Abstract

Starting from a dinuclear complex {Gd2(L)2(NO3)4(H2O)2}·2(CH3CN) (1) based on 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (HL), a nonanuclear cluster {Gd9(L)4(μ4-OH)2(μ3-OH)8(μ2-OCH3)4(NO3)8 (H2O)8}(OH)·2H2O (2) was obtained via modulating the amount of the ligand and base. Both of them have been structurally and magnetically characterized. Complex 1 decorates the Gd2 core bridged by double μ2-phenoxyl oxygen atoms and coordinated neutral CH3CN molecules, while 2 features the Gd9 core with a sandglass-like topology. Magnetic investigations reveal that the weaker antiferromagnetic interactions between adjacent metal ions exist in complex 2 than in 1, which is in agreement with the theoretical results. Meanwhile, the magnetocaloric effect with a maximum −ΔSm value changes from 27.32 to 40.60 J kg–1 K–1 at 2 K and 7 T.

■ Introduction

In the last 2 decades, cryogenic magnetic refrigeration based on the magnetocaloric effect (MCE) has gained much attention due to the energy efficiency, environmental friendliness, and anticipated compactness, which has potential application in replacing increasingly rare and expensive 3He as a coolant.1−3 The MCE is related to the changes of isothermal magnetic entropy (ΔSm) and adiabatic temperature (ΔTad) of the magnetic materials upon application of a magnetic field. Considering the large spin ground state (S = 7/2) of an isotropic GdIII ion and the weak magnetic couplings between GdIII ions, Gd-clusters are probably the most promising candidates to obtain larger −ΔSm as molecular magnetic coolants.4−7

Generally speaking, high magnetic density, which guarantees the large metal/ligand mass ratio, is favorable to enhance the MCE. In this sense, a successful approach that has been proposed to obtain the larger MCE is to construct GdIII ions with light and multidentate organic or inorganic ligands.8−10 Accordingly, a number of Gd-clusters and coordination polymers with various structures have been constructed and investigated, and the maximum value of −ΔSm has been continuously exceeded.11−24 Nonanuclear Ln-clusters, especially those with a sandglass topology, were attractively synthesized, but the MCE of Gd complexes was usually neglected.25−29 Admittedly, it remains a challenge for researchers to availably design and synthesize the limited high nuclearity Gd-clusters that afford interesting structural features and high MCE because of several challenges in synthesizing this type of clusters, such as the coordination modes of the ligands, anion templates, the ratio of raw materials, the pH value, solvents, as well as the temperature. Furthermore, apart from high magnetic density, the large MCE of Gd-clusters is also dependent upon weak magnetic couplings between the metal ions. This is because strong magnetic (ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic) exchanges that tend to offset the surrounding magnetic moments will fatally cut down the entropy changes.4

Based on the aforementioned considerations, we attempted to further explore the structure–activity relationship between the structural characteristic and the MCE of Gd-clusters. A simple but remarkable ligand, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (HL), was employed to assemble the corresponding clusters according to the following considerations: (1) Recently, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol that demonstrated to be a good candidate for building 4f clusters with a relatively small molecular weight, in favor of achieving high magnetic density.30−34 (2) Phenoxyl donor atoms generally preferred for providing a weak magnetic coupling pathway between LnIII ions. (3) Most of the reported structures consisting of this ligand are dinuclear configurations, and until now, the largest nuclearity was hexa-member Dy6 ring by adopting a mixed-ligand strategy.30 It is a promising strategy to construct higher nuclearity Gd-clusters with the enhanced MCE by the utilization of HL via the coordination-driven assembly. In accordance with the reported results, a dinuclear cluster {Gd2(L)2(NO3)4(H2O)2}·2(CH3CN) (1) was first constructed by the utilization of HL and Gd salt under a base condition. The dimer structure exhibits wide coordination sites of Gd ions, which supplies the possibility of introducing more coordination ligands and metal centers to construct the higher cluster structure. In consistent with our assumption, a nonanuclear cluster {Gd9(L)4(μ4-OH)2(μ3-OH)8(μ2- OCH3)4(NO3)8(H2O)8}(OH)·2H2O (2) had been fabricated by the utilization of the dimer crystal sample as starting materials. Both of these two samples had been magnetically characterized. The −ΔSmmax derived from isothermal magnetization is up to 27.32 J kg–1 K–1 for 1 and 40.60 J kg–1 K–1 for 2 at T = 2 K and ΔH = 7 T, illustrating the important role of higher cluster for improving MCE property. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the −ΔSmmax still achieves 20.4 J kg–1 K–1 for 2 at T = 2 K and ΔH = 3 T, which is close to the capacity of commercialized gadolinium gallium garnet Gd3Ga5O12 (GGG, about 24 J kg–1 K–1 with ΔH = 3 T). Herein, the synthesis, crystal structures, and magnetic properties of 1–2 are described in detail.

