This quality improvement study evaluates social determinants of health associated with severe visual impairment.

Key Points

Question

Which social determinants of health (SDOH) are associated with severe visual impairment (SVI)?

Findings

In this quality improvement study with 820 226 participants, various SDOH were associated with SVI, including self-identification as being from a racial or ethnic minority group; low socioeconomic status and educational level; long-term unemployment and inability to work; divorced, separated, or widowed marital status; mental health diagnoses; and lack of health care coverage.

Meaning

This study found an association of SVI with multiple social disparities and barriers to health care access, suggesting that ophthalmic health and vision are associated with SDOH.

Abstract

Importance

Approximately 13% of US adults are affected by visual disability, with disproportionately higher rates in groups impacted by certain social determinants of health (SDOH).

Objective

To evaluate SDOH associated with severe visual impairment (SVI) to ultimately guide targeted interventions to improve ophthalmic health.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This quality improvement study used cross-sectional data from a telephone survey from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) that was conducted in the US from January 2019 to December 2020. Participants were noninstitutionalized adult civilians who were randomly selected and interviewed and self-identified as “blind or having serious difficulty seeing, even while wearing glasses.”

Exposures

Demographic and health care access factors.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was risk of SVI associated with various factors as measured by odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were performed using the Web Enabled Analysis Tool in the BRFFS.

Results

During the study period, 820 226 people (53.07% female) participated in the BRFSS survey, of whom 42 412 (5.17%) self-identified as “blind or having serious difficulty seeing, even while wearing glasses.” Compared with White, non-Hispanic individuals, risk of SVI was increased among American Indian/Alaska Native (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.38-1.91), Black/African American (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.39-1.62), Hispanic (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.53-1.79), and multiracial (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15-1.53) individuals. Lower annual household income and educational level (eg, not completing high school) were associated with greater risk of SVI. Individuals who were out of work for 1 year or longer (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.54-2.07) or who reported being unable to work (OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 2.66-3.16) had higher odds of SVI compared with the other variables studied. Mental health diagnoses and 14 or more days per month with poor mental health were associated with increased risk of SVI (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.73-2.02). Health care access factors associated with increased visual impairment risk included lack of health care coverage and inability to afford to see a physician.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, various SDOH were associated with SVI, including self-identification as being from a racial or ethnic minority group; low socioeconomic status and educational level; long-term unemployment and inability to work; divorced, separated, or widowed marital status; poor mental health; and lack of health care coverage. These disparities in care and barriers to health care access should guide targeted interventions.

Introduction

Visual impairment is one of the most common disabilities in the US, with approximately 32 million US adults noting blindness or other difficulty seeing despite use of glasses or contact lenses. This reported visual impairment in turn affects various aspects of life including independence in activities of daily living, social functioning, ability to work, mental and physical health, and overall mortality.

Approximately 13% of US adults are affected by severe visual impairment (SVI) and blindness. Social determinants of health (SDOH), important issues throughout medicine, are associated with the risk of visual disability and its myriad consequences in certain individuals. Underuse of ophthalmic screening, preventive care, and treatment disproportionately affects underserved and underrepresented populations including racial and ethnic minority groups, groups with low socioeconomic status, and uninsured individuals. For example, studies have shown that Hispanic patients are less likely to visit an optometrist or ophthalmologist and be able to afford eyeglasses, while Black patients have higher rates of diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and overall worse vision compared with White patients. Lower educational and socioeconomic levels are associated with more vision-affecting comorbidities, such as diabetes and coronary artery disease, and worse vision-related quality of life, while Medicaid eligibility is associated with increased risk of low vision and mental health conditions, including depression and dementia, that may limit pursuit of or adherence with ophthalmic care. An understanding of the SDOH associated with SVI may guide targeted interventions and outreach with the ultimate goal of improving ophthalmic health in individuals with higher odds of SVI.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an annual survey of US noninstitutionalized civilians conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It consists of a collection of cross-sectional, population-based data obtained through standardized telephone surveys of adult residents throughout the US. Survey data collected include self-identified demographic information, chronic health conditions, behavioral health risks, access to health care, and use of preventive care services. The BRFSS comprises the largest and longest-running telephone-based survey in the world. The aim of this study was to use data from the BRFSS to evaluate SDOH, largely in the areas of economic stability, education access and quality, and health care access and quality, associated with increased odds of subjective, self-reported SVI.

