Abstract

Background:

Subtotal cholecystectomy has been reported in 8% and 3.3% of patients undergoing open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, respectively. According to a recent nationwide survey, the utilisation of subtotal cholecystectomy in the treatment of acute cholecystitis is on the rise. In 1.8% of subtotal cholecystectomies, a reoperation is required. Reoperations for residual gallbladder (GB), gallstones, and related complications accounted for half of the reoperations described in the literature after subtotal cholecystectomy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical profile, risk of complications, and feasibility of laparoscopic approaches and surgical procedures in patients with recurrent symptoms from a residual GB that necessitated a completion cholecystectomy.

Methods:

Patients who underwent surgery for residual GB with stones and/or complications between January 2007 and January 2020 were included in the study group. A prospectively maintained database was used to review patient information retrospectively. The demographic profile, operation details of the index surgery, current presentation, investigations performed, surgery details, morbidity and mortality were all included in the clinical information.

Results:

There were 13 patients who underwent completion cholecystectomy. The median age was 55 years (22–63 years). Prior operative notes mentioned subtotal cholecystectomy in only seven patients. The average time between the index surgery and the onset of symptoms was 30 months (2–175 months). A final diagnosis of residual GB with or without calculi was made by ultrasound (USG) in 11 patients and by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in two others. Choledocholithiasis (n = 4, 30.7%), acute cholecystitis (n = 2, one with empyema and GB perforation) and Mirizzi syndrome (n = 1) were seen as complications of residual gallstones in seven patients. All 13 patients underwent successful laparoscopic procedures. A fifth port was used in all. A critical view of safety was achieved in 12 patients. Two patients required laparoscopic common bile duct (CBD) exploration for CBD stones. Intraoperative cholangiograms were done in eight patients (61.5%). There were no conversions, injuries to the bile duct or deaths. Morbidity was seen in one. The patient required therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for cholangitis and CBD clearance on the fifth post-operative day. The median hospital stay was 4 days (3–7 days). At a median follow-up of 99 months, symptom resolution was seen in all 13 patients.

Conclusion:

Gallstones in the residual GB are associated with more complications than conventional gallstones. The diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion. MRCP is more accurate in establishing the diagnosis and identifying the associated complications, even if the diagnosis is made on USG in most patients. A pre-operative roadmap is provided by the MRCP. For patients with residual GB, laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy is a feasible and safe option.

Keywords: Cholecystectomy, completion cholecystectomy, laparoscopy, residual gallbladder, subtotal cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Subtotal cholecystectomy has been reported in 8% and 3.3% of patients undergoing open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, respectively.[1,2] Palanivelu et al. reported performing 265 laparoscopic cholecystectomies in cirrhotic patients, accounting for 2.6% of all laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed.[3] A laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy was performed on 77% of these individuals. A systematic review found that acute cholecystitis (72.1%), cholelithiasis in liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension (18.2%) and empyema or perforated gallbladder (GB) (6.1%) were the most common reasons for a subtotal cholecystectomy.[4] According to a recent nationwide survey, the utilisation of subtotal cholecystectomy in the treatment of acute cholecystitis is on the rise.[5] In 1.8% of patients who have had a subtotal cholecystectomy, reoperation is required.[4] During subtotal cholecystectomy, measures such as leaving a small remnant, ensuring stone clearance and cauterising the mucosa are used to prevent recurrent stones from the GB. Symptoms caused by residual GB calculi, on the other hand, may necessitate a completion cholecystectomy during follow-up. Reoperations for residual GB, gallstones, and related complications accounted for half of the reoperations described in the literature after subtotal cholecystectomy.[4] The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical profile, risk of complications, and feasibility of laparoscopic approaches and surgical procedures in patients with recurrent symptoms from a residual GB that necessitated a completion cholecystectomy. A review of pertinent published data is presented, as well as a management algorithm for patients with residual GB.

