Abstract

The shorter synthesis of a novel poly(propylene imine) (PPI) dendron that can be quantitatively conjugated in good yields in a modular fashion to various modified Michael acceptors is reported herein. The focal point of the PPI dendron was coupled to an ester-linked thioctic acid-modified spacer to allow for an improved scalable synthesis and to allow attachment to other suitable systems, such as nanoparticle surfaces. The two modified Michael acceptors reported here are an acyl hydrazine Michael acceptor as well as an azide Michael acceptor. The acyl hydrazine modified third generation PPI dendron was further conjugated to doxorubicin (DOX) as a model system to test acid-sensitive drug delivery. The PPI-DOX conjugate displayed fast release of DOX at pH 4.5 while remaining stable at pH 7.4 and the PPI-DOX conjugate showed low in vitro cytotoxicity against PC3 prostate cancer cells. This modular platform represents a powerful dendronized system for incorporation onto nanoparticles or other systems to allow for multifunctional drug delivery.

1. Introduction

In recent years nanomedicine has developed at a rapid pace to meet the needs of new therapeutics and develop more efficient targeted drug delivery and precision medicine in the field of oncology [1–4]. The polyvalence of polymers, in particular polymer brushes [5], makes them interesting candidates as drug delivery systems. More specifically, dendronized materials have emerged as a promising drug delivery platform to improve the therapeutic index of poorly soluble or unstable drugs [6], improve drug bioavailability and half-life [7,8], and achieve efficient targeted drug delivery while reducing unwanted off-target cytotoxicity [9]. Recently, AZD0466 (AstraZeneca), a potent Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitor conjugated to a PEGylated poly-lysine dendrimer, entered Phase I/II clinical trials as a potential chemotherapeutic to be used in mono or combination therapy against advanced non-Hodgkin lymphoma [10] and may also be able to treat malignant pleural mesothelioma [11]. Overall, the ability to synthesize dendrimers and dendrons in a controlled and stepwise manner with a well-defined nanoscale macromolecular structure makes them excellent excipients in polymer-drug conjugation chemistry. Additionally, the potential for highly reproducible batch-to-batch production chemistries makes them appealing assets to the pharmaceutical industry.

Classical dendrimers are spherically symmetric and highly branched structures that radiate out from a central core and possess a high number of terminal groups that may be conjugated to chemotherapeutics [12–16], nucleic acids [17,18], active targeting moieties [15,17], and molecular imaging agents [19,20]. Dendrons differ from classical dendrimers in that they possess a focal point displaying a functionality different from the branched terminal groups. The focal point can be used to attach dendrons to other systems such as polymeric structures or interact with various surfaces such as metal nanoparticle cores. Because dendrons can be synthesized with different terminal functionality, they can be combined into a single system to impart multifunctionality (e.g. chemotherapeutic delivery and active receptor targeting). Poly(amido-amine) (PAMAM), poly-l-lysine (PLL), and Fréchet-type dendrimers and dendrons are some of the most common materials that have been synthesized for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics, nucleic acids, and molecular imaging agents. Poly(-propylene imine) (PPI) dendrimers and dendrons have also been reported and possess several advantages over other families of dendritic structures [21–23]. Recently, the Daniel group has reported PPI dendrons that are water soluble and have a well-defined and monodisperse structure with a focal point that can interact with metal surfaces through a conjugated disulfide group. The PPI dendrons described here have the potential to be functionalized in a modular fashion with diverse terminal groups having nanotechnology applications. For example, the high degree of branched terminal groups (e.g. amines and carboxylic acids) may be reacted to form dendron conjugates with chemotherapeutics and targeting moieties (e.g. antibodies or antibody fragments). This modular potential to be used in drug conjugation and bioconjugation reactions makes the PPI dendron a powerful tool for use in the design of new nanotechnology platforms [24,25].

We report here the design, synthesis, and characterization of a PPI dendron conjugated to doxorubicin (DOX) through an acid-sensitive hydrazone bond that can be incorporated into other systems for drug delivery. The dendron synthesis described here involves a streamlined synthesis with reduced steps and large scalability. The conjugation to doxorubicin through acid-sensitive hydrazone bond and incorporation of bioconjugation-compatible azide click functionality was possible with modified Michael acceptors that were able to efficiently react with the second-generation amine-terminated PPI dendron leading to a high degree of valency. The PPI-DOX conjugate described here was found to have three DOX molecules per PPI dendron, stimuli-responsive DOX release at pH 4.5, and low in vitro cytotoxicity under physiological conditions in PC3 prostate cancer cells. This PPI-DOX and PPI-N3 dendron has strong potential for coating metal nanoparticles or surfaces and for subsequent bioconjugation to active targeting ligands for improved drug delivery applications.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. PPI ester-linker dendron synthesis

