Abstract

Approximately 13% of the total UK workforce is employed in the health and care sector. Despite substantial workforce planning efforts, the effectiveness of this planning has been criticised. Education, training, and workforce plans have typically considered each health-care profession in isolation and have not adequately responded to changing health and care needs. The results are persistent vacancies, poor morale, and low retention. Areas of particular concern highlighted in this Health Policy paper include primary care, mental health, nursing, clinical and non-clinical support, and social care. Responses to workforce shortfalls have included a high reliance on foreign and temporary staff, small-scale changes in skill mix, and enhanced recruitment drives. Impending challenges for the UK health and care workforce include growing multimorbidity, an increasing shortfall in the supply of unpaid carers, and the relative decline of the attractiveness of the National Health Service (NHS) as an employer internationally. We argue that to secure a sustainable and fit-for-purpose health and care workforce, integrated workforce approaches need to be developed alongside reforms to education and training that reflect changes in roles and skill mix, as well as the trend towards multidisciplinary working. Enhancing career development opportunities, promoting staff wellbeing, and tackling discrimination in the NHS are all needed to improve recruitment, retention, and morale of staff. An urgent priority is to offer sufficient aftercare and support to staff who have been exposed to high-risk situations and traumatic experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to growing calls to recognise and reward health and care staff, growth in pay must at least keep pace with projected rises in average earnings, which in turn will require linking future NHS funding allocations to rises in pay. Through illustrative projections, we show that, to sustain annual growth in the workforce at approximately 2·4%, increases in NHS expenditure of 4% annually in real terms will be required. Above all, a radical long-term strategic vision is needed to ensure that the future NHS workforce is fit for purpose.

Introduction

Health and care is a heavily service-oriented sector, with staff costs accounting for around 60% of NHS provider spending.1 The NHS in England is the world's fifth-largest employer, with around 1·5 million employees.2 The NHS employs around 164 000 staff in Scotland,3 around 95 000 in Wales, and around 67 000 in Northern Ireland.4 A further 2 million people in the UK are employed to deliver social care services,5 defined as the provision of personal care for children, young people, and adults in need or at risk. Together, the health and care labour market accounts for approximately 13% of the UK workforce. In addition, around 9·1 million people in the UK, notably family members, are unpaid (so-called informal) carers.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, this number has increased to more than 13·6 million people.6 Increasingly, members of the public are being encouraged to take greater responsibility for their health and to self-care.7

As with most other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the health and social care workforce in the UK is overwhelmingly female.8 77% of the NHS workforce9 and 82% of the adult social care workforce are women.10 However, there are wide disparities in the gender distribution of roles. In 2018, only 37% of senior roles in the NHS were held by women (from 31% in 2009);11 in social care, despite men only comprising 18% of the overall workforce, they occupy 33% of senior management positions.10 A substantial gender pay gap exists in the NHS, with the average hourly salary for women being 19% less than that for men.12 One factor that contributes is that women make up 80% of those employed on the lowest Agenda for Change pay bands (bands 1–4).12 The health and social care workforces are ethnically and culturally diverse; as of the last census, people from minority ethnic groups made up 14% of the population in England and Wales and 40% of the population in London,13 while, as of 2019, these people made up approximately 20% of the NHS workforce and almost half of all NHS staff in London.14 Minority ethnic staff are concentrated in lower pay grades in the NHS, with only 6·5% of very senior managers and 8·4% of board members at NHS Trusts being from minority ethnic backgrounds.14 Minority ethnic staff are less likely to be promoted or appointed to jobs they apply for and more likely to experience discrimination, bullying, and harassment from both NHS colleagues and patients.15 The recent COVID-19 pandemic has seen a disproportionate number of deaths in staff from minority ethnic backgrounds, which has increased debate around the role of discrimination and racism in the NHS as a factor contributing to persistent health inequalities between different ethnic groups.16

The effectiveness of health and care workforce planning has significant implications for the NHS, social care, and the health and wellbeing of the UK population. A sustainable health and care workforce is one that will be able to meet the needs of the population in the immediate term and for the foreseeable future. To deliver a sustainable and appropriately skilled health and care workforce, a long-term workforce strategy is needed. This strategy should be informed by workforce planning models that consider the necessary mix of skills required to meet changing health and care needs and should aspire towards developing a self-sufficient supply of staff, rather than an ongoing reliance on foreign-trained staff.17, 18 Such a strategy will also need to take account of technological developments that have the potential to improve quality of care and productivity. It should also promote life-long learning, facilitate effective substitution of skills between health-care professions, and prioritise the health and wellbeing of the workforce itself to improve recruitment and retention.

COVID-19 has exposed weaknesses in the workforce, and the UK has experienced one of the highest rates of excess mortality attributable to the pandemic. The health and care workforce was placed under unprecedented pressure and frequently exposed to high-risk and traumatic situations.19 The health and care workforce will continue to be put under considerable strain as the NHS seeks to address a growing backlog of unmet need for health-care services caused by the cancellation or postponement of many elective procedures and routine care.20 Now, as the UK seeks to rebuild its health and care service and improve resilience against future health-care shocks, we discuss how to develop, support, and sustain the current and future health and care workforce.

In this Health Policy paper, we start by outlining, in brief, the current approach to developing the health and care workforce and the consequences of this approach, highlighting areas where major staff shortfalls exist. We then describe the current strategic response to these shortfalls and lay out future challenges and suggested reforms to ensure the future workforce is sustainable and fit for purpose. The scope of this paper is the UK health and care workforce and, where possible, we refer to UK-wide data. However, when these do not exist, we refer to the best available data, which, in many cases, are from England. We have found the inconsistency of data collection between England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland particularly challenging; the standardisation of health and care data collection across the UK is recommended within the main LSE–Lancet Commission report.21

The current approach to education, training, and planning for the UK health and care workforce

Education and training

Workforce planning in the NHS begins with recruitment to higher education programmes in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and many other health and care professions. The numbers of publicly funded places on such programmes, apart from a small number associated with private university entry, are determined by bodies such as Health Education England, NHS Education for Scotland, Health Education and Improvement Wales, and the Northern Ireland Medical & Dental Training Agency. Regulatory standards are shared across constituent countries, with the remit of regulatory bodies such as the General Medical Council, General Dental Council, and Nursing & Midwifery Council being UK-wide. Furthermore, the scope of the medical Royal Colleges, who play a crucial role in setting educational standards and issuing guidance, extends across the UK.22

It takes 3 years for registered nurses and most allied health-care professionals, such as midwives, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists, to complete undergraduate training.23 Undergraduate training for physicians and dentists normally takes 5–6 years or 4 years through a graduate programme.24 Following the completion of a 2-year foundation programme, further postgraduate training for physicians varies between 3 to 8 years, dependent upon specialism.25 Consequently, the training of health-care professionals is expensive: it is estimated to cost close to £66 000 to train a registered nurse, £393 000 to train a general practitioner (GP), and approximately £516 000 to train a consultant (ie, a senior physician who has completed specialty training).26 The relatively low cost of nurse training reflects, to a large extent, the minimal investment in postregistration training for nurses. For physicians, around £65 000 is in the form of repayable loans for living costs and tuitions,27 with the remainder coming from public funds. Repayable loans are lower in Scotland than they are in the rest of the UK, because Scottish students are not required to pay tuition fees if they attend university in Scotland.28 For nurses, depending on their residence status, students might be eligible for a bursary to cover their tuition fees in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales.29 Students in England, however, are required to pay tuition fees, following the removal of bursaries in 2017.30 In response to concerns about recruitment to nursing, the UK Government has, in part, reversed this decision, and all nursing students starting programmes in England from September, 2020, are now eligible for a non-repayable bursary of at least £5000 per year,31 which covers approximately half of the cost of tuition years. Following the removal of bursaries, acceptances to study nursing in England have increased by 2% in 2016–19.32 During the same period, acceptances to study nursing have risen by 18% in Wales and 24% in Scotland; acceptances in Northern Ireland have remained stable.32 With nursing vacancies increasing—estimated at more than 40 000 in England33—the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee has expressed concern about the absence of planning associated with preregistered and postregistered nurse training, stating that this issue requires urgent attention if future supply is to match demand.34

The training and development of clinical and non-clinical support staff has received less attention than that of other staff groups. Comprising approximately 40% of the workforce,35 this large and diverse group has a substantial impact on the efficiency of the health service and patient experience. Clinical and non-clinical support staff are not clinically trained and are more likely to be recruited from the generic educational system and labour market. Although some members of this varied group, such as NHS managers, have had clear and well regarded career development schemes, many others, such as health-care assistants, have faced inconsistent provision of training and supervision, resulting in varying levels of competence across organisations.36 This staff group also attracts less investment than other groups; only 5% of the Health Education England budget is allocated to training clinical and non-clinical support staff.35 In the wake of the Francis Inquiry,37 an independent review into health-care assistants and support workers recognised the relative neglect of this group and proposed the Certificate of Fundamental Care, a set of minimum standards of competence that need to be achieved before working unsupervised.36 This review also gave rise to the Talent for Care strategic framework,38 which focuses on the career progression of all support staff in the NHS.

