Abstract

Objective:

To compare the survival outcomes associated with clinical and pathological response in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) with FOLFIRINOX (FLX) or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (GNP) followed by curative-intent pancreatectomy.

Background:

Newer multiagent NAC regimens have resulted in improved clinical and pathological responses in PDAC; however, the effects of these responses on survival outcomes remain unknown.

Methods:

Clinicopathological and survival data of PDAC patients treated at 7 academic medical centers were analyzed. Primary outcomes were overall survival (OS), local recurrence-free survival (L-RFS), and metastasis-free survival (MFS) associated with biochemical (CA 19–9 decrease ≥50% vs <50%) and pathological response (complete, pCR; partial, pPR or limited, pLR) following NAC.

Results:

Of 274 included patients, 46.4% were borderline resectable, 25.5% locally advanced, and 83.2% had pancreatic head/neck tumors. Vein resection was performed in 34.7% and 30-day mortality was 2.2%. R0 and pCR rates were 82.5% and 6%, respectively. Median, 3-year, and 5-year OS were 32 months, 46.3%, and 30.3%, respectively. OS, L-RFS, and MFS were superior in patients with marked biochemical response (CA 19–9 decrease ≥50% vs <50%; OS: 42.3 vs 24.3 months, P < 0.001; L-RFS-27.3 vs 14.1 months, P = 0.042; MFS-29.3 vs 13 months, P = 0.047) and pathological response [pCR vs pPR vs pLR: OS- not reached (NR) vs 40.3 vs 26.1 months, P < 0.001; L-RFS-NR vs 24.5 vs 21.4 months, P = 0.044; MFS-NR vs 23.7 vs 20.2 months, P = 0.017]. There was no difference in L-RFS, MFS, or OS between patients who received FLX or GNP.

Conclusion:

This large, multicenter study shows that improved biochemical, pathological, and clinical responses associated with NAC FLX or GNP result in improved OS, L-RFS, and MFS in PDAC. NAC with FLX or GNP has similar survival outcomes.

Keywords: FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine/nabpaclitaxel, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, outcomes, pancreatic cancer, survival

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains a highly lethal disease.1 It is expected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States by 2020, and has a 5-year overall survival (OS) of approximately 9%.2 Only 15% to 20% of patients are eligible to undergo potentially curative oncologic resection, as most tumors are deemed unresectable at the time of diagnosis due to either locally advanced disease or distant metastases.3 Even of those who undergo surgical resection, 80% recur and die of their disease.3 Factors influencing OS after surgical resection for PDAC include the use of adjuvant therapy and disease-specific factors such as metastases, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), perineural invasion (PNI), histologic tumor grade, nodal disease, and surgical margin status.4

Surgery for PDAC fails to achieve a negative resection margin (R0) in up to 30% to 62% of cases.4 With the recent advent of more effective chemotherapy regimens, efforts have focused on using neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) with or without radiation therapy (RT) to increase the likelihood of achieving an R0 resection and convert unresectable, locally advanced tumors to potentially resectable tumors. NAC may also eradicate occult systemic disease, improve OS, and select poor responders who progress on treatment preoperatively, sparing them from a futile operation. Recently, the Dutch PREOPANC-1 trial was the first Phase 3 randomized study to demonstrate that NAC and RT with gemcitabine followed by resection significantly improved disease-free survival (DFS), metastasis-free survival (MFS), and OS compared with upfront surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine.5

Previous trials have shown that a combination of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRINOX, FLX) or gemcitabine along with nab-paclitaxel (GNP) is associated with improved survival compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic PDAC.6,7 However, randomized trials have not yet evaluated FLX and GNP in patients with nonmetastastic disease. Moreover, the effects of these 2 regimens on clinical and pathological response in the neoadjuvant setting are largely unknown. In this large multicenter series, we sought to analyze the impact of biochemical and pathological response after NAC with FLX or GNP on survival outcomes of patients undergoing pancreatectomy for PDAC.

METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective, multi-institutional study was performed evaluating patients with PDAC undergoing NAC followed by curative-intent pancreatectomy within the Central Pancreas Consortium (CPC) database. The CPC is a multi-institutional research organization focused on addressing biological and surgical questions in pancreatic neoplasms and pancreatic surgery. Through this multicenter approach, single-center biases are assuaged. This study included data from 7 academic institutions: University of Miami Miller School of Medicine/Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Emory University/Winship Cancer Institute, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine/Carbone Cancer Center, University of Louisville School of Medicine/James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of North Carolina School of Medicine/Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Washington University School of Medicine at St. Louis/Siteman Cancer Center. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from each participating institution before initiation of the study.

Patient Demographics, Tumor, and Treatment Variables

Relevant patient variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class, and performance status based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale. Perioperative complications within 90 days from resection were scored by the Clavien-Dindo classification. Clavien grade III or greater were considered severe complications. Data on tumor site and size, major vessel involvement, and lymph node (LN) involvement were documented. Pathological T-stage, N-stage, and overall stage were based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging guidelines 8th edition.8 Perioperative information and data about the type and timing of NAC, including regimen, cycles, and RT modalities were collected. The final analysis only included patients who underwent NAC with FLX or GNP with or without RT followed by curative-intent pancreatectomy. The choice of chemotherapy modality and dosage was selected at the discretion of the medical and/or radiation oncologist at each institution. The protocols were not controlled between the participating centers. Patients who developed distant metastasis, progressed, or died during NAC were excluded, as this was not an intent-to-treat analysis.

Definitions

R1 resection was defined as malignant cells identified at or within 1mm from the surgical margin. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (BRPC) and locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) were defined according to the Alliance classification.9 BRPC consisted of tumors with involvement ≥180° and/or short-segment occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV)/portal vein (PV) amenable to resection and reconstruction. BRPC also included tumors with short-segment interface of any degree with hepatic artery (HA) amenable to arterial resection and reconstruction, and <180° of the circumference interface between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or celiac axis (CA). LAPC was defined as tumors associated with unreconstructible SMV/PV, ≥180° involvement of the CA or SMA, or tumor involvement of the first jejunal SMV branch.9

A cycle of FLX consisted of treatment once every 2 weeks and a cycle of GNP consisted of treatment once a week for 3 weeks and 1 week off. Pathologic response to NAC was graded using the College of American Pathologists (CAP) Cancer protocol.10,11 The CAP method is a 4-tiered system in which a grade 0 indicates a pathological complete response (pCR); grade 1, marked response; grade 2, moderate response, and a grade of 3 indicates either poor or no response.10,11 pCR (ypT0/N0) was defined as no evidence of primary tumor or any LN involvement in the final surgical specimen. Partial pathological response (pPR) included both grade 1 (minimal residual cancer with single cells or small groups of cancer cells) and 2 (residual cancer outgrown by fibrosis). Limited pathological response (pLR) was defined when extensive residual cancer was identified in the surgical specimen.

Normalization of CA 19–9 levels after NAC or surgery was defined as less than 37U/mL. Degree of CA19–9 decreases from the time of diagnosis (with normalized bilirubin levels), through NAC course and at the preoperative period was documented and patients were grouped to those that had ≥50% or <50% decreased levels. Patients with CA 19–9 levels <37 U/mL at the time of diagnosis were excluded from the statistical analysis for biochemical response.

