Abstract

Introduction:

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) is an essential therapeutic procedure with a significant risk of complications. Data regarding the complications and predictors of adverse outcomes such as mortality are scarce, especially from India and Asia. We aimed to look at the incidence and outcome of complications in ERCP patients.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of all the patients who underwent ERCP and had a complication from January 2012 to December 2018. Data were recorded in predesigned pro forma. The data analysis was done by appropriate statistical tests.

RESULTS:

A total of 17,163 ERCP were done. A total of 570 patients (3.3%) had complications; perforation (n = 275, 1.6%) was most common followed by pancreatitis (n = 177, 1.03%) and bleeding (n = 60, 0.35%). The majorities of perforations were managed conservatively (n = 205, 74.5%), and 53 (19%) required surgery. Overall, 69 (0.4%) patients died. Of these, 30 (10.9%) patients died with perforation. Age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.04, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.005–1.07) and need of surgery (OR: 5.11, 95% CI: 1.66–15.77) were the predictors of mortality in patients with perforation. The majority pancreatitis were mild (n = 125, 70.6%) and overall mortality was 5.6% (n = 10).

Conclusion:

ERCP complications have been remained static over the years, with perforation and pancreatitis contributing the most. Most perforations can be managed conservatively with good clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Bleeding, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, outcome, over-the-scope-clip, pancreatitis, perforation, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has evolved from a diagnostic procedure to a therapeutic procedure for biliary and pancreatic diseases. Despite the evolution of techniques, technology and accessory related to ERCP, the overall complication and mortality rate of ERCP has been stable over time, with an average incidence of complications of 6.85% and mortality over 0.35% population.[1,2,3,4] Although ERCP is a relatively safe and effective procedure, it is still a technically challenging procedure with a significant learning curve.[5] Furthermore, ERCP's ever-expanding horizon for therapeutics in many pancreaticobiliary diseases attracts a certain amount of risk for complications. Electrocautery is now part and parcel of ERCP procedure and invites due amount of risks such as perforation and bleeding. As ERCP has become the standard of care for many pancreaticobiliary ailments, management of its complications is part of learning it. With the evolution of ERCP, management and outcome of complications have also been changed over a period of time.[6] There is a scarcity of post-ERCP complications data from this part of the world, especially from India.

We aimed to share our own experience of post-ERCP complications, their incidence and outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of the patients who underwent ERCP at the Department of Gastroenterology, GIPMER, New Delhi from January 2012 to December 2018. In the event of complications, the data were recorded in predesigned pro forma. All patients with any complications direct or indirectly related to ERCP procedure or sedation were included in the study.

Baseline evaluation prior to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography

Before undergoing ERCP, all patients were evaluated clinically, and investigations, including haemogram, liver function tests, kidney function tests, coagulation profile, chest X-ray and electrocardiogram, were done. The radiological investigations such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, MRCP and endoscopic ultrasound were done as needed. The ERCP was performed by the trainers; trainees were allowed to do basic ECRPs procedures under the supervision of the trainer. All the procedures were done after obtaining the written informed consent from the patient. ERCP was done as a daycare procedure and in high-risk cases as an in-patient. ERCP was performed under conscious sedation; intravenous midazolam and propofol were used for sedation. A trained nursing assistant gave the sedation under supervision. The patients in whom ERCP could not be done under conscious sedation underwent the procedure in general anaesthesia. A trained nurse and a trainee doctor monitored patients throughout the procedure. The standard ERCP techniques were used in all cases. In the case of standard wire-guided cannulation failure, the precut fistulotomy with a needle knife was done to gain access into the desired duct.

Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography management

All patients were monitored post procedure, asymptomatic patients were explained in detail about the procedure-related complications and discharged with the advice to come to the emergency department in case of any complaints. All patients with suspected complications were hospitalised immediately and were evaluated further as needed. All complications were diagnosed, and their severity was classified as per the ASGE definition and diagnostic criteria.[7] The patients with post-ERCP complications post admission were followed till the time of discharge or death. All patients with post-ERCP complications were treated as per standard protocol [Provided in Supplementary Files].

