Abstract

Background

This paper aimed to examine the effects of probiotics on eight factors in the prediabetic population by meta-analysis, namely, fasting blood glucose (FBG), glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and the mechanisms of action are summarized from the existing studies.

Methods

Seven databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, SinoMed, CNKI, and Wanfang Med) were searched until March 2022. Review Manager 5.4 was used for meta-analysis. The data were analysed using weighted mean differences (WMDs) or standardized mean differences (SMDs) under a fixed effect model to observe the efficacy of probiotic supplementation on the included indicators.

Results

Seven publications with a total of 460 patients were included. According to the meta-analysis, probiotics were able to significantly decrease the levels of HbA1c (WMD, -0.07; 95% CI -0.11, -0.03; P = 0.001), QUICKI (WMD, 0.01; 95% CI 0.00, 0.02; P = 0.04), TC (SMD, -0.28; 95% CI -0.53, -0.22; P = 0.03), TG (SMD, -0.26; 95% CI -0.52, -0.01; P = 0.04), and LDL-C (WMD, -8.94; 95% CI -14.91, -2.97; P = 0.003) compared to levels in the placebo group. The effects on FBG (WMD, -0.53; 95% CI -2.31, 1.25; P = 0.56), HOMA-IR (WMD, -0.21; 95% CI -0.45, 0.04; P = 0.10), and HDL-C (WMD, 2.05; 95% CI -0.28, 4.38; P = 0.08) were not different from those of the placebo group.

Conclusion

The present study clearly indicated that probiotics may fulfil an important role in the regulation of HbA1c, QUICKI, TC, TG and LDL-C in patients with prediabetes. In addition, based on existing studies, we concluded that probiotics may regulate blood glucose homeostasis in a variety of ways.

Trial Registration

This meta-analysis has been registered at PROSPERO with ID: CRD42022321995.

Keywords: Prediabetes, Probiotics, Random control trials, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Background

Diabetes and its complications are among the chronic noncommunicable diseases that pose a serious threat to public health [1]. Prediabetes is a period of impaired glucose regulation that includes impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance with elevated blood glucose levels [2] that do not yet meet the diagnostic criteria for diabetes [3]. The prevalence of prediabetes is increasing each year [4] and is much higher than that of type 2 diabetes [5]. According to statistics, 70% of patients with prediabetes eventually develop diabetes [3]. In the treatment of prediabetes, lifestyle improvement and drug therapy have limitations and side effects, respectively [3]. In this light, there is an urgent need for natural and safe strategies to control and delay the progression of prediabetes to diabetes [6].

However, prediabetes remains a reversible stage in clinical practice [7–9]. Recent studies have found certain mechanisms mediating the development from the prediabetic stage to diabetes. One of the important changes that occur in the process is the alteration of the gut microbiota, which affects intestinal permeability, metabolic regulation and insulin resistance [10].

Probiotics exert beneficial effects on the body by regulating the intestinal microbiota [11]. An elevated abundance of intestinal flora is associated with remission of diabetes. For example, in some studies, probiotics have been shown to improve insulin resistance, regulate blood glucose homeostasis, lower blood lipids, and delay or inhibit the onset of diabetes and its complications [12–16]. However, the mechanisms of the role of probiotics in prediabetes are not fully understood. Moreover, there are also inconsistent views on the beneficial effects of probiotics. Some studies have found that Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 have a limited effect on glucolipid metabolism in prediabetes [17, 18]. Accordingly, we performed the present meta-analysis to determine whether probiotics are beneficial in prediabetes and to discuss their mechanisms of action on the basis of existing studies.

The PICO principle was adopted in this paper, namely, participants, intervention, comparison, and outcome. The specific factors are as follows: P – people with prediabetes; I – probiotics given orally only and unlimited types and forms; C – equal doses of placebo; and O – primary indicators of fasting blood glucose (FBG) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), and secondary indicators of homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis and systematic review were performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [19].

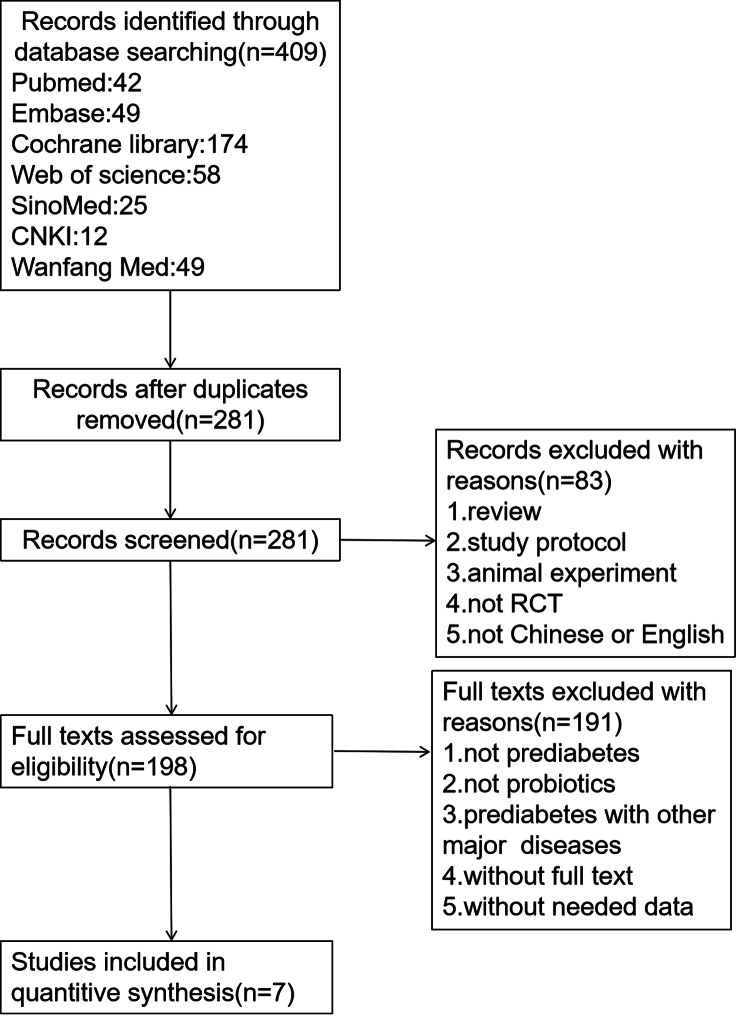

Seven databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, SinoMed, CNKI [China National Knowledge Infrastructure], and Wanfang Med) were searched from inception to March 2022. The search terms were as follows: [(probiotic agent) OR (gastrointestinal microbiota) OR (gut dysbiosis) OR (gut microbiota) OR (gut microbiome) OR (probiotics)] AND [(prediabetes) OR (prediabetic states) OR (states, prediabetic) OR (state, prediabetic) OR (impaired glucose regulation) OR (impaired glucose tolerance) OR (impaired fasting glucose) OR (impaired glucose metabolism) OR (abnormal glucose metabolism) OR (prediabetic state)] AND [(randomized controlled trial OR randomized OR placebo)]. Finally, corresponding to the database mentioned above, we retrieved n = 42, 58, 49, 174, 25, 12, 49 papers respectively, for a total of 409 articles.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

Only randomized controlled trials of probiotics for prediabetes were selected. Among them, the probiotics group only used probiotics without other drugs or treatments, and patients with prediabetes met either impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance or both and were free of other major medical conditions.