Methods

This quality improvement study was considered non–human participant research by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center institutional review board given the deidentified, public nature of the data. Therefore, the institutional review board ruled that approval was not required for this study and informed consent was waived. The study complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) 2.0 guideline was used as a framework for reporting data.

Data for this study were obtained from the collective BRFSS Web Enabled Analysis Tool, which includes logistic regression equations for variables studied in the annual surveys, from January 2019 to December 2020. The years 2019 and 2020 were selected and combined because these were the 2 most recent years from which data were available. All locations (ie, all states) were used. The dependent variable studied was blindness in the disability category, denoted as “blind or have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses,” referred to in this article as SVI. Multiple independent variables were selected in the Demographic Information, Health Care Access, Healthy Days, and Chronic Health Conditions categories, including “gender,” “calculated variable for 8-level race,” “employment status,” “annual household income,” “calculated variable for level of education completed,” “marital status,” “calculated variable for 3-level not good mental health status,” “have 1 or more personal doctor or health care provider,” “do you have any health care coverage,” and “[in the] past 12 months, needed but could not see a doctor because of cost.” The reference category for the dependent variable of blindness was “yes,” while the reference categories for the independent variables were unique to each question, with typically the most common or an intermediate response chosen as a reference. Responses to the aforementioned survey questions represent self-identified data. No mathematical correction was made for multiple comparisons.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were performed using the Web Enabled Analysis Tool in the BRFFS. Descriptive data generated included frequencies of responses to demographic and health access questions, while multivariate analyses yielded t statistics, P values, odds ratios (ORs), and 95% CIs. Two separate logistic regression analyses were completed for the demographic and mental health factors and for the health care access factors in association with SVI due to limitations in the number of independent variables included in a single analysis performed by the web-based tool. Data rather than individual responses were compiled, thus not allowing further analysis to control for confounding. All P values were 2-sided but were not adjusted for multiple analyses; P < .05 was considered significant. Data were stored in Microsoft Excel, version 16.16.27 and graphical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism, version 9.4.1. Limitations of the web-based tool and the lack of individual participant responses did not allow for control of confounding variables.

Results

Between 2019 and 2020, a total of 820 226 people participated in the BRFSS survey (53.07% female), of whom 42 412 (5.17%) self-identified as “blind or having serious difficulty seeing, even while wearing glasses.” The demographic factors analysis included a sample size of 633 866 (77.3% of total surveyed participants in these years). Demographic factors studied are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Factors Studied in the Sample.

| Variable | Participants, % (N = 633 866) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 53.07 |

| Male | 46.93 |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic | 1.62 |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 2.31 |

| Black/African American, non-Hispanic | 7.38 |

| Hispanic | 8.79 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 0.57 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 76.43 |

| Multiracial, non-Hispanic | 2.08 |

| Other, non-Hispanica | 0.83 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed for wages | 44.16 |

| Self-employed | 9.28 |

| Out of work for ≥1 | 1.75 |

| Out of work for <1 y | 2.98 |

| Homemaker | 4.24 |

| Student | 2.37 |

| Retired | 28.76 |

| Unable to work | 6.47 |

| Annual household income | |

| <$10 000 | 4.18 |

| $10 000 to <$15 000 | 4.40 |

| $15 000 to <$20 000 | 6.60 |

| $20 000 to <$25 000 | 8.61 |

| $25 000 to <$35 000 | 9.90 |

| $35 000 to <$50 000 | 13.71 |

| $50 000 to <$75 000 | 16.27 |

| ≥$75 000 | 36.62 |

| Level of education completed | |

| Did not graduate high school | 6.02 |

| High school graduate | 25.47 |

| Attended college or technical school | 28.14 |

| College or technical school graduate | 40.36 |

| Marital status | |

| Married or member of unmarried couple | 56.51 |

| Divorced, widowed, or separated | 26.60 |

| Never married | 16.89 |

| Mental health | |

| Mental health not good, d | |

| 0 | 63.98 |

| 1-13 | 23.72 |

| ≥14 | 12.30 |

| Diagnosis of a depressive disorder | 19.57 |

Other race and ethnicity was not detailed further in the database.

