Abstract

Background:

Mistletoe extracts (ME) are used in integrative cancer care to improve quality of life and to prolong survival. ME are available from different producers and differ in pharmaceutical processing, such as fermentation. In contrast to fermented ME, the impact of unfermented extracts on the survival of cancer patients has not yet been assessed in a meta-analysis.

Methods:

We searched the databases Embase, CENTRAL, Europe PMC, Clinicaltrials.gov, Opengrey and Google Scholar, and selected controlled studies on cancer patients treated with non-fermented ME. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies of intervention (NRSIs). The risk of bias was assessed with Cochrane’s ROB2 and ROBINS-I; a meta-analysis was conducted.

Results:

Eleven RCTs and eight NRSIs met the inclusion criteria. The studies were heterogeneous and their ROB2 and ROBINS-I displayed a moderate and high risk of bias, respectively. For RCTs, the pooled effect estimate of non-fermented ME on survival was HR = 0.81 (95% CI 0.69-0.95, P = .01). Subgroup analyses as well as the NRSIs estimation support the robustness of the finding. When active comparators are added to the analysis, the effect estimates become non-significant.

Conclusion:

The results may indicate a positive impact of non-fermented ME on the overall survival of cancer patients. High quality RCTs are necessary to substantiate our results.

Prospero Registration:

CRD42021233177

Keywords: cancer, non-fermented mistletoe, meta-analysis, systematic review

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death, accounting for an estimated 1 in 6 deaths worldwide.1 Due to the demographic change the WHO has forecasted the incidence to rise from 19.3 million new cancer cases in 2020 to 30.2 million in 2040.2 Extract preparations from the European white-berry mistletoe (Viscum album L.) have been used as a supportive cancer treatment for decades.3-5

Two types of mistletoe extracts can be distinguished: fermented mistletoe extracts (fME) and unfermented ones (uME). While the brand Iscador represents fME, abnobaViscum, Helixor, Eurixor, Isorel, and Plenosol are brand names of uME. Although the exact pharmacological mode of action is not completely understood, differences appear for fME and uME, since the extraction profile is strongly dependent on pH.6 Untargeted metabolomics identified strong differences between extracts from different manufacturers.7 fME and uME have been reported to differently stimulate anti-cancer Vγ9Vδ2 T cells8 and to have different cytotoxic effects on Molt 4 cells and HTC cells.9

It is therefore interesting to determine whether the difference in molecular composition results in different clinical effects. While a meta-analysis showed a superiority of fME compared to control on survival in cancer patients, with an estimated effect size of HR = 0.59 (95% CI 0.53-0.65),10 a comparable study has not been conducted for uME. Hence, our goal is to systematically review and quantitatively analyze the literature regarding treatment effects of uME on the survival of cancer patients.

Methods

The protocol was registered at PROSPERO with the number CRD42021233177. The review is reported according to PRISMA.

Literature Search

We searched the databases Embase, Pubmed, OpenGrey, CENTRAL, clinicaltrials.gov, and EuropePMC. Additionally, we hand-searched references lists, Google Scholar and the database of the Verein für Krebsforschung (https://www.vfk.ch/informationen/literatursuche/). The databases were searched with the following terms:

Mistel or mistletoe or Helixor or Iscucin or Eurixor or Lektinol or Vysorel or Isorel or Cefalektin or Viscum or Abnobaviscum or Plenosol or Viscum.

Krebs or cancer or neoplasm/or tumor or tumor or oncolog* or onkologie or carcin* or malignant or metastasis.

#2 AND #3.

The hand-searches in Google Scholar and the database Verein für Krebsforschung used combinations of the terms under #1 and #2 or single terms (eg, Iscucin), respectively.

The searches were performed without any limitations regarding language or year of publication. In case of studies that reported the survival impact of uME and fME without differentiation, we contacted the authors for details. In each case we received the data for the uME only and analyzed them separately.

Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

We included studies comparing the effect of uME on the survival of cancer patients in one group to at least one further control arm (eg, placebo, no treatment, active treatment). Relevant study outcomes were overall, progression-free and disease-free survival (OS, PFS, DFS) or their corresponding time-to-event parameters, respectively. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies on intervention effects (NRSIs) were chosen to account for the highly individualized therapy under mistletoe in the real world; this might be better represented by NRSIs than by RCTs. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the above inclusion criteria.