Training for support staff who provide social care is even more sparse and typically dependent on independent providers who are responsible for setting pay and facilitating training opportunities. In England, a national organisation, Skills for Care, helps adult social care employers provide education and development opportunities. However, its capacity is highly constrained, with a budget estimated to be more than 200 times smaller than the approximate £5 billion budget of Health Education England.39 Moreover, a substantial proportion of social care is provided by unpaid carers, who are often relatives or friends. Although some opportunities exist for unpaid carers to train to manage the complex needs of patients,40, 41 the provision of such training is inconsistent throughout the UK.

Workforce planning

The four constituent countries of the UK are each responsible for their own planning in relation to the health and care workforce. However, they all draw on a common labour pool, as UK-wide regulatory and professional standards ensure staff can move from one constituent country to another. The number of training places for health-care professionals is commissioned by each devolved government. The commissioning objective has been to bring skilled professionals into the workforce at a rate that compensates for those that exit the workforce, adjusting for changes in health-care delivery models and population needs.42 Historically, social care has usually been excluded from national workforce planning efforts, which have instead typically focused exclusively on the NHS. Workforce planning in the social care sector has also been hampered by poor and fragmented data, although this situation is improving, for example, through the development of the Adult Social Care Workforce Data Set in England.43

Effective workforce planning must ensure that gaps between the need for and availability of skills are anticipated in time for corrective action to be taken. Given training lead times, such planning requires reliable and detailed long-term forecasts of expected demand for health care and trends in health-care needs on which to base projections of the skill mix needed in the workforce.44 These forecasts are challenging given the size and complexity of the NHS, changing health and care needs and priorities, evolving clinical practice and delivery models, political exigencies, the wider labour market (including the private sector), the international market for health-care professionals, and an NHS governed individually by the four constituent countries of the UK. Competing conceptual approaches have been developed to estimate future workforce requirements. These approaches can be broadly categorised as supply-based approaches, which consider factors such as training numbers, recruitment, and retention; and demand-based approaches, which consider factors such as demography, morbidity, health-care utilisation, and gross domestic product (appendix 1 pp 1–2).44 More sophisticated methods combine the analytic frameworks of both supply-based and demand-based factors to incorporate alternative scenarios that reflect the changing forms of care delivery and potential substitution of roles between health-care professionals.45 These approaches are data-intensive and involve complex, joint modelling of many inter-related factors (panel 1 ). The science of workforce planning continues to evolve and, as with any modelling process, there is associated uncertainty when estimating future needs.

Panel 1. Data needs for workforce planning.

Major supply-side factors:

-

•

Entry to the workforce: training numbers, attrition rates, immigration, re-entry rates

-

•

Exit from the workforce: retirement, resignation, emigration, leave (maternity, paternity, study, sabbatical, sickness leave), death (including cause of death)

-

•

Workforce characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity, religion, part-time working, skill mix (including volunteers, unpaid carers, and self-care)

-

•

Workforce shortfalls: vacancy rates, urban and regional imbalances

Major demand-side factors:

-

•

Population characteristics: age, gender, residence, migration, disability

-

•

Disease epidemiology: disease rates, multimorbidity

-

•

Health and care utilisation: hospital, ambulatory, primary and long-term care utilisation, average consultation length

-

•

Unmet need: inequalities in access to health-care services between different subgroups of the population

Alternative scenarios:

-

•

Changing skill mix: empirical evaluations of the effect of substitution of roles between health-care professionals

-

•

Novel models of care: empirical evaluations of the effect of novel models of care

-

•

Emerging technological advancements: empirical evaluations of the effect of substitution of roles between health-care professionals and technology (ie, artificial intelligence and robotics)

These data needs are based on assumptions within international workforce planning models reviewed by Ono and colleagues (2013).44

The present approach to workforce planning in the UK is highly fragmented, localised, and not adequately responsive to operational, geographical, or population needs. Strong decisive leadership with clear roles and responsibilities at the national and local level and a clear structure of accountability are both needed. Although all four constituent countries of the UK have produced workforce plans acknowledging the significance of both supply-side and demand-side factors (appendix 1 pp 6–7), it is not transparent how these factors are used in projecting the size and composition of the future workforce. Instead, emphasis is typically placed on providing guidance for short-term workforce projections to regional health boards or hospitals, such as NHS England's involvement in developing online tools to aid individual NHS Trusts.46 It is unclear how national strategies plan for the changing mix of skills needed or the substitution of roles between health-care professionals, or even to what extent strategy is influenced by lobbying from the individual professional bodies.

A positive development can be found in NHS Scotland's latest workforce strategy. This strategy has actively moved away from considering individual professionals in isolation to a whole workforce perspective (appendix 1 p 2). The new strategy's success has yet to be established, but it represents a decisive move towards the kind of integrated method that is needed.

Consequences of the current approach to developing the health and care workforce

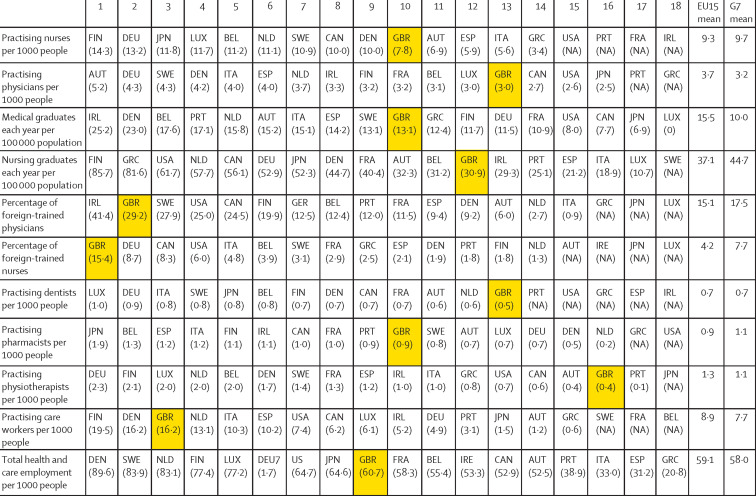

The UK has fewer practising registered nurses and physicians than many other high-income countries (figure 1 ). This fact is partly explained by relatively low numbers of nursing graduates each year, whereas the number of UK medical graduates each year compares more favourably with other high-income countries. The UK also has comparatively low numbers of other clinical staff, such as dentists, physiotherapists, and pharmacists. The relatively low numbers of pharmacists might reflect the nature of the UK market for community pharmacy, whereby economies of scale are gained by the dominance of a few major providers.47 There is a somewhat higher number of care workers in the UK than in other high-income countries. The UK's aggregate health and care employment is close to the mean of EU15 and G7 countries, highlighting the fact that the UK is more reliant on staff trained overseas and on non-clinical staff to deliver health and care services.

Figure 1.

OECD workforce data ranked, from highest to lowest, for EU15 and G7 countries, 2018 (or latest available)

Source: OECD Health Data. Data are from 2018 or the latest year available before that. AUT=Austria. BEL=Belgium. CAN=Canada. DEN=Denmark. DEU=Germany. GBR=Great Britain (UK). ESP=Spain. FIN=Finland. FRA=France. GRC=Greece. ITA=Italy. IRL=Ireland. JPN=Japan. LUX=Luxembourg. NLD=The Netherlands. OECD=Organisation for Eonomic Co-operation and Development. PRT=Portugal. SWE=Sweden.