METHODS

Patients who underwent surgery for residual GB with stones and/or complications between January 2007 and January 2020 were included in the study group. A prospectively maintained database was used to review patient information retrospectively. The demographic profile, operation details of the index surgery, current presentation, investigations performed, surgery details, morbidity and mortality were all included in the clinical information. All of the patients had routine blood tests, including liver function tests (LFT). The initial diagnostic procedure was an abdominal ultrasound (USG). After a review of preliminary studies, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) was performed on patients with common bile duct (CBD) stones, either preoperatively or intraoperatively, depending on the treating surgeon and patient's preference. In all cases, a completion cholecystectomy was performed:

Step 1: Closed pneumoperitoneum from the palmar space. A fifth 5 mm port was used midway between the xiphoid and the umbilicus to the left of the midline for retraction of the duodenum, in addition to the normal four ports for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Step 2: Adhesiolysis: In the subhepatic regions, omental adhesions were released. The colon and duodenum were carefully dissected away from the residual GB. The critical view of safety (CVS) was achieved by dissecting Calot's triangle. A body-first approach was adopted in patients with obscured Calot's triangle. The 'D2 first' technique, which we previously reported on, was used in two patients with an obscure remnant GB wrapped in dense adhesions.[6] When biliary anatomy needed to be confirmed or laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (CBDE) was required, an intraoperative cholangiogram was performed

Step 3: The cystic duct and artery were clipped and divided in the usual fashion

Step 4: The residual GB was retrieved in an endo bag

Step 5: A supra-duodenal choledochotomy was used to perform laparoscopic CBDE in two patients. A 4F Fogarty catheter (0.75 ml balloon) was used to remove the CBD stones. Choledochoscopy was performed to ensure that the CBD was clear. One had primary closure with an endobiliary stent, while the other had T-tube closure. The endobiliary stent's distal end was placed in the duodenum. This was confirmed through fluoroscopy. The choledochotomy was closed using an interrupted 4-0 polydioxanone suture (PDS) suture

Step 6: A 28F subhepatic tube drain was placed in CBDE patients and in others on a case-by-case basis

Step 7: The port sites were managed as usual. No1 vicryl was used to close the umbilicus sheath, and 4-0 monocryl was used to close the skin.

Postoperative care was provided in the wards, and oral intake was resumed by the evening of the procedure. Patients were discharged on the first post-operative day and returned to the outpatient department a week later for follow-up. After 4–6 weeks, a second follow-up visit was scheduled, and after that, visits were only scheduled as needed.

RESULTS

There were 13 patients who underwent completion cholecystectomy, including five males (38.5%) and eight (61.5%) females. The median age was 55 years (22–63 years). Comorbidities were present in five of the individuals. In twelve patients, the initial cholecystectomy was conducted elsewhere, and in one patient, it was performed at our centre (subtotal cholecystectomy for empyema GB). According to the prior operative notes, only seven of the 13 patients with residual GB had subtotal cholecystectomy (53.8%) and the reasons were available only in four; obscure Calot's triangle (n = 2), Mirizzi syndrome (n = 1) and gangrenous cholecystitis (n = 1). The initial surgery was carried out by an open approach in six (46.2%) and by a laparoscopic approach in seven (53.8%). One patient in the laparoscopy group required a conversion to open cholecystectomy. None of the patients had a malignancy.

The average time between the index surgery and the onset of symptoms was 30 months (2–175 months). All 13 patients had abdominal pain. Fever and jaundice were observed in two of the individuals.

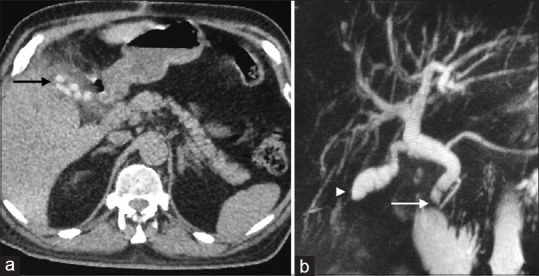

Table 1 summarises the diagnosis. The initial investigations included an LFT and an abdominal USG. In 11 patients (84.6%), MRCP was performed [Figure 1]. Only one patient underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT). Two patients had LFT derangement (obstructive pattern). In 11 patients and two patients, respectively, USG and MRCP were used to make the final diagnosis of residual GB with or without calculi. Choledocholithiasis (n = 4, 30.7%), acute cholecystitis (n = 2, one with empyema and GB perforation) and Mirizzi syndrome (n = 1) were seen as complications of residual gallstones in seven patients. In three cases and one case, respectively, USG and MRCP were used to diagnose choledocholithiasis. USG diagnosed the case of acute cholecystitis; however, a CT of the abdomen was required for localised GB perforation and a MRCP for Mirizzi syndrome, respectively.