Quality Assessment

The RCTs were assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2 (ROB2) whereas the NRIS were assessed with the Cochrane’s ROBINS-I.

Data Extraction

Two researchers independently extracted the data and entered it into a spreadsheet. The following characteristics were used: study characteristics (country, blinding status, retro-/prospective design, RCTs vs NRSIs, single vs multi-center, sponsoring), patient characteristics (age, gender, cancer type, stage, number per treatment arm, drop outs), treatment details (control (eg, placebo), intervention duration, uME type, additional therapy), outcome aspects (type of outcome, Kaplan Meier curve vs no KM curve, the natural algorithm of hazard ratio (HR) and its standard error (SE)).

The spreadsheets were compared and discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Statistical Analysis

The summary measure was Hazard Ratios (HR) with their corresponding 95% confidence interval. We extracted HR directly from the included studies if available. In case only other summary time-to-event data (eg, Kaplan Meier curves, relapse or survival rates) were presented, we obtained HR based on published transformation procedures.11 Raw data were provided by 4 authors and analyzed with multivariate Cox regression based on the statistical approach of the original publication if possible. When studies reported more than one comparator (eg, uME + chemo vs chemo vs active control + chemo), we included the comparator that was more common in the remaining studies (eg, chemo) in the main analysis.

Missing P values for reported event rates were calculated with a Chi2 test. In case of no events in one study arm, we applied a constant of P = .5. HR < 1 indicates superiority of uME in our analysis.

The between-study heterogeneity was tested with Cochran’s Q test and the index of heterogeneity (I2).12 As a rough guide ranges of I2 between 30% and 60%, 50% and 90%, and 75% and 100% indicates moderate, substantial and considerable heterogeneity, respectively.13

Possible sources of heterogeneity were investigated by subgroup analyses of pre-defined moderators (country, cancer type, tumor stage, ME type, control type, additional treatment, risk of bias, and intervention duration).

In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses to test the impact of alternative decisions during our analysis. To account for methodological heterogeneity 2 studies had been excluded from the main analyses.13 A prospective NRSI with an active control14 was included in the sensitivity analysis of retrospective NRSIs without active controls. In the same vein, we added an RCT with an active control15 to the pooled analysis of RCTs. Finally, we tested our decision for dealing with multiple comparators in 2 studies16,17 by including the alternative controls instead.

A possible publication bias was investigated by visual inspection of funnel plots, Egger et al’s test18 and Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method.19

The meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4. The publication bias was analyzed with R 4.0.2 and the meta package, the Cox regression were calculated with R 4.0.2 and the survival and the survminer packages.

Results

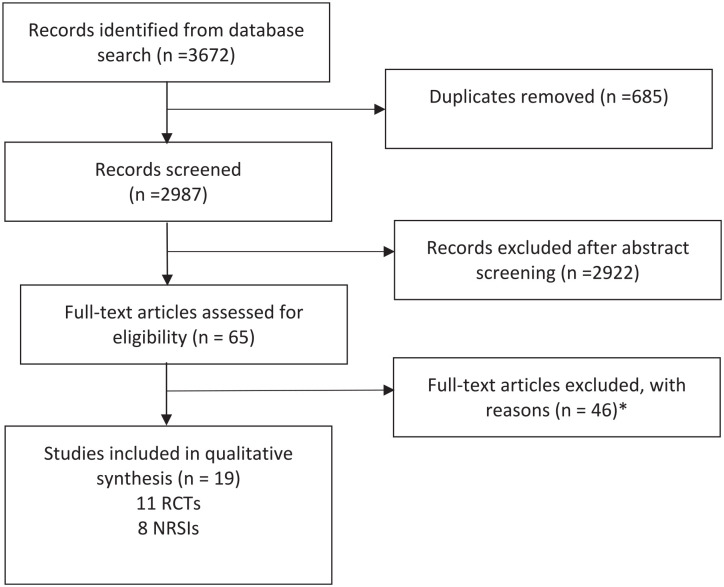

In total, 3672 titles with possible relevance were identified (see Figure 1). Eleven RCTs15-17,20-27, eight NRSIs14,28-34 met the inclusion criteria. The characteristics of the included studies (eg, the survival measure) are shown in Table 1. Two studies compared cancer patients treated with uME or an active control.14,15 With regard to methodological homogeneity, they were only included in the sensitivity analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of literature search. *Reasons for exclusions: Treatment with fME or mix including fME (14 studies), double publication (7×), survival not as outcome (7×), no control group (16×), and insufficient information (3×).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| First author, publication year, country | Study design1 | Participants at baseline; number of females; mean age | Cancer location, stage | Intervention | Survival measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verum | Control | Verum | Control | ||||

