent malaria infection. Science. 1993;260:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.8100366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ten Hagen T L M, Sulzer A J, Kidd M R, Lal A A, Hunter R L. Role of adjuvants in the modulation of antibody isotype, specificity, and induction of protection by whole blood-stage Plasmodium yoelii vaccines. J Immunol. 1993;151:7077–7085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian J H, Kumar S, Kaslow D C, Miller L H. Comparison of protection induced by immunization with recombinant proteins from different regions of merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium yoelii. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3032–3036. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3032-3036.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Triozzi P L, Stevens V C, Aldrich W, Powell J, Todd C W, Newman M. Effect of a β-human chorionic gonadotropin subunit immunogen administered in aqueous solution with a novel nonionic block copolymer adjuvant in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2355–2362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valmori D, Pessi A, Bianchi E, Corradin G. Use of human universally antigenic tetanus toxin T cell epitopes as carriers for human vaccination. J Immunol. 1992;149:717–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Wijgert J H H M, Verheul A F M, Snippe H, Check I J, Hunter R L. Immunogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 14 capsular polysaccharide: influence of carriers and adjuvants on isotype distribution. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2750–2757. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2750-2757.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang C, Collins W E, Xiao L, Patterson P S, Reed R C, Hunter R L, Kaslow D C, Lal A A. Influence of adjuvants on murine immune responses against the C-terminal 19 kDa fragment of Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) Parasite Immunol. 1996;18:547–558. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-32.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang C, Collins W E, Xiao L, Saekhou A M, Reed R C, Nelson C O, Hunter R L, Jue D L, Fang S, Wohlhueter R M, Udhayakumar V, Lal A A. Induction of protective antibodies in Saimiri monkeys by immunization with a multiple antigen construct (MAC) containing the Plasmodium vivax circumsporozoite protein repeat region and a universal T helper epitope of tetanus toxin. Vaccine. 1997;15:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]