Abstract

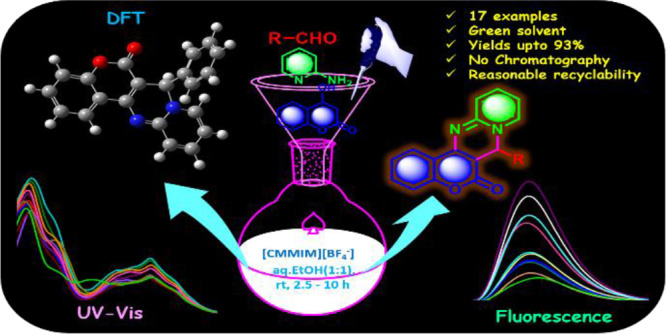

Herein, we have developed a novel synthetic route for the synthesis of chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one derivatives 8a-q using an acid ionic liquid [CMMIM][BF4–] 4 via one-pot, three-component synthesis in aqueous ethanol at room temperature. A series of 17 derivatives have been successfully prepared with up to 93% yield. All the synthesized derivatives were well characterized using 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and FT-IR spectral techniques. Additionally, the photophysical properties of 12 selected derivatives including molar extinction coefficient (ε), Stokes shift (Δυ̅), and quantum yield (Φ) varying from 0.52095 × 104 to 0.93248 × 104, 4216 to 4668 cm–1, and 0.0088 to 0.0459, respectively, have been determined. Furthermore, the experimental data are supported by density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT calculations. Theoretical investigations showed a trend similar to experimental results.

1. Introduction

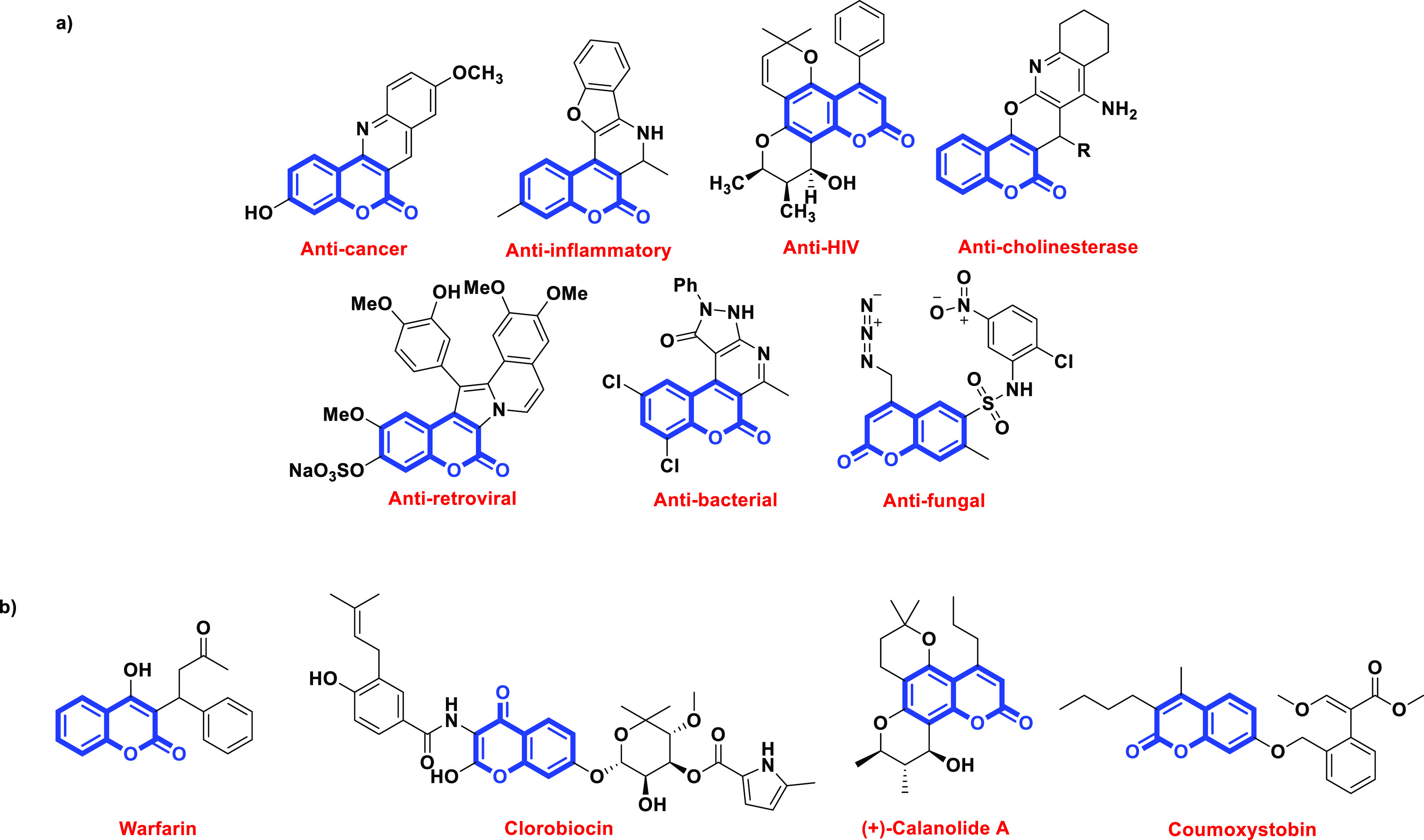

Naturally occurring and synthetic coumarin-fused heterocycles are widely used in several fields.1 Coumarin and its derivatives have received a lot of attention over the years because they are highly customizable molecules possessing a wide range of biological properties such as anti-inflammatory,2,3 anticoagulant,4 antifungal,5 antimicrobial,6,7 anticancer,8,9 antiviral,10,11 antitumor,12 antioxidant,13,14 antibacterial,15 antidiabetic,16 and anti-Alzheimer activities (Figure 1a).17 There are several reports available based on coumarins fused with different three-, four-, five-, and six-membered heterocycles like pyrazole, pyrrole, benzofuran, thiophene, and so on. The existence of two or more heterocyclic moieties in a single molecule can amplify or generate the target system’s biological properties and also exhibits interesting photophysical and pharmacokinetic characteristics when a heterocycle is fused to a coumarin unit.18−20 Pyrimidines have diverse intrinsic biological and medical attributes that include antiallergic, antipyretic, anticancer, antihypertensive, and so on, so that they can serve as attractive scaffolds and key frameworks in organic and medicinal chemistry.21,22 It is a prominent endogenous component of the body and its derivatives can facilitate the interaction with genetic material, enzymes, and other bio constituents inside the cell.23 Abundant reports have been made regarding the clinical uses of some of the fused coumarins (Figure 1b). So, research on the construction of several new catalogues of polyfunctionalized heterocycles including isoquinolino-, indolo-quinazolines, pyrans, and so on is of great importance.24−29

Figure 1.

(a) Biologically active fused coumarins and (b) marketed drugs based on the coumarin core.

