Abstract

Over the last decade, clinical trials using various poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors on patients with ovarian cancer have shown promising results. The introduction of PARP inhibitors has changed the treatment landscape and improved outcomes for patients with ovarian cancer. Fuzuloparib, developed by Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., is a novel orally available small molecule PARP inhibitor. By introducing the trifluoromethyl group into chemical structure, fuzuloparib exhibits higher stability and lower inter-individual variability than other PARP inhibitors. Several clinical trials (FZOCUS series and others) have been carried out to assess the efficacy and safety of fuzuloparib through different lines of treatments for advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer in both treatment and maintenance. Here, we present the most recent data from these studies, discuss current progress and potential future directions.

Keywords: PARP Inhibitor, Fuzuloparib, Ovarian Cancer, Maintenance Therapy

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is one of the commonest gynecological malignancies, with approximately 313,959 new cases and 207,252 deaths worldwide in 2020 [1,2]. About 70% of patients were diagnosed at advanced stages (FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage III or IV), due to the lack of typical symptoms and effective screening methods for detecting early-stage ovarian cancer [3,4]. The five-year survival rate for people diagnosed with advanced stage ovarian cancer is 29% [5]. Although the standard treatment of cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy can be curative for most patients with early-stage ovarian cancer, approximately 70%–80% of patients with advanced disease will have a relapse within 2 years, resulting in the occurrence of platinum resistance and poor survival [4,5].

Poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors exploit faulty DNA repairing mechanisms through synthetic lethality, which will result in genomic instability and tumor cell death [6,7]. As members of the PARP superfamily, PARP1 and PARP2 play an important role in the DNA damage response (DDR) by acting as DNA damage sensors and signal transducers [8]. Oral PARP inhibitors prohibit base excision repair by associating with PARP at sites of DNA damage, resulting in synthetic termination. This mechanism is particularly effective in defective cancer cells during the repair of homologous recombination (HR) [9,10]. Thus, the application of PARP to prevent the DDR has become a novel strategy for cancer therapy. PARP inhibitors increase the formation of PARP-DNA complexes or PARP-DNA capture, this has been considered as one of the anticancer mechanisms of PARP inhibitors [11,12]. PARP inhibitor is a milestone in the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Monotherapy with a PARP inhibitor has demonstrated efficacy for both first-line and recurrence settings in ovarian cancer. PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy can be used in patients with BRCA 1/2 mutated advanced ovarian cancer who responded to first-line chemotherapy, or patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer who responded to chemotherapy. PARP inhibitor also can be utilized as a treatment in third-line and beyond for recurrent ovarian cancer patients with BRCA1/2 mutations. However, some crucial questions remain unanswered. Monotherapy of PARP inhibitor or combination therapy of PARP inhibitor and antiangiogenic agent, which is the better option for maintenance treatment in patients with non-BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer? Whether other agents (immune checkpoint inhibitors, WEE1 inhibitors or antibody-drug conjugates) would exhibit synergistic effects with PARP inhibitors? Could patients be re-treated with PARP inhibitors later in the treatment pathway? Could PARP inhibitor be an effective treatment strategy for cancers other than ovarian cancer? Further well-designed studies are needed in these areas.

Up to now, 3 PARP inhibitors, olaparib, rucaparib, and niraparib, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer who responded to chemotherapy [13,14,15,16]. In addition, two original PARP inhibitors, fuzuloparib and pamiparib, have been approved in China for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer. Fuzuloparib now have indications in the maintenance treatment of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer in patients who responded to chemotherapy, as well as in the treatment of patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations and platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer previously treated with second- or later-line chemotherapy regimens [17,18].

Fuzuloparib, also known as SHR3162, AiRuiYi®, or fluzoparib, is a novel, orally available, PARP inhibitor. Fuzuloparib can inhibit the enzyme activity of PARP1, the arrest in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, the DNA double-strand breaks, and apoptosis in HR repair-deficient cells [19]. Several clinical trials (FZOCUS series and others) have been carried out to assess the efficacy and safety of fuzuloparib through different lines of treatments for advanced, recurrent ovarian cancer. These treatments include monotherapy of fuzuloparib and combination of fuzuloparib with apatinib (antiangiogenic agent) for advanced stage and recurrent ovarian cancer, and maintenance therapy of fuzuloparib for platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. In this review, we will summarize the major findings of these studies, and discuss the potential future directions.

