Abstract

Previous studies have suggested that sensory overresponsivity in youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may be due to a failure to habituate to stimuli. We examined the relationship between performance on three tactile psychophysical tasks and the construct of sensory overresponsivity in children with and without ASD. Sensory overresponsivity predicted amplitude discrimination with an adapting stimulus, as well as the effect of adaptation, for ASD youth. Results replicate previous research that children with ASD are less affected by the presence of an adapting stimulus as compared to typically developing children, and further suggest that sensory overresponsivity may be the mechanism underlying the observed lack of an adaptation effect in children with ASD.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, amplitude discrimination, sensory overresponsivity, tactile processing

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) includes hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or an unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment as a new diagnostic criterion of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Indeed, up to 95 percent of parents of children with ASD have reported their child to have differences in sensory processing (Rogers & Ozonoff, 2005), with other estimates suggesting atypical sensory features in over 90 percent of children and adults with ASD (Crane, Goddard, & Pring, 2009; Leekam, Nieto, Libby, Wing, & Gould, 2007; Tomchek & Dunn, 2007). Previous research has indicated significantly elevated levels of sensory symptoms in children with ASD compared with children with typical development, and that the severity of these sensory features is related to adaptive functioning in children with ASD (Rogers, Hepburn, & Wehner, 2003).

Differences in sensory processing can be classified in a variety of ways. For instance, sensory features are often described in terms of categories such as hyporesponsiveness, hyperresponsiveness, and sensory interests, repetitions, and/or seeking behaviors (Ausderau et al., 2014b). Specifically, differences in sensory processing can be framed in terms of an increased or adverse response (hyperreactivity) or a decreased or lessened response (hyporeactivity) to sensory stimuli (Dunn & Brown, 1997; Siper, Kolevzon, Wang, Buxbaum, & Tavassoli, 2017). Similarly, the terms sensory overresponsivity, sensory underresponsivity, and sensory seeking have been used to describe the behavioral dimensions of sensory modulation (Miller, Anzalone, Lane, Cermak, & Osten, 2007; Patten, Ausderau, Watson, & Baranek, 2013). Sensory overresponsivity has been defined as an exaggerated, rapid onset, or prolonged reaction to sensation; sensory underresponsivity as lack of awareness or a slow response to sensory stimulation; and sensory seeking as craving or interest in sensory input (Ben-Sasson et al., 2008). Previous work has also suggested that some individuals with ASD display tactile defensiveness, meaning an exhibition of behavioral and emotional responses that are out of proportion to tactile stimuli that most people deem non-painful (Baranek & Berkson, 1994; Baranek, Foster, & Berkson, 1997). Importantly, these sensory patterns may co-occur within individuals with ASD, such that a child may demonstrate hyporesponsiveness in one sensory modality but hyperresponsiveness in another (Ausderau et al., 2014a; Iarocci & McDonald, 2006; Lane, Young, Baker, & Angley, 2011).

In particular, the term ‘sensory overresponsivity’ has been used to indicate an automatic or exaggerated response to sensory input, which may result in negative emotional responses or the avoidance of certain sensory stimuli (Schaaf & Lane, 2015; Schoen, Miller, & Green, 2008). Previous research indicates that an estimated 56 to 70 percent of youth with ASD demonstrate sensory overresponsivity (Baranek, David, Poe, Stone, & Watson, 2006; Ben-Sasson et al., 2007). Additionally, sensory overresponsivity has been associated with greater anxiety and functional impairment in individuals with ASD (Green & Ben-Sasson, 2010; Liss, Saulnier, Fein, & Kinsbourne, 2006).

Previous research has suggested that sensory overresponsivity may be due to a failure to habituate to stimuli (Green et al., 2015). Specifically, Green et al. (2015) examined brain responses and habituation to aversive tactile and auditory stimuli using functional magnetic resonance imaging in a sample of 19 youths with ASD and 19 age- and IQ-matched typically developing controls. The authors found that the extent of activation measured by blood oxygen level-dependent response in sensory cortices, the amygdala, and the insula was correlated with the severity of sensory overresponsivity within the ASD cohort. Additionally, habituation analyses found group differences in habituation in the amygdala and somatosensory cortices, such that the typically developing and ASD groups began with similar levels of activation which decreased over time, but that the typically developing cohort habituated to stimuli more quickly. Further, when the ASD group was divided into those with and without sensory overresponsivity, the subgroup of youth with ASD and sensory overresponsivity was found to habituate more slowly and to demonstrate higher activity levels than the subgroup of youth with ASD who did not demonstrate sensory overresponsivity and the typically developing comparison group. These results suggest that overreactive brain responses to sensory stimuli are specific to youth with ASD who demonstrate elevated sensory overresponsivity.