Several components of the health and care workforce have persistent staffing shortages and require additional investment and support. For the purposes of this paper, we highlight staff shortages in nursing, mental health, primary care, clinical and non-clinical support, and social care. We acknowledge that there are other staff groups not covered in this paper. Some, including the diagnostic,48 hospital medicine,49 emergency care,50 and public health workforces,51 are covered elsewhere. We also include a broader discussion of public health capacity within the main LSE–Lancet Commission on the future of the NHS.21

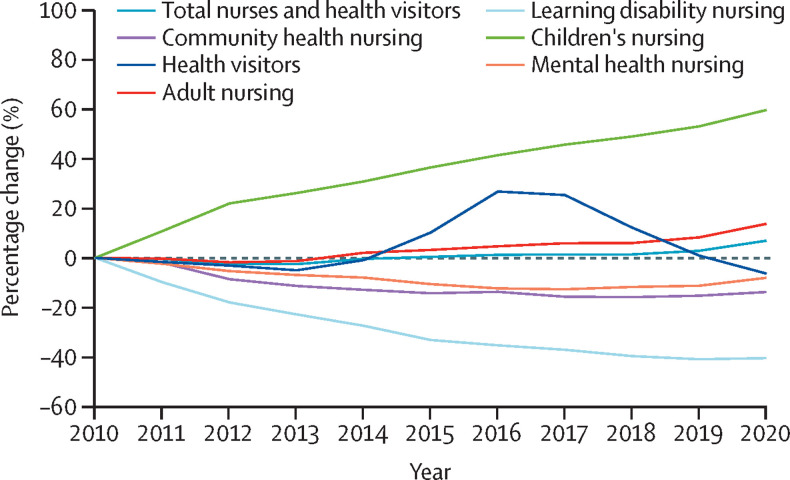

Nursing

Despite the demand for care greatly increasing, the total number of registered nurses per 1000 population has remained largely unchanged over the past decade across the UK (appendix 1 p 3). However, this number masks a differential growth rate in the different types of registered nurses. In England, over the past decade, registered nurses for adults increased by 14% and registered nurses for children increased by 59% (full-time equivalent), whereas mental health nurses decreased by 8% and learning disability registered nurses decreased by 40% (figure 2 ). This outcome might have been driven partially by the Francis Inquiry recommendation to increase hospital nursing numbers, thus distorting the employment of nurses to the acute sector at the expense of community health services.34

Figure 2.

Total percentage change in registered nursing numbers (FTE) in England, 2010–20

Data are from NHS Digital.52 FTE=full-time equivalent.

Retention is an issue of particular concern, with attrition rates during preregistration training of more than 20%;53 in England, the registered nurse turnover rate now averages 10% annually.54 Vacancy rates are higher in England (∼11%)55 than in Scotland (6%)56 and Northern Ireland (4%).57 There are also regional differences, with a vacancy rate of 14% in London and 9% in the north of England.55 Ideally, turnover and vacancy rates should not be interpreted in isolation, particularly as some degree of turnover can be considered as simply reflecting the mobility of the health and care workforce. Stability, which is a measure of how many staff have stayed rather than how many have left, is a useful alternative metric.58 Stability indices reported by NHS Digital, reflecting the number of staff who stay in their post for more than a year, have remained relatively stable for nurses in England between 2014 and 2018, at just less than 90%.59 The NHS England Interim People Plan acknowledges how nurses are integral to the vision of multidisciplinary teams working to address individual patients' needs, particularly in primary care and mental health services.60 The plan prioritises urgent action to address nursing shortages, including by increasing training places, promoting alternative routes into the profession (eg, nursing associates and apprenticeships), and encouraging nurses to return to practice.

Mental health

The number of mental health nurses has dropped by 10% over the past decade (figure 2). This drop has been accompanied by a decrease in the full-time equivalent number of psychiatry physicians per 1000 people in England, although this number has recently recovered to 2009 levels (appendix 1 p 3).

It has proven consistently difficult to recruit physicians into psychiatry, with many core and higher training posts remaining unfilled. The recruitment challenge is compounded by the denigration of professions such as psychiatry and general practice, which begins at medical school.61 There are significant UK-wide variations in so-called fill rates of training posts, with London achieving 100%, Wales 33%, and the northeast of England only 25%.62 There is also a high attrition rate of trained psychiatrists: 5 years after completing specialist training, a third of psychiatrists are not working substantively for the NHS.63 Core psychiatry training has been included in the UK Government's shortage occupation list since 2015.64

The mental health sector relies heavily on other professionals, especially clinical psychologists and other professionals qualified to deliver psychological therapies, occupational therapists, and social workers. One of the main objectives of the Five Year Forward View for mental health was increased access to psychological therapies.65 To achieve this objective, a large increase in staff trained in psychological techniques is still required. The Psychological Professions Network has indicated that more than 6000 new posts have to be created, alongside more than 11 000 new training posts, to make up for the attrition of staff trained to deliver psychological therapies.66 If the number of new posts can be realised, psychologists could take on some of the roles traditionally reserved for psychiatrists, partially making up for the shortfall in psychiatrists' numbers.

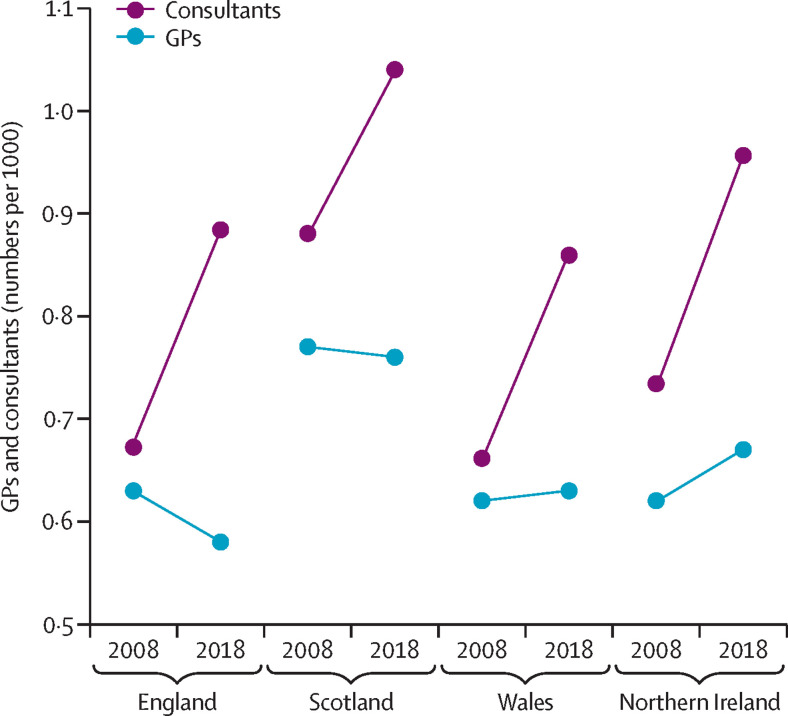

Primary care

The NHS England Long-Term Plan places a strong emphasis on primary care, and there is a growing expectation that some work currently undertaken in hospital settings will take place in primary care instead.67 Between 2008 and 2018, Wales and Northern Ireland have seen slight increases in the number of GPs per 1000 people, but Scotland and England have seen reductions (figure 3 ). These changes contrast starkly with the strong growth in the secondary sector: over the same period, the number of hospital consultants per 1000 people has increased by approximately 40% (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Numbers of GPs and hospital consultants across the UK per 1000 people, 2008–18

Data are from the Nuffield Trust,68 NHS Digital,52, 69 Information Services Division Scotland,3 Stat Wales, Health and Social Care Northern Ireland,4 and the Office for National Statistics.70 GP=general practitioner.