Statistical analysis

All data from pro forma were compiled and each subgroup of complications was then analysed in detail. Overall incidence, outcome and baseline characteristics were noted, and each subgroup data were then subjected to analysis for predictors of the outcome if any.

Statistical Products and Services Solution (SPSS) software version 23.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Continuous data were expressed as mean with standard deviation. Categorical data were represented as percentages and counts. The statistical significance threshold was set at P < 0.05. Univariate analysis was done by Student's t-test and Chi-square test for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Multivariate analysis was carried out using a logistic regression model, and the odds ratio was calculated for significant factors predicting the occurrence of ERCP-related complications.

RESULTS

A total of 17,163 ERCP procedures were done during the study period, of which 570 patients (3.3%) had ERCP-related complications [Tables 1 and 2]. The most common complication was perforation (n = 275, 1.6%), followed by post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) (n = 177, 1.03%) and post sphincterotomy bleeding (n = 60, 0.35%). Overall, 69 (0.4%) patients died due to ERCP-related complications.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with complications

| Baseline characteristic | n (%/SD) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 432 (78.7) | - |

| Age (years) | 46.1±15 | 44.9-47.4 |

| HB (g/dl) | 11±1.8 | 10.8-11.2 |

| TLC (cells/mm3) | 9997±4924 | 9531-10462 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 5.2±7.4 | 4.5-5.9 |

| SGOT (U/L) | 72±68 | 65.6-78.4 |

| SGPT (U/L) | 66±70 | 59.4-72.6 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 285±312 | 255.5-314.5 |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 25±13 | 23.8-26.2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8±0.3 | 0.77-0.83 |

| INR | 1.1±0.2 | 1.08-1.12 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 10.7±9.1 | 9.8-11.6 |

SD: Standard deviation, CI: Confidence interval, HB: Haemoglobin, TLC: Total leucocyte count, SGOT: Serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, SGPT: Serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, ALP: Alkaline phosphatase, INR: International normalised ratio

Table 2.

Complications during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography

| Type of complications | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 17163 |

| Overall complication | 570 (3.3) |

| Perforation | 275 (1.6) |

| Pancreatitis | 177 (1) |

| Perforation plus pancreatitis | 5 (0.02) |

| Bleeding | 60 (0.35) |

| Infection | 14 (0.08) |

| Cerebro-cardiovascular events | 23 (0.13) |

| Basket impaction | 5 (0.02) |

| Miscellaneous | 11 (0.06) |

| Deaths | 69 (0.4) |

The mean age of patients was 46.1 years (95% confidence interval [CI]-44.9–47.4) and 429 (75%) were female. The indications of ERCP were benign in majority patients (n = 449, 78%) and malignant in rest of the patients (n = 121, 21%); among benign aetiology, indications for ERCP were choledocholithiasis (n = 359, 63%), benign biliary stricture (n = 33, 5.7%), choledochal cyst (n = 24, 4.2%) and chronic pancreatitis (n = 12, 2.1%) and in malignant group, aetiologies were carcinoma gallbladder (n = 76, 13.3%), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 23, 4%), periampullary carcinoma (n = 13, 2.2%), carcinoma pancreas (n = 7, 1.2%) and intrapapillary mucinous neoplasm (n = 2, 0.3%). General anaesthesia was used for 12 (2.10%) patients, while the rest underwent ERCP with conscious sedation. Overall cannulation success rate was 80.86% (n = 461). The mean length of hospital stay in patients was 10.7 days (95% CI: 9.8–11.6 days). Rest of baseline features are given in Table 1.

Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography perforations

There were a total of 275 perforations related to ERCP [Figure 1]. The mean age of patients was 48 (95% CI: 46.2–49.8) years, and 81% were female (n = 222). Majority has undergone ERCP for the benign aetiology (n = 209, 76%), choledocholithiasis being the most common (n = 173, 63%). Malignant aetiology was an indication in 66 patients (24%), with carcinoma gall bladder being the most common (n = 43, 15.6%). The cannulation success rate in the perforation subgroup was 82.90% (n = 228).

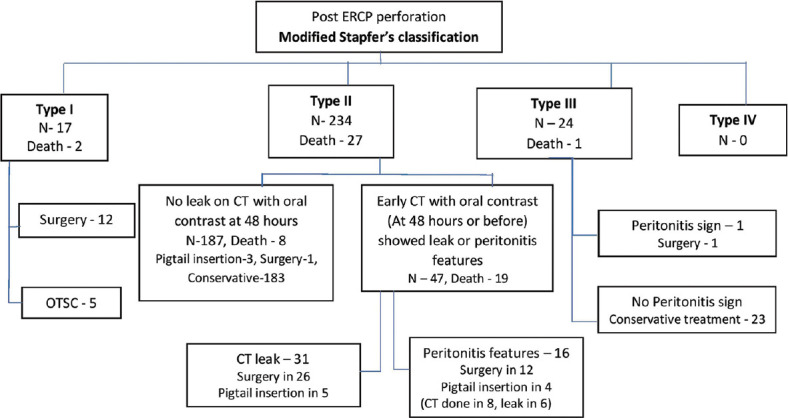

Figure 1.

Flowchart summarising perforation type, management and outcome

The most common type of perforation encountered was Type II (n = 234, 85%), followed by Type III (n = 24, 8.7%), and Type I (n = 17, 6.1%) being the least. Papillotomy (sphincterotomy using sphincterotome) was the cause of the perforation in 149 (54.2%), precut (access sphincterotomy) in 85 (30.9%), scope-induced perforations in 17 (6%) and wire related or during stricture dilatation were the causes in 24 (8.7%) patients. A total of 49 patients (17.81%) had abnormal papilla (ectopic, periampullary diverticulum, downfacing, altered anatomy or small size). Among all, 120 patients (43.63) had difficult cannulation. Of all the perforations, 195 (70.9%) were detected on the table, 55 (20%) were detected within 6 h, 12 (4.4%) were detected between 6 and 24 h and 13 (4.7%) were detected >24 h after the ERCP.

Out of 275 patients with perforation, 205 (74.5%) were managed conservatively, 53 (19%) underwent surgery, 12 (4.3%) were managed with percutaneous drainage and 5 (1.8%) patients with Over-The-Scope-Clip (OTSC, Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tubingen, Germany). In type-wise subgroup analysis, in Type I perforation, 12 (70%) underwent surgery, and 5 (30%) patients underwent OTSC placement. In Type II perforation, 183 (77%) were managed conservatively, 39 (16.6%) underwent surgery, 12 (5.1%) required antibiotics and percutaneous drain and one required surgery plus a percutaneous drain. In Type III perforation, 23 were managed conservatively, and one required surgery. The mean hospital stay duration was 12.3 days (95% CI: 10.9–13.7) for all perforations. Type of perforation (P = 0.57) and aetiology (P = 0.55) did not influence the length of hospital stay. Fifteen patients of Type II perforation had pneumomediastinum, and one had pneumoscrotum in addition to retroperitoneal air. None of these needed any additional treatment.

Factors predicting mortality in the perforation group

A total of 30 (10.9%) patients died in the perforation group, 17 patients who underwent surgery died and amongst those treated non-surgically died 13 (32% vs. 5.8%, P ≤ 0.001). Of the patients who underwent surgery within 12 h (n = 21), 2 (9%) patients died, those who underwent surgery within 12–24 h (n = 22), 8 (40%) patients died and those who underwent surgery after 24 h (n = 9), 7 (77%) patients died (P ≤ 0.001). Across types of perforation, Type I had two deaths (11%), Type II had 27 deaths (11%), while one death in Type III (4%). Although numbers are high in Type II, this difference did not reach a statistically significant level.

