Abstract

An individual bout of eating involves cues to start eating, as well as cues to terminate eating. One process that determines initiation of eating is food reinforcement. Foods with high reinforcing value are also likely to be consumed in greater quantities. Research suggests both cross-sectional and prospective relationships between food reinforcement and obesity, food reinforcement is positively related to energy intake, and energy intake mediates the relationship between food reinforcement and obesity. A process related to cessation of eating is habituation. Habituation is a general behavioral process that describes a reduction in physiological or affective response to a stimulus, or a reduction in the behavioral responding to obtain a stimulus. Repeated exposure to the same food during a meal can result in habituation to that food and a reduction in consumption. Habituation is also cross-sectionally and prospectively related to body weight, as people who habituate slower consume more in a meal and are more overweight. Research from our laboratory has shown that these two processes independently influence eating, as they can account for almost 60% of the variance in ad libitum intake. In addition, habituation phenotypes show reliable relationships with reinforcing value, such that people who habituate faster also find food less reinforcing. Developing a better understanding of cues to start and stop eating is fundamental to understanding how to modify eating behavior. An overview of research on food reinforcement, habituation and food intake for people with a range of weight status and without eating disorders is provided, and ideas about integrating these two processes that are related to initiation and termination of a bout of eating are discussed.

Keywords: Food reinforcement, Habituation, Eating, Energy intake, Obesity

Eating involves initiation processes, as well as processes related to the cessation of eating. The frequency and intensity of eating initiation and timing of cessation contribute to total energy intake [1]. Reinforcement learning is a process that shapes the types of foods that people choose to eat, strengthens the act of consuming those foods, and primes the desire to consume those foods [2]. Experience and development of food reinforcers are processes relevant to the initiation of eating. Habituation represents a process in which physiological responses to repeated food stimuli, or behavioral responses to obtain food, are reduced [3]. Habituation is important for the cessation of an eating bout, with the cessation process often labeled satiation. Our research suggests that reinforcement and habituation processes contribute to the initiation and termination of an eating bout, and thus the amount of food consumed during a meal or snack [3, 4]. We first review research on food reinforcement and habituation to food, focusing on factors that moderate their relationship with eating and energy intake. We then discuss how these two factors can complement each other to determine food intake in people with and without obesity and without eating disorders. Ideas for future research are integrated in this discussion.

1. Food reinforcement and the initiation of eating

1.1. Measuring food reinforcement

Food is a powerful primary reinforcer, which means that people do not have to learn that food is reinforcing [5]. Reinforcers are stimuli that maintain (i.e. reinforce or strengthen) behavior, and the reinforcing value of food can be determined by how much work someone will do for access a given food [4]. The classical way to measure reinforcer value is to provide reinforcers on a progressive ratio schedule and examine the highest ratio completed, in the same way that reinforcing value of drugs of abuse are measured [6, 7]. Higher ratio schedules for drugs indicate both greater abuse liability and higher reinforcing value. Likewise, the more someone will work for access to food, the higher the reinforcing value of that food. This paradigm has been used to measure the reinforcing value of food across a variety of populations [4, 8 - 11].

The absolute reinforcing value of a food can be assessed by providing one food within the reinforcing value task. It is possible to compare absolute reinforcing value across a wide variety of foods. It is also possible to study the relative reinforcing value of food, in which people are provided several food or non-food options simultaneously, and have to make a choice about how to allocate their responses. The concurrent choice paradigm is a better analog to eating in the natural environment, as people are seldom provided only one option to eat, but have choices about whether to eat or not to eat, and what and how much to eat. The relative reinforcing value of a food depends on the reinforcing value of the food as well as the reinforcing value of alternatives available, whether the alternative is a different food, or a non-food activity. A questionnaire to assess absolute or relative reinforcing value of food has been developed, which asks people how many progressively increasing responses they would do to get food. The behavioral economic demand for food can also be measured, which asks people how much of a food they would purchase for varied prices. This allows for the creation of a demand curve, by examining choices at a variety of prices. This allows for a number of different metrics, including intensity, which is how much food someone would eat if it was free, and elasticity, the relationship between changes in price and changes in purchasing.

1.2. Learning and food reinforcement

Individual differences in food reinforcement begin at an early age. We have shown individual differences in the relative reinforcing value of food in infants [12, 13], and this research has continued through pre-school children [14, 15], pre-adolescents [29], adolescents [32], and adults [4]. As people consume different types of food, they learn what foods they find pleasant and form preferences in terms of the sensory qualities of food, such as smell, taste, visual appeal, and mouthfeel. In addition, biological changes that occur during and after food consumption that involve neuroendocrine responses and activation of brain reward centers strengthen eating that food again [16, 17]. When people consume foods that activate brain reward pathways, the act of eating those foods is strengthened [16, 18, 19]. Research has shown that the reinforcing value of a food is related to dopamine release that accompanies intake of that food, but due to conditioning processes, over time dopamine release shifts to stimuli associated with intake of those foods, which can lead to the desire to eat those foods [16, 19].

Repeated consumption of a food paired with specific cues can create an association between the food and cue. Repeated pairing of food and cues can lead to a learned association with cues, such as sight, smell, or stimuli associated with food availability that then stimulate a desire to eat that food [20]. Conditioned cues can stimulate eating even when sated [21]. The presentation of cues paired with eating palatable or highly reinforcing foods can lead to craving and consumption of those foods [22 - 24]. As cues become conditioned to the act of eating, and guide people on what to eat, research has shown that people with obesity have stronger anticipatory responses to food, which may act as a driving stimulus for initiation of eating [25, 26].

The development of food reinforcement and cues that signal eating involve the combination of instrumental and classical conditioning. Appetitive Pavlovian instrumental transfer provides a theoretical basis for integrating instrumental and classical conditioning, which can cue people on what to eat, as well as increase motivation to obtain a specific food [27].

1.3. Food reinforcement, food intake and obesity

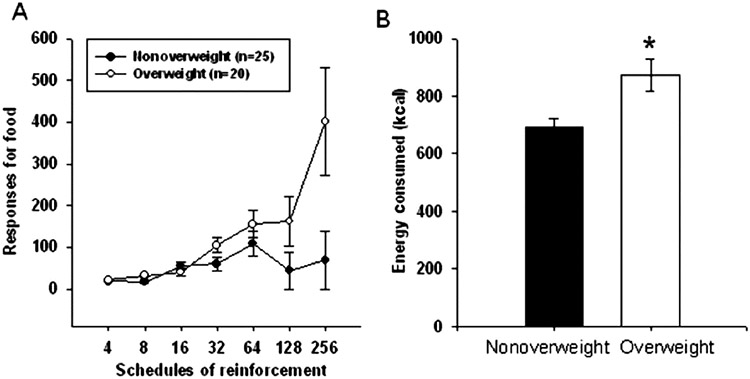

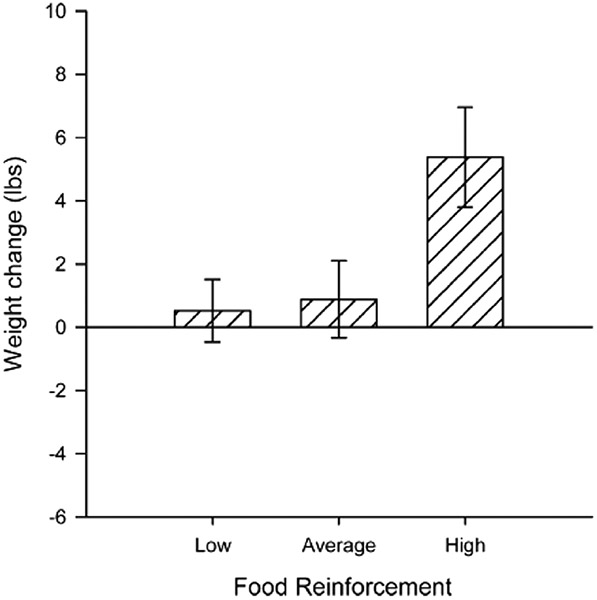

The reinforcing value of food is positively related to energy consumption, as people who find food more reinforcing eat more calories [4, 28 - 30]. Not surprisingly, the reinforcing value of food is cross-sectionally and prospectively related to obesity in children [29, 31], adolescents [32], and adults [4, 33]. As shown in Fig. 1, 8–12 year-old children with obesity find food more reinforcing and will work harder for food than peers with a healthy weight [29]. In addition, as shown in a sample of 115 adults without obesity in Fig. 2, those with greater food reinforcement gain more weight [32, 33]. The relationship between the reinforcing value of food and obesity is mediated by energy intake [34], suggesting that high food reinforcement leads to excess weight through positive energy balance and excess food intake.