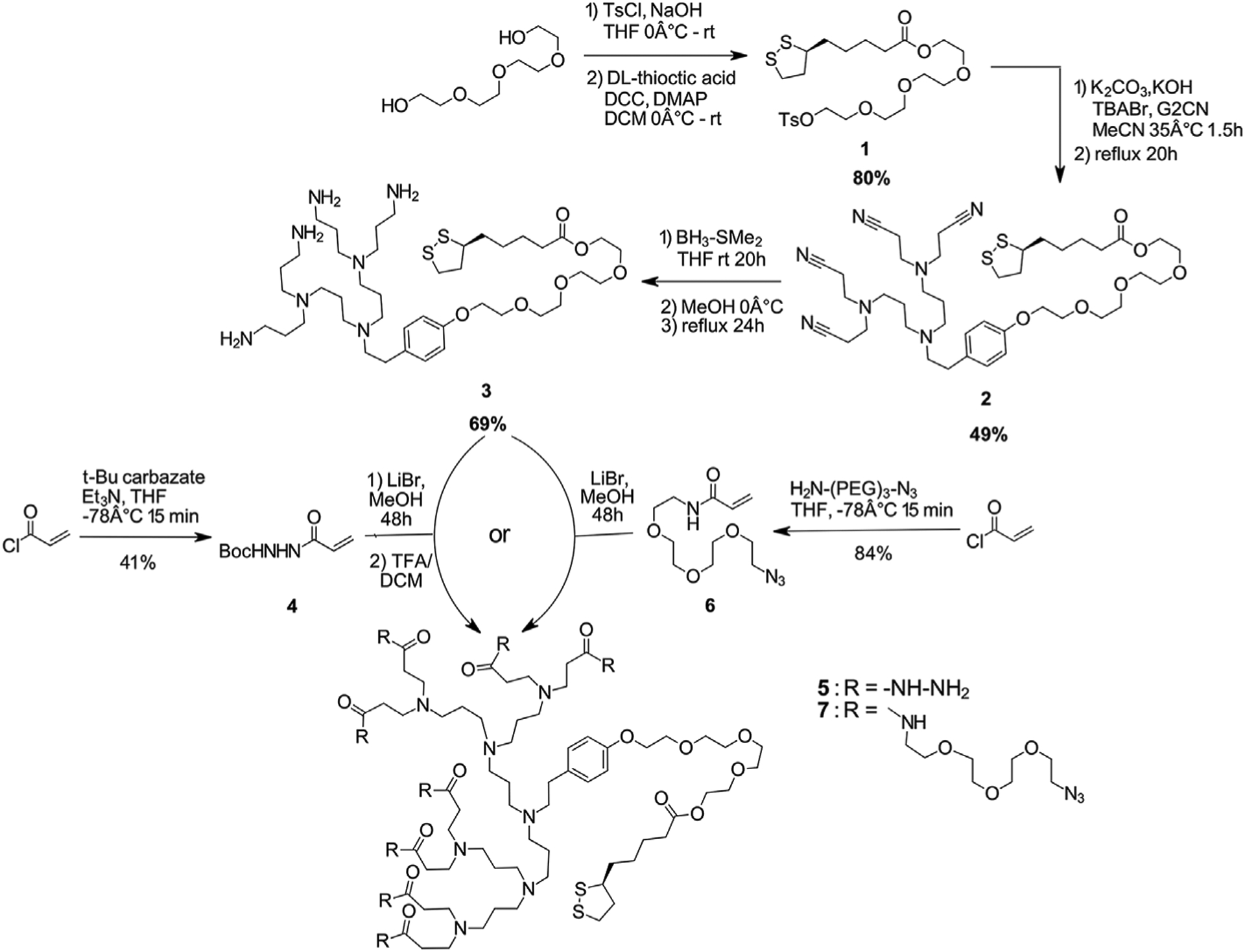

In our previously disclosed route, the synthesis of the spacer occurred through an amide bond between tetraethylene glycol (TEG) and thioctic acid (TA) [23]. This route required six steps and three column chromatography purifications to achieve the final TA-TEG-OTs spacer. To reduce the number of steps to the final spacer, improve the overall yield, and make this reactions sequence more scalable, a shortened route was designed beginning from tetraethylene glycol with an ester bond formation to thioctic acid (Scheme 1). Tetraethylene glycol was first tosylated and purified by a simple extraction workup to give HO-TEG-OTs. Subsequent coupling to thioctic acid using a carbodiimide intermediate gave TA-TEG-OTs 1 in 80% yield over two steps on gram scale with only one column purification step required.

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of TA-TEG-G2NH2 dendron (3) as well as of two modified Michael acceptors with acyl hydrazine (4) and azide functionality (6) and their additions to TATEGG2NH2 to form PPI-NHNH2 (5) and PPI-N3 (7), respectively.

The second-generation nitrile-terminated dendron (G2CN) was prepared as described previously [22] prior to coupling to the spacer 1 (Scheme 1). TA-TEG-OTs spacer 1 was coupled to G2CN by first deprotonating the G2CN phenolic group before adding the TA-TEG-OTs spacer 1 and refluxing overnight

The pure TA-TEG-G2CN product 2 could be obtained following flash column chromatography in 49% yield. The yield of pure dendron 2 may have been low due to degradation of the pure product on the silica column. As was previously reported with the amide spacer [23], the ester spacer is also prone to degradation and the silica column may accelerate this degradation. Because of this difficult purification, usually crude TA-TEG-G2CN product 2 (obtained in quantitative >1 g yield) was used immediately for subsequent reactions.

The terminal nitrile groups of PPI dendron 2 could be further reduced to give TA-TEG-G2NH2 3 in 69% yield (~300 mg scale) following purification by dialysis in water (Scheme 1). The TA-TEG-G2NH2 could be obtained in 55% overall yield over four steps (without purifying 2). The scale (300 mg to >1 g) and overall yield (55%) reported for this dendron are an improvement over the synthesis of similar divalent Newkome dendrons and are comparable to reported poly ester dendron syntheses but afford a higher degree of potential functionality [26–28]. For instance, Cho et al. synthesized second-generation Newkome dendrons having disulfide (4 steps, 180 mg, 30% overall yield) or thioctic acid (3 steps, 300 mg, 18% overall yield) [26]. Also, Wu et al. and Altin et al. synthesized bifunctional polyester dendrons (5 steps, 800 mg, 67% overall yield) [27,28].

Second-generation nitrile and amine-terminated PPI dendrons (dendrons 2 and 3) were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectrometry. The ESI-MS spectrum of TA-TEG-G2NH2 3 displayed a peak for the molecular ion (M + Na+) as well as a number of fragments peaks with a difference of 14 between all of them: this is most likely due to loss of CH2 groups from the alkyl chains of the dendritic branches. The successful coupling to form dendron 2 could be observed in the 1H NMR spectrum with the disappearance of the tosyl group peaks from the spacer at δ = 7.3 ppm and 7.7 ppm and the shift of the aromatic peaks of G2CN [22] to δ = 6.8 ppm and 7.1 ppm (Fig. S4). The number of branches in the second generation nitrile and amine dendrons could be determined by the integration of the aliphatic -N-(CH2)X-N- regions of the 1H NMR spectra at δ = 2.9−2.4 ppm (Figs. S4 and S8). For the nitrile-terminated dendron 2, an integration of 28H was observed while reduction of the nitrile groups to terminal amines results in an integration of 28H + 8H = 32H. The terminal amine groups furnished through this reduction step were used to react efficiently and quantitatively with modified Michael acceptors to add acyl hydrazine and azide functionality, respectively.