| RCTs | |||||||

| Brinkmann,15 2004, Germany2 | Single center | 37; 11; 63 | 37; 13; 62 | Renal cell, 3-4 | Eurixor | IFN-α 2b, IL-2, 5-FU | OS, RR |

| Cazacu,20 2003, Romania | Single center, 3 arms | 29; n/a; n/a | B: 21; n/a; n/a; C:14; n/a; n/a | Colorectal, 3-43 | Isorel, 5-FU, surgery | B: 5-FU, surgery; C: surgery | OS |

| Douwes,16 1986, Germany | Single center, 3 arms | 20; 10; 59 | B: 20; 12; 60; C: 20; 11; 61 | colorectal, 4 | Helixor, 5-FU | B: Neo-Tumorin, 5-FU; C: 5-FU | OS, RR |

| Douwes,21 1988, Germany4 | Single center | 20; n/a; 60 | 20; n/a; 56 | Colorectal, 4 | Helixor, 5-FU | 5-FU | OS |

| Goebell,22 2002, Germany | Single center | 23; 6; 65 | 22; 5; 65 | Bladder, 1-2 | Lektinol | No treatment | DFS |

| Gutsch,17 1988, Germany3,4 | Multi center, 3 arms | 192; 192; 60 | B: 274; 274; 62; C: 177; 177; 62 | Breast, 1-3 | Helixor, ctx | B: ctx; C: no treatment | OS |

| Heiny,23 1997, Germany | Single center | 38; 16; 55 | 41; 18; 53 | Colorectal, 4 | Eurixor, 5-FU | 5-FU | OS, RR, DFS |

| Lange,24 1988, Germany | Single center | 23; 9; 58 | 21; 9; 60 | Ovary, lung, n/a | Helixor, ctx | ctx | RR, DR |

| Lenartz,25 2000, Germany | Single center | 20; n/a; n/a | 18; n/a; n/a | Glioma, n/a | Eurixor, cot | cot | OS, DFS |

| Steuer-Vogt,27 2001, Germany3 | Multi center | 235; 21; 55 | 242; 19; 55 | Head, neck, 1-4 | Eurixor, surgery, ctx | Surgery, ctx | DFS |

| Tröger,26 2016, Serbia | Single center | 34; 34; 50 | 31; 31; 52 | Breast, 1-3 | Helixor, ctx | ctx | RR |

| NRSIs | |||||||

| Axtner,28 2016, Germany | Multi center | 90; 44; 66 | 105; 57; 68 | Pancreatic, 3-4 | uME, ctx | ctx | OS |

| Beuth,29 2008, Germany | Multi center | 167; 167; 55 | 514; 514; 55 | Breast, 1-3 | Helixor, cot | cot | RR, DR |

| Boie,30 1980, Germany | Multi center | 27; n/a; n/a | 39; n/a; n/a | Colorectal, n/a | Helixor | No treatment | OS, DR |

| Elsässer-Beile,14 2005, Germany2 | Single center, prospective | 30; 7; 70 | 18; n/a; n/a | Bladder, 1-2 | Lektinol | Bacillus Calmette-Guerin | RR |

| Prediger,31 1956, Germany | Single center | 75; 75; n/a | 88; 86; n/a | Genital, n/a | Lektinol, rt | rt | OS, DR |

| Schad,32 2018, Germany | Multi center | 43; 18; 64 | 100; 43; 64 | Lung, 4 | uME, cot | cot | OS |

| Schumacher,33 2003, Germany | Multi center | 219; 219; 60 | 470; 470; 64 | Breast, 1-4 | Eurixor, cot | cot | DFS |

| Thronicke,34 2020, Germany | Multi center | 34; 17; 65 | 235; 95; 69 | Lung, 1-3a | uME, ctx | ctx | OS |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; RR, relapse rate; DFS, disease free survival; DR, death rate; cot, conventional oncological treatment; ctx, chemotherapy; rt, radiation therapy.