Fig. 1.

A. Number of responses at each schedule of reinforcement in non-overweight (< 75th BMI percentile; n = 25) and overweight (≥ 90th BMI percentile; n = 20) children. Children with higher BMI percentile responded significantly more for food as the reinforcement schedules progressed.

B. Mean (±SEM) energy consumed in the laboratory in non-overweight and overweight children. From “Overweight children find food more reinforcing and consume more energy than do nonoverweight children” by J. L. Temple, C. M. Legierski, A. M. Giacomelli, S. J. Salvy and L. H. Epstein, 2008, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87, 1121–1127. Copyright 2008 by American Society for Nutrition.

Fig. 2.

Weight change over 12 months (mean ± SEM) by relative reinforcing value of food. Individuals with high relative food reinforcement (proportion responses for food versus total responding; ≥0.75) gained significantly more weight than average food reinforcement (≥ 0.33, < 0.75) and low food reinforcement (< 0.33). From “Food reinforcement, dietary disinhibition and weight gain in nonobese adults” by K. A. Carr, H. Lin, K. D. Fletcher and L. H. Epstein, 2014, Obesity, 22, 254–259. Copyright 2013 by The Obesity Society.

As noted above, the relative reinforcing value of food assesses the choice between different types of food or eating and an alternative behavior. In infants, the relative reinforcing value of food is greater for infants with overweight than lean, and this is due to the differences in the reinforcing value of the alternatives to food, not to food itself [13]. The implication is that differences in energy intake in infants may be driven by their motivation for non-food alternative reinforcers. Animal research has shown an enriched environment that includes alternative reinforcers can lead to a reduction in drug use or food consumption in comparison to sparser environments [170]. In addition, children who grow up in environments with greater access to cognitively enhancing activities, including access to reading and music, are at lower risk for obesity later in childhood or adulthood [171]. For older children, those with overweight find food more reinforcing than non-food alternatives, while children without overweight find non-food alternatives more reinforcing than food [29]. In addition, cognitively enriching and social activities can reduce the reinforcing value of food [35]. Finally, access to a greater proportion of non-food pleasurable activities is associated with greater weight loss in a behavioral weight loss program [36]. These data point to the idea that availability and experience with both alternatives and food are important to determining the reinforcing value of food

1.3.1. Short and long-term effects of hunger/food deprivation on food reinforcement

Food deprivation is a mainstay of experimental psychology as a way to create a strong reinforcer to train animal behavior for experimental studies [37, 38]. Food deprivation is characteristic of a diet and increases the reinforcing value of food in the short term [4, 39]. Short-term deprivation can last for at least one week, as Flack and associates [40] showed increases in the relative reinforcing value of sweet foods after one week of sweet food restriction.

Based on the idea that hunger can be a cue for eating, Gibson and Desmond found that pairing chocolate intake with hunger rather than fullness increasing craving, hedonics and anticipated intake for chocolate post training [41], but this effect did not replicate to fruit bars [42]. Important differences between the studies, including 50% fewer pairings of hunger with fruit bar intake, as well as differences in the energy content of the snacks, may have contributed to the results. Given the reliable short-term effects of food deprivation on reinforcing value of food and craving [43], an interesting idea would be whether varying degrees of deprivation can be used to increase the reinforcing value of healthy foods.

Studies conducted over longer time intervals, however, suggest a diet's caloric intake restriction produces a different pattern of food reinforcement. Goldfield and colleagues [44] have shown that after eight weeks of calorie restricted diet in adults, the reinforcing value of snack foods were unchanged. Other research has shown that food reinforcement can decrease in a weight control program [36]. Individual differences in changes in reinforcing value of food influenced weight loss, with greater decreases in food reinforcement being associated with greater long-term weight reduction (up to 18-month follow-up) [36].

1.3.2. Craving, attentional bias, disinhibition and reinforcement pathology

As noted above, the increased desire to eat when presented with stimuli associated with palatable foods is part of the process of developing food reinforcers. This increased desire for food, in particular to anticipatory cues, is often conceptualized as food craving [25, 26]. Comprehensive reviews of the literature have shown enhanced craving for food during the initial stages of a weight control program, but reliable reductions in craving for food over time, including cravings for palatable sweet, high fat and fast foods [43, 45, 46]. Likewise, a review of various ways to conceptualize food reward, including hedonics, subjective implicit or explicit wanting of food, or overall food palatability, has shown reliable reductions during weight control programs over time [47]. Finally, investigators have compared brain activation during a task in which adults worked for palatable food between people with successful versus unsuccessful weight maintenance over 6 months [48]. Results showed successful weight maintenance was associated with a reduction in activation of brain reward centers during the food-related reward task. In sum, these results suggest that changes in the reinforcing value of food, as well as related constructs such as food hedonics and brain reward responses to food can be observed after successful weight control. Of course, the failure to show a reduction in behaviors associated with eating is associated with poor long-term weight maintenance [36]. An important challenge for future research is to identify optimal methods to reduce the reinforcing value of energy dense foods while people simultaneously experience food deprivation through reducing energy intake and a reduction in their intake of favorite foods.

Another aspect of food deprivation or increasing hunger is that it shifts attentional bias to food [49, 50], which is logical since hunger resulting from food deprivation is an important motivation to eat. It is interesting that people who habitually consume specific foods, such as chocolate, or who are induced to crave chocolate, show attentional bias toward chocolate [51]. We [52] have shown that the relationship between attentional bias toward favorite foods and reinforcing value of those foods is moderated by working memory capacity, with the strongest relationships between attention bias and reinforcing value being for people with lower working memory. Impulsivity may moderate the effects of having obesity on attentional bias to food cues [53]. Exteroceptive or interoceptive cues associated with hunger can be occasion setters for learned behavior, including craving for food [22 - 24]. Schepers and Bouton [54] have shown in basic animal experiments that cues associated with hunger or satiety can be contextual cues for eating, pointing to the importance of contextual cues for motivating eating, just as contextual cues are important for extinction of eating [55, 56].

Food reinforcement may be related to psychological constructs such as disinhibition, as those high on disinhibition find food more reinforcing [33, 57]. Nederkoorn and colleagues showed that children with obesity reported more reward sensitivity and impulsivity than leaner peers, and this greater impulsivity can lead to excess energy intake [58]. In addition, impulsive choices, as indexed by delay discounting, has been examined in combination with reinforcing value of food, formulating reinforcement pathology theory. Reinforcer pathology relates the powerful reinforcing effects of food (or drugs) with poor impulse control to understand excess food or drug consumption [59 - 62]. People who are high in food reinforcement, have a brief temporal window for decision making and discount the future, consume more food in a laboratory environment [63], have more obesity [64], and lose less weight in a behavioral weight control program [65]. Reinforcer pathology theory relates reinforcing value to the temporal window of people's choices. Theoretically, if a person has a brief temporal window, they will seek immediate reinforcers, and food or drugs provide reliable and immediate reinforcement [66]. On the other hand, if the person has an extended temporal window, they can tolerate waiting and work to obtain more powerful but delayed reinforcers, such as cognitively enriching activities or important social interactions that yield many benefits, but require work or practice and are not immediately reinforcing [66]. Reinforcer pathology theory also hypothesizes that the effects of alternative reinforcers will depend in part on the temporal window, since immediate reinforcers are chosen because they consistently provide immediate satisfaction, while the value of alternative reinforcers may not always be immediate.

1.4. Extinction based treatments to reduce food cravings and reactivity to foods

One theoretical explanation for the reduction in craving and food reinforcement with sustained avoidance of eating these foods is extinction [45]. Extinction may occur as the associative learning between food cues craving, food reinforcement and food consumption is broken as people repeatedly experience the cues and craving without the rewarding consequence of eating. Research has shown reliable effects of food cue exposure and food cue exposure plus response prevention based on extinction theory to reduce food cravings, food reactivity and food consumption in persons who are overweight or overeat [67 - 73]. Given the relationship between food cravings and food reinforcement noted above, it is reasonable to question whether one of the mechanisms in these exposure studies was to reduce the reinforcing value of those foods. Theoretically extinction would also account for the temporary increase in craving when palatable foods are restricted, as there is an extinction burst, or an increase in motivated behaviors, at the beginning of the extinction period before a decrease is observed [74]. In addition, Bouton has shown that extinction does not result in removal or destruction of the originally learned responses, but rather new learning of inhibitory cues that are context dependent, such that restoration to the original context, or exposure to a new context different from the extinction context can result in restatement of the eating behavior [55, 56]. The failure to generalize extinction to multiple contexts may be important for long-term extinction based control of eating.