Table 1.

Diagnosis of the patients

| Clinical diagnosis | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Symptomatic residual gallstones | 5 |

| Choledocholithiasis with/without residual gallstones | 4 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 2 |

| Mirizzi syndrome | 1 |

| Thick walled GB with gallstones | 1 |

| Total | 13 |

GB: Gallbladder

Figure 1.

(a) Computed tomography of the abdomen showing radio dense calculi in the residual gallbladder (arrow); (b) Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing a filling defect in the lower end of the dilated common bile duct (arrow) and a residual gallbladder (arrowhead)

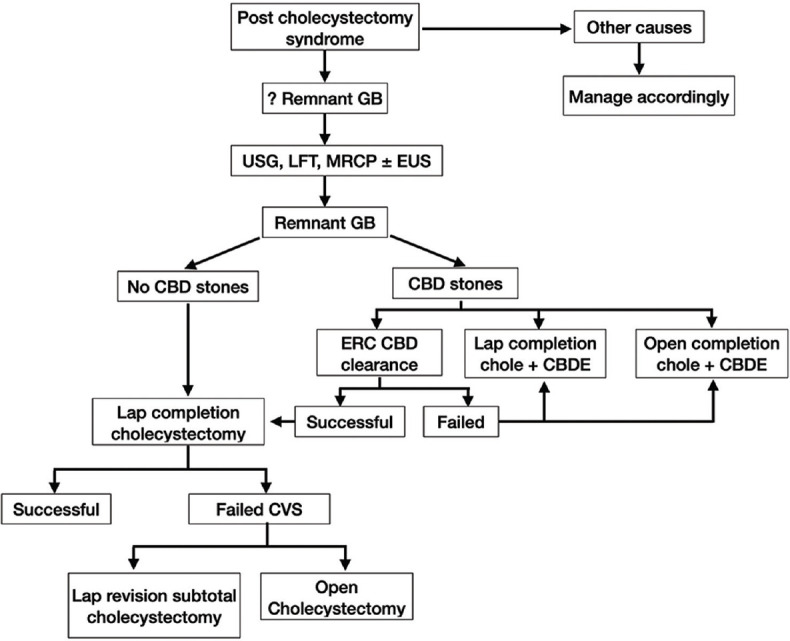

Management of residual gallbladder

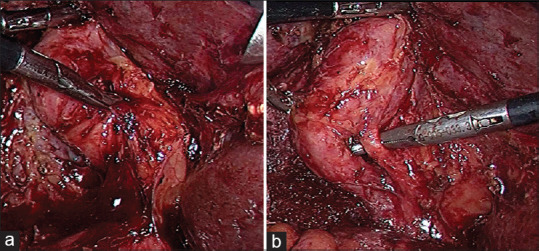

The laparoscopic procedure on all thirteen patients was successful. In addition to the standard cholecystectomy ports, a fifth port was placed one inch to the left of the midline, halfway between the xiphisternum and the umbilicus. In twelve of the thirteen patients, the CVS was achieved [Figure 2]. Because of inflammation at the Calot's, the cystic duct could not be identified in the case of localised GB perforation. As a result, a laparoscopic revision of subtotal cholecystectomy was performed. The residual GB stump was shortened to as small as possible, and the stump was left open with a sub-hepatic drain. Figure 3 depicts the algorithm for dealing with the residual GB.

Figure 2.

Operative photographs (a) identification of the residual GB after adhesiolysis; (b) demonstration of critical view of safety

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the management of residual gallbladder

Management of common bile duct stones

One of the four patients who had CBD stones discovered before surgery opted for laparoscopic CBD exploration. An ERC was performed on three of the remaining patients. It was a success in two cases and a failed in one. This patient had a successful CBD exploration by laparoscopy. In total, two patients had laparoscopic CBD explorations that were successful. In one, a primary CBD closure was performed, whereas in the other, a T-tube closure was performed. In addition, one patient was diagnosed with CBD stones after surgery (vide infra). There were five patients with CBD stones in total.

