Abstract

Cyanosporus is a genus widely distributed in Asia, Europe, North America, South America and Oceania. It grows on different angiosperm and gymnosperm trees and can cause brown rot of wood. Blue-tinted basidiomata of Cyanosporus makes it easy to distinguish from other genera, but the similar morphological characters make it difficult to identify species within the genus. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Cyanosporus were carried out based on worldwide samples with an emphasis on Chinese collections, and the species diversity of the genus is updated. Four new species, C.flavus, C.rigidus, C.subungulatus and C.tenuicontextus, are described based on the evidence of morphological characters, distribution areas, host trees and molecular phylogenetic analyses inferred from the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, the large subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nLSU), the small subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nSSU), the small subunit of mitochondrial rRNA gene (mtSSU), the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB1), the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2), and the translation elongation factor 1-α gene (TEF). Our study expanded the number of Cyanosporus species to 35 around the world including 23 species from China. Detailed descriptions of the four new species and the geographical locations of the Cyanosporus species in China are provided.

Keywords: brown-rot fungi, distribution areas, host trees, multi-gene phylogeny, new species

Introduction

Cyanosporus was proposed as a monotypic genus for Polyporuscaesius (Schrad.) Fr. based on its cyanophilous basidiospores (McGinty 1909). However, Tyromycescaesius (Schrad.) Murrill and Postiacaesia (Schrad.) P. Karst. were frequently used instead of Cyanosporuscaesius (Schrad.) McGinty in subsequent studies (Donk 1960; Jahn 1963; Lowe 1975). Later, four species in the Postiacaesia complex were described from Europe, viz., P.luteocaesia (A. David) Jülich, P.subcaesia (A. David) Jülich, P.alni Niemelä & Vampola and P.mediterraneocaesia M. Pieri & B. Rivoire (David 1974, 1980; Jahn 1979; Pieri and Rivoire 2005). Then, the subgenus Cyanosporus (McGinty) V. Papp was proposed for the species of P.caesia complex (Papp 2014). Miettinen et al. (2018) revised the species concept of the P.caesia complex based on morphology and two gene markers (ITS and TEF) and raised the species number of the complex to 24, including six species from China.

Previously, species identification of the P.caesia complex was only based on morphological characters and host trees in China, and only two species were recorded from China before Dai (2012), viz., P.alni and P.caesia. Recently, taxonomic studies of P.caesia complex in China have been carried out, and some new species have been described based on both morphological characteristics and molecular data. Shen et al. (2019) carried out a comprehensive study on Postia and related genera, in which Cyanosporus was supported as an independent genus with 12 species were accepted in this genus. Liu et al. (2021a) studied the species diversity and molecular phylogeny of Cyanosporus and the number of Cyanosporus species was expanded to 31 around the world, including 19 species from China. These studies have greatly enriched the species of Cyanosporus in China. Currently, the morphological characteristics of the genus are as follows: basidiomata annual, pileate or resupinate to effused-reflexed, soft corky, corky to fragile. Pileal surface white to cream to greyish brown, usually with blue tint. Pore surface white to cream, frequently bluish; pores round to angular. Context white to cream, corky. Tubes cream, fragile. Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae clamped, IKI–, CB–. Cystidia usually absent, cystidioles occasionally present. Basidiospores narrow, allantoid to cylindrical, hyaline, usually slightly thick-walled, smooth, IKI–, weakly CB+.

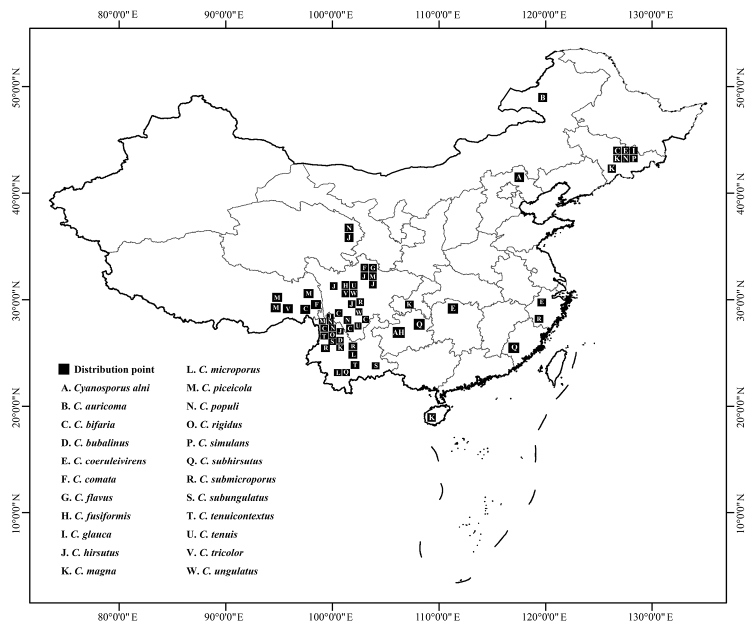

Cyanosporus species usually have blue-tinted basidiomata, which makes it easy to recognize. Some specimens with blue-tinted basidiomata were collected during investigations into the diversity of polypores in China, and four undescribed species of Cyanosporus were discovered. To confirm the affinity of the undescribed species to Cyanosporus, phylogenetic analyses were carried out based on the combined datasets of ITS+TEF and ITS+nLSU+nSSU+mtSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF sequences. During the investigation and study of Cyanosporus, the information of host trees and distribution areas of species in the genus from China were also obtained (Table 1). Four new species are described and illustrated in the current study, and the geographical locations of the Cyanosporus species distributed in China are indicated on the map (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The main ecological habits of Cyanosporus with an emphasis on distribution areas and host trees. New species are shown in bold.

| Species | Distribution in the world | Distribution in China | Climate zone | Host | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C.alni (Niemelä & Vampola) B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | Europe (Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, Poland, Russia, Slovakia), East Asia (China) | Guizhou, Hebei | Temperate | Angiosperm (Alnus, Betula, Corylus, Fagus, Populus, Quercus) | Miettinen et al. 2018; present study |

| C.arbuti (Spirin) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | North America (USA) | Temperate | Angiosperm (Arbutus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.auricomus (Spirin & Niemelä) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (Finland, Poland, Russia), East Asia (China) | Inner Mongolia | Temperate to boreal | Gymnosperm (Pinus, Picea) | Miettinen et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2021a |

| C.bifarius (Spirin) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (Russia), East Asia (China, Japan) | Jilin, Sichuan, Yunnan | Cold temperate | Gymnosperm (Picea, Pinus, Larix) | Miettinen et al. 2018; present study |

| C.bubalinus B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Yunnan | Temperate | Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Liu et al. 2021a |

| C.caesiosimulans (G.F. Atk.) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (Finland, Russia), North America (USA) | Temperate | Angiosperm (Corylus, Fagus, Populus) and gymnosperm (Abies, Picea) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.caesius (Schrad.) McGinty | Europe (Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, UK) | Common in temperate, rare in south boreal zone | Angiosperm (Betula, Fagus, Salix) and gymnosperm (Abies, Picea) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.coeruleivirens (Corner) B.K. Cui, Shun Liu & Y.C. Dai | Asia (China, Indonesia), Europe (Russia) | Hunan, Jilin, Zhejiang | Warm temperate | Angiosperm (Tilia, Ulmus) | Miettinen et al. 2018; present study |

| C.comatus (Miettinen) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | North America (USA), East Asia (China) | Sichuan, Xizang | Temperate | Angiosperm (Acer) and gymnosperm (Abies, Picea, Tsuga) | Miettinen et al. 2018; present study |

| C.cyanescens (Miettinen) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (Estonia, Finland, France, Poland, Russia, Spain, Sweden) | Temperate to Mediterranean mountains | Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea, Pinus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.flavus B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Sichuan | Plateau humid climate | Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea) | Present study |

| C.fusiformis B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Guizhou, Sichuan | North temperate to subtropical | Angiosperm (Rhododendron) | Shen et al. 2019 |

| C.glauca (Spirin & Miettinen) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China), Europe (Russia) | Jilin | Cold temperate mountains | Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea) | Miettinen et al. 2018 |