Experimental Procedures

Synthesis of {Gd2(L)2(NO3)4(H2O)2}·2(CH3CN) (1)

2,6-Dimethoxyphenol (0.015 g, 0.1 mmol), Gd(NO3)3·6H2O (0.090 g, 0.2 mmol), triethylamine (0.014 mL, 0.1 mmol), and 10 mL of MeOH/MeCN (v/v = 1) were added to a 50 mL round-bottomed flask, stirred for 4 h at room temperature to form a light pink solution, and then filtered, and the filtrate was left undisturbed to slowly evaporate; after about 5 days, pink block single crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction were obtained (yield 21%, based on Gd). Elemental Anal. Calcd (%): C, 24.34%; H, 2.86%; N, 8.52%. Found C, 24.39%; H, 2.82%; N, 8.67%. FTIR (KBr pellet, cm–1): 3504(br), 2947(w), 2841(w), 1628(w), 1595(w), 1506(s), 1383(s), 1304(s), 1245(m), 1189(w), 1167(w), 1097(s), 1022(s), 893(w), 856(m), 820(w), 765(w), 746(w), 713(s), 551(m), 454(m).

Synthesis of {Gd9(L)4(μ4-OH)2(μ3-OH)8(μ2-OCH3)4(NO3)8(H2O)8}(OH)·2H2O (2)

The light pink block-shaped crystals 1 (0.024 g, 0.025 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of MeOH/MeCN (v/v = 1), and then, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (0.015 g, 0.1 mmol) and triethylamine (0.014 mL, 0.1 mmol) were added. The light pink solution was kept under stirring for further 5 h and then filtered, and the filtrate was left undisturbed to slowly evaporate; after about 7 days, pink block single crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction were obtained (yield 51%, based on Gd). Elemental Anal. Calcd (%): C, 36.29%; H, 4.53%; N, 2.82%. Found: C, 36.21%; H, 4.37%; N, 2.87%. FTIR (KBr pellet, cm–1): 3441(br), 2927(w), 2847(w), 1630(w), 1558(w), 1502(vs), 1383(s), 1302(s), 1247(w), 1169(w), 1087(s), 1035(m), 1007(m), 847(s), 813(w), 763(w), 715(s), 684(w), 565(m), 461(m).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

The reaction of organic ligand and Gd salt under a base condition in the binary solvent mixture MeOH/MeCN (v/v = 1) produced the symmetric dinuclear cluster {Gd2(L)2(NO3)4(H2O)2}·2(CH3CN) (1). Taking advantage of the crystalline samples of 1 as the starting materials along with the addition of more ligand and base, a sandglass-like topology nonanuclear cluster {Gd9(L)4(μ4-OH)2(μ3-OH)8(μ2-OCH3)4(NO3)8(H2O)8}(OH)·2H2O (2) had been subsequently obtained. The structural transition could be validated by SCXRD and PXRD (see Table S1 and Figure S5 in the Supporting Information).