Use of intra-operative cholangogram (IOC)

An intra-operative cholangiogram was performed in eight patients (61.5%) for anatomical confirmation in six cases and CBD exploration in two cases. With the exception of a patient with localized GB perforation in whom cholangiography failed due to difficult retrograde cannulation of the cystic duct, cholangiography was successful in delineating the biliary anatomy, revealing free flow of contrast into the duodenum and demonstrating a CBD free of stones.

Non-biliary procedures were conducted in two cases, both of which were anatomical repairs of umbilical hernias.

Morbidity and mortality

There were no conversions, injuries to the bile ducts or deaths. Morbidity was seen in one patient. On the fifth post-operative day, the patient was readmitted with cholangitis with CBD calculi (patient with unsuccessful cholangiogram). He was treated with therapeutic ERC and CBD clearance. The remaining twelve patients had no morbidity. The average length of stay in the hospital was four days (3–7 days).

The histopathological evaluation of the operative specimens revealed chronic inflammatory changes in 11 patients and acute cholecystitis in two.

At a median follow-up of 99 months (8–168 months), symptom resolution was seen in all 13 patients.

DISCUSSION

The post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS), or the persistence or recurrence of symptoms after cholecystectomy, is a problem for both the patient and the treating physicians.[7] Peptic ulcer disease, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease are non-biliary causes of the syndrome, and these disorders are included in the differential diagnosis of right upper quadrant pain. Biliary dyskinesia, choledocholithiasis, and retained stones or the formation of new stones in the residual GB are all biliary causes of PCS. The current paper focuses on the residual GB.

Symptomatic residual GB poses several clinical challenges, and the discussion below addresses the following pertinent questions. Is there a delay in diagnosis in these patients? Second, is an abdominal USG sufficient for a diagnosis? Third, what should the evaluation strategy be, and how would it differ from that of a patient with conventional GB calculi? Fourth, what should be the operative strategy in these cases? Finally, what are the chances of having a remnant GB after the second surgery?

First, is there a delay in diagnosis in these patients? Given the history of cholecystectomy, recurrent cholelithiasis may be overlooked as a cause of right upper quadrant pain, especially in individuals who have no record of incomplete cholecystectomy. Gallstones can form after a subtotal cholecystectomy if the GB mucosa is preserved, or they can be retained stones from the prior surgery if the GB lumen is not adequately cleared. A higher incidence of residual GB calculi has been reported after subtotal cholecystectomy than after conventional cholecystectomy.[8] As a result, diagnosing symptomatic residual gallstones necessitate a high index of suspicion.[9]

Second, is an abdominal USG sufficient for a diagnosis? In most of the reported studies on residual GB, USG was employed as the initial investigation, with accuracy ranging from 60% to 89% [Table 2].[8,10,11,12] Similarly, we discovered that in 84.6% of the cases, USG accurately detected residual GB with or without calculi. MRCP is beneficial as a roadmap before surgery in difficult instances where a history of subtotal cholecystectomy is not forthcoming, a small cystic duct stump with a calculus or associated complications of gallstones are encountered. The accuracy of MRCP in detecting residual gallstones has been found to be >90% [Table 2].[8,10,11,12] Similarly, in our study, MRCP had high accuracy in detecting residual gallstones.

Table 2.

The reported accuracies of ultrasound and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in diagnosing residual gallbladder and stones

| Parmar et al. | Palanivelu et al. | Ahmed et al. | Singh et al. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USG (%) | 64 | 60 | 77.9 | 89 |