This is an inadequate response to the changing needs of an increasingly older population with multimorbidities that place a high demand on primary care services. The problem is exacerbated by many GPs being aged 55 years and older (23% in England)69 and many GPs choosing to retire early.71 Moreover, although England has seen increases in the total number of GPs over the past decade, the full-time equivalent number has remained largely unchanged, increasing by less than 1% in 2010–20,69 which reflects an ongoing trend towards more part-time and portfolio working. One contributory factor is a high ratio of female to male GPs, as female GPs are more likely to work part-time than male GPs,69 although both genders now work fewer hours than 5 years ago. The latest national GP work-life survey revealed that 39% of registered GPs intended to leave direct patient care within the next 5 years, and that a further 8·7% intended to leave the UK to work abroad,72 although these intentions do not always result in future action. Many complex factors are responsible for GPs leaving direct care, such as a lack of professional autonomy, feeling undervalued, and concerns about the safety of practice, all of which have a negative impact on morale.73

The number of practice nurses has remained fairly static over the past few years, and a significant number are nearing retirement age, with around a third of the workforce being older than 55 years.69 Recruitment into practice nursing is slow. Unlike other countries worldwide, there is no cohesive postregistration training pathway into these roles, and results from a survey of student nurses found that many see these jobs as more suitable for mature experienced professionals.74

To better meet demand, the focus across all constituent countries is converging towards a model of primary care with an expanded multidisciplinary team involving pharmacists, paramedics, physician associates, general and mental health nurse practitioners, and social prescribers.75, 76, 77, 78 This model requires appropriate adjustments in undergraduate programmes, investment in upskilling existing qualified staff, and thorough evaluation of the effectiveness of implementing these new roles and responsibilities.

Clinical and non-clinical support staff

Around 40% of NHS staff are clinical and non-clinical support staff.35 This relatively neglected body includes health-care assistants, porters, cleaners, estate and maintenance workers, administrative and clerical staff, receptionists, managers, and finance, IT support, and human resources staff. It is difficult to obtain accurate figures regarding the vacancy rates for support staff in the NHS. However, recent data show that clerical and administrative staff have the second-highest number of advertised vacancies in the NHS after nursing staff, accounting for approximately 20% of all advertised NHS positions.79

Most of these support workers are in the lower-paid NHS salary bands 1–4 (£9·03–12·16 hourly rate in 2019–20),80 with many constrained by regulations that relate to the higher qualifications and professional registration required to work at band 5 and above. Moreover, given the regulatory restrictions, career progression is limited, and this reflects the insufficient investment in training and development for this part of the workforce, many of whom have the potential to perform at a much higher level.81 Furthermore, because support workers have easily transferrable skills, the NHS competes with the private sector in terms of recruiting and retaining them.

Social care

The social care workforce primarily consists of care workers (also known as care assistants), registered nurses, social workers, and care managers. In England, the overall vacancy rate in adult social care is high and has risen from around 4% in 2012–13 to around 7% in 2019–20.10 There is substantial variation within England, with vacancy rates in London higher than 9% and around 6% in the northeast.10 Turnover is particularly high, amounting to 30% across all adult social care jobs in 2019–20 and 38% for care workers in particular.10 Data on the social care workforce in the other constituent countries are less detailed, but there is a vacancy rate of around 6% each in Scotland,82 Wales,83 and Northern Ireland.57

The International Labour Organisation's Agenda for Decent Work stipulates that care work should provide a fair income, job security, prospects for personal development, safe conditions, equal opportunities, and protection from exploitation.84 Care workers account for approximately 60% of the adult social care workforce in England, and approximately a third of this staff group are on zero-hour contracts with no guaranteed income.10 The average hourly pay for care workers in the social care setting is below the comparable average pay in almost all UK supermarkets.85 The pay differential between care workers with less than 1 year of experience and those with more than 5 years of experience is, on average, just £0·12 per hour, reflecting poor occupational development and training.10 Wages in social care are also significantly less than those in the NHS, with most care staff receiving pay close to the minimum wage level. An estimated £1·7 billion of annual investment is needed to address this discrepancy in England.86 Poor working conditions and unrealistic and excessive workloads further affect problems with recruitment and retention of staff, and quality of care.87

Vacancy rates are particularly high for registered nurses working in the social care sector, at around 12% in England in 2019–20.10 It has been suggested that registered nurses might prefer to work for the NHS, as social care is perceived to give poorer options for career and pay progression.39 An estimated further 6·8 million people in the UK are unpaid carers.88 In England, the provision of respite support for unpaid carers has been restricted, reducing from around 57 000 recorded instances in 2015–16 to 42 300 in 2018–19.89

Current response to health and care workforce shortfalls

Reliance on foreign staff

The NHS has for a long time relied on foreign staff to a further extent than health services in many other high-income countries (panel 1). The percentage of foreign-trained physicians and nurses working in the UK has consistently remained at around 30% and 15%, respectively.90 Similarly, for social care, there is an ongoing reliance on foreign staff: in England, 16% of the adult social care workforce had a non-UK nationality in 2020.10 There is also considerable regional variation. In the NHS, 26% of staff in London are non-UK nationals, compared with just 6% of staff in the northeast and Yorkshire.91 The percentage of non-UK nationals providing social care amounts to 37% in London, compared with only 4% in the northeast and 7% in Yorkshire.10

The NHS has stated that it is committed to the principles of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel.92 These principles state that the recruitment of health-care professionals must adhere to fair and ethical practices. In particular, there should be no recruitment from developing countries facing a shortfall of health-care staff, and recruiting jurisdictions should strive to put in place strategies that reduce their reliance on migrant health-care professionals. Despite this, data collected from OECD countries show that the UK is second only to the USA in being the main destination for foreign-trained doctors and nurses.90 The largest proportion of foreign-trained doctors in the UK originate from India, with whom the UK Government has a formal arrangement.93 However, a substantial number also originate from Pakistan and Nigeria, countries the UK has committed to not actively recruit from.90

The UK intends to continue overseas recruitment and, from July, 2018, the Home Office announced that the tier 2 immigration cap would be lifted for overseas-trained doctors and nurses.94 In accordance with the recommendations of the 2019 Migration Advisory Committee, all medical practitioners, psychologists, registered nurses, social workers, radiographers, speech and language therapists, and occupational therapists have been included in the 2020 shortage occupation list.64 However, despite a recommendation from the Migration Advisory Committee, the government has so far not added care workers to the government's shortage occupation list.95 Although the long-term goal of any health and care workforce strategy should be for the sustainable and self-sufficient supply of staff, in the short term, the UK will need to continue its long-standing tradition of recruiting from the international market.96 However, the UK faces stiff competition from many other countries facing their own health and care workforce crises. Germany, for example, has been projected to have a shortfall of up to 500 000 health and care staff by 2030. The UK's ability to compete in the international health-care labour market will be dependent on factors such as favourable migration policies, wage growth, and working conditions. The UK's poor treatment of staff from minority ethnic groups (ie, all ethnic groups other than White British), highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, may also deter potential international health-care workers from choosing to work in the country, particularly as other less hostile options become increasingly available to them.

Reliance on temporary staff

The failure of previous workforce planning is evident given the ongoing reliance on temporary so-called bank or agency staff to address persistent shortfalls. Bank staff are employed by hospital trusts or health boards directly, while often simultaneously holding permanent employment contracts. Agency staff are provided by private recruitment agencies. Many health-care professionals have responded to low pay by turning down permanent positions in favour of working on a temporary basis. Having high levels of agency staff negatively affects patient experience, quality of care, and staff satisfaction, as well as being detrimental to institutional learning and knowledge acquisition.97 As agency staff often work across multiple health and care providers, this situation has created challenges for infection control, shown by early reports of agency staff contributing to the spread of COVID-19 in care homes.98 NHS Improvement notes that, of the approximately 11% of nursing roles vacant, an unspecified proportion is filled by bank (67%) and agency (33%) staff.55 In 2014–15, the government introduced price caps on agency pay rates, which led to some reductions in spending on temporary staff.55 However, hospital trusts repeatedly submitted applications to exceed these caps to fill their workforce gaps. It has become clear that price caps have not provided a long-term solution because they do not address the underlying problem, the shortage of permanent staff.