A second explanation for the reduction in food reinforcement is that after removal of a powerful reinforcer such as food, people may substitute other reinforcers. As noted above, eating is a choice among behaviors, and a solid body of research suggests that food can be less reinforcing if there is reliable access to alternative reinforcers to food [75]. These two theoretical approaches are not exclusive, in fact they may complement each other. As the reinforcing value of food decreases during extinction, the relative value of other reinforcers, including healthier foods as well as non-food reinforcers, can increase as people experience more of those behaviors, as well as due to behavioral contrast. Behavioral contrast refers to a change in the reinforcing value of one behavior when the rate of reinforcement for a second behavior is reduced [74, 76]. By definition, extinction involves the reduction in reinforcement for a particular food, which according to behavioral contrast would result in an increase in the reinforcing value of an alternative, even if the alternative was less reinforcing before extinction. In summary, food deprivation, a characteristic of diets, increases food reinforcement, craving and food hedonics in the short term, but extinction procedures as well as longer term deprivation can reduce food reinforcement, food craving and food hedonics. An important area of research is the identification of the best way to reduce the reinforcing value of high-energy dense foods as they reduce energy intake to help people lose weight and maintain weight loss.

1.4.1. Characteristics of food and reinforcing value of food

Most people have strong personal food preferences. A consistent body of animal research has shown that sugar is an important characteristic of food that drives many aspects of eating [77, 78], including increased food reinforcement [28, 79, 80]. Repeated sugar intake is associated with dopamine increases in the nucleus accumbens [81], consistent with drugs of abuse [82]. Animal studies have shown that persistent sugar consumption can also lead to cross-sensitization, or an increase in reinforcing value of other reinforcers, including drug reinforcers [83, 84]. Brain reward center dopamine release is initially associated with consumption of sugar but, over repeated bouts, dopamine release shifts to anticipation of sugar consumption, which is related to creation of sugar cravings [82]. While general food deprivation can increase short-term food reinforcement, reduction in sugar intake selectively increases the short-term reinforcing value of sugar [40]. Sugar, as well as many high carbohydrate foods also have a high glycemic index, which can have a similar effect on reward processes as sugar [85 - 87]. High glycemic index of these foods may be associated with similar challenges to reducing sugar [40].

In addition to sugar, dietary fat is also reinforcing [88, 89]. Intake of dietary fat can result in increases in brain dopamine levels [90, 91], as well as increases in opioid responding [91, 92]. Many foods also are composed of both fat and sugar, which can be reinforcing [91], and may be a particularly powerful combination that drives eating [86, 93 - 97]. Fat is considered a sixth taste modality [98], and fat can amplify flavor perception [99], which may be related to an increased reinforcing value foods that pair fat with other characteristics of foods, such as sugar or salt. Research with children suggests that foods high in fat and high in sugar can serve as reinforcers, with the relationships related to usual consumption of sugar and fat in the diet [89]. Research also suggests greater activation of brain reward (hedonic) pathways for high fat/high carbohydrate foods than either high fat or high carbohydrate foods [94].

An interesting approach to studying individual differences in food reinforcement for high sugar or high fat foods is to study taste thresholds. Orosensory components of eating are important for food intake and food selection [100]. Sensory thresholds may differ based on body weight and a history of intake of specific foods [101, 102]. Research suggests that perception of fat and sugar are related to reinforcing value of fat and sugar [103]. As thresholds for fat or sugar increased, indicating individual differences in perception, the reinforcing value of foods high in fat or sugar were increased. As perceptions can be learned [104], future research is needed to identify the mechanisms that relate perceptual thresholds to food reinforcement.

In summary, our understanding of food characteristics that increase their reinforcing value is in the early stages. While there are likely to be large individual differences in what types of foods an individual finds to be reinforcing, the search for common factors that drive food reinforcement, such as sugar or fat, may improve our understanding of what characteristics of foods are most relevant to consider if the goal is to reduce food reinforcement and improve healthy eating. It is also possible that reinforcing value of food, like food preference, is highly idiosyncratic to the person based on their unique physiology and learning history. Based on the research reviewed, there are many areas for research. We suggest several interesting new areas of research.

Can food deprivation increase the reinforcing value of healthy foods? A popular current dietary approach for weight loss and improved sleep is time restricted feeding, in which people limit their intake to 8 or 10 h [105]. One approach to time-restricted feeding is to eat only in an 8-hour window, for example noon to 8 pm. This creates 16 h of food deprivation prior to eating. An open question includes how breaking the fast with healthy foods influences food reinforcement. Is it possible that if low energy-dense foods, such as salads, were the foods that reliable were used as the first meal to break the fast, would increase the reinforcing value of salads? Timberlake [106] presented a disequilibrium theory that summarizes research to show that a behavior can be increased if it is deprived, even if the pre-deprivation response rate is low. Gibson has evaluated the effect of eating while hungry for chocolate and fruits [41]. This research would suggest that deprivation can increase reinforcing value of a reinforcer satisfying the deprivation, even if the food is initially not a favorite food.

What leads people to develop a high reinforcing value of healthy foods? While the majority of the population have shown an increase in obesity and unhealthy eating, there is a minority who maintain a healthy weight and choose healthy foods. It would be interesting to understand what leads people to seek out healthy foods and presumably to find salads and vegetables reinforcing. It may also be worth studying people who have chosen low-carbohydrate, low glycemic index foods, who have drastically reduced their intake of high glycemic index foods, shifting to greater intake of fats.

Will there be changes in reinforcing value of high-sugar or high-fat foods if one is restricted? Adults may have a preference for either high-fat or high-sugar foods [107]. If their preferred foods were restricted, it would be interesting to understand if preferences and reinforcing value for the other flavor profile changed, which could be evidence of behavioral contrast.

2. Habituation to food and the cessation of eating

Habituation is a general process that describes how repeated sensory stimulation influences subsequent physiological responding to that stimulus or behavioral responding to obtain that stimulus [108, 109]. When someone habituates to a stimulus they show a reduced neural, physiological, behavioral and/or subjective/emotional response to that stimulus. Habituation is ubiquitous across a wide variety of neural, physiological, behavioral and emotional or subjective responses [108]. An eating bout consists of people repeatedly experiencing olfactory and gustatory food cues which can lead to habituation to those food cues, and cessation of a meal [3]. The intensity of the stimulus, as well as the rate at which the stimulus is presented can influence habituation, with faster habituation for more intense stimuli [110], and more rapid habituation for stimuli presented after shorter inter-stimulus intervals [111]. A reduction in response to a repeated stimulus by itself is not an indication of habituation, as this can occur due to diminished ability of sensory receptors to encode stimuli or effectors that are responsible for responding to a stimulus after repeated presentations. In addition, extinction after repeated presentation of a stimulus or satiation to that food are other potential explanations for response decrement.