| MRCP (%) | 94 | 92 | 100 | 96 |

USG: Ultrasound, MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Third, what should the evaluation strategy be, and how would it differ from that of a patient with conventional GB calculi? Complications associated with residual gallstones are more frequent than with routine GB calculi. Choledocholithiasis is found to occur in 3.4% to 5.2% of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[13,14] However, we discovered that 30.7% of our patients with residual GB had common duct stones. Other gallstone-related complications that our patient cohort experienced were cholecystitis, GB perforation and Mirizzi syndrome. With residual GB, there have been isolated reports of bile duct stricture and malignancy.[15] As a result, unlike conventional GB calculi, residual GB calculi are more likely to cause complications (53.8% in our cohort). In management, they require additional evaluation like MRCP. According to some reports, endoscopic USG may also be used as part of the diagnostic process; it has a sensitivity of around 96.2% and a specificity of around 88.9%.[16] Gupta et al. went on to classify the residual GB into anatomical types based on what they saw on the MRCP and developed a treatment strategy.[15] For cystic duct stump stones, they suggested an endoscopic method, and for a GB pouch or a sessile GB, a surgical approach. Endoscopic extraction of residual GB calculi and the use of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy to crush the calculi have also been reported.[17,18] However, we agree with Singh et al. that this will not address the underlying source of the pathology and that a completion cholecystectomy is required.[12]

In a nationwide survey, IOC was found to be used in <5% of conventional cholecystectomy operations.[19] More than half of the respondents never performed an IOC in a conventional cholecystectomy. However, in the scenario of residual GB, given the higher incidence of choledocholithiasis and the risk of bile duct injury, the use of IOC was much more frequent in our cohort (61.5%). A patient with a failed cholangiography presented with a retained CBD stone on the fifth post-operative day (vide supra). As a result, a cholangiogram, either an ERC or an IOC, can rule out a CBD stone and is crucial in the management of these individuals.

Fourth, what should be the operative strategy in these cases? Biliary fistula is reported to occur in 9%–12% of cases after subtotal cholecystectomy.[20,21] As a result, nearby structures such as the transverse colon and the duodenum form dense adhesions to the residual GB, making adhesiolysis and separation of the critical structures difficult. Thus, these patients are more likely to require a conversion to open surgery. Singh et al. performed elective open surgery in 48% of the patients and conversion to open surgery from laparoscopy in 20% of the patients in the largest report on residual GB to date.[12] Similarly, Gupta et al. reported that open surgery was performed on the majority of their patients (18/21).[15] However, centres with advanced laparoscopy have found that in the vast majority of cases, the surgery can be completed laparoscopically.[8,22]

The following strategies helped us complete the procedure laparoscopically:

Use of an additional (fifth) port: The advantages of the fifth port are fourfold. First, it aids in retraction of the duodenum and colon, enabling a better view of the Hartmann's pouch and the Calot's region. Second, placement of gauze with retraction prevents trauma or injury to critical structures. Third, it makes cholangiogram simple to perform. During IOC, the right mid-clavicular port serves as the access point for the cholangiogram catheter and clamp. The instrument passed through the fifth port helps in the retraction of the Hartmann's pouch for the easy passage of the cholangiogram catheter into the cystic duct. Finally, it improves the ergonomics of CBD suturing and exploration and, if necessary, suturing of the remaining GB or cystic duct

Use of established adhesiolysis techniques: The dissection began with the virgin plane and progressed to the inflamed area. Adhesiolysis in the sub-hepatic region, approaching the GB from the undersurface of segments six and five of the liver, left-to-right from the undersurface of segment four, a top-down approach after identifying the GB, or a 'D2 first' approach as described by us, are the techniques that helped in exposing the GB[6]

Achieving the CVS: Once the inflammation from acute cholecystitis (for which a subtotal cholecystectomy was performed) has subsided, dissecting the Calot's triangle and achieving a CVS (as seen in 12/13) is more often than not possible

Use of intraoperative cholangiogram: This confirmed the anatomy, giving the surgeon confidence in completing the procedure successfully. A real-time, near-infrared fluorescence is a superior modality for the identification of the biliary system. It allows a repeated evaluation in the real-time and helps in preventing bile duct injuries.

Thus, laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy is a safe and feasible approach when the above techniques are utilised as required.

Finally, what are the chances of having a remnant GB after the second surgery? Because of inflammation at the Calot's triangle, the entire residual GB could not be excised in the patient with localised GB perforation. When faced with such a situation, a laparoscopic revision subtotal cholecystectomy with mucosal cauterisation of the remnant following an inside-approach, as described by Hubert et al., and attempting to leave as small a remnant as safely possible are two options for preventing calculi later on.[23] Informing the patient and clear documentation in the operation notes are of paramount importance. A need basis follow-up would be an appropriate strategy in such patients.

