Abstract

Photoacoustic (PA) imaging is a powerful biomedical imaging modality. We designed KeTMR and KeJuR, two xanthene-based dyes that readily obtained through a 2-step synthetic route. KeJuR has low molecular weight, good aqueous solubility, and superior chemical stability compared to KeTMR. KeJuR shows robust PA signal at 860 nm excitation and can be paired with traditional PA dyes for multiplex imaging in blood samples under tissue-mimicking environment.

Graphical Abstract

Photoacoustic (PA) tomography, a unique “light in, sound out” imaging technique, is a powerful biomedical imaging modality.1 Commercially available PA instrumentations rely on excitation of PA contrast agents with a pulsed laser ranging from 680 – 980 nm.2 Non-radiative decay, typically in the form of local heating (≤ 0.1 K), leads to thermoelastic expansion, and the pulsed nature of excitation light results in fluctuating pressure waves that propagate through the samples as soundwaves with megahertz (MHz) frequencies. These soundwaves are detected at the surface by an ultrasound transducer to allow for the reconstruction of a 3D image of the sample. Since soundwaves scatter ~1000-fold less than light in tissue, PA offers high resolution imaging at deep tissue levels. The spatial resolution is about 1/200th of the imaging depth and could reach 350 μm at 7 cm depth.3 Importantly, unlike X-ray and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging techniques, PA does not require ionizing radiation and is therefore considered less hazardous.1

A range of small molecule chromophores have been used to generate contrast for PA imaging: polymethines, indocyanine green (ICG), phthaleins, xanthenes, squaranes, and porphyrins can generate PA signals.4 The ideal PA contrast agent should absorb near infrared light (NIR, 650 – 1000 nm) strongly (ε > 104 M−1·cm−1) to mitigate optical interferences like tissue scattering and interference from endogenous chromophores. Unlike fluorescence imaging, a low emissive quantum yield (Φ ≤ 5 %) is beneficial for PA imaging: excitation energy is dissipated as local heating to generate strong PA signal. Additionally, the agent should meet typical bioimaging criteria like low molecular weight, good aqueous solubility, and chemical stability.5 Achieving desirable PA qualities of long-wavelength absorption, high extinction coefficients, and low quantum yield while maintaining low molecular weight and good aqueous solubility remains an outstanding challenge.6