Crystal Structure Description

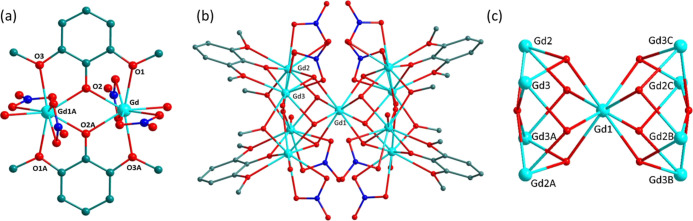

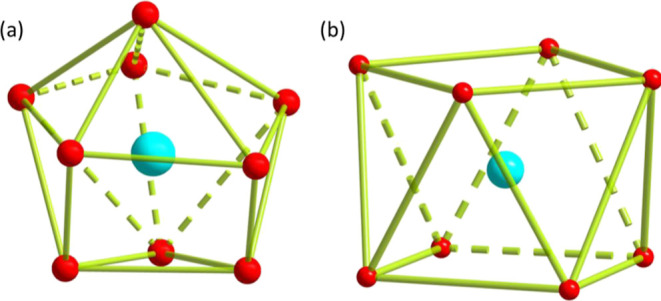

For cluster 1, the molecular structure exhibiting the symmetric dinuclear core, as shown in Figures 1a and S1 (with partial labeling), crystallizes in the triclinic space group P1̅. The asymmetric unit comprises one crystallographically independent Gd ion, one deprotonated L ligand, one coordinated water, two nitrate anions, and a free acetonitrile solvent. The central metal ions adopt nine-coordinated spheres [GdO9], which are occupied by four oxygen atoms from two deprotonated L ligands, one oxygen atom from water molecules, and two bidentate-chelating nitrate anions. The local coordination configuration of the Gd ion could be seen as spherical-capped square antiprism (C4v) that was evaluated by employing SHAPE software35,36 (Figure 2a and TableS4). The two crystallographically unique Gd ions are bonded together via two doubly bridged phenoxido atoms of L, which also adapt bidentate chelating fashion by O2–O1 and O2–O3 atoms. The intramolecular Gd···Gd distance is 3.848(8) Å along with the Gd1–O2–Gd1A angle of 113.68°, and the Gd–O bond lengths are in the normal range of 2.281(5)–2.528(5) Å. The two symmetric ligands run parallel to each other, causing the relative displacement of two Gd ions.

Figure 1.

(a) Perspective view of the dinuclear cluster 1 with partial labeling. All H atoms and lattice CH3CN molecules had been omitted for clarity. Symmetric code: A, −x + 1, −y + 1, −z + 1. (b) Perspective view of the nonanuclear cluster 2 with partial labeling. All H atoms had been omitted for clarity. (c) Representation of the core structure of 2. Symmetric code: A, −x + 1, −y + 1, −z; B, x, −y + 1, −z; C, −x + 1, y, −z.

Figure 2.

(a) Coordination geometry of GdIII ion in compound 1; (b) coordination geometry of GdIII(1) ion in compound 2. Color code: Gd, bright green; O, red.

Cluster 2 could be prepared via modulating the concentration of ligand and base amount in the solution of cluster 1. As shown in Figures 1 and S2, compound 2 features the Gd9 core with a sandglass-like topology, which crystallizes in the orthorhombic I222 space group, and the asymmetric unit consists of one deprotonated L ligand, three independent GdIII ions, two nitrate anions, two coordinated water, one methoxy group, and μ4-, μ3-hydroxyl groups. The Gd (1) ion is located in a special Wyckoff position connected by eight μ3-bridging hydroxyl groups and adapts an almost perfect square antiprism coordination geometry, which was also determined by the SHAPE software with a very small deviation value of 0.319 (Figure 2b and Table S4). Each μ3-hydroxo group connects the other two Gd ions (Gd(2) and Gd(3) ions) together, forming the nonanuclear molecular structure with the Gd···Gd distances of 3.807(8) and 3.817(8) Å. The μ4-hydroxyl or methoxy groups further inter-connect two sets of symmetric Gd(2) and Gd(3) ions to constitute the basal plane with the Gd···Gd distances of 3.605(2) and 3.521(1) Å, giving rise to a slightly distorted square antiprism geometry of Gd(1) ion. Two vertex-sharing square pyramids stack over each other with the basal planes rotated by 45°. The Gd–O bond lengths are in the range of 2.294(1)–2.654(1) Å, in agreement with the related distances of other similar Gd clusters.27−29 On comparing the structural analysis of 2 with 1, the more deprotonated bridging ligands and μ4- and μ3-hydroxyl groups introduced into the reaction system by enlarging the amount of the ligand and base could substitute for the weakly coordinated water molecule and chelating NO3– anions in compound 1, further coordinating more metal ions and generating a higher nuclearity cluster. Similar behaviors have also been discovered in the previously reported work.37

