Abstract

After uptake and retrograde transport pertussis toxin acts by ADP-ribosylating α-Gi proteins. We show that uptake via many different receptor proteins followed by retrograde transport and intoxication is not restricted to a particular cell type. The efficiency of cellular intoxication, however, was found to be cell type dependent.

Pertussis toxin (PT), a major virulence factor of Bordetella pertussis, has been shown to interfere with signal transduction proceeding via heterotrimeric G proteins by ADP-ribosylation of α-Gi subunits. Countless studies investigating G proteins and signal transduction mechanisms have taken advantage of this activity. The numerous effects associated with PT during pertussis infections indicate intoxication of different cells in various organs. However, very little is known about potentially specific target cells and the efficiency of PT intoxication in different cell types. Therefore, the aim of the present study was the identification of potential receptors and the characterization of cellular intoxication efficiencies in different cells derived from a variety of human and animal organ sources.

Intoxication by PT.

Cells were incubated with 200 ng of PT (obtained as a kind gift from Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, Lyon, France)/ml for up to 24 h. PT uptake and intoxication of various cell lines derived from animal and human organ sources were investigated by an indirect ADP-ribosylation assay employing radioactively labeled NAD as described previously (3, 7). If PT were routed to its target α-Gi proteins and successfully ADP-ribosylated them during the incubation period, the target proteins would have been blocked for further PT-mediated modification. Incorporation of [32P]ADP ribose in vitro (secondary ADP-ribosylation) serves as a measure for the residual α-Gi subunits available compared to controls without prior PT incubation.

Intoxication of various cell lines.

The decreasing incorporation of [32P]ADP-ribose due to increasing incubation times with PT in culture clearly showed that every cell line investigated in this study is intoxicated following PT uptake. Fig. 1 exemplarily shows the results obtained with 6 of the 14 cell lines investigated during this study.

FIG. 1.

In vitro ADP-ribosylation of α-G proteins extracted from CHO, HFBE, 16 HBE, HeLa, CaCo 2, and CHO-Lec1 cells after preincubation with PT in culture. The target proteins (labeled with [32P]ADP-ribose) were measured by a Bioimager. All assays were done four times. The standard deviations (error bars) are indicated. The values have been normalized to the amount of proteins employed in the assay. The signal obtained in solubilized cells without prior incubation with PT has been set to 100% for each cell line. (A) Short PT incubation of CHO, HFBE, and 16 HBE cells; (B) short PT incubation of HeLa, CaCo 2, and CHO-Lec1 cells; (C) long PT incubation of HeLa, CaCo 2, CHO-Lec1, and CHO cells.

Efficiency of intoxication.

Though PT apparently acts on every cell line in this study, we observed significant differences in uptake and intoxication efficiencies. For instance, in the cells derived from the respiratory tract (HFBE cells, derived from fetal human bronchi; 16 HBE cells, derived from human bronchi) and CHO cells, intracellular target proteins were almost quantitatively modified by PT in a short time (Fig. 1A). These cells were defined as fast responders. Furthermore, pancreas-derived In-R1-G9 and HIT-T15 cells, endothelium-derived bEND3 cells, kidney-derived MDCK cells, brain endothelial cells, and epithelial cells in primary culture were recognized as fast responders (data not shown). In contrast, 5 h of incubation was not sufficient to completely ADP-ribosylate G proteins of CaCo 2 and HeLa cells (Fig. 1B) or H441 cells derived from human lung; thus, these cells were defined as slow-responder cell lines. PT was also able to slowly intoxicate CHO-lec1 cells (Fig. 1B), which is rather surprising as they represent CHO mutants deficient in regular protein glycosylation. These cells thus lack a carbohydrate PT receptor moiety as previously described by Brennan et al. (1).