In the Type II perforation group, the presence of a leak on CT or peritonitis features has a tremendous impact on mortality. Those with no leak have only two deaths (1%) out of 187 patients. At the same time, 25 died (57%) out of 47 of whom had a leak or peritonitis features (P < 0.0001).

In univariate analysis, older age (56 vs. 47 years, P = 0.003) and failed ERCP (50% vs. 32%, P = 0.04) are significant predictors of mortality in patients having post-ERCP perforations [Table 3]. The malignant aetiology (13.63% vs. 11.77, P = 0.58) and cholangitis at presentation did not have any effect on mortality.

Table 3.

Perforation outcome-univariate and multivariate analysis of predictive factors

| Risk factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Death | Alive | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 26 (87) | 165 (82) | 0.35 | 3.28 | 0.71-15.09 | 0.12 |

| Age (years) | 56 (51-61) | 47 (45-49) | 0.003 | 1.05 | 1.01-1.08 | 0.006 |

| Hospital stays (days) | 20 (13-27) | 11 (10-12) | 0.000 | 1.04 | 1.008-1.087 | 0.01 |

| HB (g/dL) | 11.4 (10.8-12) | 11 (10.8-11.3) | 0.31 | 1.26 | 0.90-1.76 | 0.17 |

| TLC (cell/mm3) | 10204 (8565-11985) | 9932 (9387-10531) | 0.74 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.82 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 5.8 (3.4-8.5) | 5.5 (4.5-6.6) | 0.85 | 1.05 | 0.91-1.12 | 0.78 |

| Serum ALP (IU/L) | 250 (170-336) | 261 (230-292) | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.96-1.00 | 0.47 |

| Surgery versus Non-surgery | 17 versus 13 | 36 versus 162 | <0.001 | 4.35 | 1.44-13.16 | 0.009 |

| Type I versus II versus III | 2 versus 27 versus 1 | 15 versus 207 versus 23 | 0.93 | 0.21 | 0.13-3.36 | 0.23 |

| Timing of surgery (<12 h versus 12-24 h versus >24 h) | 2 versus 8 versus 7 | 19 versus 15 versus 2 | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| ERCP complete versus incomplete | 14 versus 16 | 166 versus 79 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.18-1.63 | 0.27 |

| Cholangitis versus no cholangitis | 1 versus 29 | 20 versus 225 | 0.34 | 1.10 | 0.08-1.48 | 0.93 |

| Malignancy versus Benign as primary aetiology | 9 versus 21 | 57 versus 188 | 0.41 | 1.68 | 0.28-9.9 | 0.56 |

HB: Haemoglobin, TLC: Total leucocyte count, ALP: Alkaline phosphatase, ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

In multivariate analysis, older age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.005–1.07) and need for surgery (OR: 5.11, 95% CI: 1.66–15.77) were predictors of mortality in patients with ERCP related perforation.

Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography pancreatitis

Post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred in 177 (1.03%) patients. The mean age was 43.5 (40.9–46.0) years, and 148 (83%) patients were female. The severity of pancreatitis was mild in 125 (70.6%) patients, moderately severe in 35 (19.7%) patients and severe in 17 (9.6%) patients. The duration of hospital stay for patients with PEP was 9.5 (95% CI: 8.4–10.6) days. Overall, 10 (5.6%) patients with PEP died; all had severe acute pancreatitis. The predictors for PEP were benign indication for ERCP (n = 156, 88%), age <40 years (n = 68, 38%), difficult cannulation (n = 107, 60.6%) and pancreatic duct (PD) cannulation more than three times (n = 132 patients, 75%). On Univariate analysis, predictors associated with mortality in PEP patients were malignancy (P = 0.003), cholangitis (P ≤ 0.001) and severe acute pancreatitis (p =< 0.001). On multivariate analysis, there were no factors for predicting mortality in PEP patients.

Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography bleeding

Post-ERCP bleeding occurred in 60 (0.35%) patients. The mean age of patients was 42.1 (95%:37.2–47) years, and the duration of hospital stay was 7.7 (95%: 5.9–9.5) days. The early bleeding was seen in 33 (55%) patients and late bleeding in 27 (45%) patients.

Overall, 8 (13%) patients with bleeding died. The bleed was related to endoscopic sphincterotomy in 40 (66%) patients, precut fistulotomy in 9 (15%), balloon sphincteroplasty in 5 (8.3%) and balloon trawling in 5 (8.3%) patients. Thirty-eight (63.3%) patients had risk factors for bleeding; 12 had cholangitis, of which 11 had coagulopathy; 6 patients had portal biliopathy, 12 had systemic hypertension, five had underlying cirrhosis and three patients were on dual antiplatelet drugs which could not be discontinued due to emergent indication.

The severity of the bleeding was mild in 32 (53%), moderate in 12 (20%) and severe in 16 (26%) patients. Overall, 21 patients needed no intervention for controlling the bleeding, 19 patients needed adrenaline injection, eight patients needed balloon tamponade, 12 patients needed electrocoagulation, three patients hemoclip was applied, four patients needed surgery and one needed angioembolisation of the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. The combined modalities were needed in six patients to control the bleed. The 8 (13.3%) patients died due to bleeding; the only predictor of mortality in post-ERCP bleed was surgery.

Infection

Post-ERCP infection occurred in 14 patients (0.08%), with a mean age of 50.6 (95%:41.8–59.4) years; nine were female. The infections were cholangitis (n = 11) patients, cholecystitis (n = 1) and aspiration pneumonitis (n = 1). Overall, four patients died secondary to infection.

Cardio-cerebrovascular events

The cardio-cerebrovascular events were seen in patients (n = 33, 0.13%), the mean age was 49.2 (42.7–55.8) years. The cardio-cerebrovascular events were apnoea (n = 7), stroke (n = 4), sudden cardiac arrest (n = 7), myocardial infarction (n = 3) and arrhythmia (n = 2). The risk factors such as respiratory illness, diabetes, hypertension, previous myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation were present in 12 patients. A total of 12 (36%) patients died due to cardio-cerebrovascular events.

Other complications

The rare complications seen were stone removal basket impaction (n = 5), teeth dislodgement (n = 4), denture impaction (n = 1), mouth guard impaction (n = 1), minor oesophageal mucosal bleed (n = 2), variceal bleeding (n = 1) and stent eroding into duodenal wall (n = 1). The impacted basket was removed endoscopically in two patients, and three had to undergo surgery for basket removal. The dislodged denture was removed from the oesophagus endoscopically, and the impacted mouth guard in the oesophagus was also removed endoscopically. The variceal bleed was controlled endoscopically.

The migrated stent eroding the lateral wall of the duodenum was removed and managed conservatively. A total of 38 patients have documented hypoxia which was treated, and all patients recovered on the table.