Changing skill mix and task shifting

The composition and skill mix of the workforce need to evolve as health needs change and health technology progresses. There are many examples of attempts to improve the skill mix from across the UK, and the NHS has been proactive in experimenting with task shifting, but there is potential to achieve much more. The NHS England Interim People Plan is clear that, to deliver 21st-century care, there is a need for the NHS to achieve a richer skill mix and develop a more flexible and adaptive workforce.60 Changes in the skill mix of the health and care workforce can be accomplished in various ways, for example by the substitution of roles between health-care professionals or by technology, the introduction of new roles, and by staff working in extended roles such as specialist nurses or non-medical prescribers. To facilitate effective changes in skill mix, factors to consider include the best way to develop appropriate knowledge and skill sets, overcoming professional boundaries, and ensuring the right organisational culture and institutional environment to foster change.99

A longstanding example of the substitution of roles between health-care professionals is the introduction of non-medical prescribers, a role that the UK introduced in the early 1990s.100 UK nurses now have access to some of the most extensive prescribing rights globally.101 The number of non-medical prescribers in the UK is not routinely reported, but a 2015 survey estimated there were around 45 000 in England.102 Becoming a non-medical prescriber can improve job satisfaction,103 free up time for physicians to see more acute cases,104 and improve access to care.105 To date, there is no evidence to indicate that non-medical prescribers make more medication errors than physicians do.106 However, they remain under-utilised; on average it takes 6 months for 15% of these individuals to prescribe their first medication,106 and one study reported that fewer than 1% of medications prescribed in hospitals are by non-medical prescribers.107 Barriers to expanding the number of these professionals include a lack of ongoing education103, 108 and organisational factors, such as an imposed formulary and restricted scope of practice.108

In primary care, community pharmacists have increasingly taken on additional responsibilities. This change has been partly to relieve pressure on GPs but also to improve access to preventive services and chronic disease management. These measures include the introduction of supplementary and independent prescribing and the delivery of Medicine Use Reviews, NHS Health Checks, and vaccinations in pharmacies.109 Further developments are planned; in England, a new community pharmacy contract has been agreed,110 including the development of a Community Pharmacist Consultation Service, intended to be a first point of contact for certain patients. In Northern Ireland, the Minor Ailments Scheme aims to empower patients to self-treat minor illnesses using the knowledge and skills of their pharmacist, thereby easing pressure on primary care and emergency services. These initiatives point to a need to evaluate the expanding role of community pharmacists, as the available evidence is currently mixed and inconclusive.111

Other examples of task shifting include the introduction of new roles, such as physician associates and nurse practitioners. The UK has taken the opportunity to learn from the American and Canadian models to develop these roles. Physician associates work alongside physicians, GPs, and surgeons within multidisciplinary teams providing direct patient care.112 They can take medical histories and examine and formulate management plans, but they are not able to prescribe or request radiological investigations.112 Physician associates are a key component of NHS England's strategy to relieve pressure on the primary care workforce, with plans to train 3000 new physician associates and the expectation that 1000 will enter general practice.113 Major barriers to overcome include equipping physician associates with the knowledge and capability to manage medical complexity and overcoming professional boundaries created by non-prescriber status.114 However, perhaps the greatest obstacle for physician associates is the absence of formal regulation. A recent consultation suggested that either the General Medical Council or the Health and Care Professions Council should assume responsibility for the regulation of physician associates.115

There is an established history of utilising nurse practitioners to work with an expanded scope of practice remit in both specialist fields, such as diabetes and mental health, and at first point of contact in emergency care and primary care.116 However, these initiatives have been small scale and determined locally. Expansion of these roles is currently limited by the absence of national policy and investment to underpin the education, training, and regulatory changes required. Similar to physician associates, regulatory mechanisms to support nursing practitioners are currently being explored.117

At a different level of practice, a nursing associate role has been introduced to address a gap in skills and knowledge between care assistants and registered nurses, identified by the Shape of Caring review.118 Nursing associates will undertake 2-year training and work across health and care, contributing to the delivery of fundamental nursing care, supporting registered nurses, and freeing them up to focus on more complex care. The role will also provide a route to graduate-level nursing. In 2018, more than 5000 people were recruited as trainee nursing associates, showing significant demand for such a scheme.119 At the time of writing, it is too early to evaluate the effectiveness of this initiative or the sustainability of the demand for training posts.

Enhanced recruitment initiatives

Enhanced recruitment initiatives have been used by the NHS to attempt to address shortfalls in particular areas, such as primary care, mental health, and nursing, or to improve imbalances in staffing levels between different geographical areas. For example, in 2016, the GP Forward View proposed plans to have an extra 5000 physicians working in general practice by 2020 and devised several incentives to try to achieve this target.113 These included bursaries, a national and international recruitment drive, fellowships for further training, and return to work schemes for GPs not currently practising. Moreover, England, Wales, and Scotland all have a Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme for GP trainees offering a one-off salary supplement of £20 000 to physicians willing to commit to train and work in underserved regions. As of April, 2019, government-backed indemnity arrangements also came in force,120 offsetting professional expenses incurred by GPs. Although the numbers of physicians in general practice training are increasing, the time lag for completion of training, the high attrition rate, and the large numbers of qualified GPs opting to work part-time meant that the government did not meet its target.86 In response, the government has now pledged to recruit an additional 6000 GPs by 2024–25, by expanding training places, increasing international recruitment, and improving retention.121

Within mental health, the Royal College of Psychiatrists launched a 5-year recruitment drive to psychiatric specialty training between 2006 and 2011 to overcome the noted shortage in this area, but this initiative had mixed results.122 Persistent and institutionalised negative attitudes towards mental health patients and the staff who treat them are particularly difficult to alter and strongly influence the pursuit of a career in psychiatry.123 Since 2016, to further improve recruitment, flexible pay premiums have been awarded to physicians choosing to train in psychiatry alongside general practice, emergency medicine, oral and maxillofacial surgery, histopathology, and academia, amounting to up to £20 000 over the full period of specialty training.124 It has not yet been possible to assess the effect of this initiative on recruitment levels in these specialties.

For registered nurses, all four constituent countries in the UK currently operate return-to-practice schemes,125, 126, 127, 128 and associated training fees are fully funded. Additionally, in England, £500 is offered towards other expenses and, in Wales, a bursary of £1000 is offered for registered nurses and £1500 for midwives (plus childcare expenses). There are also funded return-to-practice schemes for Allied Health Professionals.129 Although these schemes are a useful lever to increase staff numbers in the short term, they cannot be relied upon as the primary strategy to address workforce shortfalls, as they typically involve small numbers; for example, just 2400 registered nurses and midwives have enrolled in a return-to-practice scheme in England since 2014.34

With better investment in schemes that dissuade staff from taking early retirement and address the needs of ageing staff, return-to-practices schemes would not be required. For example, as the surgical workforce ages, attention is needed to maximise the benefits of additional experience in caring for patients against the potential for impairment in surgical skill.130 This consideration might require shifting the responsibilities of older surgeons to more managerial and patient-facing roles, but guidance in what circumstances this should occur and how is needed. Similarly, there is a need for attention on how to best support the ageing nursing workforce to convince them not to retire early. Suggested strategies include a sympathetic approach towards what manual tasks might be less suitable for older nurses as well as facilitating flexible working.131, 132 As thousands of doctors, nurses, midwives, and other health-care professionals returned to practice—often after retirement—to help in the fight against COVID-19,133 it will be important to learn from their experiences and ascertain what incentives or working arrangements could convince some to remain practising.

Future key challenges for the UK health and care workforce

Increasing multimorbidity

Demand for health and care will rise in the future not only because the population is ageing but because people are living longer with multiple long-term conditions. The population in the UK with complex multimorbidity (ie, more than four diseases or conditions) is set to double by 2035.134 Patients with multimorbidity are more likely to have unplanned and preventable admissions to hospital,135 and an increased risk of clinical errors is more probable in this situation.136 To be effective, workforce planning must incorporate projections about the changing multimorbidity profile of the population, which provides a more reliable reflection of need than do age and gender composition alone. A better balance between generalists, who have the skills to manage multiple chronic diseases in the same patient, and specialists is needed, instead of continuing a growing trend towards specialisation among many health-care professionals.137 Training for all members of the health and care workforce needs to incorporate at least a basic level of generalist skills.138

To meet the challenge of rising multimorbidity, there will also need to be more investment in integrated care supported by strong community services;139 this approach will require more GPs, community nurses, allied health-care professionals, and care assistants. The emphasis will need to be on providing patient-centred care that prevents disease progression, considers mental and physical health needs simultaneously, and allows people to live independent and fulfilling lives.140 It also requires shifting care closer to home. Significant progress has already been made, as many therapies formerly provided in hospital settings can now be provided at home, including chemotherapy, intravenous antibiotics, blood thinning agents, wound care, rehabilitation, and mental health care.45 The expansion of multidisciplinary teams in primary care will be key to providing the continuity of care needed to better appreciate the evolving multimorbidity in individual patients. Other emerging models are designed to serve as facilitators of integrated care, such as primary care networks in England75 and primary care clusters in Wales,141 which involve staff drawn from GP surgeries, the community, mental health and acute trusts, social care, and the voluntary sector working closely together to care for populations of around 50 000.