Previous studies investigating tactile processing using psychophysical methods have supported the idea that children with ASD demonstrate differences in inhibitory mechanisms, which may affect their ability to filter sensory information (Puts, Wodka, Tommerdahl, Mostofsky, & Edden, 2014; Tavassoli et al., 2016). Specifically, Puts et al. (2014) investigated tactile processing in a sample of 67 typically developing (TD) children and 32 children with ASD using a vibrotactile battery consisting of 10 tasks. Previous research with TD adults and children has shown that the presence of an adapting stimulus increases the threshold for tactile discrimination of a stimulus (Tommerdahl, Favorov, & Whitsel, 2010). In fitting with this work, Puts et al. (2014) found that performance significantly worsened after single-site adaptation compared with no adaptation for TD children; however, the effect of adaptation was not observed in the ASD group, such that children with ASD were unaffected by an increasing subthreshold stimulus. The authors related this finding to impaired modulation of lateral inhibitory connections in ASD, which they suggested might relate to differences in habituation within this population.

Expanding upon the work of Puts et al. (2014), Tavassoli et al. (2016) examined static and dynamic tactile thresholds in a sample of 21 children with ASD and 21 TD children, comparing the dynamic to the static threshold to obtain a proxy measure of the amount of feed-forward inhibition. The static task began with a suprathreshold vibration, followed by a vibration of lower amplitude (i.e., one that was more difficult to detect). Conversely, in the dynamic task, the vibration began with zero amplitude, with amplitude increased until the participant could detect the vibration. In fitting with previous studies, Tavassoli et al. (2016) found a significant difference between static and dynamic thresholds in the TD group, but not the ASD group, suggesting reduced inhibition in children with ASD. The authors posited that less GABAergic mediated inhibition in children with ASD might explain the lack of an observed difference in static and dynamic thresholds in this group. Additionally, Tavassoli et al. (2016) found that the ratio of dynamic to static thresholds was negatively correlated with scores on the repetitive behavior domain of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2012), such that the lower the ratio, the more repetitive behaviors.

Taken together, these studies provide an explanation for a possible mechanism that may be responsible for differences in tactile processing in ASD: namely, decreased inhibition may contribute to difficulties with sensory processing, as well as ASD symptoms as a whole. It is unknown, however, how behavioral performance on tactile processing tasks may relate to the construct of sensory overresponsivity and vice versa. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to examine the relationship between performance on three amplitude discrimination tasks—two without adaptation and one with an adapting stimulus—and sensory overresponsivity in a group of TD children and children with ASD.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 50 children between the ages of 6 and 17 years: 25 typically developing children (Mage: 12.5 years, SD = 2.8 years; 12 female) and 25 children with ASD (Mage: 12.3 years, SD = 3.1 years; 4 female). Groups did not differ significantly in age, full-scale IQ, or the Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, 2nd edition (WASI-II; Wechsler, 2011). Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. Informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian of each child, and informed assent was obtained from each child.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variable |

TD (n=25) Mean (SD) |

ASD (n=25) Mean (SD) |

t Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 12.5 (2.8) | 12.3 (3.1) | .288 |

| WASI-II | |||

| Full-scale | 111.72 (10.9) | 105.56 (13.6) | 1.758 |

| Verbal Comprehension | 110.96 (9.4) | 101.32 (15.0) | 2.718* |

| Perceptual Reasoning | 109.60 (13.1) | 109.16 (16.1) | .106 |

| Sensory Profile score | |||

| Visual/Auditory sensitivity | 7.68 (2.9) | 12.88 (4.5) | −4.891** |

| Auditory filtering | 9.96 (4.2) | 18.68 (4.2) | −7.377** |

| Tactile sensitivity | 4.04 (1.3) | 5.12 (2.2) | −2.107* |

| Sensory overresponsivity total score | 21.56 (7.6) | 36.64 (8.2) | −6.771** |

p < .05.

p < .001.

Participants in the ASD cohort met DSM-5 criteria for ASD, which was confirmed by the ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2012) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Rutter et al., 2003). Participants in the typically developing cohort were excluded if they had non-corrected vision or auditory problems, were prescribed psychoactive medication, or had a history of psychiatric or educational difficulties as assessed by a parent history questionnaire.

Sensory Overresponsivity

Parents of child participants completed the Sensory Profile (Dunn, 1999) or the Sensory Profile 2 (Dunn, 2014), depending on the time of enrollment into the study. Data were collected from April 2014 to February 2017. The Sensory Profile is a judgment-based caregiver questionnaire consisting of items that describe children’s responses to various sensory experiences, thus providing a standardized way in which to capture a child’s behaviors during the course of daily life. The frequency of the child’s responses to various sensory experiences are rated using a five-point scale, with each response on the scale weighted with a score from 1 to 5.

The Sensory Profile (Dunn, 1999) was revised as the Sensory Profile 2 (Dunn, 2014). In the original version of the Sensory Profile, “Almost Always” yielded a score of one, such that a lower score indicated worse performance; however, the order of ratings was reversed in the Sensory Profile 2, such that “Almost Always” yielded a score of five. Therefore, the Sensory Profile was reverse-scored for all participants who had completed the measure in order to match the ratings of the Sensory Profile 2.