2.2. Synthesis of acyl hydrazine and azide PPI dendrons

To functionalize TATEGG2NH2 3 with the required hydrazine precursor and an azide click chemistry handle, modified Michael acceptors 4 and 6 were synthesized in 41% and 84%, respectively (Scheme 1). The low yields for these reactions can likely be attributed to the high reactivity of acryloyl chloride and the potential for side reactions/polymerizations. Acyl hydrazine-terminated dendron (PPI–NHNH2, 5) was synthesized by reacting TA-TEG-G2NH2 3 with Michael acceptor 4 (Scheme 1). Purification and isolation of the Boc-protected intermediate was difficult due to poor solubility in most organic solvents so deprotection was performed on the crude dendron. The pure deprotected acyl hydrazine dendron 5 (PPI–NHNH2) containing eight acyl hydrazine branches (Scheme 1) could be obtained following deprotection using trifluoroacetic acid and subsequent dialysis in water, with a 73% yield over two steps. The structure was confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR data (Figs. S14 and S 15, respectively). HRMS data showed the molecular ion (M + H) species of dendron 5 that supported the full functionalization of the PPI dendron with eight branches of the acyl hydrazine group (Fig. S16). This spectrum also showed a number of fragments with differences of 14 between fragments: this is most likely representing the loss of CH2 groups form the alkyl dendritic branches.

The azide functionality could be added to the PPI dendron by reacting TA-TEG-G2NH2 3 with Michael acceptor 6 to give the PPI-N3 dendron 7 (Scheme 1) in 65% with four branches of the dendron functionalized with TEG-azide as supported by 1H and 13C NMR data (Figs. S11 and S12, respectively). The presence of the azide functionality on the PPI-N3 dendron was also observed by FTIR spectroscopy with a stretching band at 2096 cm−1 (Fig. S13).

2.3. Conjugation of doxorubicin to acyl hydrazine PPI dendron

The acyl hydrazine dendron was conjugated to doxorubicin (DOX) via a hydrazone bond as a model system for pH-sensitive drug delivery applications. Indeed, acyl hydrazine bonds are stable at pH 7.4 in the blood, but cleave at pH lower than 5 which corresponds to the pH of lysosomes in cells. This allows for drug delivery only after entry to the cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME) [29].

Acyl hydrazine dendron 5 was reacted with twenty equivalents of DOX(Scheme 2) since using higher amounts of DOX did not lead to higher final payload. Purification of the resulting PPI-DOX dendron 8 by C18 reverse-phase chromatography and size exclusion chromatography failed in isolating the pure product so the product was purified by dialysis in methanol. The final product 8, carrying three DOX molecules per PPI dendron, was obtained in 26% yield. Efforts to conjugate more than three DOX molecules per dendron focused on using increasing amounts of DOX (up to forty equivalents) or increased reaction times (up to 10 days) to drive the reaction to completion. Despite these efforts, no more than three molecules were observed for most reaction conditions. Due to poor solubility in organic solvents and low stability in water at pH < 7, the freshly prepared PPI-DOX conjugate was usually stored as a mg/mL stock solution in anhydrous DMSO, in the dark. The PPI-DOX dendron was characterized by 1H NMR, UV–vis and fluorescence spectroscopy.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of PPI -DOX dendron (8) via acid-sensitive hydrazone bond.

2.4. Characterization of PPI-DOX dendron

The PPI-DOX conjugate was first characterized by 1H NMR in DMSO-D6 (Fig. 1). The aromatic region of the spectrum corresponding to the PPI dendron was found to be between δ = 6.6 ppm and 7.1 ppm and the integration of the dendron in this region corresponded to four, as expected from the tyramine structure within the PPI Dendron [22]. The aromatic region of DOX between δ = 7.2 ppm and 8.0 ppm corresponds to the three Ar–H protons within the aromatic region of DOX (3 H’s). The integration of this region was found to be nine, suggesting a conjugation ratio of 3:1 for DOX molecules per PPI dendron. DLS measurements of PPI-DOX in DMSO were also carried out and displayed a size by number of 10.7 nm, with a PDI of 0.47. This size is larger than the size of PPI-CO2H (size by number of 2.3 nm in water), reported earlier [30]. On one hand, this size confirms the addition of several doxorubicin molecules to the dendron. And on the other hand this size is larger than expected (doxorubicin’s size by number is about 1 nm): this could likely be the result of some dimerization (or oligomerization) happening through stacking of some doxorubicin groups from different PPI-DOX dendrons. The PPI-DOX conjugate was further characterized by UV–vis spectroscopy and fluorescence. The UV–vis max absorbance of the PPI-DOX conjugate was also shifted from 470 nm (free DOX) to 515 nm, further confirming the conjugation of DOX to the dendron. UV–vis quantification of DOX content on the PPI dendron was possible using a DOX standard curve and showed a ratio of 3:1 DOX per PPI dendron (Fig. S18). The PPI-DOX conjugate was also observed using fluorescence as compared to DOX-HCl and unconjugated PPI dendron 5 (Fig. 2A). The final PPI-DOX conjugate can be observed in blue with the presence of the strong DOX emission peak at 566 and 600 nm and the small PPI emission peak 545 nm. HRMS data showed several fragmented species of PPI-DOX dendron 8 that supported the full functionalization of the PPI dendron with three DOX molecules. Indeed, the peak 2647 m/z seem to correspond to the loss of most of a doxorubicin molecule while the peak at 2495 m/z corresponds to the loss of a doxorubicin dendritic branch (see drawing of fragments in Fig. S17). The peak at 2427 m/z could represent the loss of one doxorubicin branch and of one hydrazine branch, with the addition of a water molecule and a proton. The rest of the peaks correspond to loss of CH2 groups.

Fig. 1.

1H NMR of PPI -DOX dendron in DMSO-D6. Insert: zoom-in on the aromatic peaks of DOX (orange) and the dendron (blue).

Fig. 2.