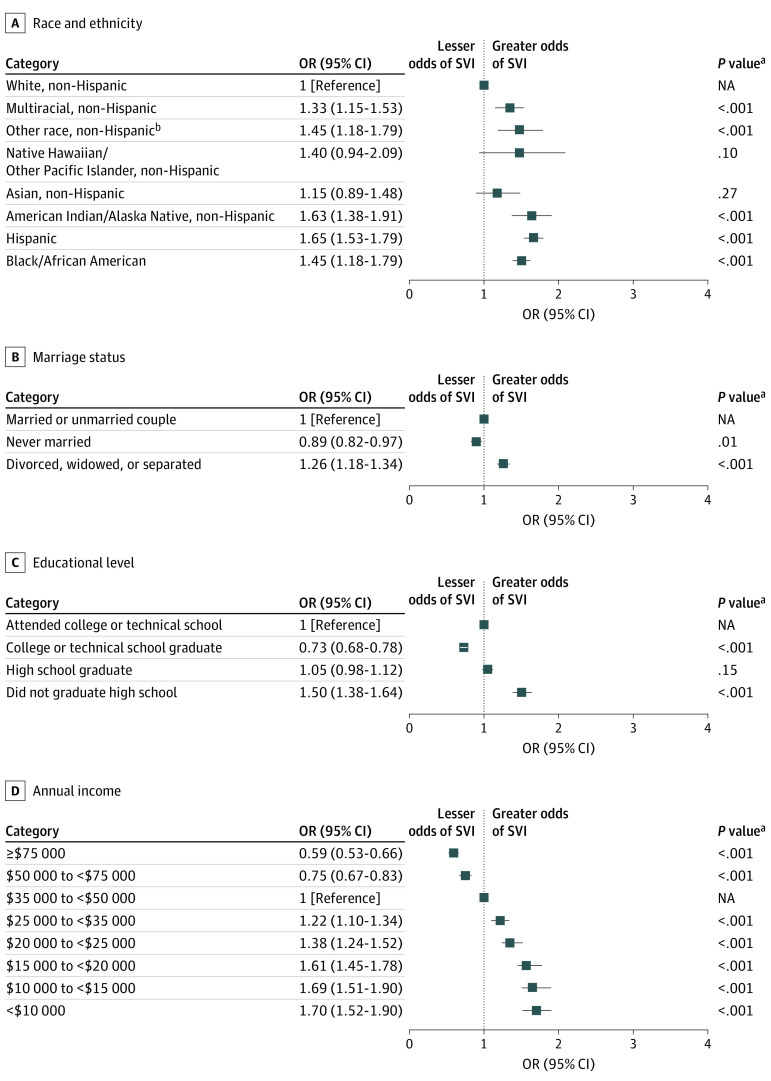

Various self-identified racial and ethnic groups demonstrated an association with SVI (Table 1 and Figure 1A). Compared with the White, non-Hispanic reference group, the odds of SVI were increased among American Indian/Alaska Native individuals by 63% (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.38-1.91; P < .001), in Black/African American individuals by 50% (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.39-1.62; P < .001), in Hispanic individuals by 65% (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.53-1.79; P < .001), and in multiracial individuals by 33% (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15-1.53; P < .001). No association was demonstrated with Asian and Pacific Islander groups compared with White, non-Hispanic individuals. Female vs male gender was not associated with SVI (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.04; P = .49).

Figure 1. Odds of Severe Visual Impairment (SVI) Stratified by Race and Ethnicity, Marriage Status, Educational Level, and Annual Income.

Markers indicate odds ratios (ORs), with horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. NA indicates not applicable.

aNo mathematical correction was made for multiple comparisons.

bOther race and ethnicity was not detailed further in the database.

Every annual household income group less than the reference (annual household income of $35 000-$50 000) was found to be associated with SVI (Table 1 and Figure 1D). Income less than $35 000 was associated with greater odds of SVI, while income greater than or equal to $50 000 was associated with decreased odds of SVI. While the intergroup differences less than $35 000 and, separately, greater than or equal to $50 000 were not significantly different, the trend demonstrated greater odds of SVI associated with lower income; the lowest annual household income group of less than $10 000 had an OR of 1.70 (95% CI, 1.52-1.90; P < .001), in contrast to an OR of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.53-0.66; P < .001) in the highest income group of $75 000 or more.