Gap in supply of unpaid carers

There are approximately 9·1 million unpaid carers in the UK, who are usually family members or friends.6 As many vulnerable individuals were issued shielding advice during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is estimated the number of unpaid carers increased to 13·6 million people, which is equivalent to one in four adults.6 The last census of unpaid carers in England and Wales in 2011 revealed that 63% of unpaid carers provided less than 20 hours of care per week, 14% provided 20–49 hours, and 23% provided 50 or more.142 58% of these carers are women and 42% are men.143 They perform a wide range of tasks, including personal care, emotional and practical support, and monitoring of medications. Unpaid carers make a fundamental contribution to the health and care sector, and estimates of the financial value of this contribution in the UK vary from £57 billion to £132 billion.88 Most carers intrinsically value the opportunities to provide care and might not even self-identify as carers.144

However, being a carer can have adverse consequences for health, wellbeing, and employment. There is considerable evidence that increasing intensity of informal care provision is associated with poorer physical and mental health.145 That said, at relatively low intensities (less than 10 hours per week), the provision of unpaid care might have the opposite effect and improve health and wellbeing.146 In terms of employment, carers often find they need to reduce their working hours or leave employment completely.147 The International Labour Organisation has highlighted the role that unpaid care work has in hampering the employment opportunities of those providing the care, in particular for women and girls from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds.84 The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly compounded the challenges experienced by unpaid carers, exacerbating the socioeconomic disadvantage they face and starkly exposing their vulnerabilities.148

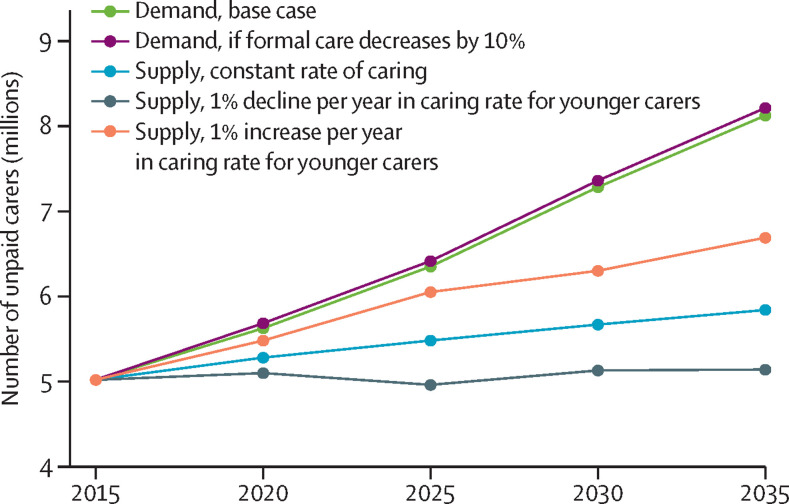

In terms of workforce planning and long-term strategies for the NHS, it is important to consider the probable future scenarios for the supply of and demand for carers, and how these might interact with the wider health and care workforce. Projections of supply and demand by the Personal Social Services Research Unit (now known as the Care Policy and Evaluation Centre), under the assumptions that the propensity to provide care and the disability rates in old age remain constant, suggest a widening gap, reaching 2·3 million unpaid carers in England by 2035 (figure 4 ). This may be a conservative estimate of the carer gap as these projections do not incorporate expected rising rates of complex multimorbidity and associated needs for care and support in old age.134 Such a large gap will inevitably increase demand pressures on the NHS and social care services, especially for individuals with high-intensity care needs for whom the evidence for substitution between funded services and unpaid care is strongest.150 Given the strain on public finances caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unlikely that support for unpaid carers, for example, in the form of tax breaks or further income support, will be forthcoming.

Figure 4.

Projected demand for and supply of unpaid carers for older people in England, 2015–35

Adapted from Brimblecombe et al (2018).149

Leaving the EU

In the UK, the health and care sector has historically been dependent on the supply of EU workers. This supply was facilitated by the free movement directive, which sets out the rights of EU citizens and their family members to move and reside within EU territory. It is not clear how leaving the EU will affect EU workers in the UK but it has been agreed in principle that there should be no preference for EU workers after the UK leaves the bloc.151 To mitigate the impact this change might have on recruitment and retention of the health and care workforce, several measures have been suggested, such as removing the current cap on skilled workers, streamlining certification processes,152 and 12-month working visas for low-skilled migrants until 2025.153 Above all, the UK Government needs to reconsider its position on immigration. By continuing to pursue a policy of encouraging a hostile environment for migrants,154 the UK will disadvantage itself in the international health and care labour market.

Leaving the EU and the preceeding uncertainty has affected the health and care workforce, with some parts hit harder than others. For example, around 7500 fewer registered nurses and midwives from the European Economic Area joined than left the Nursing & Midwifery Council register between 2017–18 and 2019–20 (appendix 1 p 4). However, this shortfall has been compensated by around 16 000 more registered nurses and midwives from outside the UK and EU or European Economic Area joining than leaving over the same time period.155 For social care, over the past decade, an increase of workers from the EU or European Economic Area has helped compensate for a relative decrease in non-EU care workers in the UK due to restrictions on immigration.156 Ending free movement for EU nationals has been estimated to result in 115 000 fewer adult social care workers by 2026.156 Across the UK, leaving the EU will probably affect different countries or regions differently. Approximately 6% of the health and care workforce in England are from the European Economic Area, compared with 6% in Northern Ireland, 5% in Scotland, and 3% in Wales.157 Within England, approximately 12% of the health and care workforce in London are from the EU or European Economic Area, compared with 3% in the northeast.157 In Scotland, the NHS has historically recruited dentists from EU or European Economic Area countries, notably Poland, to address access issues.158 Currently, it is estimated that one in ten dentists in Scotland are from these countries, and it is unclear how leaving the EU will affect retention.158 The UK might struggle to continue to compensate for reductions in the recruitment of EU workers by increasing recruitment of non-EU workers in the short-to-medium term as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to restrict the mobility of the global health and care workforce. The UK needs to anticipate the combined impact of these concurrent events on international recruitment and, in doing so, consider what incentives or policies are necessary to stem the increasing number of EU health and care workers leaving the UK.

Meeting future need by securing a sustainable, fit-for-purpose health and care workforce

Integrated workforce planning

Workforce planning in the UK, while highly fragmented, has been dominated by supply-side rather than demand-side considerations and controlled centrally by a mix of governmental and professional bodies. At the same time, the recruitment and retention of staff is managed by individual health and care providers. This situation has led to a mismatch between the determination of workforce levels through centralised supply-side forecasts and the actual employment of the workforce by individual providers responding to local needs. Although complex, workforce planning must consider a complete picture of demand-side factors, including changing demography driven by growing multimorbidity and the way such changes determine local staffing needs. Multimorbidity is a strong predictor for health-care utilisation,159, 160 and projections of multimorbidity can be used to estimate demand more accurately. Approaches that consider diseases or professionals in isolation will not reflect the changing health needs of the population. Integrated workforce planning should consider changing population demands and organisational responses, as well as the optimal skill mix of staff to ensure the right type of staff are delivering care in the right setting.