Exclusion criteria

Articles that met the following requirements were excluded: study protocols, full text not available, and not in English or Chinese. Studies that did not provide required data were also excluded. This work was performed by three researchers: two independent researchers who screened articles and a third staff member who addressed controversial issues. The study screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study screening flowchart

Data extraction

For the meta-analysis, the following information was summarized: (1) first author’s name, publication year and country; (2) probiotics or placebo group, number of people in each group, and age range; and (3) form of administration, type of probiotic, duration of intervention, and outcomes observed.

For the systematic review, the following related information on the included studies was summarized: (1) first author’s name and year of publication; (2) form of administration and dose in each group; (3) investigated factors and mechanisms; and (4) alterations in outcomes.

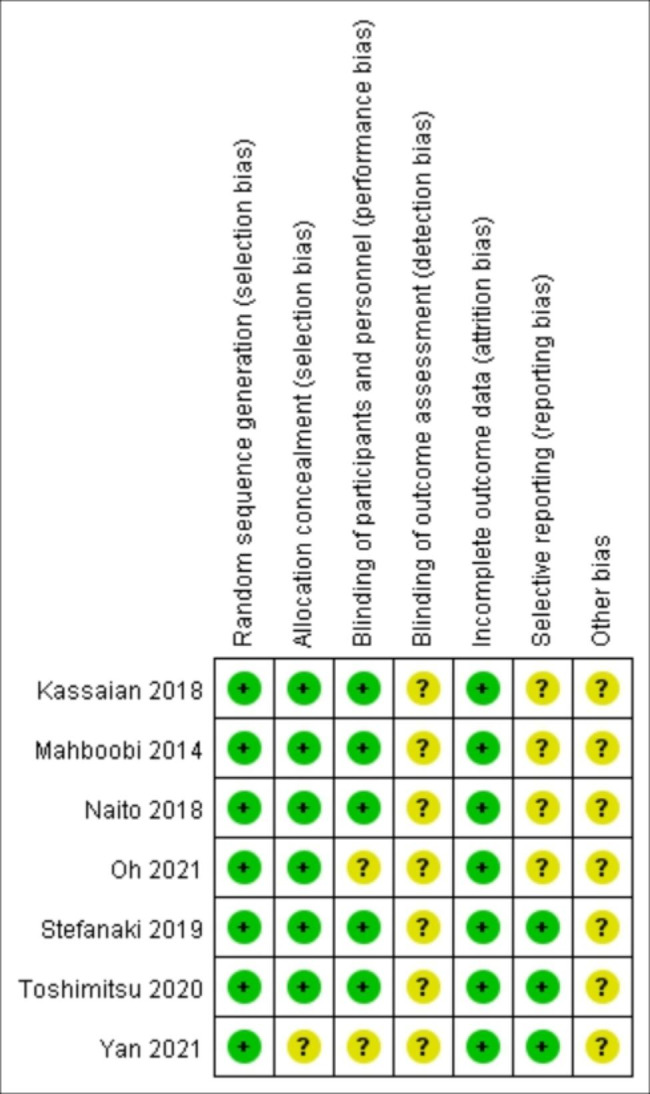

Study quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook [20]. The seven types of bias listed in the manual are selection bias, allocation concealment, implementation bias, measurement bias, follow-up bias, reporting bias, and others. The risk of bias for inclusion in the article is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary

Data analysis

This meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4. A fixed-effects model was used for the mean difference analysis of each study indicator. Standardized mean differences were chosen when the units and measurement methods of each indicator in the included studies were not consistent; conversely, weighted mean differences were chosen. For continuous variables, 95% confidence intervals were used. Mild, moderate, and severe heterogeneity was assessed based on I² and Chi² statistics of 0–25%, 25–50%, and 50–75%, respectively.

Publication bias

If the number of studies included in the meta-analysis was sufficient (n ≥ 10), then the funnel plot of fasting blood glucose was plotted in Review Manager 5.4 to observe whether it was symmetrical. If the funnel plot was not symmetrical, then publication bias was indicated, and further statistical description was performed using Egger’s test. A P value < 0.05 suggested the existence of publication bias. Next, the indicators that caused publication bias were remedied by the trim and fill method.

Results

Included studies

Seven studies with a total of 460 patients were included in this meta-analysis. Of these patients, 233 were in the probiotic group, and 227 were in the placebo group. Three studies used capsules to administer probiotics, and others provided probiotics via forms of milk, yogurt, powder and sachets. Three studies treated patients with only one probiotic, whereas the rest used combinations of three or more probiotics as interventions. Details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specific characteristics of the seven studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Sample size (experiment/control) | Age (years) | Interventions | Administration form | Probiotic strain | Duration | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahboobi et al. [5] | Iran | 56 (28/27) | 25–65 | Probiotic/Placebo | Capsule | Lacbotacillus casei; Lacbotacillus acidophilus; Lacbotacillus phamnosus, etc. |

8 weeks |

(8) |

| Kassaian et al. [21] | Iran | 85 (27/30/28) | 35–75 | Probiotic/Synbiotic/Placebo | Powder | Lactobacillus acidophilus; Bifidobacterium lactis; Bifidobacterium bifidum, etc. |

24 weeks |

(1)(2)(3)(4) |

| Naito et al. [17] | Japan | 98 (48/50) | 20–64 | Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota/Placebo | Milk | Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota | 14–15 weeks | (1)(2)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8) |

| Toshimitsu et al. [22] | Japan | 126 (62/64) | 20–64 | Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712/Placebo | Yogurt | Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712 |

12 weeks |

(1)(2)(4) |

| Yan et al. [23] | China | 72 (41/31) | 35–65 | Probiotic/Placebo | Capsule | Bifidobacterium; Lactobacillus-acidophilus; Enterococcus-faecalis |

2 years |

(1)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8) |

| Oh et al. [24] | Korea | 37 (20/17) | 19–70 | Lactobacillus plantarum HAC01/Placebo | Capsule | Lactobacillus plantarum HAC01 |

8 weeks |

(1)(2)(3)(4) |

| Stefanaki et al. [25] | Greece | 17 (7/10) | 12–20 | Probiotic/Placebo | Sachet | Streptococcus thermophilus; Bifidobacteria breve; Bifidobacteria longum, etc. |

4 months |

(1)(2)(5)(6) |

(1) = FBG; (2) = HbA1c; (3) = QUICKI; (4) = HOMA-IR; (5) = TC; (6) = TG; (7) = HDL-C; (8) = LDL-C.