DISCUSSION

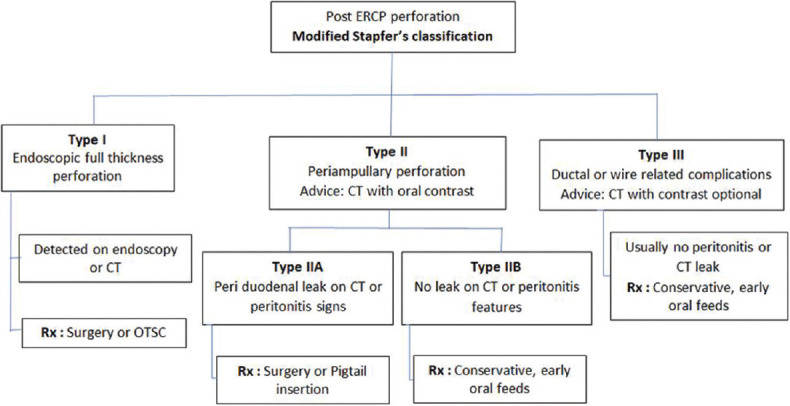

The present study describes the experience from a tertiary care centre over the half-decade about the frequency and outcome of adverse outcomes in patients undergoing ERCP. The present study had an overall complication rate of 3.2% and the mortality rate of 0.4%. Published studies have reported a complication rate between 3.5% to 14% and a mortality rate between 0.4% and 1.4%.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] The overall complication rate and outcome in our study are comparable to previously reported studies. The most common post-ERCP complication was a perforation in the current study, Type II being most common amongst them. Although most common, the incidence of perforation in current data is comparable with published literature.[9] Depending on the mechanism of injury or dynamic clinical markers for managing post-ERCP perforation, the algorithm-based approach has been used in different studies, which is especially useful in Type II perforations.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16] We have also used a modified algorithm, considering that these previous studies have implemented it prospectively as our institutional protocol. As per this algorithm, we suggest doing a CT scan with oral contrast to see a leak in all Type II perforations; if it shows leak or patients have peritonitis features, they can be subtyped into those with a leak (Type IIA) and/or peritonitis and those without it (Type IIB). Type IIA patients should be referred for early surgery, while Type IIB can be managed conservatively with expectant management. In our data, Type IIA has a poor prognosis despite surgery, and delay in surgery further increases mortality [Figure 1]. We also suggest that since Type IV perforation is rare and innocuous, it may be removed from current classifications of post-ERCP perforations [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Modified Stapfer's classification, according to the management protocol

The risk factors associated with poor outcomes in post-ERCP perforations were higher age and the need for surgery. The delay in surgery, especially if done 24 h after perforation, was associated with high (77.8%) mortality. This is in line with the previously has also been reported in the previous studies.[11,12,17] Thus, it is important to do early surgery (within 24 h) in patients who require surgical intervention, usually patients with Type 1 perforation and Type 2 perforation patients with peritonitis or active oral contrast leak on abdominal CT scan. In our study, the delayed diagnosis has led to delayed surgery. The delayed diagnosis in most cases was due to late contact to the hospital and, in few cases, due to a low suspicion index.

In the current study, the rate of post-ERCP pancreatitis incidence was low compared to the previous studies; the possible reasons are the first one we have been using fistulotomy (apex to papilla cutting direction) technique for precut, which recently has shown a low incidence of pancreatitis, second the minimum number of diagnostic ERCP and third as retrospective study possible underreporting of mild pancreatitis cases.[18] Most of the pancreatitis was mild and had a good prognosis. We did not use rectal indomethacin as it was not available during the study period, but we have used prophylactic stenting on a case-to-case basis. All other complications and their outcome were also comparable to previously reported studies.[1,2,3,4,5,6]

There are a few limitations to our study. Although data collection was prospective, the analysis was done retrospectively. As we perform around 50% of ERCP as daycare procedures, there is a possibility of missing patients with mild symptoms who do not report back and those with delayed complications. Due to the retrospective nature and evolving knowledge during the study period, we were also not able to analyse the impact of all risk factors and prophylactic measures, especially on the incidence and outcome of the pancreatitis subgroup. As trainees were also involved in all procedures, it might have altered the complication rate, although published literature says contrary.[19] In addition, we have analysed predictors of outcome according to complication subtype rather than as a whole. This was done as each complication subtype has its own course, so we avoided making conclusions as a whole rather focused on subgroup analysis.

Despite this, current data are the first of its kind from India, with a significant study population. Furthermore, we were able to estimate the incidence and outcome of all ERCP complications.