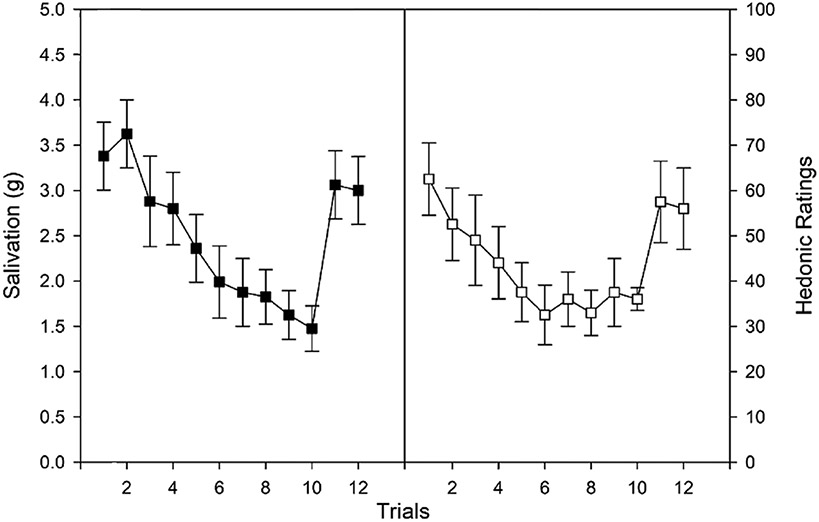

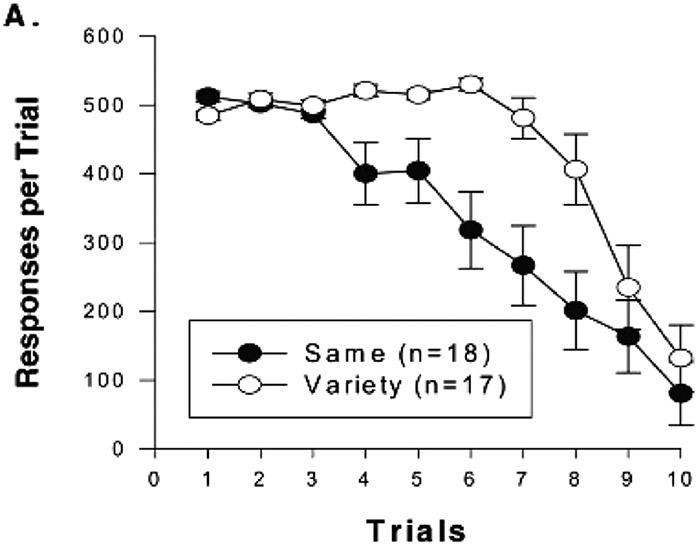

Rankin et al. [110], outlines the necessary elements constituting habituation, and, in food research, three major paradigms have been used to establish habituation [3]. First, habituation is observed if, when a novel dishabituating stimulus is presented, recovery of responding to the initial habituated stimulus occurs. This is shown in Fig. 3, where adults showed habituation of the salivary response to repeated presentation of lemon juice [112]. Lime juice was then presented as a dishabituator, and responding to lemon juice was recovered. Response recovery was not dependent on stimulation of the salivary response, as bitter chocolate and stress [112] also recovered responding to lemon juice, even though neither stimulates salivation. Second, in studies of habituation of behavioral responding for food, novel food stimuli also acted as dishabituators and resulted in recovery of responding [112]. Faster habituation due to shorter interstimulus intervals also results in faster recovery [110]. Third, a variety of stimuli, rather than one repeated stimulus, can be presented which leads to differential rates of reduction in behavior, with faster reduction for repeated presentation of one stimulus than a variety of stimuli [114]. This is illustrated in Fig. 4, which shows for a sample of 37 8–12 year-old children without obesity slowed habituation when a variety of foods are presented, rather than one food, even if that food is the person's favorite food [3, 115]. Habituation is not simply sensory, effector or motor fatigue, as an habituated response can be dishabituated with presentation of a novel stimulus, and habituation is not due to satiety, as people will dishabituate responding and consume more food after presentation of a novel stimulus, even after they report being full. While hunger and food deprivation modify food reinforcement, studies haven't shown an effect of deprivation on habituation [1].

Fig. 3.

Salivation and hedonics (mean ±SEM) for subjects receiving lemon or lime juice as the habituating stimulus in trials 1 – 10 and the opposite stimulus as dishabituator in trial 11, with re-presentation of the original habituating stimulus in trial 12. From “Habituation and dishabituation of human salivary response” by L. H. Epstein, J. S. Rodefer, L. Wisniewski and A. R. Caggiula, 1992, Physiology & Behavior, 51, 945–950. Copyright 1992 by Pergamon Press Ltd.

Fig. 4.

Mean ± SEM responding in each trial for access to food. Children served the same food habituated at a faster rate than those working for a variety of foods, regardless of the energy density. From “Dietary Variety impairs habituation in children” by J. L. Temple, A. M. Giacomelli, J. N. Roemmich and L. H. Epstein, 2008, Health Psychology, 27, S10-S19. Copyright 2008 American Psychological Association.

2.1. Stimulus specificity and long-term habituation

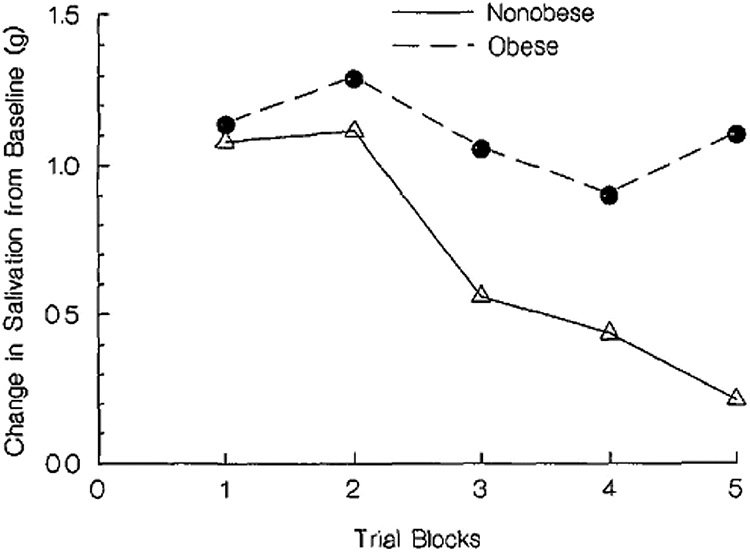

Habituation is stimulus specific, as presentation of foods with different sensory characteristics will serve as dishabituators [116]. Long-term habituation can be observed if people consume the same foods regularly [117, 118]. For example, we have observed greater habituation for adults served macaroni and cheese daily rather than once per week over a 5-week period [117]. In addition, long-term habituation may be a mechanism for the effect of reduced variety on weight control in behavioral weight control studies [118]. The rate of habituation is related to energy intake, with faster habituation being related to lower energy intake. There are differences in the rate of habituation in individuals with and without obesity [119, 120]. As shown in Fig. 5, adults with obesity showed slower rates of habituation than those with lean weight (N = 20). Slower rates of habituation may be a marker for weight gain, as slow habituators gain more weight than people who habituate more rapidly [121]. Finally, rates of habituation for successful weight loss maintainers is similar to people without obesity and significantly faster than people without obesity and significantly faster than people with obesity [122].

Fig. 5.

Salivary responding to lemon yogurt in obese and non-obese women across five blocks of two trials. From “Differences in salivation to repeated food cues in obese and nonobese women” by L. H. Epstein, R. Paluch, and K. J. Coleman, 1996, Psychosomatic Medicine, 58, 160–164. Copyright 1996 American Psychomatic Society.

2.2. Reinforcement processes, habituation and the role of memory in habituation

Initial presentation of habituation theory focused on the stimulus-response or reflexive nature of habituation, and the sensory processes that can influence habituation [108, 109]. Theories of habituation were expanded to include operant behaviors to acquire reinforcers, and the role of reinforcement processes in habituation, by empirical and theoretical work by McSweeney and colleagues [123 - 125]. This research was stimulated by the common observation that within a session, operant response rates for a reinforcer typically decline, resembling habituation curves, and these patterns of responding can be restored by dishabituating stimuli.

McSweeney and colleagues have shown that these changes in operant responding for a reinforcer, including food, were not due to reinforcer satiation [126 - 128], but rather to habituation, and the changes in operant behavior met the majority of criteria established to define habituation [123 - 125].

We have used Wagner's standard operating procedure (SOP) theory [129, 130], which focuses on memory processes, as a way to conceptualize how habituation theory is related to eating and obesity research. While interested readers should consult these papers to understand implications of this approach to understanding eating, a brief overview follows. In the initial model, a representation of a stimulus is stored in short term memory, and, if the next stimulus matches information in short term memory, stimulus processing is reduced, along with attenuation of the response [3]. This theory has been revised and expanded based on newer models of memory and associative conditioning using a connectionist approach to memory [131]. The newer model includes activation of memory node to an A1 state upon initial presentation of a stimulus, followed by decay of activation to A2 state, and finally an inactive state (I). This model can account for dishabituation, novel stimuli, variety and stimulus specificity of habituation. Research has shown similar patterns of behavioral and physiological response decrement to repeated presentation of food [3].

While habituation research is stimulus specific, this is similar to a wealth of studies on sensory specific satiety [132 - 137]. Similar to habituation, sensory specific satiety shows reduction in hedonics to repeatedly presented food, and recovery of eating if a new food is presented [132]. Likewise, changing the stimulus characteristics of the food, even small changes in shape or color of the food, can reduce sensory specific satiety [138]. Also similar to habituation, introducing variety will slow down sensory specific satiety. Finally, repeated presentation of the same food stimulus over days can lead to long-term sensory specific satiety [139]. We have previously presented a thorough discussion of similarities and differences between habituation and sensory specific satiety [3].

Elegant neurobiological research has shown that repeated presentation of a food results in reduction in neural responding in the hypothalamus and brain reward centers to repeated foods, while the taste cortex continues to register presentation of the food stimulus. In this body of research, presentation of a novel food can recover responding to neurons that had shown habituation to the initial stimulus [132, 133, 140 - 144]. These data strongly suggest that habituation serves as a signal for termination of a meal, independent of energy consumption.