All studies are not blinded and with 2 arms if not stated otherwise, all RCTs are prospective; all NRSIs are retrospective if not stated otherwise.

This study compares uME with an active comparator and is only included in the sensitivity analysis.

Survival data for subgroups available.

Randomization process is reported as incomplete.

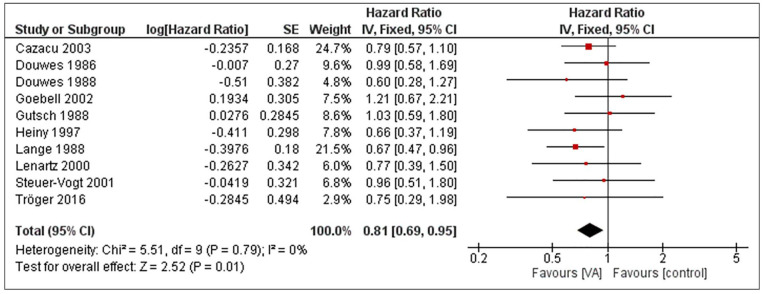

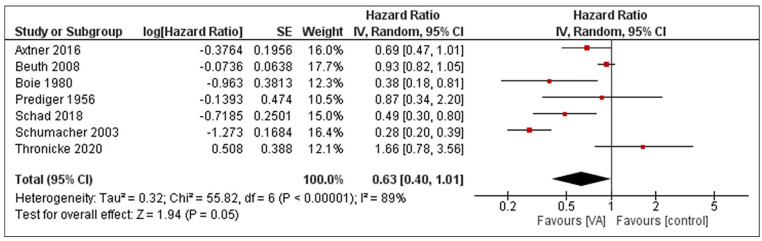

RCTs and retrospective NRSIs were analyzed separately. The pooled effect estimate of uME on the overall survival of cancer patients is HR = 0.81 (95% CI 0.69-0.95), P = .01 when RCTs were analyzed with a fixed-effect model (see Figure 2). The corresponding heterogeneity was I2 = 0%. For NRSIs, the pooled effect size is HR = 0.63 (95% CI 0.4-1.01), P = .05 and the heterogeneity was I2 = 89%, as shown in Figure 3. An explorative conjoint analysis of RCTs and NRSIs is shown in the supplement (see Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of meta-analysis pooling RCTs on unfermented mistletoe extracts regarding the overall survival in cancer patients.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of meta-analysis pooling retrospective NRSIs on unfermented mistletoe extracts regarding the overall survival in cancer patients.