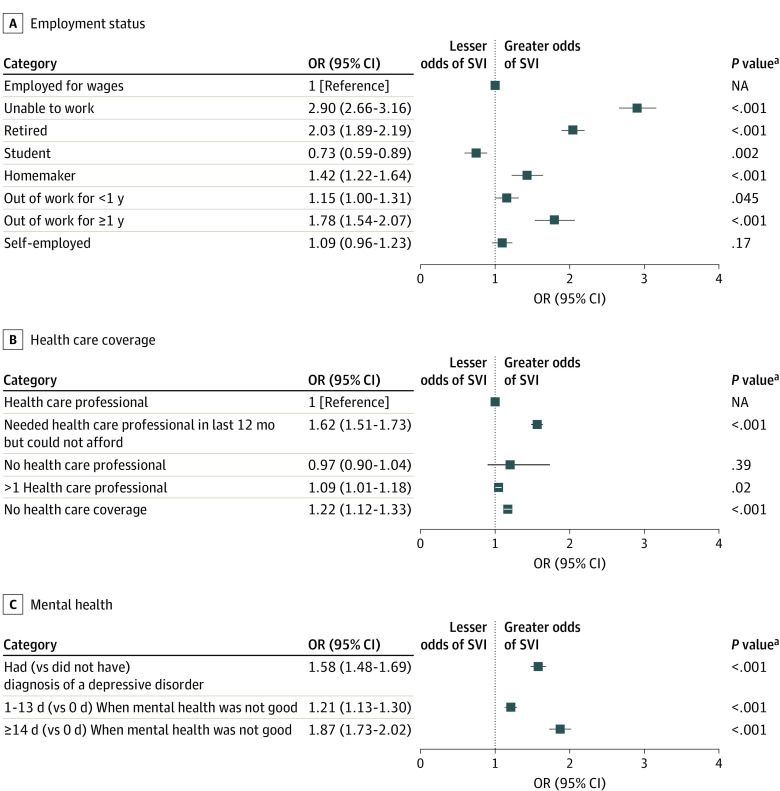

Educational level and employment status were additional factors associated with SVI (Table 1, Figure 1C, and Figure 2A). Individuals who did not complete high school had an OR of SVI of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.38-1.64; P < .001), while graduates of secondary education had an OR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.68-0.78, P < .001) compared with the reference group (attended college or technical school). Of the demographic factors studied, those associated with the greatest odds of SVI were being out of work for 1 year or more (OR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.54-2.07; P < .001), being retired (OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.89-2.19; P < .001), and being unable to work (OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 2.66-3.16; P < .001). Compared with being married, being either divorced, widowed, or separated was associated with higher odds of SVI (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.18-1.34; P < .001) (Table 1 and Figure 1B).

Figure 2. Odds of Severe Visual Impairment (SVI) Stratified by Employment Status, Health Care Coverage, and Mental Health.

Markers indicate odds ratios (ORs) with horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. NA indicates not applicable.

aNo mathematical correction was made for multiple comparisons.

Mental health diagnoses, for which the survey specified inclusion of depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression, were associated with increased odds of SVI by 58% (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.48-1.69; P < .001). Individuals endorsing 14 or more days per month when mental health was not good had an increased odds of 87% (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.73-2.02; P < .001) (Table 1 and Figure 2C) compared with respondents with no such days.

Factors related to health care access that were analyzed included lack of health care coverage, cost as a barrier to health care, and number of established physicians or health care practitioners (Table 2 and Figure 2B). Of the 820 226 participants in the 2019 and 2020 survey, 734 614 (90.0%) were included in this analysis. Lack of health care coverage was associated with a 22% increased odds of SVI (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.12-1.33; P < .001). Respondents expressing inability to afford to see a physician had a 62% increased odds of SVI (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.51-1.73; P < .001). Compared with having 1 physician or health care practitioner, having no physician or more than 1 physician was not associated with SVI (no physician: OR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.90-1.04]; P = .39; >1 physician: OR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.01-1.18]; P = .02).

Table 2. Health Care Access Factors Studied in the Sample.

| Variable | Participants, % (N = 734 614) |

|---|---|

| Personal physicians or health care practitioners, No. | |

| 1 | 76.02 |

| >1 | 7.33 |

| 0 | 16.65 |

| No health care coverage | 8.11 |

| In the past 12 mo, needed to see a physician but could not because of cost | 9.39 |

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrated associations between subjective SVI, defined in the survey as “blind or having serious difficulty seeing, even while wearing glasses,” and multiple SDOH. These associations underscore disparities within ophthalmic care that likely contribute to poor visual measures and influence productivity and quality of life. This data set demonstrated associations between SVI and most demographic and health care access variables evaluated.