Due to its significance in numerous domains, such as the industrial processes, environment, energy, and life sciences, catalysis continues to be a crucial field of chemistry. The key benefits of catalysis include furnishing the desired product more quickly, while utilizing fewer resources and producing less waste.30 Among the known catalysts, ionic liquids have piqued the interest of many researchers as it holds incredible potential for green chemistry applications. Ionic liquids are salts which are liquids composed of ions (organic cations and anions), but they are not the same as molten salts.31 In the chemical industries, homogeneous catalysis has many uses in comparison to the traditional heterogeneous catalytic systems.32 These catalysts provide several benefits, including high activity and selectivity, under benign working conditions.33 One of the most significant and often used task-specific ionic liquids (TSILs) is the acidic ionic liquid, which has one or more acidic activity sites in their structural design.33,34 TSILs currently hold a great deal of interest for researchers from a wide range of disciplines, particularly in the field of organic synthesis.35 TSILs have a variety of unique characteristics, including low toxicity, nonflammability, excellent thermal conductivity and solubility, low volatility, and reusability.36

Atom economy, cost-effectiveness, and rapid access to structural diversity are the significant features of multicomponent reactions (MCRs) over the conventional multi-step assembly.37 Given that they take into account both the diversity and convolution in organic synthesis, one-pot multi-component reactions are becoming more popular. Perks of the MCR include cost-effectiveness, ease of the process, a low E-factor, good atom economy, and complex product formation with a limited number of synthesis steps.38,39 Also, one-pot synthesis and usage of environmentally benign reaction media are highly desired as they conserve time, limit chemical waste generation, and make practical aspects simpler like purification.40,41 Several MCRs have previously been investigated by our research group.42−46

Previously, the synthesis of chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-ones is performed using sulfamic acid and NiFe2O4@SiO2-grafted di(3-propylsulfonic acid) nanoparticles. However, they do suffer from several limitations, such as excessive catalyst loading, prolonged reaction times under sonication, and harsh reaction conditions.47,48 It is much necessary to introduce an affordable, active, ecologically acceptable, and mild ionic liquid catalyst for MCRs. Additionally, there is a great need to develop creative strategies for reducing future environmental harm. Herein, to the best of our knowledge for the first time in our laboratory, we have performed a one-pot, multicomponent, acid ionic liquid-assisted synthesis of chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidinones. Additionally, we have successfully attempted to correlate the results from experimental photophysical studies with those from theoretical calculations.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

As it can be seen from Scheme 1, we have adopted a modified synthetic route for the synthesis of 3 by performing under neat conditions instead of using acetonitrile, followed by anion exchange that leads to 1-carboxymethyl 3-methyl imidazolium tetrafluoroborate ionic liquid 4.49−51 To 1-methylimidazole 1 (1.0 equiv), chloroacetic acid 2 (1.1 equiv) was added and allowed to stir for 2 h at 80 °C under neat conditions, and the crude was washed with a copious amount of ether to furnish [CMMIM][Cl–] ionic liquid 3. Furthermore, the obtained [CMMIM][Cl–] ionic liquid 3 was dissolved in 20 mL of dry acetonitrile with NaBF4 (1.1 equiv) added and then stirred at room temperature for 36 h. The resultant precipitate was filtered and washed with acetonitrile. The concentration of cumulative filtrates gave 1-carboxymethyl 3-methyl imidazolium tetrafluoroborate [CMMIM][BF4–] 4 as pale oil with 97% yield. The formed product was further characterized by 1H, 13C, 11B, and 19F NMR and FT-IR spectral techniques.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 1-Carboxymethyl 3-Methyl Imidazolium Tetrafluoroborate [CMMIM][BF4–] 4.

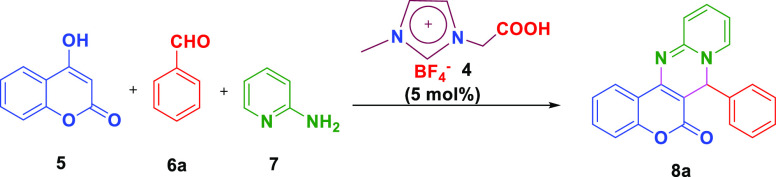

The catalytic activity of 4 was examined for the synthesis of 7-phenyl-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one derivatives 8a−q via a one-pot multi-component reaction between 4-hydroxy coumarin 5, various aromatic benzaldehydes 6, and 2-aminopyridine 7. Initially, for the optimization of the reaction, 4-hydroxy coumarin 5, benzaldehyde 6a, and 2-aminopyridine 7 were taken as model substrates by employing 5 mol % of ionic liquid 4. The preliminary investigation began to determine the most suitable solvent for the reaction (Table 1). Using polar aprotic solvents such as acetonitrile (CH3CN), dimethylformamide (DMF), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) did not furnish any desired product 7a even after 24 h (Table 1, entries 1, 3, and 5). The model reaction did not proceed in chlorinated solvents like dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and chloroform (CHCl3) (Table 1, entries 6 and 7).

Table 1. Solvent Screening for the Synthesis of 8aa.

| entry | solvent | time (h) | yieldb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH3CN | 24 | n.r. |

| 2 | IPA | 24 | 27 |

| 3 | DMF | 24 | n.r. |

| 4 | EtOH | 24 | 70 |

| 5 | THF | 24 | n.r. |

| 6 | DCM | 24 | n.r. |

| 7 | CHCl3 | 24 | n.r. |

| 8 | H2O | 24 | 39 |

| 9 | MeOH | 24 | 61 |

| 10 | solvent-free | 24 | 25 |

| 11c | neat | 12 | 46 |

| 12 | EtOH:H2O (1:1 v/v: 5 mL) | 5.5 | 78 |

| 13 | EtOH:H2O (1:1 v/v: 10 mL) | 2.5 | 93 |

| 14 | EtOH:H2O (1:2 v/v: 10 mL) | 5 | 75 |

| 15 | EtOH:H2O (2:1 v/v: 10 mL) | 7 | 69 |

Reaction conditions: 5 (1 equiv), 6a (1 equiv), and 7 (1 equiv) at room temperature. 5 mol % catalyst.

Yield of the isolated product.

60 °C. n.r.—no reaction

Interestingly, when the reaction was carried out in polar protic solvents such as IPA, MeOH, and EtOH, the yield of the desired product 8a substantially enhanced up to 70% (Table 1, entries 2, 9, and 4). However, in the water medium, only 39% yield of the product 8a was observed (Table 1, entry 8). Also, when the reaction was performed in the absence of solvent at room temperature and 60 °C for 24 and 12 h, respectively, product 8a was obtained in low yields (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). From the observations made from screening results, to maximize the yield and reduce reaction time, we then carried out the reaction in aqueous ethanol by varying both the volumetric ratios of and the amount of solvent utilized in the reaction (Table 1, entries 12–15). Out of all, 93% yield of the required product 8a was furnished in 2.5 h at room temperature with 5 mol % ionic liquid 4 in 10 mL of EtOH:H2O (1:1; v/v) (Table 1, entry 13).

Furthermore, the impact of the amount of the catalyst was assessed and the results are presented in Table 2. It is evident that 5 mol % of [CMMIM][BF4–] 4 afforded the product in high yields under optimized conditions. There was no substantial increment in the yield of the product 8a or effect on time even after supplementing an additional amount of catalyst (Table 2, entries 1–9).

Table 2. Optimization of Catalystsa.

| entry | catalyst | time (h) | yieldb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | no catalyst | 15 | 41 |

| 2 | p-TSA (20 mol %) | 24 | 57 |

| 3 | H2SO4 (20 mol %) | 24 | 62 |

| 4 | CH3COOH (20 mol %) | 24 | 53 |

| 5 | [CMMIM][BF4–] (2 mol %) | 12 | 65 |

| 6 | [CMMIM][BF4–] (5 mol %) | 2.5 | 93 |

| 7 | [CMMIM][BF4–] (7.5 mol %) | 2.5 | 93 |

| 8 | [CMMIM][BF4–] (10 mol %) | 2.5 | 93 |

| 9 | [CMMIM][BF4–] (15 mol %) | 2.0 | 93 |

One-pot reaction between 5 (1 equiv), 6a (1equiv), and 7 (1 equiv) at rt in aq. EtOH(1:1).

Yield of the isolated product.