2.3. Characteristics of foods and habituation

There is limited research on characteristics of foods that influence habituation. Research comparing habituation of food hedonics to sweet tasting liquid in persons with and without obesity suggest persons with obesity habituate at a slower rate to sweet tasting liquids than leaner peers [145]. This study did not compare rates of habituation to other types of food, so the research may just be reflecting a general tendency of people with obesity to habituate more slowly to food. Research comparing rates of salivary habituation for low calorie (32 kcal) versus higher calorie (320 kcal) gelatin showed no difference in the rate of habituation to repeated presentations of the two types of foods, suggesting that the sensory characteristics of the sweet food, rather than calories, was the primary influence on the rate of habituation [146]. In another study, women were presented with repeated presentation of one of four yogurts that systematically varied carbohydrate and fat content of the yogurt [147]. The rate of habituation and the number of trials to fullness were studied. While carbohydrate content of food again did not influence the rate of habituation, participants provided higher fat yogurt habituated at a significantly faster rate, and required fewer trials to report fullness [147]. These data suggest that oral habituation in humans may be more sensitive to fat content of food than sugar content of food. If this data is integrated into the previous discussion of reinforcing value of sugar or high-glycemic foods, sugar may drive high reinforcing value of food, while habituation may not be responsive to differences in caloric content of sweet tasting foods, if the sensory qualities of food are similar.

2.4. Olfactory and gustatory habituation

Olfactory and gustatory cues are important components of flavor, which may combine to influence both the reinforcing value of food and habituation to food [148]. Reaction times to identify olfactory or gustatory cues is faster when they are presented together than separately [149]. While the goal of both food reinforcement and habituation studies is to study how these processes influence eating, a more mechanistic approach to the sensory processes that guide eating may prove important. Given the importance of sensory processes to habituation, it is possible that wide individual differences in perception of olfactory or gustatory cues could influence habituation, similar to how individual differences in gustatory perception thresholds are related to reinforcing value of food [103]. This may be particularly relevant for people with diabetes, who have known decrements in sensitivity to food stimuli, including sweetness, which may lead to increased consumption of sweet foods to yield the same degree of perceived sweetness [150]. This could further complicate their metabolic control. Research is needed to identify the unique contributions of visual, olfactory and gustatory cues to habituation.

In summary, research on what nutrient, flavor, or sensory characteristics of food modify habituation is needed. While long-term habituation is possible across meals, it is not clear how to generalize long-term habituation to similar stimuli, or on what dimensions a stimulus generalization gradient can be created. For example, would someone have to eat the same food each day, or would foods that taste similar produce long-term habituation. Likewise, research on the relative importance of olfactory versus gustatory stimuli for habituation is unknown. Finally, given the importance of stimulus intensity to rate of habituation, research is needed to relate individual differences in sensory perception and rate of habituation for foods that differ in stimulus intensity. We suggest several interesting new areas of research.

The importance of olfactory and gustatory cues, and their combination, is needed to understand how to amplify stimulus characteristics of foods to promote habituation. While flavor is largely the combination of smell and taste, either can be manipulated separately to influence consumption. For example, does olfactory habituation, occurring for people who work in a environment with constant access to strong olfactory food stimuli, reduce their cravings for or their consumption of those foods?

Stimulus generalization gradients for olfactory, gustatory and their combination is needed to identify how similar foods need to be to result in long-term habituation across meals. Given that small changes in the characteristics of food, such as adding spices or condiments, can influence habituation, does habituation to one food generalize to other foods? That would be useful to know to enhance the effect of habituation on reducing food intake.

There are wide individual differences in sensory perception to olfactory or gustatory aspects of food. The importance of these individual differences to habituation is unknown. To our knowledge, there is limited research on how individual differences in sensory perception of food and rates of habituation to food. Perhaps people who are exceptionally sensitive to specific characteristics of foods, such as supertasters, may require a different pattern of exposure to food to enhance habituation.

3. Integrating food reinforcement and habituation

Our laboratory has completed two studies that have measured both the reinforcing value of food and habituation to food. In the first study, the goal was to determine the relationship between food reinforcement and habituation, and to assess whether food deprivation has the same effect on both processes. Food reinforcement and habituation were studied in separate sessions for 22 female participants, and participants had the opportunity to consume as much food as desired in an ad libitum breakfast session [1]. Half of the subjects were studied after at least 8 h of food deprivation, while the other half also had 8 h of food deprivation, but were provided a preload to manipulate deprivation. Food deprivation increased the reinforcing value of food, but did not modify habituation. Reinforcing value of food and habituation to food were correlated (r = 0.62), and they were both related to ad libitum energy intake. Hierarchical linear modeling showed that habituation entered in step 1 accounted for 30% of the variance in energy intake, and adding reinforcing value of food increased the variance accounted for to 57.5%. Thus, both reinforcing value and habituation were related to intake in a separate meal, accounting for almost 60% of the variance in intake. The correlation between the two suggested that those who habituated slower found food more reinforcing.

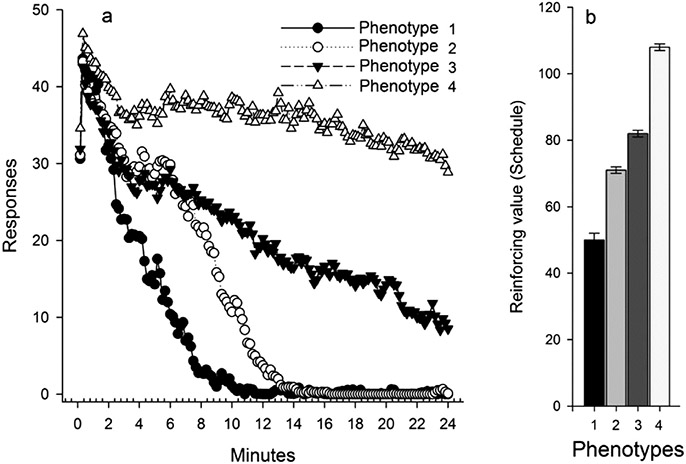

The hypothesis that people who habituate slower would find food more reinforcing was tested in a study with 229 8–12 year-old children at risk for obesity [151]. Both reinforcing value and habituation to snack foods were measured, and habituation responding was categorized into four patterns, from very rapid habituation to very slow, and almost no habituation. Differences in reinforcing value were compared across these patterns of habituation, with clear differences in reinforcing value observed between those who habituated fast versus habituated slowly [151]. These differential patterns of responding are shown in Fig. 6. In summary, these studies showed that reinforcing value and habituation to food are related, that they each contribute independently to the amount of food consumed, and the patterns are consistent across children and adults.th obesity [122].

Fig. 6.

Habituation phenotypes and relative reinforcing value of food. Graphs of responding in 10 s epochs (a), and reinforcing value (mean ± SEM) of food by habituation phenotype. From “High reinforcing value of food is related to slow habituation to food” by L. H. Epstein, K. A. Carr, A. O’Brien, R. A. Paluch and J. L. Temple, 2020, Eating Behaviors, 38, 101,414. Copyright 2020 Elsevier Inc.

Given the consistency across these two studies, the question is how do these processes complement each other to determine how much a person eats? It is first important to note that while habituation can influence cessation of eating, habituation is not considered to be relevant for the initiation of an eating episode. The drive to eat and the beginning of an eating bout is based in part on the reinforcing value of that food, and one possible model is that the initiation and cessation of eating are based on variations in the reinforcing value of food, which is high in the beginning of a meal and become less effective over repeated presentations of food [152]. From a purely behavioral perspective, excess consumption of a reinforcer can lead to reinforcer specific satiation, and thus cessation of eating that food. Within behavioral analysis, satiation refers to the fact that any reinforcer (including non-food reinforcers, such as reading, etc.) can lose value after repeated consumption [74].

There is another possibility for the primary role of food reinforcement in eating certain types of food, which could be considered “super-stimuli” in that they overload normal inhibitory mechanisms that would lead to satiation and disrupt normal appetitive mechanisms [97, 153] that would lead to cessation of eating, including habituation. From the perspective of stimulus intensity, it is possible that habituation to high intensity sensory stimuli occurs slowly or not at all. For most types of food, it is likely that both cues to start eating and cues to stop eating are relevant, rather than stopping eating just being associated with a decline of the reinforcing value of food. While clearly reinforcing value is a main appetitive cue, the fact that both reinforcing value and habituation predicted energy intake in a mixed cafeteria style breakfast [1], suggests that only focusing on reinforcing value provides an incomplete picture of how these processes can influence food intake at least for the foods studied.