Effects of probiotics on primary outcomes

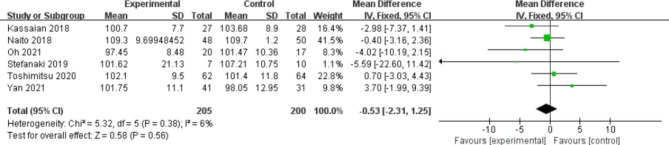

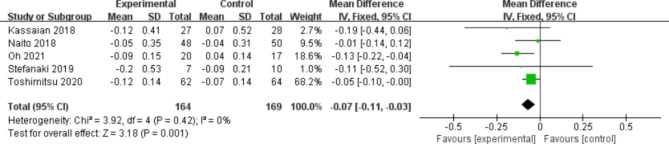

A total of 6 studies reported FBG (Fig. 3). No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups (WMD, -0.53 mg/dl; 95% CI -2.31, 1.25; P = 0.56). Slight heterogeneity was found (I2 = 6%, P = 0.38). Regarding HbA1c, five studies mentioned it (Fig. 4). The probiotic group was prominently more effective than the placebo group (MD, -0.07; 95% CI -0.11, -0.03; P = 0.001). No heterogeneity was detected between the two groups (I2 = 0%, P = 0.42).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on FBG.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on HbA1c.

Effect of probiotics on secondary outcomes

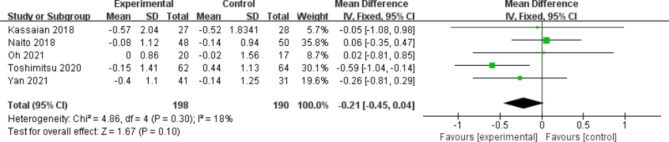

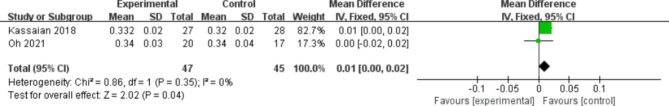

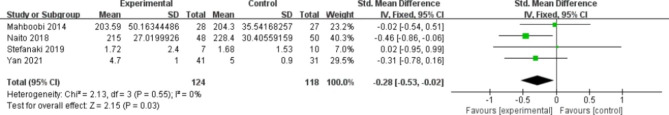

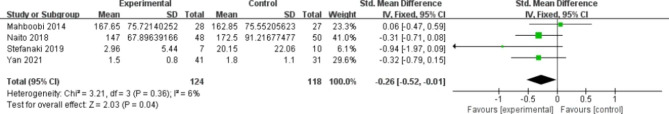

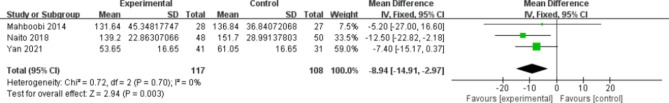

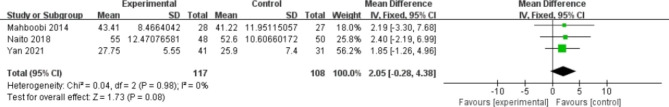

Five studies contained HOMA-IR (Fig. 5). No significant difference was found between the two groups, and there was a low level of heterogeneity (MD, -0.21; 95% CI -0.45, 0.04; P = 0.10; I2 = 18%, P = 0.30 for heterogeneity). Two studies used the QUICKI indicator (Fig. 6). The probiotic group was markedly more efficacious than the placebo group (MD, 0.01; 95% CI 0.00, 0.02; P = 0.04). No heterogeneity was observed. Four articles examined TC (Fig. 7). The probiotic group was more efficient than the placebo group (SMD, -0.28; 95% CI -0.53, -0.02; P = 0.03). No heterogeneity was observed. Four articles addressed TG (Fig. 8). A better outcome was found in the probiotic group than in the placebo group and was accompanied by subtle heterogeneity (SMD, -0.26; 95% CI -0.52, -0.01; P = 0.04; I2 = 6%, P = 0.36 for heterogeneity). Three studies involved LDL-C (Fig. 9). There was better efficacy in the probiotic group compared to the placebo group and a lack of heterogeneity (MD, -8.94; 95% CI -14.91, -2.97; P = 0.003; I2 = 0%, P = 0.70 for heterogeneity). Three studies involved HDL-C (Fig. 10). No significant differences were found between the two groups (MD, 2.05; 95% CI -0.28, 4.38; P = 0.08). There was also no heterogeneity.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on HOMA-IR.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on QUICKI.

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on TC.

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on TG.

Fig. 9.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on LDL-C.

Fig. 10.

Forest plot of the effect of probiotics on HDL-C.

Probiotic mechanisms of action and adverse reactions

In this systematic review, we observed that probiotics could play an active role in blood glucose homeostasis in the following ways. Kassaian et al. [21] found that probiotics can promote glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secretion from intestinal L cells to exert a hypoglycaemic effect. Natio et al. [17] discovered that probiotics could enhance pancreatic β-cell function when Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota-fermented milk was administered to prediabetic patients. Toshimitsu et al. [22] found that yogurt containing Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712 is able to suppress chronic inflammation and alleviate insulin resistance. Yan et al. [23] administered oral probiotics to people with abnormal glucose tolerance and found that the proportion of Lactobacillus and Eubacterium eligens in the intestine of the patients was increased, indicating that probiotics could improve intestinal flora structure to a certain degree. Stefanaki et al. [25] found that probiotics not only decrease the levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and proinflammatory cytokines to increase insulin sensitivity but also reduce the abundance of harmful flora related to insulin resistance and the inflammatory response. The adverse reactions in the probiotic group that occurred during the trial were all common minor gastrointestinal complications, such as flatulence, dyspepsia, dysphagia and constipation. Some articles mentioned that these minor adverse reactions were improved by continuing to take probiotics or reducing the daily doses. Specific information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specific characteristics of the eight studies included in the systematic review

| Study | Administration Dose | Factors | Mechanisms | Outcomes | Adverse Reactions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Placebo | Probiotics | Placebo | Investigated | Probiotics | Placebo | |||

| Mahboobi et al. [5] | Probiotic capsules | Placebo capsules | 500 mg/day | 500 mg/day | - | - | SBP↓ | - | - |

| Kassaian et al. [21] | Probiotic powder | Synbiotics powder/Placebo powder | 6 g/day | 6 g/day | GLP-1 | Promoting GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L cells; | HbA1c↓ |