Reforms to training and ways of working

Major reform is needed across the entire health and care education system to meet changing health and care needs. If we are to encourage multidisciplinary working, health-care professionals should not be trained in isolation; instead, collaborative working should begin during training. Training should also be more competency-led and community-oriented, and further opportunities should be created to develop new roles as required and facilitate changing the skill mix.161 The Shape of Training review, Future Hospital Commission, and the Parliamentary Review of Health and Social Care in Wales all emphasise the need to implement reforms across the UK that encourage the development of the generalist skills needed to treat multimorbid patients with complex needs and life-long learning,162, 163, 164 which allows physicians, nurses, and any other professional group, to change roles and specialties during their careers. An essential pillar of the re-design of the health professional education system should be higher recognition of the capability and willingness of the public to self-care. All health and care professionals must be equipped with the skills needed to work in collaboration with patients and their families and to facilitate them to make informed decisions regarding their own health.165 There have been some recent moves in the right direction with, for example, the publication of the Nursing & Midwifery Council's new Future Nurse standards for registered nurse education, which place great emphasis on the promotion of health and the support of self-care.166

The Health Policy paper on health information technology linked to the LSE–Lancet Commission highlights how training must adapt to reflect technological advancements.167 The use of technology has great potential to improve the effectiveness and productivity of the workforce by improving quality of care and patient safety, and reducing the administrative burden on staff.168 Major developments in genomics, digital medicine, artificial intelligence, and robotics will result in new roles and the need to re-skill the pre-existing workforce.169 The appropriateness of educational curriculum and workforce strategies must be regularly reviewed to respond rapidly to these developments and avoid slow uptake and the diffusion of technology skills.

The Future Hospital Commission highlighted the imperative to adapt ways of working to meet changing health and care needs.163 Services will need to be re-designed around individual patients, with a focus on developing culturally sensitive and flexible services that allow people to navigate seamlessly throughout their patient pathway, avoiding unnecessary contacts with multiple health and care providers. Workforce strategies need to consider how to support these service reforms by encouraging a fundamental shift in ways of working to allow effective integration, better sharing of information, improved transfers of care, and the provision of services outside the hospital, such as specialist medical care and so-called hospital-at-home teams. Similarly, the Parliamentary Review of Health and Social Care in Wales recommended the development and implementation of models of care that are as close to the individual's home surroundings or community as is practical.164 This approach will require maximising the use of digital technology to improve access, rebalancing services currently provided inside the hospital, and empowering multidisciplinary teams to work together on strategies to help patients avoid unnecessary admissions to hospital. To generate evidence on new models of care, evaluation must be embedded. Workforce strategies should consider the clinical academic workforce, which has decreased by 2·5% since its peak in 2010, to support this evaluation.170 Finally, new ways of working in health and social care, changes to the skill mix of the workforce, and expansion of task shifting will bring new leadership challenges. The NHS England Interim People Plan highlights how future leadership will need to be “systems-based, cross-sector and multi-professional” to meet this challenge, and that development of leadership skills should be embedded in the life-long learning of health and care professionals.60

Promoting life-long learning

Providing adequate opportunities for career progression is vital to improving job satisfaction, ensuring staff feel valued, and retaining existing staff across all health professions. This is particularly important for support staff, such as health-care assistants and care workers, who have skills that make them eligible to work in the private sector, with which the NHS must compete to attract and retain the staff it needs. It is therefore crucially important to tap into the intrinsic motivations that stimulate these individuals to seek work in the health sector, and to foster these motivations by providing appropriate opportunities for career progression that allow them to maximise their potential and feel valued. Professionalisation of this part of the workforce would also help improve recruitment and retention.171 The Cavendish Review introduced the Care Certificate in England, but this is not a mandatory requirement and uptake has been slow.87 A code of practice and a nationally approved training and accreditation system to nurture talent and recognise skills acquired in informal settings would improve quality of care and give these workers the value and recognition they deserve.171

Nurses and allied health-care professionals might also be convinced to leave the NHS for the private sector, work overseas, or even retrain in alternative professions. To mitigate against these risks and foster more fulfilling and engaging careers, there is a need to significantly invest in more postregistration career development opportunities for these groups. Clear links have been shown between career development opportunities and feeling valued and intending to remain in the workforce.34 This investment is equally important for physicians, for whom career development is heavily focused on the pathway to becoming a consultant or GP, with less focus on mid-career development opportunities. Alongside measures such as more flexible working and allowing older professionals to avoid out-of-hours work, improving career development opportunities could be a valuable strategy to prevent early retirement.172

Tackling discrimination in the NHS

The NHS rolled out the workforce race equality standard programme in 2015, an annually reported set of indicators measuring ethnic inequalities in key outcomes across NHS organisations.14 These indicators highlight a deep-rooted culture of discrimination in the NHS, in which minority ethnic staff are concentrated in lower pay grades and face greater barriers in achieving promotions or being selected for jobs for which they are shortlisted. In addition, they are more likely to be formally disciplined and experience harassment, bullying, or abuse from other staff, patients, relatives, or members of the public.14 They are also almost three times as likely to personally experience discrimination at work from a colleague as their White colleagues.14 Modest progress has been made on some indicators, but other indicators have actually worsened during the same period, with the number of minority ethnic staff experiencing discrimination at work from a colleague increasing from 14% to 15·3% between 2016 and 2019.14 This finding has led to calls for improved accountability for organisations that fail to make progress against these indicators and when evidence emerges that leadership has failed to take action to rectify discrimination or harassment in the workplace.173 Treating this group of minority ethnic staff that constitute a fifth of the overall NHS workforce fairly, as well as being a moral obligation, will allow the NHS to fully benefit from their expertise and unlock productivity in the workforce that is currently being lost to discrimination.

Protecting staff wellbeing

The 2019 Mental Wellbeing Commission report from Health Education England highlighted the scarcity of emotional and psychological support available to staff and the fear many staff have of negative repercussions should they seek help for mental ill-health.174 Those working in health and care are recurrently exposed to distressing events that, for most people, happen rarely. To add to this, more than 200 000 written complaints are made about NHS staff every year,175 and an increasingly litigious climate makes many fearful of untoward incidents and investigations. Unsurprisingly, rates of mental health issues among health-care workers are high,176 and some groups of health-care workers are known to have much higher suicide rates than the general population.177 The COVID-19 pandemic has exemplified this issue, with many staff exposed to high-risk and challenging scenarios on an almost daily basis19 and significant delays and changing guidance around the use of personal protective equipment.178 The trauma caused by these experiences will have a long-lasting impact on the mental health of staff. The NHS and social care organisations have a moral obligation to implement sufficient aftercare for these staff, including active monitoring to ensure those who need additional support are identified.19 The Mental Wellbeing Commission makes many welcome recommendations to promote mental health and increase the availability of psychological support,174 such as improving leadership and accountability for wellbeing at an organisational level, improving training in self-awareness and self-care, implementing wellbeing check-ins within 2 weeks of starting placements, the provision of rest spaces during on-call shifts, enhancing peer group support mechanisms, and the introduction of a compulsory requirement in every NHS organisation to independently examine the death by suicide of any NHS staff member. The UK can also learn from Germany, which has chosen to introduce specific legislation to support the recruitment and retention of hospital nurses, which includes the introduction of an earmarked fund for workplace health promotion activities.179 There is a good economic rationale to invest in better pastoral and health care for the workforce, with the estimated return on investment in workplace mental health interventions of £4·20 per £1 spent.180

Adequate terms and conditions

Remuneration clearly helps staff recruitment and retention. However, NHS England salaries had an annual cap of 1% on pay rises between 2013 and 2017, which was preceded by a freeze on public sector pay between 2011 and 2013.181 Since 2017, there has been a deviation from the 1% policy. In 2018, a pay settlement was agreed for all NHS Agenda for Change staff (ie, all non-medical staff) that granted a minimum cumulative rise in pay of 6·5% over 3 years.182 In recognition of efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in pay of 2·8% for all medical staff—backdated to April, 2020—has been awarded.183 However, Agenda for Change staff, including nurses and allied health professionals, are yet to receive an additional pay award to recognise their efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. To improve recruitment and retention, adequate pay and terms and conditions of employment are essential. The UK Government has announced that NHS staff will be exempt from a planned public sector pay freeze in recognition of their efforts during the pandemic.184 However, the LSE–Lancet Commission believes growth in pay should not just stay above inflation, but at least keep pace with average earnings, and this condition should continue beyond the immediate aftermath of the pandemic to ensure the NHS is a competitive employer. Remuneration policy must take account of the alternative employment options that staff have, as NHS staff may choose to work in other parts of the public sector or wider economy, where pay and conditions are better. For nurses and other professions, there is the additional lure of working overseas, where salaries are substantially higher. To support an appropriate remuneration policy, planning more effectively for the future will require linking NHS funding allocations to projected rises in average earnings (panel 2 ).