| C.gossypinus (Moug. & Lév.) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (France) | Temperate | Gymnosperm (Cedrus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.hirsutus B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan | Temperate to plateau continental climate | Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea) | Liu et al. 2021a; present study |

| C.livens (Miettinen & Vlasák) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | North America (Canada, USA) | Temperate | Angiosperm (Acer, Betula, Fagus) and gymnosperm (Abies, Larix, Picea, Tsuga) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.luteocaesius (A. David) B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | Europe (France) | Mediterranean | Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.magnus (Miettinen) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Chongqin, Jilin, Hainan, Yunnan | Temperate | Angiosperm (Populus) and gymnosperm (Cunninghamia) | Miettinen et al. 2018; present study |

| C.mediterraneocaesius (M. Pieri & B. Rivoire) B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | Europe (France, Spain) | Warm temperate to Mediterranean | Angiosperm (Buxus, Erica, Populus, Quercus) and gymnosperm (Cedrus, Juniperus, Pinus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.microporus B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Yunnan | subtropical | Angiosperm (undetermined) | Shen et al. 2019 |

| C.nothofagicola B.K. Cui, Shun Liu & Y.C. Dai | Oceania (Australia), South America (Argentina) | Temperate marine climate | Angiosperm (Nothofagus) | Liu et al. 2021a | |

| C.piceicola B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Sichuan, Xizang, Yunnan | Warm temperate to subtropical | Gymnosperm (Picea) | Shen et al. 2019 |

| C.populi (Miettinen) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China), Europe (Finland, Norway, Poland, Russia), North America (USA) | Qinghai, Jilin, Sichuan, Yunnan | Boreal to temperate | Angiosperm (Acer, Alnus, Betula, Populus, Salix) and gymnosperm (Picea) | Miettinen et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2021a; present study |

| C.rigidus B.K. Cui & Shun | East Asia (China) | Yunnan | Warm temperate | Gymnosperm (Picea) | Present study |

| C.simulans (P. Karst.) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China), Europe (Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, Russia), North America (Canada, USA) | Jilin | Warm temperate to boreal | Angiosperm (Corylus, Fagus, Populus, Sorbus, Ulmus) and gymnosperm (Abies, Cedrus, Juniperus, Picea, Pinus, Thuja, Tsuga) | Miettinen et al. 2018 |

| C.subcaesius (A. David) B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | Europe (Czech Republic, Finland, France, Russia, UK) | Temperate | Angiosperm (Alnus, Carpinus, Crataegus, Corylus, Fagus, Fraxinus, Malus, Populus, Prunus, Quercus, Salix, Ulmus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.subhirsutus B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Guizhou, Fujian, Yunnan | Warm temperate to subtropical | Angiosperm (Pterocarya) | Shen et al. 2019 |

| C.submicroporus B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Sichuan, Yunnan, Zhejiang | Alpine plateau to subtropical | Angiosperm (Alnus, Cyclobalanopsis) | Liu et al. 2021a; present study |

| C.subungulatus B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Yunnan | Subtropical | Angiosperm (undetermined) and gymnosperm (Pinus) | Present study |

| C.subviridis (Ryvarden & Guzmán) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (Finland), North America (Mexico, USA) | Temperate to boreal | Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea, Pinus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 | |

| C.tenuicontextus B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | East Asia (China) | Yunnan | Subtropical | Angiosperm (undetermined) and gymnosperm (Pinus) | Present study |

| C.tenuis B.K. Cui, Shun Liu & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Sichuan | Subtropical monsoon to Alpine plateau | Gymnosperm (Picea) | Liu et al. 2021a |

| C.tricolor B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Sichuan, Xizang | Alpine plateau | Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea) | Shen et al. 2019 |

| C.ungulatus B.K. Cui, L.L. Shen & Y.C. Dai | East Asia (China) | Sichuan | Subtropical monsoon to Alpine plateau | Angiosperm (Castanopsis) and gymnosperm (Abies) | Shen et al. 2019 |

| C.yanae (Miettinen & Kotir.) B.K. Cui & Shun Liu | Europe (Russia) | Temperate continental climate | Gymnosperm (Larix, Pinus) | Miettinen et al. 2018 |

Figure 1.

The geographical locations of the Cyanosporus species distributed in China.

Materials and methods

Morphological studies

The examined specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Institute of microbiology, Beijing Forestry University (BJFC), and some duplicates were deposited at the Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China (IFP) and Southwest Forestry University (SWFC). Macro-morphological descriptions were based on the field notes and measurements of herbarium specimens. Special colour terms followed Petersen (1996). Micro-morphological data were obtained from the dried specimens and observed under a light microscope following Cui et al. (2019) and Liu et al. (2021b). Sections were studied at a magnification up to × 1000 using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and phase contrast illumination (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. Microscopic features, measurements and drawings were made from slide preparations stained with Cotton Blue and Melzer’s reagent. Spores were measured from sections cut from the tubes. To present variation in the size of basidiospores, 5% of measurements were excluded from each end of the range and extreme values are given in parentheses.

In the text the following abbreviations were used: IKI = Melzer’s reagent, IKI– = neither amyloid nor dextrinoid, KOH = 5% potassium hydroxide, CB = Cotton Blue, CB + = cyanophilous, CB – = acyanophilous, L = mean spore length (arithmetic average of all spores), W = mean spore width (arithmetic average of all spores), Q = variation in the L/W ratios between the specimens studied, n (a/b) = number of spores (a) measured from given number (b) of specimens.

Molecular studies and phylogenetic analysis

A cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) rapid plant genome extraction kit-DN14 (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) was used to extract total genomic DNA from dried specimens, and performed the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications as described by Shen et al. (2019) and Liu et al. (2021a). The ITS regions were amplified with primer pairs ITS5 and ITS4 (White et al. 1990). The nLSU regions were amplified with primer pairs LR0R and LR7 (http://www.biology.duke.edu/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm). The nSSU regions were amplified with primer pairs NS1 and NS4 (White et al. 1990). The mtSSU regions were amplified with primer pairs MS1 and MS2 (White et al. 1990). RPB1 was amplified with primer pairs RPB1-Af and RPB1-Cr (Matheny et al. 2002). RPB2 was amplified with primer pairs fRPB2-f5F and bRPB2-7.1R (Matheny 2005). Part of TEF was amplified with primer pairs EF1-983 F and EF1-1567R (Rehner 2001).

The PCR cycling schedule for ITS, mtSSU and TEF included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 54 °C for ITS and mtSSU, 54–55 °C for TEF for 45 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR cycling schedule for nLSU and nSSU included an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for nLSU and 52 °C for nSSU for 1 min, 72 °C for 1.5 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR procedure for RPB1 and RPB2 follow Justo and Hibbett (2011) with slight modifications: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 10 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 60 °C for 40 s and 72 °C for 2 min, then followed by 37 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 1.5 min and 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified and sequenced at Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), China, with the same primers. All newly generated sequences were deposited at GenBank (Table 1).

Additional sequences were downloaded from GenBank (Table 1). All sequences of ITS, nLSU, nSSU, mtSSU, RPB1, RPB2 and TEF were respectively aligned in MAFFT 7 (Katoh and Standley 2013; http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) and manually adjusted in BioEdit (Hall 1999). Alignments were spliced in Mesquite (Maddison and Maddison 2017). The missing sequences were coded as ‘‘N’’. Ambiguous nucleotides were coded as ‘‘N’’. The final concatenated sequence alignment was deposited at TreeBase (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase; submission ID: 29010).