Green et al. (2015) previously measured sensory overresponsivity using the Short Sensory Profile (McIntosh, Miller, & Shyu, 1999) and the Sensory Over-Responsivity Scales (Schoen, Miller, & Green, 2008) by standardizing and averaging the auditory and visual sensitivity, tactile sensitivity, and auditory filtering subscales of the former measure and auditory and tactile scores of the latter measure. In the current experiment, items from the Sensory Profile and Sensory Profile 2 were translated to match the visual/auditory sensitivity, auditory filtering, and tactile sensitivity subscales of the Short Sensory Profile. The Short Sensory Profile isolates items related to sensory processing and thus is less confounded by items overlapping with diagnostic features of autism (Tomchek & Dunn, 2007). Notably, four items on the tactile sensitivity subscale differed between the Sensory Profile and Sensory Profile 2. Items that were not consistent between the two versions of the Sensory Profile were removed, resulting in a tactile sensitivity subscale composed of three items. Scores on this subscale and the visual/auditory sensitivity and auditory filtering subscales of the Short Sensory Profile were summed to create a sensory overresponsivity total score for each participant. The 14 items comprising the sensory overresponsivity total score are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Short Sensory Profile (Dunn, 2014) Items Comprising the Sensory Overresponsivity Total Score

| Short Sensory Profile Domain | Item Description |

|---|---|

| Tactile sensitivity | Item 1: Expresses distress during grooming Item 4: Reacts emotionally or aggressively to touch Item 7: Rubs or scratches out a spot that has been touched |

| Auditory filtering | Item 22: Is distracted or has trouble functioning if there is a lot of noise around Item 23: Appears to not hear what you say Item 24: Can’t work with background noise Item 25: Has trouble completing tasks when the radio is on Item 26: Doesn’t respond when name is called but you know the child’s hearing is OK Item 27: Has difficulty paying attention |

| Visual/Auditory sensitivity | Item 34: Responds negatively to unexpected or loud noises Item 35: Holds hands over ears to protect from sound Item 36: Is bothered by bright lights after others have adapted to the light Item 37: Watches everyone when they move around the room Item 38: Covers eyes or squints to protect eyes from light |

Stimulus Delivery

A CM4 four-digit tactile stimulator (Cortical Metrics) was used for stimulation (Holden et al., 2012). Stimuli were delivered to the glabrous skin of the left hand on digit 2 (LD2; index finger) and digit 3 (LD3; middle finger) using a cylindrical probe (5 mm in diameter). All stimuli were presented within the flutter range (25–50 Hz). Visual feedback, task responses, and data collection were performed on an Acer Onebook Netbook computer running CM4 software (Holden et al., 2012). The tactile battery took approximately 30 to 40 minutes to complete and consisted of 10 separate tasks. Only three of the tasks were examined in the present study, all of which were amplitude discrimination tasks [1) no adaptation—simultaneous; 2) dual site—sequential; and 3) single-site adaptation].

Experimental Design

Each task was preceded by three consecutive practice trials requiring a correct response to ensure that participants understood the task instructions before proceeding to the experimental task. Feedback was given during practice trials only. Stimulus delivery was pseudorandomized between LD2 and LD3 for all tasks. Responses were obtained using a mouse click from the participant’s right hand. Stepwise tracking was used for all conditions: the tested parameter was modulated with 1 up/1 down tracking for the first 10 trials and a 2 up/1 down tracking for the remainder of the task, such that difficulty was increased for correct answers and decreased for incorrect answers. Amplitude discrimination thresholds were taken as the mean amplitude of the last five trials.

Amplitude discrimination threshold: no adaptation—simultaneous.

In the no adaptation condition, two stimuli were simultaneously delivered on LD2 and LD3, with one of the stimuli having a higher amplitude, and both stimuli with frequency 25 Hz, duration 500 ms (standard stimulus amplitude: 200 µm; initial comparison stimulus amplitude: 400 µm; inter-trial interval [ITI] = 5 s; 20 trials). Participants were asked to determine which of the two stimuli had the higher amplitude.

Amplitude discrimination threshold: dual site—sequential.

The sequential condition used the same stimulus parameters and the same tracking paradigm as the no adaptation, simultaneous condition with the exception that the two stimuli were delivered 500 ms apart on each trial.

Amplitude discrimination threshold: single-site adaptation.

In the single-site adaptation condition, each trial was preceded by an adapting stimulus delivered to a single digit (amplitude 200 µm, duration 500 ms) before the comparison stimulus. Participants were told to ignore the adapting stimulus, and determine which of the two stimuli had the higher amplitude.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using JASP Version 8.0.1 (JASP Team, 2016). Bayesian paired samples t-tests were conducted for each group on the difference between each of the amplitude discrimination tasks without adaptation (no adaptation—simultaneous and dual site—sequential) tasks and the amplitude discrimination task with adaptation (single-site adaptation). Each of the tasks, as well as the effect of adaptation, as measured by the difference between tasks with and without adaptation, were correlated with age to examine whether performance on these tasks varied developmentally. Finally, regression analyses were conducted to determine whether sensory overresponsivity predicted performance on the amplitude discrimination tasks, as well as whether amplitude discrimination thresholds predicted sensory overresponsivity.