Outcomes

The primary endpoints were OS, local recurrence-free survival (L-RFS), and MFS associated with biochemical (CA 19–9) and pathological response (pCR, pPR or pLR) following NAC. OS was measured from the time from the date of diagnosis until death from any cause. L-RFS was calculated from the time of surgical resection until the date of local recurrence or death. MFS was calculated from the time of surgery until the time of first detectable distant disease or death. Secondary endpoints were LN metastasis and margin positivity.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for patients’ characteristics using median, interquartile range (IQR), frequencies, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). The association of clinicopathological factors among treatments was analyzed. Categorical variables were compared across groups using Chi-squared (X2) or Fisher exact tests as appropriate. Student t test was used to compare continuous measures. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the predictors of LN involvement and calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI and displayed in a forest plot. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method to derive survival curves estimates across treatments, and the log-rank test was used to make comparisons of the survival rates. Each analysis’ statistical significance was determined at an alpha level of 0.05 or less. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

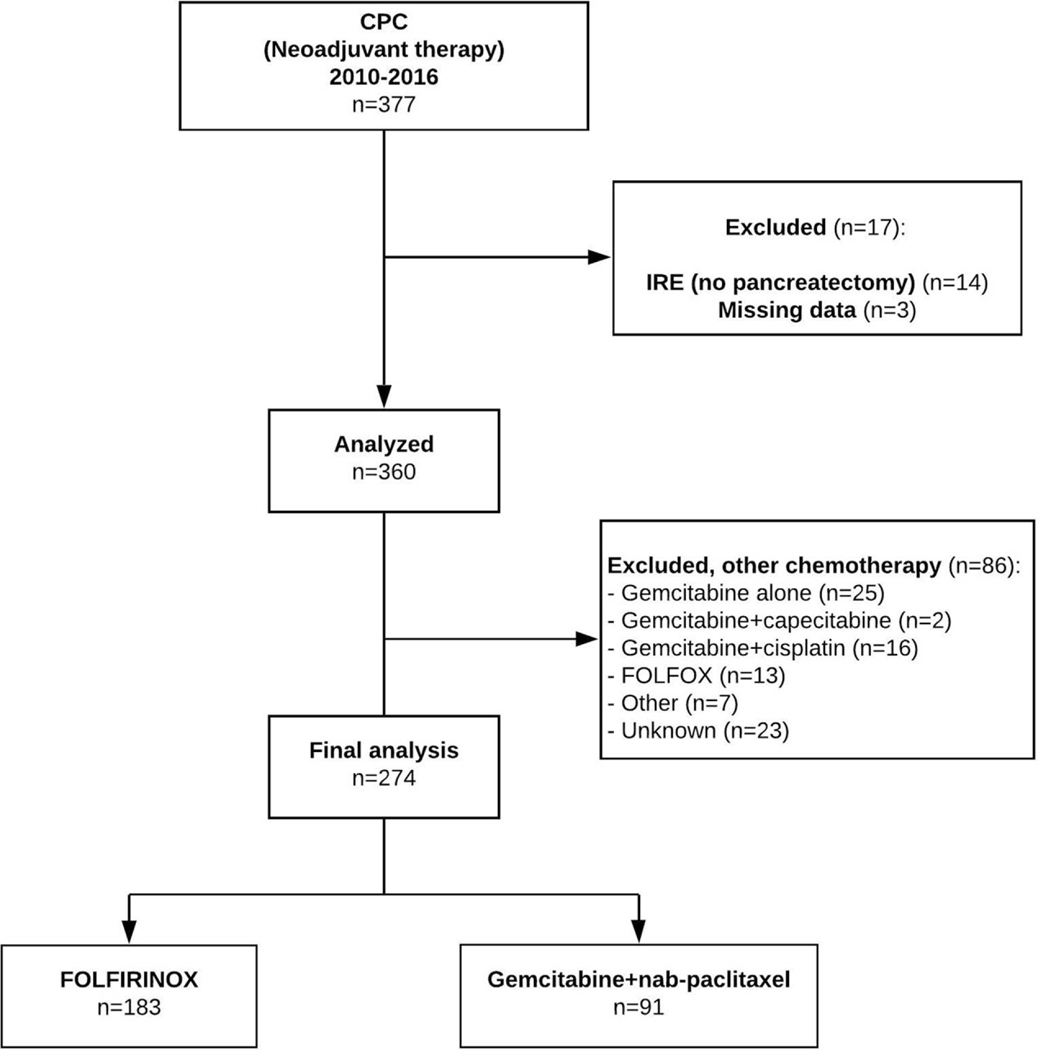

From January 2010 to December 2016, a total of 274 patients at 7 US academic centers received NAC with either FLX or GNP followed by curative-intent pancreatectomy and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Median age was 64 years (IQR: 57.3 to 69). The majority were female (54%), white, non-Hispanics (77%), with ECOG performance status 0 (49.2%). The patient demographic characteristics at baseline were similar between FLX and GNP groups, except for age (62 vs 66 years, P < 0.001, respectively, Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart depicting cohort selection.

TABLE 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

| Total n = 274 | FLX n = 183 | GNP n = 91 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 64 (57.3–69) | 62 (56.5–68) | 66 (61.8–72) | <0.001* |

| Female, n (%) | 148 (54) | 102 (55.7) | 46 (50.5) | 0.442 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 24.9 (22.3–28.9) | 24.9 (22.2–28.6) | 25.4 (22.4–29.1) | 0.38 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 213 (77.7) | 137 (74.9) | 76 (83.5) | |

| African-American | 36 (13.1) | 26 (14.2) | 10 (11) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (6.2) | 14 (7.7) | 3 (3.3) | 0.226 |

| Asian | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1.9) | 5 (2.7) | 0 | |

| ASA | ||||

| 2 | 66 (24) | 48 (26.2) | 18 (19.8) | |

| 3 | 178 (65) | 111 (60.7) | 67 (73.6) | 0.293 |

| 4 | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 26 (9.5) | 21 (11.5) | 5 (5.5) | |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 | 135 (49.2) | 82 (44.8) | 53 (58.2) | |

| 1 | 85 (31) | 63 (34.4) | 22 (24.2) | |

| 2 | 22 (8) | 16 (8.7) | 6 (6.6) | 0.106 |

| 3 | 5 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Unknown | 27 (9.9) | 20 (10.9) | 7 (7.7) | |

| Tumor Location | ||||

| Head/neck | 228 (83.2) | 152 (83.1) | 76 (83.5) | |

| Body | 24 (8.8) | 15 (8.2) | 9 (9.9) | 0.278 |

| Tail | 15 (5.4) | 11 (6) | 4 (4.5) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.6) | 5 (2.7) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Bile duct dilation, (head/neck; n = 228) | 204 (89.4) | 132 (86.8) | 72 (94.7) | 0.165 |

| Preoperative stenting (head/neck; n = 228) | 182 (79.8) | 109 (71.7) | 73 (96) | <0.001* |

| Radiological classification at diagnosis | ||||

| Resectable | 61 (22.3) | 40 (21.9) | 21 (23.1) | |

| BRPC | 127 (46.4) | 79 (43.2) | 48 (52.7) | |

| LAPC | 70 (25.5) | 56 (30.6) | 14 (15.4) | 0.034* |

| Unknown | 16 (5.8) | 8 (4.4) | 8 (8.8) |

ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; BRPC, borderline resectable pancreatic cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FLX, FOLFIRINOX; GNP, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel; IQR, interquartile range; LAPC, locally advanced pancreatic cancer,

Statistically significant.