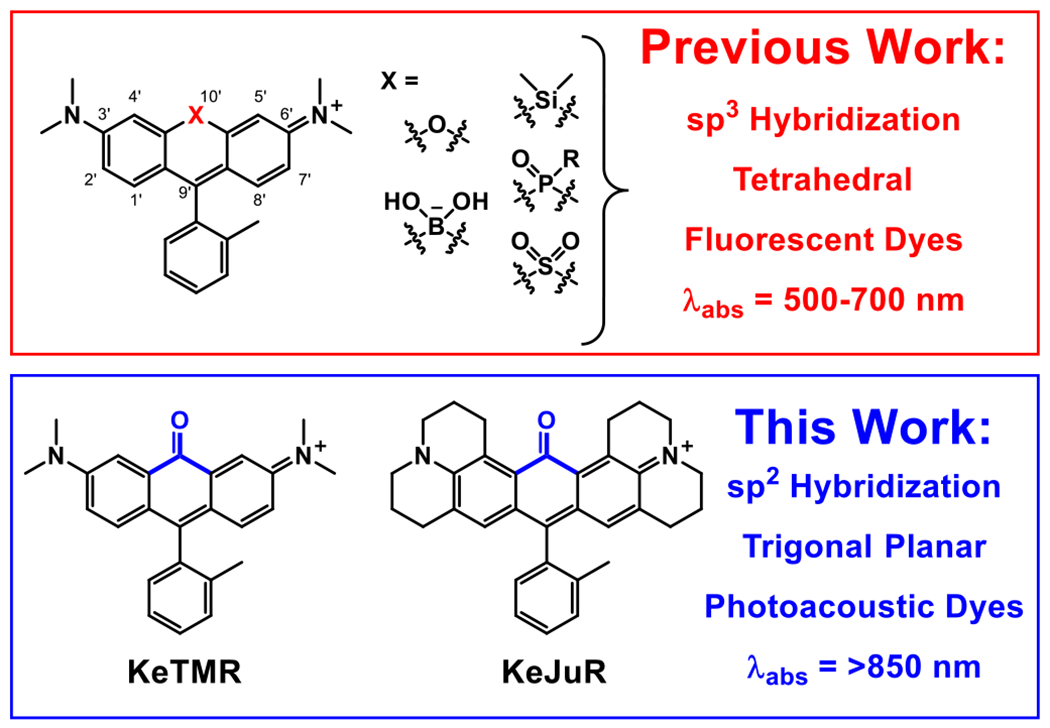

Historically, xanthene-based dyes like fluorescein and rhodamine have made significant contributions to fluorescence imaging owing to their visible-light excitation and emission profiles and high brightness.7 Traditional oxygen substitution at the 10’ position limits the excitation and emission to visible or far-red wavelengths (Figure 1). More recently, xanthene dyes were pulled into NIR bioimaging window through a bridging atom switching method. Both the excitation and emission maximum of xanthene dyes can be red shifted by over 100 nm upon replacement of the bridging 10’ oxygen with other, less electron rich groups like borinate,8 dimethyl silicon,9 phosphinate,10 phosphine oxide,11 and sulfone.12 All these modifications involved a sp3 hybridized bridging atom with a tetrahedral geometry, which decouples their electronic orbitals from the xanthene’s π-conjugated backbone. This low coupling results in little effect on the molar extinction coefficient (ε), quantum yield (Φfl), or shape of the excitation/emission spectra of the dye. This 10’ atomic substitution method has been used to design bright, long wavelength fluorescent dyes for various purposes like protein labeling,13, 14 sensing,15, 16 and functional imaging.17–19

Figure 1.

Structural comparison of previously reported xanthene based fluorescent dyes and the re-purposed PA dyes reported in this work.

Xanthene dyes have been previously explored for PA applications.4, 20–22 The strategies generally involved forcing the excited state dye to decay non-radiatively through the twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) pathway. However, this strategy often results in decreased water solubility, increased molecular weight, installation of polar sulfonates which complicate synthetic methods, and decreased chemical stability. We thought we could achieve PA imaging with a minimally disruptive modification to xanthene dyes, thereby retaining the low molecular weight, chemical stability, and good solubility profiles of xanthene dyes.

We hypothesized that an electron deficient group bearing a sp2 hybridized bridging atom inserted at the bridging position would possess good π-overlap and integration into the molecular orbitals of the xanthene chromophore, thereby substantially red-shifting the excitation and enhancing vibronic coupling. To test this hypothesis, we designed our xanthene-based PA agents by introducing a ketone functional group into this bridging position (Figure 1). According to the Dewar-Knott color rule23, 24 and computational calculations of other xanthene dyes,10, 12 the strong electron withdrawing nature of the bridging ketone group should lower the dye’s LUMO energy level, providing a dramatic red-shift of both absorption and emission. Additionally, the sp2 hybridization should provide effective vibronic coupling25 to further boost PA signal. While we were preparing this manuscript for publication, an elegant synthesis and characterization of a ketone-containing tetramethyl rhodamine was reported, establishing the viability of the ketone-incorporation approach.26

We first synthesized the ketone-bearing tetramethyl rhodamine (KeTMR) derivative (Figure 1). We elected to follow a different synthetic route8, 10 from the previously reported synthesis of KeTMR,26 in an effort to generate a concise and generalizable synthesis by introducing the ketone functionality at a late stage (Figure 2). Similar to previously reported syntheses of Nebraska Red6 and CAFS4 dyes, we started from a brominate triarylmethane, 1. Lithiation of 1 with sec-butyl lithium, followed by quenching with an electrophile would generate the ketone-containing dye core.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of KeTMR.

We screened several electrophiles, including diethyl carbonate, carbonyldiimidazole, and dimethylcarbamyl chloride; the use of N-methoxy-N-methylcarbamoyl chloride gives the best yield (Table S1). The hemiaminal intermediate was then effectively converted to ketone under mild acidic condition. After a brief work-up the leuco-dye can be oxidized with iodine in non-polar solvent like diethyl ether to precipitate KeTMR as brown solid (Figure 2). All the side products were soluble and could be washed away. This column-free, 2-step synthetic approach gives the desired KeTMR in 83 % yield (Figure 2). While characterizing KeTMR compound by 1H NMR, pure KeTMR was NMR silent (Spectrum S1). Addition of I2 regenerated the 1H NMR signal of KeTMR (Spectrum S2). EPR measurements reveal radical character in KeTMR without I2; the EPR of KeTMR + I2 shows no radical character (Spectrum S3). Together, these experiments establishes that KeTMR possesses radical character.