A) Fluorescence spectra of i) PPI dendron, ii) DOX-HCl (normalized), and iii) PPI-DOX dendron; B) Dialysis release of DOX from PPI-DOX dendron at pH 4.5 as measured by fluorescence.

The 18% (wt.) DOX loading observed with this conjugation reaction is comparable or better to that reported with similar dendronized or polymeric systems. Indeed, some HPMA copolymers, linear polymers or peptide-based dendrons as well as heparin-conjugated dendrons have demonstrated between 6 and 14% (wt) DOX loading [31][32] [33] [34]. Highly branched polyester dendrimers have shown as high as 50% (wt.) DOX loading (four DOX per dendrimer) but these represent a single molecule for drug delivery [35]. Indeed, while the polyester dendrimers contain one more DOX than the herein reported PPI-DOX, the dendrimers represent a final system whereas the PPI-DOX is a dendron that can be combined with other systems. So, overall, the high drug loading for this PPI-DOX system represents an improvement over other dendrons in drug loading and the potential for attachment to nanoparticle surfaces (e.g. gold nanoparticles) will ultimately allow for the loading of hundreds to thousands of DOX molecules per nanoparticle.

The acid-sensitive release of DOX from the PPI dendron via hydrolysis of the acyl hydrazone bond at pH ≤ 5 is necessary for controlled and efficient delivery of DOX intracellularly following uptake into the lysosome. DOX release from the PPI conjugate was observed using fluorescence spectroscopy over the course of 350 h. The release of DOX occurred very rapidly at pH 4.5 within 10 h, less rapidly until 100 h (with 50% release after about 24 h) and more slowly thereafter (Fig. 2B). Amphiphilic dendron-DOX conjugates formed into micelles showed faster release of DOX at pH 4 with a leveling off in DOX release after 24 h, and slower release at pH 5 with 50% release after about 40 h [36,37]. Etrych et al. showed rapid DOX release at pH 5 from N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide HPMA copolymers over 24 h before levelling off [31]. The acid-sensitive release of DOX from the PPI-DOX conjugate shown here is as overall more prolonged than that reported for previous DOX-dendron or polymer conjugates in literature. This prolonged drug delivery (up to 100 h) can be advantageous in cancer therapy since a continuous delivery of drugs to the cancer cells for several days could lead to higher death rates of these cells [38,39].

With the PPI-DOX conjugate synthesized and characterized, the next step was to evaluate the in vitro properties of this system to ensure the physiological stability (pH ~7.4) of the PPI-DOX conjugate and show limited to no cytotoxicity in the DOX prodrug state. Solutions of PPI-DOX and PPI-CO2H dendron [23] were added to PC3 cancer cells at a concentration of 10 μM and incubated for 24–48 h. Cell viability was measured using an MTT assay in a 96-well plate. Both PPI-DOX and PPI-CO2H dendrons showed no cytotoxicity against PC3 prostate cancer cells up to 48 h (Fig. 3). This data suggests the PPI-CO2H dendron is nontoxic towards PC3 prostate cancer cells, supporting previous work by Saha Ray et al. [23]. The PPI-DOX conjugate in the prodrug form also showed no cytotoxicity, supporting the in vitro stability of this dendron under physiological conditions for up to 48 h. The stimuli-responsive and minimally cytotoxic nature of this PPI-DOX prodrug suggests this may be an ideal ligand for endowing gold nanoparticles or other nanostructures with drug delivery capability.

Fig. 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity data of PPI-CO2H dendron and PPI-DOX dendron incubated with PC3 prostate cancer cells for 24 and 48 h.

3. Conclusion

The work described here shows the improved and highly scalable synthesis of a versatile TA-TEG-G2NH2 PPI backbone dendron via an ester spacer coupling method in 27% yield over four steps. The ester-linker PPI backbone dendron possesses a thioctic acid disulfide group which can interact with gold nanoparticles and terminal amine groups which can react with suitable modified Michael acceptor groups to impart click chemistry and drug conjugation functionality. Conjugation of DOX to the PPI dendron was achieved through an acid-sensitive acyl hydrazone bond and the DOX was conjugated to the dendron at a ratio of 3:1 DOX per dendron. The PPI-DOX conjugate was characterized by 1H NMR and UV–vis spectroscopy and the stimuli-responsive release of DOX was observed via fluorescence. The PPI-N3 and PPI-DOX dendrons described here may be incorporated into larger nanostructures (e.g. other dendrons, metal nanoparticles, etc.) and have strong potential in the field of targeted drug delivery. The synthesis of such structures and their evaluation in the area of cancer nanotechnology will be the subject of future work.

4. Experimental methods

4.1. Materials

Solvents and reagents were obtained from commercial sources (e.g. Sigma Aldrich, Fischer Scientific, Acros Organics, VWR, TCI, etc.) and used without additional purification unless specified otherwise. Anhydrous solvents (e.g. THF, MeCN, DMF, DCM, MeOH) were obtained from an mBraun (MB-SPS) solvent purification system and maintained under an inert nitrogen atmosphere. Reactions performed at “room temperature” were carried out at ambient laboratory temperature (~20 °C). Solvent removal “under reduced pressure” was performed on an IKA rotary evaporator (HB10/RV8) under vacuum of 15–25 mmHg and temperatures of 30–50 °C. Thin layer chromatography was performed using silica (SiO2, 60 Å, Sigma-Aldrich #Z122726) or neutral alumina (Sigma-Aldrich #105550) on aluminum foil or glass support using the specified mobile phase(s). Reversed-phase TLC was performed using C-18-W plates (Sorbtech #2715126) and the specified mobile phase(s). Column chromatography was performed using silica (SiO2, 60 Å) from Scientific Analysis Institute (#02826–25) and eluted with the specified mobile phase(s). TA-TEG dendrons were purified using cellulose ester or regenerated cellulose dialysis membrane tubing (MWCO 100–500 Da, 500-1 K Da) obtained from Repligen/Spectrum Labs.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were obtained from a JEOL EC × 400 NMR spectrometer using 400 MHz and 100 MHz magnetic fields, respectively for 1H and 13C nuclei. Mass analyses were performed at the UMBC Molecular Characterization and Analysis Complex (MCAC, Baltimore, MD) and at the University of Maryland Baltimore Medical Center (Baltimore, MD). UV–Vis spectrophotometry data was obtained from a Beckman Coulter DU 730 UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Fluorescence measurements were collected on a Horiba Duetta fluorescence and absorbance spectrometer in emission mode and processed using the included EZ Spec software. Mass spectrometry samples were diluted in 60% methanol, 0.1% acetic acid and directly infused into a Waters Synapt G2S mass spectrometer.