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics

The majority of tumors were located at the head/neck (83.2%) associated with bile duct dilation (89.4%) requiring stent placement (79.8%). The median tumor size on initial imaging was 2.9 cm (IQR: 2.3 to 3.6). Tumors in the FLX group were slightly larger than GNP group [median size, 3.2 cm (IQR: 2.3 to 3.8) vs 2.9 cm (IQR: 2.2 to 3.4), P = 0.029, respectively]. At the time of diagnosis, 46.4% and 25.5% were deemed BRPC and LAPC, respectively. There was a higher proportion of patients with LAPC receiving FLX than GNP (30.6% vs 15.4%, P = 0.034, Table 1).

Treatment

A total of 183 patients (66.7%) received neoadjuvant FLX, while 91 (33.3%) received neoadjuvant GNP. Of these, 216 (78.9%) received a combination of neo- and adjuvant chemotherapy. The median number of NAC cycles for FLX was 5 (IQR: 4 to 6) and for GNP was 3 (IQR: 2 to 4, P < 0.001), and the median number of AC cycles for FLX was 4 (IQR: 2 to 6) and for GNP was 4 (IQR: 3 to 6, P < 0.214) (Table 2). Only 35.6% of patients completed at least 7 cycles of FLX or 4 cycles of GNP. Eight patients who initiated NAC with FLX switched to GNP due to adverse events. One patient receiving GNP crossed over to FLX. Neoadjuvant RT (NRT) was performed in 28.9% of cases, with significant increased utilization in the GNP group (GNP+RT, 37.8% vs FLX+RT, 24.4%, P = 0.032).

TABLE 2.

Surgical and Chemotherapy Data

| Total n = 274 | FLX n = 183 | GNP n = 91 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAC cycles, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 5 (4–6) | 3 (2–4) | <0.001* |

| Neoadjuvant RT, n = 270 | 78 (28.9) | 44 (24.4) | 34 (37.8) | 0.032* |

| SBRT | 17 (6.3) | 17 (6.3) | 6 (6.6) | 0.145 |

| Conventional | 62 (22.8) | 35 (19.3) | 27 (29.7) | |

| AC | 179 (67.8) | 130 (72.6) | 49 (57.6) | 0.017* |

| FLX | 29 (11) | 29 (16.7) | 0 | <0.001* |

| GNP | 35 (13.3) | 18 (10.3) | 17 (19.1) | |

| Gemcitabine | 69 (26.2) | 51 (29.3) | 18 (20.2) | |

| Other/unknown | 46 (25.7) | 32 (24.6) | 14 (28.6) | |

| AC cycles, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 0.214 |

| Adjuvant RT | 47 (17.3) | 36 (19.9) | 11 (12.1) | 0.127 |

| SBRT | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 0 | 0.177 |

| Conventional | 41 (15.1) | 31 (17.1) | 10 (11) | |

| Type of operation | ||||

| PD | 217 (79.2) | 141 (77) | 76 (83.5) | |

| Classic | 147 (67.8) | 92 (65.2) | 55 (72.4) | |

| Pylorus-preserving | 70 (32.2) | 49 (34.8) | 21 (27.6) | 0.189 |

| DP | 40 (14.5) | 30 (16.4) | 10 (10.9) | |

| TP | 7 (2.6) | 6 (3.3) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Other | 10 (3.7) | 6 (3.2) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Minimally invasive | 8 (2.9) | 5 (2.7) | 3 (3.3) | 0.628 |

| Vein resection (n = 271) | 94 (34.7) | 68 (37.8) | 26 (28.6) | 0.132 |

| Estimated blood loss, mL, median (IQR) | 400 (200–750) | 400 (200–750) | 400 (150–700)x | 0.369 |

| Operative time, min, median (IQR) | 364 (245–459) | 377 (261–476) | 324 (208–436) | 0.036* |

| ICU stay, d, median (IQR) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0.236 |

| Hospital stay, d, median (IQR) | 7 (6–10) | 7 (5–9) | 8 (6–11) | 0.355 |

| 30-day mortality | 6 (2.2) | 5 (2.7) | 1 (1.1) | 0.667 |

| 90-day Clavien-Dindo morbidity score | ||||

| None | 119 (43.4) | 80 (43.7) | 39 (42.9) | |

| I | 52 (19) | 41 (22.5) | 11 (12.1) | |

| II | 67 (24.5) | 40 (21.9) | 27 (29.7) | 0.065 |

| III | 25 (9.1) | 16 (8.7) | 9 (9.8) | |

| IV | 5 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (4.4) | |

| V | 6 (2.2) | 5 (2.7) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Pancreatic fistula (ISGPS grading) | ||||

| None | 252 (92) | 167 (91.3) | 85 (93.4) | |

| Grade A | 11 (4) | 8 (4.4) | 3 (3.3) | 0.765 |

| Grade B | 9 (3.3) | 6 (3.2) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Grade C | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

AC indicates adjuvant chemotherapy; DP, distal pancreatectomy; FLX, FOLFIRINOX; GNP, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel; IQR, interquartile range; ISGPS, International Study Group in Pancreatic Surgery; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; RT, radiation; SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy; SD, standard deviation; TP, total pancreatectomy.

Statistically significant.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was the most common type of operation (69.2%) followed by distal pancreatectomy (14.5%, Table 2). Only 2.9% of cases were performed laparoscopically. SMV-PV resection was performed in 34.7%: primary repair (73.4%), patch repair (18.1%), and autologous venous grafting (8.5%). Postoperative Clavien-Dindo morbidity score >3 and 30-day mortality rates were 13.1% and 2.2%, respectively (Table 2). There were no significant differences in perioperative outcomes between FLX and GNP, except for increased operative time in the FLX group [FLX, 377 minutes (IQR: 200 to 750) vs GNP, 324 minutes (IQR: 208 to 436), P = 0.036] (Table 2).