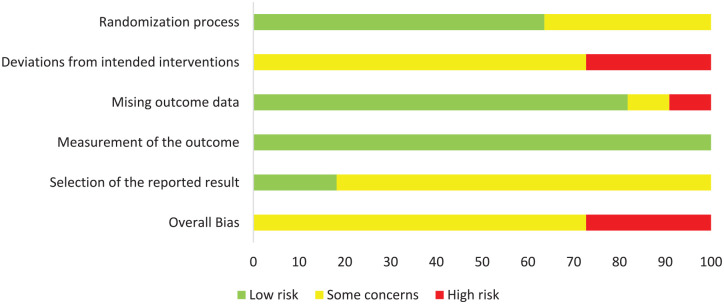

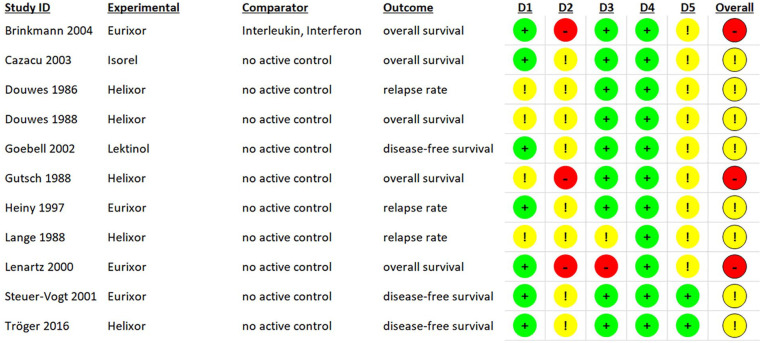

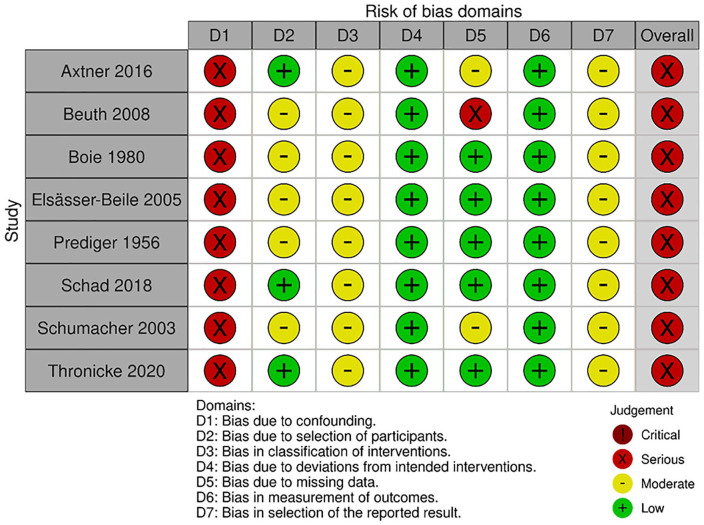

Risk of Bias

The risk of bias for RCTs was assessed with Cochrane’s ROB2. Eight studies had an overall rating of “some concerns” while 3 had a high risk of bias (see Figure 4 for a summary and Figure 5 for a detailed view of the ratings). The NRSIs were assessed regarding their risk of bias by using Cochrane’s ROBINS-I. The ratings per domain are shown in Figure 6. All studies had a serious risk of bias, but none a critical one.

Figure 4.

Summary of risk of bias assessment of RCTs with ROB2 as percentage (intention-to-treat).

Figure 5.

Risk of bias assessment of RCTs with ROB2 by domain (intention-to-treat); Brinkmann 2004 compares uME with an active comparator and is only included in the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 6.

Risk of bias assessment of NRSIs with ROBINS-I by domain; Elsässer-Beile 2005 compares uME with an active comparator and is only included in the sensitivity analysis.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analysis

The results of the subgroup and sensitivity analyses for RCTs are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. In particular, after including the one RCT that (only) used an active comparator (IFN-α 2b, IL-2, 5-FU) effect sizes diverged and the pooled effect size became non-significant15 (see Table 3), with HR = 0.94 (95% CI 0.71-1.25), P = .68.

Table 2.

Subgroup Analysis of the RCTs Meta-Analyses (see Figure 2).

| Moderator | N studies | HR | 95% CI | Heterogeneity I2 (%) | z-score | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | |||||||

| Colorectal cancer | 3 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 1.05 | 0 | 1.59 | .11 |

| Other | 7 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 1 | 0 | 1.96 | .05 |

| Product type | |||||||

| Helixor | 5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.83 | 7 | 4.29 | <.0001 |

| Eurixor | 3 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 1.12 | 0 | 1.34 | .18 |

| Type of survival | |||||||

| OS | 4 | 0.8 | 0.63 | 1.03 | 0 | 1.73 | .08 |

| Other | 6 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.97 | 22 | 2.24 | .02 |

| Tumor stage | |||||||

| 1-3 | 5 | 0.82 | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0 | 1.7 | .09 |

| Including stage 4 | 6 | 0.82 | 0.64 | 1.06 | 0 | 1.53 | .13 |

| Risk of bias | |||||||

| High risk | 2 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.42 | .68 |

| Some concern | 8 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0 | 2.56 | .01 |

Table 3.

| Moderator | N studies | HR | 95% CI | Heterogeneity I2 (%) | z-score | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | |||||||

| Including15 (active comparator) | 11 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 1.25 | 64 | 0.41 | .68 |

| Active control instead of inactive for16 | 10 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 0 | 2.21 | .03 |

| Including15 and active control for16 | 11 | 0.96 | 0.73 | 1.28 | 66 | 0.26 | .79 |

| uME compared to no therapy instead of chemo for17 | 10 | 0.8 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0 | 0.267 | .008 |

| NRSIs | |||||||

| Including14 (prospective NRSIs, active comparator) | 8 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 1.03 | 88 | 1.8 | .07 |

The same is true for one NRSI with an active comparator (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin).14 If this study is added to the meta-analysis of retrospective NRSIs without active comparator, the effect size becomes non-significant with HR = 0.68 (95% CI 0.45-1.03), P = .07 (see Table 3).