Results

Effect of Adaptation on Amplitude Discrimination

Data were examined by estimating a Bayes factor using Bayesian Information Criteria (Wagenmakers, 2007), comparing the fit of the data under the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis. Bayes factors (BF) provide a numerical value that quantifies how well a hypothesis predicts the empirical data relative to a competing hypothesis; in other words, the BF is a measure of the strength of the relative evidence in the data (Goodman, 1999). The BF10 expresses support for the alternative hypothesis over the null hypothesis, whereas the BF01 expresses support for the null hypothesis over the alternative hypothesis. Given that previous research has demonstrated a lack of an adaptation effect in individuals with ASD (Puts et al., 2014), the BF01 was used to examine differences between tasks with and without adaptation in ASD and TD youth.

Paired Bayesian t-tests on the difference between the dual site—sequential and single-site adaptation tasks provided strong evidence for the alternative hypothesis of a significant difference in performance in TD youth, and anecdotal evidence for the alternative hypothesis of a significant difference in performance in ASD youth. Paired Bayesian t-tests on the difference between the no adaptation—simultaneous and single-site adaptation tasks provided anecdotal evidence for the null hypothesis of no significant difference in performance in TD youth, and moderate evidence for the null hypothesis of no significant difference in performance in ASD youth. Results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Difference in amplitude discrimination with and without adaptation

| TD | ASD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Tasks | BF 01 | Interpretation | BF 01 | Interpretation |

| Dual site—sequential/Single-site adaptation | .047 | Strong evidence for H1 | .520 | Anecdotal evidence for H1 |

| No adaptation—simultaneous/Single-site adaptation | 1.548 | Anecdotal evidence for H0 | 4.012 | Moderate evidence for H0 |

Age and Amplitude Discrimination Performance

Pearson correlations were performed to test the relationship between age and performance on each of the amplitude discrimination tasks. There was a significant negative relationship between age and performance on the dual site—sequential, no adaptation—simultaneous, and single-site adaptation tasks for the TD youth, but not the ASD youth. Additional correlational analyses were performed to test the association between age and the effect of adaptation, measured as the difference between single-site adaptation and each of the non-adapted tasks (dual site—sequential and no adaptation—simultaneous). Correlations were not significant for either difference score (single-site adaptation – no adaptation—simultaneous; single-site adaptation – dual site—sequential) in neither TD nor ASD youth. Results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlations between age and amplitude discrimination performance

| Group | Age (months) | Sequential | Simultaneous | SSA | SSA –sequential | SSA –simultaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (TD) | 1 | −0.510** | −0.689** | −0.404* | −0.243 | .078 |

| Age (ASD) | 1 | −0.224 | −0.207 | 0.043 | .192 | .371 |

Sequential = Dual site—sequential; Simultaneous = No adaptation—simultaneous; SSA = Single-site adaptation.

Note. N=50 (TD, n=25; ASD, n=25).

p < .05.

p < .001.

Sensory Overresponsivity and Amplitude Discrimination

Linear regression analyses were used to test if sensory overresponsivity significantly predicted performance on the three amplitude discrimination tasks for each group. Results are presented in Table 5. Age was entered as a covariate in all analyses, given its significant correlation with performance on the three amplitude discrimination tasks in the TD cohort. Sensory overresponsivity did not significantly predict the difference on any of the amplitude discrimination tasks, nor between adaptation and non-adaptation for either pair of tasks (single-site adaptation – no adaptation—simultaneous; single-site adaptation – dual site—sequential) for TD youth. In contrast, in the ASD group, sensory overresponsivity significantly predicted performance on the single-site adaptation task. In addition, sensory overresponsivity significantly predicted the difference between adaptation and non-adaptation for both tasks (single-site adaptation – no adaptation—simultaneous; single-site adaptation – dual site—sequential) in the ASD group. Importantly, children with ASD had significantly greater sensory overresponsivity total scores than did TD children, t(48) = −6.771, p < .001.

Table 5.

Sensory Overresponsivity as a Predictor of Amplitude Discrimination

| TD |

ASD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | Std. Error B | β | t | p | B | Std. Error B | β | t | p |

| Sequential | 1.24 | 1.22 | .232 | 1.02 | .318 | .267 | 1.34 | .037 | .199 | .844 |

| Simultaneous | 2.45 | 1.91 | .242 | 1.28 | .213 | −1.7 | 2.13 | −.14 | −.81 | .428 |

| SSA | 3.46 | 3.55 | .236 | .976 | .340 | 5.73 | 2.54 | .423 | 2.26 | .034* |

| SSA-Sequential | 2.22 | 3.43 | .168 | .647 | .524 | 5.47 | 2.16 | .477 | 2.536 | .019* |

| SSA-Simultaneous | 1.01 | 3.59 | .076 | .282 | .781 | 7.45 | 3.05 | .454 | 2.44 | .023* |

Sequential = Dual site—sequential; Simultaneous = No adaptation—simultaneous; SSA = Single-site adaptation.

p < .05.