There is one potential way in which habituation may be relevant for maintaining consumption of food. While it is known that after someone has habituated and stopped consuming one food, presenting a novel food or non-food stimulus can result in dishabituation and recovery of eating [3]. In many situations, people are presented with multiple foods in mixed meals. It is unclear what happens to other foods in a mixed meal after someone has habituated to one food. It the reinforcing value of another food increased, reduced, or will it have no effect on eating the other foods? Can habituation to one food generalize to similar foods? This idea leads to interesting speculations about how people consume foods in a mixed meal. For example, consider a meal with chicken, mashed potatoes and green beans. Some people will eat all their mashed potatoes, then turn to the chicken and end with the green beans. Other people will take a bite of chicken, a bite of mashed potatoes, back to chicken, then green beans, etc. Patterns of habituation, and amount of food consumed may be quite different for those two types of eating.

It is likely that in many eating bouts, the reinforcing value drives the initiation of eating, and during the eating episode habituation begins and by the end of the meal, the emphasis is on habituation. Research showing people who habituate slowly also find food more reinforcing [1, 151] suggests that reinforcing value maintains eating longer before habituation begins, and habituation may be slower for foods that are highly reinforcing. To our knowledge, there is no research on the rate of habitation comparing foods that differ in their reinforcing value. Our previous research has examined individual differences in these processes for the same foods [115, 154]. Given that the reinforcing value of food may differ based on their macronutrient content or glycemic index [89], and that the rate of habituation may differ based on macronutrient, olfactory or gustatory aspects of food [155], these relationships should be disentangled.

Based on research showing that visualization of food stimuli can elicit similar responses as consumption of food, Morewedge and colleagues [156] presented a series of studies that had participants repeatedly imagine eating candy coated chocolates or cheese cubes, versus a control task, and showed reduction in consumption of the imagined food relative to the control task. In a final study, participants imagined eating cheese cubes or engaging in a control task, and assessed changes in liking as well as reinforcing value to eat cheese cubes. Results showed a reduction in reinforcing value for cheese cubes, but not liking of cheese, after repeated sensory experience with cheese cubes. Given that participants did not eat any of the food, the reduction in reinforcing value cannot be understood based on energy intake of cheese cubes. Havermans and colleagues showed that repeated presentation of a food resulted in reduced liking of that food in relationship to foods not consumed, as well as reduction in reinforcing value of foods consumed versus not consumed [157]. The results of these studies are consistent with research showing habituation is important in regulating reinforcer effectiveness [124].

3.1. Sensitization and habituation

Sensitization has different meanings for food reinforcement and habituation. When considering reinforcement processes, sensitization refers to an increase in the reinforcing value of a commodity over time after repeated exposures [158]. This process is commonly studied for drugs of abuse [159]. Many stimulants show sensitization, which suggests their value can increase over repeated exposures, accounting in part for their abuse potential [160]. Research suggests that food can sensitize [158], which may be relevant for how repeated presentations of a food lead to increases in liking and preference, as well as how a food can gain value over time. There may be foods that are reinforcing at first taste (e.g. chocolate), but other foods may gain value over time, and people with obesity may be more likely to sensitize than those without obesity [161].

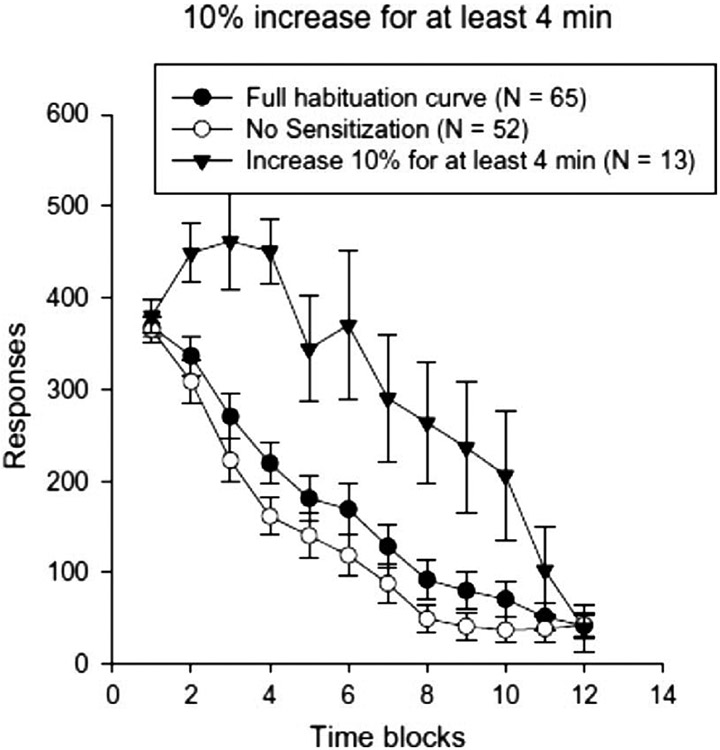

In habituation theory, sensitization refers to an initial increase in response prior to a decrease [108, 109]. This is something that is commonly observed, and individual differences in sensitization may provide insight into how fast people habituate, and people who sensitize habituate slower [155]. Fig. 7 shows slower habituation for children who sensitize, irrespective of their weight status. It is tempting to relate the initial increases in responding during stimulus presentation in habituation studies to reinforcement processes that are initially engaged prior to habituation processes being dominant. The initial increases may also be related to individual differences in sensory characteristics of foods.

Fig. 7.

Motivated responding (mean ± SEM) on habituation task for children who sensitized (a 10% increase in responding over the first four minutes) and those who did not, along with the average habituation curve for all children. From “Sensitization and habituation of motivated behavior in overweight and non-overweight children” by L. H. Epstein, J. L. Robinson, J. L. Temple, J. N. Roemmich, A. Marusewski and R. Nadbrzuch, 2008, Learning and Motivation, 39, 243–255. Copyright 2008 Elsevier Inc.

Research examining brain responses to repeated presentation of food cues may provide support for the idea that activation of brain reward centers is related to sensitization as well as the decay in responding for food. Recall the series of studies by Rolls and colleagues who showed that hypothalamic and reward centers decreased with repeated food presentations, and neurons that had habituated recovered responding when presented a novel food stimulus [132, 133, 140, 141, 143, 144, 162]. This is a demonstration of habituation, and research across a variety of sensory stimuli has shown habituation in brain activation with repeated presentation of stimuli [149, 163 - 166].

The idea that food reinforcement and habituation to food are related, and may combine to determine food intake, still provides for individual differences in how these variables influence each person, for each type of food. While the two factors are highly correlated (r = 0.62) [1], there is about 38% overlapping variance, leaving many people whose eating may be predominately influenced by food reinforcement, while others may be influence predominantly through habituation. These differences are relevant if the same or different approaches can be used to modify food intake. If they are considered separately, than relevant treatment approaches could be designed to reduce food reinforcement, which would have an effect on energy consumption since people may choose not to eat in situations where eating or engaging in another behavior is an option. Likewise, if ways to speed up habituation are developed, then that could reduce energy intake by speeding up cessation of a meal. There may be wide individual differences in how much each factor contributes to eating, however, and careful study of moderators or single case experimental designs may be needed to address these questions.

One factor that may help understand how obesity might develop is rate of eating. Research has shown that rate of eating is more rapid in persons with obesity than without [167], and people eat faster when they are eating highly reinforcing foods than less reinforcing foods [168]. During a meal the rate of food consumption often decreases, which also may be influenced by amount of deprivation or subjective hunger [167]. In persons with obesity, this initial increase in eating rate may be similar to sensitization, would signal greater energy intake slower [155]. Thus, one hypothesis is that the failure to initiate habituation in the early parts of a meal, or the failure to transition from sensitization to habituation is important for the development of obesity.

In summary, research integrating food reinforcement and habituation is in its infancy. To our knowledge only two studies addressed these two processes simultaneously [1, 151], and both show a relationship between these behavioral processes, with those high in food reinforcement also being slow to habituate to food. We present an initial attempt to provide models for how these processes may complement each other to determine the amount of food consumed during an eating bout, but more research is needed. The potential that the sensitization phase of responding in an habituation task is related to reward processing, while the habituation phase is related to satiation may be a way to relate these two processes [169]. Individual differences in eating rate are suggestive of sensitization and habituation, as people eat quite rapidly in the early phase of a meal when they are hungry [167], followed by regular reductions in eating rate as the meal progresses. It would be interesting to assess changes in rate of eating when a novel, and highly palatable food is presented that results in the recovery of eating. While there are many different paths to take in studying how these processes may interact, we suggest several ideas based on our review.

Is the rate of habituation a function of the reinforcing value of a food? Is the greater intake of foods with higher reinforcing value due also to delayed activation of habituation?

Will habituation to a repeated stimulus result in a reduction in the reinforcing value of that stimulus? While this is observed when repeatedly imagining eating a food, it is important to replicate this effect using actual food presentations, and include a design that demonstrates the reduction was due to habituation.