For NRSIs, we conducted no subgroup analyses due to the low number of studies.

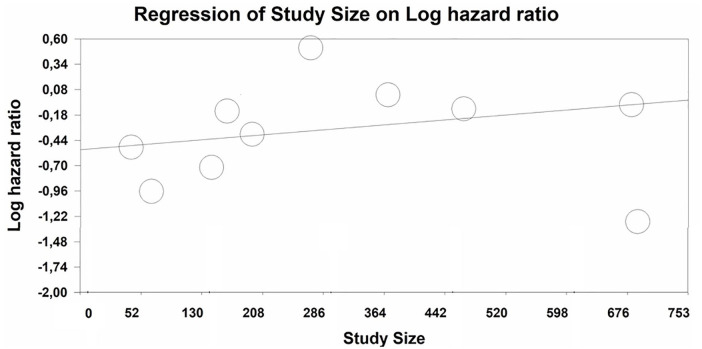

Meta-regressions of study year and study size were non-significant for RCTs. In NRSIs, study size was significantly associated with effect size (Intercept: LogHR = −0.52, P = .0007; Slope 0.00065, P = .01). The larger the study, the larger the effect size (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Meta-regression plot of study size (x axis: number of participants in study) versus LogHR for NRSIs.

Publication Bias

For RCTs, we assessed a possible publication bias by visual examination by Egger’s test and by the Duval & Tweedie’s trim-and-fill procedure. None of these indicated the presence of a funnel plot asymmetry. The Egger’s test resulted in an intercept of I = 0.518 (95% CI −1.11 to 2.15), P = .55). The trim-and-fill procedure yielded no truncation or addition of studies and consequently no bias-corrected effect estimation.

For the NRSIs, the number of studies is too low in order to assess a publication bias.

Discussion

In summary, our analysis resulted in a significant (P ≤ .05) survival benefit for cancer patients treated with uME. This finding is similar for RCTs and NRSIs, respectively. The result should be seen in the light of a moderate to serious risk of bias and the sensitivity of our meta-analyses with regard to studies with active comparators.

Limitations of Evidence Included

The heterogeneity of the NRSIs meta-analysis was high. There are multiple sources of heterogeneity, e.g., different types of uME, cancer types and stages, and a long range of years in which the studies were conducted, starting as early as 1956. On the other hand, our subgroup analysis showed that the meta-analysis of RCTs is robust against multiple moderators, resulting in a statistical heterogeneity of 0% in the meta-analysis pooling RCTs.

Another limitation of the included evidence is that we used relapse rates and progression-free survival as surrogate endpoints of overall survival although they are not identical. Multiple meta-analyses, however, have shown a strong correlation between time to progression and overall survival for different cancer types including colorectal, breast and lung cancer.35-38 The validity of the surrogacy and its reciprocity are still under discussion or unclear.39

Finally, the number of included studies is low and there is at least some concern regarding the risk of bias for all studies. This risk of bias rating is to a large degree due to the fact that mistletoe studies are very rarely blinded; none were in our study pool either. This is due to the fact that mistletoe injections produce local temporary side effects, such as rash.40 In order to blind the mistletoe application, an active placebo would have to be applied which investigators are hesitant to do for ethical reasons and ethics committees often refuse if requested.27 Similarly, regulators consider blinding not to be mandatory at least in RCTs assessing overall survival since a placebo effect is not regarded as likely for this outcome and observer bias for the date of death can be excluded.41 The risk of bias rating is to some extent an artifact of the intervention studied. However, disease or event free survival are potentially subject to an assessment bias41 which may impact our results since 7 of the included studies report surrogate of overall survival only.

Limitations of the Review Process

We included RCTs and NRSIs in our systematic review. To enable comparability between the studies, we analyzed RCTs and NRSIs separately and only pooled both groups for an overall sensitivity analysis and external comparability. Although the resulting effect sizes of RCT and NRSI analyses cannot be simply compared with each other,13 it might allow us to speculate on the effect estimate in a the real world setting which is rather represented by the NRSIs. In contrast, one should bear in mind the possible biases of NRSIs; we therefore interpret the NRSIs as a secondary source of evidence, supporting the meta-analysis of RCTs.