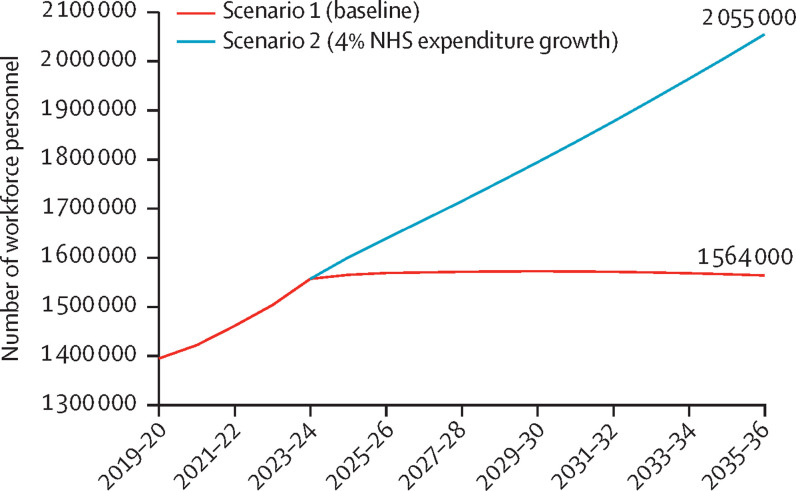

Panel 2. Ensuring NHS pay keeps pace with average earnings—illustrative scenarios.

These workforce projections seek to illustrate possible workforce supply under different assumptions for National Health Service (NHS) spending. Given that the workforce accounts for approximately 60% of NHS expenditure, we believe workforce planning needs to better integrate staffing mix and levels to NHS expenditure plans. Within the Health Policy paper on health and care funding linked to the LSE–Lancet Commission,185 it is argued that a long-term spending increase of at least 4% per year in real terms is necessary to meet demand and improve upon the current standards of health and care delivery. The Office for Budget Responsibility,186 Health Foundation, and Institute for Fiscal Studies,187 have reached similar conclusions. These projections collate the full-time equivalent Hospital and Community Health Services workforce for the entire UK but, due to inconsistent and incomplete data across the UK, do not project the primary care workforce. These projections also assume wage growth keeps pace with average earnings beyond current pay agreements. The Commission argues that this growth in pay is necessary so that the NHS remains an attractive place to work.

We project the labour force under two scenarios (appendix 2). Both scenarios assume wage growth occurs as agreed to 2020–21 under the NHS Terms and Condition of Service 2018182 and then reverts to that forecasted by the Office for Budget Responsibility for average earnings beyond that.188 The scenarios also assume that NHS real expenditure grows in line with the Summer 2018 NHS settlement estimates until 2023–24.189

Scenario 1 (baseline): beyond 2023–24, real NHS expenditure grows at the same rate as gross domestic product using Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts.

Scenario 2 (4% NHS expenditure growth): beyond 2023–24, real NHS expenditure grows at 4% per year.

These projections indicate that between 2018–19 and 2035–36 the workforce could increase by around 200 000 under scenario 1 (ie, a 15% increase) and around 690 000 under scenario 2 (ie, a 51% increase; figure 5 ). There is almost no growth in the workforce past the current funding settlement (2023–24) in scenario 1, whereas workforce growth beyond 2023–24 in scenario 2 is approximately 2·4% per year.

Figure 5.

UK NHS Hospital and Community Health Service workforce supply (FTE) under alternative funding scenarios

FTE=full-time equivalent. NHS=National Health Service.

These illustrative scenarios require several broad assumptions. The most important is the assumption for wage growth, which is highly uncertain in the current environment. The Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts of average earnings used in this analysis reflect their projections published in November, 2020.189 While the workforce projections for scenario 1 are relatively resilient to changes in wage growth assumptions (as projections of wage growth are dependent on projections of growth in gross domestic product), workforce projections in scenario 2 are highly sensitive to changes in average earnings. Our illustrative scenarios also assume that capital–labour substitution and labour–labour substitution is neutral, and we make no adjustments for how alternative scenarios might affect retention or recruitment of staff. These scenarios also have methodological limitations. Our short-term NHS expenditure growth is linked to the 2018 NHS funding settlement,189 which only covers 90% of NHS spending (it does not include training, public health, and capital, and does not reflect additional NHS funding announced in response to the pandemic. Moreover, we assume NHS expenditure growth is the same for the whole of the UK. In reality, the Barnett formula allocates a proportionally higher level of funding to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, which we do not account for.190 As a result, these projections are crude, but they are tied to alternative NHS expenditure growth rates—something that is rarely done.

The central finding of these illustrative projections is that, to sustain growth in the NHS workforce and ensure pay keeps pace with average earnings, increases in NHS expenditure above growth in gross domestic product will be required. However, workforce growth is also dependent on retaining existing staff by improving morale and enhancing career development opportunities. By adopting the LSE–Lancet Commission's recommendation to increase NHS expenditure by 4% per year in real terms, under current assumptions, the workforce will be able to grow at approximately 2·4% per year. This figure is broadly in line with projections of annual activity growth over the next 15 years, estimated to be 2·7% in secondary care.187

Other terms and conditions of employment need to be reformed to improve recruitment and retention. A tapering mechanism that reduces tax relief on pensions for people earning more than £110 000 per year led to more than 30% of GPs and more than 40% of hospital consultants to take early retirement, reduce their hours, or refuse extra shifts.191, 192 While the government has now increased this threshold to £240 000 for 2020–21,193 it is important it develops a long-term solution. Furthermore, job plans need to make allowances for flexible working patterns and be open to job-sharing arrangements, which may help improve retention, especially for those with school-aged children or other caring responsibilities.

Conclusion

To supply a sustainable, skilled, and fit-for-purpose health and care workforce for the UK, a radical, integrated, and long-term strategic vision is needed. To date, this vision has been lacking. Roles and responsibilities for different components of the workforce strategy have been distributed between various national and local stakeholders with no overall ownership or oversight. Workforce planning has been inconsistent and often undertaken in professional silos. The result is fewer health and care staff than in many other high-income countries and major shortfalls in areas such as nursing, mental health, primary care, and social care. The current response has been a reliance on foreign-trained and temporary staff and small-scale changes in skill mix. This approach is neither desirable nor sustainable. Emerging challenges include rising multimorbidity, a gap in the supply of unpaid carers, an ageing workforce, and leaving the EU. To overcome these challenges, there is an urgent need to develop integrated workforce planning, reform education and training, and implement new models of care. The highest priority is to improve recruitment, retention, and morale by taking action to enhance career development opportunities, promote staff wellbeing, tackle discrimination in the NHS, and provide good pay and conditions. There is also an urgent imperative to offer sufficient aftercare and support for staff who have been exposed to high-risk and traumatic experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future funding allocations for the health and care sector must take account of all these issues in order to secure a sustainable and fit-for-purpose health and care workforce.

Declaration of interests

MF is Chair of NHS Wales Shared Services Partnership Committee. MW was a non-executive director of NHS Lothian between February, 2015, to February, 2021. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Josephine Lloyd who contributed to the analysis of health and care workforce strategies in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. We would also like to express our gratitude to all stakeholders who engaged with the Commission throughout our consultation. Funding for the LSE–Lancet Commission on the future of the NHS was granted by the LSE Knowledge and Exchange Impact (KEI) fund, which was created using funds from the Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Contributions

MA drafted the paper and managed the processes of the working group. CO, JMC, and AS led the working group and contributed to the drafting of the paper. AM and MW did the projections of workforce supply and contributed to the drafting of the paper. All authors provided critical input into the content and revisions of the text.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.UK Department of Health & Social Care Annual report and accounts, 2018–19. July 11, 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832765/dhsc-annual-report-and-accounts-2018-to-2019.pdf

- 2.Rolewicz L, Palmer B. The NHS workforce in numbers. May 8, 2019. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/the-nhs-workforce-in-numbers

- 3.Information Services Division NHS Scotland workforce. June 4, 2019. https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Workforce/Publications/