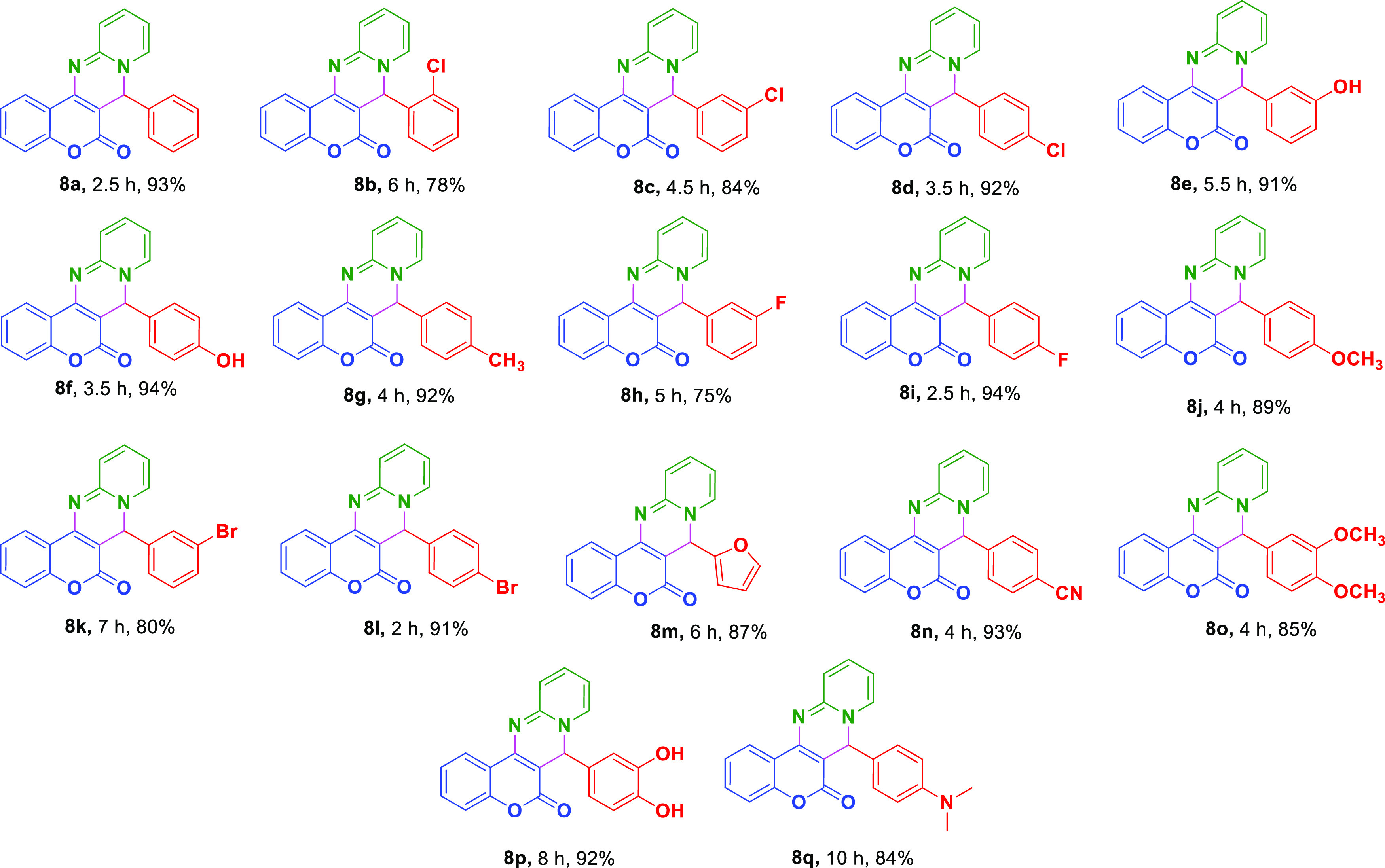

Under these optimized conditions, exploration of the scope and limitations of the reaction was carried out by utilizing aldehydes 6a-q containing various electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Substituted chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one derivatives.

Aromatic aldehydes containing electron-withdrawing groups like −Cl, −Br, −F, and −CN at different positions afforded corresponding products in good to excellent yields (79–94%) with little variation in reaction times. Unfortunately, when −NO2-substituted benzaldehydes were employed, the reaction did not proceed to yield the corresponding product. Fourth position-substituted electron-donating −CH3, OCH3, −OH, and −N(CH3)2 moieties on benzaldehydes also gave respective desired products in high yields. Besides, heteroaryl aldehyde like furaldehyde and di-substituted aromatic aldehydes too yielded corresponding products 8m, 8o, and 8p in notable yields at room temperature but with a slight increase in reaction time (10 h) in the case of 6q (Table 3, entries 13, 15, and 16). Regrettably, aliphatic aldehydes such as acetaldehyde, propionaldehyde, and butyraldehyde could not furnish any desired products under optimized conditions (Table 3, entries 18–20). To examine the versatility of this multi-component reaction, we have also carried out the reaction using sterically crowded aldehydes like 3,4,5-trimethoxy benzaldehyde, 3-OC2H5, 4-OH benzaldehyde, naphthaldehyde, 2,5-(OCH3)2 benzaldehyde, and 9-julolidine carboxaldehyde but unfortunately did not furnish any desired products; rather bis-coumarins were obtained in few cases (Table 3). All the products are acquired by simple filtration of the resulting reaction mixture, followed by washing the precipitate with hexane and drying under vacuum affording 8a-q. The formed products were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and FT-IR and were verified to be identical to those reported in the literature.

Table 3. Substrate Scope for Several Chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one Derivatives 8a-qa.

| entry | substituent (R) | product | time (h) | yieldb (%) | melting

point (°C) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| determined | reported47,48 | |||||

| 1 | C6H5 | 8a | 2.5 | 93 | 206–208 | 211–212 |

| 2 | 2-ClC6H4 | 8b | 6 | 78 | 238–240 | 242–244 |

| 3 | 3-ClC6H4 | 8c | 4.5 | 84 | 179–181 | 177–178 |

| 4 | 4-ClC6H4 | 8d | 3.5 | 92 | 236–238 | 255–257 |

| 5 | 3-OHC6H4 | 8e | 5.5 | 71 | 147–149 | new |

| 6 | 4-OHC6H4 | 8f | 3.5 | 94 | 156–158 | 157–158 |

| 7 | 4-CH3C6H4 | 8g | 4 | 92 | 225–227 | 229–230 |

| 8 | 3-FC6H4 | 8h | 5 | 75 | 201–203 | new |

| 9 | 4-FC6H4 | 8i | 2.5 | 94 | 218–220 | 224–225 |

| 10 | 4-OCH3C6H4 | 8j | 4 | 89 | 223–225 | 206–207 |

| 11 | 3-BrC6H4 | 8k | 7 | 80 | 205–207 | new |

| 12 | 4-BrC6H4 | 8l | 2 | 91 | 235–237 | 240–242 |

| 13 | 2-furyl | 8m | 6 | 87 | 171–173 | 175–176 |

| 14 | 4-CNC6H4 | 8n | 4 | 93 | 218–220 | 228–229 |

| 15 | 3,4-(OCH3)2 C6H3 | 8o | 4 | 85 | 208–210 | 215–216 |

| 16 | 3,4-(OH)2C6H3 | 8p | 8 | 92 | 177–179 | 180–181 |

| 17 | 4-N(CH3)2C6H4 | 8q | 10 | 84 | 181–183 | 182–183 |

| 18 | acetaldehyde | 18 | n.r. | |||

| 19 | propionaldehyde | 18 | n.r. | |||

| 20 | butyraldehyde | 18 | n.r. | |||

One-pot reaction performed using 5 (1 equiv), 6 (1 equiv), and 7 (1 equiv) at room temperature in aq. EtOH (1:1). 5 mol % catalyst.

Yield of the isolated product. n.r.—no reaction

Furthermore, exploiting the model reaction under optimized conditions, we assessed the efficiency of this strategy in gram-scale synthesis. 10 mmol 4-hydroxy coumarin 5, 10 mmol benzaldehyde 6a, and 10 mmol 2-amino pyridine 7 in the presence of 5 mol % [CMMIM][BF4–] 4 furnished 7-phenyl-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8a with 90% yield (2.94 g) in 2.5 h (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. One-Pot Gram-Scale Synthesis of 7-Phenyl-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8a Using [CMMIM][BF4–] 4.

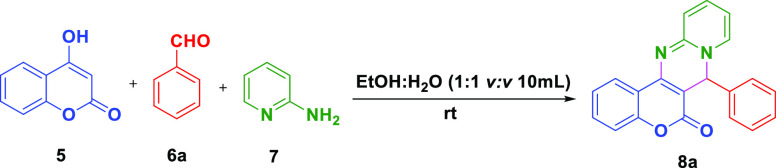

2.2. Plausible Reaction Mechanism

A plausible reaction mechanism has been proposed based on previous literature.48 Step 1 involves the formation of chalcone I via condensation between 4-hydroxycoumarin 5 and aldehyde 6, and a new C–C bond formation occurs, which leads to the formation of II by elimination of water. In step 2, II undergoes a nucleophilic attack by 2-aminopyridine 7 and generates III, which undergoes keto-enol tautomerization to form IV. Furthermore, in step 3, this IV shall undergo a simple intramolecular ring closure to give the adduct V that affords the corresponding desired products 8a-q on the removal of water (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Plausible reaction mechanism.