Multiple regression analyses were also used to test if performance on the three amplitude discrimination tasks significantly predicted sensory overresponsivity in each group. Age was entered as a covariate in both regressions due to its significant correlation with task performance in the TD cohort. In the TD group, results of the regression indicated that the three predictors collectively explained 47.3 percent of the variance [R2 = .473, F(4, 20) = 4.489, p = .009]. None of the amplitude discrimination tasks significantly predicted sensory overresponsivity. In the ASD group, results of the regression indicated that collectively, the three predictors did not significantly predict sensory overresponsivity [R2 = .238, F(3,21) = 2.189, p = .119]; however, the single-site adaptation task was found to significantly predict sensory overresponsivity in this group [β = .543, t(21) = 2.404, p = .026].

In the TD group, results of the regression indicated that the difference between adaptation and non-adaptation across both tasks (single-site adaptation – no adaptation—simultaneous; single-site adaptation – dual site—sequential) explained 39 percent of the variance [R2 = .39, F(3,21) = 4.48, p = .014]. Importantly, however, neither of the difference scores significantly predicted sensory overresponsivity in the TD cohort after accounting for the effect of age. Similarly, the difference between adaptation and non-adaptation for both tasks (single-site adaptation – no adaptation—simultaneous; single-site adaptation – dual site—sequential) did not significantly predict sensory overresponsivity for ASD children [R2 = .234, F(2,22) = 3.364, p = .053].

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to examine amplitude discrimination performance in a group of TD and ASD children in the context of a set of vibrotactile psychophysics tasks. Our results show that children with ASD are less affected by the presence of an adapting stimulus as compared to TD children, replicating previous studies of this phenomenon in both adults and children with ASD (Puts et al., 2014; Puts et al., 2017; Tannan et al., 2008). The present study extends this literature by relating performance on these vibrotactile tasks to the construct of sensory overresponsivity in TD and ASD children.

Sensory overresponsivity as rated via parent report was greater for ASD children than for TD children, in agreement with the extant literature, which suggests that elevated levels of sensory overresponsivity are highly prevalent in this population (Baranek et al., 2006; Ben-Sasson et al., 2009; Mazurek et al., 2013).

Results of the current study suggest that sensory overresponsivity predicts amplitude discrimination with single-site adaptation for children with ASD. Additionally, sensory overresponsivity also predicted the difference between adaptation and non-adaptation for both amplitude discrimination tasks (single-site adaptation – no adaptation—simultaneous; single-site adaptation – dual site—sequential) in the ASD group. This may indicate that sensory overresponsivity has a differential impact upon tactile performance, such that the level of sensory overresponsivity may account for cases in which the effect of adaptation is not observed. In contrast, sensory overresponsivity did not significantly predict performance on any of the three amplitude discrimination tasks for TD children. Consequently, it appears that sensory overresponsivity has a unique and specific impact upon tactile processing in children with ASD.

When entered as predictor variables, none of the amplitude discrimination tasks significantly predicted sensory overresponsivity for TD youth. On the other hand, however, the single-site adaptation task was a significant predictor of sensory overresponsivity for children with ASD. These results provide support for a bidirectional relationship between sensory overresponsivity and the effect of adaptation, such that the behavioral responses to tactile stimuli of children with ASD are affected by the degree of sensory overresponsivity, and that adaptation within tactile processing exerts an impact upon sensory overresponsivity within children with ASD. By extension, these results suggest that sensory overresponsivity may be the mechanism underlying the observed lack of an adaptation effect in individuals with ASD; however, it is also possible that this relationship may be better explained by a third variable that was not specifically investigated in the current study.

The present study also provides support for the notion that the effect of adaptation on tactile processing is stable across time, given that correlations were not significant between age and the effect of adaptation in neither TD nor ASD youth. Interestingly, performance on all three amplitude discrimination tasks significantly improved with age for TD youth, but not ASD youth. This may suggest that tactile processing is more stable across development in children with ASD, such that increasing age does not affect tactile amplitude discrimination capacity in this population.

Although the current study suggests that sensory overresponsivity levels may explain differences in tactile processing in ASD, there are other possible explanations. For instance, previous research has proposed that differences in tactile processing are a result of decreased feed-forward inhibition and altered GABA function in individuals with ASD (Puts et al., 2017; Tavassoli et al., 2016). As the present study did not specifically investigate GABA, it is unknown to what extent altered GABA function may explain the construct of sensory overresponsivity. Further exploration of the relationship between GABA function and sensory overresponsivity may elucidate a common mechanism that is responsible for or alternatively explains the differences in tactile performance in children with ASD.

The present study is necessarily limited by its use of a small sample of children of a wide range of ages, which likely contributed to the large variability observed in individual responses in both cohorts. Previous research has indicated age differences in sensory overresponsivity in both ASD and comparison groups, with older participants demonstrating fewer sensory differences than younger participants (Crane, Goddard, & Ping, 2009). In addition, the notable discrepancy in sex ratio between the TD and ASD groups is an important consideration when interpreting the present findings. Specifically, the TD group has a more even distribution between males and females, whereas the ASD group includes a majority of males, which is commensurate with population estimates of ASD prevalence (Baio et al., 2018). The extant literature is limited in its exploration of sex differences in sensory responsivity and sensitivity. However, a previous study by Lai, Lombardo, and Pasco (2011) indicated that women with ASD reported more sensory difficulties than men with ASD do. Future research may wish to consider the impact of sex differences upon sensory overresponsivity within tactile psychophysics tasks, and upon the construct of sensory overresponsivity more generally.

