Abstract

The sudden outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought to the fore the existing threat of disease-causing pathogens that affect public health all over the world. It has left the best healthcare systems struggling to contain the spread of disease and its consequences. Under challenging circumstances, several innovative technologies have emerged that facilitated quicker diagnosis and treatment. Nanodiagnostic devices are biosensing platforms developed using nanomaterials such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, nanowires, etc. These devices have the edge over conventional techniques such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) because of their ease of use, quicker analysis, possible miniaturization, and scope for use in point-of-care (POC) treatment. This review discusses the techniques currently used for COVID-19 diagnosis, emphasizing nanotechnology-based diagnostic devices. The commercialized nanodiagnostic devices in various research and development stages are also reviewed. The advantages of nanodiagnostic devices over other techniques are discussed, along with their limitations. Additionally, the important implications of the utility of nanodiagnostic devices in COVID-19, their prospects for future development for use in clinical and POC settings, and personalized healthcare are also discussed.

Keywords: Nanodiagnostics, COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2, POC devices, Nanoparticles, Nanobiosensors

1. Introduction

1.1. COVID-19 pandemic

In late December 2019, a few cases of pneumonia outbreak were reported later linked to a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) (N. Zhu et al., 2020). The virus was isolated, and its genetic sequence was determined, which was found to be related to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus. The pneumonia cases traced were linked to a Wuhan seafood market, raising doubts about the human-to-human transmission (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). In mid-January 2020, the first imported coronavirus case was reported from Thailand, and from there, the disease spread steadily all around the globe. A public health emergency was declared on January 30th, 2020, by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The novel coronavirus was later named SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (“Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it,” n.d.). In March 2020, WHO announced the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic (WHO, 2020).

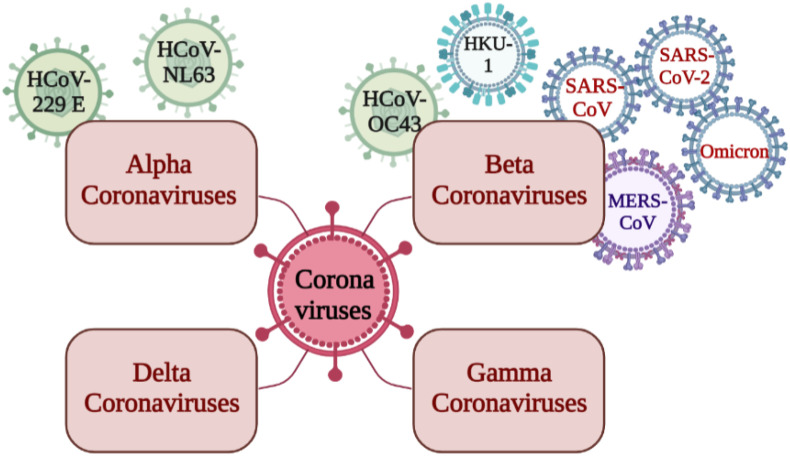

According to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, the members of Coronaviruses belong to the family Coronaviridae (order Nidovirales), which has two subfamilies, Coronavirinae and Torovirinae (“Coronaviridae - Positive Sense RNA Viruses - Positive Sense RNA Viruses (2011) - ICTV,” n.d.). The member viruses of the subfamily Coronavirinae are further classified into four genera: a) Alphacoronaviruses, b) Beta coronaviruses, c) Gamma coronaviruses, and d) Delta coronaviruses. Alphacoronaviruses (HCoV-229 E and HCoV-NL63) and Beta coronaviruses (HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and omicron) can infect humans. Fig. 1 depicts the different types of human coronaviruses. From December 2019 to mid-February 2020, 104 strains were sequenced by Illumina and Oxford nanopore sequencing methods with 99.9% sequence homology. It is reported that the homology in the sequence has been decreasing, indicating virus diversification (Udugama et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the different types of human coronaviruses (Created using biorender.com).

The genetic material of the enveloped SARS-CoV-2 virus is a positive-sense single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA). The initial genetic sequence of the virus was determined using high-throughput RNA sequencing and subsequently made public to facilitate the development of diagnostic kits. Genomic sequencing established that the virus belonged to the genus Beta coronavirus and subgenus Sarbecovirus (Wu et al., 2020). The viral genome codes for polyproteins pp1a and pp1b that gives rise to non-structural proteins by protease action and four structural proteins – the nucleocapsid (N), membrane (M), envelope (E), and spike (S) proteins (Cui et al., 2019; Perlman and Netland, 2009). The spike protein is trimeric, with two subunits, S1 and S2, in each monomer. The S1 subunit contains the receptor-binding domain (RBD), while the S2 subunit consists of two heptad repeat regions and a fusion peptide (Song et al., 2018). Studies also confirmed that the entry of the virus into the host cell occurs when the RBD of the S1 subunit binds the angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) receptor of the host cell, while the S2 subunit is responsible for cell fusion (Letko et al., 2020; Song et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020). The S2 subunit is highly conserved, while the RBD region is mostly species-specific. The RBD of SARS-CoV-2 has a greater affinity for the ACE2 receptor than the 2003 SARS-CoV (Wrapp et al., 2020). ACE2 receptor is present in arterial and venous endothelial cells, arterial smooth muscle cells in almost all organs, and expressed in epithelial cells of the lung alveoli and enterocytes of the small intestine where the site of infection is high (Udugama et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 symptoms include fever, cough, malaise, and dyspnoea. Profound implications include respiratory distress or septic shock, necessitating intensive care and often leading to morbidity. The elderly and immune-compromised individuals are more prone to developing severe implications. COVID-19 is transmitted by close contact with an infected individual through saliva, respiratory secretions, or airborne particles. Surface-to-human transmission and other indirect ways of spreading are less common. Numerous COVID-19 diagnostic techniques were evolved based on identifying either viral nucleic acid or protein biomarkers. RT-PCR is considered a gold-standard technique for its accuracy and sensitivity. RT-PCR is a sequence-specific method that helps differentiate among COVID-19 variants. Smartphone-based diagnostic devices were also developed using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein (CRISPR-Cas), colorimetric, and electrochemical techniques. Artificial intelligence-based techniques have also been reported recently for the identification of COVID-19.

1.2. COVID-19 variants

WHO classified COVID-19 variants as Variants of Concern (VOCs), Variants of Interest (VOIs), and Variants under Monitoring (VUMs) to help global monitoring and research. SARS-CoV-2 variants with increased transmissibility and increased virulence were considered VOCs. The Delta and Omicron variants with BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, BA.5, and BA.1/BA.2 lineages are the currently circulating VOCs. Alpha, Beta, and Gamma were previously identified as circulating VOCs. VOIs include viruses with predicted genetic modifications and significant community transmission, suggesting an emerging risk to public health. Previously circulating VOIs include Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Theta, Iota, Kappa, Lambda, and Mu. Variants with genetic changes suspected to cause future risk were considered VUM (WHO, 2021). On March 11th, 2022, researchers identified the Deltacron, a new recombinant between delta and omicron variants (Ellis, n.d.). Few reports suggest that mutations in the delta-variant spike gene show similarity with omicron-like spike protein, resulting in deltacron (Kreier, 2022; Lang, 2022). The recombinant has 0.1–0.6% mean nucleotide diversity and 1163–1421 read mean sequencing depth from both the lineages. Deltacron has 156–179 codons for the spike gene from omicron, except at the N-terminal domain (NTD), a characteristic of the delta variant. The NTD of spike protein is more electropositive, which interacts with electronegative lipid rafts in the host cell plasma membrane. Similarly, RBD from omicron has a high affinity for the ACE-2 receptor of the host. These convergent mutations of both NTD and RBD increase the kinetic properties of deltacron for optimized virus-host binding (Colson et al., 2022).

1.3. Statistics of COVID-19

According to the WHO report, by October 14th, 2022, 620,301,709 total cumulative cases were confirmed globally, of which India has 44,621,319 cases. Cumulative deaths of 6,540,487 and 528,847 were noticed globally and in India, respectively (World Health Organisation, 2020). In India, number of active cases as on October 14th, 2022, are 26,583. The highest COVID-19 cases of 81,26,320 were recorded in the state of Maharashtra while, Andaman and Nicobar islands registered the lowest number of cases, i.e., 10,721 ("#IndiaFightsCorona COVID-19 in India, Vaccination, Dashboard, Corona Virus Tracker | mygov.in," n.d.). Vaccine development was ramped up globally as the pandemic outburst was proven effective. Globally and in India, 164 and 158.76 vaccine doses were administered per 100 population, respectively, and 63.46 and 68.78 individuals were vaccinated fully per 100 population with the last dose of the primary series (World Health Organisation, 2020).