Since the employed ionic liquid 4 is hydrophilic, it is completely soluble in aqueous ethanol. Subsequently, the filtrate containing the catalyst obtained from the resultant mixture is further reused up to two runs for the reaction (Table 3, entry 1) and the product 8a was obtained at nearly the same time with no discernible decrease in yield.

2.3. Photophysical Studies

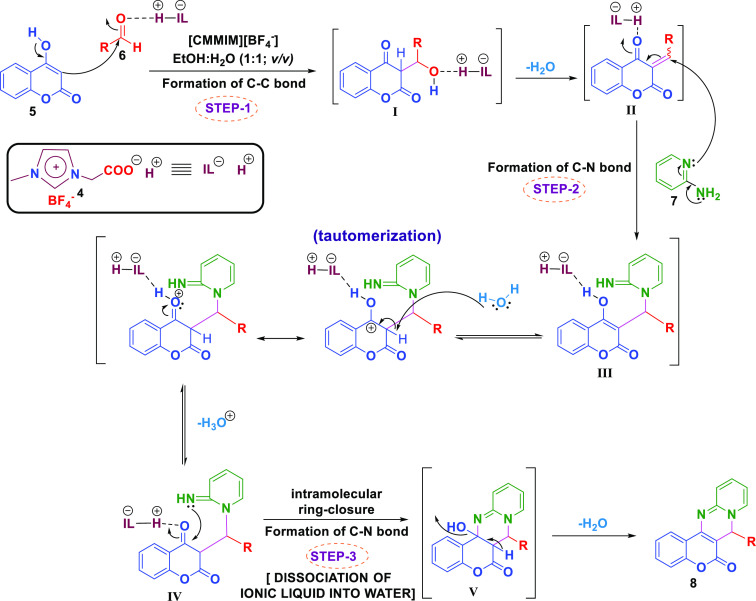

The utility of the prepared compounds was highlighted by measuring their emission spectra at 50 μM concentration in acetonitrile (Figure 4). Initially, UV–visible spectra have been recorded for 12 selected derivatives based on the substituted moieties on the aryl ring. Two major transitions were observed, namely, a higher energy π–π* electronic transition (intramolecular charge transfer) in the region 203–215 nm and a lower energy n−π* electronic transition in the region 300–315 nm. In addition, theoretically computed absorption values are comparable with experimentally obtained n−π* transition for selected derivatives that are in the range of 325–336 nm. So, it is evident that the solvent shows a minimum effect in theoretical studies. The solutions of these compounds were excited individually at their respective n−π* absorption maxima (300 to 315 nm) in CH3CN under identical conditions. In this series, 8o is strongly emissive due to the attachment of two strong electron-donating −OCH3 groups on the ring.

Figure 4.

(a) UV–vis and (b) fluorescence spectra of selected chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a] pyrimidin-6-one derivatives at 50 μM concentration in acetonitrile.

However, in the case of 8q having −N(CH3)2 as a substituent, it exhibited low emission intensity compared to the other compounds. The unanticipated loss in the fluorescence intensity may be due to the inhibition of electron delocalization.52 Interestingly, 8g and 8n containing −CH3 and −CN groups displayed very similar emission intensities. Other compounds in this series containing halogens (8d, 8i, and 8l) or −OH (8f and 8p) or furyl (8m) have a similar pattern in their fluorescence behavior with moderate emission intensities. Additionally, the molar extinction coefficient (ε) was determined using Lambert–Beer’s law. It is observed that 8l has the highest 0.93248 × 104 value, whereas 8a has the least 0.52095 × 104 molar extinction coefficient value (Table 4).

Table 4. Experimental Photophysical Data of Selected Chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-ones.

| entry | compound | absorptiona λmax,abs (nm) | emissiona λmax,emi (nm) | molar extinction coefficient × 104 (ε) n−π* | Stokes shift Δυ̅ (cm–1) | quantum yield (Φ)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8a | 208, 305 | 350 | 0.52095 | 4216 | 0.0403 |

| 2 | 8d | 209, 305 | 352 | 0.63869 | 4378 | 0.0213 |

| 3 | 8f | 208, 305 | 353 | 0.63414 | 4458 | 0.0186 |

| 4 | 8g | 212, 305 | 352 | 0.88867 | 4378 | 0.0125 |

| 5 | 8i | 210, 305 | 353 | 0.75602 | 4458 | 0.0176 |

| 6 | 8j | 212, 305 | 352 | 0.62899 | 4378 | 0.0363 |

| 7 | 8l | 212, 305 | 353 | 0.93248 | 4458 | 0.0088 |

| 8 | 8m | 210, 304 | 352 | 0.59099 | 4486 | 0.0459 |

| 9 | 8n | 206, 305 | 352 | 0.64208 | 4378 | 0.0357 |

| 10 | 8o | 210, 306 | 351 | 0.81409 | 4190 | 0.0386 |

| 11 | 8p | 210, 305 | 353 | 0.75602 | 4458 | 0.0148 |

| 12 | 8q | 208, 306 | 357 | 0.60639 | 4668 | 0.0124 |

Recorded at 300 K in CH3CN.

Calculated with Tryptophan as a reference standard (Φst = 0.16).

Furthermore, Stokes shift values and quantum yield for the n−π* transition are calculated for the same selected series of derivatives using eqs 2 and 3 as stated in the experimental section. All the selected compounds have fairly comparable Stokes shift values. It is noted that 8d, 8g, 8j, and 8n possess a similar Stokes shift value (4378 cm–1). Also, 4458 cm–1 is Stokes shift of 8f, 8i, 8l, and 8p. Among all, 8q has the highest (4668 cm–1) and 8a has the least (4216 cm–1) Stokes shift values. The obtained results suggest that there is no huge difference in Stokes shift values (4216–4668 cm–1) among all of the selected compounds.

The quantum yield of the selected compounds was calculated with Tryptophan in 0.1 M NaOH (Φst = 0.16) excited at 275 nm as reference according to eq 3 as specified in the Section 4.53 The quantum yield of the selected compounds varied from 0.0088 to 0.0459. The complete photophysical results are tabulated in Table 4.

2.4. Density Functional Theory and Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory Studies

We have carried out computational studies to understand the reason behind the very similar values of λmax,abs and λmax,emi between the synthesized derivatives. Becke’s three-parameter and Lee–Yang–Parr (B3LYP) functional with 6-31G (d,p) was used to determine the HOMO and LUMO energy levels of selected derivatives (Figure 5).54,55 The calculated energy gap between HOMO and LUMO approximately ranges from 3.45 to 4.29 eV for the selected compounds. It is noticed that methyl-substituted derivative 8g has the highest energy gap of 4.29 eV. Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations were used to determine the theoretical absorption maxima and oscillator strength in the gas phase. To illustrate this, 8a shows two absorption peaks at 283.38 and 326.8, which are due to key electronic transitions produced from (i) 72% of HOMO–1 to LUMO+1 and (ii) 87% of HOMO–1 to LUMO, respectively (see Table S2). The deduced computational data are tabulated in Table 5. All of them have a very similar band gap (eV) and λmax of absorption. So, the attained theoretical results validate that there is not much effect of substitution on the absorption values and are in great accordance with experimental data. The frontier molecular orbitals of selected derivates are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Frontier molecular orbitals of HOMO and LUMO in selected chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-ones using the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory.