In the present study, the construct of sensory overresponsivity was measured by creating a subscale from 14 items of the Short Sensory Profile. Although the Short Sensory Profile has acceptable internal consistency (α = .70 to .90) and discriminant validity in distinguishing children with and without sensory processing difficulties (McIntosh, Miller, & Shyu, 1999), the reliability and validity of our own measure of sensory overresponsivity is undetermined. Consequently, the unknown psychometrics of our proxy measurement of the construct of sensory overresponsivity poses a significant limitation to the current study. In addition, the use of a limited number of questions from a parent report of sensory symptoms as a proxy measure of sensory overresponsivity may obscure the true nature of sensory overresponsivity in these children. Use of a clinician-administered behavioral measure, in addition to a rating scale, such as the Sensory Over-Responsivity Scales (SensOR; Schoen et al., 2008), may provide a more thorough and valid assessment of sensory overresponsivity in this population.

Differences in tactile sensitivity within and across individuals are also an important consideration. Many children with ASD demonstrate different patterns of responses to various forms of tactile stimuli. For instance, some children may overreact to weak tactile input, such as a light touch on the head or body, whereas others may not respond to intense pain stimuli (Guclu, Tanidir, Mukaddes, & Unal, 2006). In previous work by Elwin, Ek, Schroder, and Kjellin (2012) that included autobiographical accounts of sensory experiences, individuals with ASD reported strong and heightened reactions to external tactile stimuli in addition to a lessened response to pain stimuli and proprioception. Studies using psychophysical assessment have also presented conflicting results, likely due to differences in the form of tactile stimulation used (Blakemore et al., 2006; Cascio et al., 2008; Puts et al., 2014). Consequently, it is unknown to what extent these results would generalize to another type of tactile stimulation.

Even though the extant literature indicates that a majority of individuals with ASD demonstrate elevated sensory overresponsivity, there is little research examining sensory overresponsivity in typically developing (TD) individuals. Consequently, it is largely unknown to what extent sensory overresponsivity is specific to ASD, or whether it is better explained as a nonspecific construct that exists independent of diagnostic categories. Therefore, additional research concerning tactile processing and responsivity should incorporate typically developing children of a variety of ages, and compare these groups to children with various developmental disabilities and other psychological diagnoses. Overall, however, results of the present study provide preliminary evidence for the idea that sensory overresponsivity has a unique impact on tactile processing differences observed in children with ASD, with future research necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which this phenomenon occurs.