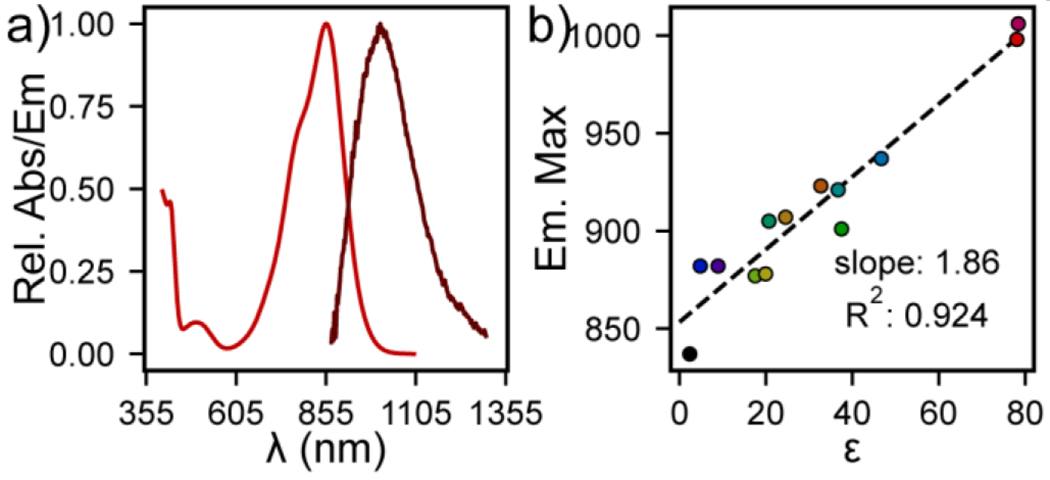

We characterized the optical properties of KeTMR. In aqueous solution under physiological conditions (phosphate-buffered saline, PBS, pH = 7.2, with 0.5 % DMSO), KeTMR absorbs strongly (ε = 26,900 M−1 cm−1) at 856 nm, with a wide full width at half maximum (FWHM, 2422 cm−1, Figure 3a). The fluorescence emission peaks at 1006 nm after solvent re-absorption correction (see SI), with a FWHM of 1857 cm−1 (Figure 3a). The quantum yield is low: 0.013 % (see SI). These values agree with previously reported absorbance, emission, and fluorescence quantum yield values (Table S4).26 In comparison with xanthene-based fluorophores, KeTMR has a much broader FWHM of both absorption and emission, larger Stokes shift (150 nm or 1742 cm−1), and lower quantum efficiencies (Figure S1 and Table S2). These parameters provide strong evidence that the ketone bridging group causes a significant vibronic coupling to the xanthene dye core.

Figure 3.

Absorbance and Emission Spectra of KeTMR. a) Plot of relative absorbance (red) or emission intensity (dark red) for KeTMR (10 μM, DPBS). Emission intensity is corrected for solvent re-absorption (SI). b) Plot of emission maxima for KeTMR (10 μM) vs. dielectric constant (ε).

The excitation and emission spectral profiles of KeTMR is influenced by solvent dielectric, on account of the direct conjugation of the highly polarizable ketone group with the rest of the xanthene molecular orbital. Indeed, the emission maximum of KeTMR increased almost linearly from 837 nm in toluene to 1006 nm in water (r2 = 0.924), indicating a strong solvent –dye interaction (Figure 3b, Table S3, Figure S2). The absorbance maximum does not vary strongly with solvent dielectric (r2 = 0.20, Figure S3), suggesting the solvent-dye interaction is strongest in the excited state.

A plot of Stokes shifts vs. solvent orientation polarizability (Δf)27 for KeTMR reveals a strong correlation between Stokes shift and Δf for KeTMR in protic solvents (r2 = 0.917), but weak correlation in aprotic solvents (r2 = 0.135, Figure S4a), indicating that hydrogen bonding between solvent and the ketone group directly influence the photophysical properties of KeTMR. The width of the emission peak of KeTMR varies linearly with the hydrogen bond donation (HBD) strength or α value,28 of the solvent (r2 = 0.927 Figure S4c), suggesting the degree of vibronic coupling could be tuned by the dye’s local environment. This was also supported by the low quantum yield of fluorescence in water (0.013%) and the relatively higher quantum yield in CH2Cl2 (1.3%, Table S4).26

Taken together, the photophysical properties of KeTMR provided strong evidence to support our design hypothesis that electron deficient sp2 ketone bridged xanthene should have stronger vibronic coupling at higher wavelength, making them suitable for PA applications.