Table 5. Theoretical Calculation of HOMO, LUMO, and Energy Gap for Selected Derivatives Using 6-31G (d,p) Level of Theory in the Gas Phase.

| entry | sample code | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | energy gap (eV) | theoretical absorption λmax (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8a | –5.4896 | –1.8591 | 3.63 | 327 |

| 2 | 8d | –5.6121 | –1.9916 | 3.62 | 330 |

| 3 | 8f | –5.4458 | –1.8166 | 3.63 | 336 |

| 4 | 8g | –6.1076 | –1.8210 | 4.29 | 326 |

| 5 | 8i | –5.5699 | –1.9317 | 3.64 | 327 |

| 6 | 8j | –5.4121 | –1.7864 | 3.62 | 325 |

| 7 | 8l | –5.6295 | –1.9919 | 3.63 | 329 |

| 8 | 8m | –5.5642 | –1.8526 | 3.71 | 335 |

| 9 | 8n | –5.8047 | –2.1758 | 3.63 | 334 |

| 10 | 8o | –5.3982 | –1.7701 | 3.63 | 324 |

| 11 | 8p | –5.4028 | –1.7701 | 3.63 | 325 |

| 12 | 8q | –5.1179 | –1.6683 | 3.45 | 323 |

3. Conclusions

In this present work, we have established a novel green methodology for the synthesis of chromeno[4,3-d] pyrido[1,2-a] pyrimidin-6-ones 8a-q by utilizing [CMMIM][BF4–] 4 via a one-pot multi-component reaction between 4-hydroxycoumarin 5, aromatic aldehydes 6, and 2-aminopyridines 7 in aqueous ethanol at room temperature. The salient features of this approach comprise an eco-friendly catalyst, mild reaction conditions, a metal-free synthesis, easy-workup procedure without any column chromatographic separation and minimal catalyst loading mole percentage. All the 17 synthesized products were obtained in moderate to high yields. A plausible mechanism comprising of intermediates and adducts has been proposed. The catalyst can be reused for up to at least 2 cycles. Photophysical properties of 12 selected derivatives have been estimated, out of which 8l, 8q, and 8m have the highest molar extinction coefficient (ε), Stokes shift (Δυ̅), and quantum yield (Φ), respectively. Furthermore, we have calculated the theoretical energy gap between HOMO–LUMO energy levels by DFT using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) and performed TD-DFT studies in the gas phase. Theoretically computed results and experimental data are in good agreement with each other. Currently, the synthetic utility of the obtained compounds is under investigation in our laboratory.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials and Methods

4-Hydroxy coumarin, substituted aromatic aldehydes, 2-amino pyridine, methylimidazole, 2-chloro acetic acid, and sodium tetrafluoroborate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and organic solvents were procured from commercial suppliers and used without any further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out using 0.25 mm silica gel-coated Kieselgel 60 F254 plates. 1H NMR (400 MHz), 13C NMR (100 MHz), 19F NMR (100 MHz), and 10B NMR (128 MHz) spectra were measured on a Bruker DRX400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts and coupling constants are specified in parts per million (ppm) and Hertz (Hz), respectively, using tetra-methyl silane as an internal standard and the solvent resonance at (DMSO-d6: 1H NMR 400 MHz and 13C NMR 100 MHz): δ 2.49 and 39.7 ppm. The peak multiplicities are allocated as s (singlet), d (doublet), dd (doublet of doublet), dt (doublet of triplet), and m (multiplet). FT-IR spectra were recorded using a IRAffinity (SHIMADZU) and Nicolet iS50 (Thermo Scientific) spectrometer on a KBr disc. UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded on a JASCO V-670 spectrophotometer at room temperature in acetonitrile. A Hitachi F-7000 FL spectrophotometer was utilized to record emission fluorescence spectra by excitation at their respective absorption maxima.

4.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 1-Carboxymethyl 3-Methyl Imidazolium Tetrafluoroborate 4

In a 250 mL round bottom flask, to 1-methylimidazole 1 (2.0 g, 1.0 equiv, 2.43 mmol), chloroacetic acid 2 (2.5 g, 1.1 equiv, 2.68 mmol) was added and allowed to stir for 2 h at 80 °C under neat conditions. Later, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool, and the pale-yellow viscous liquid was washed with ether several times and then dried under vacuum. Furthermore, the obtained [CMMIM][Cl–] ionic liquid 3 was dissolved in 20 mL of dry acetonitrile, charged with NaBF4 (2.94 g, 1.1 equiv, 2.68 mmol), and stirred at room temperature for 36 h. The resultant white precipitate (NaCl) was filtered and washed thoroughly with acetonitrile (3 × 30 mL). The concentration of cumulative filtrates gives 1-carboxymethyl 3-methyl imidazolium tetrafluoroborate [CMMIM][BF4–] 4 as pale oil with 97% yield. The product was characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and FT-IR spectra and was observed to be the same as those described in the literature.

4.3. Representative General Procedure for the Synthesis of 7-Phenyl-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8a

To a dried 100 mL round bottom flask, 4-hydroxy coumarin 5 (0.2 g, 1 equiv, 1.23 mmol), benzaldehyde 6a (0.14 mL, 1 equiv, 1.35 mmol), 2-aminopyridine 7 (0.12 g, 1 equiv, 1.23 mmol), and 5 mol % [CMMIM][BF4–] ionic liquid 4 were added successively to 10 mL of aqueous ethanol (1:1 v/v) and stirred at room temperature for 2.5 h. The progress of the reaction was supervised by TLC. After the completion of the reaction, the formed solid precipitate was filtered out and washed with ether (10 mL × 2) without any column chromatography to furnish the desired product 8a with 93% (0.38 g) yield. The furnished products were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and FT-IR spectra and were observed to be the same as those described in the literature.

4.4. Computational Details

To comprehend the structural and functional aspects, calculations based on the DFT were made. The DFT-based calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16W.56 The geometries of selected compounds in the gaseous phase were optimized using the B3LYP functional.54 The B3LYP functional was combined with the 6-31G basis set for all the calculations.55 On the optimized geometries, TD-DFT calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) level of theory in the gas phase. The geometries and frontier molecular orbital structures were depicted by using the Gauss View 6.1 molecular visualization program.57

4.5. General Information

The molar extinction coefficient (ε) was determined using Beer–Lambert’s law using eq 1

| 1 |

where A is the absorbance, ε is the molar absorption coefficient, c is the concentration of the sample, and l is the distance traveled by the light through the sample.

2. The Stokes Shift was evaluated using eq 2

| 2 |

3. The photoluminescence quantum yields (Φ) of the selective compounds in CH3CN solution were calculated with reference to Tryptophan (Φst = 0.16 in 0.1 M H2SO4) by using eq 3

| 3 |

where subscripts “x” and “R” stand for unknown and reference (Tryptophan), respectively, Φ is the quantum yield, I is the area under the fluorescence spectra on an energy scale, A is absorbance, and η stands for the refractive index of the solvent.

4.5.1. 1-Carboxymethyl 3-Methyl Imidazolium Tetrafluoroborate [CMMIM][BF4–] 4(50,58)

Pale yellow liquid (97% yield); FT-IR (ATR, cm–1): 3168, 1741, 1176, 1026, 756, 624, 520; 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O, ppm) δ 8.26 (s, 1H), 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 5.01 (s, 2H), 3.81 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O, ppm) δ 169.96, 137.29, 123.45, 49.91, 35.92. 19F NMR (400 MHz, D2O, ppm) δ −150.27, −150.33. 11B NMR (128 MHz, D2O, ppm) δ −1.39.

4.5.2. 7-Phenyl-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8a(48)

White solid (93% yield); mp (°C): 206–208; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3335, 3109, 1659, 1595, 1535, 1493, 1279, 1105, 899, 758; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.86–7.83 (m, 2H), 7.74 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (dt, J = 8.7, 7.3, 1.7 and 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.4 and 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.05–6.96 (m, 2H), 6.90 (dd, J = 9.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.82–6.77 (m, 1H), 6.20 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.14, 165.02, 154.46, 152.99, 144.50, 142.87, 136.73, 131.35, 128.15, 127.13, 125.25, 124.59, 123.32, 120.41, 115.92, 113.79, 112.62, 103.87, 36.60.