CONCLUSION

This study provides comprehensive data regarding the real-world incidence of post-ERCP complications and their outcome. This study emphasises that early recognition of perforations requiring surgical intervention should be done by obtaining an early CT with oral contrast to look for contrast leaks. This can avoid delayed surgery and may lead to reduced mortality in these patients. This study may serve as a template for prognostication and management of post-ERCP complications, especially for the perforation in this part of the world.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION LEGENDS

Institutional ERCP Protocol:

Before undergoing ERCP, all patients were evaluated clinically, and investigations, including haemogram, liver function tests, kidney function tests, coagulation profile, chest X-ray and electrocardiogram, were done. Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, MRCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) were done as needed on a case-to-case basis. The ERCP was performed by six expert endoscopists. Since our centre is also a teaching institute, the trainees were also involved actively in ERCP under senior's supervision. ERCP was performed under conscious sedation using intravenous midazolam and propofol. A trained nursing assistant gave the sedation. The patients in whom ERCP could not be done under conscious sedation underwent the procedure in general anaesthesia. A trained nurse and a doctor monitored patients throughout the procedure. The endoscopes used were TJF Q180V (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). All procedures were carried out using standard ERCP techniques. The cannulation was done using wire-guided cannulation technique. In the case of cannulation failure, the endoscopists performed precut fistulotomy with a needle knife during the procedure. This is usually used after three to five inadvertent cannulations of pancreatic duct or more than 10–20 min for routine cannulation. We did not use rectal suppository (diclofenac or indomethacin) as they were not available at the time of study. Pancreatic stent used for prophylaxis in only high-risk cases. Post-ERCP hydration was a routine measure being used during recovery. Precut sphincterotomy and pancreatic septotomy were performed uncommonly, as all the endoscopists were more comfortable with precut fistulotomy. Difficult cannulation was defined as >10–20 min required for cannulation.[7,8]

In case of intraprocedural hypoxia (SpO2<92%), the following steps were:

Scope withdrawal (Temporary termination of procedure)

Venturi mask oxygenation (shifting from nasal cannula to Venturi mask)

Supine or left lateral position

Chin lift jaw thrust manoeuver

If require AMBU bag ventilation.

Post-stabilisation procedure was attempted again to complete if not feasible deferred for another day.

Post ERCP management protocol:

All patients were monitored for 12 h post procedure. After 12 h, asymptomatic patients were explained possible complications and discharged. All patients were asked to visit for a follow-up after 48 h of discharge or before, if any complaint arises. Further follow-up was to be advised as per underlying medical condition and nature of ERCP procedure. All patients with any suspected or proven complications were hospitalised. All complications were defined and diagnosed as per the ASGE definition and diagnostic criteria.[7] Standard classification systems for categorizing a complication and defining its severity were used.

Definitions and classifications of adverse events used (COTTON et al.):

Post ERCP perforations: Post ERCP perforation were defined and classified according to Stapfer classification.[9] (STAPFER) (Type I: Free bowel wall perforation, Type II: RP perforation secondary to periampullary injury, Type III: Perforation of the pancreatic or bile duct, Type IV: Retroperitoneal air alone). For diagnosis endoscopy, fluoroscopy, X-ray and CT scan were used as standalone modality or in combination. Leak detection was done via CT with oral contrast. All patients were treated with standard institutional protocol.[10,11,12,13]

Post ERCP pancreatitis: Modified Cotton's definition described in ASGE guideline was used and severity defined as per Atlanta classification. Standard treatment protocol was followed. Pancreatic duct stenting for prophylaxis was used wherever indicated and plausible. Rectal NSAIDs was not used.

Post ERCP Bleed: Bleeding was defined and categorised into severity as per ASGE criteria.

Other complications: Rest of complications defined according to standard definitions used in literature.