FUZULOPARIB

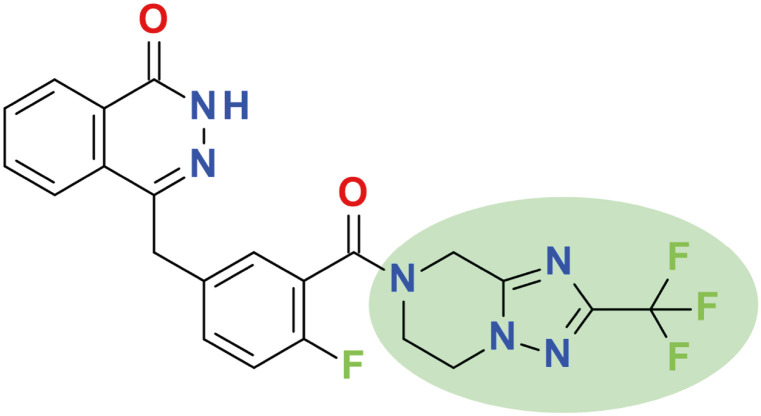

Fuzuloparib (4-[[4-fluoro-3-[2-(trifluoromethyl)-6,8-dihydro-5H-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrazine-7-carbonyl]phenyl]methyl]-2H-phthalazin-1-one, Fig. 1) is the first original PARP inhibitor developed by Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. (Lianyungang, China). By introducing the trifluoromethyl group into the chemical structure (Fig. 1), fuzuloparib exhibits higher stability and lower inter-individual variability than other PARP inhibitors [19]. After oral administration, fuzuloparib is rapidly absorbed with the plasma concentrations quickly reaching maximum within 2 hours and the terminal half-life being 9.14 hours with 150 mg given bid [20,21]. It is worth noting that fuzuloparib has a higher exposure (AUC0-24 hours) in tumor than that in plasma, and a strong ability to block the formation of polymer of ADP-ribose (PAR) in a dose-dependent manner [20]. In addition, fuzuloparib can significantly inhibit the enzymatic activity of PARP1, with a half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 1.46±0.72 nM [14]. In cell culture experiments, fuzuloparib inhibited BRCA2-negative V-C8 cells (IC50 0.053 μM) and BRCA1/2-negative MDA-MB-436 cells (IC50 1.57 μM), while no relevant BRCA1/2-positive cell lines were inhibited by fuzuloparib [22]. In animal experiments, BRCA1-negative breast cancer growth was inhibited by fuzuloparib 30 mg/kg, and the day 21 inhibition rate of fuzuloparib was 59% in ovarian MDA-MB-436 tumours in mice [22].

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of fuzuloparib.

FUZULOPARIB MONOTHERAPY

1. FZOCUS-3 trial

FZOCUS-3 is an open-label, multi-center, single-arm phase 2 trial (NCT03509636) done at 26 sites in China [17]. This trial included 113 patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer and germline BRCA1/2 mutations who had previously received 2–4 lines of platinum-based chemotherapy. These patients were treated with continuous fuzuloparib 150 mg twice daily during each 28-day cycle until disease progression per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1), intolerable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. The median follow-up period was 15.9 months (interquartile range=13.5–18.5) as of the latest data cut-off (March 21, 2020). The primary endpoint was independent review committee (IRC)-assessed objective response rate (ORR) per RECIST v1.1, and it was 69.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]=60.6–78.2). The investigator-assessed ORR was 70.8% (95% CI=61.5–79.0). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 12.0 months (95% CI=9.3–13.9) per IRC and 10.3 months (95% CI=9.2–12.0) per investigator. Although the overall survival (OS) data were not mature at the time of data cut-off, the probability of reaching 12-months of survival was 93.7% (95% CI=87.2–96.9).

Based on positive efficacy results of the FZOCUS-3 trial, fuzuloparib received its first approval on December 11, 2020 in China for the treatment of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer in patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations who had undergone second or later-line chemotherapy.