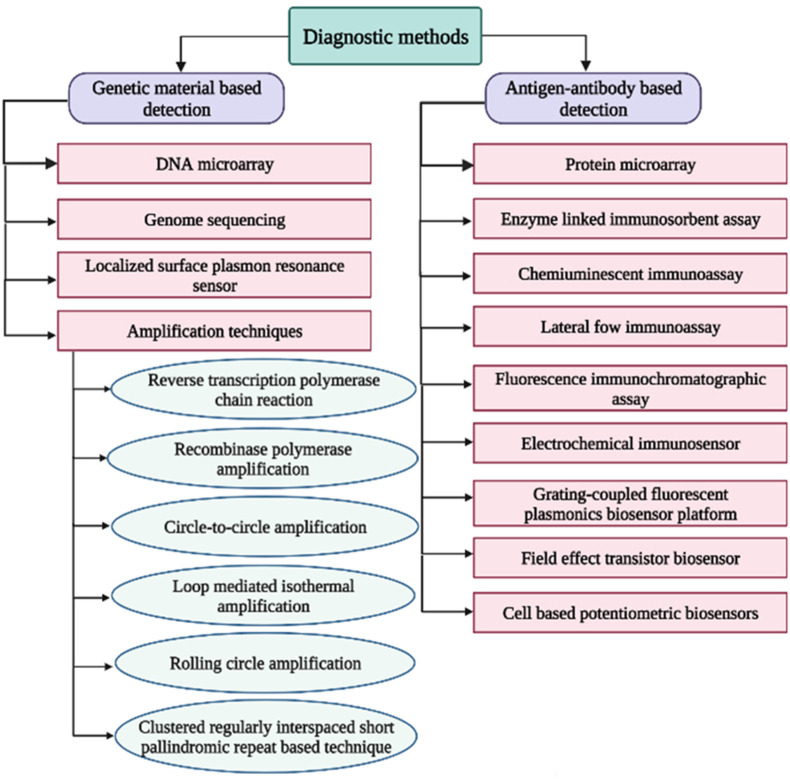

2. Diagnostic techniques for COVID-19

The diagnostic techniques for the detection of COVID-19 are based on various approaches such as nucleic acid amplification, identification of viral proteins, and detection of elevated levels of antibodies in the serum of previously infected individuals, also known as serological tests. The nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are more sensitive and specific but have several limitations, such as multi-step sample processing, longer detection time, and risk of contamination. RT-PCR and DNA microarray-based technology, the DetectX-Rv has been developed for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid (“COVID-19 | PathogenDx | DNA Based Pathogen,” n.d.). Antigen or antibody tests are rapid and easy to perform immunoassays and can be employed for POC diagnosis in clinical and household settings. The antigen tests are less sensitive than the NAATs but are very useful for screening, especially in congregate environments. Serological tests cannot be used to detect current infection and only measure antibodies developed by a prior infection. Serological tests are used widely for serosurveillance to determine what percentage of a population already has the disease. Most immunoassay techniques are based on nanodiagnostics and microfluidics. Protein microarrays are lab-on-chip (LOC) devices that detect protein binding interactions or their expression levels (Sutandy et al., 2013). An example of such microarray is the MosaiQ COVID-19 Antibody Magazine developed by Quotient Suisse SA for qualitative determination of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (“MosaiQ COVID-19 Antibody Microarray | Quotient,” n.d.). Another approach to COVID-19 diagnosis is the detection of increased or decreased levels of various immunological biomarkers in response to inflammation, especially interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is indicated in the "cytokine storm" (Ulhaq and Soraya, 2020). Fig. 2 shows a schematic of different diagnostic techniques for COVID-19.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the various diagnostic techniques for COVID-19.

2.1. Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

The most dependable and recommended lab-based diagnostic technique for COVID-19 disease is nucleic acid amplification by RT-PCR. This test performs reverse transcription of the viral RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) and amplifies certain regions of the cDNA. The target sequences include the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene, the open reading frame ORF1ab region, the envelope protein (E) gene, the nucleocapsid protein (N) gene, the spike protein (S) gene, and the helicase (Hel) gene (J. F.W. Chan et al., 2020; Corman et al., 2020). The first RT-PCR workflow developed in Germany by Corman et al. targeted the E, RdRp, and N genes and showed 95% detection efficiency (Corman et al., 2020). The proposed workflow for the SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis includes a preliminary screening test with the E gene, followed by a confirmatory test with the RdRp gene. Generally, nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab samples are collected for the diagnosis of the disease using RT-PCR, usually after 5–6 days of onset of symptoms since the viral load is high in those upper respiratory regions during early infection (“Interim Guidelines for Clinical Specimens for COVID-19 | CDC,” n.d.; Tang et al., 2020). Lower respiratory specimens may also be collected in certain cases, including sputum samples, tracheal aspirates, or bronchoalveolar lavage. The swab samples are collected in a viral transport medium and transported in ice. AB ANALITICA developed a one-step RT-PCR assay, REAL QUALITY RQ-2019-nCoV targeting the RdRp gene and E gene. It gives qualitative results for samples of nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage within 1 h 40 min (European Commission, 2022). One-step quantitative RT-PCR detection methods were designed by Chu et al. for identifying ORF1b and N regions of 2019-nCoV. The RT-PCR assay of the N gene and ORF1b gene was considered for screening and confirmatory, respectively (Chu et al., 2020). Another RT-PCR assay was reported by Chan and the group to identify SARS-CoV-2 RdRp/helicase, spike, and nucleocapsid genes. In this study, the RdRp/Hel assay showed a low limit of detection (LOD) for in vitro viral samples, high sensitivity, and no cross-reactivity (J. F. W. Chan et al., 2020).

2.2. Chest computerized tomography scan (CT scan)

Chest imaging is a non-invasive clinical characterization technique used in the acute care of patients with lung infections. CT scans have been used widely to confirm and monitor SARS-CoV-2 infection. CT scans and RT-PCR are the most recommended clinical diagnostic procedures for COVID-19 diagnosis. CT scan was a temporary diagnosing technique for COVID-19 used in China due to a lack of kits and RT-PCR false-negative results (Udugama et al., 2020). According to reports, the CT scans have a specificity of 25% and sensitivity of 84–98%, which was relatively higher than that of RT-PCR (Ai et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2020). Another study suggested that CT scans cannot discriminate or specify among different viruses (Cui and Zhou, 2020). Patients with ground-glass opacity (GGO) have twice the chance of COVID-19 infection (Abdollahi et al., 2021). In another study, CT scans of COVID-19 patients showed bilateral multifocal GGO and mixed GGO and consolidation (Jafari et al., 2020). Other typical findings include GGO, consolidation, peripheral reticulation, and crazy-paving patterns (Martínez Chamorro et al., 2021).

2.3. X-ray imaging

Chest X-ray (CXR) is a low-cost, useful first-line imaging test for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 individuals. However, X-ray sensitivity (69%) is less than CT (97–98%). X-ray findings include airspace opacities (consolidations or GGO) 10–12 days after the onset of symptoms. COVID-19 X-ray findings are classified into typical, indeterminate, atypical, or negative, depending on primary pattern and distribution morphology. X-rays are used in the digital chest tomosynthesis technique to collect data from different lung sections (Martínez Chamorro et al., 2021). The CXR showed 80.6% correct and 28.5% incorrect results, indicating moderate sensitivity and specificity for COVID-19 (Islam et al., 2021).

2.4. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning

MRI is a non-invasive diagnostic technique for COVID-19-suspected and confirmed patients. Because of pulmonary tissue airiness and breathing movements, MRI has a low anatomic resolution (less signal-to-noise ratio) and poor quality images (Vasilev et al., 2021). MRI may be performed frequently to monitor the lung health of patients with COVID-19. The most common findings include GGO and consolidation. The sensitivity and specificity values observed for MRI are 91.7% and 100%, respectively, taking CT findings as a reference (Palmer, 2020).

2.5. Genome sequencing

A metagenomic study of viruses is used to identify SARS-CoV and other infections influencing COVID-19 severity. At the same time, amplicon-based sequencing helps to identify genetic variation, molecular epidemiology, viral evolution, and contact tracing. Sequence-independent single primer amplification (SISPA) is a metagenomic approach used to check for sequence divergence (Carter et al., 2020). Moore et al. used amplicon and metagenomic-based sequencing, MinION, for SARS-CoV from the patient's nasopharyngeal swab (Moore et al., 2020).

2.6. Microarray technique

Microarray is a chip-based, rapid, high-throughput detection technique to identify genes, nucleotide sequences, mutations, diseases, polymorphism, gene interactions, forensics, biomedical applications, and drug screening. Based on immobilized compounds, microarrays are aptamer-based microarrays and proteome-based microarrays. In aptamer-based SARS-CoV detection, viral DNA is reverse-transcribed into cDNA and labeled with fluorescent dyes. These labeled probes are allowed to hybridize with specific oligonucleotides immobilized on a microarray chip, washed, and a signal is detected. In contrast, peptide sequences of viral coat proteins are immobilized and allowed to hybridize with viral antibodies from the sample in the proteome-based microarray. Microarrays are used to detect different strains of SARS-CoV and spike (S) gene mutations of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) with 100% accuracy (Guo et al., 2014).

2.7. Biosensors

Biosensors are small, simple, sensitive, portable, and analytical devices consisting of a bioreceptor, a transducer, and a signal processor. Based on technology, biosensors are classified into optical, electrochemical, piezoelectric, and thermal biosensors. Biosensors for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection include nucleic-acid-based, CRISPR-Cas9-based paper strips, antigen-Au/Ag nanoparticles-based, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and optical biosensors.

2.7.1. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based devices

CRISPR-Cas platforms are used widely as POC technology. CRISPR systems involve a CRISPR RNA or guide RNA that binds to the target DNA or RNA sequence and effector Cas proteins with nuclease activity (Vatankhah et al., 2020). Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter UnLOCKing (SHERLOCK) assay and DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter (DETECTOR) assay are the two methods developed by Sherlock Biosciences and Mammoth Biosciences, respectively, to detect viral RNA. Most platforms use Cas 12 for the DETECTOR method and Cas 13 for the SHERLOCK method (Carter et al., 2020). Several isothermal amplification-mediated-CRISPR-based biosensing systems, such as SHERLOCK and SHERLOCK-COVID, have been developed (Joung et al., 2020). A CRISPR-based diagnostic test called FNCAS 9 Editor Linked Uniform Detection Assay (FELUDA) was developed by Tata Group and CSIR-IGIB, India; that utilizes a Cas 9 protein and can detect SARS-CoV-2 with high sensitivity and specificity at a minimal cost (Azhar et al., 2020). Advanced Cas 13-based CRISPR diagnostic test that can be paired to a smartphone camera is reportedly being developed by UC Berkley and Gladstones University in collaboration with Nobel Laureate Jennifer Doudna ("Pairing CRISPR with a smartphone camera, this COVID-19 test finds results in 30 minutes | FierceBiotech," n.d.). CRISPR-Cas 12-based lateral flow assay (LFA), DETECTOR (SARS-CoV-2) developed by Broughton et al. targets E and N genes detection with a detection limit of 10 copies per μL. This device recorded a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 100%, respectively (Broughton et al., 2020). Another study developed a CRISPR-Cas 12-based diagnostic technique for recognizing the ORF1ab SARS-CoV-2 sequence. The technique reported a detection time of 30 min, having 10 copies/μL as a detection limit (Curti et al., 2020). Bruch et al. designed a graphene field-effect transistor (GFET)-based electrical biosensing platform along with Cas 9 immobilized on it for easier nucleic acid detection (Bruch et al., 2019). Hajian et al. established a biological sensor, GFET, using CRISPR-Chip technology for COVID-19 detection with 1.7 fM LOD within 40 min (Hajian et al., 2019).