We also included studies irrespective of the nature of the control treatment. Two studies compared uME with another active substance(s) and were therefore considered in sensitivity analyses only.14,15 As these studies used the mistletoe treatment as a control for an active comparator, excluding these studies from the main analysis is justified for conceptual reasons, and it is not surprising to see effect sizes drop when they are included in sensitivity analyses. We would argue, however, that the analysis excluding these actively controlled studies, which we report as a main analysis, yields a fairer pooled effect size.

General Discussion

The hazard ratios which we found indicate a survival benefit in patients treated with uME. It is difficult to say whether the stronger effect size found by Ostermann et al.10 (see Supplemental material for comparison) is due to the fact that fermented mistletoe extracts are more efficacious. To answer this question studies should be specifically designed; we are not aware of any published studies that directly compared uME and fME regarding survival. It is however clear that uFE and fME differ with regard to their chemical compositions.6,7 Since the mode of action of ME leading to survival prolongation is not yet known, differences in efficacy between uFE and fME are at least conceivable.

Even though the survival benefit of uME seems small in cancer patients, it should be borne in mind that especially earlier studies included severely ill patients with poor prognosis. In addition, one should consider that in cancer patients not only survival is an issue, but also quality of life. We have shown in an earlier analysis—including all types of ME—that these interventions improve quality of life.42

Conclusion

In light of a moderate to serious risk of bias, we found that uME may have a positive impact on survival of cancer patients. High quality RCTs are necessary to substantiate our results.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354221133561 for Survival of Cancer Patients Treated with Non-Fermented Mistletoe Extract: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Martin Loef and Harald Walach in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement: The data which support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by the Förderverein Komplementärmedizinische Forschung.

ORCID iD: Harald Walach  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4603-7717

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4603-7717

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. WHO. Factsheet. Cancer. 2022. Accessed March 3, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

- 2. WHO. Cancer tomorrow. WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2021. Accessed March 3, 2021. https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype

- 3. Kienle GS. The story behind mistletoe: a European remedy from anthroposophical medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999;5:34-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grimm D, Voiss P, Paepke D, et al. Gynecologists’ attitudes toward and use of complementary and integrative medicine approaches: results of a national survey in Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303:967-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Cancer Institute. PDQ® integrative A, and complementary therapies editorial board. PDQ Mistletoe extracts. 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/mistletoe-pdq