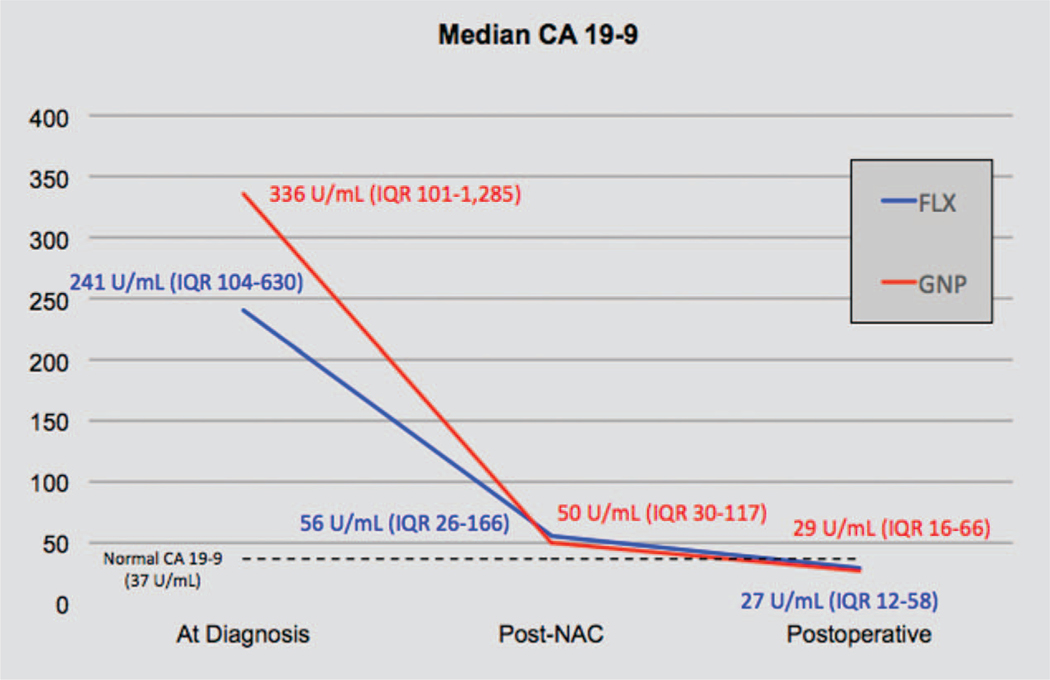

Biochemical Response

A total of 42 patients (15.3%) who had normal CA 19–9 level (<37 U/mL) at diagnosis and 129 patients (47.1%) who had missing values were excluded from the biochemical analysis. Of 103 patients, median CA 19–9 level at diagnosis was 259 U/mL (IQR: 104 to 837), post-NAC (pre-operative) was 53.8 U/mL (IQR: 29.1 to 142.9), and postoperative was 27.5U/mL (IQR: 13.5 to 58.3). CA 19–9 level decrease ≥50% after NAC was seen in 49 of 70 (70%) patients receiving FLX and 26 of 33 patients (79%) receiving GNP (P = 0.477). Of patients who achieved >50% decline in CA 19–9 levels, 74.4% had undergone 6 cycles or more of FLX and 81% had undergone 4 cycles or more of GNP. In addition, both regimens were associated with similar normalization of CA 19–9 (<37 U/mL) after NAC (FLX, 35.9% vs GNP, 35.2%, P = 0.535). In both groups, median CA 19–9 levels progressively declined from the time of diagnosis to post-NAC (preoperative) and achieved normal median CA19–9 levels postoperatively (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

CA 19–9 levels trend during treatment course demonstrating the biochemical response. CA 19–9 level decline greater than 50% after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) compared with baseline levels was 70% (FLX) and 84% (GNP).

Histopathological Findings and pCR

pCR was observed in 13 patients (6%). Of the patients without pCR, 124 (56.4%) had a pPR and 83 (37.7%) had a pLR (Table 3). Patients with >50% CA 19–9 decline had increased likelihood of pCR (11.3% vs 4%) and pPR (59.7% vs 40%), whereas those with <50% decline had increased rates of pLR (29% vs 56%, P < 0.048). The rate of R0 resection was 82.5% (FLX, 82.8% vs GNP, 81.8%, P = 0.853) and the rate of ypN0 was 47.8% (FLX, 48.9% vs GNP, 45.6%, P = 0.789). Patients undergoing FLX had less likelihood of positive SMA margins compared with GNP (FLX, 3% vs GNP, 10.9%, P = 0.042). The majority of tumors were ypT3 (51.7%) and moderately differentiated (57.4%). The median number of examined and positive LNs was 19 and 1, respectively. Patients receiving FLX have significantly more LNs examined than those receiving GNP (FLX, 20 vs GNP, 18, P = 0.031); however, no difference was found regarding LN positivity between the 2 groups (median FLX, 1 vs GNP, 1, P = 0.294, Table 3). LVI and PNI were found in 46.3% and 72.2%, respectively. Other histopathological data are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Pathological Findings

| Total n = 274 | FLX n = 183 | GNP n = 91 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen margin, n = 244 | ||||

| Positive | 24 (9.9) | 22 (13.5) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Negative | 208 (85.2) | 131 (80.4) | 77 (95) | 0.008* |

| No margin | 12 (4.9) | 10 (6.1) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Second frozen margin (positive), n = 246 | ||||

| Positive | 16 (6.5) | 15 (9.4) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Negative | 3 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.2) | 0.045* |

| No margin | 227 (92.3) | 143 (89.4) | 84 (97.6) | |

| Surgical margins, n = 211 | ||||

| R0 | 174 (82.5) | 111 (82.8) | 63 (81.8) | 0.853 |

| R1/R2 | 37 (17.5) | 23 (17.2) | 14 (18.2) | |

| Margin positivity (site) | ||||

| Pancreatic neck, n = 262 | 23 (8.8) | 14 (8) | 9 (10.3) | 0.643 |

| SMA, n = 196 | 11 (5.6) | 4 (3) | 7 (10.9) | 0.042* |

| Bile duct, n = 235 | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.5) | 0.274 |

| Tumor size, cm, median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.9–3.3) | 2.5 (2–3.5) | 2.5 (1.5–3.2) | 0.016* |

| pT stage, n = 261 | ||||

| pT0 | 3 (1.1) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | |

| pT1 | 44 (16.9) | 19 (21.6) | 25 (14.5) | |

| pT2 | 77 (29.5) | 52 (30.1) | 25 (28.4) | 0.651 |

| pT3 | 135 (51.7) | 93 (53.8) | 42 (47.7) | |

| pT4 | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| pN stage, n = 268 | ||||

| pN0 | 128 (47.8) | 87 (48.9) | 41 (45.6) | 0.789 |

| pN1 | 117 (43.7) | 77 (43.3) | 40 (44.4) | |

| LNs examined, median (IQR) | 19 (14–26) | 20 (15–26) | 18 (14–23) | 0.031* |

| Positive LNs, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 0.294 |

| Grade, n = 239 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 32 (13.4) | 19 (12.1) | 13 (16) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 137 (57.4) | 91 (57.6) | 46 (56.8) | 0.772 |

| Poorly differentiated | 69 (28.8) | 47 (29.7) | 22 (27.2) | |

| Undifferentiated | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion, n = 255 | 118 (46.3) | 83 (48.8) | 35 (41.2) | 0.287 |

| Perineural invasion, n = 259 | 187 (72.2) | 123 (71.1) | 64 (74.4) | 0.659 |

| Tumor response grade, n = 220 | ||||

| pCR | 13 (6) | 9 (5.8) | 4 (6.3) | |

| pPR | 124 (56.3) | 88 (56.4) | 36 (56.2) | 0.992 |

| pLR | 83 (37.7) | 59 (37.8) | 24 (37.5) |

FLX indicates FOLFIRINOX; GNP, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel; IQR, interquartile range; LN, lymph node; pCR, complete pathological response; pLR, none/limited pathological response; pPR, partial pathological response; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

Statistically significant.

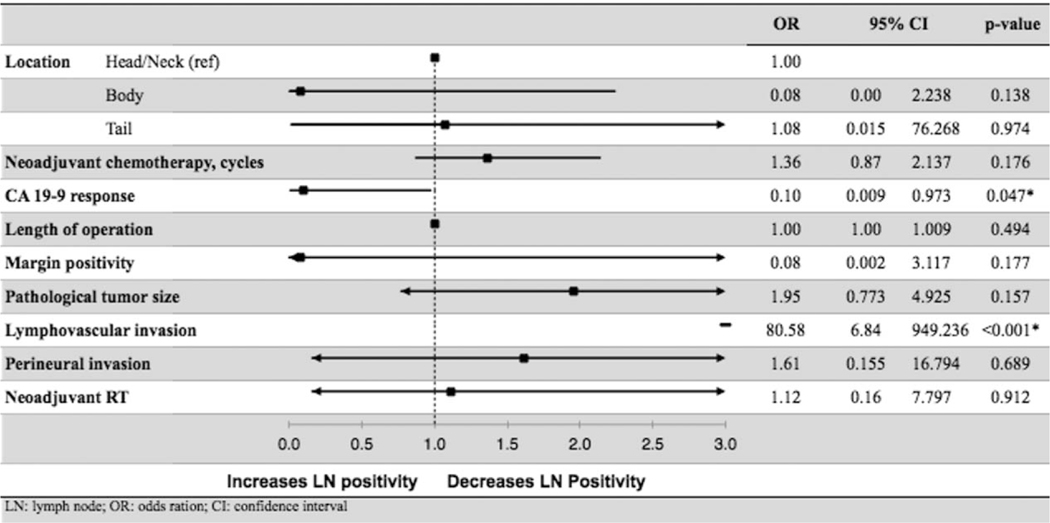

When adjusted for other confounders, multivariable logistic regression showed that LVI (HR: 80.578, 95% CI: 6.835–949.936, P < 0.001) was an independent predictor of increased LN positivity. CA 19–9 decrease >50% after NAC (HR: 0.096, 95% CI: 0.009–0.973, P = 0.047) was associated with decreased likelihood of LN positivity. NRT decreased the number of LNs examined [17 (IQR: 12 to 21.5) vs 20.5 (IQR: 16 to 27), P < 0.001] and positive LNs (NRT, 35.1% vs no NRT, 58.2%, P < 0.001). However, NRT was not an independent predictor of nodal status in the multivariate logistic regression (HR: 1.120, 95% CI: 0.160–7.797, P = 0.912, Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Predictors Associated With LN Positivity

|

CI indicates confidence interval; LN, lymph node; OR, odds ratio.