2/27 Flatulence, dysphagia, and dyspepsia |

5/28 Flatulence, dysphagia, and dyspepsia |

| Naito et al. [17] |

Probiotic fermented milk |

Placebo milk | 100 ml bottle/day | 100 ml bottle/day | - | Enhancing pancreatic β-cell function | 1-h post-load PG↓; GA↓; HbA1c↓; TC↓; LDL-C↓; non-HDL-C↓ | No serious adverse effects | No serious adverse effects |

| Toshimitsu et al. [22] |

Probiotic yogurt |

Placebo yogurt | 112 g/day | 112 g/day | IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, TNF-α, hsCRP | Suppressing chronic inflammation and insulin resistance; | HbA1c↓ | No serious adverse effects | No serious adverse effects |

| Yan et al. [23] | Probiotic capsules | Placebo capsules | 2 capsules/twice daily | 2 capsules/twice daily | - | Improving intestinal flora structure | Proportion of Lactobacillus and Eubacterium eligens↑ | No adverse effects |

3/33 Headache; Diarrhoea |

| Oh et al. [24] | Probiotic capsules | Placebo capsules | 1 capsule/day | 1 capsule/day | - | - | 2 h-PPG↓; HbA1c↓ | 3/20 | 4/17 |

| Kassaian et al. [10] | Probiotic powder | Synbiotics powder/Placebo powder | 6 g/d | 6 g/d | - | - | Hyperglycaemia↓; Hypertension↓; Metabolic syndrome↓ Low HDL-C↓ |

2/27 Mild flatulence, dysphagia, and dyspepsia |

5/28 Mild flatulence, dysphagia, and dyspepsia |

| Stefanaki et al. [25] | Probiotic sachets | Life-style intervention | twice daily | twice daily | LPSs; FFAs; m-TORC; IL-17 A; Butyrate; GLUT-2 | Decreasing LPS and proinflammatory cytokines; Regulating intestinal bacteriome; Alleviating excessive FFAs | FBG↓; HbA1c↓ | Bloating, flatulence, and constipation | No adverse effects |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; non-HDL-C: non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; GA: glycoalbumin; PPG: postprandial plasma glucose; GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide 1; IL-6: interleukin-6; IL-8: interleukin-8; MCP-1: monocyte chemotactic protein 1; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor-α; hsCRP: hypersensitive C-reactive protein; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; m-TORC: mammalian target of rapamycin complex; IL-17 A: interleukin-17 A; GLUT-2: glucose transporter 2; FFA: free fatty acid

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a meta-analysis on the effects of probiotics in prediabetes and concluded that probiotics showed a statistically significant improvement in HbA1c, QUICKI, TC, TG and LDL-C in prediabetes. However, there was no distinct effect on FBG, HOMA-IR, or HDL-C. These results indicated that probiotics could improve glycolipid metabolism to some extent in prediabetes. In this light, we further systematically reviewed the mechanisms of action and side effects of probiotics in prediabetes.

Probiotics are a group of active microorganisms that primarily colonize the host’s intestinal and reproductive tracts, improve the body’s microecological balance and, when supplemented in sufficient quantities, exert beneficial effects on the enteric tract. Studies have shown that gut microecosystems are distinct between healthy individuals and diseased individuals and that dysregulation of the intestinal flora is associated with metabolic diseases such as hyperglycaemia and obesity [20, 26, 27]. More specifically, in diabetic patients, the abundance of beneficial flora such as Lactobacillus drops, whereas the abundance of certain Gram-negative bacteria rises. Some studies have also found that in the setting of dysglycaemia, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes increased, as did the abundances of Ruminococcus/Clostridium and Barnesiellaceae/E. coli/Proteobacteria [28–30]. However, the abundance of butyric acid-producing bacteria and the ratio of Bacteroides/Verrucomicrobiae decreased substantially [31]. There is a reduction in the number of Bacteroidetes in the obese population [32]. In addition to symbolic differences in bacterial populations, certain specific harmful strains of bacteria are involved in the processes that lead to altered intestinal permeability, intestinal inflammation and the pathology of insulin resistance. For example, Collinsella aerofaciens in the intestine increases intestinal permeability and is involved in proinflammatory processes through the production of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-17 A; Firmicutes increases LPS levels in the intestine and accelerates the inflammatory response; and Butyrivibrio crossotus is involved in intestinal inflammation by activating rapamycin complex signalling [25]. Hence, restoring microbial homeostasis in the human gut is of great importance to health.

In the present systematic review, we found that probiotics can restore the homeostasis of the intestinal flora and regulate blood glucose homeostasis by targeting the composition of the intestinal flora, promoting the proliferation of beneficial strains and reducing the abundance of harmful strains. For instance, the populations of Barnesiella spp. and Butyrivibrio crossotus following probiotics were observably reduced, and both were implicated in hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance [25]. Nevertheless, Lactobacillus inducing antimicrobial production was present at a much higher proportion after intake of probiotics [23]. Jia et al. [31] found that Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313.1 was able to reduce the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes and to increase the abundance of intestinal butyric acid-producing flora and the genus Akkermansia. Palacios et al. [33] also found that taking capsules with a blend of multiple probiotic strains for 12 weeks increased the abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria, including Bifidobacterium breve, Akkermansia muciniphila and Clostridium hathewayi, and increased plasma butyric acid levels. Certain probiotics can bring about a decrease in Firmicutes, which is able to produce more inflammatory molecules and exacerbate the inflammatory response, improve insulin resistance and prevent the progression of type 2 diabetes [34].