2. FZOCUS-2 trial

FZOCUS-2 is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (NCT03863860), assessing the efficacy and safety of fuzuloparib as a maintenance therapy for patients with high-grade, platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer who received at least two prior lines of platinum-based chemotherapy and achieved either complete or partial response to their most recent regimen [18]. A total of 252 enrolled patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either fuzuloparib (150 mg, twice daily) or matching placebo for 28-day cycles until the occurrence of radiologic disease progression according to RECIST v1.1 or unacceptable toxic effects. Patients were stratified based on BRCA 1/2 mutation status (presence [39.5% of patients in the fuzuloparib group vs. 40.0% of patients in the placebo group] or absence [60.5% of patients in the fuzuloparib group vs. 60.0% of patients in the placebo group]), progression-free interval after penultimate platinum-based regimen (6–12 months [33.5% of patients in the fuzuloparib group vs. 32.9% of patients in the placebo group] or ≥12 months [66.5% of patients in the fuzuloparib group vs. 65.9% of patients in the placebo group]), and best response to the most recent platinum-based regimen (complete response [50.3% of patients in the fuzuloparib group vs. 50.6% of patients in the placebo group] or partial response [49.7% of patients in the fuzuloparib group vs. 49.4% of patients in the placebo group]). The median follow-up period was 8.5 months (range, 0.1–14.1months) as of the latest data cut-off (July 1, 2020). Median blinded independent review committee (BIRC)-assessed PFS in the overall population (primary endpoint) was 12.9 months (95% CI=11.1 to not reached) with fuzuloparib and 5.5 months (95% CI=3.8–5.6 months) with placebo. PFS was significantly improved with fuzuloparib (hazard ratio for disease progression or death=0.25, 95% CI=0.17–0.36; one-side p<0.0001). Moreover, fuzuloparib was superior to placebo in prolonging PFS per BIRC assessment in patients with germline BRCA 1/2 mutations (hazard ratio=0.14, 95% CI=0.07–0.28) (co-primary endpoints) or in those without germline BRCA 1/2 mutations (hazard ratio=0.46, 95% CI=0.29–0.74).

On June 22, 2021, fuzuloparib was approved as maintenance treatment of patients with recurrent platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who were in a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy in China based on the interim analysis of FZOCUS-2 trial.

3. Safety

According to phase I and FZOCUS-3/2 trials, monotherapy with fuzuloparib 150 mg twice daily was generally well tolerated, with manageable and acceptable adverse events in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer [17,18,20]. For non-hematological toxicity, nausea, asthenia/fatigue, and vomiting were the commonest treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) of any grade. Grade ≥3 non-hematological TEAEs were observed in only three incidences (3/113, 2.7%) of vomiting in the FZOCUS-3 trial [17] and in only one incidence (1/167, 0.6%) of nausea in the FZOCUS-2 trial [18].

Some common grade ≥3 gastrointestinal side-effects are considered to be class effects associated with PARP inhibitors, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea. These side-effects have been reported by 11%, 10%, and 6.3% in rucaparib-treated, olaparib-treated, and niraparib-treated patients in other phase 3 trials in the same maintenance settings. However, they were reported by only 0.6% of fuzuloparib treated patients in the FZOCUS-2 trial [13,15,16,18]. This may be related to the unique features of fuzuloparib, which is the pattern of postprandial administration and high oral bioavailability [19]. The low incidences of non-hematological toxicities could increase accessibility to the drug, patient compliance and adherence to therapy, and help to improve the efficiency.

Decreased white blood cell count, anaemia/decreased haemoglobin, decreased platelet count, and decreased neutrophil count were the most common all-grade hematologic toxicity events with fuzuloparib, and were similar to that of other PARP inhibitors [21,23,24]. Grade ≥3 toxicities were mainly hematologic and included anaemia/decreased haemoglobin (32.7%/25.1%), decreased white blood cell count (12.4%/10.8%), decreased platelet count (12.4%/16.8%), and decreased neutrophil count (10.6%/12.6%) in the FZOCUS-3/2 trial [17,18]. Most of grade ≥3 toxicities can be managed through dose interruption and/or reduction, which could be mitigated to grade ≤2 within approximately 1–2 weeks [17,18].

FUZULOPARIB COMBINATION THERAPY

The combination therapy of PARP inhibitors and anti-angiogenic agents has become a major area of interest in ovarian cancer. Antiangiogenic agents have been proved by preclinical studies to be able to induce a hypoxic environment, down-regulate HR repairing proteins, enhance PARP inhibitor sensitivity, and cause synergistic behaviors between these two groups of drugs [25,26,27,28,29]. Further studies have demonstrated that the clinical outcomes can be improved by the combination of these two approaches. Both cediranib–olaparib combination therapy (NCT01116648) and bevacizumab-niraparib combination therapy (AVANOVA2, NCT02354131) showed improved PFS compared to olaparib/niraparib alone in patients with relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer [30,31,32]. However, bevacizumab is administered by intravenous infusion, which could reduce the convenience of administration. Although cediranib is an oral vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), cediranib-associated serious adverse events were problematic in the cediranib plus olaparib group, with 41%, 27%, and 23% of patients having grade 3 or 4 hypertension, fatigue, and diarrhea. Dose reduction occurred in 77% of patients in this combination group [30].