- 6. Büssing A. Overview of viscum album L. products. In: A Büssing, ed. Mistletoe, the Genus Viscum. Harwood Academic Publishers; 2000;209-221. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanhaverbeke C, Touboul D, Elie N, et al. Untargeted metabolomics approach to discriminate mistletoe commercial products. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14205-14213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ma L, Phalke S, Stévigny C, Souard F, Vermijlen D. Mistletoe-extract drugs stimulate anti-cancer Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Cells. 2020;9:1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ribéreau-Gayon G, Jung M-L, Di Scala D, Beck J-P. Comparison of the effects of fermented and unfermented mistletoe preparations on cultured tumor cells. Oncology. 1986;43 Suppl 1:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ostermann T, Appelbaum S, Poier D, Boehm K, Raak C, Büssing A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the survival of cancer patients treated with a fermented Viscum album L. Extract (iscador): an update of findings. Complement Med Res. 2020;27:260-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elsässer-Beile U, Leiber C, Wetterauer U, et al. Adjuvant intravesical treatment with a standardized mistletoe extract to prevent recurrence of superficial urinary bladder cancer. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:4733-4736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brinkmann OA, Hertle L. Kombinierte Zytokintherapie vs. Misteltherapie bei metastasiertem Nierenzellkarzinom: Klinischer Vergleich des Therapieerfolgs einer kombinierten Gabe von Interferon alfa-2b, Interleukin-2 und 5-Fluorouracil gegen?ber einer Behandlung mit Mistellektin. Onkologie. 2004;10:978-985. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Douwes F, Wolfrum D, Migeod F. Ergebnisse einer prospektiv randomisierten studie: chemotherapie versus chemotherapie plus. “ Biological Response Modifier” bei metastasierendem kolorektalen Karzinom. Krebsgeschehen. 1986;18:155-163. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gutsch J, Berger H, Scholz G, Denck H. Prospektive studie beim radikal operierten mammakarzinom mit polychemotherapie, helixor und unbehandelter Kontrolle. Dtsch Zschr Onkol. 1988;4:94-100. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cazacu M, Oniu T, Lungoci C, et al. The influence of isorel on the advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2003;18:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Douwes F, Kalden M, Frank G, Holzhauer P. Behandlung des fortgeschrittenen kolorektalen Karzinoms. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Onkologie. 1988;20:63-67. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goebell PJ, Otto T, Suhr J, Rübben H. Evaluation of an unconventional treatment modality with mistletoe lectin to prevent recurrence of superficial bladder cancer: a randomized phase II trial. Urol J. 2002;168:72-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heiny BM, Albrecht V. Complementary modes of therapy with mistletoe lectin-1. Die Medizinische Welt. 1997;48:419-423. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lange O, Scholz G, Gutsch J. Modulation of the subjective and objective toxicity of an aggressive chemoradiotherapy with helixor [Modulation der subjektiven und objektiven Toxizität einer aggressiven Chemo/Radiotherapie mit helixor]. Helixor. 1988;1-27. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lenartz D, Dott U, Menzel J, Schierholz JM, Beuth J. Survival time of glioma patients after complementary treatment with galactoside-specific mistletoe lectin 1. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Onkologie. 2001;33:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tröger W, Ždrale Z, Stanković N. Fünf-Jahres-Nachbeobachtung von Patientinnen mit brustkrebs nach einer randomisierten Studie mit Viscum album (L.) extrakt. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Onkologie. 2016;48:105-110. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steuer-Vogt MK, Bonkowsky V, Ambrosch P, et al. The effect of an adjuvant mistletoe treatment programme in resected head and neck cancer patients: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Axtner J, Steele M, Kröz M, Spahn G, Matthes H, Schad F. Health services research of integrative oncology in palliative care of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beuth J, Schneider B, Schierholz JM. Impact of complementary treatment of breast cancer patients with standardized mistletoe extract during aftercare: a controlled multicenter comparative epidemiological cohort study. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:523-527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boie D, Gutsch J. Helixor bei Kolon-und Rektumkarzinom. In: Denck H, Karrer K, eds. Kolo-rektale Tumoren. Verlag für Medizin Dr. Ewald Fischer; 1980:65-76. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prediger F. Über Ergebnisse der Behandlung inoperabler weiblicher Genitalkarzinome mit plenosol in einem Zeitraum von 5 Jahren. Medizinische. 1956;42:3-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schad F, Thronicke A, Steele ML, et al. Overall survival of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with Viscum album L. in addition to chemotherapy, a real-world observational multicenter analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schumacher K, Schneider B, Reich G, et al. Influence of postoperative complementary treatment with lectin-standardized mistletoe extract on breast cancer patients. A controlled epidemiological multicentric retrolective cohort study. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:5081-5087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thronicke A, Matthes B, von Trott P, Schad F, Grah C. Overall survival of nonmetastasized NSCLC patients treated with add-on Viscum album L: a multicenter real-world study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19. doi: 10.1177/1534735420940384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson KR, Ringland C, Stokes BJ, et al. Response rate or time to progression as predictors of survival in trials of metastatic colorectal cancer or non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:741-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sherrill B, Amonkar M, Wu Y, et al. Relationship between effects on time-to-disease progression and overall survival in studies of metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1572-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Singh S, Wang X, Law C. Association between time to disease progression end points and overall survival in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Cancer Targets Ther. 2014;4:103-113. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chirila C, Odom D, Devercelli G, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between progression-free survival and overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:623-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Belin L, Tan A, De Rycke Y, Dechartres A. Progression-free survival as a surrogate for overall survival in oncology trials: a methodological systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:1707-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steele ML, Axtner J, Happe A, Kröz M, Matthes H, Schad F. Adverse drug reactions and expected effects to therapy with subcutaneous mistletoe extracts (Viscum albumL.) in cancer patients. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. US Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical trial endpoints for the approval of cancer drugs and biologics - guidance for industry. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2018. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/71195/download

- 42. Loef M, Walach H. Quality of life in cancer patients treated with mistletoe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:227-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ict-10.1177_15347354221133561 for Survival of Cancer Patients Treated with Non-Fermented Mistletoe Extract: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Martin Loef and Harald Walach in Integrative Cancer Therapies