Probiotics could increase the secretion of GLP-1 in the body. GLP-1 is an endogenous intestinal hormone secreted by L cells and is critical for promoting insulin secretion through the enteroglucagon effect [35]. Concretely speaking, on the one hand, GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells in a glucose-dependent manner and inhibits glucagon secretion by activating the GLP-1 receptor on α cells. On the other hand, it could also promote the proliferation and regeneration of β cells and inhibit their apoptosis through the G protein-coupled receptor and TCF7L2/Wnt pathway [36, 37]. Probiotics promote GLP-1 secretion through the following three pathways. First, probiotics are able to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by fermenting dietary fibre from the diet, which can promote GLP-1 production [38]. Second, probiotics can also indirectly stimulate GLP-1 secretion through fermentation of indigestible polysaccharides [39]. Third, probiotics transform primary bile acids into secondary bile acids, which activate Takeda G protein receptor 5, after which they stimulate the secretion of GLP-1 [40]. In this systematic review, we observed that Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are both indirectly capable of promoting GLP-1 production [21].

Chronic low-grade inflammation is an important pathological change in the progression of diabetes [41]. Proinflammatory cytokines can induce insulin receptor substrate-1 serine phosphorylation and block the insulin signalling pathway [42]; thus, they are considered the dominant factor in the development of insulin resistance [43]. Notably, interleukin-6 secreted by T cells stimulates the production of C-reactive protein and macrophages associated with dysglycaemia [44]. Multiple articles in this systematic review have reported that probiotics can reduce inflammation levels and improve insulin sensitivity in the following ways. Probiotics directly inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines or indirectly reduce the abundance of the strains involved in proinflammatory processes, maintain the integrity of the intestinal epithelial cell wall and lower LPS levels to decrease inflammatory reactions. Specifically, Lactobacillus plantarum may increase insulin sensitivity by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α). We have found that administration of probiotics can markedly decrease the abundance of Butyrivibrio crossotus and Collinsella aerofaciens, both of which are engaged in the proinflammatory response; the former can activate mammalian target of rapamycin complex signalling to induce inflammation [45], and the latter is connected with the production of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-17 A [46]. Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus casei are able to reduce intestinal permeability and improve intestinal epithelial cell dysfunction due to glucose transporter type 2 receptor upregulation in a dysglycaemic environment [17, 40]. LPS is a constituent of the outer cell membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and stimulates the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by binding to the TLR4/CD14 complex [47, 48]. However, probiotic supplementation was observed to markedly lower the abundance of some Gram-negative bacteria in the gut, thus reducing LPS levels [31].

Probiotics can regulate lipid metabolism to improve blood glucose homeostasis. This imbalance may result from prolonged disturbances in blood glucose metabolism leading to more low-density lipoprotein or very-low-density lipoprotein produced by excess glycogen in the liver to bring about dyslipidaemia [5]. Consequently, we considered relevant lipid indicators as secondary outcome indicators in this meta-analysis. Probiotic supplementation substantially reduced TC, TG, and LDL-C levels. By reviewing the available reports, probiotics have been shown to promote lipid metabolism generally through the following ways, among other mechanisms. One is through the enzymatic action of bile salt hydrolase of probiotics. After hydrolysis, free bile acids cannot be reabsorbed and are excreted in the faeces, thus reducing bile sterols [22]. Second, probiotics remove cholesterol by combining with it in the small intestine [49]. Third, probiotics can also incorporate cholesterol into their cell membranes to lower blood cholesterol levels [50]. Fourth, probiotics reduce cholesterol absorption by converting cholesterol into faecal sterols via cholesterol reductase, which can be excreted in the faeces [51]. Last, probiotics inhibit the resynthesis of cholesterol through their production of short-chain fatty acids [17]. The above mechanisms of the cholesterol-lowering action of probiotics have also been validated in in vitro experiments. In this systematic review, we noted that supplementation with Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota-fermented milk markedly reduced TC and LDL-C levels [17]. Apart from that, Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus bacteria have also been identified as having the ability to lower cholesterol levels [52].

In addition, several other mechanisms, such as strengthening the mucus barrier, relieving oxidative stress, increasing leptin levels and maintaining mitochondrial health have also been implicated. The mucus layer on the surface of the intestinal epithelium is composed of mucin and mucopolysaccharides, which form the first line of defence against bacterial invasion. Certain species of probiotics could reinforce the mucus barrier by increasing the expression of mucin genes and stimulating mucus secretion [53]. For instance, Lactobacillus spp. can stimulate MUC3 expression and MUC2 production and secretion [54, 55]. Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus reuteri could increase mucus layer thickness [56, 57]. Pediococcus acidilactici pA1c increases the number of cupped cells, which promote the secretion of mucus glycoproteins and maintain an appropriate length of intestinal villi [58]. Oxidative stress may play a role in damaging glucose metabolism by impairing pancreatic β cells and insulin signalling pathways. Probiotics are known to alleviate oxidative stress. First, probiotics breakdown the superoxide produced by reactive oxygen species through their own antioxidant enzymes, e.g., superoxide dismutase [59]. Second, probiotics and some of their metabolites (glutathione, butyrate, and folate) can increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes [16, 60, 61]. Third, probiotics also act on signalling pathways (Nrf2-Keap1-ARE, NF-κB, etc.) [62–65]. Finally, probiotics can reduce the activity of enzymes related to reactive oxygen species (e.g., cytochrome P450 enzymes and NADPH oxidase) [66]. Leptin is a protein-like hormone secreted by adipose tissue. It is worth mentioning that leptin may act in both directions with insulin, which promotes the secretion of leptin; in contrast, leptin exerts a negative feedback regulation on the synthesis and secretion of insulin. Leptin can also promote the secretion of GLP-1 by activating leptin receptors. Leptin synthesized by gastric chief cells indirectly regulates the early secretion of GLP-1 through gastrin-releasing peptide [66]. Darby et al. [67] observed that supplementation with oral Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG induced elevated leptin levels dependent on functional Nox1 protein in the intestine. In animal experiments, it was found that Lactobacillus upregulated several classes of genes related to mitochondrial function in the mouse liver. In addition, Lactobacillus also improves the damage to mitochondrial morphological structure caused by hyperglycemia [68]. The improvement of mitochondrial health restores the β-oxidation of fatty acids, thus reducing the accumulation of fatty acids in the liver and improving glucose metabolism throughout the body [69, 70].