Does the sensitization phase of habituation responding reflect food reinforcement? Can the sensitization phase of habituation responding be manipulated to reduce food reinforcement and reduce eating? What characteristics of foods are associated with sensitization? Given that people who sensitize habituate to food at a slower rate, and thus would consume more food, developing a better understand of this phenomena may help understand the relationship between individual differences in habituation and food consumption.

While both high food reinforcement and slow habituation independently predict weight gain, are there additive effects if you are high in food reinforcement and slow to habituate? This would be interesting to study as predictors of weight gain in observational studies of youth, as well as weight gain in people during a follow-up or maintenance phase of an intensive weight control program.

4. Conclusions

Both food reinforcement and habituation are important factors to understand how people eat. Food reinforcement represents an appetitive cue, which determines, in part, when and what people eat, and habituation represents a satiety cue that determines in part when people stop eating. Research is needed using innovative designs to better understand the contributions that these two factors make to regulate eating, and how much each factor is weighed based on the initial hunger state of the person, the amount and rate of food consumed, and the types of food consumed. Addressing these issues may play an important role to developing personalized methods to modify eating and energy intake.

Highlights.

Food reinforcement is a process related to initiation of eating and is positively related to energy intake and obesity.

Habituation is a process related to cessation of eating and can be described as a reduction in physiological or affective response to a stimulus, or a reduction in the behavioral responding to obtain a stimulus.

Habituation phenotypes show reliable relationships with reinforcing value, such that people who habituate faster also find food less reinforcing, and both contribute to variance in ad libitum energy intake.

Developing a better understanding of cues to start and stop eating is fundamental to understanding how to modify eating behavior.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [U01 HL131552]; The National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases [UH3 DK109543]; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [RO1HD080292 and RO1HD088131].