Apatinib (also known as rivoceranib) is an orally active TKI of VEGFR-2 developed by Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. In October 2014, the China Food and Drug Administration approved apatinib for treating patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma after second-line chemotherapy [33]. As third or later-line treatment, apatinib significantly improved PFS and OS and had a manageable safety profile in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer [33].

Apatinib in combination with fuzuloparib was evaluated in phase 1 trial (NCT03075462) for recurrent ovarian or triple-negative breast cancer, and was presented as a poster study at 2022 ASCO Annual Meeting [34]. A total of 30 patients with ovarian cancer and 22 patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) were enrolled and treated to 7 dose levels (up to fuzuloparib 100 mg plus apatinib 500 mg). The result showed that plasma concentrations decreased at steady state of apatinib when combined with fuzuloparib. With increasing dose of fuzuloparib (0 mg to 100 mg bid) in combination with apatinib, the half-life (T1/2) of apatinib was shortened (14.1 hours to 7.3 hours), suggesting that fuzuloparib can accelerate clearance of apatinib in vivo and suppress the toxicity of apatinib. The ORR was 60% (95% CI=42–75) in patients with ovarian cancer and 23% (95% CI=10–43) in patients with TNBC. Among patients treated with fuzuloparib 100 mg plus apatinib 500 mg (the recommended phase II dose), the ORR was 62.5% (95% CI=31–86) in patients with ovarian cancer. The most common grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events were hypertension, anemia/decreased hemoglobin, thrombocytopenia, and decreased white blood cell count. Therefore, the combination therapy of fuzuloparib and apatinib demonstrated a tolerable safety profile and a promising antitumour efficacy in ovarian cancer and TNBC. Additionally, this study provides practical dose recommendations for the subsequent phase 2 dose of the combination of fuzuloparib.

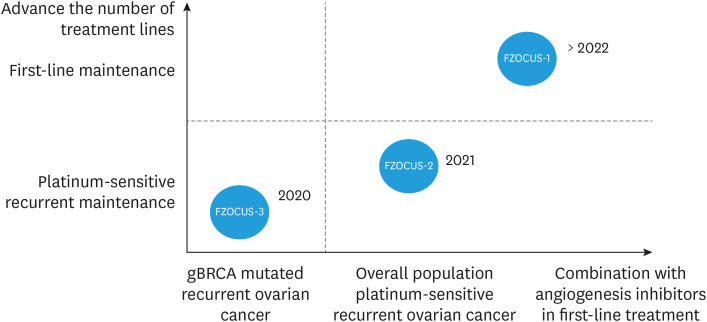

Recently, a PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial (NCT02477644) has assessed the efficacy and safety of olaparib combined with bevacizumab as first-line maintenance therapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer [35]. In the intend-to-treat population, maintenance combination of olaparib and bevacizumab resulted in better survival outcomes than bevacizumab alone. In fact, gynecologic oncologists would be interested to know which is the better option for maintenance treatment in patients with non-BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer, monotherapy of PARP inhibitor or combination therapy of PARP inhibitor and antiangiogenic agent. The ongoing FZOCUS-1 trial (NCT04229615), fuzuloparib for first-line maintenance therapy in platinum-responsive ovarian cancer, is more likely to give a good answer to this question. In FZOCUS-1 study, patients with newly diagnosed FIGO stage III-IV ovarian cancer who had undergone debulking surgery and 6-9 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy were randomly assigned in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive fuzuloparib alone (150 mg bid), fuzuloparib (100 mg bid) plus apatinib (375 mg qd), or placebo group until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The stratification factors are germline BRCA1/2 mutated or not, and the response status of surgery or first platinum-based chemotherapy. The primary endpoint is IRC-assessed PFS, and the second endpoints are investigator-assessed PFS, OS, duration of response, time to study treatment discontinuation or death, time from randomization to second progression or death (PFS-2), time from randomization to first subsequent therapy or death, safety profile, pharmacokinetic and primary debulking surgery. Notably, the design of this study is novel and different from any first-line maintenance study. Firstly, three arms including fuzuloparib plus apatinib, fuzuloparib alone and placebo control group were set up, and a randomized double-blind design was used to obtain adequate and reliable research conclusions. Secondly, both fuzuloparib and apatinib are oral agents, which are the ideal drug regimens in the post-coronavirus disease 2019 era. Finally, the three arms were randomized to be 2:2:1, and 80% of the patients joined the experimental group, which was more friendly to patients. By April 2022, all the 674 patients have been enrolled. We look forward to presenting the results of the first interim analysis in April 2023 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Research and development history of fuzuloparib: expanding from gBRCAm, platinum-sensitive recurrence to first-line maintenance.