Magnetic Properties of 1–2

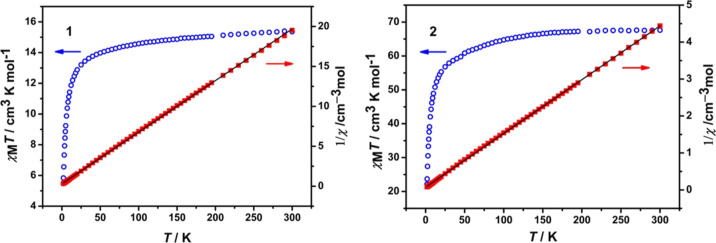

The direct-current (dc) magnetic susceptibility data for polycrystalline powders 1 and 2 were measured in the temperature range of 1.8–300 K under an applied field of 1000 Oe, as shown in Figure 3. The observed χMT product of 15.52 cm3 K mol–1 for 1 and 69.31 cm3 K mol–1 for 2 at 300 K is close to the expected values of 15.76 cm3 K mol–1 for two free GdIII ions and 70.92 cm3 K mol–1 for nine isolated GdIII ions. As temperature decreases, the χMT values gradually decrease above 50 K for both complexes and then rapidly drop to minimum values of 5.46 and 22.09 cm3 K mol–1 for 1 and 2 at 1.8 K, respectively. The decrease of the χMT value below 50 K could be attributed to the occurrence of weak antiferromagnetic exchange between the GdIII centers. Meanwhile, the χM–1 versus T plots obeying the Curie–Weiss law lead to Weiss constants of −5.44 and −4.58 K for 1 and 2, respectively. The negative Weiss parameters further prove the presence of weak antiferromagnetic interactions between the GdIII centers.

Figure 3.

Variable-temperature dc susceptibility of polycrystalline samples of 1 (left) and 2 (right) along with χM–1 vs T plots. Solid black lines represent the best fits with the Curie–Weiss law.

In order to illustrate the magnetic coupling mechanism of compounds 1 and 2, magnetic fitting was carried out following the Hamilton operators (Figure 4).38 The coupling parameter J was used to represent the magnetic exchange between adjacent GdIII ions. For 1, the magnetic propagation is dominated by two μ2-O bridges (J). However, it is impossible to perform the irreducible tensor methods owing to the great large matrix of 89 × 89 for 2. Thus, a combination of Genetic Algorithm39 with the Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) method of ALPS40 software is used to simulate magnetic parameters.41,42 Inspection of the whole structure of 2 can unveil that the magnetic property is originated from the mixed bridges (J1) of μ2-O and μ4-OH, pure bridge (J2) of μ4-OH, and the bridge (J3) of μ3-OH. The related coupling parameters could be defined based on eqs 1 and 2, respectively.

| 1 |

| 2 |

Figure 4.

(a) Variable-temperature dc susceptibility of polycrystalline samples of 1 and 2 experimentally (scatter) and theoretically (solid line); (b) sketch of 1 with Gd–Gd connection.

According to least reliability factor R (∑[(χMT)obs – (χMT)calcd]2/∑[(χMT)obs]2), the best set of optimal parameters: J = −0.26 cm–1, g = 1.95, and R = 1.17 × 10–4 for 1; J1 = 0.0108 cm–1, J2 = −0.266 cm–1, J3 = −0.146 cm–1, g = 1.95, and R = 3.83 × 10–4 for 2. It is concluded that (1) the mixed bridges (J1 = 0.0108) of μ2-O and μ4-OH indicate very weak ferromagnetic coupling, while the rest of bridges feature weak antiferromagnetic couplings; (2) generally, the antiferromagnetic property of 1 is slightly larger than that of 2. To prove the results, spin-polarized density functional theory calculation with PBE functional was carried out by using VASP program.43 To reduce the effect of self-interaction error, DFT + U with the Ueff (10.0 eV)44 is used to correct the strongly correlated interaction of 4f electrons of GdIII ions. We combined the broken-symmetry techniques of Noodleman and the non-spin projected strategy of Ruiz to estimate magnetic exchange parameters (see Supporting Information). The obtained coupling parameters are J = −0.65 cm–1 for 1 and J1 = 0.52 cm–1, J2 = −1.49 cm–1, J3 = −0.62 cm–1 for 2. Despite the values from DFT calculation are larger than those of QMC simulation because of the energy-difference overestimation of DFT methods, both of them feature the same magnetic coupling characteristics.

The field dependence of the magnetization was carried out at 1.8–15 K and 0–7 T, as shown in Figure 5. The magnetization values rise gradually accompanying the increasing fields and attain the saturated value of 12.87 Nβ and 60.77 Nβ at 7 T and 1.8 K for 1 and 2, respectively, which are slightly smaller than the theoretical ones of 14 Nβ for two non-interacting GdIII ions and 63 Nβ for nine non-interacting GdIII ions. It also indicates that the intramolecular antiferromagnetic interactions in the abovementioned compounds are very weak.

Figure 5.

Isothermal magnetization plots for 1 (left) and 2 (right). The solid lines are a guide for the eye.