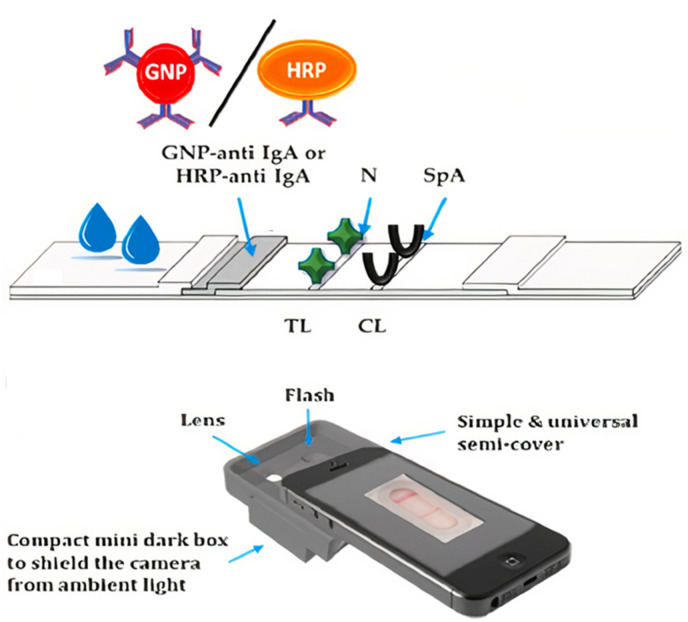

2.7.2. Lateral flow assay/immunoassay (LFA/LFIA)

LFIA are small, rapid, portable, qualitative, and POC devices for SARS-CoV detection by analyzing biomarkers like antigens, antibodies, nucleic acids, and whole viruses. Multiplex LFA is used to detect RT-PCR amplified RdRp, ORF3a, and N genes simultaneously within 30 min with a detection limit of 10 copies per test. A multienzyme field-deployable method, reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification lateral flow assay (RT-RPA-LFA), has been used to detect the N gene with a LOD of 1 ag (Xia and Chen, 2020). Hybrid Capture Fluorescence Immunoassay (HC-FIA) was fabricated for viral RNA genes N, E, or ORF1ab and achieved a LOD of 500 copies per mL (Wang et al., 2020). A dual optical/chemiluminescent LFIA for salivary and serum IgA was developed by Roda et al. using recombinant N protein to capture IgA. Gold nanoparticles (AuNP)-anti-IgA and anti-human IgA-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) bioconjugates were prepared and immobilized on the conjugate pad for optical IgA-LFIA and chemiluminescent LFIA (CL-LFIA), respectively. Staphylococcal protein A (SpA) was spotted at the control line of LFIA. In optical LFIA, colorimetric results were evaluated semi-quantitatively after 15 min using a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS)-based camera inside a 3D-printed mini dark box, as shown in Fig. 3 . For CL-LFIA detection, a transparent glass fiber pad with luminol, p-iodophenol, and freeze-dried sodium perborate was used to measure IgA-HRP bioconjugate activity at the test line. After 15 min of LFIA assay, the glass fiber pad was placed over the detection membrane, water was added to re-suspend it, and the signal was detected using a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) reader (Roda et al., 2021). Another study reported that a DNA scaffold hybrid chain reaction (DNHCR)-based biosensing assay could be developed into an LFA (Jiao et al., 2020). Almost all the LFA techniques utilize nanoparticles as a base material for detection. These nanodiagnostic techniques are covered in detail in another section.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of optical semi-quantitative LFIA using CMOS-based camera [Reprinted with permission from (Roda et al., 2021), Copyright 2020 Elsevier].

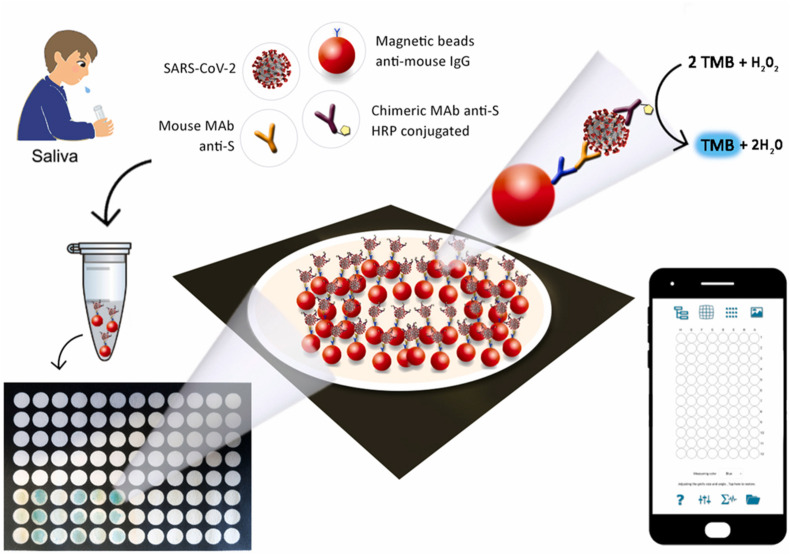

2.7.3. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA is used to identify the presence of antigens (direct ELISA) or antibodies (indirect ELISA) in the sample. Using the ELISA technique, IgG and IgM antibodies were detected using Rp3 nucleocapsid protein from SARS-CoV (W. Zhang et al., 2020). It was observed that levels of C-reactive protein and D-dimer were elevated in infected patients; thus, both could be used as markers (Guan et al., 2020). A novel 96-well wax-printed paper-based ELISA immunoassay was fabricated for SARS-CoV-2 detection in saliva. The device contains magnetic beads to hold immunological chains, and results were interpreted colorimetrically using a smartphone with a spotxel free-charge app. First, monoclonal antibody (MAb) conjugated, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) blocked magnetic beads anti-mouse IgG were prepared and mixed with chimeric MAb-HRP anti-SARS-CoV-2 as illustrated in Fig. 4 . The unreacted labeled antibodies were washed, and the resulting suspension was added to the 3,3',5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) pre-loaded-96-well wax-printed paper. The immunosensor has a detection range of 0.1 μg/mL to 10 μg/mL for the S protein (Fabiani et al., 2021).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of 96-well wax-printed paper-based ELISA immunoassay [Reprinted with permission from (Fabiani et al., 2021), Copyright 2021 Elsevier].

2.7.4. Other biosensors

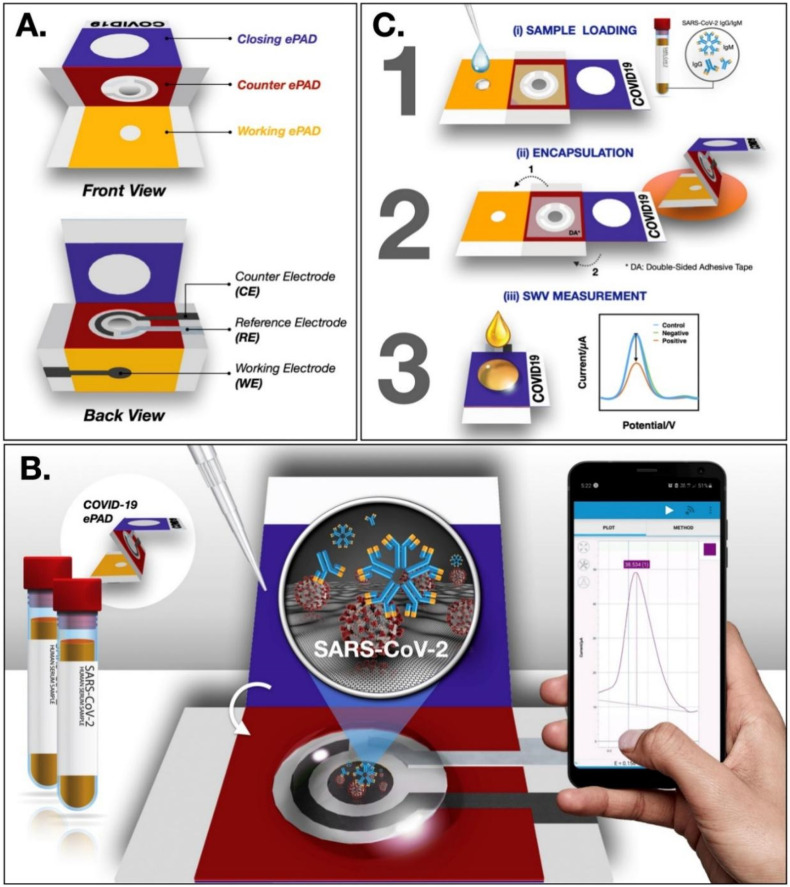

A naked-eye detection technique that requires the fabrication of covalent organic framework (COF) capsules for HRP encapsulation has been reported. These capsules provide a suitable enzyme microenvironment and help recognize SARS-CoV-2 RNA ranging from 5 pM to 50 nM with a LOD of 0.28 pM (Wang et al., 2022). Another study developed a label-free paper-based electrochemical biosensor for SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection using SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. This device comprises three folding parts: working ePAD, counter ePAD, and closing ePAD. ([Fe(CN)6]3-/4-) applied to the closing ePAD was used as an electrochemical redox indicator. This biosensor achieved a LOD of 1 ng/mL with high sensitivity and specificity (Yakoh et al., 2021). Fig. 5 illustrates the principle, components, and detection method of the COVID-19 ePAD device. An increased level of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the lungs is an essential biomarker of lung infection. Another study reported the real-time electrochemical biosensor that detects ROS in the sputum sample to diagnose COVID-19. The device showed a sensitivity and accuracy of 97% for clinical samples (Miripour et al., 2020). A piezoelectric immunosensor was developed back in 2004 to identify SARS-CoV-1. The sensor detects analyte from atomized aerosol of sputum samples in the range of 0.6–4 μg/mL within 2 min (Zuo et al., 2004). A cell-based biosensor was reported by Mavrikou et al. for the detection of the SARS-CoV-2, S1 subunit of the spike protein using a bioelectric recognition assay (Mavrikou et al., 2020). The mammalian cell membrane-bound human chimeric antibody could interact with the viral antigen, resulting in a change in the membrane structure and potential and generating a strong response.