Furthermore, a phase 2 study (NCT04517357) of the combination therapy of fuzuloparib and apatinib versus fuzuloparib monotherapy for patients with platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer is ongoing. In patients who had previously taken PARP inhibitor, the exploratory analyses of this study were also conducted to evaluate the reusability of the combination therapy. Moreover, series of clinical studies that tested the re-challenge of fuzuloparib are also underway. All the clinical studies of fuzuloparib therapies mentioned above are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical studies of monotherapy of fuzuloparib or combination therapy of fuzuloparib and antiangiogenic agent.

| Study | Study description | Regimen | Time | Phase | Sample size | Tumor response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03509636, FZOCUS-3 [17] | An open-label, multi-center, single-arm, phase 2 study of fuzuloparib in patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutation and platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer | Fuzuloparib | 2020 | II | 113 | ORR (IRC-assessed): 69.9% |

| ORR (Investigator-assessed): 70.8% | ||||||

| mPFS (IRC-assessed): 12.0 mo | ||||||

| mPFS (Investigator-assessed): 10.3 mo | ||||||

| 12-mo OS: 93.7% | ||||||

| NCT03863860, FZOCUS-2 [18] | Fuzuloparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian carcinoma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial | Fuzuloparib | 2022 | III | 167 (fuzuloparib) | PFS (BIRC-assessed) events in the overall population: 32.9% (fuzuloparib) vs. 70.6% (placebo) |

| 85 (placebo) | PFS (BIRC-assessed) events in the BRCA 1/2 mutation subpopulation: 39.6% (fuzuloparib) vs. 64.7% (placebo) | |||||

| NCT03075462 [34], 104 study (ongoing) | A phase 1 trial of the PARP inhibitor fuzuloparib in combination with the anti-angiogenic apatinib in recurrent ovarian or triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) | Fuzuloparib+apatinib | 2022 ASCO | I | 30 (ovarian cancer) | ORR: 60% (ovarian cancer), 23% (TNBC) |

| 22 (TNBC) | ||||||

| FZOCUS-1, NCT04229615 (ongoing) | Fuzuloparib for first-line maintenance therapy in platinum-responsive ovarian cancer | Fuzuloparib+apatinib | 2023 | III | 674 | Ongoing (three arms including fuzuloparib plus apatinib, fuzuloparib alone and placebo control group were set up) |

| NCT04517357, 201 study (ongoing) | A phase 2 trial of fuzuloparib combined with apatinib versus fuzuloparib monotherapy in treatment with relapsed ovarian cancer patients | Fuzuloparib+apatinib | Ongoing | II | Ongoing | Ongoing |

IRC, independent review committee; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

CONCLUSION

Overall, this article summarized the clinical studies of monotherapy of fuzuloparib or combination therapy of fuzuloparib and antiangiogenic agent in either treatment or maintenance for advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer throughout different lines of treatments (from later-line to front-line treatments). Fuzuloparib has shown promising results with acceptable toxicities. The findings of studies might provide some new treatment options for patients with advanced, recurrent ovarian cancer, and could promote the precision of treatment. In addition to ovarian cancer, fuzuloparib is also being explored in the treatment for other solid tumors such as breast cancer (NCT04296370), pancreatic cancer (NCT04300114, NCT04228601) and prostate cancer (NCT04691804, NCT04869488, NCT04102124). Among these studies, NCT04691804 for combination therapy of fuzuloparib and abiraterone acetate and prednisone (AA-P) versus placebo plus AA-P as a first-line treatment in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate is a global, phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. Further clinical trials on fuzuloparib therapies are in process and the results are eagerly awaited.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: L.N.

- Data curation: L.Q.

- Formal analysis: L.Q.

- Funding acquisition: L.N.

- Investigation: L.Q.

- Methodology: L.Q.

- Project administration: L.N., W.L.

- Resources: L.N.

- Supervision: W.L.

- Validation: W.L.

- Writing - original draft: T.Y.