CONCLUSION

Gallstones in the residual GB are associated with more complications than conventional gallstones. The diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion. MRCP is more accurate in establishing the diagnosis and identifying the associated complications, even if the diagnosis is made on USG in most patients. A pre-operative roadmap is provided by the MRCP. For patients with residual GB, laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy is a feasible and safe option.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chowbey PK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Mann V, Baijal M, Vashistha A. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: A review of 56 procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2000;10:31–4. doi: 10.1089/lap.2000.10.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrarullah MD, Kacker LK, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK, Kaushik SP. Partial cholecystectomy – Safe and effective. HPB Surg. 1993;7:61–5. doi: 10.1155/1993/52802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Jani K, Shetty AR, Sendhilkumar K, Senthilnathan P, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients: The role of subtotal cholecystectomy and its variants. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elshaer M, Gravante G, Thomas K, Sorge R, Al-Hamali S, Ebdewi H. Subtotal cholecystectomy for “Difficult Gallbladders”: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:159–68. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabour AF, Matsushima K, Love BE, Alicuben ET, Schellenberg MA, Inaba K, et al. Nationwide trends in the use of subtotal cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Surgery. 2020;167:569–74. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadiyaram S, Nachiappan M. Laparoscopic “D2 first” approach for obscure gallbladders. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2021;25:523–7. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Womack NA, Crider RL. The persistence of symptoms following cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1947;126:31–55. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194707000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Jategaonkar PA, Madankumar MV, Anand NV. Laparoscopic management of remnant cystic duct calculi: A retrospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:25–9. doi: 10.1308/003588409X358980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh RM, Ponsky JL, Dumot J. Retained gallbladder/cystic duct remnant calculi as a cause of postcholecystectomy pain. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:981–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar AK, Khandelwal RG, Mathew MJ, Reddy PK. Laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy: A retrospective study of 40 cases. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2013;6:96–9. doi: 10.1111/ases.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed HV, Sherwani AY, Aziz R, Shera AH, Sheikh MR, Lone SN, et al. Laparoscopic completion cholecystectomy for residual gallbladder and cystic duct stump stones: Our experience and review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2021;83:944–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh A, Kapoor A, Singh RK, Prakash A, Behari A, Kumar A, et al. Management of residual gall bladder: A 15-year experience from a north Indian tertiary care centre. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22:36–41. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2018.22.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239:28–33. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000103069.00170.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemli JM, Arnot RS, Ashworth JJ, Curtin AM, Simon RA, Townend DM. Feasibility of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration in a rural centre. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:979–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta V, Sharma AK, Kumar P, Gupta M, Gulati A, Sinha SK, et al. Residual gall bladder: An emerging disease after safe cholecystectomy. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2019;23:353–8. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2019.23.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filip M, Saftoiu A, Popescu C, Gheonea DI, Iordache S, Sandulescu L, et al. Postcholecystectomy syndrome – An algorithmic approach. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shelton JH, Mallat DB. Endoscopic retrograde removal of gallbladder remnant calculus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:272–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benninger J, Rabenstein T, Farnbacher M, Keppler J, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of gallstones in cystic duct remnants and Mirizzi syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buddingh KT, Hofker HS, ten Cate Hoedemaker HO, van Dam GM, Ploeg RJ, Nieuwenhuijs VB. Safety measures during cholecystectomy: Results of a nationwide survey. World J Surg. 2011;35:1235–41. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jara G, Rosciano J, Barrios W, Vegas L, Rodríguez O, Sánchez R, et al. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: A surgical alternative to reduce complications in complex cases. Cir Esp. 2017;95:465–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dijk AH, Donkervoort SC, Lameris W, de Vries E, Eijsbouts QA, Vrouenraets BC, et al. Short-and long-term outcomes after a reconstituting and fenestrating subtotal cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chowbey P, Soni V, Sharma A, Khullar R, Baijal M. Residual gallstone disease – Laparoscopic management. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:220–5. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hubert C, Annet L, van Beers BE, Gigot JF. The “inside approach of the gallbladder” is an alternative to the classic Calot's triangle dissection for a safe operation in severe cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2626–32. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]