As previously noted in research looking at this database, race and ethnicity were associated with SVI, with historically underrepresented and underserved populations found to have increased odds of SVI, demonstrated in this study to be 63%, 50%, and 65% greater among American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, and Hispanic individuals compared with White individuals. This finding may be explained in part by higher prevalence of vision-threatening conditions such as diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma in certain racial and ethnic groups, including non-Hispanic Black/African American individuals compared with non-Hispanic White individuals, as described in prior studies. However, it is likely that there are additional unrecognized and difficult to pinpoint factors associated with odds of visual impairment in these groups.

Income was another known SDOH in which both associations and nonsignificant but consistent trends were demonstrated, with lower income groups having higher rates of SVI. This finding demonstrates an important premise of the methods of this study, whereby we could assess associations but not causation. These patients may not be able to afford care, ultimately leading to decreased access to timely or appropriate ophthalmic intervention, resulting in low vision and even potential loss of the eye, which has also been shown to be associated with low income. Conversely, diminished vision may influence the ability to generate income through, for example, inability to drive to work or use a computer.

Educational level and employment status had similar trends, with lower completed educational levels being associated with increased odds of SVI. Similarly, respondents who were unable to work or who were out of work for 1 year or longer also had increased odds of SVI. Lower educational level may translate to lower health literacy and appreciation of the benefits of preventive eye examinations. Lower educational level may also translate to lower income and therefore lack of health coverage or inability to afford ophthalmic care. Visual impairment has also been reported to affect employment eligibility and work productivity, with poor vision or SVI being an obstacle to many occupations.

Of interest, compared with individuals who identified as married or a member of an unmarried couple, being divorced, widowed, or separated was associated with SVI. This association has been demonstrated in other diseases and in vision research, with those who are not married or partnered having an increased risk of 1 or more chronic conditions. It has been postulated that marriage is associated with improved emotional support, collaboration in health-related goals, and shared responsibility of health management. Alternatively, this association may be attributable to the implications of visual impairment on interpersonal relationships, such as marriage, with studies suggesting that SVI may be considered a stressor that could contribute to separation and divorce.

Poor mental health is a recognized consequence of visual impairment and therefore was, to our knowledge, a novel variable included in this study compared with prior vision research using the BRFSS. Several studies have demonstrated an association between low vision or blindness and depression or depressive symptoms as well as other mental health diagnoses, including anxiety, paranoia, and cognitive impairment. Patients with psychiatric disorders may also experience challenges in accessing health care potentially related to lower motivation, adherence, and independence, and therefore, these disorders may be associated with progression of ocular diseases requiring medication adherence, such as glaucoma, or delayed interventions, such as cataract surgery.

Other barriers to health care access were found to be associated with poorer vision and were, to our knowledge, additional novel variables in our study compared with prior studies of BRFSS data. Lack of health care coverage and cost as a deterrent to seeking health care were associated with a higher odds of SVI, possibly related to inability to afford regular ophthalmic screening and care, less frequent screening and treatment of other comorbidities known to affect vision such as diabetes and hypertension, inability to afford medications, less testing performed by health care practitioners, and overall limited access to health care. Of interest, number of health care practitioners (0, 1, or >1) was not associated with SVI. This finding may be due to younger or healthier adults not having established health care practitioners and, conversely, older adults or those with multiple comorbidities requiring various subspecialists.