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Carr KA, Epstein LH, Relationship between food habituation and reinforcing efficacy of food, Learn. Motivat 42 (2011) 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bouton ME, Learning and Behavior: A contemporary Synthesis, Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Epstein LH, Temple JL, Roemmich JN, Bouton ME, Habituation as a determinant of human food intake, Psychol. Rev 116 (2009) 384–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Epstein LH, Leddy JJ, Temple JL, Faith MS, Food reinforcement and eating: a multilevel analysis, Psychol. Bull 133 (2007) 884–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lumeng JC, Weeks HM, Asta K, Sturza J, Kaciroti NA, Miller AL, et al. , Sucking behavior in typical and challenging feedings in association with weight gain from birth to 4 months in full-term infants, Appet. 153 (2020), 104745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Carroll ME, Deconstructing relative reinforcing efficacy and situating the measures of pharmacological reinforcement with behavioral economics: a theoretical proposal, Psychopharmacol. (Berl.) 153 (2000) 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Richardson NR, Roberts DC, Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy, J. Neurosci. Meth 66 (1996) 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Crandall AK, Temple JL, Experimental scarcity increases the relative reinforcing value of food in food insecure adults, Appet. 128 (2018) 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goldfield GS, Lumb A, Smoking, dietary restraint, gender, and the relative reinforcing value of snack food in a large university sample, Appet. 50 (2008) 278–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Savell M, Eiden RD, Kong KL, Tauriello S, Epstein L, Fabiano G, et al. , Development of a measure of the relative reinforcing value of food versus parent-child interaction for young children, Appet. 153 (2020), 104731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kong KL, Epstein LH, Food reinforcement during infancy, Prev.Med 92 (2016) 100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kong KL, Eiden RD, Feda DM, Stier CL, Fletcher KD, Woodworth EM, et al. , Reducing relative food reinforcement in infants by an enriched music experience, Obesi. 24 (2016) 917–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kong KL, Feda DM, Eiden RD, Epstein LH, Origins of food reinforcement in infants, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 101 (2015) 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rollins BY, Loken E, Savage JS, Birch LL, Measurement of food reinforcement in preschool children. associations with food intake, BMI, and reward sensitivity, Appet. 72 (2014) 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rollins BY, Loken E, Savage JS, Birch LL, Effects of restriction on children’s intake differ by child temperament, food reinforcement, and parent’s chronic use of restriction, Appet. 73 (2014) 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Berridge KC, Food reward: brain substrates of wanting and liking, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 20 (1996) 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kelley AE, Berridge KC, The neuroscience of natural rewards: relevance to addictive drugs, J. Neurosci 22 (2002) 3306–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cassidy RM, Tong Q, Hunger and satiety gauge reward sensitivity, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausan.) 8 (2017) 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Berridge KC, Robinson TE, What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res. Rev 28 (1998) 309–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Flagel SB, Akil H, Robinson TE, Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues: implications for addiction, Neuropharmacol. 56 (2009) 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Weingarten HP, Conditioned cues elicit feeding in sated rats: a role for learning in meal initiation, Sci. 220 (1983) 431–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Van Gucht D, Vansteenwegen D, Beckers T, den bergh o Van, return of experimentally induced chocolate craving after extinction in a different context: divergence between craving for and expecting to eat chocolate, Behav. Res. Ther 46 (2008) 375–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bongers P, Jansen A, Emotional eating and pavlovian learning: evidence for conditioned appetitive responding to negative emotional states, Cogn. Emot 31 (2017) 284–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jansen A, Theunissen N, Slechten K, Nederkoorn C, Boob B, Mulkens S, et al. , Overweight children overeat after exposure to food cues, Eat. Behav 4 (2003) 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Potenza MN, Grilo CM, How relevant is food craving to obesity and its treatment? Front. Psychiat 5 (2014) 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Boswell RG, Kober H, Food cue reactivity and craving predict eating and weight gain: a meta-analytic review, Obes. Rev 17 (2016) 159–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cartoni E, Balleine B, Baldassarre G, Appetitive pavlovian-instrumental transfer: a review, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 71 (2016) 829–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Epstein LH, Carr KA, Lin H, Fletcher KD, Food reinforcement, energy intake, and macronutrient choice, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 94 (2011) 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Temple JL, Legierski CM, Giacomelli AM, Salvy SJ, Epstein LH, Overweight children find food more reinforcing and consume more energy than do nonoverweight children, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 87 (2008) 1121–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Epstein LH, Wright SM, Paluch RA, Leddy JJ, Hawk LW Jr., Jaroni JL, et al. , Relation between food reinforcement and dopamine genotypes and its effect on food intake in smokers, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 80 (2004) 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hill C, Saxton J, Webber L, Blundell J, Wardle J, The relative reinforcing value of food predicts weight gain in a longitudinal study of 7-10-y-old children, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 90 (2009) 276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Epstein LH, Yokum S, Feda DM, Stice E, Food reinforcement and parental obesity predict future weight gain in non-obese adolescents, Appet. 82 (2014) 138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Carr KA, Lin H, Fletcher KD, Epstein LH, Food reinforcement, dietary disinhibition and weight gain in nonobese adults, Obesi. (Silver Spring) 22 (2014) 254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Epstein LH, Carr KA, Lin H, Fletcher KD, Roemmich JN, Usual energy intake mediates the relationship between food reinforcement and BMI, Obesi. (Silver Spring) 20 (2012) 1815–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Carr KA, Epstein LH, Influence of sedentary, social, and physical alternatives on food reinforcement, Heal. Psychol 37 (2018) 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Buscemi J, Murphy JG, Berlin KS, Raynor HA, A behavioral economic analysis of changes in food-related and food-free reinforcement during weight loss treatment, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 82 (2014) 659–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Figlewicz DP, Insulin, food intake, and reward, Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiat 8 (2003) 82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Figlewicz DP, Benoit SC, Insulin, leptin, and food reward: update 2008, Am. J. Physiol. Regulat. Integrat. Comparat. Physiol 296 (2009) R9–R19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Raynor HA, Epstein LH, The relative-reinforcing value of food under differing levels of food deprivation and restriction, Appet. 40 (2003) 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Flack KD, Ufholz K, Casperson S, Jahns L, Johnson L, Roemmich JN, Decreasing the consumption of foods with sugar Increases their reinforcing value: a potential barrier for dietary behavior change, J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 119 (2019) 1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gibson EL, Desmond E, Chocolate craving and hunger state: implications for the acquisition and expression of appetite and food choice, Appet. 32 (1999) 219–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gibson EL, Wardle J, Effect of contingent hunger state on development of appetite for a novel fruit snack, Appet. 37 (2001) 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Meule A, The psychology of food cravings: the role of food deprivation, Curr. Nutr. Rep 9 (2020) 251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cameron JD, Goldfield GS, Cyr MJ, Doucet E, The effects of prolonged caloric restriction leading to weight-loss on food hedonics and reinforcement, Physiol. Behav 94 (2008) 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kahathuduwa CN, Binks M, Martin CK, Dawson JA, Extended calorie restriction suppresses overall and specific food cravings: a systematic review and a meta-analysis, Obes. Rev 18 (2017) 1122–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Martin CK, O’Neil PM, Pawlow L, Changes in food cravings during low-calorie and very-low-calorie diets, Obesi. (Silver Spring) 14 (2006) 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Oustric P, Gibbons C, Beaulieu K, Blundell J, Finlayson G, Changes in food reward during weight management interventions: a systematic review, Obesi. Rev 19 (2018) 1642–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Simon JJ, Becker A, Sinno MH, Skunde M, Bendszus M, Preissl H, et al. , Neural food reward processing in successful and unsuccessful weight maintenance, Obesi. (Silver Spring) 26 (2018) 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Castellanos EH, Charboneau E, Dietrich MS, Park S, Bradley BP, Mogg K, et al. , Obese adults have visual attention bias for food cue images: evidence for altered reward system function, Int. J. Obesi 33 (2009) 1063–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mogg K, Bradley BP, Hyare H, Lee S, Selective attention to food-related stimuli in hunger: are attentional biases specific to emotional and psychopathological states, or are they also found in normal drive states? Behav. Res. Ther 36 (1998) 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kemps E, Tiggemann M, Attentional bias for craving-related (chocolate) food cues, Exp. Clin. Psychopharm 17 (2009) 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Carr KA, Epstein LH, Working memory and attentional bias on reinforcing efficacy of food, Appet. 116 (2017) 268–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bongers P, van de Giessen E, Roefs A, Nederkoorn C, Booij J, van den Brink W, et al. , Being impulsive and obese increases susceptibility to speeded detection of high-calorie foods, Heal. Psychol 34 (2015) 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Schepers ST, Bouton ME, Hunger as a context: food seeking that is inhibited during hunger can renew in the context of satiety, Psychol.Sci 28 (2017) 1640–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bouton ME, A learning theory perspective on lapse, relapse, and the maintenance of behavior change, Heal. Psychol 19 (2000) 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bouton ME, Extinction of instrumental (operant) learning: interference, varieties of context, and mechanisms of contextual control, Psychopharmacol. (Berl.) 236 (2019) 7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Epstein LH, Lin H, Carr KA, Fletcher KD, Food reinforcement and obesity. psychological moderators, Appet. 58 (2012) 157–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nederkoorn C, Braet C, Van Eijs Y, Tanghe A, Jansen A, Why obese children cannot resist food: the role of impulsivity, Eat Behav. 7 (2006) 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Carr KA, Daniel TO, Lin H, Epstein LH, Reinforcement pathology and obesity, Curr. Drug Abuse Rev 4 (2011) 190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Bickel WK, Athamneh LN, Snider SE, Craft WH, DeHart WB, Kaplan BA, et al. Reinforcer pathology: implications for substance abuse intervention. Curr. Top Behav. Neurosci. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bickel WK, Stein JS, Moody LN, Snider SE, Mellis AM, Quisenberry AJ, Toward narrative theory: interventions for reinforcer pathology in health behavior, in: Stevens JR (Ed.), Impulsivity: How time and Risk Influence Decision Making, Springer, New York, NY, 2017, pp. 227–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Deshpande HU, Mellis AM, Lisinski JM, Stein JS, Koffarnus MN, Paluch R, et al. , Reinforcer pathology: common neural substrates for delay discounting and snack purchasing in prediabetics, Brain Cogn. 132 (2019) 80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rollins BY, Dearing KK, Epstein LH, Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women, Appet. 55 (2010) 420–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Epstein LH, Jankowiak N, Fletcher KD, Carr KA, Nederkoorn C, Raynor HA, et al. , Women who are motivated to eat and discount the future are more obese, Obesi. 22 (2014) 1394–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Best JR, Theim KR, Gredysa DM, Stein RI, Welch RR, Saelens BE, et al. , Behavioral economic predictors of overweight children’s weight loss, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 80 (2012) 1086–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bickel WK, Tegge AN, Carr KA, Epstein LH Reinforcer pathology’s alternative reinforcer hypothesis: a preliminary examination. Heal. Psychol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Jansen A, Schyns G, Bongers P, van den Akker K, From lab to clinic: extinction of cued cravings to reduce overeating, Physiol. Behav 162 (2016) 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Schyns G, Roefs A, Jansen A, Tackling sabotaging cognitive processes to reduce overeating; expectancy violation during food cue exposure, Physiol. Behav 222 (2020), 112924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Schyns G, Roefs A, Smulders FTY, Jansen A, Cue exposure therapy reduces overeating of exposed and non-exposed foods in obese adolescents, J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiat 58 (2018) 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Schyns G, van den Akker K, Roefs A, Hilberath R, Jansen A, What works better? Food cue exposure aiming at the habituation of eating desires or food cue exposure aiming at the violation of overeating expectancies? Behav. Res. Ther 102 (2018) 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Schyns G, van den Akker K, Roefs A, Houben K, Jansen A, Exposure therapy vs lifestyle intervention to reduce food cue reactivity and binge eating in obesity: a pilot study, J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiat 67 (2020), 101453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Jansen A, Houben K, Roefs A, A cognitive profile of obesity and its translation into new interventions, Front. Psychol 6 (2015) 1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Boutelle KN, Zucker NL, Peterson CB, Rydell SA, Cafri G, Harnack L, Two novel treatments to reduce overeating in overweight children: a randomized controlled trial, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 79 (2011) 759–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL, Applied Behavior Analysis. Second ed., Pearson Education Limited, London, United Kingdom, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Carr KA, Epstein LH, Choice is relative: reinforcing value of food and activity in obesity treatment, Am. Psychol 75 (2020) 139–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Boyle MA, Hoffmann AN, Lambert JM, Behavioral contrast: research and areas for investigation, J. Appl. Behav. Anal 51 (2018) 702–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wiss DA, Avena N, Rada P, Sugar addiction: from evolution to revolution, Front. Psychiat 9 (2018) 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG, Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 32 (2008) 20–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Avena NM, Long KA, Hoebel BG, Sugar-dependent rats show enhanced responding for sugar after abstinence: evidence of a sugar deprivation effect, Physiol. Behav 84 (2005) 359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Sharma S, Hryhorczuk C, Fulton S, Progressive-ratio responding for palatable high-fat and high-sugar food in mice, J. Vis. Exp 63 (2012) e3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Rada P, Avena NM, Hoebel BG, Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell, Neurosci. 134 (2005) 737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Blum K, Liu Y, Shriner R, Gold MS, Reward circuitry dopaminergic activation regulates food and drug craving behavior, Curr. Pharm. Des 17 (2011) 1158–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Avena NM, Hoebel BG, A diet promoting sugar dependency causes behavioral cross-sensitization to a low dose of amphetamine, Neurosci. 122 (2003) 17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Avena NA, Carrillo CA, Needham L, Leibowitz SF, Hoebel BG, Sugar-dependent rats show enhanced intake of unsweetened ethanol, Alcoh. 34 (2004) 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Ivezaj V, Stoeckel LE, Avena NM, Benoit SC, Conason A, Davis JF, et al. , Obesity and addiction: can a complication of surgery help us understand the connection? Obesi. Rev 18 (2017) 765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN, Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load, PLoS ONE 10 (2015), e0117959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Blum K, Thanos PK, Gold MS, Dopamine and glucose, obesity, and reward deficiency syndrome, Front. Psychol 5 (2014) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Wojnicki FH, Babbs RK, Corwin RL, Reinforcing efficacy of fat, as assessed by progressive ratio responding, depends upon availability not amount consumed, Physiol. Behav 100 (2010) 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Epstein LH, Carr KA, Scheid JL, Gebre E, O'Brien A, Paluch RA, et al. , Taste and food reinforcement in non-overweight youth, Appet. 91 (2015) 226–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Rada P, Bocarsly ME, Barson JR, Hoebel BG, Leibowitz SF, Reduced accumbens dopamine in Sprague-Dawley rats prone to overeating a fat-rich diet, Physiol. Behav 101 (2010) 394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG, Sugar and fat bingeing have notable differences in addictive-like behavior, J. Nutr 139 (2009) 623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Barnes MJ, Lapanowski K, Conley A, Rafols JA, Jen KLC, Dunbar JC, High fat feeding is associated with increased blood pressure, sympathetic nerve activity and hypothalamic mu opioid receptors, Brain Res. Bull 61 (2003) 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Drewnowski A, Holden-Wiltse J, Taste responses and food preferences in obese women: effects of weight cycling, Int. J. Obesi. Relat. Metab. Disord 16 (1992) 639–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]