1X PBS (pH 7.4) was prepared using volumetric glassware and 18 mΩ ultrapure water. 1X PBS was filtered through Cytiva Whatman™ Puradisc 0.2 μm syringe filters prior to use with nanoparticles or dilution to 0.1X PBS (pH 7.4, using 18 mΩ ultrapure water). Solutions of NaCl and saturated sodium bicarbonate (Fisher Scientific) were prepared using the corresponding salts and then filtered through Cytiva Whatman™ Puradisc 0.2 μm syringe filters before use with nanoparticles. PC-3 prostate cancer cells were grown in falcon-brand cell culture flasks using RPMI media supplemented with FBS and penstrep (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity studies involving TATEGG3DOX and TATEGG3CO2H were conducted with PC-3 cells using MTT reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol and are described in detail below.

4.2. Spacer synthesis

TA-OTEG-OTs (1) –

A solution of HO-TEG-OH (63 g, 0.32 mol, 1 equiv.) was prepared in 160 mL THF and stirred at 0 °C. To this stirring solution was added sodium hydroxide (3.9 g, 0.10 mol. 0.3 equiv.) as a dissolved solution in a minimal amount of Millipore ultrapure water (~5 mL). A separate solution of TsCl (6.1 g, 0.03 mol, 0.1 equiv.) was prepared in 40 mL THF. The TsCl solution in THF was added to the stirring solution of HO-TEG-OH and base at 0 °C via dropwise addition over the course of 30 min. After addition was complete, the reaction was stirred overnight while warming to rt. for 17 h. After 17 h, solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting aqueous slurry mixed with 100 mL DCM and 100 mL Millipore ultrapure water. The organic layer was removed, and the aqueous layer further extracted 4x with 100 mL DCM. The combined organic layers were then back-washed with 3 × 100 mL water to remove any unreacted HO-TEG-HO. The washed organic layer of DCM was dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give HO-TEG-OTs as a very pale yellow oil which was used without purification for the next step. HO-TEG-OH was dissolved in 150 mL DCM and stirred vigorously at 0 °C. Once cooled, d-thioctic acid (7.2 g, 0.03 mol, 1.1 equiv.), N N-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (7.2 g, 0.03 mol, 1.1 equiv.), and DMAP (2.7 g, 0.02 mol, 0.7 equiv.) were added to the reaction. The reaction quickly became a yellow heterogeneous solution and was allowed to stir overnight for 17 h while warming to rt. After 17 h the reaction was filtered and the filtrate concentrated under reduced pressure (but not to complete dryness) to give a yellow oil which was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, 100% EtOAc → 95:5 EtOAc:MeOH) to give the product as a clear yellow oil. (17.2 g, 80%). This pure oil was quickly prepared as a solution in anhydrous MeCN for the next reaction (stock concentration ~0.5 mg/mL). Rf = 0.75 (100% EtOAc, SiO2). The purity and identity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 4.18−4.13 (m, 2H), 3.72−3.42 (m, 14H), 3.20−3.06 (m, 2H), 2.50−2.41 (m, 4H), 2.21 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.89 (dq, J = 12.8, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 1.75−1.61 (m, 3H), 1.51−1.40 (m, 2H), 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.43, 144.82, 133.01, 129.84, 127.97, 77.31, 70.75, 70.61, 70.54, 69.25, 69.20, 69.16, 69.12, 68.69, 68.65, 63.44, 56.35, 56.32, 40.21, 38.48, 34.58, 33.93, 28.71, 24.61, 21.66, 21.63 and ESI-MS (calculated [M + Na+]: 559.1, found 559.3).

4.3. Backbone dendron synthesis

TA-TEG-G2CN (2) –

G2CN (758 mg, 1.64 mmol) was first prepared as described in previous literature [17] and then dissolved in 15 mL anhydrous MeCN from the solvent purification system and stirred in a round bottom flask. To this stirring solution was added K2CO3 (564 mg, 4.1 mmol), KOH (229 mg, 4.09 mmol), and tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBABr, 42 mg, 0.1 mmol). The heterogeneous solution was heated to 35 °C for 2.5 h to deprotonate G2CN. After 2.5 h heating, a solution of TA-TEG-OTs (1) (1.32 g, 2.5 mmol of 0.428 mg/mL stock in anhydrous MeCN) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 15 h after which point crude 1H NMR indicated consumption of G2CN starting material. The heterogeneous reaction solution was filtered to remove inorganic salts and concentrated under reduced pressure to give a brown-orange oil. The brown-orange oil was taken up in DCM and washed 1x with 50 mL deionized water followed by 1x with 50 mL brine. The resulting organic layer was dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to give the product as a dark brown oil in quantitative yield. This oil could be used directly for reduction to TATEGG2NH2 (3). Highly purified TATEGG2CN was obtained through SiO2 column chromatography (80:20:1 CHCl3:MeOH:NH4OH) as an orange oil (0.7 g, 49%). Rf = 0.71 (80:20:1 CHCl3:MeOH:NH4OH). The purity and identity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.12−7.03 (m, 2H), 6.83 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (dt, J = 7.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (dt, J = 6.2, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (dd, J = 5.7, 3.9 Hz, 2H), 3.76−3.49 (m, 14H), 2.85−2.74 (m, 8H), 2.66 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 5H), 2.60−2.38 (m, 18H), 2.33 (td, J = 6.7, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 1.96−1.81 (m, 1H), 1.62 (ddq, J = 29.3, 13.8, 8.1 Hz, 6H), 1.51−1.39 (m, 1H), 1.23 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.26, 129.76, 118.89, 114.67, 114.59, 72.67, 72.61, 70.87, 70.75, 70.67, 70.41, 69.87, 69.25, 67.52, 63.57, 61.84, 56.44, 55.74, 55.70, 51.59, 51.38, 50.86, 49.68, 49.61, 49.51, 40.32, 38.58, 34.69, 34.03, 28.84, 25.57, 25.07, 24.71, 17.04, 16.93, and ESI-MS [M + H+] calculated: 828.4, found 828.3.