We next sought to improve the fluorescence quantum efficiency, so that the same molecule could applied for both fluorescence and PA imaging modalities. We took advantage of our modular synthetic design to prepare the julolidine version of the ketone rhodamine, KeJuR (Figure 4). Rigidification of the aniline substituents by annulation should improve the fluorescence quantum yield, as the same method has been reported on various dyes before.10, 29 The synthesis of KeJuR was also through a 2-step route, beginning from 2, available on gram scale in 40% yield from commercially available starting material. Using conditions identical to the synthesis provided KeJuR in 11% yield. The addition of lanthanum(III) salt to further activate the carbamoyl group30 improved the overall yield to 30% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Synthesis of KeJuR.

KeJuR shows slightly red-shifted absorbance maximum, and blue-shifted emission maximum compared to KeTMR under the same solvent conditions (Figure 5, Table S3). In aqueous solution (PBS, pH 7.2, 0.5% DMSO), KeJuR has an absorbance maximum at 861 nm (ε = 21000 M−1 cm−1, FWHM = 2080 cm−1) and a broad emission at 988 nm (FWHM = 1743 cm−1). The fluorescence quantum yield of KeJuR is 0.032% in DPBS, and 2.3% in dichloromethane, slightly higher than the quantum yield of KeTMR.

Figure 5.

Absorbance and Emission Spectra of KeJuR. a) Plot of relative absorbance (red) or emission intensity (dark red) for KeJuR (10 μM, DPBS). Emission intensity is corrected for solvent re-absorption (SI). b) Plot of emission maxima for KeJuR (10 μM) vs. dielectric constant (ε).

KeTMR shows greater solvatochromism than KeJuR. First, a plot of emission vs. solvent dielectric for KeJuR also gives a near-linear fit (r2 = 0.911), Figure 5b), but with a shallower slope compared to KeTMR (1.86 vs. 1.52). Like KeTMR, the Stokes shift of KeJuR depends on solvent orientation polarizability (Δf, Figure S3b). In aprotic solvents, the correlation is quite weak (r2 = 0.135). In protic solvents KeJuR (r2 = 0.794) shows a weaker correlation than KeTMR (r2 = 0.917), consistent with the hypothesis that the carbonyl of KeJuR is more shielded from solvent than the carbonyl of KeTMR. Finally, in contrast to KeTMR, the FWHM of KeJuR emission shows only a weak correlation with solvent HBD strength (α, r2 = 0.68, Figure S3c), indicating that hydrogen bond donation from the solvent does not play as strong a role in altering the photophysical properties of KeJuR.