4.5.3. 7-(2-Chlorophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8b(47)

White solid (78% yield); mp (°C): 238–240; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3111, 1663, 1597, 1547, 1400, 1275, 1186, 1005, 997, 748; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.88–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.74 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (dt, J = 8.5, 6.9, 1.7 and 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (dd, J = 7.6, 3.2 Hz, 3H), 7.12 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.9 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.81–6.76 (m, 1H), 6.08 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.14, 164.32, 154.51, 152.89, 144.44, 140.88, 136.82, 133.16, 131.29, 130.84, 129.80, 127.50, 126.44, 124.51, 123.36, 120.38, 115.91, 113.75, 112.62, 103.23, 36.58.

4.5.4. 7-(3-Chlorophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8c(48)

White solid (84% yield); mp (°C): 179–181; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3318, 1663, 1601, 1537, 1377, 1278, 1163, 1055, 943, 758; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.87–7.83 (m, 2H), 7.75 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (dt, J = 8.6, 7.2, 1.7 and 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.07 (m, 5H), 6.99 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.81–6.78 (m, 1H), 6.20 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.26, 164.88, 154.38, 152.99, 145.38, 144.60, 136.56, 133.02, 131.57, 130.12, 126.77, 126.01, 125.42, 124.63, 123.46, 120.23, 116.01, 113.87, 112.62, 103.35, 36.56.

4.5.5. 7-(4-Chlorophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8d(48)

White solid (92% yield); mp (°C): 236–238; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3348, 3134, 1665, 1595, 1530, 1275, 1109, 853, 754; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.88–7.82 (m, 2H), 7.74 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (dt, J = 8.6, 7.3, 1.6 and 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.07 (m, 5H), 6.99 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.92–6.87 (m, 1H), 6.81–6.76 (m, 1H), 6.17 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.20, 164.89, 154.49, 153.00, 144.47, 141.97, 136.78, 131.48, 129.82, 129.03, 128.09, 124.60, 123.39, 120.30, 115.96, 113.77, 112.62, 103.59, 36.25.

4.5.6. 7-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8e(48)

Light-brown solid (71% yield); mp (°C): 147–149; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3375, 3154, 1659, 1595, 1541, 1352, 1180, 1059, 926, 756; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 9.00 (s, 1H), 8.01–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.87 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.04–6.95 (m, 1H), 6.94–6.89 (m, 1H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (dd, J = 7.9, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.24 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.15, 165.07, 157.39, 154.45, 152.95, 144.50, 136.72, 131.36, 128.93, 124.61, 123.35, 120.43, 115.91, 114.15, 113.78, 112.63, 103.89, 36.48.

4.5.7. 7-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8f(48)

White solid (94% yield); mp (°C): 156–158; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3377, 3142, 1663, 1597, 1506, 1231, 1167, 1055, 951, 758; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 8.92 (s, 1H), 7.94–7.87 (m, 2H), 7.80 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.51–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.18 (m, 3H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.89–6.81 (m, 4H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (s, 1H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 170.21, 167.24, 157.30, 156.76, 155.17, 146.62, 139.06, 135.02, 133.41, 130.22, 126.77, 125.45, 122.74, 118.06, 117.17, 115.95, 114.84, 106.50, 38.02.

4.5.8. 7-(p-Tolyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8g(48)

White solid (92% yield); mp (°C): 225–227; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3354, 3161, 1651, 1595, 1535, 1398, 1182, 1105, 855, 758; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.89–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.73 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (dt, J = 8.6, 7.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.11 (m, 3H), 6.93–6.86 (m, 4H), 6.82–6.76 (m, 1H), 6.15 (s, 1H), 2.15 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.07, 165.01, 154.45, 152.97, 144.52, 139.72, 136.71, 133.92, 131.30, 128.75, 127.05, 124.56, 123.30, 120.44, 115.90, 113.80, 112.62, 104.02, 36.24, 20.98.

4.5.9. 7-(3-Fluorophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8h

Off-white solid (75% yield); mp (°C): 201–203; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3362, 3156, 1655, 1599, 1539, 1443, 1234, 1182, 1105, 866, 754; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.86–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.76 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (dt, J = 8.7, 7.2, 1.7 and 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.11 (m, 4H), 6.9–6.74 (m, 4H), 6.22 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.30, 164.96, 163.99, 161.59, 154.53, 153.01, 146.33, 146.26, 144.37, 136.85, 131.53, 129.99, 129.91, 124.63, 123.43, 123.26, 120.28, 115.99, 113.82, 113.72, 113.60, 112.59, 112.20, 111.99, 103.51, 36.61.

4.5.10. 7-(4-Fluorophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8i(48)

White solid (94% yield); mp (°C): 218–220; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3354, 3169, 1659, 1595, 1504, 1327, 1127, 1103, 858, 758; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 8.00–7.94 (m, 2H), 7.86 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (dt, J = 8.6, 7.3, 1.6 and 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.16–7.13 (m, 1H), 7.06–6.99 (m, 2H), 6.94–6.89 (m, 1H), 6.29 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.22, 164.99, 161.81, 159.42, 154.37, 152.99, 144.57, 138.73, 138.70, 136.54, 131.46, 128.84, 128.76, 124.60, 123.39, 120.34, 115.96, 114.85, 114.64, 113.87, 112.59, 103.87, 36.06.

4.5.11. 7-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8j(48)

White solid (89% yield); mp (°C): 223–225; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3341, 3117, 1651, 1595, 1506, 1250, 1184, 1036, 901, 756; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.86–7.83 (m, 2H), 7.74 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (dt, J = 8.7, 7.3, 1.7 and 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.12 (m, 3H), 6.95–6.88 (m, 3H), 6.82–6.77 (m, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.13 (s, 1H), 3.61 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.05, 165.00, 157.25, 154.46, 152.96, 144.50, 136.72, 134.59, 131.29, 128.08, 124.56, 123.29, 120.45, 115.89, 113.79, 113.58, 112.62, 104.14, 55.34, 35.84.

4.5.12. 7-(3-Bromophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8k

Off-white solid (80% yield); mp (°C): 205−207; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3325, 3115, 1661, 1597, 1537, 1377, 1105, 1036, 943, 758; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.97 (m, 2H), 7.88 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.60–7.54 (m, 1H), 7.36–7.14 (m, 6H), 7.0200 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.93–6.88 (m, 1H), 6.32 (s, 1H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.30, 164.90, 154.39, 152.97, 146.05, 144.56, 136.60, 131.61, 130.50, 129.62, 128.34, 126.40, 124.63, 123.50, 121.81, 120.20, 116.03, 113.84, 112.62, 103.33, 36.53.

4.5.13. 7-(4-Bromophenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8l(48)

White solid (91% yield); mp (°C): 235–237; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3345, 3138, 1665, 1595, 1526, 1402, 1180, 1007, 851, 754; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.98–7.94 (m, 2H), 7.86 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.60–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.26 (m, 3H), 7.12–7.07 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.94–6.88 (m, 1H), 6.26 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.25, 164.95, 154.44, 153.00, 144.48, 142.43, 136.68, 131.51, 131.02, 129.50, 124.61, 123.42, 120.30, 118.29, 115.98, 113.80, 112.59, 103.56, 36.33.

4.5.14. 7-(Furan-2-yl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8m(48)

Brown solid (87% yield); mp (°C): 171–173; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3316, 3105, 1678, 1659, 1593, 1535, 1408, 1190, 997, 816, 756; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.99–7.86 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (dd, J = 9.8, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (dd, J = 3.1, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.24 (s, 1H), 5.97–5.92 (m, 1H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.25, 164.51, 155.58, 154.56, 152.95, 144.38, 140.98, 136.93, 131.46, 124.61, 123.37, 120.31, 115.94, 112.61, 110.39, 105.60, 102.28, 32.09.

4.5.15. 4-(6-Oxo-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-7-yl)benzonitrile 8n(48)

White solid (93% yield); mp (°C): 218–220; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3169, 1663, 1593, 1530, 1408, 1182, 1038, 905, 762; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 8.01–7.93 (m, 2H), 7.86 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.55 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.30 (m, 4H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (dd, J = 9.7, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.36, 165.86, 153.00, 149.43, 144.50, 136.72, 132.27, 131.69, 128.19, 124.62, 123.52, 120.13, 116.04, 113.77, 112.63, 108.14, 103.12, 37.15.