One might argue that the different intervals necessary for exhaustive modification of the PT target proteins are only due to different amounts of these proteins expressed in different cell lines. To rule out this possibility we directly compared the PT-mediated ADP-ribosylation of target proteins in cellular extracts (with regard to the total protein concentration) with the PT uptake efficiency of the respective cell line. A significant correlation between the totally available target proteins and the ADP-ribosylation efficiency could not be detected. For instance, though CaCo 2 cells harbor only rather low amounts of target proteins to be ADP-ribosylated by PT, the intoxication efficiency is rather poor. On the other hand, HFBE cells are fast responders and are rapidly intoxicated, although they harbor relatively high amounts of available PT target proteins (data not shown). Thus, the efficiency of cellular intoxication does not correlate with the amount of target proteins available.

Modification of α-Gi subunits in slow-responder cells.

To address the question of whether in slow-responder cell lines only a certain fraction of the α-Gi subunits are available for PT modification, we preincubated slow responders, e.g., HeLa, CaCo 2, and CHO-lec1 cells, for up to 24 h with PT, with CHO wild-type cells included as a control. Obviously PT is able to intoxicate slow-responder cells nearly as completely as fast-responder cells (Fig. 1C). However, in CHO-lec1 cells the target G proteins cannot be completely modified by a 24-h incubation with PT. Nevertheless, even in this CHO cell mutant exhibiting aberrant glycosylation a significant PT uptake was observed.

Retrograde transport to the Golgi complex.

As demonstrated previously in pancreas-derived HIT-T15 and In-R1-G9 cells as well as in CHO cells, for productive intoxication PT has to be routed via retrograde transport involving a Golgi passage (3, 7, 8). To investigate whether PT is routed to the Golgi complex also in slow-responder cells, HeLa, CaCo 2, and CHO-lec1 cells (and CHO wild-type cells as controls) were preincubated with brefeldin A (BFA). Though BFA shows additional cellular effects it is mainly known for its Golgi-disrupting activity and has previously been used to analyze retrograde transport of PT as well as of other bacterial and plant toxins (3, 7, 6, 4, 5). In all cell lines tested, BFA treatment (1 μg/ml for 1 h) before incubation with PT for 8 h led to an inhibition of the PT effects (Table 1) as measured by secondary ADP-ribosylation in vitro.

TABLE 1.

Effect of BFA on PT uptake in HeLa, CaCo 2, CHO, and CHO-lec 1 cellsa

| Cell line | % ADP-ribosylation (mean ± SD) for cells

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without PT preincubation

|

With PT preincubation

|

|||

| −BFAb | +BFA | −BFA | +BFA | |

| HeLa | 100 | 67 ± 10 | 5.6 ± 0.96 | 74 ± 11 |

| CaCo 2 | 100 | NDc | 10 ± 2.5 | 107 ± 24 |

| CHO | 100 | 101 ± 14 | 5 ± 1.33 | 95 ± 17 |

| CHO-lec 1 | 100 | 120 ± 8.1 | 41.6 ± 2.1 | 94 ± 14 |

Cultured HeLa, CaCo 2, CHO, and CHO-lec 1 cells were incubated for 1 h with (+) or without (−) BFA (1 μg/ml). Subsequently cells were exposed to PT (200 ng/ml) for 8 h. The preparation of cell extracts and the in vitro ADP-ribosylation assay of G proteins are described in the text. All assays were done four times.

Percent values for ADP-ribosylation of G proteins in experiments without preincubation with BFA and PT were set at 100%.

ND, not determined.

PT-binding proteins.