- Writing - review & editing: L.N., L.Q., T.Y., W.L.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organization. Cancer today [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [cited 2022 Oct 10]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai H, Guo Y, Tian L, Wu L, Li X, Yang Z, et al. Protein panel of serum-derived small extracellular vesicles for the screening and diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:3719. doi: 10.3390/cancers14153719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giornelli GH. Management of relapsed ovarian cancer: a review. Springerplus. 2016;5:1197. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2660-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2019;393:1240–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javle M, Curtin NJ. The role of PARP in DNA repair and its therapeutic exploitation. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1114–1122. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konstantinopoulos PA, Ceccaldi R, Shapiro GI, D’Andrea AD. Homologous recombination deficiency: exploiting the fundamental vulnerability of ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1137–1154. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachdev E, Tabatabai R, Roy V, Rimel BJ, Mita MM. PARP inhibition in cancer: an update on clinical development. Target Oncol. 2019;14:657–679. doi: 10.1007/s11523-019-00680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton JK, Wilson SH. Predicting enhanced cell killing through PARP inhibition. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:13–18. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, Kaufmann SH, Poirier GG. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YQ, Wang PY, Wang YT, Yang GF, Zhang A, Miao ZH. An Update on poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors: opportunities and challenges in cancer therapy. J Med Chem. 2016;59:9575–9598. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Doroshow JH, et al. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5588–5599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li N, Bu H, Liu J, Zhu J, Zhou Q, Wang L, et al. An open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study of fuzuloparib in patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutation and platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:2452–2458. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li N, Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhu J, Wang L, Wu X, et al. Fuzuloparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian carcinoma (FZOCUS-2): a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2436–2446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Yang C, Xie C, Jiang J, Gao M, Fu L, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of fluzoparib, a novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor undergoing clinical trials. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:1064–1075. doi: 10.1111/cas.13947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Liu R, Shao B, Ran R, Song G, Wang K, et al. Phase I dose-escalation and expansion study of PARP inhibitor, fluzoparib (SHR3162), in patients with advanced solid tumors. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:370–382. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.03.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domchek SM, Aghajanian C, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, Audeh MW, Friedlander M, et al. Efficacy and safety of olaparib monotherapy in germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with advanced ovarian cancer and three or more lines of prior therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee A. Fuzuloparib: first approval. Drugs. 2021;81:1221–1226. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01541-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penson RT, Valencia RV, Cibula D, Colombo N, Leath CA, 3rd, Bidziński M, et al. Olaparib versus nonplatinum chemotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO3): a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1164–1174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oza AM, Tinker AV, Oaknin A, Shapira-Frommer R, McNeish IA, Swisher EM, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with high-grade ovarian carcinoma and a germline or somatic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: Integrated analysis of data from Study 10 and ARIEL2. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bindra RS, Gibson SL, Meng A, Westermark U, Jasin M, Pierce AJ, et al. Hypoxia-induced down-regulation of BRCA1 expression by E2Fs. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11597–11604. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bindra RS, Schaffer PJ, Meng A, Woo J, Måseide K, Roth ME, et al. Down-regulation of Rad51 and decreased homologous recombination in hypoxic cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8504–8518. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8504-8518.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan N, Bristow RG. “Contextual” synthetic lethality and/or loss of heterozygosity: tumor hypoxia and modification of DNA repair. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4553–4560. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegan DC, Lu Y, Stachelek GC, Crosby ME, Bindra RS, Glazer PM. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase down-regulates BRCA1 and RAD51 in a pathway mediated by E2F4 and p130. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2201–2206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904783107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivy SP, de Bono J, Kohn EC. The ‘Pushmi-Pullyu’ of DNA REPAIR: clinical synthetic lethality. Trends Cancer. 2016;2:646–656. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu JF, Barry WT, Birrer M, Lee JM, Buckanovich RJ, Fleming GF, et al. Combination cediranib and olaparib versus olaparib alone for women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70391-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu JF, Barry WT, Birrer M, Lee JM, Buckanovich RJ, Fleming GF, et al. Overall survival and updated progression-free survival outcomes in a randomized phase II study of combination cediranib and olaparib versus olaparib in relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:551–557. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirza MR, Åvall Lundqvist E, Birrer MJ, dePont Christensen R, Nyvang GB, Malander S, et al. Niraparib plus bevacizumab versus niraparib alone for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer (NSGO-AVANOVA2/ENGOT-ov24): a randomised, phase 2, superiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1409–1419. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Xiong J, Wu C, Bai Y, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1448–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Zhang J, Yin R, Song N, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. A phase 1 trial of the PARP inhibitor fuzuloparib in combination with the anti-angiogenic apatinib in recurrent ovarian or triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16 Suppl):5539. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, Pérol D, González-Martín A, Berger R, et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2416–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]