Fig. 5.

Paper-based biosensor, COVID ePAD showing (A) components, (B) principle, and (C) detection method for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [Reprinted with permission from (Yakoh et al., 2021), Copyright 2020, Elsevier].

2.8. Other amplification techniques

2.8.1. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)

In addition to RT-PCR, other isothermal amplification techniques for nucleic acid detection include recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) (Behrmann et al., 2020), rolling circle amplification (RCA), circle-to-circle amplification (C2CA) (Tian et al., 2020), and LAMP. In LAMP, four primers are used, of which two are forward primers and two backward primers. Initially, all four primers are used, but later only the forward inner primer and the backward inner primer are used for cycling (Notomi et al., 2000). The final reaction mixture consists of stem-loop DNAs with cauliflower-like structures. The advantage of the LAMP technique over conventional RT-PCR is that nucleic acid amplifies at a single temperature of 65 °C, and a thermocycler is not required; this helps in a rapid and easy diagnosis of the disease. In LAMP, the use of four primers enhances target selectivity and specificity. The addition of the reverse transcriptase enzyme to the LAMP assay can help to amplify DNA from RNA (Mori and Notomi, 2009; Notomi et al., 2000). Several reverse transcription-coupled LAMP (RT-LAMP) assays have been reported that can directly detect viral RNA with comparable sensitivity to the RT-PCR technique (W. E. Huang et al., 2020; Lamb et al., 2020). A POC-based RT-LAMP technology called Lucira COVID-19 All-In-One Test Kit was issued by emergency use authorization (EUA) for self-testing at home (“Lucira All-In-One Test Kit,” n.d.). A rapid COVID-19 diagnostic test, i.e., isothermal LAMP-based colorimetric method for COVID-19 (iLACO), has been reported. A color change in the sample (from pink to light yellow) confirmed the successful amplification of the ORF1 ab gene (Yu et al., 2020).

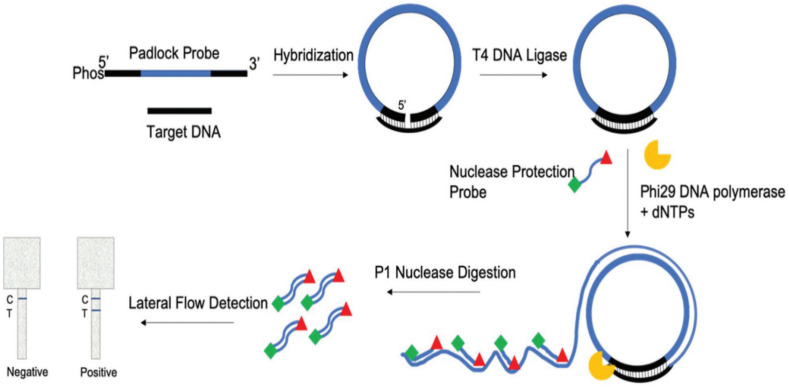

2.8.2. Rolling circle amplification (RCA)

RCA is a quick, sensitive, and highly efficient isothermal PCR-based assay to detect SARS-CoV levels. Circularizable oligonucleotides or padlock probes containing target complementary sequences are hybridized with target DNA or RNA sequences to form circularized probes. Amplification of these circularized probes is performed using primers and DNA polymerases. Circularized probes do not require reverse transcriptase for RNA amplification as in traditional PCR. RCA can be performed in liquid and solid phases (uses oligonucleotide-coated magnetic beads). Coronavirus detection capability by RCA is amplified 109-folds within 90 min with minimal reagents (Wang et al., 2005). Using the Padlock Rolling Circle Amplification Nuclease Protection Lateral Flow Assay (PLAN-LFA) platform, an assay has been reported to detect SARS-CoV-2 in saliva. The PLAN-LFA assay is described in Fig. 6 . A padlock probe was designed complementary to the target sequence, hybridized, and ligated, resulting in a circular template. The circular template was amplified by RCA using polymerases and labeled with nuclease protein probes. When nucleases were added to the linear concatenated RCA product, only double-stranded labeled probes were protected from digestion, and colorimetric LFA detected the generated fragments. The assay obtained a detection limit of 1.1 pM target DNA (1.3 × 106 copies per reaction) (Jain et al., 2021). RCA with nylon mesh medium containing multiple microfluidic pores was incubated for 15 min and used to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 with a LOD of 0.7 aM (Kim et al., 2021).

Fig. 6.

Schematic of PLAN-LFA assay [Reprinted with permission from (Jain et al., 2021), Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2021)]

2.8.3. Circle-to-circle amplification (C2CA)

C2CA is a nucleic acid amplification process with many rounds of padlock probe ligation and RCA. Multiple circles formed after the first round of amplification are endonuclease digested, ligated, and used as templates for the second round of amplification, resulting in billions of amplified products. Homogenous circle-to-circle amplification (HC2CA) is a one-pot real-time amplification process with two rounds of RCA. The RdRp gene in SARS-CoV-2 was identified using an HC2CA-based optomagnetic biosensor with a LOD of 0.4 fM in 100 min (Tian et al., 2020).

2.9. Intelligence-based techniques

Considering the limitations of standard diagnostic techniques, multiple deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML) techniques and models were developed for COVID-19 detection using CT, X-ray, and electrocardiogram (ECG) images. Deep learning algorithms such as convolutional neural network (CNN), Zeiler and Fergus network (ZFNet), and dense convolutional network-121 (DenseNet121) were used for training, validation, and testing of COVID-19 detection. Considering the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score as performance parameters, customized CNN showed better performance (Catal Reis, 2021). Using a deep CNN, abnormalities in the cardiovascular system of COVID-19-affected patients were studied using paper-based ECG images. The developed method reported accuracy of 98.57% in differentiating COVID-19 cases from control (Irmak, 2022).

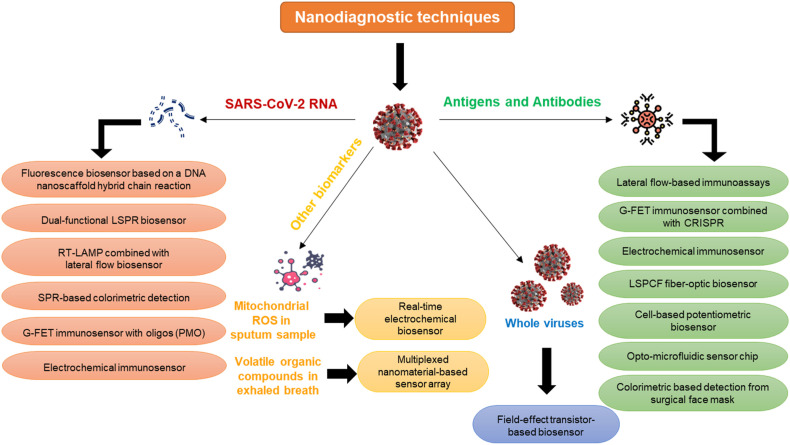

3. Nanodiagnostic techniques for COVID-19 detection

The field of nanotechnology utilizes nanoscale material for cutting-edge research and development across various domains such as physics, chemistry, life science, engineering, information technology, and material sciences. Nanotechnology has brought revolutionary innovations, particularly in the field of biological sciences. Some typical applications of nanotechnology in this field include the detection of biomarkers and infectious diseases, cancer therapy, targeted drug delivery, food safety, and environmental monitoring. The most prominent crisis humankind faces in the modern world is health care issues, especially infectious disease outbreaks. These outbreaks can spread quickly if containment measures are not vigorously implemented. Detection and diagnosis of disease-causing agents is the primary step to containment in the absence of a preventive measure such as a vaccine. RT-PCR technique has high sensitivity and specificity for COVID-19 detection. But with the rapid spread of the disease, quicker and easier diagnostic alternatives were needed. Isothermal amplification techniques, CRISPR-based techniques, and serological tests were developed to facilitate rapid testing in affected populations. Continued emphasis has been put on developing POC devices and LOC technologies.

Nanodiagnostic tools are advanced diagnostic devices developed by integrating nanotechnology with biomedical engineering. The development of nanotechnology-based diagnostic devices has revolutionized the medical field with the introduction of miniaturized diagnostics (Borse et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2022; Borse and Srivastava, 2019, 2020; Kaur et al., 2021; Konwar and Borse, 2020; Roy et al., 2022). Fig. 7 shows a schematic classification of all the nanotechnology-based biosensing platforms developed. These diagnostic devices significantly reduce the turn-around time for disease diagnosis and are usually cheap and easy to use. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these devices have facilitated early detection, continuous monitoring, and surveillance.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the nanotechnology-based diagnostic devices.

3.1. Nanosensors

Nanodiagnostic techniques for diagnosing COVID-19 are being developed worldwide, while many have already been approved for use (Konwar and Borse, 2020). Because of their small size, nanomaterials have unique physical and chemical features. The fundamental component of nanodiagnostic devices is the nanobiosensor. Nanobiosensors can recognize an analyte based on a biorecognition event and convert it to a readable electric signal using a transducer. The biorecognition element is conjugated on the surface of the nanoparticles by covalent or non-covalent interactions. The conjugated material may be protein, nucleic acid, enzyme, aptamers, or peptides. The signal generated by the biorecognition event may be qualitative or quantitative. The nanomaterial can either be a detection molecule, immobilizing the surface, or even the transducer itself (Borse et al., 2016; Borse and Srivastava, 2020).

Selectivity of biosensors is improved by fabrication utilizing various nanomaterials such as colloidal gold, gold nanofilms, palladium nanofilms, reduced graphene oxide, activated graphene oxide, gold nanostars, cobalt-functionalized TiO2, and poly-aniline (Kumar et al., 2022; Patil et al., 2019). Zhu et al. developed a nanoparticle-based biosensor (NBS), RT-LAMP-NBS, with RT-LAMP technology for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. The device can detect the N gene and ORF1ab in a single step with a sensitivity of 12 copies per reaction (X. Zhu et al., 2020). Mahari and co-workers reported CovSens, a biosensor with fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) electrode, AuNPs, and nCOVID-19 antibodies coated on a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE). When antigens interact with this FTO/AuNPs/nCovid-19 Ab-modified electrode, a change in electrical conductivity was measured. It detects spike protein antigens with a concentration ranging from 1 fM to 1 μM (Mahari et al., 2020).