Institutional protocol of ERCP related Perforation management:

A standard institutional protocol was initiated depending on the type of perforation. All patients were immediately admitted to the intensive care unit and were managed with intravenous fluids and IV antibiotics. An abdominal X-ray and/or computed tomography scan of the abdomen with oral contrast was carried out in all patients. A team of surgeons and gastroenterologists evaluated the patient immediately and decided regarding definitive management. Type I perforation patients were treated with strict nil by mouth, Ryle's tube placement with continuous aspiration and immediate intravenous antibiotics. Imipenem and metronidazole combination was started initially and changed accordingly to culture and sensitivity in future.

Type I perforations were immediately subjected to definitive management either by OTSC or surgery. OTSC was available since 2014, so most patients after that were subjected to OTSC if available in house. Type II perforations were guided by clinical signs of peritonism or contrast leak on CT; if anyone of them was present, patients underwent surgery; otherwise; they were managed conservatively. These group of type II perforations patients were kept nil by mouth for 2 days, high-flow oxygen given and monitored closely. After 2 days, CT was done if not earlier with oral contrast to look for leak and collection, if none was present, the patient was allowed orally. Type III perforations were usually managed conservatively (nil by mouth for two days) and CT scan done only in case of peritonism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: A systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1781–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson KD, Perisetti A, Tharian B, Thandassery R, Jamidar P, Goyal H, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complications and their management strategies: A “Scoping” literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:361–75. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang P, Li ZS, Liu F, Ren X, Lu NH, Fan ZN, et al. Risk factors for ERCP-related complications: A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:31–40. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szary NM, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: How to avoid and manage them. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:496–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afridi F, Rotundo L, Feurdean M, Ahlawat S. Trends in post-therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography gastrointestinal hemorrhage, perforation and mortality from 2000 to 2012: A Nationwide Study. Digestion. 2019;100:100–8. doi: 10.1159/000494248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: Report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katsinelos P, Lazaraki G, Chatzimavroudis G, Gkagkalis S, Vasiliadis I, Papaeuthimiou A, et al. Risk factors for therapeutic ERCP-related complications: an analysis of 2,715 cases performed by a single endoscopist. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cirocchi R, Kelly MD, Griffiths EA, Tabola R, Sartelli M, Carlini L, et al. A systematic review of the management and outcome of ERCP related duodenal perforations using a standardized classification system. Surgeon. 2017;15:379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, Katkhouda N, Parekh D, Jabbour N, et al. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg. 2000;232:191–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avgerinos DV, Llaguna OH, Lo AY, Voli J, Leitman IM. Management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: Related duodenal perforations. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:833–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller R, Zbar A, Klein Y, Buyeviz V, Melzer E, Mosenkis BN, et al. Perforations following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A single institution experience and surgical recommendations. Am J Surg. 2013;206:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumbhari V, Sinha A, Reddy A, Afghani E, Cotsalas D, Patel YA, et al. Algorithm for the management of ERCP-related perforations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:934–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin YJ, Jeong S, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Yoo BM, Moon JH, et al. Clinical course and proposed treatment strategy for ERCP-related duodenal perforation: A multicenter analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:806–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Lee SH, Paik WH, Song BJ, Hwang JH, Ryu JK, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients who experienced perforation associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3293–300. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2343-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polydorou A, Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Katsarelias D, Vagianos C, Polymeneas G. A tailored approach to the management of perforations following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2211–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fatima J, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Houghton SG, Iqbal CW, Ott BJ, et al. Pancreaticobiliary and duodenal perforations after periampullary endoscopic procedures: Diagnosis and management. Arch Surg. 2007;142:448–54. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maharshi S, Sharma SS. Early precut versus primary precut sphincterotomy to reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis: Randomized controlled trial (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:586–93. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voiosu T, Boskoski I, Voiosu AM, Benguș A, Ladic A, Klarin I, et al. Impact of trainee involvement on the outcome of ERCP procedures: Results of a prospective multicenter observational trial. Endoscopy. 2020;52:115–22. doi: 10.1055/a-1049-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]