TA-TEG-G2NH2 (3) –

TA-TEG-G2CN (2) (0.6 g, 0.73 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL anhydrous THF within a two neck round bottom flask under inert N2 atm and stirred. To this stirring solution were added two portions of BH3–SMe2 (1.4 mL, 14.5 mmol) 3 h apart. After the second addition, the reaction was stirred overnight under inert N2 atm. for 18 h. After 18 h, the reaction was cooled to 0 °C and quenched by dropwise addition of MeOH until all bubbling had ceased. Once bubbling had ceased and excess BH3–SMe2 was quenched, solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give a clear oil. The clear oil was dissolved in 100 mL MeOH and refluxed for 24 h. After refluxing for 24 h, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give a clear oil which was taken up in 30 mL Millipore ultrapure water. This aqueous portion was washed with hexanes (2 × 50 mL), EtOAc (2 × 50 mL), and diethyl ether (2 × 50 mL). The final aqueous portion was lyophilized to give the product as a white foam (0.5 g, 83%). The purity and identity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 7.06 (d, J = 20.6 Hz, 2H), 6.87−6.77 (m, 2H), 4.02 (d, J = 19.2 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 2H), 3.50 (d, J = 31.1 Hz, 14H), 3.34−3.23 (m, 1H), 2.96−2.79 (m, 2H), 2.57 (q, J = 10.8, 9.3 Hz, 10H), 2.38 (s, 10H), 2.30 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 10H), 2.21 (s, 1H), 2.07 (s, 2H), 1.53 (d, J = 23.3 Hz, 10H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, D2O) δ 181.48, 129.95, 114.99, 71.72, 69.69, 69.61, 69.47, 69.10, 67.29, 61.50, 60.35, 51.19, 50.74, 49.13, 43.91, 43.73, 38.78, 30.72, 27.84, 24.21, 23.28, 21.98, 19.90 and ESI-MS (calculated for reduced ester spacer [M + Na+]: 868.6, found 868.6).

4.4. Synthesis of functional michael acceptors

1-[(tert-Butyl)-2-carboxyhydrazino]-2-propen-1-one (4) –

Tert-butyl carbazate (2.0 g, 15.21 mmol) was dissolved in 40 mL anhydrous THF and stirred while cooling down to −78 °C using a dry ice/acetone bath. Once cooled, Et3N (4.2 mL, 30.42 mmol) and then acryloyl chloride (1.47 mL, 18.25 mmol) were added to the vigorously stirring solution of tert-butyl carbazate. A precipitate formed immediately, and the reaction was stirred at 78 °C for 15 min. After 15 min the reaction solvent was warmed to rt and removed under reduced pressure to give an off-white solid. The off-white solid was taken up in ~200 mL EtOAc and extracted with 100 mL Millipore ultrapure water. The aqueous portion was back-extracted 3x with 100 mL EtOAc and then the organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to give an off-white solid. The crude product was recrystallized from EtOAc to give the pure product as a white crystalline solid (1.2 g, 41%). The purity and identity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.40 (dd, J = 17.0, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (dd, J = 17.0, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (dd, J = 10.4, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 1.47 (s, 9H), matching previously reported data [34].

N-(11-Azido-3,6,9-trioxaundecyl)acrylamide (6) –

H2N-(PEG)4-N3 (200 mg, 1.5 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL anhydrous THF and stirred while cooling down to −78 °C. Once cooled, Et3N (422 μL, 3.0 mmol) and then acryloyl chloride (164 mg, 1.8 mmol) were added to the vigorously stirring solution of H2N-(PEG)4-N3. A precipitate formed immediately, and the reaction was stirred at −78 °C for 15 min. After 15 min, the reaction solvent was warmed to rt and removed under reduced pressure to give an off-white solid. The off-white solid was taken up in ~50 mL EtOAc and extracted with 10 mL Millipore ultrapure water. The aqueous portion was back-extracted 3x with 50 mL EtOAc and then the organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to give a pale yellow oil. The crude product was purified by LH20 size exclusion chromatography in MeOH and the solvent was removed, to give the pure product as a white foam (349 mg, 84%). TLC Rf = 0.18 (SiO2, 95:5 CHCl3:MeOH). The purity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.39 (s, 1H), 6.28 (dd, J = 17.1, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 5.62 (dd, J = 10.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (m, 12H), 3.53 (q, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.38 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), matching previously reported data [35].

4.5. Synthesis of functional PPI dendrons

PPI-NHNH2 (5) –

A solution of TA-TEG-G3NH2 3 (100 mg, 0.12 mmol) was dissolved in 15 mL MeOH and stirred at rt. To this stirring solution was added modified Michael acceptor 4 (442 mg, 2.4 mmol) and LiBr (20.6 mg, 0.237 mmol). The reaction was stirred at reflux for 48 h. After 48 h, an additional portion of 4 was added (221 mg, 1.2 mmol) and the reaction refluxed further for 24 h. After 72 h of reflux the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give an off-white solid which was used directly without purification for Boc-deprotection to form 5. The resulting crude Boc-protected dendron was dissolved in 1 mL dichloromethane and 1 mL trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). This solution was stirred for 2 h, at rt. After 2 h, 10 mL Millipore ultrapure water was added to the reaction and the solution transferred to a separatory funnel. The aqueous layer was washed 3x with 30 mL diethyl ether to remove most TFA (aqueous layer pH = 6). The resulting aqueous layer was dialyzed against Millipore ultrapure water (0.1–0.5 K Da MWCO) for 3 days and the dialysis solution was changed four times. The dialyzed product was lyophilized and purified further in Millipore ultrapure water using size exclusion chromatography (Sephadex LH-20). The final pure product was lyophilized again to give the pale-yellow oil (422 mg, 73%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 7.14 (s, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 6.16−5.99 (m, 1H), 5.72−5.60 (m, 1H), 4.06 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 2H), 3.63−3.43 (m, 17H), 3.27 (s, 5H), 3.11−2.79 (m, 22H), 2.76−2.34 (m, 24H), 2.23 (s, 6H), 1.74 (d, J = 23.2 Hz, 16H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, D2O) δ 183.38, 170.58, 163.14, 157.28, 130.22, 127.95, 120.77, 117.86, 114.96, 112.07, 69.70, 67.31, 63.91, 30.28, 10.52, 8.04.