4.5.16. 7-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8o(48)

Off-white solid (85% yield); mp (°C): 208–210; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 2931, 1647, 1595, 1508, 1404, 1325, 1230, 1028, 810, 756; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.92 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 4H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (dd, J = 15.2, 7.8 Hz, 4H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.70–6.60 (m, 2H), 6.21 (s, 1H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 3.52 (s, 3H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.15, 165.01, 154.43, 152.94, 148.68, 147.04, 144.51, 136.66, 135.36, 131.30, 124.58, 123.33, 120.44, 119.40, 115.91, 113.81, 112.60, 119.99, 118.87, 104.13, 55.96, 55.93, 36.19.

4.5.17. 7-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8p(48)

Pale-pink solid (92% yield); mp (°C): 177–179; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3377, 3146, 1661, 1593, 1504, 1406, 1234, 1107, 930, 756; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 7.97–7.86 (m, 2H), 7.82 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.51–7.47 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.19 (m, 3H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.87–6.83 (m, 1H), 6.54–6.49 (m, 1H), 6.36–6.33 (m, 1H), 6.13 (s, 1H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.04, 165.09, 154.44, 152.93, 144.92, 144.49, 142.93, 136.69, 133.52, 131.24, 124.58, 123.28, 120.53, 117.78, 115.86, 115.39, 114.81, 113.79, 112.61, 104.27, 35.81.

4.5.18. 7-(4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl)-6H,7H-chromeno[4,3-d]pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-6-one 8q(48)

Off-white solid (84% yield); mp (°C): 181–183; FT-IR (KBr, cm–1): 3350, 2167, 1663, 1601, 1530, 1406, 1277, 1182, 1038, 851, 754; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 7.92 (m, 2H), 7.81 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 7.54–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.29–7.20 (m, 4H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.90–6.83 (m, 1H), 6.23 (s, 1H), 2.97 (s, 6H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 168.07, 164.99, 154.36, 152.97, 144.61, 136.52, 131.39, 128.16, 124.56, 123.35, 120.36, 116.43, 115.94, 113.88, 112.61, 103.91, 36.03.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the DST-Govt of India for the funding provided through DST-SERB-YSS/2015/000450, the Chancellor of VIT for providing an opportunity to carry out this study, and VIT for providing the “VIT SEED GRANT” for carrying out this research work. We sincerely acknowledge the VIT-SIF for providing the instrumental facilities. The authors thank Dr. R. Bhaskar (Research Associate-ICMR, SAS, VIT, Vellore) for his insights into photophysical and DFT studies.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c05015.

1H NMR, 13C NMR, and FT-IR spectra of ionic liquid 4 and synthesized compounds 8a-q, frontier molecular orbitals of HOMO and LUMO energy levels, and theoretical UV–vis characteristics of selected derivatives (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Patel G.; Banerjee S. Review on Synthesis of Bio-Active Coumarin-Fused Heterocyclic Molecules. Curr. Org. Chem. 2020, 24, 2566–2587. 10.2174/1385272824999200709125717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal Y.; Sethi P.; Bansal G. Coumarin: A Potential Nucleus for Anti-Inflammatory Molecules. Med. Chem. Res. 2013, 22, 3049–3060. 10.1007/s00044-012-0321-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grover J.; Jachak S. M. Coumarins as Privileged Scaffold for Anti-Inflammatory Drug Development. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 38892–38905. 10.1039/C5RA05643H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haziri A.; Mazreku I.; Rudhani I. Anticoagulant Activity of Coumarin Derivatives. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2022, 51, 107–109. 10.55230/mabjournal.v51i2.2246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C.; Zhang J.; Yu L.; Wang C.; Yang Y.; Rong X.; Xu K.; Chu M. Antifungal Activity of Coumarin against Candida Albicans Is Related to Apoptosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 8, 445. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh L. R.; Avula S. R.; Raj S.; Srivastava A.; Palnati G. R.; Tripathi C. K. M.; Pasupuleti M.; Sashidhara K. V. Coumarin-Benzimidazole Hybrids as a Potent Antimicrobial Agent: Synthesis and Biological Elevation. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 954–961. 10.1038/ja.2017.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Majedy Y. K.; Kadhum A. A. H.; Al-Amiery A. A.; Mohamad A. B. Coumarins: The Antimicrobial Agents. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2016, 8, 62–70. 10.5530/srp.2017.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Wahaibi L. H.; Abu-Melha H. M.; Ibrahim D. A. Synthesis of Novel 1,2,4-Triazolyl Coumarin Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 1–8. 10.1155/2018/5201374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur A.; Singla R.; Jaitak V. Coumarins as Anticancer Agents: A Review on Synthetic Strategies, Mechanism of Action and SAR Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 101, 476–495. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S.; Pandey A.; Manvati S. Coumarin: An Emerging Antiviral Agent. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03217 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Chen Q.; Zhang Y.; Liang C. Coumarin-Based Derivatives with Potential Anti-HIV Activity. Fitoterapia 2021, 150, 104863 10.1016/j.fitote.2021.104863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Xu J.; Liu Y.; Zeng Y.; Wu G. A Review on Anti-Tumor Mechanisms of Coumarins. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 592853 10.3389/fonc.2020.592853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostova I.; Bhatia S.; Grigorov P.; Balkansky S.; Parmar V. S.; Prasad A. K.; Saso L. Coumarins as Antioxidants. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 3929–3951. 10.2174/092986711803414395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges Bubols G.; Da Rocha Vianna D.; Medina-Remón A.; Von Poser G.; Lamuela-Raventos R. M.; Lucia Eifler-Lima V.; Garcia S. C. Send Orders of Reprints at Bspsaif@emirates.Net.Ae The Antioxidant Activity of Coumarins and Flavonoids. Rev. Med. Chem 2013, 13, 318–334. 10.2174/138955713804999775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo C. R.; Sahoo J.; Mahapatra M.; Lenka D.; Kumar Sahu P.; Dehury B.; Nath Padhy R.; Kumar Paidesetty S. Coumarin Derivatives as Promising Antibacterial Agent(S). Arab. J. Chem 2021, 14, 102922 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.102922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Yao Y.; Li L. Coumarins as Potential Antidiabetic Agents. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 1253–1264. 10.1111/jphp.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M. Y.; Jannat S.; Jung H. A.; Choi R. J.; Roy A.; Choi J. S. Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Potential of Coumarins from Angelica Decursiva and Artemisia Capillaris and Structure-Activity Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 103–111. 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah M.; Chutia K.; Dutta D.; Gogoi P. Overview of Coumarin-Fused-Coumarins: Synthesis, Photophysical Properties and Their Applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 20, 55–72. 10.1039/d1ob01876k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra P.; Kar G. K. The Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Fluorescence Study of Chromeno[4,3-b]Pyridin/Quinolin-One Derivatives, the Backbone of Natural Product Polyneomarline C Scaffolds: A Brief Review. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 2879–2934. 10.1039/D0NJ04761A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehian F.; Nadri H.; Jalili-Baleh L.; Youseftabar-Miri L.; Abbas Bukhari S. N.; Foroumadi A.; Tüylü Küçükkilinç T.; Sharifzadeh M.; Khoobi M. A Review: Biologically Active 3,4-Heterocycle-Fused Coumarins. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 212, 113034 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarenezhad E.; Farjam M.; Iraji A. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Pyrimidines-Containing Hybrids: Focusing on Pharmacological Application. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1230, 129833 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V.; Chitranshi N.; Agarwal A. K. Significance and Biological Importance of Pyrimidine in the Microbial World. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 2014, 202784 10.1155/2014/202784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadar S.; Khan T. Pyrimidine: An Elite Heterocyclic Leitmotif in Drug Discovery-synthesis and Biological Activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 1–25. 10.1111/cbdd.14001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi M.; Heravi M. M.; Mirzaei M.; Zadsirjan V.; Lotfian N.; Eshtiagh-Hosseini H. Ag3[PMo12O40]: An Efficient and Green Catalyst for the Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Pyran-Annulated Heterocycles via Multicomponent Reaction. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, e5043 10.1002/aoc.5043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti R.; Parvin T. Molecular Diversity from the L-Proline-Catalyzed, Three-Component Reactions of 4-Hydroxycoumarin, Aldehyde, and 3-Aminopyrazole or 1,3-Dimethyl-6-Aminouracil. Synth. Commun. 2015, 45, 1442–1450. 10.1080/00397911.2015.1023900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan A.; Rubab L.; Rehman M. U.; Anjum R.; Ullah S.; Marjana M.; Qadeer S.; Sana S. Coumarin Sulfonamide Derivatives: An Emerging Class of Therapeutic Agents. Heterocycl. Commun. 2020, 26, 46–59. 10.1515/hc-2020-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Zhang J.; Chen D.; Wang B.; Yang X.; Ma Y.; Szostak M. Rh(III)-Catalyzed C-H Amidation of 2-Arylindoles with Dioxazolones: A Route to Indolo[1,2-c]Quinazolines. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7038–7043. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong B. C.; Liao W. K.; Dange N. S.; Liao J. H. One-Pot Organocatalytic Enantioselective Domino Double-Michael Reaction and Pictet-Spengler-Lactamization Reaction. a Facile Entry to the “inside Yohimbane” System with Five Contiguous Stereogenic Centers. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 468–471. 10.1021/ol3032329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Wang X.; Chen D.; Kang Y.; Ma Y.; Szostak M. Synthesis of C6-Substituted Isoquinolino[1,2-b]Quinazolines via Rh(III)-Catalyzed C-H Annulation with Sulfoxonium Ylides. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 3192–3201. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b03065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giernoth R. Homogeneous Catalysis in Ionic Liquids. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 276, 1–23. 10.1007/128_016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C.; Fang D.; Liu L.; Yi T. F. Synthesis and Application of Task-Specific Ionic Liquids Used as Catalysts and/or Solvents in Organic Unit Reactions. J. Mol. Liq. 2011, 163, 99–121. 10.1016/j.molliq.2011.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty S. Homogeneous Catalysis in Ionic Liquids. RSC Catal. Ser. 2014, 2014, 44–308. [Google Scholar]