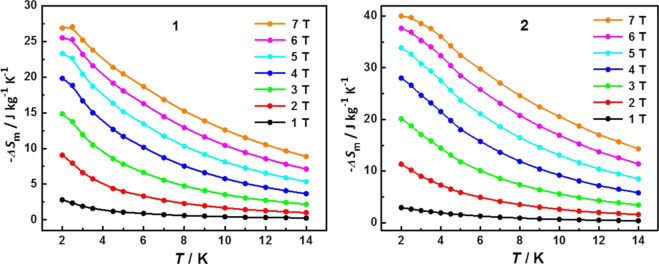

As well known, a magnetic system with larger isolated spins without zero-field spitting, spin–orbit coupling, and hyperfine interaction constantly manifests a larger MCE.45 The values of magnetic entropy change (−ΔSm) have been calculated using the Maxwell thermodynamic relation of ΔSm(ΔH) = ∫[∂M(T, H)/∂T]HdH based on the experimental magnetization data, as shown in Figure 5, where T is the applied temperature, H is the applied magnetic field, and M is magnetization. The −ΔSm values of both complexes are tardily increased along with the increasing applied magnetic field and the decreasing temperature. The maximum values of −ΔSm reach 27.32 J kg–1 K–1 for 1 and 40.60 J kg–1 K–1 for 2 at 2 K with a field change of 7 T (Figure 6). The experimental values are smaller than the corresponding calculated ones based on the equation −ΔSm = nR ln(2S + 1) (R is the gas constant and S is the spin state), which are attributable to the presence of weak antiferromagnetic interactions between spin centers. Nevertheless, the observed −ΔSm value of 2 is still comparable to those of the reported higher nuclear metal clusters due to the weaker magnetic interaction, such as Gd36 (−ΔSm = 39.66 J kg–1 K–1 withΔH = 7 T),46 Gd37 (−ΔSm = 38.7 J kg–1 K–1 withΔH = 7 T),19 and Gd38 (−ΔSm = 37.9 J kg–1 K–1 withΔH = 7 T).47 Furthermore, in terms of the lack of anisotropy and orbit contribution on GdIII ions, the interaction between GdIII ions plays a significant role in the great MCE. It is clear that the −ΔSm value of 2 is larger than that of 1 at the same temperature and applied field. Meanwhile, the absolute value of Weiss temperature of 2 is smaller than the value of 1. These indicate that the antiferromagnetic interaction in 2 is weaker, which is in good agreement with the theoretical calculation, in combination with greater magnetic density leads to the larger MCE.

Figure 6.

Temperature-dependent −ΔSm value obtained from magnetization for 1 (left) and 2 (right). The solid lines are a guide for the eye.

Conclusions

In summary, two different nuclearity Gd-clusters had been synthesized under the guidance of the specific synthesis strategy, whose crystal structures and magnetic properties had been fully characterized. Importantly, the nonanuclear cluster 2 with sandglass-like topology can be obtained via modulating the concentration of ligand and base amount in the solution of 1. Both magnetization experimental and theoretical calculations demonstrate the existence of weak antiferromagnetic interactions in adjacent GdIII ions of both 1 and 2. Due to the high spin density and the dominant weak antiferromagnetic coupling, both of them display a large MCE, with the maximum −ΔSm values of 27.32 and 40.60 J kg–1 K–1 at 2 K and 7 T, respectively. Caused by the structural conversion from 1 to 2, the presence of higher magnetic density and weaker exchange interaction contribute to a significantly increased MCE. Notably, the −ΔSmmax still achieves 20.4 J kg–1 K–1 at T = 2 K and ΔH = 3 T, making cluster 2 a promising candidate for cryo-magnetic refrigerants at low temperature and external fields. As observed in the present work, the proper modulation of the cluster structure may afford a feasible strategy for tuning the MCE of polynuclear gadolinium systems.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 92161123, 21971078, and 62001159), Open Project Fund of Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Chemical Materials and Devices of the Ministry of Education (Jianghan University) (JDGD-202019), Frontier Project of Application Foundation of Wuhan Science and Technology Bureau of China (grant no. 2020010601012201), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019kfyRCPY071 and 2019kfyKJC009), Hubei Provincial Innovative Training Program for College Students (S202010927046), and Special Fund Projects of Hubei Key Laboratory of Radiation Chemistry and Functional Materials (2021ZX07). We gratefully acknowledge the Analytical and Testing Center, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, for analysis and spectral measurements. We also thank the staffs from BL17B beamline of the National Center for Protein Sciences Shanghai (NCPSS) at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, for assistance during data collection.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c04412.