Ultimately, the data from this study may form the framework for a discussion on the ophthalmologist’s role in addressing health care access disparities. We found an association between certain obstacles to health care access and SVI. Increasing public awareness of these disparities is critical to furthering research on the subject and fueling targeted healthy policy initiatives. This study focused on SDOH in the areas of economic stability, education access and quality, and health care access and quality, as addressed by the Healthy People 2030 initiatives. Further work remains in addressing other areas of SDOH beyond those assessed in our study, such as access to safe housing and transportation, access to nutritious foods, air and water pollution, and literacy skills. This starts with educating ourselves about health inequity and associated SDOH. At the local level, ophthalmologists can examine their own practices for opportunities to close the access gap, including providing income-adjusted payment for care of populations with low income or for telehealth visits (eg, teleretinal screening) for remote populations with limited health care access. Additional outreach interventions include education on ophthalmic health, for example, at schools; school-based, primary care– or pediatrician-conducted, and community-based screenings; and home or outreach visits for remote populations and those unable to travel to an ophthalmologist, such as nursing home residents or incarcerated individuals. On a larger scale, working alongside state and federal advocacy groups may help promote broader, lasting policy changes.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the survey data are available online in a compiled form rather than given as individual responses that may allow for more sophisticated analyses, including control of confounding factors; therefore, some associations demonstrated in this study may be attributable to confounding. In addition, the survey was conducted by telephone; therefore, it excludes subsets of the population without a landline or cellular telephone (potentially due to financial means), individuals in correctional facilities, and those in long-term care residences. Many of the individuals in these populations may be considered to be from marginalized groups and may lack access to regular ophthalmic care; thus, odds of low vision may be increased. Other subsets of the population that may not be captured in the data set include those who do not speak English or another language in which the survey was conducted. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides a survey translated into Spanish and allows states to translate the survey into other languages, individuals who do not speak a language in which the survey is available are unable to participate and may belong to an already underrepresented group; therefore, significance of trends may have been underestimated in this study.

In addition, given that the data collection was via survey, the outcomes reported were self-identified, including all responses to demographic and health care access questions of interest in this study. Visual impairment was also self-reported, and more specifically because the survey question was a subjective response (ie, “blind or have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses”), responses may have varied among individuals. While some individuals may have responded in the affirmative given a state of legal blindness, others may have considered unsatisfactory what is an objectively better visual acuity.

Another limitation is the grouping of race and ethnicity by the web-enabled analysis tool, which did not allow further distinction of the association of SVI with race and ethnicity as individual variables, and the tool does not include certain race and ethnicity combinations, notably those who self-identify as Black/African American and Hispanic. Some multiracial individuals were also categorized as such if they identified as more than 1 race but did not answer the question of which race best characterizes them, which is noted to be a data collection error by the BRFSS; this may have led to over- or underestimation of the significance of some associations of race and ethnicity with SVI. Overall, minority groups were not well represented in this study, as demonstrated by more than 76% of the participants self-identifying as non-Hispanic White individuals; this may also have led to underestimation of the significance of the association of SDOH with SVI.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the survey, the associations do not represent causative relationships; therefore, the underlying nature of the relationship between visual impairment and these variables could not be determined. Therefore, while there may be associations between low vision and certain variables, it is impossible to state from these analyses whether visual impairment is the causative factor, the consequence, or a combination of both.

Conclusions

In this study, ophthalmic health and vision were associated with SDOH and visual impairment was associated with various disparities in care and barriers to health care access. Recognizing these factors is an important step, although further work remains in assessing the causal relationship between SVI and the factors analyzed in this study. Work also remains in minimizing these inequalities with targeted interventions, such as public health initiatives and outreach to groups at higher risk of SVI, expansion of screening in underserved communities, and increasing accessibility and affordability of ophthalmic care.

References

- 1.Blewett LA, Rivera Drew JA, King ML, Williams KC. IPUMS health surveys: National Health Interview Survey. 6.4 ed. IPUMS NHIS database 2019. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/

- 2.American Foundation for the Blind. Facts and figures on adults with vision loss. Updated September 2020. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://www.afb.org/research-and-initiatives/statistics/adults

- 3.Briesen S, Roberts H, Finger RP. The impact of visual impairment on health-related quality of life in rural Africa. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014;21(5):297-306. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2014.950281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover LL. Making eye health a population imperative: a vision for tomorrow—a report by the Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;94(4):444-445. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West SK, Munoz B, Rubin GS, et al. Function and visual impairment in a population-based study of older adults: the SEE project: Salisbury Eye Evaluation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(1):72-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Tasman WS. Effect of depression on vision function in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(8):1041-1044. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.8.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor HR, McCarty CA, Nanjan MB. Vision impairment predicts five-year mortality. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:91-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner LD, Rein DB. Attributes associated with eye care use in the United States: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1497-1501. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6)(suppl):S53-62.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo YS, Liu CJ, Cheng HC, Chen MJ, Chen WT, Ko YC. Impact of socioeconomic status on vision-related quality of life in primary open-angle glaucoma. Eye (Lond). 2017;31(10):1480-1487. doi: 10.1038/eye.2017.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamedani AG, VanderBeek BL, Willis AW. Blindness and visual impairment in the Medicare population: disparities and association with hip fracture and neuropsychiatric outcomes. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019;26(4):279-285. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2019.1611879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uhr JH, Chawla H, Williams BK Jr, Cavuoto KM, Sridhar J. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in visual impairment in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(7):1102-1104. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan AX, Radha Saseendrakumar B, Ozzello DJ, et al. Social determinants associated with loss of an eye in the United States using the All of Us nationwide database. Orbit. 2021;1-6. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.2012205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Updated May 16, 2014. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/about/index.htm