Most parsimonious phylogenies were inferred from the combined 2-gene dataset (ITS+TEF) and 7-gene dataset (ITS+nLSU+nSSU+mtSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF), and their congruences were evaluated with the incongruence length difference (ILD) test (Farris et al. 1994) implemented in PAUP* 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002), under heuristic search and 1000 homogeneity replicates. Phylogenetic analyses approaches followed Liu et al. (2019) and Sun et al. (2020). In phylogenetic reconstruction, the sequences of Antrodiaserpens (Fr.) Donk and A.tanakae (Murrill) Spirin & Miettinen obtained from GenBank were used as outgroups. Maximum parsimony analysis was applied to the combined multiple genes datasets, and the tree construction procedure was performed in PAUP* version 4.0b10. All characters were equally weighted and gaps were treated as missing data. Trees were inferred using the heuristic search option with TBR branch swapping and 1000 random sequence additions. Max-trees were set to 5000, branches of zero length were collapsed and all parsimonious trees were saved. Clade robustness was assessed using a bootstrap (BT) analysis with 1000 replicates (Felsenstein 1985). Descriptive tree statistics tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI) were calculated for each most Parsimonious Tree (MPT) generated. RAxmL v.7.2.8 was used to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) tree with a GTR+G+I model of site substitution including estimation of Gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity and a proportion of invariant sites (Stamatakis 2006). The branch support was evaluated with a bootstrapping method of 1000 replicates (Hillis and Bull 1993). The phylogenetic tree was visualized using FigTree v1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

MrModeltest 2.3 (Posada and Crandall 1998; Nylander 2004) was used to determine the best-fit evolution model for the combined multi-gene dataset for Bayesian inference (BI). Bayesian inference was calculated with MrBayes 3.1.2 with a general time reversible (GTR) model of DNA substitution and a gamma distribution rate variation across sites (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). Four Markov chains were run for 2 runs from random starting trees for 1.8 million generations (ITS+TEF), for 3.5 million generations (ITS+nLSU+nSSU+mtSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF) and trees were sampled every100 generations. The first one-fourth generations were discarded as burn-in. A majority rule consensus tree of all remaining trees was calculated. Branches that received bootstrap support for maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) greater than or equal to 75% (MP and ML) and 0.95 (BPP) were considered as significantly supported, respectively.

Results

Phylogeny

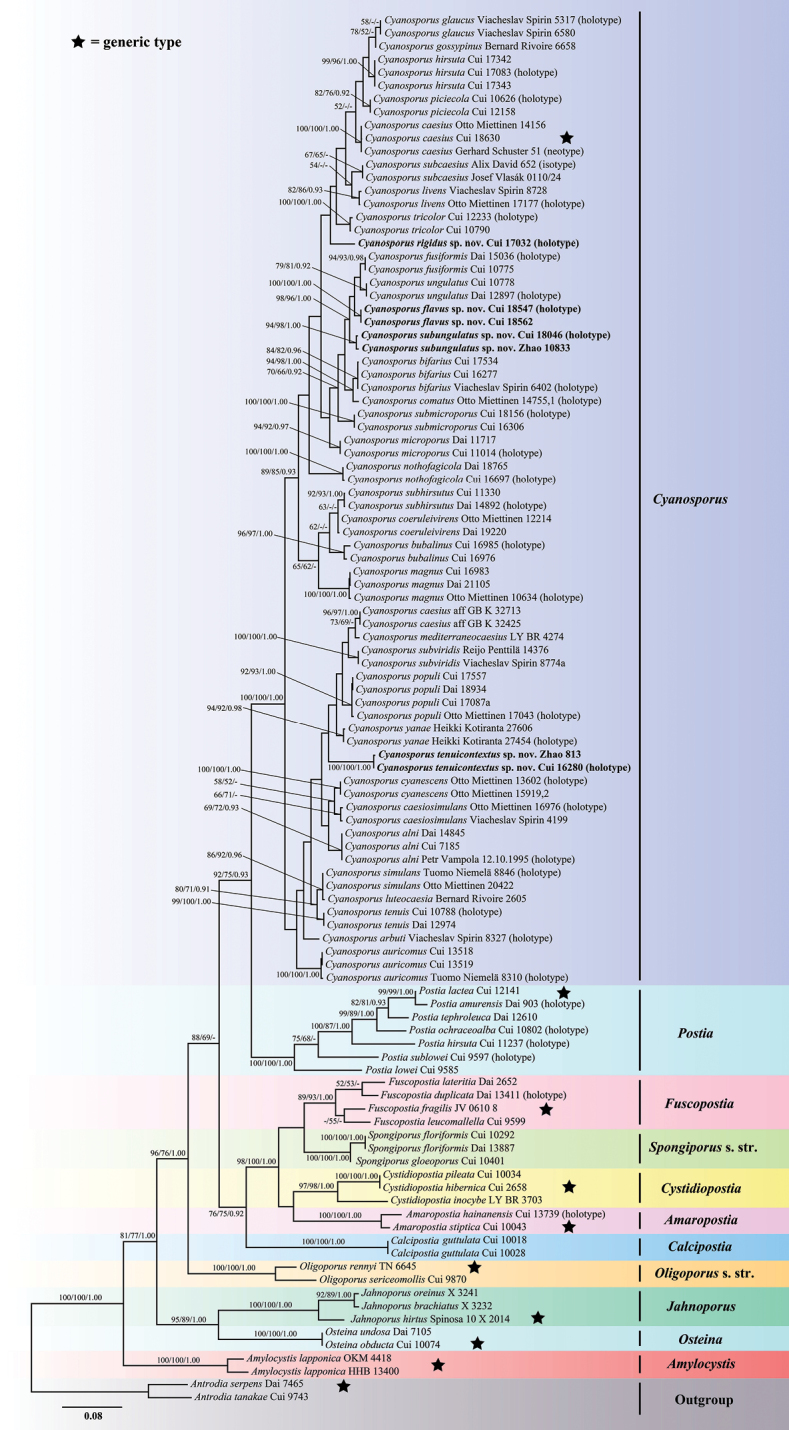

The combined 2-gene (ITS+TEF) sequences dataset had an aligned length of 1015 characters, of which 502 characters were constant, 62 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 451 were parsimony-informative. MP analysis yielded 10 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 2396, CI = 0.379, RI = 0.735, RC = 0.279, HI = 0.621). The best model for the concatenate sequence dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian inference was GTR+I+G with equal frequency of nucleotides. ML analysis resulted in a similar topology as MP and Bayesian analyses, and only the ML topology is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood tree illustrating the phylogeny of Cyanosporus and its related genera in the antrodia clade based on the combined sequences dataset of ITS+TEF. Branches are labelled with maximum likelihood bootstrap higher than 50%, parsimony bootstrap proportions higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities more than 0.90 respectively. Bold names = New species.