Probiotics also seem to be effective in children with obesity and T2DM. For obese children, probiotics may work by promoting lipid metabolism, increasing GLP-1 secretion, raising leptin levels and regulating intestinal flora homeostasis. Firstly, several studies have shown that GLP-1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide) could be effective for weight loss in pediatric patients [71, 72]. In our systematic review, probiotics were found to increase GLP-1 secretion in vivo, which is essential for promoting insulin secretion through the action of intestinal proinsulin. This may suggest that probiotics could treat obese children by increasing GLP-1 secretion in vivo. Secondly, in the development of childhood obesity, leptin acts on the hypothalamus and exerts anorexic effects to reduce weight [73]. Probiotics can also treat childhood obesity by increasing leptin levels and suppressing energy intake. Thirdly, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is also associated with the pathophysiology of obese children [74, 75]. New evidence suggests that an increase in the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes leads to an increase in energy extraction from the diet, triggering obesity [76]. In our systematic review, probiotics were found to reshape intestinal flora homeostasis to improve the digestion and absorption of nutrients in the intestine. Specially, Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313.1 was able to reduce the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes. This suggests that probiotics can play a beneficial role in obese children by regulating the homeostasis of the intestinal flora. In fact, several clinical studies did prove the effectiveness of probiotics treatment in obese children [77–79]. In children with T2DM, childhood T2DM begins with reduced insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and liver [80, 81], and obesity is a major risk factor for reduced insulin sensitivity in children [82, 83]. In turn, weight loss can improve insulin sensitivity in pediatric T2DM. In a randomized controlled trial, an 8% reduction in BMI was associated with improved insulin sensitivity in obese adolescents [84]. In addition, pediatric T2DM exhibited faster islet β-cell decline and higher rates of treatment failure compared to adult T2DM [85], and supplementation with Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota fermented milk was found to enhance islet β-cell function in the present study.

It is also worth stating that other toxicological effects of probiotics have been found in previous studies [86, 87]. Yeast fungemia is regarded as the most serious infectious complication caused by probiotics [88, 89]. In addition, some strains of Lactobacillus and Enterococcus could convert tyrosine and histidine into biogenic amines, which may lead to nausea, vomiting, fever and other food poisoning symptoms when in excessive amounts. Lactobacillus could also transfer drug-resistant genes to pathogenic bacteria via splice plasmids or transposons, triggering genetic mutations and causing disease [90]. Moreover, probiotics are not intended for everyone and should be used with caution in people who are immunocompromised, in serious medical conditions, with low intestinal barrier function, or people using central venous catheters [91].

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis investigating the effect of probiotics in prediabetes patients. Probiotics were found to regulate glucolipid metabolism and improve prediabetes status through multiple mechanisms of action in this study. This study provides valuable references for subsequent related studies and future clinical translation. However, there are a few important limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the number of included studies and the number of involved cases were restricted, and the types, amounts, and dosage forms of probiotics were different among the studies, so the conclusions could be affected to some extent in this study. Second, some of the included studies lacked statistical analysis of daily diet and exercise, and the results were somewhat biased. Third, we have limited information on the quantitative-effective relationship and minimum effective dose of known beneficial probiotic strains.

Further experimental studies are needed to explore more other beneficial probiotic strains in humans and their quantitative-effect relationships to better define their role in prediabetes. Second, large-scale and strictly controlled long-term observational clinical trials should be conducted to provide more reliable data on the efficacy and safety of probiotics, and the observation period of glucolipid metabolism in prediabetic patients after discontinuation of probiotics should be extended to determine whether the efficacy of probiotics persists for a long enough period of time. Finally, some basic experiments are needed to elucidate more clearly the mechanism of probiotic action on prediabetes at the molecular level.

Conclusion

This paper has shown that probiotics could significantly reduce HbA1c, QUICKI, TC, TG and LDL-C in patients with prediabetes. We found that probiotics have multiple mechanisms of action in regulating blood glucose homeostasis in this systematic review. Probiotics are able to adjust the flora structure, promote GLP-1 secretion, reduce inflammation levels, regulate lipid metabolism, and some other mechanisms, including enhancing the mucus barrier, alleviating oxidative stress, elevating leptin levels and maintaining mitochondrial health to delay or block the progression of prediabetes to diabetes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

List of abbreviations

- FBG

fasting blood glucose

- HbA1c

glycated haemoglobin A1c

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- QUICKI

quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- WMD

weighted mean difference

- SMD

standardized mean difference

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- SCFAs

short-chain fatty acids

Authors’ contributions

YL conceived the theme of the study. YL, LW and LQ conducted the literature search and data extraction and evaluated the risk of bias included in the literature. YW and YL analysed the data. YL wrote the original manuscript. YW and TH checked and modified the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the current manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Key Laboratory of TCM Health Cultivation of Beijing, Beijing International Science and Technology Cooperation Base. Grant Number: No BZ0259.