PPI-N3 dendron (7) –

A solution of TA-TEG-G2NH2 3 (27 mg, 0.03 mmol) was dissolved in 4 mL anhydrous MeOH and stirred. To this stirring solution was added modified Michael acceptor 6 (121.7 mg, 0.4 mmol) and LiBr (35 mg, 0.4 mmol). The reaction was stirred vigorously at rt. for 48 h. After 48 h the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to give a yellow oil which was purified by LH20 size exclusion chromatography in MeOH. The pure product was obtained as a yellow oil (62 mg, 65%). The purity of the product was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD4) δ 7.15 (br, 2H), 6.87 (br, 2H), 4.08 (br, 2H), 3.81 (br, 2H), 3.62−3.32 (m, 77H), 3.14−2.10 (m, 63H), 2.07−0.51 (m, 76H) and FT-IR spectroscopy v = 2095 cm−1 (N3), 1732.7 cm−1 (CO). 13C NMR (101 MHz, D2O) δ 130.31, 115.03, 104.24, 69.73, 61.22, 57.50, 54.71, 50.25, 47.11, 39.42, 39.03, 33.96, 31.73, 28.77, 26.03, 23.21, 19.23, 18.54, 16.91, 12.98.

PPI-DOX dendron (8) –

TA-TEG-G3N(CH2CH2CONHNH2)2 5 (47 mg, 0.03 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL anhydrous MeOH and vigorously stirred. To this stirring solution was added Doxorubicin-HCl (350 mg, 0.6 mmol) and TFA (0.19 μL, 0.002 mmol). The reaction was heated to reflux under inert N2 atm. for 72 h. After 72 h the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give a dark red solid. The red solid was taken up in ~5 mL MeOH and dialyzed in the dark in MeOH (2 K MWCO Spec Por 6 dialysis membrane) until the dialysis solution showed no signs of DOX. After dialysis was complete the purified product was concentrated under reduced pressure to give the product as a dark red solid with three branches conjugated to DOX via hydrazone bond (24 mg, 26%). The product was characterized by 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.06−7.19 (m, 9H), 7.04 (s, 2H), 6.76 (s, 2H), 5.12 (d, J 109.2 Hz, 2H), 4.39 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 14H), 1.91–0.85 (m, 20H), UV–vis spectroscopy, and fluorescence.

4.6. Mass spectrometry characterization of dendrons

Samples were diluted in 60% methanol with 0.1% acetic acid. All samples were directly infused with a flow rate of 1 μL/min into a Synapt G2S mass spectrometer (Waters) with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The instrument parameters used for analysis were as follows: source temperature: 80 °C; capillary voltage: 2.0 kV; sample cone: 100 V; source offset: 20 V. 60% methanol with 0.1% acetic acid rinses were used between each infusion. Sodium iodide was used to calibrate over the range of m/z 100–4000. All mass spectra data were processed using Masslynz 4.1 software (Waters).

4.7. Stimuli-responsive DOX release

A solution of 2.0 mL PPI-DOX (8) in 0.1X PBS (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 2.51 mg/mL in 0.1X PBS was transferred to a 1 KDa MWCO RC dialysis membrane (Spectrum Chemical). The PPI-DOX solution in dialysis membrane was stirred and dialyzed in a volume of 350 mL 0.1X PBS acidified to pH 4.5 using 1 M HCl as measured by a pH test strip. At the specified time points (e.g. 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, etc.) a 3 mL aliquot of the dialysate was collected and the dialysate exchanged with fresh 350 mL 0.1X PBS acidified to pH 4.5 using 1 M HCl as measured by a pH test strip. Release of DOX from the dendron in the collected aliquots was determined by measuring fluorescence using an excitation wavelength of 470 nm.