A dual-functional plasmonic biosensing system has been developed, integrating plasmonic photothermal (PPT) and localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effects. It utilizes 2D gold nanoislands conjugated with DNA receptors that can detect viral SARS-CoV-2 target sequences such as ORF1ab, RdRp gene, and E gene. This biosensor showed increased sensitivity and low LOD of up to 0.22 pM (Qiu et al., 2020). Cady et al. developed a grating-coupled fluorescent plasmonics (GC-FP) based multiplexed biosensing platform that could discriminate and perform quantitative estimation of antibodies binding to multiple antigens. The biosensor measures immune complex interactions of multiple targets from serum and dried blood samples with 100% selectivity (Cady et al., 2021). Huang et al. reported a localized surface plasmon coupled fluorescence (LSPCF) fiber-optic biosensor to detect SARS-CoV N protein ranging from 0.1 pg/mL to 1 ng/mL. Compared to conventional ELISA, LSPCF had a 104-fold higher detection limit (Huang et al., 2009). A naked-eye colorimetric detection technique based on the change in SPR for the SARS-CoV-2 N gene was designed by Moitra et al. by fabricating thiol-modified-antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) capped AuNPs and achieved a LOD of 0.18 ng/μL (Moitra et al., 2020). For MERS-CoV detection, Kim et al. used AuNPs to develop a label-free colorimetric technique. Target analytes were determined by color change based on aggregation and optical properties, and the sensor showed a LOD of 1 pmol/μL (Kim et al., 2019).

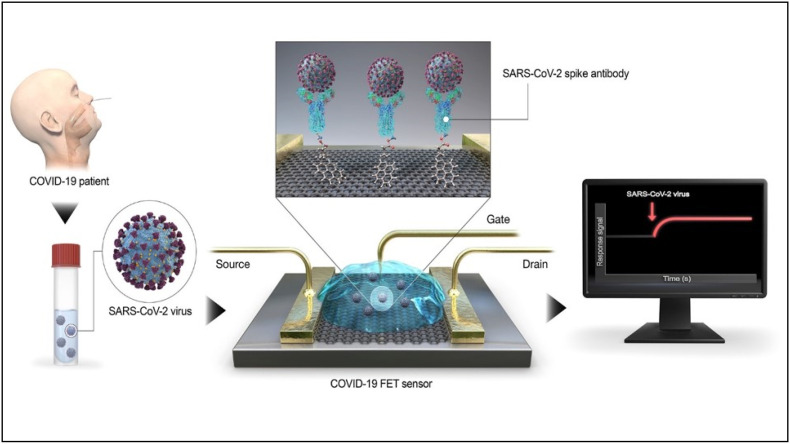

A Field-effect transistor (FET) based biosensor was developed by Zhang et al. that could detect the spike glycoprotein of the virus by immobilizing the RBD on graphene sheets (X. Zhang et al., 2020). A similar FET-biosensor was developed by Seo et al. that anchored the spike-protein specific antibodies on the surface of the graphene sheets via 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Seo et al., 2020). Fig. 8 describes the working of the FET-based biosensing platform. The viral antigen from the nasopharyngeal swab sample of an infected individual could be detected by conjugation event with the immobilized antibodies, resulting in electrical response. In clinical samples, the LOD for the sensor was found to be 2.42 × 102 copies/mL without any interference with the MERS-CoV antigen. An amplification-free SARS-Cov-2 RNA detection technique was developed using gold nanoparticle conjugated GFET and phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligos (PMO). The device showed a LOD of 0.37 fM within 2 min and could distinguish between the RdRp of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV (Li et al., 2021).

Fig. 8.

GFET biosensor for detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein using spike protein-specific antibodies anchored to the graphene sheet using 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester [Reprinted with permission from (Seo et al., 2020), Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.0c02823; Note to readers - Further permission related to the material excerpted should be directed to the ACS].

Alafeef et al. developed a paper-based electrochemical sensor for SARS-CoV-2 by fabricating electrodes with AuNPs conjugated with N gene ASOs. The sensor achieved a sensitivity of 231 copies/μL and accuracy of nearly 100%, with a detection limit of 6.9 copies/μL within 5 min (Alafeef et al., 2020). Layqah and co-workers fabricated an electrochemical immunosensor for detecting MERS-CoV spike S1 protein by coating AuNPs on a carbon electrode. The developed biosensor achieved a LOD of 1.0 pg/mL within 20 min (Layqah and Eissa, 2019). To detect SARS-CoV-2 DNA sequences, an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) nanostructured DNA biosensor was constructed using thiol-modified gold nanomaterial electrodes (mixture of gold nano triangles and AuNPs), [Ru(bpy)3]2+ as luminophore, and carbon dots for ECL signal detection. This device has the advantages of high selectivity, reproducibility with a detection limit of 514 aM, and able to detect SNPs in viruses (Gutiérrez-Gálvez et al., 2022).

Ahmed et al. developed a fluorescence-based immunosensor with zirconium quantum dots (Zr QDs) nanocrystal for the detection of infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) of coronavirus (Ahmed et al., 2018). Ishikawa et al. reported Indium (III) oxide (In2O3) nanowire biosensors using antibody analog protein and fibronectin as a capture probe to detect nucleocapsid protein of SARS. The biosensor has a response time of 10 min, even at sub-nanomolar concentrations (Ishikawa et al., 2009). Lanthanide-doped polystyrene nanoparticles (LNPs) were used to develop a biosensor for detecting SARS-CoV-2 IgG in human serum. This immunosensor is used to diagnose suspicious COVID-19 cases due to the lack of accurate anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG standards (Chen et al., 2020). Martinez-Paredes and co-workers designed a genosensor for SARS detection. The genosensor was fabricated by screen-printing gold nanostructures on a carbon electrode through thiol-gold interaction. The device achieved 2.5 pmol/L and 1.76 μA/pmol/L of LOD and sensitivity, respectively (Martínez-Paredes et al., 2009).

Jadhav et al. developed a device for SARS-CoV-2 detection by combining microfluidic and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) techniques. Silver or gold-fabricated carbon nanotubes were used in microchannels to amplify Raman intensity (Jadhav et al., 2021). An opto-microfluidic sensor chip was designed to detect antibodies against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The sensor is based on the LSPR phenomenon and contains gold nanospikes immobilized with viral S protein. The device can detect spike protein antibodies from 1 μL of plasma within 30 min and obtain a LOD of 0.08 ng/mL (Funari et al., 2020). A cotton thread-based microfluidic immunosensor device has been developed to rapidly detect IBV and avian coronavirus (Weng and Neethirajan, 2018).

A novel biosensor was developed for detecting COVID-19 from exhaled air. The multiplexed device contains an array of AuNPs with organic ligands to sense volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath. Ligand-fabricated AuNPs shrink or swell when exposed to volatile organic compounds, resulting in a change in electrical conductivity. The device showed an accuracy of 90% and 95% in distinguishing COVID-19-confirmed patients from patients with non-COVID lung infection controls (Shan et al., 2020). Another non-invasive colorimetric-based detection technique using nanoparticles includes SARS-CoV antigens from surgical face masks. The polypropylene layer of the mask captures aerosols and droplets and detects them using a biosensor mixture that binds to viral antigens. The colorimetric signal was quantified with a smartphone app and achieved sensitivity and specificity of 96.2% and 100%, respectively, within 10 min (Vaquer et al., 2021).

3.2. Nanodiagnostic-based LFA devices for COVID-19

Several nanodiagnostic devices for COVID-19 detection are in the developmental stage, while some have been approved for use and are available commercially. The most popular nanobiosensor-based devices are the LFAs that use detector molecules to recognize immune-complex reactions in serological tests. The LFA-based tests can be used at home and require minimum operating skill (Borse and Srivastava, 2019). Generally, the detection molecule is an antibody or an antigen. The lateral flow immunosensing technique forms the basis for most of the rapid antigen and antibody tests. The AuNPs are widely used in LFAs because of their unique properties, such as high surface-to-volume ratio, photothermal effect, high biocompatibility, and fluorescence emission. An LFIA-based device was developed to detect IgG antibodies for SARS-CoV-2. The nucleocapsid protein was immobilized on the strip, and AuNPs were conjugated with anti-human IgG. The colorimetric assay obtained 69.1% and 100% of sensitivity and specificity, respectively, within 20 min (Wen et al., 2020). An immunochromatographic test (ICT) assay, Ag Respi-Strip, has been developed to detect SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal samples. It uses colloidal gold nanostructures and monoclonal antibodies against the nucleoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. Developed assay showed specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy of 99.5%, 57.6%, and 82.6%, respectively (Mertens et al., 2020). Another ICT-based lateral-flow device was fabricated using AuNPs to detect the SARS-CoV-2 IgM in serum. The AuNP-LFA device requires a sample volume of 10–20 μL and reported sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 93.3%, respectively, within 15 min (C Huang et al., 2020). Table 1 summarizes the LFA-based commercial kits for COVID-19 diagnosis that have been issued emergency use authorization (EUA) by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Table 1.