Survival Analysis

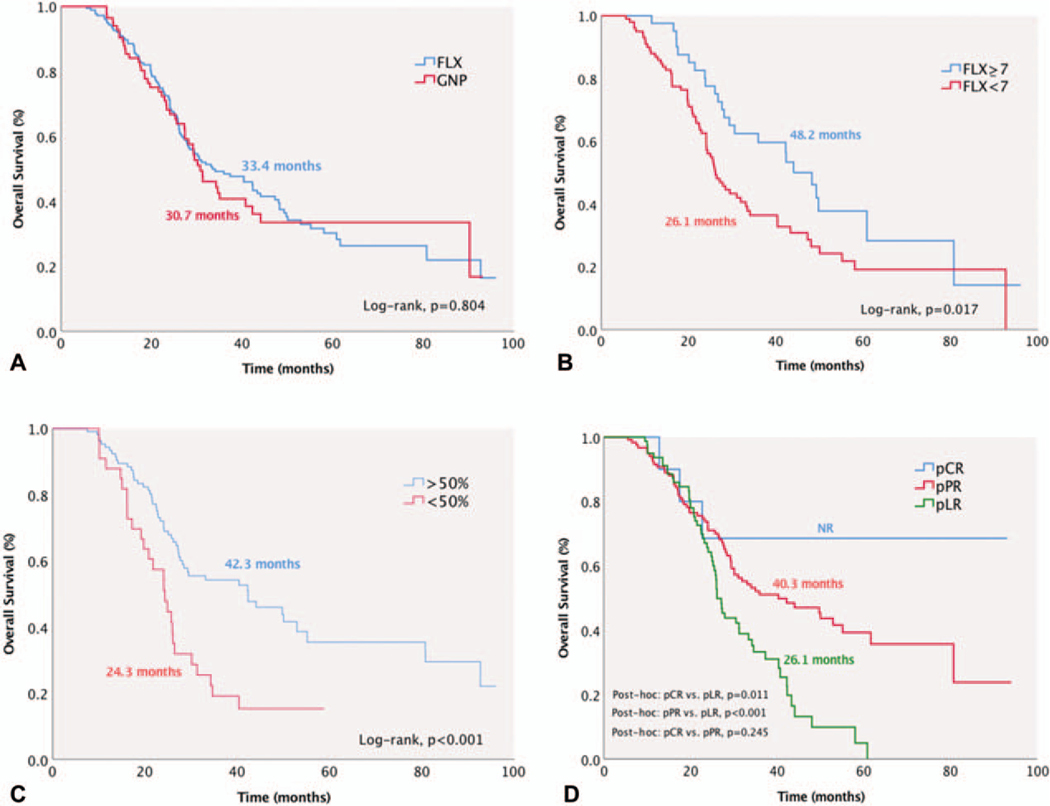

Six (2.2%) patients died within 30 days after the operation. Median follow-up time was 27.2 months (IQR: 17.6 to 42.3). Median, 3-year, and 5-year OS were 32 months (95% CI: 25.2–38.6), 46.3% (95% CI: 39.7–52.6), and 30.3% (95% CI: 23.2–37.6), respectively. There was no significant difference in OS between those receiving FLX or GNP [FLX, median OS, 33.4 months (95% CI: 25–41.8) vs GNP, 30.7 months (95% CI: 25.2–38.6), P = 0.804, Fig. 3A]. Patients who received ≥7 cycles of FLX had superior survival than those with <7 cycles [48.2 months (95% CI: 40.2–56.2) vs 26.1 months (95% CI: 22.5–29.7), P = 0.017, Fig. 3B]. Despite a relative superior OS for patients receiving ≥4 cycles of GNP compared with <4 cycles, no statistical difference was reached [31.2 months (95% CI: 25.1–37.4) vs 27.2 months (95% CI: 21.2–33.3), P = 0.697].

FIGURE 3.

Median overall survival (OS) was 32 months (95% CI, 25.2–38.6). A, No significant OS difference was found between FLX and GNP. B, Patients who received ≥7 cycles of FLX had superior survival than those with <7 cycles. C, Patients with >50% decline of CA 19–9 level after neoadjuvant chemotherapy had significantly superior OS than those with CA 19–9 decline <50%. D, Patients with pCR and pPR had improved OS compared with pLR patients.

Patients with positive nodal disease had significantly lower OS than node-negative patients [LN+, 26.1 months (95% CI: 23.3–29) vs LN-, 50 months (95% CI: 25.7–64.3), P < 0.001]. Likewise, patients with positive margins had significantly worse OS compared with R0 resection patients [R1, 24 months (95% CI: 17–31) vs R0, 40.3 months (95% CI: 31.6–49), P = 0.003]. Patients with ≥50% CA 19–9 level decrease after NAC had significantly improved OS than those with <50% CA 19–9 decrease [≥50%, 42.3 months (95% CI: 23.7–60.9) vs <50%, 24.3 months (95% CI: 20.1–28.5), P < 0.001, Fig. 3C) and similar outcomes compared with patients who normalized their CA19–9 levels [42.3 months (95% CI: 30.7–53.9), P = 0.745].

In patients who achieved pCR, median OS was not yet reached at 96 months. Patients with pCR [NR (95% CI: NR)] and pPR [40.3 months (95% CI: 25.2–55.4)] had significantly improved median OS than those with pLR [26.1 months (95% CI: 24.2–37.4)] (pCR vs pLR, P = 0.011 and pPR vs pLR, P < 0.001, Fig. 3D). There was no survival difference between patients with resectable PDAC [31 months (95% CI: 24.9–37.6)], BRPC [30.1 months (95% CI: 24.7–35.5)], and LAPC [33.1 months (95% CI: 18.7–47.5] (resectable vs BRPC, P = 0.969, resectable vs LAPC, P = 0.566, BRPC vs LAPC, P = 0.637, Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/SLA/B699).