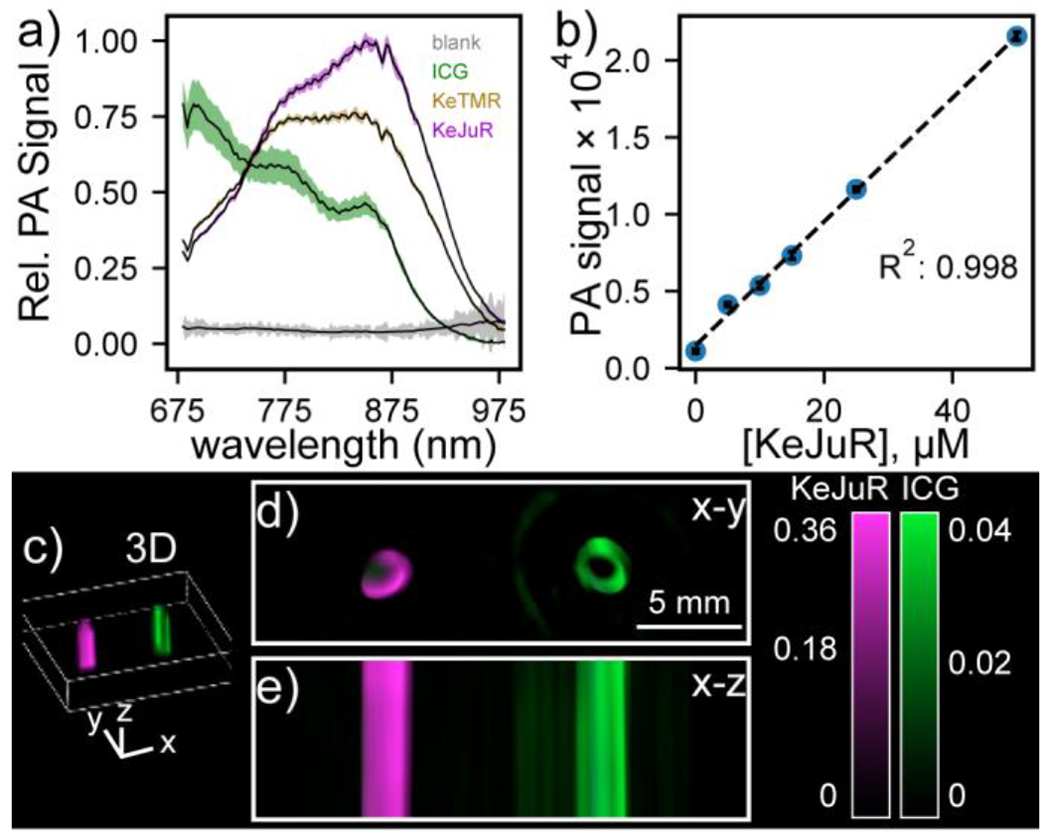

Both of the new ketone rhodamines give good PA signals in aqueous buffer, establishing that introduction of the carbonyl group at 10’ is a viable strategy for generating PA contrast reagents from xanthene scaffolds (Figure 6a). KeTMR and KeJuR possess PA peaks at approximately 860 nm. KeJuR shows a slightly stronger PA signal than KeTMR (Figure 6a, magenta vs tan). Introduction of the highly conjugated, strongly electron withdrawing ketone group might decrease chemical stability of ketone xanthene dyes by increasing their susceptibility to nucleophiles. We find this is the case for KeTMR, but not KeJuR. After treatment with glutathione (GSH), 86% KeJuR survived the reaction while only 6% KeTMR did under the same conditions (Figure S5). As a result, KeJuR was used in subsequent PA imaging studies.

Figure 6.

Photoacoustic imaging with Ke-xanthene dyes. a) Plot of relative PA intensity for 50 μM of the indicated dye in DBPS (pH 7.2, 1% DMSO). Data are mean ± S.D. for n = 7 different depths. b) Plot of PA signal (ex: 860 nm) vs. KeJuR concentration. c) 3D reconstruction of PA tomograph of KeJuR (magenta) or ICG (green) in sheep blood within a tissue phantom containing 60% milk. Cross - sections through d) x-y or e) x-z planes show strong PA signal for KeJuR.

KeJuR shows good aqueous solubility. Long wavelength dyes used for PA often suffer from low aqueous solubilities on account of the extended conjugation needed to achieve wavelengths compatible with PA imaging. This often requires either a high percentage of organic co-solvent like DMSO or DMF (in the range of 10-50 %), or detergents like SDS or CTAB (typically 0.1 wt %) to achieve solubility. Without these solubilizing reagents, dyes would aggregate, and display altered absorption and emission profiles, appearing as deviations in the signal at higher dye concentrations. Since the KeJuR was designed with a minimum structural change compared to its parent rhodamine scaffold, we envisioned this dye should enjoy a good aqueous solubility and maintain its spectral shape even at higher concentrations. The shape of the PA spectrum of KeJuR does not change over a concentration range of 5 to 50 μM KeJuR (DPBS, pH 7.2, 1% DMSO) (Figure S6). A plot of PA signal (860 nm) vs concentration is linear up through 50 μM (r2 = 0.998), indicating the good aqueous solubility of KeJuR (Figure 6b). KeJuR and KeTMR show good photostability compared to ICG (Figure S7).

With strong PA signal at 860 nm, good aqueous solubility, and high chemical stability, we wondered whether KeJuR could be paired with other PA dyes for multi-color imaging purposes. Since KeJuR gave a maximum PA signal at 860 nm, we picked the FDA-approved indocyanine green (ICG) as our partner dye.6

ICG gives strong PA signal at 680 nm due to strong H-aggregation,31 while KeJuR gives even higher signal at 860 nm (Figure 6a). KeJuR performs well in a model of blood and tissue. After spectral unmixing, we observe 10× higher PA signal from KeJuR compared to ICG when the dyes are imaged in defibrinated sheep blood within a tissue phantom (Figure 6c–e).32