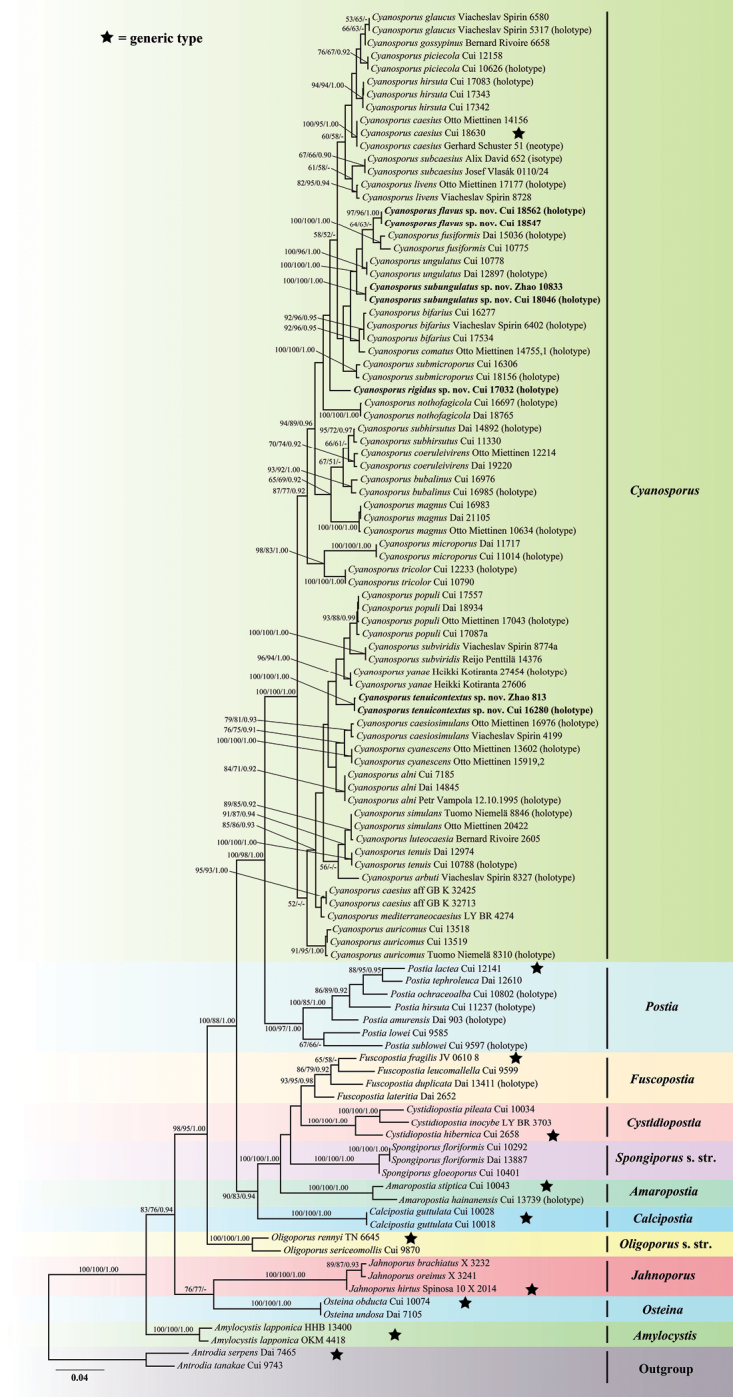

The combined 7-gene (ITS+nLSU+nSSU+mtSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF) sequences dataset had an aligned length of 5634 characters, of which 3843 characters were constant, 247 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 1544 were parsimony-informative. MP analysis yielded 23 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 5756, CI = 0.468, RI = 0.752, RC = 0.352, HI = 0.532). The best model for the concatenate sequence dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian inference was GTR+I+G with equal frequency of nucleotides. ML analysis resulted in a similar topology as MP and Bayesian analyses, and only the ML topology is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood tree illustrating the phylogeny of Cyanosporus and its related genera in the antrodia clade based on the combined sequences dataset of ITS+nLSU+nSSU+mtSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF. Branches are labelled with maximum likelihood bootstrap higher than 50%, parsimony bootstrap propwortions higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities more than 0.90 respectively. Bold names = New species.

The phylogenetic trees inferred from ITS+TEF and ITS+nLSU+nSSU+mtSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF gene sequences were all obtained from 106 fungal samples representing 65 taxa of Cyanosporus and its related genera within the antrodia clade. 74 samples representing 35 taxa of Cyanosporus clustered together and separated from species of Postia and other related genera. As for Cyanosporus, the sequences used in phylogenetic analyses include 28 holotype specimen sequences, one isotype specimen sequence and one neotype specimen sequence (Table 1).

Taxonomy

. Cyanosporus flavus

B.K. Cui & Shun Liu sp. nov.

CC2A2AEE-34B1-5398-A726-C5105333B75F

842319

Figure 4.

Basidiomata of Cyanosporusflavus (Holotype, Cui 18547). Scale bar: 1 cm. The upper figure is the upper surface and the lower figure is the lower surface of the basidiomata.

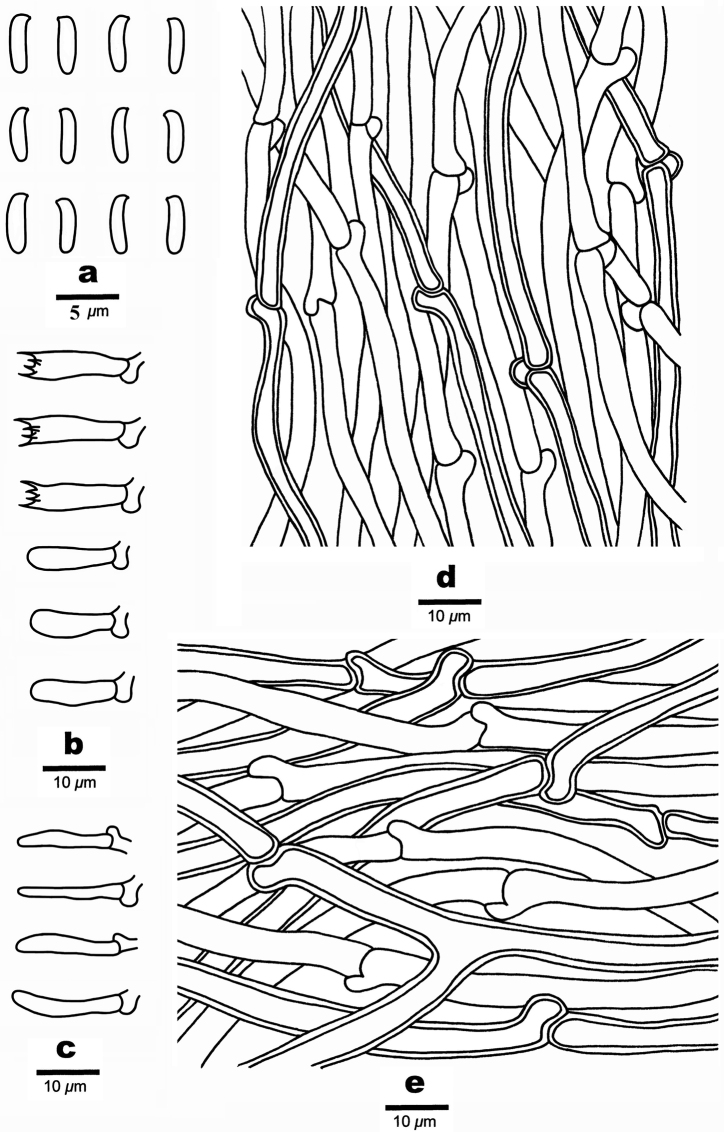

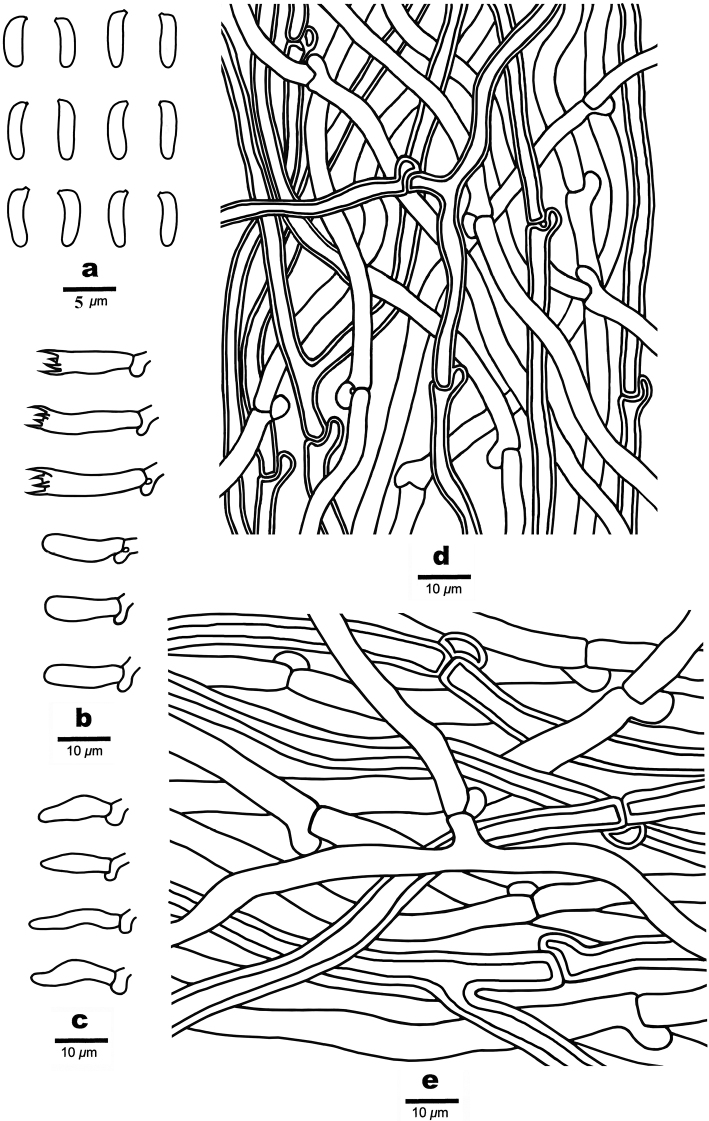

Figure 5.