- 15.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cumberland PM, Rahi JS; UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium . Visual function, social position, and health and life chances: the UK Biobank Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(9):959-966. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahi JS, Cumberland PM, Peckham CS. Visual function in working-age adults: early life influences and associations with health and social outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(10):1866-1871. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seidu AA, Agbadi P, Duodu PA, Dey NEY, Duah HO, Ahinkorah BO. Prevalence and sociodemographic factors associated with vision difficulties in Ghana, Gambia, and Togo: a multi-country analysis of recent multiple Indicator cluster surveys. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2148. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12193-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munaw MB, Tegegn MT. Visual impairment and psychological distress among adults attending the University of Gondar tertiary eye care and training center, Northwest Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bookwala J. Marital quality as a moderator of the effects of poor vision on quality of life among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(5):605-616. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng Y, Lamoureux EL, Chiang PP, Rahman Anuar A, Wong TY. Marital status and its relationship with the risk and pattern of visual impairment in a multi-ethnic Asian population. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014;36(1):104-110. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martire LM, Helgeson VS. Close relationships and the management of chronic illness: associations and interventions. Am Psychol. 2017;72(6):601-612. doi: 10.1037/amp0000066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, Li D, Mishra SR, et al. Association between marital relationship and multimorbidity in middle-aged adults: a longitudinal study across the US, UK, Europe, and China. Maturitas. 2022;155:32-39. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernbaum M, Albert SG, Duckro PN, Merkel W. Personal and family stress in individuals with diabetes and vision loss. J Clin Psychol. 1993;49(5):670-677. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees G, Xie J, Holloway EE, et al. Identifying distinct risk factors for vision-specific distress and depressive symptoms in people with vision impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(12):7431-7438. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi HG, Lee MJ, Lee SM. Visual impairment and risk of depression: a longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2083. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20374-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Aa HP, Comijs HC, Penninx BW, van Rens GH, van Nispen RM. Major depressive and anxiety disorders in visually impaired older adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):849-854. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Aa HP, Hoeben M, Rainey L, van Rens GH, Vreeken HL, van Nispen RM. Why visually impaired older adults often do not receive mental health services: the patient’s perspective. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(4):969-978. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0835-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su NH, Moxon NR, Wang A, French DD. Associations of social determinants of health and self-reported visual difficulty: analysis of the 2016 National Health Interview Survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020;27(2):93-97. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2019.1680703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elam AR, Andrews C, Musch DC, Lee PP, Stein JD. Large disparities in receipt of glaucoma care between enrollees in Medicaid and those with commercial health insurance. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(10):1442-1448. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Accessed2022. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- 32.Mehraban Far P, Tai F, Ogunbameru A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of teleretinal screening for detection of diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2022;7(1):e000915. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2021-000915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashrafzadeh S, Gundlach BS, Tsui I. Implementation of teleretinal screening using optical coherence tomography in the Veterans Health Administration. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(8):898-904. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2021.0118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuo T, Matsuo C, Kayano M, Mitsufuji A, Satou C, Matsuoka H. Photorefraction with spot vision screener versus visual acuity testing as community-based preschool vision screening at the age of 3.5 years in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8655. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Moraes CG, Hark LA, Saaddine J. Screening and Interventions for Glaucoma and Eye Health Through Telemedicine (SIGHT) studies. J Glaucoma. 2021;30(5):369-370. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hark LA, Tan CS, Kresch YS, et al. Manhattan vision screening and follow-up study in vulnerable populations: 1-month feasibility results. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(10):1597-1604. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2021.1905000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolomeyer NN, Katz LJ, Hark LA, et al. Lessons learned from 2 large community-based glaucoma screening studies. J Glaucoma. 2021;30(10):875-877. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]