Materials and general methods; X-ray structural determination; crystal data and structure refinements; selected bond lengths and bond angles; evaluated local coordination geometry analysis; spin magnetic moment; perspective view of the asymmetric unit and ORTEP representation; FT-IR spectra; TG curves; PXRD patterns; and computational details (PDF)

Crystal structure of 1 (CIF)

Crystal structure of 2 (CIF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 1577366 and 2103547 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sharples J. W.; Collison D.; McInnes E. J. L.; Schnack J.; Palacios E.; Evangelisti M. Quantum Signatures of a Molecular Nanomagnet in Direct Magnetocaloric Measurements. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5321. 10.1038/ncomms6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J.-B.; Zhang Q.-C.; Kong X.-J.; Ren Y.-P.; Long L.-S.; Huang R.-B.; Zheng L.-S.; Zheng Z. A 48-Metal Cluster Exhibiting a Large Magnetocaloric Effect. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10649–10652. 10.1002/anie.201105147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecharsky V. K.; Gschneidner K. A. Jr. Magnetocaloric effect and Magnetic Refrigeration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999, 200, 44–56. 10.1016/s0304-8853(99)00397-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.-Z.; Zhou G.-J.; Zheng Z.; Winpenny R. E. P. Molecule-based magnetic coolers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1462–1475. 10.1039/c3cs60337g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-L.; Chen Y.-C.; Guo F.-S.; Tong M.-L. Recent advances in the design of magnetic molecules for use as cryogenic magnetic coolants. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 281, 26–49. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.-Y.; Kong X.-J.; Zheng Z.; Long L.-S.; Zheng L.-S. High-Nuclearity Lanthanide-Containing Clusters as Potential Molecular Magnetic Coolers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 517–525. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis M. S. Magnetocaloric and barocaloric effects of metal complexes for solid state cooling: review, trends and perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 417, 213357–213367. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-H.; Liu A.-J.; Ma Y.-J.; Han S.-D.; Hu J.-X.; Wang G.-M. A large magnetocaloric effect in two hybrid Gd-complexes: the synergy of inorganic and organic ligands towards excellent cryo-magnetic coolants. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 6352–6358. 10.1039/c9tc01475f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C.; Ju W.; Luo X.; Lin Q.; Cao J.; Xu Y. A series of lanthanide compounds constructed from Ln8 rings exhibiting large magnetocaloric effect and interesting luminescence. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 8608–8614. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.-F.; Liu B.-L.; Ye M.-Y.; Long L.-S.; Zheng L.-S. Magnetocaloric Effect and Thermal Conductivity of a 3D Coordination Polymer of [Gd(HCOO)(C2O4)]n. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 9259–9262. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.-F.; Liu Z.; Ren P.; Liu X.-H.; Wang N.; Cui J.-Z.; Gao H.-L. A new family of dinuclear lanthanide complexes constructed from an 8-hydroxyquinoline Schiff base and β-diketone: magnetic properties and near-infrared luminescence. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 1392–1403. 10.1039/c8dt04384a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das C.; Upadhyay A.; Ansari K. U.; Ogiwara N.; Kitao T.; Horike S.; Shanmugam M. Lanthanide-based porous coordination polymers: syntheses, slow relaxation of magnetization, and magnetocaloric effect. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 6584–6598. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Li X.-L.; Zhao L.; Guo M.; Tang J. Enhancement of magnetocaloric effect through fixation of carbon dioxide: molecular assembly from Ln4 to Ln4 cluster pairs. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 4104–4111. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary A.; Himanshu S. J.; Sajal K.; Sanjit K. Synthesis and Characterization of Two Discrete Ln10 Nanoscopic Ladder-Type Cages: Magnetic Studies Reveal a Significant Cryogenic Magnetocaloric Effect and Slow Magnetic Relaxation. Chem.—Asian J. 2014, 9, 1083–1090. 10.1002/asia.201301619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.-L.; Wang N.-N.; Wang W.-M.; Shen H.-Y.; Zhou X.-P.; Chang Y.-X.; Zhang R.-X.; Cui J.-Z. Fine-tuning the magnetocaloric effect and SMMs behaviors of coplanar RE4 complexes by β-diketonate coligands. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 860–870. 10.1039/c7qi00034k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.-M.; Zangana K. H.; Kostopoulos A. K.; Tong M.-L.; Winpenny R. E. P. A pseudo-icosahedral cage {Gd12} based on aminomethylphosphonate. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 9041–9044. 10.1039/c6dt00876c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.-R.; Zou H.-H.; Chen Z.-L.; Li B.; Wang K.; Liang F.-P. Triethylamine-templated nanocalix Ln12 clusters of diacylhydrazone: crystal structures and magnetic properties. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 17414–17421. 10.1039/c9dt03335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L.-X.; Xiong G.; Wang L.; Cheng P.; Zhao B. A 24-Gd nanocapsule with a large magnetocaloric effect. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1055–1057. 