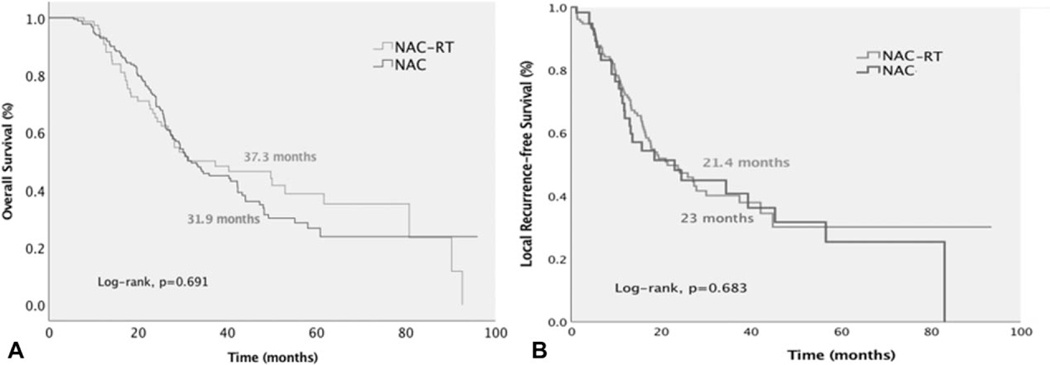

Patients receiving NAC-RT had similar median OS compared with those undergoing NAC alone [NAC-RT, 37.3 months (95% CI: 18.2–56.4) vs NAC, 31.9 months (95% CI: 27.1–36.7), P = 0.691, Fig. 4A]. NAC-RT did not demonstrate any survival benefit with either FLX [NAC-RT, 37.3 months (95% CI: 19.7–54.9) vs NAC, 33.4 months (95% CI: 24.1–42.7), P = 0.896] or GNP [NAC-RT 29.2 months (95% CI: 8.6–49.8) vs 30.7 months (95% CI: 25.6–35.8), P = 0.444, Fig. 4A].

FIGURE 4.

Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy did not improve overall survival (A) or local recurrence-free survival (B) compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone.

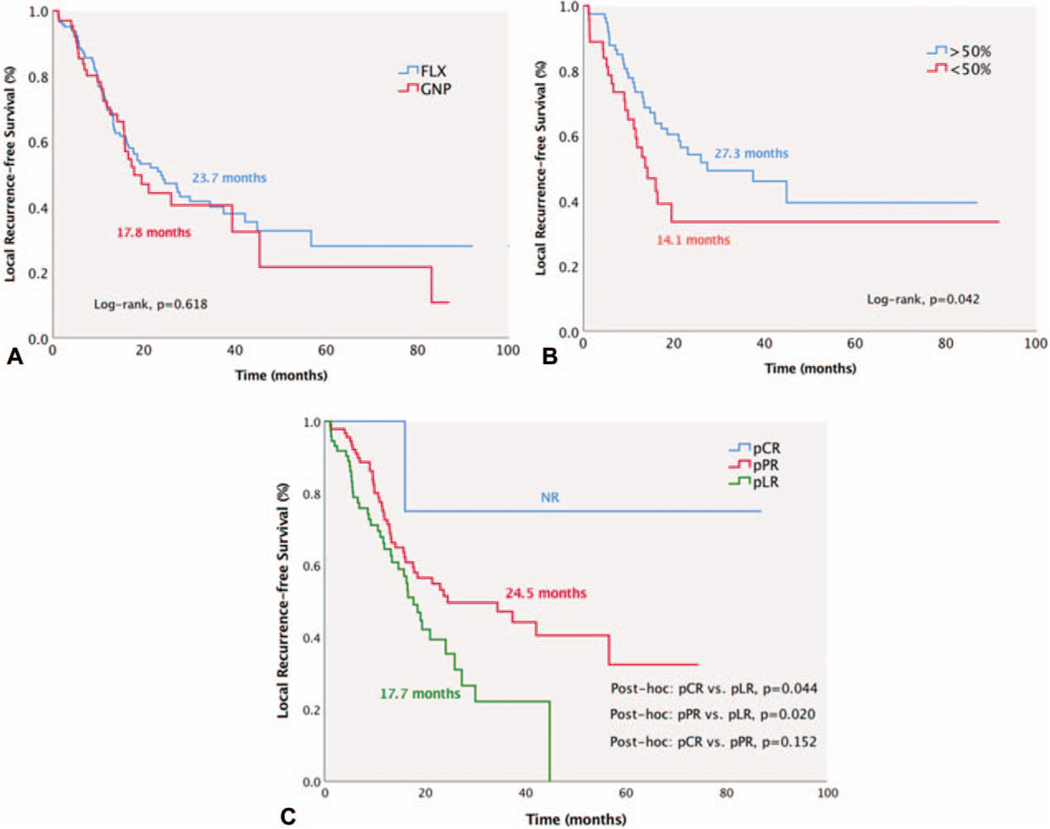

Median L-RFS was 21.4 months (95% CI: 15.3–27.4), and was similar between those who received FLX or GNP [FLX, 23.7 months (95% CI: 16.1–31.3) vs GNP, 17.8 months (95% CI: 12–23.6), P = 0.618, Fig. 5A]. Patients receiving NAC-RT had similar L-RFS compared with those undergoing NAC alone [NAC-RT, 21.4 months (95% CI: 13.8–28.9) vs NAC, 23 months (95% CI: 16.2–29.8), P = 0.683, Fig. 4B]. L-RFS was significantly improved in patients with CA 19–9 decrease ≥50% after NAC [≥50% decrease, 27.3 months (95% CI: 9.2–45.3) vs <50% decrease, 14.1 months (95% CI: 11.9–30.9), P = 0.042] and with better pathological response [pCR, NR (95% CI: NR), pPR, 24.5 months (95% CI: 6.7–42.3) vs pLR, 17.7 months (95% CI: 15.3–27.5), P = 0.044 and P = 0.020, respectively, Fig. 5B, C].

FIGURE 5.

Median local recurrence-free survival (L-RFS) was 21.4 months (95% CI 15.3–27.4). A, L-RFS was similar between FLX and GNP groups. B and C, L-RFS was superior in patients with marked biochemical response (≥50% decline) and pCR.