- Vekariya R. L. A Review of Ionic Liquids: Applications towards Catalytic Organic Transformations. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 227, 44–60. 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.11.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. V.; Nigam A. K.; Batra A.; Boopathi M.; Singh B.; Vijayaraghavan R. Applications of Ionic Liquids in Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors. Int. J. Electrochem. 2012, 2012, 165683 10.1155/2012/165683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A. C.; Jensen J. L.; Ntai I.; Tran K. L. T.; Weaver K. J.; Forbes D. C.; Davis J. H. Novel Brønsted Acidic Ionic Liquids and Their Use as Dual Solvent-Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 5962–5963. 10.1021/ja026290w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padvi S. A.; Dalal D. S. Task-Specific Ionic Liquids as a Green Catalysts and Solvents for Organic Synthesis. Curr. Green Chem. 2020, 7, 105–119. 10.2174/2213346107666200115153051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dömling A.; Wang W.; Wang K. Chemistry and Biology of Multicomponent Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3083–3135. 10.1021/cr100233r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hügel H. M. Microwave Multicomponent Synthesis. Molecules 2009, 14, 4936–4972. 10.3390/molecules14124936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neochoritis C. G.; Zarganes-Tzitzikas T.; Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts K.; Dömling A. Multicomponent Reactions: “Kinderleicht.”. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 3739–3745. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y. Pot Economy and One-Pot Synthesis. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 866–880. 10.1039/C5SC02913A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W.; Keh C. C. K.; Li C. J.; Varma R. S. Erratum: Water as a Reaction Medium for Clean Chemical Processes. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2004, 7, 62–69. 10.1007/s10098-004-0262-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madivalappa Davanagere P.; Maiti B. 1,3-Bis(Carboxymethyl)Imidazolium Chloride as a Sustainable, Recyclable, and Metal-Free Ionic Catalyst for the Biginelli Multicomponent Reaction in Neat Condition. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 26035–26047. 10.1021/acsomega.1c02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakara M. D.; Maiti B. Ionic Liquid-Immobilized Proline(s) Organocatalyst-Catalyzed One-Pot Multi-Component Mannich Reaction under Solvent-Free Condition. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 2381–2401. 10.1007/s11164-020-04096-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davanagere P. M.; Maiti B. Bifunctional C2-Symmetric Ionic Liquid-Supported (S)-Proline as a Recyclable Organocatalyst for Mannich Reactions in Neat Condition. Res. Chem. 2021, 3, 100152 10.1016/j.rechem.2021.100152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukku N.; Maiti B. On Water Catalyst-Free Synthesis of Benzo[: D] Imidazo[2,1- b] Thiazoles and Novel N-Alkylated 2-Aminobenzo [d] Oxazoles under Microwave Irradiation. RSC Adv. 2019, 10, 770–778. 10.1039/C9RA08929B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukku N.; Madivalappa Davanagere P.; Chanda K.; Maiti B. A Facile Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Oxazoles and Diastereoselective Oxazolines Using Aryl-Aldehydes, p-Toluenesulfonylmethyl Isocyanide under Controlled Basic Conditions. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 28239–28248. 10.1021/acsomega.0c04130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaj M.; Taherkhani M.; Kalhor M. Preparation of Some Chromeno[4,3-d]Pyrido[1,2-a]Pyrimidine Derivatives by Ultrasonic Irradiation Using NiFe2O4@SiO2grafted Di(3-Propylsulfonic Acid) Nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 10718–10724. 10.1039/D1NJ01676H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmachari G.; Karmakar I.; Nurjamal K. Ultrasound-Assisted Expedient and Green Synthesis of a New Series of Diversely Functionalized 7-Aryl/Heteroarylchromeno[4,3- d]Pyrido[1,2- a]Pyrimidin-6(7H)-Ones via One-Pot Multicomponent Reaction under Sulfamic Acid Catalysis at Ambient Conditions. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 11018–11028. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Z.; Zhao D.; Geldbach T. J.; Scopelliti R.; Dyson P. J. Brønsted Acidic Ionic Liquids and Their Zwitterions: Synthesis, Characterization and PKa Determination. Chem. – Eur. J. 2004, 10, 4886–4893. 10.1002/chem.200400145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmaja R. D.; Chanda K. A Robust and Recyclable Ionic Liquid-Supported Copper(II) Catalyst for the Synthesis of 5-Substituted-1H-Tetrazoles Using Microwave Irradiation. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 1307–1317. 10.1007/s11164-019-04035-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness D. S.; Cavell K. J. Donor-Functionalized Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes of Palladium(II): Efficient Catalysts for C-C Coupling Reactions. Organometallics 2000, 19, 741–748. 10.1021/om990776c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanta P. P.; Pati H. N.; Behera A. K. The Construction of Fluorophoric Thiazolo-[2,3-: B] Quinazolinone Derivatives: A Multicomponent Domino Synthetic Approach. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 15354–15359. 10.1039/D0RA01066A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S.; Ashok Kumar S. K. Development of Highly Potent Arene-Ru (II)-Ninhydrin Complexes for Inhibition of Cancer Cell Growth. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 508, 119641 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Parr R.G.; Weitao Y.. Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1995. [Google Scholar]; c Martin R. L. Natural transition orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4775–4777. 10.1063/1.1558471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ditchfield R.; Hehre W. J.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. 9. Extended Gaussian-type basis for molecular-orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. 10.1063/1.1674902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hehre W. J.; Ditchfield R.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. 12. Furthur extensions of Gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecualr-orbital studies of organic-molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257. 10.1063/1.1677527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; et al. Gaussian 16; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dennington R.; Keith T.A.; Millam J.M.. GaussView, version 6.1; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sieland M.; Schenker M.; Esser L.; Kirchner B.; Smarsly B. M. Ionic Liquid-Based Low-Temperature Synthesis of Crystalline Ti(OH)OF·0.66H2O: Elucidating the Molecular Reaction Steps by NMR Spectroscopy and Theoretical Studies. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 5350–5365. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.