Lateral flow immunoassay-based COVID-19 diagnostic kits that FDA has issued EUA.

| Device name | Sample | Nanomaterial | Target | Time required | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Manufacturer | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CareStart COVID-19 Antigen test | Nasopharyngeal swab | NanoActTM cellulose nanobeads | Nucleocapsid protein | 10–15 min | 88.4 | 100 | Access Bio, Inc., USA | (“CareStart Antigen Test,” n.d., “CareStartTM COVID-19 Antigen test kit using NanoActTM launched in the U.S. | BioSpace,” n.d.) |

| CareStart COVID-19 IgM/IgG | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Colloidal gold | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 10–15 min | 98.4 | 98.9 | Access Bio, Inc., USA | (FDA, 2020; “CareStart COVID-19 IgM/IgG Test,” 2021) |

| CareStart EZ COVID-19 IgM/IgG | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 10–20 min | 100 | 100 | Access Bio, Inc., USA | (FDA, 2020; “For use under Emergency Use Authorization only For in vitro diagnostic use only For prescription use only EZ COVID-19 IgM/IgG Package Insert (Instructions for Use),” 2021) | |

| BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card | Direct Nasal swab | Nucleocapsid protein | 15–30 min | 97.1 | 98.5 | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough, Inc., USA | (“Abbott's USD 5, 15-Minute BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card Becomes First Diagnostic Test with Read-Result Test Card to Receive FDA EUA - COVID-19 - Labmedica.com,” n.d., “BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag CARD,” n.d.) | |

| LYHER 2019-CoV IgM/IgG Antibody Combo Test Kit | Serum, plasma | Spike protein | 10–15 min | 100 | 98.8 | Hangzhou Laihe Biotech Co., Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “Lyher Antibody Combo Test Kit,” 2020) | |

| Assure COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Device | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 15–30 min | 100 | 98.8 | Assure Tech (Hangzhou) Co., Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “Assure Rapid Test Device,” 2020) | |

| RightSign COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Casette | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 10–20 min | 100 | 100 | Hangzhou Biotest Biotech Co., Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “RightSign Rapid Test Casette,” 2020) | |

| Innovita 2019-nCoV Ab Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 10–15 min | 100 | 97.5 | Innovita (Tangshan) Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China | (Innovita Ab Test,; “2019-nCoV Ab Test (Colloidal Gold) (IgM/IgG Serum/Plasma/Venous whole blood Combo),” n.d., | |

| Orawell IgM/IgG Rapid Test | Serum, plasma | Spike protein | 10–15 min | 100 | 94.8 | Jiangsu Well Biotech co., Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “Orawell Rapid Test,” 2020) | |

| BIOTIME SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Qualitative Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 10–30 min | 100 | 96.2 | Xiamen Biotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “BIOTIME Rapid Test,” 2020) | |

| Biohit SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG Antibody Test Kit | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Nucleocapsid protein | 15–20 min | 96.7 | 95.0 | Biohit Healthcare (Hefei) Co. Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “Biohit Antibody Test,” 2020) | |

| Nirmidas COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) IgM/IgG Antibody Detection Kit | Serum, plasma | Spike protein | 10–15 min | 96.6 | 97.9 | Nirmidas Biotech, Inc., USA | (FDA, 2020; “Nirmidas Antibody Detection Kit,” 2020) | |

| MidaSpot COVID-19 Antibody Combo Detection Kit | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 18–25 min | 100 | 96.2 | Nirmidas Biotech, Inc. | (FDA, 2020; “MidaSpot COVID-19 Antibody Combo Detection Kit - Instructions for Use,” n.d.) | |

| SGTi-flex COVID-19 IgG | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 10–30 min | 96.7 | 100 | Sugentech, Inc., South Korea | (FDA, 2020; “SGTi-flex COVID-19 IgG Test,” 2021) | |

| TBG SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Kit | Serum, plasma | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 15 min | 93.3 | 95.0 | TBG Biotechnology Corp, Taiwan | (FDA, 2020; “TBG Rapid Test Kit,” 2020) | |

| Tell Me Fast Novel COVID-19 IgG/IgM Antibody Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 10–15 min | 93.3 | 96.2 | Biocan Diagnostics Inc., Canada | (FDA, 2020; “Tell Me Fast Antibody Test,” 2020) | |

| Rapid COVID-19 IgM/IgG Combo Test Kit | Serum, plasma | Nucleocapsid protein | 15–20 min | 100 | 95.0 | Megna Health, Inc., USA | (FDA, 2020; “Rapid Antibody Combo Test Kit,” 2021) | |

| Sienna-Clarity COVIDBLOCK COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 10–20 min | 93.3 | 98.8 | Salofa Oy, Finland | (FDA, 2020; “Sienna Clarity Test Casette,” 2021) | |

| WANTAI SARS-CoV-2 Ab Rapid Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 15–20 min | 100 | 98.8 | Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Ltd., China | (FDA, 2020; “Wantai Rapid Test,” 2021) | |

| COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 10–15 min | 100 | 97.5 | Healgen Scientific LLC, USA | (FDA, 2020; “COVID-19 Rapid Test Casette,” 2022) | |

| ACON SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike & Nucleocapsid protein | 15–20 min | 100 | 96.2 | ACON Laboratories, Inc. | (FDA, 2020; ACON, n.d.) | |

| RapCov Rapid COVID-19 Test | Blood | Nucleocapsid protein | 15–20 min | 90.0 | 95.2 | ADVAITE, Inc | (FDA, 2020; ADVAITE, n.d.) | |

| CovAb SARS-CoV-2 Ab Test | Oral Fluid | Spike protein | 15–20 min | 97.1 | 97.4 | Diabetomics, Inc | (FDA, 2020; “CovAb SARS-CoV-2 Ab Test,” n.d.) | |

| SCoV-2 Detect IgG Rapid Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 20–25 min | 100 | 100 | InBios International, Inc | (FDA, 2020; InBios, 2021) | |

| ADEXUSDx COVID-19 Test | Serum, plasma, whole blood | Spike protein | 15–30 min | 93.3 | 100 | NOWDiagnostics, Inc. | (FDA, 2020; “ADEXUSDx COVID-19 Test - Instructions for Use,” n.d.) | |

| QIAreach Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Total Test | Serum, plasma | Fluorescent nanoparticles | Spike protein | 10 min | 100 | 97.5 | QIAGEN, GmbH | (FDA, 2020; “QIAreach Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Total Test - Instructions for Use,” 2022) |

The extraordinary features of nanoparticles for detecting COVID-19-specific markers can be coupled to a smartphone-based platform for easy monitoring and surveillance. The rapid antigen test developed by Abbott was paired with an in-built mobile app called NAVICA that functions as a digital “boarding pass”. It could be used to verify an individual's negative test result (“Abbott's USD 5, 15-Minute BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card Becomes First Diagnostic Test with Read-Result Test Card to Receive FDA EUA - COVID-19 - Labmedica.com,” n.d.).

3.3. Advantages and disadvantages of nanodiagnostic devices

The advantages of nanodiagnostic devices can be attributed to the unique features of the constituent nanomaterial. The use of nanobiosensors for developing diagnostic devices is favored by several benefits, such as a low LOD, ease of use, quicker diagnosis, and possible miniaturization (Borse and Srivastava, 2020; Borse et al., 2020b). In this way, the use of nanomaterials favors the development of POC diagnostic devices. The most significant advantage is the reduction in time between sample registration and acquisition of results, i.e., the turnaround time; thus, advantageous as compared to the molecular diagnostic techniques. It facilitates the early isolation of diseased individuals and prevents the disease from spreading to society. It also reduced the workload of healthcare workers, which was particularly helpful in managing COVID-19 spread. These devices are also easy to use and require minimum skills. These devices lack elaborate steps, most of which are a one-step process. Thus, volunteers and primary healthcare workers can participate in conducting tests using those devices. These devices do not require sophisticated equipment and are portable or handheld. The low cost of diagnostic tests using such devices is also an added advantage, especially for mass screening and resource-constrained settings. Nanodiagnostic devices showed the extended utility of essential healthcare services along with COVID-19 testing facilitation to the remote population at an affordable cost. Most nanodiagnostic devices show comparable sensitivity and specificity to conventional diagnostic techniques. Many such devices can be integrated with a smartphone or cloud-based software for surveillance purposes. Nanodiagnostic devices have made personalized healthcare a reality.

Despite their several advantages, there are certain limitations to using nanodiagnostic devices. The most common nanodiagnostic devices are the ones based on optical biosensors. These devices are rapid and have impressive sensitivity for detecting disease-causing agents. However, the signal produced by AuNPs-based LFIA is qualitative. Thus, they cannot provide a quantitative estimation of the target analyte-ligand binding. This disadvantage can be overcome by using electrochemical biosensors instead of optical ones. But they require auxiliary and specialized equipment for their data interpretation; hence, their miniaturization and portability are impeded. It applies to magnetic and plasmonic technologies as well. SPR-based biosensors also show low specificity and signal-to-noise ratio (Damborský et al., 2016). Although they enhance selectivity and sensitivity, label-based biosensors are disadvantageous owing to the extra cost of labeling and possible alteration of binding properties of the conjugating element (Daniels and Pourmand, 2007). It affects the sensing of protein analytes and can be addressed by indirect labeling using the sandwich ELISA model.

4. Summary and future perspectives

The global COVID-19 pandemic has left healthcare systems in all countries struggling to cope with the growing number of variants and deaths. Researchers across the globe have been working meticulously to develop diagnostic devices, therapeutic drugs, and vaccines that can address the COVID crisis. Most of the developed devices did not meet the requirements of clinical trials and needed upgradation for commercialization. Although several vaccine candidates have been developed and approved, emerging COVID variants are a concern. A growing number of infections call for easier and quicker ways of diagnosis. Although conventional RT-PCR is more accurate, POC techniques such as LAMP, CRISPR, and nanodiagnostics lead the way for rapid and more convenient COVID-19 detection. The advantages and disadvantages of the various diagnostic techniques are summarised in Table 2 . Nanodiagnostic devices have gained popularity for a long time in detecting disease-causing bacteria and viruses because of their increased sensitivity, ease of development, and concurrent miniaturization. The development of LFAs is an important contribution of nanotechnology in molecular diagnosis. Most of the EUA-authorized serological tests for COVID-19 are LFA-based. These devices help conduct serosurveys that show the disease's spread. Similarly, rapid antigen tests like the BinaxNOW, coupled with the smartphone app, help in rapid and POC detection (“Abbott's USD 5, 15-Minute BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card Becomes First Diagnostic Test with Read-Result Test Card to Receive FDA EUA - COVID-19 - Labmedica.com,” n.d.).

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of the COVID-19 diagnostic techniques.