Microscopic structures of Cyanosporusflavus (Holotype, Cui 18547) a basidiospores b basidia and basidioles c cystidioles d hyphae from trama e hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

Diagnosis.

Cyanosporusflavus is characterised by flabelliform to semicircular and hirsute pileus with ash grey to light vinaceous grey pileal surface when fresh, buff to lemon-chrome pore surface when dry, and allantoid and slightly curved basidiospores (4.6–5.2 × 0.8–1.3 μm).

Holotype.

China. Sichuan Province, Jiuzhaigou County, on stump of Picea sp., 19.IX.2020, Cui 18547 (BJFC 035408).

Etymology.

Flavus (Lat.): referring to its lemon-chrome pore surface when dry.

Fruiting body.

Basidiomata annual, pileate, soft and watery, without odour or taste when fresh, becoming corky to fragile and light in weight upon drying. Pileus flabelliform to semicircular, projecting up to 3.2 cm, 5.7 cm wide and 0.9 cm thick at base. Pileal surface ash-grey to light vinaceous grey when fresh, becoming pale mouse-grey to mouse-grey when dry, hirsute; margin acute to slightly obtuse, white with a little blue tint when fresh, olivaceous buff to greyish brown when dry. Pore surface white to cream when fresh, becoming buff to lemon-chrome when dry; sterile margin narrow to almost lacking; pores angular, 5–7 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire to lacerate. Context white to cream, soft corky, up to 6 mm thick. Tubes pale mouse-grey to ash-grey, fragile, up to 4 mm long.

Hyphal structure.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, IKI–, CB–; hyphae unchanged in KOH.

Context.

Generative hyphae hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, occasionally branched, loosely interwoven, 2.7–6.5 μm in diam.

Tubes.

Generative hyphae hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, rarely branched, interwoven, 2.2–4.7 μm in diam. Cystidia absent; cystidioles present, fusoid, thin-walled, 12.3–17.8 × 2.2–3.5 μm. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 13.2–16.5 × 3.2–5.5 μm; basidioles dominant, in shape similar to basidia, but smaller, 12.6–15.7 × 2.9–5.2 μm.

Spores.

Basidiospores slim allantoid, slightly curved, hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, 4.6–5.2 × 0.8–1.3 μm, L = 5 μm, W = 0.99 μm, Q = 4.96–5.25 (n = 60/2).

Type of rot.

Brown rot.

Additional specimen (paratype) examined.

China. Sichuan Province, Jiuzhaigou County, Jiuzhaigou Nature Reserve, on fallen trunk of Abies sp., 20.IX.2020, Cui 18562 (BJFC 035423).

. Cyanosporus rigidus

B.K. Cui & Shun Liu sp. nov.

C5D8B882-5106-5A28-BA24-A125D6A7D9C1

842320

Figure 6.

Basidiomata of Cyanosporusrigidus (Holotype, Cui 17032). Scale bar: 1.5 cm. The upper figure is the upper surface and the lower figure is the lower surface of the basidiomata.

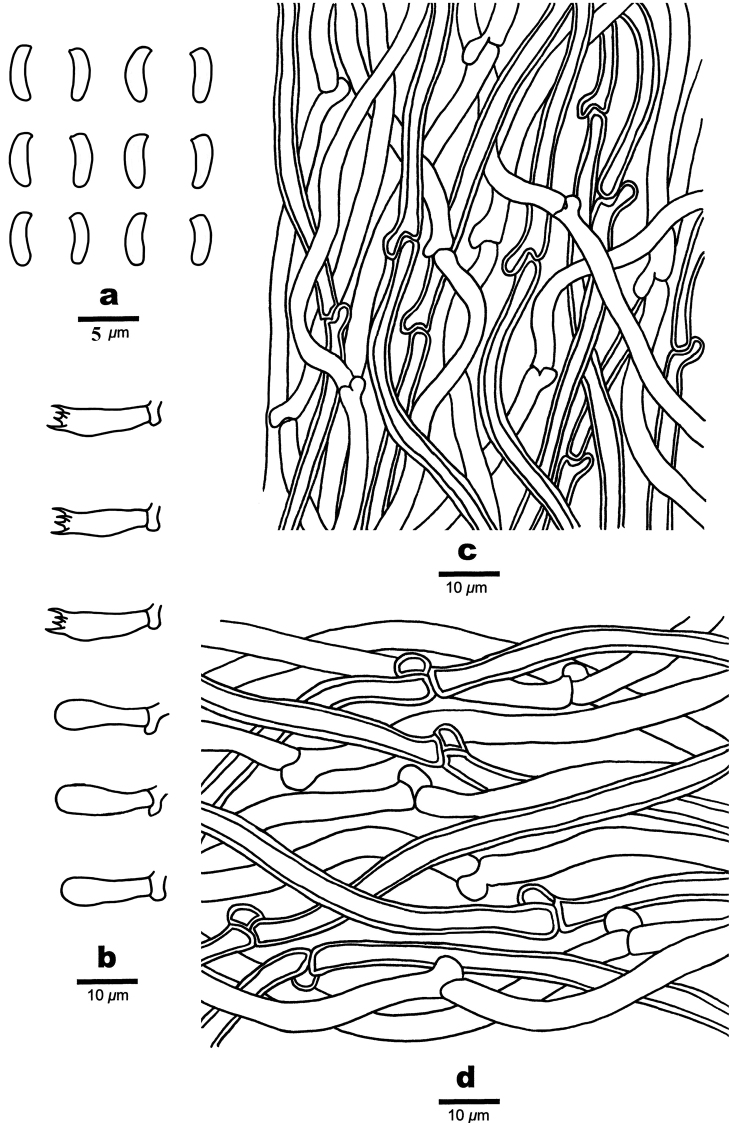

Figure 7.

Microscopic structures of Cyanosporusrigidus (Holotype, Cui 17032) a basidiospores b basidia and basidioles c hyphae from trama d hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

Diagnosis.

Cyanosporusrigidus is characterised by corky, hard corky to rigid basidiomata with a buff yellow to clay-buff and tomentose pileal surface when fresh, becoming olivaceous buff to greyish brown when dry, smaller and cylindrical to allantoid basidiospores (3.7–4.2 × 0.9–1.3 μm).

Holotype.

China. Yunnan Province, Yulong County, Laojun Mountain, Jiushijiu Longtan, on fallen trunk of Abies sp., 15.IX.2018, Cui 17032 (BJFC 030331).

Etymology.

Rigidus (Lat.): referring to the rigid basidiomata.

Fruiting body.

Basidiomata annual, pileate, corky, without odour or taste when fresh, becoming hard corky to rigid upon drying. Pileus flabelliform, projecting up to 1.6 cm, 3.8 cm wide and 0.6 cm thick at base. Pileal surface tomentose, buff yellow to clay-buff, when fresh, becoming smooth, rugose, olivaceous buff to greyish brown when dry; margin obtuse. Pore surface white to cream when fresh, becoming buff-yellow to pinkish buff when dry; sterile margin narrow to almost lacking; pores angular, 5–8 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire to lacerate. Context cream to buff, hard corky, up to 4 mm thick. Tubes cream to pinkish buff, brittle, up to 5 mm long.

Hyphal structure.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, IKI–, CB–; hyphae unchanged in KOH.

Context.

Generative hyphae hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, rarely branched, loosely interwoven, 2.2–5 μm in diam.

Tubes.