In conclusion, we offer a new strategy to re-purpose the well-known fluorescent xanthene scaffold for PA imaging by manipulating the bridging hybridization geometry. The trigonal planar, ketone-containing KeTMR and KeJuR can be synthesized through a straightforward 2-step approach. The photophysical properties measured in various solvents of these two dyes strongly supported our hypothesis, that installing an sp2 hybridized ketone group at the 10’ position of the xanthene core can red-shift the optical properties and decrease the fluorescence quantum yield via enhanced vibronic coupling with the dye scaffold, making xanthenes more useful in PA applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar Foundation (EWM), NIH (R35GM119751, CIS; R35GM119855, EWM), and University of Virginia. PA imaging data was generated at the Bioimaging and Applied Research Core facility at Virginia Commonwealth University. We thank Prof. David Cafiso for access to EPR.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Wang LHV and Hu S, Science, 2012, 335, 1458–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knox HJ and Chan J, Accn Chem Res, 2018, 51, 2897–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Zhang P, Smaga LP, Hoffman RA and Chan J, J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137, 15628–15631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borg RE and Rochford J, Photochem Photobiol, 2018, 94, 1175–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo S, Zhang E, Su Y, Cheng T and Shi C, Biomaterials, 2011, 32, 7127–7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber J, Beard PC and Bohndiek SE, Nat Methods, 2016, 13, 639–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavis LD, Annual review of biochemistry, 2017, 86, 825–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou XQ, Lesiak L, Lai R, Beck JR, Zhao J, Elowsky CG, Li H and Stains CI, Angew Chem Int Edit, 2017, 56, 4197–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu MY, Xiao Y, Qian XH, Zhao DF and Xu YF, Chem Commun, 2008, DOI: 10.1039/b718544h, 1780–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou XQ, Lai R, Beck JR, Li H and Stains CI, Chem Commun, 2016, 52, 12290–12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai X, Cui X, Wang B, Yang F, Cai Y, Wu Q and Wang T, Chemistry, 2015, 21, 16754–16758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Sung YQ, Zhang HX, Shi HP, Shi YW and Guo W, Acs Appl Mater Inter, 2016, 8, 22953–22962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm JB, Tkachuk AN, Xie LQ, Choi H, Mohar B, Falco N, Schaefer K, Patel R, Zheng QS, Liu Z, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Brown TA and Lavis LD, Nat Methods, 2020, 17, 815-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Tran M, D’Este E, Roberti J, Koch B, Xue L and Johnsson K, Nat Chem, 2020, 12, 165-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deo C, Sheu SH, Seo J, Clapham DE and Lavis LD, J Am Chem Soc, 2019, 141, 13734–13738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mertes N, Busch M, Huppertz MC, Hacker CN, Wilhelm J, Gurth CM, Kuhn S, Hiblot J, Koch B and Johnsson K, J Am Chem Soc, 2022, 144, 6928–6935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang YL, Walker AS and Miller EW, J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137, 10767–10776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu P and Miller EW, Accn Chem Res, 2020, 53, 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez MA, Walker AS, Cao KJ, Lazzari-Dean JR, Settineri NS, Kong EJ, Kramer RH and Miller EW, J Am Chem Soc, 2021, 143, 2304–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myochin T, Hanaoka K, Iwaki S, Ueno T, Komatsu T, Terai T, Nagano T and Urano Y, J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137, 4759–4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeno T, Hanaoka K, Iwaki S, Myochin T, Murayama Y, Ohde H, Komatsu T, Ueno T, Nagano T and Urano Y, Anal Chem, 2019, 91, 9086–9092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rathnamalala CSL, Pino NW, Herring BS, Hooper M, Gwaltney SR, Chan J and Scott CN, Org Lett, 2021, 23, 7640–7644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewar MJS, Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed), 1950, 2329–2334. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knott EB, Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed), 1951, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butkevich AN, Sednev MV, Shojaei H, Belov VN and Hell SW, Org Lett, 2018, 20, 1261–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daly HC, Matikonda SS, Steffens HC, Ruehle B, Resch-Genger U, Ivanic J and Schnermann MJ, Photochem Photobiol, 2022, 98, 325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noboru M, Yozo K and Masao K, Bull Chem Soc Jpn, 1956, 29, 465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamlet MJ, Abboud JLM, Abraham MH and Taft RW, J Org Chem, 1983, 48, 2877–2887. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butkevich AN, Ta H, Ratz M, Stoldt S, Jakobs S, Belov VN and Hell SW, ACS Chemical Biology, 2018, 13, 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butkevich AN, Org Lett, 2021, 23, 2604–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung B, Vullev VI and Anvari B, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, 2014, 20, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner SH, Brady CJ, Keeton C, Yadav AK, Mallojjala SC, Lucero MY, Su S, Yu Z, Hirschi JS, Mirica LM and Chan J, Angew Chem Int Edit, 2021, 60, 18860–18866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.