4.8. In vitro cytotoxicity assay

PC3 prostate cancer cells grown as described previously were seeded in a 96-well plate in RPMI media at a density of 10,000 cells/well. After 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, dendrons (prepared as described above) were added to the wells at the specified concentrations. The cells were further incubated for 24, 48, and 72 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. At 24-, 48-, or 72-h timepoints, 15 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL in 1X PBS) was added to the cells and incubated for 4 h. After 4 h the media was removed, and the formazan crystals were dissolved in 200 μL 1X PBS with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 5% v/v). The 96 well plate was read after 3 h on an automated plate reader.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the NSF, United States (CBET-1705538). Additional support was provided by the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy Mass Spectrometry Center, United States (SOP1841-IQB2014). L.D. was supported by the NIH, United States (TT32GM066706-19).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2022.133044.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Tran S, et al. , Cancer nanomedicine: a review of recent success in drug delivery, Clin. Transl. Med 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rasool M, et al. , New challenges in the use of nanomedicine in cancer therapy, Bioengineered 13 (1) (2022) 759–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S, Nanoparticles in the clinic: an update post COVID-19 vaccines, Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 6 (3) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Que Y, et al. , Enhancing photodynamic therapy efficacy by using fluorinated nanoplatform, ACS Macro Lett 5 (2) (2016) 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Feng C, Huang X, Polymer brushes: efficient synthesis and applications, Accounts Chem. Res 51 (9) (2018) 2314–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chai D, et al. , Delivery of oridonin and methotrexate via PEGylated graphene oxide, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (26) (2019) 22915–22924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xu Z, et al. , Delivery of paclitaxel using PEGylated graphene oxide as a nanocarrier, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7 (2) (2015) 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu Z, et al. , Covalent functionalization of graphene oxide with biocompatible poly(ethylene glycol) for delivery of paclitaxel, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6 (19) (2014) 17268–17276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu LP, et al. , Dendrimers in medicine: therapeutic concepts and pharmaceutical challenges, Bioconjugate Chem. 26 (7) (2015) 1198–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Patterson CM, et al. , Design and optimisation of dendrimer-conjugated Bcl-2/x(L) inhibitor, AZD0466, with improved therapeutic index for cancer therapy, Communications Biology 4 (1) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Arulananda S, et al. , A novel BH3-mimetic, AZD0466, targeting BCL-XL and BCL-2 is effective in pre-clinical models of malignant pleural mesothelioma, Cell Death Discovery 7 (1) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Golshan M, et al. , Synthesis and characterization of polypropylene imine)-dendrimer-grafted gold nanoparticles as nanocarriers of doxorubicin, Colloids Surf., B 155 (2017) 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Najafi F, et al. , Effect of grafting ratio of poly(propylene imine) dendrimer onto gold nanoparticles on the properties of colloidal hybrids, their DOX loading and release behavior and cytotoxicity, Colloids Surf., B 178 (2019) 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kesharwani P, et al. , Dendrimer-entrapped gold nanoparticles as promising nanocarriers for anticancer therapeutics and imaging, Prog. Mater. Sci 103 (2019) 484–508. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hanurry EY, et al. , Biotin-decorated PAMAM G4.5 dendrimer nanoparticles to enhance the delivery, anti-proliferative, and apoptotic effects of chemotherapeutic drug in cancer cells, Pharmaceutics 12 (5) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bhatt H, et al. , Alpha-tocopherol succinate-anchored PEGylated poly(amidoamine) dendrimer for the delivery of paclitaxel: assessment of in vitro and in vivo therapeutic efficacy, Mol. Pharm 16 (4) (2019) 1541–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pan JY, et al. , Monoclonal antibody 2C5-modified mixed dendrimer micelles for tumor-targeted codelivery of chemotherapeutics and siRNA, Mol. Pharm 17 (5) (2020) 1638–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pan JY, et al. , Polyamidoamine dendrimers-based nanomedicine for combination therapy with siRNA and chemotherapeutics to overcome multidrug resistance, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 136 (2019) 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mekonnen TW, et al. , Encapsulation of Gadolinium Ferrite Nanoparticle in Generation 4.5 Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimer for Cancer Theranostics Applications Using Low Frequency Alternating Magnetic Field, Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces, 2019, p. 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu JY, et al. , Zwitterionic gadolinium(III)-Complexed dendrimer-entrapped gold nanoparticles for enhanced computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging of lung cancer metastasis, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (17) (2019) 15212–15221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Daniel MC, et al. , Gold nanoparticle-cored poly(propyleneimine) dendrimers as a new platform for multifunctional drug delivery systems, New J. Chem 35 (10) (2011) 2366–2374. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pan HM, et al. , A new poly(propylene imine) dendron as potential convenient building-block in the construction of multifunctional systems, Tetrahedron 69 (13) (2013) 2799–2806. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ray AS, et al. , Set of highly stable Amine- and carboxylate-terminated dendronized Au nanoparticles with dense coating and nontoxic mixed-dendronized form, Langmuir 35 (9) (2019) 3391–3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gu QM, et al. , Mild whole-body hyperthermia-induced interstitial fluid pressure reduction and enhanced nanoparticle delivery to PC3 tumors: in vivo studies and micro-computed tomography analyses, J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl 12 (6) (2020). [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gu QM, et al. , Nanoparticle delivery in prostate tumors implanted in mice facilitated by either local or whole-body heating, Fluid 6 (8) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cho TJ, et al. , Newkome-type dendron-stabilized gold nanoparticles: synthesis, reactivity, and stability, Chem. Mater 23 (10) (2011) 2665–2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu P, et al. , Multivalent, bifunctional dendrimers prepared by click chemistry, Chem. Commun (46) (2005) 5775–5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Altin H, Kosif I, Sanyal R, Fabrication of “clickable” hydrogels via dendron-polymer conjugates, Macromolecules 43 (8) (2010) 3801–3808. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Seidi F, Jenjob R, Crespy D, Designing smart polymer conjugates for controlled release of payloads, Chem. Rev 118 (7) (2018) 3965–4036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Saha Ray A, et al. , Set of highly stable Amine- and carboxylate-terminated dendronized Au nanoparticles with dense coating and nontoxic mixed-dendronized form, Langmuir 35 (9) (2019) 3391–3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Etrych T, et al. , New HPMA copolymers containing doxorubicin bound via pH-sensitive linkage: synthesis and preliminary in vitro and in vivo biological properties, J. Contr. Release 73 (1) (2001) 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].She WC, et al. , The potential of self-assembled, pH-responsive nanoparticles of mPEGylated peptide dendron-doxorubicin conjugates for cancer therapy, Biomaterials 34 (5) (2013) 1613–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pan DY, et al. , Dendron-polymer hybrid mediated anticancer drug delivery for suppression of mammary cancer, J. Mater. Sci. Technol 63 (2021) 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- [34].She WC, et al. , Dendronized heparin-doxorubicin conjugate based nanoparticle as pH-responsive drug delivery system for cancer therapy, Biomaterials 34 (9) (2013) 2252–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Guillaudeu SJ, et al. , PEGylated dendrimers with core functionality for biological applications, Bioconjugate Chem. 19 (2) (2008) 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].De Jesus OLP, et al. , Polyester dendritic systems for drug delivery applications: in vitro and in vivo evaluation, Bioconjugate Chem. 13 (3) (2002) 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gillies ER, Frechet JMJ, pH-responsive copolymer assemblies for controlled release of doxorubicin, Bioconjugate Chem. 16 (2) (2005) 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kalimuthu K, et al. , Gold nanoparticles stabilize peptide-drug-conjugates for sustained targeted drug delivery to cancer cells, J. Nanobiotechnol 16 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kalaydina RV, et al. , Recent advances in “smart” delivery systems for extended drug release in cancer therapy, Int. J. Nanomed 13 (2018) 4727–4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.