Generative hyphae hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, occasionally branched, interwoven, 2–4 μm in diam. Cystidia and cystidioles absent. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 12.4–14.8 × 3–4.2 μm; basidioles dominant, in shape similar to basidia, but smaller, 11.8–13.9 × 2.6–4 μm.

Spores.

Basidiospores allantoid to cylindrical, slightly curved, hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (3.5–)3.7–4.2 × (0.8–)0.9–1.3(–1.4) μm, L = 3.94 μm, W = 1.09 μm, Q = 3.66 (n = 60/1).

Type of rot.

Brown rot.

. Cyanosporus subungulatus

B.K. Cui & Shun Liu sp. nov.

803D7DD9-C55D-568E-9E1A-5F69573F850D

842321

Figure 8.

Basidiomata of Cyanosporussubungulatus (Holotype, Cui 18046). Scale bar: 10 mm. The upper figure is the upper surface and the lower figure is the lower surface of the basidiomata.

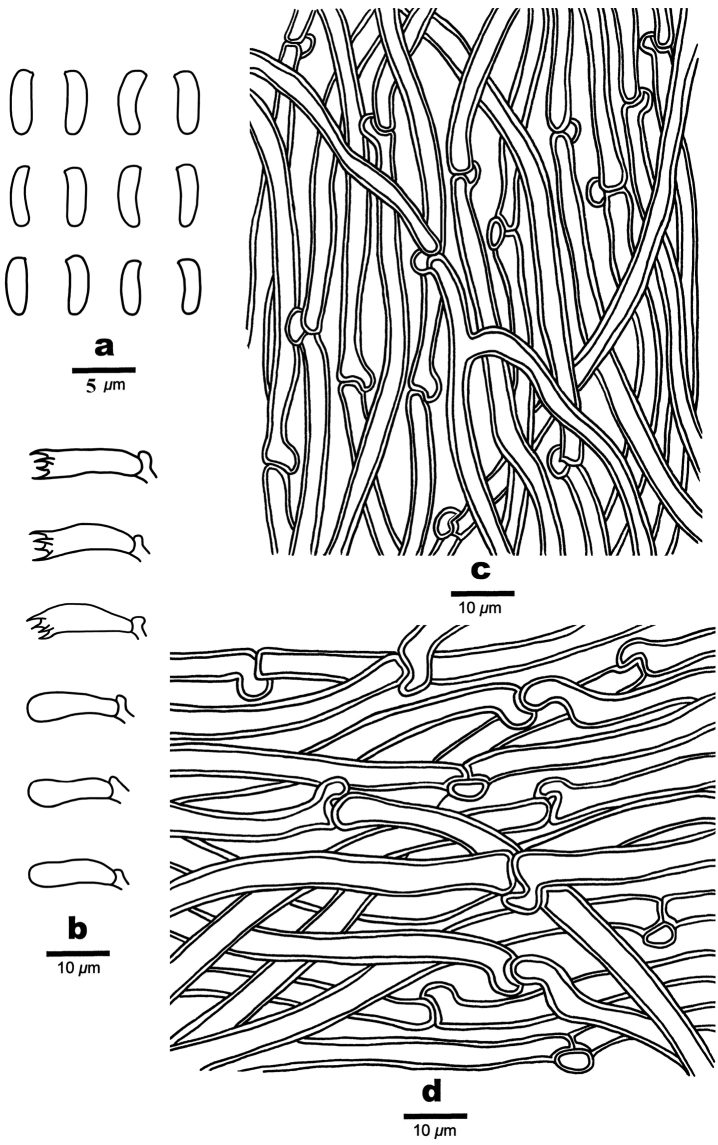

Figure 9.

Microscopic structures of Cyanosporussubungulatus (Holotype, Cui 18046) a basidiospores b basidia and basidioles c hyphae from trama d hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

Diagnosis.

Cyanosporussubungulatus is characterised by shell-shaped pileus with a pale mouse-grey to ash-grey pileal surface when fresh, dark-grey to mouse-grey when dry, allantoid to cylindrical and slightly curved basidiospores (4.5–5.2 × 1.1–1.4 μm).

Holotype.

China. Yunnan Province, Yangbi County, Shimenguan Nature Reserve, on fallen trunk of Pinus sp., 6.IX.2019, Cui 18046 (BJFC 034905).

Etymology.

Subungulatus (Lat.): referring to the species resembling Cyanosporusungulatus in morphology.

Fruiting body.

Basidiomata annual, pileate, soft corky, without odour or taste when fresh, becoming corky to fragile and light in weight upon drying. Pileus shell-shaped, projecting up to 1.7 cm, 2.8 cm wide and 1.2 cm thick at base. Pileal surface velutinate, pale mouse-grey to ash-grey when fresh, becoming smooth, rugose, dark-grey to mouse-grey when dry; margin obtuse. Pore surface white to cream when fresh, becoming cream to pinkish buff when dry; sterile margin narrow to almost lacking; pores round, 4–6 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire to lacerate. Context white to cream, soft corky, up to 5 mm thick. Tubes pale mouse-grey to ash-grey, fragile, up to 6 mm long.

Hyphal structure.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, IKI–, CB–; hyphae unchanged in KOH.

Context.

Generative hyphae hyaline, slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, rarely branched, loosely interwoven, 2.5–6.4 μm in diam.

Tubes.

Generative hyphae hyaline, slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, occasionally branched, interwoven, 2–4.2 μm in diam. Cystidia and cystidioles absent. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 13.6–17.8 × 3–5.5 μm; basidioles dominant, in shape similar to basidia, but smaller, 12.8–17.2 × 2.4–5.2 μm.

Spores.

Basidiospores allantoid to cylindrical, slightly curved, hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (4.3–)4.5–5.2 × 1.1–1.4 μm, L = 4.73 μm, W = 1.22 μm, Q = 3.48–3.66 (n = 60/2).

Type of rot.

Brown rot.

Additional specimen (paratype) examined.

China, Yunnan Province, Xichou County, Xiaoqiaogou Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 14.I.2019, Zhao 10833 (SWFC 010833).

. Cyanosporus tenuicontextus

B.K. Cui & Shun Liu sp. nov.

6A2E6771-2883-597D-9041-F2C47FA6B3E9

842323

Figure 10.

Basidiomata of Cyanosporustenuicontextus (Holotype, Cui 16280). Scale bar: 1 cm. The upper figure is the upper surface and the lower figure is the lower surface of the basidiomata.

Figure 11.

Microscopic structures of Cyanosporustenuicontextus (Holotype, Cui 16280) a basidiospores b basidia and basidioles. c cystidioles d hyphae from trama e hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

Diagnosis.

Cyanosporustenuicontextus is characterised by flabelliform pileus with a velutinate, cream to pinkish buff with a little blue tint pileal surface when fresh, becoming glabrous, light vinaceous grey to pale mouse-grey when dry, small and round pores (6–8 per mm), thin context (up to 0.8 mm) and allantoid basidiospores (3.8–4.3 × 0.8–1.2 μm).

Holotype.

China. Yunnan Province, Lanping County, Tongdian Town, Luoguqing, on fallen trunk of Pinus sp., 19.IX.2017, Cui 16280 (BJFC 029579).

Etymology.

Tenuicontextus (Lat.): referring to the species having thin context.

Fruiting body.

Basidiomata annual, pileate, soft corky, without odour or taste when fresh, becoming corky to fragile and light in weight upon drying. Pileus flabelliform, projecting up to 1.3 cm, 3.2 cm wide and 0.5 cm thick at base. Pileal surface velutinate, cream to pinkish buff with a little blue tint when fresh, becoming glabrous, light vinaceous grey to pale mouse-grey when dry; margin acute. Pore surface white to cream when fresh, becoming pinkish buff to buff when dry; sterile margin narrow to almost lacking; pores round, 6–8 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire to lacerate. Context cream to buff, soft corky, up to 0.8 mm thick. Tubes pale mouse-grey to buff, fragile, up to 4.3 mm long.

Hyphal structure.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, IKI–, CB–; hyphae unchanged in KOH.

Context.

Generative hyphae hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, occasionally branched, loosely interwoven, 2.3–5.5 μm in diam.