10.1039/c2cc35800j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Zheng X.-Y.; Cai J.; Hong Z.-F.; Yan Z.-H.; Kong X.-J.; Ren Y.-P.; Long L.-S.; Zheng L.-S. Three giant lanthanide clusters Ln37 (Ln= Gd, Tb, and Eu) featuring a double-cage structure. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 2037–2041. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J.; Cui P.; Shi P. F.; Cheng P.; Zhao B. Ultrastrong alkali-resisting lanthanide-zeolites assembled by [Ln60] nanocages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15988–15991. 10.1021/jacs.5b10000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L.; Zhou G.-J.; Yu Y.-Z.; Nojiri H.; Schröder C.; Winpenny R. E. P.; Zheng Y.-Z. Topological self-assembly of highly symmetric lanthanide clusters: a magnetic study of exchange-coupling “fingerprints” in giant Gadolinium (III) Cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16405–16411. 10.1021/jacs.7b09996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X.-M.; Hu Z.-B.; Lin Q.-F.; Cheng W.; Cao J.-P.; Cui C.-H.; Mei H.; Song Y.; Xu Y. Exploring the performance improvement of magnetocaloric effect based Gd-exclusive cluster Gd60. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11219–11222. 10.1021/jacs.8b07841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J.-B.; Kong X.-J.; Zhang Q.-C.; Orendáč M.; Prokleška J.; Ren Y.-P.; Long L.-S.; Zheng Z.; Zheng L.-S. Beauty, Symmetry, and Magnetocaloric Effect Four-Shell Keplerates with 104 Lanthanide Atoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17938–17941. 10.1021/ja5107749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.-Y.; Jiang Y.-H.; Zhuang G.-L.; Liu D.-P.; Liao H.-G.; Kong X.-J.; Long L.-S.; Zheng L.-S. A gigantic molecular wheel of {Gd140}: a new member of the molecular wheel family. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18178–18181. 10.1021/jacs.7b11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandropoulos D. I.; Mukherjee S.; Papatriantafyllopoulou C.; Raptopoulou C. P.; Psycharis V.; Bekiari V.; Christou G.; Stamatatos T. C. A new family of nonanuclear lanthanide clusters displaying magnetic and optical properties. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11276–11278. 10.1021/ic2013683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Xiao T.; Liu C.; Li Q.; Zhu Y.; Tang M.; Du C.; Song M. Systematic study of the luminescent europium-based nonanuclear clusters with modified 2-hydroxybenzophenone ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 13332–13340. 10.1021/ic401191e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H.-H.; Sheng L.-B.; Chen Z.-L.; Liang F.-P. Lanthanide nonanuclear clusters with sandglass-like topology and the SMM behavior of dysprosium analogue. Polyhedron 2015, 88, 110–115. 10.1016/j.poly.2014.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Qin Y.; Ge Y.; Cui Y.; Zhang X.; Li Y.; Yao J. Rationally assembled nonanuclear lanthanide clusters: Dy9 displays slow relaxation of magnetization and Tb9 serves as luminescent sensor for Fe3+, CrO42– and Cr2O72–. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 19344–19354. 10.1039/c9nj04893f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P.; Cao L.; Liu A.; Zhang Y.; Zhang T.; Li B. Modulating the relaxation dynamics via structural transition from a dinuclear dysprosium cluster to a nonanuclear cluster. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 12814–12820. 10.1039/d1dt02380b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joarder B.; Mukherjee S.; Xue S.; Tang J.; Ghosh S. K. Structures and magnetic properties of two analogous Dy6 wheels with electron-donation and -withdrawal effects. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 7554–7560. 10.1021/ic500875m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S.; Lu J.; Velmurugan G.; Singh S.; Rajaraman G.; Tang J.; Ghosh S. K. Influence of tuned linker functionality on modulation of magnetic properties and relaxation dynamics in a family of six isotypic Ln2 (Ln = Dy and Gd) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 11283–11298. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-Y.; Zhang Y.-Q.; Jiang S.-D.; Sun W.-B.; Li H.-F.; Wang B.-W.; Chen P.; Yan P.-F.; Gao S. Dramatic impact of the lattice solvent on the dynamic magnetic relaxation of dinuclear dysprosium single-molecule magnets. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 1575–1586. 10.1039/c8qi00266e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-W.; Wu Z.; Chen J.-T.; Li L.; Chen P.; Sun W.-B. Regulating the single-molecule magnetic properties of phenol oxygen-bridged binuclear lanthanide complexes through the electronic and spatial effect of the substituents. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 1229–1238. 10.1039/c9qi01380f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong M.; Feng X.; Wang J.; Zhang Y. Q.; Song Y. Tuning magnetic anisotropy via terminal ligands along the Dy···Dy orientation in novel centrosymmetric [Dy2] single molecule magnets. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 568–577. 10.1039/d0dt03854g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova D.; Llunell M.; Alemany P.; Alvarez S. The Rich Stereochemistry of Eight-Vertex Polyhedra: A Continuous Shape Measures Study. Chem.—Eur. J. 2005, 11, 1479–1494. 10.1002/chem.200400799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llunell M.; Casanova D.; Cirera J.; Alemany P.; Alvarez S.. SHAPE 2.1; University of Barcelona: Barcelona, 2013.