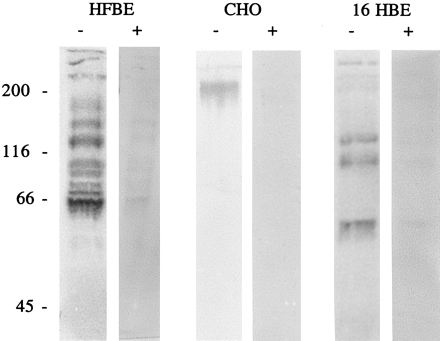

PT-binding proteins mediating S1-dependent effects have thus far been reported as glycoproteins carrying terminal sialic acid moieties solely in pancreas-derived cells (1) and in CHO cells (2). To investigate whether PT-binding proteins are similar, membrane proteins solubilized with n-octylglucoside were tested for PT binding in Western overlay assays. As shown in Fig. 2. PT readily recognizes and binds proteins of fast-responder cells. While we could detect a relatively distinct binding protein (of more than 200 kDa) in CHO cells (as previously shown), a couple of specific PT-binding proteins of different sizes in extracts of HFBE and 16 HBE cells could be identified. However, in three of the four cell lines defined as slow responders (CaCo 2, HeLa, and CHO-lec1 cells) PT-binding proteins were not detectable by this technique. These findings indicate a potential correlation between the expression of PT-binding proteins on the different cell lines and PT intoxication efficiency.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of the binding of PT to solubilized proteins from different cell lines with or without sialidase treatment. Proteins of HFBE cells (amount of protein separated, 27 μg), CHO cells (14 μg), and 16-HBE cells (36 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis after treatment with sialidase (40 μg/ml) or no treatment, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and incubated with PT (1 μg/ml). The blots were probed with the monoclonal anti-S1 antibody 6FX1 and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated second antibodies. Subsequently PT binding was visualized by using nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-inolylphosphate toluidinium (NBT-BCIP). Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left of the gels.

Treatment with sialidase.

As most of the PT-binding proteins described so far carry terminal sialic acid residues, desialylation would affect binding of PT to the various proteins identified in this study. The solubilized proteins were treated with Clostridium perfringens neuraminidase (40 μg/ml) after Western transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Fig. 2). Though treatment with sialidase did not completely abolish protein recognition by PT, it had a significant effect. Residual PT binding might be ascribed to recognition of asialoglycoproteins and/or to nonquantitative desialylation.

Summary.

PT intoxicated every cell type investigated in the present study, including cells with aberrant glycosylation which should not express PT-binding proteins at all. Different PT intoxication efficiencies correlated with differences in the amount of PT-binding proteins detectable on different cells as demonstrated by Western blot analysis. Without prominent PT-binding proteins, intoxication of cells proceeds slowly and not all available α-Gi subunits become ADP-ribosylated. As was previously shown for CHO and pancreas-derived cells (3, 7), PT intoxication is sensitive to the Golgi-disrupting agent BFA in all cells supporting retrograde transport to the Golgi complex as the general mechanism. Thus, uptake of PT does not proceed via a unique binding protein or receptor. The toxin rather takes advantage of binding to a common carbohydrate motif apparently shared by various glycoproteins, in this way enabling intoxication of different cells in different tissues. Use of PT in signal transduction research should be preceded by careful analysis of its particular uptake and intoxication characteristics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brennan M J, David J L, Kenimer J G, Manclark C R. Lectin-like binding of pertussis toxin to a 165-kilodalton Chinese hamster ovary cell glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4895–4899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Bayâ A, Linnemann R, von Olleschik-Elbheim L, Schmidt M A. Identification of binding proteins for pertussis toxin on pancreatic β cell-derived insulin-secreting cells. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(95)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Bayâ A, Linnemann R, von Olleschik-Elbheim L, Robenek H, Schmidt M A. Endocytosis and retrograde transport of pertussis toxin to the Golgi complex as a prerequisite for cellular intoxication. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lencer W I, de Almeida J B, Moe S, Stow J L, Ausiello D A, Madara J L. Entry of cholera toxin into polarized human intestinal epithelial cells. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:2941–2951. doi: 10.1172/JCI116917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orlandi P A, Curran P K, Fishman P H. Brefeldin A blocks the response of cultured cells to cholera toxin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12010–12016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandvig K, Prydz K, Hansen S H, van Deurs B. Ricin transport in brefeldin A-treated cells: correlation between Golgi structure and toxic effect. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:971–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, Barbieri J T. Pertussis toxin-mediated ADP-ribosylation of target proteins in Chinese hamster ovary cells involves a vesicle trafficking mechanism. Infect Immun. 1995;63:825–832. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.825-832.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Y, Barbieri J T. Pertussis toxin-catalyzed ADP-ribosylation of Gi-2 and Gi-3 in CHO cells is modulated by inhibitors of intracellular trafficking. Infect Immun. 1996;64:593–599. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.593-599.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]