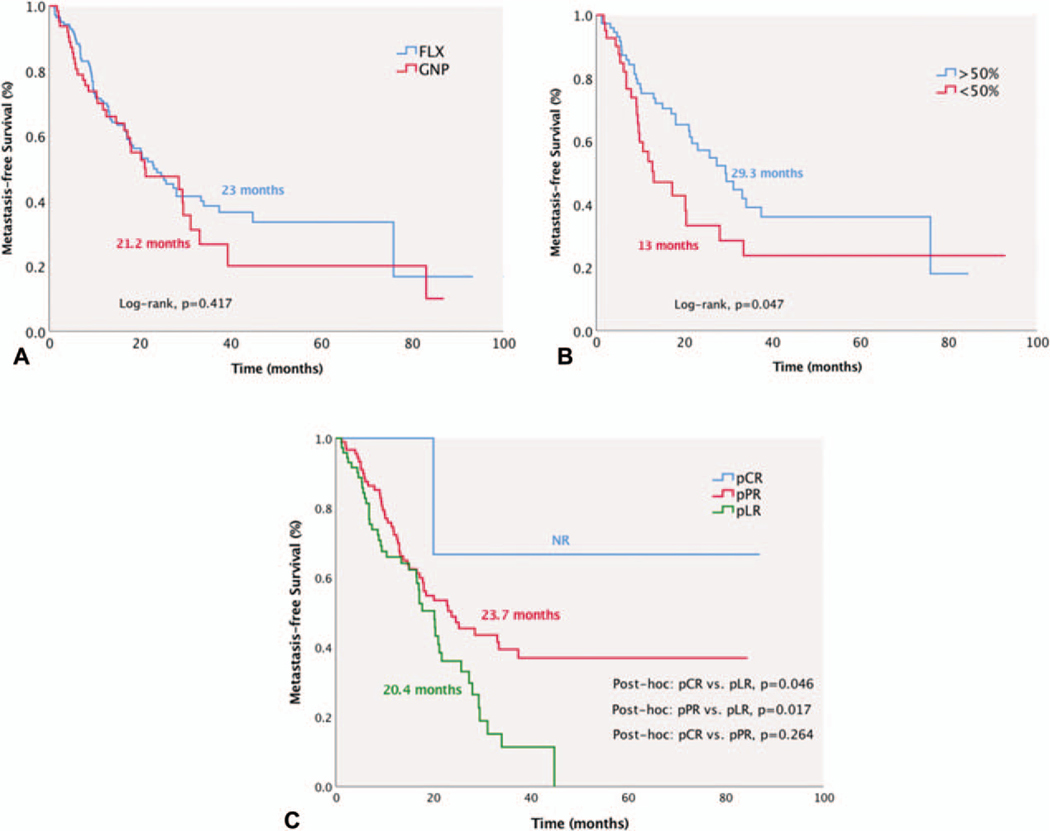

Median MFS for the entire cohort was 22.8 months (95% CI: 17.5–28.1). In the FLX group, MFS was 23 months (95% CI: 17.2–28.8), which was similar to the GNP group [21.2 months (95% CI: 10.2–32.2), P = 0.417, Fig. 6A]. MFS was significantly improved in patients with CA 19–9 decrease ≥50% after NAC [≥50% decrease, 29.3 months (95% CI: 20.6–38) vs <50% decrease, 13 months (95% CI: 5.1–20.9), P = 0.047] and with better pathological response [pCR, NR (95% CI: NR) and pPR, 23.7 months (95% CI: 14.5–32.9) vs pLR, 20.4 months (95% CI: 16.8–23.6), P = 0.046 and P = 0.017, respectively, Fig. 6B, C].

FIGURE 6.

Median metastasis-free survival (MFS) for the entire cohort was 22.8 months (95% CI 17.5–28.1). A, MFS was similar between FLX and GNP groups. B and C, MFS was superior in patients with marked biochemical response (≥50% decline) and pCR.

DISCUSSION

Adjuvant chemotherapy has been associated with modest improvement in survival following pancreatectomy.12 More recently, significant improvement has been achieved with the advent of newer and more effective multiagent chemotherapy regimens including FLX and GNP.13,14 The PRODIGE-24 phase 3 randomized trial enrolled 493 patients with resected PDAC to receive either adjuvant FLX or gemcitabine for 6 months.14 The median DFS (21.6 vs 12.8 months) and OS (54.4 vs 35 months) were significantly longer in those receiving adjuvant FLX.

Despite these salutary results, it is important to note that the PRODIGE-24 trial only included patients with good functional status (ECOG 0–1), those with postoperative CA19–9 < 180U/mL within 12 weeks after surgery, and one-third of patients who received adjuvant FLX did not complete planned adjuvant therapy. It is well known that up to half of patients who undergo curative-intent pancreatectomy for PDAC do not receive any adjuvant therapy due to postoperative complications or prolonged recovery, providing the rationale for the use of NAC.4 Although earlier studies of NAC with less effective regimens showed minimal responses, improved responses seen with NAC with either FLX or GNP have gained momentum and are now widely accepted as the standard of care for patients with BRPC and LAPC. The improved responses seen with these regimens have resulted in an increased number of patients eligible for resection, resulting in increased R0 resection rates compared with upfront surgery and has also encouraged their use even in patients with resectable PDAC.15–17 However, the impact of these improved clinical and pathological responses on survival outcomes in PDAC remains unknown.

In our multicenter series of 274 patients receiving NAC with either FLX or GNP, the median OS was 32 months, and 3- and 5-year OS were 46% and 30%, respectively. These results are superior to several retrospective series using different NAC regimens with median OS ranging from 19 to 26 months 18–22 Ferrone et al16 studied 188 patients with BRPC or LAPC undergoing FLX NAC. Patients receiving FLX had a significant decrease in LN positivity (35% vs 79%) and PNI (72% vs 95%) compared with upfront surgery. Median follow-up was 11 months with a significant increase in OS with NAC FLX.16 Recently, Dhir et al23 reported median OS of 28.9 months using a single-institutional retrospective cohort of 193 patients undergoing NAC with either FLX or GNP. Similar to our series, FLX was given to younger patients and no statistical survival difference was observed between the FLX or GNP (38.7 vs 28.6 months, P = 0.214) groups. Furthermore, both regimens were equally effective in CA 19–9 response and R0 resection rates.23

In our series, patients who completed at least 7 cycles of preoperative FLX had improved OS compared with those who received fewer cycles (48 vs 31.2 months, P = 0.023, respectively). These findings are congruent with the Dutch PREOPANC-1 intent-to-treat randomized trial, which enrolled 246 patients with PDAC to receive NAC-RT with gemcitabine for 10 weeks followed by surgery and adjuvant gemcitabine for 4 months or upfront surgery followed by 6 months of adjuvant gemcitabine.5 The median OS was 17.1 months with NAC-RT compared with 13.7 months with upfront surgery. NAC-RT was associated with improved DFS (9.9 vs 7.9 months, P = 0.023), MFS (18.4 vs 10.4 months, P = 0.013), and L-RFS (NR vs 11.8 months, P = 0.002). Of patients who underwent surgical resection, median OS was superior with NAC-RT compared with upfront surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (42 vs 16.8 months, P < 0.001).5 In our series, 3-year OS for those who completed 7 cycles of neoadjuvant FLX was 51.3% compared with the 2-year OS of 42% in the PREOPANC-1 trial. It is important to note that, in the PREOPANC trial, resection was performed in 72% of patients in the upfront surgery group and 62% in the neoadjuvant gemcitabine group.

In a recent single-arm phase 2 clinical trial, which investigated 48 patients with BRPC receiving 8 cycles of neoadjuvant FLX followed by surgery, median OS was not reached at 54-month follow-up and 2-year OS was 72%.24 The Alliance for Clinical Oncology Trial A021101 pilot study showed that 68% of patients underwent curative-intent pancreatectomy with 93% R0 resection rate and median OS of 21.7 months after 7 cycles FLX and capecitabine-based external-beam RT.9

Several other trials are underway, which will further enlighten our understanding regarding the role of NAC in PDAC survival. The Alliance for Clinical Oncology trial A021501 (NCT02839343) is enrolling 134 patients with BRPC who were randomly assigned to receive either NAC-RT with 7 cycles of FLX followed by stereotactic-body RT or 8 cycles of FLX alone.25 In an interim analysis, the NAC-RT arm was deemed as futile to achieve its desired R0 resection endpoint and was dropped. The ESPAC-5F trial (ISRCTN89500674) is accruing patients into 4 arms: upfront surgery, neoadjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine, neoadjuvant FLX, or NAC-RT with capecitabine.26 The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 1505 trial (NCT02562716) randomized patients with resectable PDAC to 12 weeks of perioperative FLX or GNP and surgery.27 This trial has completed accrual and results are forthcoming. These findings may shed light on our results and help tailor the ideal protocol for individual patients.