Data availability

The original data involved in the manuscript can be obtained from references.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish the manuscript. What we have done is not involved in previous studies. This manuscript will not be published elsewhere.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li XX, Bian SS, Guo Q. Research progress in the management model of prediabetes population. Chin Gen Med. 2021;24:3258–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Expert consensus on prediabetes intervention in Chinese adults. Chin J Endocrinol Metab. 2020;5:371–80. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahboobi S, Iraj B, Maghsoudi Z, Feizi A, Ghiasvand R, Askari G, et al. The effects of probiotic supplementation on markers of blood lipids, and blood pressure in patients with prediabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:1239–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis SJ, Burmeister S. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus on plasma lipids. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:776–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinese Medical Association Diabetes Branch . Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. Beijing: Peking University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KG. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabet Med. 2002;19:708–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, Ilanne-Parikka P, Aunola S, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, et al. Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) Diabetologia. 2013;56:284–93. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassaian N, Feizi A, Rostami S, Aminorroaya A, Yaran M, Amini M. The effects of 6 mo of supplementation with probiotics and synbiotics on gut microbiota in the adults with prediabetes: a double blind randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2020;79–80:110854. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Sánchez B, Delgado S, Blanco-Míguez A, Lourenço A, Gueimonde M, Margolles A. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201600240. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Yun SI, Park HO, Kang JH. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on blood glucose levels and body weight in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1681–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yadav H, Jain S, Sinha PR. Antidiabetic effect of probiotic dahi containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei in high fructose fed rats. Nutrition. 2007;23:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadav H, Jain S, Sinha PR. Oral administration of dahi containing probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei delayed the progression of streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. J Dairy Res. 2008;75:189–95. doi: 10.1017/S0022029908003129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson U, Bränning C, Ahrné S, Molin G, Alenfall J, Onning G, et al. Probiotics lower plasma glucose in the high-fat fed C57BL/6J mouse. Benef Microbes. 2010;1:189–96. doi: 10.3920/BM2009.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ejtahed HS, Mohtadi-Nia J, Homayouni-Rad A, Niafar M, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Mofid V. Probiotic yogurt improves antioxidant status in type 2 diabetic patients. Nutrition. 2012;28:539–43. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naito E, Yoshida Y, Kunihiro S, Makino K, Kasahara K, Kounoshi Y, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota-fermented milk on metabolic abnormalities in obese prediabetic Japanese men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2018;37:9–18. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.17-012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barthow C, Hood F, Crane J, Huthwaite M, Weatherall M, Parry-Strong A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a probiotic and a prebiotic examining metabolic and mental health outcomes in adults with pre-diabetes. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e055214. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassaian N, Feizi A, Aminorroaya A, Jafari P, Ebrahimi MT, Amini M. The effects of probiotics and synbiotic supplementation on glucose and insulin metabolism in adults with prediabetes: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55:1019–28. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-1175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toshimitsu T, Gotou A, Furuichi K, Hachimura S, Asami Y. Effects of 12-wk Lactobacillus plantarum OLL2712 treatment on glucose metabolism and chronic inflammation in prediabetic individuals: a single-arm pilot study. Nutrition. 2019;58:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Q, Li X, Li P, Feng B. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study of probiotic intervention in the conversion of abnormal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Shanghai Med. 2021;44:726–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh MR, Jang HY, Lee SY, Jung SJ, Chae SW, Lee SO, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum HAC01 supplementation improves glycemic control in prediabetic subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 2021;13:2337. doi: 10.3390/nu13072337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stefanaki C, Michos A, Mastorakos G, Mantzou A, Landis G, Zosi P, et al. Probiotics in adolescent prediabetes: a pilot RCT on glycemic control and intestinal bacteriome. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1743. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Roy T, Llopis M, Lepage P, Bruneau A, Rabot S, Bevilacqua C, et al. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut. 2013;62:1787–94. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mouzaki M, Comelli EM, Arendt BM, Bonengel J, Fung SK, Fischer SE, et al. Intestinal microbiota in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;58:120–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.26319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zangara MT, McDonald C. How diet and the microbiome shape health or contribute to disease: a mini-review of current models and clinical studies. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019;244:484–93. doi: 10.1177/1535370219826070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu W-K, Panyod S, Ho C-T, Kuo C-H, Wu M-S, Sheen L-Y. Dietary allicin reduces transformation of L-carnitine to TMAO through impact on gut microbiota. J Funct Foods. 2015;15:408–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Shen D, Fang Z, Jie Z, Qiu X, Zhang C, et al. Human gut microbiota changes reveal the progression of glucose intolerance. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia L, Li D, Feng N, Shamoon M, Sun Z, Ding L, et al. Anti-diabetic effects of Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313.1 through promoting the growth of gut butyrate-producing bacteria in type 2 diabetic mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7046. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–3. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palacios T, Vitetta L, Coulson S, Madigan CD, Lam YY, Manuel R, et al. Targeting the intestinal microbiota to prevent type 2 diabetes and enhance the effect of metformin on glycaemia: a randomised controlled pilot study. Nutrients. 2020;12:2041. doi: 10.3390/nu12072041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Begley M, Hill C, Gahan CG. Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1729–38. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1729-1738.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Dilidaxi D, Wu Y, Sailike J, Sun X, Nabi XH. Composite probiotics alleviate type 2 diabetes by regulating intestinal microbiota and inducing GLP-1 secretion in db/db mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;125:109914. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z, Stanojevic V, Brindamour LJ, Habener JF. GLP1-derived nonapeptide GLP1(28–36)amide protects pancreatic β-cells from glucolipotoxicity. J Endocrinol. 2012;213:143–54. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boutant M, Ramos OH, Tourrel-Cuzin C, Movassat J, Ilias A, Vallois D, et al. COUP-TFII controls mouse pancreatic β-cell mass through GLP-1-β-catenin signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burcelin R, Serino M, Chabo C, Blasco-Baque V, Amar J. Gut microbiota and diabetes: from pathogenesis to therapeutic perspective. Acta Diabetol. 2011;48:257–73. doi: 10.1007/s00592-011-0333-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okeke F, Roland BC, Mullin GE. The role of the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis and treatment of obesity. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014;3:44–57. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2014.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shapiro H, Kolodziejczyk AA, Halstuch D, Elinav E. Bile acids in glucose metabolism in health and disease. J Exp Med. 2018;215:383–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winer S, Chan Y, Paltser G, Truong D, Tsui H, Bahrami J, et al. Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2009;15:921–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. Islet-associated macrophages in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1686–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu R, Kim CS, Kang JH. Inflammatory components of adipose tissue as target for treatment of metabolic syndrome. Forum Nutr. 2009;61:95–103. doi: 10.1159/000212742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torres S, Fabersani E, Marquez A, Gauffin-Cano P. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic syndrome. The proactive role of probiotics. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:27–43. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Hou Q, Zhang J, Xu H, Sun Z, Menghe B, et al. Carbohydrate staple food modulates gut microbiota of mongolians in China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:484. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen J, Wright K, Davis JM, Jeraldo P, Marietta EV, Murray J, et al. An expansion of rare lineage intestinal microbes characterizes rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 2016;8:43. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–72. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allin KH, Nielsen T, Pedersen O. Mechanisms in endocrinology: gut microbiota in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:R167-77. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aitken JD, Gewirtz AT. Gut microbiota in 2012: toward understanding and manipulating the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:72–4. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taghizadeh M, Asemi Z. Effects of synbiotic food consumption on glycemic status and serum hs-CRP in pregnant women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Horm (Athens) 2014;13:398–406. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lye HS, Rusul G, Liong MT. Removal of cholesterol by lactobacilli via incorporation and conversion to coprostanol. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:1383–92. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ooi LG, Liong MT. Cholesterol-lowering effects of probiotics and prebiotics: a review of in vivo and in vitro findings. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:2499–522. doi: 10.3390/ijms11062499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paone P, Cani PD. Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut. 2020;69:2232–43. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bron PA, Kleerebezem M, Brummer RJ, Cani PD, Mercenier A, MacDonald TT, et al. Can probiotics modulate human disease by impacting intestinal barrier function? Br J Nutr. 2017;117:93–107. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516004037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sicard JF, Le Bihan G, Vogeleer P, Jacques M, Harel J. Interactions of intestinal bacteria with components of the intestinal mucus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:387. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahl D, Liu H, Schreiber O, Roos S, Phillipson M, Holm L. Lactobacillus reuteri increases mucus thickness and ameliorates dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2016;217:300–10. doi: 10.1111/apha.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, Kim MS, Whon TW, Lee MS, et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut. 2014;63:727–35. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cabello-Olmo M, Oneca M, Pajares MJ, Jiménez M, Ayo J, Encío IJ, et al. Antidiabetic effects of Pediococcus acidilactici pA1c on HFD-induced mice. Nutrients. 2022;14:692. doi: 10.3390/nu14030692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gutteridge JM, Richmond R, Halliwell B. Inhibition of the iron-catalysed formation of hydroxyl radicals from superoxide and of lipid peroxidation by desferrioxamine. Biochem J. 1979;184:469–72. doi: 10.1042/bj1840469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Landis GN, Tower J. Superoxide dismutase evolution and life span regulation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:365–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pompei A, Cordisco L, Amaretti A, Zanoni S, Matteuzzi D, Rossi M. Folate production by bifidobacteria as a potential probiotic property. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:179–85. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01763-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hensley K, Robinson KA, Gabbita SP, Salsman S, Floyd RA. Reactive oxygen species, cell signaling, and cell injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1456–62. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kobayashi M, Li L, Iwamoto N, Nakajima-Takagi Y, Kaneko H, Nakayama Y, et al. The antioxidant defense system Keap1-Nrf2 comprises a multiple sensing mechanism for responding to a wide range of chemical compounds. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:493–502. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01080-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seth A, Yan F, Polk DB, Rao RK. Probiotics ameliorate the hydrogen peroxide-induced epithelial barrier disruption by a PKC- and MAP kinase-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1060-9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00202.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blumberg PM. Complexities of the protein kinase C pathway. Mol Carcinog. 1991;4:339–44. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940040502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anini Y, Brubaker PL. Role of leptin in the regulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Diabetes. 2003;52:252–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Darby TM, Naudin CR, Luo L, Jones RM. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-induced expression of leptin in the intestine orchestrates epithelial cell proliferation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;9:627–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodrigues RR, Gurung M, Li Z, García-Jaramillo M, Greer R, Gaulke C, Bauchinger F, You H, Pederson JW, Vasquez-Perez S, White KD, Frink B, Philmus B, Jump DB, Trinchieri G, Berry D, Sharpton TJ, Dzutsev A, Morgun A, Shulzhenko N. Transkingdom interactions between Lactobacilli and hepatic mitochondria attenuate western diet-induced diabetes. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan 4;12(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Orellana-Gavalda JM, et al. Molecular therapy for obesity and diabetes based on a long-term increase in hepatic fatty-acid oxidation. Hepatology. 2011;53:821–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.24140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perry RJ, Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2014;510:84–91. doi: 10.1038/nature13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kansra AR, Lakkunarajah S, Jay MS. Childhood and Adolescent Obesity: A Review. Front Pediatr. 2021;12:581461. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.581461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singhal S, Kumar S. Current Perspectives on Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Youth. Children (Basel). 2021 Jan 10;8(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Front Pediatr. 2021 Jan 12;8:581461. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.581461. PMID: 33511092; PMCID: PMC7835259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Dao MC, Clément K. Gut microbiota and obesity: Concepts relevant to clinical care. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;48:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim KN, Yao Y, Ju SY. Short Chain Fatty Acids and Fecal Microbiota Abundance in Humans with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2019;18(10):2512. doi: 10.3390/nu11102512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riva A, Borgo F, Lassandro C, Verduci E, Morace G, Borghi E, Berry D. Pediatric obesity is associated with an altered gut microbiota and discordant shifts in Firmicutes populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Jan;19(1):95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Alisi A, Bedogni G, Baviera G, Giorgio V, Porro E, Paris C, Giammaria P, Reali L, Anania F. Nobili, V. Randomised clinical trial: The beneficial effects of VSL#3 in obese children with non-alcoholicsteatohepatitis.Aliment. Pharm Ther. 2014;39:1276–85. doi: 10.1111/apt.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Famouri F, Shariat Z, Hashemipour M, Keikha M, Kelishadi R. Effects of probiotics on nonalcoholic fattyliver disease in obese children and adolescents.J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:413–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanchis-Chordà J, del Pulgar EMG, Carrasco-Luna J, Benítez-Páez A, Sanz Y. Codoñer-Franch, P.Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum CECT 7765 supplementation improves inflammatory status ininsulin-resistant obese children.Eur. J. Nutr.2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Arslanian S, Bacha F, Grey M, Marcus MD, White NH, Zeitler P. Evaluation and management of youth-onset type 2 diabetes: A position statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(12):2648–68. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nolan CJ, Damm P, Prentki M. Type 2 diabetes across generations: From pathophysiology to prevention and management. Lancet. 2011;378(9786):169–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Editor. Riddle MC. American Diabetes Association: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S1–S193.