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | High accuracy and sensitivity Qualitative confirmatory test Sequence-specific and used to identify variants Early diagnosis in asymptomatic cases |

Longer time for detection Laborious Costly Need infrastructure and trained individual |

| CT scan | Early screening for suspected individuals No sampling required Used for monitoring the infection An infection severity assessment could be performed |

Non-specific (No distinct differentiation from other pneumonia) Cannot distinguish among viral variants Requirement of expensive equipment and technician Risk of ionizing radiation |

| X-ray imaging | Affordable No sampling required Easily accessible Enables detection of other associated complications |

Non-specific False negatives (due to premature imaging/absence of pulmonary infection at the time of imaging) Require radiologist Multiple X-ray imaging may have a cumulative radiation effect |

| MRI | Used for monitoring infection It does not involve radiation Produces 3D images |

Costly Poor quality images Requirement of infrastructure and technician |

| Genome sequencing | Sensitive to identify the pathogen and its mutation rate Analyzes multiple samples in a single run Generated metadata may be used to develop other molecular biology assays, drugs, and vaccines It helps to understand near real-time dynamics of pandemic |

Laborious Costly Require pure and concentrated nucleic acids Require highly trained staff to analyze data |

| Microarray technique | Accurate Quantitative technique Less sample volume required Effective for variants detection |

Need pure and concentrated genetic material Relies on hybridization and washing events |

| CRISPR | Low cost It may be integrated with a smartphone High sensitivity |

Requires specific CRISPR sequences |

| LFIA | POC Qualitative Low cost It may be integrated with a smartphone |

Low sensitivity |

| ELISA | Qualitative/semi-quantitative Low cost Suitable for high throughput screening |

Low sensitivity |

| LAMP | Isothermal amplification Visible detection High selectivity and specificity RNA template may also be used along with DNA |

Require four primers Require expert technician |

| RCA | Rapid Compatible with both liquid and solid phase amplification Isothermal amplification |

Require costly primers Dependent on circular template |

| C2CA | Numerous amplified products were generated in a short time | Require expensive sequence-specific padlock probes, endonucleases, and ligases |

| Intelligence-based techniques | Automated detection Analysis using CT, X-ray, and ECG data |

Require large-scale metadata Needs specific algorithms |

| Nanodiagnostic techniques | POC High sensitivity and specificity Qualitative/semi-quantitative Low turnaround time Multiplexing |

Possible false negatives Challenging fabrication process |

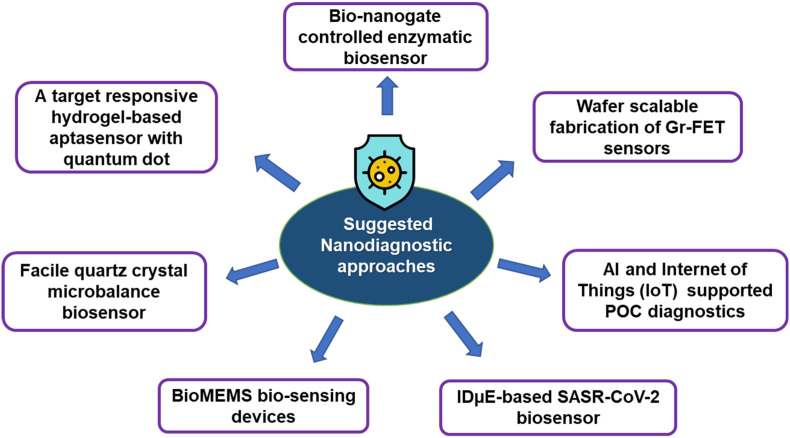

Continued research and innovation have contributed to developing promising biosensing techniques for COVID-19 diagnosis. There is an urgent need to scale up automation, improve sensitivity and specificity, and miniaturize the biosensing platforms to facilitate their use in POC settings. Multiplex assays, LOC devices, and smartphone-based technology are the future areas of expansion in nanodiagnostics. Although there is enormous progress in the development of nanodiagnostic methods, detecting and confirming the COVID-19 virus in asymptomatic cases remains a challenge for POC diagnostic techniques. Improvements in current diagnostic devices may serve the purpose of increasing sensitivity. The repurposing of previously developed biosensors, such as graphene-FET biosensors, quartz microbalance biosensors, QD-embedded hydrogel aptasensor, enzymatic biosensors, etc., for the development of sensitive COVID-19 diagnostic devices, has been proposed earlier (Xu et al., 2020). Possible integration of artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things (IoT) to develop biosensing devices for intelligent healthcare is also reported (Mujawar et al., 2020). They have also suggested using interdigitated microelectrodes (IDμE) and bio-microelectromechanical systems (BioMEMS)-based biosensing devices. Fig. 9 summarizes the proposed area of future innovation and development.

Fig. 9.

Suggested nanodiagnostic approaches for the management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Considering the critical nature of disease outbreaks like COVID-19, technological advancements are essential for the rapid diagnosis of infectious diseases. The rapidly evolving field of nanotechnology has the potential to develop more affordable and convenient biomedical devices that can help in the prevention and management of disease outbreaks and make significant improvements in the overall healthcare system.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mosam Preethi: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. Lavanika Roy: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. Sukanya Lahkar: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. Vivek Borse: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Dr. Vivek Borse reports financial support was provided by Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Vivek Borse would like to acknowledge the Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, for the INSPIRE Faculty Award (IFA18-ENG266, DST/INSPIRE/04/2018/000991).

List of Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- POC

Point-of-care

- 2019-nCoV

Novel coronavirus

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- WHO

World Health Organisation

- SARS-CoV-2

SARS coronavirus 2

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- N

Nucleocapsid

- M

Membrane

- E

Envelope

- S

Spike

- RBD

Receptor-binding domain

- ACE2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme II

- CRISPR-Cas

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated protein

- VOC

Variants of Concern

- VOI

Variants of Interest

- VUM

Variants under Monitoring

- NTD

N-terminal domain

- NAATs

Nucleic acid amplification tests

- LOC

Lab-on-chip

- IL

Interleukin

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- ORF

Open reading frame

- Hel

Helicase

- LOD

Limit of detection

- CT scan

Computerized tomography scan

- GGO

Ground-glass opacity

- CXR

Chest X-ray

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SISPA

Sequence-independent single primer amplification

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SPR

Surface plasmon resonance

- SHERLOCK

Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter UnLOCKing

- DETECTOR

DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter

- FELUDA

FNCAS 9 Editor Linked Uniform Detection Assay

- LFA

Lateral flow assay

- GFET

Graphene field effect transistor

- LFIA

Lateral flow immunoassay

- RT-RPA-LFA

Reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification lateral flow assay

- HC-FIA

Hybrid Capture Fluorescence Immunoassay

- AuNPs

Gold nanoparticles

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- CL-LFIA

chemiluminescent lateral flow immunoassay

- SpA

Staphylococcal protein A

- CMOS

Complementary metal-oxide semiconductor

- CCD

Charge-coupled device

- DNHCR

DNA scaffold hybrid chain reaction

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- MAb

Monoclonal antibody

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- TMB

3,3',5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine

- COF

Covalent organic framework

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- LAMP

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification

- RPA

Recombinase polymerase amplification

- RCA

Rolling circle amplification

- C2CA

Circle-to-circle amplification

- RT-LAMP

Reverse transcription-coupled LAMP

- EUA

Emergency use authorization

- iLACO

Isothermal LAMP-based colorimetric method

- PLAN-LFA

Padlock Rolling Circle Amplification Nuclease Protection Lateral Flow Assay

- HC2CA

Homogenous circle-to-circle amplification

- DL

Deep learning

- ML

Machine learning

- CNN

Convolutional neural network

- ZFNet

Zeiler and Fergus network

- DenseNet 121

Dense convolutional network-121

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- NBS

Nanoparticle-based biosensor

- FTO

Fluorine-doped tin oxide

- SPCE

Screen-printed carbon electrode

- PPT

Plasmonic photothermal

- LSPR

Localized surface plasmon resonance

- GC-FP

Grating-coupled fluorescent plasmonics

- LSPCF

Localized surface plasmon coupled fluorescence

- ASOs

Antisense oligonucleotides

- FET

Field-effect transistor

- PMO

Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligos

- ECL

Electrochemiluminescence

- Zr QDs

Zirconium quantum dots

- IBV

Infectious bronchitis virus

- In2O3

Indium (III) oxide

- LNPs

Lanthanide-doped polystyrene nanoparticle

- SERS

Surface-enhanced Raman Spectroscopy

- ICT

Immunochromatographic test

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IoT

Internet of Things

- IDμE

Interdigitated microelectrodes

- BioMEMS

Bio-microelectromechanical systems

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- #IndiaFightsCorona COVID-19 in India, Vaccination, dashboard, Corona virus tracker | mygov.in [WWW document], n.d. URL https://www.mygov.in/covid-19 (accessed 10.14.2022).

- Abbott’s USD 5 15–Minute BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag card Becomes first diagnostic test with read-result test card to receive FDA EUA - COVID-19-labmedica.com [WWW document] https://www.labmedica.com/covid-19/articles/294784209/abbotts-usd-5-15-minute-binaxnow-covid-19-ag-card-becomes-first-diagnostic-test-with-read-result-test-card-to-receive-fda-eua.html n.d. URL.

- Abdollahi I., Nabahati M., Javanian M., Shirafkan H., Mehraeen R. Can initial chest CT scan predict status and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 infection? A retrospective cohort study. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021;52:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s43055-021-00538-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ACON, n.d. SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Package Insert, Fda.

- ADEXUSDx COVID-19 Test Instructions for use [WWW document] https://www.fda.gov/media/149441/download n.d.. Fda. URL.

- ADVAITE, n.d. “RapCov rapid COVID-19 test" [WWW document]. FDA. URL https://www.fda.gov/media/145080/download (accessed 5.22.2022).

- Ahmed S.R., Kang S.W., Oh S., Lee J., Neethirajan S. Chiral zirconium quantum dots: a new class of nanocrystals for optical detection of coronavirus. Heliyon. 2018;4 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., Zhan C., Chen C., Lv W., Tao Q., Sun Z., Xia L. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296:E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alafeef M., Dighe K., Moitra P., Pan D. Rapid, ultrasensitive, and quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 using antisense oligonucleotides directed electrochemical biosensor chip. ACS Nano. 2020;14:17028–17045. doi: 10.1021/ACSNANO.0C06392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assure Rapid . Fda; 2020. Test Device [WWW Document]https://www.fda.gov/media/139789/download URL. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M., Phutela R., Ansari A.H., Sinha D., Sharma N., Kumar M., Aich M., Sharma S., Rauthan R., Singhal K., Lad H., Patra P.K., Makharia G., Chandak G.R., Chakraborty D., Maiti S. Rapid, field-deployable nucleobase detection and identification using FnCas9. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.028167. 2020.04.07. 028167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann O., Bachmann I., Spiegel M., Schramm M., Abd El Wahed A., Dobler G., Dame G., Hufert F.T. Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 by low volume real-time single tube reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification using an exo probe with an internally linked quencher (Exo-IQ) Clin. Chem. 2020;66:1047–1054. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BinaxNOWTM COVID-19 Ag CARD [WWW document] https://www.fda.gov/media/141570/download n.d. URL.