Interestingly, our study shows quite a significant improved survival rate in patients who have pCR (median OS not reached at 96 months). Likewise, the L-RFS and MFS rates in this subgroup were also significantly better than those with pLR. The pCR in our study was 6%, which is congruent with previous studies, ranging from 2% to 15%.28–30 The reason why pCR after NAC is less common in patients with PDAC compared with other gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies is unknown. He et al19 demonstrated a 10% pCR rate in patients with BRPC and LAPC treated at Johns Hopkins with neoadjuvant chemoradiation. The median OS of near complete response (27 months) or limited response (26 months) was less than that of pCR (more than 60 months). In multivariable analyses, pCR was an independent prognostic factor for DFS and OS. FOLFIRINOX and negative LN status were also associated with improved survival.19 Cloyd et al 29 demonstrated an inferior response to NAC with pCR rate of 3.9% and major pathologic response rate of 13.2% at MD Anderson Cancer Center. The median OS was significantly longer for patients who had a major response than for those who did not (73.4 vs 32.2 months, respectively). Age younger than 50 years, baseline serum cancer antigen 19–9 level less than 200 U/mL, and gemcitabine as a radiosensitizer were associated with a major response.29 Despite marked improvement in survival in these patients, it is difficult to statistically assess the impact of pCR due to small number of patients. Previous studies have grouped pCR and major pathologic response to overcome this limitation.31,32

We also observed that CA 19–9 decline ≥50% from baseline is an independent prognostic factor in PDAC. Others have shown that normalization of preoperative levels is another significant prognostic factor of improved survival.33–35 Williams et al35 demonstrated that patients with normal CA 19–9 after NAC had significantly longer survival than those whose level remained elevated (71.4 vs 32.5 months, respectively). Patients whose CA19–9 levels remained elevated and were taken to surgery after less than 6 months of NAC had markedly shorter survival than those who received the extended duration of treatment (16.7 vs 33.2 months, respectively). In our study, patients with normalization of CA 19–9 levels had superior outcomes compared with those with CA 19–9 decrease <50%, but similar OS compared with those whose CA 19–9 decreased ≥50% regardless of NAC regimen.

As we are beginning to observe certain tumors responding better to either FLX or GNP, future studies will have to identify predictive biomarkers to guide treatment and improve outcomes further. An important step has been the introduction of patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and drug-sensitivity profiles.36 Drug testing in PDO cultures may soon be used to inform treatment selection. In addition, longitudinal sampling in a single patient may be biomarkers of resistance to chemotherapy that parallels clinical disease progression. Also, genetic profiling of tumors may identify chemosensitivity signatures, which would enable more rapid treatment stratification of patients to the type of regimen they are most likely to respond to.36 Recently, the COMPASS trial (NCT02750657) was the first prospective translational study to demonstrate the feasibility of real-time genomic sequencing in PDAC.37 Unique PDAC genomic and transcriptomic subtypes, such as the classical and basal, were identified. Objective responses to first-line chemotherapy were significantly better in patients with classical PDAC RNA subtype compared with those with the basal-like subtype.37

We acknowledge that our study has several important limitations. First, this was a retrospective series, which may include potential for selection bias. Patients who progressed or died while on NAC were excluded, as this was not an intention-to-treat analysis and therefore we cannot compare the survival benefits between NAC followed by surgery versus upfront surgery and adjuvant therapy. NAC regimens and use adjuvant chemotherapy or RT and dosages were selected by each institution and not controlled in this study. However, our results were derived from 7 different medical centers, which are more indicative of “real-world” experience, rather than a selected patient cohort from a randomized clinical trial or single institution. In addition, we did not capture regimen toxicity, adverse events, and lack of adherence to standardized chemotherapy or RT protocols.

In conclusion, this large, multicenter study shows that improved biochemical (CA 19–9 decrease ≥50%) and pathological responses (pCR and pPR) to NAC with either FLX or GNP results in superior OS, L-RFS, and MFS compared with patients who have a limited biochemical (CA19–9 <50% decrease) and pathologic response (pLR). These results are important to help facilitate future clinical trials of NAC for PDAC, as they show that pCR, pPR, and CA19–9 decrease ≥50% or normalization appear to be surrogate markers for OS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Samuel H. Cass BSc, Rachel Fayne BSc, and Nuan Song BSc for their help in data acquisition.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.annalsofsurgery.com).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sirri E, Castro FA, Kieschke J, et al. Recent trends in survival of patients with pancreatic cancer in Germany and the United States. Pancreas. 2016;45:908–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199–1210. discussion 1210–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Tienhoven G, Versteijne E, Suker M, et al. Preoperative radiochemotherapy versus surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (PREOPANC-1). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun YS, Pawlik TM, Vauthey JN. 8th Edition of the AJCC Cancer staging manual: pancreas and hepatobiliary cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:845–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz MH, Shi Q, Ahmad SA, et al. Preoperative modified FOLFIRINOX treatment followed by capecitabine-based chemoradiation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Trial A021101. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:e161137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Washington K, Berlin J, Branton P, et al. Protocol for the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Carcinoma of the Exocrine Pancreas. Northfield, IL: College of American Pathologists; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee D, Katz MH, Rashid A, et al. Histologic grading of the extent of residual carcinoma following neoadjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3182–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh DH, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2395–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hackert T, Sachsenmaier M, Hinz U, et al. Locally advanced pancreatic cancer: neoadjuvant therapy with FOLFIRINOX results in resectability in 60% of the patients. Ann Surg. 2016;264:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrone CR, Marchegiani G, Hong TS, et al. Radiological and surgical limplications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2015; 262:12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Dunn JA, et al. Influence of resection margins on survival for patients with pancreatic cancer treated by adjuvant chemoradiation and/or chemotherapy in the ESPAC-1 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2001;234:758–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237:74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He J, Ahuja N, Makary MA, et al. 2564 resected periampullary adenocarcinomas at a single institution: trend over three decades. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suker M, Beumer BR, Sadot E, et al. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;18:543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laurence JM, Tran PD, Morarji K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of survival and surgical outcomes following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15: 2059–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Zhu H, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection versus upfront resection for resectable pancreatic cancer: a propensity score matched analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhir M, Zenati MS, Hamad A, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for neoadjuvant treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:1896–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy JE, Wo JY, Ryan DP, et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy with FOLFIRINOX followed by individualized chemoradiotherapy for borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:963–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz MH, Ou FS, Herman JM, et al. Alliance for clinical trials in oncology (ALLIANCE) trial A021501: preoperative extended chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy plus hypofractionated radiation therapy for borderline resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. BMC Cancer. 2017; 17:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ISRCTN8950. ESPAC-5F: European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer— Trial 5F. Available at: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN89500674. Accessed February 9, 2019.

- 27.Sohal D, McDonough SL, Ahamad SA, et al. SWOG S1505: a randomized phase II study of perioperative mFOLFIRINOX vs. gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel as therapy for resectable pancreatic adernocacinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(S4):5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.He J, Blair AB, Groot VP, et al. Is a pathological complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiation associated with prolonged survival in patients with pancreatic cancer? Ann Surg. 2018;268:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cloyd JM, Wang H, Egger ME, et al. Association of clinical factors with a major pathologic response following preoperative therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:1048–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose JB, Rocha FG, Alseidi A, et al. Extended neoadjuvant chemotherapy for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer demonstrates promising postoperative outcomes and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1530–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chatterjee D, Katz MH, Rashid A, et al. Histologic grading of the extent of residual carcinoma following neoadjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a predictor for patient outcomes. Cancer. 2012; 118:3182–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chun YS, Cooper HS, Cohen SJ, et al. Significance of pathologic response to preoperative therapy in pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3601–3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzeng CW, Balachandran A, Ahmad M, et al. Serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 represents a marker of response to neoadjuvant therapy in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Combs SE, Habermehl D, Kessel KA, et al. Prognostic impact of CA 19–9 on outcome after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2801–2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams JL, Kadera BE, Nguyen AH, et al. CA 19–9 normalization during preoperative treatment predicts longer survival for patients with locally progressed pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1331–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tiriac H, Belleau P, Engle DD, et al. Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018; 8:1112–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, et al. Genomics-driven precison medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1344–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.