- Lyu D.-P.; Zheng J.-Y.; Li Q.-W.; Liu J.-L.; Chen Y.-C.; Jia J.-H.; Tong M.-L. Construction of lanthanide single-molecule magnets with the “magnetic motif” [Dy(MQ)4]−. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1776–1782. 10.1039/c7qi00393e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrás-Almenar J. J.; Clemente-Juan J. M.; Coronado E.; Tsukerblat B. S. MAGPACK 1 A package to calculate the energy levels, bulk magnetic properties, and inelastic neutron scattering spectra of high nuclearity spin clusters. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 985–991. 10.1002/jcc.1059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. H.Adaptation in Natural and Artificial System; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque A. F.; Alet F.; Corboz P.; Dayal P.; Feiguin A.; Fuchs S.; Gamper L.; Gull E.; Gürtler S.; Honecker A.; Igarashi R.; Körner M.; Kozhevnikov A.; Läuchli A.; Manmana S. R.; Matsumoto M.; McCulloch I. P.; Michel F.; Noack R. M.; Pawłowski G.; Pollet L.; Pruschke T.; Schollwöck U.; Todo S.; Trebst S.; Troyer M.; Werner P.; Wessel S. The ALPS project release 1.3: Open-source software for strongly correlated systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 310, 1187–1193. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.10.304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.-Y.; Zhang H.; Wang Z.; Liu P.; Du M.-H.; Han Y.-Z.; Wei R.-J.; Ouyang Z.-W.; Kong X.-J.; Zhuang G.-L.; Long L.-S.; Zheng L.-S. Insights into magnetic interactions in a monodisperse Gd12Fe14 metal cluster. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11475–11479. 10.1002/anie.201705697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D.; Yin L.; Hu P.; Li B.; Ouyang Z.-W.; Zhuang G.-L.; Wang Z. Series of Highly Stable Lanthanide-Organic Frameworks Constructed by a Bifunctional Linker: Synthesis, Crystal Structures, and Magnetic and Luminescence Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 2577–2583. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1996, 54, 11169. 10.1103/physrevb.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Yao K.-L.; Liu Z.-L. Ab initio study of the spin distribution and conductive properties of a Malonato-bridged gadolinium (III) complex. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2007, 76, 134409. 10.1103/physrevb.76.134409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lun H.-J.; Xu L.; Kong X.-J.; Long L.-S.; Zheng L.-S. A High-Symmetry Double-Shell Gd30Co12 Cluster Exhibiting a Large Magnetocaloric Effect. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 10079–10083. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c00993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M.; Jiang F.; Kong X.; Yuan D.; Long L.; Al-Thabaiti S. A.; Hong M. Two polymeric 36-metal pure lanthanide nanosize clusters. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3104–3109. 10.1039/c3sc50887k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F.-S.; Chen Y.-C.; Mao L.-L.; Lin W.-Q.; Leng J.-D.; Tarasenko R.; Orendáč M.; Prokleška J.; Sechovský V.; Tong M.-L. Anion-templated assembly and magnetocaloric properties of a nanoscale {Gd38} cage versus a {Gd48} barrel. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14876–14885. 10.1002/chem.201302093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.