Tubes.

Generative hyphae hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled with a wide lumen, occasionally branched, interwoven, 2–4 μm in diam. Cystidia absent; cystidioles present, fusoid, thin-walled, 9.5–14.6 × 2.8–3.4 μm. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 11.7–16.8 × 3.4–4.3 μm; basidioles dominant, in shape similar to basidia, but smaller, 10.6–14.7 × 2.9–3.6 μm.

Spores.

Basidiospores allantoid, slightly curved, hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (3.7–)3.8–4.3 × 0.8–1.2 μm, L = 3.97 μm, W = 1.02 μm, Q = 3.78–4.26 (n = 60/2).

Type of rot.

Brown rot.

Additional specimen (paratype) examined.

China. Yunnan Province, Yuxi, Xinping County, Mopanshan National Forest Park, on angiosperm stump, 16.I.2017, Zhao 813 (SWFC 000813).

Discussion

In the current phylogenetic analyses based on the combined datasets of ITS+TEF and ITS+nLSU+mtSSU+nSSU+RPB1+RPB2+TEF sequences, species of Cyanosporus formed a highly supported lineage, distant from Postia and other brown-rot fungal genera (Figs 2, 3) and consistent with previous studies (Shen et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2021a). Based on morphological characters and phylogenetic analyses, 35 species are accepted in Cyanosporus around the world, including four new species from China, viz., C.flavus, C.rigidus, C.subungulatus and C.tenuicontextus. The main ecological habits of the species in Cyanosporus with an emphasis on distribution areas and host trees are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

A list of species, specimens, and GenBank accession number of sequences used for phylogenetic analyses in this study.

*Newly generated sequences for this study. New species are shown in bold.

In the phylogenetic trees, Cyanosporusflavus grouped together with C.fusiformis, C.subungulatus and C.ungulatus (Figs 2, 3). Cyanosporusfusiformis differs from C.flavus by having white to cream pileal surface when fresh, clay-buff pore surface when dry and larger pores (4–5 per mm) and by growing on angiosperm woods (Shen et al. 2019); C.subungulatus differs from C.flavus in its glabrous pileal surface, cream to pinkish buff pore surface when dry and wider basidiospores (4.5–5.2 × 1.1–1.4 μm); C.ungulatus differs from C.flavus by having ungulate basidiomata, sulcate pileal surface with olivaceous buff, pinkish buff, cream to ash-grey and white zones when fresh (Shen et al. 2019). Cyanosporushirsutus and C.subhirsutus have pileate basidiomata with hirsute, blue tint to the pileal surface and slightly thick-walled basidiospores like C.flavus, but C.hirsutus differs by having wider basidiospores (4–4.7 × 1.2–1.5 μm; Liu et al. 2021a), while C.subhirsutus has larger pores (2–3 per mm; Shen et al. 2019). Besides, C.hirsutus and C.subhirsutus are distant from C.flavus in the phylogenetic analyses (Figs 2, 3). Cyanosporussubungulatus and C.ungulatus share similar pores and basidiospores; however, C.ungulatus differs by having ungulate basidiomata, glabrous and sulcate pileal surface, narrower context hyphae and tramal hyphae (Shen et al. 2019).

Phylogenetically, Cyanosporusrigidus form a separate lineage different from other species in the genus. Morphologically, C.submicroporus share similar pores and basidiospores with C.rigidus, but C.submicroporus differs by having cream to pinkish buff pileal surface and white to smoke grey pore surface when fresh, buff to buff-yellow pileal surface and buff to olivaceous buff pore surface when dry. Cyanosporusauricomus and C.luteocaesius resemble C.rigidus in morphology by producing yellow-colored basidiomata, but C.auricomus differs from C.rigidus by having a hirsute pileal surface and larger basidiospores (4.4–5.6 × 1.5–1.8 μm; Miettinen et al. 2018); C.luteocaesius differs from C.rigidus by having larger pores (3–5 per mm) and basidiospores (4.3–6.1 × 1.5–1.9 μm; Miettinen et al. 2018).

Phylogenetically, C.tenuicontextus is closely related to C.caesiosimulans, C.cyanescens, C.populi, C.subviridis and C.yanae (Figs 2, 3). Morphologically, they share similar pores; but C.caesiosimulans differs by having larger basidiospores (4.2–5.5 × 1.1–1.4 μm), and a wide distribution area (Europe and North America; Miettinen et al. 2018); C.cyanescens differs in having light bluish-greyish tint in older and dry specimens and larger basidiospores (4.7–6.1 × 1.1–1.6 μm; Miettinen et al. 2018); C.populi differs in its larger basidiospores (4.2–5.6 × 1–1.3 μm), and a wide distribution area (East Asia, Europe and North America; Miettinen et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2021a); C.subviridis differs in its conchate basidiomata, distributed in Europe and North America and grows only on gymnosperms (Abies sp., Picea sp. and Pinus sp.; Miettinen et al. 2018); C.yanae differs by having narrower generative hyphae (3–4 μm in context, 2.2–2.9 μm in tubes), larger basidiospores (4.3–5.8 × 1.2–1.6 μm), distributed in Europe and grows only on gymnosperm (Larix sp., Pinus sp.; Miettinen et al. 2018). Cyanosporusbifarius is also distributed in Lanping County, Yunnan Province of China, they share similar pores and basidiospores, but C.bifarius grows only on gymnosperm trees (Picea sp., Pinus sp., Larix sp.; Miettinen et al. 2018), and C.bifarius is distant from C.tenuicontextus in the phylogenetic analyses (Figs 2, 3).

The natural distribution of plant-associated fungi across broad geographic ranges is determined by a combination of the distributions of suitable hosts and environmental conditions (Lodge 1997; Brandle and Brandl 2006; Gilbert et al. 2007, 2008). Species in Cyanosporus have a wide distribution range (Asia, Europe, North America, South America and Oceania; Table 2) and variable host type (angiosperms and gymnosperms). As for distribution ranges, 23 species of Cyanosporus are distributed in Asia, 16 species in Europe, seven species in North America, one species in South America and one species in Oceania. As for host trees, nine species of Cyanosporus grow only on angiosperm trees, 15 species only on gymnosperm trees, and eleven species both on angiosperm and gymnosperm trees (Table 1). In some cases, some Cyanosporus species have host specificity, at least regionally, such as in Europe, C.auricomus only growth on Pinussylvestris, C.cyanescens only growth on Piceaabies, C.populi prefers Populustremula, and C.luteocaesia have been recorded only from Pinus sp. (Miettinen et al. 2018).

In the current study, 77 samples of Cyanosporus throughout China and 11 samples outside of China have been morphologically examined in detail. The specimens collected from China representing 21 species were sequenced here and referred to in our phylogeny, viz., C.alni, C.auricomus, C.bifarius, C.bubalinus, C.coeruleivirens, C.comatus, C.flavus, C.fusiformis, C.hirsutus, C.magnus, C.microporus, C.piceicola, C.populi, C.rigidus, C.subhirsutus, C.submicroporus, C.subungulatus, C.tenuicontextus, C.tenuis, C.tricolor and C.ungulatus. Another two species reported in a previous study, viz., C.glauca (=Postiaglauca Spirin & Miettinen) and C.simulans (=Postiasimulans (P. Karst.) Spirin & Rivoire; Miettinen et al. 2018) were also found from China. Among these Cyanosporus species, 15 are endemic to China so far, viz., C.bubalinus, C.flavus, C.fusiformis, C.hirsutus, C.microporus, C.piceicola, C.rigidus, C.subhirsutus, C.submicroporus, C.subungulatus, C.tenuicontextus, C.tenuis, C.tricolor and C.ungulatus. The Cyanosporus species formed a distribution center in Southwest China. This may be due to the complex and diverse ecological environment and diverse host trees in this region, which provide a rich substrate for the growth of Cyanosporus species. The geographical locations of the Cyanosporus species distributed in China are indicated on the map (Fig. 1).