- 83.Levy-Marchal C, Arslanian S, Cutfield W, Sinaiko A, Druet C, Marcovecchio ML, et al. Insulin resistance in children: consensus, per-spective, and future directions. J Clin Endo-crinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5189–98. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abrams P, Levitt Katz LE, Moore RH, et al. Threshold for improvement in insulin sensitivity with adolescent weight loss. J Pediatr. 2013;163(3):785–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Savic Hitt TA, Katz LEL. Pediatric Type 2 Diabetes: Not a Mini Version of Adult Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2020;49(4):679–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharma P, Tomar SK, Goswami P, Sangwan V, Singh R. Antibiotic resistance among commerciallyavailable probiotics. Food Res Int. 2014;57:176–95. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang ZY, Liu C, Guo XK. Safety of probiotics[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2008(02):257–261.

- 88.Sharifi-Rad J, Rodrigues CF, Stojanović-Radić Z, Dimitrijević M, Aleksić A, Neffe-Skocińska K, Zielińska D, Kołożyn-Krajewska D, Salehi B, Milton Prabu S, Schutz F, Docea AO, Martins N, Calina D. Probiotics: Versatile Bioactive Components in Promoting Human Health. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Aug 27;56(9):433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Whelan K, Myers CE. Safety of probiotics in patients receiving nutritional support: A systematic review ofcase reports, randomized controlled trials, and nonrandomized trials.Am. J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:687–703. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guo TC. Prospects of probiotics in biomedical applications[J]. Food Safety Guide,2017, (03):76.

- 91.Sanders ME, Akkermans LM, Haller D, Hammerman C, Heimbach JT, Hörmannsperger G, Huys G. Safety assessment of probiotics for human use. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:164–85. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data involved in the manuscript can be obtained from references.