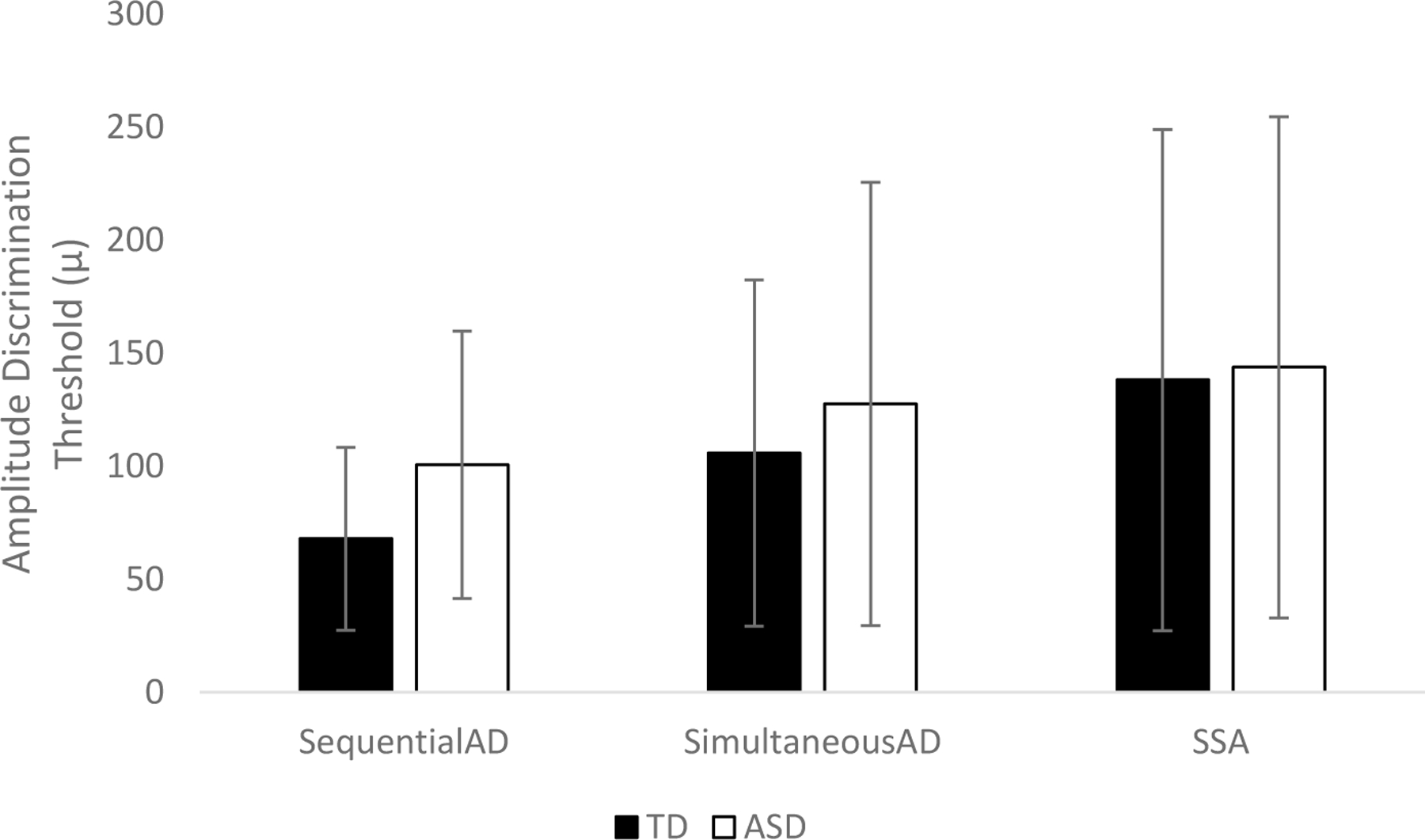

Fig. 1.

Amplitude discrimination performance in TD and ASD children.

SequentialAD = Dual site—sequential; SimultaneousAD = No adaptation—simultaneous; SSA = Single-site adaptation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our undergraduate research assistants for their dedication and commitment to the CARE Lab. We would also like to thank the families and children who graciously gave their time for this research.

Funding

This project was made possible by grant support from a grant from the Hill Collaboration on Environmental Medicine-Diseases of the Nervous System to NR, as well as a grant by the National Institutes of Health (1R01MH101536–01) to NR.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest of which they are aware.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.): DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ausderau KK, Furlong M, Sideris J, Bulluck J, Little LM, Watson LR, … & Baranek GT (2014a). Sensory subtypes in children with autism spectrum disorder: Latent profile transition analysis using a national survey of sensory features. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 935–944. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausderau K, Sideris J, Furlong M, Little LM, Bulluck J, & Baranek GT (2014b). National survey of sensory features in children with ASD: Factor structure of the sensory experience questionnaire 3.0. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 915–925. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1945-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, … & Dowling NF (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67 (No. SS-6): 1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, & Berkson G (1994). Tactile defensiveness in children with developmental disabilities: Responsiveness and habituation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 24, 457–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02172128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, Foster LG, & Berkson G (1997). Tactile defensiveness and stereotyped behaviors. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(2), 91–95. doi: 10.5014/ajot.51.2.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, David FJ, Poe MD, Stone WL, & Watson LR (2006). Sensory experiences questionnaire: Discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Cermak SA, Orsmond GI, Tager-Flusberg H, Carter AS, Kadlec MB, & Dunn W (2007). Extreme sensory modulation behaviors in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Cermak SA, Orsmond GI, Tager-Flusberg H, Kadlec MB, & Carter AS (2008). Sensory clusters of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Differences in affective symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 817–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, & Gal E (2009). A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Tavassoli T, Calo S, Thomas RM, Catmur C, Frith U, & Haggard F (2006). Tactile sensitivity in Asperger syndrome. Brain Cognition, 61, 5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio C, McGlone F, Folger S, Tannan V, Baranek G, Pelphrey KA, & Essick G (2008). Tactile perception in adults with autism: A multidimensional psychophysical study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 127–137. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0370-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L, Goddard L, & Pring L (2009). Sensory processing in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 13, 215–228. doi: 10.1177/1362361309103794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W (1999). Sensory profile: User’s manual San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W (2014). Sensory profile 2: User’s manual San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W, & Brown C (1997). Factor analysis on the sensory profile from a national sample of children without disabilities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(7), 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwin M, Ek L, Schroder A, & Kjellin L (2012). Autobiographical accounts of sensing in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26, 420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco EM, Holden JK, Nguyen RH, Favorov OV, & Tommerdahl M (2015). Percept of the duration of a vibrotactile stimulus is altered by changing its amplitude. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 9, 77. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SN (1999). Toward evidence-based medical statistics. 2: The Bayes factor. Annals of Internal Medicine, 130, 1005–1013. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-12-199906150-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, & Ben-Sasson A (2010). Anxiety disorders and sensory overresponsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders: Is there a causal relationship? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1495–1504. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1007-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, Hernandez L, Tottenham N, Krasileva K, Bookheimer SY, & Dapretto M (2015). Neurobiology of sensory overresponsivity in youth with autism spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(8), 778–786. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guclu B, Tanidir C, Mukaddes NM, & Unal F (2006). Tactile sensitivity of normal and autistic children. Somatosensory and Motor Research, 24(1–2), 21–33. doi: 10.1080/08990220601179418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden JK, Nguyen RH, Francisco EM, Zhang Z, Dennis RG, & Tommerdahl M (2012). A novel device for the study of somatosensory information processing. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 204, 215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iarocci G, & McDonald J (2006). Sensory integration and the perceptual experience of persons with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 77–90. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0044-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team (2016). JASP (Version 0.8.0.1) [Computer software]