In summary, we performed a comprehensive study on the species diversity and phylogeny of Cyanosporus with an emphasis on Chinese collections. So far, 35 species are accepted in the Cyanosporus around the world, including 23 species from China. Currently, Cyanosporus is characterized by an annual growth habit, resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate, soft corky, corky, fragile to hard corky basidiomata, velutinate to hirsute or glabrous pileal surface with blue-tinted, white to cream or yellow-colored, white to cream pore surface with round to angular pores, a monomitic hyphal system with clamped generative hyphae, and hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, smooth, narrow, allantoid to cylindrical basidiospores that are usually weakly cyanophilous; it grows on different angiosperm and gymnosperm trees, causes a brown rot of wood and has a distribution in Asia, Europe, North America, Argentina in South America and Australia in Oceania (McGinty 1909; Shen et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2021a).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the curators of herbaria of IFP and SWFC for their loan of specimens. Ms. Yi-Fei Sun (China), Xing Ji (China) and Yan Wang (China) are grateful for help during field collections and molecular studies. Drs. Jun-Zhi Qiu (China), Shi-Liang Liu (China) and Long-Fei Fan (China) are thanked for their companionship during field collections. The research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U2003211, 31750001), the Scientific and Technological Tackling Plan for the Key Fields of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (No. 2021AB004), and Beijing Forestry University Outstanding Young Talent Cultivation Project (No. 2019JQ03016).

Citation

Liu S, Xu T-M, Song C-G, Zhao C-L, Wu D-M, Cui B-K (2022) Species diversity, molecular phylogeny and ecological habits of Cyanosporus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) with an emphasis on Chinese collections. MycoKeys 86: 19–46. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.86.78305

Contributor Information

Dong-Mei Wu, Email: wdm0999123@sina.com.

Bao-Kai Cui, Email: cuibaokai@bjfu.edu.cn.

References

- Brandle M, Brandl R. (2006) Is the composition of phytophagous insects and parasitic fungi among trees predictable? Oikos 113: 296–304. 10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.14418.x [DOI]

- Cui BK, Li HJ, Ji X, Zhou JL, Song J, Si J, Yang ZL, Dai YC. (2019) Species diversity, taxonomy and phylogeny of Polyporaceae (Basidiomycota) in China. Fungal Diversity 97: 137–392. 10.1007/s13225-019-00427-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai YC. (2012) Polypore diversity in China with an annotated checklist of Chinese polypores. Mycoscience 53: 49–80. 10.1007/s10267-011-0134-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David A. (1974) Une nouvelle espèce de Polyporaceae: Tyromycessubcaesius. Bulletin Mensuel de la Société Linnéenne de Lyon 43: 119–126 [Google Scholar]

- David A. (1980) Étude du genre Tyromyces sensu lato: répartition dans les genres Leptoporus, Spongiporus et Tyromyces sensu stricto. Bulletin Mensuel de la Société Linnéenne de Lyon 49: 6–56. 10.3406/linly.1980.10404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donk MA. (1960) The generic names proposed for Polyporaceae. Persoonia 1: 173–302. [Google Scholar]

- Farris JS, Källersjö M, Kluge AG, Kluge AG, Bult C. (1994) Testing significance of incongruence. Cladistics 10: 315–319. 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1994.tb00181.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Confidence intervals on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. (1999) Bioedit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Han ML, Chen YY, Shen LL, Song J, Vlasák J, Dai YC, Cui BK. (2016) Taxonomy and phylogeny of the brown-rot fungi: Fomitopsis and its related genera. Fungal Diversity 80: 343–373. 10.1007/s13225-016-0364-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Bull JJ. (1993) An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Systematics and Biodiversity 42: 182–192. 10.1093/sysbio/42.2.182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn H. (1963) Mitteleuropäische Porlinge (Polyporaceae s. lato) und ihr Vorkommen in Westfalen. Westfälische Pilzbriefe 4: 1–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn H. (1979) Pilze die an Holz Wachsen. Herford: Busse.

- Justo A, Hibbett DS. (2011) Phylogenetic classification of Trametes (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) based on a five-marker dataset. Taxon 60: 1567–1583. 10.1002/tax.606003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. (2013) MAFFT Multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Shen LL, Wang Y, Xu TM, Gates G, Cui BK. (2021a) Species diversity and molecular phylogeny of Cyanosporus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota). Frontiers in Microbiology 12: e631166. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.631166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Han ML, Xu TM, Wang Y, Wu DM, Cui BK. (2021b) Taxonomy and phylogeny of the Fomitopsispinicola complex with descriptions of six new species from east Asia. Frontiers in Microbiology 12: e644979. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.644979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Song CG, Cui BK. (2019) Morphological characters and molecular data reveal three new species of Fomitopsis (Basidiomycota). Mycological Progress 18: 1317–1327. 10.1007/s11557-019-01527-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge DJ. (1997) Factors related to diversity of decomposer fungi in tropical forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 6: 681–688. 10.1023/A:1018314219111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe JL. (1975) Polyporaceae of North America. The genus Tyromyces. Mycotaxon 2: 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. (2017) Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis, Version 3.2. http://mesquiteproject.org

- Matheny PB. (2005) Improving phylogenetic inference of mushrooms with RPB1 and RPB2 nucleotide sequences (Inocybe, Agaricales). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35: 1–20. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny PB, Liu YJ, Ammirati JF, Hall BD. (2002) Using RPB1 sequences to improve phylogenetic inference among mushrooms (Inocybe. Agaricales). American Journal of Botany 89: 688–698. 10.3732/ajb.89.4.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty NJ. (1909) A new genus, Cyanosporus. Mycological Notes 33: e436.

- Miettinen O, Vlasák J, Rivoire B, Spirin V. (2018) Postiacaesia complex (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) in temperate Northern Hemisphere. Fungal Systematics and Evolution 1: 101–129. 10.3114/fuse.2018.01.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander JAA. (2004) MrModeltest v2. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Program distributed by the author.

- Ortiz-Santana B, Lindner DL, Miettinen O, Justo A, Hibbett DS. (2013) A phylogenetic overview of the antrodia clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales). Mycologia 105: 1391–1411. 10.3852/13-051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp V. (2014) Nomenclatural novelties in the Postiacaesia complex. Mycotaxon 129: 407–413. 10.5248/129.407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JH. (1996) Farvekort. The Danish Mycological Society’s colour-chart. Foreningen til Svampekundskabens Fremme, Greve.

- Pieri M, Rivoire B. (2005) Postiamediterraneocaesia, une nouvelle espèce de polypore découverte dans le sud de l’Europe. Bulletin Semestriel de la Fédération des Associations Mycologiques Méditerranéennes 28: 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. (1998) Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14: 817–818. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehner S. (2001) Primers for Elongation Factor 1-a (EF1-a). http://ocid.nacse.org/research/deephyphae/EF1primer.pdf

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. (2003) MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen LL, Wang M, Zhou JL, Xing JH, Cui BK, Dai YC. (2019) Taxonomy and phylogeny of Postia. Multi-gene phylogeny and taxonomy of the brown-rot fungi: Postia (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) and related genera. Persoonia 42: 101–126. 10.3767/persoonia.2019.42.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin V, Vlasák J, Milakovsky B, Miettinen O. (2015) Searching for indicator species of old-growth spruce forests: studies in the genus Jahnoporus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota). Cryptogamie Mycologie 36: 409–418. 10.7872/crym/v36.iss4.2015.409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YF, Costa-Rezende DH, Xing JH, Zhou JL, Zhang B, Gibertoni TB, Gates G, Glen M, Dai YC, Cui BK. (2020) Multi-gene phylogeny and taxonomy of Amauroderma s. lat. (Ganodermataceae). Persoonia 44: 206–239. 10.3767/persoonia.2020.44.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. (2002) PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland.

- Stamatakis A. (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analysis with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vampola P, Ordynets A, Vlasak J. (2014) The identity of Postialowei (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) and notes on related or similar species. Czech Mycology 66: 39–52. 10.33585/cmy.66102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gefand DH, Sninsky JJ, White JT. (Eds) PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications.Academic Press, San Diego, 315–322. 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.