- Biohit Antibody . Fda; 2020. Test [WWW Document]https://www.fda.gov/media/139280/download [Google Scholar]

- BIOTIME Rapid . Fda; 2020. Test [WWW Document]https://www.fda.gov/media/140440/download URL. [Google Scholar]

- Borse V., Srivastava R. Process parameter optimization for lateral flow immunosensing. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2019;2:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.mset.2019.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borse V., Srivastava R. Nanobiomaterial Engineering. Springer Singapore. 2020. Nanobiotechnology advancements in lateral flow immunodiagnostics. Singapore 181–204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borse V., Pawar V., Shetty G., Mullaji A., Srivastava R. Nanobiotechnology perspectives on prevention and treatment of ortho-paedic implant associated infection. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2016;13:175–185. doi: 10.2174/1567201812666150812141849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borse V.B., Konwar A.N., Jayant R.D., Patil P.O. Perspectives of characterization and bioconjugation of gold nanoparticles and their application in lateral flow immunosensing. Drug deliv. Transl. Res. 2020;10:878–902. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00771-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borse V.B., Konwar A.N., Srivastava R. Handbook on Miniaturization in Analytical Chemistry. Elsevier; 2020. Nanobiotechnology approaches for miniaturized diagnostics; pp. 297–333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borse V., Chandra P., Srivastava R., editors. BioSensing, Theranostics, and Medical Devices, BioSensing, Theranostics, and Medical Devices. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton J.P., Deng X., Yu G., Fasching C.L., Singh J., Streithorst J., Granados A., Sotomayor-Gonzalez A., Zorn K., Gopez A., Hsu E., Gu W., Miller S., Pan C.-Y., Guevara H., Wadford D.A., Chen J.S., Chiu C.Y. Rapid detection of 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 using a CRISPR-based DETECTR lateral flow assay. medRxiv Prepr. Serv. Heal. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.06.20032334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch R., Urban G.A., Dincer C. Unamplified gene sensing via Cas9 on graphene. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:419–420. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady N.C., Tokranova N., Minor A., Nikvand N., Strle K., Lee W.T., Page W., Guignon E., Pilar A., Gibson G.N. Multiplexed detection and quantification of human antibody response to COVID-19 infection using a plasmon enhanced biosensor platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;171:112679. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CareStartTM COVID-19 antigen test kit using NanoActTM launched in the U.S. | BioSpace [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/carestart-covid-19-antigen-test-kit-using-nanoact-launched-in-the-u-s-/(accessed 5.21.2022).

- CareStart . Fda; 2021. COVID-19 IgM/IgG test [WWW document]https://www.fda.gov/media/140444/download URL. [Google Scholar]

- CareStart Antigen Test [WWW document] https://www.fda.gov/media/142916/download n.d. URL.

- Carter L.J., Garner L.V., Smoot J.W., Li Y., Zhou Q., Saveson C.J., Sasso J.M., Gregg A.C., Soares D.J., Beskid T.R., Jervey S.R., Liu C. Assay techniques and test development for COVID-19 diagnosis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6:591–605. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catal Reis H. COVID-19 diagnosis with deep learning. Ing. e Investig. 2021;42:e88825. doi: 10.15446/ing.investig.v42n1.88825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.W., Yip C.C.Y., To K.K.W., Tang T.H.C., Wong S.C.Y., Leung K.H., Fung A.Y.F., Ng A.C.K., Zou Z., Tsoi H.W., Choi G.K.Y., Tam A.R., Cheng V.C.C., Chan K.H., Tsan O.T.Y., Yuen K.Y. Improved molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 by the novel, highly sensitive and specific COVID-19-RdRp/hel real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay validated in vitro and with clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00310-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Zhang Z., Zhai X., Li Y., Lin L., Zhao H., Bian L., Li P., Yu L., Wu Y., Lin G. Rapid and sensitive detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG, using lanthanide-doped nanoparticles-based lateral flow immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2020;92:7226–7231. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D.K.W., Pan Y., Cheng S.M.S., Hui K.P.Y., Krishnan P., Liu Y., Ng D.Y.M., Wan C.K.C., Yang P., Wang Q., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Molecular diagnosis of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) causing an outbreak of pneumonia. Clin. Chem. 2020;66:549–555. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson P., Fournier P., Delerce J., Million M., Bedotto M., Houhamdi L., Yahi N., Bayette J., Levasseur A., Fantini J., Raoult D., La Scola B. Culture and identification of a “deltamicron” SARS-CoV-2 in a three cases cluster in southern France. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:3739–3749. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman, V.M., Landt, O., Kaiser, M., Molenkamp, R., Meijer, A., Chu, D.K., Bleicker, T., Brünink, S., Schneider, J., Schmidt, M.L., Mulders, D.G., Haagmans, B.L., van der Veer, B., van den Brink, S., Wijsman, L., Goderski, G., Romette, J.-L., Ellis, J., Zambon, M., Peiris, M., Goossens, H., Reusken, C., Koopmans, M.P., Drosten, C., 2020. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 25, 2000045. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coronaviridae . ICTV [WWW Document]; 2011. Positive Sense RNA Viruses - Positive Sense RNA Viruses.https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_9th_report/positive-sense-rna-viruses-2011/w/posrna_viruses/222/coronaviridae n.d. URL. [Google Scholar]

- CovAb SARS-CoV-2 ab test [WWW document], n.d.. Fda. URL https://www.fda.gov/media/149943/download (accessed 5.21.2022).

- COVID-19 PathogenDx | DNA based pathogen [WWW document] https://pathogendx.com/covid-19/ n.d. URL.

- COVID-19 Rapid Test Casette [WWW Document] 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/138435/download Fda. URL. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, F., Zhou, H.S., 2020. Diagnostic methods and potential portable biosensors for coronavirus disease 2019. Biosens. Bioelectron.. 165, 112349. doi:10.1016/J.BIOS.2020.112349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curti L., Pereyra-Bonnet F., Gimenez C.A. An ultrasensitive, rapid, and portable coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 sequence detection method based on CRISPR-cas12. bioRxiv. 2020:971127. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.29.971127. 2020.02.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damborský P., Švitel J., Katrlík J. Optical biosensors. Essays Biochem. 2016;60:91–100. doi: 10.1042/EBC20150010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels J.S., Pourmand N. Label-free impedance biosensors: opportunities and challenges. Electroanalysis. 2007;19:1239–1257. doi: 10.1002/elan.200603855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. Scientists identify new COVID variant called ‘deltacron’ [WWW document] n.d. WebMD. URL https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20220311/new-covid-variant-deltacron.

- European Commission COVID-19 in vitro diagnostic medical device - detail | COVID-19 in vitro diagnostic devices and test methods database [WWW document] Eur. Community. 2022 https://covid-19-diagnostics.jrc.ec.europa.eu/devices/detail/5 URL. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiani, L., Mazzaracchio, V., Moscone, D., Fillo, S., De Santis, R., Monte, A., Amatore, D., Lista, F., Arduini, F., 2022. Paper-Based immunoassay based on 96-well wax-printed paper plate combined with magnetic beads and colorimetric smartphone-assisted measure for reliable detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva. Biosens. Bioelectron. 200, 113909. doi:10.1016/J.BIOS.2021.113909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fang Y., Zhang H., Xie J., Lin M., Ying L., Pang P., Ji W. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020;296:E115–E117. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA . Fda; 2020. EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance [WWW Document]https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance URL. [Google Scholar]

- For use under Emergency . Fda; 2021. Use Authorization Only for in Vitro Diagnostic Use Only for Prescription Use Only EZ COVID-19 IgM/IgG Package Insert (Instructions for Use) [WWW Document]https://www.fda.gov/media/150425/download URL. [Google Scholar]

- Funari R., Chu K.Y., Shen A.Q. Detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by gold nanospikes in an opto-microfluidic chip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;169 doi: 10.1016/J.BIOS.2020.112578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W., Ni, Z., Hu, Yu, Liang, W.-H., Ou, C., He, J., Liu, L., Shan, H., Lei, C., Hui, D.S.C., Du, B., Li, L.-J., Zeng, G., Yuen, K.-Y., Chen, R.-C., Tang, C., Wang, T., Chen, P.-Y., Xiang, J., Li, S.-Y., Wang, J.-L., Liang, Z., Peng, Y.-X., Wei, L., Liu, Y., Hu, Ya-hua, Peng, P., Wang, J., Liu, J., Chen, Z., Li, G., Zheng, Z., Qiu, S., Luo, J., Ye, C., Zhu, S., Zhong, N., China medical treatment expert group for covid-19, 2020. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1708–1720. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guo X., Geng P., Wang Q., Cao B., Liu B. Development of a single nucleotide polymorphism DNA microarray for the detection and genotyping of the SARS coronavirus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;24:1445–1454. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1404.04024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Gálvez L., del Caño R., Menéndez-Luque I., García-Nieto D., Rodríguez-Peña M., Luna M., Pineda T., Pariente F., García-Mendiola T., Lorenzo E. Electrochemiluminescent nanostructured DNA biosensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Talanta. 2022;240 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2021.123203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajian R., Balderston S., Tran T., deBoer T., Etienne J., Sandhu M., Wauford N.A., Chung J.Y., Nokes J., Athaiya M., Paredes J., Peytavi R., Goldsmith B., Murthy N., Conboy I.M., Aran K. Detection of unamplified target genes via CRISPR–cas9 immobilized on a graphene field-effect transistor. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:427–437. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0371-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]