- Lai M, Lombardo M, & Pasco G (2011). A behavioral comparison of male and female adults with high functioning autism spectrum conditions. PLoS One, 6(6), 20835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AE, Young RL, Baker AEZ, & Angley MT (2011). Sensory processing subtypes in autism: Association with adaptive behavior. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(1), 112–122. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0840-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leekam SR, Nieto C, Libby SJ, Wing L, & Gould J (2007). Describing the sensory abnormalities of children and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 894–910. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Saulnier C, Fein D, & Kinsbourne M (2006). Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism, 10(2), 155–172. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, & Bishop S (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd Edition (ADOS-2) Torrance: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Vasa RA, Kalb LG, Kanne SM, Rosenberg D, Keefer A, … & Lowery LA (2013). Anxiety, sensory over-responsivity, and gastrointestinal problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(1), 165–176. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9668-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DN, Miller LJ, & Shyu V (1999). Development and validation of the Short Sensory Profile. In Dunn W (Ed.), Sensory Profile manual (pp. 59–73). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ, Anzalone ME, Lane SJ, Cermak SA, & Osten ET (2007). Concept evolution in sensory integration: A proposed nosology for diagnosis. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten E, Ausderau KK, Watson LR, & Baranek GT (2013). Sensory response patterns in nonverbal children with ASD. Autism Research and Treatment, 2013, 436286. doi: 10.1155/2013/436286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts NAJ, Edden RAE, Wodka EL, Mostofsky SH, & Tommerdahl M (2013). A vibrotactile behavioral battery for investigating somatosensory processing in children and adults. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 218, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts NAJ, Wodka EL, Tommerdahl M, Mostofsky SH, & Edden RAE (2014). Impaired tactile processing in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Neurophysiology, 111, 1803–1811. doi: 10.1152/jn.00890.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts NAJ, Wodka EL, Harris AD, Crocetti D, Tommerdahl M, Mostofsky SH, & Edden RAE (2017). Reduced GABA and altered somatosensory function in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 10(4), 608–619. doi: 10.1002/aur.1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Hepburn S, & Wehner E (2003). Parent reports of sensory symptoms in toddlers with autism and those with other developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 631–642. doi: 10.1023/B:JADD.0000006000.38991.a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, & Ozonoff S (2005). Annotation: What do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1255–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, & Lord C (2003). Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf RC, & Lane AE (2015). Toward a best-practice protocol for assessment of sensory features in ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1380–1395. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2299-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen SA, Miller LJ, & Green KE (2008). Pilot study of the sensory over-responsivity scales: Assessment and inventory. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(4), 393–406. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.4.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons SB, Tannan V, Chiu J, Favorov OV, Whitsel BL, & Tommerdahl M (2005). Amplitude-dependency of response of SI cortex to flutter stimulation. BMC Neuroscience, 6, 43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons SB, Chiu J, Favorov OV, Whitsel BL, & Tommerdahl M (2007). Duration-dependent response of SI to vibrotactile stimulation in squirrel monkey. Journal of Neurophysiology, 97, 2121–2129. doi: 10.1152/jn.00513.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siper PM, Kolevzon A, Wang AT, Buxbaum JD, & Tavassoli T (2017). A clinician-administered observation and corresponding caregiver interview capturing DSM-5 sensory reactivity symptoms in children with ASD. Autism Research, 10(6), 1133–1140. doi: 10.1002/aur.1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannan V, Holden JK, Zhang Z, Baranek GT, & Tommerdahl MA (2008). Perceptual metrics of individuals with autism provide evidence for disinhibition. Autism Research, 1(4), 223–230. doi: 10.1002/aur.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli T, Bellesheim K, Tommerdahl M, Holden JM, Kolevzon A, & Buxbaum JD (2016). Altered tactile processing in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 9, 616–620. doi: 10.1002/aur.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomcheck SD, & Dunn W (2007). Sensory processing in children with and without autism: A comparative study using the Short Sensory Profile. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommerdahl M, Favorov OV, & Whitsel BL (2010). Dynamic representations of the somatosensory cortex. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34, 160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers EJ (2007). A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 14(5), 779–804. doi: 10.3758/BF03194105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2011). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wodka EL, Puts NAJ, Mahone EM, Edden RAE, Tommerdahl M, & Mostofsky SH (2016). The role of attention in somatosensory processing: A multi-trait, multi-method analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 3232–3241. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2866-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]